Abstract

The mammary gland is a valuable model in cancer research and developmental biology. Gene delivery techniques are crucial for mammary tissue research to understand how genes function and study on diseases such as cancer. Viral vector-based approaches provide a high degree of transduction efficiency, but they raise safety and immunogenicity concerns, whereas non-viral vector-based approaches are considered safer and have lower immunogenicity than viral methods. Unfortunately, non-viral gene delivery has rarely been applied to the mammary glands because it is technically challenging. Here, we developed a novel method for in vivo transfection of epithelial cells lining murine mammary glands via intraductal injection of plasmid DNA using a breath-controlled glass capillary and subsequent electroporation (EP) of the injected area. Female mice were transfected with plasmids harboring the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene. Widespread EGFP fluorescence was observed in the mammary epithelial cells of the ducts and adipocytes adjacent to the ducts. As this in vivo gene delivery method is simple, safe, and efficient for gene transfer to the mammary glands, we named this technique “Mammary Intraductal Gene Electroporation” (MIGE). The MIGE method is a useful experimental tool for studies on mammary gland development and differentiation as well as breast cancer research.

1. Introduction

The incidence of breast cancer, the most common cancer in women worldwide, has been increasing [1]. In Japan, one in nine women is predicted to develop breast cancer in their lifetime [2]. Therefore, countermeasures should be developed urgently. The mammary gland is a major focus area in the fields of breast cancer research and developmental biology because of its complex and dynamic tissue structure [3,4].

Genetic engineering helps to understand the functions of specific genes in the mammary glands and creating animal models of human diseases [5,6]. Until now, viral vectors have been frequently used to introduce genes into the mammary glands via intraductal injection in mice, where vectors (such as retroviruses, lentiviruses, and adenoviruses) are used to infect mammary epithelial cells to deliver the genes of interest [7]. However, this approach has some limitations. For instance, retroviral and lentiviral vectors may exhibit random chromosomal integration of transgenes; this phenomenon may lead to insertional mutagenesis, in which the transgene disrupts an existing gene, leading to potential mutations, gene inactivation, or unintended activation of neighboring genes. Repeated administration of adenoviral vectors in vivo is difficult because of a strong host immune response. Therefore, non-viral vectors are considered safe for gene transfer, despite significant challenges, including low gene transfer efficiency, poor reproducibility, and potential cytotoxicity. Furthermore, in vivo electroporation (EP) is a physical method for gene delivery that uses high-voltage electrical pulses to create temporary pores in the cell membrane, allowing DNA to enter the cell. After the pulse, the cell membrane reseals, and the gene is expressed. This non-viral technique is efficient and adaptable; this method is a promising alternative to viral methods for gene therapy because it is associated with a low risk of immunogenicity and gene mutation, and therefore, is extremely safe [8,9]. In addition, the procedure is easy to perform and highly reproducible. Unfortunately, reports on in vivo EP-based gene delivery into the mammary glands are limited.

To the best of our knowledge, an extensively used method for delivering genes to mammary epithelial cells is the intraductal injection of a solution containing nucleic acids, because this method allows targeted and localized gene delivery without affecting other organs [10]. To date, researchers have only used injection needles for conventional intraductal injections. However, this approach is often accompanied by a high risk of accidental penetration of the mammary duct owing to a lack of precision. Therefore, we aimed to develop a precise and minimally invasive intraductal injection technique. In this study, we used 32-gauge injection needles before inserting a breath-controlled glass capillary. The needle was first inserted at a depth of approximately 0.25 mm through the nipple under observation using a dissecting microscope, and subsequently, a glass capillary containing a plasmid solution was inserted. This procedure decreases the risk of accidental penetration of the mammary duct and makes injection into the duct easier and safer than conventional procedures.

