Abstract

The study aimed to determine the effect of acute, one-time physical effort performed under different environmental temperature conditions on erythrocyte deformability in healthy young men. This exploratory randomized parallel-group study involved 30 men randomly assigned to an experimental group exercising at −10 °C in a climatic chamber and a control group exercising under thermoneutral outdoor conditions. Erythrocyte deformability was assessed using the elongation index (EI), reflecting erythrocyte elasticity and the ability to pass through microcirculation vessels. Participants performed an incremental 20 m shuttle run test. Venous blood samples were collected before and immediately after exercise, and erythrocyte deformability was analyzed using a Lorrca analyzer across a shear stress range of 0.30–60.00 Pa. A two-factor repeated-measures analysis of variance was applied. An increase in EI after exercise was observed in both groups, predominantly at higher shear stress values, indicating enhanced erythrocyte deformability under conditions of increased shear forces. However, the magnitude of post-exertion changes differed between groups. At lower shear stress levels (0.30 Pa and 0.58 Pa), EI tended to decrease after exercise. These findings indicate that a single bout of physical effort influences erythrocyte deformability, while the potential effects of cold exposure on this response remain uncertain and warrant further investigation.

1. Introduction

Erythrocytes are the most abundant morphotic component of blood and play a key role in transporting oxygen from the lungs to the tissues and carbon dioxide in the opposite direction. Their characteristic biconcave shape, lack of a cell nucleus, and flexible cell membrane enable free mobility, allowing red blood cells to pass even through capillaries with diameters comparable to their own size [1].

Erythrocyte deformability is regarded as one of the most important hemorheological properties of blood, as it enables efficient microcirculatory flow and ensures adequate oxygen delivery to peripheral tissues. The significance of this property becomes particularly evident under conditions of increased metabolic demand, such as during physical exertion [2,3,4]. When the vascular lumen is narrowed, erythrocytes must undergo reversible shape changes to preserve continuous blood flow without incurring structural damage, after which they return to their original morphology.

Erythrocyte deformability is determined by multiple interrelated factors, including membrane composition and fluidity, cytoplasmic viscosity, hemoglobin concentration, and intracellular enzymatic activity. Disturbances in any of these determinants may reduce red blood cell elasticity, impair capillary perfusion, and ultimately contribute to tissue hypoxia [4]. Under physiological conditions, the organism maintains erythrocyte deformability within an optimal range; however, this balance may be disrupted by oxidative stress, inflammatory processes, chronic diseases, and exposure to extreme environmental conditions, such as low ambient temperature. An additional factor influencing erythrocyte deformability during physical exercise is the intracellular water content of red blood cells. Approximately 62% of erythrocyte volume consists of water, the majority of which is bound to intracellular macromolecules, while a smaller fraction (approximately 25%) remains as free water within the cell. The proportion of “bound” water is closely related to erythrocyte mechanical properties and oxygen transport capacity. During acute exercise, the total water content of erythrocytes generally remains unchanged or decreases slightly; however, the relative proportion of free water increases at the expense of “bound” water, a shift that has been associated with a transient reduction in erythrocyte deformability [5].

Conversely, moderate and adequately controlled stimuli, including physical exercise or cold exposure, may promote adaptive changes in blood rheology [6]. Exercise is an important stimulus for erythropoiesis [7] and elicits immediate hemorheological responses. A single bout of exercise typically results in transient hyperviscosity caused by fluid loss and hemoconcentration, accompanied by increased red blood cell aggregation, which initially impedes blood flow. Simultaneously, rapid compensatory mechanisms are activated, including enhanced erythrocyte deformability and alterations in aggregation behavior, thereby facilitating oxygen delivery and contributing to the development of long-term “hemorheological fitness” characterized by improved blood flow properties [8]. Regular physical activity has been shown to promote favorable hemorheological adaptations, including changes in erythrocyte aggregation, deformability, and blood fluidity, ultimately improving the efficiency of oxygen uptake, transport, and delivery to tissues [9,10]. In contrast, acute exercise is commonly associated with increased erythrocyte stiffness, elevated blood viscosity, and reduced deformability [11]. These alterations are largely attributed to shifts in body fluid balance, increased concentrations of circulating blood cells, and the accumulation of metabolic by-products [12].

Given the central role of erythrocytes in systemic homeostasis, erythrocyte deformability is considered an important diagnostic and prognostic indicator in sports medicine, physiotherapy, and cardiovascular disease prevention. Although rheological adaptations to repeated or prolonged physical and thermal stress have been widely investigated, the effects of a single, acute bout of exercise performed under cold conditions remain poorly characterized. Recent advances in biomedical and analytical research have also highlighted the growing importance of highly sensitive and precise biosensing approaches for the assessment of blood-related parameters and cellular properties, underscoring the continuous development of methodologies used in blood analysis [13].

The present study aimed to investigate the effect of a single bout of physical exercise performed at a reduced ambient temperature of −10 °C in a thermal climate chamber on erythrocyte deformability in young men.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Group Characteristics

The study group consisted of 30 healthy men, physiotherapy students at the University of Physical Culture in Krakow (Poland). Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental or control group using simple randomization with a 1:1 allocation ratio. The randomization sequence was generated prior to the study, and group assignment was performed before the first blood sampling. No stratification factors were applied.

