Abstract

Grain oriented electrical steel is the most common core material used in power and distribution transformers. Compressive mechanical stress has a detrimental effect on the magnetic properties of the steel; thus, it is important to develop techniques and models that might be useful for the designers of magnetic circuits in non-rotating electrical machines. The present paper proposes an approach to address this issue. The approach is related to previous research by Garikepati et al., yet it uses more easily accessible measurement data (coercive field strength). The phenomenological T(x) model is used as part of the computational chain. The results might interest engineers working on the nondestructive testing of soft magnetic materials.

1. Introduction

Grain-oriented (GO) electrical steel is an important segment of the soft magnetic market [1,2]. This material is used as the core material in power and distribution transformers. For this application, low loss density and high permeability are the crucial parameters, since transformers are electrical devices designed for continuous work for at least thirty years. It is estimated that around 5% of total electric energy produced worldwide is converted into heat during the operation of transformers. A better understanding of the phenomena governing the magnetization process may thus be helpful in the design process of the magnetic circuits leading to the optimization of energy losses during re-magnetization.

Contemporary GO electrical steels are classified into two groups: conventional grain-oriented (CGO) and high grain-oriented (HGO) steels. HGO steels feature improved texture, and the average dispersion of grain directions from the rolling direction does not exceed 4 degrees, which results in better catalogue parameters: higher value (even reaching 1.95 T) of flux density at field strength 10 kA/m and lower power loss densities in comparison to CGO steels.

Goss technology, used commonly for the production of conventional 3.2% Si wt. sheets, allows one to produce sheets that feature a specific loss density equal to 0.75 W/kg at Jm = 1.9 T, f = 50 Hz. For Hi-B oriented sheets, at the same polarization and frequency, the value of specific loss density may attain 0.6 W/kg [3].

A More Detailed Information on HGO Steels

The processing technology for steel sheets with improved texture was developed about 50 years ago in Japan, in the specialist literature they were referred to as Hi-B sheets. In general, this technology made it possible:

- -

- to increase the sheet homogeneity by removing harmful impurities, mainly non-metallic inclusions, which hinder the movement of domain walls during the magnetization process,

- -

- to improve the degree of sheet texturing, which resulted in an increase of maximal working flux densities,

- -

- to optimize the effect of mechanical stresses on the domain structure due to the application of surface insulating layers. Apart from limiting interlayer eddy currents within the core, the insulating layer introduces tensile stresses into the sheet, which promotes the onset of uniaxial anisotropy in the sheet aligned with the direction of the easy magnetization axis, which is created as the result of the rolling process.

The production process of grain-oriented steel sheets is more complicated than for non-grain-oriented steels used in rotating machines. The aim of the technological process is to obtain grains with (110)[001] orientation after secondary recrystallization. The basic stages of GO sheet production are presented below [4]:

- -

- Remelting of the master alloy with a silicon content of 2.9–3.2 wt. %; vacuum degassing; adding selected ladle admixtures, e.g., Al, Mn, Sb, S, and N (the percentage concentration of admixtures does not exceed several hundred ppm), and continuous casting;

- -

- Repeated heat treatment at a temperature of 1250–1350 °C, followed by the hot rolling of the slabs to a thickness of approximately 2 mm; annealing at a temperature of 900–1000 °C; and sudden cooling. Admixtures in the form of precipitates that are formed at the end of the previous stage dissolve after repeated heat treatment and precipitate again during hot rolling and annealing. At this stage, special care should be taken to select the appropriate temperatures and melt processing time intervals because the size of the admixtures formed at this stage is crucial for the recrystallization process;

- -

- Cold rolling carried out in two stages (~70% and ~55%) to the final sheet thickness (0.23–0.35 mm), interwoven with annealing treatment at 800 °C and 1000 °C. A large amount of deformation accumulates in this stage, which promotes complete recrystallization in the next annealing stage;

- -

- Decarburizing annealing in the atmosphere of liquid hydrogen at the temperature of 800–850 °C. During this process, the percentage of carbon is limited to less than 50 ppm. At this stage, complete primary recrystallization takes place. Due to the presence of MnS, AlN, etc., admixtures in the alloy, the development of newly formed grains is difficult. Their average size is 15–20 μm;

- -

- Covering with a layer of MnO and slow annealing of the sheets under closed conditions for many hours at a temperature of 1200 °C to reduce oxidation (box annealing), followed by cooling. During this stage, exceptionally large and highly oriented grains (110)[001] are formed within the primary matrix, and at the end they cover the entire volume of the sheet. This process is interpreted in such a way that the (110)[001] grains show much higher boundary mobility compared to most primary grains, which are dominated by {111} and {111} textures. It is estimated that only one grain out of 106 of the primary grains shows the (110)[001] orientation, which explains the large size of the final grains after secondary recrystallization. At the end of closed annealing, the inclusions are completely dissolved, thus avoiding their harmful effect on the re-magnetization process.

- -

- Covering with a phosphate layer and final thermal leveling treatment (thermal flattening). The equalizing treatment is carried out in a continuous furnace, where it is possible to control the belt tension. As the tape cools, the insulation hardens before the substrate, and due to the difference between the thermal expansion coefficients, a preferably low level of stress is generated in the lamination (the change in loss after repeated annealing does not exceed 5%).

HGO sheets are produced by one-stage cold rolling using AlN as an inhibitor for secondary recrystallization; the thickness reduction during rolling exceeds 85%. It is essential for the production process to ensure the existence of AlN in the form of a finely dispersed phase separated at every stage of the metallurgical process, from remelting the initial alloy to annealing after hot rolling. It is crucial to maintain a certain volume level of the austenite phase to allow the AlN to dissolve during the soak phase and to precipitate a large number of fine AlN particles during the cooling step during the soak phase after hot rolling. The consequence of this is that the carbon content and temperature level during hot rolling finishing are important in the Hi-B sheet production process.

