Abstract

In the field of underwater laser detection, turbulence causes beam wandering and intensity scintillation, which subsequently alter the angle of incidence and ultimately degrade the quality of the target echo signal. By establishing an experimental platform that simulates oceanic turbulent channels, this study investigates the correlation between turbulence location and the backscattered optical scintillation index. This work lays the foundation for developing reliable assessment techniques for laser backscattering detection channels. Using a thermally driven turbulence simulator and an off-axis blue-green laser, a backscattering model was developed via echo signal analysis. This model captures the relationship between turbulence spatial distribution and the optical scintillation coefficient, revealing distinct nonlinear behavior in this relationship. Experimental results revealed a non-monotonic trend in the optical scintillation coefficient, characterized by an initial decrease followed by an increase, with the distance from the turbulence region. While increased water turbidity preserved this overall trend, it resulted in a dampened response. The proposed model demonstrated high reliability, with R2 values of 0.8579 and 0.8844 for the open-sea and coastal environments, respectively. The turbulent laser detection backscattering channel prediction model supports the evaluation of oceanic blue-green laser detection channels.

1. Introduction

Underwater target detection technology plays a critical role in both defense and civilian sectors, including seabed geological exploration, underwater obstacle avoidance and navigation, and the localization and search of submerged objects [1]. Underwater laser detection technology uses lasers at specific wavelengths, like the blue-green band (typically 532 nm), which lies within seawater’s “optical window,” to effectively enhance light penetration in water [2]. This not only ensures detection performance but also significantly improves the ability to identify and locate faint targets. Underwater laser detection systems, such as Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), actively emit coherent laser beams characterized by high energy, narrow pulse width, and high directivity. This enables effective detection, identification, and precise localization of faint underwater targets, even in complex water conditions and under background light interference. Its detection targets encompass a wide range of objects, including wreck components, naval mines, pipelines, small organisms, and air bubbles [3,4]. Given this diversity, the technology has emerged as a key solution for achieving high-accuracy and efficient detection of faint targets in complex marine environments. The propagation of optical signals in water is significantly degraded by various coupled interference factors, such as scattering, absorption, air bubbles, and turbulence. Underwater turbulence is an irregular, unsteady, three-dimensional, and multi-scale flow found in oceans, lakes, and other aquatic environments. It arises from velocity gradients, temperature differences, non-uniform salinity distribution, and external disturbances such as wind waves and current shear. This phenomenon is characterized by spatiotemporal random fluctuations in flow velocity, which induce intense mixing within the water body and enable an energy cascade [5]. When a laser propagates through such a turbulent medium, inhomogeneities in water’s refractive index give rise to a series of adverse effects, including phase fluctuations, intensity scintillation, and beam wander. Collectively, these effects impair the performance of underwater LiDAR detection systems [6].

Based on the consideration of turbulence, absorption, and scattering effects, Ata et al. [7] analytically derived the Rytov variance for a Gaussian beam optical power spectrum in oceanic turbulence. They concluded that as turbulence intensity increases, its impact can become quantitatively comparable to the effects of absorption and scattering. However, their study did not specifically investigate the influence of turbulence location on underwater laser detection. Yang Weng et al. [8] modeled the impact of turbulence-induced mixing processes on underwater optical links, demonstrating that larger temperature gradients lead to more significant degradation in underwater optical communication. Their work, however, is primarily focused on underwater laser communication rather than laser detection. Oubei, H.M. et al. [9] modeled and characterized the statistical properties of temperature-induced turbulence in underwater wireless optical communication channels using a generalized Gamma distribution. Ge Wenmin et al. [10] proposed an improved Monte Carlo simulation method to investigate the distributions of backscattered optical power and photon arrival angle in static water under different water quality conditions and light source divergence angles. However, their work did not address the impact of temperature-induced turbulence on backscattering characteristics. However, their model specifically addresses the forward scattering scenario and does not encompass backscattering. However, none of the aforementioned studies have simultaneously integrated turbulence location, backscattering, and underwater laser detection technology, nor have they simulated realistic oceanic turbulence characteristics. In contrast, the laser detection backward channel model under turbulence interference presented in this paper integrates these three aspects, thereby revealing the nonlinear relationship between turbulence location and the optical scintillation index.

To thoroughly investigate the influence of turbulence location on underwater laser detection performance in realistic environments, this study establishes a model describing the relationship between turbulence location and the optical scintillation index in laser backscatter detection under turbulence interference. This model is developed based on the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of turbulent fields and backscattering theory. Beginning from the definition of the optical scintillation index and incorporating the received light intensity model, the scintillation index is expressed as a function of normalized channel fading by separating deterministic and random factors. Leveraging Rytov theory, a quantitative relationship between the scintillation index and the variance of logarithmic amplitude fluctuations is established through the calculation of statistical moments of random variables. Based on the spherical wave propagation model, a relational model linking turbulence location to the optical scintillation index in laser backscatter detection under turbulence interference is derived. This model is subsequently validated and analyzed through experiments.

2. Modeling of Laser Transmission Channels Under Turbulence Interference

2.1. Modeling of the Laser Transmission Channel Under Oceanic Turbulence

Based on the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of underwater turbulent fields and the principle of laser backscattering, this study integrates Rytov theory with the spherical wave propagation model to establish a relationship model between turbulence location ‘s’ and the Scintillation Index (SI) in laser backscatter detection under turbulence interference [11]. The process of model establishment is as follows:

Currently, the SI, denoted as in the following text [12,13], is widely adopted in most studies to quantify the intensity of turbulent interference. It also serves as an evaluation metric for laser detection channels, where a lower SI value indicates better channel quality, and vice versa. Its definition is given by Equation (1):

where denotes the light intensity at the receiving end, and E[⋅] represents the mathematical expectation.

Since the photogenerated voltage from an avalanche photodiode (APD) in its linear region is proportional to the received optical power, the voltage variation can be approximated as the change in irradiance [14]. Therefore, Equation (1) can also be expressed as:

where represents the normalized voltage detected by the APD.

Considering the effects of absorption, scattering, and turbulence, the light intensity at the receiving end can also be expressed as:

where denotes the transmitted signal intensity, represents the mean attenuation caused by absorption and scattering effects, and is the normalized channel fading. Since and are deterministic, by separating the deterministic and random factors, Equation (3) can be expressed as:

where represents the deterministic factor (). Substituting Equation (4) into the definition of the optical scintillation index (Equation (1)), Equation (4) can be re-expressed as:

Based on the Rytov theory, under the condition of weak turbulence, the light intensity fluctuation can be characterized by the logarithmic amplitude fluctuation, and the received light intensity can be expressed as [15]:

where x denotes the logarithmic amplitude, a zero-mean Gaussian random variable induced by turbulence [15,16], i.e., . Therefore, the following can be established:

Thus:

Under weak turbulence conditions, [17], thus , where denotes the total logarithmic amplitude variance of the round-trip path, which is related to the propagation path length and turbulence intensity.

The round-trip path consists of the forward path and the backward path. In accordance with the Rytov theory and the spherical wave propagation model, the following expression is obtained:

where is the log-amplitude variance of the forward path, is that of the backward path [18], and represents their covariance.