The experimental group underwent physical exertion under low-temperature conditions. The exercise was held in a thermal climate chamber in the Laboratory for Climate Technology Research and Heavy Duty Machines, Cracow University of Technology (Krakow, Poland), at a temperature of −10 °C. The thermal climate chamber possesses an accreditation certificate No. AB 1678 was issued by the Polish Centre for Accreditation and meets the requirements of the PN-EN ISO/IEC 17025:2005 standard. The Laboratory for Climate Technology Research and Heavy Duty Machines is a research center accredited in the field of defense and security by the Minister of National Defence (accreditation No.: 55/MON/2018). The control group performed the same workout but in thermoneutral conditions, in the open air; on the day of the experiment, the air temperature was 18.1 °C.

The study comprised 3 stages. Firstly, blood samples were collected from all participants before the exercise. The blood collection was performed in the morning hours at the Blood Physiology Laboratory of the Central Research and Development Laboratory, University of Physical Culture in Krakow, on 11 May 2024. Subsequently, both groups proceeded to perform an exertion test. After the exercise, blood samples were taken from all study participants.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Regional Medical Chamber in Kraków, Poland (approval No. 171/KBL/OIL/2023, dated 20 July 2023).

2.2. Research Method

The study employed a two-factor experimental design with repeated measures, with ambient temperature (low vs. thermoneutral) as the between-subject factor and time of measurement (pre- and post-exercise) as the within-subject factor. The study was designed as an exploratory investigation. The group allocation of the participants followed the principle of double randomization.

In experimental research, a phenomenon is deliberately induced by the researcher. Its course is observed in a planned and controlled manner, which allows for assessing the influence of specific factors on the parameters under study. On the basis of the identified relationships, conclusions are drawn and their accuracy is assessed with a specified probability. This study adopted a significance level of α = 0.05, which corresponds to a 95% confidence level.

2.3. Parallel Group Technique

As presented in Figure 1, the subjects were randomly assigned to 2 different groups (experimental and control) in accordance with the double randomization principle. The first measurement was conducted before introducing the experimental factor.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the parallel group technique.

Both groups were observed, with only the experimental group receiving the additional stimulus of low temperature (experimental factor). Subsequently, a second measurement was carried out to assess the changes influenced by the intervention.

The incorporation of a control group made it possible to assess whether the observed changes in red cell deformability resulted from the experimental factor and not from other, uncontrolled variables. Confounding variables, although not considered essential in the main analysis, can influence the study results and distort the true picture of effects.

While the experimental factor was defined as exposure to low ambient temperature, the two groups differed in their testing environments, as the experimental group performed the exercise in a controlled climatic chamber, whereas the control group exercised under natural outdoor conditions. These environmental differences were considered in the interpretation of the results.

2.4. Shuttle Run Test

In the study, an endurance shuttle run test was used (Figure 2) to determine cardiorespiratory capacity. The test started with a steady pace of 8 km/h. Then, the running speed increased by 0.5 km/h every minute. The participants ran a 20 m section back and forth, touching the finish line with one foot. The running was executed at a set pace, indicated by a beep. The subject completed the test if they did not reach the line at a distance of at least 3 m before the beep sound for 2 consecutive running sections. The test result was the number of completed sections [14]. The shuttle run test is a standardized, incremental protocol commonly used to induce progressively increasing cardiorespiratory load. Although direct physiological indicators of exercise intensity were not recorded, the same test protocol was applied in both groups to ensure comparable external workload progression.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the shuttle run test.

2.5. Blood Analysis Methods

Fasting blood samples were collected in the morning hours by a qualified nurse, under the supervision of staff at the Blood Physiology Laboratory of the Central Research and Development Laboratory, University of Physical Culture in Krakow. The blood was taken from each participant’s anterior ulnar vein into Vacuette EDTA K2 tubes.

2.6. Determining the Red Blood Cell Elongation Index

Erythrocyte deformability was assessed by using the elongation index (EI) in accordance with the method described by Hardeman [15]. A Laser-Assisted Optical Rotational Red Cell Analyzer (Lorrca) (MaxSis Lorrca®, RR Mechatronics, Zwaag, The Netherlands) was applied. Mean EI values were determined at the shear stress values of 0.30 Pa, 0.58 Pa, 1.13 Pa, 2.19 Pa, 4.24 Pa, 8.23 Pa, 15.95 Pa, 30.94 Pa, and 60.00 Pa, with the automatic analysis function of the Lorrca system, which allows assessing erythrocyte deformability as a function of shear stress. The analysis was performed by following the Hardeman method [15] and the results are presented as red cell EI values.

2.7. Statistical Analysis Methods

Data were collected in an MS Excel spreadsheet. This software was used to produce some of the graphs and all the tables. Statistical calculations were performed with the specialist Statistica software, version 13.1 (StatSoft Polska, Kraków, Poland).

The study employed a two-factor experiment with repeated measures. Each factor had 2 levels. The study group was divided into 2 subgroups and observed under 2 different conditions. The second factor was the measurement before and after the exertion test. The variability of observations was defined in the same way as in the one-way analysis of variance.

The control group was incorporated to demonstrate the actual effect of the experimental factor in the experimental group. A two-factor analysis of variance with repeated measures was used to analyze the results.

The following assumptions of analysis of variance with repeated measures were tested:

- The dependent variable can be placed on at least an interval scale.

- The distributions of the dependent variables do not deviate from normal.

- The individual groups have equal variance.

- The measurements are not correlated with one another.

