Abstract

Long-duration energy storage (LDES) can deliver system-wide flexibility and decarbonization benefits, yet investment is often hindered because these benefits are diffuse and not fully monetized under conventional market structures. A public-asset-oriented valuation and cost-allocation framework is proposed for LDES. First, LDES externality benefits are quantified through a system-level optimization-based simulation on a stylized aggregated regional network, with key indicators including thermal generation cost, carbon penalty, renewable curtailment cost, involuntary load shedding, and end-user electricity expenditures. Second, LDES investment costs are allocated among thermal generators, renewable operators, grid entities, and end users via a benefit-based Nash bargaining mechanism. In the case study, introducing LDES reduces thermal generation cost by 3.92%, carbon penalties by 5.59%, and renewable curtailment expenditures by 7.07%, while eliminating load shedding. The resulting cost shares are 46.9% (renewables), 28.7% (end users), 22.4% (thermal generation), and 0.5% (grid entity), consistent with stakeholder-specific benefit distributions. Sensitivity analyses across storage capacity and placement further show diminishing marginal returns beyond near-optimal sizing and systematic shifts in cost responsibility as benefit patterns change. Overall, this framework offers a scalable, economically efficient, and equitable strategy for cost redistribution, supporting accelerated LDES adoption in future low-carbon power systems.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

With the accelerated advancement of China’s “dual carbon” targets and the construction of a new-type power system, the large-scale integration of renewable energy sources has introduced unprecedented challenges in system regulation and operational security [1,2]. Long-duration energy storage (LDES), characterized by its ability to shift energy temporally and provide sustained system flexibility, has emerged as a key enabling technology for enhancing renewable energy consumption and ensuring power system reliability [3,4,5]. However, aside from pumped hydro storage—which benefits from mature deployment and favorable economics, most emerging LDES technologies (e.g., long-life electrochemical batteries, thermal storage, hydrogen-based systems) still face significant barriers, including low round-trip efficiency and high lifecycle costs. These technical and economic limitations prevent them from achieving profitability through conventional market mechanisms such as energy arbitrage or capacity payments, thereby impeding large-scale commercial deployment [6].

Conventional assessments of energy storage predominantly focus on private returns, emphasizing market-based profitability or the benefits accrued by individual users. This narrow perspective often overlooks the broader externalities and societal gains that storage provides through enhanced system security, flexibility, and decarbonization [7,8]. From a system-level viewpoint, LDES provides public service attributes that are partially non-excludable and non-rival, including capacity adequacy, reserve provision, peak–valley load balancing, and deep decarbonization. These characteristics are consistent with the economic definition of public or quasi-public goods [9]. Public goods are non-rival and non-excludable, club goods are largely non-rival but partially excludable, and regulated infrastructure provides system-critical services with regulated cost recovery. LDES is treated in this paper as a public asset in the form of regulated-type infrastructure (rather than a pure public good or a club good), because its adequacy, flexibility, and decarbonization benefits are widely shared and only imperfectly attributable to individual parties. This characterization explains why market revenues alone are often insufficient and motivates a benefit-based cost allocation mechanism in which stakeholders contribute according to their realized system-level gains. Recognizing long-duration energy storage as a public asset allows for a more comprehensive valuation of its contribution to overall system welfare.

The deployment of LDESs is expected to significantly reshape the supply–demand equilibrium and the market price structure of power systems, generating differentiated impacts across various industry stakeholders such as power grid operators, renewable energy developers, thermal and gas-fired generation units, and large industrial consumers. For instance, power grid companies can enhance system-level peak shaving and reserve capabilities, thereby deferring investments in transmission infrastructure expansion [10]. Renewable energy developers may benefit from improved energy utilization efficiency and reduced curtailment losses [11]. In contrast, certain thermal power units may experience adverse effects, including diminished demand for peaking services and reduced operating hours. Due to the heterogeneous value perceptions and benefit realizations among stakeholders, uniform or equal-cost allocation mechanisms are often inadequate in ensuring fairness and incentive compatibility. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a differentiated and quantifiable cost-sharing framework that reflects each stakeholder’s realized benefit and contribution to system value. Such a mechanism adheres to the fairness principle of benefit-based participation, whereby those who gain more contribute more, and can further facilitate efficient investment signals and socially coordinated deployment of long-duration energy storage.

1.2. Literature Review

With the continuous increase in renewable energy penetration and the escalating demand for system flexibility, the importance of LDES in ensuring the security, economic efficiency, and low-carbon operation of power systems has become increasingly evident. Existing studies in this field primarily fall into two categories: first, the economic evaluation and system value quantification of energy storage technologies under various market and operational scenarios; second, the investigation of the public-good attributes of energy storage and the development of associated cost-sharing mechanisms.

In the domain of economic evaluation of energy storage, the academic community has primarily employed approaches such as levelized cost of storage (LCOS), arbitrage revenue modeling, and investment payback period analysis to assess the financial viability of individual storage technologies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. The LCOS method distributes capital expenditure, operation and maintenance costs, and depreciation across the total energy output of the system, providing an intuitive metric for comparing the economic competitiveness of various technologies, including pumped hydro, compressed air energy storage, and electrochemical storage [15]. Arbitrage-based models estimate the revenue potential of storage systems by simulating their behavior under time-varying electricity prices, charging during low-price periods and discharging during high-price periods, thereby evaluating their profitability in wholesale energy market [16]. Furthermore, investment payback period analysis offers insights into the economic attractiveness and risk exposure timeline of storage projects, serving as a reference for investment decision-making under different market and policy conditions [17]. However, these methods are primarily limited to the device level and fail to capture the external, system-wide value of energy storage in operational and planning contexts. In recent years, research has progressively shifted toward a system-level perspective, emphasizing the holistic contributions of energy storage in reducing overall system operating costs, facilitating renewable energy integration, participating in ancillary services such as frequency regulation, and mitigating carbon emissions [18,19,20]. System cost minimization models have demonstrated that energy storage can reduce fuel consumption and defer investments in peaking capacity by optimizing unit commitment schedules and power flow distribution, thereby lowering total system expenditures [21]. Furthermore, several studies have proposed analytical frameworks for quantifying the capacity value and carbon abatement value of storage, incorporating its role in backup provision and emission reduction into economic evaluations. These studies highlight that the marginal value of storage rises significantly in low-carbon power systems with higher renewable energy penetration levels [22]. In addition, the social welfare gain (SWG) framework has been introduced to evaluate the multi-stakeholder benefits of storage under liberalized electricity markets [23,24]. By treating storage as a system resource that enhances overall welfare distribution and reliability, this approach constructs a social welfare maximization model that captures the cooperative value of storage across market participants. Empirical results suggest that energy storage not only improves short-term operational efficiency but also offers long-term benefits in reducing generation costs and enhancing renewable energy utilization within planning horizons [25]. Overall, research on the economics of energy storage is evolving from a focus on project-level profitability to a broader emphasis on system-level impacts and cross-sectoral value creation. This paradigm shift reflects a growing academic consensus: energy storage should not merely be viewed as an isolated asset for arbitrage but as a critical infrastructure component that enhances the flexibility, efficiency, and resilience of future power systems.