In this study, we examined whether epithelial cells lining the murine mammary glands could be effectively transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-expressing plasmids via intraductal injection of a solution containing the plasmids using a breath-controlled glass capillary and subsequent EP of the injected area. We have named this technique “mammary intraductal gene electroporation” (MIGE). Here, we describe the MIGE procedure in detail and discuss the utility of MIGE for conducting basic studies on the mammary gland development and differentiation as well as breast cancer research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Female B6C3F1 (a hybrid of C57BL/6N and C3H/HeN) mice, aged 8–10 weeks, were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). The mice were housed in a pathogen-free facility under controlled conditions with a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on from 07:00 to 19:00). Food and water were provided ad libitum. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at the National Defense Medical College (permit no.: 23053) and were approved by the National Defense Medical College Committee on Recombinant DNA Security (permit no.: 2024-11).

2.2. Plasmid DNA

The plasmid used in this study was pCE-29, in which the EGFP cDNA expression is controlled by a ubiquitous and strong cytomegalovirus early enhancer/chicken beta-actin-based promoter (CAG) [11]. This plasmid was amplified after transformation into DH5α competent cells (BioDynamics Laboratory Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and purified using a Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands). The purified DNA was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a final concentration of 0.25 µg/µL.

2.3. Intraductal Injection and In Vivo EP

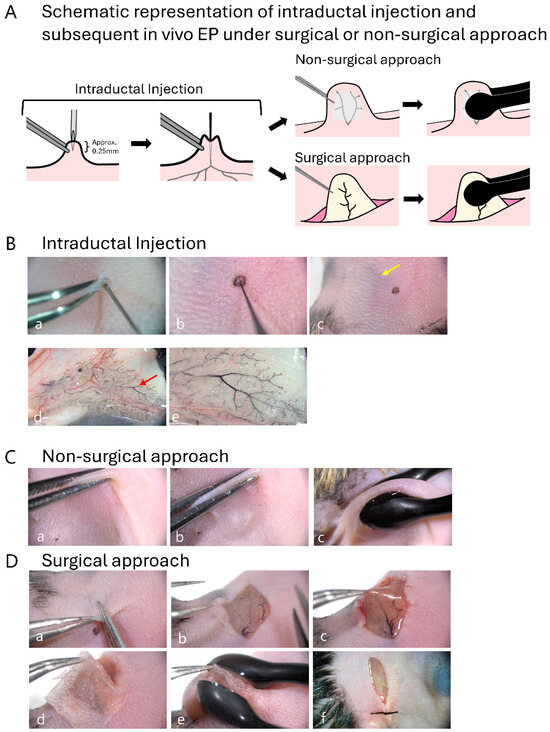

Mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of an anesthetic mixture of medetomidine, midazolam, and butorphanol [12]. Abdominal hair was first removed using a commercial depilatory cream. Figure 1A illustrates the procedure of intraductal injection and subsequent in vivo EP. After intraductal injection, in vivo EP was performed using surgical and nonsurgical approaches. A sterile 32-gauge needle (0.26 × 12 mm, Dentronics, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted at a depth of approximately 0.25 mm through the top of the nipple under observation using a dissecting microscope (Figure 1A,B(a–c)). A breath-controlled glass capillary was prepared by pulling a glass pipette (cat. no. 2–000-050; Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA, USA) using a needle puller (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). The resulting fine tip was then carefully trimmed using microscissors to create an opening with a final outer diameter of approximately 60–65 µm. To ensure accurate dosage, a 10 µL droplet of the plasmid solution (containing 0.25 µg/µL circular plasmid DNA and 0.5% Indian ink [Nippon Sumishoyu Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; used to visualize injected solutions]) was prepared on a hydrophobic surface using a micropipette. The entire droplet was then aspirated into the glass capillary. The capillary was then inserted into the needle entry point, and the entire volume of the solution was slowly released into the mammary ductal tree under gentle oral pressure (Figure 1B(b–e)).

Figure 1.