To verify the assumptions of the analysis of variance, first, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied with the aim of examining the normality of the distribution. The homogeneity of the variance was checked by using several tests: Cochran’s C test, Hartley’s test, Bartlett’s test, and Levene’s test. The similar number of cases in the compared groups strengthens the F-test enough to make it robust to minor violations of the assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance.

After checking the main effects of the analysis of variance and concluding the significance of the F-test, which examined the hypothesis of differences between group means, a multiple comparison procedure was performed with the Bonferroni method. The association of variables was investigated by using a non-parametric Spearman rank correlation test. Separate two-factor repeated-measures analyses of variance were performed for each of the nine shear stress levels analyzed. Where significant main effects were identified, post hoc comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni correction. Owing to the number of outcome variables and the sample size, the statistical analyses were interpreted with an exploratory perspective, with effect sizes reported alongside p-values. Sample size calculation was performed for the primary endpoint defined as the group-by-time (time × group) interaction for erythrocyte elongation index (EI) measured at a shear stress of 15.95 Pa (ΔEI post–pre compared between groups). The calculation assumed a 2 × 2 mixed repeated-measures design (between-subject factor: temperature condition; within-subject factor: time), a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05, and 80% power. Based on pilot data and previous literature, an interaction effect size in the moderate-to-large range was expected. Under these assumptions, a total sample size of 30 participants (15 per group) was considered sufficient to detect meaningful group-by-time interaction effects.

3. Results

First, the basic assumptions of the analysis of variance were verified. All baseline measurements were obtained prior to the experimental intervention and therefore reflect interindividual variability resulting from random allocation rather than experimental effects.

Statistically significant effects were interpreted together with effect size estimates to describe response patterns rather than to draw definitive causal conclusions. Detailed results of the repeated-measures ANOVA and post hoc comparisons for individual shear stress levels below 15 Pa are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1 presents the results of the Shapiro–Wilk W-test for normality of distribution. Only in a few cases were there slight deviations observed. Such minor violations of the assumption of normality of distribution could be disregarded; it was therefore possible to proceed to the next stages of the analysis.

Table 1.

Shapiro–Wilk test results in the study groups in measurements before and after the exertion test.

Table 2 presents the test base for homogeneity of variance in the study groups. Only in one case was there a disagreement of the dispersion measure around the compared means. In the remaining cases, all tests confirmed that the assumption of homogeneity of variance was met. For the subsequent stages of the analysis, the approach taken was that the F-test was robust to different variances if the study groups were close to equal.

Table 2.

Results of tests investigating homogeneity of variance for the analyzed groups.

Table 3 presents all effects of the analysis of variance for EI at a shear stress of 15.95 Pa. An extremely significant (p < 0.001) effect of the measurement factor was observed, suggesting marked changes after the physical effort as compared with baseline in both groups. Also, the group factor turned out highly significant (p = 0.006), which denotes a different response to the running test under different temperature conditions. Moreover, a highly significant (p = 0.005) effect of the interaction of the measurement factor and the group factor was identified. To account for baseline differences in erythrocyte deformability between groups, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed using pre-exercise EI values as covariates. The adjusted post-exercise group comparisons did not reveal consistent between-group differences, and the results are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

Table 3.

All effects of the analysis of variance for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 15.95 Pa.

The results of the multiple comparison test provided in Table 4 indicate a statistically significant difference in the measurements before and after the exertion test in both the control and the experimental group. Furthermore, a significant difference was observed between the study groups before the run. No between-group difference was identified after the exertion test.

Table 4.

Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 15.95 Pa.

Table 5 presents all effects of the analysis of variance for EI at a shear stress of 30.94 Pa. An extremely significant (p < 0.001) effect of the measurement factor was observed, suggesting marked changes after the physical effort as compared with baseline in both groups. Also, the interaction of the measurement factor and the group factor turned out statistically significant (p = 0.035). The different responses to the physical effort in the study groups drew attention to the effect of the experimental factor. No statistical significance was found for the group factor.

Table 5.

All effects of the analysis of variance for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 30.94 Pa.

The results of the multiple comparison test provided in Table 6 indicate a statistically significant difference in the measurements before and after the exertion test in both the control and the experimental group. Furthermore, a significant difference was observed between the study groups before the run. No between-group difference was identified after the exertion test.

Table 6.

Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of EI 30.94 Pa.

Table 7 presents all effects of the analysis of variance for EI at a shear stress of 60.00 Pa. An extremely significant (p < 0.001) effect of the measurement factor was observed, suggesting marked changes after the physical effort as compared with baseline in both groups. No statistically significant effect of group assignment or of the interaction of the measurement factor and the group factor was identified.

Table 7.

All effects of the analysis of variance for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 60.00 Pa.

The results of the multiple comparison test provided in Table 8 indicate a statistically significant difference in the measurements before and after the exertion test in both the control and the experimental group. No difference was observed between the groups for either measurement.

Table 8.

Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 60.00 Pa.

