Featured Application

This paper provides theoretical data for a deeper explanation of the structure–cytotoxic activity relationship for cathinones. These results could be potentially useful in pharmacology, medicine, and forensics for better understanding the cytotoxic activity of different known cathinones, as well as in the development of new cathinone-based medicines.

Abstract

Cathinone and its synthetic derivatives are among the most popular classes of narcotics worldwide. Experimental studies have demonstrated variable cytotoxic activity among these substances. Until now, the research on cathinones has been limited to their psychotropic activity. Therefore, the structure–activity correlation in this group remains poorly understood. The current study aimed to expand the understanding of the influence of cathinone structural modifications on cytotoxic activity. A group of cathinones whose cytotoxic activity has been experimentally analyzed by a single research group was studied in silico using density functional theory (DFT). A systematic characterization of the substituent effect and the aromaticity changes depending on the polarity of the medium is presented in this paper. A correlation between growing electron-withdrawing properties of the N-end and its carbonyl fragment as well as aromaticity decrease with growing cytotoxic activity were observed.

1. Introduction

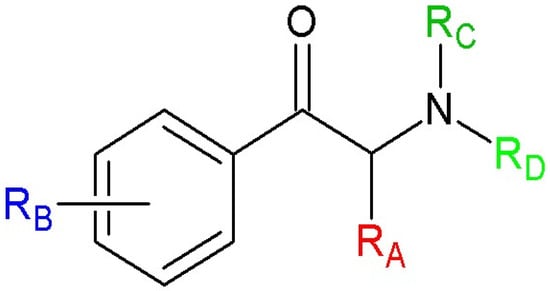

Cathinone has been known for centuries as an abuse drug. This compound naturally occurs as a metabolite of the Catha edulis (Khat) plant growing in some countries in the Horn of Africa and Western Asia (such as Ethiopia, the Republic of Somaliland, Kuwait, and Qatar) [1]. The relatively low cost and ease of synthesis and isolation from plant material makes cathinone and its synthetic derivatives one of the biggest and most popular narcotics groups in the world. New representatives of this group are constantly appearing in the world register of narcotic substances [2,3,4,5,6]. Therefore, it is difficult to assess both the psychotropic and toxic potential of these substances. A growing number of forensic reports and scientific articles are reporting new diseases and fatal outcomes caused by cathinone and its derivatives [2,3,4]. Neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and cardiotoxicity are the most common, but the spectrum of negative effects of cathinones is wide [2,3,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Although the first data on cathinone and its synthetic derivatives appeared in scientific literature in the first half of the 20th century [17], the mechanisms underlying neurostimulation, addiction, metabolism, and cytotoxicity of this class of compounds remain incompletely understood [5,11,18]. For this reason, it is critically important to expand the global database of chemical and biochemical properties of these substances. Determining correlations between properties and structural modifications of cathinones deserves special attention [16,17,18]. Cathinones are β-keto residues of amphetamines (see general formula in Figure 1) [2].

Figure 1.

General formula of cathinone and its synthetic derivatives (RA, RB, RC, and RD are possible substituent positions).

Therefore, these two groups are expected to have similar chemical and biological properties. However, some literature data demonstrate that their neurostimulant and toxicological potential is significantly altered by structural modifications [5,13,18]. For example, in study [19], the authors demonstrate that modification of an alkyl chain in the RA position (according to the Figure 1) has a significant influence on toxicity, as well as dopamine (DA) uptake inhibition and a dependent stimulation effect. It was observed that the cytotoxicity, measured on the PC12 cell line, increased with elongation of the chain. However, DA uptake inhibition and psychostimulant effects grow only until the elongation from the methyl to propyl chain. Further RA extension led to a weakening of the neuroeffects both in vitro and in vivo. An in vitro study on SH-SY5Y, Hep G2, RPMI 2650, and H9C2(2-1) cell lines [16] should be also mentioned as another example of the structure–cytotoxicity relationship. Nine cathinone derivatives with RA elongation from the propyl to hexyl chain as well as simultaneous addition of fluorine or a methoxy group in the RB and pyrrolidine ring in the RC and RD positions were analyzed. It was observed that cytotoxic properties of cathinones intensify with substitution in all positions. Additional confirmation of structure-dependent cytotoxicity in undifferentiated and differentiated SH-SY5Y cell lines is found in [20]. It was shown that halogenation of methcathinone at the RB position leads to an increase in its neurotoxicity. These effects intensify with increasing atomic mass of the substituent. The increase in neurotoxic properties measured on the SH-SY5Y cell line was also observed for synthetic cathinones with substituent increases in the RB, RC, and RD positions [21]. Structural modifications also lead to modifications in the distribution of cathinones in organisms. Depending on the structure of a given drug, their ability to pass through various biological barriers (for example, cell membrane, organ–blood, and blood–lymph) changes [4,13,16,20,21,22]. Several studies also demonstrate that substitution of cathinone in different positions enhances its membrane-damaging potential through different mechanisms. This process is strongly related to the structure and number of substituents [16,20,21]. Differing abilities of membrane penetration lead to the accumulation and toxic effects of different cathinones in different parts of the “consumer” body, as well as differences in their metabolism and elimination efficiency [2,8,11,18,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

As can be seen, the structure–activity relationship (SAR) for cathinones is highly relevant to forensic medicine and criminalistics. Furthermore, scientific literature indicates that cathinone and some of its derivatives may have potential applications in pharmacy and medicine. For example, bupropion is a registered antidepressant and smoking cessation agent [29,30]. Some studies suggest the potential of some cathinone derivatives for the treatment of chronic fatigue and obesity [31,32]. The cytotoxic activity measured for selected cancer cell lines and the selectivity of the cytostatic effect of some cathinones are also worth mentioning [21,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. An important trend regarding an increase in cytostatic activity of mephedrone with the growth of neoplasm carcinogenesis is also described [41,42,43,44]. A decrease in the psychostimulant properties of cathinones with an increase in their cytotoxicity has also been observed [2,16,19,20]. These data could be important in the development of new anticancer drugs based on the cathinone structure. However, experimental studies on this group of substances are limited by their psychoactivity. Therefore, molecular modeling may serve as a useful tool for determining preliminary SAR data for further experimental confirmation.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the cathinone structure could be modified at four positions, A–D, by substituents with different electronic structures. Therefore, correlating the substituent effect (SE) with cytotoxic activity could help to understand which substituents, and at which positions, play a crucial role in shaping the type and strength of interactions of cathinones with biomolecular targets. SE could also clarify the susceptibility of cathinones to chemical modification leading to the activation or deactivation of their cytotoxic properties. The literature provides data on the effectiveness of SE approaches in determining both the interactions of potential drug molecules with different biomolecular structures [45,46,47,48] and their ability to undergo chemical and biochemical transformations [49,50,51,52]. However, currently there are no systematic analyses in the literature on the correlation of SEs with the chemical and biochemical properties of cathinones. Figure 1 also shows that cathinones possess a benzene ring in their structure. Therefore, their substitution with substituents of different electron-donating or withdrawing properties can affect the aromaticity of the ring, which may also play a role in determining interactions with biomolecules and the ability to undergo biotransformation. The effect of aromaticity changes on the interactions of biologically active substances with biomolecular structures and the ability of these compounds to undergo biochemical modifications was also described [53,54]. However, the literature also does not present a systematic correlation of changes in aromaticity calculated using different descriptors with the chemical and biochemical properties of cathinones.