From a system-level perspective, energy storage not only generates direct revenue through price arbitrage and participation in ancillary service markets, but also creates external value for multiple stakeholders across the power system. For renewable energy developers, storage deployment can increase the share of renewable generation, reduce curtailment, and enhance revenue streams by improving output dispatchability. For grid operators, energy storage can suppress system peak demand, improve the utilization rate of transmission infrastructure, and reduce both capital investments and operational expenditures. For end users, storage contributes to electricity price stabilization and enhances supply reliability, thereby delivering indirect economic and reliability benefits [26]. Therefore, energy storage systems possess a dual nature: they generate private revenues through energy price arbitrage and participation in ancillary service markets, while simultaneously delivering significant public value by enhancing system flexibility and facilitating renewable energy integration. This dual attribute underscores the need for appropriate institutional arrangements and market mechanisms that support both cost-sharing and benefit distribution among stakeholders. Existing research has primarily addressed storage-related cost recovery and benefit distribution using cooperative game theory and mechanism design, aiming to produce fair and incentive-compatible allocation rules [27]. Two previous works [28,29] both adopted improved Shapley-value-based mechanisms to determine cost-sharing proportions according to stakeholders’ marginal contributions, and apply the resulting allocations to multi-party responsibility sharing in storage-related services. Another study [30] further applied cooperative-game-based allocation (e.g., nucleolus-type solutions) to apportion paid peak-shaving costs among heterogeneous sources and loads, emphasizing stability against coalition deviations. Beyond cooperative allocations, one study [31] employed a Stackelberg leader–follower game to design tariff and cost-sharing rules in off-grid microgrids, showing how hierarchical pricing incentives can reshape participants’ behaviors and improve system performance. Complementarily, another paper [32] introduced a Nash–Harsanyi bargaining framework for negotiated cost allocation in multi-agent integrated energy systems, where bargaining weights are used to reflect heterogeneous preferences.

Accordingly, three research gaps are identified. (i) Existing static or annual-scale studies under-represent the chronological, network-constrained valuation of LDES externalities, which can bias the estimation of time-coupled benefits. (ii) A unified pipeline that links system-level welfare decomposition with stakeholder-level benefit attribution remains lacking, hindering the translation of quantified benefits into implementable, benefit-based cost recovery. (iii) For quasi-public procurement of LDES, an allocation mechanism that is simultaneously benefit-consistent and individually rational under an explicit no-LDES disagreement baseline has yet to be established.

1.3. Contributions

Accordingly, this study is conducted to develop a valuation-to-allocation framework for LDES from a public-asset perspective, in which system-level externality value is quantified and investment costs are allocated among stakeholders in a fair and transparent manner. The main contributions are threefold:

(1) This study proposes a system-level value evaluation model for LDES from a public asset perspective. The model comprehensively captures the contributions of LDES to system security, capacity adequacy, operational flexibility, and carbon reduction. It quantifies the impact of storage configurations on total social cost and welfare under various scenarios. Compared with traditional approaches focused on commercial returns or single-market revenues, the proposed framework better reflects the societal value of LDES and provides quantitative support for its functional positioning and compensation mechanism design at the system level.

(2) A cost-sharing mechanism for LDES is proposed based on asymmetric Nash bargaining theory. To address the substantial differences in benefit distribution among stakeholders such as power grid operators, renewable energy developers, thermal power producers, and large industrial users, this study develops a differentiated allocation method that accounts for sectoral heterogeneity and benefit proportion. The proposed mechanism ensures fairness and maintains incentive compatibility across stakeholders, effectively overcoming the limitations of existing equal or proportional cost-sharing approaches in terms of equity and efficiency.

(3) A typical regional power system case is used to evaluate the system-level benefits and cost-sharing outcomes of different long-duration energy storage deployments. The results demonstrate that the proposed model significantly improves renewable energy integration, reduces system peak-shaving costs, and achieves fair and efficient cost allocation among stakeholders. These findings confirm the feasibility and effectiveness of realizing the collaborative value of LDES from a public asset perspective.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the public-asset-oriented framework and the system-level LDES valuation model, together with the solution algorithm. Section 3 reports the case study and discusses the quantified system-level benefits and the resulting cost-allocation outcomes. Section 4 concludes the paper and summarizes practical implications for LDES cost recovery and coordinated investment. Section 5 is provided to summarize the limitations of this study and outline directions for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Public-Asset-Oriented Cost Allocation for Long-Duration Energy Storage

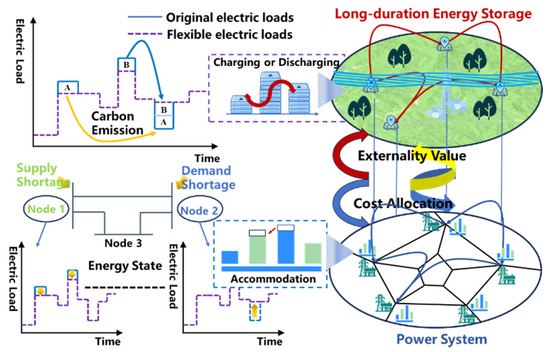

Here, public asset does not necessarily imply public ownership. Instead, it denotes a planning and regulatory setting in which LDES is procured to maximize system welfare and its costs are subsequently recovered through a structured cost-sharing scheme, because the associated benefits (e.g., reduced curtailment, improved adequacy, and lowered carbon-related costs) are widely distributed across stakeholders. To quantify the overall value contribution of LDES and to allocate its system costs in a fair and transparent manner, this paper proposes a research framework based on a public asset perspective, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cost-allocation framework for LDES from a public-asset perspective.

