Beam Damage Detection and Characterization Using Rotation Response from a Moving Load and Damage Candidate Grid Search (DCGS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Derivations

2.1. Beam Rotation of a Healthy Beam

2.2. Beam Rotation of a Damaged Beam

3. Rotation-Based Damage Detection Using the Candidate Grid Search Technique (DCGS)

4. Analytical and Experimental Procedures for the DCGS Evaluation

4.1. Analytical Evaluation via Finite Element Method (FEM) Analysis

4.2. Analytical Damage Scenarios

4.3. Laboratory-Scale Experimental Evaluation

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Analytical Results

5.2. Confidence Interval (CI) Analysis of FEM Results

5.3. Methodology Limitation Using Healthy FEM Response

5.4. Healthy Region Identification Using the Healthy FEM Response

5.5. Analytical Assessment of the DCGS Method

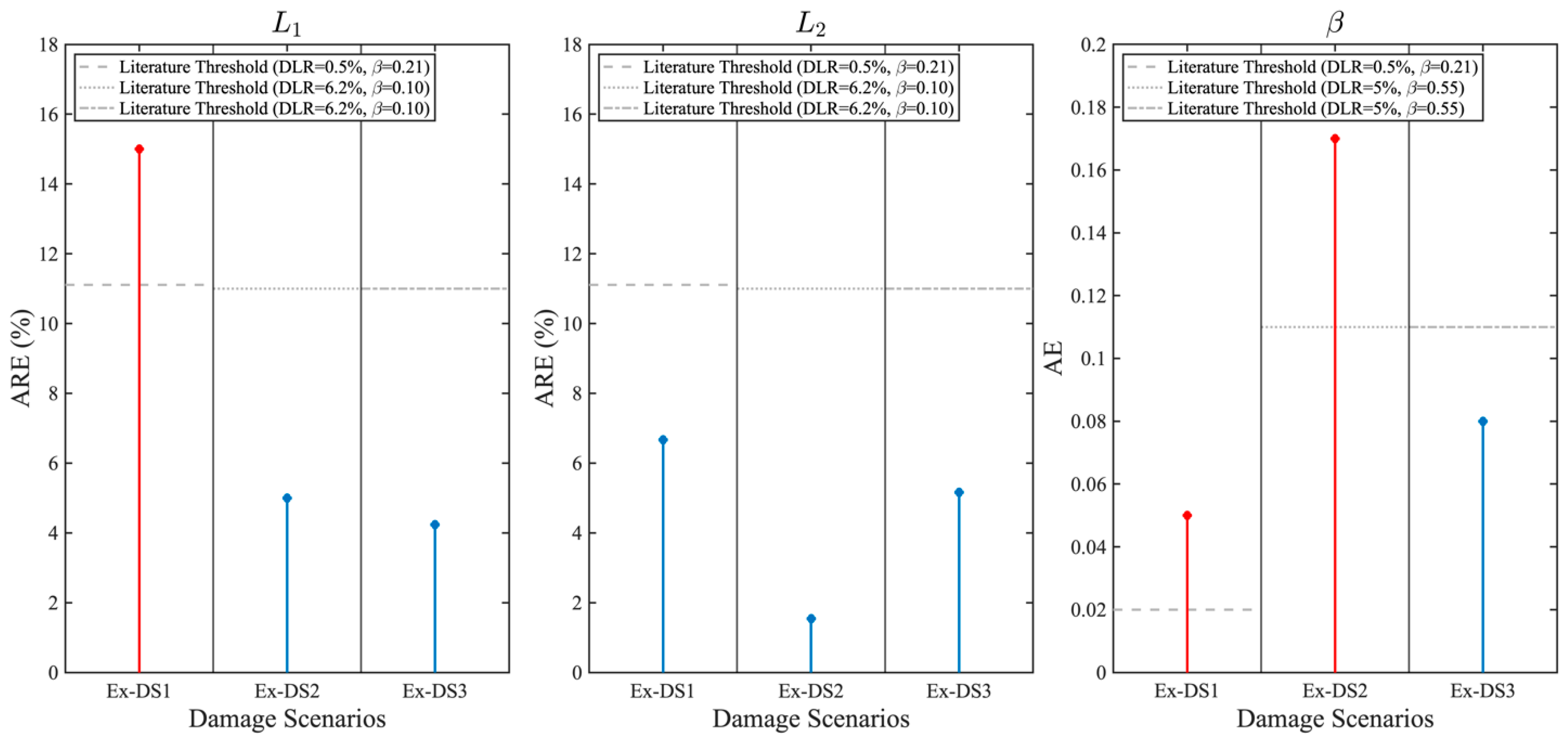

5.6. Experimental Assessment of the DCGS Method

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sitton, J.D.; Zeinali, Y.; Rajan, D.; Story, B.A. Frequency estimation on two-span continuous bridges using dynamic responses of passing vehicles. J. Eng. Mech. 2020, 146, 04019115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCE. A Comprehensive Assessment of America’s Infrastructure. 2025. Available online: https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- McGeown, C.; Huseynov, F.; Hester, D.; McGetrick, P.; Obrien, E.J.; Pakrashi, V. Using measured rotation on a beam to detect changes in its structural condition. J. Struct. Integr. Maint. 2021, 6, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Huang, C.K.; Chen, C.S. Damage assessment of beam by a quasi-static moving vehicular load. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2011, 3, 417–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.T.; Thambiratnam, D.P.; Nguyen, A.; Chan, T.H.T. A new method for locating and quantifying damage in beams from static deflection changes. Eng. Struct. 2019, 180, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, E.S.M.M. Damage severity for cracked simply supported beams. Fract. Struct. Integr. 2021, 15, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Saha, P.; Patro, S.K. Vibration-based damage detection techniques used for health monitoring of structures: A review. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2016, 6, 477–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doebling, S.W.; Farrar, C.R.; Prime, M.B. A summary review of vibration-based damage identification methods. Shock Vib. Dig. 1998, 30, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Qiao, P. Vibration-based damage identification methods: A review and comparative study. Struct. Health Monit. 2011, 10, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytter, A. Vibrational Based Inspection of Civil Engineering Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.; Hu, J.W.; Lee, J. Summary review of structural health monitoring applications for highway bridges. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2016, 30, 04015072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H.; Farrar, C.R.; Hemez, F.M.; Shunk, D.D.; Stinemates, D.W.; Nadler, B.R.; Czarnecki, J.J. A review of structural health monitoring literature: 1996–2001. Los Alamos Natl. Lab. USA 2003, 1, 10–12989. [Google Scholar]

