1. Introduction

In recent years, the expansion of electric vehicles (EVs) and large-scale energy storage systems (ESS) has accelerated markedly, driven by climate objectives, tightening emissions regulations, and broader sustainability priorities [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Lithium-ion batteries dominate these sectors due to their high energy density, long cycle life, and favorable power capabilities, enabling the rapid integration of electromobility and renewable energy sources [

5,

6,

7]. According to the International Energy Agency, the global EV fleet exceeded 26 million vehicles in 2022 and is projected to surpass 200 million by 2030 [

1,

2]. Demand for stationary storage is also rising sharply as electrical grids rely increasingly on fluctuating renewable energy generation, requiring substantial balancing and reserve capacity [

3,

4,

8].

A central trend in lithium-ion battery development is the continued improvement in energy density and operational lifetime. Over the past two decades, both metrics have increased significantly due to advances in electrode materials, electrolyte formulations, and cell design [

9,

10,

11,

12]. At the same time, research has shifted toward high-capacity cathodes and anodes, as well as solid-state battery concepts that promise higher safety and energy density [

12,

13,

14]. From a broader environmental perspective, lithium-ion batteries support reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by enabling the displacement of internal combustion engines and facilitating more effective use of renewable electricity [

5,

15]. Nevertheless, their full life cycle—including raw material extraction, recycling, and second-life applications—must be considered to ensure sustainable deployment [

6,

15,

16].

Safe and efficient battery operation depends on rigorous enforcement of charge, current, and voltage limits by the battery management system (BMS), together with effective cell balancing and protection against overheating, mechanical damage, and electrical abuse [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Thermal behavior is especially critical, as excessive heat generation accelerates degradation mechanisms, increases internal resistance, and elevates safety risks [

21,

22,

23]. Lithium-ion cells typically operate most efficiently within a moderate temperature range, and pack-level designs generally aim to maintain both absolute cell temperatures and cell-to-cell temperature differences within narrow limits to ensure uniform aging and stable performance [

24,

25,

26].

Heat generation inside a lithium-ion cell originates from both reversible (entropic) and irreversible (ohmic and polarization) components. At higher discharge rates, irreversible heat dominates, whereas reversible heat contributions become more significant at lower C-rates [

27,

28,

29]. Thermal output also rises sharply near the end of charge and discharge due to increasing overpotentials and resistance effects [

18]. Low-temperature operation further complicates thermal behavior, leading to reduced capacity and increased stress during charging and discharging, which can accelerate long-term degradation [

25,

30].

Aging studies show that internal resistance varies strongly with state of charge (SOC) and temperature; impedance typically exhibits a minimum at intermediate SOC and rises at both high and low SOC levels [

31,

32,

33]. The growth of the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI), a major contributor to impedance increase and capacity fade, is strongly voltage-dependent and accelerates under deep-discharge conditions or when the anode is driven to very low potentials [

10,

11,

14,

15]. Improperly selected cutoff voltages can therefore intensify SEI thickening and increase charge-transfer resistance, ultimately reducing battery lifetime.

Voltage window selection also influences the stability of active materials and current collectors. Excessively low discharge voltages, particularly under high load, can induce copper current collector dissolution and promote internal short-circuit formation [

24,

27]. Deep depth-of-discharge (DoD) accelerates degradation compared to shallower voltage windows, whereas moderate DoD generally prolongs cycle life [

26,

33,

34]. Upper cutoff limits likewise affect cathode stability, as high-voltage operation increases electrolyte oxidation and lattice degradation in layered oxide cathodes [

8,

9,

28]. These effects are strongly material-specific: nickel-rich layered oxides are more sensitive to low anode potentials and high upper cutoffs, whereas materials such as LFP exhibit greater tolerance to the voltage window [

26,

28].

Since the practical cutoff behavior is not determined by voltage limits alone but is also governed by current-induced polarization and impedance growth, it is closely related to phenomena commonly described through Peukert-type capacity loss. While the classical Peukert equation was originally developed for lead–acid batteries, lithium-ion cells exhibit a more complex and condition-dependent response. The magnitude of the effect is smaller, but it is strongly influenced by state of charge (SOC), temperature, and electrode chemistry, meaning that the Peukert exponent cannot be treated as a fixed material constant. Several studies have demonstrated that temperature-dependent behavior [

35,

36], dynamic impedance growth [

34,

37], and stable operating conditions [

36] significantly affect the applicability of Peukert-type formulations. Consequently, modified or extended Peukert-based approaches—accounting for thermal effects, impedance variations, and SOC dependence—have been shown to provide useful insight into current-dependent capacity loss and have been successfully applied to advanced battery management and state-of-charge estimation tasks [

38]. The above-mentioned limitations and influencing factors were also observed in the present experimental context, indicating that Peukert-type behavior in lithium-ion cells is strongly influenced by operating conditions, including discharge rate, state of charge, and thermal state.

The reliability of lithium-ion batteries depends on the interaction between thermal behavior, impedance growth, SEI development, and the selected operating voltage window. Proper cutoff-voltage management, combined with effective thermal regulation, is therefore crucial for maximizing usable capacity and maintaining long-term electrochemical stability in both EV and ESS applications [

22,

29].

The aim of this study is to analyze the relationship between discharge cutoff voltage, usable capacity, and thermal behavior in cylindrical lithium-ion cells under different load conditions. The work focuses on identifying cell-specific cutoff-voltage ranges that provide an optimal compromise between energy extraction and thermal stress, using temperature rise and the Thermal Efficiency Ratio (TER) as evaluation metrics. These objectives are achieved through controlled-discharge experiments on two widely used cell formats at multiple cutoff voltages and C-rates. The second section presents the measurement procedure and calculation methods. The third section shows the results obtained from measuring two different cells. The fourth section presents the conclusions and future plans.

2. Materials and Methods

Two widely used cylindrical lithium-ion cell formats were investigated: 18650 (nominal capacity 2.6 Ah) and 21700 (nominal capacity 4.0 Ah). Both formats represent chemistries commonly employed in electric vehicles and stationary energy storage systems, including nickel–manganese–cobalt oxide (NMC) and lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) cathodes.

Before testing, each cell underwent three preconditioning charge–discharge cycles at 0.5 C to stabilize electrochemical performance and minimize initial variability. Manufacturer datasheets were used to define reference values for nominal voltage, rated capacity, and recommended operating voltage windows. To ensure statistical consistency, five cells of each format from the same manufacturer batch were tested in parallel, preventing single-cell bias in the results.