A valuation-to-allocation framework is adopted. For an LDES decision , the system-level value is quantified as and stakeholder-specific benefits are computed as , where and are obtained through chronological, network-constrained optimization. The investment cost is then allocated via an asymmetric Nash bargaining model with a no-LDES disagreement baseline, by which benefit consistency and voluntary participation are ensured.

(1) System value of LDES: A system-level value assessment model is developed based on long-horizon chronological simulations of power system operations. By accounting for multiple dimensions including operational costs, carbon emission costs, and flexibility metrics, the model quantifies the impact of alternative LDES configuration schemes on total social cost and overall system welfare.

(2) Cost-allocation principles: Recognizing the heterogeneous benefit distribution among stakeholders such as grid utilities, renewable energy developers, coal- and gas-fired generators, and large industrial consumers, a sector-specific cost allocation mechanism is designed based on asymmetric Nash bargaining theory. This mechanism aligns with the fairness principle that those who benefit should contribute and ensures incentive compatibility across all participants.

2.2. Long-Duration Energy Storage System Value Quantification Model

2.2.1. Value Quantification Model

A planning model is developed to quantify the system-level value of LDES, with the objective of minimizing total investment and operational costs while maintaining energy balance across the system. LDES is modeled as a flexible resource that enhances temporal coordination between supply and demand. The model considers a generation mix comprising coal, hydro, wind, and solar power, with renewable and conventional generation capacities, as well as typical load and generation profiles, used as boundary conditions. For standardized economic evaluation, only coal-fired generation incurs fuel costs. To address temporal variability, K-means clustering is employed to extract representative daily profiles from historical time series.

Objective Function

The objective of the proposed planning model is to minimize the total cost over the planning horizon, as defined in Equation (1). This total cost consists of the investment cost , given in Equation (2), and the operational cost , defined in Equation (3). The operational cost includes generation costs, carbon emission penalties, demand response expenditures, and penalties associated with wind and solar curtailment, as well as load shedding under uncertainty.

In the model, subscripts , , , , and represent thermal units, renewable generators, loads, storage systems, representative days, and time periods, respectively.

Investment Constraints for Infrastructure Deployment

The investment-related constraints include the investment cost constraint, as defined in Equation (4). In addition, Equations (5) and (6) impose limits on the rated power and energy capacity of the storage systems, respectively.

In the equations, denotes the upper limit of total investment cost. and denote the rated power and energy capacity of LDES, respectively, while refers to the required continuous discharge duration of the storage system.

System Operation Constraints

Equation (7) enforces nodal power balance by requiring that the total power inflow equals the total outflow at each node.

Equations (8) and (9) impose power flow constraints on candidate transmission lines, ensuring that the transmitted power remains within rated capacity limits. In addition, Equation (10) constrains the nodal voltage angles within allowable bounds to ensure the feasibility of DC power flow modeling.

The operational constraints for conventional generating units include generation capacity limits, as defined in Equation (11), minimum up and down time requirements, as described in Equations (12) and (13), and ramping limits for thermal units, given in Equation (14). The operational constraints for hydropower units follow a similar formulation and are omitted here for brevity.

Equation (15) ensures that the storage system cannot charge and discharge simultaneously. Equations (16) and (17) set the upper bounds on charging and discharging power, respectively. Equations (18) and (19) constrain the energy stored within the system to remain within its rated capacity. Finally, Equation (20) ensures that the state of charge (SoC) at the end of the scheduling horizon is no less than the initial SoC, thereby maintaining energy continuity across planning cycles.

To address the uncertainty in renewable energy outputs and ensure reliable system operation, this study adopts a robust optimization approach in which wind and solar generation are represented by uncertainty sets. Equation (21) defines the uncertainty set for the per-unit output of renewable generators. Based on this formulation, Equation (22) imposes generation constraints that ensure renewable outputs remain within feasible bounds for all realizations within the defined uncertainty set.

2.2.2. Solution Algorithm

However, unlike thermal power units with long start-up and shut-down times, LDESs are capable of rapidly transitioning between charging and discharging states. Consequently, when contemplating the switching of LDESs to mitigate operational uncertainties, this gives rise to a multitude of binary variables in the second-stage subproblem, thereby precluding direct dual transformations or Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) transformations. It thus follows that the traditional Column-and-Constraint generation (C&CG) algorithm is no longer applicable for solving the model presented in this paper. In order to address this issue, this paper proposes an improved C&CG algorithm. The introduction of auxiliary variables in the second-stage sub-problem allows for the dual transformation of the subproblem to be achieved, thus avoiding the inner C&CG loop for handling binary variables in the sub-problem. The improved C&CG algorithm decomposes the original problem into a master problem and a subproblem for solution. The specific solution process is outlined in Appendix A [33].

2.3. A Cost Allocation Mechanism for LDES Considering System-Level Externality Value

This subsection formulates a cost allocation mechanism for LDES based on the Nash bargaining framework. Existing cooperative investment models often rely on equal-sharing rules or predefined contractual arrangements, which fail to capture the heterogeneity in benefit distribution among stakeholders. In practical power systems, the integration of LDES brings differentiated external benefits to multiple entities, including renewable energy producers, transmission system operators, and electricity consumers. These benefits include enhanced system flexibility, improved renewable energy integration, and mitigation of peak-load stress. Therefore, a rational cost allocation principle should reflect the notion that stakeholders who derive greater benefits from LDES should bear a proportionally larger share of its deployment cost.

To this end, an asymmetric Nash bargaining model is proposed, which incorporates the relative benefit or contribution of each stakeholder. The cost allocation problem is formulated as a Nash product maximization model, reflecting the negotiation power and benefit heterogeneity among participants.

Subject to:

The objective function in Equation (23) adopts a Cobb–Douglas utility formulation, which captures the cooperative surplus generated by LDES deployment and allocates it among stakeholders based on their respective bargaining weights. Equation (25) defines the disagreement point, representing the baseline operational cost incurred by the power system in the absence of LDES, and serves as the reference point for surplus distribution in the bargaining process. With the disagreement point defined in Equation (25), the resulting asymmetric Nash bargaining outcome satisfies individual rationality, meaning that no stakeholder is worse off than under the no-LDES baseline. Moreover, after the logarithmic transformation, the Nash objective is strictly concave under standard conditions, which ensures a unique Pareto-efficient allocation for given bargaining weights.