Apart from the Hi-B technology developed by Nippon Steel, other sheet production technologies with improved properties were developed in later years, among others by Kawasaki Steel (RG-H sheets), Allegheny Ludlum and ARMCO.

Not only the secondary recrystallization phase formation has a significant impact on the final properties of the ready-made sheet. Another important process that affects them to a large extent is the covering of sheet surface with an oxide insulating layer. The influence of stresses introduced by insulating coverings on the magnetic properties of sheet metal has been the subject of intensive research, e.g., [5]. It should be stated that the key problem that limits GO sheets from achieving minimum losses is the presence of internal stresses in the material [6]. The source of internal stresses is admixture, the process of cold rolling and covering the surface of the sheets with an insulating layer, which induces residual stresses and deformations. For example, the use of a phosphate coating results in internal stresses of 1.2 MPa in the rolling direction, which causes problems such as increased loss and magnetostriction. The purpose of laser surface treatment is to reduce unfavorable internal stresses and introduce favorable stresses that will affect the fragmentation of magnetic domains in the material. If the stress is tensile, it can reduce the loss of the sheet. In turn, if the stress is compressive, it tends to increase the specific loss density of the material.

Magnetic properties of the material deteriorate as a result of subsequent technological operations of core production [7,8]. During the final core assembly, stresses arise due to impacts, bending, and compression during transportation and storage, as well as inevitable deformations of the structure during cutting, punching, and compression during packaging. Other operations, such as inserting slot insulation, winding, or impregnation, do not have a harmful effect on the final magnetic properties of the core. Punching operations, packaging methods, and technical culture during the magnetic circuit manufacturing process may have an effect on the magnetic properties of the finished magnetic core; therefore, it is necessary to take into account information on the impact of technological operations during the core production process at the design stage of the electric machine.

From the brief review of processing technology for HGO steels provided in this section, a general conclusion may be drawn: mechanical stresses, which are inevitably introduced in subsequent stages of sheet production and the subsequent core assembly process, have a significant impact on the magnetic properties of the material, what implies the necessity to carry out research on this effect.

Aside from technological aspects related to the production of electrical steel sheets, it should be stated that the influence of mechanical stress on magnetic properties is of great interest to engineers and theoretical scientists alike [9]. Exemplary practical applications of the phenomenon are energy harvesting [10,11] and the development of precise sensors and transducers [12,13].

2. Outline of the Proposed Concept

Hysteresis loops of soft magnetic materials subject to mechanical stress change their shape. The present paper is focused on modeling the effect of applied stress in samples of Hi-B GO steels produced by the Polish enterprise Stalprodukt S.A., Bochnia, Poland. The approach advanced by Garikepati et al. [14] and subsequently scrutinized in [15,16] is applied. The essential idea of the approach consists in the fact that the slopes of anhysteretic susceptibilities for the samples subject to mechanical stress and the stress-free one differ. The reciprocals of the slopes of anhysteretic susceptibilities at zero field should be proportional to the magnitude of the applied (or residual) stress, which can be written as

The anhysteretic curves are understood as the middle curves of the corresponding hysteresis loops, following the suggestions of Bozorth [17] and Krah and Bergqvist [18]. The successive values of anhysteretic field strength are obtained from averaging the corresponding field strength values measured at the ascending and the descending loop branches for the same values of flux density (or magnetization). It is interesting to remark that for symmetric loops an analytical expression for the anhysteretic curve exists [19]. The analysis of anhysteretic processes leads to the conclusion that one should rather speak of the anhysteretic surface instead of individual curves [20], since these are different for altered magnetization patterns and applied stress values. However, for a fixed magnetization level and varying stress values one can examine the usefulness of dependence (1).

The relationship (1) was derived by Garikepati et al. [14] under the assumption that the magnetostriction coefficient λ was proportional to squared magnetization; this assumption is approximately fulfilled for many magnetic materials [21,22,23]. The authors of [14,15] availed of the analytical relationship for the anhysteretic curve given with the modified Langevin function, which is commonly used in the Jiles–Atherton description [24] in spite of its highly simplified nature and general inability to describe highly distorted magnetization curves under compressive stress. It is remarkable that the same functional relationship was derived in [16] using another phenomenological hysteresis model, the T(x) description. In the present paper, we also work with the latter description; however, our aim is rather to provide clues for practitioners on how to recover useful information from easily measurable data.

In [19] the following relationship for the anhysteretic curve was derived from the law of addition of hyperbolic tangent functions

Differentiation with respect to T(x) yields the derivative

On the other hand

From the chain rule for differentiation ; thus, taking into account that for T(x = 0) = 0, the final expression for d y/d x (differential anhysteretic susceptibility) becomes . Its reciprocal takes a finite value that is dependent only on the value of coercive field strength measured for the major loop at saturation. The same statement is true for the loops subject to mechanical stress; the only difference is that one should take into account the altered value of , which shall be denoted .

Therefore, instead of processing the measurement data in order to recover the shape of the anhysteretic curve, one can use the directly accessible measurement data for coercive field strength at and at some altered state , and the difference should be proportional to stress . The obtained relationship sheds light on the connection between the research on the effect of mechanical stresses, dislocations, etc., on the coercive field value (cf. the theories by Neél [25] or Vicena [26]) and the approach advanced by Garikepati et al. [14]).

