Abstract

The present study provides a comprehensive comparative evaluation of three Greek fig cultivars through integrated instrumental, computational, and chemometric approaches. Fresh fig peel and flesh samples were analyzed to determine total soluble solids, total phenolic and flavonoid content, as well as antioxidant and antiradical activities, complemented by attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy for structural profiling. Significant varietal and tissue-dependent differences were observed, with fig peel exhibiting higher levels of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity compared to flesh. ATR-FTIR spectral patterns revealed the presence of characteristic functional groups associated with carbohydrates, phenolic compounds, carboxylic acids, and volatile compounds, reflecting the influence of variety, pollination requirements, and geographical origin. In parallel, to explore potential neuroprotective relevance, 30 phytochemicals reported in figs were subjected to molecular docking against human β-secretase 1 (hBACE1), a key enzyme in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis. Phenolic acids and flavonoids displayed favorable binding affinities and interaction profiles with the catalytic Asp32–Asp228 dyad and with the flap domain. A machine learning model (XGBoost) trained on known BACE1 inhibitors further classified all examined fig metabolites as active candidates. Collectively, these findings highlight Greek figs as chemically rich fruits with potential biological properties, supporting future targeted studies on their bioactive potential.

1. Introduction

Figs (Ficus carica L.), which belong to the Moraceae family, are among the oldest varieties of cultivated plants, with a history dating back more than 6000 years. They originate from the Middle East and Southwest Asia and were first domesticated in the Eastern Mediterranean. They are widely cultivated in the Mediterranean and the Near East, as well as in other countries with warm, dry climates. There are four main types of fig trees (caprifig, Smyrna, common, and San Pedro), which include more than 800 varieties cultivated in over 50 countries. Global production amounts to around 1.1 million tonnes per year, with Turkey producing the most (350,000 tonnes in 2022), followed by Egypt and Algeria [1,2,3,4].

Figs can be consumed fresh or dried, or processed into various products such as sweets, jams, baked goods, and sauces. They are characterized by high sugar content, low levels of organic acids, and a variety of pigments, which give them their different colors. They are also an important source of nutrients, including carbohydrates, fibers, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Their nutritional value and long history of cultivation make them a key component of the Mediterranean diet and agri-food economy [2,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Figs and other parts of the Ficus carica L. plant, such as the leaves, stem, bark, and roots, contain a variety of phytochemicals, including phenolic compounds, carotenoids, tocopherols, organic acids, triterpenoids (such as phytosterols), alkaloids, and volatile compounds. Phenolic compounds include acids, flavonoids, and coumarins, while carotenoids are divided into carotenes and xanthophylls [3,4,11,12,13,14]. Malic, citric, oxalic, quinic, ascorbic, shikimic, fumaric, and succinic acids are among the particular organic acids present in fig fruits [9,15,16]. Figs possess notable antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, anticancer, cardioprotective, and neuroprotective activities due to their bioactive constituents [2,17,18]. It is interesting to note that dietary supplementation of figs may be useful in improving cognitive and behavioral deficits in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [19,20]. Moreover, the main sugars found in figs are glucose and fructose, present in a ratio of approximately 43:56. Trehalose and sucrose have also been reported. Due to its higher relative sweetness, fructose contributes more to the perceived sweet taste. Brown and purple figs have higher concentrations of fructose, glucose, and sucrose than other color groups. The sugar content changes during ripening, with significant increases in glucose and fructose. Dried figs also have higher sugar levels than fresh figs [2,8,16,21].

The phytochemical composition and quality characteristics of figs are influenced by a variety of factors, including genotype/variety, fruit color, the part of the plant (skin or flesh), stage of ripeness, pollination requirements, crop type, time of harvest, geographical origin, climatic conditions, cultivation practices, and processing. Dark-skinned varieties have higher levels of polyphenols, particularly anthocyanins, and the skin has a higher nutritional value than the flesh. Multifactorial studies have demonstrated significant quantitative and qualitative variations in phenolic compound levels among different varieties and regions (e.g., Italy, Turkey, and Greece). At the same time, sugar composition varies depending on climatic conditions, cultivation practices, and harvest time [3,4,22,23].

In Greece, the Vasilika (or Royal) fig variety has received Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status alongside the Mavra/Black Markopoulou variety, and both are cultivated in Markopoulo. The Vasilika and Mavra Markopoulou varieties are classified as a Smyrna type, which requires pollination (caprification); in contrast, the Mission cultivar is a common fig that can grow with or without pollination [13]. Pollinated fig varieties usually exhibit larger sizes and higher phenolic content [24].

In addition to the nutritional and antioxidant values, the interest in fig phytochemicals has been extended to the possible neuroprotective effect [19]. The AD is directly linked with an abnormal production of b-amyloid peptides, which are mainly produced through the activity of β-secretase 1 (BACE1), the rate-limiting enzyme that initiates the amyloidogenic cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. BACE1 has consequently become a critical therapeutic target, and a number of groups of natural phenolic compounds, mainly flavonoids and phenolic acids, which are readily found in figs, have been documented to show inhibitory activity toward this enzyme. Given the highly diverse phenolic profile of the Greek fig varieties and the scarcity of information about their potential interaction with BACE1, the combination of molecular docking and machine learning prediction is helpful in understanding their potential bioactivity.

Taking all of the above literature findings into consideration, this study primarily aimed to conduct a comparative study of the Vasilika (Royal), Mavra/Black Markopoulou and Mission fig varieties in terms of variety, peel color, geographical origin, and the fruit parts (peel and flesh). This was achieved through the assessment of attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy data, Brix values, and spectrophotometric results for total phenolic and flavonoid content, and antioxidant and antiradical activity. Furthermore, molecular docking studies were conducted on the phytochemicals most commonly reported in the literature as constituents of fig peel and flesh, in order to explore, at a hypothesis-generating level, their potential relevance to neuroprotective targets, specifically the β-secretase 1 (BACE1), an enzyme, implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fig Sampling

This research examined three varieties of fig: Vasilika (Royal), Mavra Markopoulou, and Mission. More specifically, the samples investigated included green Vasilika figs from Markopoulo, black Mavra Markopoulou figs, and green Mission figs from two different regions in Greece: Markopoulo and Laconia. Table 1 shows the cultivation region, cultivar, and peel color of the figs, as well as the sample codes. A total of 5.0 kg of fresh samples from each category of figs (Ficus carica L.), harvested during August and September 2024 and 2025, were procured from vegetable markets in Markopoulo and Laconia. The fig samples were promptly transported to the laboratory to prevent degradation and to guarantee precise and representative findings, and they were analyzed right away thereafter. Twenty (20) individual fig samples were randomly picked for each fig category and per year, in each experiment. The figs were peeled by hand and used fresh for the experiments.

Table 1.

Coding information for fig samples.

2.2. Total Soluble Solids (TSS) Determination of the Fig Flesh

The total soluble solids (TSS) of the fig flesh samples were determined using a Kern Optics Analogue Brix refractometer (model ORA 80BB, manufactured by KERN & SOHN GmbH in Balingen, Germany). Following a method similar to that described by Ladika et al. (2024) [25], approximately 2 g of fresh fig flesh was homogenized, and a representative aliquot of the resulting juice was applied to the prism of the refractometer. The TSS, expressed in degrees Brix (°Brix) as shown in Table 2, were determined from direct refractometer readings.

Table 2.

Total soluble solids, total phenolic content, and antioxidant and antiradical activity of the peel and flesh of fig samples.