Under homogeneous turbulence and weak fluctuation conditions, the log-amplitude variances of the forward and backward paths are essentially equal (i.e., ) [19], and their correlation coefficient is approximately unity. Thus:

where denotes the logarithmic amplitude variance of a single-pass path. For a spherical wave [20]:

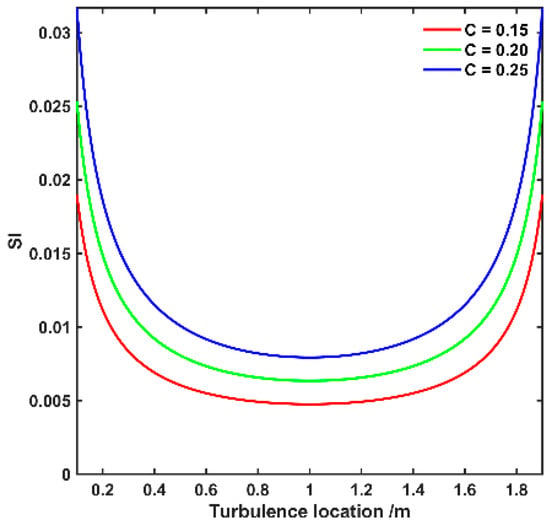

The model parameters are defined as follows: is a proportionality constant; , is the wavelength (a 532 nm blue-green laser is employed in this study); is the turbulence structure constant, ranging from [21]; L is the transmitter-to-target distance; and ‘s’ denotes the distance between the turbulent region and the transmitter. A schematic diagram of the system geometry is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

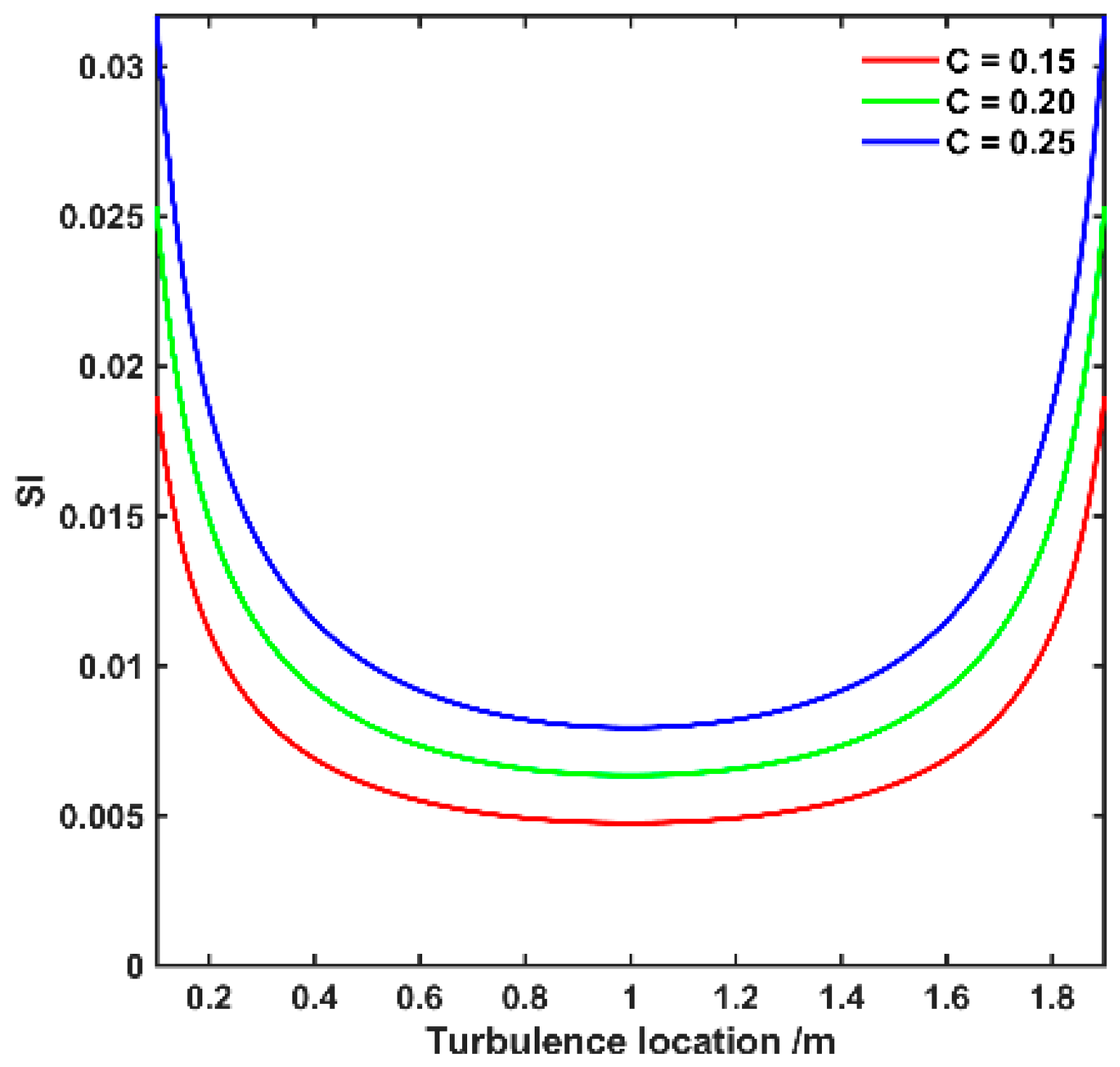

Simulation of laser transmission channel under oceanic turbulence interference ( = 10−10).

Finally,

where C is the final proportionality constant, which can be adjusted according to the experimental water quality conditions.

This model can be employed in experimental analysis by calibrating the proportionality constant C to account for varying water quality conditions when measuring turbulence intensity. In practical applications, the value of C can be calibrated and fine-tuned based on in situ water characteristics, such as temperature, salinity, and suspended particulate concentration, thereby enhancing the prediction accuracy of the SI for underwater laser propagation. This model offers a theoretical foundation and serves as a practical tool for the design and performance evaluation of underwater optical communication, laser ranging, and imaging systems.

2.2. Simulation of the Laser Transmission Channel Under Oceanic Turbulence Interference

Following the theoretical derivations in Section 2.1, this section examines the effects of a range of scaling factors on laser transmission channels through numerical simulation. The parameters were set as follows: λ = 532 nm, L = 2 m. Based on Formula (13), the scintillation index for different values of C and turbulence zone positions can be calculated, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the variation in the scintillation index with turbulence zone position for different scaling factors, with a fixed turbulence intensity parameter C = 10−10. When the turbulence structure constant and scaling coefficient are fixed, the SI initially decreases and then increases with an increase in the distance between the turbulence region and the transmitter. When turbulence is near the transmitter, the induced beam jitter is averaged over the extended link, leading to a monotonic decrease in the SI as the turbulence moves farther away. Conversely, when turbulence is close to the target, it acts as an effective amplitude-blocking layer in front of the receiver. The intensification of this effect dominates the signal perturbation, giving rise to an upward trend in the SI. As indicated by Formula (13), the SI is directly proportional to the turbulence intensity parameter C. Consequently, an order-of-magnitude increase in C leads to a proportional increase in SI, resulting in an upward shift of the entire characteristic curve along the vertical axis with its shape preserved. This relationship stems from the fact that C, the turbulence intensity parameter, directly quantifies the strength of refractive-index fluctuations in the medium. Under weak turbulence conditions (where the Rytov approximation holds), these fluctuations along the propagation path primarily induce phase perturbations. This, in turn, leads to a gradual conversion of phase perturbations into amplitude fluctuations as the wave propagates, which is observed as scintillation. At this point, the scintillation index is linearly related to C. This implies that the amplitude of phase perturbations is directly determined by C, which in turn linearly modulates the intensity of the resulting amplitude fluctuations. The SI reaches its minimum when the turbulence zone is at the propagation path midpoint (s = L/2), which can be attributed to the propagation geometry and wavefront evolution. In this symmetric position (equidistant to source and receiver), the conversion of phase perturbations into amplitude fluctuations is least efficient, resulting in the weakest scintillation. Under this condition, the impact of turbulence on the laser transmission channel is minimized. As the scaling factor C increases, the SI value correspondingly rises.

