1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is undergoing a paradigm shift in sports applications, where techniques like performance analysis, training optimization, and decision support systems are increasingly being utilized. AI techniques such as machine learning, computer vision, and pattern recognition are utilized to analyze athlete movements, classify sports activities, and provide personalized training strategies [

1,

2]. The utilization of image processing and video analysis tools, such as Coach’s Eye and Dartfish, has been validated to enhance skill assessment and feedback [

3]. Recent innovations in sports analytics include AI-driven systems that enhance refereeing accuracy and enable precise injury prediction [

4]. In weight training, AI applications have shown promising results in evaluating exercise techniques [

5]. However, challenges persist in data collection, AI controllability, and result interpretability [

1]. Despite these challenges, AI holds significant potential for biomechanical analysis and performance optimization [

6,

7].

AI-based feedback systems have shown promise in improving user motivation and adherence compared to traditional methods. Studies indicate that AI feedback enhances movement accuracy, balance, and health outcomes in older adults practicing tai chi [

8]. Computerized feedback systems have been found to increase adherence to exercise regimes and reduce dropout rates [

9]. Real-time AI-assisted posture correction has been shown to improve exercise technique [

10], while AI-generated personalized fitness regimes have the potential to improve physical and mental well-being [

11]. Pose prediction-based feedback has been demonstrated to enhance motivation and performance in home-based exercises [

12]. AI-driven personalization of social comparison goals has demonstrated small to moderate effects on increasing physical activity motivation [

13]. Furthermore, the integration of behavior change techniques into AI fitness applications has been identified as crucial to encourage user engagement and facilitate behavior change [

14].

This study examines the effectiveness of three attention-enhanced deep learning architectures—LSTM, GRU, and Transformer—for improving the accuracy of self-guided exercise execution. Grounded in the premise that recurrent networks encode temporal continuity and phase transitions more explicitly than purely self-attentional models, we hypothesize that the LSTM + Attention configuration will yield superior real-time motion classification by leveraging structured memory dynamics. Our framework operationalizes this hypothesis within a pose-based temporal pipeline and benchmarks model behavior not only on average accuracy but also on stability across runs and confusion patterns among visually similar movements, thereby providing a rigorous basis for architectural comparison.

Beyond predictive performance, the work targets a central challenge in autonomous physical training: mitigating injury risk stemming from improper technique. To that end, the system is designed to deliver automated, immediate feedback aligned with salient phases of each repetition, enabling users to adjust form in situ rather than retrospectively. By linking model outputs to interpretable cues (e.g., range of motion, tempo adherence, joint alignment), the approach aims to support safer and more effective practice in both athletic and everyday health contexts, while laying groundwork for personalized coaching via contextual covariates (e.g., experience level, anthropometrics) and adaptable decision thresholds.

2. Literature Review

Recent research highlights the potential of computer vision and AI in delivering real-time feedback for physical exercises, reducing reliance on human coaches. These systems leverage pose estimation algorithms like YOLOv7-pose and PoseNet to track body keypoints and analyze posture [

15,

16]. Machine learning techniques are employed to compare user performance with expert demonstrations, enabling immediate posture correction and repetition counting [

17,

18]. Some systems offer 3D reconstruction of human motion and personalized feedback based on predefined standards [

19]. These approaches show notable improvements in the safety and efficacy of activities like weightlifting, yoga, and fitness routines [

20,

21]. User studies have demonstrated positive responses to these AI-powered systems, suggesting their potential to enhance workout effectiveness and motivation, particularly in circumstances where professional guidance is unavailable [

10].

Deep learning models have demonstrated considerable potential in the domains of exercise performance assessment and injury prevention in sports. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs) demonstrate strengths in image recognition and time-series analysis for injury prediction [

22]. A hybrid CNN-BiGRU-CBAM model has achieved state-of-the-art results in recognizing sports and daily activities using wearable sensor data [

23]. Machine learning techniques such as random forests and artificial neural networks have improved injury risk assessments [

24]. Deep learning approaches have been applied to rehabilitation, including a redefined prairie dog optimized Bi-LSTM for personalized recovery plans [

25] and a Hybridized Hierarchical Deep CNN for exercise rehabilitation [

26]. Support Vector Machines have been widely used in both IMU and vision-based studies [

27]. Researchers have developed deep learning frameworks to assess rehabilitation exercises [

28] and monitor on-field player workload exposure [

29].