2.3. Extraction and Spectrophotometric Evaluation of Phenolic Compounds of Fig Peel and Flesh

Approximately 3 g of fig peel or flesh was diluted in 80% (v/v) aqueous methanol with a sample-to-solvent ratio of 1:10 (w/v). The mixtures were left at room temperature for 24 h. This time was determined from preliminary experiments and is mainly based on corresponding studies by our research team on many different plant tissues [25,26,27,28]. Mass transfer from the sample to the solvent is time-dependent. Increasing the duration generally increases the amount of target compound (solute) recovered until a certain point. Therefore, the extraction duration was selected based on prior literature on fruit matrices and phenolic recovery, aiming to ensure exhaustive extraction under mild conditions. Then, the extracts were filtered using a Buchner funnel and diluted with 80% (v/v) aqueous methanol to a final volume of 30.00 mL. After that, the filtrates were stored at 4 °C for spectrophotometric measurements, which were performed twice using a Spectro 23 Digital Spectrophotometer (Labomed, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA).

The total phenolic content (TPC) of the fig peel and flesh extracts was determined using a modified Folin–Ciocalteu micromethod, and the absorbance measurements were performed at 750 nm [29]. The total flavonoid content (TFC) of the fig peel and flesh extracts was measured at 415 nm according to the method described by Matić et al. (2017) [30]. The antiradical and antioxidant activities of the fig peel and flesh extracts were determined using ABTS•+ and FRAP assays adapted to microscale [31,32], respectively. Absorbance measurements were performed at 734 nm for ABTS•+ assay and at 595 nm for FRAP assay [31,32]. The TPC, TFC, and antiradical and antioxidant activity results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) using standard solutions with a range of 20–500 mg·L−1, mg of quercetin equivalents (QE) using standard solutions with a range of 5–500 mg·L−1, and mg of Trolox Equivalents (TE) with a concentration range of 0.20–1.5 mM and mg of Fe (II) using concentrations between 600 and 2000 μM of FeSO4·7H2O stock solution, respectively. The results were expressed as mg of standard solutions per g of fig peel or fig flesh.

All reagents, standards, and solvents were used as previously described [29,30,31,32]. For the TFC assay, chemicals including sodium hydroxide (NaOH) pellets (≥98%), NaNO2 (≥99.0%), anhydrous AlCl3 (≥99.0%), and quercetin standard (≥95%) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (Sigma-Aldrich Company, Gillingham, Dorset, UK).

2.4. Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

Attenuated total reflectance–Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) was conducted using a Shimadzu IRAffinity-1S FTIR spectrometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), which was fitted with a diamond internal reflection element (IRE). Samples of fig peel and flesh were applied directly to the ATR crystal for spectral recording in accordance with the method described by Christodoulou et al. (2024) [27]. The LabSolutions IR program (version 2.21) was used to carry out ATR correction, smoothing, normalization, and peak identification on the FTIR spectra of the fig samples.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The results of the total soluble solids measurement and ATR-FTIR spectroscopy in the fig samples, as well as the spectrophotometric assays in phenolic extracts, were analyzed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0, Chicago, IL, USA). The analysis was performed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test and post hoc analysis at a significance level of p < 0.05.

2.6. Molecular Docking

2.6.1. Collection and Preparation of the Phytochemical Dataset Derived from Ficus carica L.

A total of 30 phytochemicals previously reported in figs (Ficus carica L.) were selected for molecular docking studies based on quantitative evidence from the literature. The dataset covered a broad structural diversity, including phenolic compounds (phenolic acids, hydroxybenzoic acids, and flavonoids), coumarins, and alkaloids. The molecular structures of the examined set of compounds were initially sketched in 2D format (.SMILES) and prepared using AutoDockTools-1.5.7 software (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA). Specifically, polar hydrogens and Gasteiger charges were added, and finally the prepared structures were converted into PDBQT. files.

2.6.2. Beta-Secretase 1 (BACE1) Enzyme Preparation

The crystallographic structure of human β-secretase 1 (hBACE1) enzyme was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6EJ3, Resolution: 1.94 Å) and prepared by applying the AutoDockTools-1.5.7 software (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA). All crystallographic water molecules located more than 5 Å from the co-crystallized ligand were removed, whereas the conserved water molecule located in the catalytic pocket was retained. Missing residues, polar hydrogen atoms, and partial charges (Kollman charges) were then added to the structure to ensure proper electrostatic interactions.

2.6.3. Grid Box Generation and Molecular Docking Simulations

The resulting prepared enzyme was subsequently used for grid box generation and validation. Particularly, a grid box was defined by the coordinates of the co-crystallized ligand, including the following dimensions x = −18.31 Å, y = −38.98 Å, and −8.43 Å. To ensure the reliability of the docking protocol, the co-crystallized ligand was redocked by applying AutoDock Vina software (version 1.2.0). Redocking accuracy was evaluated by calculating the heavy-atom root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the predicted pose and the experimental crystallographic binding mode. The RMSD value confirms the docking procedure. Finally, all ligands from the curated Ficus carica L. dataset were docked into the prepared hBACE1 receptor grid. For each ligand, up to 10 poses were generated, and the highest-ranked pose according to the binding affinity was retained for analysis. Post-docking minimization was applied to refine ligand placement and optimize interactions with key residues such as Asp32, Asp228, Tyr71, and the flap region. The resulting top-scoring poses were used for subsequent interaction profiling and comparative evaluation across phytochemical classes.

2.7. Establishment of a Machine Learning Model Predicting the Inhibitory Activity of Fig Compounds

The machine learning process followed the methodology outlined by Ladika et al. (2025) [33] in the prediction of NOX2 inhibitors, which included dataset creation, generation of descriptors, feature selection, classifier development, and validation of the model. This computational pipeline was reused in BACE1, but with only minor changes to fit the different molecular data and the descriptors that were unique to the current study.

In short, experimentally reported BACE1 inhibitors were filtered out of the ChEMBL database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/explore/target/CHEMBL4822), (accessed on 6 October 2025) and categorized as active or inactive according to standard IC50 values. The computation of molecular descriptors was done with RDKit (https://www.rdkit.org/, Release_2025.09.2) (accessed on 6 October 2025) and the feature selection was done after the procedure of Ladika et al. (2025) [33] to rank the descriptors after repeated cycles of feature importance with multiple classifiers. Supervised algorithm development was performed using repeated 5-fold cross-validation of the algorithms, and the resulting optimized model was used to classify the phytochemicals identified in the figs. Final deployment of the model was done using the same workflow as established in the NOX2 publication and is thus not repeated here.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Total Soluble Solids (TSS) and Spectrophotometric Results of the Fig Samples

3.1.1. Total Soluble Solids (TSS) Results

The fig flesh was assessed for total soluble solids (TSS) values, and the results are presented in Table 2. As anticipated due to their sweetness, Vasilika and Mavra Markopoulou figs exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher levels of total soluble solids (TSS) than the Mission variety. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the Brix values between Vasilika and Mavra Markopoulou figs or in the Brix levels of Mission figs grown in the two regions.

The Brix values found in the present study, particularly for the Vasilika and Mavra Markopoulou figs, were higher than those reported by Luo et al. (2025) [34], who reported values ranging from 13.8 to 19.6 °Brix for six Ficus carica cultivars from Shandong Province, China; by Hoxha et al. (2022) [35] for the Shëngjin and Kraps fig varieties (black and white) collected in Tirana, with reported TSS ranging from 12 to 15 °Brix at the ripe stage; by Swetha et al. (2022) [36] for figs grown in the Arid Zone Fruit Block, in Coimbatore, with values ranging from 16.96 to 21.65 °Brix; and by Hssaini et al. (2019) [37] for 94 Moroccan local clones and 41 imported varieties, with values ranging from 10.51 to 13.93 °Brix. Furthermore, the Brix values of the present study were similar to those reported by Tikent et al. (2025) [21] for fresh figs from Eastern Morocco; by Galán et al. (2025) [38] for the San Antonio and Dalmatie fig varieties from Spain; by Gündeşli et al. (2024) [39] for 19 fig genotypes from the Eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey; by Hoxha et al. (2022) [40] for different native Albanian fig varieties; by Garza-Alonso et al. (2020) [41] for Adriatic fig cultivar; by Sedaghat and Rahemi (2018) [9] for an Iranian fig cultivar; and by Pereira et al. (2017; 2020) [10,42] for Spanish fig varieties. Finally, the Brix values obtained in the present study were lower than those of the Albacor (24.97 ± 3.13 °Brix) and De Rey (24.78 ± 1.47 °Brix) fig varieties from Spain [38], and those of a cultivar located in Torres Novas, Portugal [43].