Costs are allocated among stakeholders based on their respective benefit shares, derived from the optimal dispatch results under LDES participation. This approach adheres to the benefit-based cost allocation principle and internalizes the external value of LDES within a market-compatible bargaining framework. Ultimately, the proposed mechanism supports the functional deployment of LDES as a system-level flexibility resource, contributing to enhanced long-term grid security and operational resilience.

For the proposed model, an analytical solution can be obtained through precise mathematical derivation. The derivation proceeds as follows:

(a) Although the original formulation exhibits nonconvex characteristics that hinder direct optimization, a logarithmic transformation preserves the problem’s convexity and reformulates it into a mathematically tractable structure. By leveraging the concavity of the logarithmic utility function and its additive separability across stakeholders, the transformed objective satisfies the regularity conditions required for the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) framework. As a result, the optimization problem meets the criteria for convex programming, ensuring both the existence and uniqueness of the optimal solution under standard convexity theory.

(b) The Lagrange function can be defined as follows:

and in (27) represent the Lagrange multipliers associated with constraints (23) and (25). To derive the optimality conditions for the optimization problem defined by objective function, the KKT conditions are obtained by computing the gradient of the Lagrangian function with respect to all decision variables.

where , = 0 can be obtained from complementary relaxation conditions (28), and it can be substituted into Equation (29).

From the above derivation, we can finally obtain the following result:

The cost allocation in (30) comprises two parts: the no-LDES baseline operating cost (reference and disagreement benchmark) and the marginal externality value created by LDES, which captures stakeholder-specific incremental benefits from flexibility, renewable integration, and stress relief. Accordingly, the proposed framework recovers the LDES configuration cost in proportion to each stakeholder’s externality-driven value relative to the baseline, aligning payments with realized security and flexibility contributions. As shown in Table 1, most existing allocation principles focus on service-level operational payments, hierarchical incentives, or single-mechanism charges and do not explicitly embed a no-LDES disagreement baseline for investment cost recovery under widely shared externalities. By contrast, the asymmetric Nash bargaining used here fits quasi-public LDES procurement by enabling benefit-consistent and economically grounded cost sharing anchored to the baseline.

Table 1.

Comparison for different cost allocation methods.

3. Results and Discussions

A case study is conducted on a modified 5-bus system to demonstrate the externality value of LDES for system’s operation. In this setting, each bus represents an aggregated region, incorporating its local thermal generation capacity, renewable energy capacity, and electricity demand profile (with a maximum load of 164,000 MW). Inter-regional transmission corridors are modeled as a limited set of representative lines by aggregating physical interconnections, while preserving the network’s topological structure and transfer capabilities. This network-constrained testbed is sufficient for externality valuation and stakeholder benefit decomposition, and the proposed workflow is directly extendable to larger networks. The details are shown in Table 2, where D1–D5 denote the five aggregated regional power grids in Northwest China, each represented by one bus in the modified 5-bus system. Specifically, the planning model considers 4 energy storage systems for deployment. Other relevant parameters of the planning model are summarized in Table 3 [33,34]. The proposed transmission expansion model is solved using the YALMIP toolbox, with typical days identified by the posteriori scenario aggregation method and a 1 h simulation interval.

Table 2.

Regional Power Boundary.

Table 3.

Parameter Setting.

3.1. Effect of LDESs in the Power System Operation

To evaluate the externality value of long-duration energy storage (LDES), a comparative analysis is conducted with storage capacity as the core decision variable. System-level cost components are disaggregated according to stakeholder responsibility, including thermal generation costs (assigned to thermal operators), renewable curtailment penalties (borne by renewable operators), load shedding costs (incurred by grid operators), and variations in nodal marginal prices (reflected in end-user expenditures). All simulations are performed with a 1 h time step in MATLAB 2023a using YALMIP, and the resulting mixed-integer programs are solved with Gurobi (v11.0.1). The improved C&CG algorithm adopts a master-problem relative MIP gap of 0.001 and terminates when the worst-case recourse cost satisfies ; in the reported case study, it converges in one outer iteration () with a total runtime of 779.69 s on an Intel Core i9-14900KF CPU using 24 threads.

3.1.1. System-Level Benefits of LDESs in Power System Operation

To systematically evaluate the operational impacts of LDES, two configurations are compared: one without storage and one with storage. The analysis includes both system-level and user-level perspectives, focusing on thermal generation costs, carbon emission penalties, renewable curtailment costs, load shedding, and electricity expenditures by end-users. To fully capture the trade-off between costs and benefits, the investment cost associated with LDES deployment is also considered. A summary of the evaluation results is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

System Operational Costs Under Scenarios With and Without Energy Storage.

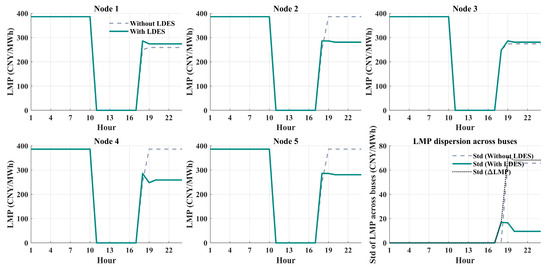

Compared with the deployment without storage, the inclusion of LDES resulted in a significant improvement in overall system performance. The total thermal generation cost was reduced by approximately 3.92%, carbon emission penalties decreased by 5.59%, and renewable curtailment policy expenditures declined by 7.07%. Moreover, load shedding events were completely eliminated, indicating enhanced system adequacy and flexibility. Although the deployment of LDES introduced a moderate investment cost, its share in the total system cost remained relatively small compared with the operational and environmental benefits achieved. From the end-user perspective, the integration of LDES resulted in a noticeable reduction in electricity expenditures, with industrial users experiencing an average cost decrease of 5.3 percent and residential consumers benefiting from a 2.7% reduction. As illustrated in Figure 2, the presence of storage effectively stabilized nodal electricity prices by mitigating peak and valley fluctuations. This contributed to improved price fairness and reduced user exposure to price volatility. These effects are primarily attributed to the time-shifting and peak-shaving capabilities of LDES, which help balance power supply and demand across both temporal and spatial dimensions.

Figure 2.

System-wide LMP Impacts of Long-Duration Energy Storage.

Overall, the deployment of LDES provides multi-dimensional benefits, including improved operational efficiency, enhanced carbon mitigation, greater renewable energy integration, and increased end-user welfare. These results confirm that appropriately sized storage capacity is essential for achieving coordinated economic, environmental, and social objectives. The findings reinforce the role of LDES as a key flexibility resource in future low-carbon power systems.