3. Materials and Methods

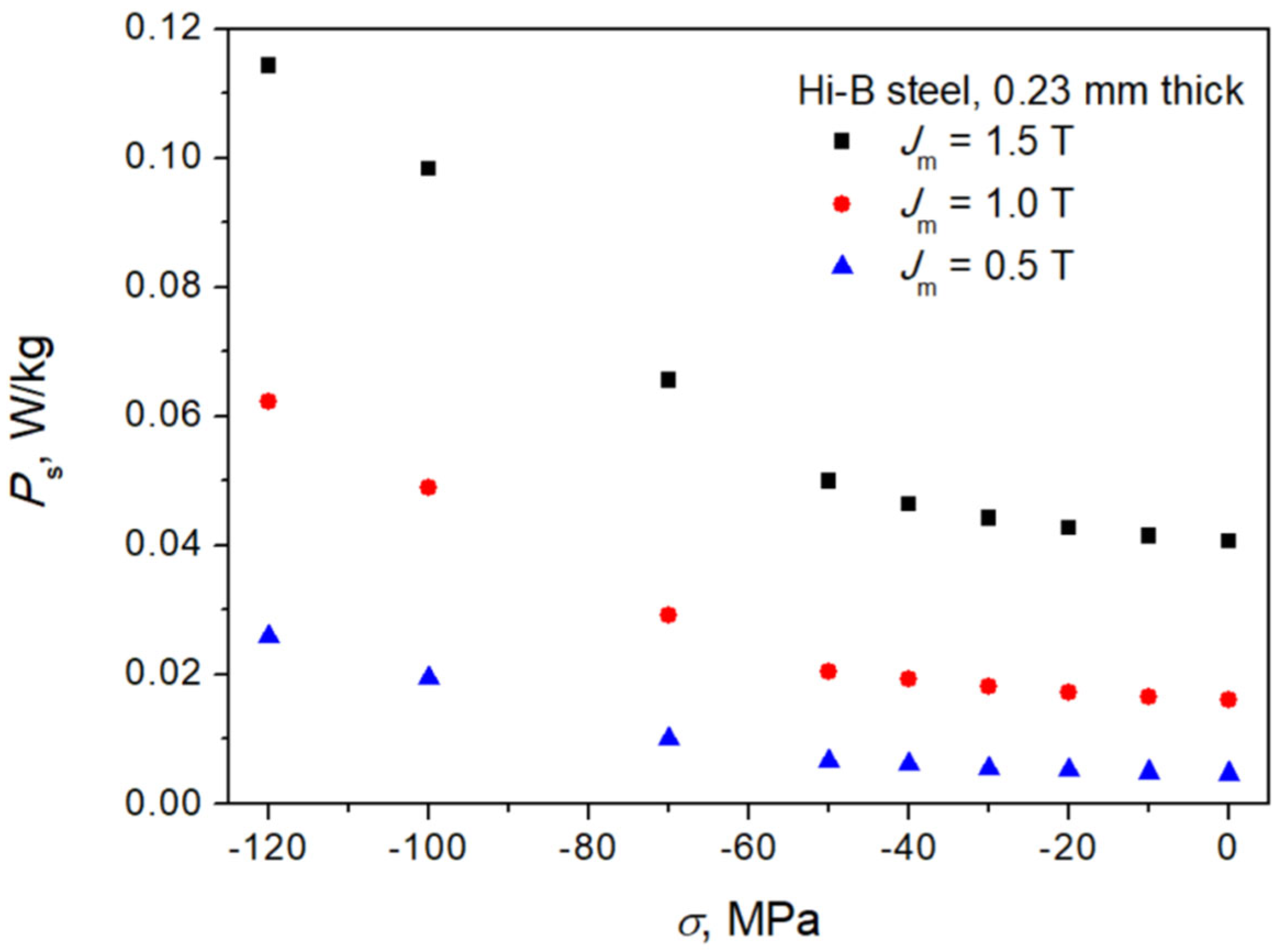

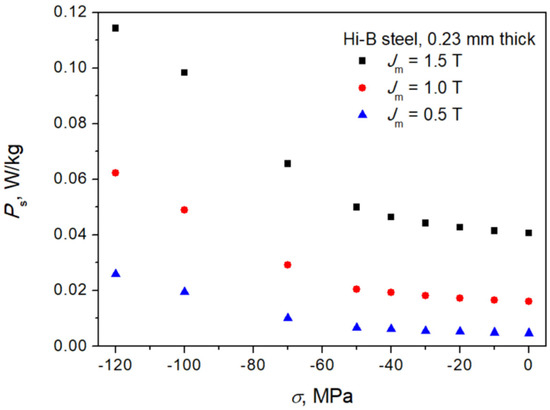

Measurements of hysteresis curves of a HiB GO steel strip 0.23 mm thick from Stalprodukt S.A., Bochnia, Poland were carried out using the Measurement System for the Evaluation of Magnetic Materials under Applied Stress from Dr. Brockhaus Messtechnik GmbH & Co. KG, Lüdenscheid, Germany [27]. The Brockhaus Single Strip Tester (SST) system, shown in Figure 1, makes it possible to carry out measurements of magnetic properties of specimens under applied stress (both tensile and compressive). The strip dimensions are the standard ones, i.e., width: 30 mm; length: 300 mm. Uniaxial load may be applied in the range 0 up to 6500 N (tension) and 1500 N (compression). For the purpose of this paper, we have focused on the J-H curves obtained for different values of compressive stress since the shapes of hysteresis curves are more interesting. Moreover, compression is considered as a harmful effect that can be assessed, e.g., from the measured dependencies’ specific loss density vs. stress depicted in Figure 2. The excitation frequency was set to 5 Hz for the cases depicted in the Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The Brockhaus measurement system at Częstochowa University of Technology. Source: own work.

