Abstract

Severe drill string vibrations, particularly stick–slip, significantly compromise drilling efficiency and tool longevity in deep hard formations. Compound percussive drilling (CPD) has emerged as a promising technique to mitigate these vibrations and enhance the rate of penetration (ROP). However, the complex coupling mechanisms between impact loads and bit dynamics remain insufficiently understood. This study aims to elucidate the axial–torsional vibration characteristics of the drill bit and the underlying vibration reduction mechanisms under CPD conditions. A multi-degree-of-freedom (MDOF) dynamic model was first established, integrating both the dynamics of the CPD tool and the regenerative cutting effects inherent in bit–rock interactions. The governing equations were then solved numerically using the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method, followed by a systematic parametric sensitivity analysis to quantify the influence of impact parameters on vibration mitigation. The results show that while CPD induces detrimental axial–torsional vibrations in soft rock formations, it effectively suppresses stick–slip and enhances ROP in hard rock formations. Notably, coupled axial–torsional impact loading exhibits superior vibration suppression capabilities compared to singular axial or torsional impacts. A critical proportional relationship for parameter optimization was identified; specifically, maximizing vibration mitigation requires scaling the axial impact load proportionally with the torsional impact load. For example, when the axial impact load amplitudes are 5 kN and 10 kN, the corresponding optimal torsional impact load amplitudes are approximately 500 N·m and 1000 N·m, respectively. Furthermore, maintaining the impact frequency within the range of 10–30 Hz yields optimal vibration reduction effects. The benefits of CPD become increasingly pronounced with higher rock strength and longer drill strings. These findings confirm the suitability of CPD technology for deep hard rock environments and provide theoretical guidelines for the optimal selection of impact parameters in engineering applications.

1. Introduction

The Polycrystalline Diamond Compact (PDC) bit achieves a higher Rate of Penetration (ROP) than the roller-cone bit, making it a widely adopted tool in oil and gas drilling for efficient rock-breaking. Since its introduction to the oil drilling industry in the 1970s, the PDC bit has rapidly gained dominance in the global market for rock-breaking tools, currently accounting for over 90% of total footage drilled [1].

However, as global oil and gas exploration shifts toward deeper and more complex formations, the encountered geological strata exhibit increased rock strength, higher abrasiveness, and reduced drillability [2]. These challenging subsurface conditions intensify harmful drill string vibrations, including axial, torsional, and lateral modes [3,4,5]. Among these, stick–slip vibrations and bit bounce are primary contributors to premature bit failure and reduced ROP, thereby posing significant risks to both drilling safety and operational efficiency [6]. Furthermore, in deep well environments, drill string vibrations dissipate energy originally intended for rock fragmentation, reducing the effectiveness of Weight on Bit (WOB) and Torque on Bit (TOB) applications and ultimately increasing drilling costs [7].

In response to these challenges, various mitigation strategies have been proposed to suppress drill string vibrations. Among them, percussive drilling technologies, categorized into axial percussive, torsional percussive, and compound percussive drilling, have emerged as promising solutions. These methods utilize an impact tool to convert hydraulic energy into periodic mechanical impacts, which are transmitted directly to the drill bit. By introducing controlled impulses, percussive drilling disrupts sustained vibration modes such as stick–slip while preserving the high rotational speed of the PDC bit. Consequently, this approach not only mitigates harmful vibrations but also improves rock-breaking efficiency and enhances ROP [8,9,10].

Prior research has predominantly focused on enhancing rock-breaking efficiency under compound impact loading. Utilizing numerical simulations and laboratory experiments, scholars have examined the behavior of PDC cutters and drill bits subjected to axial–torsional impacts, including crack propagation patterns [10,11], cuttings formation mechanisms [12,13,14], rock damage characteristics [2,12,15], and thermal responses of the cutters [13]. These studies collectively demonstrate that compound percussive drilling significantly improves rock fragmentation efficiency and mechanical penetration rate by optimizing energy transfer.

In addition to examining the rock-breaking mechanisms of impact loading, researchers have extensively investigated the dynamic response of the drill string under impact conditions, aiming to evaluate its influence on drilling safety and energy transmission efficiency. A comprehensive understanding of drill string dynamics is essential for analyzing bit vibration behavior, which directly affects overall drilling performance.

Early studies primarily focused on the effects of axial impact loading. Kreisle and Vance applied a linear damping wave equation to analyze the impact of shock subs, revealing that vibration attenuation is achieved through phase angle modulation rather than alterations in natural frequency [16]. This linear framework was later refined by Skaugen et al., who incorporated structural damping into a free vibration model. Their findings demonstrated that axial impact loads exceeding 3–4 Hz significantly suppress vibrations, consistent with field observations [17]. To capture the nonlinear interactions inherent in drilling processes, more advanced numerical models were subsequently developed. Parfitt and Abbassian introduced viscous damping and bit–rock nonlinearity into a finite difference framework, while Ghasemloonia et al. extended this approach to model axial–lateral coupling using a vibration generator [18,19]. Concurrently, experimental validation efforts advanced as well; for instance, Newman et al. confirmed through laboratory testing that axial oscillators effectively suppress stick–slip vibrations, thus supporting theoretical predictions [20]. Recent studies have shifted focus toward parameter optimization. Li et al. developed dynamic models of drilling systems using constant depth-of-cut (DOC) and state-dependent time-delay methods, quantitatively evaluating how variations in impact frequency and amplitude can induce system resonance [21].

