Abstract

Road technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making rely heavily on technical standards whose clauses, computational formulas, and decision logic are often expressed in unstructured formats, leading to fragmented knowledge representation, isolated indicator calculation procedures, and limited interpretability of decision outcomes. To address these challenges, a semantic framework with executable reasoning and computation components, Road Performance and Maintenance Ontology (RPMO), was developed, composed of a core ontology, an assessment ontology, and a maintenance ontology. The framework formalized clauses, computational formulas, and decision rules from standards and integrated semantic web rule language (SWRL) rules with external computational programs to automate distress identification and the computation and write-back of performance indicators. Validation through three use case scenarios conducted on eleven expressway asphalt pavement segments demonstrated that the framework produced distress severity inference, indicator computation, performance rating, and maintenance recommendations that were highly consistent with technical standards and expert judgment, with all reasoning results traceable to specific clauses and rule instances. This research established a methodological foundation for semantic transformation of road technical standards and automated execution of assessment and decision logic, enhancing the efficiency, transparency, and consistency of maintenance decision-making to support explicit, reliable, and knowledge-driven intelligent systems.

1. Introduction

As critical components of national transportation industries, road infrastructures play a vital role in ensuring the efficiency, safety, and sustainable development of transport systems. Assessing and maintaining the technical condition of road infrastructures is essential to sustaining their long-term performance [1,2]. In recent years, advances in information and communication technologies have enabled these assessment and maintenance tasks to evolve toward more refined and intelligent solutions [3,4]. While significantly enhancing management efficiency, road management departments are increasingly confronted with the challenge of integrating massive volumes of heterogeneous data such as inspection results, distress records, and maintenance actions with complex decision-making logic derived from standards, empirical rules, and evaluation systems [5,6].

Particularly, digital tools such as pavement management systems [7], building information modeling platforms [8] and sensor-based monitoring techniques [9] have been widely adopted into road management workflows, but they typically operate with mutually isolated data formats and protocols, resulting in incomplete semantics and limited cross-system interoperability [10,11]. Moreover, current technical standards and maintenance specifications, while widely available, are usually presented in fragmented and unstructured text documents [12,13]. This unstructured nature makes them difficult for machines to interpret, hinders the traceability of evaluation results, and obscures the logic behind decision-making processes. Therefore, within the emerging paradigm of data-driven and intelligent maintenance strategies, enhancing semantic integrity and knowledge-level interoperability has been recognized as an essential step.

Building upon these needs, semantic ontologies have increasingly gained attention in road infrastructure management as a foundational approach for structured knowledge representation and machine-understandable reasoning [14,15,16]. As a formal model that specifies domain concepts, properties, and their relationships, an ontology enables heterogeneous information, such as specification clauses, quality indicators, computational formulas, and inference rules, to be integrated within a unified semantic framework [17,18,19]. This can be leveraged to support an end-to-end modeling pathway that links data, computation, rules, decision outputs, and their corresponding normative justifications.

For example, in the process of assessing road technical conditions, a well-architected ontology can formally represent quality indicators such as the pavement surface condition index (PCI), pavement maintenance quality index (PQI), and highway maintenance quality index (MQI), along with their respective formulas and computational logic. Specifically, the calculation of PCI depends on the pavement distress ratio (DR), which is derived from distress areas and weights over segment area. Within the assessment process, the specific weights assigned to each distress instance are determined by its severity, which is further dictated by basic attributes, such as main crack block size and average crack width for alligator cracking. Despite the multi-layered and nested nature of this process, a systematically constructed ontology can provide explicit conceptualization and attribute definitions for these fundamental properties and formally link these parameters to distress severity levels and quality indicators with explicit traceability to standard clauses. Similarly, in preventive maintenance scenarios for expressways, when a segment satisfies certain conditions, an ontology can formalize the recommendation logic of applying certain maintenance techniques, enabling models to generate decisions that are both actionable and standard-compliant.

Previous studies have introduced several well-developed ontologies in the road infrastructure domain, with research primarily focusing on data exchange within asset management systems [11,20,21], project lifecycle information management [22,23], and road infrastructure data modeling [24,25]. These efforts have preliminarily demonstrated and affirmed the application potential of semantic ontologies in this field. However, most existing ontologies were oriented toward entity classification or data interoperability, lacking structured representations of standard clauses and semantic formalization of decision-making rules. Consequently, they were insufficient for supporting complex reasoning tasks, such as technical condition assessment and maintenance strategy recommendation. In addition, current models generally failed to establish traceable links between inference results and their supporting standard clauses, and they lacked integration with computational models for quality indicator calculation.

To address these gaps, this study focused on the representative tasks of road technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making, and proposed a task-oriented Road Performance and Maintenance Ontology (RPMO). The RPMO formalized key knowledge elements required in practice, including road segment attributes, distress types, quality indicators, computation formulas, maintenance types, decision rules, and their associated standard clauses. By integrating Semantic Web Rule Language (SWRL)-based reasoning mechanisms with external computational models, the proposed framework delivered a comprehensive and executable solution capable of reasoning, computation, and traceability across the full workflow from distress severity inference and indicator computation, through maintenance threshold definition, to maintenance type and technique recommendation. On this basis, this framework can support automated technical condition assessment, intelligent maintenance strategy recommendation, and standard-traceable question answering, while offering strong scalability and engineering adaptability across practical application scenarios.

The remainder of this paper was organized as follows. Section 2 presents a comprehensive review of ontology development methodologies and domain-specific ontologies in the road infrastructure field. Section 3 introduces the six-stage ontology development methodology. Section 4 elaborates on the ontology design and implementation processes. Section 5 validates the ontology performance through three representative use case scenarios. Section 6 discusses the theoretical contributions, engineering applicability, and limitations of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 7 concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Ontology Development and Methodologies

As a structured representation of domain knowledge, ontologies have emerged as a central vehicle for managing and exploiting complex information in knowledge-intensive fields such as medicine, finance, law, education, and engineering [26]. By providing a formalized conceptual system enriched with semantic constraints, ontologies enable interoperable data exchange, knowledge sharing, and automated reasoning across heterogeneous systems [27]. They further support the machine-readable representation of engineering standards, regulatory specifications, and expert experiences. These capabilities collectively establish a robust foundation for information integration and intelligent decision-making in complex engineering scenarios [28,29].

Existing studies generally categorized ontology development approaches into manual, semi-automated, and fully automated paradigms [30,31]. Manual construction relied heavily on the involvement of domain experts and knowledge engineers, who interpreted standards and engineering practices through systematic workflows, such as requirements analysis, concept extraction, and relation definition, to ensure semantic accuracy, internal consistency, and engineering applicability [17,19,22]. With the rapid increase in data volume, automated techniques have been progressively incorporated into the construction pipeline. Semi-automated approaches typically leveraged text mining, semantic annotation, pattern recognition, and machine learning to extract candidate concepts and relations from standards, technical reports, or domain databases, followed by expert validation to balance efficiency and accuracy [32,33]. Fully automated methods further relied on large-scale corpora and pretrained language models to extract conceptual structures from unstructured text; these were often paired with rule engines or knowledge-graph embeddings to identify latent relations and rapidly generate preliminary ontology schemas [34].

Despite the efficiency advantages that semi-automated and automated methods offered, their applicability remains significantly constrained in engineering practices. For instance, in the legal domain, models can automatically identify statutory terminology, yet complex logical constructs such as necessary conditions or exceptions still require expert interpretation [35]. In industrial equipment fault diagnosis, ontologies may assist in identifying event nodes from log data, yet the configuration of causal weights remains heavily reliant on engineers’ experience [36]. In the specialized field of road infrastructure operations and maintenance, the knowledge underpinning technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making was tightly bound to strict industry specifications and standards, involving numerous formula-based technical indicators and complex logical relations, and automated methods found it difficult to ensure semantic accuracy and consistency with standards [37]. Furthermore, road engineering ontologies often encompassed multi-level and multi-scale objects involving rich semantic relationships among components, distresses, inspection indicators, and maintenance measures [38]. Automated approaches still faced limitations in handling these nested entities, hierarchical relationships, and the scarcity of domain-specific corpora [14]. These challenges indicate that expert intervention remains indispensable for semantic calibration, top-level schema design, and the modeling of normative logic. While automation may accelerate data preprocessing and pattern mining, the cognitive backbone of a domain ontology must be manually established to form an “initial trusted knowledge base,” whose rigor and completeness ultimately determine the quality and extensibility of subsequent automated enhancements.

