Abstract

In the field of port security, traditional human–vehicle interaction conflict (HVIC) alarm algorithms predominantly rely on the bounding box overlap ratio. This criterion often fails in complex industrial environments, leading to excessive false positives caused by stationary vehicles, perspective distortion, and boarding/alighting activities. To address this limitation, this study proposes a dual-stage intelligent agent architecture designed to minimize false alarms. The system integrates YOLOv8 as a front-end lightweight detector for real-time candidate screening and Qwen2.5-VL, a domain-adaptive multimodal large model, as the back-end semantic verifier. A comprehensive dataset comprising one million port-specific images and videos was curated to support a novel two-phase training strategy: image pretraining for object recognition followed by video fine-tuning for temporal logic understanding. The agent dynamically interprets alarm events within their spatiotemporal context. Field trials at an operational wharf demonstrate that the proposed agent achieves an alarm precision of 95.7% and reduces false positives by over 50% across major error categories. This approach offers a highly reliable, automated solution for industrial security monitoring.

1. Introduction

Ports play an important role in the global supply chain, facilitating cargo handling, warehousing, and logistics distribution. Consequently, ensuring port security is of utmost significance [1,2]. The coexistence of personnel and heavy machinery in port production introduces substantial hazards, with conflicts between humans and vehicles (human–vehicle interaction conflict, HVIC) constituting a primary factor contributing to accidents. Traditional manual safety supervision faces challenges due to the complexity and constant changes in operational conditions. For example, delays in detecting violations can extend to two to three hours at Tianjin Port [3]. Driven by global economic integration and port digitalization, the ports and shipping industries are undergoing significant transformations. Since 2018, the intelligent shipping industry has been expanding at a compound annual growth rate of 14.2% [4] and deep learning technology has been widely applied to fault diagnosis in port environments [5]. Consequently, it is urgent to establish an automated intelligent monitoring system that can accurately identify security events and provide continuous, high-precision monitoring to enhance security and operational efficiency.

Conventional video surveillance systems utilized in port environments are hindered by limitations in data transmission, storage, and computational capabilities [6]. The development of artificial intelligence and interconnected systems makes security assurance a key component in the field of intelligent ports [7]. Mes and Douma of the University of Twente, the Netherlands, proposed to combine predictive outputs with prescriptive analytics for data-driven decision making for predictive maintenance and data-supported operations of port equipment and facilities [8]. The introduction of routine unmanned aerial vehicle inspection has greatly improved port security monitoring and emergency response capabilities. The use of a digital logistics platform has also brought unprecedented convenience and efficiency to port operations. Ibrahim presented an innovative process for accelerating the development of marine port security based on a neurotechnology remote-controlled prototype robotic cell, utilizing the robotic cell to explore imminent security events [9]. Busan Port in South Korea has adopted advanced automation equipment and intelligent control system to realize automation of cargo loading, unloading, and transportation. The real-time integration of Internet of things and big data technology can monitor equipment operation and cargo status, and improve operation efficiency and safety. An artificial-intelligence-based governance model was proposed to build a trust-based logistics supply chain, thus advancing the research on container ports [10]. The port of Rio de Janeiro has improved port security by using an extended integrated security system to monitor internal warehouses, cargo, and terminal areas. The system enhances the management of vessel berthing operations and offers technical solutions to support customs procedures [11]. It is apparent that the integration of intelligent technologies within port environments contributes to the advancement of safety and security outcomes [12].

Current algorithms for security alarms that utilize computer vision primarily depend on object detection methodologies, such as those represented by the YOLO (You Only Look Once) framework [13,14,15]. These technologies are used to identify safety signs [16], determine whether individuals are wearing helmets [17,18], etc. These methods focus on identifying objects rather than understanding specific events, so when the event definition is complex, the false positive rate is high [14]. Taking the HVIC alarm as an example, alarms are triggered whenever the bounding boxes of people and vehicles detected by object detection algorithm overlap [19,20]. Such a criterion frequently yields false positives. Objects may appear to overlap in the image plane while remaining at a safe distance in three-dimensional space. Furthermore, the vehicle may be stationary, so it does not pose a threat to nearby pedestrians. Besides, the detector may misclassify targets.

Therefore, efforts are being made to improve traditional object detection models, such as reducing background distractions using image segmentation algorithms [21], processing surveillance videos frame-by-frame continuously using deep learning methods [22], or utilizing motion detection by frame subtraction to record scenes involving people or vehicular activity [23]. Recently, these efforts have indeed led to some breakthroughs. For example, using YOLOv8-Background Subtraction (YOLOv8-BS), the classification of four key behaviors in free-roaming cattle has improved accuracy by 20% [24]. Using the YOLOv4 deep learning model and processing in the ConvLSTM model, a variety of unsafe behaviors are identified by detecting the frames containing the targets related to unsafe behaviors in the real-time monitoring video of industrial plants [25].

Despite advances in vision-based port security monitoring, high false alarm rates remain a core scientific challenge hindering practical deployment. Most existing systems rely on shallow, static analysis of bounding box geometries like overlap metrics. Such approaches fail to comprehend the complex dynamic semantic interactions and spatiotemporal context between people, vehicles, and their environment, leading to misclassification of numerous spatially proximate yet inherently safe scenarios as hazardous. Recent improvements have only mitigated single-type false alarms without fundamentally endowing systems with deep semantic understanding of event intent and risk levels. This semantic gap between perception and cognition represents the critical divide between current technological capabilities and the realization of reliable, usable intelligent port security.

The innovation of a multimodal large-scale model provides a new method to deal with the challenges related to port security alarm system. In 2017, Google introduced the Transformer architecture, a neural network based on self-attention mechanisms that significantly advanced the field of natural language processing (NLP) and established a foundation for a large-scale pretraining model [26]. Building on this framework, OpenAI and Google launched GPT-1 and BERT in 2018 [27,28], thereby solidifying the dominance of pretrained large models in NLP. In March 2023, OpenAI released GPT-4, which is a large-scale multimodal pretraining model, demonstrating the ability of multimodal understanding and heterogeneous content generation. By integrating language and visual models, GPT-4 extends textual comprehension and thinking chain reasoning to the visual field, promoting image understanding and generation [29]. This development marks a critical transition from vision–language fusion to the integration of three or more modalities, providing a robust basis for future multimodal information processing. By 2025, DeepSeek had released the multimodal large model DeepSeek-VL2 [30] and the large language model DeepSeek-R1 [31], signing a new stage in large model technology. Additionally, Alibaba’s Qwen2.5-VL series further enhances multimodal capabilities, enabling the analysis of long-form videos [32]. Currently, multimodal large models are extensively utilized in various domains, including healthcare [27,28], finance [33,34], and climate science [35,36], demonstrating significant potential and value. In the foreseeable future, multimodal large-scale models will play an important role in the field of port security.

Motivated by the limitations of previous research and the advancements in large model technology, this study proposes a domain-adaptive multimodal foundation model designed for an intelligent agent focused on port security. The proposed architecture integrates a lightweight object detector with a large vision language model (LVLM) to facilitate staged verification, seamlessly integrating with the port security alarm system. Real-time processing of monitor video streams is achieved through a YOLO model, which ensures high recall and efficiency in capturing all potential HVIC events. When an alarm is triggered by the YOLO model, the relevant video segment is automatically uploaded to a server, where a fine-tuned LVLM of the port scene conducts a subsequent evaluation of the incident. Upon confirmation of the alarm, it is relayed to the security platform, prompting an alert.

The key contributions of this paper are as follows.

- An architecture that specifically targets and resolves main identified classes of false alarms (stationary vehicles, perspective distortion, etc.) through multimodal reasoning is presented, which combines the computational efficiency of a lightweight detector with the deep contextual understanding provided by a large vision model.

- A comprehensive, large-scale dataset comprising nearly one million port-specific images and video clips has been curated, serving as a valuable resource for future research.

- An innovative image pretraining and video fine-tuning strategy specifically designed for port-domain data has been developed, resulting in significant enhancements in model comprehension and discriminative accuracy.