The potential of artificial intelligence (AI) and image processing technologies to enhance athletes’ performance through automated movement correction and feedback has been well demonstrated in numerous studies [

5,

30]. These technologies analyze sports postures with high accuracy, deliver real-time feedback, and assess exercise techniques. AI-driven systems can evaluate human body poses, support biomechanical studies, and identify technical flaws that may increase injury risk [

31]. Machine learning and deep learning techniques enable efficient data analysis, decision support, and the creation of personalized training plans [

32]. Furthermore, the integration of motion capture systems with artificial intelligence enables automated qualitative assessments by extracting movement errors from kinematic data [

33]. In addition, the combination of wearable technologies with artificial intelligence has been shown to process physiological and kinematic data, for performance optimization and injury prediction [

34]. Furthermore, neural network-based systems have been shown to provide real-time visual feedback for the correction of inaccurate postures and motions [

35].

3. Materials and Methods

This section details the data collection process, AI model architectures, and experimental protocols designed to evaluate self-guided exercise accuracy.

3.1. Data Collection Software and Procedure

The present study focuses on the recognition of movements by artificial intelligence. In this context, software has been developed with Python 3.9 for the purpose of data collection, with the objective of creating a dataset. The software’s operational sequence is delineated as follows:

- ❖

Software Initialization: Python libraries (e.g., MediaPipe, OpenCV) and variables were initialized.

- ❖

Participant Registration: Demographic data (weight, height, gender, etc.) were collected via a GUI.

All recordings were conducted in the Sports Sciences Laboratory of Fenerbahçe University under controlled environmental conditions. At the beginning of the custom-developed software workflow, participants entered their demographic information (age, weight, height, BMI, gender, sports experience) directly into the system via a standardized GUI form. This ensured that all demographic data were collected consistently before recording. The laboratory setup was arranged to guarantee that each participant remained fully visible from head to toe during all movements.

- ❖

Camera Setup: Dual cameras (computer + tablet) were calibrated at 30 FPS.

- ❖

Exercise Selection: Participants selected exercises via keyboard inputs (e.g., “a” for squats).

- ❖

Data Acquisition: Real-time skeleton coordinates (33 landmarks) were extracted using MediaPipe [Version 0.10.10] Pose. Video recording commenced concurrently with data collection.

- ❖

Data Processing: Skeleton poses were identified, normalized, and processed to ensure data consistency.

- ❖

Exercise Completion: Participants completed the exercises, triggering the end of data acquisition. Libraries (e.g., MediaPipe, OpenCV) and variables were initialized.

- ❖

Data Storage: Normalized x/y coordinates and scores were systematically saved to Excel files.

- ❖

Software Termination: The program was properly terminated, ensuring all resources were safely released and files closed.

In the dataset, the information of the following headings is received and calculated:

ID (It increases automatically as the information of the movement number.)

Movement Name (Exercise Type)

Time (incremental time information in 0.033 s intervals)

Weight

Height

Gender

Age (Calculated with Date of Birth information)

Sports Experience (in years)

Sporting Level (Beginner/Intermediate/Advanced)

Body Mass Index calculated from weight and height information

Distance (calculated as (Actual face width × Focal length)/Face width in the image)

The estimation of distance was conducted on a single occasion at the commencement of each recording. In the present study, real-time depth compensation was not a component of the research design. It was established that, due to the standardization of all 2D pose coordinates to a [0, 1] range, minor forward–backward movements exerted negligible influence on the temporal patterns employed by the classification models. Nevertheless, the absence of real-time depth monitoring is acknowledged as a limitation and will be addressed in future work through the use of depth sensors or continuous scale tracking.

The selection of 33 anatomical landmarks is informed by the pre-defined keypoint configuration of the MediaPipe Pose model. The selection of this model was made on the basis of its provision of a lightweight, real-time inference pipeline with high temporal stability across frames, a property which is essential for synchronized dual-camera acquisition. In comparison with other pose estimators, such as OpenPose and HRNet, MediaPipe Pose exhibited superior robustness and reduced latency during the pilot tests. This renders it well-suited for laboratory data collection and temporal sequence modeling.

Unlike prior single-camera pose-based exercise datasets, this study introduces a synchronized dual-camera temporal fusion pipeline designed to reduce viewpoint dependency and improve temporal smoothness of pose trajectories. Each frame pair is time-aligned using software-based latency compensation, and the combined sequences provide more stable movement dynamics for downstream temporal modeling. This dual-view synchronized acquisition constitutes a methodological contribution beyond standard MediaPipe-based pipelines and serves as the foundation for the model comparison framework presented in later sections.