Beyond axial loading, torsional impacts have also been investigated as a means of vibration mitigation. Li et al. proposed a mechanical model incorporating energy dissipation mechanisms in the drill pipe to quantify torsional impact dynamics, demonstrating its effectiveness in reducing stick–slip, which was later validated through simulations calibrated with field data [22]. Building on this, Huang, Mao, and Tian et al. developed four-degree-of-freedom models to analyze the suppression of stick–slip instabilities under varying torsional impact parameters such as frequency and amplitude [23,24,25].

While these studies affirm the effectiveness of isolated axial or torsional impact loading, the coupled axial–torsional vibration modes intrinsic to CPD remain largely unexplored. This knowledge gap constrains efforts to optimize energy transfer mechanisms in complex geological formations, representing a critical limitation—particularly in light of CPD’s demonstrated advantages in enhancing ROP.

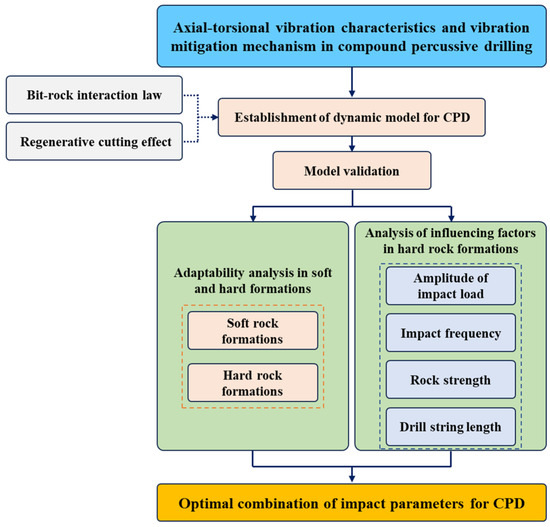

This study aims to elucidate the mechanisms of vibration reduction and ROP enhancement in CPD. To achieve this objective, this paper is organized as follows: First, an MDOF dynamic model of the drill string system is developed, integrating a compound impact tool and regenerative cutting effects of bit–rock interactions, and the model is validated against field test data. Then, the vibration characteristics of the drill bit are simulated under both soft and hard rock formation conditions, and the adaptability of CPD is assessed by correlating ROP improvements and vibration suppression effects. Finally, a parametric sensitivity analysis is conducted to evaluate the influence of axial and torsional impact amplitudes, impact frequency, rock strength, and drill string length on bit stability. The findings of this study provide a theoretical foundation for optimizing the design and parameter selection of CPD operations. The structure flowchart of this article is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure flowchart of this article.

2. Modeling

2.1. Description of the CPD System

Rotary drilling is extensively employed in oil and gas development operations. The system comprises a drilling rig, drill pipes, BHA (with drill collars, stabilizers, and speed-up drilling tools), and a drill bit. During drilling, the drill string is suspended from a traveling hook and rotated by the top rotary system. Subsequently, this rotation enables the drill bit to break the formation rock through the combined action of WOB and TOB, both of which are transmitted through the drill string.

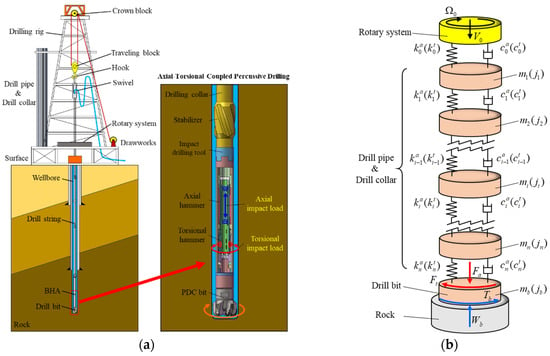

Figure 2a illustrates a typical CPD system. In this configuration, an impact tool is positioned above the bit, modifying the conventional rotary drilling setup. The tool converts high-pressure fluid energy into the reciprocating motions of axial and torsional hammers. These hammers strike an anvil, generating periodic axial–torsional impacts on the bit, which helps mitigate drill system vibrations and enhances rock-breaking efficiency.

Figure 2.

Schematic and mechanical model of percussive drilling system: (a) Simplified schematic; (b) Mechanical model.

2.2. Model Derivation

Figure 2b presents the mechanical model of the CPD system. In this model, the drill string is represented using a lumped mass approach, where vibrations are characterized by discrete mass elements interconnected with stiffness and damping components. The drill string is discretized into n + 1 interconnected mass segments, connected by spring-damper systems. Specifically, elements 1 through n represent the drill pipes and collars, while element n + 1 models the drill bit. To improve computational efficiency, the following assumptions are made: vertical wellbore geometry with perfect drill string–wellbore alignment; negligible lateral displacement of the drill string; the effects of pipe joints are ignored; homogeneous rock properties that are independent of depth.

Under the action of a constant axial velocity and rotational speed imposed by the drive system, the motion of the top drill string can be described by the following boundary equation:

The dynamic behavior of the middle element of the drill string is governed by the following expression:

where i = 2, 3,…n. The mechanical properties of the drill string elements are intrinsically related to their structural parameters and can be calculated using the following expressions:

At the bit–rock interface, where coupled axial–torsional impact loads from compound percussive tool are applied, the dynamic response is governed by the nonlinear interaction law, which can be expressed as

By coupling Equations (1)–(4), the coupled axial–torsional dynamic governing equations for the drill string system can be derived:

In Equation (5), the mass, moment of inertia, stiffness, and damping matrix of the axial and torsional motion are as follows:

The , , and denote the vectors representing external force, self-weight, and external torque acting on the drill string system. The expressions for these vectors are as follows:

2.3. Bit–Rock Interaction Model

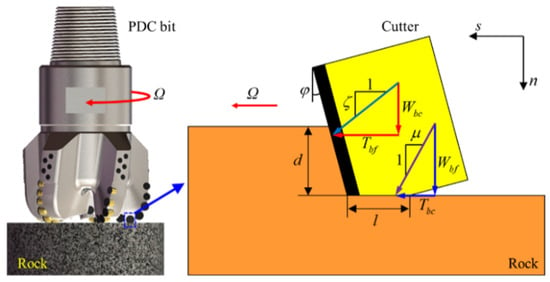

In the interaction between the drill bit and the formation rock, the axial and rotational motions of the bit are inherently coupled. Such coupling involves both the downward penetration of the bit into the rock under WOB and the rotational shear of the rock induced by TOB. These complex interactions significantly influence the dynamic response of the drill string system. This paper employs the well-established bit–rock interaction model developed by Detournay and Defourny [26], which effectively divides the interaction process into cutting and friction processes, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the load on a single cutter during the bit–rock interaction.

As shown in Figure 3, the axial force and torque in Equation (8), generated through bit–rock interaction, consist of two physically distinct mechanisms. The cutting component originates from the resistance on the cutter’s front surface during rock-breaking, while the friction component results from the contact between the cutter’s wear flat and the rock surface. The total axial force and torque acting on the drill bit can be expressed mathematically as

where the subscripts and represent cutting and friction processes, respectively. The cutting and the friction components are modeled as follows:

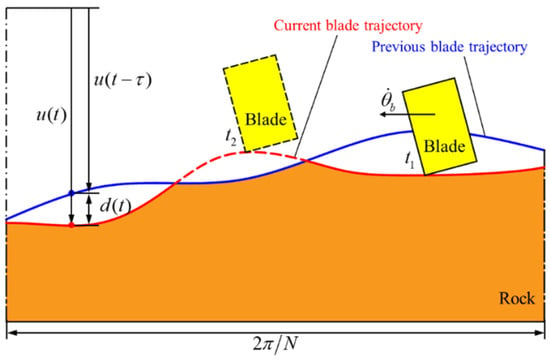

In Equation (10), the DOC is defined as the differential displacement between the axial positions of successive blade passages along the bottomhole trajectory, as visualized in Figure 4. This schematic depicts the motion trajectory of two adjacent blades on the unfolded rock surface during rock-breaking process. Under stable drilling conditions, the bit penetrates at a constant rate, and the DOC remains positive, allowing continuous rock removal. However, during instances of irregular bit motions, such as bit bounce, stick–slip vibrations, or reverse rotation, the DOC may become negative. As shown in Figure 3, the bit experiences bit bounce at t2 and retracts axially, leading to anomalous negative DOC values. These anomalies violate the kinematic assumptions of Equation (10), as the formula presumes unidirectional cutting without bit bounce. Consequently, the standard axial-force/torque calculation fails to capture transient bit–rock interactions. To address discontinuous contact states, we reformulate the bit–rock interaction using non-smooth functions:

in which , , and represent the Ramp, Heaviside, and Sign functions, respectively. These functions are employed to characterize the non-smooth dynamics inherent in the drill bit’s motion, formally defined as

Figure 4.

Diagram of the unfolding trajectory of the blade along circumference during the bit–rock interaction.

The DOC of the bit varies continuously and can be calculated using the following delay equation:

The delay time in Equation (13) is a state-dependent time-delay variable representing the time the previous blade takes to reach the current angular position. This delay time can be calculated using the following implicit function:

3. Model Validation

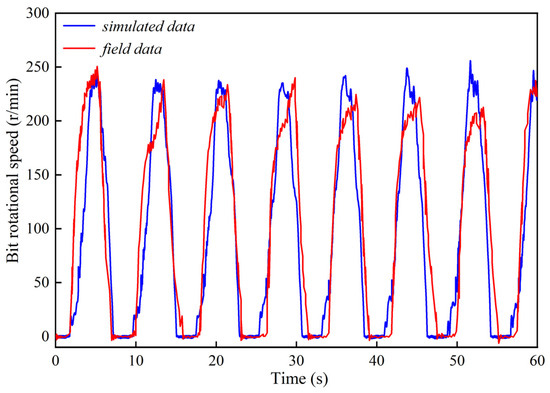

To analyze the vibration behavior of the drill system under compound impact loads, the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method was employed to solve Equations (1)–(14). Due to the absence of field measurement data specific to CPD, this paper adopts an indirect validation strategy. We first validate the consistency between the degenerated conventional drilling model and the field data from Ritto et al. [27] to ensure the accuracy of the fundamental dynamic parameters. On this basis, the dynamic analysis of CPD is conducted by superimposing theoretical impact loads. The drill string configurations utilized in the field tests and simulations are summarized in Table 1, and the drill string element size is set to 25 m during the simulation [28]. A comparison of the measured and simulated rotational speeds of the bit is presented in Figure 5.

Table 1.

Drill string parameters in field operation and numerical simulation.

Figure 5.

Comparison between the simulated data of this model and the field data in the literature.