The procedure for in vivo electroporation (EP)-mediated gene delivery to the murine mammary gland. (A). Schematic presentation of an experimental line involving opening of a hole in the fourth nipple, intraductal injection, and subsequent in vivo EP (right side). (B). Key steps of intraductal injection. A pilot hole is first created in the nipple with a 32-gauge needle (a), followed by insertion of a breath-controlled glass capillary (b) under observation using a dissecting microscope. Distribution of the injected solution can be visualized through the skin by the presence of co-injected Indian ink (arrow in (c)). The solution injected into the mammary duct is clearly discernible in the excised gland (arrow in (d)). When a portion (indicated by arrow) of (d) is magnified, widespread liquid penetration throughout the ducts can be seen (e). (C). Non-invasive (non-surgical) approach for in vivo EP of mammary glands. After the skin is picked up using forceps (a), conductive gel is applied to the skin (b), and the skin is subsequently held using tweezer-type electrodes (c). (D). Surgical approach for in vivo EP of mammary glands. A skin incision is made to expose the mammary fat pad (a,b). The fat pad is pulled out (c) and then wrapped in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-soaked Kimwipes (d). The wrapped portion is held using tweezer-type electrodes (e). After EP, the skin is sutured (f).

Following injection, two types of in vivo EP were performed, as shown on the right side of Figure 1A. For the nonsurgical (transcutaneous) approach, a conductive gel (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was first applied to the skin surrounding the injected nipple, and then the skin near the nipple was picked up using forceps (Figure 1C(a,b)). Subsequently, the gel-coated area was held between tweezer-type electrodes (cat. no. CUY650P5; Nepa Gene, Chiba, Japan) with a 1 mm gap, and square-wave electric pulses (70 V; 10 pulses with a pulse duration of 50 ms) were applied (Figure 1C(c)). For the surgical approach, a small incision was made on the skin near the nipple (Figure 1D(a)). The overlying skin was carefully moved using forceps to expose the underlying fat pad (Figure 1D(b)). Next, the exposed fat pad was pulled out using forceps (Figure 1D(c)) and wrapped in a small piece of Kimwipes (Nippon Paper Crecia, Tokyo, Japan) soaked in PBS (Figure 1D(d)). This treatment was performed to ensure uniform electrical contact and prevent tissue damage as much as possible. The Kimwipes-covered fat pad was held using tweezer-type electrodes, and then square-wave electric pulses (30 V; 10 pulses with a pulse duration of 50 ms) were applied (Figure 1D(e)). After completing the in vivo EP, the incision was closed using surgical sutures (Figure 1D(f)). As described in the Section 3, the surgical approach provided excellent transfection efficiency. Based on these findings, all subsequent experiments were performed using the surgical approach.

2.4. Tissue Harvesting and Fluorescence Imaging

At 2 days post-EP, the mice were euthanized, and the portion containing the transfected mammary glands was excised. The excised glands were immediately spread onto the surface of a 60 mm tissue culture dish and subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 1 h at 4 °C. Tissue clearing was performed according to the protocol described by Landua et al. [13]. Briefly, the fixed tissues were cleared by sequential incubation: first in 50% glycerol/PBS overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation in 75% glycerol/PBS and 100% glycerol for 1 h each at room temperature. Analysis of EGFP expression in the cleared whole-mount tissues was performed using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (cat. no. SZX10; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). All fluorescence images were acquired using consistent settings to ensure comparability between samples.

2.5. Immunohistochemistry

The EGFP-positive regions identified via stereomicroscopic observation were carefully excised from the treated mammary gland tissue samples. These trimmed tissue pieces were then post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C. Similarly, untreated mammary glands (wild-type [WT] samples) were also fixed in 4% PFA. For WT control samples, the mammary gland tissue corresponding to the anatomical location where MIGE was applied was harvested and processed similar to the other samples to ensure anatomical consistency.