3.2. Coordinate Validation and Data Collection Process for Multi-Camera Pose Estimation

The dual-camera system consisted of a 30 FPS tablet camera and a 30 FPS computer webcam, both operating under fixed laboratory lighting. Recordings were carried out using a computer equipped with a 13th Gen Intel® Core™ i9-13900H processor (2.60 GHz) (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA)and 16 GB RAM. Cameras were positioned to ensure that the participant’s entire body—including the feet—remained fully visible in the frame. Since MediaPipe Pose extracts 33 anatomical landmarks directly from standard RGB frames, participants were not required to wear specific clothing; no occlusion or contrast issues were observed during data collection. With the prepared software, 2 cameras are activated by taking the desired information from the person who will perform the movement and calibrating with the camera. With each of the 2 cameras, 33 points of the body are shown on the screen. The movement starts by pressing the following keys on the keyboard and x and y coordinate information of 33 points are obtained from both cameras at 0.033 s intervals depending on time.

- a

Free-Weight Squat

- b

Dumbbell Biceps Curl

- c

Dumbbell Lateral Raise

- d

Standing Calf Raise

- e

Dumbbell Shoulder Press

- f

Terminating the movement

MediaPipe is a versatile framework for developing perception applications, addressing challenges in processing perceptual inputs across various devices [

36]. MediaPipe Pose, a versatile machine learning framework for pose estimation, was utilized to identify 33 specific anatomical landmarks on the human skeleton from video frames. These landmarks include anatomical points such as shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and ankles, and are detected through a neural network. Specifically, the MediaPipe Pose model was configured in Python using the mp.solutions.pose library with parameters: static_image_mode = False, model_complexity = 2, and confidence thresholds (min_detection_confidence = 0.5, min_tracking_confidence = 0.5).

A dual-camera setup (computer and tablet) captured synchronized videos simultaneously at 30 frames per second (FPS). To monitor and correct inter-camera latency, timestamps were recorded using the time.time() function in Python, and frame delays between the two cameras were computed. Although hardware-based synchronization (e.g., GPIO triggers) was not implemented in this prototype, software-based latency tracking was used to minimize temporal misalignment in post-processing.

Data were collected at intervals of 0.033 s, providing high temporal resolution. To maintain synchronization, the latency between the two cameras was calculated in real time using the formula:

where each timestamp was recorded at the moment a frame was captured.

For accurate distance estimation between the participant and the camera, focal length was calculated via a one-time calibration process using the formula:

In this study, an average adult face width of 16.0 cm was assumed as the “real width.” This approximation provided sufficient accuracy for relative distance tracking, but personal face width measurements were not conducted. For higher accuracy in future studies, we plan to compare this approach against ground-truth depth measurements using LiDAR or depth sensors.

The raw landmark coordinates were normalized to a [0, 1] scale to standardize data across varying image resolutions:

(0, 0) represents the upper left corner,

(1, 1) represents the bottom right corner.

Prior to the primary data collection phase, a preliminary coordinate validation test was conducted with three subjects to ensure the temporal stability and anatomical coherence of the 33 extracted landmarks. In this validation step, each participant performed five exercises, repeated twice. The resulting time-dependent coordinates were processed to generate stickman representations for visual inspection. This procedure confirmed that the dual-camera system produced synchronized and reliable pose trajectories suitable for subsequent large-scale data acquisition.