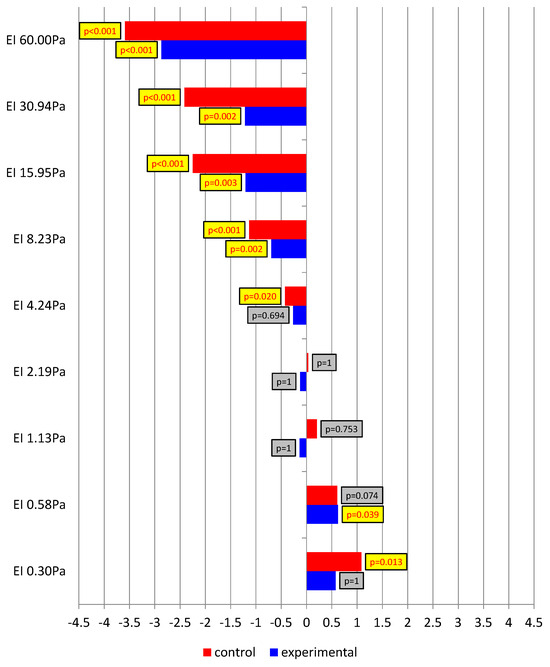

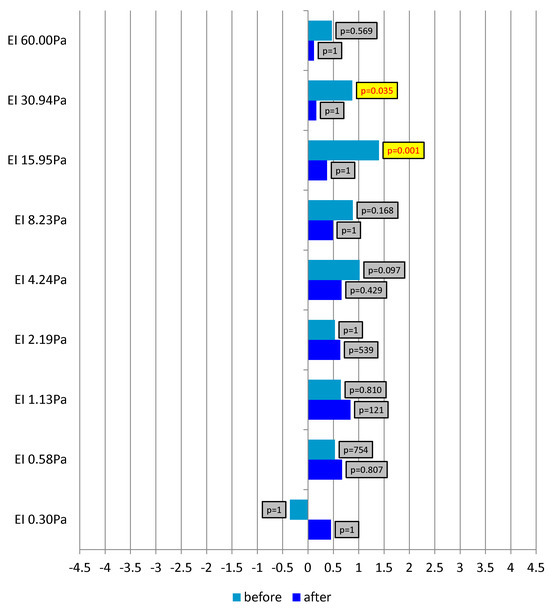

Figure 3 presents the Rosnow and Rosenthal d-index for differences between pre- and post-exertion measurements in both study groups. Positive values were associated with a reduction in EI after the running test. In turn, negative values of the index indicated an increase in EI after the completed run. With low shear forces, a decrease in erythrocyte elongation was observed in both groups, especially at a shear stress of 0.30 Pa in the control group and of 0.58 Pa in the experimental group, where the effect—large and medium, respectively—turned out statistically significant. From a value of 4.24 Pa in the control group and 8.23 Pa in the experimental group, further towards the highest shear forces (up to 60.00 Pa), EI clearly increased after the physical effort. A medium effect and, in the vast majority of cases, a large effect were identified, with very low levels of test probability.

Figure 3.

The Rosnow and Rosenthal d-index for differences between pre- and post-exertion measurements in the study groups.

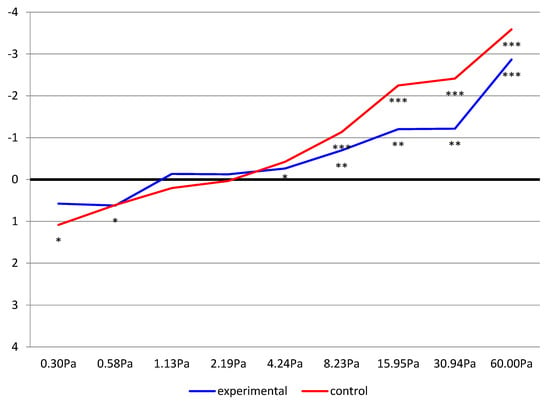

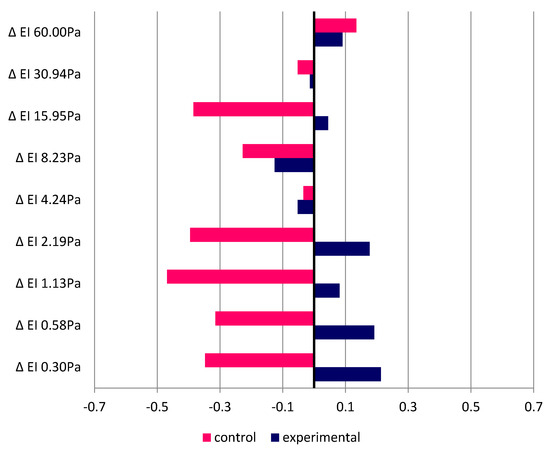

Figure 4 presents the Rosnow and Rosenthal d-index for differences between pre- and post-exertion measurements in both study groups, with the levels of statistical significance to highlight the most important effects. The representation of the data in the form of a polygonal chain reflects the profiles of EI changes as a function of the particular shear force values selected. This allowed us to demonstrate the differences between the control and experimental groups and confirmed the analyses performed in the study.

Figure 4.

The dynamics of changes in the Rosnow and Rosenthal d-index for differences between pre- and post-exertion measurements, including the level of statistical significance (* p ≤ 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001) in the study groups.

Figure 5 presents the Rosnow and Rosenthal d-index for differences between the experimental and control groups in pre- and post-exertion measurements. Clear differences were evident at higher shear forces. Before the exertion test was undertaken, the control group showed considerably higher values than the experimental group. In the baseline measurement, a statistically significant large effect of the between-group difference was observed. In the individuals who undertook the running test at a reduced air temperature, EI at shear forces of 15.95 and 30.94 Pa was significantly greater than in those not subjected to the experimental factor. In contrast, in the post-exertion measurement, no differences were found between the groups. These comparisons indicated the effect of the experimental factor. Greater changes in the analyzed rheological indicator occurred in the control group. Low temperature during the running test was associated with a smaller increase in erythrocyte EI as compared with thermoneutral conditions.