The total soluble solids (TSS) and sugar content of figs are influenced by several factors such as ripeness, post-harvest processing, and variety. It has been observed that the levels of glucose and fructose increase progressively during fruit development [42,44]. Comparative studies have shown that under the same cultivation and environmental conditions, variations in sugar levels are primarily due to the genotype and biochemical characteristics of the ecotypes [45,46]. Additionally, brown and purple varieties have higher fructose, glucose, and sucrose concentrations than other colors [47].

3.1.2. Spectrophotometric Results

Furthermore, the fig peel and flesh were evaluated for total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and antiradical and antioxidant activity, the results of which are presented in Table 2.

The most interesting finding was that the extracts from fig peel exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher levels of TPC, TFC, and antiradical and antioxidant activity compared to fig flesh. Furthermore, the Markopoulo mavra fig peel extracts presented the highest (p < 0.05) TPC, TFC, and antiradical and antioxidant activity, whereas the Laconia Mission peel extracts presented the lowest. Specifically, the TPC and the antioxidant activity expressed as reducing power of the examined peel extracts decreased in the following order: Markopoulo mavra peel > Markopoulo vasilika green peel > Markopoulo mission peel > Laconia mission peel. Regarding TFC and antiradical activity expressed as radical-scavenging capacity, the Markopoulo Vasilika green peel and Markopoulo Mission peel extracts showed intermediate values with no significant (p > 0.05) difference between them. Unlike the findings regarding fig peel extracts, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed in terms of TPC, TFC, and antiradical and antioxidant activity in most fig flesh extracts.

Once all of the above results had been statistically processed, very strong positive Spearman ’s correlations (p < 0.05) were found between TPC and antiradical activity (rs = 0.9524), TPC and antioxidant activity (rs = 0.9172), TPC and TFC (rs = 0.9345), as well as antiradical activity and TFC (rs = 0.9487). Moreover, high positive Spearman’s correlations (p < 0.05) were found between antioxidant and antiradical activity (rs = 0.8547) and antioxidant activity and TFC (rs = 0.7799). This finding suggests that phenolic compounds play a substantial role in the reducing power and radical-scavenging capacity of fig extracts.

The literature shows that the primary factors influencing the composition of bioactive compounds in figs that exhibit antiradical and antioxidant activity are the cultivar, the color of the outer peel, the pollination process, and the stage of ripening. It has been revealed by various investigations that the phenolic compound content in figs of different cultivars and peel colors varies. Dark-skinned cultivars have been found to contain higher quantities of these compounds, which means that they exhibit greater antioxidant activity than their light-skinned counterparts [4,37,48]. Furthermore, research comparing the peels and flesh of figs has indicated that the peels have a higher phenolic content and greater antioxidant and antiradical activity than the flesh [8,16,23,49,50]. This finding is corroborated by the current investigation, which found that the TPC values for the peel samples were higher than those for the flesh samples. Conversely, fertilized figs have been found to contain higher concentrations of phenolic compounds in both the peel and flesh, in contrast to unfertilized figs [23,51]. It is important to note that Vasilika and Mavra Markopoulou figs belong to the Smyrna type, which is dependent on pollination. This may also explain their higher total phenolic content. Furthermore, it has been revealed that the phenolic content of figs varies depending on environmental conditions [4,23]. This fact could provide an explanation for the different TPC results obtained from the Mission cultivar grown in Markopoulo and Laconia, two regions of Greece with rather distinct climates. Some studies have suggested that the total phenolic content decreases as ripening progresses [35,39]. However, other researchers have claimed that TPC levels fluctuate during ripening, initially decreasing before increasing again [9], while others have suggested that the ripening stage does not affect TPC levels [13].

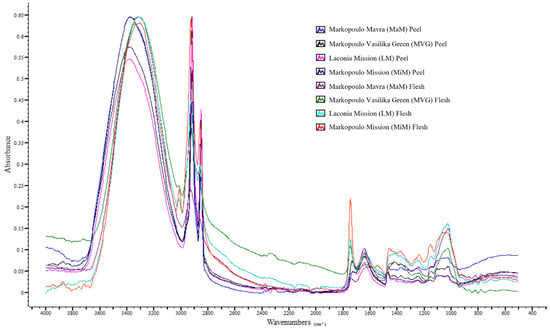

3.2. Interpretation of the ATR-FTIR Spectral Absorbance Bands of the Fig Peel and Flesh Samples

Analyzing the ATR-FTIR spectra of fig peel and flesh samples can reveal significant information about their functional groups and chemical composition. Table 3 shows the mean intensity of the ATR-FTIR spectral absorbance peaks in the peel and flesh of the studied figs. The absorption band at 3630 cm−1, which is mainly attributed to the hydroxyl group of phenols [52], was observed only in the flesh of Markopoulo Vasilika Green and Markopoulo Mission figs. The absorption band at 3300 cm−1, which is associated with O-H stretching vibrations in cellulose and dietary fibers [15], was found in all peel and flesh samples. Markopoulo Mavra and Markopoulo Vasilika Green figs exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher intensities than Mission figs. According to Trad et al. (2014) [51], pollination of figs has been demonstrated to enhance the methylation degree of dietary fibers (predominantly pectins), thereby augmenting their chemical and enzymatic stability. Therefore, Markopoulo Mavra and Vasilika figs, which require pollination, may yield dietary fibers that are slightly less fermentable and more resistant, resulting in higher intensities at 3300 cm−1 compared to Mission figs. Furthermore, the flesh of the Mission figs showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher intensities than their peels. The bands at 2922 and 2855 cm−1, which are associated with the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibration of C-H, in CH2 and CH3 groups of terpenes, carbohydrates, carboxylic acids, or free amino acids, respectively [15,25,53], displayed significantly (p < 0.05) higher intensities in the peel samples than in the flesh samples. In line with this finding, Teruel-Andreu et al. (2024) [18] reported that fig peel contains a significantly higher concentration of volatile compounds, such as terpenes, than the flesh. The absorption band at 1735–1728 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching vibration of the ester carbonyl group [25,53] and exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher intensities in the flesh samples than in the peel samples, except for Markopoulo Mavra. Of particular interest were the findings relating to absorption at 1637–1627 cm−1, which is associated with the bending vibration of N-H and the stretching vibration of the C-N bonds of amide I [15], as well as the stretching vibration of the phenolic ring [52]. Specifically, the peels of Markopoulo Mavra and Markopoulo Vasilika green figs gave almost double the intensity of the flesh, whereas the intensities of the peels and flesh of Mission figs did not differ significantly. Given that the amide Ι peak is related to protein content, the results support that the protein profile and content of figs is impacted by their variety, cultivation conditions, and ripeness [21]. Absorption at 1454 cm−1 was mainly found in the peel samples, except for the Markopoulo Mission figs, where it was also found in the flesh. This absorption is attributed to bending vibrations of C-H bonds in lipids and proteins [52], or to scissoring vibrations of CH2 in cutin, waxes, and polysaccharides [26,27]. The band at 1411 cm−1 was found in all peel and flesh samples, except Mission peels from Laconia. As Hssaini et al. (2021) [15] noted, the weak peak at 1414 cm−1 shows the N-H bending vibration and the C-N stretching vibration of amide II, as well as the deformation of C-H in CH2 and CH3.

Table 3.

Mean intensities of the ATR-FTIR spectral absorbance bands of the peel and flesh of the fig samples.

