Abstract

The textile sector provides essential goods, yet it remains environmentally and socially intensive, driven by high water use, pesticide dependent monocropping, chemical pollution during processing, and growing waste streams. This review examines credible pathways to sustainability by integrating emerging plant-based fibres from hemp, abaca, stinging nettle, and pineapple leaf fibre. These underutilised crops combine favourable agronomic profiles with competitive mechanical performance and are gaining momentum as the demand for demonstrably sustainable textiles increases. However, conventional fibre identification methods, including microscopy and spectroscopy, often lose reliability after wet processing and in blended fabrics, creating opportunities for mislabelling, greenwashing, and weak certification. We synthesise how advanced molecular approaches, including DNA fingerprinting, species-specific assays, and metagenomic tools, can support the authentication of fibre identity and provenance and enable linkage to Digital Product Passports. We also critically assess environmental Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and social assessment frameworks, including S-LCA and SO-LCA, as complementary methodologies to quantify climate burden, water use, labour conditions, and supply chain risks. We argue that aligning fibre innovation with molecular traceability and harmonised life cycle evidence is essential to replace generic sustainability claims with verifiable metrics, strengthen policy and certification, and accelerate transparent, circular, and socially responsible textile value chains. Key research priorities include validated marker panels and reference libraries for non-cotton fibres, expanded region-specific LCA inventories and end-of-life scenarios, scalable fibre-to-fibre recycling routes, and practical operationalisation of SO-LCA across diverse enterprises.

1. Introduction

The textile industry employs tens of millions of people worldwide and serves as a crucial provider of basic daily human needs [1]. While it contributes positively to the economy, it is also known for its significant environmental and social challenges in terms of long-term sustainability [2]. Textile businesses heavily rely on resources such as water, fuel, and chemicals [1], consuming more than three trillion gallons of freshwater annually, contributing over 10% of global carbon emissions, and generating around 92 million tonnes of waste each year [3]. In 2020, the European Union (EU) alone generated approximately 6.95 million tonnes of textile waste, averaging about 16 kg per person. Of this, only 27.5% was collected separately for reuse and recycling, while the large majority ended up in mixed household waste [4]. Of the total waste, 82% was post-consumer, while 18% originated from production or unsold textiles, with dyeing and finishing process accounting for nearly one-third of all chemical releases linked to the sector [2].

In response, efforts to reduce the textile industry’s environmental footprint have intensified, including the increased use of organic and recycled materials, improved water stewardship, and the adoption of circular economy models. However, alongside the uptake of more sustainable natural fibres, meaningful impact reduction will also require measures that curb overall consumption and strengthen end-of-life management [5]. Raising textile recycling rates and improving resource efficiency are, therefore, critical priorities. Integrating recycling into fibre and fabric production, designing for durability and recyclability, and encouraging more responsible consumption patterns can collectively reduce pollution and resource depletion in line with circular economy principles [6]. This transition not only lowers the industry’ environmental footprint but also supports alignment with broader sustainability commitments, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly human health (SDG 3), clean water (SDG 6), responsible production and consumption (SDG 12), climate change adaptation (SDG 13), and the sustainable management of water and land resources (SDG 14 and SDG 15) [7].

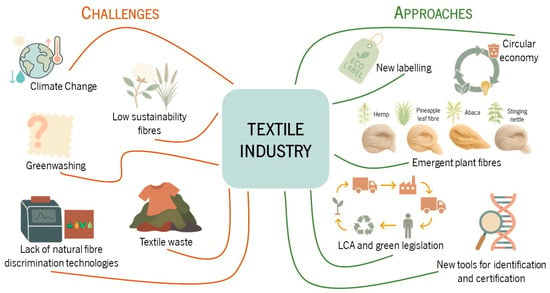

Around half of the global fabric consumption is attributed to natural fibres [8] such as cotton, wool, linen, viscose (bamboo), and hemp [3]. Cotton dominates this market, accounting for 80% of global natural fibre usage and one-third of the overall global fibre demand [9]. Despite being a natural material, cotton production raises significant environmental and human health concerns [10], as it is one of the most pesticide- and herbicide-intensive crops [11]. Organic cotton cultivation reduces some of these impacts by limiting the use of chemical inputs and adopting practices such as crop rotation and composting [12]; yet, it is generally more labour-intensive, has lower yields, and results in higher production costs. Additionally, obtaining organic certification is a rigorous and expensive process, which can be a barrier for small-scale farmers. Consequently, interest is growing in alternative plant-based fibres that can diversify sourcing while maintaining functional performance. In this context, hemp, stinging nettle, abaca, and pineapple leaf fibre are increasingly recognised as promising options due to their favourable agronomic profiles, strong functional properties, and potential to support more sustainable and traceable textile value chains [13,14,15,16]. Figure 1 provides an overview of the key challenges currently affecting textile value chains.

Figure 1.

Overview of current challenges and emerging solutions in the textile industry. Key sustainability issues include climate change, fibre waste, greenwashing, and lack of fibre identification technologies. Solutions focus on innovative labelling, new plan-based fibres, circular economy strategies, and traceability tools.

In this context, this review brings together these aspects to provide a connected and comprehensive overview of the role of emerging fibres and molecular traceability in sustainable textile value chains. It begins by examining the influence of climate change on fibre production and the potential of alternative crops under changing environmental conditions. The discussion then shifts to the properties and applications of natural fibres, followed by an assessment of certification and traceability practices currently used in the industry. Subsequent sections explore molecular methods for fibre authentication, including genetic markers and DNA-based approaches, and analyse policy frameworks that promote transparency. The closing section considers how environmental and Social Life Cycle Assessment contribute to evaluating sustainability performance and supporting robust certification processes across textile value chains.

2. Natural Fibres in Textiles

Natural fibres, from plants or animals, have supported human societies for millennia. They are valued as textile raw materials for properties that benefit both people and the environment, and they are used across almost every economic sector, including as feedstocks for green products [17]. Their biodegradability, renewability, and generally lower environmental footprint make them meaningful contributors to the SDGs [7]. Across many sectors, natural fibres are gaining recognition for functional versatility and favourable environmental profiles. As textile inputs and as reinforcements in composites, they offer a sustainable alternative to synthetics. They are renewable, biodegradable, and often close to carbon neutral, with advantageous attributes such as low density, light weight, and cost effectiveness. Relative to synthetic fibres, they can reduce mechanical wear on processing equipment and are typically considered less harmful to the environment, although outcomes depend on fibre type and processing conditions [13,14,15,16].

Natural fibres are commonly classified by origin into plant, animal, and mineral categories. Among these, plant fibres, especially lignocellulosic fibres, are the most widely used in textiles and composites. Their main constituents include cellulose, lignin, hemicellulose, pectin, waxes, and water-soluble compounds [18]. Plant fibres are further grouped as primary fibres, such as hemp, jute, and kenaf, and secondary fibres, such as coir and pineapple, depending on whether they are the main product or a by-product of the crop [19]. Mechanical and physical performance depends largely on the proportions and distribution of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which vary across species and plant organs [20,21]. These compositional differences shape tensile strength, durability, flexibility, and moisture uptake [19].

Four principal plant fibre classes are currently recognised: bast fibres (hemp, flax, jute, kenaf, ramie, nettle), leaf fibres (abaca, pineapple, sisal), seed fibres (cotton, kapok), and fruit fibres (coir) [22,23,24,25]. Within this broad diversity, this review focuses on hemp, abaca, pineapple leaf fibre, and stinging nettle, because they jointly represent high potential plant fibres across two major classes, bast and leaf, spanning temperate and tropical agronomic systems. Industrially, they cover both established supply chains (abaca, pineapple) and rapidly expanding or reemerging value chains (hemp, nettle), making them relevant case studies for real world adoption barriers, while also benefitting from expanding genomic and marker resources, enabling the discussion of DNA-based authentication and traceability beyond cotton [26]. These crops often require fewer inputs of water, fertiliser, and pesticides than conventional crops such as cotton [27,28,29], representing promising alternatives to conventional cash crops such as cotton and flax, while also providing important income opportunities for marginalised communities [30,31,32]. Table 1 compares strengths, weaknesses, and principal applications of hemp, stinging nettle, abaca, and pineapple leaf fibre relative to cotton.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of the advantages, disadvantages, and main applications of hemp, nettle, abaca, and pineapple fibres relative to cotton.