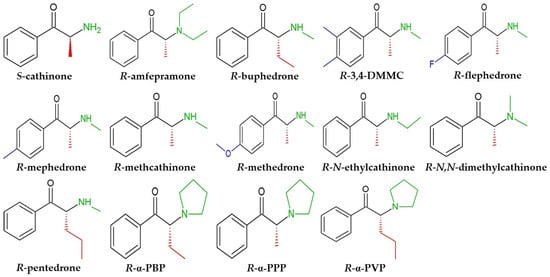

Therefore, this study attempts to correlate the substituent effect and aromaticity parameters of cathinones, calculated using density functional theory (DFT), with cytotoxic activities of these compounds. To avoid inconsistent experimental values from different research groups, data on the cytotoxic activities of 13 cathinones (see Figure 2) measured using SH-SY5Y neuronal cells were used. Analyzed cathinone derivatives were modified at different positions by substituents with different electron-donating/withdrawing properties [34]. The obtained data deepen our understanding of the SAR in the studied group of cathinones and may be potentially useful in forensic medicine, criminalistics, and in the context of further chemical modification of these substances to produce more effective medicines. The results of this study could also be useful in further theoretical studies of SARs for other known and new cathinone derivatives, and could optimize the design and interpretation of experimental results for studies on the biological activities of cathinones.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of cathinone and its studied derivatives.

2. Materials and Methods

All calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 C.02 program package [55]. Density functional theory was used to predict structural, electronic, and spectroscopic parameters for all studied cathinones. All molecular structures were created in the GaussView program [56] according to experimental study [34]. Since the molecules of the studied compounds have flexible structural fragments, one common conformation for all derivatives was chosen based on available crystallographic data [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. In the case of flephedrone, the lowest energy conformer was chosen based on literature conformational studies [65]. All molecules were then optimized at the B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of the theory with tight convergence criterion (geometries are in Tables S3 and S4 of the Supporting Information) [66,67,68,69]. This methodology has demonstrated acceptable accuracy of results and usage of computational facilities in the modeling of structural, spectroscopic, aromatic, and substituent effect parameters of small and medium-sized organic molecules [53,70,71]. Lack of imaginary harmonic frequencies was used as a criterion to obtain equilibrium structures. Other studied parameters were calculated in the same environments and at the same level of theory, such as geometric optimization. Since the analyzed compounds have an amine end, they can undergo protonation or deprotonation depending on the pH of the environment. Experimental data show that the pKa of different cathinones varies within the range of 8–10 [72]. Therefore, at physiological pH (5.5–7.5) [73,74], the cationic form of cathinone and its analyzed derivatives should predominate. To examine the influence of the polarity of the cellular environment on studied theoretical parameters of cathinones, all compounds were modeled in two environments: the gas phase as a simplified model of the nonpolar cellular environment and water using the polarizable-continuum model (PCM) [75] as a simplified model of polar physiological environments. In the gas phase, cathinones were considered as neutral molecules and, in water, as cations.

As can be seen from Figure 2, a molecule of each studied cathinone derivative had one chiral center. Therefore, each of the compounds can be represented in the R and S configurations. The literature indicates that only the S-configuration of cathinone exhibits biological activity [1,33]. For the remaining cathinones, data are limited and often ambiguous [35,76,77,78]. The experimental study from which the studied group of cathinones was taken [34] does not provide data on the configuration of psychotropic substances. To determine the influence of configuration on the values of theoretical parameters, calculations of charge of the substituent active region (cSAR) [79,80] were performed at a lower level of theory B3LYP/6-311++G** in water (PCM) [66,67,68,81]. The values for both R/S configurations of each compound (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information) differed slightly. Consequently, for effective use of the calculation facilities, only the R configurations of studied derivatives were considered.

The substituent effect (SE) on the electronic structure of all studied cathinones was analyzed by calculation of the charge of the substituent active region (cSAR) [79,80] and comparing values between studied compounds. In general, cSAR(X) is calculated according to Equation (1):

where q(X) is the sum of the charges of the atoms included in the analyzed substituent X, and q(Cipso) is the charge of the carbon atom to which the substituent X is attached. The cSAR(X) value is positive for electron-donating substituents and negative for electron-withdrawing ones. Its absolute value indicates the strength of each electron-donating or electron-withdrawing effect. Hirshfeld atomic charges were used for cSAR calculations [82]. A systematic theoretical study demonstrates the reliability of these types of atomic charges in the context of the SE calculation [83]. The authors drew attention to the stability of these parameter values toward unphysical charge perturbations and best performance compared with all other studied computational descriptors, including several commonly used basis set-based schemes as Natural Population Analysis [83].

cSAR(X) = q(X) + q(Cipso),

Since cathinone could be substituted at several sites—(1) at the benzene ring, (2) at the aliphatic chain of the asymmetric carbon, and (3) at the amine end—two cSAR parameters were considered in this research according to Equations (2) and (3):

where cSAR(Y) is the sum of carbonyl carbon C(sp2) and oxygen O charges, the total charge of aliphatic moiety RA, and amine end N attached to the asymmetric carbon atom C*.

where cSAR(CO) is the sum of carbonyl carbon C(sp2) and oxygen O charges. Since cathinones were considered in cationic form in water, in this case the charge of the added hydrogen atom was also taken into account in the cSAR(Y) calculations.

cSAR(Y) = q(C(sp2)) + q(O) + q(RA) + q(N) + q(C*),

cSAR(CO) = q(C(sp2)) + q(O),

To evaluate the substituents’ effects on the distribution of electron density in the benzene ring of cathinones, a number of aromaticity predictors were considered. First, the geometry-based Harmonic Oscillator Model of Aromaticity (HOMA) indexes [84,85] were calculated according to Equation (4):

where n is the number of bonds in the ring (n = 6 for benzene). α is an empirical normalization constant, individual to each bond type forming the ring. While the benzene cycle is formed by only CC type bonds, α = 257.7 [84,85]. Ropt is the reference bond length (in Å) in an “ideal aromatic” system. Ropt = 1.388 Å for the CC bond type [84,85]. Ri is the predicted bond length (in Å) for the analyzed ring. Next, the magnetic index of aromaticity—Nuclear Independent Chemical Shifts (NICS)—was estimated for all studied cathinones. It was calculated as three individual parameters: chemical shift values in the center of the cathinones’ benzene ring [NICS(0)]; chemical shift values 1 Å above the center of the benzene ring [NICS(1)], and their Z-component [NICS(1)zz]. The change in all aromaticity parameters caused by the SE was estimated as the difference between the values for cathinone and benzene. Structural optimization and aromaticity values calculations for benzene were performed at the same level of theory and in the same environments as for cathinones.

3. Results and Discussion

As result of systematic theoretical studies, two data sets were generated: neutral cathinones in the gas phase and their cationic forms in water. As can be seen from Figure 2, the structures were substituted with different functional groups at various positions within the molecule’s backbone. Consequently, it was quite difficult to compare all the data simultaneously. For this reason, the results were divided into several sets based on the experimentally established structure–activity correlation in Soares et al. [34]. It is worth noting that our current theoretical studies utilized a simplified polarizable-continuum model (PCM) of solvation. This choice was driven by the introductory nature of this research. At this stage, changes in the SE parameters and associated aromaticity values were examined in two environments with extreme properties—highly polar and non-polar. This allowed us to examine how protonation influences the theoretical parameter values and whether they correlate with in vitro biological activity for both neutral and protonated forms. Studying the substituent effect and associated aromaticity parameters for protonated cathinones could be helpful in interpreting their interactions with biomolecules in polar physiological environments [86,87]. Conversely, understanding the SEs and aromaticity parameters of neutral forms is important for studying the permeability of these drugs across biomembranes (especially in the context of crossing the blood–brain barrier) [4]. Future studies are planned to more thoroughly examine the influence of the pH gradient on the SE parameters and aromaticity of cathinones.

3.1. cSAR Values vs. Cytotoxicity of Cathinone Derivatives

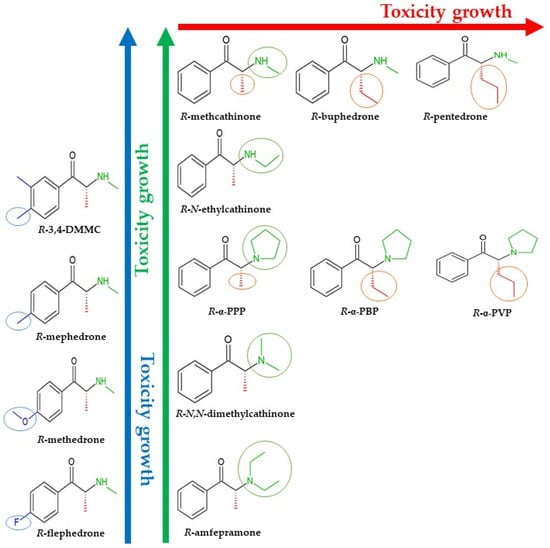

According to the results of experimental studies by Soares et al. [34], the analyzed cathinones could be divided into several sets by the modification of the cathinone at different positions and growing cytotoxic activity (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cytotoxic activity change trends for cathinones with structural modifications at different positions according to the experimental data of Soares et al. [34].