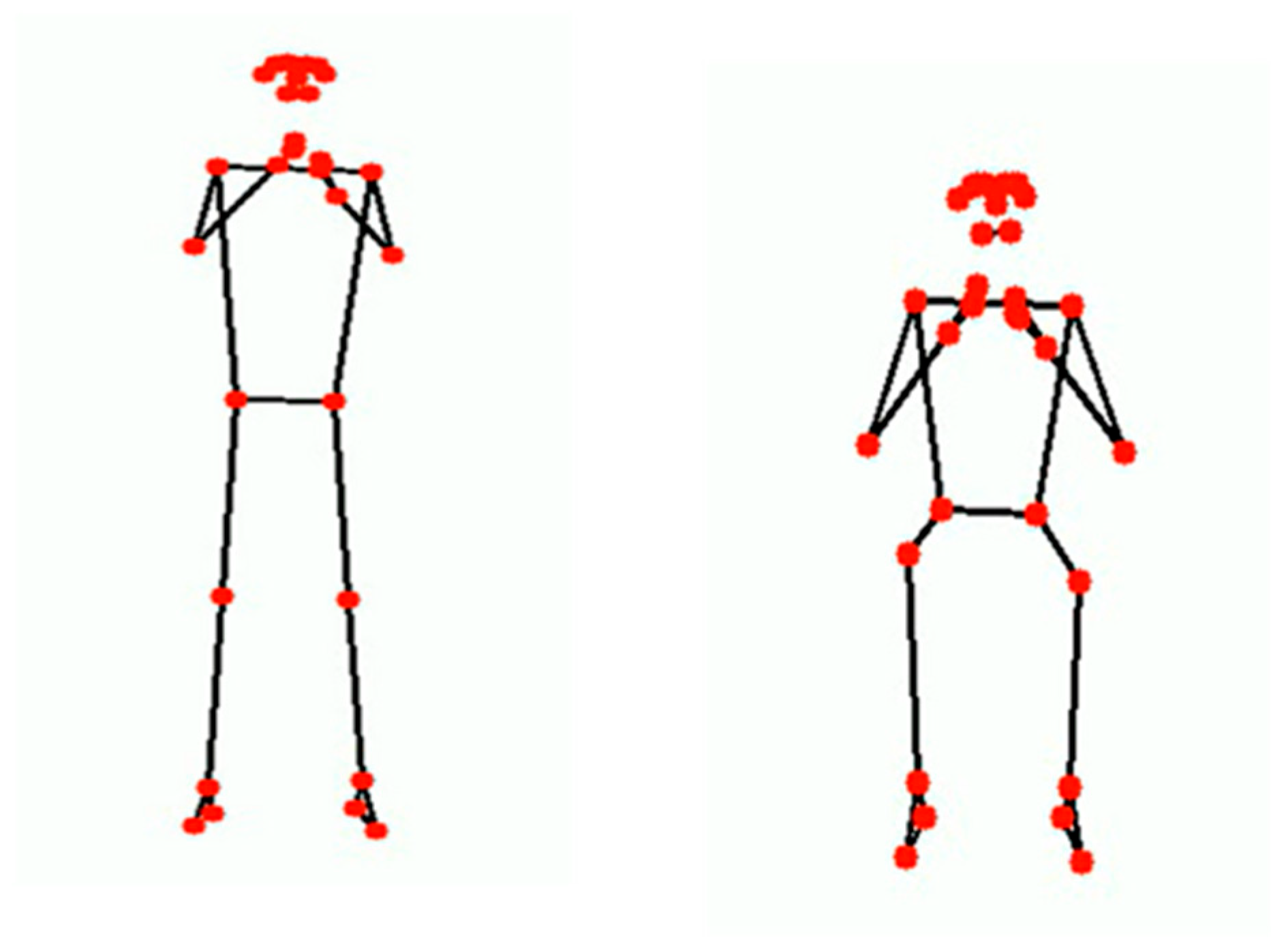

Figure 1 illustrates the output of this coordinate validation process.

After the testing of the coordinate values the data collection process started. The data collection process was carried out in a laboratory environment with a computer camera and a tablet camera taking 30 frames per second. The data collection area is shown in