As shown in Figure 5, the drill bit undergoes cyclic stick–slip behavior, characterized by peak rotational speeds of 249 r/min during the slip phase, over twice the drive speed of 120 r/min, then abrupt drops to zero during the stick phase. The cycle period remains stable, corresponding to a vibration frequency of approximately 0.13 Hz. Furthermore, waveform fluctuations in different slip stages indicate inherent uncertainties in bit–rock interactions. Comparative analysis demonstrates strong agreement between the model’s predicted rotational dynamics and field measurements [27], particularly in capturing rapid oscillations during the stick phase. These results validate the accuracy and reliability of the proposed theoretical model and numerical approach for simulating drill string dynamics.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Adaptability Analysis in Soft and Hard Formations

This section calibrates the bit’s vibration characteristics under both conventional rotary (non-impact) drilling and CPD conditions, evaluating its adaptability across soft and hard rock formations. The simulation parameters are listed in Table 2. To quantify vibration severity, this research employs the drill string vibration classification standard developed by Baker Hughes [29], as detailed in Table 3. This methodology incorporates several quantitative parameters for evaluating different vibration modes. For axial vibration levels, the index Sa is derived from the root mean square values of the drilling string’s axial acceleration. According to this index, axial vibration intensities are classified across an eight-tier scale, with higher numerical grades corresponding to increasingly intense vibration states. Similarly, torsional vibration levels are categorized into eight grades, using two evaluation indexes: the first parameter (S1) represents the ratio of the fluctuation amplitude of the drill bit speed to twice the surface drill string speed; the second indicator (S2) quantifies the percentage of time the system spends in backward whirl.

Table 2.

Parameters in the simulation.

Table 3.

Baker Hughes drill string vibration on grading standards.

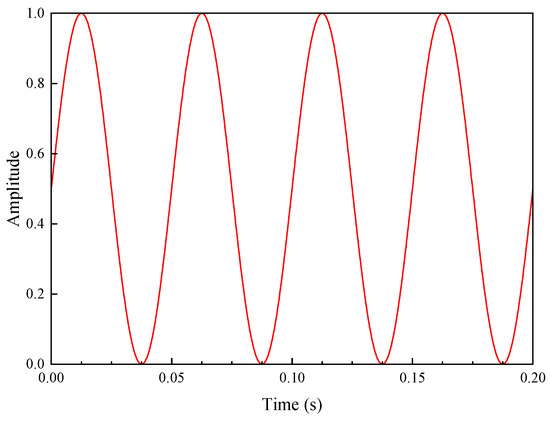

4.1.1. Drilling in Soft Rock Formations

In soft rock formations, the intrinsic specific energy and maximum contact stress are set to 50 MPa, with other parameters maintained at constant values (see Table 2). The CPD tool generates the following dynamic loading parameters: an axial impact load amplitude of 5 kN, a torsional dynamic amplitude of 1000 N·m, and an impact frequency of 20 Hz. The impact loads are applied following the sinusoidal amplitude profile shown in Figure 6. Through analysis of the temporal variations in speed and displacement, the dynamic response characteristics of the bit were systematically compared between non-impact drilling and CPD. Figure 7 and Figure 8 demonstrate the performance contrasts in soft rock formations.

Figure 6.

Loading curve of compound impact load (f = 20 Hz).

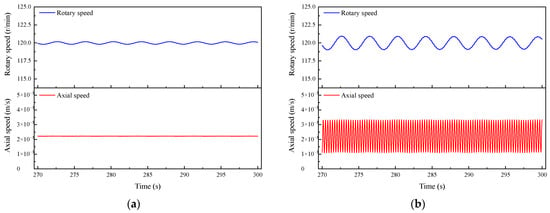

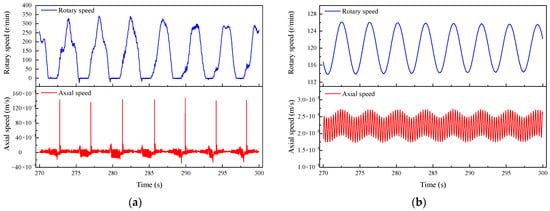

Figure 7.

Curves of axial speed and rotational speed of the drill bit for different drilling methods in soft rock formation: (a) Non-impact drilling; (b) Compound impact drilling.

Figure 8.

Variation curves of bit displacement in soft rock formation with different drilling methods: (a) Axial displacement; (b) Angular displacement.

As illustrated in Figure 7a, during non-impact drilling in soft rock formations, the axial velocity (0.00222 m/s) and rotational speed (120 r/min) at the bit closely match those at the top of the drill string, indicating stable drilling conditions under the applied WOB and TOB. In contrast, Figure 7b shows that introducing axial–torsional coupled impact loading leads to noticeable dynamic responses: rotational speed fluctuates by 11.3% (113.19–126.79 r/min), and axial velocity varies between 0.001 and 0.0034 m/s with high-amplitude oscillations. Despite remaining within safety thresholds (Sa = 0.079 g, S1 = 0.008), these intensified vibrations may pose long-term risks such as accelerated bit fatigue, inconsistent cutting, and compromised wellbore stability.

Figure 8 further reveals that compound impacts induce stepwise increases in axial displacement, resulting from transient velocity fluctuations. However, a comparison of cumulative axial and angular displacements over equal time intervals shows no significant difference between conventional and impact drilling. This suggests that in soft formations, the cutting depth produced under WOB is already substantial. On this basis, the additional impact load does not significantly alter the rock failure mode assumed in the model, leading to a marginal diminishing effect in the volume of rock broken per unit of energy input.

4.1.2. Drilling in Hard Rock Formations

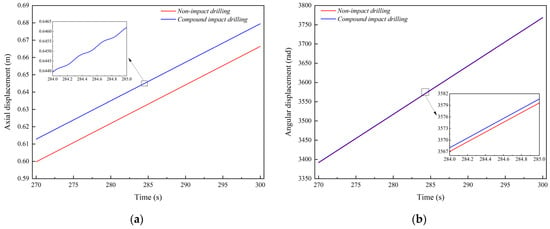

In numerical simulations of hard rock drilling scenarios, the intrinsic specific energy and maximum contact stress were configured at 120 MPa, with other parameters held constant. The temporal evolution of bit dynamics was systematically investigated, with Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrating the time-domain characteristics of axial–torsional coupled vibrations under different drilling methodologies.

