Abstract

Introduction: Incomplete polymerization of in vivo composite resins (CR) poses a significant problem, with monomer-to-polymer conversion rates ranging from around 60 to 75%. Furthermore, oxygen exposure hampers polymerization in the surface layers. This research aims to evaluate the autophagy-inducing potential of three types of CRS and to explore the role of the Akt/mTOR–autophagy–apoptosis crosstalk in composite resin-induced autophagy. The study uses human gingival fibroblasts and three composite materials (M1 and M2, which are 3D printed, and M3, which is milled). Materials and Methods: SEM analysis was performed on the dental materials, and cells kept in contact for 24 h were subjected to tests including the following: MTT, LDH, NO, immunological detection of proteins involved in autophagy and apoptosis, as well as immunofluorescence tests (Annexin V and nucleus; mitochondria and caspase 3/7; detection of autophagosomes). Results: The results showed statistically significant decreases in cell viability with M1 and M2, linked to increases in cytotoxicity and oxidative stress (LDH and NO). Using multiplex techniques, significant increases in glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3b) protein were observed in both M1 and M2; a decrease in mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) expression was noted in M1 and M3. Immunofluorescence tests revealed an increase in Annexin V across all materials studied, and an increase in autophagosomes in M1 and M2, whereas a decrease was observed in M3. Conclusions: The relationship between apoptosis and autophagy is highly complex, indicating they may occur sequentially, coexist, or be mutually exclusive. Understanding this complex interplay can help in designing new 3D-printing protocols and monomer compositions to prevent autophagy imbalance.

1. Introduction

Edentulism impacts both well-being and quality of life [1,2,3], and despite advances in prevention, it remains a significant challenge for dental professionals. Treatment options include full dentures, implant-retained overdentures, and implant-supported fixed restorations [1,2,3]. For partial tooth loss, temporary solutions involve single-tooth restorations or multi-unit bridges, which can be removable or fixed [1,2,3]. All these restorations can be manufactured using digital workflows [4,5,6]. In prosthetic dentistry, composite resins (CR) are widely used and have recently been incorporated into 3D-printing technologies.

Combining all desired properties—such as mechanical strength, antibacterial effects, bioactivity, and biocompatibility—into a single composite resin remains a challenge [7].

Resin composite dental materials can release certain components into the oral environment, potentially causing harmful biological effects on the gingiva [8,9]. A significant issue is the incomplete polymerization of in vivo composite resins. Research indicates that the monomer-to-polymer conversion rate is approximately 60–75% [10,11]. Another issue with using composites is that oxygen exposure inhibits polymerization in the surface layers. If this inhibition layer is not removed, polishing can cause the release of monomers or degradation products, depending on the thickness of the unpolymerized layer [12,13,14].

Additionally, it is believed that numerous other unidentified compounds are degradation products of composite additives such as inhibitors, catalysts, accelerators, and UV stabilizers. Prior research has indicated that, in particular, the dimethacrylate polymer contains significant amounts of unsaturated monomers in the final product [15,16,17,18,19]. Furthermore, di- and monomethacrylates hydrolyze to methacrylic acid and alcohols at neutral pH. Methacrylic acid is probably released from the degradation of dimethacrylates bound in the matrix with only one end of the molecule. In vitro studies with methacrylates have confirmed that their cytotoxicity is concentration-dependent, and they are toxic to osteoblasts and periodontal cells [8,20,21].

Both the printing technique and the type of printer can influence the polymerization rate, the amount of residual monomer, and the external porosity of the polymerized mass according to studies on fibroblasts and mechanical properties of the restorations [22,23,24,25].

CRs are often used for temporary prosthetic devices. However, resin monomers released from polymerized restorative composites can reduce cell viability and pose toxicity risks to oral eukaryotic cells, creating a persistent medical concern [26]. Additionally, the cellular processes and mechanisms underlying resin monomer-induced toxicity, along with possible preventive or therapeutic approaches, are still not well understood. [26,27].

Investigating how resin monomers function presents a fascinating opportunity, as it may lead to key insights for developing better therapeutic strategies for dental restorative biomaterials that protect oral tissues. Evidence suggests an intracellular redox imbalance caused by elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production induced by resin monomers, which subtly influences multiple interconnected signaling pathways related to cell survival and apoptosis [28]. However, the detailed intracellular mechanisms and signaling pathways responsible for this redox imbalance due to resin monomers are not yet fully understood [29,30,31].

Autophagy, also known as macro-autophagy, is a highly conserved and precisely controlled cellular process occurring in all cell types. It involves the breakdown of internal components in response to stress and plays roles in both cell survival and cell death. During autophagy, autophagosomes with double or multiple membranes form by engulfing parts of the cytoplasm and organelles [32]. These autophagosomes then fuse their outer membrane with lysosomes or endosomes, creating single-membrane autolysosomes. The contents within autolysosomes are ultimately broken down by lysosomal enzymes [32]. Key autophagy-related genes (Atg), such as Beclin1 and LC3 (a mammalian equivalent of yeast Atg8), are vital for autophagy initiation. However, autophagy can also occur via pathways that do not involve Beclin1 [32]. Multiple signaling pathways influence autophagy regulation, with the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway being a well-known example [33]. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial cell signaling pathway that regulates the following key cellular processes: metabolism, autophagy, apoptosis, cell growth, and proliferation. It also promotes protein synthesis and cell cycle progression.

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway plays a vital role in regulating autophagy, with mTOR inhibition leading to increased autophagy [33]. mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) is a central regulator of cell growth, metabolism, and autophagy, responding to signals such as nutrients, growth factors, and cellular stress—such as exposure to dental materials. It primarily acts as a negative regulator of autophagy. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) is a serine/threonine kinase crucial for various cellular functions such as cell signaling and autophagy. It represents a key member of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Its link with autophagy is complex and varies with the cellular environment and conditions. GSK3β is activated under stress, like oxidative stress, which can trigger autophagy as a protective mechanism to remove damaged components [34].