Figure 2.

Measured Ps = Ps (σ) dependencies. Source: own work.

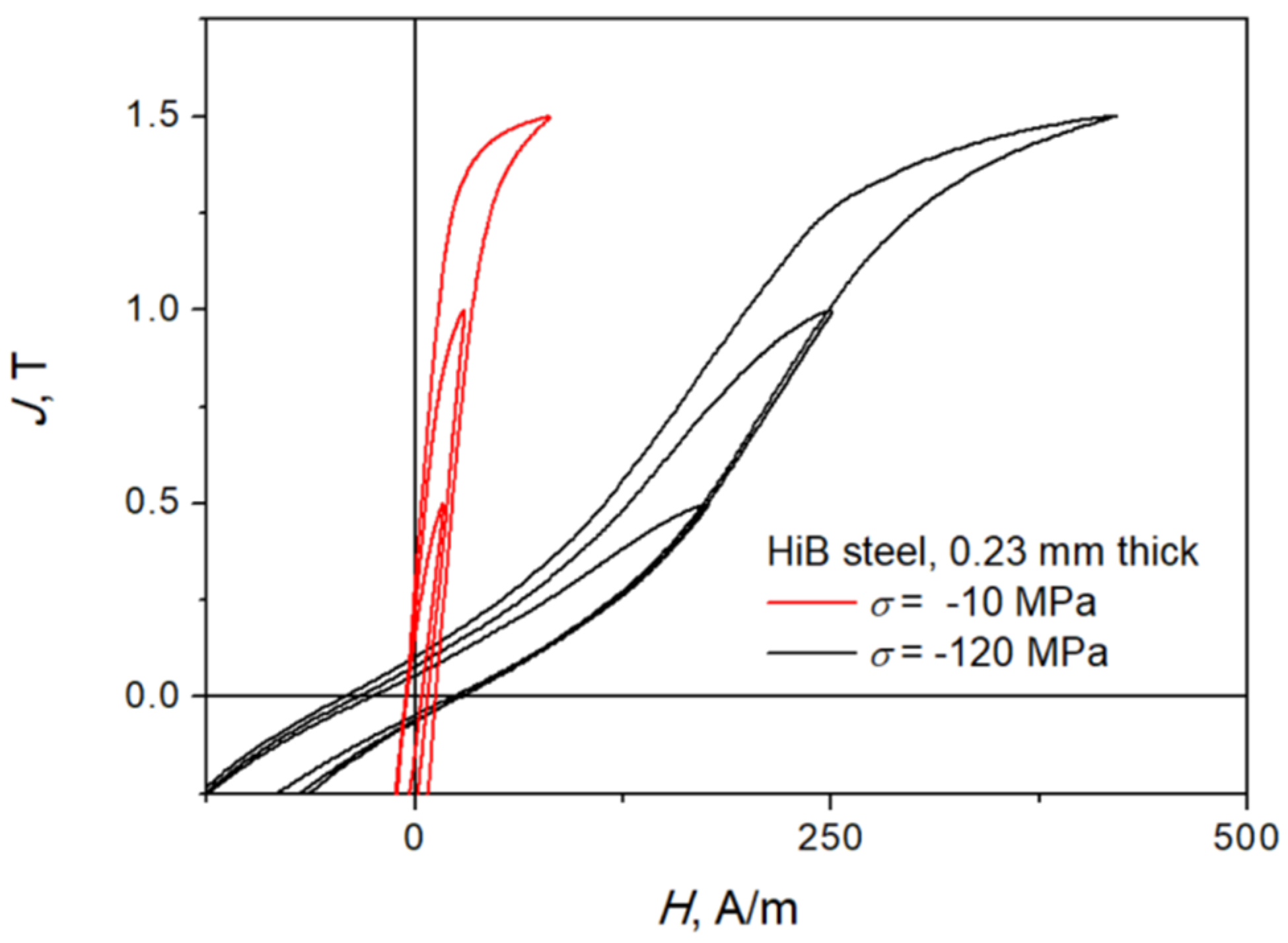

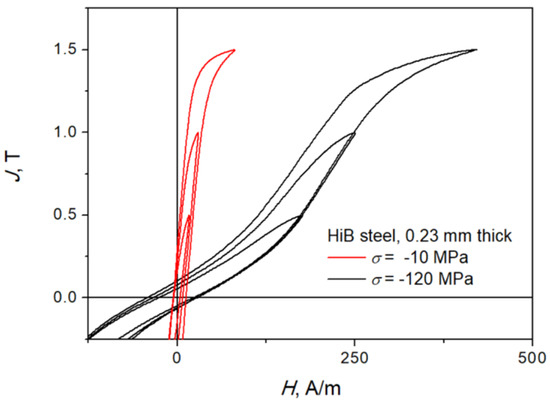

The only assumption made during the derivation of the above-given reasoning is that the hysteresis curves could be described using the model. Of course, for the hysteresis loops subject to compressive stress this assumption is not always fulfilled, which can be inferred from Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Measured hysteresis curves for arbitrary values of applied compressive stress. Source: own work.