Figure 5.

The Rosnow and Rosenthal d-index for differences between the study groups (experimental and control) in pre- and post-exertion measurements.

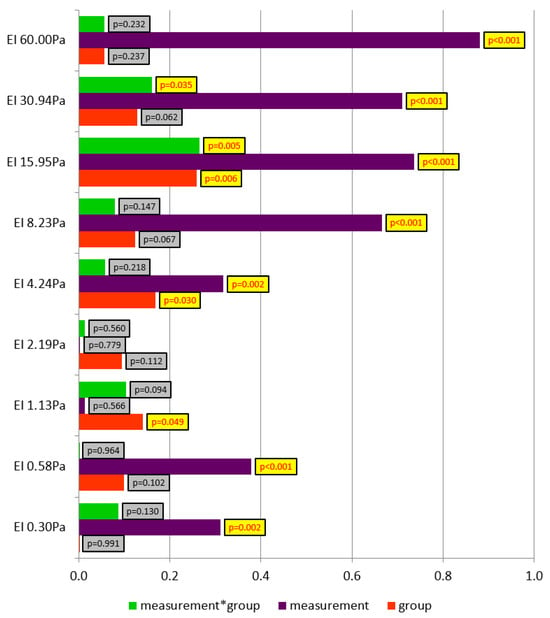

Figure 6 presents partial eta-squared values for the analyzed factors, including the levels of test probability. The dependent variable was explained the most by measurement repetition. In the majority of cases, the measurement factor proved to be highly or extremely statistically significant. A large effect was observed at higher shear forces. Partial eta-squared above 50% was identified for measurements at shear forces in the range of 8.23–60.00 Pa. The conducted running test significantly changed EI in both study groups.

Figure 6.

Partial eta-squared values for the analyzed factors, including the levels of test probability.

A small but statistically significant effect was observed for the group factor at shear forces of 1.13, 8.23, and 15.95 Pa. At these shear stress levels, differences in EI were reported between the control and experimental groups.

At higher shear forces, those of 15.95 and 30.94 Pa, a significant effect of the interaction of the group factor and the measurement factor was identified. A small but statistically significant effect was observed, and the indicators explaining the dependent variable equalled 27% and 16%, respectively. In this case, the effect of the experimental factor was demonstrated. The low temperature during the running test in the experimental group and the thermoneutral conditions in the control group significantly affected post-exertion erythrocyte deformability.

Table 9 shows the magnitudes of the determination coefficients. The highest level of fit was observed in the pre-exertion measurement at a shear stress of 15.95 Pa. In this case, the determination coefficient accounting for the number of measurements taken, i.e., the adjusted R2, equalled 0.32. In the remaining statistically significant cases, the level at which the studied factors explained the magnitude of the erythrocyte deformability indicators fell within the range of 13–19%.

Table 9.

Level of fit of the regression model to the variable values.

Figure 7 illustrates the Spearman rank correlation coefficient values for the examined relationships. The magnitude of post-exertion changes in EI as compared with the resting measurement was related to the running test duration. No statistically significant correlations were found. However, it was observed that shorter running time was associated with greater changes in erythrocyte deformability in the control group. Correlation coefficients close to the assumed significance level within the range of 0.3–0.5 were reported for the participants running in thermoneutral conditions at low shear stress values. In the experimental group, in turn, the opposite trend was noted. The small and statistically insignificant positive correlation indicates that greater changes in erythrocyte deformability occurred with longer running times at low air temperature.

Figure 7.

Spearman correlation coefficients between running duration and change in elongation index values.

Table 10 presents the mean (±SD) values of the erythrocyte elongation index measured before and after exercise in the experimental and control groups across all analyzed shear stress levels.

Table 10.

Elongation index in pre- and post-exertion measurements in the study groups.

4. Discussion

The assessment of the effects of cold on human body performance, and, in particular, on blood rheological properties, has become a subject of growing interest in the context of physiotherapy, sports medicine, and training. The observed increase in the popularity of such practices as cryotherapy and winter swimming, as well as the use of cold environments during training, has prompted a search for scientific evidence regarding the effectiveness of such interventions and their mechanisms of action. In this context, the study of erythrocyte deformability, which directly affects the efficiency of oxygen transport and microcirculation, is of particular importance.

Numerous adaptive hematological changes and improvements in blood rheological properties resulting from regular cold exposure have been described in the literature, but still, little is known about the effects of a single exposure combined with physical effort. Hence, the aim of the present study was to determine whether one-time exertion performed under conditions of reduced ambient temperature affected erythrocyte EI and whether this effect differed from the physiological response to the same exertion performed under thermoneutral conditions. Erythrocyte deformability was investigated in healthy, physically active men. The indicator of this property was EI, determined for different levels of shear stress. It was hypothesized that cold, as a physiological stress factor, could modify the body’s response to exercise, contributing to an improvement in blood rheological properties. However, the results demonstrated an ambiguous effect of cold on erythrocyte deformability, and the impact of the cold environment was not always in line with that expected.