- The proposed intelligent agent has been thoroughly deployed in an operational port environment, leading to a substantial increase in alarm accuracy and reducing false alarms across major error categories by over 50%, offering a robust solution for automated industrial surveillance.

2. Related Work

In this section, the methods and research involved in this study will be summarized.

2.1. YOLOv8

In recent years, object detection has witnessed significant advancements with the development of deep learning models. Among these, the YOLO series stands out for its real-time performance and high accuracy. YOLOv8, the 2023 edition of the series, is presently the most widely utilized version, as it builds upon the strengths of its predecessors while introducing several novel improvements to enhance detection capabilities [37].

YOLOv8 retains the core philosophy of YOLO models, which is to perform object detection in a single forward pass through the network, thus achieving high speed and efficiency. However, unlike earlier versions, YOLOv8 incorporates several architectural modifications and training strategies to improve accuracy and robustness. One notable change is the adoption of a more advanced backbone network, which enhances feature extraction capabilities. Additionally, YOLOv8 introduces an improved neck structure for better multiscale feature fusion, enabling the model to detect objects of varying sizes more effectively.

Furthermore, YOLOv8 leverages advanced training techniques such as data augmentation and loss function optimization to further boost performance. These enhancements collectively contribute to the superior detection accuracy and speed of YOLOv8 compared to its predecessors. Due to its superior performance, YOLOv8 has been extensively employed in agriculture [38,39], electricity [40], and the industrial sectors [41,42].

2.2. Qwen2.5-VL

Qwen2.5-VL, the latest vision language model released by Alibaba’s Qwen team, represents the third generation of the open-source Qwen-VL series and is available in 3B, 7B, 32B, and 72B parameter variants. This model is specifically designed for synergistic reasoning between vision and language, incorporating dynamic resolution processing, absolute temporal encoding for video content, and advanced vision–language fusion mechanisms, thereby achieving significant advancements in multimodal artificial intelligent agent. Compared with previous generation products, Qwen2.5-VL natively processes images with arbitrary resolution and videos that extend for several hours without rescaling or padding. Spatial understanding is facilitated through a window attention mechanism coupled with two-dimensional rotary position embeddings (2-D RoPE). Absolute temporal encoding enables precise event localization within videos, while a dual-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) aligns visual and textual features to support cross-modal reasoning.

Qwen2.5-VL shows excellent performance in various practical applications. As an autonomous visual agent, it can navigate user interfaces, fill in forms, and execute multistep workflow according to text instructions. The model has achieved the most advanced results in many fields, including document parsing for extracting structured data from invoices, spatial reasoning tasks such as object positioning using bounding boxes, and long video understanding for applications such as lecture abstracts and motion analysis. Designed for deployment across edge devices to cloud servers, Qwen2.5-VL outperforms competitive models including GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet on specialized tasks such as multilingual optical character recognition (OCR) and chart interpretation.

2.3. Research on Unsafe Behavior

In recent years, research on the detection and prevention of unsafe behavior has made significant progress in several fields. Khosravi et al. systematically reviewed the influencing factors of unsafe behavior on construction sites, laying a theoretical foundation for subsequent research [43]. In terms of detection methods, target detection algorithms are mainly used. For example, an efficient detection model was developed for industrial sites [44] and water conservancy projects [45] based on the YOLO framework. Deep learning technology has also further demonstrated its strong advantages, and the improved deep learning framework outperformed traditional algorithms in the detection of unsafe behaviors of seafarers [46]. For behavioral analysis, Meng et al. systematically ranked construction workers’ unsafe behaviors through a complex network approach [47], while Yu et al. experimentally verified the feasibility of real-time recognition methods based on image skeletons [48]. Scene-specific research has also achieved important results.

Studies in the field of port safety are relatively few and focus on the analysis and prevention of factors influencing unsafe behavior. For instance, one study explored the impact of safety leadership on worker behavior in container terminals [49]. Xu and Wang proposed a framework for reducing unsafe behaviors of crew members through timely reminders [50]. Moreover, Wukak et al. found that good knowledge and supervision are effective in reducing unsafe behaviors of stevedores [51], and the relationship between crew motivational factors and unsafe behaviors was revealed [52]. In addition, data analysis showed that the most prominent safety risk in port operations is not wearing protective equipment [53]. These studies have provided theoretical support and technical solutions for the identification and prevention of unsafe behaviors in different scenarios. Considering the complex environment of ports and the inclusion of many domain-specific identification targets, there are relatively few existing studies on the identification of unsafe behaviors of dock personnel, which is also a critical measure for improving dock security.

Recently, multimodal large vision language models have opened new research directions for intelligent safety monitoring across industrial environments. Unlike traditional vision algorithms, multimodal large models integrate high-level semantic reasoning with fine-grained visual perception, enabling a deeper understanding of complex human behaviors and operational contexts. Early progress has demonstrated their potential. Kim et al. leveraged large model-based reasoning to automatically assess construction hazards, showing that large models can capture implicit risk cues beyond explicit object detection [54]. In human robot collaborative environments, Spurny et al. incorporated multimodal representations to model dynamic proxemics, allowing robots to interpret human intentions and prevent unsafe distancing events [55]. Meanwhile, Abdullah et al. introduced ISafetyBench, a multimodal model benchmark tailored for industrial safety monitoring tasks, highlighting the importance of temporal reasoning, causal understanding, and multistep inference in real-world safety scenarios [56].

Beyond application-level studies, research on efficient multimodal large model architectures also advances rapidly. Yao et al. proposed a computationally optimized multimodal framework that maintains strong semantic reasoning capabilities while significantly reducing inference overhead [57]. Their work illustrates a critical trend that multimodal large model can be adapted for deployment in latency-sensitive or resource-constrained industrial settings, provided that architectural and training strategies are carefully designed. Together, these studies illustrate a growing consensus in the community that future industrial safety systems must integrate perception, context understanding, and reasoning within a unified multimodal framework.

However, existing multimodal systems generally follow two trajectories. On the one hand, general multimodal models exhibit strong zero-shot scene understanding but suffer from limited real-time performance and insufficient domain specificity. On the other hand, lightweight deep learning models are ideal for specific environments such as factories or construction sites, which achieve high efficiency, but lack the genuine ability to comprehend events, making it difficult to handle complex issues. This study is positioned between these two paradigms. By combining domain-specific pretraining with task-oriented fine-tuning, Qwen2.5-VL is applied with strong port-specific semantic comprehension, while a lightweight front-end detection module ensures the overall real-time responsiveness of the system. This two-stage framework provides a novel and practical solution for deploying advanced reasoning capabilities in resource-constrained port environments.

3. Methodology

This section provides a detailed exposition of the research question definition, the design of the intelligent agent framework, the construction of a million-entry professional dataset developed for this study, and the specialized training strategy proposed for the intelligent agent.

3.1. Definitions

In port operations, HVIC events refer to scenarios where operating personnel enter hazardous proximity to mobile equipment such as trucks or forklifts, creating significant safety risks. For surveillance video analysis, the operational discrimination criteria are formally defined as

- 1.

- The distance between the centroid of the pedestrian bounding box and the nearest edge of the vehicle bounding box must be less than one-third of the sum of the pedestrian bounding box width and height.

- 2.

- The width of the pedestrian’s bounding box should not exceed two-thirds of the vehicle’s width, while the height of the pedestrian must be greater than 0.2 times the height of the vehicle.

The port industry relies on internationally recognized safety frameworks to characterize and control HVIC risk, particularly in scenarios where personnel work in close proximity to moving forklifts or trucks. The ILO Code of Practice: Safety and Health in Ports [58] is globally regarded as the primary normative reference for port safety and requires ports to maintain clearly identifiable and enforceable human vehicle separation, define mandatory vehicle speed limits, establish minimum risk interaction zones, and implement visual warning zones and blind-spot compensation technologies. Yet, because port operations, equipment types, and regulatory contexts vary widely, the ILO code intentionally avoids prescribing a universal minimum separation distance.

