Molecular Mechanisms of Chemoresistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Narrative Review with Present and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

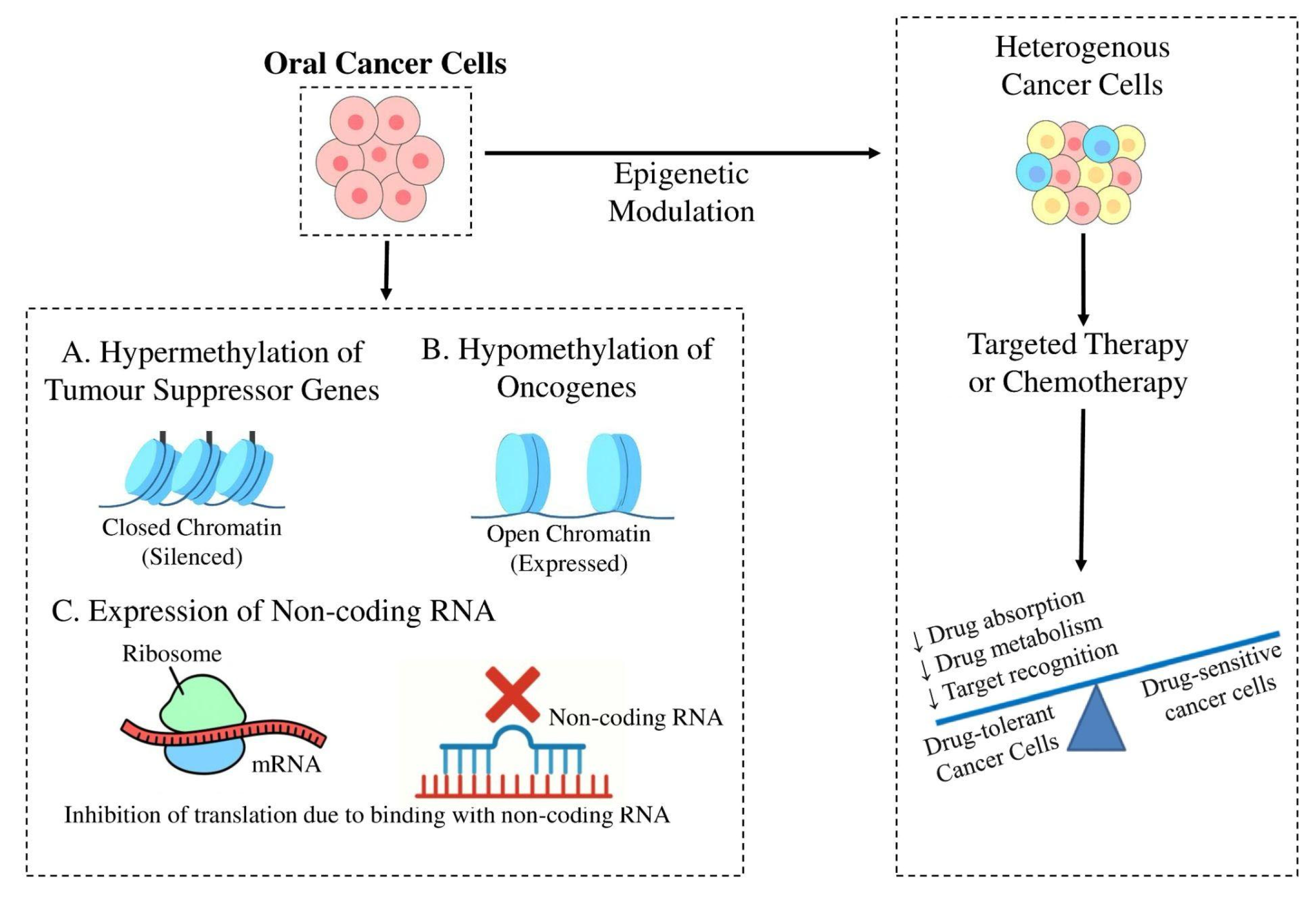

2. Epigenetic Alterations Driving Chemoresistance

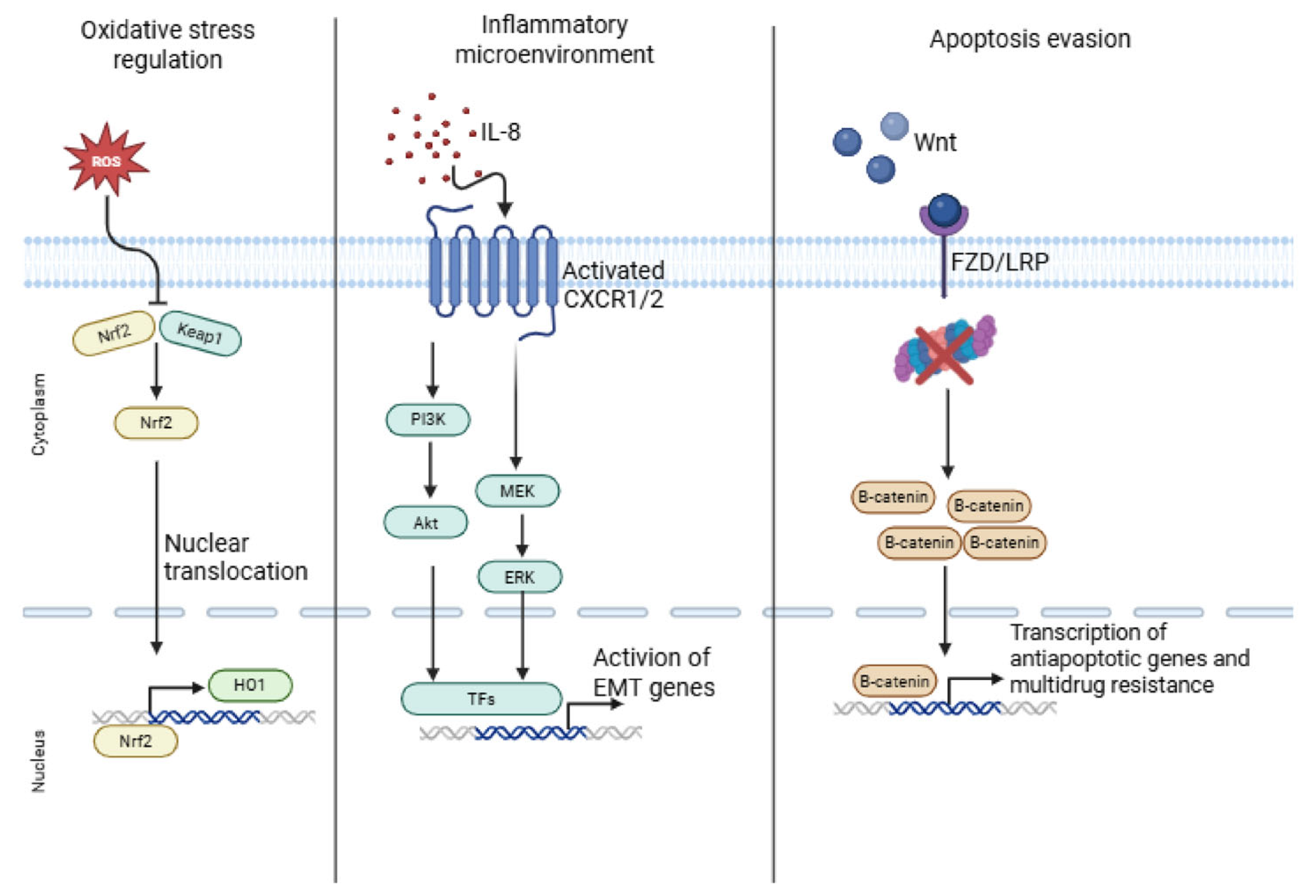

3. Signaling Pathways Involved in Chemoresistance

4. CSCs and Tumor Cell Plasticity in OSCC

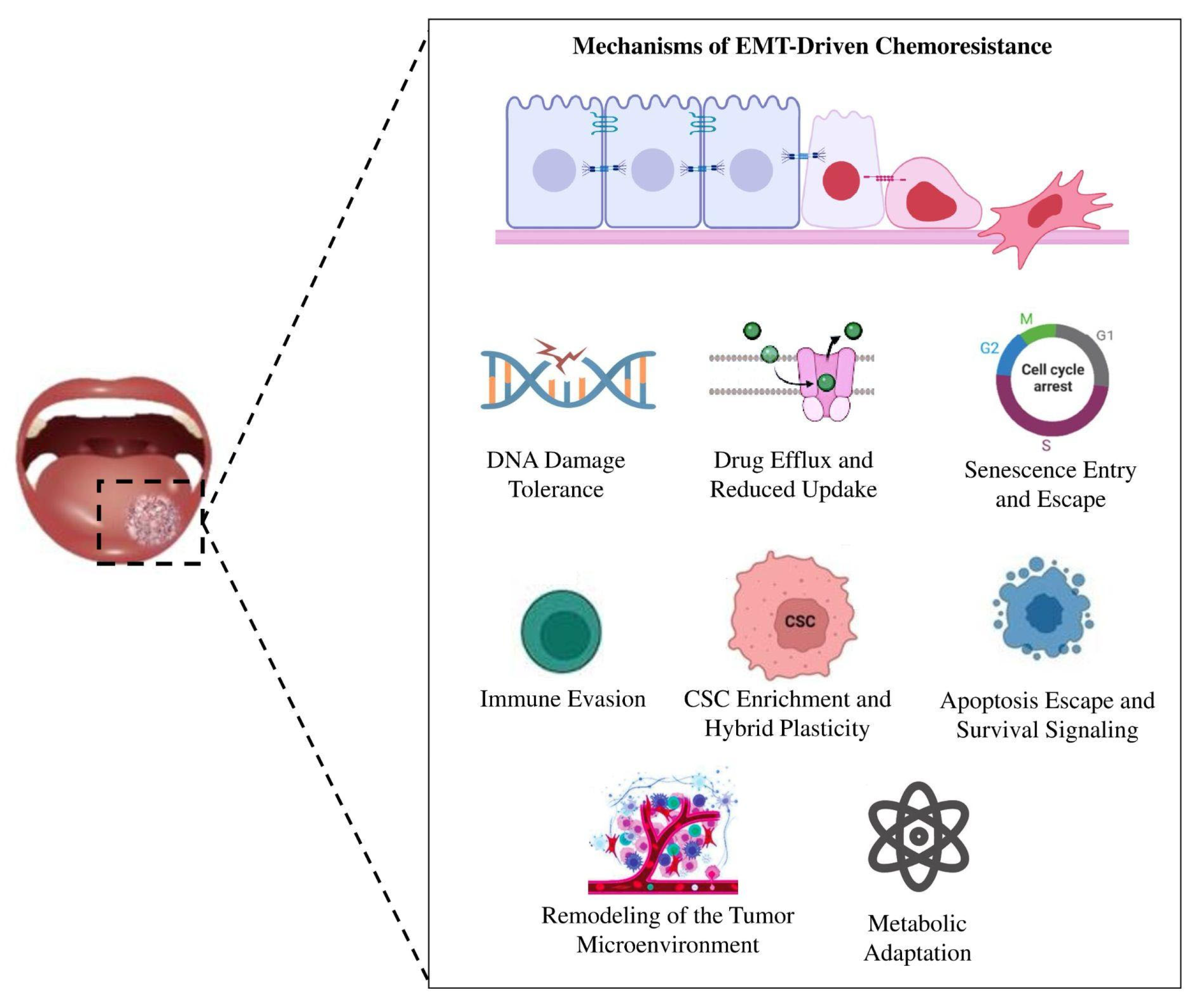

5. From Plasticity to Persistence: EMT and Chemoresistance in OSCC

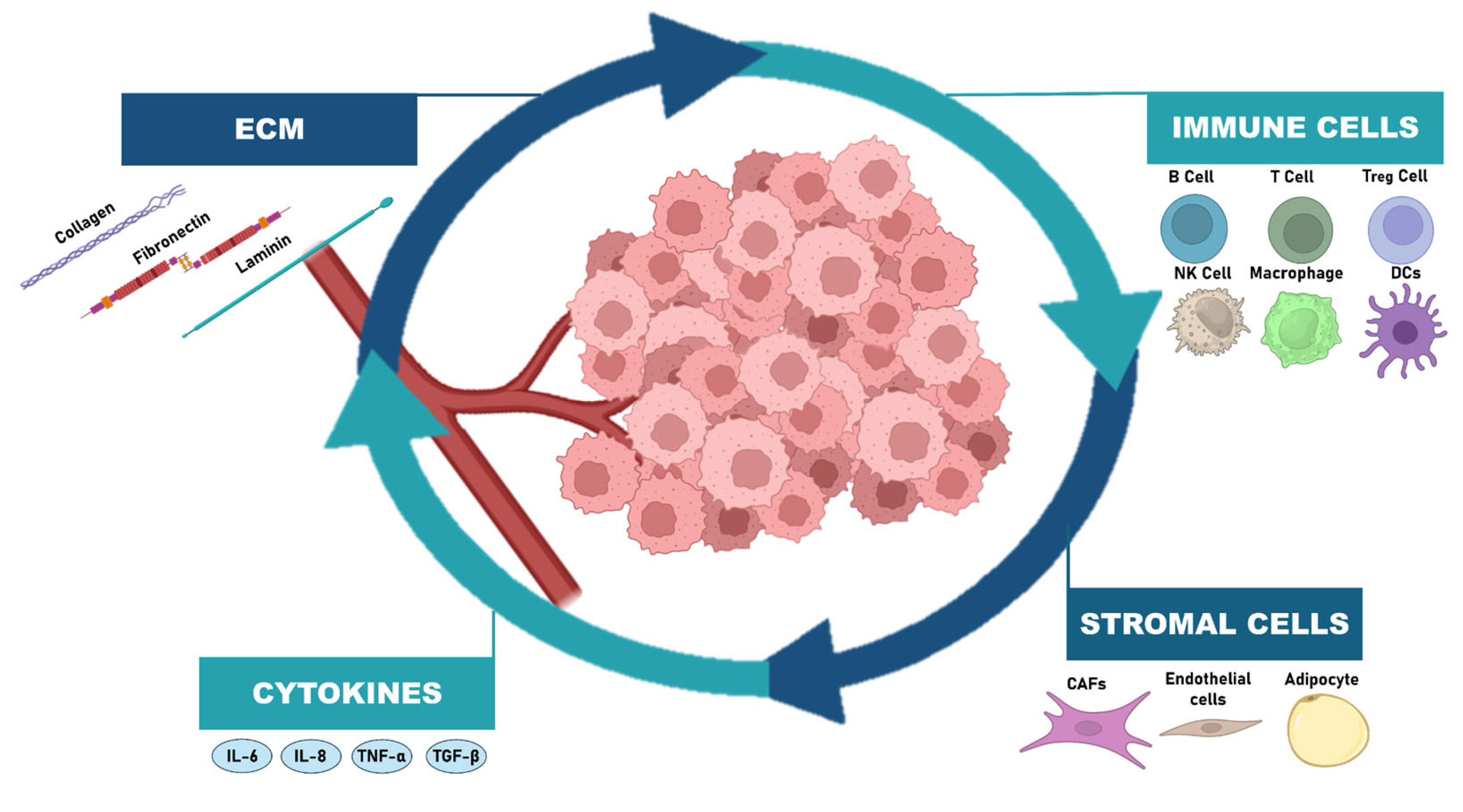

6. Reciprocal Crosstalk with TME

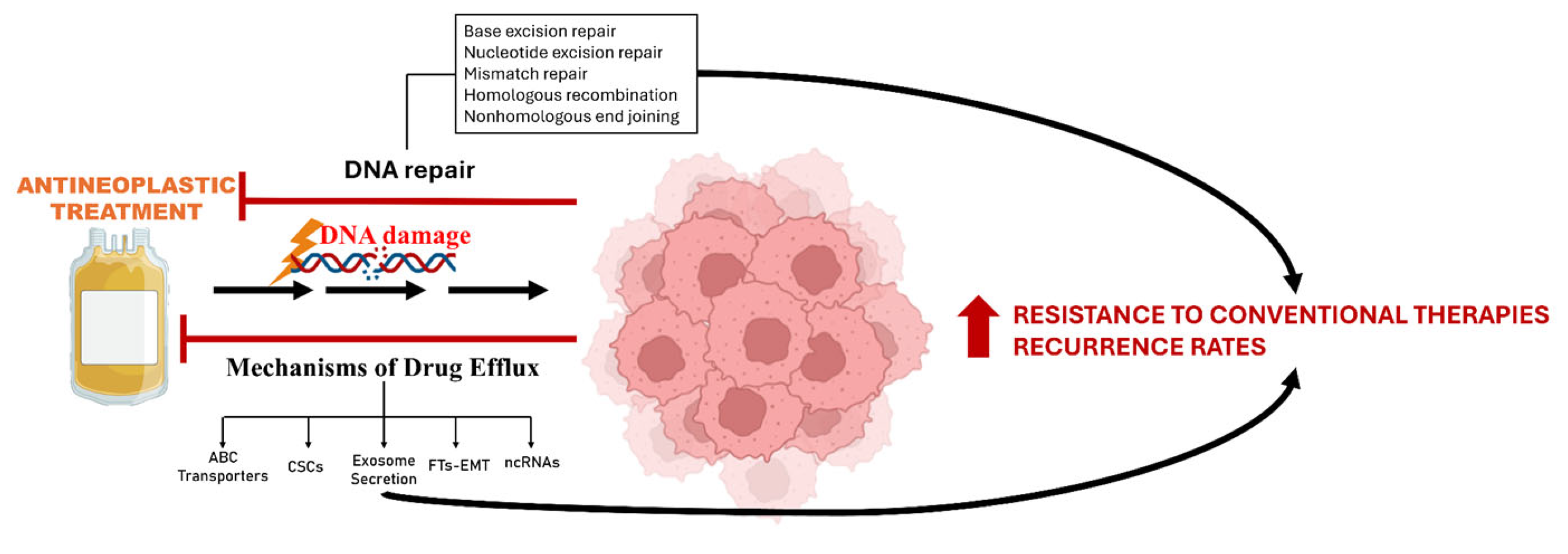

7. Mechanisms of Drug Efflux and DNA Damage Response

8. Therapeutic Resistance: Clinical Implications in OSCC

9. Targeting Molecular Mechanisms of Chemoresistance: Current Strategies and Future Perspectives

10. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| ABCB1 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (P-glycoprotein) |

| ABCC1 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 1 (multidrug resistance-associated protein 1) |