3.1.2. Results for Cost Allocation

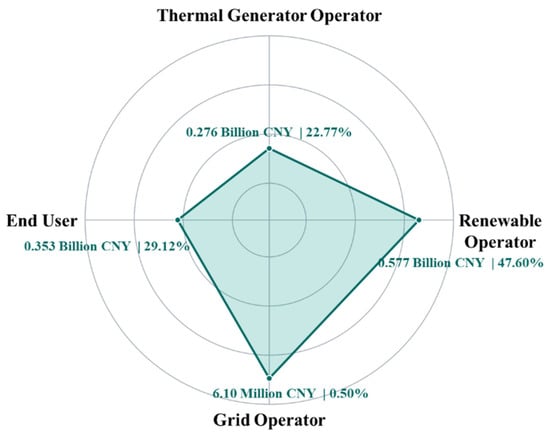

To internalize the external benefits provided by LDES and encourage equitable investment participation, a cost allocation strategy based on the Nash bargaining framework is employed. This approach follows the principle that stakeholders who benefit from system-level enhancements should proportionally share the costs. The cost savings enabled by LDES deployment are first quantified for each stakeholder. Thermal power producers benefit from lower fuel consumption and reduced carbon emissions, while renewable energy developers face fewer curtailment penalties. Transmission operators gain improved system adequacy by avoiding involuntary load shedding, and electricity consumers experience reduced expenditures due to stabilized nodal prices. These distributed benefits establish a strong economic rationale for multi-party investment and cost sharing in LDES.

The cost allocation results obtained from the Nash bargaining framework are illustrated in Figure 3, indicating each stakeholder’s proportional contribution to the total investment in LDES, commensurate with the benefits they receive. Renewable energy developers assume the largest share, contributing approximately 46.9% of the total cost, primarily due to significant reductions in curtailment-related penalties. End users are allocated around 28.7%, reflecting measurable savings from improved supply reliability and lower nodal marginal prices. Thermal power producers account for 22.4%, aligned with their operational cost reductions from improved dispatch efficiency and decreased carbon penalties. Grid operators contribute the remaining 0.5%, corresponding to modest but non-negligible benefits from enhanced system adequacy and the elimination of involuntary load shedding.

Figure 3.

Stakeholder Shares of LDES Investment.

This allocation result confirms the validity and practicality of the proposed benefit-based mechanism. By explicitly linking each stakeholder’s investment share to their corresponding economic gains, the model ensures fairness, economic efficiency, and strong incentive alignment. It provides a solid foundation for promoting collaborative deployment of long-duration energy storage in future multi-agent power systems.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis on Storage Capacity Scaling

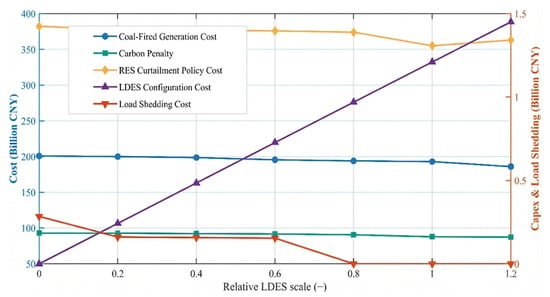

To examine the relationship between storage capacity and its system-level externality value, a parametric analysis was conducted by incrementally scaling the optimal storage configuration from zero to 1.2 times, using a step size of 0.2. At each capacity level, key system performance indicators were evaluated, including thermal generation cost, carbon emission penalties, renewable energy curtailment, load shedding, and the volatility of nodal marginal prices. This analysis enables a comprehensive understanding of how varying storage scales influence overall system performance.

3.2.1. System Externality Under Varying Storage Capacity

A sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying the configured capacity of LDES from zero to 1.2 times the optimal level. At each step, key indicators of system-level externalities were evaluated, including thermal generation cost, carbon emission penalties, renewable curtailment costs, and load shedding. The results, shown in Figure 4, illustrate the evolving impacts of different storage deployment levels on system performance.

Figure 4.

Cost Decomposition Under Varying LDES Deployment Levels.

As shown in Figure 4, increasing storage capacity up to 80% of the optimal level led to sustained improvements in system performance. Thermal generation costs declined steadily, carbon emission penalties were reduced, and curtailment-related expenditures decreased significantly. Notably, load shedding was fully eliminated at this capacity level, indicating enhanced system adequacy and operational flexibility. These improvements are attributed to the ability of long-duration energy storage to absorb excess renewable generation and relieve peak demand. However, beyond the optimal configuration, marginal benefits diminished. At 120% capacity, investment increased by nearly 20%, yet key indicators such as curtailment cost and carbon penalties showed negligible improvement. This suggests underutilization of excess storage capacity due to surplus flexibility and limited renewable oversupply, resulting in reduced capital efficiency.

Overall, the externality value of LDES exhibits high sensitivity to the scale of deployment. Moderate storage configurations yield the most cost-effective enhancements in system performance by balancing flexibility and investment efficiency. In contrast, overinvestment results in diminishing marginal returns, primarily due to underutilized capacity and constrained renewable surplus. These findings underscore the critical importance of appropriately sizing storage systems to fully realize their externality-mitigating potential while avoiding economic inefficiency.

3.2.2. Impact on Cost Allocation Results

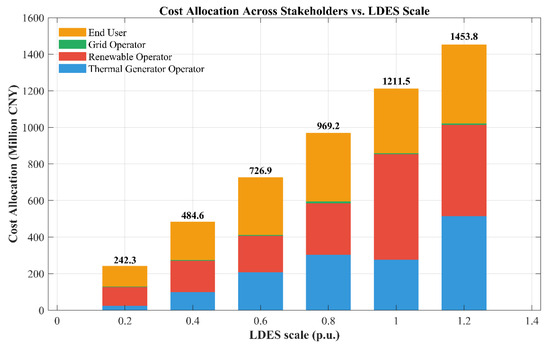

To evaluate how storage investment burdens shift under varying deployment scales, a series of cost allocation simulations based on the Nash bargaining framework were conducted for storage configurations ranging from 20% to 120% of the optimal capacity. For each scenario, the externality benefits accrued by four stakeholder groups—thermal producers, renewable energy operators, grid operators, and end-users—were quantified. These quantified gains were then used to proportionally allocate the total investment cost of LDES. The resulting distribution outcomes are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Cost Allocation with Increasing Long-Duration Storage Deployment.