All experiments were carried out under controlled laboratory conditions at an ambient temperature of 25 ± 2 °C. Testing was performed using a programmable battery tester (Rigol EA-EL 3160-60A, Elektro-Automatik, Viersen, Germany), which operates in both constant current (CC) and constant voltage (CV) modes.

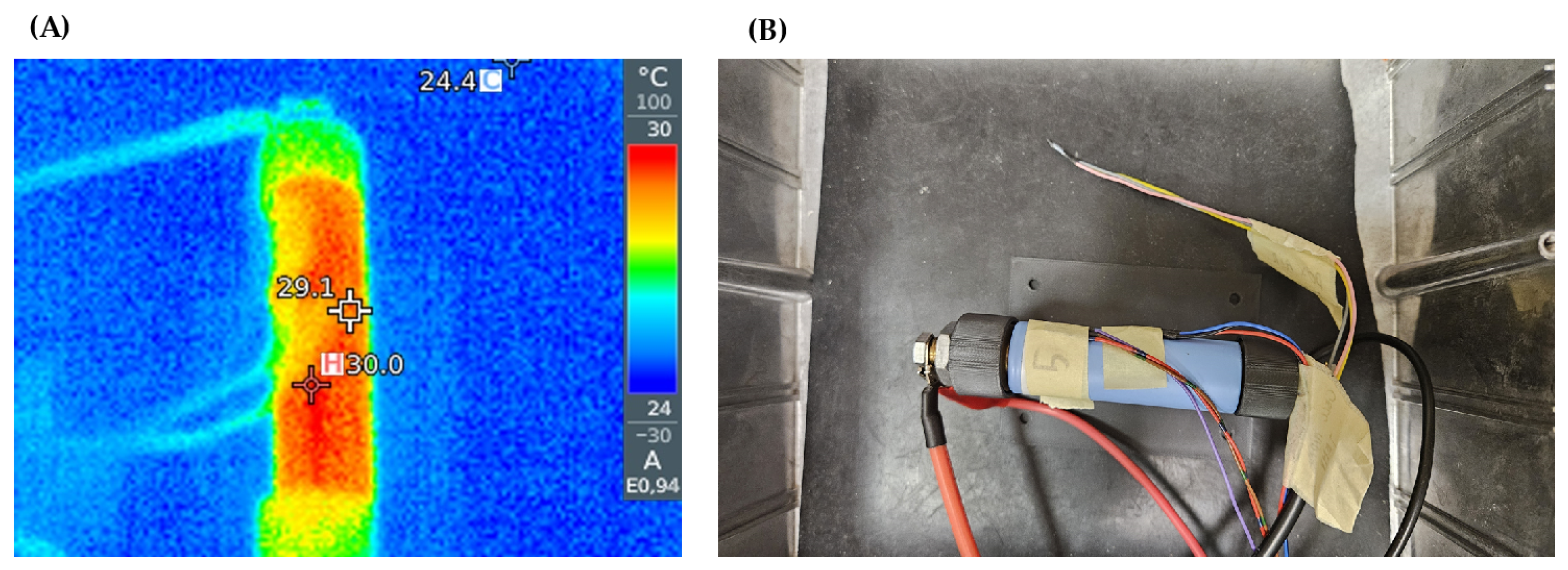

Cell surface temperatures were monitored using LM35 CAZ (Dallas, TX, USA) precision temperature sensors, with one sensor attached near the cell’s geometric center and another positioned close to the cathode terminal. In addition, thermal imaging was performed using a FLIR E5 (Wilsonville, OR, USA) infrared camera to verify spatial temperature uniformity and detect potential localized hot spots.

Figure 1 shows the measurement of the cell temperature.

Cells were fully charged to 4.20 V following a CC–CV protocol (0.5C charge current, cut-off at 0.05C). Controlled discharge cycles were then performed at four different load levels: 0.5C, 1C, 1.5C, and 2C, defined relative to nominal capacity. Each discharge cycle was terminated at one of the following cut-off voltages: 3.60 V, 3.30 V, 3.15 V, 3.00 V, 2.80 V, 2.60 V, 2.50 V. Between cycles, cells were allowed to rest until their surface temperature returned to within ±0.5 °C of ambient. Each condition (cut-off voltage × C-rate) was repeated three times for reproducibility.

Although the thermal response of lithium-ion cells could in principle be observed during a single full discharge to 2.5 V, this approach would have introduced cumulative heating effects and limited the comparability of intermediate states of charge. By defining multiple cut-off voltages (3.60–2.50 V) and repeating independent discharge cycles, the thermal behavior of each voltage range could be analyzed separately. This method eliminates time-dependent heat accumulation, ensures a direct correlation between usable capacity and temperature rise at each cut-off level, and better reflects practical BMS-controlled operation in real-world applications. Consequently, the adopted approach provides a more accurate characterization of the nonlinear thermal dynamics near the end of discharge.

Data Processing and Calculations

The usable discharge energy was obtained by integrating the product of current and voltage over time and normalizing it to the nominal energy content of each cell:

where

is the terminal voltage [V],

is the discharge current [A], and

is the discharge time until the predefined cutoff voltage is reached. To enable comparison between cells of different formats and capacities, the measured energy values were normalized to the nominal energy content specified in the manufacturer’s datasheet:

The cell surface temperature was recorded continuously during each discharge. It is important to note that normalized capacity values may slightly exceed 100%, because the manufacturer’s nominal capacity was used as the reference, while the measured capacity of the tested cells was in some cases higher than the rated specification. For analysis, the maximum temperature rise was defined as:

where

is the initial temperature at the beginning of discharge, and

is the maximum measured temperature. For each discharge cycle (defined by a given cutoff voltage and C-rate), a paired dataset was obtained: usable energy

and temperature rise

[°C]. These pairs enabled the construction of energy–temperature trade-off curves, illustrating how much additional usable capacity is gained as the cutoff voltage is lowered, and at what cost in terms of additional thermal stress.