| ABCG2 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (breast cancer resistance protein) |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| ALDH1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 |

| ATM/ATR | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated/ATR serine/threonine kinase |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BMI1 | B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog |

| CAF/CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblast(s) |

| CASP8 | Caspase-8 |

| CD133 | Cluster of differentiation 133 |

| CD44 | Cluster of differentiation 44 |

| CDKN2A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16INK4a) |

| ceRNA | Competing endogenous RNA |

| CHK1/CHK2 | Checkpoint kinase 1/2 |

| CSC/CSCs | Cancer stem cell(s) |

| CTLs | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

| CXCR1/CXCR2 | C-X-C chemokine receptor 1/2 |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| DNMTi | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| FOXD1 | Forkhead box D1 |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta |

| HDAC/HDACi | Histone deacetylase/Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| HMG20A | High mobility group protein 20A |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| IL-1β/IL-6/IL-8 | Interleukin-1 beta/6/8 |

| JAK/STAT3 | Janus kinase/Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| KAT2B/KAT6A/KAT6B | Lysine acetyltransferases 2B, 6A, and 6B |

| KRT16 | Keratin 16 |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| LPP | LIM domain-containing preferred translocation partner in lipoma |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MALAT1 | Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 |

| MDR1 | Multidrug resistance gene 1 |

| MET | Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition |

| miRNA/microRNA | MicroRNA |

| MMP-2/MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2/9 |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| ncRNA | Non-coding RNA |

| OPMDs | Oral potentially malignant disorders |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| PAFR | Platelet-activating factor receptor |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PD-1/PD-L1 | Programmed cell death protein-1/ligand-1 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PLOD2 | Procollagen-lysine 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| p53/TP53 | Tumor protein p53 |

| p21 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A |

| p16 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| SNAIL/SLUG/TWIST/ZEB1/ZEB2 | EMT-related transcription factors |

| SMAC | Second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases |

| SOX2/OCT4/NANOG/KLF4/c-Myc | Stemness transcription factors |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TAM/TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophage(s) |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| Th | Helper T cells |

| TIS | Therapy-induced senescence |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| Wnt/β-catenin | Wingless-related integration site/β-catenin pathway |