The observed changes in erythrocyte deformability may be related to several physiological mechanisms described in the literature. Acute physical exercise has been shown to influence erythrocyte membrane fluidity, cytoskeletal protein organization, and nitric oxide–dependent signaling pathways, all of which contribute to red blood cell deformability [2]. Increased shear stress during exercise may stimulate nitric oxide synthase activity in erythrocytes, leading to improved membrane flexibility and enhanced microcirculatory flow [3].

Exposure to low ambient temperature may additionally modify these mechanisms through sympathetic nervous system activation, peripheral vasoconstriction, and alterations in oxidative stress balance. Cold-induced changes in membrane lipid phase behavior and transient increases in plasma viscosity have also been reported. However, the direction and magnitude of these effects appear to depend on the duration, intensity, and repetition of cold exposure [6].

The data analysis revealed that one-time exertion influenced red blood cell EI in both study groups (experimental and control), but with different magnitudes. In the measurement at the lowest shear stress (0.30 Pa), a decrease in post-exertion EI values was observed in both groups, with the change being statistically significant only in the control group. This may indicate the initial effect of mechanical and metabolic stress on erythrocytes, which leads to a reduction in their elasticity in the first minutes after exercise. However, it is worth emphasizing that such a reaction may be temporary and does not necessarily reflect a negative impact of effort. Red blood cells are subject to dynamic adaptive processes and their deformability can change over short periods under the influence of many factors, including temperature, pH, electrolyte levels, and oxidative stress [16].

For shear stress values of 0.58 and 1.13 Pa, differences were noted between the groups, but these were not always statistically significant. It is noteworthy that in the experimental group, EI at 0.58 Pa increased after exercise, suggesting that low temperature may, under certain conditions, promote improved erythrocyte deformability. This increase may indicate a beneficial impact of low temperature on the elasticity of erythrocyte cell membranes. This is in line with studies showing that cold can induce adaptive responses which promote improved blood rheology by reducing plasma viscosity and increasing membrane fluidity [17].

A similar trend was maintained in measurements at higher shear force values (2.19–60.00 Pa). In both the control and experimental groups, EI increased after the physical effort, indicating the activation of mechanisms that improve erythrocyte deformability. This response may result from increased blood flow, vasodilation, and vascular endothelial activation, which improve perfusion and blood cell elasticity.

The most pronounced effects of the experimental factor were noticed at shear stress values of 15.95 and 30.94 Pa, where a significant interaction between the factors of group and measurement occurred. This means that the effect of physical effort on EI varied with temperature conditions: cold modified the haemorheological response. Paradoxically, however, a greater increase in EI after exercise was found in the control group than in the experimental group, which suggests that the low temperature may have limited the full development of the adaptive response in such a short time.

In the final measurement (at 60.00 Pa), both groups demonstrated a marked increase in post-exertion EI, with no difference between them. This may imply that at very high values of shear stress, mechanisms that improve erythrocyte deformability dominate over the temperature effect, with the intensity and length of exercise playing a key role.

Taken together, these results indicate that one-time physical effort has a pronounced impact on erythrocyte deformability, but the effect of low temperature as a modifier of this response remains inconclusive.

A comparison of these results with the available scientific literature reveals both confirmations and significant differences from previous research on the effects of cold and exercise on blood rheological properties. The greatest consistency relates to the observed EI increase after exercise, particularly at higher shear stress values. A similar effect was reported by Baskurt et al. [5], who note that improved erythrocyte deformability is among the key hematological adaptations in individuals who regularly undertake physical effort.

The results of the present study are partly in line with previous reports. Teległów et al. [17] observed increased EI in males participating in regular winter swimming sessions. This effect was associated with both an improvement in cell membrane fluidity and a reduction in free radical levels owing to increased antioxidant enzyme activity. Banfi et al. [4] made similar observations when examining professional athletes undergoing whole-body cryotherapy.

However, it should be emphasized that most of the referenced studies dealt with the effects of prolonged or repeated cold exposure, which distinguishes them from the characteristics of the present research, applying a single, brief thermal stimulus. These differences in research design may explain why the present study did not demonstrate unequivocally better effects in the experimental group, despite this being the original assumption.

In the context of the effects of cold on the human body, Korzonek-Szlacheta et al. [18] reported increased secretion of norepinephrine and cortisol in athletes undergoing cryotherapy. These changes may affect vascular tone and microcirculation, indirectly influencing erythrocyte deformability.

Janský et al. [19] and Srámek et al. [20] also described substantial changes in sympathetic and endocrine system activity in response to cold, indicating the complexity of the body’s response and the possible occurrence of both beneficial and stress-inducing effects. Research performed by Kameneva et al. [21] indicates that hypothermia and mechanical load can decrease erythrocyte deformability; this supports the hypothesis that cold can have an inconsistent effect, depending on the intensity and duration of the stimulus and on the condition of the human body. Similar observations were made by Lecklin et al. [22], who reported increased resistance in erythrocyte flow through microstructures at a reduced temperature.

Important data were provided by Mairbäurl [23], who demonstrated that acute physical effort activated the nitric oxide synthase pathway in erythrocytes, potentially improving their elasticity. In light of these results, the EI increase observed in the present study at higher shear forces may be due to a similar physiological mechanism.

It has also been highlighted in the literature that erythrocyte deformability is a variable dependent on hydration level, haematocrit, and oxygenation status of the body [23,24], which may explain the inconclusiveness of the present study results. In a study by Drygas et al. [25] concerning long-distance swimmers, significant changes in blood parameters after extreme effort were found. This may explain the increased erythrocyte deformability in the control group participants of the present study after the shuttle run test at neutral ambient temperature.