To quantify the robustness of the thermal measurements, the relative standard deviation (RSD%) of the absolute measured temperature rise was calculated for each cutoff-voltage and C-rate condition. The average temperature rise

and the sample standard deviation

were determined as

where

denotes the measured temperature rise in the

i-th measurement sample, and N represents the number of samples considered under identical cutoff-voltage and C-rate conditions. he relative standard deviation was then obtained as

For each cutoff-voltage level, the

RSD values calculated at different C-rates were averaged to derive the Average

RSD% values reported in

Table 1.

In this analysis, the RSD refers to the absolute measured temperature rise in the cells (i.e., the amount of heating during discharge), and not to differences between temperature-rise values. Consequently, the RSD quantifies the cell-to-cell reproducibility of the heating behavior under identical operating conditions. Across the full voltage range, the variation remained low to moderate, typically in the range of about 2–6% for both the EVE40PL and the Samsung 26J cells. These relatively small RSD values indicate that the thermal trends shown in the figures are not dominated by measurement scatter and are representative of the characteristic behavior of each cell type.

To identify nonlinearities in the thermal behavior near the end of discharge, the temperature–energy slope was calculated numerically as

This slope represents the instantaneous thermal intensity per unit energy extracted, highlighting regions where a small gain in capacity results in a disproportionately high increase in heating. Physically,

dE/dT indicates how advantageous it is thermally to discharge the cell deeper. The unit of this indicator is J/°C (or Wh/°C), which can also be interpreted as the energy required to raise the temperature by one degree. At low temperature rises, however, the simple ratio

E/ΔT becomes unstable: when the denominator is very small or approaches zero (e.g., at the beginning of discharge), the value of the ratio may tend to infinity or zero, making it non-informative. This does not imply poor efficiency but reflects the mathematical sensitivity of the indicator. To mitigate this, a regularized denominator was introduced (see Equation (5)). The Thermal Efficiency Ratio (

TER) enables an objective comparison between the cutoff voltage and temperature in different cell types and applications (e.g., BMS integration):

where

is a small stabilizing constant that prevents the denominator from reaching zero. Importantly,

does not represent an additional temperature measurement but corresponds to the initial temperature offset used within the same dataset. Physically, this means that the first few tenths of a degree of temperature rise are not considered meaningful for analysis, as they primarily reflect sensor noise and environmental stabilization effects.

The TER quantifies the amount of usable discharge energy obtained per unit of temperature rise, representing the thermal conversion efficiency of the cell during operation. A higher value indicates that a larger portion of the released energy is converted into useful electrical work rather than dissipated as heat, corresponding to improved thermal performance. In practical applications, the TER can serve as an online efficiency indicator: when it drops below a predefined threshold, continued discharge becomes thermally inefficient. At this point, limiting or terminating the discharge can prevent excessive heat buildup and ensure safe, energy-efficient operation.