3. Experiments and Results Analysis

3.1. Experimental Setup

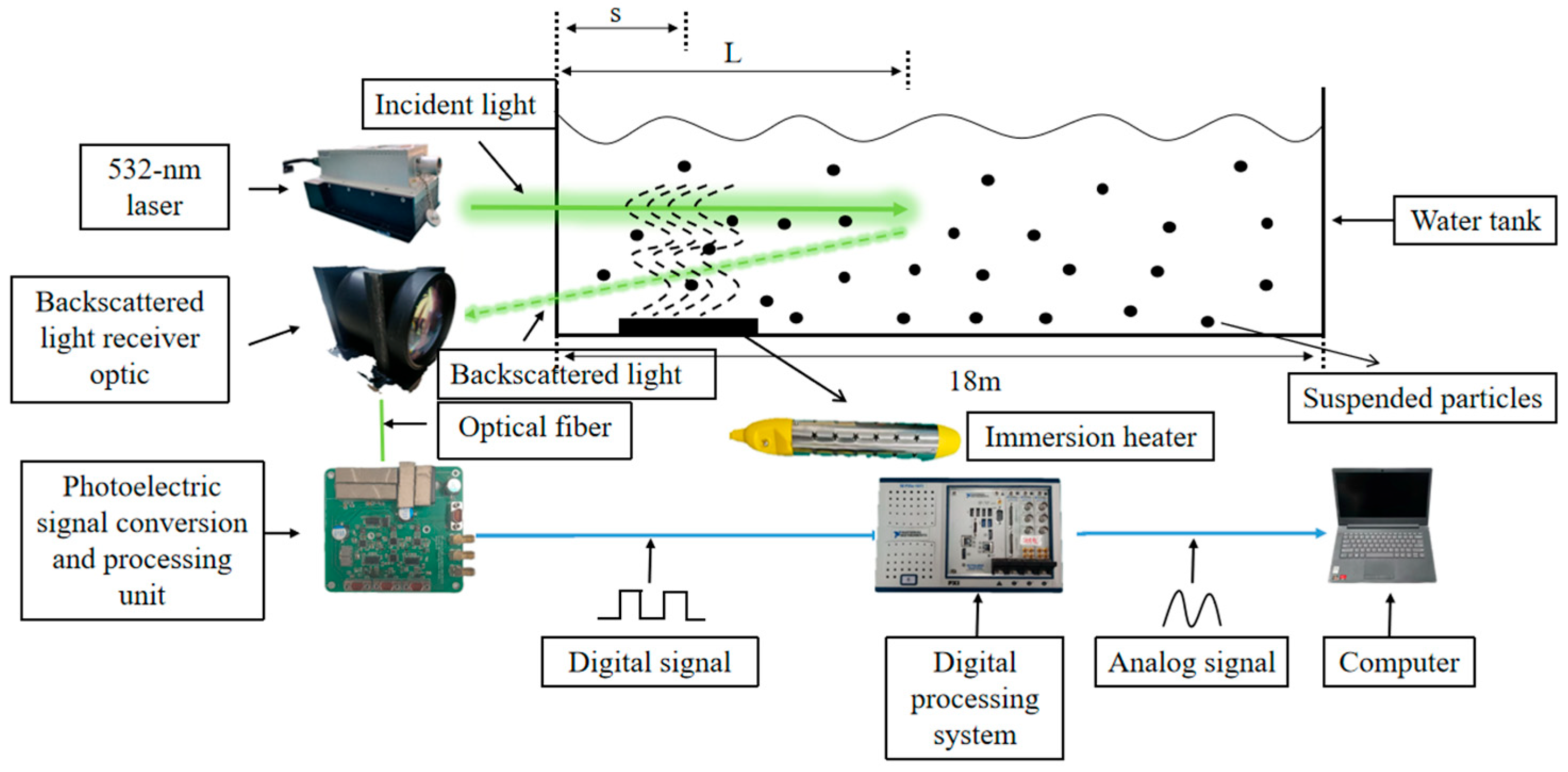

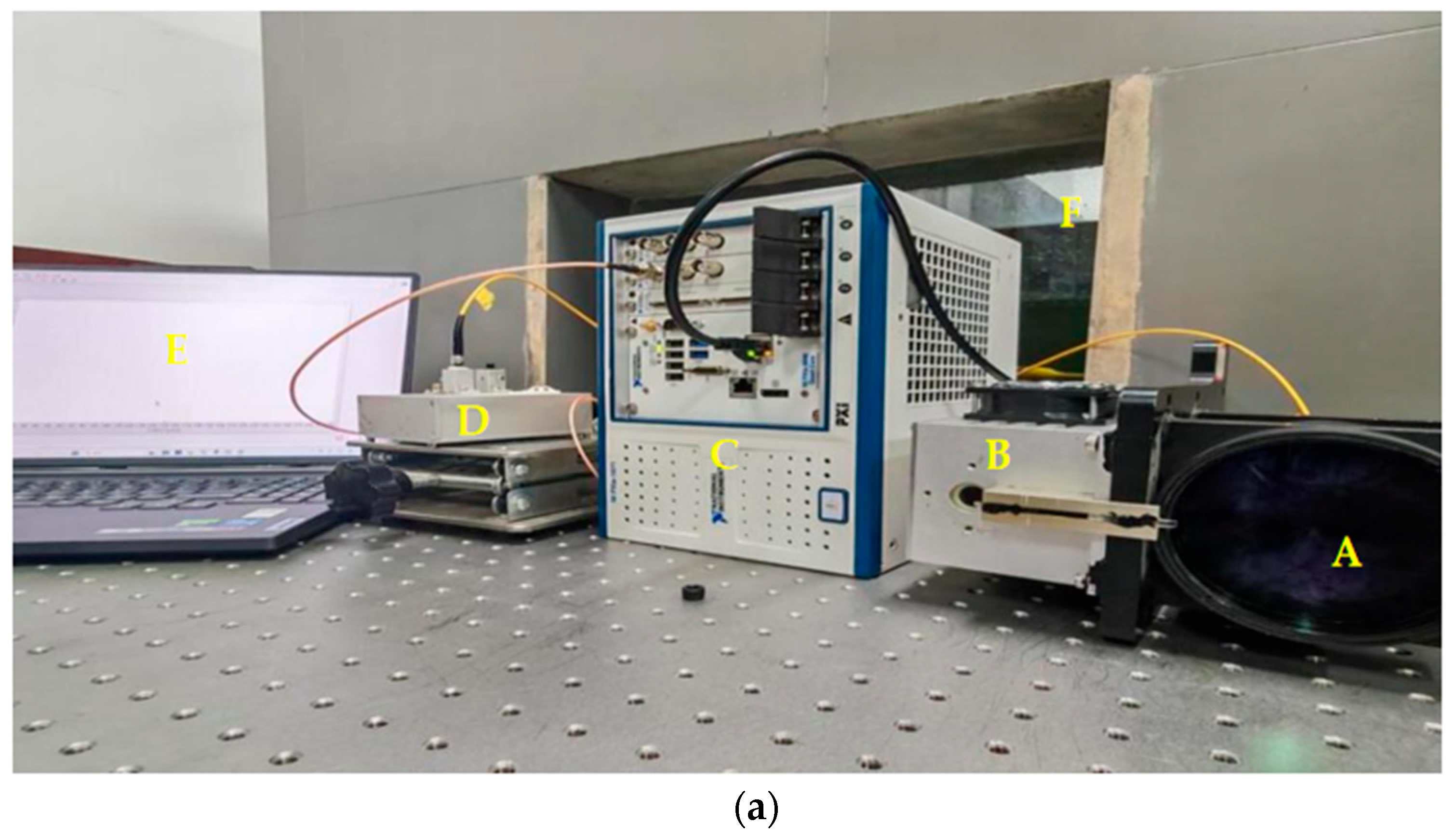

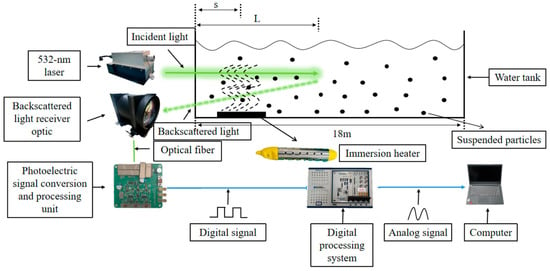

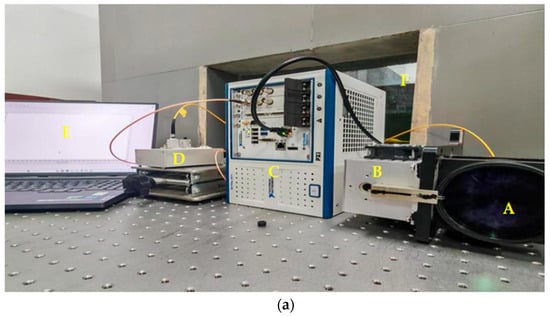

To simulate the actual water conditions in open seas and coastal waters, experiments were performed in environments with turbidities of 0.04 NTU and 0.06 NTU, respectively. A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in Figure 2, which includes a 532 nm laser, a backscattering optical receiver, a photoelectric signal conversion and processing module, a heating rod, a digital controller, a computer, and a water tank. The experiments were conducted in an 18 m (L) × 2 m (W) × 1.5 m (H) water tank. A solid-state laser operating at 532 nm with a pulse width of 8–12 ns was employed. The laser was equipped with a 0.2 mm output aperture and featured an adjustable focal length (10–60 mm), a beam divergence of 1–2 mrad, a tunable repetition rate (10–1000 Hz), and adjustable output energy (5–20 mJ). For this experiment, specific settings were fixed at a 10 ns pulse width, a 10 mm focal length, a 1 mrad beam divergence, and a 1000 Hz repetition rate. The chosen focal length yields a small detection acceptance angle of 1.146°, which helps suppress stray light and allows for more accurate measurement of turbulence-induced signal fluctuations. The polarization state and repetition rate of the laser exhibit no significant effect on measurements under turbulent conditions. The laser used in this study is non-polarized, and no polarizing elements are employed in the experimental setup. Polarization state is therefore not a focus of this work. From the perspective of statistical optics and turbulence propagation theory, the laser repetition rate is not a physical parameter that governs the statistical characteristics of turbulence effects; it primarily influences the sampling density and convergence speed of statistical estimation. In the experiments conducted in this study, the measurement duration was sufficiently long, and the sampling satisfied the signal reconstruction conditions. Therefore, the use of a laser frequency of 1000 Hz does not affect the statistical essence of the turbulence effects. In summary, under the theoretical and experimental framework of this study, laser polarization and repetition rate do not affect the statistical