To simplify interpretation of the results, data were divided into groups according to the structure–cytotoxicity trends in Figure 3.

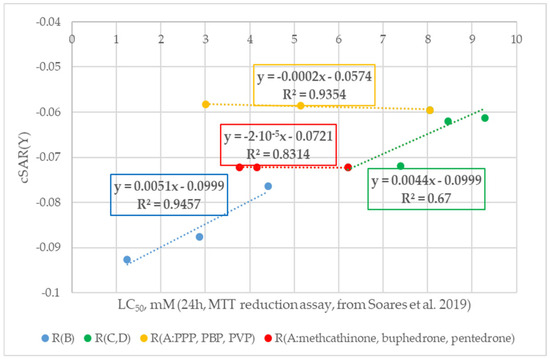

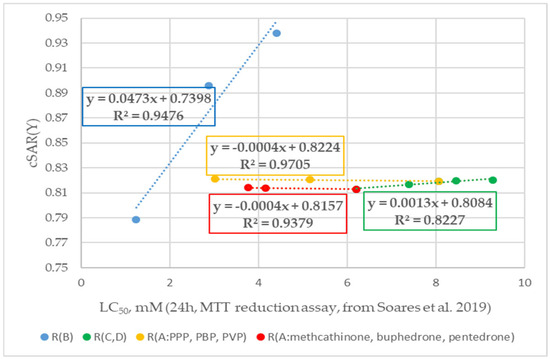

When analyzing the cSAR(Y) data (see Figure 4), it is worth noting that all N-containing substituents of cathinones in the neutral form were characterized by weak electron-withdrawing properties.

Figure 4.

Change trends in cSAR(Y) values with a decrease in cytostatic properties and modifications of different fragments of the neutral cathinone molecule (experimental cytotoxicity data from [34]). R(B) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RB position; R(C,D) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RC and RD positions; subgroup R(A:PPP, PBP, PVP) corresponds to α-PPP, α-PBP, and α-PVP with the same pyrrolidine ring at the RC and RD positions and changing aliphatic chain at the RA position, respectively; subgroup R(A:methcathinone, buphedrone, pentedrone) corresponds to methcathinone, buphedrone, and pentedrone with the same aminomethyl end and changing aliphatic chain at the RA position.

As can be seen from Figure 4, the greatest change in the cSAR(Y) value was observed for cathinones with p-substitution (position RB according to Figure 1, blue curve in Figure 4) and amine end modifications (positions RC and RD according to Figure 1, green curve in Figure 4). On the other hand, elongation of the aliphatic chain (position RA according to Figure 1) has a minimal effect on the substituent electron-withdrawing effect strength (red and orange curves in Figure 4). Analyzing the blue curve in Figure 4, it is worth noting the upward trend in the electron-donating properties of the substituent at the RB position and cathinone derivative cytostatic properties. Only methedrone is outside the trend (for this reason, it is not represented on the curve, but the numerical data can be found in Table S2 in the Supporting Information), both in terms of the cSAR(Y) value and the substituent electron-donating properties. According to Hammett’s experimental SE constants σp, the methoxy group possesses stronger electron-donating properties compared to the methyl substituent [88]. A possible reason for the discrepancy in this value may be the fact that the Hammett’s constants σp were calculated for p-substituted benzoic acids. In the case of cathinones, -COOH is replaced by a complex N-containing substituent. It is also worth noting that in the case of 3,4-DMMC, substitution of two methyl groups on the benzene ring enhances its cytostatic properties and the electron-withdrawing properties of the N-containing substituent compared to mephedrone. Analyzing the green curve, it is worth noting a similar increase in the cytostatic properties of the cathinone derivatives with a decrease in the electron-donating properties of the aminoalkyl substituent (according to the Hammett σp values [88,89]). It is worth noting, however, that the cSAR(Y) values do not fully follow the trend with the increasing electron-donating properties of all aminoalkyl substituents. According to σp values, electron-donating properties increase as follows: -NHC2H5 → -NHCH3 → -N(C2H5)2 → -N(CH3)2. In the case of the calculated cSAR(Y) data, the electron-donating SE increase follows this trend: -NHCH3 → -NHC2H5 → -N(CH3)2 → -N(C2H5)2. This phenomenon could be explained by the effect of the carbonyl group and the aliphatic chain, preceding the aminoalkyl fragment of the substituent. This structural modification could affect N-end electron-donating properties (in the experimental σp values trend, the aminoalkyl substituent was attached directly to the benzene ring). It is also worth mentioning that the cSAR(Y) values were compared with the Hammett σp parameter, rather than σm, since other theoretical studies have noted a better correlation between cSAR values and σp [53]. Analyzing the orange and red curves in Figure 4, it is worth noting that the trend of cSAR(Y) changes is similar to the Hammett σp values: the cSAR(Y) value decreases with decreasing electron-donating properties of the aliphatic chain. It is also worth noting that the small decrease is consistent with the small differences in the σp constants: −0.17 for -CH3, −0.15 for C2H5, and −0.13 for -C3H7. Analyzing the blue and green curves, it is worth noting a certain relationship between the results. All cathinones substituted in the RB positions (blue curve in Figure 4) had an aminomethyl terminal group. The appearance of the RB substituent with increasing electron-donating properties led to a systematic increase in the electron-accepting properties of the N end compared to methcathinone (RB=H). Analyzing the overall trend of the results, it is worth noting that the cSAR(Y) value decreased with increasing cathinone cytostatic properties.

Analyzing the results for the cationic form of selected cathinone derivatives, it is worth paying attention to Figure 5. As can be seen from the cSAR(Y) values, protonation of the N end leads to a change in the substituent effect from electron withdrawing to electron donating. However, the results trend is consistent with values of the neutral forms: the cytotoxicity of cathinone derivatives increases with increasing electron density at the N end (i.e., a decrease in the cSAR(Y) value for the cationic form). Similar to neutral forms, the decisive effect of the presence of the RB substituent (blue curve in Figure 5) and the growing cytotoxic activity with increases in its electron-donating properties is observed. The inconsistency of the results for methedrone (RB=OCH3, numerical values can be found in Table S2 of the SI) with the Hammett constants σp trend [88,89] is also saved. It is worth noting that protonation of the nitrogen atom reduces the contribution of the aminoalkyl and pyrrolidine moieties to the strength of the N-containing substituent effect (a decrease in the slope of the green curve compared to the curve for the neutral form). However, the trend of the results coincides with the curves of the studied neutral forms of cathinones. The small contribution of the aliphatic chain extension at the RA position, consistent with the trend of the Hammett constants σp and the curves for the neutral forms, is also retained (red and orange curves in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Change trends in cSAR(Y) values with decreasing cytostatic properties and with modifications of different fragments of cationic forms of cathinone molecules (experimental cytotoxicity data from [34]). R(B) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RB position; R(C,D) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RC and RD positions; subgroup R(A:PPP, PBP, PVP) corresponds to α-PPP, α-PBP, and α-PVP with the same pyrrolidine ring at the RC and RD positions and changing aliphatic chain at the RA position, respectively; subgroup R(A:methcathinone, buphedrone, pentedrone) corresponds to methcathinone, buphedrone, and pentedrone with the same aminomethyl end and changing aliphatic chain at the RA position.