Autophagy functions either as a cell survival or cell death mechanism, varying with environmental stress among different cell types, and it can also promote apoptosis [32]. Autophagy protects cells by degrading damaged parts, supporting cell survival. Cytotoxicity measures how much a substance, such as a drug or chemical, damages or destroys cells, indicating its harmful impact on cell health and function. In order to evaluate cytotoxicity in our study, we used the lactate dehydrogenase assay. Cytotoxic stress, caused by toxins or oxidative stress, can trigger autophagy as a defense mechanism to restore cellular health. When this autophagic response is insufficient, it may lead to higher levels of cytotoxicity and cell death. Autophagosomes are essential structures in the cellular process of autophagy, which is a degradation and recycling mechanism for damaged organelles and proteins. Detecting autophagosomes can offer valuable insights into the development of the autophagy process. Therefore, in order to illustrate the intensity level of the autophagy process, in our study, we use the fluorescent detection of autophagosomes [32,35]. Apoptosis is a regulated, programmed process of cell death vital for normal development and tissue homeostasis. It facilitates the removal of damaged or unnecessary cells [36]. Increased cytotoxicity can induce apoptosis by activating specific pathways, and the level of cytotoxicity influences whether a cell undergoes apoptosis or survives, depending on environmental and stress factors [36]. In this study, we used fluorescent detection of annexin V and caspase 3/7 as biomarkers of apoptosis. Annexin V binds to phosphatidylserine, which relocates to the outer membrane early in apoptosis, allowing differentiation between live, apoptotic, and necrotic cells [37]. Caspases 3 and 7 are often referred to as executioner caspases, activated during the later stages of apoptosis. Their presence indicates that cells are undergoing programmed cell death. Autophagy and apoptosis are interconnected processes that determine cell fate [38]. Autophagy protects cells by degrading damaged organelles and proteins that might induce cell death, although excessive autophagy can lead to autophagic cell death, separate from apoptosis [39]. Often, autophagy precedes apoptosis, removing survival factors and promoting apoptotic signals [39].

So far, very few studies have explored whether resin monomers can trigger autophagy or how the Akt/mTOR–autophagy–apoptosis crosstalk might influence resin monomer-induced toxicity in gingival fibroblasts.

In light of the above information, this study utilizes human gingival fibroblasts (HGF), a primary cell type in gingival tissue, to assess the cytotoxicity of three different CRs used in manufacturing temporary prosthetic devices. These resins were produced through distinct manufacturing methods, outlined below: M1 (Nexdent C&B MFH) and M2 (GC TEMP PRINT)—both 3D printed—and M3 (Grandio Voco)—milled. We chose these three composite materials because they all have the same clinical indication, namely, temporary fixed prosthetic restorations, and are from the same class of materials, respectively, composites. The manufacturer does not specify the duration of use or whether they have any limit of use in relation to a temporary fixed restoration with or without gingival contact. From here, we can draw various conclusions according to the results you have. A difference between them is from a compositional point of view, in the sense that the milled one (M3) is prefabricated and has a high degree of ceramic loading with a reduced volumetric amount (implicitly per unit surface area) of polymer compared to the two printed ones, M1 (Nexdent C&B MFH) and M2 (GC TEMP PRINT), which have less ceramic in the polymer matrix and differences between them in ceramic/polymer ratio. Furthermore, we aimed to determine the autophagy-inducing potential of these three types of CR and to explore the possible involvement of the Akt/mTOR–autophagy–apoptosis crosstalk in CR-mediated autophagy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.1.1. Sample Material Composition

In the present study, three types of composite resin-based dental materials were analyzed, obtained with different methods as follows: M1 (Nexdent C&B MFH) and M2 (GC TEMP PRINT)—both 3D printed—and M3 (Grandio Voco)—milled (Table 1 for chemical composition).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of dental material used [4,5,6].

2.1.2. Digital Processing of the Composite Materials Under Study

Digital processing methods of composite materials taken into study were as follows:

- -

- Subtractive Method (CAD-CAM);

- -

- Additive Method (3D Printing).

Subtractive Method (CAD-CAM)

The samples were milled from an industrially prefabricated Voco Grandio disk on the Planmeca PlanMill 60 S machine, manufactured by PLANMECA, Helsinki, Finland. The Planmeca PlanMill 60 S is a powerful five-axis dental milling unit designed for dental laboratories and in-house dental practices. It is used with CAD/CAM software PlanCAM (version 3.1) to digitally mill dental restorations, implant abutments, and other prosthetics from various materials like zirconia, lithium disilicate, PMMA, and wax. The unit is capable of both wet and dry milling and features an automatic tool changer for efficiency.

Additive Method (3D Printing)

The discoidal samples were fabricated using the digital light processing (DLP) technique by use of the Anycubic Mono X 6Ks, developed by Hongkong Anycubic Technology Co., China.

From the materials taken into the study, samples of discoidal shape with diameters of 10 mm and 2 mm thickness were made using the protocol from producers [4,5,6].

2.2. SEM Analysis

The elemental composition was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi TM3030PLUS Tabletop, Tokio, Japan) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS, QUANTAX 70, Bruker) with an XFlash 430H detector. Samples were analyzed at the following different magnifications: ×500, ×2000, ×5000, ×10,000, and ×25,000. These were selected to provide serial details of the sample surfaces.

2.3. Cell Culture

The HFIB-G cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well in a 24-well plate using DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) with 10% FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum) and 1% antibiotic and antimycotic solution, allowed to adhere overnight, and then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in the presence of tree resin-based composite samples: two 3D-printed materials (M1 and M2) and one milled material (M3). The control consists of cells grown in DMEM medium in the absence of dental material. Sterilization of the dental materials was performed for 5 min in alcohol, followed by 30 min of UV exposure on each side [40].

2.4. Cell Viability Assay (MTT Assay)

In this study, the cytotoxicity effect of different types of resin-based composite samples, dental materials, was investigated on the gingival fibroblast cell line HFIB-G, using a solution of 1 mg/mL MTT (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). The MTT test is a colorimetric assay used to assess cell viability, proliferation, and metabolic activity. The assay is based on the reduction of the yellow tetrazole MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) to purple formazan crystals by viable cells. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, a yellow dye, is reduced to formazan crystals only by metabolically active cells. The formazan crystals are purple and were solubilized with isopropanol, and the absorbance was measured at 595 nm with the FLUOstar® Omega multimode microplate reader (BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany). The intensity of the purple color is directly proportional to the number of viable cells [40,41].

2.5. Level of Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH Assay)

The LDH cytotoxicity test is a common assay used to assess cell membrane integrity and cell viability. Damage or death to cells results in the release of LDH into the medium, serving as an indicator of cytotoxicity. The assay involves the conversion of lactate to pyruvate in the presence of the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase and the simultaneous conversion of NAD+ to NADH. Therefore, the LDH enzyme levels of the samples previously incubated for 48 h with HFIB-G cells were measured with an LDH Cytotoxicity Assay (LDH, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR 97402, USA). A total of 50 μL of each sample was added to 50 μL of the LDH reaction mixture. After 30 min of incubation, the multimode microplate reader, FLUOstar® Omega, was used to measure the absorbance at 490 nm and 680 nm. The 680 nm absorbance was subtracted from the 490 nm absorbance value [41].