3. Results

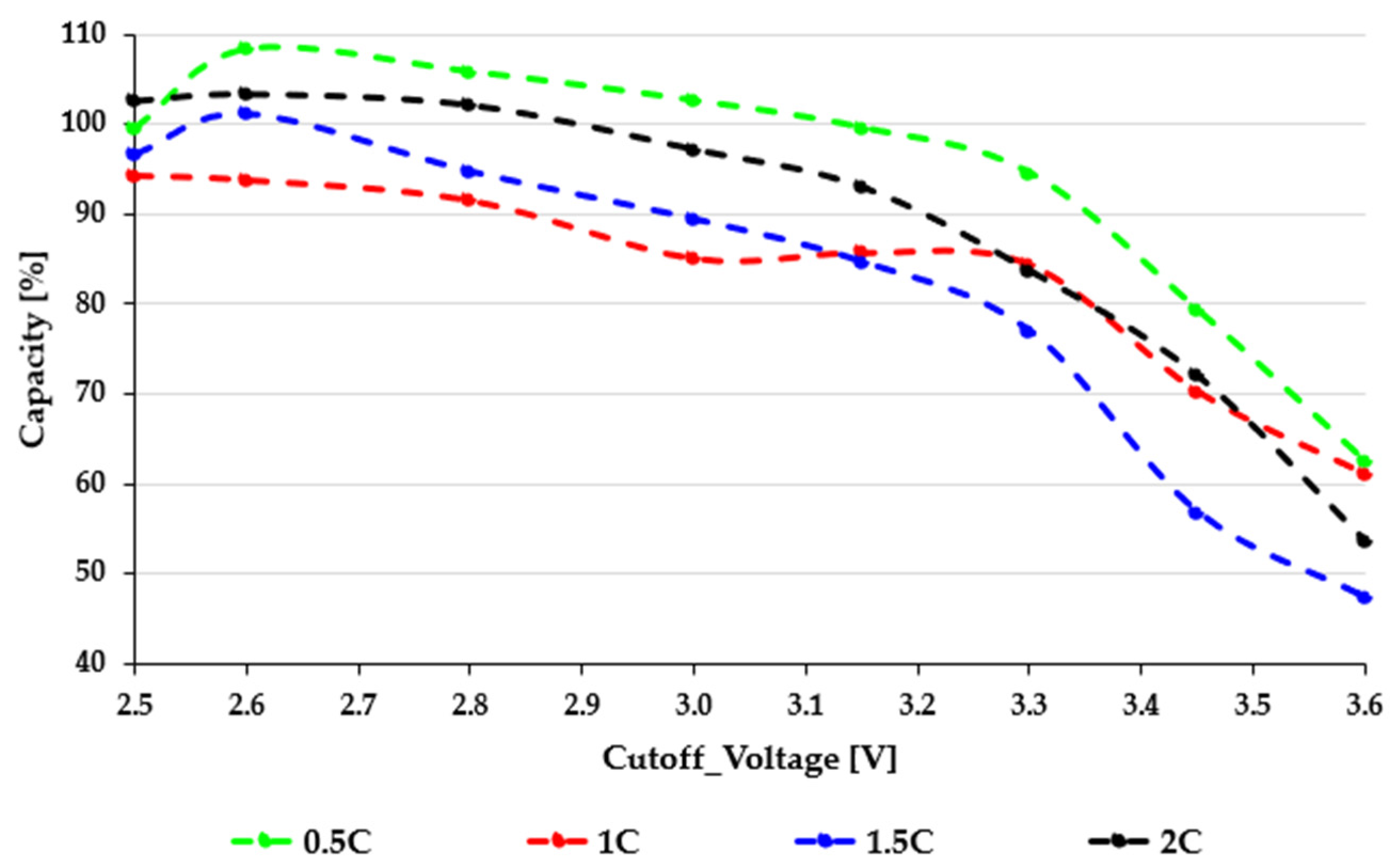

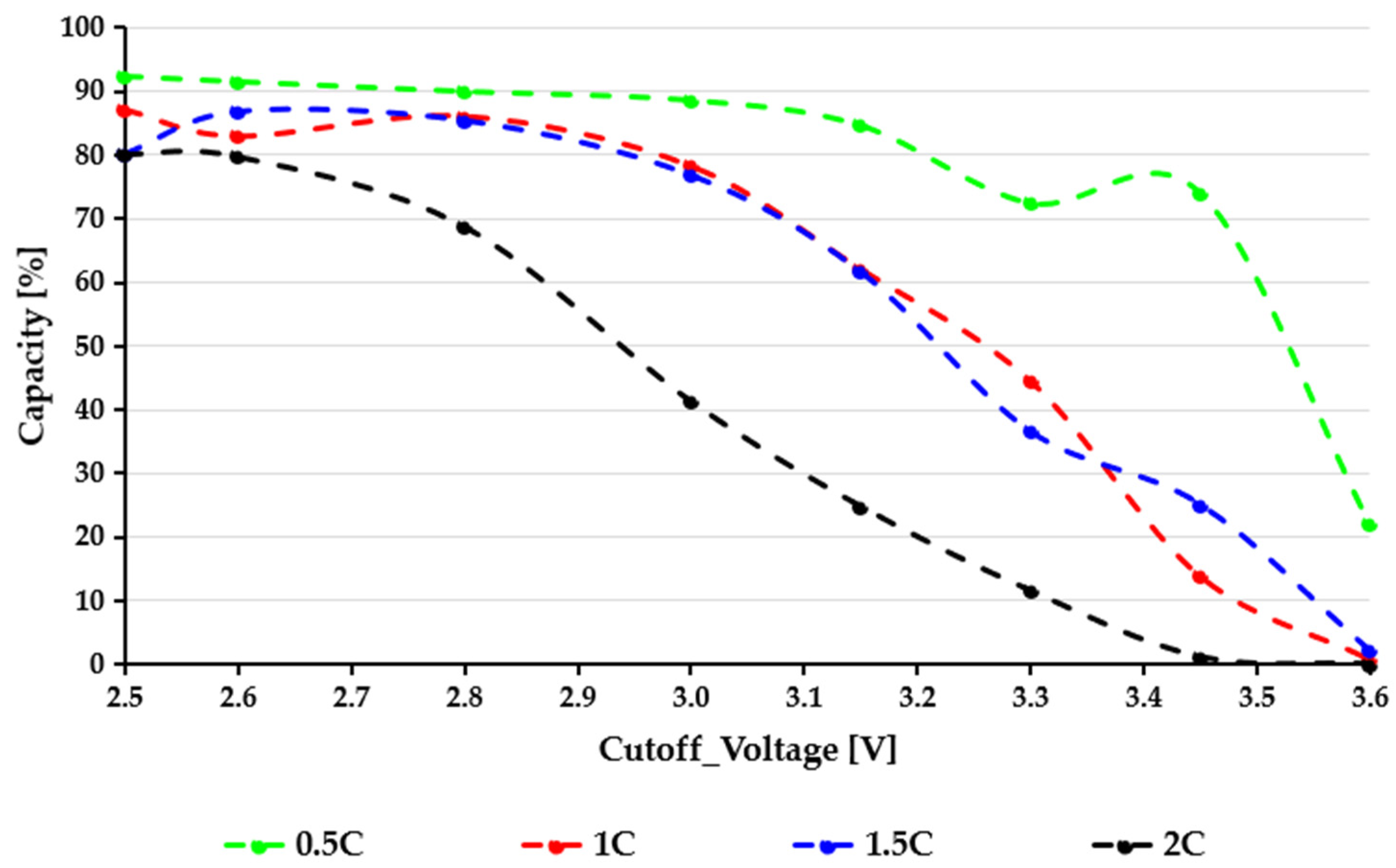

The discharge experiments show nonlinear relationships between cutoff voltage, usable capacity, and current load for both cell types. The capacity-voltage curves reveal that lowering the cutoff threshold boosts extractable energy only up to a limit that depends on the chemistry and load. After that limit, the additional capacity gain is minimal, while the thermal load increases significantly. There were notable differences between the 21700 and 18650 formats. This indicates that electrode design, internal resistance, and diffusion properties strongly affect sensitivity to lower discharge cutoff voltages. The following figures summarize the normalized capacity trends for each current level. They offer a comparison for assessing the best operational voltage range.

In the 21700 EVE40PL cells (

Figure 2), the green 0.5C curve shows excellent deep-discharge tolerance, maintaining high capacity across almost the entire cutoff range. The red (1C) and blue (1.5C) curves show stronger slope changes around 3.1 to 3.3 V, indicating the beginning of current-induced polarization. However, even the black 2C curve keeps a significant usable capacity down to about 2.8 V before it declines more sharply at higher cutoff thresholds. Values above 100% indicate that the actual measured capacity exceeded the nominal rating of the cell and do not reflect any methodological mistake. This behavior shows a moderate effect of the Peukert phenomenon, where increasing the current reduces capacity in a nonlinear but manageable way. The lack of sudden collapses suggests that the EVE40PL cell design, characterized by electrode thickness, porosity, and internal impedance, is well-suited for high-rate operation. Overall, the 21700 cells demonstrate strong performance, particularly at lower cutoff voltages, offering a wide operational range for applications that require high energy extraction.