essence of turbulence effects and can therefore be reasonably neglected as non-critical parameters in analysis and modeling. The transceiver system employs an off-axis design to prevent detection errors caused by near-field strong scattering echo saturation and far-field excessively weak echo signals, respectively. The echo signal amplitude was measured using a photoelectric conversion and processing module with a response wavelength range of 300–650 nm and a sensitivity of 110 mA/W. The module’s gain was voltage-controlled, reaching a maximum of . Meanwhile, localized temperature gradients were generated in the water tank by heating rods to induce thermal turbulence. The induced temperature difference in the water body was maintained at approximately 2 °C per cycle, with fluctuations kept within ±0.1 °C. The procedure began with the continuous acquisition of backscattered signal amplitudes via a digital acquisition unit. Following this, the SI was computed using Equation (2) to generate the measured dataset. This dataset was then subjected to a fitting analysis with the theoretical model to quantify the model’s performance in capturing the statistical characteristics of underwater optical transmission. A photograph of the experimental setup is shown in Figure 3, with the components labeled as follows: A: Backscattered light receiver optic, B: laser, C: Digital processing system, D: Photoelectric signal conversion and processing unit, E: Computer, F: Optical transmission window, G: Laser transmission channel, H: Immersion heater. In Figure 2, the parameter represents the single-pass propagation distance of the laser in the aqueous medium, while denotes the distance between the turbulence region and the transmitter. Figure 3a shows a schematic diagram of the constructed experimental system, while Figure 3b,c depict the actual detection scenarios in underwater environments with turbidity levels of 0.04 NTU and 0.06 NTU, respectively. The size of the suspended particulate matter used in the experiments ranges from 20 to 200 μm.

Figure 2.

System block diagram of the experiment.

Figure 3.

Photograph of the experimental setup. (a) A, Backscattered light receiver optic. B, Laser. C, Digital processing system. D, Photoelectric signal conversion and processing unit. E, Computer. F, Optical transmission window. (b,c) G, Laser transmission channel. H, Immersion heater.