More quantitative risk-metric definitions are provided by machinery safety standards such as ISO 13855:2024, which offers a formal method for calculating the required minimum safety distance between humans and moving machinery [59]. The standard defines the distance as

where S is the minimum safety distance (mm), K is the human approach speed, T is the overall system stopping time, is a device-dependent additional distance, and Z is an application-specific compensation factor. This method has been widely applied in manufacturing, warehouse automation, and mobile-equipment safety assessment [55,60], demonstrating its relevance for port scenarios.

For vehicle dynamics, ISO 3691-1 [61], which specifies safety requirements for industrial trucks, further mandates adequate braking performance and speed control in pedestrian-mixed environments. The braking distance of a forklift traveling at velocity v can be modeled as

where is the combined reaction time of the operator and braking system and a is the effective deceleration during braking. This formulation links vehicle dynamics to the stopping-time parameter T in ISO 13855 [59]. Industry practice commonly limits vehicle speed to no more than 6 km/h in pedestrian zones.

However, because monocular surveillance images cannot yield absolute distance estimates, operational HVIC detection often relies on coarse visual-proximity surrogates. As a result, traditional YOLO-style detection systems typically activate alarms based on bounding-box overlap or heuristic image-space distance thresholds.

The monitor video analyzed in real time by the input alarm algorithm can be conceptualized as a sequence of continuous frames:

where T is the total number of frames, H and W represent the height and width of each frame, respectively, and denotes the RGB image at time step t.

The alarm algorithm processes each frame and outputs a binary trigger signal:

The trigger condition is activated when the bounding boxes of persons and vehicles overlap in the same frame. Formally, let be the set of all detected objects in frame , with representing persons and representing vehicles. The trigger function is defined as:

where denotes the Intersection over Union metric measuring bounding box overlap:

This condition triggers an alarm () when any vehicle bounding box overlaps with any personnel bounding box, indicating potential risk in surveillance scenarios.

However, this simplified evaluation criteria leads to a high incidence of false positives in operational settings. As mentioned earlier, simple bounding box overlap detection is insufficient to define the complex issue of HVIC. This limitation hinders the effective application of alarm algorithms. The primary objective of this study is to effectively reduce false alarms by developing an alarm architecture that enables a thorough understanding of HVIC through video monitoring.

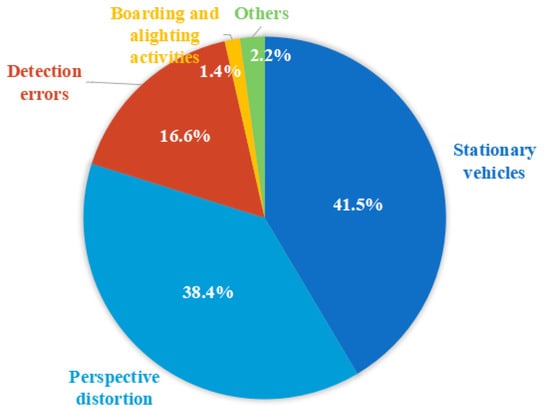

After analyzing the real port alarm logs recorded from the security platform, the following four main types of false alarms are found, with the respective percentages shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

The categorization of false alarm types as documented in the logs generated by security platforms.

- 1.

- Stationary vehicles: YOLO’s single-frame processing cannot discern vehicle motion status, generating alarms when a person approaches parked vehicles posing no immediate threat, as shown in Figure 2a.

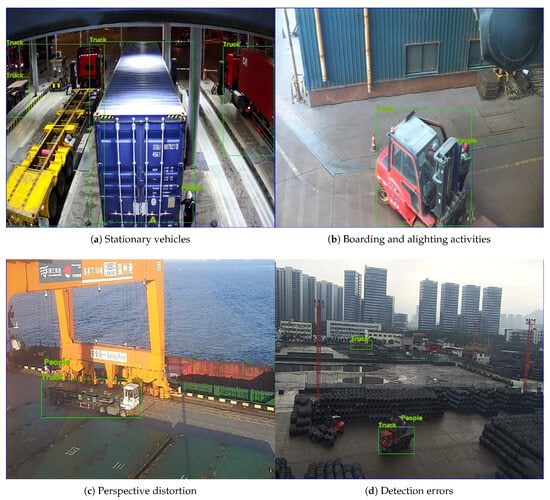

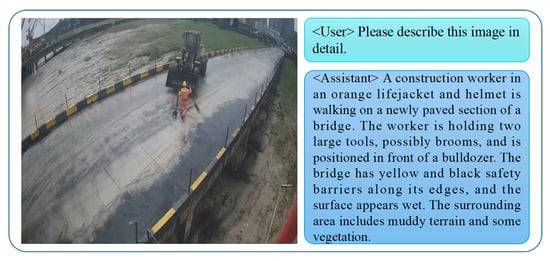

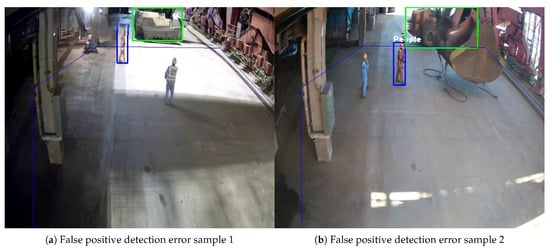

Figure 2. Sample video frames of diverse false alarm categories recorded by the security platform, including vehicle and personnel detection frames and the corresponding labels of YOLOv8, where the blue box represents personnel and the green box represents trucks.

Figure 2. Sample video frames of diverse false alarm categories recorded by the security platform, including vehicle and personnel detection frames and the corresponding labels of YOLOv8, where the blue box represents personnel and the green box represents trucks. - 2.

- Boarding and alighting activities: Unlike stationary vehicle cases, these instances involve drivers remaining within their vehicles while ground personnel interact with the vehicles (e.g., retrieving items or engaging in conversation). Figure 2b shows a scene in which the personnel exits a car.

- 3.

- Perspective distortion: Despite sufficient 3D spatial spacing, the camera’s perspective may result in misleading overlapping 2D bounding boxes. The pedestrian and vehicles in Figure 2c not occupying the same lane and are, in fact, separated by a safe distance. However, the overlap of detection frames is a result of the camera’s perspective.

- 4.

- Detection errors: Instances of misclassifications may occur, such as nonhuman objects being incorrectly identified as individuals or containers being incorrectly labeled as vehicles. As shown in Figure 2d, the detection box labeled PEOPLE is actually part of a forklift.

It can be seen that the aforementioned false alarms ultimately stem from the alarm algorithm’s inability to comprehend the meaning of HVICs. Methods such as the improved YOLO algorithm based on motion analysis components utilizing background modeling have demonstrated significant effectiveness in reducing false alarms for specific categories like stationary vehicles. However, the persistent triggering of alerts for other categories indicates that traditional object detection systems inherently lack the capability to perceive dynamic events and understand context, which are both essential for reliably issuing HVIC alerts. To address this, this study introduces intelligent agents based on multimodal large models to replace conventional object detection and alert algorithms.

3.2. Intelligent Agent Framework

The port security intelligent agent is designed with a dual-stage processing pipeline. The first stage involves an initial screening phase that employs object detection techniques, enabling the intelligent agent to have perceptual ability. The second stage utilizes a domain-adapted multimodal vision model for understanding and verifying events. Upon confirmation of potential threats, the system immediately generates alerts for the security platform and simultaneously uploads annotated visual evidence for operator evaluation and reduction of false alarms. Therefore, intelligent agents possess both perceptual and cognitive functions.

3.2.1. Object Perception

The initial object perception is achieved by a YOLOv8-based detector, which processes video streams at millisecond intervals. This stage is responsible for the preliminary identification of potential HVIC events through the analysis of the proximity of the bounding box. When identified risks meet specific geometric criteria, the system captures 24 s video segments (12 s prior to the trigger and 12 s subsequent) for transmission to the server via FTP.

The selected algorithm for target detection is YOLOv8, which utilizes a specific loss function of

where:

- : the predicted bounding box.

- : the actual bounding box.

- : intersection over union.

- : the Euclidean distance between the center of the predicted bounding box and actual bounding box.

- : the diagonal length of the minimum enclosing frame.

- : the aspect ratio congruence, where and are the width and height of the predicted bounding box and and are the width and height of the actual bounding box, respectively.

- .

