Trace Detection of Ibuprofen in Solution Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Principle of SPR

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. SPR Sensing Chip Preparation

3.3. Setup and Detection

3.4. Contact Angle Measurement and Surface Morphology Characterization

4. Results and Discussion

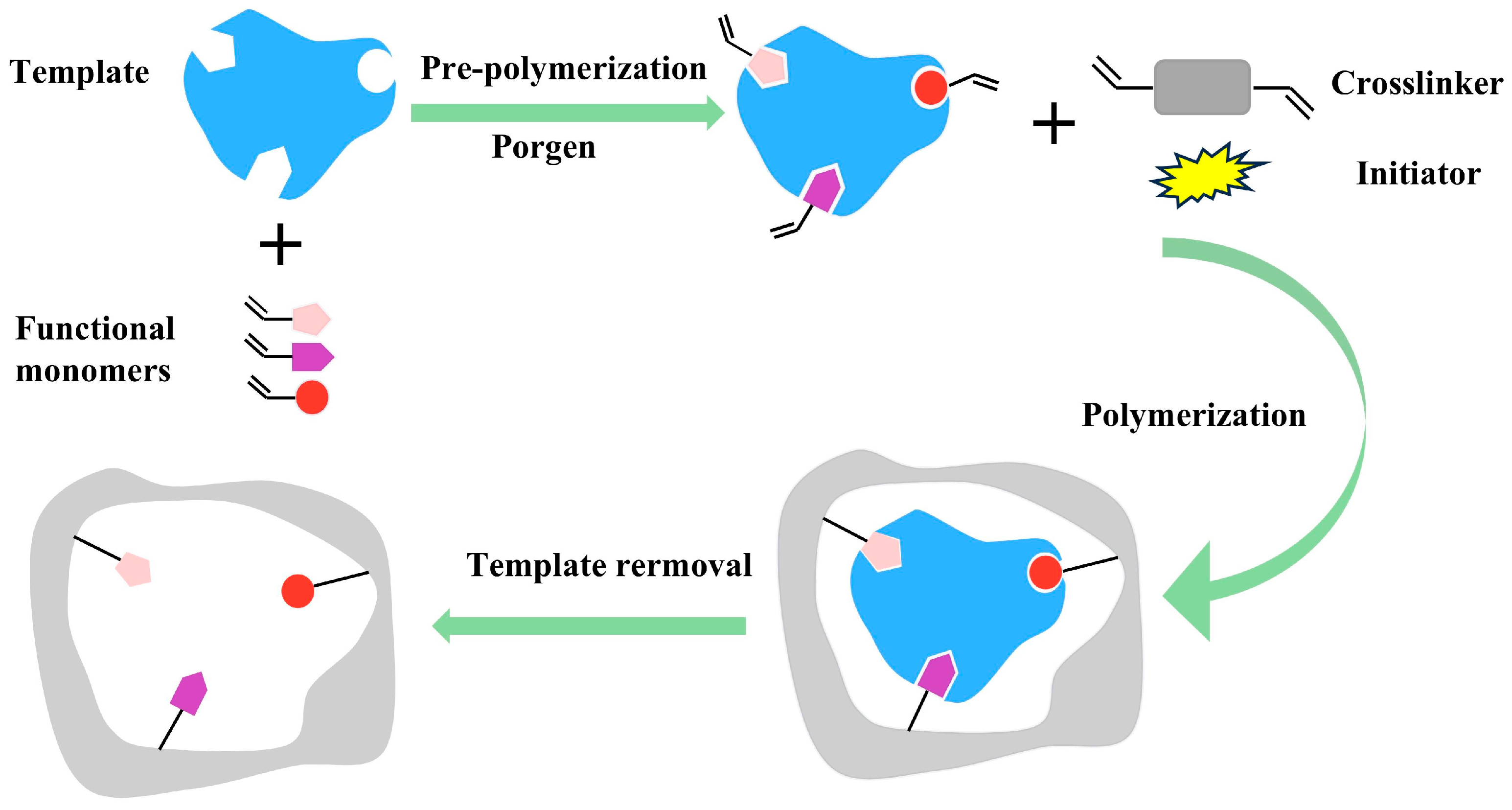

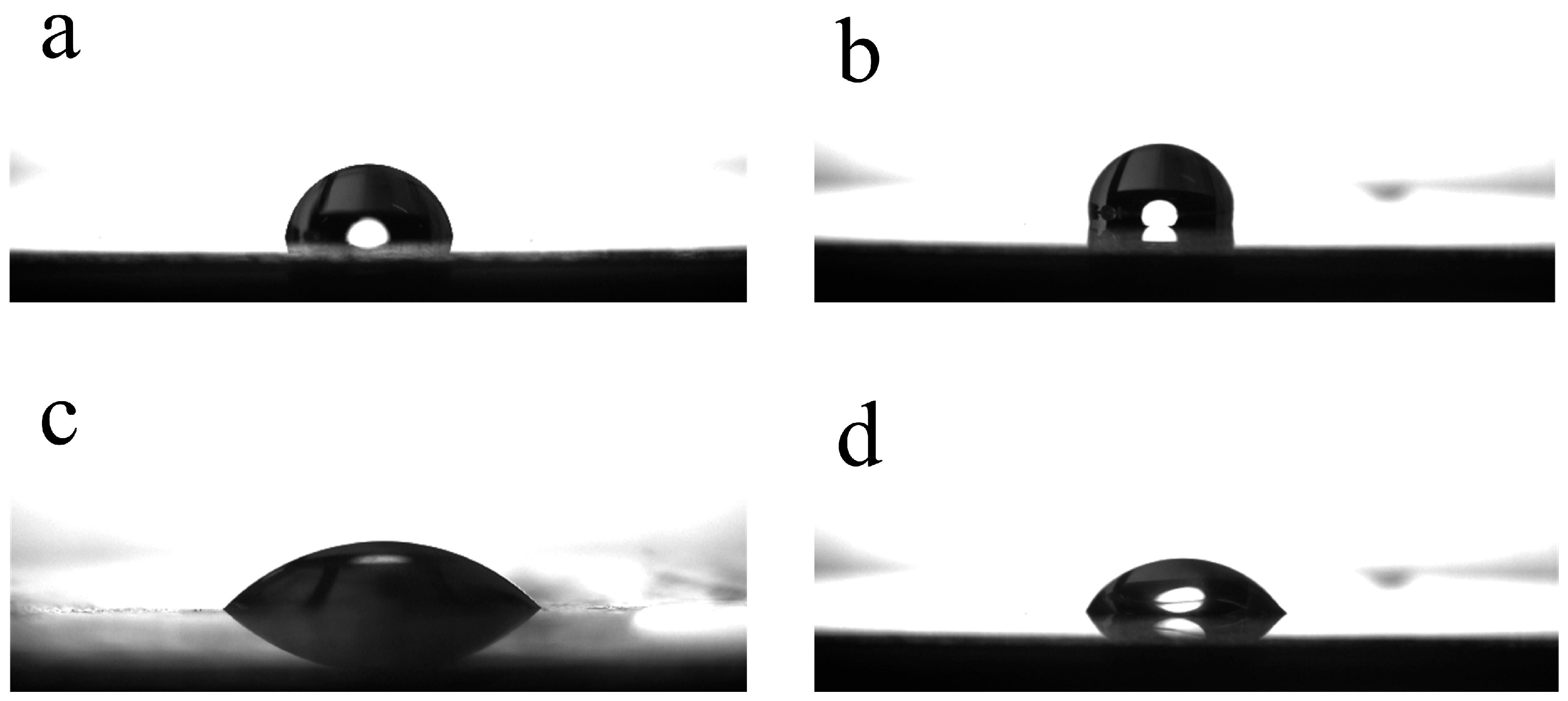

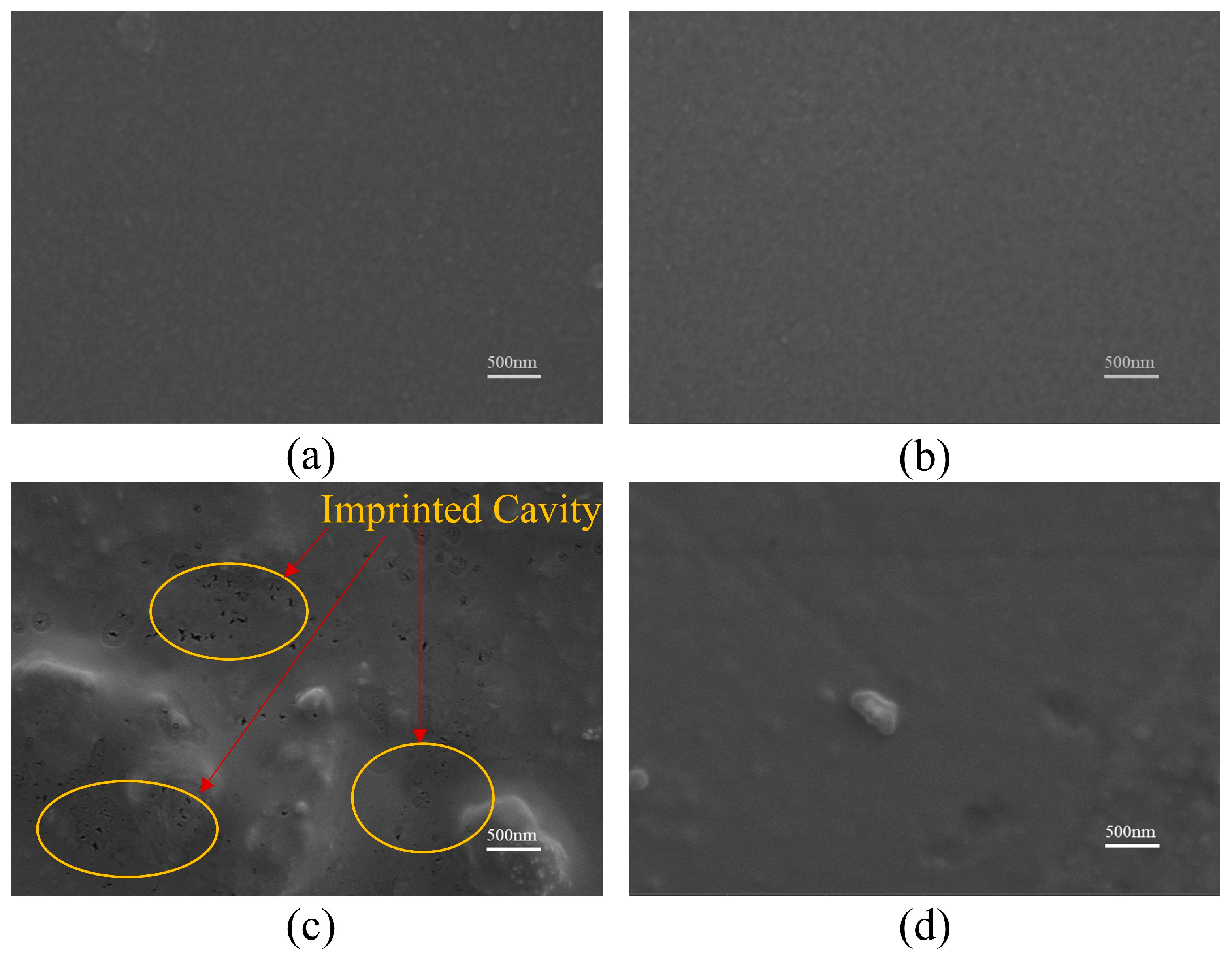

4.1. Film Characterization

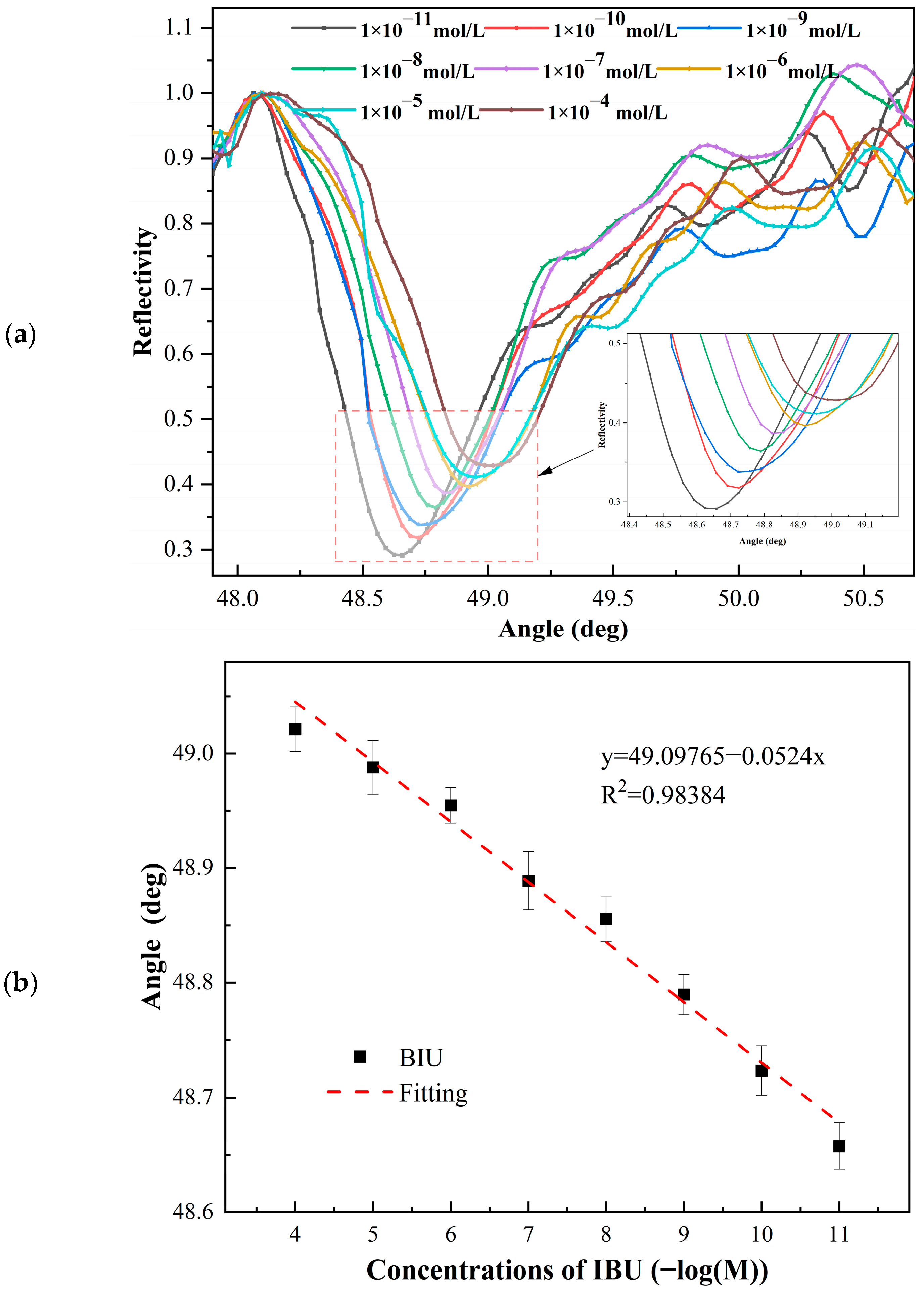

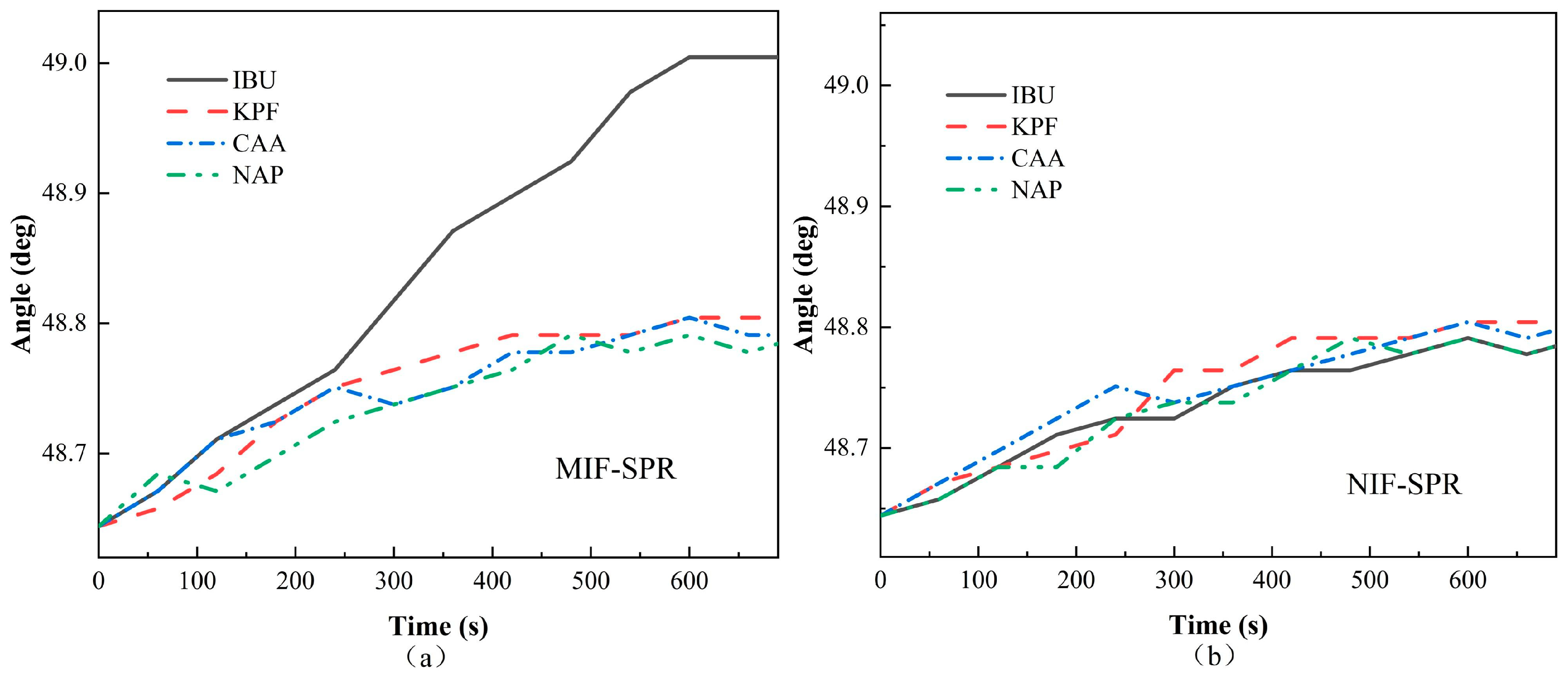

4.2. SPR Detection Results

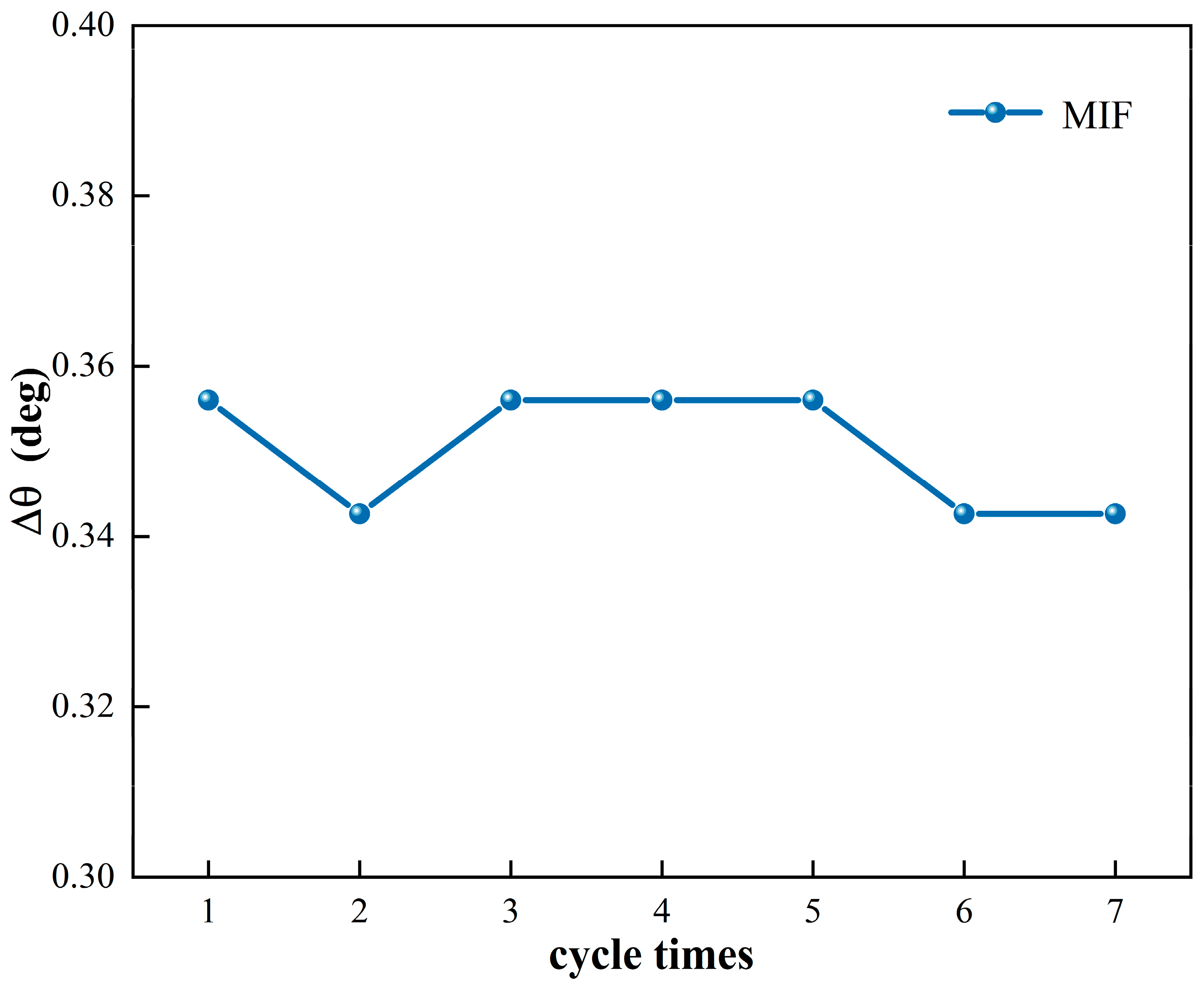

4.3. Selectivity and Reproducibility of the MIF

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, Y.; Khanal, S.K.; Yin, L.; Sun, L.; Lu, H. Influence of Ibuprofen and Its Biotransformation Products on Different Biological Sludge Systems and Ecosystem. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Q.; Dai, L.; Dang, Z. Occurrence, Removal and Risk Evaluation of Ibuprofen and Acetaminophen in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Critical Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-T.; Wang, J.-H.; Ding, D.