3.2. Analysis of Experimental Results Under Simulated Open-Ocean Conditions

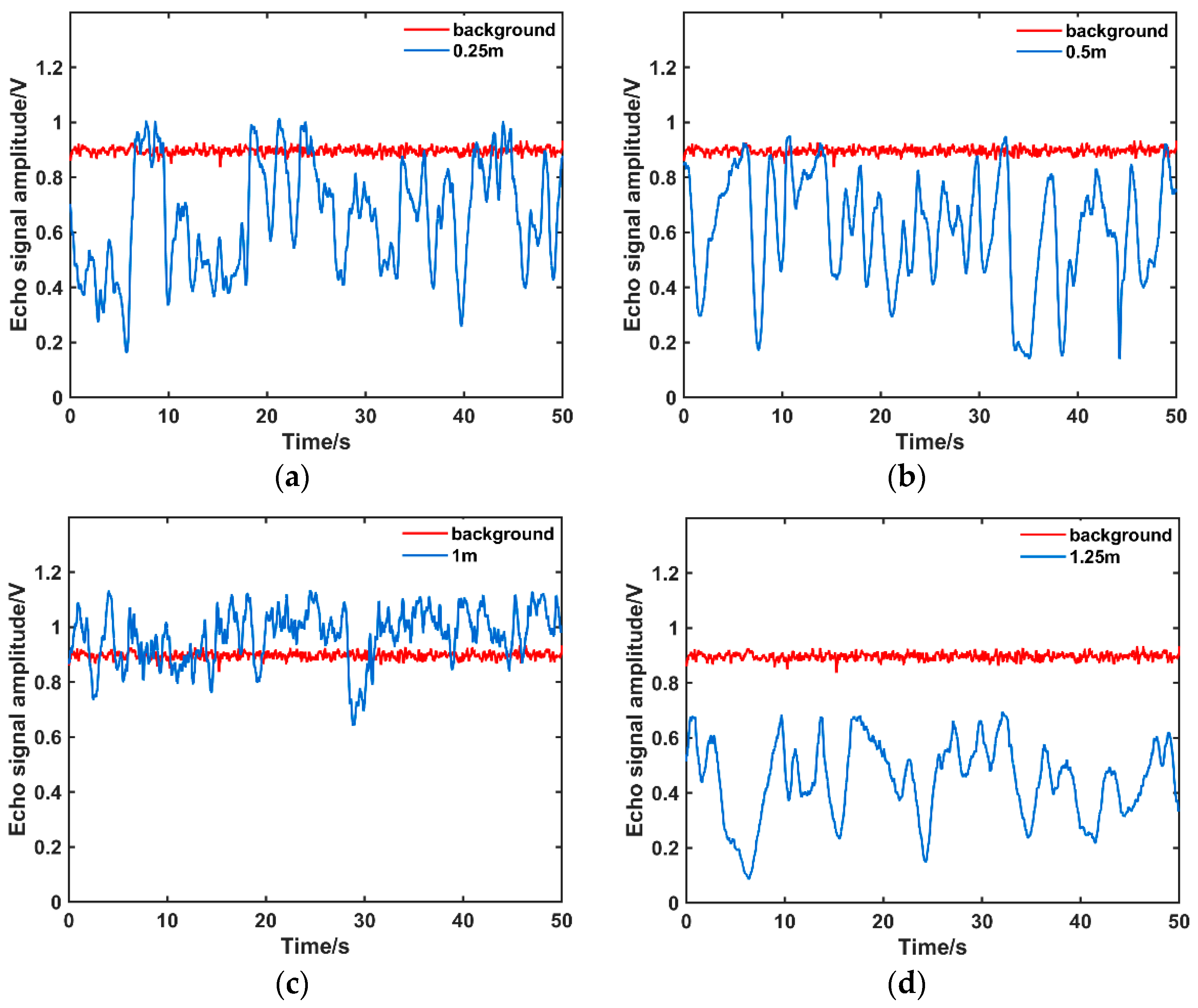

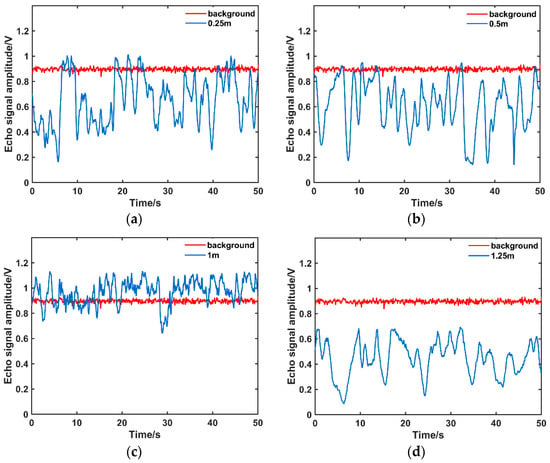

To better simulate the open-sea optical transmission environment, the experiment was conducted in a water medium with a turbidity of 0.04 NTU, and the experimental setup is shown in Figure 3b. A baseline was established by first measuring the backscattered echo amplitude in turbulence-free water using a digital acquisition unit. Echo signals under various turbulence locations—characterized by different temperature gradients—were then systematically collected to build the quantitative model relating turbulence location to the SI. The heating rod was systematically displaced along the beam path within a 2 m range from the laser transmitter, effectively shifting the axial position of the turbulence zone. This enabled the acquisition of echo signal amplitude data at various positions within the turbulent region, relative to the laser transmitter, with representative samples shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(a–d) Echo signal amplitudes of the background and of turbulence at varying laser distances (0.04NTU).