- Story, B.A.; Fry, G.T. A structural impairment detection system using competitive arrays of artificial neural networks. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2014, 29, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, K.; Dulieu-Barton, J.M. An overview of intelligent fault detection in systems and structures. Struct. Health Monit. 2004, 3, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.; Thambiratnam, D. Structural Health Monitoring in Australia; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zeinali, Y.; Story, B.A. Impairment localization and quantification using noisy static deformation influence lines and Iterative Multi-parameter Tikhonov Regularization. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 109, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynov, F.; Kim, C.; Obrien, E.J.; Brownjohn, J.M.W.; Hester, D.; Chang, K.C. Bridge damage detection using rotation measurements–Experimental validation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 135, 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitton, J.D.; Rajan, D.; Story, B.A. Damage scenario analysis of bridges using crowdsourced smartphone data from passing vehicles. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2024, 39, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabi, R.R.; Vailati, M.; Monti, G. Effectiveness of vibration-based techniques for damage localization and lifetime prediction in structural health monitoring of bridges: A comprehensive review. Buildings 2024, 14, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, P.; Adams, R.D. The location of defects in structures from measurements of natural frequencies. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 1979, 14, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajela, P.; Soeiro, F.J. Structural damage detection based on static and modal analysis. AIAA J. 1990, 28, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, B.A.; Fry, G.T. Methodology for designing diagnostic data streams for use in a structural impairment detection system. J. Bridge Eng. 2014, 19, 04013020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ramirez, C.A.; Amezquita-Sanchez, J.P.; Adeli, H.; Valtierra-Rodriguez, M.; Romero-Troncoso, R.D.J.; Dominguez-Gonzalez, A.; Osornio-Rios, R.A. Time-frequency techniques for modal parameters identification of civil structures from acquired dynamic signals. J. Vibroengineering 2016, 18, 3164–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Du, B.; Yi, J.; Yuan, X.; Pan, C.; Kong, X. Extracting flexural and torsional mode shapes of bridges using a 3D two-axle passing vehicle with experimental validations. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 219, 114256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgin, R. Damage identification technique based on mode shape analysis of beam structures. Structures 2020, 27, 2300–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, J.K.; Sun, B.X.; Liang, C.F. Damage localization for beam structure by moving load. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1687814017695956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, C.P. A frequency and curvature based experimental method for locating damage in structures. J. Vib. Acoust. 2000, 122, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, B.; Fry, G. Implementation of a Structural Impairment Detection System on a 100 Year-Old Bascule Bridge. In Structural Health Monitoring 2013: A Roadmap to Intelligent Structures, Proceedings of the Ninth International Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring, Stanford, CA, USA, 10–12 September 2013; DEStech Publications, Inc.: Lancaster, PA, USA, 2013; p. 1729. [Google Scholar]