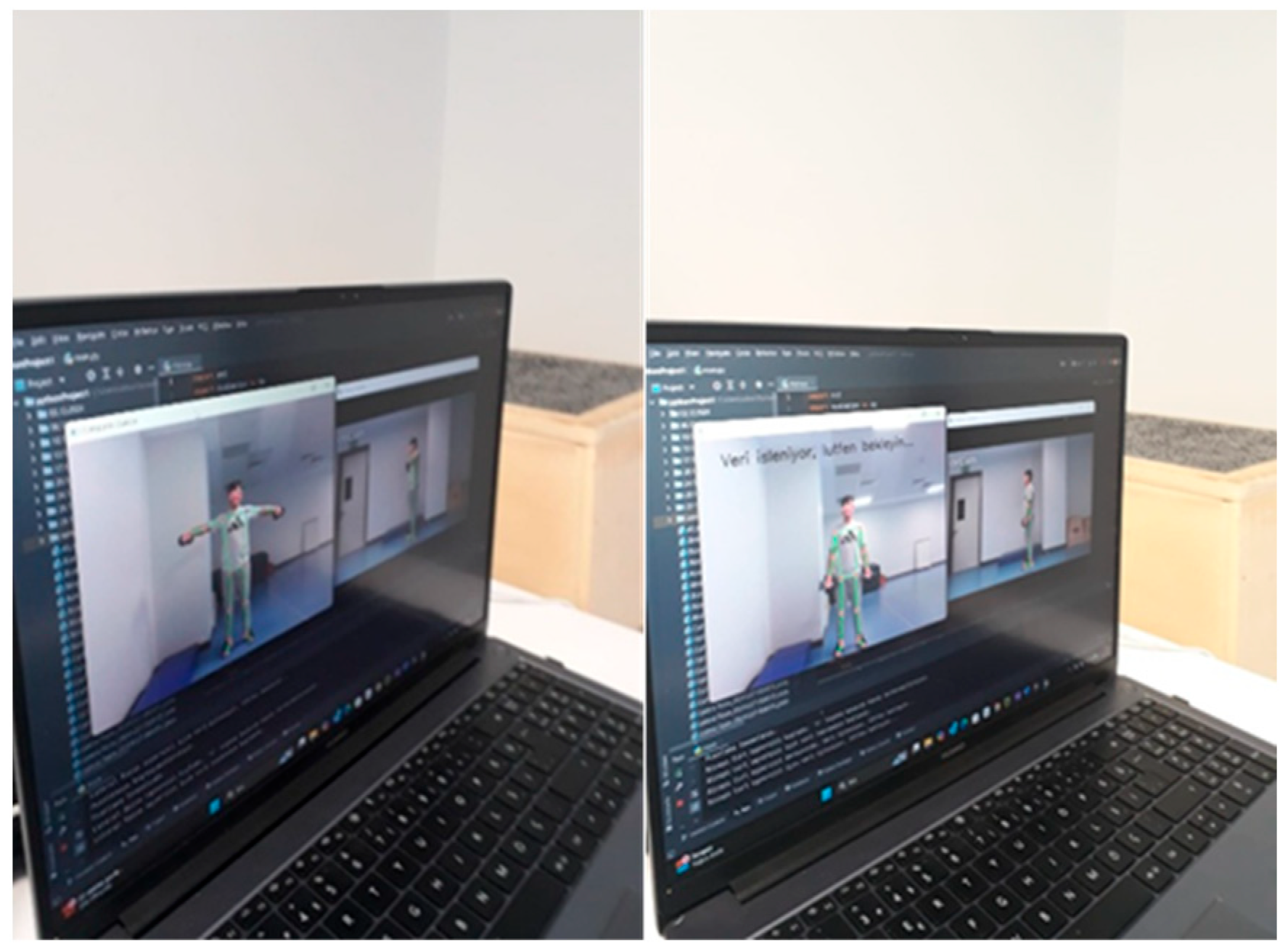

Figure 2, and the data collection software screen is shown in

Figure 3.

3.3. Model Architecture

The collected dataset was then subjected to the following time-dependent artificial intelligence algorithms, and the accuracy of predicting the movements was tested. In addition to the pose-based temporal sequences, the proposed framework integrates demographic and anthropometric features (e.g., BMI, age, gender, and training experience) through an auxiliary input branch. This design enables the model to simultaneously learn movement dynamics and user-specific physical characteristics, yielding a personalized representation space. Such demographic–pose fusion is largely underexplored in existing exercise-recognition research and constitutes a methodological contribution that extends the architecture beyond conventional pose-only classification pipelines.

LSTM with Attention Mechanism

Transformer-Based Motion Recognition

Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

These three architectures were selected because they represent complementary temporal modeling paradigms: LSTM models capture long-term dependencies through gated memory, GRU offers a computationally efficient recurrent alternative, and the Transformer provides a non-recurrent, self-attention-based baseline. Together, these models cover the dominant approaches used in pose-based temporal sequence analysis and enable a balanced comparative evaluation.

3.3.1. LSTM with Attention Mechanism

Recent studies have investigated integrating attention mechanisms with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to enhance performance in various sequence-learning tasks. Attention mechanisms improve models’ ability to handle long-term dependencies by enabling them to focus on relevant information [

37,

38].