The results reveal several notable patterns. Under low-capacity configurations, such as 20% of the optimal level, end users bore the largest portion of the storage investment cost, reaching 46.8%. This reflects their early-stage benefits from reduced electricity prices and improved supply reliability. As capacity approached the optimal level, the distribution of cost became more balanced. At the optimal configuration, renewable energy operators assumed the highest share at 47.6%, driven by significant reductions in curtailment-related penalties, while the share assigned to end users decreased to 29.1%. The cost burden for thermal producers followed a non-monotonic trend, peaking at 31.2% under the 80% deployment and declining thereafter. In the scenario of overinvestment, where storage capacity reached 120% of the optimal level, thermal and renewable operators contributed nearly equal shares, and the proportion borne by end users remained relatively stable. These shifts reflect the evolving structure of marginal benefits across stakeholders, as the role of storage transitions from enhancing price stability and reliability to improving renewable energy integration and dispatch efficiency.

These findings demonstrate that the distribution of storage investment responsibility is both dynamic and dependent on the scale of deployment. During the initial stages of storage integration, end-users derive the most immediate benefits and therefore bear a higher proportion of the investment cost. As the deployment scale approaches the optimal configuration, system-wide flexibility increases and the value captured by renewable and thermal power producers becomes more pronounced, leading to a larger share of the investment being allocated to these stakeholders. When the storage capacity exceeds the optimal level, the marginal benefits realized by each stakeholder begin to level off, resulting in a more balanced cost distribution. The application of the Nash bargaining framework effectively accommodates these shifts, ensuring that cost allocation remains fair and aligned with realized benefits across varying planning scenarios. This adaptability underscores the suitability of the framework for coordinating multi-agent investment decisions in future energy systems.

3.3. Storage Cost Redistribution Based on User Benefit Differentiation

To improve the precision of storage investment cost allocation on the demand side, user benefits are differentiated along two dimensions, namely network location and industry sector. Different from the aggregated user representation in the preceding stakeholder-level analysis, end-user impacts are decomposed into (i) node-specific electricity-expenditure changes across representative buses and (ii) sectoral benefit shares relative to electricity-consumption shares.

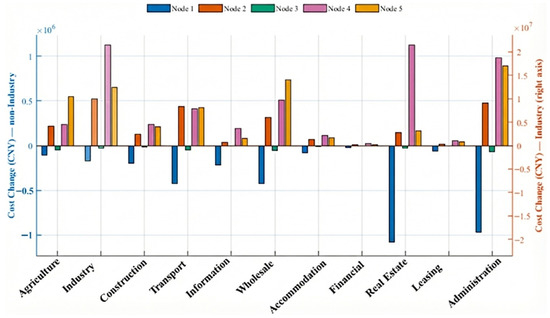

3.3.1. Locational Differentiation of User Benefits from LDESs

In this subsection, a detailed locational analysis is conducted to evaluate how the deployment of LDES influences user-side economic benefits across different network nodes. By comparing electricity expenditures before and after storage integration, the nodal distribution of user benefits is quantified for eleven industry sectors across five representative nodes. These benefits encompass reductions in electricity costs, improvements in supply reliability through the mitigation of load curtailment, and decreased exposure to price volatility at the nodal level. The results, summarized in Figure 6, highlight the spatial heterogeneity of user-side benefits under the optimized storage deployment.

Figure 6.

Sectoral Electricity-Cost Changes by Node.

As shown in Figure 6, the distribution of user-side benefits is markedly non-uniform across the network. The dominant reductions in electricity expenditure are concentrated at Nodes 2, 4, and 5, whereas Nodes 1 and 3 exhibit comparatively limited changes, including cases where increases occur for certain sectors. In terms of magnitude, the industrial sector constitutes the largest absolute component and is therefore presented on a separate scale in the figure to enable simultaneous inspection of both industrial and non-industrial sectors. Collectively, these results indicate that the user-side value of LDES is highly location-dependent and is consistent with nodal differences in price dynamics and network operating conditions under storage-integrated dispatch.

Overall, the results indicate that the externality value of long-duration energy storage is not uniformly distributed across the power network, but rather exhibits significant spatial variation. Nodes characterized by high renewable curtailment potential and severe grid congestion derive greater operational benefits from storage deployment. This highlights the importance of implementing a location-sensitive cost allocation mechanism to ensure fairness and efficiency in investment decisions. Integrating locational marginal savings into system planning and pricing frameworks can help align investment responsibilities with realized benefits. Such an approach encourages users who gain the most from storage deployment to contribute proportionally to its costs, thereby enhancing both economic equity and system-wide performance.

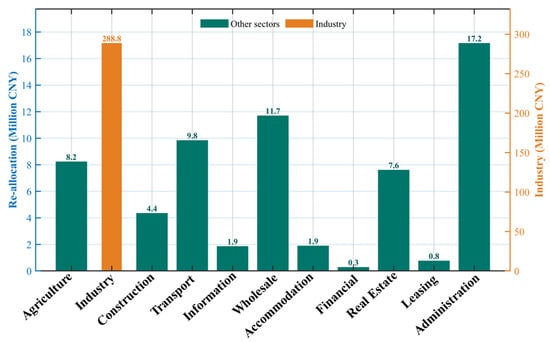

3.3.2. Industrial Differentiation of User Benefits from LDESs

In this subsection, we analyze the redistribution of storage-related economic benefits across various industry sectors. Drawing on the nodal-level simulation results, we aggregated the revenue associated with long-duration energy storage participation for eleven representative sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing, transportation, construction, real estate, and public services. For each sector, we computed its share of the total storage-derived benefit alongside its corresponding share of electricity consumption. The comparative outcomes are visualized in Figure 7, providing insights into the alignment between sectoral benefits and electricity usage patterns.

Figure 7.

Nash-Based Reallocation of Consumer Benefits by Sector after LDES.

Figure 7 shows that the industrial sector captures 88.78% of the storage-related user benefit while accounting for 70.67% of total electricity consumption, corresponding to a benefit-to-load index of approximately 1.26. This indicates that industrial demand, on average, extracts above-proportional value from LDES deployment. By contrast, several non-industrial sectors receive benefit shares that are below their load shares, suggesting that storage value capture is shaped by the temporal profile of consumption and its interaction with nodal price patterns rather than by energy volume alone. In particular, LDES reshapes the locational marginal price trajectories in both time and space, thereby redistributing the economic gains across sectors with different load timing characteristics.