The fixed tissues were subsequently defatted, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin wax according to standard protocols. Then, 3-µm thick sections were prepared using a microtome. For staining, the sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed by autoclaving the slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min at 95 °C. After blocking endogenous peroxidase activity, non-specific binding was blocked by incubating the sections in 5% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories Inc., Newark, CA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit anti-GFP polyclonal antibodies (dilution, 1:1250; cat. no. #2555S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). After washing, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies, namely, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-immunoglobulin G antibodies that recognize both heavy and light chains (anti-IgG [H&L]; dilution, 1:500; cat. no. AB205718; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), for 3 h at 4 °C. Signals were visualized using the ImmPACT DAB Kit (Vector Laboratories Inc.). Finally, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted for observation under a light microscope (cat. no. CK2; Olympus).

For double immunofluorescence staining to identify mammary gland ductal cells transfected by MIGE, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-GFP (dilution, 1:1250) and mouse anti-cytokeratin 8 (CK8) (dilution, 1:50; cat. no. sc-8020; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). After washing with PBS, the section was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (dilution, 1:500; cat. no. ab150077; Abcam) and CoraLite 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (dilution, 1:500; cat. no. SA00013-2, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA). Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (cat. no. H-1200, Vector Laboratories). Fluorescence images were acquired using BZ-X810 (Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

2.6. Quantitative Analysis

Immunohistochemically stained sections were subjected to cell counting to evaluate transfection efficiency quantitatively. For each mouse in the MIGE-treated and WT groups, the entire tissue section (approximately 6 mm × 4 mm) containing the mammary ducts was analyzed. The number of EGFP-positive epithelial cells and the total number of epithelial cells lining the ducts within the whole section were manually counted. The transfection efficiency was calculated as the percentage of EGFP-positive cells relative to the total number of epithelial cells. Statistical significance was analyzed using Student’s t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Successful Introduction of Exogenous Solution into Murine Mammary Glands

Our novel method was based on intraductal injection using a breath-controlled glass capillary after creating a hole at the top of the nipple using a 32-gauge needle. The method was effective and reproducible with respect to delivery of the solution into the mammary duct. As shown in Figure 1B(d,e), a widespread distribution of the injected solution was discernible in the mammary ducts near the injected nipple. This result was achieved in 100% of the trials with survival rate of 100% (23/23 tested). Furthermore, visual inspection demonstrated that gross signs of tissue necrosis and severe inflammation were not observed in the harvested mammary glands. Histological examination using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining also confirmed the above finding: tissue architecture was well preserved in the absence of overt infiltration of inflammatory cells (Supplemental Figure S1).

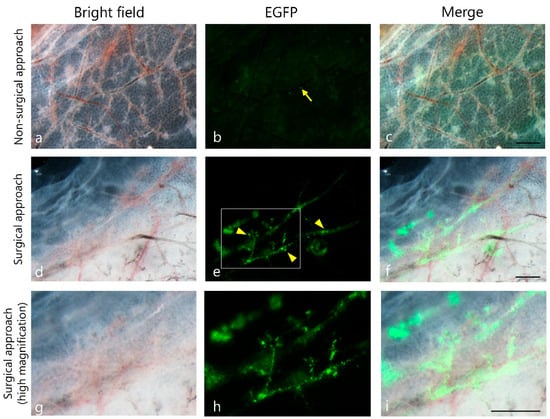

3.2. In Vivo EP of Surgically Exposed Mammary Fat Pad Is Critical for Efficient Gene Transfer into Mammary Glands

To optimize our gene delivery protocol, we compared two approaches, nonsurgical (transcutaneous) and surgical, in which the mammary fat pad was exposed (Figure 1A). The nonsurgical approach resulted in poor transfection efficiency, as weak or no EGFP-derived fluorescence was detected (arrow in Figure 2). In contrast, robust EGFP expression was observed using the surgical approach, as bright green fluorescence was clearly observed along the tubular structures of the specimens (arrowhead in Figure 2). Furthermore, sporadic EGFP expression was observed in the adipocytes adjacent to the ducts (arrows in Supplemental Figure S2A), indicating that these cells could also be transfected using this system.

Figure 2.