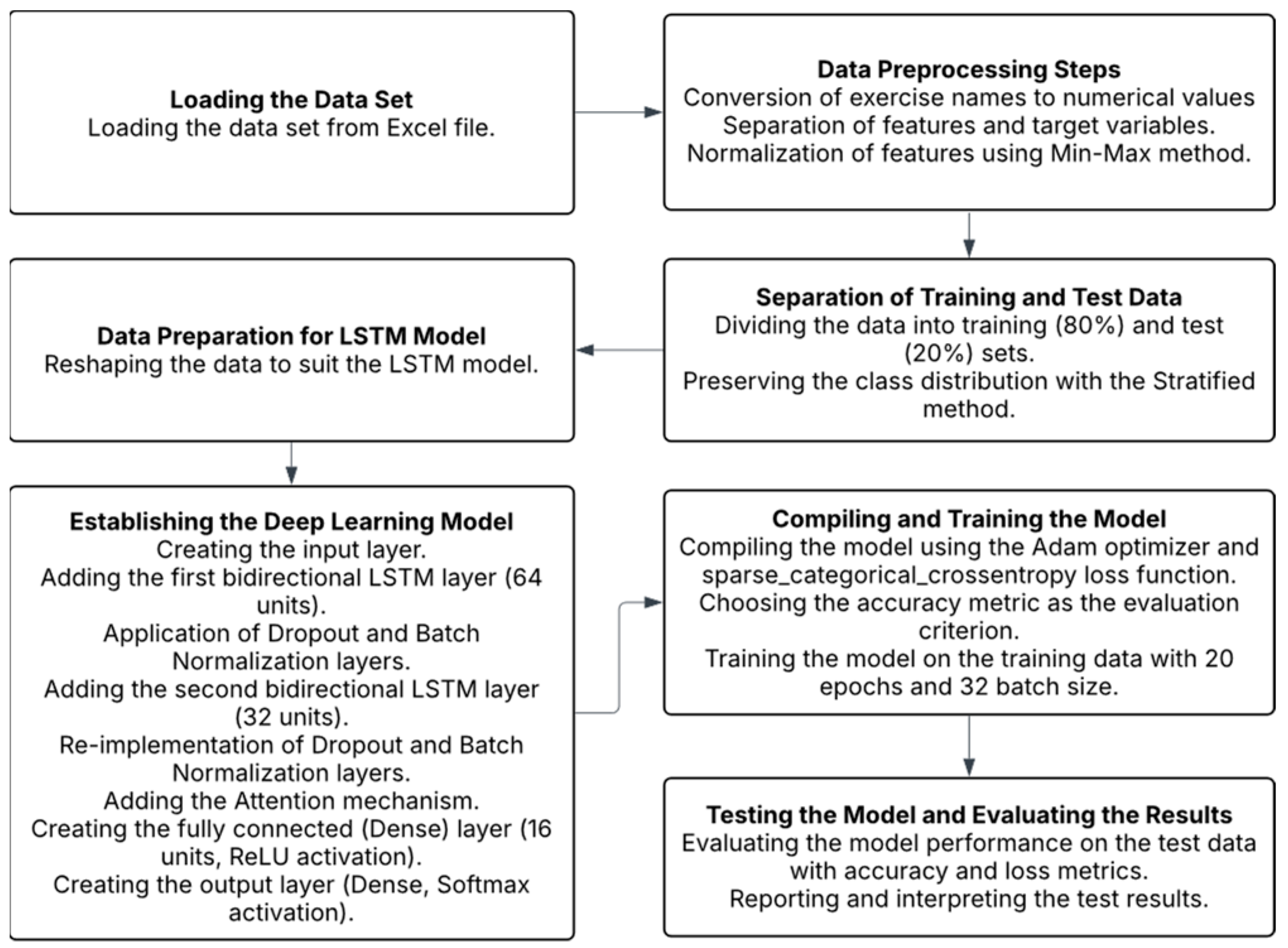

The stages in creating the model are given in

Figure 4 below.