-C. Ibuprofen Use and Male Infertility: Insights from a Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 307, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellepola, N.; Ogas, T.; Turner, D.N.; Gurung, R.; Maldonado-Torres, S.; Tello-Aburto, R.; Patidar, P.L.; Rogelj, S.; Piyasena, M.E.; Rubasinghege, G. A Toxicological Study on Photo-Degradation Products of Environmental Ibuprofen: Ecological and Human Health Implications. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 188, 109892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldewachi, H.; Omar, T.A. Development of HPLC Method for Simultaneous Determination of Ibuprofen and Chlorpheniramine Maleate. Sci. Pharm. 2022, 90, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-Q.; Cui, Y.-Y.; Lin, X.-H.; Yang, C.-X. Fabrication of Polyethyleneimine Modified Magnetic Microporous Organic Network Nanosphere for Efficient Enrichment of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs from Wastewater Samples Prior to HPLC-UV Analysis. Talanta 2021, 233, 122471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatawi, H.; Hogan, A.; Albalawi, I.; O’Sullivan-Carroll, E.; Alsefri, S.; Wang, Y.; Moore, E. Rapid Determination of NSAIDs by Capillary and Microchip Electrophoresis with Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detection in Wastewater. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 1944–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, S.; Jiang, M.; Xu, J.; Wei, R. Cobalt Oxide-Based Nanocomposites for Colorimetric Detection of Ibuprofen as a Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug in Orthopedic Pain. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 108, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gu, D.; Gao, Y. An Improved Dispersion Law of Thin Metal Film and Application to the Study of Surface Plasmon Resonance Phenomenon. Opt. Commun. 2014, 329, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglich, P.; Lecci, G.; Mai, A. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Spectroscopy and Photonic Integrated Circuit (PIC) Biosensors: A Comparative Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Han, S.; Wei, L. High-Sensitivity Concentration Detection of Trace Doxycycline in Solution by Molecular Imprinting Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2024, 41, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Yu, N.; Shi, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, J. Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Antibiotics Detection Based on Photo-Initiated Polymerization Molecularly Imprinted Array. Talanta 2016, 161, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakır, O.; Baysal, Z. Pesticide Analysis with Molecularly Imprinted Nanofilms Using Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor and LC-MS/MS: Comparative Study for Environmental Water Samples. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 297, 126764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birinci, H.S.; Akgönüllü, S.; Yavuz, H.; Arslan, O.; Denizli, A. Design of Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Based Biomimetic Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Detection of Methamphetamine in Plasma and Urine. Microchem. J. 2025, 213, 113668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Wang, C.; Gao, L.; Nie, C. Fundamentals, Synthetic Strategies and Applications of Non-Covalently Imprinted Polymers. Molecules 2024, 29, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, C.; Chen, C.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Shang, P. Determination of Kanamycin Using a Molecularly Imprinted SPR Sensor. Food Chem. 2018, 266, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.P.; Fafara, A.; VanderNoot, V.A.; Kono, M.; Polsky, B. Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors Using Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for Sorbent Assay of Theophylline, Caffeine, and Xanthine. Can. J. Chem. 1998, 76, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Cheng, X.; Liu, B. Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Detection of Parathion Methyl in Water. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2017, 21, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereli, N.; Çimen, D.; Hüseynli, S.; Denizli, A. Detection of Amoxicillin Residues in Egg Extract with a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer on Gold Microchip Using Surface Plasmon Resonance and Quartz Crystal Microbalance Methods. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 4152–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakır, O.; Bakhshpour, M.; Göktürk, I.; Yılmaz, F.; Baysal, Z. Sensitive and Selective Detection of Amitrole Based on Molecularly Imprinted Nanosensor. J. Mol. Recognit. 2021, 34, e2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, T.; Ahmad, M.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Wei, T. A Recyclable Tetracycline Imprinted Polymeric SPR Sensor: In Synergy with Itaconic Acid and Methacrylic Acid. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 3102–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, H.-S.; Guo, J.; Lindquist, R.G.; Liu, Q.H. Surface Plasmon Resonance in Nanostructured Metal Films under the Kretschmann Configuration. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 124314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekgasit, S.; Thammacharoen, C.; Knoll, W. Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectroscopy Based on Evanescent Field Treatment. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Shi, H.; Han, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, R.; Men, J. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers by the Surface Imprinting Technique. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 145, 110231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, J.; Tamaki, K.; Sugimoto, N. Molecular Imprinting in Alcohols: Utility of a Pre-Polymer Based Strategy for Synthesizing Stereoselective Artificial Receptor Polymers in Hydrophilic Media. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 466, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Lu, H.; Zheng, X.; Chen, L. Stimuli-Responsive Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: Versatile Functional Materials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Yadav, S.; Sajal, V. Theoretical Analysis of Highly Sensitive Prism Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor with Indium Tin Oxide. Opt. Commun. 2014, 318, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Velasco, G.; Hinojosa-Reyes, L.; Escamilla-Coronado, M.; Turnes-Palomino, G.; Palomino-Cabello, C.; Guzmán-Mar, J.L. Iron Metal-Organic Framework Supported in a Polymeric Membrane for Solid-Phase Extraction of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1136, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roushani, M.; Shahdost-fard, F. Ultra-Sensitive Detection of Ibuprofen (IBP) by Electrochemical Aptasensor Using the Dendrimer-Quantum Dot (Den-QD) Bioconjugate as an Immobilization Platform with Special Features. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 75, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analytical Methods | Concentration Range | Detection Limit | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC | 4.85 × 10−7~1.5 × 10−6 mol/L | 8.73 × 10−9 mol/L | [28] |

| electrochemical analysis | 1 × 10−12 mol/L~ 1.2 × 10−8 mol/L | 3.33 × 10−13 mol/L | [29] |

| capillary electrophoresis | 4.85 × 10−6~9.7 × 10−5 mol/L | 2.9 × 10−6 mol/L | [7] |

| colorimetric methods | 1 × 10−3~1 mol/L | 1 × 10−4 mol/L | [8] |

| MIF-SPR | 10−11 ~10−4 mol/L | 10−11 mol/L | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, S.; Yang, Z.; Jia, S.; Zhao, F.; Xu, Z. Trace Detection of Ibuprofen in Solution Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010498

Han S, Yang Z, Jia S, Zhao F, Xu Z. Trace Detection of Ibuprofen in Solution Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010498

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Sijia, Zhitao Yang, Songlin Jia, Fenglei Zhao, and Zehong Xu. 2026. "Trace Detection of Ibuprofen in Solution Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010498

APA StyleHan, S., Yang, Z., Jia, S., Zhao, F., & Xu, Z. (2026). Trace Detection of Ibuprofen in Solution Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010498