By contrast, the Samsung ICR18650-26J cells (

Figure 3) display significantly higher sensitivity to both cutoff voltage and load. While the green 0.5C curve remains relatively stable between 2.6 and 2.8 V, a noticeable slope change appears around 3.0–3.2 V, above which all curves drop sharply. The red (1C) and blue (1.5C) curves show faster decline as the cutoff voltage rises, indicating higher ohmic losses and increased polarization at moderate loads. The black 2C curve clearly shows a severe Peukert effect: the available capacity drops rapidly with higher loads, and above a 3.3 V cutoff voltage, the usable capacity drops to nearly zero. This indicates a significant voltage sag caused by current, diffusion limits, and increased internal impedance that severely restricts the cell’s capacity to sustain high-rate discharge at higher voltage levels. The strong rate sensitivity of the 26J cells is consistent with their electrode design, which prioritizes cost-efficient energy density over high-power capability. A comparative evaluation of the two figures highlights a fundamental difference in discharge stability. The EVE40PL 21700 cells show smooth capacity degradation and maintain functional performance even at elevated C-rates, while the 26J cells exhibit sharp nonlinear drops, especially when the cutoff voltage is raised above 3.0–3.2 V. This difference has significant practical consequences: choosing inappropriate cutoff values for the 18650 cells can lead to substantial usable capacity losses during actual high-load use. In comparison, the 21700 cells provide a wider and more tolerant operating range. Another interesting observation in

Figure 1 is that, in certain cutoff regions, especially between 2.6 and 2.8 V, the 2C discharge produces a slightly higher normalized capacity than the 1.5C or even the 1C curves. This seemingly counterintuitive behavior does not contradict electrochemical theory; rather, it reflects the combined effect of load-induced voltage sag, subsequent relaxation, and the nonlinear Peukert characteristics of high-power NMC cells. At high current, the cell reaches the cutoff voltage sooner, but immediately after load removal, the terminal voltage rebounds to a higher OCV level. As a result, the discharge ends at a shallower effective depth of discharge compared to lower C-rates, which increases the calculated usable energy. Additionally, the 21700 cell’s low internal resistance and stable polarization at high currents lead to a quasi-plateau behavior, resulting in slightly higher energy output 2C. This phenomenon, often referred to as a “reverse Peukert segment”, is typical of high-rate cylindrical cells and demonstrates the stability of the EVE40PL design under demanding load conditions [

39].

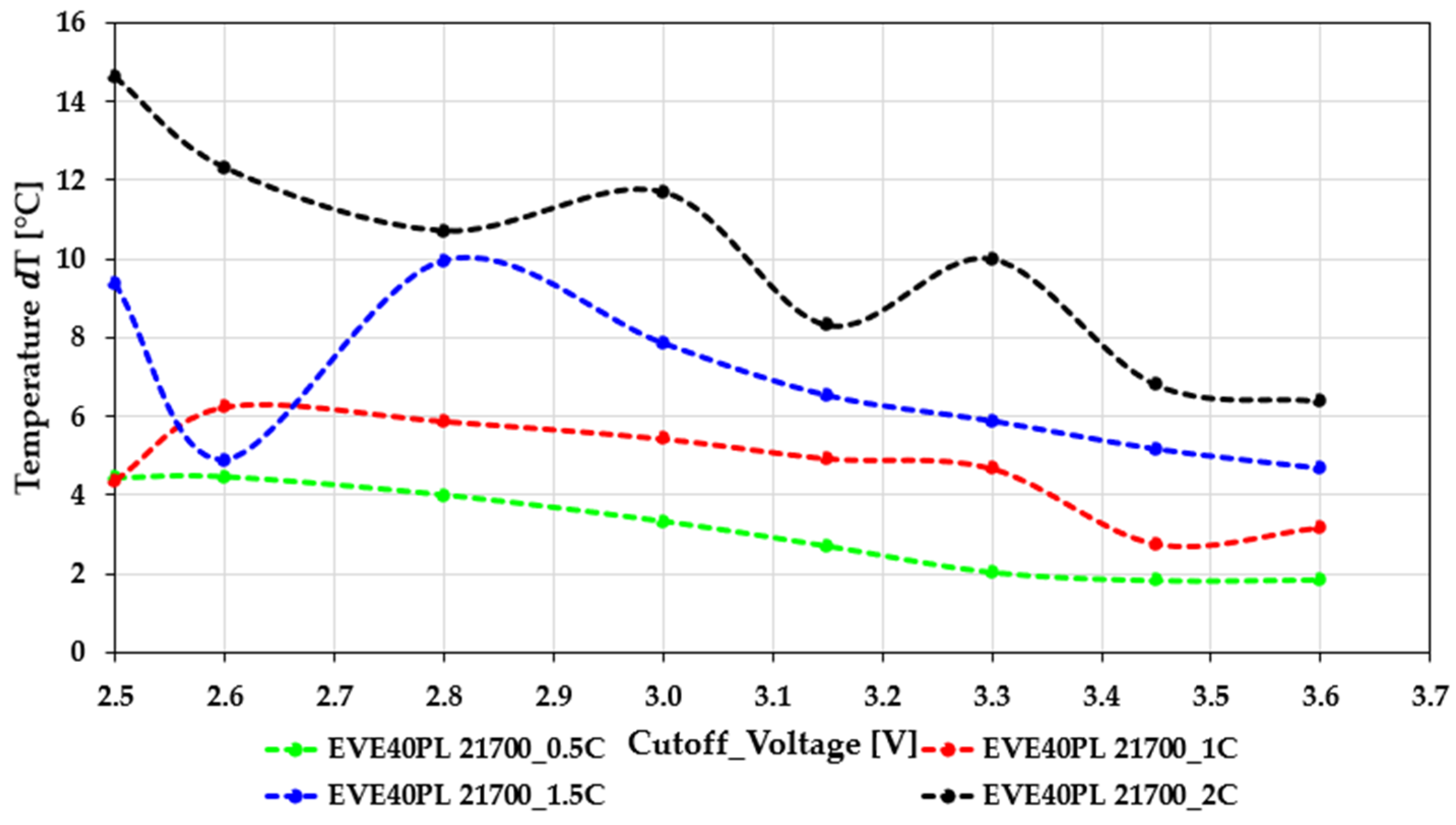

The thermal measurements provide further insight into how internal losses and polarization effects evolve at different discharge rates and cutoff levels.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the maximum temperature increase (ΔT) during each discharge cycle for the same four C-rates as in the capacity plots (0.5C—green, 1C—red, 1.5C—blue, 2C—black). As expected, higher currents typically lead to increased heating; however, the shape, slope, and relative separation of the temperature curves show clear, cell-dependent nonlinearities. These thermal characteristics closely relate to the load-dependent capacity behavior discussed earlier and emphasize key differences in design, internal resistance, and SOC-dependent impedance between the two cell types.