For input video stream , target detection is performed for each frame :

where is the bounding box coordinates, are the category labels, and is the confidence level.

When the object detection algorithm detects HVIC events, it triggers an alarm and extracts video clips related to the alarm:

where:

- : personnel-to-vehicle bounding box intersection and ratio.

- : confidence of YOLO model predictions for the category people.

- : confidence of YOLO model for all vehicle classes.

- : threshold.

- : state of vehicle motion (0 = stationary, 1 = motion).

- : time when HVIC event is detected.

3.2.2. Event Cognition

The event cognition is conducted by a Qwen2.5-VL model, which operates on a Flask backend and completes its evaluation within three seconds. Through domain-adaptive fine-tuning, the model learns the definition of HVIC alarm events and assesses three critical aspects: the accuracy of pedestrian identification, the motion state of nearby vehicles, and the interpretation of scene context. This comprehensive evaluation culminates in a final alarm determination that is informed by enhanced contextual understanding.

Qwen2.5-VL model for multimodal feature extraction of saved video clips:

where:

- : multimodal feature matrix with dimension .

- : Qwen2.5-VL feature encoder function.

- : input video clip with tensor dimension .

- : vision Transformer function.

- : vision projection matrix with dimension .

- : text prompt word string.

- : text encoder function.

- : text projection matrix with dimension .

- : bias term vector with dimension .

- LayerNorm: layer normalization function.

The final determination of whether or not to alarm is

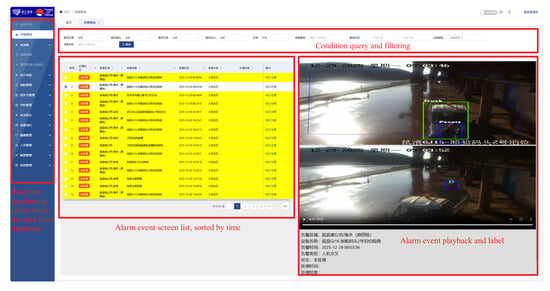

3.2.3. Platform Integration

Subsequent to the verification outcomes, the security platform executes two principal operations simultaneously: it generates real-time alerts on site, which are displayed on a dashboard interface, and facilitates the automated archiving of annotated video sequences, which include key frames. Furthermore, the system provides additional human-in-the-loop features, which consist of alarm state management (either pending or processed), video playback with temporal navigation controls, image examination with zoom and pan functionalities, as well as automated diagnostics for camera hardware, as illustrated in Figure 3. In the figure, the left side lists the functions of the security platform, including real-time monitoring, alarm event statistics, and playback, etc. At the top is the alarm event filtering function, which can be searched by camera location, time, and alarm event type. The middle list is an alarm event sorted by time, with those that have not been processed highlighted. Select any event and click to expand to see the rightmost interface, which includes alarm event fragment follow-up and keyframes, as well as specific information such as occurrence time, event type, and processing results.

Figure 3.

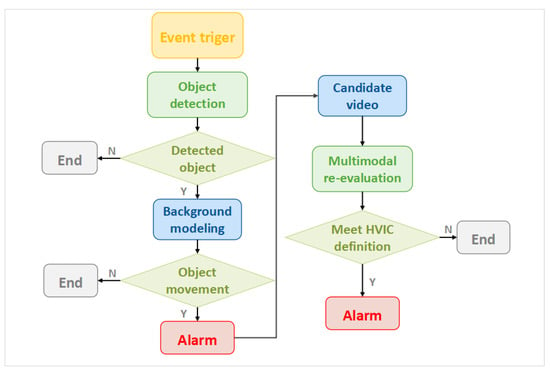

Display of the interactive interface for the port intelligent security platform.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the overall workflow integrates monitoring for event triggers, object detection and recognition, background modeling and analysis, candidate video dispatch, the return of secondary judgment results, and closed-loop alarm management. Since both YOLO’s object detection and post request submission are performed in real time, the complete processing cycle, excluding network transmission variability, can be consistently completed within 5 s. Compared with traditional 24 h manual monitoring systems, this dual-stage agent has the ability of object perception and event cognition, greatly reducing false alarms and completing the automated closed-loop process of HVIC risk identification, alarm recognition, and archiving, while greatly reducing labor costs and ensuring port security.

Figure 4.

The architecture and operational workflow of the security intelligent agent proposed in this paper.

3.3. Dataset

A dedicated port security dataset comprising nearly one million images and video samples is curated to support large-scale model training. The data collection process is focused on the Ningbo Zhoushan Port and its affiliated terminals, employing three main methods of data acquisition: systematic frame extraction from ongoing surveillance footage, retrieval of historical alarm images from security platform servers, and direct collection of related alarm video recordings. The resulting dataset thoroughly encompasses essential operational areas, including container yards, berths, approach bridges, and gate lanes, while also highlighting port-specific assets such as containers, quay cranes, and cargo vessels. The comprehensive statistics regarding data sources, volume, and scene distribution are detailed in Table 1, which provides a quantitative image and video counts from primary and auxiliary terminals, along with the proportion of eight key operational scenes. For example, the proportion of Unloading Area image is 24.3%. This structured presentation ensures transparency and facilitates the assessment of data representativeness.

Table 1.

Detailed statistics and composition of the dataset.

This study employs dual annotation methodologies for images collected, encompassing both object labeling and textual description. In the context of object detection, images are annotated across eleven distinct categories, which include people, safety helmet, reflective vest, truck, forklift, car, bus, and four additional classifications, to support the training of the object detection algorithm. To enhance the semantic context for vision–language models, each image is accompanied by natural language descriptions that explain potential security incidents, such as HVIC events and various scenarios of noncompliance with safety helmet regulations. The detailed specifications for the generation of these textual descriptions are provided in Table 2. This table formalizes the annotation requirements across seven key dimensions, including dynamic behaviors, spatial relationships, and environmental context, thereby ensuring consistency, richness, and reproducibility in the supervisory signals provided to the vision–language model. An illustrative example of text description labeling is presented in Figure 5.

Table 2.

Port security image caption annotation specification.

Figure 5.

An image text description label example.

The videos in dataset are processed as substreams at 360 × 420 resolution, with individual clip spanning 12 to 30 s in industrial settings. Beyond binary positive or negative sample labeling, negative samples undergo subclassification according to established false positive taxonomy. Representative subcategories include personnel misidentification cases and nonhazardous proximity scenarios requiring no alarm activation, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Prompt and output labeling of multimodal large model training videos for security event determination.

3.4. Training Strategy

In order to fully leverage the advantages of the proposed intelligent agent structure, two-stage domain adaptation strategy is proposed using the established port industry specific dataset. The object detection algorithm still uses images labeled with port target categories and detection boxes for training. For multimodal large models, the first stage involves pretraining on scene objects using images specific to port operations, including container trucks, quay cranes, and yard equipment, using image–text pairs for supervised fine-tuning and focusing on the static characteristics of scenes involving individuals, vehicles, and machinery. This pretraining stage is similar to the training of object detection algorithms, which can use the same image with text description, but the training output text description more comprehensively summarizes the information in the image. This process can enhance the visual characteristics of the port target and improve the behavior recognition ability of the large model. The second stage entails fine-tuning based on event dynamics, utilizing a dataset of annotated video clips that illustrate temporal patterns of HVIC events. These clips include labels for four false positive categories (stationary vehicles, personnel or vehicle detection errors, perspective distortion, and boarding and alighting activities) alongside authentic HVIC events. This comprehensive strategy enhances the model’s capacity to discern vehicle movement and human intent.

4. Experiments and Results

In this section, a comprehensive description of the experiments will be provided, including experimental setup, such as training parameters, evaluation metrics, and experimental results.

4.1. Experimental Setup

In this study, the training parameters for both the object detection algorithm and the multimodal model are selected by empirical and grid search methods.

The YOLOv8 object detector is trained on 50,000 professionally annotated port images, partitioned into a training set of 45,000 images and a validation and test set of 5000 images using a 9:1 ratio. A total of 300 epochs are conducted, resulting in an overall training duration of 42.4 h utilizing a single A100 GPU(manufactured by NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with a memory consumption of 40,536 MB. The inference speed for a single graph is recorded at 1.8 ms. The performance metrics of the trained YOLOv8 model on the validation dataset are presented in Table 4. Notably, the model achieves an overall precision rate of 0.893 and a recall rate of 0.855 across eleven classifications, with the accuracy for each individual classification exceeding 0.85.