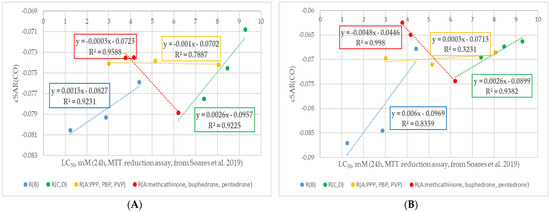

The mechanisms underlying the cytotoxic effects of cathinone and its derivatives remain poorly described in the literature [90]. Recent experimental studies demonstrate an increase in cytotoxicity of some cathinone derivatives with the reduction of their β-keto group to a hydroxyl group [90] in cells of the same SH-SY5Y cell line, as in the research of the Soares group [34]. The mechanism of this metabolic process at the molecular level remains unclear. In this case, the molecular structure of the cathinone derivatives and the electron density of its carbonyl group are crucial. When analyzing the electron-withdrawing capacity of the carbonyl group of the studied cathinones, it is worth paying attention to Figure 6 (main numerical data are presented in Table S2 of the SI).

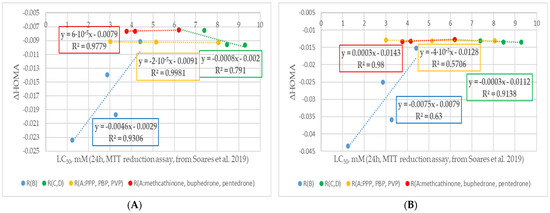

Figure 6.

Change trends in cSAR(CO) values with decreasing cytostatic properties and modifications of different fragments of the (A) neutral and (B) cationic forms of cathinone molecules (experimental cytotoxicity data from [34]). R(B) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RB position; R(C,D) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RC and RD positions; subgroup R(A:PPP, PBP, PVP) corresponds to α-PPP, α-PBP, and α-PVP with the same pyrrolidine ring at the RC and RD positions and changing aliphatic chain at the RA position, respectively; subgroup R(A:methcathinone, buphedrone, pentedrone) corresponds to methcathinone, buphedrone, and pentedrone with the same aminomethyl end and changing aliphatic chain at the RA position.

As can be seen from Figure 6A, the trends in cSAR(CO) changes for neutral forms of cathinones are similar to those of cSAR(Y). The C=O groups were characterized by electron-withdrawing properties. It is worth noting that this strengthening effect correlates with the growing experimental cytotoxicity values. It is worth noting that the strength of the electron-donating properties of the RB substituent of the cathinones (according to Figure 1) and the modification of the RC and RD substituents provide the highest effect on the cSAR(CO) values. It is worth noting the ambiguous contribution of the aliphatic chain at the RA position: in cathinones with an aminoalkyl end (red curve), it is higher compared to cathinones with a pyrrolidine ring (orange curve). The trend of increasing electron-withdrawing properties with an increase in cytotoxicity is also observed for cationic forms of studied cathinones (see Figure 6B). Note the greater difference between the cSAR(CO) values for the most toxic 3,4-DMMC and the least toxic amfepramone in cationic forms compared to the neutral forms. The direct cSAR(CO) value of the 3,4-DMMC cation was higher than that of its neutral form, while the cSAR(CO) value of the amfepramone cation was lower than that of its neutral form. For the cationic forms, the effect of the aliphatic chain elongation at the RA position was insignificant for both analyzed trends. In the case of the RB-substituent effect in both forms of cathinones, methedrone’s cSAR(CO) value was off-trend similarly to the cSAR(Y) values.

Obtained results suggest a significant effect of growing electron density at the N end of the cathinone derivative on its cytotoxicity strength. It is also worth noting the trend of N-end electron density declines with expanding the structure of the aminoalkyl and pyrrolidine end of the N-substituent. It could be expected that both the steric effect and electronic properties of the N-substituent are directly related to the formation of interactions of cathinones with molecular targets and, as a consequence, a change in their cytotoxic properties. Experimental studies of cathinones are limited by their psychotropic potential. Consequently, limited data were found in the literature reporting the induction of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species production, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis as the main cytotoxic mechanisms of cathinones [21,86,87]. However, in study [91], inhibition of acetylcholinesterase was examined in vitro and in silico as one of the mechanisms of cytotoxicity in the SH-SY5Y cell line. Molecular docking results from [91] demonstrate that the N end is one of leading contributions to the inhibitory effect.

It is also worth noting the direct correlation between growth in cytotoxicity and the increased electron-withdrawing properties of the C=O group in the studied cathinones. It is suspected that the accumulation of electron density leads to the reactivation of this group for further reduction to the -OH group, as mentioned in experimental study [90], which also leads to the enhancement in cytotoxic activity.

3.2. SE vs. Aromaticity and Cytotoxicity of Cathinone Derivatives

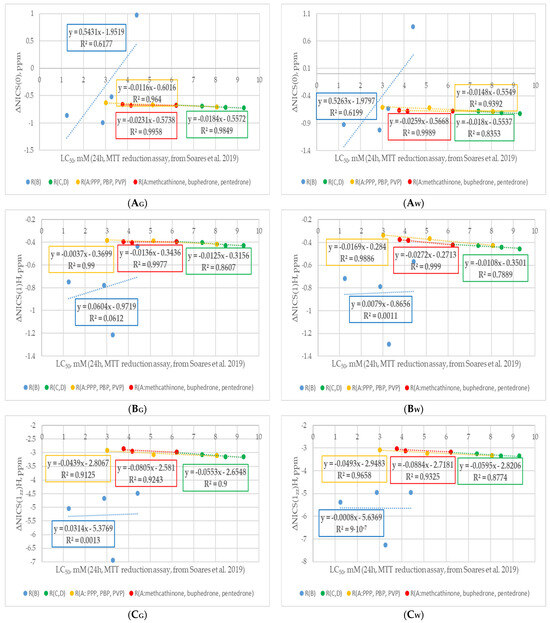

Changes in electron density delocalization in aromatic rings could significantly affect chemical reactivity of the molecules and their ability to form weak interactions with the environment. Consequently, biological properties could also be significantly changed [92,93,94]. In the case of cathinone and its derivatives and which benzene ring could be substituted at various positions RA–RD, it is important to understand whether this affects aromaticity and whether the changes are significant. To answer this question for the analyzed group of cathinones, a number of quantitative aromaticity descriptors were considered: HOMA, NICS(0), NICS(1), and NICS(1zz). Since the analyzed compounds have an asymmetric N-containing substituent (see Figure 2), the chemical environment of the lower and upper planes of the benzene ring will differ: on one side, there will be a RA substituent and, on the other, a hydrogen atom. To examine this effect, the NICS(1) and NICS(1zz) parameters were calculated for both planes of the benzene ring: NICS(1)H and NICS(1zz)H for the plane with the hydrogen atom and NICS(1)Aliph and NICS(1zz)Aliph for the plane with the RA substituent. NICS and HOMA parameters are comparative characteristics between the analyzed system and the ideal aromatic cycle. For this reason, we compared these parameters of cathinones with the data for benzene, calculated at the same level of theory and in the same environments as the analyzed drugs. Since a direct comparison of the direct values for cathinones and benzene could be difficult, we considered the trends in their differences, ΔNICS and ΔHOMA. Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the change trends of the ΔNICS and ΔHOMA values for the neutral and cationic forms of cathinones, respectively. The data are divided into sets similar to the cSAR parameters analysis, based on structural modifications in different positions of cathinone molecules (see Figure 3). To simplify the analysis, the results for each parameter are presented in pairs—data for the neutral and cationic forms of cathinones. Curves for neutral molecules are labeled with the “G” symbol in the caption below each figure, while those for cationic molecules are labeled with the “W” symbol. The numerical values of NICS and HOMA for benzene and the analyzed cathinone derivatives can be found in Table S2 in the Supporting Information.

Figure 7.