Differences between the results of the present study and those reported in the literature may result primarily from the duration of exposure and the nature of the stressor. In most studies, beneficial rheological effects were observed after a series of repeated exposures, whereas in the present study, a single exercise in cold conditions was applied. It is possible that the brief exposure to low temperature induced a temporary increase in plasma viscosity or peripheral vasoconstriction, which reduced erythrocyte deformability [20,26]. On the other hand, prolonged exercise duration may have partially counteracted this effect by stimulating the microcirculation and reducing blood cell aggregation [27,28]. The dissimilarity of responses at low and high shear stress values supports the thesis of a complex mechanism of rheological response. This response can be modulated by both the autonomic system and changes in blood osmolality and temperature [16,29].

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, the experimental and control groups performed the exercise under different environmental conditions (controlled climatic chamber vs. natural outdoor environment), which may have introduced confounding factors such as wind or humidity. Consequently, the observed effects cannot be attributed solely to ambient temperature. Secondly, direct physiological indicators of exercise intensity, such as heart rate, blood lactate concentration, and hydration status, were not recorded. Nevertheless, the same standardized, incremental exercise protocol was applied in both groups. Despite the stated limitations, the study constitutes an important step in assessing the haemorheological response to one-time physical and thermal stress for the body. It has been demonstrated that even a single physical effort can improve erythrocyte deformability at higher shear forces, which may have practical relevance in planning training in cold climates or under controlled hypothermia.

The use of cold as an adaptive stimulus is becoming increasingly popular in physiotherapy and sports medicine. Studies such as this one can help determine the optimal parameters for cold therapy and integrate physical exercise with low temperature exposure.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study partly confirm previous observations, but also highlight the need to further investigate the effect of one-time physical activity at low temperature on erythrocyte deformability. Cold, treated as a physiological stimulus, has the potential to stimulate beneficial changes in the cardiovascular system, improve blood rheology, and increase the efficiency of oxygen transport. However, one should bear in mind that not all body responses to cold are beneficial and further research is needed that would involve different populations, exposure duration, and stimulus repetition. In addition, most of the available studies have been conducted in small groups of participants. Therefore, there is an emerging need for research in larger populations to better understand the physiological changes occurring in the human body.

The present exploratory study demonstrated that a single bout of acute physical effort significantly influenced erythrocyte deformability in healthy young men, particularly at higher shear stress values. These changes were observed in both study groups, indicating that acute exercise itself is a major determinant of post-exertion erythrocyte deformability. The additional influence of performing exercise at low ambient temperature remained inconclusive. Although differences in response patterns between the groups were observed, a consistent beneficial effect of acute cold exposure was not demonstrated.

These findings suggest that potential adaptive improvements in erythrocyte deformability related to cold exposure may require repeated or prolonged stimulation. Future studies should involve larger sample sizes, controlled environmental conditions, and direct monitoring of physiological load to better elucidate the interaction between exercise and cold exposure.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010535/s1, Table S1: Adjusted post-exercise erythrocyte elongation index (EI) values obtained using analysis of covari-ance (ANCOVA); Table S2: All effects of the analysis of variance for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 0.30 Pa; Table S3: Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 0.30 Pa; Table S4: All efeects of the analysis of variance for the elingation index variable at a shear stress 0.58 Pa; Table S5: Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 0.58 Pa; Table S6: All effects of the analysis of variance for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 1.13 Pa; Table S7: Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress 1.13 Pa; Table S8: All effects of the analysis of variance for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 2.19 Pa; Table S9: Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 2.19 Pa; Table S10: All effects of the analysis of variance for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 4.24 Pa; Table S11: Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 4.24 Pa; Table S12: All effects of the analysis of variance for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 8.23 Pa; Table S13: Probability of multiple comparisons for the elongation index variable at a shear stress of 8.23 Pa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T., K.R. and J.P.; Methodology, A.T., K.R., J.P., J.M. and P.M.; Formal Analysis, K.R.; Data Curation, A.T., K.R., J.P., I.W., Z.D., A.C., and J.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.T. and I.W.; Writing—Review and Editing, A.T., I.W. and J.M.; Supervision, A.T., J.P., and K.R.; Project Administration, A.T.; Funding Acquisition, A.T. and P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded within the program of the Minister of Science under the name ‘Regional Excellence Initiative’ in the years 2024–2027, project number RID/SP/0027/2024/01, in the amount of PLN 4,053,904.00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Regional Medical Chamber in Krakow, Poland (approval No.: 171/KBL/OIL/2023) and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