Comparison of non-surgical and surgical approaches for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene delivery into mammary ducts. Representative fluorescence microscopic images showing EGFP expression in mammary ducts following in vivo EP conducted via two different methods: non-surgical and surgical. Weak EGFP signals (arrow) were observed using the non-surgical approach (top row; (a–c)). In contrast, robust EGFP expression along the ductal structure (arrowheads in (d–f)) was observed using the surgical approach (middle row). The boxed region shown in (d–f) has been highly magnified in (g–i), respectively. Scale bar = 500 µm.

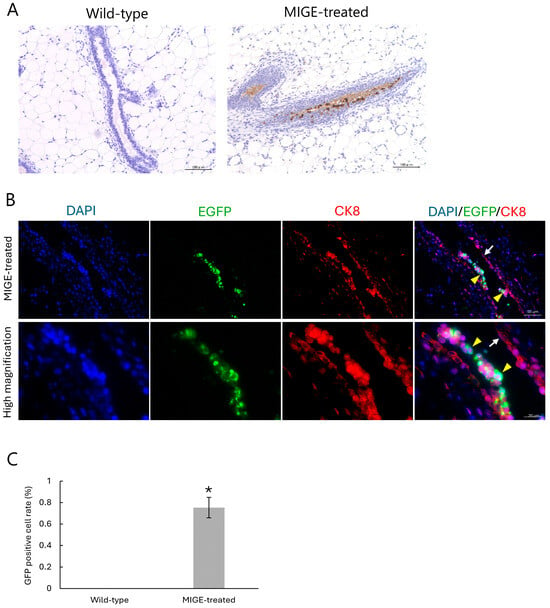

3.3. Transgene Expression Is Localized to Mammary Epithelial Cells

Next, we performed immunohistochemical analysis using paraffin-embedded sections (including EGFP-positive regions) obtained after in vivo EP of surgically exposed mammary fat pads. First, DAB staining demonstrated that EGFP expression was localized to the cytoplasm of epithelial cells lining the mammary ducts (Figure 3A). To definitively confirm the identity of these transfected cells, we performed double immunofluorescence staining for EGFP and CK8, a specific marker for luminal epithelial cells. As shown in Figure 3B, EGFP signals colocalized with CK8-positive cells, demonstrating that the transfected cells indeed corresponded to mammary epithelial cells. Notably, these EGFP signals were never observed in the untreated WT samples (Figure 3C). Furthermore, in the experimental samples, EGFP expression was discernible in the adipose tissues adjacent to the mammary ducts (Supplemental Figure S2B). However, this off-target expression was sporadic and spatially restricted to the adipocytes located in the immediate vicinity of the ducts. Unlike the robust and widespread expression in the epithelial cells, the signal from adipocytes was occasional, probably due to minor leakage of the plasmid solution into the area enriched with adipocytes. Alternatively, electric strength was too high to make the DNA-containing solution introduced intraductally deliver into the adipocyte-rich area. Finally, quantitative analysis demonstrated that transfection efficiency achieved by the MIGE method was estimated to be approximately 0.75%. In contrast, no GFP-positive cells were discernible in the WT control group (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical and quantitative analysis of EGFP expression in mammary epithelial cells. (A) Representative immunohistochemical images using DAB staining. The mammary duct from a WT control gland shows no EGFP signal (left). In the MIGE-treated gland, strong positive signal for EGFP (brown) are localized to the cytoplasm of the ductal epithelial cells (right). (B) Double immunofluorescence staining of the MIGE-treated mammary glands to identify the cells transfected. The portion successfully transfected with an EGFP expression vector is shown by green. Epithelial cells are also marked by staining with anti-CK8 (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The merge images demonstrate that the EGFP-positive area is also co-localized with CK8 (yellow arrowheads), indicating that cells showing successful transfection correspond to mammary epithelial cells. Notably, untransfected epithelial cells are only marked by anti-CK8 (white arrow). (C) Quantitative analysis of transfection efficiency performed using immunohistochemically stained samples. The percentage of EGFP-positive epithelial cells relative to the total number of epithelial cells was calculated by checking fluorescence between the MIGE-treated group and the WT control group. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

In this study, we established a novel, safe, and straightforward non-viral gene delivery method (termed MIGE) for transfection of the epithelial cells of murine mammary glands. This was achieved by intraductal injection of a solution using a breath-controlled glass capillary and subsequent in vivo EP of the surgically exposed mammary fat pad. Detection of EGFP-derived fluorescence and EGFP protein expression within the mammary gland tissue indicated successful gene delivery using MIGE.