Table 4.

Performance metrics of the YOLOv8 model on validation set.

In order to effectively filter false alarms due to vehicle stationary, the visual background extraction algorithm (VIBE) is combined with YOLOv8 to extract motion foreground pixels, and the motion characteristics of the target detection frame are filtered. The foreground pixels extracted by VIBE that account for more than 0.25 of the target detection frames are counted as motion targets.

This paper selects the Qwen2.5VL-7B-Instruct model for re-evaluation in the intelligent agent. Pretraining and fine-tuning execute on a six-core NVIDIA RTX 4090(manufactured by NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) cluster using Python 3.10 and PyTorch 2.1.2. In the two-stage training process, domain-adaptive image pretraining is first executed. Based on the constructed port security image–text pair dataset, the Qwen2.5-VL-7B-Instruct model undergoes domain-adaptive continued pretraining. This stage employs a causal language modeling objective, aiming to align the model’s general visual-linguistic knowledge with the specialized domain of port operations and security protocols. Training hyperparameters are set as follows: global batch size of 96, learning rate of 2 × 10−5, AdamW optimizer (, ) with cosine annealing scheduler, weight decay of 0.1, and 50 training epochs until validation loss stabilized.

The subsequent supervised fine-tuning phase focuses on refining the model’s ability to recognize HVIC events while distinguishing them from various false alarms. To achieve this, a balanced fine-tuning dataset is constructed, comprising 5000 positive samples and 5000 negative samples. To ensure the model effectively identifies and reduces the four primary false alarm categories outlined earlier, negative samples are collected using a stratified sampling strategy, guaranteeing sufficient representation of each false alarm type in the training data. Fine-tuning employs the efficient low-rank adaptation parameter adjustment method, setting the rank to 64 and the scaling factor to 16. This is applied to the query and value projection matrices within the vision and language transformer layers. Training hyperparameters includes a global batch size of 20 achieved through a per-device batch size of 5 combined with 4-step gradient accumulation, a learning rate of , AdamW optimizer, 100 training epochs, and early stopping based on validation set accuracy to select the optimal checkpoint.

To guide the model toward targeted reasoning, a single structured prompt template is designed and used across all training and evaluation data, as shown in Table 3. This unified prompt explicitly defines the output format and establishes the task around the core semantic criteria necessary for judgment. Crucially, by directing the model’s attention to these fundamental criteria through instruction rather than employing separate rules or prompts for each false alarm category, the design leverages and demonstrates the model’s strong general reasoning capability. The model learns to apply a consistent reasoning process to diverse scenarios based on an integrated understanding of context, motion, and intent. Ultimately, the quantized model is deployed via Flask service, achieving video re-evaluation within 3 s on a single RTX 4090 GPU (manufactured by NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

As the task constitutes binary alarm determination, evaluation employs accuracy for overall correctness, recall for true alarm detection rate, and false positive rate for misclassified negative instances. It should be noted that the recall calculation in this study is based on HVIC events detected by the improved YOLOv8 triggers. Due to the high manpower requirements for handling 24 h real-time monitoring with multiple cameras, it is challenging to statistically analyze all real HVIC events that occur in the monitoring environment. While this study has set a conservatively low detection threshold of YOLOv8 to minimize missed events, this evaluation approach may not account for incidents that go entirely undetected by the system. Future work will address this limitation through more extensive manual annotation of surveillance footage to establish a more complete ground truth dataset.

where:

- TP = True Positives

- TN = True Negatives

- FP = False Positives

- FN = False Negatives

4.3. Results and Discussion

The proposed intelligent agent system has been implemented within the surveillance network of Shulanghu Wharf in Zhoushan for the purpose of operational validation. As a key processing center for iron ore, Shulanghu Wharf is responsible for various activities, including the unloading, dispatching, and storage of bulk materials. The intricate operational environment, characterized by frequent interactions between personnel and vehicles, necessitates rigorous performance standards for intelligent security systems.

In order to comprehensively demonstrate the practical effectiveness of the proposed intelligent agent and training strategy, field trials are conducted at the port. Then, data obtained from the Shulanghu Wharf intelligent security platform are analyzed to further prove the robustness of the proposed intelligent agent. Finally, the ablation study is conducted.

4.3.1. Port Field Trial

The field trial of the port, i.e., the operational validation conducted as the port safety alarm system acceptance test, comprised 23 safety-related activities. Among these, 10 are events characterized by the vehicle remaining stationary or individuals entering and exiting the vehicle. The remaining 13 operations involve complex scenarios where people and machines interacted. These activities are selected in coordination with terminal safety personnel to ensure they are representative of real hazardous interactions, can be performed without interfering with normal operations, and encompasses all relevant, recordable scenarios within the test zone during the evaluation period. This approach validates the system’s performance under authentic working conditions. Figure 6 illustrates the field trial environment and two samples of an HVIC event. The test results of different alarm algorithms are shown in Table 5.

Figure 6.

Samples (a,b) of a positive HVIC alarm in the field trial of the port, where the blue box represents personnel, the green box represents trucks, the purple box represents the forklift and the red box represents the container.

Table 5.

Alarm results of different methods in the field trial of port.

The test results indicate that the intelligent agent system records one missed alarm, while the target detection algorithm exhibits two false alarms following enhancements. In contrast, the YOLOv8 algorithm before improvement demonstrates a higher incidence of false alarms and lower accuracy. A detailed description of each instance in the field trial is presented in Table 6. Due to field trial conditions, the examination of false alarms is limited to stationary vehicles and boarding and alighting activities. Specifically, the accuracy of YOLOv8 algorithm is 56.5%, the recall rate is 100%, and the false alarm rate is 100%. After improvements, the YOLOv8 algorithm’s accuracy increases to 91.3%, maintaining a recall rate of 100% while reducing the false alarm rate to 20%. The intelligent agent system demonstrates an accuracy of 95.7%, a recall rate of 92.3%, and a complete absence of false alarms.

Table 6.

Instance descriptions and correct judgment counts of different methods in field trials.

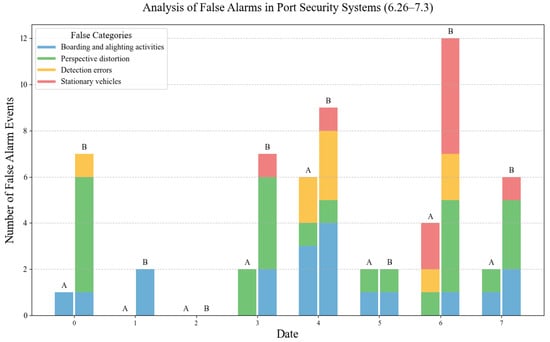

4.3.2. Security Platform Data Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate system efficacy and robustness in production settings, alarm records from the intelligent security platform spanning from 26 June to 3 July 2025 are analyzed. This eight-day evaluation period encompasses diverse operational shifts and terminal scenarios, providing realistic insights into system performance during actual operations.

Alarm statistics from both improved object detection and the intelligent agent system are presented in Table 7. Because the security platform archive only retains the triggered alarm video data, and it is very difficult to directly obtain and count HVIC events from the whole day monitoring video, the precision and recall metrics of the original YOLOv8 algorithm cannot be directly assessed. Consequently, subsequent quantitative analysis of platforms results relies on detected alarm instances.

Table 7.

Alarm results for improved YOLOv8 and intelligent agent recorded on the security platform during the period platform spanning from 26 June to 3 July 2025.

It is worth emphasizing that a real port production environment is more severe than a port field trial, and long-term production faces more influencing factors. Therefore, the performance of all alarm systems has decreased. Among the 56 alarms triggered by the improved object detection algorithm, only 11 are true alarms, with the remaining 45 being false positives. The algorithm achieves a recall rate of 100% (based on the analysis of existing data); it appears to detect all alarms. However, the high false positive rate renders the surveillance platform’s alarms unusable without further verification. The large number of false positives requires significant labor resources to filter out, not only increasing costs but also potentially desensitizing surveillance personnel to alarm information, reducing their response efficiency to true alarms.