To ensure the normative and scientific integrity of manual ontology development, a variety of mature methodologies have been proposed and validated over the years (as shown in Table 1). Among them, the Skeletal Methodology by Uschold & King [39], as an early initiative, laid the foundational framework for goal-oriented ontology engineering. METHONTOLOGY systematized the ontology development lifecycle, emphasizing a complete process encompassing specification, knowledge acquisition, conceptualization, implementation, and evaluation [40,41]. The On-To-Knowledge Methodology introduced the Ontology Requirements Specification Document (ORSD), highlighting application-driven modeling and proving effective in corporate knowledge management and semantic retrieval contexts [42]. Ontology Development 101 proposed a concise and accessible seven-step approach, widely adopted in educational settings and rapid prototyping [43,44]. More recently, the NeOn methodology addressed distributed and dynamic environments, emphasizing reuse, alignment, and collaborative ontology development to support complex ontology networks [45,46].

Table 1.

Ontology development methodologies.

Table 1.

Ontology development methodologies.

| Methodology | Source | Principles | Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Methodology | [39] | Goal-oriented domain specification | Identify purpose Building the ontology Ontology capture Ontology coding Integrating existing ontologies Evaluation Documentation |

| METHONTOLOGY | [41] | Software engineering lifecycle management concepts | Specification Knowledge acquisition Conceptualization Integration Implementation Evaluation Documentation |

| On-To-Knowledge | [42] | Enterprise knowledge management | Feasibility study Kickoff Refinement Application & evolution |

| NeOn | [46] | Collaboration, alignment, dynamic evolution | Environment and feasibility study Knowledge acquisition Ontology requirements specification Conceptualization Formalization Implementation |

| Ontology Development 101 | [43] | Practical teaching program | Determine the domain and scope Consider reusing existing ontologies Enumerate important terms Define the classes and the class hierarchy Define the properties of classes Define the facets of the slots Create instances |

Given the characteristics of road technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making, where the knowledge to be modeled included standard clauses, quality evaluation indicators, computational formulas, distress types, logical rules, and inference chains, a high level of semantic precision and traceability to official standards was essential. Therefore, a manual development approach was adopted as the foundation, with METHONTOLOGY and NeOn methodologies employed as guiding frameworks to ensure the development of a well-structured, semantically rigorous, reusable, and interpretable ontology system.

2.2. Existing Ontologies in Road Infrastructure Domain

In the road infrastructure domain, several representative ontology frameworks have been proposed and developed to support knowledge management and information integration across different lifecycle stages (summarized in Table 2). These ontologies vary in their scope of knowledge, modeling methodologies, and application validation, each emphasizing different aspects of the domain.

Highway Ontology (HiOnto) [17] was one of the earlier ontology frameworks developed for highway construction, aiming to establish a unified semantic model that integrates road components, transportation facilities, and associated management elements. It adopted a distributed three-layer architecture (domain layer, application layer, and user layer) based on the European e-COGNOS ontology as the upper-level reference. Within this framework, both physical products and managerial products were included in the product category. For instance, maintenance-related entities such as maintenance manual (including preventive maintenance manual and seasonal maintenance manual) were modeled as subclasses of highway management product, providing partial support for condition assessment and maintenance management.

The Integrated Highway Planning Ontology (IHP-ONTO) [10] aimed to establish a shared semantic framework for integrated highway planning by incorporating road facilities, traffic elements, spatial relationships, and project planning processes. For modeling aspects related to condition assessment and maintenance decision-making, IHP-ONTO defined the class pavement section along with its subclasses, including location, traffic volume, condition rating, geometric information, pavement distress, and treatment history. It categorized M&R treatments into three types: preventive maintenance, rehabilitation, and reconstruction, and introduced economic attributes such as environment cost, road user cost, and agency cost. However, this ontology was primarily designed to facilitate inter-project coordination among departments of transportation; formal definitions for the detailed classification of pavement distresses, the computational method for condition rating, or the decision logic for selecting maintenance treatments were not included.

The Road Shared Ontology (RSO) [25] was designed to enable the semantic representation of road infrastructure information through a shared ontology approach. The primary idea behind RSO was to establish a unified semantic framework that captured common concepts across road design, construction, and maintenance domains, thereby serving as a semantic bridge for cross-domain information integration. It adopted a hierarchical structure that classified road assets into three levels: Road, Segment, Subcomponent. A key modeling principle of RSO was the assignment of geometric, material, and functional attributes to segments rather than entire roads, recognizing that different segments may vary significantly in terms of cross-sectional configuration, number of lanes, and pavement structure. This modeling strategy enhanced the ontology’s ability to capture local variations in road characteristics and provided fine-grained data support for condition assessment and maintenance planning.

Building upon RSO, the Road Maintenance Ontology (RMO) [24] extended the TraveledWay entity to include maintenance-specific properties and relationships. It supported the management of distress records, condition assessments, and treatment history, introducing the PCI as a quantitative indicator of segment-level condition. The property RMO:hasRequiredLevelOfService defined the minimum PCI threshold required to trigger maintenance actions. In parallel, the RMO:treatmentHistory property allowed detailed tracking of treatment types, implementation times, and corresponding PCI values, enabling a traceable modeling of maintenance history.

Through this layered architecture of shared and domain-specific ontologies, RSO and RMO mitigated semantic heterogeneity across multi-source databases and formalized critical maintenance concepts such as PCI, distress types, and treatment history into a knowledge framework. However, as summarized in the comparative analysis in Table 2, significant limitations remain regarding their practical executability and normative depth. Firstly, their indicator coverage was centered on PCI and related high-level concepts, whereas key assessment inputs required in practice, such as crack block size and the integrated indicator PQI and MQI, were not modeled as a coherent indicator system with explicit dependencies. Secondly, formula-level representations and the associated threshold conditions were not explicitly embedded in the ontology structure, resulting in inference logic that relies heavily on manual configuration. Thirdly, reasoning capabilities remain limited to simple threshold-based triggers and lack support for multi-criteria integrated decision logic. Therefore, while RSO and RMO represent pioneering efforts in semantic modeling for road management, further expansion and refinement are required.

Table 2.

Representative ontologies in the field of road infrastructure.

Table 2.

Representative ontologies in the field of road infrastructure.

| Name | Domain & Scope | Development Methodology | Ontology Reuse | Evaluation & Validation | Capability Coverage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | I | F | R | T | E | |||||

| Highway ontology (HiOnto) [17] | Highway construction | — | e-COGNOS ontology | Competency questions Experts Survey | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Integrated highway planning ontology(IHP-ONTO) [10] | Highway M&R project planning & inter-project coordination | METHONTOLOGY + Uschold and Gruninger | e-COGNOS ontology | Competency Completeness Conciseness Clarity Consistency | √ | √ | — | — | — | — |

| Road shared ontology (RSO) [25] | Shared road information | Shared ontology approach | — | SPARQL query language | √ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Road maintenance ontology (RMO) [24] | Pavement management | Shared ontology approach | RSO | SPARQL query language | √ | √ | — | √ | — | — |

Note: D: Distress; I: Indicator; F: Formula; R: Rules; T: Traceability; E: External integration.

2.3. Research Gaps

Overall, existing ontologies have achieved notable progress in conceptual system construction and basic reasoning, providing generic frameworks for knowledge modeling in the road infrastructure domain. However, the comparison of capability coverage in Table 2 indicated that the capabilities required for an executable and auditable assessment-to-maintenance workflow were rarely integrated within a single framework. In particular, several limitations remain for supporting standards-aligned technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making:

- Incomplete indicator and distress classification systems: Existing ontologies generally remain at the descriptive level of road components, geometric attributes, and definitions of certain distresses, lacking systematic modeling of the comprehensive indicator system required for technical condition assessment. Core assessment indexes such as PCI, PQI, and MQI lack formalized representations of their mathematical definitions, calculation processes, and threshold conditions.

- Disconnection between assessment and maintenance: Most studies failed to establish a complete semantic chain linking road condition assessment to maintenance action recommendations. Formalized logical connections between evaluation outputs and maintenance strategies were largely absent.

- Lack of formula and computational modeling and insufficient integration with external programs: The computational formulas, threshold conditions, and inference rules underlying technical indicators were seldom explicitly modeled, limiting support for automated indicator computation and condition-based reasoning. Meanwhile, few existing models offer mechanisms for integrating external computational programs directly with the ontology and feeding the results back into the knowledge base to support dynamic inference and decision-making processes.

- Limited traceability to specification clauses: There was a general lack of mechanisms for mapping standard clauses to specific indicators, formulas, and assessment outcomes. This limited the machine-readability and semantic traceability of regulatory content, making it difficult to fulfill the evidence-based requirements of engineering decision-making.

Building on these identified limitations, this study aims to advance ontology-based modeling for road condition assessment and maintenance through the following contributions:

- Establishing a complete indicator modeling mechanism that formalizes not only PCI but also DR, PQI, MQI, and other evaluation indicators, including their computational formulas and threshold conditions, thus supporting complex evaluation logic and calculation-based inference.