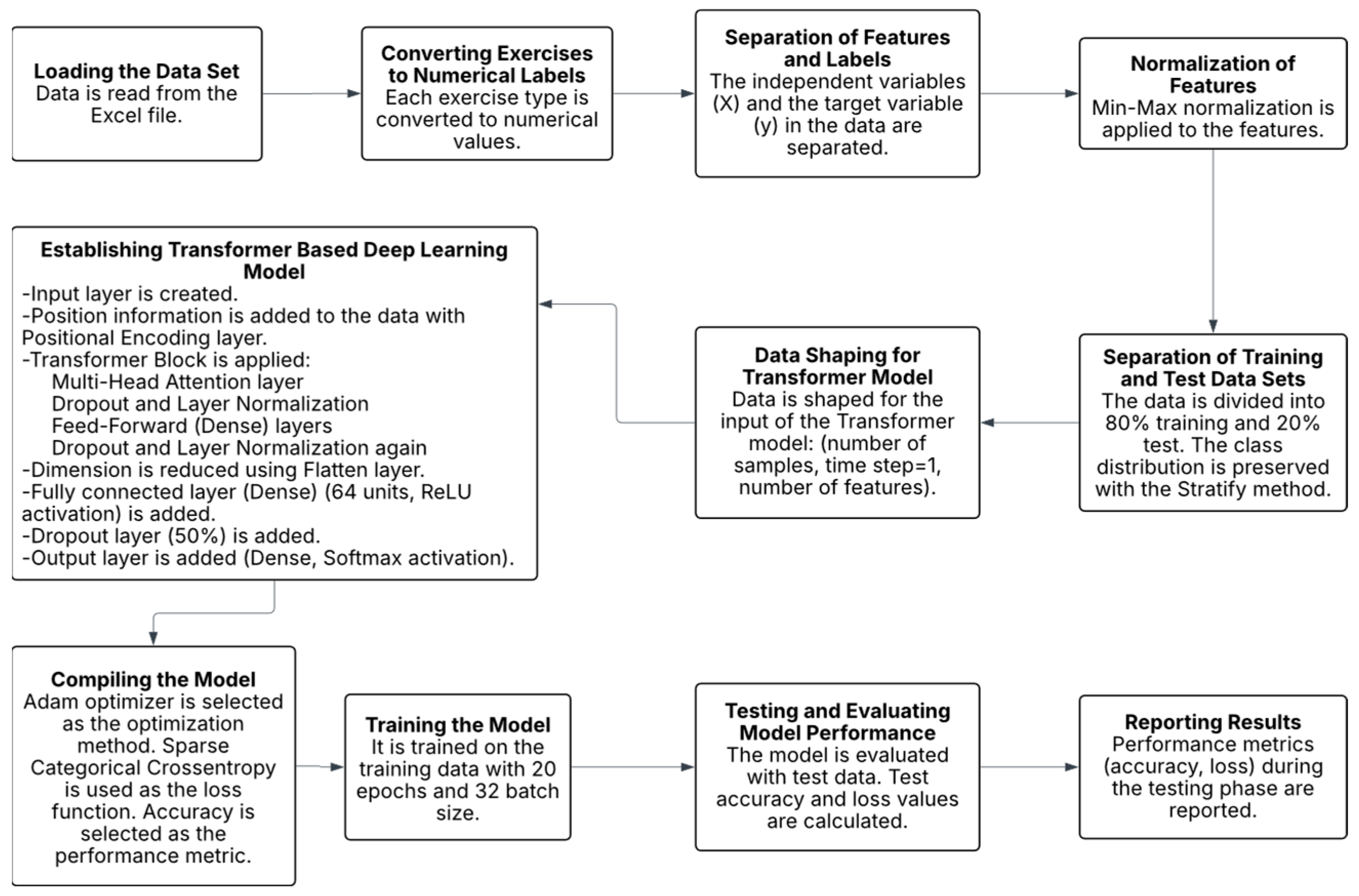

3.3.2. Transformer-Based Motion Recognition

Transformers have revolutionized various areas of artificial intelligence, including natural language processing, computer vision and speech processing [

39,

40]. These models, which utilize self-attention mechanisms, have demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional recurrent neural networks in multiple tasks [

41].

The stages in creating the model are given in

Figure 5 below.

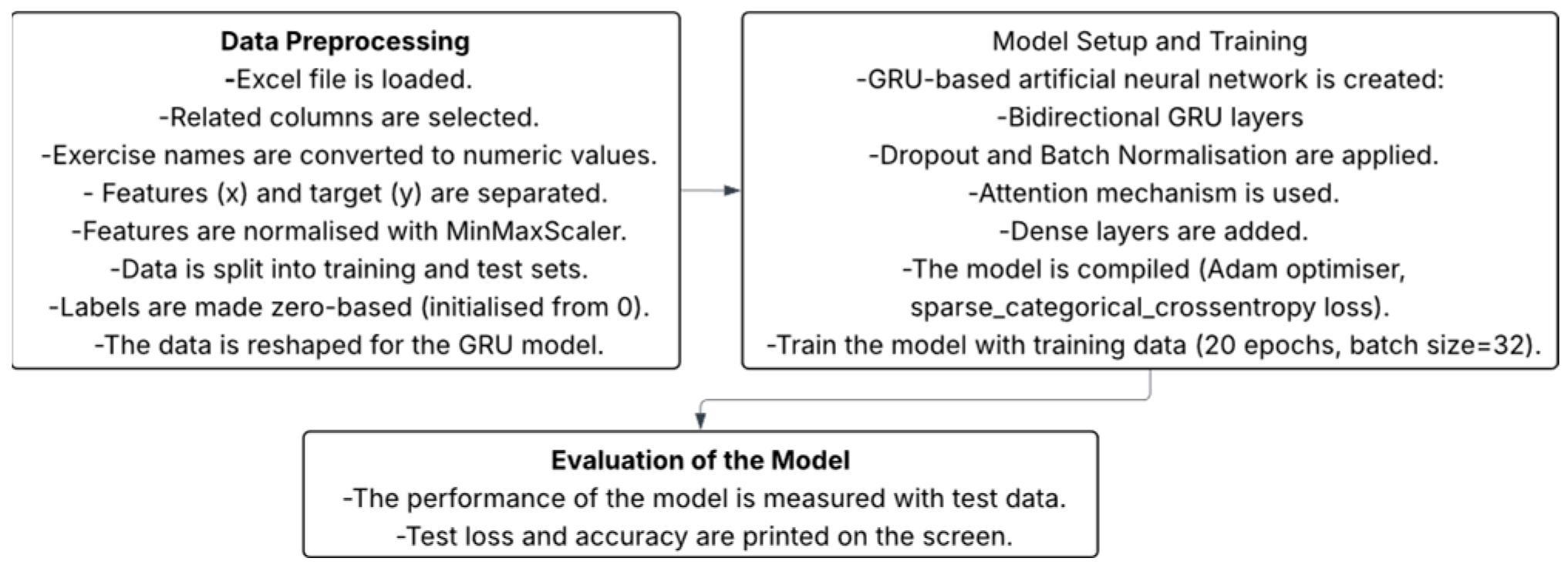

3.3.3. GRU with Attention Mechanism

The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) algorithm has demonstrated favorable outcomes in a range of applications. For instance, a study by Mohsen [