Hemp, Cannabis sativa L., is a type of plant species primarily grown in Europe and Asia, reaching heights of 1.2 to 4.5 m with a diameter of 2 centimetres [48,49]. The bast fibres, located in the outer stem, are separated from the woody core via retting and decortication processes. Hemp is known for its tensile strength (550–900 MPa), favourable water absorption, UV resistance, and thermoregulation [50,51] and is used in ropes, textiles, garden mulch, building materials, and animal bedding [50,52,53]. Hemp cultivation can reduce production costs by up to 77% compared to cotton, owing to higher yields and lower input requirements. Hemp yields are 25–500% greater than cotton, while also sequestering high amounts of atmospheric CO2 and improving soil health through natural weed suppression and reduced pesticide use [35]. However, despite these advantages, hemp fibres are generally coarser and less soft than cotton, which can limit their application in fine apparel and necessitate blending or additional processing to improve texture [51].

In its turn, abaca (Musa textilis), is widely used in the textile industry due to its strength, durability, and resistance to saltwater damage [54]. It is an herbaceous plant species native to the Philippines [55] and thrives in tropical and humid conditions with an optimal temperature between 28 and 30 °C [56] and rainfall of more than 2000 mm per year [57]. Like hemp, abaca is a renewable resource with a short cultivation, making it suitable for sustainable fibre production [58]. Its tensile strength ranges from 700 to 980 MPa, among the highest of natural fibres, and it performs particularly well in saline and wet environments [59]. However, despite these mechanical advantages, abaca cultivation is geographically restricted to a few tropical regions and fibre extraction remains labour-intensive, which constrains scalability and industrial adoption [60].

Likewise, pineapple leaf fibre, derived from Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. has a naturally lustrous appearance and is valued for its strength and durability, supporting applications in clothing, home textiles, and technical products. Its multicellular lignocellulosic architecture underpins favourable mechanical behaviour, particularly when fibres are recovered through optimised mechanical or chemical extraction routes [61,62,63]. Because it is obtained from leaves that are typically discarded after harvest, pineapple leaf fibre aligns well with circular economy strategies by valorising agricultural residues and reducing waste streams [64,65]. Available assessments also suggest a lower water and carbon footprint than cotton under comparable assumptions [66,67]. However, reported tensile strength is relatively modest (170–220 MPa) compared with bast fibres such as hemp and abaca, which may necessitate blending or targeted processing to meet high-performance textile requirements [68].

Stinging nettle, Urtica dioica L., a historically underutilised bast fibre, has recently shown potential for industrial-scale production. It is widely distributed across temperate regions of Europe, Asia, Northern Africa, and North America [69,70,71], and typically thrives in moist, nitrogen-rich soils under partial shade, commonly occurring along forest margins, rivers, and roadsides [69,70,72,73]. The plant often reaches up to 2 m in height and its bast fibres have applications in textiles, bioplastics, and animal housing materials [71,74]. Nettle fibre is biodegradable and non-toxic and has been reported to be stiffer and stronger than linen, often requiring little or no irrigation and minimal chemical inputs under suitable cultivation conditions [37]. Reported tensile strength values (400–650 MPa) are comparable to flax, supporting its potential as a viable textile input [36]. Despite these advantages, wider adoption is still limited by constrained processing capacity and the absence of established large-scale cultivation and supply infrastructure. Addressing these bottlenecks, together with further agronomic and quality standardisation, will be essential for nettle to transition from niche production to broader textile manufacturing, particularly in climate-resilient and low-input fibre systems [73].

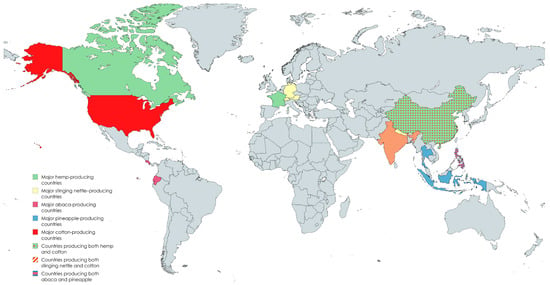

Overall, hemp, abaca, pineapple leaf fibre, and stinging nettle combine distinct mechanical strengths with favourable agronomic profiles and sustainability benefits, making them credible complements or alternatives to cotton. Still, key constraints remain, including the coarse handle of hemp, geographic and climatic limitations for abaca, processing intensity and associated costs for pineapple leaf fibre, and limited industrial-scale cultivation and processing infrastructure for nettle. Nevertheless, their generally lower input requirements, opportunities for circularity, and potential resilience under climatic stress support their relevance for more sustainable and transparent textile value chains. Beyond fibre morphology and functional performance, their global distribution and production patterns also matter because they shape socio-economic relevance, supply stability, and the logistical feasibility of scaling these materials. Figure 2 highlights the main producing countries of hemp, stinging nettle, abaca, pineapple leaf fibre, and cotton, illustrating the most important global regions for the production of these natural raw materials.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of major producing countries of hemp, stinging nettle, abaca, pineapple leaf fibre, and cotton. The map highlights key global regions relevant for the cultivation and production of these natural fibres [75,76].

Cotton remains the most widely produced fibre worldwide, with China, India, and the United States as the leading producers [76]. Hemp production is also led by China, with 107,403 tonnes harvested over 18,984 hectares in 2023 [76], while in the European Union, France accounts for over 60% of total hemp production, and Canada has shown increasing investment in hemp for textile and industrial purposes [77]. Although stinging nettle is produced on a smaller scale, it is cultivated primarily in Nepal, India, and European countries like Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. The Philippines dominates abaca production, contributing around 87% of global output, followed by Ecuador and Costa Rica [76]. Southeast Asia, especially Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines, leads in the production of pineapple, from which pineapple leaf fibre is derived, although official statistics for pineapple leaf fibre remain unavailable as the leaves are generally considered agricultural waste [78].

Compared with cotton, which typically moves through long and concentrated global supply chains, hemp, stinging nettle, abaca, and pineapple leaf fibre can support shorter and more resilient value chains rooted in regional cultivation and processing. These crops can generate local jobs in farming, decortication, and small-scale manufacturing, while advancing circularity by valorising products and residues, most notably pineapple leaves for fibre. In doing so, they cut transport-related emissions, retain more value within producer communities, and reduce exposure to climate-related disruptions. In fact, climate change affects the textile industry along the entire value chain, from raw material sourcing to manufacturing and logistics. Beyond rising temperatures, impacts include altered precipitation regimes, more frequent and severe storms, prolonged droughts, and a higher incidence of wildfires [79]. These pressures influence crop productivity as well as the availability, quality, and long-term viability of natural fibres. Many plant-based fibres, including cotton, jute, and flax, are climate-sensitive and depend on stable environmental conditions. Shifts in temperature and rainfall, together with extreme events, can depress yields, intensify pest and disease pressure, and reduce fibre quality. For example, drought stress can shorten fibre length and lower tensile strength, compromising mechanical performance [79]. Consequently, climate change threatens the reliability and sustainability of conventional fibre sources.