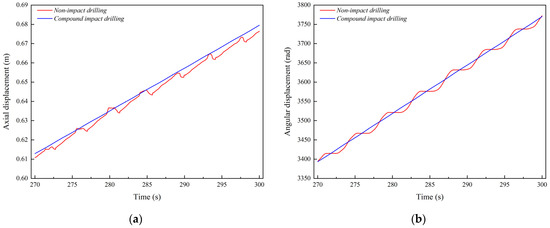

Figure 9.

Variation curves of axial speed and rotary speed of bit in hard rock formation with different drilling methods: (a) Non-impact drilling; (b) Compound impact drilling.

Figure 10.

Variation curves of bit displacement in hard rock formation with different drilling methods: (a) Axial displacement; (b) Angular displacement.

As shown in Figure 9a, under conventional non-impact drilling in hard rock formations, the drill bit exhibits severe stick–slip vibrations, accompanied by reverse rotation and bit bounce. During the torsional stick phase, bit rotation nearly halts, with the rotational speed oscillating around zero. Simultaneously, the system enters an axial stick phase, where axial velocity fluctuates at high frequencies (±0.01 m/s) but fails to achieve effective rock penetration. The subsequent release of elastic energy from the drill string initiates the slip phase, causing the rotational speed to spike to 341.78 r/min, approximately 2 to 3 times the top drive speed (120 r/min), before gradually decaying. Correspondingly, the axial velocity reaches a peak of 0.15 m/s, followed by reduced oscillations between −0.007 and 0.009 m/s. Vibration severity assessments yield Sa = 1.90 g (moderate axial vibrations) and S1 = 1.52 (severe torsional vibrations), indicating a hazardous drilling condition. In contrast, Figure 9b demonstrates that axial–torsional coupled impact loading effectively suppresses vibrations, constraining axial velocity to 0.0018–0.0027 m/s and rotational speed to 113.81–126.11 r/min. This approach completely eliminates stick–slip phenomena, reduces vibration severity to class 0, and enables continuous rock fragmentation through controlled energy delivery.

As evidenced in Figure 10, non-impact drilling induces stepwise accumulation of bit axial and angular displacements due to cyclic stick–slip vibrations. These severe vibrations cause the axial displacement response curve to alternate between rising and falling, confirming periodic bit–borehole separation and bit bounce. These violent oscillations generate detrimental cutter-rock impact forces that accelerate cutter degradation. Conversely, compound impact loading establishes stable bottomhole contact, achieving 0.0667 m continuous penetration over 30 s compared to 0.0637 m in conventional drilling. Numerical calculation results indicate that CPD has the theoretical potential to increase ROP by approximately 4.6% under the simulated conditions. The results suggest that adding an extra compound impact load during drilling in hard rock formations can effectively suppress the stick–slip vibrations, optimize stress distribution at bit–rock interface, and synergistically improve both drilling safety and operational efficiency.

4.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors in Hard Rock Formations

The preceding analysis demonstrates that CPD exhibits distinct formation adaptability, effectively suppressing vibrations and enhancing the ROP in hard rock formations, while showing limited compatibility with soft rock formations. Key parameters—including axial–torsional impact amplitude, the intrinsic specific energy of the rock, and drill string length—play a critical role in determining the effectiveness of this technology in hard rock drilling. Accordingly, it is essential to systematically investigate the influence of these parameters on the dynamic response of the drill bit. Based on the established simulation model, this section explores the underlying mechanisms governing the effects of these parameters on bit vibration characteristics.

4.2.1. Axial Impact Load Amplitude

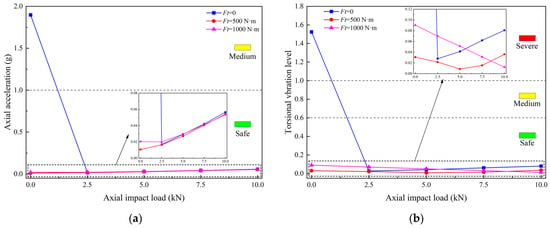

In this subsection, we explore the effect of axial dynamic amplitude on the bit vibration characteristics. The simulation parameters are consistent with those employed in Section 4.1.2. The axial impact load amplitude (Fa) was varied across five levels: 0, 2.5 kN, 5 kN, 7.5 kN, and 10 kN. To evaluate coupled vibration responses, these axial loading conditions were combined with three torsional impact levels (Ft = 0, 500 N·m, 1000 N·m).

The variation of axial vibration acceleration and torsional vibration level with respect to loading conditions is illustrated in Figure 11a,b, respectively. As shown in the figures, the application of dynamic loading significantly reduces the vibration intensity of the drill bit, with the axial vibration decreasing from a moderate to a safe level and the torsional vibration transitioning from severe to safe. These results indicate that both axial and torsional impact loads contribute positively to the suppression of stick–slip vibrations, and all tested impact-assisted drilling modes effectively eliminate this detrimental phenomenon.

Figure 11.

Effect of axial dynamic amplitude on vibration characteristics: (a) Axial displacement; (b) Angular displacement.