- Based on the authoritative technical specifications, clause identifiers and document references will be explicitly embedded, enabling direct mapping between standard documents, semantic models, and knowledge graphs to support traceable and standards-aligned semantic representation.

- Developing a mechanism for integrating formulas and external computational programs, allowing the ontology to invoke external calculation tools for indicator computation and to dynamically update results in the knowledge base, thereby enabling the fusion of knowledge representation and computational processes.

- Constructing a rule-based reasoning framework that employs SWRL rules, SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language (SPARQL) queries, and ontology reasoning engines to transform evaluation results into formalized maintenance decision logic, improving the transparency and explainability of the reasoning process.

3. Ontology Development Methodology

3.1. Methodological Foundation

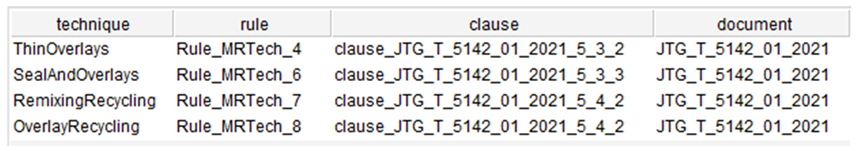

The methodological design of this study was grounded in semantic web technologies and established ontology engineering frameworks. Drawing upon key industry standards, we developed a domain ontology tailored to road technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making. The overall workflow followed the logical sequence of requirement analysis, knowledge acquisition, conceptual modeling, formal implementation, validation, and application. Informed by METHONTOLOGY, the NeOn Methodology, and practical experiences from existing road engineering ontologies, a six-stage ontology development process was designed (as illustrated in Figure 1) to ensure methodological rigor and the accuracy, extensibility, and applicability of the resulting ontology.

Figure 1.

Ontology development methodology.

3.2. Six-Stage Ontology Development Process

3.2.1. Specification

The first stage involved requirement analysis, in which the application objectives of the RPMO were clarified through an in-depth examination of industry standards, representative cases, and current engineering practices. The ontology was expected to support the structured representation of road technical condition evaluation workflows and results, the semantic modeling of distress types and associated severity parameters, and rule-based reasoning for maintenance strategy selection.

To formalize these requirements, we adopted the ORSD to systematically describe the intended functions, core problems, and application scenarios. Meanwhile, as an effective means of defining and assessing the scope of an ontology, employing competency questions (CQs) to delimit modeling boundaries was recognized as a standard practice in ontology engineering [43]. Accordingly, the ORSD included a structured set of CQs that specified the range of inferencing capabilities the ontology must support. The CQs are detailed in Section 4.1 and validated individually in the use case scenarios discussed in Section 5.

3.2.2. Knowledge Acquisition & Reuse

Second, during the knowledge acquisition and reuse stage, relevant concepts and relations were derived from technical standards, specification tables, domain terminologies, and existing ontologies. Authoritative knowledge sources within the road engineering domain were systematically collected and consolidated, with particular emphasis on current industry standards. For example, Highway Performance Assessment Standards (JTG_5210_2018) defined pavement distress categories together with their evaluation indicators and grading rules [12]; Technical Standards for Highway Maintenance (JTG_5110_2023) specified the technical requirements and strategic guidelines for highway maintenance activities [13]; and Specifications for Maintenance Design of Highway Asphalt Pavement (JTG_5421_2018) outlined the design principles and computational procedures for asphalt pavement maintenance [47]. These standard documents constituted the primary knowledge foundation of the ontology, ensuring that its content remained both normative and comprehensive.

In parallel, existing ontologies and semantic models relevant to road infrastructure management were surveyed to support knowledge reuse and alignment. As aforementioned in Section 2, published models such as the RSO, RMO, and IHP-Onto provided valuable precedents. These existing models were examined to avoid unnecessary reinvention, and their conceptual structures informed the categorization and relational design adopted in this study. General concepts (e.g., RSO:Road, RSO:Segment) were reused directly to preserve semantic interoperability, while still allowing the ontology to be adapted and refined for the specific analytical and operational requirements of road maintenance.

In addition to documentary sources, expert experience was incorporated as a complementary knowledge source to support ontology development. Expert consultations were conducted with four road maintenance practitioners to delimit the scope and coverage of the ontology and to confirm the competency questions (CQs) that specify the required modeling and reasoning capabilities. The elicited expert inputs were consolidated into the ORSD artifacts and subsequently used to refine the conceptualization and formalization of classes, properties, and rule constraints.

3.2.3. Conceptualization

In the conceptualization stage, the knowledge gathered in the previous stage was structured into a coherent conceptual model, defining the ontology’s classes, properties, and relational architecture. The conceptual design emphasized three key aspects:

- Modular architecture

The RPMO was organized into a structured hierarchy that comprised three coordinated modules: a core ontology, an assessment ontology, and a maintenance ontology. Specifically, the core ontology defined foundational road assets and distress types to facilitate domain modeling; the assessment ontology evaluated technical indicators and condition ratings to support quantitative analysis; and the maintenance ontology integrated decision logic to recommend treatment strategies. These modules were interconnected through shared concepts and properties, articulating a clear and logically interpretable chain connecting physical road segment conditions, quantitative assessments, and maintenance decision-making.

- Clause traceability design

To guarantee transparency and interpretability in the reasoning process, traceability to specifications was explicitly incorporated into the ontology. Clauses from technical standards were modeled as instances of a dedicated class named StandardClause. Two properties, fromClause and sourceDocument, were introduced to link ontology entities or rule instances to their corresponding clause numbers and source documents. For example, an assessment rule “If a distress instance is classified as alligator cracking with a main crack block size between 0.2 and 0.5 m and an average crack width ≤ 2 mm, then the distress severity is light” was linked through fromClause to clause_JTG_5210_2018_5_2_1. Consequently, when an inference engine applied this rule to classify a distress instance, the system can retrieve and display the exact standard justification for that conclusion.

- Formula representation and external program integration

Road condition assessment and maintenance design involved numerous quantitative computations, some of which were not directly expressible within Web Ontology Language (OWL)-based logical formalisms. To accommodate these requirements, the RPMO employed a hybrid integration framework to decouple semantic reasoning from numerical computation. Formula entities and their associated properties were introduced to store mathematical expressions and reference identifiers, which served as the semantic foundation for external processing. Within this framework, the ontology defined the semantics of input and output parameters, while the numerical computations were carried out by an external Python program (version 3.12). The results, such as the DR derived from distress measurements, were then written back into the ontology as data assertions.

3.2.4. Formalization & Implementation

In the formalization stage, the conceptual model developed earlier was implemented using a formal representation language. The ontology was encoded according to the OWL 2 DL specification using Protégé 5.6.7, which served as the primary tool for constructing class hierarchies, defining property relations, and specifying logical constraints. The core concepts and relations were first entered into Protégé, after which OWL axioms were used to articulate the intended semantics and applicable conditions of each concept with precision.

For reasoning, SWRL was employed to translate quantitative decision conditions into explicit logic. For example, the rule “If the MQI of a given segment is less than 60, then the indicator level of this segment is very poor”, was represented as “RSO:Segment(?s) ^ rpmo:hasMQI(?s, ?mqi) ^ swrlb:lessThan(?mqi, 60) -> rpmo:hasMQILevel(?s, rpmo:VeryPoor) ^ rpmo:evidencedBy(?s, rpmo:MQILevel_5)”. Such rules enabled the inference engine to assign condition ratings automatically based on the values recorded in instance data. Meanwhile, the description logic reasoner Pellet was continuously used to verify model consistency and ensure no logical conflicts were introduced throughout the formalization process.

3.2.5. Instantiation

Subsequently, during the instantiation phase, data instances were imported into the ontology in batch to construct the knowledge base. This was accomplished in Protégé using the built-in Cellfie module, where load rules were specified to map excel data into ontology individuals. Representative highway segments and their inspection records were selected as the source of instances.

3.2.6. Verification & Evaluation

In this stage, the ontology underwent comprehensive quality checking and functional verification. At the technical level, a description logic reasoner was employed to perform consistency checking and inference testing, ensuring that no logical conflicts or modeling errors were present. After loading instantiated case data, SWRL rules and OWL axioms were executed to confirm that intermediate inferences (e.g., severity, prerequisite parameters, and rule-trigger conditions) matched the intended semantics.

At the application level, the CQs defined in ORSD were revisited, and three use case scenarios were employed to evaluate whether the ontology could adequately support these questions. Within each scenario, the correctness of indicator computation and decision outputs was validated against an independently derived, standards-based ground truth. Specifically, a verification panel consisting of four domain experts in road maintenance and two graduate students independently performed manual derivations following the same technical standards and the same input inspection records; discrepancies were reconciled through panel discussion. The complete dataset, including raw inspection records and the finalized reference values used for validation (highlighted in red), was provided in Supplementary Material Table S2 Input Data. By constructing SPARQL queries and performing reasoning-based querying, the ontology was tested on its ability to answer these questions. The successful resolution of these queries can demonstrate that the ontology fulfilled the functional requirements established during the requirement analysis stage, while the ground truth comparison verifies the accuracy of the computed and inferred results.