Although cotton is a renewable resource, its cultivation raises significant environmental concerns. Irrigated cotton requires large volumes of water [80] and its susceptibility to pests and diseases drives intensive pesticide and insecticide use [81]. Together, these pressures can contribute to soil degradation, contamination of water bodies, and reduced resilience under increasingly variable climates. As water scarcity intensifies, the sector faces growing pressure to reduce water demand and to prioritise fibres with lower intrinsic water requirements. In parallel, advancing water-efficient processing and diversifying raw material portfolios align with broader sustainability objectives and support SDGs 6 and 13 [7]. Identifying fibre crops that can tolerate suboptimal and shifting conditions is therefore an increasingly important priority.

Hemp is a leading candidate in this regard. It typically requires less irrigation than many conventional fibre crops [82,83,84,85] and provides favourable physical and mechanical performance, including high strength, good moisture management, ultraviolet resistance, and thermoregulatory behaviour, which together support diverse textile applications. Likewise, abaca combines high strength with flexibility, durability, and resistance to shrinkage and rot, and it performs well in saline and wet environments [39,86]. By prioritising resilient natural fibres and pairing them with water-saving practices, the textile industry can reduce climate risk and support a transition to more reliable and responsible production. This shift is particularly important given that cotton, while still the benchmark fibre by global production volume, carries substantial environmental burdens. Table 2 contrasts cotton with hemp, abaca, nettle, and pineapple across water use, pesticide intensity, average yield, and land use, reinforcing their potential as sustainable alternatives under changing environmental conditions.

Table 2.

Comparative sustainability indicators of select alternative fibres (hemp, nettle, abaca, and pineapple) and cotton, including water use, pesticide intensity, average yield, and land use.

Hemp, abaca, pineapple leaf fibre, and nettle generally require substantially fewer agricultural inputs than cotton, while achieving competitive yields under suitable conditions. These differences suggest that they could support more resilient and resource efficient textile value chains, particularly as climatic stress increases. However, despite encouraging signals from pilot studies and small-scale case analyses, key uncertainties remain regarding the agronomic stability across regions, economic competitiveness, and feasibility of integration into large-scale production systems. In the absence of robust industrial data, sustainability claims for these fibres are still difficult to substantiate and, in some cases, remain largely speculative [88].

Beyond agronomy and fibre performance, adoption also depends on verifiable identification. Several plant fibres share overlapping morphological features, and processing and finishing can obscure diagnostic traits, especially in blends. Reliable fibre authentication is therefore essential for transparent supply chains and credible claims, providing the rationale for the next section on current and emerging fibre identification methods.

3. Current Challenges in Certification and Traceability in Textiles

Consumer interest in ecofriendly products has increased steadily, alongside a growing demand for transparency about sustainability practices in textile manufacturing and supply chains [89]. In response, traceability has emerged as a key mechanism to communicate not only a product’s environmental profile, but also other tangible and intangible attributes valued by consumers, including the origin of raw materials, the processing history of individual components, and the product’s pathway through the supply chain [90,91,92]. When implemented credibly, traceability allows sustainability claims to be verified and therefore supports greater transparency and accountability. Yet, reliable identification of emerging alternative fibres remains challenging. Conventional approaches often depend on time-consuming and sometimes inconclusive morphological and biochemical assessments, which can lose diagnostic power after processing or in blended textiles [93,94,95].

Currently, fibre identification relies on a combination of morphological and physicochemical approaches, including optical and electron microscopy of longitudinal and transverse sections, near-infrared (NIR) and mid-infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, solubility and flame tests, tensile testing, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), with DNA genotyping used less frequently [96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107]. For more complex matrices such as fabrics and apparel, analysis typically focuses on longitudinal and transverse fibre sections examined by optical and electron microscopy [94]. While cotton often exhibits distinctive traits that support identification, distinguishing hemp, nettle, abaca, and pineapple leaf fibres from certain synthetic fibres can remain challenging because several physical and structural characteristics overlap across materials [108]. Chemical processing further complicates identification. Many fabrics and garments undergo wet processing steps during manufacture, including bleaching and dyeing. Although many natural fibres retain sufficient diagnostic features for optical or SEM and FTIR-based identification after common treatments, specific processes, such as mercerisation of cotton, chlorination of wool, degumming of silk, or aggressive bleaching of bast fibres, can alter key diagnostic traits to varying degrees, reducing the reliability of conventional methods. These technical constraints have important downstream consequences, because weak or uncertain fibre identification can be exploited to make sustainability claims that are difficult to verify.

Deceptive environmental claims exacerbate the methodological limitations outlined above by increasing information asymmetry between producers and consumers and by eroding the trust in sustainability information [109]. In this context, “greenwashing” can take several forms, including selective reporting of favourable indicators while omitting burdens elsewhere in the life cycle, vague or non-verifiable statements such as “ecofriendly”, claims that are irrelevant to the product’s actual impacts, and the use of imagery or labels that imply independent endorsement where none exists. In the textile sector, these practices often appear as broad assertions that products are made from environmentally preferable fibres or produced using sustainable methods, even when only a minor component or a single processing step meets those criteria [110].

A further source of distortion arises from fragmented, non-transparent, or weak certification and labelling schemes. Existing programmes vary widely in scope, performance thresholds, and audit rigour. Some verify management systems rather than measured product performance, others cover only a single production stage instead of cradle-to-gate or cradle-to-grave outcomes, and many do not ensure independent third-party verification across all tiers of the supply chain. Claims based on recycled content or preferred fibres may also rely on a chain of custody models such as mass balance or book and claim accounting, which complicates attribution at the individual product level. Moreover, inconsistent system boundaries, heterogeneous impact indicators, and the limited disclosure of data sources and quality reduce comparability across products and brands, constraining the usefulness of certification for procurement decisions and consumer choice [110].

Addressing these gaps requires clearer definitions of claim scope, standardised Life Cycle Assessment methods with explicitly declared system boundaries and impact categories, a robust chain of custody supported by independent verification, and disclosure practices that allow claims to be audited against primary data. Capacity building is also essential, both for producers to implement credible measurement and reporting systems and for consumers and institutional buyers to interpret sustainability information and prioritise demonstrably lower impact textiles [109,110]. Taken together, the limitations of conventional fibre identification and the variability of certification practice underscore the need for traceability systems that are robust, consistent, and independently verifiable. As supply chains become more complex and sustainability claims gain prominence in marketing and procurement, traceability must extend beyond documentation and incorporate analytical approaches that can authenticate materials with high specificity across multiple processing stages. In this context, molecular and marker-based tools are emerging as practical complements to conventional methods, supporting chain-of-custody verification and, in some cases, providing objective evidence of origin and material integrity.

4. Molecular-Based Approaches in Traceability

Molecular- and marker-based systems are increasingly used to verify the origin and integrity of plant-derived raw materials in textile supply chains, with cotton as the primary focus to date. Applied DNA Sciences uses synthetic DNA markers authenticated by a proprietary assay to mark materials for later verification: simple DNA markers, in which short synthetic DNA segments are applied to the product surface and detected by analysing the treated surface with scanners, and encapsulated DNA markers, in which synthetic DNA is embedded in a carrier medium to help the tag persist through processing steps [111,112]. Despite being used mainly for cotton, these approaches can strengthen the chain of custody and support authenticity checks when the tag is introduced early in the value chain. Other commercial providers couple molecular or physical markers with proprietary readout platforms. For instance, Oritain analyses stable isotope profiles to infer geographic origin from the isotopic composition of the product, while Haelixa applies encapsulated synthetic DNA that can be read at checkpoints to verify the continuity of supply [113]. On the other hand, FibreTrace embeds a luminescent physical pigment into raw fibres and links scans to a digital ledger, enabling real-time verification across processing and logistics. While FibreTrace shows strong potential in cotton supply chains, applications to other natural fibres such as hemp remain at the research and pilot stages.