In stark contrast, the intelligent agent system proposed in this paper effectively reduces the false positive rate by understanding and re-evaluating events. The intelligent agent system achieves an accuracy of 66.1%, a recall rate of 81.8%, and a false positive rate of 37.8%. Considering the extremely harsh deployment environment at the port, this result has tripled the accuracy compared to the baseline of 19.6%, which is sufficient to demonstrate the robustness of the proposed agent.

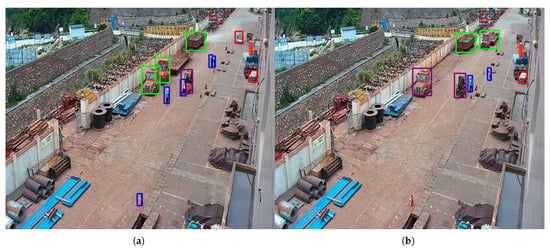

Figure 7 shows a comparison of the different types of false alarms between the two methods over eight days. It can be seen that, in most cases, the intelligent agent with multimodal large model re-evaluation significantly reduces false alarms by half compared to YOLOv8, and effectively reduces four types of false alarms, particularly in terms of stationary vehicles and perspective distortion.

Figure 7.

Comparison of daily false positive counts between the improved YOLOv8 and the intelligent agent, where A represents the intelligent agent and B represents the improved YOLOv8.

As detailed in Table 8, the proposed agent demonstrates varied capability across event categories. It is most effective in dismissing stationary vehicle false alarms with 75.0% filtering accuracy and maintains a robust recall for genuine HVIC events. The category detection errors present the greatest challenge, highlighting that errors from the front-end detector are the most difficult for the backend LMM to correct. This is also related to the complex port environment and diverse objectives. This analysis confirms that the primary source of remaining false alarm stems from fundamental detection errors, rather than a failure in high-level semantic reasoning. Overall, the results show that the security intelligent agent proposed in this paper achieves a substantial reduction in false alarms. It successfully reduces more than half of the false alarms across all categories.

Table 8.

Comprehensive performance of the intelligent agent by event category.

There are several underlying factors contributing to this outstanding performance. On the one hand, due to special training strategy, the multimodal large model is extensively familiarized with the fundamental aspects of port operations during the pretraining phase. When combined with dynamic analysis after fine-tuning, this pretraining knowledge enables the model to make more accurate detections compared to the traditional target detection algorithm. The multimodal large model is capable of utilizing its previously acquired knowledge regarding port environments, layouts, and customary activities to enhance its interpretation of incoming data. Consequently, the intelligent agent possesses the capability to comprehend complex events within their contextual framework, thereby facilitating a more accurate interpretation of the HVIC event definitions present in the dataset instead of just perceiving image pixels. For example, it can accurately assess the actual distance to a target, a critical factor in distinguishing between legitimate risks and false alarms. By considering the broader context of an event, including its location within the port and typical behavioral patterns, the intelligent agent is able to make more informed decisions, significantly mitigating the incidence of false alarms.

These findings suggest that, while maintaining a high recall rate, the intelligent agent system markedly enhances alarm accuracy and diminishes the prevalence of false positives in surveillance operations, thereby providing more reliable security for the wharf.

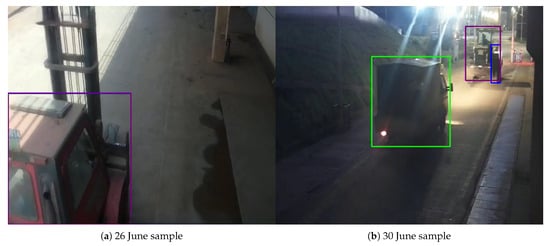

It is worth noting that although the YOLOv8-based alarm algorithm and the proposed agent performance appears comparable in field trials, alarm data from the security platform reveals persistent false positives from the improved YOLOv8 detector in operational environments. This finding indicates that false alarms undetected or unprocessed during acceptance test become amplified in production settings. Representative cases include perspective distortion due to spatial misalignment between pedestrian and vehicle detections, along with personnel detection errors.

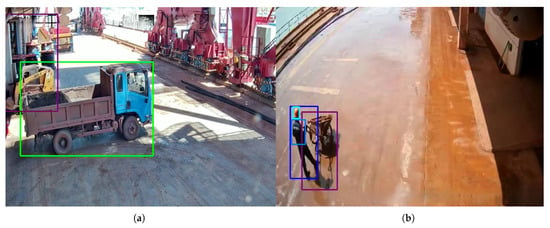

As shown in Figure 8, in the 26 June sample, the alarm video shows the forklift traveling in reverse with no visible personnel present. In the 30 June sample, a portion of the forklift is recognized as a person by the target detection algorithm. It can be seen that such detection errors are difficult to represent in field trials, but appear frequently in real-world applications. These observations demonstrate object detection algorithms’ critical dependence on environmental consistency and background clarity. The relatively stable conditions during the field trial yielded favorable results. However, actual deployment scenarios feature multiangle camera distributions and dynamically complex operational contexts. Consequently, algorithm performance degrades under variable field conditions, elevating false positive rates.

Figure 8.

False alarm sample of target detection algorithms that filtered after performing a secondary re-evaluation, where the blue box represents personnel, the green box represents trucks and the purple box represents the forklift.

A further analysis of the false alarms that the intelligent agent failed to filter reveals distinct patterns of the agent. Regarding detection errors, although the filtering accuracy is the lowest at 50.0%, its occurrence is relatively infrequent. Among the three cases the agent failed, one was a personnel misidentification; the other two were caused by the front-end detector mistaking the descending boom of a gantry crane for a truck, as illustrated in Figure 9. This is likely because the surveillance image is not complete enough or such an object is not sufficiently described in the textual annotations. The result indicates a representation gap between the two stages: the detector responds to generic shape features, while the large model lacks sufficient semantic grounding for these specific port objects. This inherent challenge of feature misalignment in a cascaded architecture is exacerbated under suboptimal imaging conditions, such as low light or motion blur, incomplete image observed in some persistent false alarm scenarios.

Figure 9.

False positive samples not filtered by the agent, where the blue box represents personnel and the green box represents trucks.

In contrast, false alarms from boarding and alighting activities are more common. Of the six such cases not filtered by the agent, one involved a person on an aerial work platform. The remaining five were all triggered when a vehicle started moving shortly before or after human interaction. When processing the clipped video, the agent deemed the vehicle’s motion state indicative of an HVIC risk. This indicates that there is still room for improvement in the model’s semantic understanding of intent and temporal context, specifically in distinguishing between authorized, brief movements associated with boarding and alighting and genuinely hazardous approaching maneuvers.

4.3.3. Ablation Study

To further demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed training strategy and to deconstruct the contribution of each core component, a comprehensive ablation study is conducted. The performance of five system configurations is compared in Table 9.

Table 9.

Ablation study on the contributions of different components of the intelligent agent.

The results systematically quantify the performance from a baseline detector to the final intelligent agent. The front-end detector only configuration, representing the improved YOLOv8 model, achieves perfect recall but with a 100% false alarm rate, illustrating the fundamental limitation of geometric detection that motivates this work. Employing the general-purpose agent (Qwen2.5-VL) brings a modest accuracy increase to 28.6%, confirming that generic multimodal models lack the specific domain knowledge for effective port safety reasoning. A first performance improvement occurs with domain adaptation. The domain-adapted agent, pretrained on port-specific image–text pairs but without fine-tuning, achieves an accuracy of 35.7%. This improvement over the general model is primarily attributed to the enrichment of the model’s visual-semantic knowledge regarding port infrastructure and assets. This enrichment aids in correcting fundamental detection errors, such as distinguishing machinery parts from vehicles. Subsequent task-specific fine-tuning delivers further optimization. The task-adapted agent, fine-tuned on HVIC video clips without prior port-specific pretraining, raises accuracy to 48.2% and reduces the false alarm rate to 57.8%. This stage equips the model with the precise discriminative strategy for HVIC events, improving its temporal reasoning and behavioral understanding.