4. Ontology Design and Implementation

4.1. Ontology Requirements Specification Document (ORSD)

To ensure the ontology development process maintained clearly defined boundaries and verifiable objectives, a structured ORSD was used to guide and constrain the modeling processes. The structured components of the ORSD are summarized in Table 3.

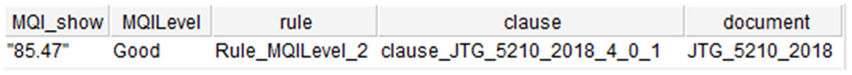

A key component of the ORSD was the CQs that defined the inferential capabilities the ontology must support. Examples include: “How severe is the distress observed on the segment? What are the DR, PCI, PQI and MQI values of the Segment?” which corresponded to integrated condition assessment and severity identification; “What is the MQI level and which rule and standard clause support it?” which reflected the application and the traceability of evaluation rules; “Based on the technical condition indicators, which maintenance type is recommended? Which document and clause support this decision?” which concerned maintenance strategy selection and the traceability of decisions. Taken together, these questions span evaluation, decision-making, traceability, and analytical interpretation, thereby defining the functional requirements against which the ontology was subsequently verified.

Table 3.

Ontology Requirements Specification Document (ORSD).

Table 3.

Ontology Requirements Specification Document (ORSD).

| Domain & Scope | |

|---|---|

| Domain | Road technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making |

| Scope | Semantic representation of road structure, distress, quality indicators, calculation formulas, evaluation rules, and standard clauses references |

| Aim & Goals | |

| Aim | Provide a consistent, inferable, and traceable knowledge model for road maintenance |

| Goals |

|

| Knowledge Sources | |

| Industry standards | Highway Performance Assessment Standards (JTG_5210_2018) |

| Technical Standards for Highway Maintenance (JTG_5110_2023) [13] | |

| Specifications for Maintenance Design of Highway Asphalt Pavement (JTG_5421_2018) [47] | |

| Technical Specifications for Preventive Maintenance of Highway Asphalt Pavement (JTG_T_5142_01_2021) [48] | |

| Published ontologies | RSO, RMO, IHP-ONTO |

| Expert experiences | Interviews with engineering experts |

| Case data | Pavement inspection reports |

| Users & Scenarios | |

| Users | Engineers and decision-makers in road management departments |

| Developers of road management systems | |

| Standards setting and regulatory bodies | |

| Researchers | |

| Scenarios | Technical condition assessment |

| Decision support for road maintenance | |

| Knowledge querying and professional training | |

| Cross-system data integration | |

| Competency Questions | |

| CQ1 | How severe is the distress observed on the segment? |

| CQ2 | Which standard clause and standard document does the CQ1′s inference rely on? |

| CQ3 | What distress types are defined for asphalt pavement? |

| CQ4 | How are the weight of alligator cracking chosen for DR? |

| CQ5 | What are the DR, PCI, PQI and MQI values of the Segment? |

| CQ6 | What is the MQI level and which rule and standard clause support it? |

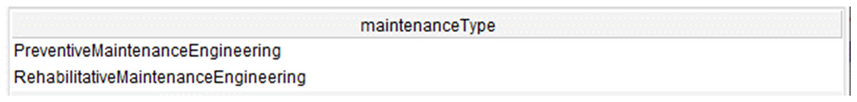

| CQ7 | What maintenance types are modeled in the ontology? |

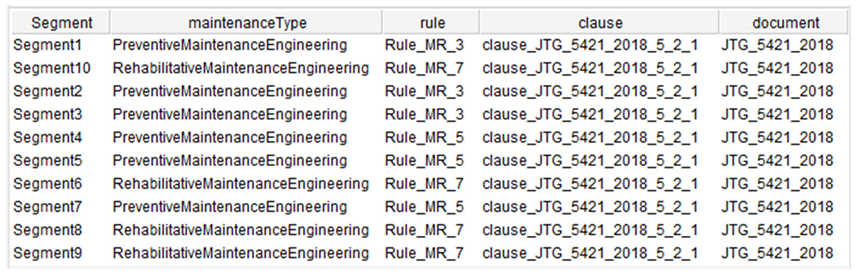

| CQ8 | Based on the technical condition indicators, which maintenance type is recommended? Which document and clause support this decision? |

| CQ9 | If preventive maintenance is required for the segment, which preventive-maintenance technology is recommended? Which document and clause support this? |

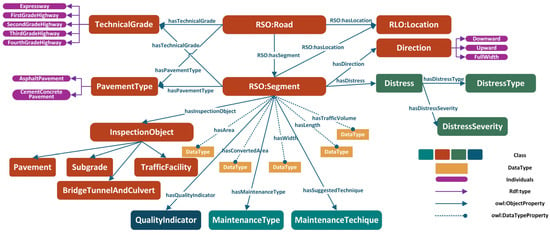

4.2. Concept Extraction and Knowledge Acquisition

The construction of the ontology relies fundamentally on the clear, systematic identification and structuring of domain concepts. In this study, concept extraction denotes the systematic identification and compilation of candidate domain concepts and relationships from technical standards, specification tables, and the ORSD requirements, with the objective of supporting the entire knowledge flow from technical condition assessment to maintenance strategy formulation. Through structural decomposition, complex and fragmented standard provisions were transformed into semantically explicit concepts and relations. The process focused on extracting key definitions, parameter constraints, indicator systems, evaluation rules, and intervention measures embedded within the road technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making workflow. Guided by the scope and knowledge sources defined in the ORSD, we distilled a candidate concept set for subsequent ontology conceptualization and model design (Section 4.3). The resulting structured concept set was organized into seven core dimensions, as illustrated in Figure 2. Specific colors were assigned to each dimension: red for road basic attributes, green for distress types and parameters, dark teal for technical condition indicators, blue for formulas, teal for maintenance and treatment techniques, yellow for standard documents, and orange for rules; this color-coding scheme was applied consistently throughout all subsequent figures.

Figure 2.

Core concepts for ontology modeling.

- Road basic attributes, including concepts such as road, road segment, technical grade, pavement type, and structural layers, which together provided the contextual basis for all assessment and decision-making activities.

- Technical condition indicators. This dimension covered the highway maintenance quality index, MQI; the component indicators for subdomains such as the subgrade (SCI), pavement (PQI), bridges and tunnels (BCI), and roadside facilities (TCI); and detailed pavement indicators such as the pavement surface condition index, PCI, the pavement riding quality index, RQI, and the pavement rutting depth index, RDI.

- Distress types and parameters. These encompassed the characteristic distress categories for subgrade, asphalt pavement, and cement concrete pavement, as well as the associated parameters for severity determination, including area, length, depth, and width, along with their corresponding threshold values.

- Standard documents and clauses. This included the representation of standard documents and their clause identifiers, which allows the ontology to maintain explicit links to authoritative specifications.

- Maintenance types and treatment techniques. The ontology formalized the taxonomy of maintenance activities, including routine maintenance, routine repair, preventive maintenance, rehabilitative maintenance, special maintenance, and emergency maintenance. Representative preventive maintenance techniques were also incorporated to support decision-making tasks.

- Key computational formulas and parameters. This dimension included formulas and parameters such as the weighted combination used in MQI calculation and the calculated formulas for DR and PCI, together with the indicators, coefficients, and standard clauses involved.

- SWRL rules. These rules described critical reasoning procedures, including the determination of distress severity, the selection of parameter weights used in indicator computations, and the inference of appropriate maintenance categories and recommended treatment technologies based on indicator thresholds.

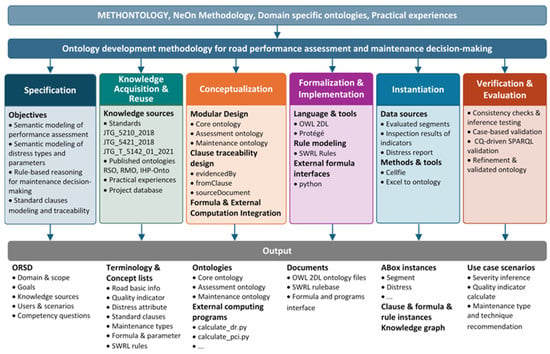

4.3. Conceptualization & Model Design

To organize the seven categories of core concepts identified in Section 4.2 into a structured and interoperable semantic system, the Road Performance and Maintenance Ontology (RPMO) was developed as a modular semantic framework, using the base IRI <http://www.semanticweb.org/RPMO> and the prefix rpmo: for its concepts and properties. The resulting RPMO consisted of three coordinated modules: a core ontology for foundational concepts, an assessment ontology for technical evaluation knowledge, and a maintenance ontology for maintenance strategies (as shown in Figure 2). Although each module served a distinct function, they were interconnected through shared concepts and properties, together forming a unified ontological network.