2.6. Level of Nitric Oxide (Griess Assay)

Nitric oxide (NO) is produced from L-arginine through the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS). Intracellular NO levels are carefully controlled because high amounts can lead to oxidative stress and cell damage. The principle of the NO Assay Kit involves the reaction of nitrite with the Griess reagents, resulting in the formation of a pink product that can be measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. Therefore, a kit for the quantitative determination of nitrite and nitrate in culture medium after a 24 h incubation of samples with HFIB-G cells, the Nitric Oxide Assay Kit from Thermo Fisher, was used to measure the nitric oxide level, according to the manufacturer. The optical density at wavelength 540 nm was measured using a BMG LABTECH’ FLUOstar® Omega multi-mode microplate reader.

2.7. Multiplex Detection (Immunological Assay)

Multiplex detection is a method utilized to identify and examine several substances at once within a single sample. In order to extract the proteins, HFIB-G cells were lysed after the 48 h incubation period in cell signaling lysis buffer from the Akt/mTOR Phosphoprotein 11-plex Magnetic Bead Luminex kit provided by Merck, containing phosphatase inhibitors supplied with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail 1x (G6521, Promega, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Protein concentrations were quantified using the Bradford procedure that employs the dye Brilliant Blue G using the Total Protein Kit, Micro (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. No. TP0100). After that test, protein levels in each sample were normalized. The final concentration used for Luminex kits was 0.44 mg/mL; the samples were diluted in Milliplex assay buffer included in the analysis kit.

Firstly, 50 μL of assay buffer was added to each well on the 96-well plates and mixed on a plate shaker. After 10 min, the assay buffer was discarded, and 25 μL of 1X bead suspension was added to the plates. Then, 25 μL of each sample was added to the appropriate wells. After 18 h of incubation at 4 °C on a plate shaker, the wells were washed twice with 100 μL of assay buffer per well. A total of 25 μL/well of 1X MILLIPLEX® (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) detection antibody was added for 1 h, followed by the same amount of streptavidin–phycoerythrin (SAPE) for 15 min and MILLIPLEX® amplification buffer for another 15 min. Finally, the wells were rinsed with 150 μL of Milliplex assay buffer, and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) data of assay plates were read and analyzed using the Luminex 200 system.

2.8. Annexin V and Nuclei Immunofluorescent Detection (Early Apoptosis)

The cell early apoptosis of HFIB-G was assessed using an Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis detection kit (Calbiochem, EMD Milipore, Merck, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cells after the 24 h incubation were stained with FITC-Annexin V (green fluorescence) and then incubated for 10 min in the dark. In addition, nuclei staining (Hoechst 33258 dye) was used to see the presence of all the cells from each sample. The stained cells were then examined using an IM-3LD4D Optika, Italy microscope and processed using Image J software (version 1.46j).

2.9. Mitochondria and Caspase 3/7 Immunofluorescent Detection (Late Apoptosis)

The mitochondrial activity of HFIB-G cells was assessed using a BioTracker 633 Red Mitochondria Dye fluorescent detection kit (SCT 137, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Dyes from this kit are fluorogenic membrane-permeable stains used to stain mitochondria in live cells. Staining is lost during cell death, when mitochondria become depolarized. After the 24 h incubation, the cells were stained, incubated for 15 min at 37 °C, and then analyzed.

In addition, late apoptosis was tested using the Nuc View 488 Caspase 3/7 assay kit for Live Cells (Biotium cat. NO 30029-T) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This kit provides a convenient tool for profiling apoptotic cell populations based on caspase-3/7 activity using fluorescence microscopy. In apoptotic cells, caspase-3/7 cleaves the substrate, releasing the high-affinity DNA dye, which migrates to the cell nucleus and stains DNA with bright green fluorescence. Briefly, the cells previously incubated for 24 h were stained, incubated for 30 min, and then analyzed.

The stained cells were then examined using an IM-3LD4D Optika, Italy microscope and processed using Image J software.

2.10. Autophagosome Immunofluorescent Detection

The autophagy activity of HFIB-G cells post-incubated for 24 h was tested using Autophagy Assay Kit MAK138 (Sigma Aldrich, Merck) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Autophagy Assay kit provides a simple and direct procedure for measuring autophagy in a variety of cell types using a proprietary fluorescent autophagosome marker (λex = 333/λem = 518 nm). After the incubation, the culture medium was removed, autophagosome detection reagent working solution was added, and then the cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The stained cells were then examined using an IM-3LD4D Optika, Italy microscope and processed using Image J software.

2.11. Statistical Interpretation

Our study results were statistically processed using Student’s t-test (Microsoft Office Excel) and expressed as mean value ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6). A value of p less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The test results of the present study were reported to the values obtained for the control wells and represented graphically. The values used in constructing the graphs represent the arithmetic mean of the results obtained corresponding to each type of test in particular.

3. Results

3.1. SEM Analysis

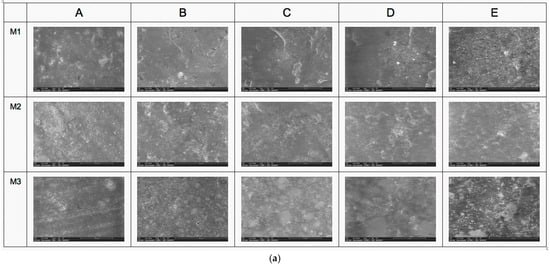

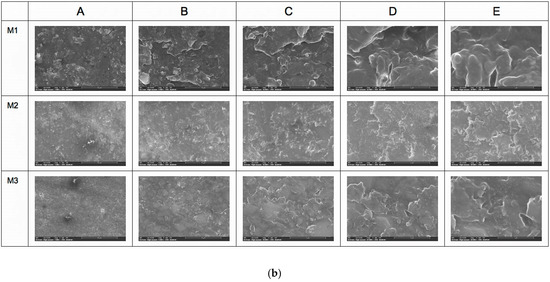

SEM analyses reveal the surface structure and morphology of the materials taken into the study in different magnifications (500×, 1.000×, 5000×, 10,000×, and 25,000×). It can be noticed that the heterogeneous structure of composite materials is in all samples at different levels of magnification. The fillers of ceramic materials embedded into the polymeric structure are more compact in samples M3, with hybrid nanoparticle sizes up to 0.5 microns in diameter (M3B–E in Figure 1). The M1 samples also present at the surface the filling particles, but with a lower level of hybridization, having particles predominantly with a small nano-sized diameter. From all analyzed samples, the SEM investigation showed that M2 material has the lowest quantity of filler present at the investigated surface and, consequently, the maximum polymer matrix. On EDT-SEM images, it can be noticed that the surface aspect of polymeric matrices of all investigated samples, where M3 is the most compact and continuous surface and M2 is the least continuous and presents many irregularities (Figure 1a,b).