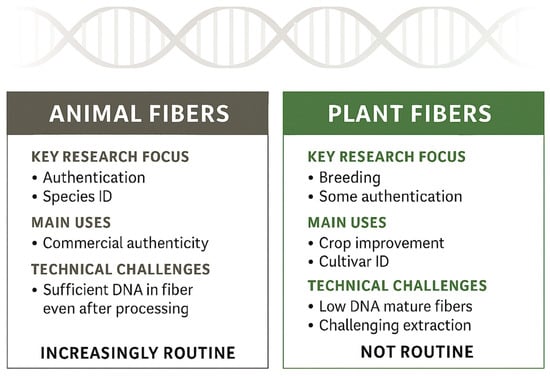

Despite their utility, tag-based systems do not allow retrospective identification of fibre type in unlabelled finished goods unless the marker was applied at the source. In addition, most platforms have been optimised for cotton, and protocols for hemp, nettle, abaca, and pineapple leaf fibre are still emerging. Also, untagged legacy or market samples cannot be authenticated with these tools, costs and intellectual property restrictions can limit adoption and interoperability, and chemical or thermal treatments may reduce recoverable DNA and assay sensitivity in some contexts [114,115]. For animal fibres, DNA-based methods are highly effective for identifying and authenticating textiles and commercial products [116,117]; however, DNA research in fibre crops such as cotton, flax, jute, hemp, and ramie has focused on plant genome sequencing, molecular markers, and genotyping for breeding, quality enhancement [118,119,120,121,122], and limited authentication applications (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

DNA-based authentication maturity in textiles, animal versus plant fibres.

Recent pilot projects illustrate how molecular and marker-based systems are being translated into operational textile supply chains. Haelixa, for example, partnered with C&A Modas S.A. (Sneek, The Netherlands) to tag organic cotton with synthetic DNA, enabling verification from fibre to the finished garment [123]. Similarly, Soorty Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. (Karachi, Pakistan) integrated DNA markers into denim production, in collaboration with Haelixa and Rieter, demonstrating scalability in an industrial setting [123]. Haelixa has also piloted encapsulated DNA markers in nettle fibres, indicating that molecular tagging can extend beyond cotton to less conventional plant fibres [123]. In parallel, Oritain has applied stable isotope profiling to support geographic origin claims for premium cotton, including Egyptian and US varieties [124]. FibreTrace has embedded luminescent pigments into cotton fibres and linked scan events to a digital ledger, enabling real-time verification across processing and logistics, with pilot applications in denim and knitwear [125]. Together, these initiatives signal growing industrial interest, but they also highlight persistent barriers to wider adoption. High costs for marker application and readout, variable compatibility with wet processing and finishing, limited interoperability across proprietary platforms, and the lack of validated protocols for non-cotton fibres remain key constraints. As a result, a verification gap persists for non-cotton plant fibres that are difficult to distinguish once processed, particularly in blends and heavily finished fabrics. Closing this gap will require fibre-specific analytical methods that remain robust after common wet processing, validation through cross laboratory studies, and open reference libraries to support reproducible interpretation. These advances should be coupled with digital traceability records that link molecular results to granular supply chain events from origin to finished product. In parallel, clearer certification protocols that mandate verifiable chain of custody and disclose methods are needed to deter greenwashing and align sustainability claims with auditable evidence [84,126,127].

4.1. Molecular Markers in Crop Improvement

Metagenomic studies of plant fibre processing systems show substantial potential, particularly as next generation sequencing (NGS) becomes increasingly accessible and cost-effective [128,129]. Metagenomics enables the analysis of genetic material from complex microbial mixtures associated with fibre-processing environments and substrates, providing a comprehensive view of community composition and functional capacity [130]. By sequencing DNA from these microbial communities, NGS-based workflows can identify enzymes and metabolic pathways involved in processes such as retting, degumming, and fibre modification, supporting the development of more efficient and potentially more sustainable fibre-processing strategies [131,132]. In parallel, molecular markers have become indispensable tools in plant improvement research. When combined with PCR, molecular markers enable the targeted amplification of specific genomic regions using custom designed or random oligonucleotide primers [133]. Earlier marker discovery often relied on restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) approaches, which had limited sensitivity and did not require sequencing data [134]. The availability of reference genomes and advanced NGS platforms has since expanded the marker toolbox to include microsatellites (simple sequence repeats, SSRs), insertion deletion (InDel) markers, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). For example, SSR markers have been developed using genomic resources from Cannabis species, and transcriptomic analyses across flax fibre development stages have supported the identification of candidate loci relevant to fibre quality improvement [122]. Similarly, genetic studies in paper mulberry have applied conventional DNA extraction and targeted multi-copy regions, including microsatellites and ITS-1, to support discrimination and characterisation [135].

With increased technological capacity and lower costs, PCR-mediated marker protocols are now widely used in plant genomics to characterise genetic diversity among varieties and to assess the outcomes of molecular breeding programmes [136,137,138]. These tools support the construction of genetic maps, accelerate breeding through marker-assisted selection, and improve the detection and quantification of genetic variation across diverse crop species, strengthening germplasm conservation and management [136,138,139,140,141,142,143]. Despite their maturity in crop improvement, however, these molecular marker approaches have been applied far more often to agronomic trait development than to the authentication and traceability of raw materials and derived products in textile value chains [144]. Table 3 contrasts leading platforms, including DNA barcoding, SSR markers, SNP genotyping, and PCR-based targeted identification, highlighting how each can be applied to textiles, together with key advantages and constraints.

Table 3.

Comparative overview of molecular traceability platforms applied to textiles, including DNA barcoding, SSR (Microsatellite) markers, SNP genotyping, and PCR-based target identification. The table outlines principles, advantages, limitations, and application in textiles to highlight the practical relevance for fibre authentication and supply chain transparency.

4.2. DNA Fingerprinting for Crop Identification

DNA fingerprinting operationalises molecular markers by reading distinctive sequence patterns, translating genomic variation into practical evidence for plant discrimination [149]. These genetic signatures can support species-level identification from small or partially degraded samples, and the method’s relative tolerance to many physical and chemical treatments makes it well suited to textile matrices, where fibres are often processed and blended [150]. As PCR workflows and DNA extraction kits have become more automated, DNA fingerprinting has become increasingly feasible for routine authentication and traceability in commercial contexts, enabling reliable signals to be recovered from limited material [145,148,151,152,153]. Accordingly, DNA-based approaches have been applied to product authentication and chain-of-custody verification, offering practical solutions for fibre discrimination challenges across textile supply chains [147,154,155,156]. Parallel advances in plant genome sequencing have further strengthened the foundation for fibre authentication. High-quality reference genomes improve understanding of gene function and the molecular basis of fibre development, enabling the identification of diagnostic loci that can remain detectable after common wet processing steps [118,122,157,158]. Next generation sequencing (NGS) has expanded access to these resources and has supported the generation of reference sequences for key fibre crops, including cotton, flax, jute, hemp, abaca, pineapple, and nettle [118,119,120,122,159,160,161,162]. This growing genomic infrastructure now underpins the development of species-specific and, in some cases, variety-specific assays relevant to traceability.