Within this modular semantic framework, the design of RPMO followed a class-centered ontological modeling pattern. In this pattern, domain concepts that shared a unified metadata structure and function as semantic categories, such as DistressType and IndicatorLevel, were defined as classes, whereas predefined, non-decomposable classification items explicitly specified in technical standards, such as AlligatorCracking and Excellent, were modeled as named individuals. This modeling choice avoids unnecessary class proliferation, improves reasoning efficiency, and ensures a logically rigorous knowledge hierarchy while maintaining concise and efficient instance-level assertions.

Based on this modeling pattern, several principles for class hierarchy design were followed to optimize the ontology structure. First, the principle of conceptual clarity was emphasized: each class was assigned a well-defined semantic scope and unambiguous boundaries, with distinct hierarchies between different classes so they did not overlap or cause confusion. For example, AlligatorCracking and Rutting were represented as distinct individuals of the class DistressType, and a given Distress instance was associated with only one distress type individual via the hasDistressType property. The second was the principle of minimal redundancy. Concepts that were required by both the assessment ontology and the maintenance ontology, such as the Segment, were modeled in the core ontology so that a single authoritative definition could be shared across modules. Third, naming consistency was ensured by standardizing class and property names in English using clear and technically interpretable terms, with CamelCase conventions adopted for class names (e.g., DistressType and StandardClause). Finally, the principle of extensibility guided the design by reserving appropriate abstraction levels to accommodate future expansion. For example, although the present work focused primarily on asphalt pavement maintenance, an abstract classification node PavementType was introduced, and the applicableToStructure property was defined for distress types, enabling straightforward extension to cement concrete pavement specific distress types and maintenance measures.

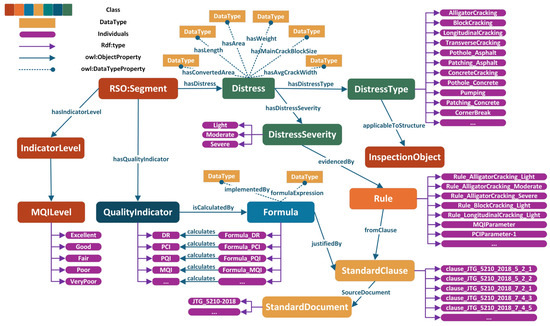

4.3.1. Core Ontology

As illustrated in Figure 3, the core ontology defined the shared concepts and general relationships that underpin the road maintenance domain and served as the common foundation for both the assessment ontology and the maintenance ontology. Within the core ontology, abstract representations of road entities were established as classes, including Road and Segment, as well as infrastructure components such as Pavement, Subgrade, TrafficFacility, and BridgeTunnelAndCulvert, which together provided a unified semantic description of inspection objects associated with road segments. Fundamental classification concepts, such as TechnicalGrade and PavementType, were also modeled as classes and linked to road or segment entities through object properties, while their concrete classification values (e.g., Expressway or AspkaltPavement) were represented as named individuals.

Figure 3.

Core ontology.

Concepts that were required by both the assessment and maintenance modules were likewise defined at this foundational level to ensure semantic consistency across modules. For example, Distress was modeled as a general class for structure deterioration, without embedding specific classification logic in the core ontology. The categorization of distresses was instead captured through the DistressType concept, which functioned as a classification class whose predefined standard categories (e.g., AlligatorCracking) were modeled as named individuals and associated with instances under the Distress class via the hasDistressType property. Similarly, QualityIndicator was defined as an abstract class representing quantitative measures of road condition, while the concrete indicators and their associated evaluation logic were formalized within the assessment ontology.

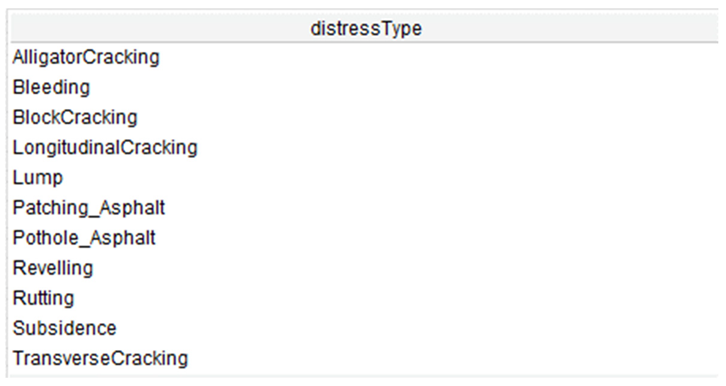

4.3.2. Assessment Ontology

The assessment ontology extended the core ontology by providing a specialized representation of the knowledge structures required for road technical condition assessment, as shown in Figure 4. One major component of this ontology was the formalization of pavement distress classification. Building on the general class of Distress defined in the core ontology, the assessment ontology refined this concept according to the categories prescribed in the standard. Distress types such as AlligatorCracking, TransverseCracking, BlockCracking, Rutting, and Potholes were introduced as named individuals under the class DistressType. Each Distress instance was linked to exactly one DistressType individual through the object property hasDistressType, thereby enabling explicit and unambiguous distress classification while avoiding unnecessary class proliferation. Each Distress instance was further associated with specific attributes that characterize its severity, such as AvgCrackWidth, MainCrackBlockSize and ConvertedArea. These attributes were represented as data properties and served as input parameters for rule-based reasoning on distress severity.

Figure 4.

Assessment ontology.

In addition, the assessment ontology formalized the set of technical condition indicators and their computational formulas. A dedicated class, QualityIndicator, was established to represent the various performance metrics. Each indicator instance captured its numerical values through data properties and linked to its corresponding computational procedure through the object property calculatedBy, which linked the indicator to an instance of the class Formula. Formulas such as Formula_DR, Formula_PCI, Formula_PQI, and Formula_MQI were represented as named individuals of the Formula class. Their analytical expressions were captured using the data property formulaExpression. Each formula instance was further linked to its authoritative standard clause through the justifiedBy relation (discussed in Section 4.4), and to the external computation modules through the implementedBy relation, further explained in Section 4.5.

The assessment ontology also included a conceptual model for indicator-based condition levels. Based on the grading schemes defined in the technical standards, an IndicatorLevel class was created to represent ordered condition levels. Concrete grading levels were modeled as named individuals of this class. For example, the indicator levels associated with the MQILevel included Excellent, Good, Fair, Poor, and VeryPoor. This design enabled grading results to be inferred and queried at the instance level while maintaining a stable and extensible classification structure.

A further component of the assessment ontology concerned the representation of assessment rules. A class named Rule was defined to organize rule instances that encoded logical relationships between indicator values, distress attributes, and inferred condition levels or distress severity. Typical rules included statements such as: “If the MQI of a road segment is greater than or equal to 90, then the MQILevel of the segment is inferred to be Excellent” and “If a distress instance is classified as alligator cracking, and its main crack block size lies between 0.2 and 0.5 m while its average crack width does not exceed 2 mm, then its severity level is Light”. Although OWL alone cannot express such procedural logic, these rules can be executed by the reasoning mechanisms described in Section 4.6 once the required conceptual structures are defined in the ontology.

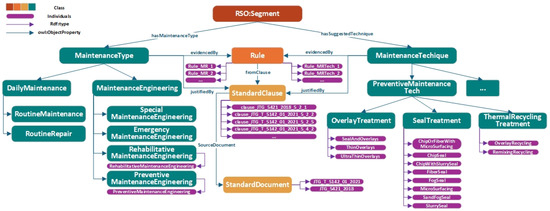

4.3.3. Maintenance Ontology

The maintenance ontology focused on representing the knowledge required for maintenance strategy selection, as illustrated in Figure 5. Building upon the road structure framework defined in the core ontology, it first established a classification system for maintenance measures. Following the structure provided in standards, maintenance activities were organized into several hierarchical levels. At the highest level, two broad categories were distinguished: daily maintenance and maintenance engineering. The latter was further divided into emergency maintenance engineering, preventive maintenance engineering, rehabilitative maintenance engineering, and special maintenance engineering. Within these categories, specific maintenance techniques were identified, and preventive maintenance techniques were further organized into seal treatments, overlay treatments, and thermal recycling treatments. These categories were readily extensible as future requirements emerged. Each maintenance technique was modeled as a class or a named individual within the ontology and could be associated with descriptive attributes, such as materials required, applicable conditions, and cost levels.

Figure 5.

Maintenance ontology.