In the EVE40PL 21700 cells (

Figure 4), the temperature increase stays moderate across the entire range of cutoff voltages and C-rates. This shows that this type of cell manages heat well and has stable polarization characteristics. At a low discharge current (0.5C), the temperature rise is limited to about 3 to 5 °C and gradually decreases as the cutoff voltage goes up. This change reflects lower energy throughput and reduced resistive losses. At 1C and 1.5C, ΔT increases slightly and shows a small SOC-dependent maximum around 2.6 to 2.8 V. This behavior appears in the area where charge-transfer resistance rises more quickly near the lower SOC boundary, causing a temporary increase in irreversible heat generation. Still, these changes remain moderate, showing that kinetic limits are effectively managed by the cell’s design. At 2C, the thermal load rises significantly, reaching 14 to 15 °C at the deepest discharge point (2.5 V). Despite the higher current, the ΔT curve stays smooth with no sudden changes or instabilities. A characteristic plateau forms between 2.9 and 3.2 V, where the cell maintains relatively constant polarization behavior despite the higher load. The overall trend, which shows a steady decline in ΔT with increasing cutoff voltage, indicates strong high-rate capability. The controlled temperature profile matches earlier capacity measurements, confirming that the EVE40PL cell is designed for sustained discharge even under tough electrical conditions.

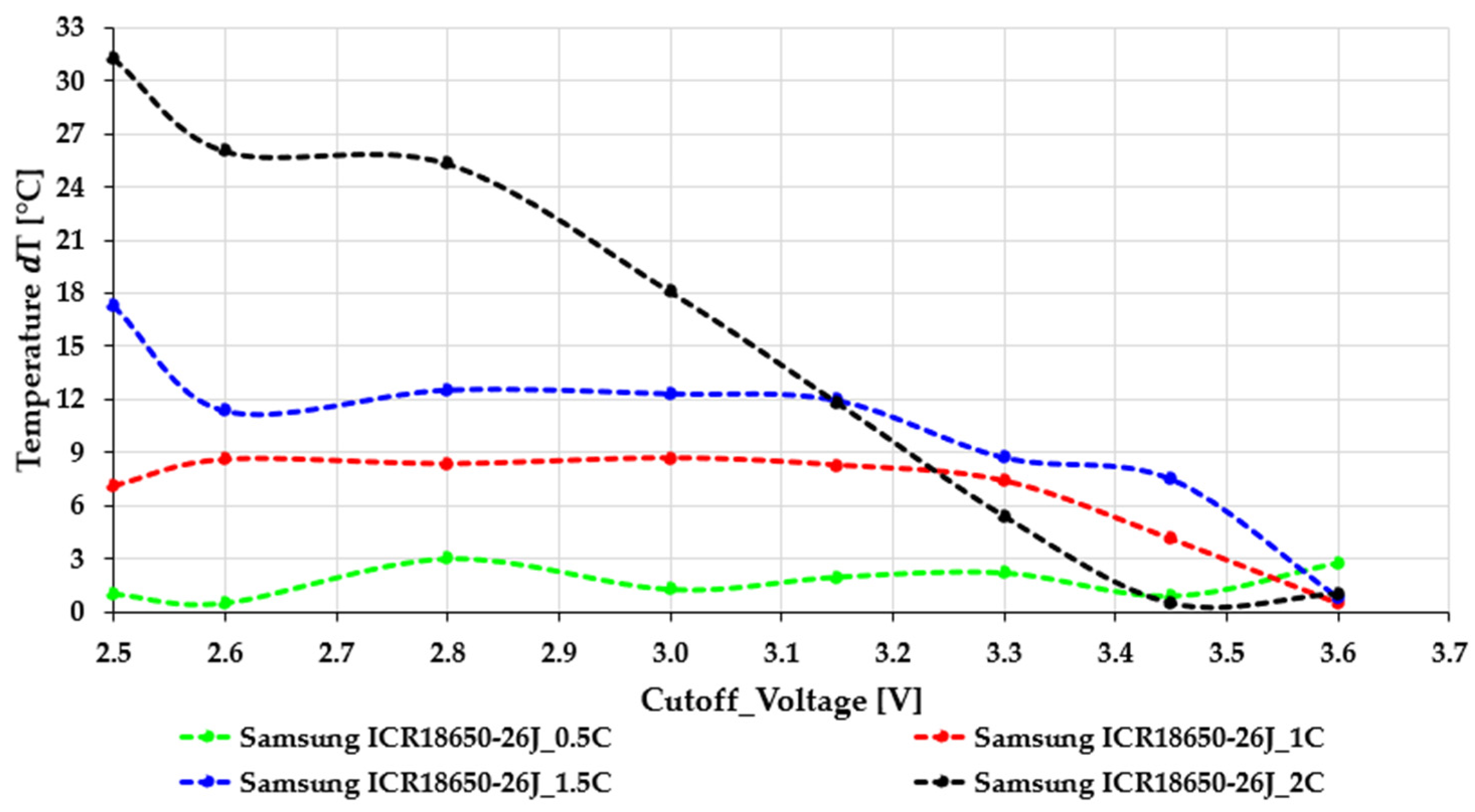

The Samsung ICR18650-26J cells (

Figure 5) exhibit considerably stronger thermal sensitivity, especially under moderate and high discharge rates. This is consistent with their steeper capacity losses at elevated C-rates and higher internal resistance. At low load (0.5C), heating remains minimal, typically below 3 °C, and shows only mild SOC-dependent fluctuations. However, at 1C the cell already displays a broad ΔT peak around 2.8–3.0 V, suggesting that polarization and charge-transfer losses are more pronounced than in the 21700 counterpart. The behavior becomes critical at higher discharge currents. At 1.5C, ΔT reaches 12–13 °C at low cutoff voltages, roughly matching the thermal load of the 21700 cell at 2C. This indicates that the 26J chemistry experiences significantly higher resistive and kinetic losses even at intermediate discharge rates. At 2C, the thermal response becomes extreme: ΔT exceeds 30 °C at 2.5 V, more than double the temperature rise in the 21700 cell under identical conditions. The sharp decrease in ΔT at higher cutoff voltages reflects the fact that, at 2C, the 26J cell provides almost no usable capacity once the cutoff voltage exceeds approximately 3.3 V—therefore, virtually no heat is generated. The steep, nonlinear shape of the 2C curve points to substantial SOC-dependent impedance growth, severe voltage sag, and limited high-rate tolerance. The thermal results therefore support the previous capacity findings, showing that the 26J cell design is thermally and electrically limited under high current conditions. Across the full measurement range, the absolute surface temperature increased systematically with discharge rate for both cell formats. For the Samsung ICR18650-26J cells, temperatures typically remained below ~30 °C at 0.5C, increased to approximately 25–35 °C at 1C, extended to roughly 30–50 °C at 1.5C, and reached a broad range of about 25–55 °C at 2C, depending on the applied cutoff voltage. In contrast, the EVE40PL 21700 cells exhibited a consistently narrower and lower temperature range under comparable conditions, remaining below ~30 °C at 0.5C, around 25–30 °C at 1C, increasing to approximately 25–35 °C at 1.5C, and staying within roughly 25–40 °C at 2C.