Figure 1.

(a) SEM analysis with LVD detector (A—500×, B—1000×, C—5000×, D—10,000×, and E—25,000×). (b) SEM analysis with EDT detector (A—500×, B—1000×, C—5000×, D—10,000×, and E—25,000×).

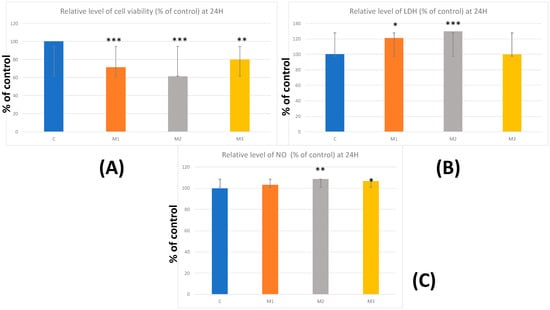

3.2. Viability and Cytotoxicity Test Results

The biocompatibility study was based on biological tests conducted according to ISO standards 10993–5:1999 (Biological evaluation of medical devices; Part 5: tests for in vitro cytotoxicity). The results of the MTT test showed significant declines in cell viability after 24 h of incubation in 3D-printed samples: M2 with 38.7% (p < 0.001) and M1 with 28.48% (p < 0.001), which the ISO standard 10993-5:1999 considers as not biocompatible. M3 material experienced decreases of approximately 20% in cell viability (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Viability and cytotoxicity results—(A) relative level of cell viability % of control at 24 h; (B) relative level of LDH % of control at 24 h; (C) relative level of NO % of control at 24 h. Results are means ± SD (n = 6) * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Regarding the results of the LDH assay, this parameter showed significantly increased levels in M1 by 21.22% and in M2 by 29.74% (p < 0.05; p < 0.001), compared to control cells. In M3, no significant difference was observed compared to the control. The increased LDH levels indicate cell membrane damage, suggesting a higher cytotoxic effect of M1 and M2 samples (Figure 2B).

The results of the Griess test showed statistically significant increases only in the case of M2 (8.69%) (p < 0.01) and M3 (6.71%) (p < 0.05). These data may indicate a slight proinflammatory effect of these two types of resin composites following 24 h incubation (Figure 2C).

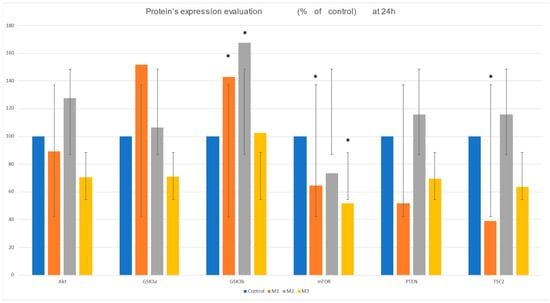

3.3. Protein’s Expression Evaluation—Multiplex Assay

3.3.1. Akt Protein Expression

After analyzing the results, a decrease in Akt protein expression was observed in samples M1—10.77% and M3—29.7%. However, in M2 material, an increase of 27.67% was recorded compared to the control (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Protein expression evaluation: Akt, GSK2a, GSK2b, mTOR, pTEN, and TSC2 after 24 h incubation of the four materials with HFIB-G: C-control, M1, and M2—3D-printed resin composites and M3—milled resin composite. Results are presented as means ± SD (n = 6); * p < 0.05.

3.3.2. GSK3a Protein Expression

Regarding GSK3a, after 24 h, protein expression increases by 51.61% in the 3D-printed material M1 compared to the control. M2 shows a modest increase of 6.23%, whereas M3 exhibits a decrease of 29% (Figure 3).

3.3.3. GSK3b Protein Expression

Conversely, GSK3b levels significantly increased in 3D-printed materials, with M1 rising by 42.92% and M2 by 67.6%. M3 showed no significant change compared to the control, only a minor increase of 2.47% (Figure 3).

3.3.4. mTOR Protein Expression

Regarding the mTOR levels, a sharp decrease is observed in the case of all tested dental materials: for M3 by 48%, for M1 by 35%, and for M2 by 26%, compared to the control, as can be seen from the graph in Figure 3.

3.3.5. pTEN Protein Expression

pTEN has a very interesting evolution because it recorded decreases in expression for the samples M1 (48.3%) and M3 (30.5%), while in the case of M2, data revealed an increase of 15.7% (Figure 3).

3.3.6. TSC2 Protein Expression

TSC2 shows a significant decrease of 61% for one of the 3D-printed materials, while for M3, our data revealed only slight decreases of 15.84%. Interestingly, the incubation with the M2 samples induced a 37.3% increase in TSC2 levels (Figure 3).

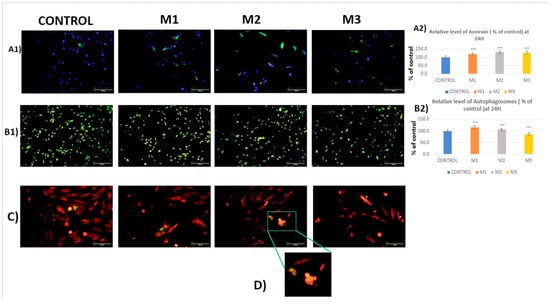

3.4. Fluorescent Staining Results

Regarding annexin V, an early apoptosis marker, our results revealed a significant increase in fluorescence intensity for all three tested CRs (for M1 by 18.5%, M2 by 31.8%, and M3 by 28.3%; p < 0.001) compared to the control (Figure 4A1,A2). These results suggested an apoptosis initiation process after 24 h of incubation.

Figure 4.