| xCT | Cystine/glutamate antiporter (SLC7A11) |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, S.; Gao, L.; Zhi, K.; Ren, W. The Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Aspects of Cisplatin Resistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 761379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marta, G.N.; Riera, R.; Bossi, P.; Zhong, L.P.; Licitra, L.; Macedo, C.R.; de Castro, G., Jr.; Carvalho, A.L.; William, W.N., Jr.; Kowalski, L.P. Induction Chemotherapy Prior to Surgery with or without Postoperative Radiotherapy for Oral Cavity Cancer Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 2596–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotta, A.; Marciano, M.L.; Sabbatino, F.; Ottaiano, A.; Cascella, M.; Pontone, M.; Montano, M.; Calogero, E.; Longo, F.; Fasano, M.; et al. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Cancers: A Paradigm Shift in Treatment Approach. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukowski, K.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Zhu, S.; Chen, J. Tumor Microenvironment and Immunotherapy of Oral Cancer. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Morais, E.F.; de Oliveira, L.Q.R.; Marques, C.E.; Téo, F.H.; Rocha, G.V.; Rodini, C.O.; Gurgel, C.A.; Salo, T.; Graner, E.; Coletta, R.D. Generation and Characterization of Cisplatin-Resistant Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells Displaying an Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Signature. Cells 2025, 14, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima de Oliveira, J.; Moré Milan, T.; Longo Bighetti-Trevisan, R.; Fernandes, R.R.; Machado Leopoldino, A.; Oliveira de Almeida, L. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Stem Cells: A Route to Acquired Cisplatin Resistance through Epigenetics in HNSCC. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyachamy, S.; Yadalam, P.K.; Kumar, R.N.; Charumathi, P.; Devi, M.B.; Ardila, C.M. Predicting and identifying key genes driving chemoresistance and cancer stemness in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Netw. Model. Anal. Health Inform. Bioinform. 2025, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorna, D.; Paluszczak, J. Targeting Cancer Stem Cells as a Strategy for Reducing Chemotherapy Resistance in Head and Neck Cancers. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 13417–13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Chikuda, J.; Shirota, T.; Yamamoto, Y. Impact of Non-Coding RNAs on Chemotherapeutic Resistance in Oral Cancer. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, S.; Jamal, A.; Teh, M.T.; Waseem, A. Major Molecular Signaling Pathways in Oral Cancer Associated with Therapeutic Resistance. Front. Oral Health 2021, 1, 603160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, H.L.; Chiou, J.F.; Chen, Y.J. Molecular Mechanisms of Chemotherapy Resistance in Head and Neck Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 640392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, A.; Rahman, H.; Ambudkar, S.V. Advances in the Structure, Mechanism and Targeting of Chemoresistance-Linked ABC Transporters. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrie, M.; Brugge, J.S.; Mills, G.B.; Zervantonakis, I.K. Therapy Resistance: Opportunities Created by Adaptive Responses to Targeted Therapies in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, P.; Malhotra, J.; Kulkarni, P.; Horne, D.; Salgia, R.; Singhal, S.S. Emerging therapeutic strategies to overcome drug resistance in cancer cells. Cancers 2024, 16, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ma, T.; Yu, B. Targeting Epigenetic Regulators to Overcome Drug Resistance in Cancers. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadida, H.Q.; Abdulla, A.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Hashem, S.; Macha, M.A.; Akil, A.S.A.; Bhat, A.A. Epigenetic Modifications: Key Players in Cancer Heterogeneity and Drug Resistance. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 39, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Qin, X.; Zhou, F.; Yan, R.; Hao, S.; Ji, Y.; Li, D.; Chen, S. Epigenetic Regulation in Cancer Therapy: From Mechanisms to Clinical Advances. MedComm Oncol. 2024, 3, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, R.M.; Squarize, C.H.; de Almeida, L.O. Epigenetic Modifications and Head and Neck Cancer: Implications for Tumor Progression and Resistance to Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsa, P.P.; Jindal, Y.; Bhadwalkar, J.; Chamoli, A.; Upadhyay, V.; Mandoli, A. Role of Epigenetics in OSCC: An Understanding above Genetics. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falzone, L.; Lupo, G.; La Rosa, G.R.M.; Crimi, S.; Anfuso, C.D.; Salemi, R.; Rapisarda, E.; Libra, M.; Candido, S. Identification of Novel MicroRNAs and Their Diagnostic and Prognostic Significance in Oral Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, I.; Tan, J.; Alam, A.; Idrees, M.; Brenan, P.A.; Coletta, R.D.; Kujan, O. Epigenetics in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2024, 53, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaździcka, J.; Gołąbek, K.; Strzelczyk, J.K.; Ostrowska, Z. Epigenetic Modifications in Head and Neck Cancer. Biochem. Genet. 2020, 58, 213–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapado-González, Ó.; Martínez-Reglero, C.; Salgado-Barreira, Á.; Muinelo-Romay, L.; Muinelo-Lorenzo, J.; López-López, R.; Díaz-Lagares, Á.; Suárez-Cunqueiro, M.M. Salivary DNA Methylation as an Epigenetic Biomarker for Head and Neck Cancer. Part I: A Diagnostic Accuracy Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Biswas, B.; Manoj Appadan, A.; Shah, J.; Pal, J.K.; Basu, S.; Sur, S. Non-coding RNAs in oral cancer: Emerging roles and clinical applications. Cancers 2023, 15, 3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Lin, B.; Yang, S.; Deng, F.; Yang, X.; Li, A.; Xia, W.; Gao, C.; Lei, S.; et al. Non-coding RNA and drug resistance in head and neck cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakittnen, J.; Weeramange, C.E.; Wallace, D.F.; Duijf, P.H.G.; Cristino, A.S.; Kenny, L.; Vasani, S.; Punyadeera, C. Noncoding RNAs in oral cancer. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2023, 14, e1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, T.M.; Eskenazi, A.P.E.; Bighetti-Trevisan, R.L.; de Almeida, L.O. Epigenetic Modifications Control Loss of Adhesion and Aggressiveness of Cancer Stem Cells Derived from Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Intrinsic Resistance to Cisplatin. Arch. Oral Biol. 2022, 141, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, E.S.; Wagner, V.P.; Cabral Ramos, J.; Lambert, D.W.; Castilho, R.M.; Leme, A.F.P. Epigenetic Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment in Head and Neck Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 164, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumetti, L.; Lombardi, R.; Iannelli, F.; Parmigiani, B.; Avigliano, A.; De Giorgio, E.; Barcellona, A. Epigenetic Approaches to Overcome Fluoropyrimidines Resistance in Solid Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, I.; Badrzadeh, F.; Tsentalovich, Y.; Gaykalova, D.A. Connecting the Dots: Investigating the Link between Environmental, Genetic, and Epigenetic Influences in Metabolomic Alterations in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuzzi, D.; Simão, T.A.; Dias, F.; Ribeiro Pinto, L.F.; Soares-Lima, S.C. Head and neck cancers are not alike when tarred with the same brush: An epigenetic perspective from the cancerization field to prognosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, J.; Figg, W.D. Epigenetic Approaches to Overcoming Chemotherapy Resistance. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1013–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, J.; Asaumi, J.-I.; Kawai, N.; Tsujigiwa, H.; Yanagi, Y.; Nagatsuka, H.; Inoue, T.; Kokeguchi, S.; Kawasaki, S.; Kuroda, M. Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitor FR901228 on the expression level of telomerase reverse transcriptase in oral cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005, 56, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesgari, H.; Esmaelian, S.; Nasiri, K.; Ghasemzadeh, S.; Doroudgar, P.; Payandeh, Z. Epigenetic Regulation in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Microenvironment: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowska, K.; Sobecka, A.; Rawłuszko-Wieczorek, A.A.; Suchorska, W.M.; Golusiński, W. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Epigenetic Landscape. Diagnostics 2020, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, C. Targeting epigenetic dysregulations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Dent. Res. 2025, 104, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, L.; Peng, X.; Fan, Q.; Wei, S.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Jin, H.; Wu, B.; Huang, M.; et al. Emerging mechanisms and applications of ferroptosis in the treatment of resistant cancers. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siquara da Rocha, L.O.; de Morais, E.F.; de Oliveira, L.Q.R.; Barbosa, A.V.; Lambert, D.W.; Gurgel Rocha, C.A.; Coletta, R.D. Exploring beyond common cell death pathways in oral cancer: A systematic review. Biology 2024, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, S. Nrf2/HO-1 alleviates disulfiram/copper-induced ferroptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem. Genet. 2024, 62, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Li, L.; Wu, G. Induction of Ferroptosis by Carnosic Acid-Mediated Inactivation of Nrf2/HO-1 Potentiates Cisplatin Responsiveness in OSCC Cells. Mol. Cell Probes 2022, 64, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.C.; Jang, T.H.; Tung, S.L.; Yen, T.C.; Chan, S.H.; Wang, L.H. A Novel miR-365-3p/EHF/Keratin 16 Axis Promotes Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Metastasis, Cancer Stemness and Drug Resistance via Enhancing β5-Integrin/c-Met Signaling Pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.C.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Hu, F.C.; Xie, N.; Lü, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, H.Z. Overexpression of β-Catenin Induces Cisplatin Resistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 5378567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Chen, G.; Sun, D.; Lei, M.; Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Xue, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; et al. Exosomes Containing miR-21 Transfer the Characteristic of Cisplatin Resistance by Targeting PTEN and PDCD4 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2017, 49, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K.; Kasamatsu, A.; Ando, T.; Saito, T.; Nobuchi, T.; Nozaki, R.; Iyoda, M.; Uzawa, K. Ginkgolide B Regulates CDDP Chemoresistance in Oral Cancer via the Platelet-Activating Factor Receptor Pathway. Cancers 2021, 13, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, A.; Bévant, K.; Blanpain, C. Cancer cell plasticity during tumor progression, metastasis and response to therapy. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 1063–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Clairambault, J. Cell plasticity in cancer cell populations. F1000Research 2020, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Diz, V.; Lorenzo-Sanz, L.; Bernat-Peguera, A.; López-Cerda, M.; Muñoz, P. Cancer cell plasticity: Impact on tumor progression and therapy response. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018, 53, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, I.G.; Cuadra-Zelaya, F.J.M.; Bizeli, A.L.V.; Palma, P.V.B.; Mariano, F.V.; Salo, T.; Coletta, R.D.; Bastos, D.C.; Graner, E. Isolation and phenotypic characterization of cancer stem cells from metastatic oral cancer cells. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 4886–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.E.; Sivanandan, R.; Kaczorowski, A.; Wolf, G.T.; Kaplan, M.J.; Dalerba, P.; Weissman, I.L.; Clarke, M.F.; Ailles, L.E. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Al-Brakati, A.; Abidi, N.H.; Almasri, M.A.; Almeslet, A.S.; Patil, V.R.; Raj, A.T.; Bhandi, S. CD44-positive cancer stem cells from oral squamous cell carcinoma exhibit reduced proliferation and stemness gene expression upon adipogenic induction. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Roy, S.; Kar, M.; Roy, S.; Thakur, S.; Padhi, S.; Akhter, Y.; Banerjee, B. Role of Telomeric TRF2 in Orosphere Formation and CSC Phenotype Maintenance through Efficient DNA Repair Pathway and Its Correlation with Recurrence in OSCC. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2018, 14, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhumal, S.N.; Choudhari, S.K.; Patankar, S.; Ghule, S.S.; Jadhav, Y.B.; Masne, S. Cancer Stem Cell Markers, CD44 and ALDH1, for Assessment of Cancer Risk in OPMDs and Lymph Node Metastasis in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2022, 16, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluja, T.S.; Kumar, V.; Agrawal, M.; Tripathi, A.; Meher, R.K.; Srivastava, K.; Gupta, A.; Singh, A.; Chaturvedi, A.; Singh, S.K. Mitochondrial Stress-Mediated Targeting of Quiescent Cancer Stem Cells in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2020, 12, 4519–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Antin, P.; Berx, G.; Blanpain, C.; Brabletz, T.; Bronner, M.; Campbell, K.; Cano, A.; Casanova, J.; Christofori, G.; et al. Guidelines and Definitions for Research on Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Las Rivas, J.; Brozovic, A.; Izraely, S.; Casas-Pais, A.; Witz, I.P.; Figueroa, A. Cancer Drug Resistance Induced by EMT: Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 2279–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, N.; Manavi, M.S.; Faghihkhorasani, F.; Fakhr, S.S.; Baei, F.J.; Khorasani, F.F.; Zare, M.M.; Far, N.P.; Rezaei-Tazangi, F.; Ren, J.; et al. Harnessing Function of EMT in Cancer Drug Resistance: A Metastasis Regulator Determines Chemotherapy Response. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024, 43, 457–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangarh, R.; Saini, R.V.; Saini, A.K.; Singh, T.; Joshi, H.; Ramniwas, S.; Shahwan, M.; Tuli, H.S. Dynamics of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity driving cancer drug resistance. Cancer Pathog. Ther. 2024, 3, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Guo, L.; Wang, B. Senescence and Oral Cancer: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Transl. Dent. Res. 2025, 1, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Sun, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Shi, X.; Zhou, H. Persistent Accumulation of Therapy-Induced Senescent Cells: An Obstacle to Long-Term Cancer Treatment Efficacy. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2025, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomares, B.H.; Martins, M.D.; Martins, M.A.T.; Squarize, C.H.; Castilho, R.M. Future Perspectives in Senescence-Based Therapies for Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Morais, E.F.; Rolim, L.S.A.; de Melo Fernandes Almeida, D.R.; de Farias Morais, H.G.; de Souza, L.B.; de Almeida Freitas, R. Biological Role of Epithelial-Mesenchymal-Transition-Inducing Transcription Factors in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020, 119, 104904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Morais, E.F.; de Farias Morais, H.G.; de Moura Santos, E.; Barboza, C.A.G.; Téo, F.H.; Salo, T.; Coletta, R.D.; de Almeida Freitas, R. TWIST1 Regulates Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion and Is a Prognostic Marker for Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2023, 52, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Morais, E.F.; Morais, H.G.F.; de França, G.M.; Téo, F.H.; Galvão, H.C.; Salo, T.; Coletta, R.D.; Freitas, R.A. SNAIL1 Is Involved in the Control of the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2023, 135, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Morais, E.F.; Santos, H.B.P.; Cavalcante, I.L.; Rabenhorst, S.H.B.; dos Santos, J.N.; Galvão, H.C.; Freitas, R.A. Twist and E-Cadherin Deregulation Might Predict Poor Prognosis in Lower Lip Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lu, X.; Yu, R. lncRNA MALAT1 Promotes EMT Process and Cisplatin Resistance of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma via PI3K/AKT/m-TOR Signal Pathway. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 4049–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, M.; Wang, C.; Ouyang, Y.; Chen, X.; Bai, J.; Hu, Y.; Song, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q. Forkhead Box D1 Promotes EMT and Chemoresistance by Upregulating lncRNA CYTOR in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2021, 503, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Sun, L.; Xie, S.; Zhang, S.; Fan, S.; Li, Q.; Chen, W.; Pan, G.; Wang, W.; Weng, B.; et al. Chemotherapy-Induced Long Non-Coding RNA 1 Promotes Metastasis and Chemo-Resistance of TSCC via the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 1494–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Kim, Y.K.; Yun, P.Y. Cisplatin Plus Cetuximab Inhibits Cisplatin-Resistant Human Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Migration and Proliferation but Does Not Enhance Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, H.; Hirai, M.; Kato, K.; Bou-Gharios, G.; Nakamura, H.; Kawashiri, S. Eribulin Sensitizes Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells to Cetuximab via Induction of Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 3139–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickasamy, M.K.; Vishwa, R.; Bharathwaj Chetty, B.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Abbas, M.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Cytokine Symphony: Deciphering the Tumor Microenvironment and Metastatic Axis in Oral Cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025, 85, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Diel, L.; Ramos, G.; Pinto, A.; Bernardi, L.; Yates, J., 3rd; Lamers, M. Tumor Microenvironment and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Crosstalk between the Inflammatory State and Tumor Cell Migration. Oral Oncol. 2021, 112, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożyk, A.; Wojas-Krawczyk, K.; Krawczyk, P.; Milanowski, J. Tumor Microenvironment: A Short Review of Cellular and Interaction Diversity. Biology 2022, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Crosstalk between Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Immune Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment: New Findings and Future Perspectives. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Manavalan, M.J.; Jasmine, S.H.; Krishnan, M. Tumor microenvironment in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Implications for novel therapies. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, B.; Hu, Q.; Qin, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, W.; Yu, X.; Xu, J. The Impact of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts on Major Hallmarks of Pancreatic Cancer. Theranostics 2018, 8, 5072–5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Han, C.; Wang, S.; Fang, P.; Ma, Z.; Xu, L.; Yin, R. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: An Emerging Target of Anti-Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, L.; Chouaib, S.; Thiery, J. Alteration of the Antitumor Immune Response by Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Barreto, J.B.; Andreu, P.; Vasquez, L.; Tawfik, D.; Kolhatkar, N.; Coussens, L.M. CD4(+) T Cells Regulate Pulmonary Metastasis of Mammary Carcinomas by Enhancing Protumor Properties of Macrophages. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weagel, E.; Smith, C.; Liu, P.G.; Robison, R.; O’Neill, K. Macrophage Polarization and Its Role in Cancer. J. Clin. Cell Immunol. 2015, 6, 338. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Dong, X.; Li, B. Tumor Microenvironment in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1485174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeger, S.; Meyle, J. The Role of Programmed Death Receptor (PD-)1/PD-Ligand (L)1 in Periodontitis and Cancer. Periodontology 2000, 96, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.; Braun, M.; Dietrich, D.; Aktekin, S.; Höft, S.; Kristiansen, G.; Göke, F.; Schröck, A.; Brägelmann, J.; Held, S.A.E.; et al. PD-L1: A Novel Prognostic Biomarker in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 52889–52900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.M.; Simon, M.C. The Tumor Microenvironment. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R921–R925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamaru, N.; Fukuda, N.; Akita, K.; Kudoh, K.; Miyamoto, Y. Association of PD-L1 and ZEB-1 Expression Patterns with Clinicopathological Characteristics and Prognosis in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, H.G.; Costa, C.S.; Gonçalo, R.I.; Carlan, L.M.; Morais, E.F.; Galvão, H.C.; Freitas, R.D. Biological Role of the Bidirectional Interaction between Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and PD-L1 Expression in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas: A Systematic Review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2023, 28, e395–e403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, Y.; Noguchi, K.; Kitamura, M.; Makihara, Y.; Omae, T.; Hanawa, S.; Yoshikawa, K.; Takaoka, K.; Kishimoto, H. Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Induces PD-L1 Expression and an Invasive Phenotype of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. Cancers 2024, 16, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Farias Morais, H.G.; Martins, H.D.D.; da Paz, A.R.; de Morais, E.F.; Bonan, P.R.F.; de Almeida Freitas, R. Bidirectional Interaction between Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and PD-1/PD-L1 Expression in Tongue Carcinogenesis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2025, 176, 106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghban, R.; Roshangar, L.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Seidi, K.; Ebrahimi-Kalan, A.; Jaymand, M.; Kolahian, S.; Javaheri, T.; Zare, P. Tumor Microenvironment Complexity and Therapeutic Implications at a Glance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Coussens, L.M. Accessories to the Crime: Functions of Cells Recruited to the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, X.; Cao, P.; Fei, W.; Zhou, H.; Tang, N.; Liu, Y. Interleukin-6 Mediated Inflammasome Activation Promotes Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Progression via JAK2/STAT3/Sox4/NLRP3 Signaling Pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierly, G.; Celentano, A.; Breik, O.; Moslemivayeghan, E.; Patini, R.; McCullough, M.; Yap, T. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, T.; Chai, Y.; Chen, F. TGF-β Signaling in Progression of Oral Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Yu, Z.L.; Jia, J. The Roles of Exosomes in the Diagnose, Development and Therapeutic Resistance of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lou, Q.Y.; Yang, W.Y.; Wang, Y.R.; Chen, R.; Wang, L.; Xu, T.; Zhang, L. The Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Drug Resistance of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Therapeutic Potential. Cancer Commun. 2021, 41, 981–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, C.M.; Singh, A.T.K. Apoptosis: A Target for Anticancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Dong, P.; Li, D.; Gao, S. Expression and Function of ABCG2 in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Cell Lines. Exp. Ther. Med. 2011, 2, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Cai, T.; Bai, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chiba, P.; Cai, Y. State of the Art of Overcoming Efflux Transporter Mediated Multidrug Resistance of Breast Cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarathna, P.J.; Patil, S.R.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Daniel, S.; Aileni, K.R.; Karobari, M.I. Oral Cancer Stem Cells: A Comprehensive Review of Key Drivers of Treatment Resistance and Tumor Recurrence. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 989, 177222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Zhang, X.; Gan, R.; Lin, S.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, D.; Lu, Y. WNT3 Promotes Chemoresistance to Oxaliplatin in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma via Regulating ABCG2 Expression. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Z.J.; Khoo, X.H.; Lim, P.T.; Goh, B.H.; Ming, L.C.; Lee, W.L.; Goh, H.P. Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Chemoresistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 629888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, J.M.; Aguirre, A.J.; Shapiro, G.I.; D’Andrea, A.D. Biomarker-Guided Development of DNA Repair Inhibitors. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 1070–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomella, S.; Cassandri, M.; Melaiu, O.; Marampon, F.; Gargari, M.; Campanella, V.; Rota, R.; Barillari, G. DNA Damage Response Gene Signature as Potential Treatment Markers for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, L.; Meijie, Z.; Wenjing, Z.; Bing, Z.; Yanhao, D.; Shanshan, L.; Yongle, Q. HMG20A Was Identified as a Key Enhancer Driver Associated with DNA Damage Repair in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuch, L.F.; de Arruda, J.A.A.; Viana, K.S.S.; Caldeira, P.C.; Abreu, M.H.N.G.; Bernardes, V.F.; Aguiar, M.C.F. DNA Damage-Related Proteins in Smokers and Non-Smokers with Oral Cancer. Braz. Oral Res. 2022, 36, e027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Nickel Carcinogenesis Mechanism: DNA Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, A.; Takahashi, H.; Patel, A.A.; Osman, A.A.; Myers, J.N. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in OSCC with TP53 Mutations. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, C.; Cho, J.-Y.; Güngör, C. Therapeutic resistance and combination therapy for cancer: Recent developments and future directions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Z. A two-decade bibliometric analysis of drug resistance in oral cancer research: Patterns, trends, and future directions. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. Exploring cell death pathways in oral cancer: Mechanisms, therapeutic strategies, and future perspectives. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesham, A.; AlOtaibi, F.; Kim, D.D.; Alshamrani, Y.; Hyppolito, J.; Jubala, K. Neoadjuvant pembrolizumab-carboplatin-paclitaxel in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: A case report and literature review. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 11, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Morais, E.F.d.; de Oliveira, L.Q.R.; Marques, C.E.; Morais, H.G.d.F.; Moreira, D.G.L.; Albuquerque, L.d.A.; Silva, J.R.V.; Freitas, R.d.A.; Coletta, R.D. Molecular Mechanisms of Chemoresistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Narrative Review with Present and Future Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010525

Morais EFd, de Oliveira LQR, Marques CE, Morais HGdF, Moreira DGL, Albuquerque LdA, Silva JRV, Freitas RdA, Coletta RD. Molecular Mechanisms of Chemoresistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Narrative Review with Present and Future Perspectives. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):525. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010525

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorais, Everton Freitas de, Lilianny Querino Rocha de Oliveira, Cintia Eliza Marques, Hannah Gil de Farias Morais, Déborah Gondim Lambert Moreira, Lucas de Araújo Albuquerque, José Roberto Viana Silva, Roseana de Almeida Freitas, and Ricardo D. Coletta. 2026. "Molecular Mechanisms of Chemoresistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Narrative Review with Present and Future Perspectives" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010525

APA StyleMorais, E. F. d., de Oliveira, L. Q. R., Marques, C. E., Morais, H. G. d. F., Moreira, D. G. L., Albuquerque, L. d. A., Silva, J. R. V., Freitas, R. d. A., & Coletta, R. D. (2026). Molecular Mechanisms of Chemoresistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Narrative Review with Present and Future Perspectives. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010525