The synergy of both domain pretraining and task fine-tuning yields the best overall performance. The full intelligent agent integrates both stages of adaptation, achieving the highest accuracy, a robust recall rate, and the lowest false alarm rate. The accuracy improvement of 17.9 percentage points over the task-adapted-only agent underscores the critical and complementary role of foundational domain knowledge. This knowledge base enables the fine-tuned model to reason from a significantly more accurate visual and semantic understanding of the scene. The synergy between these stages, as evidenced by the analysis in Figure 10, allows the final agent is capable of analyzing temporal dynamics and understanding behavior through contextual associations, in other words, it has the ability to both “Perception” (by YOLO) and “Cognition” (by LVLM). These include dismissing alarms triggered by stationary vehicles or by nonthreatening proximity during boarding activities, which simpler system configurations consistently fail to understand.

Figure 10.

Samples (a,b) of a false positive HVIC alarm of Task-Adapted agent in the ablation study, where the blue box represents personnel and their security equipment, the green box represents trucks and the purple box represents the forklift.

In summary, these findings all demonstrate the effectiveness and superiority of the intelligent agent system in port security applications. By reducing the false positive rate while maintaining high levels of precision and recall, the system significantly enhances port security and exhibits considerable potential for application in similar industrial contexts.

4.3.4. Comparative Analysis

To clearly delineate the scientific advances contributed by the proposed port security intelligent agent, this subsection positions it within the broader landscape of intelligent safety monitoring by comparing it with three representative strands of prior research: (a) rule-based or trajectory-prediction methods, (b) deep-learning-based video classification frameworks, and (c) evaluations of general-purpose multimodal large models. The relevant information of different methods has been listed in Table 10. Traditional rule-based and trajectory-prediction systems provide interpretable but unreliable estimations of risk zones [62], and their performance deteriorates in port scenarios where occlusions, irregular vehicle trajectories, and large equipment scales dominate. Deep-learning-based unsafe behavior classifiers, such as the high-speed Unsafe-Net framework [25], achieve impressive accuracy of 95.81% in recognizing predefined hazardous actions, yet they rely on the simplicity of the event and the unobstructed perspective. Essentially, they still perceive events through the visual processor rather than cognizing them.

Table 10.

Comparative analysis of representative methods for industrial safety monitoring (performance data sourced from respective literature).

In contrast, this study targets the more semantically challenging task of determining HVIC alarms. This requires filtration of false alarms arising from coarse detection bounding boxes, perspective distortions, or visually similar but safe operational contexts, which means that the alarm system must be capable of cognizing alarm events. A two-stage agent, therefore, complements these fast classifiers by introducing a dedicated multimodal model-based semantic verification layer capable of context-dependent reasoning that conventional CNN-based models cannot provide.

A more revealing comparison arises when contrasting the proposed alarm system with benchmarks evaluating general-purpose models. The iSafetyBench study [56] demonstrates that even the strongest vision–language models achieve only modest performance, with accuracy of 48.8% and F1 of about 53.4% in zero-shot industrial hazard understanding, with particularly poor results in tasks involving nuanced, context-dependent safety judgments. Additionally, the response time of large models is also worth considering. These findings highlight a structural limitation that general multimodal models lack domain grounding in industrial semantics. This study directly addresses this limitation. Systematic domain adaptation includes port-specific visual pretraining, task-oriented video fine-tuning, and the design of a two-stage multi model reasoning pipeline. Field trials show that the adapted model surpasses the general model performance ceiling, achieving 95.7% accuracy and reducing false alarms by over 50% in real port operations.

Overall, the scientific advances of this study manifest in three key aspects. First, this study shifts the problem formulation from mere visual pattern detection to contextual risk interpretation, enabling the system to reason over HVIC rather than simply detection actions. Second, a practical pathway is proposed to overcome the well-known performance degradation of general-purpose models in industrial settings through targeted domain adaptation. Third, a balanced system architecture is contributed that couples the efficiency of lightweight detectors with the deep semantic reasoning capability of adapted large models, resulting in a deployable solution that substantially improves reliability by reducing false alarms. These contributions collectively advance the state of the art toward more intelligent, robust, and operationally viable safety monitoring systems for complex port environments.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, to address the issue of the high false alarm rate of human–vehicle interface conflict detection in port environments, an analysis of alarm videos captured by the existing port security platform reveals four primary categories of false alarms: stationary vehicles, boarding and alighting activities, perspective distortion, and detection errors. In response to these findings, an architecture that specifically targets and resolves four identified classes of false alarms through multimodal reasoning is proposed, utilizing YOLOv8 and Qwen2.5-VL.

Additionally, a comprehensive dataset comprising one million port-specific images and videos has been developed to facilitate the training of the large model. By implementing domain-adaptive image pretraining and video fine-tuning strategies, the large model effectively captures the semantics of human–vehicle interface conflict events.

Consequently, the proposed port security intelligent agent, perceiving targets and understanding events, significantly improves the accuracy of HVIC’s alarm detection from the initial 19.6% to 66.1% in a realistic port environment, while reducing all four types of false positives by more than 50%. Field trials conducted in the port indicate that the system achieves an alarm accuracy of 95.7%, with a three-second response time, thereby enhancing port security. This advancement significantly reduces the burden of manual verification. The intelligent agent has received approval and has been implemented at Shulanghu Wharf in Zhoushan.

Despite these promising results, several limitations that need improvement in future work should be acknowledged. First, the system’s validation remains confined to the single bulk cargo terminal Shulanghu Wharf, and its generalizability to other port types, especially container terminals with differing layouts and operations, requires further verification. Given that the dataset used to train the agent already encompasses data from multiple docks and scenarios, based on few-shot domain adaptation principles in vision–language models [63,64], it is preliminarily estimated that in the order of 1000 annotated samples from a new environment could support effective fine-tuning. Second, although the statistical analysis of the alarm platform data has already accounted for varying weather and lighting conditions, its robustness under challenging visual conditions like low light, fog, or heavy rain has not been systematically evaluated, which is critical for all-weather port operations. Third, due to the critical importance of recall rates in alarm events, the current recall rate still needs improvement. Future work will include cross-terminal deployments, rigorous environmental robustness testing, and incremental learning strategies to handle unseen object categories, thereby strengthening the practical applicability of such multimodal systems in diverse port safety scenarios.

6. Patents

Liu Yujun, Bao Chaoxian, Zhu Zhengang, Qiao Gengjia, and Wu Gaode, S. (2025). Processing method and apparatus for port security alarms. Registration number: CN202511648154.6. CNIPA—China National Intellectual Property Administration. Filed: 12 November 2025.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., K.X., H.R. and D.-H.L.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L. and K.X.; investigation, Y.L. and K.X.; resources, K.X. and H.R.; data curation, Y.L. and K.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., K.X. and D.-H.L.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, K.X., H.R. and D.-H.L.; project administration, K.X. and H.R.; funding acquisition, K.X. and H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yujun Liu is employees of Zhejiang Provincial Seaport Investment & Operation Group Co., Ltd. and inventor of the patent “Processing method and apparatus for port security alarms” (Registration number: CN202511648154.6, filed: 12 November 2025). This patent is directly related to the research presented in this manuscript. The authors declare that there are no other competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HVIC | Human–vehicle interaction conflict |

| IoU | Intersection-over-union |

| LoRA | Low-rank adaptation |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| LVLM | Large vision–language model |

| MLP | Multilayer perceptron |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| OCR | optical character recognition |