A.T. wishes to thank Janusz Pobędza for the opportunity to complete an internship at the Laboratory for Climate Technology Research and Heavy Duty Machines, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Cracow University of Technology, which contributed to the creation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Maeda, N. Erythrocyte rheology in microcirculation. Jpn. J. Physiol. 1996, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teległów, A.; Mardyła, M.; Myszka, M.; Pałka, T.; Maciejczyk, M.; Bujas, P.; Mucha, D.; Ptaszek, B.; Marchewka, J. Effect of intermittent hypoxic training on selected biochemical indicators, blood rheological properties, and metabolic activity of erythrocytes in rowers. Biology 2022, 11, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilski, J.; Teległów, A.; Pokorski, J.; Nitecki, J.; Pokorska, J.; Nitecka, E.; Marchewka, A.; Dąbrowski, Z.; Marchewka, J. Effects of a meal on the hemorheologic responses to exercise in young males. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 862968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banfi, G.; Lombardi, G.; Colombini, A.; Melegati, G. Whole-body cryotherapy in athletes. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskurt, O.K.; Hardeman, M.R.; Rampling, M.W.; Meiselman, H.J. Handbook of Hemorheology and Hemodynamics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kulis, A.; Misiorek, A.; Marchewka, J.; Głodzik, J.; Teległów, A.; Dąbrowski, Z.; Marchewka, A. Effect of whole-body cryotherapy on the rheological parameters of blood in older women with spondyloarthrosis. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2017, 66, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, W.; Maassen, N.; Trost, F.; Böning, D. Training induced effects on blood volume, erythrocyte turnover and haemoglobin oxygen binding properties. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1988, 57, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.S.P.; Silva, I.S. Effects of physical exercise on blood rheology. Rev. ARACÊ 2025, 7, 8294–8303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, J.F. Exercise hemorheology as a three acts play with metabolic actors: Is it of clinical relevance? Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2002, 26, 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, J.F.; Khaled, S.; Raynaud, E.; Bouix, D.; Micallef, J.P.; Orsetti, A. The triphasic effects of exercise on blood rheology: Which relevance to physiology and pathophysiology? Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 1988, 19, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.C.; Doyle, M.P.; Appenzeller, O. Effects of endurance training and long distance running on blood viscosity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1991, 23, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, O.; Erman, A.; Muratli, S.; Bor-Kucukatay, M.; Baskurt, O.K. Time course of hemorheological alterations after heavy anaerobic exercise in untrained human subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 94, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Nehra, M.; Dilbaghi, N.; Chaudhary, G.R.; Kumar, S. Detection of Hg2+ Using a Dual-Mode Biosensing Probe Constructed Using Ratiometric Fluorescent Copper Nanoclusters@Zirconia Metal–Organic Framework/N-Methyl Mesoporphyrin IX and Colorimetry G-Quadruplex/Hemin Peroxidase-Mimicking G-Quadruplex DNAzyme. BME Front. 2024, 5, 0078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léger, L.; Gadoury, C. Validity of the 20 m shuttle run test with 1 min stages to predict VO2max in adults. Can. J. Sport Sci. 1989, 14, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hardeman, M.R.; Dobbe, J.G.; Ince, C. The Laser-assisted Optical Rotational Cell Analyzer (LORCA) as red blood cell aggregometer. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2001, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, J.W.; Degroot, D.W. Human endocrine responses to exercise-cold stress. In The Endocrine System in Sports and Exercise; Kraemer, W.J., Rogol, A.D., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 499–511. [Google Scholar]

- Teległów, A.; Konieczny, K.; Dobija, I.; Kuśmierczyk, J.; Tota, Ł.; Maciejczyk, M. Effect of regular winter swimming on blood morphological, rheological, and biochemical indicators and activity of antioxidant enzymes in males. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzonek-Szlacheta, I.; Wielkoszyński, T.; Stanek, A.; Świętochowska, E.; Karpe, J.; Sieroń, A. Effect of whole body cryotherapy on the levels of some hormones in professional soccer players. Endokrynol. Pol. 2007, 58, 27–32. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Janský, L.; Srámek, P.; Savĺiková, J.; Ulicný, B.; Janáková, H.; Horký, K. Change in sympathetic activity, cardiovascular functions and plasma hormone concentrations due to cold water immersion in men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1996, 74, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srámek, P.; Simecková, M.; Janský, L.; Savlíková, J.; Vybíral, S. Human physiological responses to immersion into water of different temperatures. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 81, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameneva, M.V.; Undar, A.; Antaki, J.F.; Watach, M.J.; Calhoon, J.H.; Borovetz, H.S. Decrease in red blood cell deformability caused by hypothermia, hemodilution, and mechanical stress: Factors related to cardiopulmonary bypass. ASAIO J. 1999, 45, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecklin, T.; Egginton, S.; Nash, G.B. Effect of temperature on the resistance of individual red blood cells to flow through capillary-sized apertures. Pflügers Arch. 1996, 432, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairbäurl, H. Red blood cells in sports: Effects of exercise and training on oxygen supply by red blood cells. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiga, T.; Maeda, N.; Kon, K. Erythrocyte rheology. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 1990, 10, 9–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drygas, W.; Rębowska, E.; Stępień, E.; Golański, J.; Kwaśniewska, M. Biochemical and hematological changes following the 120-km open-water marathon swim. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2014, 13, 632–637. [Google Scholar]

- Stocks, J.M.; Taylor, N.A.S.; Tipton, M.; Greenleaf, J.E. Human physiological responses to cold exposure. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2004, 75, 444–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, E.; Daburger, L.; Saradeth, T. The kinetics of blood rheology during and after prolonged standardized exercise. Clin. Hemorhel. Microcirc. 1991, 11, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelaere, P.; Brasseur, M.; Quirion, A.; Leclercq, R.; Laurencelle, L.; Bekaert, S. Hematological variations at rest and during maximal and submaximal exercise in a cold (0 °C) environment. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1990, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selleri, V.; Mattioli, M.; Lo Tartaro, D.; Paolini, A.; Zanini, G.; De Gaetano, A.; D’Alisera, R.; Roli, L.; Melegari, A.; Maietta, P.; et al. Innate immunity changes in soccer players after whole-body cryotherapy. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.