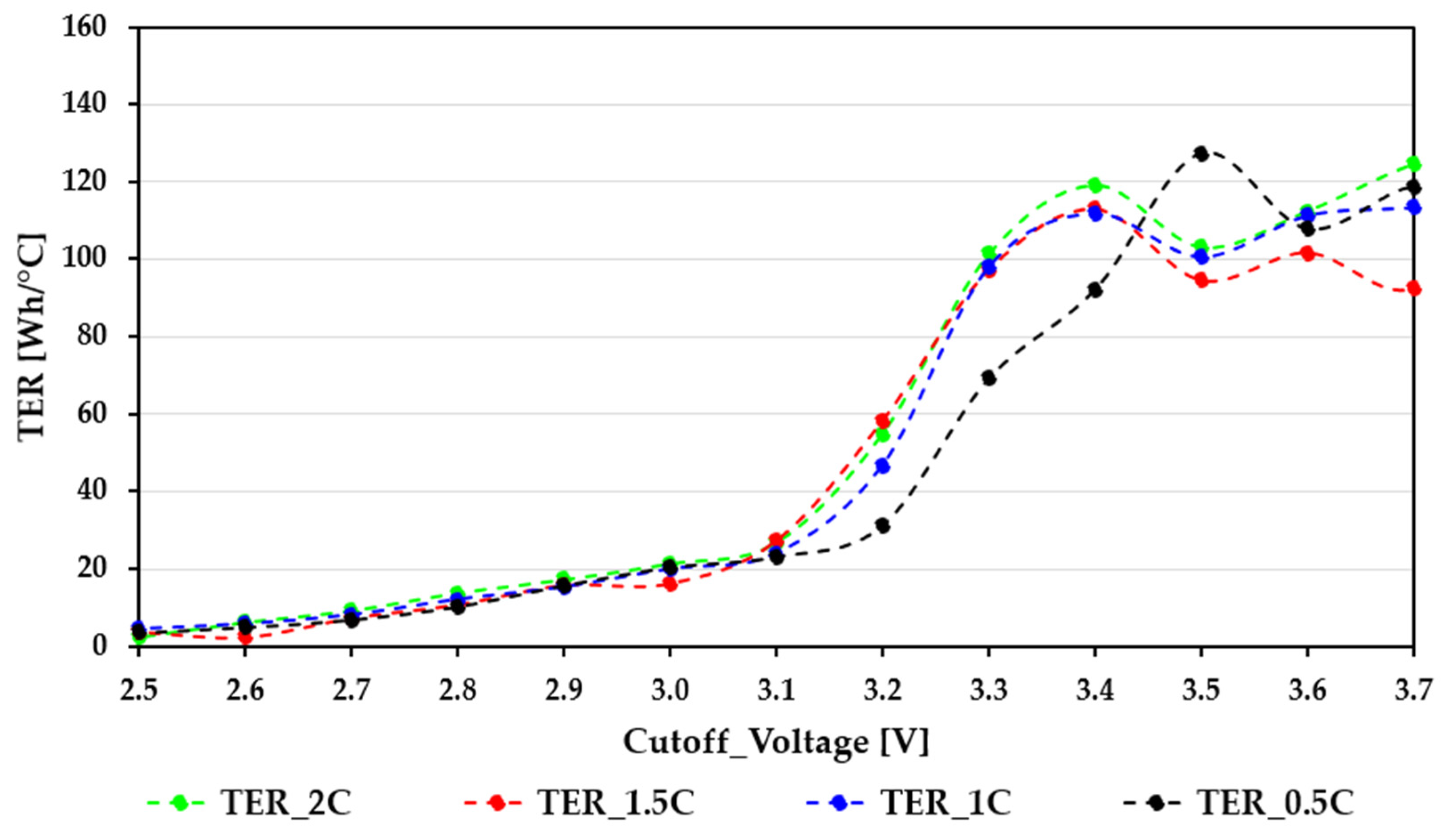

The evaluation of the Thermal Efficiency Ratio (TER) provides an integrated perspective on the balance between usable energy extraction and heat generation during discharge. Whereas capacity and temperature rise individually describe electrical and thermal behavior, TER highlights how effectively each cell converts stored chemical energy into electrical output without imposing excessive thermal stress. A higher TER indicates better electro-thermal performance, while a lower TER signifies disproportionate heating compared to the energy delivered.