Species exemplars illustrate both readiness and opportunity. For instance, Cannabis sativa L., an herbaceous member of Cannabaceae, is diploid comprising nine autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes (X and Y) [163]. Fibre-type hemp and medicinal-type cannabis are distinguished by intended use and cannabinoid profiles: fibre-type plants contain less than 0.3% Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and relatively higher cannabidiolic acid, whereas medicinal-type plants exceed the 0.3% threshold [164]. Genomic studies show that THCA synthase and CBDA synthase share about 89% sequence identity and derive from the precursor cannabigerolic acid, providing candidate markers for regulatory compliance and fibre traceability in hemp-derived textiles [165,166,167,168]. For Musa textilis (abaca, a banana relative within Musaceae), recent genome assemblies, together with polymorphic markers developed across the Musa genus, offer useful targets for the molecular identification of abaca fibre in blended or finished textiles [169,170,171,172,173,174]. In Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. (pineapple), a perennial monocot of Bromeliaceae with a haploid genome and characteristic crassulacean acid metabolism, gene sets linked to fibre formation have been described and could underpin assays for pineapple leaf fibre authentication in supply chains [160,175,176,177,178]. In contrast, Urtica dioica L., a perennial in the Urticaceae, exhibits complex ploidy and cytotype variation across its range. Although genomic resources remain less developed than for major fibre crops, its emerging population genomic datasets provide a sound basis for future diagnostic marker development as reference resources improve [120,179,180]. Together, the maturing toolkit of DNA fingerprinting, PCR-based assays, and expanding reference genomes positions molecular analysis as a practical pillar for fibre authentication and traceability. These capabilities are especially relevant for non-cotton plant fibres such as hemp, abaca, pineapple leaf fibre, and nettle, where conventional methods struggle after intensive processing throughout the textile value chain. Table 4 summarises the genomic attributes of major fibre plants that are most relevant to DNA-based identification and traceability applications.

Table 4.

Genomic overview of Cannabis sativa L., Musa textilis, Ananas comosus, and Urtica dioica L. Abbreviations: CAM—crassulacean acid metabolism, CBDAS—cannabidiolic acid synthase, SSR—simple sequence repeat, SNP—single nucleotide polymorphism, spp.—multiple species, THCAS—tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase.

Although molecular approaches can strengthen the chain of custody and support authentication of fibre identity, traceability alone cannot demonstrate sustainability. Verification of origin must be paired with evidence of environmental and social performance across the life cycle, particularly because processing intensity, energy sources, and chemical inputs can dominate impacts even when the raw material is renewable. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) provide this analytical foundation, while ecolabeling schemes and the Digital Product Passport translate verified evidence into comparable and auditable information for markets and regulators. The next section therefore examines how these tools can substantiate sustainability claims for emerging natural fibres and how they interface with certification and policy instruments.

5. Policy Instruments for Textile Sustainability

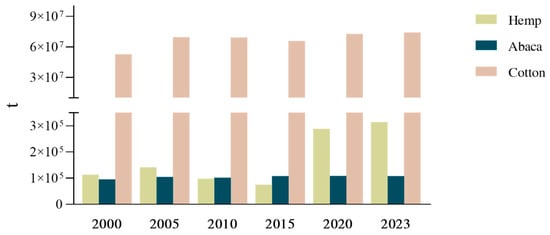

A primary legislative consideration for alternative plant fibres is the regulation of cultivation practices. Hemp is a clear example, as many jurisdictions maintain strict legal distinctions between industrial hemp and drug type cannabis, even though both derive from the same species, based largely on genotype-associated differences in tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content. Within the European Union (EU), hemp imports require an official licence, and raw hemp must contain no more than 0.3% THC. Hemp seeds for sowing must also be accompanied by documentation confirming that the THC content of the relevant variety does not exceed this threshold, while Member States may apply stricter national rules where deemed necessary [35,190]. By contrast, nettle, pineapple, and abaca are generally subject to less specific crop targeted legislation, although producers must still comply with broader agricultural and environmental requirements, including those governing pesticide and herbicide use, soil protection, and sustainable land management [37,39,191,192]. FAO data further suggest that legal clarity and market-enabling reforms can influence fibre crop deployment, with global hemp production increasing since 2015 (Figure 4), a trend broadly aligned with policy changes that relaxed cultivation restrictions in several countries [193]. In comparison, cotton has maintained consistently high productivity, whereas abaca yields remain more variable due to climatic sensitivity and region-specific cultivation constraints [194]. Together, these patterns highlight how regulation shapes not only market access, but also investment confidence and the feasibility of scaling alternative fibre crops.

Figure 4.

Evolution of world production (t) for hemp, abaca, and cotton between 2000 and 2023 [76].

5.1. International Regulatory Frameworks

Downstream of fibre production, regulatory attention shifts from cultivation to consumer safety, product quality, and supply chain transparency [195,196]. Textile manufacturing involves mechanical, chemical, and physicochemical operations that can introduce hazardous substances, including heavy metals, pesticide residues, and organic solvents. To reduce these risks and improve chemical stewardship, several widely used international frameworks and standards have been developed, including ZDHC (Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals), OEKO-TEX (International Association for Research and Testing in the Field of Textile and Leather Ecology), and GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard). Collectively, these initiatives establish requirements and verification procedures that aim to improve chemical safety and ecological compliance across the textile value chain [195,197].

In parallel, chemical governance has evolved substantially to strengthen the protection of human health and the environment. In the European Union, REACH (Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006), adopted in 2006, remains the core framework for the registration, evaluation, authorisation, and restriction of chemicals. Comparable regimes have been introduced elsewhere, including MEP Order 7 in China (2010) and KKDIK in Türkiye (2017). Building on REACH, the EU Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (2020) set longer-term objectives for safer chemicals and the reduction in harmful exposures through to 2050 [198,199]. More recently, the Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) and the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles [200] elevated textiles as a priority sector under the European Green Deal, with emphasis on safer design, improved circularity, and reduced pollution (adopted in 2022). These initiatives aim to eliminate hazardous substances in textiles by 2030 and promote sustainable design principles.

Legislation has also increasingly linked chemical safety to circularity outcomes. The Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) broadens the scope of ecodesign beyond energy-related products and enables requirements that address durability, reparability, recycled content, and substances that inhibit circularity [201], which expands upon the earlier Ecodesign Directive (2009/125/EC). In addition, waste policy has introduced stronger expectations for textile collection and management. Under the EU Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC), amended by Directive (EU) 2018/851, Member States are now required to establish separate collection for textiles, supporting reuse, preparation for reuse, and higher-quality recycling pathways [198,202]. Despite these advances, implementation and enforcement remain uneven across jurisdictions. Differences in policy strictness, monitoring capacity, and mutual recognition can create fragmented compliance landscapes, complicating sourcing and trade for globally operating textile companies and weakening the credibility and comparability of sustainability claims [203]. Overall, the regulatory trajectory is clear; chemical safety, circularity, and transparency are becoming central requirements rather than optional features in fibre and textile production.

5.2. Eco-Labelling and the Digital Product Passport

Eco-labelling and certification schemes are practical instruments for building trust in sustainable textiles, because they translate complex sustainability information into signals that can shape consumer perception and purchasing behaviour [204,205,206]. However, consumer confidence remains fragile, largely due to persistent scepticism about the credibility and consistency of sustainability claims within the fashion sector. To address these concerns, the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles, aligned with the European Green Deal, aims to strengthen and standardise approaches for assessing and communicating environmental performance in the textile sector [207]. In principle, eco-labels can guide consumers toward more responsible choices and encourage better product use practices. In practice, their effectiveness depends on clear scope, transparent criteria, and robust verification, since weak governance or selective reporting can enable greenwashing and undermine trust [208].

Certification uptake is also uneven. Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) frequently face barriers related to limited financial resources, insufficient technical capacity, and administrative burden, which can restrict participation and concentrate certified practices among larger firms with more resources. Evidence from recent studies highlights that SMEs often lack the funding, expertise, and institutional support needed to comply with complex certification frameworks, slowing diffusion across the sector and reinforcing the need for targeted support and capacity building so that eco-labelling can be inclusive and effective at scale [209].