Figure 11a further demonstrates that under safe drilling conditions, with a constant torsional impact load, the axial acceleration of the drill bit increases as the axial dynamic amplitude increases. Meanwhile, Figure 11b reveals that the torsional vibration level exhibits distinct trends under different loading conditions. Under pure axial impact loading (Ft = 0), the torsional vibration index S1 increases proportionally with the axial impact load. When a torsional impact load of 500 N·m is applied, the index S1 exhibits a non-monotonic trend, initially decreasing and then increasing as the axial impact amplitude rises. This increase is likely attributed to the superposition of excessive impact energy. Conversely, with a torsional impact load of 1000 N·m, S1 decreases consistently with increasing axial impact amplitude. Moreover, the simulation results confirm that CPD is more effective in suppressing torsional vibrations than pure axial impact drilling. The optimal dynamic load combinations identified are as follows: an axial impact load amplitude of 5 kN with a torsional dynamic load of 500 N·m, or an axial impact load amplitude of 10 kN with a torsional dynamic load of 1000 N·m.

4.2.2. Torsional Impact Load Amplitude

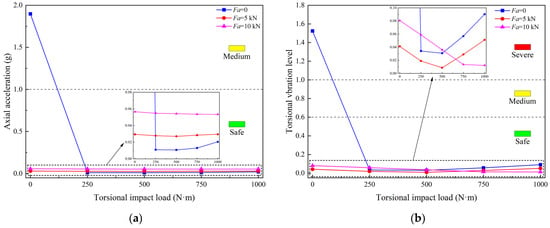

In this subsection, numerical simulations were conducted across five torsional dynamic amplitudes: 0, 250 N·m, 500 N·m, 750 N·m, and 1000 N·m. The analysis specifically investigates the effects of these torsional loading conditions under three axial dynamic load configurations: 0 kN, 5 kN, and 10 kN. The corresponding simulation results are presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Effect of torsional dynamic amplitude on vibration characteristics: (a) Axial displacement; (b) Angular displacement.

As illustrated in Figure 12a, under safe drilling conditions, variations in torsional impact load have a negligible effect on the axial acceleration of the drill bit. However, comparative analysis reveals that CPD produces higher axial acceleration than pure torsional impact drilling. The torsional vibration index results shown in Figure 12b indicate that when the axial impact load amplitude is below the 5 kN threshold, the torsional vibration index initially decreases and subsequently increases with increasing torsional impact load amplitude. Moreover, the torsional impact load corresponding to the inflection point of the curve increases with rising axial dynamic load. In contrast, at an axial impact load of 10 kN, S1 decreases monotonically with increasing torsional dynamic amplitude. These findings suggest that during CPD, the optimal torsional dynamic amplitude must increase proportionally with higher axial impact loads to simultaneously achieve improved drilling efficiency and effective vibration suppression. This coupled loading mechanism is consistent with the conclusions drawn in Section 4.2.1.

4.2.3. Impact Frequency

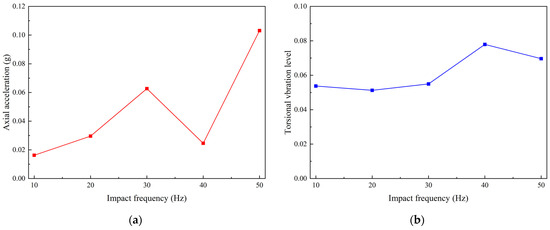

In this subsection, we evaluate the frequency-dependent vibration response of the bit under compound percussive loading. Parameters such as impact load amplitude and rock intrinsic specific energy remain constant, while the impact frequency is set to 10 Hz, 20 Hz, 30 Hz, 40 Hz, and 50 Hz. The resultant axial acceleration and the torsional vibration level of the bit are plotted in Figure 13a,b, respectively. It can be observed that, under the compound percussive loading with different impact frequencies, the stick–slip vibration at the drill bit disappears, and the drill bit remains within a safe operational range. The bit axial vibration acceleration follows an N-shaped curve with respect to the impact frequency; the axial vibration acceleration initially increases, then decreases as the impact frequency reaches 40 Hz, and increases again as the frequency continues to rise. In contrast, the torsional vibration level of the bit first increases and then decreases, with the inflection point appearing at the impact frequency of 40 Hz. For optimal vibration mitigation, the impact frequency of CPD should be maintained within the range of 10–30 Hz. This range balances lower axial acceleration and torsional stability, avoiding resonance-induced amplification.

Figure 13.

Effect of impact frequency on vibration characteristics of drill bit: (a) Axial acceleration; (b) Torsional vibration leve.

4.2.4. Rock Strength

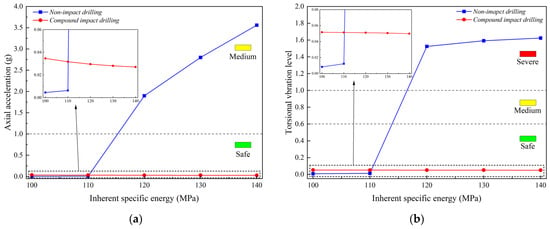

This subsection presents a comparative analysis of the bit vibration characteristics under varying rock strengths for both non-impact drilling and CPD. Numerical simulations were performed across five levels of intrinsic specific energy, ranging from 100 MPa to 140 MPa in 10 MPa increments. The effects of rock strength on vibration behavior under the two drilling modes are illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Effect of rock strength on vibration characteristics under different drilling modes: (a) Axial displacement; (b) Angular displacement.

As shown in the figure, during non-impact drilling, both axial and torsional vibration intensities progressively increase with rising rock strength. Specifically, when drilling formations with intrinsic specific energy below 120 MPa, the bit operates within safe vibration thresholds. However, once the rock strength exceeds this critical value (120 MPa), vibration levels escalate into the medium axial and severe torsional regimes, thereby posing significant risks to drilling safety. In contrast, the application of CPD exhibits clear advantages, maintaining bit stability within safe operational limits across the entire range of tested rock strengths. Interestingly, both the axial acceleration and torsional vibration level decrease as rock strength increases under CPD conditions. Nevertheless, for formations with intrinsic specific energy below 120 MPa, the vibration indices under CPD are marginally higher than those observed in non-impact drilling. These results indicate that the vibration suppression capability of CPD becomes increasingly pronounced with higher rock strength, further underscoring its suitability for hard rock drilling applications.