A major advantage of MIGE is its excellent safety profile. In previous gene delivery experiments targeting the mammary glands, conventional viral vectors such as adenoviruses and lentiviruses have been employed [14,15]. The vectors were introduced via intraductal injection into the nipple. Viral vector-based gene delivery is highly efficient but has persistent safety concerns, such as insertional mutagenesis and strong immunogenicity, which can be significant confounding factors for experimental outcomes [16]. Nonviral approaches have been explored to circumvent these risks. For example, a method combining the piggyBac transposon system with EP was developed to introduce genes into mammary stem cells cultured in vitro. These genetically modified cells were transplanted into cleared fat pads to reconstitute functional mammary glands in vivo [17]. Although this approach is powerful and avoids virus-associated risks, the indirect multistep process is complex and time-consuming. Our MIGE system bypasses the risks associated with the use of viral vectors. This makes the MIGE system a particularly valuable tool in various fields such as breast cancer research and developmental biology, where unintended genetic alterations or immune responses can compromise the interpretation of results.

The use of a “breath-controlled glass capillary” for nucleic acid delivery to the mammary glands is unique. Conventional intraductal injection methods predominantly rely on the use of rigid metal needles, which may perforate the delicate ductal wall, making the procedure technically challenging and highly dependent on the operator’s skill [10]. In our system, the insertion of a flexible glass capillary into the nipple can be performed under observation using a dissecting microscope, and solution injection is finely maneuvered according to the operator’s breath pressure. While automated microinjection system can offer volume precision, in this study we employed a breath-controlled manual approach, because it allows to ensure accurate dosage by aspirating a pre-measured droplet into the capillary prior to injection. Moreover, the operator can pursue intraductal injection with real-time tactile feedback regarding intraductal pressure, which is beneficial for detecting subtle resistance changes and preventing the rupture of the delicate murine mammary ductal network. Although these operations vary slightly from person to person, they would minimize physical trauma to the duct. In other words, our innovation significantly lowers the risk of tissue damage, thereby simplifying the procedure and enhancing its reproducibility, which will make mammary gland studies more accessible for researchers. Notably, our intraductal injection procedure was successful in 100% of our attempts (23/23 mice), highlighting the reliability and reproducibility of this refined technique.

A key finding of this study was that surgical exposure of the mammary fat pad is essential for the success of MIGE. Our results showed that the non-surgical approach yielded extremely poor transfection efficiency (Figure 2a–c). This finding is consistent with the well-established principle that skin, particularly its outermost layer, the stratum corneum, possesses extremely high electrical resistance [18]. This high resistance barrier is a well-known challenge in transdermal drug delivery because it impedes effective current flow and prevents the electric field from reaching the underlying target tissues [19]. Over 99% of the body’s total electrical resistance is localized to the skin, which can exceed 100,000 Ω, whereas internal tissues have a resistance of only approximately 300 Ω [18]. This high resistance barrier impedes current flow to the underlying mammary tissues. We successfully bypassed this barrier by surgically incising the skin, allowing efficient and safe gene transfer at a much lower voltage (30 V) than that used for the non-surgical approach (70 V). This finding demonstrates that surgical exposure is a critical and necessary step for efficient in vivo EP-based gene delivery to the mammary glands.