A complementary and increasingly prominent tool is the Digital Product Passport (DPP), introduced under the EU Circular Economy Action Plan and the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) [210]. The DPP assigns a digital identity to products and can store information relevant to sustainability and circularity, including material composition, origin, reparability, recyclability, and selected environmental performance parameters, typically accessed via technologies such as QR codes [211]. By improving data availability and traceability, the DPP is expected to strengthen supply chain transparency and enable more systematic verification of sustainability claims. While implementation challenges remain, particularly regarding data governance and system interoperability, the DPP is expected to become mandatory for textiles between 2026 and 2027. In addition to recording composition and circularity attributes, DPP entries can incorporate molecular traceability outputs where available. DNA fingerprinting, species-specific markers, and metagenomic profiles can provide verifiable evidence of fibre identity and, in some contexts, geographic origin, which can be linked to DPP records through interoperable data systems. This linkage can strengthen claim credibility and reduce opportunities for mislabelling. However, implementation raises practical challenges, including data governance, interoperability across digital platforms, confidentiality, and the ability of SMEs and upstream suppliers to invest in the required infrastructure. Ensuring equitable adoption will therefore require harmonised data frameworks and capacity-building programmes that support suppliers across tiers, not only brand level compliance.

At the global level, the United Nations has reinforced its climate commitments through initiatives such as the Paris Agreement, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Global Alliance on Circular Economy and Resource Efficiency (GACERE), and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) [212]. The Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action, launched in 2018 and renewed in 2021, sets a target of net-zero emissions in the textile sector by 2050. Complementary efforts like the Ethical Fashion Initiative promote sustainability and social inclusion in emerging economies [213,214].

In 2018, the EU’s strategy “A Clean Planet for All” reaffirmed the urgency of climate action, aiming to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 and limit global temperature rise to 2 °C above pre-industrial levels [215]. As part of the Circular Economy Package, the Plan for Sustainable and Circular Textiles focuses primarily on the clothing sector, given its substantial contribution to textile consumption and waste [200]. This strategy aligns with the European Climate Law, the European Consensus on Development, the UN SDGs, and the Paris Agreement, forming a comprehensive legislative framework for sustainable textile transformation [201]. The strategy also promotes European textile self-sufficiency, emphasising energy and material efficiency, innovation, and competitiveness. In parallel, to mitigate social and environmental risks, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has developed due diligence guidelines for multinational enterprises in the garment and footwear sectors [216]. Industry-led initiatives such as the Fashion Pact, the Better Cotton Initiative, and the Cotton 2040 Initiative further support environmental sustainability and ethical sourcing in cotton production. Yet, for these frameworks to translate into credible claims and effective incentives, large-scale implementation of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and social assessment tools remain essential. By generating robust, evidence-based data, LCA and S-LCA can inform policy design, strengthen ecolabeling criteria, and improve the evidentiary basis of DPP, ensuring that sustainability claims are substantiated and that stakeholders can access transparent, auditable information across the textile value chain.

5.3. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment

The textile sector has a significant environmental burden, marked by intensive freshwater use, chemical emissions to air, water, and soil, and substantial solid waste generation [217]. Within this footprint, conventional cotton processing remains a critical hotspot for global warming potential and resource depletion, with dyeing and weaving stages contributing disproportionately to energy demand and chemical loads [218]. These upstream pressures are exacerbated by downstream consumption dynamics, wherein rapid fashion cycles, short product lifespans, and high purchase volumes increase landfill deposition, microplastic release, toxic leachate formation, and greenhouse gas emissions from decomposition or incineration [219]. As a strategy to mitigate these impacts, there has been an increase in the use of recycled fibres in textiles, with a survey suggesting that by 2025, over 30% of garments from half of Europe’s brands will be made with recycled fibres [220]. Although textile-to-textile recycling scenarios in Europe are projected to increase in by 2035, with potential reductions in climate impact and water deprivation [221], only 18–26% of textile waste is expected to feasibly be recycled fibre-to-fibre by 2030, leaving a 60–70% supply deficit relative to the expected market demand for recycled textiles [222]. This gap between Europe’s circularity aspirations and the sector’s reality is significant, especially given that 75% of EU textile imports come from China, Bangladesh, Turkey, India, and Cambodia [223].

In this context, LCA, a comprehensive methodology for quantifying resource consumption, energy use, emissions, and waste generation at each stage of production becomes essential to support textile sustainability claims from raw material extraction and fibre processing to manufacturing, distribution, use, and end-of-life disposal [224]. It is becoming increasingly valuable for guiding decision making and helping textile manufactures adopt more sustainable strategies [44,225,226] which range from ecodesign principles to regenerative agriculture and circular business models [227,228]. However, despite being conducted under established international standards (ISO 14040:2006—Principles and framework [229], and ISO 14044:2006—Requirements and guidelines [230]), LCA outcomes in textiles are highly sensitive to regional factors, electricity grid mix, and user behaviour during the use phase (e.g., washing habits, ironing) [231]. In addition, and most LCA studies that are currently available focus on isolated processes rather than full supply chains, often overlooking regional differences in waste management practices [219]. Despite the growing number of LCA studies on natural and regenerated fibres, comparability across different production systems remains limited due to substantial methodological inconsistencies. Variations in system boundaries (e.g., cradle to gate vs. cradle to grave), functional units, allocation rules for eco-products, and assumptions regarding electricity mix or irrigation practices can lead to divergent impact estimates even for the same fibre type [203,232]. For instance, flax and jute demonstrate relatively favourable performance under low-input cultivation systems [226]. However, their impacts vary considerably when processing occurs in regions reliant on fossil-fuel-based energy, highlighting the sensitivity of outcomes to local energy mixes. Moreover, many assessments rely on secondary datasets that are limited in scope or outdated, making it difficult to compare fibres produced under distinct agronomic, climatic, or technological conditions [203]. These inconsistencies reduce the reliability of cross-study comparisons and highlight the need for standardised LCA protocols tailored to textile supply chains.

At the fibre stage, raw material selection, energy sources, and chemical inputs are critical determinants. For example, flax fibres have demonstrated relatively favourable performance, particularly when cultivated using low-input agricultural practices and processed through efficient retting and scutching operations [233]. Similarly, jute has consistently shown low environmental impacts, especially during yarn preparation and spinning, making it a promising candidate for sustainable textiles [44]. Comparative LCAs on semi-synthetic fibres from regenerated plant cellulose have also revealed that, in terms of global warming potential, viscose (sourced from wood pulp like beech, spruce, pine, eucalyptus, cotton linters or bamboo) outperforms lyocell (mostly sourced from wood pulps, such as eucalyptus, beech and birch) under specific production conditions [234], while synthetic fibres, like polyester, remain problematic due to high terrestrial ecotoxicity, particularly in the dyeing and finishing stages [44]. Unfortunately, emerging fibre technologies have been poorly evaluated through LCA. Compared to cotton, viscose, and lyocell, bacterial cellulose lyocell has lower water consumption, no pesticide use, and avoids land use change and deforestation, but it can have other environmental constrains related to the preparation of the culture medium, followed by cellulose washing and high energy consumption [235]. Regional agricultural conditions further complicate comparisons across fibres. For example, the environmental profile of cotton varies dramatically depending on irrigation intensity, pesticide regulation, and the energy sources used in ginning and spinning. Likewise, the impacts of emerging fibres such as hemp, acaba, nettle, and pineapple are strongly shaped by local cultivation methods, soil fertility, retting techniques, and levels of mechanisation [88]. Without harmonised datasets that capture these regional specificities, existing LCAs provide only partial and often non-comparable insights into the performance of different fibre crops [203].