In summary, the analysis reveals that the benefits brought by storage deployment vary significantly across industry sectors. The ratio of benefit to electricity load is closely linked to the temporal flexibility of energy usage and the responsiveness of consumption to price signals. These results emphasize the necessity of accounting for sector-specific characteristics when formulating equitable and efficiency-oriented mechanisms for cost recovery or subsidy allocation in future power system planning.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents a novel cost allocation framework for LDES from the perspective of a public asset, aiming to address both equity and efficiency challenges associated with large-scale storage deployment in future low-carbon power systems. By incorporating a Nash bargaining mechanism, the model captures the stakeholder-specific externality values of LDES across a range of storage capacity scenarios. To enhance the granularity of cost redistribution, the framework further integrates industry-level demand segmentation and node-level user benefit analysis, thereby improving spatial and sectoral fairness.

Simulation results under varying storage configurations reveal the nonlinear and heterogeneous nature of externality benefits across stakeholders. At low storage levels, end users emerge as the primary beneficiaries due to early-stage improvements in reliability and price stability. As capacity increases toward the near-optimal configuration, renewable and thermal producers obtain larger benefit shares, reflecting reduced curtailment penalties and operating costs. When storage becomes oversized, marginal benefits diminish, resulting in a more balanced but less economically efficient distribution of investment responsibility. In addition, sectoral analysis indicates that although industrial consumers capture most absolute benefits due to large electricity demand, public-service and commercial sectors exhibit higher benefit-to-load ratios, highlighting potential for differentiated demand-side participation.

Overall, the proposed framework offers a scalable and equitable solution for allocating LDES investment costs in future grid planning. By aligning cost responsibility with realized system-level benefits, the model supports more socially acceptable and economically efficient integration of storage resources, ultimately enhancing power system flexibility and advancing the energy transition toward deep decarbonization. From a policy perspective, treating LDES as a public asset helps internalize system-wide externalities and motivates structured beneficiary-based cost recovery when merchant revenues alone are insufficient.

5. Limitations and Future Work

Despite the methodological contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the case study is based on an aggregated 5-bus test system, which supports mechanism-level insights but may not fully represent large-scale system complexity. Future work will extend the proposed framework to more realistic regional or national-level power systems with higher spatial granularity and operational diversity. Second, key assumptions and parameters, such as storage efficiency, capital cost, discount rate, renewable penetration, and carbon price, may affect valuation and allocation outcomes; further sensitivity and robustness analyses are needed to quantify uncertainty ranges. Third, future research will compare the asymmetric Nash bargaining mechanism with alternative allocation principles, such as Shapley value and welfare-based schemes, and investigate bargaining power calibration under different stakeholder structures and regulatory settings. Finally, incorporating richer market dynamics and empirical validation will further enhance the practical relevance of treating LDES as public infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L.; validation, Y.H. and R.H.; formal analysis, Z.L. and R.H.; investigation, H.W.; resources, Y.H.; data curation, Y.H. and Z.L.; writing—original draft, H.W. and Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.L., J.L. and R.H.; visualization, Z.L. and R.H.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the The scientific and technological project of Inner Mongolia Electric Power Trading Center Co., LTD., “Research on the Mechanism of Pumped Storage Participating in the Electricity Market” (202501) and Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation under Grant (2025MS05012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hao Wang, Yue Han and Zhongchun Li were employed by the company “Inner Mongolia Power Trading Center Co., Ltd., Hohhot”. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| A. Sets | |

| Set of the time slots | |

| Set of the thermal generation | |

| Set of the renewable generation | |

| Set of the energy storages | |

| Set of transmission lines | |

| Set of electric loads | |

| B. Parameters | |

| Equipment lifetime | |

| Unit investment costs | |

| Interruptible workloads originally scheduled | |

| Maximum allowable execution delay | |

| Probability of representative days | |

| Cost coefficient | |

| Power demand of electric loads | |

| Upper/lower limits of voltage angle | |

| Reactance of transmission line | |

| Large relax constant | |

| Upper/lower limits of thermal generation | |

| Minimum up/down time requirement | |

| Ramp up/down limits of thermal generation | |

| Charging/discharging efficiency | |

| Installed capacity of renewable generation | |

| Upper/lower limits of forecast error | |

| Time-based uncertainty budget | |

| C. Variable | |

| Investment status of storage units | |

| Output of thermal generation | |

| Carbon emission | |

| Uncertain output of renewable generation | |

| Realized output of renewable generation | |

| Amount of load shedding | |

| Power flow on transmission line | |

| Charging power of the LDESs | |

| Discharging power of the LDESs | |

| Voltage angle | |

| On/off status of thermal units | |

| Number of consecutive time steps | |

| Charging/discharging status of LDESs | |

| Stored energy level of LDESs | |

| Uncertain output of renewable unit | |

| D. Abbreviation | |

| LDES | Long-duration energy storage |

| LCOS | Levelized cost of storage |

| SABO | Subtraction-average-based optimization |

| SoC | Status of charging |

| C&CG | Column-and-Constraint generation algorithm |

| KKT | Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions |

Appendix A. Improved C&CG Algorithm

Unlike thermal units with slow start-up/shut-down dynamics, LDES can switch rapidly between charging and discharging. Modeling such switching decisions under uncertainty introduces many binary variables in the second-stage subproblem, which prevents applying standard dual or KKT-based reformulations. Therefore, the conventional C&CG algorithm is not directly applicable. To resolve this issue, this paper develops an improved C&CG scheme that introduces auxiliary variables to enable a valid dual reformulation of the subproblem, thereby avoiding an inner C&CG loop for handling binary decisions. The resulting algorithm decomposes the model into a master problem and a subproblem, as summarized in Algorithm A1.