(A1,A2): Fluorescence detection and quantification of Annexin V expression and nuclei (blue—nuclei and green—annexin V). (B1,B2): Fluorescence detection and quantification of CR-induced autophagosome formation (green—autophagosomes). (C): Fluorescence detection of mitochondria (red) and CR-induced caspase 3/7 expression (green), 20× objective and 100 μm scales. (D): cluster of apoptotic cells. Results are means ± SD (n = 6) * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Regarding the formation of autophagosomes, it can be observed from both the images and the statistical analysis that fluorescence is reduced by 13% in samples M3 compared to the control, suggesting a downregulation of the autophagic flux. However, our results show a slight increase in autophagosome formation for sample M1 by 16.1% and by 5.6% for M2 compared to the control (Figure 4A1,A2 and Table 2), suggesting an upregulation of autophagy.

Table 2.

Variation in parameters tested % of control (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

While restorative materials generally do not cause direct pathological effects, some groups have shown higher levels of oxidative stress and inflammatory markers, whereas others may exhibit distinct patterns [42]. Autophagy is an essential intracellular process that recycles damaged proteins and organelles and destroys intracellular pathogens. It involves enclosing cytosolic components in a double-membrane vesicle called an autophagosome, which then fuses with a lysosome for degradation [42]. Dysfunction in autophagy can lead to hyperinflammation. Removing activators such as cytokines via autophagy can reduce inflammation [42]. Since inflammation may indicate a lack of biocompatibility in dental materials and autophagy plays a key role in controlling inflammatory responses, it is important to focus on autophagy in biocompatibility studies. Additionally, 3D-printed composite resin-based temporary scaffolds are increasingly considered promising alternatives to traditional methods because of their enhanced physicochemical and clinical qualities [43]. Hence, it is crucial to investigate the toxic effects of composite resins and their molecular impact on oral cells [40]. Presently, the activation of autophagy via various chemicals is being recognized as a pathway involved in toxicity [43]. The connection between composite resin toxicity and autophagy-related cell death remains uncertain. In this study, we examine how three different CRs—two 3D-printed and one milled—affect the interaction between AKT/mTOR, autophagy, and apoptosis. Based on metabolic activity and cytotoxicity test results, we further analyzed cellular signaling, with a focus on autophagy, a key factor in cell survival or death, and its upstream regulator, the Akt/mTOR pathway. Recent studies suggest that autophagy and apoptosis are interconnected in oral cells exposed to resin-based dental materials [44,45]. Additionally, autophagic cell death has been noted following exposure to dental resin-based materials [44]. Apoptosis and autophagy, although distinct processes, often overlap to control cell fate [44,45] and exhibit significant cross-talk [44,45]. Nonetheless, the precise effects of dental restorative composite resins on these pathways and their molecular mechanisms remain not fully understood. Gaining deeper insights could lead to the development of safer, more user-friendly restorative materials and better temporary restoration strategies [43].

Considering the background of the above, regarding the M1 material (3D-printed CR with an approximate total percentage of methacrylate-based monomer content of 85%), our results revealed significant decreases in metabolic activity (p < 0.05) and in the expression of mTOR and TSC2 (p < 0.05, p < 0.05, respectively). Moreover, the data showed significant increases in the LDH (cytotoxicity marker) level (p < 0.05), GSK3b expression (p < 0.05), annexin V expression level (p < 0.05), and the autophagosome formation level (p < 0.05) (Table 2). GSK3a protein expression and pTEN protein expression revealed no significant differences between the analyzed groups.

Several studies reported methacrylate-induced oxidative stress in cells exposed to polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)-based dental materials [44]. It has been outlined that GSK3β may inhibit the Akt/mTOR pathway—a major suppressor of autophagy—thus indirectly enhancing autophagy during stress or nutrient deficiency [34]. The interaction between GSK3β, mTOR, and TSC2 is crucial for regulating autophagy: reduced GSK3β activity or proper activation of TSC2 decreases mTOR activity, which in turn promotes autophagy [34,46]. In the present study, the accumulation of autophagosomes seemed to be mediated through the classical mTOR pathway, which was in accordance with the previously reported results [34,46,47]. Thus, our results may conclusively suggest that the accumulation of autophagosomes (illustrated in Figure 4B1,B2) was possibly triggered via Akt/mTOR signaling, with a focus on the GSK3b-mTOR interplay, outlining a key role of autophagy in the M1 composite resin-induced toxicity, illustrated by the MTT and LDH test results (Figure 2A,B). Moreover, besides its role in promoting cell survival, autophagy has also been implicated in cell death processes like apoptosis by removing cellular components and survival factors, leading to cellular toxicity [43,48,49,50,51]. In the present study, the results of annexin V fluorescent labeling of M1-exposed cells revealed a significant rise in annexin V-positive cells compared to control (Figure 4A1,A2). Additionally, the evolving apoptotic pathway was confirmed by the fluorescent labeling of caspase 3/7, an apoptotic executioner, showing a significantly increased expression in the M1-exposed cells versus the control. These data are aligned with the MTT tests, which illustrated a reduced metabolic activity and viability of the M1-incubated HGF.