Recycled fibres generally exhibit lower impacts in climate change, resource depletion, and water use [219], yet mechanical recycling remains concentrated on cotton and wool where repeated processing can shorten staples and weaken yarns, driving downcycling [219]. Even so, evidence that mechanically recycled denim blended with virgin cotton can yield knitted fabrics comparable in quality to virgin textiles while reducing global warming potential, acidification, and abiotic depletion indicates that design choices and blending strategies can preserve performance and deliver environmental gains [236]. Nevertheless, scaling these benefits is constrained by uneven infrastructure and variable feedstock quality that complicates process control and assurance [236]. Because process energy shapes the magnitude of these gains, integrating renewables becomes crucial, as shown in home textiles where blending cotton with recycled polyethylene terephthalate under solar-powered production reduced global warming potential and water use by up to 6% and 14% percent, respectively, underscoring that fibre recycling and clean energy must advance together to maximise benefits [237]. In parallel, chemical pathways such as cellulose carbamate, which enable fibre-to-fibre recycling of cotton-rich waste through the carbamate route, can substantially cut climate impact, energy demand, and water scarcity when supplied with renewable electricity. Yet, they still carry process hotspots, notably sodium hydroxide consumption and steam generation, that dominate residual burdens and therefore merit targeted optimisation [218,238]. Beyond mechanical and chemical recycling, the use of waste natural fibres often requires additional post-processing and chemical treatments to restore fibre quality and enable their incorporation into new textile products [239]. Such processes may involve fibre cleaning, depolymerisation, or chemical modification to improve spinnability and mechanical strength [240]. Recent studies highlight that alkali treatment, enzymatic processing, and solvent-based regeneration can enhance fibre recyclability and reduce downcycling risks, although they also introduce new environmental burdens related to reagent use and energy demand [60]. Integrating these post-processing steps into recycling strategies is therefore critical to balance performance recovery with sustainability outcomes, underscoring the importance of coupling fibre recycling with clean energy and optimised chemical management.

At the company level, gate-to-gate LCA of a textile firm in Surat, India, revealed that dyeing and finishing stages were the most resource-intensive, having ozone depletion, acidification, and global warming as dominant impact categories [232], which calls for interventions such as renewable energy adoption and zero liquid discharge systems to mitigate environmental harm. In fact, wastewater treatment plays an important role in textile environmental footprint. Chemical and electrochemical processes for treating textile effluents were compared, showing that the Electro-Fenton method offered lower carbon footprints and reduced environmental loads across most ReCiPe impact categories [241]. Electricity and reagent use (e.g., aluminium sulphate and slaked lime) were identified as critical hotspots, with sludge disposal contributing significantly to CO2 emissions, underscoring the need for cleaner energy sources and optimised chemical management in textile wastewater treatment [241].

Methodological advances are redefining the role of Life Cycle Assessment in textiles. It has been argued that coupling LCA with social and economic indicators enables holistic decision making [44], whereas integrating LCA with machine learning can forecast environmental outcomes and support process optimisation at time of design [242]. Complementary digital infrastructures, including the Internet of Things and blockchain-based recordkeeping, can leverage real-time data on material flows, processing conditions, and end-of-life routing to substantiate traceability and transparency in sourcing, production, and recycling claims [219]. Together, these approaches increase the temporal and spatial resolution of inventory data, improve model fidelity through empirically grounded inputs, and expand the applicability of LCA to complex and rapidly evolving textile supply chains.

So far, the life cycle impacts of emerging fibre crops such as hemp, stinging nettle, pineapple leaf fibre, and abaca remain insufficiently characterised. In hemp cultivation, the most impacting process is fertilisation, mainly due to P2O5 production, followed by ploughing, cutting, and baling activities; however, hemp’s rapid growth and high biomass offer carbon sequestration and lower land use potential, partially offsetting emissions [243]. Unfortunately, most LCA databases do not report any inventory data for hemp fibre production, although it is assumed that impacts are very close to kenaf, jute and flax fibres, outperforming cotton in impact categories such as global warming potential, land occupation and acidification, particularly when cropped under reduced tillage [243,244]. The limited LCAs available for abaca and pineapple leaf fibre suggest comparatively lower environmental burdens than conventional fibres [245]. However, the evidence is fragmentary (often cradle-to-gate, geographically narrow, and reliant on secondary data), highlighting the need for comprehensive cradle-to-grave assessments with consistent functional units, transparent allocation rules, and explicit end-of-life scenarios to robustly characterise performance and enable credible integration into sustainable textile value chains.

5.4. Social Life Cycle Assessment

The UNEP/SETAC Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) [246,247] provide a foundational framework for evaluating the social and socio-economic impacts of products and services throughout their life cycles. Developed collaboratively by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC), these guidelines aim to complement environmental LCA and life cycle costing by integrating the social dimension into sustainability assessments. The first edition was published in 2009, with a major update released in 2020 [248] to reflect methodological advancements and practical experiences gained over the past decade. The guidelines define six core stakeholder categories (workers, local communities, society, consumers, value chain actors, and children), each associated with specific subcategories such as fair wages, working hours, health and safety, freedom of association, and community engagement. These indicators are used to assess both positive and negative social impacts across the entire life cycle of a product, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal. Two main approaches are used for impact assessment: the performance reference point method, which evaluates stakeholder conditions at different life cycle stages, and the impact pathway method, which uses characterisation models to assess social outcomes. While the guidelines offer a sector-neutral foundation, recent research has emphasised the need for sector-specific adaptation, particularly in industries like textiles where social risks such as gender inequality, supply chain transparency, and occupational health are prominent.

Supported by the UNEP/SETAC guidelines and the Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment database [249], S-LCA was applied to a men’s cotton shirt produced across five countries: China (cotton farming and spinning), Malaysia (fabric production), Bangladesh and Myanmar (garment manufacturing), and the Netherlands (retail). Overall, high social risks were identified in several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including poor working conditions and exposure to hazards (SDG3), high energy use in manufacturing stages (SDG 7), excessive overtime, low wages, and labour rights violations (SDG8), and lack of transparency and unsustainable practices (SDG12). Risk hotspots were concentrated in the spinning stage, garment manufacturing, and fabric production [249]. More recently, Fidan et al. [250] significantly advanced the application of S-LCA to the textile industry by critically evaluating and refining the subcategories proposed by the UNEP/SETAC guidelines. Through a combination of literature review and stakeholder interviews, additional subcategories not previously emphasised in S-LCA were identified, including gender pay gap, collaboration with NGOs, academic engagement, and circularity implementation. This expanded set of indicators enhances the sectoral relevance and diagnostic power of S-LCA, enabling more accurate assessments of social performance across the textile value chain.

Ultimately, coupling S-LCA with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is vital for addressing the evolving social risks in the textile and fashion industry, especially under circular economy transitions [251]. S-LCA provides a structured, evidence-based framework to identify and assess social impacts across the product life cycle, whereas CSR offers the strategic direction and stakeholder engagement needed to turn these assessments into action. Together, they help companies move beyond compliance and advance measurable, inclusive social sustainability. However, this requires clear guidelines, standardised indicators, and stronger stakeholder engagement to enhance credibility and comparability. To help streamline this process, the Organizational Life Cycle Assessment (O-LCA) methodology was applied to a case study of a spinning company, which revealed benefits for decision making by pinpointing social hotspots, data gaps, and priority improvement actions [252]. Still, the broader application of O-LCA is constrained by variable data quality and the lack of comparable, context-sensitive metrics. Combining S-LCA with O-LCA into Social Organizational Life Cycle Assessment (SO-LCA) offers a more holistic and actionable framework for evaluating social sustainability across both products and organisational practices. SO-LCA enables companies, especially SMEs and complex supply chain actors, to identify systemic social risks, align with sustainability goals like the SDGs, and improve decision making through context-sensitive, scalable indicators. SO-LCA was applied to micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in the Ecuadorian textile sector as a framework to identify strengths and weaknesses in social performance [253]. Assessing 121 indicators across worker and consumer subcategories, they found that these enterprises tend to perform well in regulated areas such as occupational safety and social benefits, yet show consistent shortcomings in freedom of association, layoff practices, and worker development. The authors also highlight the need to adapt SO-LCA to the realities of MSMEs by simplifying data collection, contextualising indicators, and developing digital tools, thereby improving decision making and fostering socially responsible practices in resource-constrained settings. To clarify how these approaches differ and how they complement one another within textile sustainability evaluation, an overview of LCA, S-LCA, and SO-LCA is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of LCA—Environmental Life Cycle Assessment, S-LCA—Social Life Cycle Assessment, and SO-LCA—Social Organizational Life Assessment.