The band at 1369–1373 cm−1 arising from either the C-H bending vibrations of CH3 in carboxylic and amino acids, polysaccharides, and chlorophylls or the in-plane O-H bending vibrations in phenolic compounds [27,53] was found in all peel and flesh samples, with the flesh of the figs exhibiting a significantly (p < 0.05) higher intensity than the peels. Furthermore, no statistical difference was found between Markopoulo Vasilika Green and Markopoulo Mavra figs or between Mission figs from different regions, although the former exceeded the latter in terms of absorption intensity. Moreover, the flesh of Markopoulo Vasilika Green and Markopoulo Mavra figs was superior to the other flesh samples. The band at 1315 cm−1 was exclusively detected in fig peel samples and is related to O-H in-plane bending vibrations in flavonoids and phenolic acids [27,53]. The findings regarding the absorption of the ether group of carbohydrates and phenolics at 1246, 1143, 1100, 1074, 1056–1050, and 1028–1022 cm−1 [27,28] are of great interest. Specifically, absorption was only observed in the peel samples at the bands 1100 and 1074 cm−1, while the fig flesh exhibited multiple intensities compared to the peel at the band 1028–1022 cm−1. This result, combined with the high positive Spearman’s correlation (p < 0.05) between total soluble solids and the intensities at 1028–1022 cm−1 (rs = 0.7348), indicates the sweetness of fig flesh. The absorptions at 920 cm−1 (bending vibrations of glycosidic linkage), at 866 and 818 cm−1 (a-configuration anomeric vibration), and at 775 cm−1 (bending vibrations of ortho-substituted aromatic rings) [28,52] were only detected in the fig flesh samples, and in most cases, their intensities varied insignificantly. Therefore, these absorptions could be considered indicative of fig flesh. The band at 721 cm−1, which is associated with cis-C-H out-of-plane bending vibrations [28,52], could be attributed to phytochemicals such as coumarins and phenolic acids [22]. Finally, the bands at 630–623 and 518–514 cm−1, which are related to the out-of-plane O-H and to in-plane C-O-C bending of phenolic glucosides, respectively [28,52], were found in almost all peel and flesh samples, with a higher intensity observed in the latter. The ATR-FTIR spectral overlay of fig peels and flesh is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

ATR-FTIR spectral overlay of fig peels and flesh.

3.3. Molecular Docking Results for Figs’ Principal Compounds Against Beta Secretase 1 Enzyme

Molecular docking analysis was carried out to evaluate the binding affinity and potential inhibitory activity of 30 fig-derived phenolics, flavonoids, and coumarins [4,14,48] against human β-secretase 1 (hBACE1), a key enzyme involved in amyloid-β peptide production [54]. The β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide is the major constituent of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain and is likely to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of this devastating neurodegenerative disorder. The β-secretase, β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme (BACE1; also called Asp2, memapsin 2), is the enzyme responsible for initiating Aβ generation [55,56]. Thus, BACE1 is a prime drug target for the therapeutic inhibition of Aβ production in AD.

In the applied docking protocol, a semi-open conformation of hBACE1 (PDB ID: 6EJ3, Resolution: 1.94 Å) was selected in an effort to identify compounds that are capable of forming stable interactions regardless of the flap-loop dynamics. The results’ evaluation was based on their binding affinity values compared to the native ligand (Binding affinity = −11.7 kcal·mol−1) and also to their interaction profiles. The interaction patterns of the top-ranking compounds (Table 4) indicate that several structural classes of phenolics (phenolic acids, coumarins, flavonoids, and hydroxybenzoic acids) formed hydrogen bonds and aromatic contacts with key residues surrounding the catalytic dyad (Asp32 and Asp228). In particular, the results’ evaluation showed that caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, quinic acid, isopsoralen, kaempferol, myricetin, naringin, quercetin, rutin, protocatechuic acid, salicylic acid, and ellagic acid are characterized as the most promising candidates.

Table 4.

Binding affinity values and interaction pattern of the examined compounds.

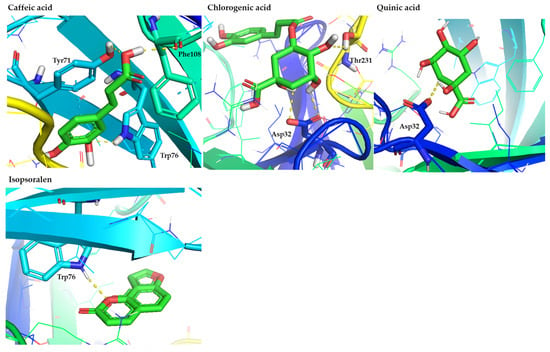

Among phenolic acids, caffeic, chlorogenic, and quinic acids presented notable binding features. In particular, caffeic acid formed hydrogen bonds and π-π interaction with Tyr71, and hydrogen bond with Trp76, suggesting favorable anchoring under the flap loop. Also, caffeic acid interacts via the formation of a hydrogen bond with Phe108, which belongs to the hydrophobic pocket of the enzyme. In contrast, chlorogenic acid displayed a more classical binding mode through the formation of hydrogen bonds with Asp32 and Thr231, consistent with well-known catalytic-site inhibitors [57,58]. Quinic acid engaged only Asp32, but still ranked among the promising compounds, reflecting its ability to position its hydroxyl groups toward the dyad.

Within the coumarin class, isopsoralen indicated moderate predicted affinity and formed a hydrogen bond with Trp76, demonstrating that even minimally substituted coumarins can orient into the flap region. Consistent with our computational results, recent in vitro studies have reported that naturally occurring coumarins act as mild BACE1 inhibitors, displaying measurable but weaker activity compared to polyhydroxylated flavonoids and phenolic acids [59].

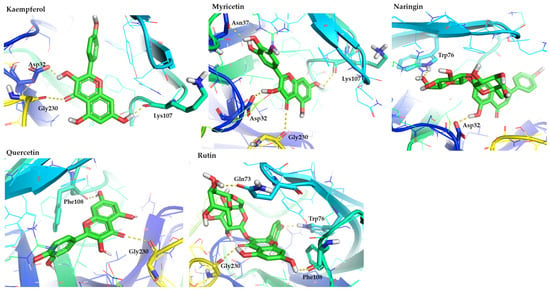

Flavonoids represent the most promising class, with several compounds displaying high binding affinity scores and rich interaction networks. Specifically, kaempferol, myricetin, naringin, quercetin, and rutin exhibited the most favorable interaction patterns. Kaempferol formed hydrogen bonds with Asp32, Lys107, and Gly230, directly targeting the catalytic dyad. Myricetin showed an extensive network involving Lys107, Gly230, Asn37, and Asp32, revealing its ability to bridge both the catalytic region and flap-proximal residues. Naringin and rutin, despite their bulkier glycosidic moieties, displayed strong interactions. Naringin bound Asp32 and Trp76, while rutin formed hydrogen bonds with Tyr14, Gln73, Trp76, and Phe108, indicating extensive surface recognition. The shared ability of flavonoids to establish hydrogen bonds with Asp32, π–π stacking with Tyr71/Trp76, and backbone interactions with Gly230 highlights their relevance as BACE1 inhibitors. The presence of multiple hydroxyl groups facilitates optimal complementarity with the polar and aromatic environment of the active site. This agrees with previous literature data indicating that the flavonol scaffold (e.g., quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol) is among the most potent natural chemotypes for BACE1 inhibition [60,61].

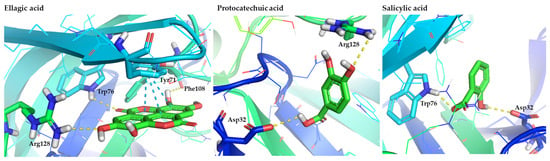

Among the hydroxybenzoic derivatives, ellagic acid showed one of the most complex interaction profiles, forming hydrogen bonds with Trp76, Arg128, and Phe108, in addition to π–π stacking with Tyr71. Its rigid, polycyclic structure appears to facilitate multi-residue recognition. Protocatechuic and salicylic acids formed simpler interactions—primarily with Asp32 and residues near the flap entry—but still scored within the promising range, consistent with their strong polarity and capacity for hydrogen bonding [62].