The maintenance ontology also modeled the decision rules that linked road condition assessments to appropriate maintenance measures. For example, rules may specify that preventive maintenance should be recommended when a segment has a PCI of at least 90, an RQI of at least 90, an RDI of at least 80, and an SRI below 75. To formalize these rules, under the class Rule, individual rule instances defining the logical relationships between condition indicators and recommended maintenance actions were created. Through object properties such as hasMaintenanceType and hasSuggestedTechnique, these rules connected evaluation results or distress conditions from the assessment ontology to the corresponding maintenance classes. An example rule stated: “If a segment recommended for preventive maintenance has a PCI greater than or equal to 93, an RQI greater than or equal to 93, and an RDI greater than or equal to 93, then the recommended maintenance technique is SandFogSeal”. Additional contextual properties, such as traffic volume or pavement age, could be incorporated to refine the applicability of decision rules.

To ensure transparency and traceability, the maintenance ontology incorporated the object property evidencedBy, which linked maintenance rules or inferred recommendations to their supporting clauses in technical standards. This mechanism enabled each recommended maintenance action to be explicitly traced back to its normative basis, as further detailed in Section 4.4.

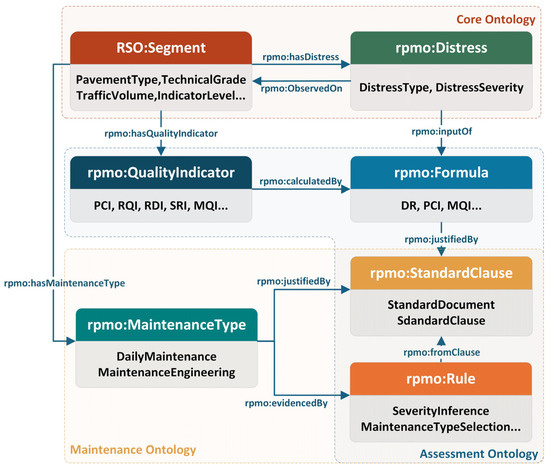

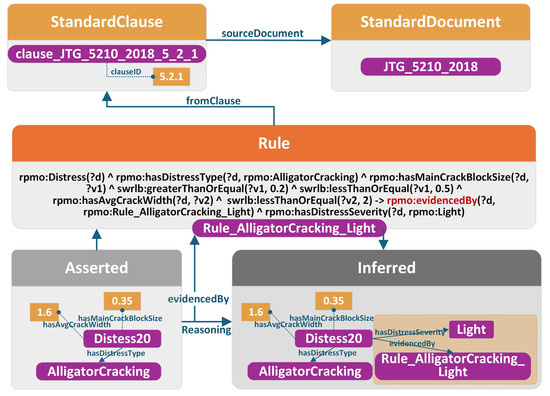

4.4. Clause Traceability Mechanism

To ensure that technical condition assessment and maintenance decision-making remain transparent, standardized, and interpretable, this study developed a clause traceability mechanism (as illustrated in Figure 6). This mechanism enables the reasoning system to not only generate computational results but also articulate the underlying rationale, bridging the gap between automated inference and standards clauses.

Figure 6.

Clause traceability mechanism.

In traditional workflows, while conclusions can be generated for a given road segment, the standards-based justification remains largely inaccessible. For instance, as shown in Figure 6, without explicit traceability, the system might infer that the severity of Distress20 is Light but would be unable to demonstrate that this conclusion is grounded in clause 5.2.1 of JTG_5210_2018. Therefore, the purpose of this mechanism was to establish explicit semantic links between the conclusions produced by the inference engine and their underpinning normative clauses, forming a complete evidential chain that connects the inference result, the logical rule, the originating clause, and the standard document.

The central idea of this mechanism involved formally structuring the knowledge contained in technical standards and embedding it within the reasoning workflow. In the RPMO, standard documents (e.g., JTG_5210_2018) and their specific normative clauses (e.g., clause_JTG_5210_2018_5_2_1) were modeled as instances of the StandardDocument and StandardClause classes, respectively. Each clause instance contained properties such as clauseID and sourceDocument, enabling the clause to function as a discrete, citable semantic unit. At the same time, all inference rules used for distress classification, indicator level assignment, index computation, or maintenance treatment selection were modeled as individuals of an SWRLRules class. These rules were linked to their respective source clauses through the object property fromClause. In this way, the logic embedded in the rules became a formalized expression of the corresponding standard, and the content of the standards was semantically mapped into the reasoning architecture.

During the reasoning process, inspection data and distress observations enter the model as factual assertions, triggering the relevant SWRL rules to produce assessment or decision results. For each generated result, the ontology automatically assigned an evidencedBy attribute that recorded the specific rule responsible for the inference. Since each rule was already linked to its originating clause, the system could automatically assemble a complete traceability path. Furthermore, SPARQL queries could be utilized to retrieve both the inference results and their supporting evidence, providing a unified and explainable interface for decision visualization and auditability.

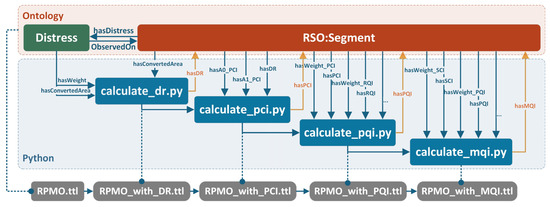

4.5. Formula & External Computation Integration

Due to the inherent limitations of ontology languages in handling complex mathematical operations, technical condition indicators, such as DR, PCI, PQI, and MQI, cannot be computed efficiently within a native ontology environment. These evaluations require continuous numerical processing, including exponential functions and linear weighting. To address this issue, this study decoupled semantic reasoning from numerical computation by developing a coordinated integration framework between the ontology and external computational modules (as illustrated in Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Formula & external computation integration mechanism.

Within this framework, the ontology, serialized in Turtle (.ttl) format, was responsible for providing structured representations of standard clauses, indicator definitions, and parameter dependencies. Simultaneously, external Python programs utilized RDFLib (version 7.5.0) to access the ontology files, perform the necessary mathematical calculations, and write the results back into the ontology. This architecture established a closed-loop system encompassing data acquisition, indicator computation, and condition evaluation.

As shown in Figure 7, the interaction between the ontology and external scripts followed a snapshot-based execution process. Each Python program read a complete ontology snapshot in TTL format as input (e.g., RPMO.ttl), extracted the required semantic parameters, performed the corresponding numerical computation, and serialized the results into a new ontology snapshot (e.g., RPMO_with_DR.ttl). The generated ontology file preserved the full content of the input ontology while appending new data property assertions for the computed values, leaving the original file unaltered. Consequently, each ontology snapshot therefore represented a well-defined and consistent ontology version corresponding to a specific computation stage, and served as an explicit reference point for subsequent reasoning or decision-making.

All numerical inputs required for computation were supplied by the ontology through semantic inference. Distress attributes, including type, severity, converted area, and weighting, were automatically inferred via ontology axioms and SWRL rules (e.g., assigning values to hasWeight and hasConvertedArea). Furthermore, structural parameters required for the DR, PCI, PQI, and MQI formulas, such as A0_PCI, A1_PCI, and specific weighting factors, were encoded as data properties for each Segment individual according to technical specifications.

To ensure unambiguous entity identification throughout the execution process, ontology entities were accessed via their IRIs following a consistent convention. Concepts newly defined in the RPMO used the rpmo: namespace, while reused concepts retained their original IRIs (e.g., RSO:Segment). Algorithm 1 illustrates the DR computation procedure as an example, and the full set of executable scripts for indicator computation and write-back is provided in the Supplementary Materials as Code S3 to S6 (calculate_dr.py, calculate_pci.py, calculate_pqi.py, and calculate_mqi.py). These scripts retrieve relevant Segment and Distress instances, extract numerical parameters, and write the computed indicators back as data property assertions.