- Sitton, J.D.; Rajan, D.; Story, B.A. Bridge frequency estimation strategies using smartphones. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2020, 10, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah1a, O.; Seyedpoor, S.M. A new damage detection indicator for beams based on mode shape data. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2015, 53, 725–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvnjak, I.; Damjanović, D.; Bartolac, M.; Skender, A. Mode shape-based damage detection method (MSDI): Experimental validation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khresat, H.; Thompson, H.B., II; Story, B.A. Improved Rail Bridge Strick Detection and Characterization. In Proceedings of the 2024 AREMA Conference, Louisville, KY, USA, 15–18 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, J.P.; Loh, K.J. A summary review of wireless sensors and sensor networks for structural health monitoring. Shock Vib. Dig. 2006, 38, 91–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Huang, M.; Wan, N.; Zhang, J. The current development of structural health monitoring for bridges: A review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Nagayama, T.; Su, D.; Fujino, Y. A damage detection algorithm utilizing dynamic displacement of bridge under moving vehicle. Shock Vib. 2016, 2016, 8454567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.B.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H.; Zuo, Q. A novel extraction method for the actual influence line of bridge structures. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 553, 117605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.Y.; Ren, W.X.; Zhu, S. Damage detection of beam structures using quasi-static moving load induced displacement response. Eng. Struct. 2017, 145, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Xu, H.; Zhang, B.; Xiong, F.; Wang, Z.L. Measuring bridge frequencies by a test vehicle in non-moving and moving states. Eng. Struct. 2020, 203, 109859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. Damage detection in beam bridges using quasi-static displacement influence lines. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, X. Structural damage detection of the bridge under moving loads with the quasi-static displacement influence line from one sensor. Measurement 2023, 211, 112599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Accurate and Scalable Bridge Health Monitoring Using Drive-By Vehicle Vibrations. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yi, T.H.; Qu, C.X.; Han, Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Mei, X.D. Experimental studies of extracting bridge mode shapes by response of a moving vehicle. J. Bridge Eng. 2023, 28, 04023076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alampalli, S.; Frangopol, D.M.; Grimson, J.; Halling, M.W.; Kosnik, D.E.; Lantsoght, E.O.; Yang, D.; Zhou, Y.E. Bridge load testing: State-of-the-practice. J. Bridge Eng. 2021, 26, 03120002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantsoght, E.O.; van der Veen, C.; de Boer, A.; Hordijk, D.A. State-of-the-art on load testing of concrete bridges. Eng. Struct. 2017, 150, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štimac, I.; Mihanović, A.; Kožar, I. Damage detection from analysis of displacement influence lines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Bridges, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–24 May 2006; pp. 1001–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.W.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Q.L.; Li, J.; Zhu, S. Damage quantification of beam structures using deflection influence line changes and sparse regularization. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2021, 24, 1997–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshallaqi, H.H.; Story, B.A. Truss Bridge Damage Localization and Severity Estimation Using Influence Lines. In Proceedings of the 2025 Railway Engineering Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 10–12 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zeinali, Y.; Story, B.A. Framework for flexural rigidity estimation in Euler-Bernoulli beams using deformation influence lines. Infrastructures 2017, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Tian, L.; Song, X. Real-time, non-contact and targetless measurement of vertical deflection of bridges using off-axis digital image correlation. NDT E Int. 2016, 79, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Pan, B. Remote bridge deflection measurement using an advanced video deflectometer and actively illuminated LED targets. Sensors 2016, 16, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, D.; Feng, M.Q. Experimental validation of cost-effective vision-based structural health monitoring. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 88, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdenebat, D.; Waldmann, D.; Scherbaum, F.; Teferle, N. The Deformation Area Difference (DAD) method for condition assessment of reinforced structures. Eng. Struct. 2018, 155, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, D.; Brownjohn, J.; Huseynov, F.; Obrien, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Casero, M. Identifying damage in a bridge by analysing rotation response to a moving load. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 16, 1050–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nady, H.O.; Abdo, M.A.; Kaiser, F. Comparative study of using rotation influence lines and their derivatives for structural damage detection. Structures 2023, 48, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.Y.; Ren, W.X.; Zhu, S. Baseline-free damage localization method for statically determinate beam structures using dual-type response induced by quasi-static moving load. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 400, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreaus, U.; Baragatti, P. Experimental damage detection of cracked beams by using nonlinear characteristics of forced response. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2012, 31, 382–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Lin, C.W.; Yau, J.D. Extracting bridge frequencies from the dynamic response of a passing vehicle. J. Sound Vib. 2004, 272, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekjafarian, A.; Corbally, R.; Gong, W. A review of mobile sensing of bridges using moving vehicles: Progress to date, challenges and future trends. Structures 2022, 44, 1466–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, T.J.; Kondor, D.; Milardo, S.; Eshkevari, S.S.; Santi, P.; Pakzad, S.N.; Buehler, M.J.; Ratti, C. Crowdsourcing bridge dynamic monitoring with smartphone vehicle trips. Commun. Eng. 2022, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Qian, Y.; Wu, Y. Bridge damping identification by vehicle scanning method. Eng. Struct. 2019, 183, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Au, F.T.; Yang, D.; Zhang, J. Active learning structural model updating of a multisensory system based on Kriging method and Bayesian inference. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 38, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OBrien, E.J.; Mcgetrick, P.J.; González, A. A drive-by inspection system via vehicle moving force identification. Smart Struct. Syst. 2014, 13, 821–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitton, J. Indirect Bridge Monitoring Using Crowdsourced Smartphone Data from Passing Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, Lyle School of Engineering, Dallas, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Orsak, J. A Theoretical Structural Impairment Detection System for Timber Railway Bridges. Master’s Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Khorram, A.; Bakhtiari-Nejad, F.; Rezaeian, M. Comparison studies between two wavelet based crack detection methods of a beam subjected to a moving load. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 51, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Zhang, B.; Qian, Y.; Wu, Y. Contact-point response for modal identification of bridges by a moving test vehicle. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2018, 18, 1850073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, J.; Deng, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, H. Identification of multiple bridge frequencies using a movable test vehicle by approximating axle responses to contact-point responses: Theory and experiment. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 15, 1041–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, A.H. A history of railway vehicle dynamics. In Handbook of Railway Vehicle Dynamics, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 5–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeler, R.C. Structural Analysis, 11th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | Force/length2 | |