Changes in ΔNICS values: (A) ΔNICS(0); (B) ΔNICS(1); (C) ΔNICS(1zz); (D) ΔNICS(1)Aliph; (E) ΔNICS(1zz)Aliph of studied cathinones with decreasing cytostatic properties and modifications of different fragments. Figures with “G” in the name refer to neutral forms in the gas phase, while those with “W” refers to cations in water (PCM). Experimental cytotoxicity data from [34]. R(B) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RB position; R(C,D) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RC and RD positions; subgroup R(A:PPP, PBP, PVP) corresponds to α-PPP, α-PBP, and α-PVP with the same pyrrolidine ring at the RC and RD positions and changing aliphatic chain at RA position, respectively; subgroup R(A:methcathinone, buphedrone, pentedrone) corresponds to methcathinone, buphedrone, and pentedrone with the same aminomethyl end and changing aliphatic chain at the RA position.

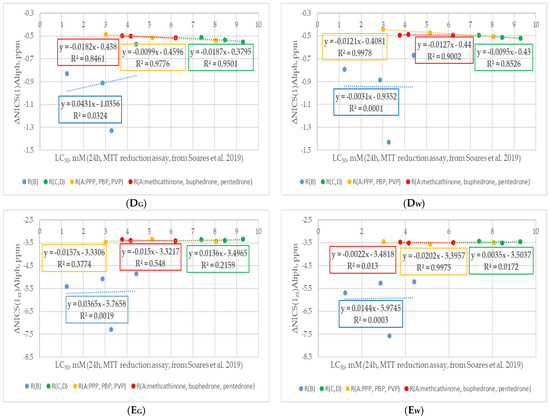

Figure 8.

Change trends in ΔHOMA values with a cytotoxicity decrease and modifications of different fragments of the (A) neutral and (B) cationic forms of cathinone molecules (experimental cytotoxicity data from [34]). R(B) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RB position; R(C,D) corresponds to cathinone derivatives modified at the RC and RD positions; subgroup R(A:PPP, PBP, PVP) corresponds to α-PPP, α-PBP, and α-PVP with the same pyrrolidine ring at the RC and RD positions and changing aliphatic chain at RA position, respectively; subgroup R(A:methcathinone, buphedrone, pentedrone) corresponds to methcathinone, buphedrone, and pentedrone with the same aminomethyl end and changing aliphatic chain at the RA position.

Analyzing the trend in ΔNICS values (see Figure 7), it is worth noting the different effects of substituents at different positions in cathinone structure. Substitution at the RB position (blue curves) provided the largest effect on all ΔNICS values. This could be explained by the direct substitution of the benzene ring by each of the B substituents. Consequently, the change in the electron-donating/accepting properties of these substituents will be most noticeable during the distribution of electron density and, consequently, the change in ring aromaticity. A decrease in cathinone aromaticity values with an increasing inductive electron-donating effect of the substituent was observed. Similar to the cSAR values trend, only methedrone with a methoxy substituent at the RB position was behind the trend. This phenomenon was less pronounced in the case of ΔNICS(0) compared to ΔNICS(1) values, which can be seen from the decreasing R2 values for the corresponding blue curves in Figure 7. Therefore, it could be assumed that the possible reason for the deviations in the cSAR and ΔNICS(1) data for the methoxy substituent of methedrone is the decrease in its π-donor properties in the p-position to the complex N-substituent. In the case of flephedrone with RB=F, an increase in aromaticity value in the middle of the ring can be observed, as indicated by the positive ΔNICS(0) value. This could be explained by the dominance of the electron-donating resonance effect over the electron-withdrawing inductive effect of the fluorine substituent in this chemical environment. In the case of aromaticity indices at a distance of 1 Å from the center of the benzene ring, ΔNICS(1)H, ΔNICS(1zz)H, ΔNICS(1)Aliph, ΔNICS(1zz)Aliph, a decrease in their values is observed in all RB-substituted cathinones. Analyzing the RB data set for the neutral and cationic forms of cathinones, it is worth noting their convergence for all ΔNICS parameters. Minor changes in all ΔNICS parameters were observed in three other curves: cathinones with changing RC and RD substituents (green curves), cathinones with RA-aliphatic chain elongation, and a pyrrolidine ring (yellow curves) or an aminoalkyl end (red curves) in molecular structure. The trends were consistent for both neutral and cationic forms of cathinones. Such small differences could be explained by a relatively small modification of the electron-withdrawing/donating properties of the N-containing substituent with a minor structural modification of its RA, RC, and RD fragments. Another reason could also be the distance of the substituents in the RA, RC, and RD positions from the benzene ring and, as a consequence, their decreasing influence on the delocalization of electron density and the associated aromaticity in the ring and above it. It was noted that the values of ΔNICS(1)Aliph and ΔNICS(1zz)Aliph were less sensitive to the change in RA, RC, and RD substituents than the ΔNICS(1)H and ΔNICS(1zz)H values. It was noted that in each derivative of these subgroups on the H side of benzene there was a hydrogen atom at C* position. The H atom was located near the C=C bond of the benzene ring at a distance of 2.6–2.7 Å. It can be assumed that the decrease in aromaticity according to the ΔNICS(1)H and especially the ΔNICS(1zz)H values could be caused by the delocalization of the π-electron density in the weak interaction C*-H··π. In summary, it is worth noting the common trend across all curves: a decrease in aromaticity with increasing cathinone cytotoxicity. Therefore, it is suspected that a decrease in cathinone derivative aromaticity leads to increased chemical reactivity and, consequently, its greater potential for toxic biological activity. On the other hand, it is also worth noting that non-covalent interactions with the aromatic ring of cathinones also played an important role in the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and the formation of associated cytotoxic effects [91].

Analyzing changes in the aromaticity of cathinones with substitution in different positions using the HOMA descriptor, it is worth paying attention to Figure 8. It could be seen that the general trend of the curves for cathinones substituted at the RA, RB, RC, and RD positions coincides with the trends for the ΔNICS values. The most significant effect is observed with substitution at the RB position. Similar to the ΔNICS and cSAR values, only the methedrone ΔHOMA value is outside the trend for both neutral and cationic forms of the drug. Modification at the RA, RC, and RD positions leads to small but systematic changes in the ΔHOMA values. A general trend of decreasing aromaticity with increasing cytotoxicity of the cathinones was observed. It is worth noting that the change in ΔHOMA values is more pronounced for the cationic forms of cathinones compared to the neutral ones.

4. Conclusions

This research attempted to establish a correlation between the theoretical parameters of the substituent effect and aromaticity with the cytotoxic activity of selected cathinone derivatives. To avoid inconsistences in the experimental data obtained by different authors, the cytotoxicity values were taken from a single data series of one research group. An increase in the electron-withdrawing properties (neutral forms of cathinone derivatives) and a decrease in the electron-donating properties (cationic forms of cathinone derivatives) of the N-substituent with growing cytotoxic activity of the drug were noted. It is suspected that an increasing electron density, together with the steric parameters of this substituent, play a significant role in shaping the cytotoxic potential of the analyzed cathinones. An increase in the electron-withdrawing properties of C=O with intensifying cytotoxicity of the cathinone derivative was also noted. It is suspected that this trend leads to increasing reduction ability of the carbonyl fragment and, as a consequence, growing cytotoxic potential of the drug. A decrease in aromaticity values was noted both in the plane and at a distance of 1 Å up and down from the benzene ring of cathinones with their increasing cytotoxicity. This could indicate increasing reactivity of the drug molecule and, as a consequence, an increased capacity for biochemical reactions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010526/s1, Table S1: Effect of R/S-configuration on the cSAR values of several cathinones (singlet cations) optimized in water (PCM) at the B3LYP/6-311++G** level of theory, Table S2: cSAR, NICS, and HOMA parameters for all studied cathinone derivatives (singlets in neutral and cationic forms). NICS and HOMA values of benzene as model aromatic cycle are also added. Cathinones were optimized at the B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of the theory in vacuum (neutral molecules) and water (PCM, cations); Table S3: Structures of cathinone and its derivatives (singlets in neutral form) optimized in vacuum at the B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of the theory. Table S4: Structures of cathinone and its derivatives (singlets in cationic form) optimized in water (PCM) at the B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ level of the theory.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M. and T.K.; methodology, N.M. and T.K.; software, N.M.; validation, N.M. and T.K.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, N.M.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, N.M. and T.K.; visualization, N.M.; supervision, T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