According to the presented SEM results (Figure 1a,b), M2’s lower filler content might lead to a more polymer-rich surface, which can influence the material’s interaction with biological tissues. A higher polymer matrix may enhance flexibility and reduce brittleness, potentially improving biocompatibility. M2’s surface irregularities could hinder cell adhesion or lead to inflammation. A rough surface may trap proteins and cells, potentially leading to adverse reactions. Furthermore, regarding the M2 material, our results revealed significant decreases in metabolic activity (p < 0.05). Moreover, similar to M1, the data showed significant increases in the LDH (cytotoxicity marker) level (p < 0.05), GSK3b expression (p < 0.05), annexin V expression level (p < 0.05), and the autophagosome formation level (p < 0.05) (Table 2). However, GSK3a protein expression and pTEN protein expression revealed no significant differences between the analyzed groups. In addition to M1, M2 CR exposure resulted in a significant increase in NO level (p < 0.05) (Figure 2C; Table 2). NO functions as a second messenger in various signaling pathways, affecting cellular responses to different stimuli. It can modulate the activity of various proteins and enzymes [52]. M2 is a 3D-printed CR with an approximate total percentage of methacrylate-based monomer content of 70–90%, according to the supplier’s information. In the case of M2-incubated HGF, our results, illustrating no significant differences versus control, suggest that the observed accumulation of autophagosomes was orchestrated independently of mTOR signaling. Interestingly, autophagy can also be initiated independently of mTOR. In some stressful circumstances, the autophagic flux may be impaired, causing an accumulation of autophagosomes rather than increasing the autophagic machinery efficiency [34,43,46,53,54,55]. The interaction among mTOR, TSC2, and GSK3β is essential in autophagy, coordinating signals that control cell stress response. This cooperation allows cells to carry out autophagic processes efficiently. Such interactions are vital for cellular stability, particularly under stress, by supporting component recycling and adapting to environmental changes. If any of these components are disrupted, autophagy can be impaired, triggering the metabolic rate and cell viability downregulation [34,46,47]. Blockage of autophagic flux can lead to autophagy-induced cell death, as previously reported, caused by a lack of energy supply and reduced recycling of damaged proteins [34,46,47]. Moreover, increased NO levels, also illustrated by our data (Figure 2C), can influence mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, potentially affecting cell survival and apoptosis [52]. It has been outlined that autophagy contributes to cell death through apoptosis by removing cellular constituents and survival factors, resulting in cellular toxicity [43,56,57]. Our results, showing GSK3b and annexin V expression significantly increasing (Figure 3 and Figure 4A1,A2) along with autophagosome accumulation (Figure 4B1,B2), are in alignment with the findings above. Moreover, our results might suggest the accumulation of autophagosome-mediated apoptosis (Figure 4A1,A2,C,D), probably via the induction of oxidative stress caused by HGF exposure to the methacrylate-based CR. Similar results were reported by Sandeep Mittal in a study conducted on human epithelial lung cells [43]. Sandeep Mittal et al.’s study showed that impaired lysosomal function and cytoskeletal disruption blocked autophagic flux. This blockade, caused mainly by autophagosome accumulation rather than increased efficient autophagy, further triggered apoptosis [43].

Samples M3, which exhibit a more compact and continuous surface, according to SEM results (Figure 1a,b), may provide a better environment for cell attachment and growth, enhancing biocompatibility, as illustrated by the metabolic activity/viability and cytotoxicity tests. M3’s continuous surface may facilitate smoother interactions with cells and proteins, potentially reducing inflammatory responses. Furthermore, regarding the M3 material, a milled nano-ceramic hybrid composite with an approximate methacrylate percentage of 13%, our results revealed significant decreases in metabolic activity (p < 0.05) versus control. However, unlike M1 and M2, the data showed no significant differences in the LDH (cytotoxicity marker) level and GSK3b expression. Furthermore, our results revealed significant decreases in mTOR expression (p < 0.05) (Figure 3) and autophagosome accumulation level (p < 0.05) (Figure 4B1,B2) compared to control. Unlike M1, M3 CR exposure resulted in a significant increase in NO level (p < 0.05) (Figure 2C; Table 2). Nitric oxide (NO) acts as a physiopathological messenger, producing various reactive nitrogen species (RNS) depending on hypoxic, acidic, and redox conditions. Recent advances show that RNS and reactive oxygen species (ROS) induce important post-translational modifications, including nitrosation, nitration, and oxidation, affecting key components involved in cell proliferation, viability, and death [52]. Interestingly, in the case of M3-incubated HGF, our results showed a significant decrease in mTOR expression along with a downregulation of autophagosome accumulation. mTOR is one of the key controllers of autophagy; its activation triggers the downregulation of autophagy. However, our data may suggest an mTOR-independent autophagic flux dysregulation, probably triggered by an oxidative stress-dependent lysosome and cytoskeleton disruption. This dysregulation may orchestrate the cell metabolic activity decrease (illustrated by the MTT test results, Figure 2A) through energetic impairment [43].

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the relatively small size of the dataset (n = 6) may limit the generalizability and statistical robustness of the findings. Second, the analysis was restricted to a limited number of dental materials, which may not fully capture the variability in mechanical and functional properties observed across a broader range of material types. Finally, the use of a single type of 3D printer constrains the applicability of the results, as differences in printing technologies, hardware configurations, and process parameters could influence the outcome. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating larger datasets, a wider variety of materials, and multiple 3D-printing systems to enhance the validity and reproducibility of the results.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we reported the interaction of three types of CR, two 3D-printed and one milled, with HGF, accompanied by the interplay between the Akt/mTOR pathway, autophagy, and apoptosis. As illustrated by our results, the surface structure and morphology of the materials influenced their biocompatibility. A more compact, evenly distributed filler structure (like in M3) may promote better cell adhesion and reduce inflammatory responses. In contrast, irregularities and lower filler content (as seen in M2) might lead to less favorable interactions with biological tissues. Furthermore, our data revealed that all three tested CR-induced autophagy dysregulations. In the cases of M1 and M2, these disturbances triggered an apoptotic cell death.

Conclusively, the results of the present study suggest that the M1 CR revealed the most modest biocompatibility, as illustrated by metabolic activity, cytotoxicity, proinflammatory tests, and the exploration of the Akt/mTOR-autophagy-apoptosis crosslink, taken all together.