| Force/length2 | ||

| 10 | Length | |

| 1.0 | Force |

| DS | DLR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FE-DS1 | 5 | 5.1 | 1% | 0.05 |

| FE-DS2 | 5 | 5.1 | 1% | 0.20 |

| FE-DS3 | 5 | 5.1 | 1% | 0.5 |

| FE-DS4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 1% | 0.05 |

| FE-DS5 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 1% | 0.20 |

| FE-DS6 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 1% | 0.5 |

| FE-DS7 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 10% | 0.05 |

| FE-DS8 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 10% | 0.20 |

| FE-DS9 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 10% | 0.5 |

| FE-DS10 | 7 | 8 | 10% | 0.05 |

| FE-DS11 | 7 | 8 | 10% | 0.20 |

| FE-DS12 | 7 | 8 | 10% | 0.5 |

| Parameters | Values | Units | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | Steel | |||||

| Healthy | Ex-DS1 | Ex-DS2 | Healthy | Ex-DS3 | ||

| 0.90 | 1.81 | |||||

| 0.94 | 92.97 | |||||

| 70.06 | 200 | |||||

| 3.18 | 9.53 | |||||

| 25.32 | 304.00 | |||||

| - | 19.97 | 15.20 | - | 243.84 | ||

| 68 | 53 | 41 | 21,940 | 17,552 | ||

| - | 0.20 | 0.60 | - | 1.18 | ||

| - | 0.30 | 0.65 | - | 1.55 | ||

| DLR | - | 11.10 | 5.60 | - | 20.50 | % |

| - | 0.21 | 0.40 | - | 0.20 | - | |

| FE-DS | % | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. | Std. | ARE (%) | AE | Avg. | Std. | ARE (%) | AE | Avg. | Std. | ARE (%) | AE | ||

| 1 | 0 | 5.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.10 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 4.98 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 5.26 | 0.37 | 3.14 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 20.00 | 0.01 | |

| 5 | 5.11 | 0.52 | 2.20 | 0.11 | 5.23 | 0.51 | 2.55 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 20.00 | 0.01 | |

| 9 | 4.70 | 0.63 | 6.00 | 0.30 | 4.83 | 0.59 | 5.29 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 60.00 | 0.03 | |

| 2 | 0 | 5.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.10 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 4.98 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 5.16 | 0.10 | 1.18 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 25.00 | 0.05 | |

| 5 | 4.95 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 5.14 | 0.17 | 0.78 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 10.00 | 0.02 | |

| 9 | 5.14 | 0.37 | 2.80 | 0.14 | 5.42 | 0.25 | 6.27 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 30.00 | 0.06 | |

| 3 | 0 | 5.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.10 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 4.99 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 5.12 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.09 | 8.00 | 0.04 | |

| 9 | 4.93 | 0.11 | 1.40 | 0.07 | 5.15 | 0.05 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 26.00 | 0.13 | |

| 4 | 0 | 7.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.60 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 7.51 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 7.78 | 0.52 | 2.37 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 20.00 | 0.01 | |

| 5 | 7.44 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 7.59 | 0.67 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 100.0 | 0.05 | |

| 9 | 7.30 | 0.68 | 2.67 | 0.20 | 7.38 | 0.71 | 2.89 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 160.0 | 0.08 | |

| 5 | 0 | 7.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.60 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 7.46 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 7.66 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 30.00 | 0.06 | |

| 5 | 7.41 | 0.35 | 1.20 | 0.09 | 7.57 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 30.00 | 0.06 | |

| 9 | 7.47 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 7.63 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 10.00 | 0.02 | |

| 6 | 0 | 7.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.60 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 7.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 7.48 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 7.62 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 12.00 | 0.06 | |

| 9 | 7.44 | 0.11 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 7.68 | 0.19 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 20.00 | 0.10 | |

| 7 | 0 | 4.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 4.52 | 0.12 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 5.48 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 4.63 | 0.18 | 2.89 | 0.13 | 5.36 | 0.38 | 2.55 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 160.0 | 0.08 | |