These findings show that, although legislative frameworks, eco-labelling initiatives, and Life Cycle Assessment provide essential foundations for sustainable textiles, important gaps persist. Regulations and certification schemes remain fragmented, eco-labels face credibility challenges, and Digital Product Passports raise issues of interoperability and data governance. LCA databases lack robust coverage of emerging fibres such as hemp, nettle, pineapple, and abaca, while social indicators are inconsistently applied across supply chains. Future work should prioritise harmonising standards, expanding datasets, and integrating environmental and social dimensions into unified frameworks. Addressing these shortcomings is critical to ensure transparent, verifiable sustainability claims and enable alternative fibres to credibly support textile transitions.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Within this enabling landscape, molecular approaches, including DNA fingerprinting, species-specific assays, and metagenomic tools, can strengthen evidence on fibre identity, particularly in blends and after wet processing, and connect physical goods with auditable digital records across complex value chains. However, analytical performance can decline in heavily processed, blended, or recycled textiles due to DNA degradation, contamination, and reduced signal-to-noise. Future research should prioritise validation under realistic industrial conditions, including ring trials across laboratories, harmonised extraction and detection workflows for challenging matrices, and open reference libraries that enable reproducible interpretation. Standardised pathways are also needed to embed molecular evidence into Digital Product Passports in ways that are interoperable, privacy-aware, and compatible with third-party assurance.

Environmental and social performance must advance together. Many LCAs still rely on secondary datasets that are geographically narrow or outdated, limiting comparability across production systems and obscuring end-of-life pathways. Harmonised, region-specific inventories with transparent assumptions, consistent functional units, and realistic end-of-life scenarios are essential to improve robustness and reduce uncertainty in cross-study comparisons [207]. Future assessments should move beyond isolated process studies toward systematic LCA across fibre types, processing routes, and regions, integrating circular economy scenarios, life cycle costing, and sensitivity analyses that reflect electricity mixes, irrigation regimes, and logistics. In parallel, S-LCA and SO-LCA should progress from product snapshots to organisation-wide governance and improvement planning, linking identified hotspots to feasible mitigation actions that reflect local labour contexts, supplier structures, and enforcement realities.

Finally, adoption will depend on inclusion. Small- and medium-sized enterprises often face barriers to eco-labelling and digital traceability due to limited financial resources, technical capacity, and administrative burden. Targeted support measures, shared infrastructure, and capacity building are therefore critical to ensure that sustainability transitions are effective across the full supplier base, not only among the largest brands and mills [207]. Priorities include standardised protocols, open and interoperable data systems, supplier training and incentives, and credible third-party verification. With these elements in place, the sector can move from broad promises to accountable performance, directing investment toward fibres and processes that deliver measurable environmental and social gains at scale.

Author Contributions

S.P.d.S.: Writing—original draft, Investigation. M.N.d.S.: Investigation, Writing—review and editing. C.B.: Writing—review and editing. M.W.V.: Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received financial support from integrated project be@t—Textile Bioeconomy (TC-C12-i01, Sustainable Bioeconomy No. 02/C12-i01.01/2022), promoted by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), Next Generation EU, for the period 2021–2026, and by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT, Portugal) through Sofia Pereira de Sousa PhD scholarship 2023.05224.BDANA (DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.05224.BDANA) and through Marta Nunes da Silva CEEC (2023.06124.CEECIND, DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.06124.CEECIND/CP2855/CT0008).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the scientific collaboration under the FCT project UID/50016/2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Desore, A.; Narula, S.A. An overview on corporate response towards sustainability issues in textile industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 1439–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Sen, P.; Pal, P. An integrated green management model to improve environmental performance of textile industry towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E. Environmental Sustainability in the Textile Industry. In Sustainability in the Textile Industry; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 17–55. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Management of Used and Waste Textiles in Europe’s Circular Economy; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abrishami, S.; Shirali, A.; Sharples, N.; Kartal, G.E.; Macintyre, L.; Doustdar, O. Textile Recycling and Recovery: An Eco-friendly Perspective on Textile and Garment Industries Challenges. Text. Res. J. 2024, 94, 2815–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubik, F.; Nebel, K.; Klusch, C.; Karg, H.; Hecht, K.; Gerbig, M.; Gärtner, S.; Boldrini, B. Textiles on the Path to Sustainability and Circularity—Results of Application Tests in the Business-to-Business Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, A. Man-Made Fibers Continue to Grow. Textile World, 3 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, G.; Perera, S. New Approaches to Sustainable Fibres. In Sustainable Fibres for Fashion Industry; Muthu, S.S., Gardetti, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S. Climate change and cotton production: An empirical investigation of Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29580–29588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, M.A.; Bakhsh, K.; Ali, R.; Farhan, M.; Ashraf, M. Does better cotton initiative contribute to health cost reduction in pesticide applicators? Evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 8615–8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delate, K.; Heller, B.; Shade, J. Organic cotton production may alleviate the environmental impacts of intensive conventional cotton production. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2021, 36, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azammi, A.M.N.; Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ibrahim, R.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Asrofi, M.; Atiqah, A. 3—Characterization studies of biopolymeric matrix and cellulose fibres based composites related to functionalized fibre-matrix interface. In Interfaces in Particle and Fibre Reinforced Composites; Goh, K.L., Aswathi, M.K., De Silva, R.T., Thomas, S., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 29–93. [Google Scholar]

- Behnam Hosseini, S. Chapter 13—Natural fiber polymer nanocomposites. In Fiber-Reinforced Nanocomposites: Fundamentals and Applications; Han, B., Sharma, S., Nguyen, T.A., Longbiao, L., Bhat, K.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- Sudamrao Getme, A.; Patel, B. A Review: Bio-fiber’s as reinforcement in composites of polylactic acid (PLA). Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 26, 2116–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, A.; Sanjay, M.R.; Suchart, S.; Jyotishkumar, P. Renewable and sustainable biobased materials: An assessment on biofibers, biofilms, biopolymers and biocomposites. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicińska-Jakubowska, A.; Bogacz, E.; Zimniewska, M. Review of Natural Fibers. Part I—Vegetable Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2012, 9, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyavihalli Girijappa, Y.G.; Mavinkere Rangappa, S.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Siengchin, S. Natural Fibers as Sustainable and Renewable Resource for Development of Eco-Friendly Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, O.; Bledzki, A.K.; Fink, H.-P.; Sain, M. Biocomposites reinforced with natural fibers: 2000–2010. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1552–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Ferrer, F.; Vilaplana, F.; Ribes-Greus, A.; Benedito-Borrás, A.; Sanz-Box, C. Flour rice husk as filler in block copolymer polypropylene: Effect of different coupling agents. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 99, 1823–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komuraiah, A.; Kumar, N.S.; Prasad, B.D. Chemical Composition of Natural Fibers and its Influence on their Mechanical Properties. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2014, 50, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobovikov, M.; Ball, L.; Guardia, M. World Bamboo Resources: A Thematic Study Prepared in the Framework of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005; Food & Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2007; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, K. Properties and Performance of Natural-Fibre Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- La Mantia, F.P.; Morreale, M. Green composites: A brief review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H.S. Introduction to Textile Fibres; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal, S.; Dimri, S.; Riyal, I.; Sharma, H.; Dwivedi, C. Natural fibres and their composites: A review of chemical composition, properties, retting methods, and industrial applications. Cellulose 2025, 32, 3497–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]