N.M. thanks Paweł A. Wieczorkiewicz for interesting scientific discussions and helpful methodological recommendations. Created using resources provided by the Wroclaw Centre for Networking and Supercomputing (http://wcss.pl). Grant no. hpc-titanium-1721124296. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the reviewers for their very helpful criticisms and suggestions leading to significant improvement of the original manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gebissa, E. Khat in the Horn of Africa: Historical Perspectives and Current Trends. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 132, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawilska, J.B.; Wojcieszak, J. α-Pyrrolidinophenones: A New Wave of Designer Cathinones. Forensic Toxicol. 2017, 35, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszak, J.; Andrzejczak, D.; Woldan-Tambor, A.; Zawilska, J.B. Cytotoxic Activity of Pyrovalerone Derivatives, an Emerging Group of Psychostimulant Designer Cathinones. Neurotox. Res. 2016, 30, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregat-Safont, D.; Barneo-Muñoz, M.; Carbón, X.; Hernández, F.; Martinez-Garcia, F.; Ventura, M.; Stove, C.P.; Sancho, J.V.; Ibáñez, M. Understanding the Pharmacokinetics of Synthetic Cathinones: Evaluation of the Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability of 13 Related Compounds in Rats. Addict. Biol. 2021, 26, e12979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyrer-Jackson, J.M.; Nagy, E.K.; Olive, M.F. Cognitive Deficits and Neurotoxicity Induced by Synthetic Cathinones: Is There a Role for Neuroinflammation? Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hout, M.C. Kitchen Chemistry: A Scoping Review of the Diversionary Use of Pharmaceuticals for Non-Medicinal Use and Home Production of Drug Solutions. Drug Test. Anal. 2014, 6, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatch, M.B.; Rutledge, M.A.; Forster, M.J. Discriminative and Locomotor Effects of Five Synthetic Cathinones in Rats and Mice. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger-Gobeil, C.; St-Onge, M.; Laliberté, M.; Auger, P.L. Seizures and Hyponatremia Related to Ethcathinone and Methylone Poisoning. J. Med. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrick, B.J.; Wilson, J.; Hedge, M.; Freeman, S.; Leonard, K.; Aaron, C. Lethal Serotonin Syndrome After Methylone and Butylone Ingestion. J. Med. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daziani, G.; Lo Faro, A.F.; Montana, V.; Goteri, G.; Pesaresi, M.; Bambagiotti, G.; Montanari, E.; Giorgetti, R.; Montana, A. Synthetic Cathinones and Neurotoxicity Risks: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.H.P.; Mariotto, L.S.; Castro, J.S.; Peruquetti, P.H.; Silva-Junior, N.C.; Bruni, A.T. Acute, Chronic, and Post-Mortem Toxicity: A Review Focused on Three Different Classes of New Psychoactive Substances. Forensic Toxicol. 2023, 41, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frew, J.R.; Goodman, D.; Brunette, M. Perinatal Outcomes of Synthetic Cathinone (“Bath Salts”) Use in Pregnancy: A Case Series. J. Subst. Use 2024, 29, 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecco, G.G.; Kisor, D.F.; Magura, J.S.; Sprague, J.E. Impact of Common Clandestine Structural Modifications on Synthetic Cathinone “Bath Salt” Pharmacokinetics. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 328, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsalan, R.; Varghese, B.; Soman, D.; Buckmaster, J.; Yew, S.; Cooper, D. Multi-Organ Dysfunction Due to Bath Salts: Are We Aware of This Entity? Intern. Med. J. 2017, 47, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, C.L.; Wetzel, D.R.; Wijdicks, E.F.M. Devastating Delayed Leukoencephalopathy Associated with Bath Salt Inhalation. Neurocrit Care 2016, 24, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojcieszak, J.; Andrzejczak, D.; Kedzierska, M.; Milowska, K.; Zawilska, J.B. Cytotoxicity of α-Pyrrolidinophenones: An Impact of α-Aliphatic Side-Chain Length and Changes in the Plasma Membrane Fluidity. Neurotox. Res. 2018, 34, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, L.J.; Glennon, R.A.; Negus, S.S. Synthetic Cathinones: Chemical Phylogeny, Physiology, and Neuropharmacology. Life Sci. 2014, 97, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.A.; Negus, S.S.; Poklis, J.L.; Blough, B.E.; Banks, M.L. Cocaine-like Discriminative Stimulus Effects of Alpha-Pyrrolidinovalerophenone, Methcathinone and Their 3,4-Methylenedioxy or 4-Methyl Analogs in Rhesus Monkeys. Addict. Biol. 2017, 22, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Gratacós, N.; Ríos-Rodríguez, E.; Pubill, D.; Batllori, X.; Camarasa, J.; Escubedo, E.; Berzosa, X.; López-Arnau, R. Structure–Activity Relationship of N-Ethyl-Hexedrone Analogues: Role of the α-Carbon Side-Chain Length in the Mechanism of Action, Cytotoxicity, and Behavioral Effects in Mice. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Bouitbir, J.; Liechti, M.E.; Krähenbühl, S.; Mancuso, R.V. Para-Halogenation of Amphetamine and Methcathinone Increases the Mitochondrial Toxicity in Undifferentiated and Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, H.S.; Philp, M.; Simone, M.; Witting, P.K.; Fu, S. Synthetic Cathinones Induce Cell Death in Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y Cells via Stimulating Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pail, P.B.; Costa, K.M.; Leite, C.E.; Campos, M.M. Comparative Pharmacological Evaluation of the Cathinone Derivatives, Mephedrone and Methedrone, in Mice. NeuroToxicology 2015, 50, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, H.H.; Kraemer, T.; Springer, D.; Staack, R.F. Chemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Hepatic Metabolism of Designer Drugs of the Amphetamine (Ecstasy), Piperazine, and Pyrrolidinophenone Types: A Synopsis. Ther. Drug Monit. 2004, 26, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, P.; Davidson, J.T.; Still, K.; Kool, J.; Kohler, I. In Vitro Metabolism of Cathinone Positional Isomers: Does Sex Matter? Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 5403–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabregat-Safont, D.; Mardal, M.; Sancho, J.V.; Hernández, F.; Linnet, K.; Ibáñez, M. Metabolic Profiling of Four Synthetic Stimulants, Including the Novel Indanyl-Cathinone 5-PPDi, after Human Hepatocyte Incubation. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020, 10, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagmann, L.; Manier, S.K.; Eckstein, N.; Maurer, H.H.; Meyer, M.R. Toxicokinetic Studies of the Four New Psychoactive Substances 4-Chloroethcathinone, N-Ethylnorpentylone, N-Ethylhexedrone, and 4-Fluoro-Alpha-Pyrrolidinohexiophenone. Forensic Toxicol. 2020, 38, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glicksberg, L.; Winecker, R.; Miller, C.; Kerrigan, S. Postmortem Distribution and Redistribution of Synthetic Cathinones. Forensic Toxicol. 2018, 36, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, L.G.; Kochelek, K.; Keasling, R.; Brown, S.D.; Pond, B.B. The Pharmacokinetic Profile of Synthetic Cathinones in a Pregnancy Model. Neurotoxicology Teratol. 2017, 63, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, S. The Use of Bupropion SR in Cigarette Smoking Cessation. COPD 2008, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M.; Rush, A.J.; Thase, M.E.; Clayton, A.; Stahl, S.M.; Pradko, J.F.; Johnston, J.A. 15 Years of Clinical Experience with Bupropion HCl: From Bupropion to Bupropion SR to Bupropion XL. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2005, 7, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.; Gardos, G.; Cole, J.O. A Controlled Evaluation of Pyrovalerone in Chronically Fatigued Volunteers. Int. Pharmacopsychiatry 2017, 8, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaton, D.A.; Duncan, L.J.P.; Rose, K.; Scott, A.M. Diethylpropion in the Treatment of “Refractory” Obesity. Br. Med. J. 1961, 1, 1009–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiang, M.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J. Khat Promotes Human Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cell Apoptosis via Mitochondria and MAPK-Associated Pathways. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 3947–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.; Costa, V.M.; Gaspar, H.; Santos, S.