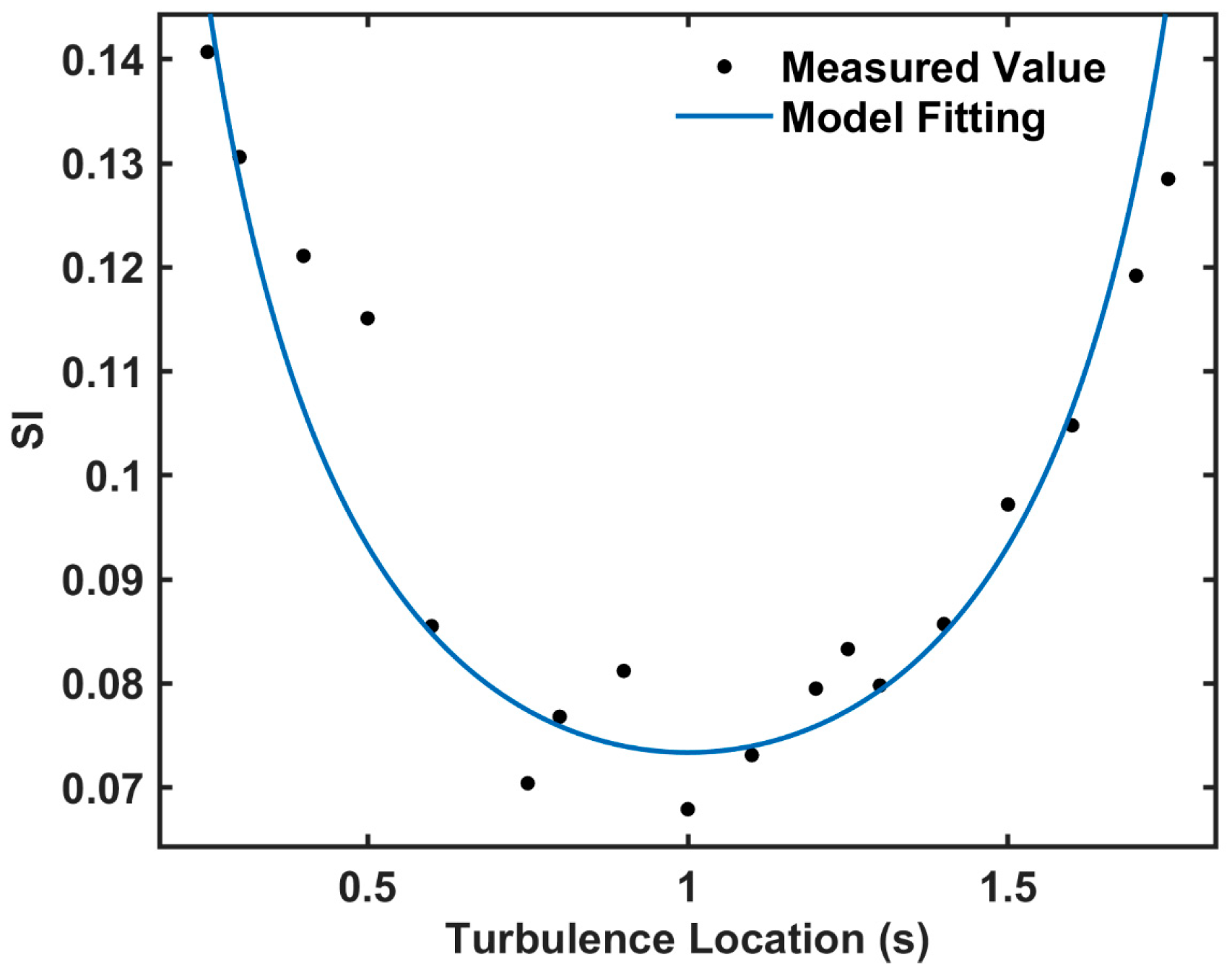

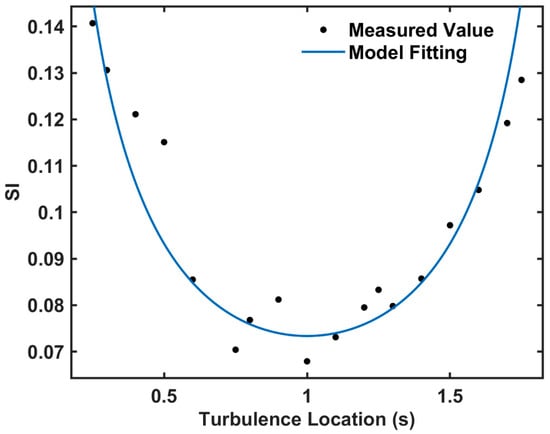

As shown in Figure 4a, when the turbulence was located at 0.25 m, the echo signal amplitude ranged from 0.16 V to 1 V, exhibiting the largest fluctuation range among all measured cases. This is attributed to the laser beam’s premature entry into the turbulent field, where phase perturbations induced by turbulence are continuously amplified during propagation, thereby causing significant beam drift. Corresponding to turbulence locations of 0.5 m and 1 m (Figure 4b,c), the fluctuation range of the echo signal demonstrated a successive decrease, being least extended in the case of Figure 4c. This phenomenon arises because the laser undergoes a period of free-space propagation before encountering the turbulent zone, thereby developing a stabilized wavefront. Although scattering occurs within the turbulence, this pre-formed stability partially suppresses amplitude fluctuations, resulting in lower variability than in the case of proximal turbulence. Moreover, in Figure 4c, the laser beam propagates over a longer distance in free space before encountering turbulence, thereby exhibiting greater wavefront stability and suppressing scattering, which leads to a more stable echo signal. As shown in Figure 4d, when the turbulence was moved farther from the transmitter to a distance of 1.25 m, the voltage amplitude of the echo signal decreased further, even dropping below that of the background echo signal. This phenomenon is attributed to two primary factors. Firstly, the laser beam experiences significant attenuation from water absorption and volume scattering along its extended path through the water before reaching the turbulence. Secondly, the already weak turbulence-induced scattered signals must travel back over the same long path to the receiver, suffering further decay, thereby resulting in a final echo energy lower than the background level. Figure 5 and Table 1 present the measured values of the optical scintillation index alongside the fitting results of the theoretical model, demonstrating a goodness-of-fit R2 of 0.8579. In this analysis, the turbulence structure constant is set as , and the proportionality constant C is 0.231.

Figure 5.

Fitted curve graph of SI value changes under different lateral positions (0.04NTU).

Table 1.

Weights and related parameters (0.04NTU).

As shown in Figure 5, as the distance between the turbulent region and the transmitter increases, the SI value exhibits an overall trend of first decreasing and then increasing. This phenomenon arises from a dual-effect mechanism of turbulence location on the detection process: one related to the laser transmitter, and the other closely associated with the target end. The degradation of laser detection performance by turbulence primarily results from induced beam spatial jitter and scintillation. When the turbulent region is relatively close to the laser transmitter, the spatial beam fluctuation induced by turbulence gradually weakens as the propagation distance increases, resulting in the initial decreasing trend of the SI value. However, as the turbulent region moves farther from the transmitter and approaches the target end (e.g., to a point about 1 m from the receiver), it forms an optical shielding-like structure in front of the detector, thereby enhancing the amplitude scintillation. At this point, the enhancement of this effect outweighs the mitigation of beam spatial fluctuations, leading to intensified overall optical signal disturbance—thus triggering a gradual increase in SI.