Representative binding poses of the most promising compounds within the BACE1 enzyme are depicted in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Representative binding poses of the most promising phenolic acids (caffeic, chlorogenic, and quinic acids) and coumarins (isopsoralen), contained in figs, in the hBACE1 enzyme. The figure is made using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (version 3.0, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA).

Figure 3.

Representative binding poses of the most promising flavonoids (kaempferol, myricetin, naringin, quercetin, and rutin), contained in figs, in the hBACE1 enzyme. The figure is made using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (version 3.0, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA).

Figure 4.

Representative binding poses of the most promising hydroxybenzoic acids (ellagic, protocatechuic, and salicylic acids), contained in figs, in the hBACE1 enzyme. The figure is made using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (version 3.0, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA).

Collectively, the experimental findings corroborate our computational observations and indicate that fig-derived phenolics and flavonoids fall within a well-established class of natural BACE1 inhibitors. This convergence of docking predictions and in vitro data provides strong justification for advancing the most promising compounds identified here into dedicated enzymatic inhibition assays to validate their activity and assess their potential neuroprotective relevance.

3.4. Machine Learning-Based Classification and Descriptor Analysis of BACE1 Potential Inhibitors

3.4.1. Descriptor Selection and Their Biochemical Relevance

Six descriptors were the most significant in predicting BACE1 inhibition; they included the number of hydrogen bond acceptors (NumHAcceptors), the number of rings (RingCount), the number of hydrogen bond donors (NumHDonors), the number of heteroatoms (NumHeteroatoms), the number of aromatic carbocycles (NumAromaticCarbocycles), and the maximum electronic state index (MaxEStateIndex) (Table 5). Their statistical significance and their importance values demonstrate a logical chemical rationale behind BACE1 inhibition, which is the important structural feature that the enzyme needs to interact well in its catalytic and allosteric pockets. The most significant descriptors appeared to be the NumHAcceptors (importance = 0.231), which signifies that the ability to form hydrogen bonds, specifically as a hydrogen-bond acceptor, is a dominant determinant of activity. This is consistent with the well-defined binding environment of BACE1, in which inhibitor scaffolds commonly develop stabilizing interactions with the catalytic Asp32-Asp228 dyad [57,63,64]. The second and the third most significant descriptors, RingCount and NumHDonors (importance = 0.173 each), indicate the significance of rigidity of the aromatic backbone and equal donation of hydrogen bonds. Aromatic ring systems are also believed to help in π-π stacking and hydrophobic anchoring to the deep active-site cleft of BACE1 [61,65], a feature that is common with most synthetic inhibitors, like hydroxyethylamines [66]. The interaction of donor groups is also an addition to acceptor interactions that aids in multi-point anchoring and stabilizing of the bound pose. NumHeteroatoms (importance = 0.154) is important because it modulating the polarity, electronic density, and interaction potential, and NumAromaticCarbocycles (importance = 0.135) captures the complexity of aromatic systems. Extended aromatic structure molecules have been shown to bind the flap region of BACE1, bind with Tyr71 and Trp76 [67,68,69,70], and increase the inhibitor potency. Lastly, there is MaxEStateIndex (importance = 0.135), which captures the index of a single atom with the highest number of electrons within the molecule. The significance of its importance implies that sites with a high degree of polarization or conjugation, as is the case with phenolic structures, are involved in the process of molecular recognition [71]. This is similar to the results of the machine learning analysis of the NOX2 enzyme, which also found electrotopological indices to be some of the most significant predictors of activity [33].

Table 5.

Selected descriptors along with their statistical significance and importance for classification.

The combination of the characteristics mentioned above forms a structural fingerprint characteristic of potential BACE1 inhibitors: polyphenolic, highly conjugated, hydrogen-bond-rich molecules that are capable of deep insertion into the active site.

3.4.2. Model Performance and Predictive Robustness

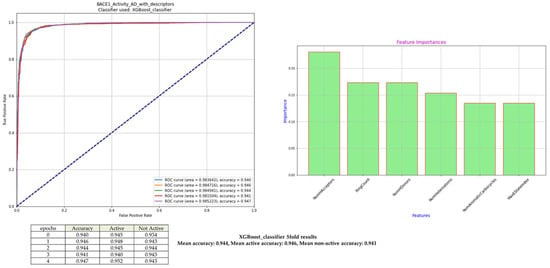

In the course of all repetition training periods, the XGBoost model demonstrated a remarkable predictive accuracy, a mean accuracy of 0.944, an active-class sensitivity of 0.946, and a non-active-class specificity of 0.941 (Figure 5). The small variance between epochs B (one complete pass of the entire training dataset through the model during training) shows that it is very stable and its vulnerability to random initializations or sample divisions is low, which is essential in biochemical classification problems, where data size is often scarce. The interpretation of the ML system is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Classification performance of XGBoost for BACE1 inhibition. Receiver Operative Curves (ROCs) associated with each of the five training epochs with persistent Area Under Curve (AUC) values attest to the excellent model performance, and the ROC curves reveal the model’s excellent discriminatory capability. Out of the six selected molecular descriptors, the feature-importance profile highlights NumHAcceptors, RingCount, and NumHDonors as the most impactful contributors to model performance.

These values can be compared to those achieved in our previous publications on ML models [26,33], which supports the validity of this standardized machine learning framework for another enzymatic target. The high-performance consistency also indicates that the chosen descriptors represent a chemically significant subset of features that describe the key structure–activity correlation that governs the action of BACE1 inhibition.

3.4.3. Classification of Fig Phytochemicals Using the Machine Learning Model

The optimized XGBoost model was then used to assess the ability of 12 phytochemical constituents that have already been found in figs and studied using molecular docking to predict their ability to inhibit BACE1. These metabolites include a structurally diverse group, including simple phenolic acids and hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives as well as more coumarins and flavonoids. Since the machine learning model was trained on normalized values of the descriptors, the significant assumption of the meaningful classification was that the features were properly normalized. All the compounds were always classified under the active group when the descriptors of the fig metabolites were normalized with the same scaling parameters used when training the model. This consistent result indicates the high structural complacency of fig-derived phenolic compounds with the pharmacophoric demands of the model, especially the high level of hydroxyl groups, high aromaticity, and high density of heteroatoms. Finally, we stated that the ML classification should be interpreted as a prioritization tool rather than definitive proof of inhibitory activity. Prediction of figs’ compounds by machine learning modeling is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Prediction of figs’ compounds by machine learning modeling.

3.4.4. Structural Explanation for the Universal Predicted Activity of Fig-Derived Compounds—Comparison with Molecular Docking Results

A uniform naming of all the fig-derived metabolites as active BACE1 inhibitors can be logically explained by analyzing the structural motifs shared that are consistent with the known molecular determinants of TheBACE1 inhibition. The convergent physicochemical properties seem to support the reported bioactivity of the assessed compounds across the board. In this regard, the uniform number of hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors that are found in these molecules are a result of the repetitive hydroxyl, carbonyl, and ether groups that define phenolic acids and flavonoids. These functional groups have been reported to mediate the widespread hydrogen-bonding with the Asp32 and Asp228 catalytic dyad of BACE1 and thus form a crucial precondition for inhibition binding. The rationale of the choice of the descriptor NumHAcceptors as the most predictive variable in the predictive model, and the assured placement of even structurally small molecules like caffeic or protocatechuic acids in the active category, is this mechanistic insight.