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Carvalho, F.; Capela, J.P. Structure-Cytotoxicity Relationship Profile of 13 Synthetic Cathinones in Differentiated Human SH-SY5Y Neuronal Cells. NeuroToxicology 2019, 75, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paškan, M.; Rimpelová, S.; Svobodová Pavlíčková, V.; Spálovská, D.; Setnička, V.; Kuchař, M.; Kohout, M. 4-Isobutylmethcathinone—A Novel Synthetic Cathinone with High In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Strong Receptor Binding Preference of Enantiomers. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, T.; Morikawa, Y.; Kamata, K.; Shibata, A.; Miyazono, H.; Sasajima, Y.; Suenami, K.; Sato, K.; Takekoshi, Y.; Endo, S.; et al. α-Pyrrolidinononanophenone Provokes Apoptosis of Neuronal Cells Through Alterations in Antioxidant Properties. Toxicology 2017, 386, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.J.; Amaral, C.; Correia-da-Silva, G.; Duarte, J.A.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Carvalho, F.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Carvalho, M. Methylone and MDPV Activate Autophagy in Human Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y Cells: A New Insight into the Context of β-Keto Amphetamines-Related Neurotoxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 3663–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, Y.; Miyazono, H.; Kamase, K.; Suenami, K.; Sasajima, Y.; Sato, K.; Endo, S.; Monguchi, Y.; Takekoshi, Y.; Ikari, A.; et al. Protective Effect of Aldo–Keto Reductase 1B1 Against Neuronal Cell Damage Elicited by 4′-Fluoro-α-Pyrrolidinononanophenone. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, Y.; Miyazono, H.; Sakai, Y.; Suenami, K.; Sasajima, Y.; Sato, K.; Takekoshi, Y.; Monguchi, Y.; Ikari, A.; Matsunaga, T. 4′-Fluoropyrrolidinononanophenone Elicits Neuronal Cell Apoptosis Through Elevating Production of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species. Forensic Toxicol. 2021, 39, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y.; Morikawa, Y.; Nagao, Y.; Hattori, J.; Suenami, K.; Yanase, E.; Takayama, T.; Ikari, A.; Matsunaga, T. 4′-Iodo-α-Pyrrolidinononanophenone Provokes Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cell Apoptosis Through Downregulating Nitric Oxide Production and Bcl-2 Expression. Neurotox. Res. 2022, 40, 1322–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marszalek-Grabska, M.; Lemieszek, M.K.; Chojnacki, M.; Winiarczyk, S.; Jakubowicz-Gil, J.; Zarzyka, B.; Pawelec, J.; Kotlinska, J.H.; Rzeski, W.; Turski, W.A. Cell-Specific Vulnerability of Human Glioblastoma and Astrocytoma Cells to Mephedrone—An In Vitro Study. Molecules 2025, 30, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszalek-Grabska, M.; Zakrocka, I.; Budzynska, B.; Marciniak, S.; Kaszubska, K.; Lemieszek, M.K.; Winiarczyk, S.; Kotlinska, J.H.; Rzeski, W.; Turski, W.A. Binge-like Mephedrone Treatment Induces Memory Impairment Concomitant with Brain Kynurenic Acid Reduction in Mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 454, 116216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hollander, B.; Sundström, M.; Pelander, A.; Ojanperä, I.; Mervaala, E.; Korpi, E.R.; Kankuri, E. Keto Amphetamine Toxicity—Focus on the Redox Reactivity of the Cathinone Designer Drug Mephedrone. Toxicol. Sci. 2014, 141, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, I.M.; Alzahrani, A.R.; Alsaad, M.A.; Moqeem, A.L.; Hamdi, A.M.; Taher, M.M.; Watson, D.G.; Helen Grant, M. The Effect of Mephedrone on Human Neuroblastoma and Astrocytoma Cells. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Cai, R.; Chen, C.; Gao, L.; Ding, P.; Dai, L.; Chi, B. Impacts of Halogen Substitutions on Bisphenol A Compounds Interaction with Human Serum Albumin: Exploring from Spectroscopic Techniques and Computer Simulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellam, R.; Onunga, D.O.; Jaganyi, D.; Robinson, R.; Mambanda, A. Effect of the Extended π-Surface and N-Butyl Substituents of Imidazoles on Their Reactivity, Electrochemical Behaviours and Biological Interactions of Corresponding Pt(II)-CNC Carbene Complexes: Exploring DFT and Docking Interactions. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 14071–14087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Bashir, U.M.; Karney, W.L.; Swanson, M.G.; Nikolayevskiy, H. Mechanistic Analysis of 5-Hydroxy γ-Pyrones as Michael Acceptor Prodrugs. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 12432–12438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Shen, Y.; Pan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Gu, W.; Dong, J.; Yin, S.; Liu, S.; Xu, M.; Chen, B. The Hemostatic Molecular Mechanism of Sanguisorbae Radix’s Pharmacological Active Components Based on HSA: Spectroscopic Investigations, Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeski, J.; Ciesielska, A.; Makowski, M. Theoretical Study on the Alkylimino-Substituted Sulfonamides with Potential Biological Activity. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 6620–6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, G.; Salo, V.-T.; Golin Almeida, T.; Valiev, R.R.; Kurtén, T. Computational Investigation of Substituent Effects on the Alcohol + Carbonyl Channel of Peroxy Radical Self- and Cross-Reactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 1686–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, J.B.; Lee, K.; Yuan, X.; Schmidt, J.R.; Choi, K.-S. The Impact of Electron Donating and Withdrawing Groups on Electrochemical Hydrogenolysis and Hydrogenation of Carbonyl Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 15309–15319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biela, M.; Kleinová, A.; Uhliar, M.; Klein, E. Investigation of Substituent Effect on O–C Bond Dissociation Enthalpy of Methoxy Group in Meta- and Para-Substituted Anisoles. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2023, 122, 108465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezuita, A.; Makowska-Janusik, M.; Ejsmont, K.; Marczak, W. Substituent Effect in Histamine and Its Impact on Interactions with the G Protein-Coupled Human Receptor H1 Modelled by Quantum-Chemical Methods. Molecules 2025, 30, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, C.R.; Henriksen, H.C.; Wilkinson, J.R.; Schomburg, N.K.; Treacy, J.W.; Kean, K.M.; Houk, K.N.; Waters, M.L. WDR5 Binding to Histone Serotonylation Is Driven by an Edge–Face Aromatic Interaction with Unexpected Electrostatic Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 27451–27459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, G.E.; Scuseria, M.A.; Robb, J.R.; Cheeseman, G.; Scalmani, V.; Barone, G.A.; Petersson, H.; Nakatsuji, X.; et al. Gaussian 16; Revision C.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView; Version 6; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nycz, J.E.; Malecki, G.; Zawiazalec, M.; Pazdziorek, T. X-Ray Structures and Computational Studies of Several Cathinones. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 1002, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzybiński, D.; Niedziałkowski, P.; Ossowski, T.; Trynda, A.; Sikorski, A. Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of Designer Drugs: Hydrochlorides of Metaphedrone and Pentedrone. Forensic Sci. Int. 2013, 232, e28–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuś, P.; Kusz, J.; Książek, M.; Pieprzyca, E.; Rojkiewicz, M. Spectroscopic Characterization and Crystal Structures of Two Cathinone Derivatives: N-Ethyl-2-Amino-1-Phenylpropan-1-One (Ethcathinone) Hydrochloride and N-Ethyl-2-Amino-1-(4-Chlorophenyl)Propan-1-One (4-CEC) Hydrochloride. Forensic Toxicol. 2017, 35, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuś, P.; Hellwig, H.; Kusz, J.; Książek, M.; Rojkiewicz, M.; Sochanik, A. Crystal Structures and Other Properties of Ephedrone (Methcathinone) Hydrochloride, N-Acetylephedrine and N-Acetylephedrone. Forensic Toxicol. 2019, 37, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuś, P.; Rojkiewicz, M.; Kusz, J.; Książek, M.; Sochanik, A. Spectroscopic Characterization and Crystal Structures of Four Hydrochloride Cathinones: N-Ethyl-2-Amino-1-Phenylhexan-1-One (Hexen, NEH), N-Methyl-2-Amino-1-(4-Methylphenyl)-3-Methoxypropan-1-One (Mexedrone), N-Ethyl-2-Amino-1-(3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl)Pentan-1-One (Ephylone) and N-Butyl-2-Amino-1-(4-Chlorophenyl)Propan-1-One (4-Chlorobutylcathinone). Forensic Toxicol. 