| Algorithm A1: Improved C&CG Algorithm | |

| Initialization: | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | Set lower bound LB = 0 |

| 3 | |

| 4 | Define convergence criterion , |

| Main Loop: | |

| 1 | do |

| 2 | k = k + 1 |

| 3 | of the master problem |

| 4 | then |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | End if |

| 8 | Solve second-stage recourse sub problem: |

| 9 | For do |

| 10 | Introduce auxiliary variables, transform subproblem (A3) to a single-layer max problem |

| 11 | Solve dual of subproblem (A8) |

| 12 | and worst scenario |

| 13 | |

| 14 | End for |

| 15 | then |

| 16 | Terminate algorithm |

| 17 | else |

| 18 | Generate C&CG constraint and add to master problem |

| 19 | For each scenario r and time t do |

| 20 | Generate C&CG constraint form worst scenario and add to master problem |

| 21 | End for |

| 22 | End if |

| 23 | End while |

References

- Staadecker, M.; Szinai, J.; Sánchez-Pérez, P.A.; Kurtz, S.; Hidalgo-Gonzalez, P. The value of long-duration energy storage under various grid conditions in a zero-emissions future. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, C.; Wu, Z. Reinforcement learning-based time of use pricing design toward distributed energy integration in low carbon power system. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yang, Z.; Duan, Y. Short-and long-duration cooperative energy storage system: Optimizing sizing and comparing rule-based strategies. Energy 2023, 281, 128273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wei, L.; Yang, L.; Yuan, B.; Zhou, M. Understanding the synergy of energy storage and renewables in decarbonization via random forest-based explainable AI. Appl. Energy 2025, 390, 125891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twitchell, J.; DeSomber, K.; Bhatnagar, D. Defining long duration energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 60, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, A.; Sciacovelli, A. Long-duration thermo-mechanical energy storage–present and future techno-economic competitiveness. Appl. Energy 2023, 334, 120628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, C. Capacity configuration optimization of photovoltaic-battery-electrolysis hybrid system for hydrogen generation considering dynamic efficiency and cost learning. Energy Convers. Econ. 2024, 5, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Hong, H.; Tseng, C.L.; Wen, F.; Wu, Q.; Shahnia, F. Economic dispatch of CAES in an integrated energy system with cooling, heating, and electricity supplies. Energy Convers. Econ. 2023, 4, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, W.; Denholm, P.; Carag, V.; Frazier, W. The peaking potential of long-duration energy storage in the United States power system. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Duan, Y. Evaluation of the short-and long-duration energy storage requirements in solar-wind hybrid systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 314, 118635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yang, D.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H. The role of short-and long-duration energy storage in reducing the cost of firm photovoltaic generation. Appl. Energy 2024, 374, 123914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De León, C.M.; Ríos, C.; Molina, P.; Brey, J.J. Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) for a hydrogen system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Gao, H. Distributed source-load-storage cooperative low-carbon scheduling strategy considering vehicle-to-grid aggregators. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, M.; Baker, K.; Crozier, C. Spatial arbitrage through bidirectional electric vehicle charging with delivery fleets. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.; Mao, L.; Qu, K.; Li, F. Optimal sizing for a wind-photovoltaic-hydrogen hybrid system considering levelized cost of storage and source-load interaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 4129–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghumayjan, S.; Han, J.; Zheng, N.; Yi, M.; Xu, B. Energy storage arbitrage in two-settlement markets: A transformer-based approach. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 235, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhor, A.; Basem, A.; Dara, R.N.; Shaban, M.; Ghandour, R.; Al Barakeh, Z.; Abduvalieva, D.; Alkhalaf, S.; Bayhan, Z.; Ali, H.E. Integrated solar energy-energy storage system for an electricity-freshwater multigeneration configuration: Exergo-economic assessment with multi-objective particle swarm optimization. J. Energy Storage 2025, 122, 116750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimon, M. Renewable energy curtailment: A problem or an opportunity? Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Tian, W.; Gao, G.; Yao, P.; Xin, C.; Cui, W. Day-ahead scheduling model for high-penetration renewable energy power system considering energy storage for auxiliary peak shaving and frequency regulation. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 50480–50492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, T.; Bistline, J.; Sioshansi, R.; Cole, W.J.; Kwon, J.; Burger, S.P.; Crabtree, G.W.; Jenkins, J.D.; O’Neil, R.; Korpås, M.; et al. Energy storage solutions to decarbonize electricity through enhanced capacity expansion modelling. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shah, A.; Keerio, M.U.; Mugheri, N.H.; Abbas, G.; Touti, E.; Hatatah, M.; Yousef, A.; Bouzguenda, M. Multi-objective security constrained unit commitment via hybrid evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 6698–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Sun, H.; Fu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Oren, S.S. Energy management of price-maker community energy storage by stochastic dynamic programming. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 10, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmed, S.A.; Tong, L. Dynamic Net Metering for Energy Communities. IEEE Trans. Energy Mark. Policy Regul. 2024, 2, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, N.; Xu, B. Locational energy storage bid bounds for facilitating social welfare convergence. IEEE Trans. Energy Mark. Policy Regul. 2025, 3, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, M.; Yuan, B. Capacity expansion model for multi-temporal energy storage in renewable energy base considering various transmission utilization rates. J. Energy Storage 2024, 98, 113145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarros, G.N.; Dratsas, P.A.; Chinaris, P.P.; Papathanassiou, S.A. Assessing the implications of RES technology mix on curtailments, storage requirements and system economics. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.P.; Rodilla, P.; Mastropietro, P. Efficient cost allocation in capacity remuneration mechanisms: Applying cost causation to resource adequacy. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 173, 111441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matamala, C.; Badesa, L.; Moreno, R.; Strbac, G. Cost Allocation for Inertia and Frequency Response Ancillary Services. IEEE Trans. Energy Mark. Policy Regul. 2024, 2, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, H.; Xiang, Y.; Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, J. Coordinated Generation Scheduling Considering Peak Regulation Cost Allocation and Compensation Distribution in Power Systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 13, 1921–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, Y.; Tan, Z.; Xing, D.; Tan, C. Optimal dispatch and cost allocation model for combined peak shaving of source-load-storage under high percentage penetration of renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2025, 225, 123845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Wu, M.; Zhuo, K. Innovative Cost Allocation and Energy Management in Off-Grid Microgrids via Stackelberg Game. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 21387–21399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ge, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Long, H.; Luo, X. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Cooperative Optimal Operation for Building Integrated Energy Systems With Nash–Harsanyi Bargaining Game-Driven Cost Allocation. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 4759–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Z.; Liu, S.; Guo, Z.; Li, G. A Frequency Security Constrained Scheduling Approach Considering Wind Farm Providing Frequency Support and Reserve. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 1086–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lv, J.; McElroy, M.B.; Han, X.; Nielsen, C.P.; Wen, J. Power System Capacity Expansion Under Higher Penetration of Renewables Considering Flexibility Constraints and Low Carbon Policies. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 6240–6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.