In addition to hydrogen-bonding capacity, the high ring count (RingCount) and the high number of aromatic carbocycles (NumAromaticCarbocycles) of the fig phytochemicals indicate the significance of aromaticity and structural rigidity to effect effective binding at the active site of the enzyme. The aromatic ring systems are involved in π-π stacking with residues in the flap region, particularly Tyr71 and Trp76, and are also part of hydrophobic anchoring in the deep catalytic cleft. Flavonoids like quercetin, kaempferol, and myricetin have longer conjugated systems that resemble structural motifs found in synthetic BACE1 inhibitors that provide a clear chemical explanation of the expected potency.

The dense heteroatomicity of the descriptor, as measured by the value with the name NumHeteroatoms, provides a diluted assortment of electron-giving and electron-taking centers to influence the polarity and electrostatic complementarity of the molecules. This feature is probably suitable for increasing the specificity of interaction with charged and polar residues that surround the active site. Simultaneously, the predictor, denoted as the descriptor MaxEStateIndex, which indicates the highly polarized environments of atoms, plays a major role in the model. Phenolic compounds usually contain highly electron-saturated oxygen-containing functional groups, which can stabilize ligand binding by directional hydrogen bonding as well as by noncovalent electrostatic forces.

Surprisingly, glycosylated flavonoids, including rutin and naringin, were also expected to be active despite their high steric bulk. This suggests that the underlying flavonoid aglycone was considered the main factor in the inhibitory potential, and glycosylation affected solubility and bioavailability and not the pharmacophoric backbone. Although, in certain instances, the large sugar remnants can obstruct binding, the maintained structures of aromatic rings, heteroatoms, and hydroxyl groups in their structural cores are aligned with already known BACE1 inhibitory models.

In total, the figure metabolite profile of the descriptors shows a high degree of conformity to the structural and electronic characteristics reported in potent BACE1 inhibitors. These strong hydrogen-bond networks, long aromatic, dense heteroatoms, and polarized electronic domains all play a role in a coherent pharmacophoric ensemble. This structural convergence gives a striking justification to the uniformity of the characterization of all the compounds examined as active and supports the speculation that figs contain a chemically diversified repertoire of molecules that have potential neuroprotective properties.

Although no direct enzymatic inhibition assays were performed, the present findings provide a chemically and structurally informed framework for prioritizing fig-derived compounds for future experimental validation. The integration of analytical characterization with in silico approaches supports hypothesis generation and guides subsequent targeted bioactivity studies.

4. Conclusions

This research presents a detailed evaluation of three Greek fig varieties—Vasilika (Royal), Mavra Markopoulou, and Mission—by combining compositional analysis, ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, and computational analysis of phytochemical bioactivity. It is worth noting that research interest in evaluating the Vasilika (Royal) and Mavra Markopoulou fig varieties has increased, given their designation as a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) and the limited extent of research in this area. The findings prove that the peel tissues, particularly those of the Mavra Markopoulou variety, have the highest amounts of total phenolics and flavonoids, and have stronger reducing power and greater radical-scavenging capacity. These results highlight the importance of cultivar, peel color, and pollination type in the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds in fruits, as well as the nutritional and functional value of dark and pollinated figs. Flesh samples, although compositionally different, contained lower bioactive contents compared to peel samples, which supports the protective and metabolically active properties of peel.

These observations were also supported by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy results, which showed typical absorbance bands that were related to carboxylic and amino acids, phenolic compounds, chlorophylls, polysaccharides, and volatile compounds. The spectral variation of the fig samples studied reflects the effect of the cultivar, geographical origin, and fig part.

In addition to physicochemical characterization, the study also utilized molecular docking and machine learning to investigate a possible interaction of fig-derived phytochemicals with β-secretase 1 (BACE1), which is an enzyme in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. A number of selected phenolic compounds, including caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, kaempferol, myricetin, quercetin, rutin, and naringin, showed good predicted binding capacity, indicating that fig metabolites have structural characteristics that could enable natural BACE1 inhibition. This trend was also confirmed by the machine learning model, which always identified all the studied compounds as possible BACE1 inhibitors.