2019, 37, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siczek, M.; Siczek, M.; Szpot, P.; Zawadzki, M.; Wachełko, O. Crystal Structures and Spectroscopic Characterization of Four Synthetic Cathinones: 1-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2-(Dimethylamino)Propan-1-One (N-Methyl-Clephedrone, 4-CDC), 1-(1,3-Benzodioxol-5-Yl)-2-(Tert-Butylamino)Propan-1-One (tBuONE, Tertylone, MDPT), 1-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-(Pyrrolidin-1-Yl)Hexan-1-One (4F-PHP) and 2-(Ethylamino)-1-(3-Methylphenyl)Propan-1-One (3-Methyl-Ethylcathinone, 3-MEC). Crystals 2019, 9, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojkiewicz, M.; Kuś, P.; Książek, M.; Kusz, J. Crystallographic Characterization of Three Cathinone Hydro-chlorides New on the NPS Market: 1-(4-Methyl-phen-yl)-2-(Pyrrolidin-1-Yl)Hexan-1-One (4-MPHP), 4-Methyl-1-Phenyl-2-(Pyrrolidin-1-Yl)Pentan-1-One (α-PiHP) and 2-(Methyl-amino)-1-(4-Methyl-phen-yl)Pentan-1-One (4-MPD). Acta Cryst. C 2022, 78, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuś, P.; Kusz, J.; Książek, M.; Rojkiewicz, M. Crystal Structures of Two Pyrrolidin-1-Yl Derivatives of Cathinone: α-PVP and α-D2PV. Acta Cryst. C 2025, 81, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodziejczyk, W.; Jodkowski, J.; Holmes, T.M.; Hill, G.A. Conformational Analysis of Flephedrone Using Quantum Mechanical Models. J. Mol. Model. 2013, 19, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-Functional Exchange-Energy Approximation with Correct Asymptotic Behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehlich, B.; Savin, A.; Stoll, H.; Preuss, H. Results Obtained with the Correlation Energy Density Functionals of Becke and Lee, Yang and Parr. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989, 157, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T.H., Jr. Gaussian Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations. I. The Atoms Boron through Neon and Hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makieieva, N.; Kupka, T.; Spaleniak, G.; Rahmonov, O.; Marek, A.; Błażytko, A.; Stobiński, L.; Stadnytska, N.; Pentak, D.; Buczek, A.; et al. Experimental and Theoretical Characterization of Chelidonic Acid Structure. Struct. Chem. 2022, 33, 2133–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorkiewicz, P.A.; Shahamirian, M.; Kupka, T.; Makieieva, N.; Krygowski, T.M.; Szatylowicz, H. Unraveling the Push-Pull Effect in Acenes, Polyenes and Polyynes. Chem.–Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202303207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, P.M.; Olesek, K.; Woźniakiewicz, M.; Mitoraj, M.; Sagan, F.; Kościelniak, P. Cyclodextrin-Induced Acidity Modification of Substituted Cathinones Studied by Capillary Electrophoresis Supported by Density Functional Theory Calculations. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1580, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltai, T. The Ph Paradigm in Cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Raghunand, N.; Karczmar, G.S.; Bhujwalla, Z.M. MRI of the Tumor Microenvironment. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2002, 16, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M.; Tomasi, J. Geometry Optimization of Molecular Structures in Solution by the Polarizable Continuum Model. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.; Palmeira, A.; Silva, R.; Fernandes, C.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Remião, F. S-(+)-Pentedrone and R-(+)-Methylone as the Most Oxidative and Cytotoxic Enantiomers to Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y Cells: Role of MRP1 and P-Gp in Cathinones Enantioselectivity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 416, 115442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.W. Chiral Toxicology: It’s the Same Thing…Only Different. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 110, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.; Rodrigues, J.S.; Almeida, A.S.; Lima, A.R.; Fernandes, C.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Miranda, J.P.; Remião, F. Enantioselectivity of Pentedrone and Methylone on Metabolic Profiling in 2D and 3D Human Hepatocyte-like Cells. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadlej-Sosnowska, N. Substituent Active Region—A Gate for Communication of Substituent Charge with the Rest of a Molecule: Monosubstituted Benzenes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 447, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadlej-Sosnowska, N. On the Way to Physical Interpretation of Hammett Constants: How Substituent Active Space Impacts on Acidity and Electron Distribution in p-Substituted Benzoic Acid Molecules. Pol. J. Chem. 2007, 81, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Francl, M.M.; Pietro, W.J.; Hehre, W.J.; Binkley, J.S.; Gordon, M.S.; DeFrees, D.J.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XXIII. A Polarization-type Basis Set for Second-row Elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 3654–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshfeld, F.L. Bonded-Atom Fragments for Describing Molecular Charge Densities. Theoret. Chim. Acta 1977, 44, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchini, G.; Paton, R.S. Bottom-Up Atomistic Descriptions of Top-Down Macroscopic Measurements: Computational Benchmarks for Hammett Electronic Parameters. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 2024, 4, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszewski, J.; Krygowski, T.M. Definition of Aromaticity Basing on the Harmonic Oscillator Model. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972, 13, 3839–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krygowski, T.M.; Szatylowicz, H.; Stasyuk, O.A.; Dominikowska, J.; Palusiak, M. Aromaticity from the Viewpoint of Molecular Geometry: Application to Planar Systems. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6383–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.; Costa, V.M.; Gaspar, H.; Santos, S.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Carvalho, F.; Capela, J.P. Adverse Outcome Pathways Induced by 3,4-Dimethylmethcathinone and 4-Methylmethcathinone in Differentiated Human SH-SY5Y Neuronal Cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 2481–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.J.; Araújo, A.M.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Fernandes, E.; Carvalho, F.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Carvalho, M. Characterization of Hepatotoxicity Mechanisms Triggered by Designer Cathinone Drugs (β-Keto Amphetamines). Toxicol. Sci. 2016, 153, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammett, L.P. The Effect of Structure upon the Reactions of Organic Compounds. Benzene Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1937, 59, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C.; Leo, A.; Taft, R.W. A Survey of Hammett Substituent Constants and Resonance and Field Parameters. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 165–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.P.; Miranda, C.C.; Fernandes, T.G.; Gaspar, H.; Antunes, A.M.M. The Cytotoxicity of Synthetic Cathinones on Dopaminergic-Differentiated SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cell Line: Exploring the Role of β-Keto Metabolic Reduction. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 204, 115658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.P.; Ferro, R.; Pinto, D.; Silva, J.; Alves, C.; Pacheco, R.; Gaspar, H. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Effects of Chloro-Cathinones: Toxicity and Potential Neurological Impact. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorkiewicz, P.A.; Krygowski, T.M.; Szatylowicz, H. Substituent Effects and Electron Delocalization in Five-Membered N-Heterocycles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 19398–19410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorkiewicz, P.A.; Zborowski, K.K.; Krygowski, T.M.; Szatylowicz, H. Substituent Effect versus Aromaticity—A Curious Case of Fulvene Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 14775–14780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieczorkiewicz, P.A.; Szatylowicz, H.; Krygowski, T.M. Mutual Relations between Substituent Effect, Hydrogen Bonding, and Aromaticity in Adenine-Uracil and Adenine-Adenine Base Pairs. Molecules 2020, 25, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.