Once the ontology was updated with these newly calculated numerical values, subsequent layers of semantic reasoning could be activated. For instance, the system could determine the technical rating of a segment based on MQI thresholds or automatically identify maintenance treatments. Through this iterative interaction, internal semantic reasoning and external numerical computation formed a stable, mutually reinforcing cycle that ensured both logical rigor and computational efficiency.

| Algorithm 1: calculate_dr |

| Input: seg_id; //The internationalized resource identifiers (IRI) of assessed segment Output: DR; //The distress ratio of assessed segment //Step 1. Read the road segment and distress data from ontology 1: segment ← get_individual_by_id(seg_id); //Locate the segment individual 2: A_seg ← get_data_property(segment, “hasConvertedArea”); //Read the converted area of this segment 3: distress_list ← get_object_properties(segment, “hasDistress”); //Obtain all distress individuals observed on this segment 4: if distress_list is empty then 5: DR ← 0.0 6: goto WRITE_BACK_RESULT 7: end if //Step 2. Accumulate the weighted distress area 8: sum_weighted_area ← 0.0 9: for each d in distress_list do 10: w_d ← get_data_property(d, “hasWeight”); //Weight inferred from SWRL rules 11: A_d ← get_data_property(d, “hasConvertedArea”); //Converted area of the distress 12: sum_weighted_area ← sum_weighted_area + (w_d * A_d) 13: end for //Step 3. Calculate distress ratio DR 14: DR_raw ← sum_weighted_area/A_seg 15: DR ← DR_raw * 100.0 //Step 4. Write the DR result back to the ontology WRITE_BACK_RESULT: 16: set_data_property(segment, “hasDR”, DR); 17: save_ontology_changes() 18: return DR |

4.6. Rules & Reasoning Mechanism

While the semantic representation of concepts and numerical computation provided the foundation for assessment, the reasoning mechanism served as the key component that transforms static knowledge into dynamic conclusions. Within the RPMO framework, a comprehensive rule system was developed to automate distress interpretation, parameter inference, technical condition assessment, and maintenance selection. The complete SWRL rule inventory is provided in Supplementary Materials Table S1 SWRL Rules, which lists each rule identifier, rule type, rule content, and textual description. By integrating OWL description logic with SWRL rule-based reasoning, the system enables an automated pipeline from raw inspection data to final maintenance recommendations. Specifically, OWL reasoning handles class inheritance, consistency checking, and automatic deduction based on object property constraints, ensuring that foundational semantic relations are correctly interpreted. SWRL rules complement this capability by establishing executable logical mappings between specification thresholds and the semantic structures defined in the ontology.

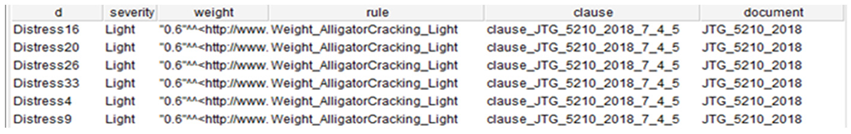

For assessment-related inference, the rule system was organized into four principal categories. The first was severity inference, which determined the severity of a distress instance, such as Light, Moderate, or Severe, based on observed characteristics. These rules aligned directly with the severity thresholds in standards and allowed the Pellet reasoner to automatically assign the hasDistressSeverity property to each Distress individual. The second category, weight determination, assigned specific evaluation weights (e.g., a weight of 0.6 for light longitudinal cracking) based on distress types and severity levels. The third category was area conversion, which unified different measurement units, such as length, into standardized converted areas for DR computation. The fourth category was performance rating, which evaluated the technical condition level of a segment based on indicators calculated in Section 4.5. An example of the severity inference rules can be found in Figure 6.

For maintenance decision-making, two classes of rules were defined: maintenance type selection and maintenance technique recommendation. The type selection rules inferred the appropriate maintenance category for a segment, such as preventive maintenance engineering or rehabilitative maintenance engineering, based on its corresponding indicators. Building on this, the technique recommendation rules further identified specific techniques suited to the segment’s condition, such as MicroSurfacing, FogSeal, or OverlayRecycling.

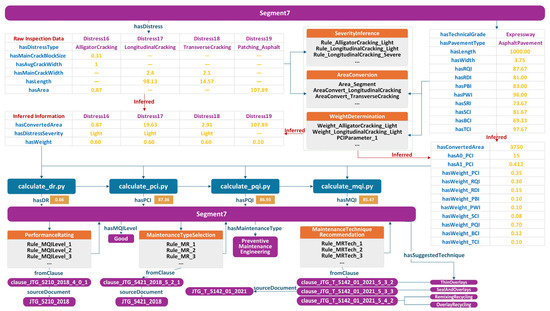

Overall, the rule system supported a fully automated workflow spanning distress characterization, condition evaluation, and strategy selection. As illustrated by the pipeline for Segment7 in Figure 8, this workflow interpreted raw observations and geometric parameters into inferred severities, areas, and weights, which then served as inputs for external numerical computation. These computed results were then written back to the ontology to trigger further inference regarding performance levels and maintenance strategies. Each inference result was traceable to its governing specification clause, evaluation rationale, and supporting factual data. It should be noted that the development of this rule system focused on asphalt pavements in expressway contexts as a representative case. The semantic framework allowed further extension to other structural pavement types, more complex maintenance strategies, and multi-criteria decision-making.

Figure 8.

End-to-End reasoning and computation pipeline for Segment7.

4.7. Instantiation & Verification

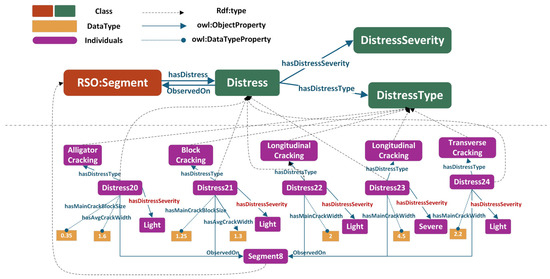

To evaluate the executability and effectiveness of RPMO in practical application contexts, the ontology was instantiated and validated through reasoning using real road inspection data. The instantiation process followed a structured workflow that included data import, semantic individual generation, and rule execution. Using the Cellfie plugin embedded in Protégé, the raw inspection data in Excel format were mapped to ontology instances of classes such as Segment, Distress, and QualityIndicator, with their corresponding property values populated to provide the foundational facts required for subsequent reasoning. Figure 9 illustrates the instantiation process for the distress data associated with Segment8.

Figure 9.

Instantiation process for the distress data associated with Segment8.

Once the instantiated data were loaded, the ontology was subjected to both description logic reasoning and SWRL rule-based reasoning to validate its performance in distress severity inference, parameter determination, indicator computation, and maintenance decision-making. This process ensured that the ontology behaved correctly under realistic conditions and satisfied the requirements of logical soundness, internal consistency, and traceability of inference outcomes.

To comprehensively examine the ontology’s performance across different application tasks, this study designed three use case scenarios grounded in typical operational workflows. These scenarios covered the essential steps from data interpretation to decision generation and constituted a systematic evaluation of the ontology’s overall capabilities. The input datasets, rule representations, reasoning logic, and corresponding CQ based SPARQL validation for these scenarios are presented in detail in Section 5.

5. Use Case Scenarios

To validate the applicability of the developed RPMO and its reasoning mechanisms to real road condition data, this section constructed three representative use case scenarios based on field-collected inspection records. These scenarios were designed to systematically validate the ontology’s reasoning workflows across three core tasks: distress severity inference, technical condition assessment, and maintenance decision support.

Each use case included the instantiation of input data, the execution of relevant rules, and the verification of inference outcomes. SPARQL-based CQs were employed to examine the correctness and internal consistency of the ontology’s reasoning results. For brevity, common prefix declarations were omitted in the SPARQL queries reported in the tables for each subsequent scenario. These included the standard namespaces (PREFIX rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#>, PREFIX owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#>, PREFIX rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#>, and PREFIX xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#>) as well as the domain-specific prefixes RSO (<http://www.semanticweb.org/MarquetteUniversity/Road_Shared_Ontology#>) and rpmo (<http://www.semanticweb.org/RPMO#>). All input data were batch-imported from Excel spreadsheets into the ontology using defined rules in the Cellfie plugin of protégé, ensuring full reproducibility of the evaluation process. Moreover, across all three scenarios, ontology-based outputs were further compared against the independently derived, standards-based ground truth described in Section 3.2.6. Detailed descriptions of the input datasets and the load rules are provided in the Supplementary Materials Table S2 input data and Code S1 Cellfie load rules, respectively.

5.1. Use Case Scenario 1: Distress Severity Inference

5.1.1. Input Data and Instantiation

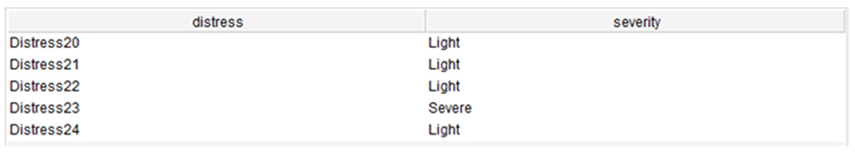

This scenario illustrated how RPMO integrated distress parameter attributes with SWRL-based reasoning to automatically classify asphalt pavement distresses’ severity levels. Five distress records observed on Segment8 (Distress20 to Distress24) were used as representative examples. As illustrated in Figure 9, the records in Excel were converted into ontology individuals through data mapping. During this process, essential properties including hasDistressType, hasMainCrackBlockSize, hasAvgCrackWidth, and hasMainCrackWidth were automatically generated. For example, Distress22 and Distress23 were longitudinal cracks with measured hasMainCrackWidth of 2 mm and 4.5 mm, respectively.