Understanding the interplay between autophagy and apoptosis, key regulators of cell survival, might be strategically helpful in developing effective strategies to manage inflammatory responses during temporary restorative treatments. Moreover, the relationship between apoptosis and autophagy is highly complex, indicating they may occur in sequence, coexist, or be mutually exclusive. Understanding this complex relationship process can aid in designing new 3D-printing protocols and monomer compositions to prevent autophagy imbalance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R., R.R., and A.R.; methodology, F.R., M.M., and A.R.; software, A.P., R.R., and S.-A.B.; validation, A.R., F.R., L.T.C., and M.I. (Marina Imre); formal analysis, A.P., F.R., and C.M.; investigation, F.R., M.I. (Melis Izet), and L.T.C.; resources, M.I. (Melis Izet), A.P., and S.-A.B.; data curation, F.R. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R., R.R., L.T.C., and A.R.; writing—review and editing, F.R., A.P., and C.M.; visualization, A.R., M.I. (Melis Izet), and L.T.C.; supervision, A.R., M.I. (Marina Imre), and M.M.; project administration, A.R., M.I. (Marina Imre), and C.M.; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali, Z.; Baker, S.R.; Shahrbaf, S.; Martin, N.; Vettore, M.V. Oral health-related quality of life after prosthodontic treatment for patients with partial edentulism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 59–68.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.J.; Saponaro, P.C. Management of Edentulous Patients. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, M.; Paz, A.G.; Miguel, I.; Coachman, C. Fully digital workflow, integrating dental scan, smile design and CAD-CAM: Case report. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Available online: https://nextdent.com/products/cb-mfh-micro-filled-hybrid/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.gc.dental/america/products/digital/3d-printing/gc-temp-print (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.dt-shop.com/index.php?id=22&L=1&artnr=01436&aw=116&pg=12&geoipredirect=1 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Cernega, A.; Meleșcanu Imre, M.; Ripszky Totan, A.; Arsene, A.L.; Dimitriu, B.; Radoi, D.; Ilie, M.I.; Pițuru, S.M. Collateral Victims of Defensive Medical Practice. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cândea Ciurea, A.; Şurlin, P.; Stratul, Ş.I.; Soancă, A.; Roman, A.; Moldovan, M.; Tudoran, B.L.; Pall, E. Evaluation of the biocompatibility of resin composite-based dental materials with gingival mesenchymal stromal cells. Microsc. Res. Technol. 2019, 82, 1768–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernega, A.; Mincă, D.G.; Furtunescu, F.L.; Radu, C.P.; Pârvu, S.; Pițuru, S.M. The Predictability of the Dental Practitioner in a Volatile Healthcare System: A 25-Year Study of Dental Care Policies in Romania (1999–2023). Healthcare 2025, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galvão, M.R.; Caldas, S.G.; Bagnato, V.S.; de Souza Rastelli, A.N.; de Andrade, M.F. Evaluation of degree of conversion and hardness of dental composites photo-activated with different light guide tips. Eur. J. Dent. 2013, 7, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abed, Y.A.; Sabry, H.A.; Alrobeigy, N.A. Degree of Conversion and Surface Hardness of Bulk-Fill Composite versus Incremental-Fill Composite. Tanta Dent. J. 2015, 12, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A.; Nijakowski, K.; Potempa, N.; Sieradzki, P.; Król, M.; Czyż, O.; Radziszewska, A.; Surdacka, A. Press-On Force Effect on the Efficiency of Composite Restorations Final Polishing—Preliminary In Vitro Study. Coatings 2021, 11, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A.; Nijakowski, K.; Nowakowska, M.; Wo’s, P.; Misiaszek, M.; Surdacka, A. Influence of Selected Restorative Materials on the Environmental PH: In Vitro Comparative Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, K.; Gupta, S.; Nikhil, V.; Jaiswal, S.; Jain, A.; Aggarwal, N. Effect of Different Finishing and Polishing Systems on the Surface Roughness of Resin Composite and Enamel: An In Vitro Profilometric and Scanning Electron Microscopy Study. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2019, 9, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, A.U.; Lee, H.K.; Sabapathy, R. Release of methacrylic acid from dental composites. Dent. Mater. 2000, 16, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, T.R.; Hakami-Tafreshi, R.; Tomasino-Perez, A.; Tayebi, L.; Lobner, D. Effects of dental composite resin monomers on dental pulp cells. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshinaga, K.; Yoshihara, K.; Yoshida, Y. Development of New Diacrylate Monomers as Substitutes for Bis-GMA and UDMA. Dent. Mater. Off. Publ. Acad. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, e391–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilescu, E.; Docan, A.; Vasilescu, V.G.; Popa, C.L.; Ionel, D.C.; Muntenita, C. Experimental study on the improvement of the use of diacrylic composite resins in restorative dentistry by compensatory techiniques. Mater. Plast. 2019, 56, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huyang, G.; Palagummi, S.V.; Liu, X.; Skrtic, D.; Beauchamp, C.; Bowen, R.; Sun, J. High Performance Dental Resin Composites with Hydrolytically Stable Monomers. Dent. Mater. Off. Publ. Acad. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soanca, A.; Lupse, M.; Moldovan, M.; Pall, E.; Cenariu, M.; Roman, A.; Tudoran, O.; Surlin, P.; Soritau, O. Applications of Inflammation-Derived Gingival Stem Cells for Testing the Biocompatibility of Dental Restorative Biomaterials. Ann. Anat. Anat. Anz. Off. Organ Anat. Ges. 2018, 218, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, D.; Wolfgarten, M.; Enkling, N.; Helfgen, E.-H.; Frentzen, M.; Probstmeier, R.; Winter, J.; Stark, H. In-Vitro Cytocompatibility of Dental Resin Monomers on Osteoblast-like Cells. J. Dent. 2017, 65, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocan, L.T.; Biru, E.I.; Vasilescu, V.G.; Ghitman, J.; Stefan, A.R.; Iovu, H.; Ilici, R. Influence of Air-Barrier and Curing Light Distance on Conversion and Micro-Hardness of Dental Polymeric Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Imre, M.; Șaramet, V.; Ciocan, L.T.; Vasilescu, V.G.; Biru, E.I.; Ghitman, J.; Pantea, M.; Ripszky, A.; Celebidache, A.L.; Iovu, H. Influence of the Processing Method on the Nano-Mechanical Properties and Porosity of Dental Acrylic Resins Fabricated by Heat-Curing, 3D Printing and Milling Techniques. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ciocan, L.T.; Ghitman, J.; Vasilescu, V.G.; Iovu, H. Mechanical Properties of Polymer-Based Blanks for Machined Dental Restorations. Materials 2021, 14, 7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vasilescu, V.G.; Stan, M.S.; Patrascu, I.; Dinischiotu, A.; Vasilescu, E. In vitro testing of materials biocompatibility with controled chemical composition. Rev. Romana Mater.-Rom. J. Mater. 2015, 45, 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, L.; Liu, S.; Yu, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Peng, B. Autophagy in resin monomer-initiated toxicity of dental mesenchymal cells: A novel therapeutic target of N-acetyl cysteine. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 6820–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saramet, V.; Stan, M.S.; Ripszky Totan, A.; Țâncu, A.M.C.; Voicu-Balasea, B.; Enasescu, D.S.; Rus-Hrincu, F.; Imre, M. Analysis of Gingival Fibroblasts Behaviour in the Presence of 3D-Printed versus Milled Methacrylate-Based Dental Resins—Do We Have a Winner? J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, F.; Neculau, C.; Imre, M.; Duica, F.; Popa, A.; Moisa, R.M.; Voicu-Balasea, B.; Radulescu, R.; Ripszky, A.; Ene, R.; et al. Polymeric Materials Used in 3DP in Dentistry—Biocompatibility Testing Challenges. Polymers 2024, 16, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chang, M.C.; Wang, H.H.; Huang, G.F.; Lee, Y.L.; Wang, Y.L.; Chan, C.P.; Yeung, S.Y.; Tseng, S.K.; Jeng, J.H. Urethane dimethacrylate induces cytotoxicity and regulates cyclooxygenase-2, hemeoxygenase and carboxylesterase expression in human dental pulp cells. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.-C.; Chen, L.-I.; Chan, C.-P.; Lee, J.-J.; Wang, T.-M.; Yang, T.-T.; Lin, P.-S.; Lin, H.-J.; Chang, H.-H.; Jeng, J.-H. The role of reactive oxygen species and hemeoxygenase-1 expression in the cytotoxicity, cell cycle alteration and apoptosis of dental pulp cells induced by BisGMA. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8164–8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweikl, H.; Petzel, C.; Bolay, C.; Hiller, K.A.; Buchalla, W.; Krifka, S. 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate-induced apoptosis through the ATM- and p53-dependent intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2890–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yao, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sarkar, S.; Ravikumar, B.; Floto, R.A.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Rapamycin and mTOR-independent autophagy inducers ameliorate toxicity of polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin and related proteinopathies. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Button, R.W.; Vincent, J.H.; Strang, C.J.; Luo, S. Dual PI-3 kinase/mTOR inhibition impairs autophagy flux and induces cell death independent of apoptosis and necroptosis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 5157–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhen, Y.; Stenmark, H. Autophagosome Biogenesis. Cells 2023, 12, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, X.; Lai, Y.; Hua, Z.C. Apoptosis and apoptotic body: Disease message and therapeutic target potentials. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20180992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crowley, L.C.; Marfell, B.J.; Scott, A.P.; Waterhouse, N.J. Quantitation of Apoptosis and Necrosis by Annexin V Binding, Propidium Iodide Uptake, and Flow Cytometry. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, A.K.; Hall, A.; Lundsgart, H.; Moghimi, S.M. Combined Fluorimetric Caspase-3/7 Assay and Bradford Protein Determination for Assessment of Polycation-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Methods Mol Biol. 2019, 1943, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorice, M. Crosstalk of Autophagy and Apoptosis. Cells 2022, 11, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dumitru, C.D.; Ilie, C.-I.; Neacsu, I.A.; Motelica, L.; Oprea, O.C.; Ripszky, A.; Pițuru, S.M.; Voicu Bălașea, B.; Marinescu, F.; Andronescu, E. Antimicrobial Composite Films Based on Alginate–Chitosan with Honey, Propolis, Royal Jelly and Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitru, C.D.; Neacșu, I.A.; Oprea, O.C.; Motelica, L.; Voicu Balasea, B.; Ilie, C.-I.; Marinescu, F.; Ripszky, A.; Pituru, S.-M.; Andronescu, E. Biomaterials Based on Bee Products and Their Effectiveness in Soft Tissue Regeneration. Materials 2025, 18, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjevac, T.; Taso, E.; Stefanovic, V.; Petkovic-Curcin, A.; Supic, G.; Markovic, D.; Djukic, M.; Djuran, B.; Vojvodic, D.; Sculean, A.; et al. Estimating the Effects of Dental Caries and Its Restorative Treatment on Periodontal Inflammatory and Oxidative Status: A Short Controlled Longitudinal Study. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 716359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mittal, S.; Sharma, P.K.; Tiwari, R.; Rayavarapu, R.G.; Shankar, J.; Chauhan, L.K.S.; Pandey, A.K. Impaired lysosomal activity mediated autophagic flux disruption by graphite carbon nanofibers induce apoptosis in human lung epithelial cells through oxidative stress and energetic impairment. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2017, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krifka, S.; Spagnuolo, G.; Schmalz, G.; Schweikl, H. A review of adaptive mechanisms in cell responses towards oxidative stress caused by dental resin monomers. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 4555–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.-C.; Chen, J.-H.; Lee, H.-N.; Chen, S.-Y.; Zhong, B.-H.; Dhingra, K.; Pan, Y.-H.; Chang, H.-H.; Chen, Y.-J.; Jeng, J.-H. Inducing cathepsin L expression/production, lysosomal activation, and autophagy of human dental pulp cells by dentin bonding agents, camphorquinone and BisGMA and the related mechanisms. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 145, 213253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, C.; Mamais, A.; Roosen, D.A.; Dihanich, S.; Soutar, M.P.M.; Plun-Favreau, H.; Bandopadhyay, R.; Hardy, J.; Tooze, S.A.; Cookson, M.R.; et al. mTOR independent regulation of macroautophagy by Leucine Rich Repeat Kinase 2 via Beclin-1. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fang, S.; Wan, X.; Zou, X.; Sun, S.; Hao, X.; Liang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Sun, B.; Li, H.; et al. Arsenic trioxide induces macrophage autophagy and atheroprotection by regulating ROS-dependent TFEB nuclear translocation and AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, Y.; Su, Q.; Yue, C.; Zou, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, H.; Song, R.; Liu, Z. The Effect of Oxidative Stress-Induced Autophagy by Cadmium Exposure in Kidney, Liver, and Bone Damage, and Neurotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yin, Q.; Yang, H.; Fang, L.; Wu, Q.; Gao, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, L. Fibroblast growth factor 23 regulates hypoxia-induced osteoblast apoptosis through the autophagy-signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 28, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nikoletopoulou, V.; Markaki, M.; Palikaras, K.; Tavernarakis, N. Crosstalk between apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 3448–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Su, Y.; Gao, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X. Transition of autophagy and apoptosis in fibroblasts depends on dominant expression of HIF-1α or p53. J. Zhejiang Univ. B 2022, 23, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- González, R.; Molina-Ruiz, F.J.; Bárcena, J.A.; Padilla, C.A.; Muntané, J. Regulation of Cell Survival, Apoptosis, and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition by Nitric Oxide-Dependent Post-Translational Modifications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1312–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, A.; Noda, T.; Yoshimori, T.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Chemical modulators of autophagy as biological probes and potential therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hau, A.M.; Greenwood, J.A.; Löhr, C.V.; Serrill, J.D.; Proteau, P.J.; Ganley, I.G.; McPhail, K.L.; Ishmael, J.E. Coibamide A induces mTOR-independent autophagy and cell death in human glioblastoma cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cinà, D.P.; Onay, T.; Paltoo, A.; Li, C.; Maezawa, Y.; De Arteaga, J.; Jurisicova, A.; Quaggin, S.E. Inhibition of MTOR disrupts autophagic flux in podocytes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shen, S.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G. End Autophagic Cell Death? Autophagy 2012, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G.; Levine, B. Autophagic cell death: The story of a misnomer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.