Generally, the results demonstrated that Greek figs are chemically enriched fruits with great antioxidant properties and a promising phytochemical profile that can be applied in neuroprotective applications. The analytical and computational evidence synergistically supports the usefulness of these cultivars in nutritional studies and in the development of functional foods in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C., E.K., D.C. and V.J.S.; methodology, P.C., I.S., K.A., G.L. and E.K.; software, P.C., M.T., D.C. and E.K.; validation, P.C., D.C., E.K. and V.J.S.; formal analysis, I.S., K.A. and G.L.; investigation, P.C., I.S., K.A., G.L., D.C., E.K. and V.J.S.; resources, D.C., E.K. and V.J.S.; data curation, P.C., I.S., K.A., G.L. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C., I.S., E.K. and V.J.S.; writing—review and editing, P.C., K.A., G.L., D.C., E.K. and V.J.S.; visualization, P.C., K.A., D.C. and E.K.; supervision, D.C., E.K. and V.J.S.; project administration, V.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the “Food Innovation, Quality and Safety” MSc Program at the Department of Food Science and Technology, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece, for kindly providing the reagents and chemicals used for the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dogara, A.M.; Hama, H.A.; Ozdemir, D. Taxonomy, Traditional Uses and Biological Activity of Ficus carica L. (Moraceae): A Review. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.Y.; Alshaikhi, A.I.; Hazzazi, J.S.; Kurdi, J.R.; Ramadan, M.F. Recent Insight on Nutritional Value, Active Phytochemicals, and Health-Enhancing Characteristics of Fig (Ficus craica). Food Saf. Health 2024, 2, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, A.K.; Islam, M.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B. Phytochemical Composition and Health Benefits of Figs (Fresh and Dried): A Review of Literature from 2000 to 2022. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veberic, R.; Colaric, M.; Stampar, F. Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids of Fig Fruit (Ficus carica L.) in the Northern Mediterranean Region. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajam, T.A.; H, S. Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, Industrial and Traditional Uses of Fig (Ficus carica): A Review. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 368, 110237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W.; Cheng, Q. A Review of Chemical Constituents, Traditional and Modern Pharmacology of Fig (Ficus carica L.), a Super Fruit with Medical Astonishing Characteristics. Pol. J. Agron. 2021, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadhraoui, M.; Bagues, M.; Artés, F.; Ferchichi, A. Phytochemical Content, Antioxidant Potential, and Fatty Acid Composition of Dried Tunisian Fig (Ficus carica L.) Cultivars. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2019, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Khali, M.; Benkhaled, A.; Boucetta, I.; Dahmani, Y.; Attallah, Z.; Belbraouet, S. Fresh Figs (Ficus carica L.): Pomological Characteristics, Nutritional Value, and Phytochemical Properties. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2018, 83, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, S.; Rahemi, M. Effects of Physio-Chemical Changes during Fruit Development on Nutritional Quality of Fig (Ficus carica L. Var. ‘Sabz’) under Rain-Fed Condition. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 237, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; López Corrales, M.; Martín, A.; del Villalobos, M.C.; Córdoba, M.d.G.; Serradilla, M.J. Physicochemical and Nutritional Characterization of Brebas for Fresh Consumption from Nine Fig Varieties (Ficus carica L.) Grown in Extremadura (Spain). J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 6302109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, I.F.u.; Aziz, A.; Khalid, W.; Koraqi, H.; Siddiqui, S.A.; AL-Farga, A.; Lai, W.-F.; Ali, A. Industrial Application and Health Prospective of Fig (Ficus carica) By-Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walia, A.; Kumar, N.; Singh, R.; Kumar, H.; Kumar, V.; Kaushik, R.; Kumar, A.P. Bioactive Compounds in Ficus Fruits, Their Bioactivities, and Associated Health Benefits: A Review. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 6597092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karantzi, A.D.; Kafkaletou, M.; Christopoulos, M.V.; Tsantili, E. Peel Colour and Flesh Phenolic Compounds at Ripening Stages in Pollinated Commercial Varieties of Fig (Ficus carica L.) Fruit Grown in Southern Europe. Food Meas. 2021, 15, 2049–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, O.S.; Samaras, Y.; Gatidou, G.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Stasinakis, A.S. Review on Fresh and Dried Figs: Chemical Analysis and Occurrence of Phytochemical Compounds, Antioxidant Capacity and Health Effects. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hssaini, L.; Elfazazi, K.; Razouk, R.; Ouaabou, R.; Hernandez, F.; Hanine, H.; Charafi, J.; Houmanat, K.; Aboutayeb, R. Combined Effect of Cultivar and Peel Chromaticity on Figs’ Primary and Secondary Metabolites: Preliminary Study Using Biochemical and FTIR Fingerprinting Coupled to Chemometrics. Biology 2021, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, L.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Corrêa, R.C.G.; Pires, T.C.S.P.; Alves, M.J.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Nutritional, Chemical and Bioactive Profiles of Different Parts of a Portuguese Common Fig (Ficus carica L.) Variety. Food Res. Int. 2019, 126, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manik, M.M.; Quader, M.F.B.; Masum, M.A.A.; Iftekhar, A.B.; Rahman, S.A.; Sarker, M.S.; Hossain, D. Nutritional Composition, Bioactive Compounds, and Antioxidant Activity of Fig (Ficus carica L.) Jam Varieties: A Functional Food Perspective. Health Dyn. 2025, 2, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruel-Andreu, C.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Hernández, F.; Wojdyło, A. Bioactive Compounds (LC-PDA-Qtof-ESI-MS and UPLC-PDA-FL) and in Vitro Inhibit α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase in Leaves and Fruit from Different Varieties of Ficus carica L. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 141977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash, S.; Essa, M.M.; Braidy, N.; Al-Jabri, A.; Vaishnav, R.; Al-Adawi, S.; Al-Asmi, A.; Guillemin, G.J. Consumption of Fig Fruits Grown in Oman Can Improve Memory, Anxiety, and Learning Skills in a Transgenic Mice Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutr. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, M.M.; Subash, S.; Akbar, M.; Al-Adawi, S.; Guillemin, G.J. Long-Term Dietary Supplementation of Pomegranates, Figs and Dates Alleviate Neuroinflammation in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikent, A.; Laaraj, S.; Adiba, A.; Elfazazi, K.; Ouakhir, H.; Bouhrim, M.; Shahat, A.A.; Herqash, R.N.; Elamrani, A.; Addi, M. Nutritional Composition Health Benefits and Quality of Fresh and Dried Figs from Eastern Morocco. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, E.; Tsegay, Z.T.; Smaoui, S.; Varzakas, T. Chemical Structure, Composition, Bioactive Compounds, and Pattern Recognition Techniques in Figs (Ficus carica L.) Quality and Authenticity: An Updated Review. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Caporaso, N.; Paduano, A.; Sacchi, R. Phenolic Compounds in Fresh and Dried Figs from Cilento (Italy), by Considering Breba Crop and Full Crop, in Comparison to Turkish and Greek Dried Figs. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, C1278–C1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trad, M.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Gaaliche, B.; Ginies, C.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Mars, M. Caprification Modifies Polyphenols but Not Cell Wall Concentrations in Ripe Figs. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 160, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladika, G.; Strati, I.F.; Tsiaka, T.; Cavouras, D.; Sinanoglou, V.J. On the Assessment of Strawberries’ Shelf-Life and Quality, Based on Image Analysis, Physicochemical Methods, and Chemometrics. Foods 2024, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, P.; Kritsi, E.; Ladika, G.; Tsafou, P.; Tsiantas, K.; Tsiaka, T.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Cavouras, D.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Estimation of Tomato Quality During Storage by Means of Image Analysis, Instrumental Analytical Methods, and Statistical Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, P.; Ladika, G.; Tsiantas, K.; Kritsi, E.; Tsiaka, T.; Cavouras, D.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Quality Assessment of Greenhouse-Cultivated Cucumbers (Cucumis sativus) during Storage Using Instrumental and Image Analyses. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinanoglou, V.J.; Tsiaka, T.; Aouant, K.; Mouka, E.; Ladika, G.; Kritsi, E.; Konteles, S.J.; Ioannou, A.-G.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Strati, I.F.; et al. Quality Assessment of Banana Ripening Stages by Combining Analytical Methods and Image Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, V.; Strati, I.F.; Fotakis, C.; Liouni, M.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Herbal Distillates: A New Era of Grape Marc Distillates with Enriched Antioxidant Profile. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matić, P.; Sabljić, M.; Jakobek, L. Validation of Spectrophotometric Methods for the Determination of Total Polyphenol and Total Flavonoid Content. J. AOAC Int. 2017, 100, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantzouraki, D.Z.; Sinanoglou, V.J.; Zoumpoulakis, P.G.; Glamočlija, J.; Ćirić, A.; Soković, M.; Heropoulos, G.; Proestos, C. Antiradical–Antimicrobial Activity and Phenolic Profile of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Juices from Different Cultivars: A Comparative Study. RSC Adv. 2014, 5, 2602–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantzouraki, D.Z.; Sinanoglou, V.J.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Proestos, C. Comparison of the Antioxidant and Antiradical Activity of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.) by Ultrasound-Assisted and Classical Extraction. Anal. Lett. 2016, 49, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladika, G.; Christodoulou, P.; Kritsi, E.; Tsiaka, T.; Sotiroudis, G.; Cavouras, D.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Exploring Postharvest Metabolic Shifts and NOX2 Inhibitory Potential in Strawberry Fruits and Leaves via Untargeted LC-MS/MS and Chemometric Analysis. Metabolites 2025, 15, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Dong, X.; Liang, J.; Jia, M.; Sun, L.; Han, Y.; Zhou, S.; Sun, R. Analysis of the Relationship Between Organic Acid, Total Soluble Solids, Total Phenolic, and Total Flavonoids in Ficus carica. Appl. Fruit. Sci. 2025, 67, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, L.; Kongoli, R.; Dervishi, J. Influence of Maturity Stage on Polyphenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Fig (Ficus carica L.) Fruit in Native Albanian Varieties. Chem. Proc. 2022, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetha, D.; Chandrasekaran, I.; Gurumeenakshi, G.; Rani, A.; Amuthaselvi, G.; Neelavathi, R. Evaluation of Quality Attributes in Fresh Fig (Ficus carica L.) Fruits. Biol. Forum–Int. J. 2022, 14, 532–537. [Google Scholar]