The usefulness of MIGE was confirmed by detecting fluorescence within the mammary glands after the intraductal injection of fluorescent plasmid DNA (pCE-29) and subsequent in vivo EP (Figure 2d–i). These results were verified by performing immunohistochemical analysis using anti-GFP antibodies. The reactive products were predominantly and specifically localized in the mammary epithelial cells (Figure 3A,B). The variability in EGFP signal intensity observed among individual epithelial cells (Figure 3A,B) may be attributed to differences in the plasmid copy number taken up by each cell or the cell cycle status at the time of transfection. Furthermore, in a subset of samples, sporadic transgene expression was observed in a small number of adipocytes adjacent to the ducts (Supplemental Figure S2). This off-target expression pattern can be attributed to several factors. First, the injection pressure may have caused microperforations in the ductal wall, leading to a minor leakage of plasmid DNA into the stroma. Alternatively, the electric field applied during EP may have affected the adipocytes in close proximity to the ductal epithelium. Previous studies have demonstrated that adipocytes can be permeabilized and successfully transfected using EP [20]. Therefore, the electric field used in our MIGE procedure may have been sufficient to transiently permeabilize adjacent adipocytes, leading to the observed off-target expression. However, the EGFP expression in adipocytes was occasional and limited, with a majority of transfections occurring in the target epithelial population. Therefore, this observation does not detract from the overall efficacy and utility of MIGE for studying gene functions in the mammary epithelium.

Despite its advantages, MIGE has several limitations. The induced gene expression is transient, which may not be suitable for studies requiring long-term, stable gene modification. For such purposes, combining our delivery system with other systems such as genome editing tools could be a promising future direction. Additionally, although we observed robust EGFP expression, further quantitative analysis of transfection efficiency and assessment of expression uniformity throughout various tissues are warranted. Optimization of EP parameters, such as voltage and pulse conditions, may further enhance transfection efficiency and cell viability. There are potential risks associated with MIGE, including potential ductal rupture due to accidental deep puncture or by applying excessive pressure. Sudden or accidental death of individuals are also considered upon anesthesia and minor surgery as minor risks.

The potential applications of this technique are extensive. In basic research, it is a powerful tool for rapidly analyzing the functions of unknown genes involved in mammary gland development, differentiation, and homeostasis through overexpression or RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of those genes. The feasibility of applying MIGE for gene silencing is strongly supported by previous studies that have successfully used in vivo EP to deliver RNAi agents to other tissues [21]. Furthermore, MIGE can be used in the field of translational research; for example, breast cancer models can be established by using MIGE to introduce specific oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes into cells. Moreover, MIGE toward lactating mammary glands can be used for the study concerning milk protein production, although the presence of milk may physically impede plasmid-epithelium contact. MIGE is also useful as a tool to deliver therapeutic genes (or factors) directly to mammary tumors or oncogenes to generate breast cancer models in animals. MIGE is generally faster and simpler than conventional viral vector-based methods because viral vector preparation is a laborious and time-consuming process.