| VIBE | Visual background extraction algorithm |

| YOLO | You only look once |

References

- Trimble, D.; Monken, J.; Sand, A. A framework for cybersecurity assessments of critical port infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Cyber Conflict (CyCon U.S.), Washington, DC, USA, 7–8 November 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, A.; Gotelli, M.; Solina, V.; Tonelli, F. Assessing Port Facility Safety: A Comparative Analysis of Global Accident and Injury Databases. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lai, K.H.; Wong, C.W.; Xin, X.; Lun, V.Y. Smart ports for sustainable shipping: Concept and practices revisited through the case study of China’s Tianjin port. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2025, 27, 50–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Xiao, G.; Li, Q.; Biancardo, S. Intelligent Maritime Shipping: A Bibliometric Analysis of Internet Technologies and Automated Port Infrastructure Applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Tang, X. A Review of Deep Learning in Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis and Its Prospects for Port Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mo, Z.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Q. CBC: Caching for cloud-based VOD systems. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2014, 73, 1663–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa Zadeh, S.B.; Esteban Perez, M.D.; López-Gutiérrez, J.S.; Fernández-Sánchez, G. Optimizing Smart Energy Infrastructure in Smart Ports: A Systematic Scoping Review of Carbon Footprint Reduction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mes, M.; Douma, A. Agent-Based Support for Container Terminals to Make Appointments with Barges. In Computational Logistics; Paias, A., Ruthmair, M., Voss, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A. The impact of neurotechnology on maritime port security—Hypothetical port. J. Transp. Secur. 2022, 15, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Sim, M.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Lim, H.R.; Lee, C.H. Strategizing Artificial Intelligence Transformation in Smart Ports: Lessons from Busan’s Resilient AI Governance Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.R.; Pereira, N.N.; de Santana Porte, M.; Campos, C.R. Sustainability practices for SDGs: A study of Brazilian ports. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 9923–9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavi, A.; Lim, G.J.; Race, B. A framework for building a smart port and smart port index. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhang, L. Detection of Safety Signs Using Computer Vision Based on Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, C.; Duguleana, M.; Boboc, R.G.; Postelnicu, C.C. Analyzing Real-Time Object Detection with YOLO Algorithm in Automotive Applications: A Review. Cmes Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 141, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, R.; Deshmukh, M. Motion-Aware Tiny Object Detection using YOLO-MoNet. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 258, 3264–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, H.; Suh, S.; Walunj, S.; Pahlevannejad, P.; Plociennik, C.; Ruskowski, M. Object Detection for Human—Robot Interaction and Worker Assistance Systems. In Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing: Enabling Intelligent, Flexible and Cost-Effective Production Through AI; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Li, Y. A YOLOv8 algorithm for safety helmet wearing detection in complex environment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniz, J.M.; Kelboucas, A.S.; Grando, R.B. Real-time robotics situation awareness for accident prevention in industry. In Proceedings of the 2024 Latin American Robotics Symposium (LARS), Arequipa, Peru, 11–14 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Genevois, T.; Spalanzani, A.; Laugier, C. Interaction-aware predictive collision detector for human-aware collision avoidance. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–7 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, R.; Miao, Y.; Zheng, J. A YOLO-Based Intelligent Detection Algorithm for Risk Assess-Ment of Construction Sites. J. Intell. Constr. 2024, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, F.; Hu, X.; Wu, X.; Nuo, M. IRWT-YOLO: A Background Subtraction-Based Method for Anti-Drone Detection. Drones 2025, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.; Chatterjee, S. YoloGA: An Evolutionary Computation Based YOLO Algorithm to Detect Personal Protective Equipment. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 49, 1251–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmir, Y.; Touati, H.; Melizou, O. Intelligent Video Recording Optimization using Activity Detection for Surveillance Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.02632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.I.; Cao, H.; Perea, A.R.; Bakir, M.E.; Chen, H.; Utsumi, S.A. YOLOv8-BS: An integrated method for identifying stationary and moving behaviors of cattle with a newly developed dataset. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önal, O.; Dandıl, E. Unsafe-Net: YOLO v4 and ConvLSTM based computer vision system for real-time detection of unsafe behaviours in workplace. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 84, 34967–34993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Mu, J. Development Status and Strategy Analysis of Medical Big Models. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2024, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, L.G.; Ng, F.Y.C.; Sauer, C.M.; Legaspi, K.E.Y.; Jain, B.; Gallifant, J.; McClurkin, M.; Hammond, A.; Goode, D.; Gichoya, J.; et al. Understanding and training for the impact of large language models and artificial intelligence in healthcare practice: A narrative review. Bmc Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report; Technical Report; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Pan, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Dai, D.; Gao, H.; Ma, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, B.; et al. DeepSeek-VL2: Mixture-of-Experts Vision-Language Models for Advanced Multimodal Understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-VL Technical Report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, D.; Huang, K.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J. FinBERT: A Pre-trained Financial Language Representation Model for Financial Text Mining. In Proceedings of the 29th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-20), Yokohama, Japan, 11–17 July 2020; pp. 4513–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Irsoy, O.; Lu, S.; Dabravolski, V.; Dredze, M.; Gehrmann, S.; Kambadur, P.; Rosenberg, D.; Mann, G. BloombergGPT: A Large Language Model for Finance. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghefi, S.A.; Huggel, C.; Muccione, V.; Khashehchi, H.; Leippold, M. Deep Climate Change: A Dataset and Adaptive domain pre-trained Language Models for Climate Change Related Tasks. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2022 Workshop on Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, Online, 9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghefi, S.A.; Stammbach, D.; Muccione, V.; Bingler, J.; Ni, J.; Kraus, M.; Allen, S.; Colesanti-Senni, C.; Wekhof, T.; Schimanski, T.; et al. ChatClimate: Grounding conversational AI in climate science. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics. YOLOv8: The Latest Advancement in Real-Time Object Detection; Ultralytics. 2023. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov8/ (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Yang, G.; Wang, J.; Nie, Z.; Yang, H.; Yu, S. A lightweight YOLOv8 tomato detection algorithm combining feature enhancement and attention. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B. Multi-crop navigation line extraction based on improved YOLO-v8 and threshold-DBSCAN under complex agricultural environments. Agriculture 2023, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y. An Improved YOLOv8 network for detecting electric pylons based on optical satellite image. Sensors 2024, 24, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Cao, S.; Zhang, J.; Hou, Z. Steel surface defect detection algorithm based on YOLOv8. Electronics 2024, 13, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, H.; Dai, D.; Wang, H.; Shan, Z.; Wu, H. CKAN-YOLOv8: A Lightweight Multi-Task Network for Underwater Target Detection and Segmentation in Side-Scan Sonar. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, Y.; Asilian-Mahabadi, H.; Hajizadeh, E.; Hassanzadeh-Rangi, N.; Bastani, H.; Behzadan, A.H. Factors influencing unsafe behaviors and accidents on construction sites: A review. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2014, 20, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Bao, Q.; Jia, B.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. An unsafe behavior detection method based on improved YOLO framework. Electronics 2022, 11, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, H. An improved yolov5s-based algorithm for unsafe behavior detection of construction workers in construction scenarios. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Weng, J.; Han, B. A novel deep learning framework for detecting seafarer’s unsafe behavior. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2023, 15, 1299–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhu, J.; Li, Z.; Chong, H.Y. Clarifying Unsafe Behaviors of Construction Workers through a Complex Network of Unsafe Behavior Chains. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Guo, H.; Ding, Q.; Li, H.; Skitmore, M. An experimental study of real-time identification of construction workers’ unsafe behaviors. Autom. Constr. 2017, 82, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.S.; Yang, C.S. Safety leadership and safety behavior in container terminal operations. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, Y. Exploring the effect of timely reminder on maritime unsafe acts. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukak, M.M.U.; Berek, N.C.; Sahdan, M.; Nabuasa, D.J. Unsafe Behavior on Dockworkers at Lewoleba Sea Port. In Proceedings of the The International Conference on Public Health Proceeding, Solo, Indonesia, 29–30 May 2021; Volume 6, pp. 607–615. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarok, M.A.; Martiana, T.; Widajati, N. An analysis of factors associated with the safety behavior of ship inspection employees safety in port health office class I Surabaya. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolkefli, S.N.A.; Kadir, Z.A.; Ensan, A.H. Improvement of Unsafe Act and Unsafe Condition Online Reporting System at Port. Prog. Eng. Appl. Technol. 2024, 5, 776–785. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Park, S.; Lee, H. AutoCon: Large Vision–Language Models for Automatic Construction Hazard Assessment. Autom. Constr. 2025, 160, 105123. [Google Scholar]