5.1.2. Rule Modeling

According to the Highway Performance Assessment Standards, the severity of a distress can be determined based on its associated parameters and the corresponding normative criteria. In this section, the standard-based severity criteria were formalized into executable rules so that raw distress observations could be consistently transformed into machine-interpretable severity labels, which then served as inputs to subsequent indicator computation and decision reasoning. Taking longitudinal cracking as an example, the severity of a longitudinal crack was considered light if the main crack width was less than or equal to 3 mm, and severe if the main crack width exceeded 3 mm. These normative thresholds were modeled in the ontology as individuals of the StandardClause class and were linked to the corresponding distress severity inference SWRL rules (Detailed SWRL rules and their textual descriptions are provided in Supplementary Materials Table S1 SWRL Rules):

Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Light: Distress(?d) ^ hasDistressType(?d, LongitudinalCracking) ^ hasMainCrackWidth(?d, ?v) ^ swrlb:lessThanOrEqual(?v, 3) -> hasDistressSeverity(?d, rpmo:Light) ^ evidencedBy(?d, Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Light)

Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Severe: Distress(?d) ^ hasDistressType(?d, LongitudinalCracking)^ hasMainCrackWidth(?d, ?v) ^ swrlb:greaterThan(?v, 3) -> hasDistressSeverity(?d, Severe) ^ evidencedBy(?d, Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Severe)

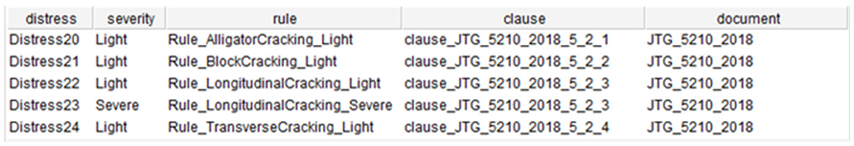

Following the clause-tracing mechanism described in Section 4.4, each SWRL rule instance was linked to a specific clause of the governing standard through the fromClause property. For example, the rule Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Light was derived from clause_JTG_5210_2018_5_2_3, which was captured in the ontology as:

fromClause(Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Light, clause_JTG_5210_2018_5_2_3)

In this representation, clause_JTG_5210_2018_5_2_3 was modeled as an instance of StandardClause class, which was connected to the standard document instance JTG_5210_2018 via the sourceDocument property and carried the clauseID 5.2.3 as a datatype attribute:

sourceDocument(clause_JTG_5210_2018_5_2_3, JTG_5210_2018) and clauseID: 5.2.3.

5.1.3. Reasoning

After the distress instances were loaded, the defined SWRL rules were executed in the Protégé environment through the SWRLTab plugin. The Pellet reasoner automatically inferred the hasDistressSeverity property (illustrated by the red solid arrows in Figure 9) and asserted the evidencedBy relation to the corresponding rule instance.

For Distress22, with a main crack width of 2 mm, the reasoner evaluated the rule Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Light for longitudinal cracking and inferred:

hasDistressSeverity(Distress22, Light)

evidencedBy(Distress22, Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Light)

fromClause(Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Light, clause_JTG_5210_2018_5_2_3)

sourceDocument(clause_JTG_5210_2018_5_2_3, JTG_5210_2018)

5.1.4. SPARQL Queries for CQ1 and CQ2

Table 4 presents the SPARQL queries for CQ1 and CQ2 together with their corresponding outputs in RPMO. Using Segment8 as an example, CQ1 retrieved the inferred severity levels for the observed distresses. The results indicated that four of the five cases were classified as Light, whereas Distress23 was identified as Severe. CQ2 further traced the standard clauses that support these severity inferences. The retrieved results showed that Distress20, categorized as AlligatorCracking, was evaluated according to clause 5.2.1 of JTG_5210_2018; Distress21, a BlockCracking case, was governed by clause 5.2.2; Distress22 and Distress23, both LongitudinalCracking, followed clause 5.2.3; and Distress24, a TransverseCracking, followed clause 5.2.4 of the same standard.

Table 4.

SPARQL queries and results for CQ1 & CQ2.

These results demonstrate that the RPMO, through a unified rule pattern and parameter definitions, achieved automated severity assessment across multiple distress types. The inferred severity values fully aligned with ground truth obtained through a verification panel, confirming both correctness and interpretability of the reasoning process.

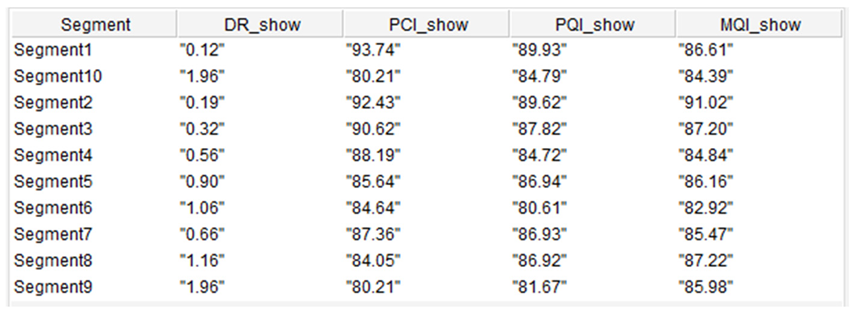

5.2. Use Case Scenario 2: Technical Condition Computation & Performance Level Rating

This scenario evaluated the executability and semantic consistency of an ontology-driven, cross-module computation workflow involving semantic reasoning, external numerical computation, data write-back, and automated condition rating. Taking a complete road section as the assessment object, the workflow demonstrated how inferred distress parameters (such as distress-specific weights and converted areas) were first obtained through ontology reasoning. These results were then consumed by external Python scripts to compute the DR, PCI, PQI, and MQI indicators sequentially. The computed values were written back into the ontology, after which the performance rating SWRL rules classified the segment’s technical condition (e.g., Excellent, Good, Fair) based on its MQI value and generated the corresponding semantic assertions.

5.2.1. Instantiation of Road Segments and Distress Data

Scenario 1 presented the distress parameters detected on Segment8, whereas this scenario extended the analysis to eleven segments (Segment1 to Segment10) to demonstrate a complete executable assessment and decision workflow. Detailed data for all segments are provided in the Supplementary Materials Table S2 input data. The basic information of the representative road section Segment7 (e.g., technical grade “Expressway” and pavement type “AsphaltPavement”), the observed distresses and their associated attributes (Distress16 to Distress19), and the corresponding technical indicator values (e.g., hasRDI, hasRQI) are presented in detail in Figure 8. It should be noted that this scenario focused exclusively on the computational workflow for the asphalt pavement indicators DR, PCI, PQI, and MQI. Other technical condition indicators (e.g., RQI and RDI) were introduced as placeholder inputs at this stage. These values were instantiated only to enable the execution of indicator aggregation and reasoning rules, while their detailed computational logic was treated as an extensible component that requires further ontology and computation-module expansion. Accordingly, representative values for these indicators were manually assigned within plausible ranges by referencing comparable inspection results.

In addition, the parameter and weight values required for formula-based computations, as well as the converted areas of segments and certain distress types, were automatically inferred through the severity inference, weight determination and area conversion rules defined in Section 4.6. These rules, implemented via the ontology’s reasoning mechanism, inferred and generated the necessary inputs prior to indicator calculation.

For example, as shown in Figure 8, the rules Rule_LongitudinalCracking_Light and Weight_LongitudinalCracking_Light inferred that Distress17 had a Light severity and the corresponding computation weight of 0.6. The area conversion rule AreaConvert_LongitudinalCracking further converted the recorded linear length of the distress into an equivalent area value of 19.63. Similarly, the segment area was computed using the Area_Segment rule. These inferred weights and converted areas were then used as direct inputs for DR computation. Moreover, the rule PCIParameter_1 derived the segment-specific parameters A0_PCI and A1_PCI for Segment7 based on its technical grade and pavement type, enabling subsequent PCI computation. The same reasoning mechanism also inferred aggregation weights such as hasWeight_PCI, hasWeight_RQI, and hasWeight_RDI for PQI computation, and hasWeight_PQI, hasWeight_BCI, hasWeight_SCI, and hasWeight_TCI for MQI computation.

5.2.2. Modeling DR, PCI, PQI and MQI

According to the Highway Performance Assessment Standards [12], the DR was computed from distress areas and weights over segment area, as defined in Equation (1). PCI was computed as a function of DR, as defined in Equation (2).

where and are computational parameters corresponding to the A0_PCI and A1_PCI values in the ontology; is the converted area of the i-th type of distress; is the total inspected area of the segment; is the weight for the i-th type of distress; represents the distress type including its severity level; and is the total number of distress types (21 for asphalt pavement and 20 for cement concrete pavement).

The PQI was defined as a composite measure incorporating PCI, RQI, RDI, and either the SRI or the PWI, with weights specified by road technical grade, as shown in Equation (3). Similarly, the overall highway condition index MQI was formulated as a weighted combination of SCI, PQI, BCI, and TCI, as defined in Equation (4).