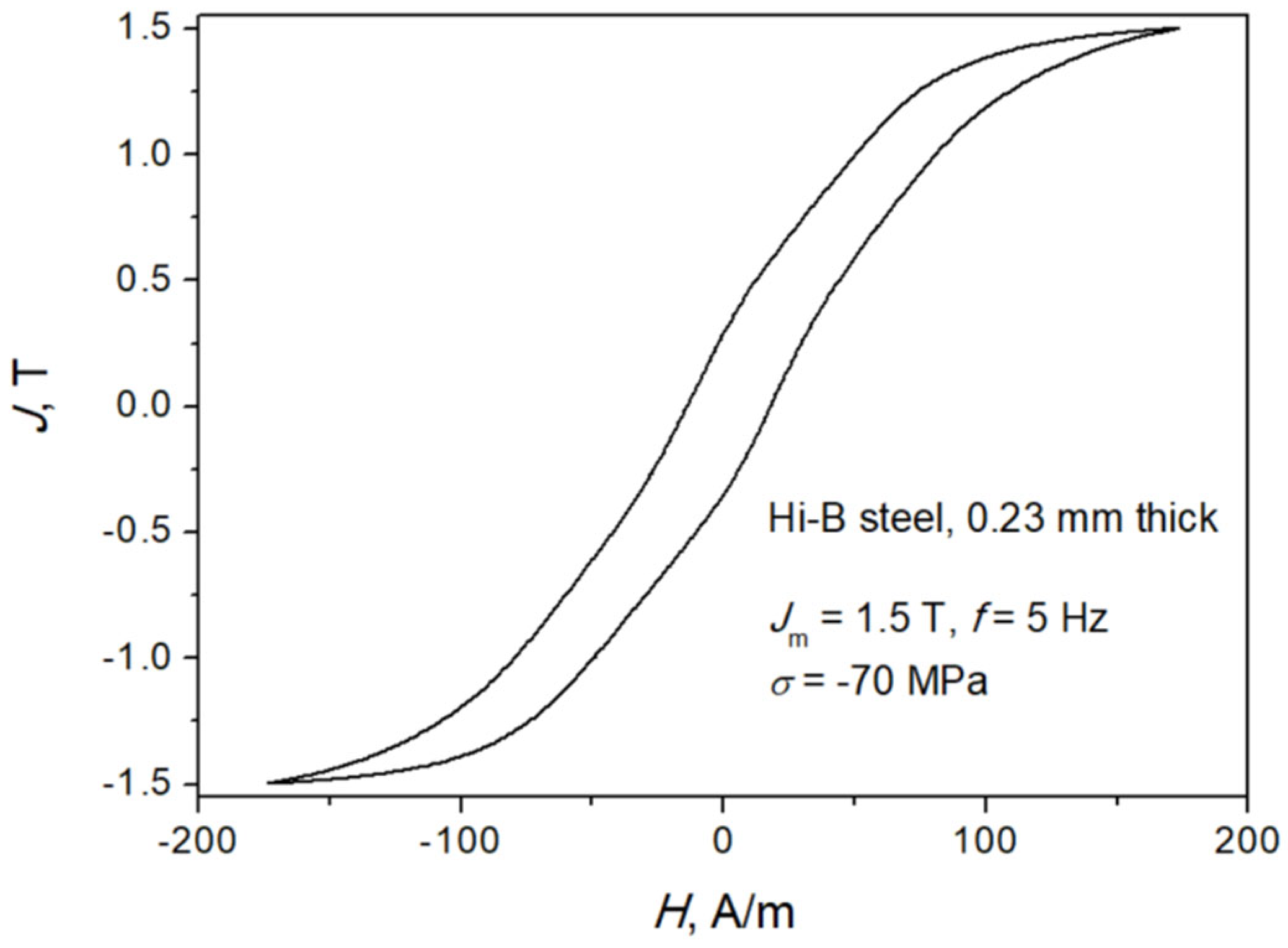

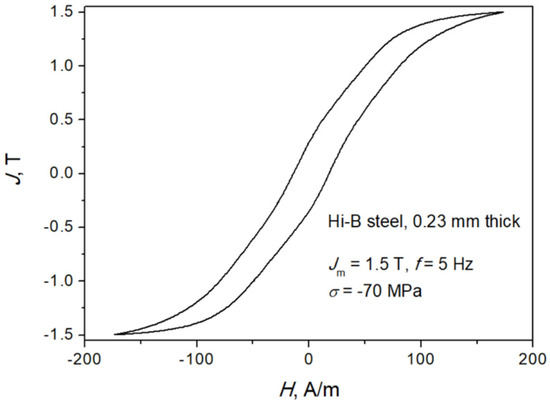

Figure 4.

Measured hysteresis curve for σ = −70 MPa. Source: own work.

Figure 3 depicts exemplary measured hysteresis curves at different arbitrarily chosen values of the compressive stress. The amplitude of polarization was set at 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 T. The shapes of hysteresis curves for lower values of applied compressive stress ( MPa) do not differ much from that for 0 MPa; on the other hand, the distortion of the shape of hysteresis curves at σ = −120 MPa is clearly visible. The excitation frequency was set up to 5 Hz in order to avoid the effect of eddy currents on the loop shape. The value 5 Hz is the lowest admissible value in the system.