| 9 | 4.56 | 0.43 | 1.33 | 0.06 | 5.40 | 0.47 | 1.82 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 180.0 | 0.09 | |

| 8 | 0 | 4.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 4.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 4.50 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.52 | 0.08 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 9 | 4.49 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 5.50 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 9 | 0 | 4.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 4.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 4.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 9 | 4.51 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 5.49 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 10 | 0 | 7.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 7.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.03 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 6.88 | 0.45 | 1.71 | 0.12 | 8.12 | 0.56 | 1.50 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 40.00 | 0.02 | |

| 9 | 7.36 | 0.30 | 5.14 | 0.36 | 7.61 | 0.31 | 4.88 | 0.39 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 320.0 | 0.16 | |

| 11 | 0 | 7.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.99 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 7.01 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 7.99 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 5.00 | 0.01 | |

| 9 | 7.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.99 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 5.00 | 0.01 | |

| 12 | 0 | 7.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 9 | 7.01 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 2.00 | 0.01 | |

| Method | Noise ε (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Value | ARE (%) | Actual Value | ARE (%) | Actual Value | AE | ||

| DCGS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Deflection difference [5] | 10.0 | 8.3 | 0.0 | ||||

| DCGS | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Dynamic curvature [35] | 2.82 | 3.95 | 0.14 | ||||

| DCGS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| RIL [54] | 1.72 | 1.67 | 0.0 | ||||

| DCGS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Mode shape and frequency analysis [25] | 1.0 | 0.83 | 0.01 | ||||

| DCGS | 5.0 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 0.05 | |||

| DIL [46] | - | - | 0.08 | ||||

| DCGS | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.04 | |||

| RIL [16] | - | - | 0.29 | ||||

| FE-DS | ε % | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | CI-UB | CI-LB | Mean | CI-UB | CI-LB | Mean | CI-UB | CI-LB | ||

| 1 | 2 | 4.98 | 5.08 | 4.88 | 5.31 | 5.40 | 5.21 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| 5 | 5.08 | 5.17 | 4.98 | 5.28 | 5.36 | 5.19 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| 9 | 4.68 | 4.80 | 4.56 | 4.90 | 5.02 | 4.78 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.06 | |

| 2 | 2 | 4.95 | 4.96 | 4.94 | 5.19 | 5.21 | 5.17 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| 5 | 4.93 | 4.96 | 4.90 | 5.14 | 5.17 | 5.11 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.15 | |

| 9 | 5.16 | 5.24 | 5.08 | 5.45 | 5.51 | 5.39 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.12 | |

| 3 | 2 | 4.98 | 4.98 | 4.97 | 5.13 | 5.14 | 5.12 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.40 |

| 5 | 4.98 | 4.99 | 4.98 | 5.13 | 5.13 | 5.12 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.42 | |

| 9 | 4.95 | 4.97 | 4.93 | 5.15 | 5.16 | 5.14 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.35 | |

| 4 | 2 | 7.49 | 7.59 | 7.39 | 7.72 | 7.81 | 7.62 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| 5 | 7.44 | 7.57 | 7.30 | 7.57 | 7.70 | 7.43 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | |

| 9 | 7.35 | 7.46 | 7.23 | 7.45 | 7.57 | 7.33 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.10 | |

| 5 | 2 | 7.44 | 7.46 | 7.42 | 7.68 | 7.71 | 7.66 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| 5 | 7.37 | 7.44 | 7.30 | 7.59 | 7.67 | 7.52 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.13 | |

| 9 | 7.46 | 7.57 | 7.35 | 7.63 | 7.74 | 7.52 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.19 | |

| 6 | 2 | 7.48 | 7.49 | 7.47 | 7.62 | 7.63 | 7.61 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.42 |

| 5 | 7.48 | 7.49 | 7.47 | 7.64 | 7.65 | 7.63 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.40 | |

| 9 | 7.40 | 7.43 | 7.38 | 7.69 | 7.73 | 7.66 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.32 | |