3.3. Analysis of Experimental Results in Simulated Offshore Environment

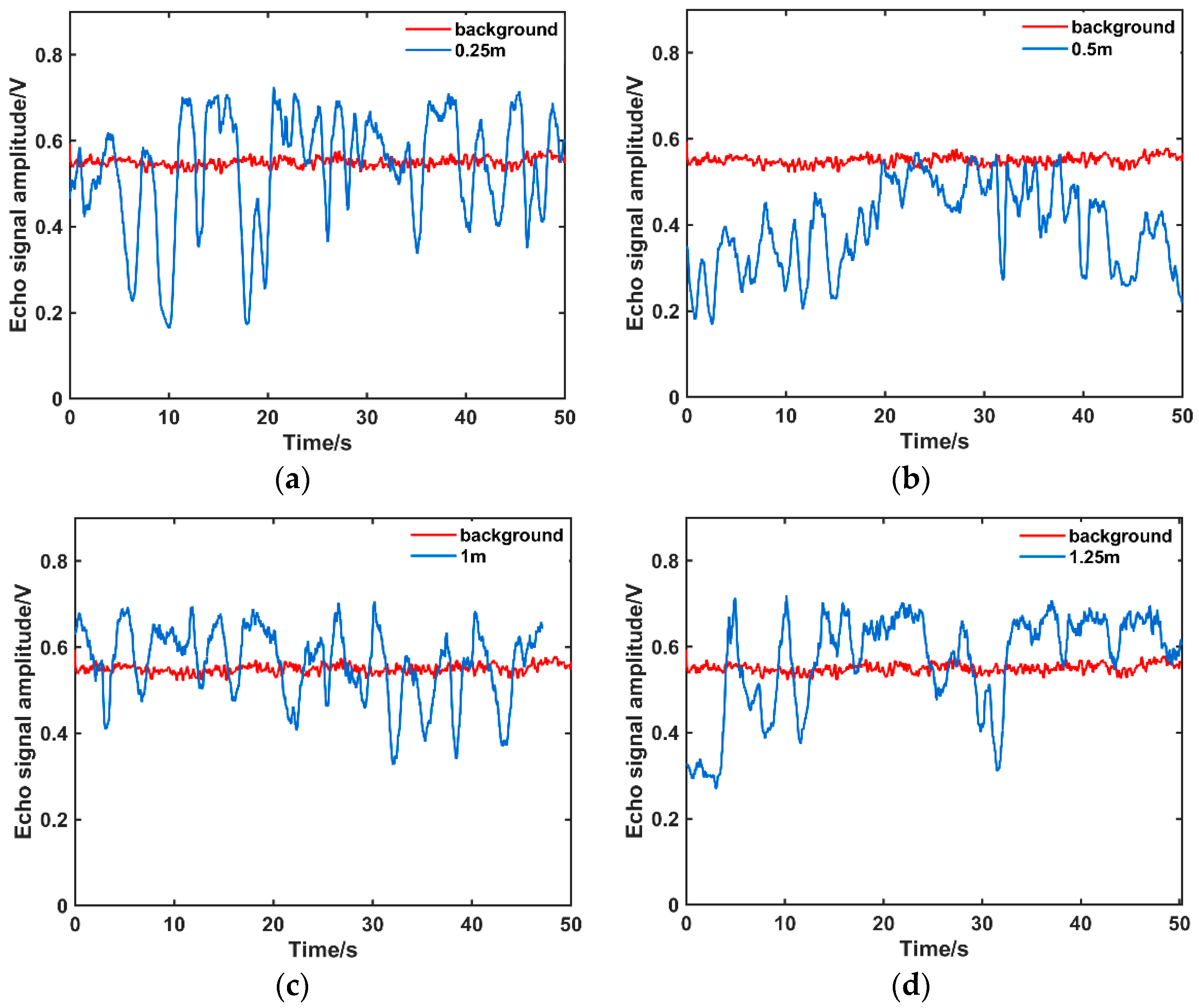

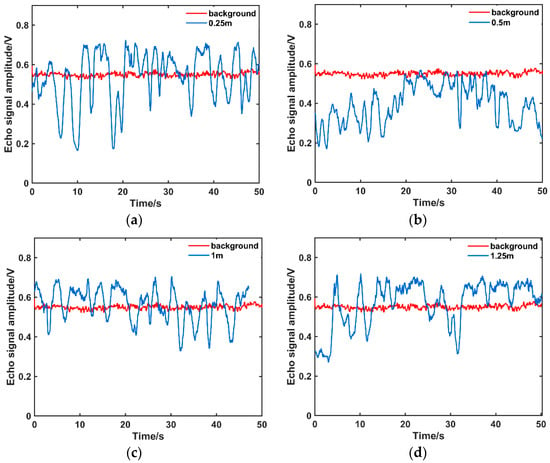

To better simulate the offshore optical transmission environment, the experiment was conducted in a water medium with a turbidity of 0.06 NTU, and the experimental setup is shown in Figure 3c. The heating rod was displaced in steps within a 2 m range from the laser transmitter. The echo signal amplitude was recorded with a digital oscilloscope following each displacement. Representative echo signal amplitudes are shown in Figure 6. The red curve and blue curves represent the echo signal amplitude curves under turbulence-free conditions and under turbulence at varying distances from the laser source, respectively. The corresponding scintillation indices are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

(a–d) Echo signal amplitudes of the background and of turbulence at varying laser distances (0.06NTU).

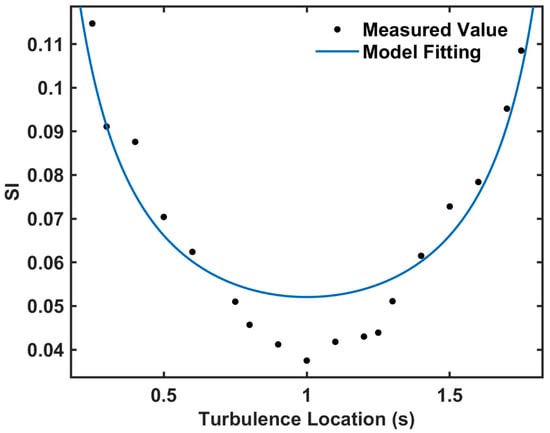

Figure 7.

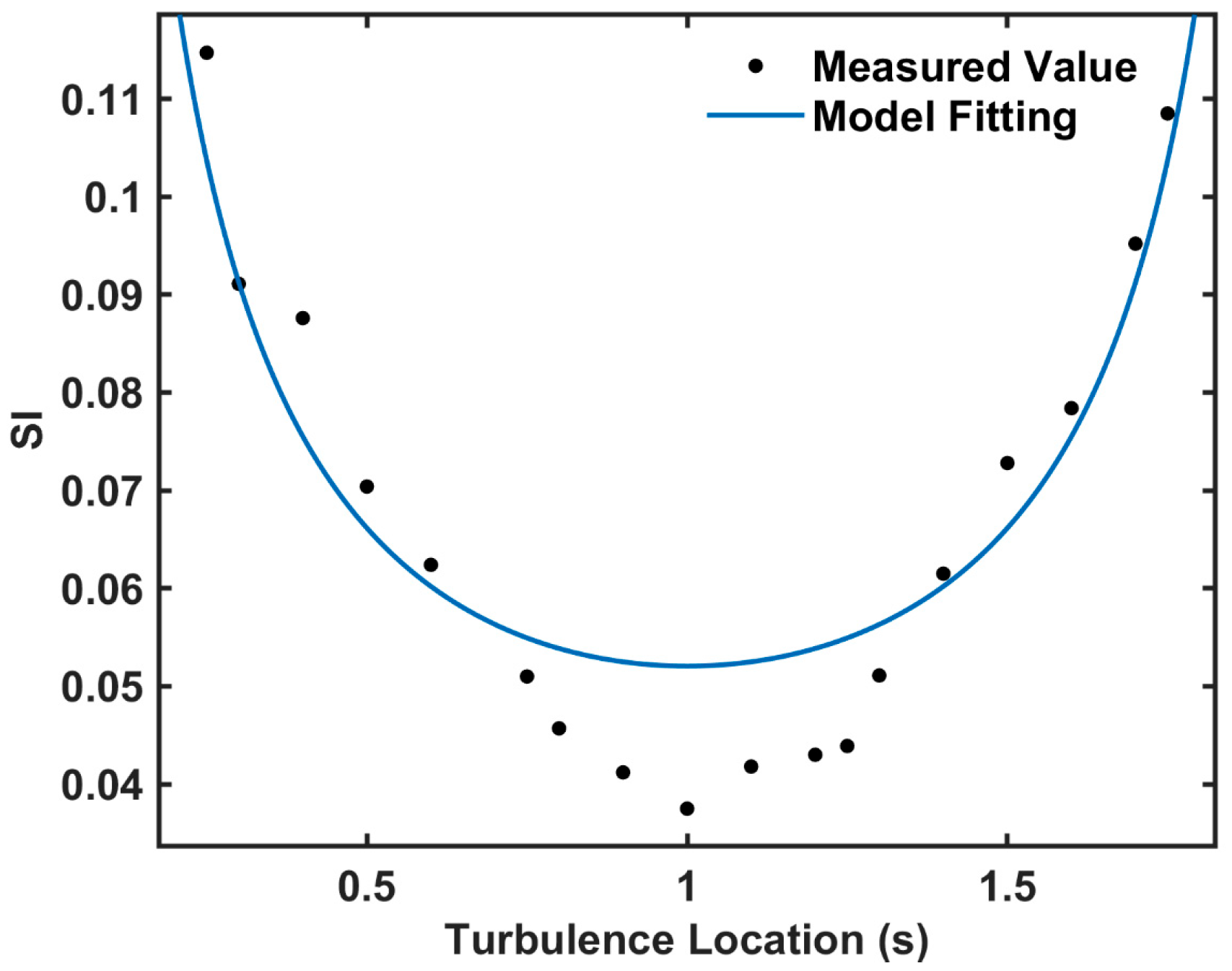

Fitted curve graph of SI value changes under different lateral positions (0.06NTU).