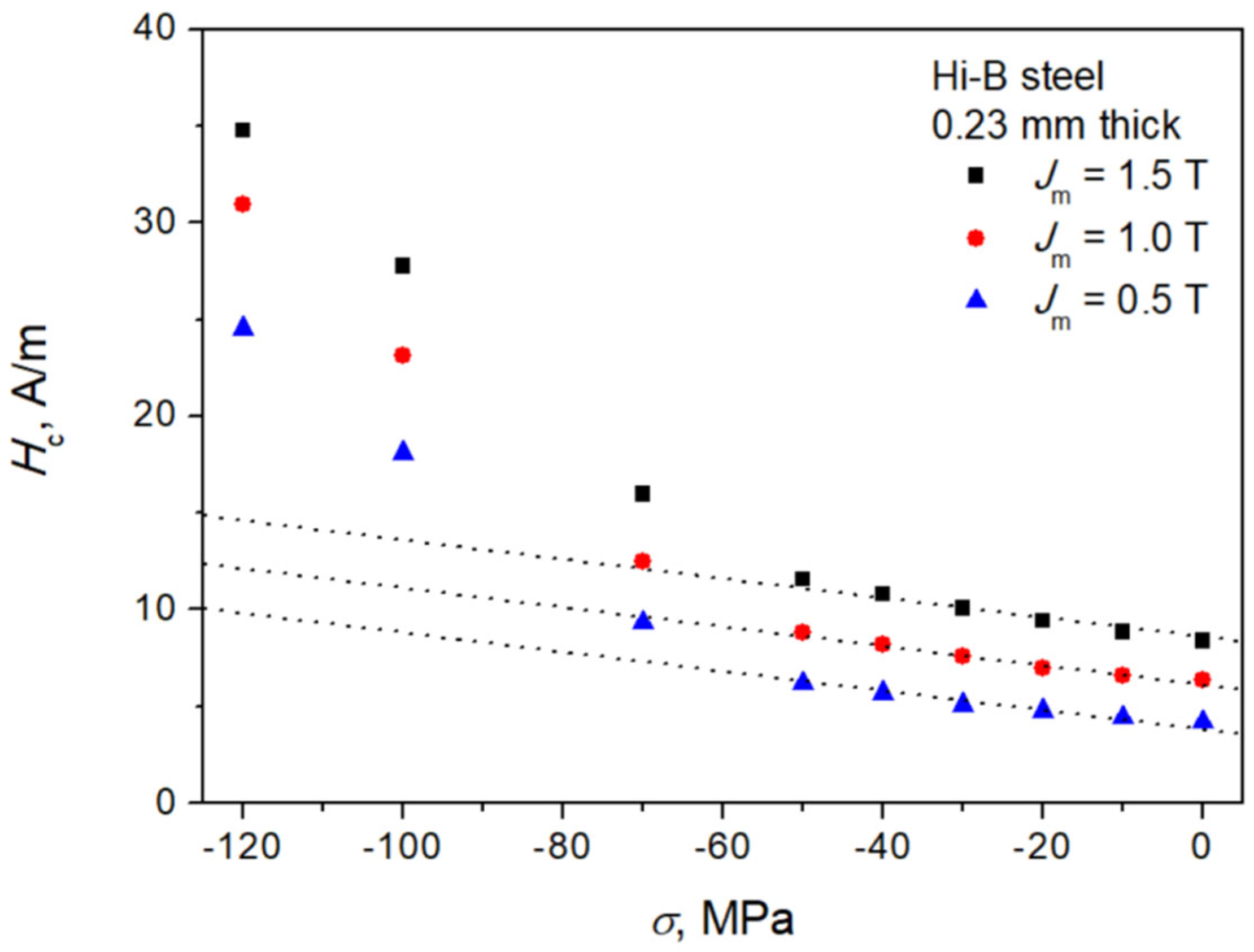

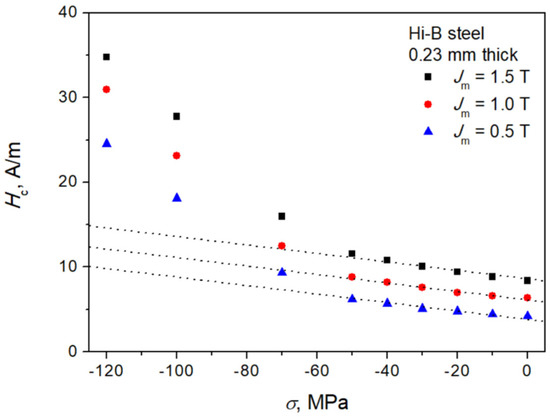

Figure 4 depicts a measured hysteresis loop at Jm = 1.5 T, σ = −70 MPa. For this stress value, the distortion of loop shape in the central part is already noticeable. Figure 5 presents the dependencies of coercive field strengths for minor loops on applied compressive stress at different peak polarization values. Dotted lines depict the trend straight lines with fixed slopes. It can be remarked that the dependencies Hc = Hc (σ) may be considered as approximately linear up to σ = −50 MPa. In reality, the computed value of slope obtained from linear regression varied to some extent in its dependence on the polarization amplitude (the slope was somewhat steeper for higher Jm), and the straight lines shown in Figure 5 correspond actually to Jm = 1.0 T, yet these straight lines are used just to illustrate that the onset of some more complicated magnetization mechanism occurs beyond σ = −50 MPa.

Figure 5.

Measured dependencies of coercive field strength for minor loops vs. applied stress. Source: own work.