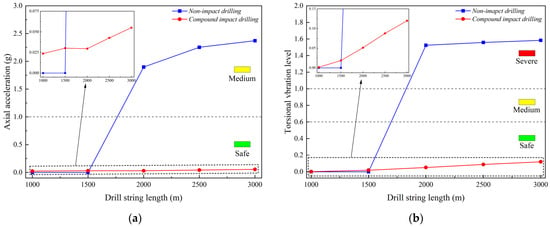

4.2.5. Drill String Length

In this subsection, the effect of drill string length on bit vibration characteristics is examined, with all other parameters held constant. The drill system configuration consists of a fixed 200 m drill collar section, combined with variable-length drill pipes ranging from 800 m to 2800 m. The vibration levels corresponding to these simulated drill string lengths are presented in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Effect of drill string length on vibration characteristics under different drilling modes: (a) Axial displacement; (b) Angular displacement.

As depicted in the figure, vibration intensity shows a clear positive correlation with drill string length. Both vibration modes experience a marked intensification as the length of the drill string increases across all drilling methods. During non-impact drilling, the bit remains within a safe vibration range when the drill string length is less than 1500 m. However, as the drill string length exceeds 2000 m, bit vibrations gradually escalate to moderate and severe levels. In contrast, CPD effectively eliminates stick–slip vibrations, maintaining safe vibration levels irrespective of depth. Notably, when the drill string length is below 1500 m, the vibration indices for CPD are slightly higher than those observed under non-impact drilling conditions. This suggests that the vibration suppression effect of CPD improves with increasing drill string length. Specifically, as the drill string length increases, the ability of CPD to mitigate vibrations becomes more pronounced.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In this study, a computational dynamic model of an MDOF drillstring system integrated with a CPD tool is proposed to investigate the mechanisms of bit vibration reduction during percussive drilling. The research indicates the following:

(1) In soft rock formations, the application of axial–torsional coupled impact loads induces detrimental axial and torsional vibrations, suggesting that CPD is less suitable for soft rock drilling. In hard rock formations, the application of axial–torsional coupled impact loads effectively suppresses stick–slip vibrations and improves the stress distribution on the bit, demonstrating enhanced penetration efficiency while reducing harmful vibrations.

(2) Axial–torsional coupled impact provides superior vibration suppression compared to single-axis impact. The optimal axial impact load increases proportionally with the torsional impact load. Specifically, when the torsional impact load amplitudes are 500 N·m and 1000 N·m, the optimal axial impact load amplitudes are 5 kN and 10 kN, respectively. In addition, maintaining the impact frequency within 10–30 Hz can achieve an optimal vibration reduction effect.

(3) The vibration mitigation advantages of CPD become more pronounced under high rock strength and long drill string conditions, confirming its potential for efficient drilling in deep, hard formations.

In future work, we will further investigate the influence of lateral coupling effects, as well as factors such as wellbore dogleg severity and heterogeneous formations, on the vibration mitigation performance of CPD. Furthermore, it is important to note that the conclusions presented in this study are derived from numerical simulations. While the model accounts for key nonlinear dynamic characteristics, uncertainties in actual geological formations and the complexity of the tool system may influence the final outcomes. Consequently, the exact magnitude of ROP enhancement requires further verification through subsequent laboratory experiments and field tests.

Author Contributions

Writing—review and editing, W.W.; software, W.W.; investigation, B.G.; funding acquisition, G.L.; methodology, C.Z.; validation, T.C.; supervision, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23B2081, 52227804, U22B2072) and Basic Scientific Research Operating Expenses for Municipal Universities (321000546325001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPD | Compound percussive drilling |

| WOB | Weight on bit |

| TOB | Torque on bit |

| ROP | Rate of penetration |

| DOC | Depth of cutter |

| MDOF | Multi-degree-of-freedom |

Nomenclature

The following nomenclature are used in this manuscript:

| Mass of the i-th drill string element | Axial force on the bit | ||

| Mass of the drill bit | Torque on the bit | ||

| Axial spring stiffness of the top drive system | Axial impact load of the impact drilling tool | ||

| Axial damping of the top drive system | Torsional impact load of the impact drilling tool | ||

| Axial spring stiffness between elements i and i + 1 | Total length of drill pipe | ||

| Axial damping between elements i and i + 1 | Total length of drill collar | ||

| Axial displacement of the i-th element | Outer diameter of the i-th element | ||

| Axial displacements of the drill bit | Inner diameter of the i-th element | ||

| Rotational inertia of the i-th element | The length of the i-th element | ||

| Rotational inertia of the drill bit | Rayleigh damping coefficients | ||

| Torsional spring stiffness of the rotary system | Rock intrinsic specific energy | ||

| Torsional damping of the rotary system | Constant related to the cutter face inclination | ||

| Torsional spring stiffness between elements i and i + 1 | Depth of cut | ||

| Torsional damping between elements i and i + 1 | Number of blades on the drill bit | ||

| Angular displacement of the i-th element | Contact stress at the wear-flat rock interface | ||

| Angular displacement of the drill bit | Frictional coefficient between cutter and rock | ||

| Axial velocity of the top drive system | The length of the cutter wear flat | ||