Despite the increase in water turbidity, the data in Figure 6 indicate that the echo signal at the 0.25 m position still exhibits the maximum amplitude fluctuation range, approximately 0.5 V, as presented in Figure 6a. Conversely, the fluctuation range is minimal at the 1 m position (approximately 0.3 V), which aligns with the trends observed in prior experiments. Compared with Figure 4, the echo signal fluctuation amplitudes in Figure 6 are consistently lower across all turbulent positions, with a significantly reduced mean signal level. The reduction in fluctuation range stems from enhanced multiple scattering at higher turbidity, which averages out turbulent fluctuations, while the decrease in overall amplitude is caused by intensified optical attenuation arising from the turbid medium. Moreover, when turbulence is positioned at 1.25 m, the target echo amplitude exceeds the background level. This finding contrasts with the results in Figure 4 and is attributable to the higher water turbidity in the current experiment, whereby the enhanced volumetric scattering generates additional “target-like” echo signals. Although such scattered light does not originate from a specular target surface, its spatiotemporal distribution and fluctuation characteristics allow it to be registered as detectable signals within the receiver’s field of view, thus raising the average signal amplitude at this position. Figure 7 and Table 2 present the measured values of the optical scintillation index alongside the fitting results of the theoretical model, demonstrating a goodness-of-fit R2 of 0.8844, superior to that in Figure 5. In this analysis, the turbulence structure constant is set as , and the proportionality constant C is 0.1639.

Table 2.

Weights and related parameters (0.04NTU).

As shown in Figure 7, the SI in the 0.06 NTU aqueous environment maintains a non-monotonic trend, characterized by an initial decrease followed by an increase. Compared with Figure 5, the SI in Figure 7 exhibits more subdued changes across both decreasing and increasing phases, indicating that while higher turbidity preserves the overall trend, it moderates the rate of these fluctuations. Furthermore, the SI values are systematically lower across all positions. The observed phenomenon is primarily attributed to intensified multiple scattering from suspended particles under elevated turbidity, which degrades the beam’s spatial coherence. This degradation subsequently suppresses the contribution of temperature-induced refractive index fluctuations to intensity variations, thereby mitigating the scintillation effect and ultimately reducing the SI values.

4. Conclusions

Based on the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of turbulent fields and backscattering theory, this study has developed a predictive model for the laser detection backward channel under turbulence interference, quantified the relationship between turbulence location and the SI, and established a reliable assessment method for it. When fitted to the measured data from simulated open-sea and coastal environments, the proposed model yielded R2 values of 0.8579 and 0.8844, respectively, thereby validating its effectiveness and accuracy. The experimental results demonstrate that as the distance between the turbulent region and the transmitter increases, the turbulence-induced interference effects initially weaken and subsequently strengthen, with the corresponding SI showing a consistent trend of first decreasing and then increasing. This occurs because when the turbulent region is close to the transmitter, it induces pronounced beam jitter that severely degrades detection. As the distance increases, this jitter subsides. However, beyond a certain point, the turbulence—now positioned closer to the target—acts as an optical barrier, which, despite the milder beam jitter, becomes the predominant mechanism of interference. The variation in water turbidity leads to a moderated rate of change in the SI values. This model provides an effective theoretical framework for oceanic laser detection in turbulent environments, establishing a foundation for future studies on more complex turbulence conditions and multi-physics effects, thereby advancing the development of this technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.; methodology, J.L.; software, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, M.L.; supervision, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Defense Pre-Research Foundation of China (2020-JCJQ-ZD-099-00-02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, Q.Y.; Yang, K.T.; Wang, X.B. Blue-Green Lidar Ocean Detection; National Defense Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 25–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Duntley, S.Q. Light in the Sea. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1963, 53, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Yang, J.H.; Zhu, B.L.; Han, J.; Dang, W. Short Pulse Laser Drive Technology in a Distance-Selective Imaging System. Chin. Opt. 2023, 16, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zong, S.; Guan, L.; Wang, Y. Extreme Cross-correlation-based Laser Backscattering Detection of Turbulence-coupled Bubble Wakes. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192, 113979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, P.K.; Cohen, I.M.; Dowling, D.R. Fluid Mechanics, 5th ed.; Academic Press (Elsevier): Waltham, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 542–544. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.J.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Y.R.; Li, Y.; Li, L. Three-dimensional reconstruction and analysis of target laser point cloud data in simulated turbulent water environment. Opto Electron. Eng. 2023, 50, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ata, Y.; Kiasaleh, K. Analysis of Optical Wireless Communication Links in Turbulent Underwater Channels with Wide Range of Water Parameters. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 6363–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Alkhazragi, O.; Ng, T.K.; Guo, J.-H.; Ooi, B.S. Impact of Turbulent-Flow-Induced Scintillation on Deep-Ocean Wireless Optical Communication. J. Light. Technol. 2019, 37, 5083–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubei, H.M.; Zedini, E.; ElAfandy, R.T.; Kammoun, A.; Abdallah, M.; Ng, T.K.; Hamdi, M.; Alouini, M.-S.; Ooi, B.S. Simple Statistical Channel Model for Weak Temperature-Induced Turbulence in Underwater Wireless Optical Communication Systems. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 2455–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, W.M.; Chen, B.K.; Xu, J. Study on the backscattering characteristics of laser in the underwater channel. Telecommun. Sci. 2025, 41, 71–77+12. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L. Refractive-index fluctuations spectrum considering the general distribution of turbulence cells in moderate-to-strong anisotropic turbulence. Optik 2018, 154, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkova, O.; Farwell, N.; Shchepakina, E. Light Scintillation in Oceanic Turbulence. Waves Random Complex Media 2012, 22, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedini, E.; Oubei, H.M.; Kammoun, A.; Hamdi, M.; Ooi, B.S.; Alouini, M.-S. Unified Statistical Channel Model for Turbulence-Induced Fading in Underwater Wireless Optical Communication Systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2019, 67, 2893–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, S.; Yang, S.; Liang, S.; Cao, J.; Liu, K. Predictive Mechanisms for Underwater Laser Backward Detection Channel in Bubble-Induced Turbulence. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 189, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fante, R.L. Electromagnetic Beam Propagation in Turbulent Media. Proc. IEEE 1975, 63, 1669–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.C.; Phillips, R.L. Laser Beam Propagation Through Random Media, 2nd ed.; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2005; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, M.V.; Mirani, A.; Parsay, A.; Abolhassani, B.; Nabavi, P.; Chizari, A.; Khorramshahi, P.; Abdollahramezani, S.; Salehi, J.A. Statistical Studies of Fading in Underwater Wireless Optical Channels in the Presence of Air Bubble, Temperature, and Salinity Random Variations. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2018, 66, 4706–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.H.; Lau, S.T. Turbulence Effects on Coherent Laser Radar Target Statistics. Appl. Opt. 1982, 21, 2395–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, R.J.; Clifford, S.F. Modified Spectrum of Atmospheric Temperature Fluctuations and Its Application to Optical Propagation. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1978, 68, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.C.; Phillips, R.L.; Hopen, C.Y. Laser Beam Scintillation with Applications; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vali, Z.; Michelson, D.; Ghassemlooy, Z.; Noori, H. A Survey of Turbulence in Underwater Optical Wireless Communications. Optik 2025, 320, 172126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.