In conclusion, we developed a novel non-viral vector-based gene delivery method, termed MIGE-targeted murine mammary gland delivery, using breath-controlled capillary injection and subsequent in vivo EP. This method is safer and simpler than the conventional viral vector-based gene delivery systems. This technique has significant potential as a fundamental tool for advancing studies in a wide range of fields, from developmental biology to breast cancer research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010557/s1, Supplemental Figure S1. Histological assessment of tissue integrity in MIGE-treated mammary glands. Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of the murine mammary glands harvested 2 days after gene delivery. The images reveals well-preserved mammary tissue architecture, including intact ductal structures and surrounding adipose tissue. Notably, preservation of tissue architecture without significant inflammatory cell infiltration or tissue necrosis was observed, confirming the low cytotoxicity and safety of the MIGE method. Supplemental Figure S2. Occasional off-target expression of EGFP in adipocytes. (A) Whole-mount fluorescence image. Sporadic EGFP expression in adipocytes (arrows) near a transfected duct was seen (a–c). Bar = 1 mm. (B) Immunohistochemical staining using anti-GFP antibody. This staining shows EGFP protein expression in adipocytes (a). Bar = 100 µm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.M., M.S. and S.N.; methodology: K.M. and M.O.; validation: K.M., M.S. and S.N.; investigation: K.M., M.S. and S.N.; writing—original draft preparation: K.M., M.S. and S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers: 23KJ2200 to K.M. and 23K27097 to S.N.). The APC was funded by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number: 23KJ2200).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Jin, Q.; Liu, X.; Duan, H.; Feng, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Global burden of female breast cancer: New estimates in 2022, temporal trend and future projections up to 2050 based on the latest release from GLOBOCAN. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2025, 5, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Center Japan. Cancer Information Service. Available online: https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/data/dl/en.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Medina, D. The mammary gland: A unique organ for the study of development and tumorigenesis. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 1996, 1, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Wei, W.; Yu, L.; Ye, Z.; Huang, F.; Zhang, L.; Hu, S.; Cai, C. Mammary Development and Breast Cancer: A Notch Perspective. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2021, 26, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, M.E.; Das, S.K.; Emdad, L.; Windle, J.J.; Wang, X.Y.; Sarkar, D.; Fisher, P.B. Genetically engineered mice as experimental tools to dissect the critical events in breast cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2014, 121, 331–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hadsell, D.L. Genetic manipulation of mammary gland development and lactation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2004, 554, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bu, W.; Li, Y. Intraductal Injection of Lentivirus Vectors for Stably Introducing Genes into Rat Mammary Epithelial Cells In Vivo. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2020, 25, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somiari, S.; Glasspool-Malone, J.; Drabick, J.J.; Gilbert, R.A.; Heller, R.; Jaroszeski, M.J.; Malone, R.W. Theory and in vivo application of electroporative gene delivery. Mol. Ther. 2000, 2, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, H.; Heller, R. Transfection by Electroporation. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2018, 121, 9.3.1–9.3.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, S.; Brock, A.; Ingber, D.E. Intraductal injection for localized drug delivery to the mouse mammary gland. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 80, 50692. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M.; Ishikawa, A.; Kimura, M. Direct injection of foreign DNA into mouse testis as a possible in vivo gene transfer system via epididymal spermatozoa. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2002, 61, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, S.; Takagi, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Kurosawa, T. Effect of three types of mixed anesthetic agents alternate to ketamine in mice. Exp. Anim. 2011, 60, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landua, J.D.; Visbal, A.P.; Lewis, M.T. Methods for preparing fluorescent and neutral red-stained whole mounts of mouse mammary glands. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2009, 14, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, W.; Li, Y. In Vivo Gene Delivery into Mouse Mammary Epithelial Cells Through Mammary Intraductal Injection. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, 192, e64718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, S.; Thresher, R.; Bland, R.; Laible, G. Adeno-associated-virus-mediated transduction of the mammary gland enables sustained production of recombinant proteins in milk. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirley, J.L.; de Jong, Y.P.; Terhorst, C.; Herzog, R.W. Immune Responses to Viral Gene Therapy Vectors. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagaya, H.; Ishikawa, K.; Hosokawa, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Ueoka, Y.; Shimada, M.; Ohashi, Y.; Mikami, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Ihara, T.; et al. A method of producing genetically manipulated mouse mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, R.M.; Geddes, L.A. Conduction of electrical current to and through the human body: A review. Eplasty 2009, 9, e44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Dai, H.; Zhang, B. A Study of the Effects of Electroporation on Skin in an In-Vivo Mouse Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Computational Modeling, Simulation and Data Analysis, Hangzhou, China, 6–8 December 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 825–829. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M.; Saitoh, I.; Kiyokawa, Y.; Akasaka, E.; Nakamura, S.; Watanabe, S.; Inada, E. Electroporation-Based Non-Viral Gene Delivery to Adipose Tissue in Mice. OBM Genet. 2022, 6, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, K.E.; Chan, A.; Lin, F.; Shen, X.; Kichaev, G.; Khan, A.S.; Aubin, J.; Zimmermann, T.S.; Sardesai, N.Y. Optimized in vivo transfer of small interfering RNA targeting dermal tissue using in vivo surface electroporation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2012, 1, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.