| Rotation velocity of the top drive system | Geometric parameter of the drill bit | ||

| Mass matrix for the axial motion | Acceleration of gravity | ||

| Stiffness matrix for the axial motion | Buoyancy coefficient of drilling fluid | ||

| Damping matrix for the axial motion | Young’s elastic modulus | ||

| Rotational inertia matrix for the torsional motion | Poisson’s ratio | ||

| Stiffness matrix for the torsional motion | Density of drill string material | ||

| Damping matrix for the torsional motion | Density of drill mud | ||

| Time step |

References

- Cheng, Z.; Li, G.; Huang, Z.; Sheng, M.; Wu, X.; Yang, J. Analytical modelling of rock cutting force and failure surface in linear cutting test by single PDC cutter. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 177, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Zhang, T.; Tian, Z.F.; Zheng, Y.M.; Yang, Z.M. Simulation on compound percussive drilling: Estimation based on multidimensional impact cutting with a single cutter. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 3833–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, T.; Germay, C.; Detournay, E. Self-excited stick–slip oscillations of drill bits. Comptes Rendus Mécanique 2004, 332, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritto, T.G.; Escalante, M.R.; Sampaio, R.; Rosales, M.B. Drill-string horizontal dynamics with uncertainty on the frictional force. J. Sound Vib. 2013, 332, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalyshen, Y. Understanding root cause of stick–slip vibrations in deep drilling with drag bits. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2014, 67, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-López, E.M.; Cortés, D. Avoiding harmful oscillations in a drillstring through dynamical analysis. J. Sound Vib. 2007, 307, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemloonia, A.; Geoff Rideout, D.; Butt, S.D. A review of drillstring vibration modeling and suppression methods. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 131, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksala, T. 3D numerical modelling of thermal shock assisted percussive drilling. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 128, 103849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Tang, L. Development of a high-frequency torsional impact generator for improving drilling efficiency. J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2013, 228, 1968–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Zha, C.; Lian, W. Numerical simulation study on rock-breaking process and mechanism of compound impact drilling. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 3137–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Yuan, G.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y.; Ni, H.; Ren, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z. Simulation research on rock-breaking performance of PDC cutter under composite impact based on discrete element method. In Proceedings of the 57th U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, Atlanta, GA, USA, 25–28 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Zha, C.-Q.; Li, J.; Liu, G.-H.; Guo, B.-Y. Numerical simulation of rock-breaking and influence laws of dynamic load parameters during axial-torsional coupled impact drilling with a single PDC cutter. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 1806–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, G.H.; Li, J.; Zha, C.Q.; Lian, W.; Gao, R.Y. Numerical investigation on rock-breaking mechanism and cutting temperature of compound percussive drilling with a single PDC cutter. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 2364–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Zeng, Y.J.; Zhu, X.H.; Ding, S.D. Mechanism of rock breaking under composite and torsional impact cutting. J. China Univ. Pet. 2020, 44, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Shi, H.; Li, G.; Chen, Z.; Li, X. Numerical simulation of the energy transfer efficiency and rock damage in axial-torsional coupled percussive drilling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisle, L.F.; Vance, J.M. Mathematical Analysis of the Effect of a Shock Sub on the Longitudinal Vibrations of an Oilwell Drill String. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1970, 10, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaugen, E.; Kyllingstad, A.; Aarrestad, T.V.; Tonnesen, H.A. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of Vibrations in Drill Strings Incorporating Shock Absorbers. In Proceedings of the 12th World Petroleum Congress, Houston, TX, USA, 26 April–1 May 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, S.H.L.; Abbassian, F. A Model for Shock Sub Performance Qualification. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 28 February–2 March 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemloonia, A.; Rideout, D.G.; Butt, S.D.; Hajnayeb, A. Elastodynamic and finite element vibration analysis of a drillstring with a downhole vibration generator tool and a shock sub. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2015, 229, 1361–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.; Burnett, T.; Pursell, J.; Gouasmia, O. Modeling the Affect of a Downhole Vibrator. In Proceedings of the SPE/ICoTA Coiled Tubing & Well Intervention Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 31 March–1 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Guo, J.Y.; Liu, D.W. Dynamics of resonance impact drilling based on constant depth-of-cut and state-dependent time delay models. J. China Univ. Pet. 2024, 48, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.Q.; Bi, F.Q.; Li, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.Y. Dynamic characteristics of steady torsional impact drilling and its field application. J. China Univ. Pet. 2019, 43, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xie, D.; Xie, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; He, L. Investigation of PDC bit failure base on stick-slip vibration analysis of drilling string system plus drill bit. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 417, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.J.; Ma, M.Y.; Liu, L.P.; Zhang, W.; Chen, C.Y. Influence of torsional impactor on stick-slip vibration of drillstring. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field E 2022, 29, 545–551. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.L.; Zhou, S.Q.; Yang, Y.L. Viscosity reduction analysis of the sliding mode control of a drill string system with a torsional vibration tool. J. Vib. Shock. 2020, 39, 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- Detournay, E.; Defourny, P. A phenomenological model for the drilling action of drag bits. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1992, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritto, T.G.; Aguiar, R.R.; Hbaieb, S. Validation of a drill string dynamical model and torsional stability. Meccanica 2017, 52, 2959–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Long, X.; Zheng, X.; Meng, G.; Balachandran, B. Spatial-temporal dynamics of a drill string with complex time-delay effects: Bit bounce and stick-slip oscillations. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 170, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H. Analysis and Development of Algorithms for Identification and Classification of Dynamic Drillstring Dysfunctions. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Leoben, Leoben, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.