| 7 | 2 | 4.51 | 4.53 | 4.48 | 5.49 | 5.51 | 5.46 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| 5 | 4.60 | 4.63 | 4.56 | 5.42 | 5.49 | 5.34 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.09 | |

| 9 | 4.55 | 4.63 | 4.47 | 5.42 | 5.51 | 5.33 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.11 | |

| 8 | 2 | 4.49 | 4.50 | 4.47 | 5.51 | 5.52 | 5.49 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| 5 | 4.48 | 4.50 | 4.47 | 5.52 | 5.54 | 5.50 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| 9 | 4.49 | 4.50 | 4.47 | 5.49 | 5.51 | 5.47 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| 9 | 2 | 4.50 | 4.51 | 4.49 | 5.51 | 5.52 | 5.49 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.49 |

| 5 | 4.51 | 4.52 | 4.50 | 5.50 | 5.51 | 5.48 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.50 | |

| 9 | 4.52 | 4.53 | 4.50 | 5.50 | 5.51 | 5.48 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.50 | |

| 10 | 2 | 7.02 | 7.04 | 6.99 | 8.08 | 8.12 | 8.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| 5 | 6.87 | 6.96 | 6.79 | 8.06 | 8.16 | 7.97 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.06 | |

| 9 | 7.32 | 7.38 | 7.26 | 7.63 | 7.70 | 7.57 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.18 | |

| 11 | 2 | 6.99 | 7.00 | 6.97 | 7.99 | 8.01 | 7.97 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 |

| 5 | 7.01 | 7.03 | 7.00 | 7.99 | 8.01 | 7.97 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.20 | |

| 9 | 6.99 | 7.01 | 6.97 | 8.00 | 8.02 | 7.97 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | |

| 12 | 2 | 7.00 | 7.01 | 6.99 | 8.00 | 8.02 | 7.99 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.49 |

| 5 | 6.99 | 7.00 | 6.98 | 8.01 | 8.03 | 8.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.49 | |

| 9 | 7.00 | 7.01 | 6.98 | 8.00 | 8.02 | 7.99 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.50 | |

| Damage Scenarios | Grid Step Size | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | ARE (%) | AE | Est. | ARE (%) | AE | Est. | ARE (%) | AE | ||

| Ex-DS1 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 15.00 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 6.67 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 23.81 | 0.05 |

| 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 16.67 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 14.29 | 0.03 | |

| 0.1 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 14.29 | 0.03 | |

| Ex-DS2 | 0.01 | 0.63 | 5.00 | 0.03 | 0.66 | 1.54 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 42.50 | 0.17 |

| 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 7.69 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 27.50 | 0.11 | |

| 0.1 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 7.69 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 27.50 | 0.11 | |

| Ex-DS3 | 0.01 | 1.13 | 4.24 | 0.05 | 1.63 | 5.16 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 40.00 | 0.08 |

| 0.05 | 1.15 | 2.54 | 0.03 | 1.60 | 3.23 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 45.00 | 0.09 | |

| 0.1 | 1.10 | 6.78 | 0.08 | 1.80 | 16.13 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 30.00 | 0.06 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alhumaidi, M.Y.; Story, B.A. Beam Damage Detection and Characterization Using Rotation Response from a Moving Load and Damage Candidate Grid Search (DCGS). Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010539

Alhumaidi MY, Story BA. Beam Damage Detection and Characterization Using Rotation Response from a Moving Load and Damage Candidate Grid Search (DCGS). Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):539. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010539

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhumaidi, Muath Y., and Brett A. Story. 2026. "Beam Damage Detection and Characterization Using Rotation Response from a Moving Load and Damage Candidate Grid Search (DCGS)" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010539

APA StyleAlhumaidi, M. Y., & Story, B. A. (2026). Beam Damage Detection and Characterization Using Rotation Response from a Moving Load and Damage Candidate Grid Search (DCGS). Applied Sciences, 16(1), 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010539