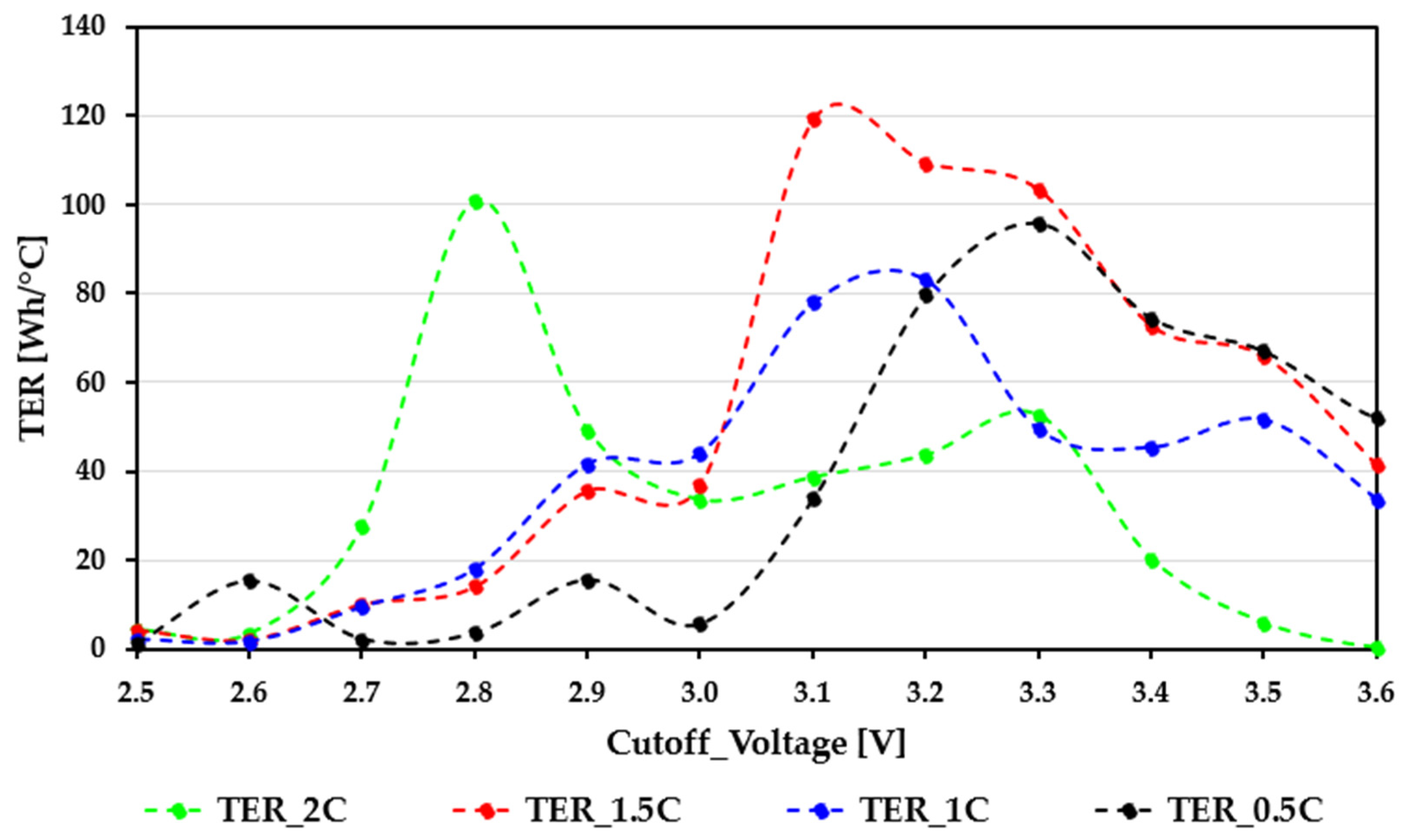

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 summarize the TER characteristics of the EVE40PL 21700 and Samsung ICR18650-26J cells across different cutoff voltages and C-rates, using the same color scheme as the previous figures (0.5C—black; 1C—blue; 1.5C—red; 2C—green).

The TER curves of the EVE40PL 21700 cells display a smooth, load-consistent, and predictable increase, reflecting the cell’s balanced electro-thermal behavior. In the deep discharge region (2.5–2.8 V), TER values remain low (typically 0–10 Wh/°C) for all different C-rates. This is the operating zone where charge-transfer resistance increases noticeably at low SOC and ΔT is at its maximum, suppressing thermal efficiency. Despite the higher extractable energy, the substantial heating limits the TER, as expected for this SOC interval. As the cutoff voltage rises from 2.8 to 3.1 V, TER gradually increases. This trend occurs because ΔT increases faster than the usable capacity, leading to an improved energy-to-heat ratio. All four load curves follow similar paths, indicating that the cell maintains stable thermal characteristics regardless of the discharge current. The most notable behavior appears between 3.1 and 3.4 V, where the TER reaches its maximum values (≈80–130 Wh/°C) for all C-rates. This zone indicates the optimal efficiency window, where the thermal load is significantly lowered while the extractable energy remains considerable. The close alignment of the four curves further shows that the EVE40PL design provides stable polarization and low internal resistance even at higher load levels. At very high cutoff voltages (3.4–3.6 V), the TER curves show small fluctuations due to the minimal temperature rise, which increases sensitivity to measurement noise and the stabilization constant in the regularized denominator. However, the thermal efficiency remains generally high, confirming that the EVE40PL cells maintain advantageous electro-thermal performance even when only a small part of the nominal capacity is utilized. Overall, the TER behavior confirms the strong high-rate performance of the EVE40PL 21700 cells and their suitability for applications needing both high electrical output and managed thermal characteristics.

The TER traces of the Samsung ICR18650-26J cells show clear nonlinear behavior and significant differences between load levels. This indicates noticeable electro-thermal instability when the cell is pushed toward higher discharge rates. In the lowest cutoff region (2.5 to 2.8 V), the TER values vary widely across different C-rates. The 0.5C curve behaves predictably, while the 1.5C and 2C curves display sudden jumps and drops. These irregularities come from a mix of SOC-dependent polarization, uneven temperature increases, and the high sensitivity of TER in operating zones where heat generation is either low or fluctuates rapidly. The large 2C spike near 2.8 V is a temporary thermal effect, not a sign of a stable efficiency point. Between 2.8 and 3.1 V, the 1C and 1.5C curves rise steadily, creating distinct peaks around 3.0 to 3.1 V, reaching about 120 to 130 Wh/°C. During this short range, thermal efficiency improves because the temperature rise slows down faster than the cell’s usable energy decreases. The 2C curve acts differently: after an initial spike, it quickly drops, showing the effects of significant heating and increased internal resistance, which reduce both capacity and efficiency at high current levels. From 3.1 to 3.4 V, the TER stays relatively high at lighter loads (0.5C to 1C), but efficiency declines sharply as the current increases. This drop aligns with the fast loss of usable capacity already seen in the discharge curves, along with residual thermal load, which together lower the energy-per-degree ratio.

The results also demonstrate that the thermal behavior of the Samsung ICR18650-26J cells is heavily influenced by the applied discharge load. Instead of a single, universally optimal cutoff threshold, the cell requires load-adaptive lower voltage limits because its heating pattern varies significantly with the current level. At low discharge rates, lower cutoff voltages can be applied safely; however, at higher loads, the rapid temperature increase observed below ≈approximately 3.0 V requires a higher cutoff threshold to prevent thermal stress. This suggests that the 26J chemistry benefits from a dynamic cutoff management approach, where the lower voltage limit is constantly adjusted in response to real-time temperature changes and load conditions. Such an approach—combined with continuous thermal monitoring—could significantly enhance operational safety and sustain efficiency in practical BMS implementations.