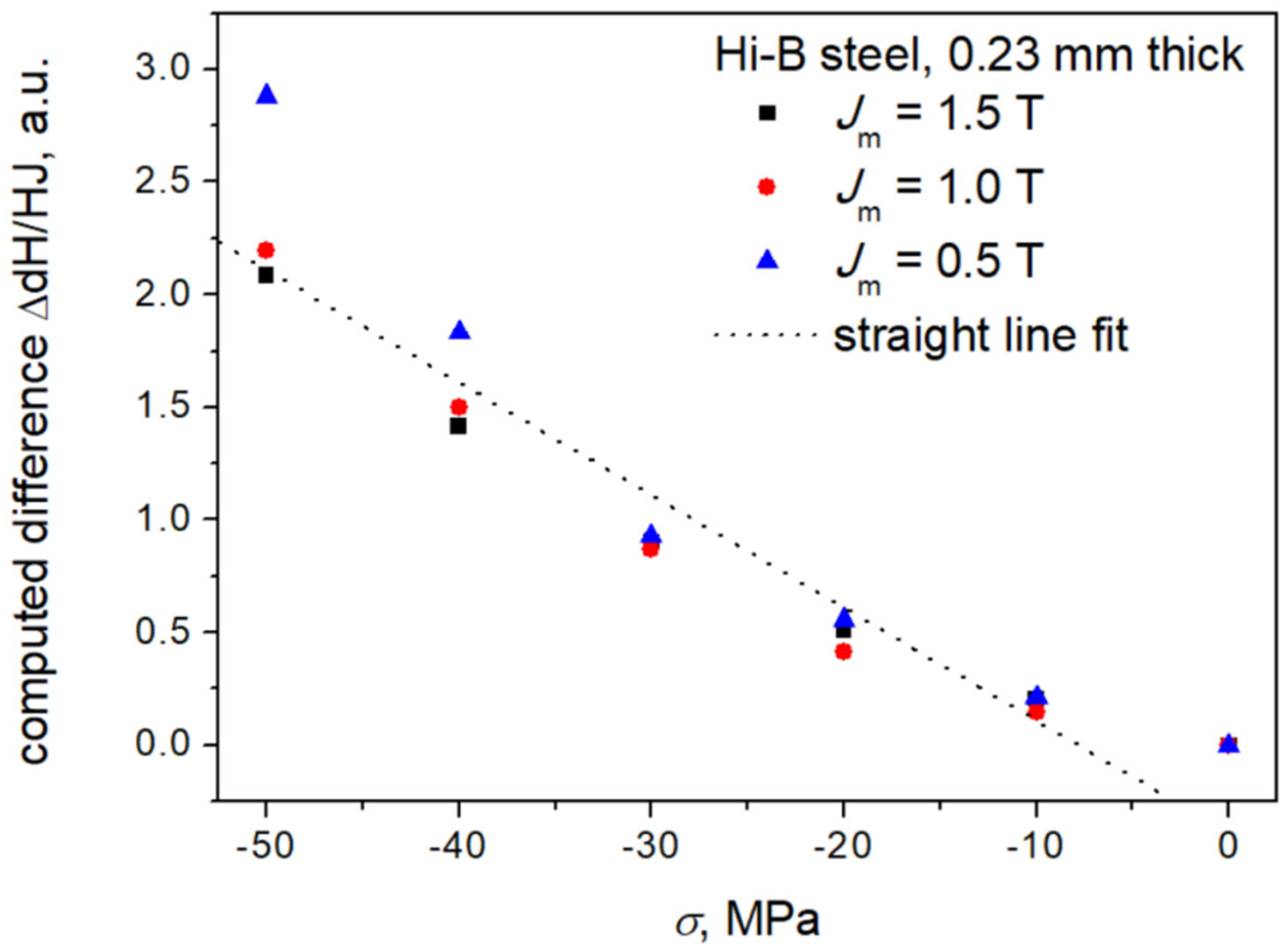

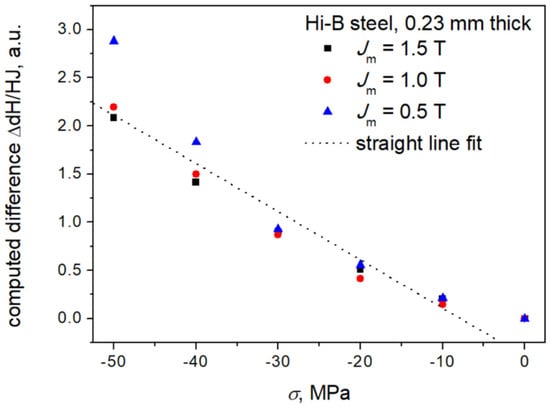

Figure 6 depicts the dependence of the computed value of vs. applied compressive stress for MPa for three polarization values. Since the model operates on dimensionless (relative) units, we are free to choose the normalization constant for coercive field strength (for raw data where e.g., Hc(0) at Jm = 1.5 T is approximately 8.4 A/m; the hyperbolic tangent function would immediately saturate, if we used the normalization constant set to unity). Therefore, we decided to normalize the values of coercive field strengths assuming that for stress-free samples Hc(0) values for minor loops are set to unity for each amplitude. In fact, we should use the values from saturating (major) loops in the computations, but the measurements of major loops under applied stress are somewhat troublesome; moreover, we wanted to check out the validity of the proposed approach for those polarization values, which are uniquely defined and are often used in practice for material characterization.

Figure 6.

Computed difference of reciprocals of anhysteretic susceptibility vs. applied compressive stress. Source: own work.

It can be stated that the results for Jm = 1.5 T and Jm = 1.0 T practically “collapsed”, which indicates that magnetization process is governed by a similar mechanism. There are slight deviations for Jm = 0.5 T noticeable at higher stress values, but generally it can be stated that indeed there exists a linear dependence between the computed difference of reciprocals of anhysteretic susceptibilities and the applied stress, which confirms the validity of the approach by Garikepati et al. [9]. The equation of the straight line fit shown in the Figure is y = −0.05x − 0.39.