- Hssaini, L.; Charafi, J.; Hanine, H.; Ennahli, S.; Mekaoui, A.; Mamouni, A.; Razouk, R. Correction to: Comparative Analysis and Physio-biochemical Screening of an Ex-situ Fig (Ficus carica L.) Collection. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán, A.J.; Domínguez, M.G.; Pérez-López, M.; Galván, A.I.; Pérez-Gragera, F.; López-Corrales, M. Agronomic Performance and Fruit Quality of Fresh Fig Varieties Trained in Espaliers Under a High Planting Density. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündeşli, M.A.; Ugur, R.; Urün, I.; Ercisli, S.; Kafkas, N.E.; Ilhan, G.; Spalevic, V.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A. Evaluation of the Total Phenolic Content, Sugar, Organic Acid, Volatile Compounds and Antioxidant Capacities of Fig (Ficus carica L.) Genotypes Selected from the Mediterranean Region of Türkiye. Hortic. Sci. 2024, 51, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, L.; Koto, R. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Physico-Chemical Characteristics in Different Native Albanian Fig Varieties (Ficus carica L.). J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2022, 41, 288–296. [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Alonso, C.A.; Niño-Medina, G.; Gutiérrez-Díez, A.; García-López, J.I.; Vázquez-Alvarado, R.E.; López-Jiménez, A.; Olivares-Sáenz, E. Physicochemical Characteristics, Minerals, Phenolic Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity in Fig Tree Fruits with Macronutrient Deficiencies. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2020, 48, 1585–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Martín, A.; López-Corrales, M.; de Córdoba, M.G.; Galván, A.I.; Serradilla, M.J. Evaluation of the Physicochemical and Sensory Characteristics of Different Fig Cultivars for the Fresh Fruit Market. Foods 2020, 9, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, B.R.; Neves, C.M.B.; Moumni, M.; Romanazzi, G.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Cardoso, S.M.; Wessel, D.F. A Comparative Study of Traditional Sun Drying and Hybrid Solar Drying on Quality, Safety, and Bioactive Compounds in “Pingo de Mel” Fig. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz, R.A.; Leonel, S.; Souza, J.M.A.; Modesto, J.H.; Ferreira, R.B.; de Silva, M.S. Agronomical and Quality Differences of Four Fig Cultivars Grown in Brazil. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2021, 42, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascellani, A.; Natali, L.; Cavallini, A.; Mascagni, F.; Caruso, G.; Gucci, R.; Havlik, J.; Bernardi, R. Moderate Salinity Stress Affects Expression of Main Sugar Metabolism and Transport Genes and Soluble Carbohydrate Content in Ripe Fig Fruits (Ficus carica L. Cv. Dottato). Plants 2021, 10, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljane, F.; Neily, M.H.; Msaddak, A. Phytochemical Characteristics and Antioxidant Activity of Several Fig (Ficus carica L.) Ecotypes. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalişkan, O.; Aytekin Polat, A. Phytochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Selected Fig (Ficus carica L.) Accessions from the Eastern Mediterranean Region of Turkey. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 128, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, Ç.; Birinci, C.; Kemal, M.; Kolayli, S. The Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Figs (Ficus carica L.) Grown in the Black Sea Region. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2023, 78, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, I.; Syeda Hina Naqvi, M.Q.; Rehman, N.U. Comparative Antioxidative and Antidiabetic Activities of Ficus carica Pulp, Peel and Leaf and Their Correlation with Phytochemical Contents. OAJPR 2020, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hssaini, L.; Hernandez, F.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Charafi, J.; Razouk, R.; Houmanat, K.; Ouaabou, R.; Ennahli, S.; Elothmani, D.; Hmid, I.; et al. Survey of Phenolic Acids, Flavonoids and In Vitro Antioxidant Potency Between Fig Peels and Pulps: Chemical and Chemometric Approach. Molecules 2021, 26, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trad, M.; Ginies, C.; Gaaliche, B.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Mars, M. Relationship between Pollination and Cell Wall Properties in Common Fig Fruit. Phytochemistry 2014, 98, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Oktiani, R.; Ragadhita, R. How to Read and Interpret FTIR Spectroscope of Organic Material. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsi, E.; Christodoulou, P.; Michos, M.; Ladika, G.; Bratakos, S.; Tsiantas, K.; Tsiaka, T.; Cavouras, D.; Sinanoglou, V. A Comparative Study of the Molecular Constituent Profile Among Brussels Sprout Leaf Layers by Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometrics. Anal. Lett. 2024, 58, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, S.; Battaglia, G.; Tian, X. Amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s Disease: Structure, Toxicity, Distribution, Treatment, and Prospects. Ibrain 2024, 10, 266–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampel, H.; Vassar, R.; De Strooper, B.; Hardy, J.; Willem, M.; Singh, N.; Zhou, J.; Yan, R.; Vanmechelen, E.; De Vos, A.; et al. The β-Secretase BACE1 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 89, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayad, A.; Najafi, S.; Hussen, B.M.; Abdullah, S.T.; Movahedpour, A.; Taheri, M.; Hajiesmaeili, M. The Emerging Roles of the β-Secretase BACE1 and the Long Non-Coding RNA BACE1-AS in Human Diseases: A Focus on Neurodegenerative Diseases and Cancer. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, M.; Correa-Basurto, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; Vitorica, J.; Rosales-Hernández, M.C. Asp32 and Asp228 Determine the Selective Inhibition of BACE1 as Shown by Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 124, 1142–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, T.; Kamble, P.; Garg, P. Rational Discovery of BACE1-Selective Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease. Drug Dev. Res. 2025, 86, e70169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Bharate, S.B. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Coumarin Triazoles as Dual Inhibitors of Cholinesterases and β-Secretase. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 11161–11176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naushad, M.; Durairajan, S.S.K.; Bera, A.K.; Senapati, S.; Li, M. Natural Compounds with Anti-BACE1 Activity as Promising Therapeutic Drugs for Treating Alzheimer’s Disease. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Yusof, N.I.S.; Abdullah, Z.L.; Othman, N.; Mohd Fauzi, F. Structure–Activity Relationship Analysis of Flavonoids and Its Inhibitory Activity Against BACE1 Enzyme Toward a Better Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 874615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shrestha, S.; Jung, H.A.; Choi, J.S. Bioassay-Guided Isolation of BACE1 Inhibitors from Crataegus pinnatifida. Phytomedicine Plus 2023, 3, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Singh, M.; Sharma, P.; Mujwar, S.; Singh, V.; Mishra, K.K.; Singh, T.G.; Singh, T.; Ahmad, S.F. Scaffold Morphing and In Silico Design of Potential BACE-1 (β-Secretase) Inhibitors: A Hope for a Newer Dawn in Anti-Alzheimer Therapeutics. Molecules 2023, 28, 6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M, Y.; Shetty, N.S. Advances in the Synthetic Approaches to β-Secretase (BACE-1) Inhibitors in Countering Alzheimer’s: A Comprehensive Review. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 35367–35433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawarkar, R.D.; Khan, A.; Mali, S.N.; Deshmukh, P.K.; Ingle, R.G.; Al-Hussain, S.A.; Al-Mutairi, A.A.; Zaki, M.E.A. Cheminformatics-Driven Prediction of BACE-1 Inhibitors: Affinity and Molecular Mechanism Exploration. Chem. Phys. Impact 2024, 9, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, C.; Van Greunen, D.; Cordier, W.; Nell, M.; Steenkamp, V.; Stander, A.; Panayides, J.-L.; Riley, D. Binding Pose Analysis of Hydroxyethylamine Based β-Secretase Inhibitors and Application Thereof to the Design and Synthesis of Novel Indeno[1,2-b]Indole Based Inhibitors. Arkivoc 2020, 2020, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronk, S.A.; Carlson, H.A. The Role of Tyrosine 71 in Modulating the Flap Conformations of BACE1. Proteins 2011, 79, 2247–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodney, M.A.; Beck, E.M.; Butler, C.R.; Barreiro, G.; Johnson, E.F.; Riddell, D.; Parris, K.; Nolan, C.E.; Fan, Y.; Atchison, K.; et al. Utilizing Structures of CYP2D6 and BACE1 Complexes to Reduce Risk of Drug–Drug Interactions with a Novel Series of Centrally Efficacious BACE1 Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3223–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, B.-M.; Kolmodin, K.; Karlström, S.; von Berg, S.; Söderman, P.; Holenz, J.; Berg, S.; Lindström, J.; Sundström, M.; Turek, D.; et al. Design and Synthesis of β-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein Cleaving Enzyme (BACE1) Inhibitors with in Vivo Brain Reduction of β-Amyloid Peptides. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 9346–9361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozal, V.; García-Rubia, A.; Cuevas, E.P.; Pérez, C.; Tosat-Bitrián, C.; Bartolomé, F.; Carro, E.; Ramírez, D.; Palomo, V.; Martínez, A. From Kinase Inhibitors to Multitarget Ligands as Powerful Drug Leads for Alzheimer’s Disease Using Protein-Templated Synthesis. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 19493–19503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdal, T.; Capanoglu, E.; Altay, F. A Review on Protein–Phenolic Interactions and Associated Changes. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.