4. Conclusions

In the communication, we have indirectly attempted to prove the validity of Garikepati model for the characterization of Hi-B steel under compressive stress. We have availed of the model in order to transform the relationship for the difference of the slopes dHan/dJ, which are somewhat cumbersome to determine experimentally in a more useful relationship, which contains more easily accessible data related to coercive field strengths. In the past a lot of research was devoted to the examination of the effect of stress on the value of coercive field strength for different soft magnetic materials, which revealed that plastic deformation, density of dislocations, etc., had a significant impact on this specific point on the hysteresis loop.

The present paper provides a link between theories that are of interest to practitioners working on the nondestructive testing and characterization of soft magnetic materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and K.C.; methodology, M.N. and K.C.; software, M.G., R.G. and K.K.; validation, M.N. and K.C.; formal analysis, M.N. and R.G.; investigation, M.G. and M.N.; resources, M.G., M.N. and K.C.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C.; writing—review and editing, M.N. and R.G.; visualization, K.C. and K.K.; supervision, K.C.; project administration, K.C.; funding acquisition, M.N. and K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study and will be published in the PhD Thesis of the first author of the paper. Requests to access the samples of datasets should be directed either to Monika Gębara or the supervisor of her thesis, Krzysztof Chwastek.

Acknowledgments

Stalprodukt S.A., Bochnia, Poland is acknowledged for donating free samples of HiB GO steel used in the presented research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Silveyra, J.M.; Ferrara, E.; Huber, D.L.; Monson, T.C. Soft magnetic materials for a sustainable and electrified world. Science 2018, 362, 6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Zhou, B.; Mao, B. State of the art and prospects on the metallurgical design and manufacturing process of grain-oriented electric steels. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2025, 614, 172739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, T.; Fujikura, M.; Ushigami, Y. Recent progress and future trend on grain-oriented silicon steel (invited paper). J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2000, 215–216, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, F.; Bertotti, G.; Appino, C.; Pasquale, M. Soft magnetic materials. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering; Webster, J., Ed.; J. Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.; Littman, M.F. Factors affecting core losses in oriented electrical steels at moderate inductions (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 1985, 57, 4203–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Suga, Y.; Kobayashi, H. Recent developments in grain-oriented silicon steel (invited paper). J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1996, 160, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyński, W. Influence of magnetic circuit production for their magnetic properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2003, 38, 4905–4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Kestens, L. The processing, microstructure, texture, and magnetic properties of electrical steels: A review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2025, 70, 09506608251317143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Arockiarajan, A. Evolution of nonlinear magneto-elastic constitutive laws in ferromagnetic materials: A comprehensive review. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 546, 168821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mech, R.; Wiewiórski, P.; Wachtarczyk, K. Use of magnetomechanical effect for energy harvesting and data transfer. Sensors 2022, 22, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjurström, J.; Rusu, C.; Johansson, C. Combining Magnetostriction with Variable Reluctance for Energy Harvesting at Low Frequency Vibrations. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Yu, J.-X.; Dang, Z.; Zhou, M. Construction and Numerical Realization of a Magnetization Model for a Magnetostrictive Actuator Based on a Free Energy Hysteresis Model. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, Š.; Molnár, J.; Kováč, D.; Guzan, M.; Bereš, M.; Fecko, B.; Vince, T. Analytical and FEM modeling of a magnetoelastic pressductor-type sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 35407–35417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garikepati, P.; Chang, T.T.; Jiles, D.C. Theory of ferromagnetic hysteresis: Evaluation of stress from hysteresis curves. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1988, 24, 2922–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierczak, L.; Jiles, D.C.; Fantoni, G. A new method for evaluation of mechanical stress using the reciprocal amplitude of magnetic Barkhausen noise. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2011, 47, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodzyński, A.; Suliga, M.; Chwastek, K. A modified method for evaluation of stress in drawn wires from magnetic measurements in the Rayleigh region. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Diagnostics in Electrical Engineering (Diagnostika), Pilsen, Czech Republic, 4–7 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorth, R.M. Ferromagnetism; D. Van Nostrand Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1951; p. 476. [Google Scholar]

- Krah, J.; Bergqvist, A. Numerical optimization of a hysteresis model. Phys. B 2004, 343, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwastek, K.R.; Jabłoński, P.; Kusiak, D.; Szczegielniak, T.; Kotlan, V.; Karban, P. The effective field in the T(x) hysteresis model. Energies 2023, 16, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablik, M.J.; Langman, R.A. Approach to the anhysteretic surface. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 79, 6134–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.W. Magnetostriction and magnetomechanical effects. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1955, 18, 184–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablik, M.J.; Jiles, D.C. Coupled magnetoelastic theory of magnetic and magnetostrictive hysteresis. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1993, 29, 2113–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P. One-dimensional magneto-mechanical model for anhysteretic magnetization and magnetostriction in ferromagnetic materials. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 537, 168212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D.C.; Atherton, D.L. Theory of the magnetisation process in ferromagnets and its application to the magnetomechanical effect. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1984, 17, 1265–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neél, L. Foundations of a novel general theory of coercive field (Bases d’une nouvelle théorie générale du champ coercitif—In French). Ann. Univ. Grenoble 1946, 22, 299–343. Available online: https://www.numdam.org/item/AUG_1946__22__299_0/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Vicena, F. On the connection between the coercive force of a ferromagnetic and internal stress (Пo пoвoдy cвязи кoэpц итивнoй cилы φeppoмaгнeтикoв c внyтpeнним нaпpяжeниeм—In Russian). Czech J. Phys. 1954, 4, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus Measurements. Available online: https://www.brockhaus.com/measurements/about-bmt/?lang=en (accessed on 22 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.