42] reported an accuracy of 97.08% for GRU in human activity recognition. Optimization techniques such as adaptive genetic algorithms [

43] and whale optimization algorithms [

44] have been employed to enhance the performance of GRU. These studies, along with others of a similar nature, underscore the versatility of GRU and its potential for enhancement through the application of various optimization techniques across diverse domains.

The stages in creating the model are given in

Figure 6 below:

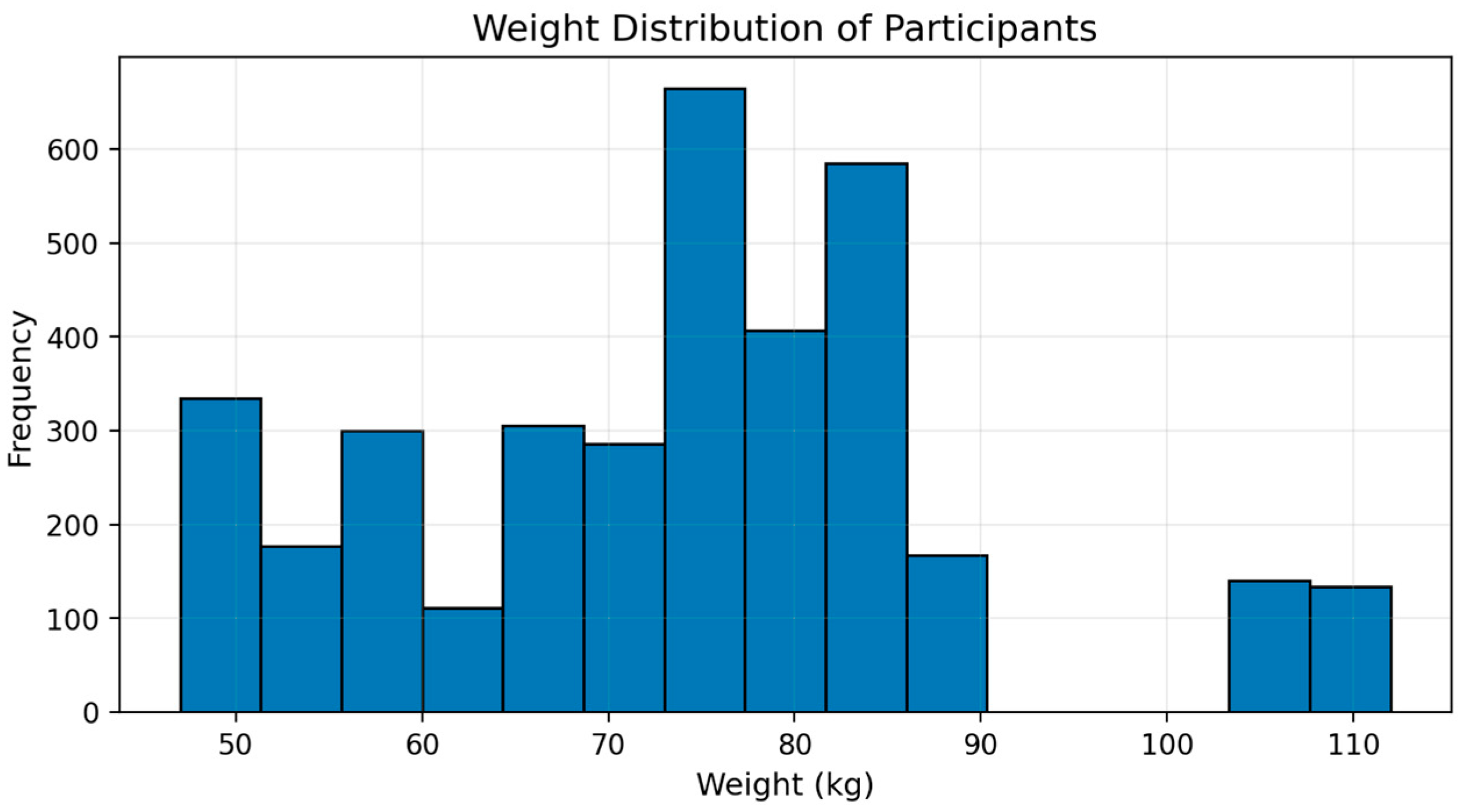

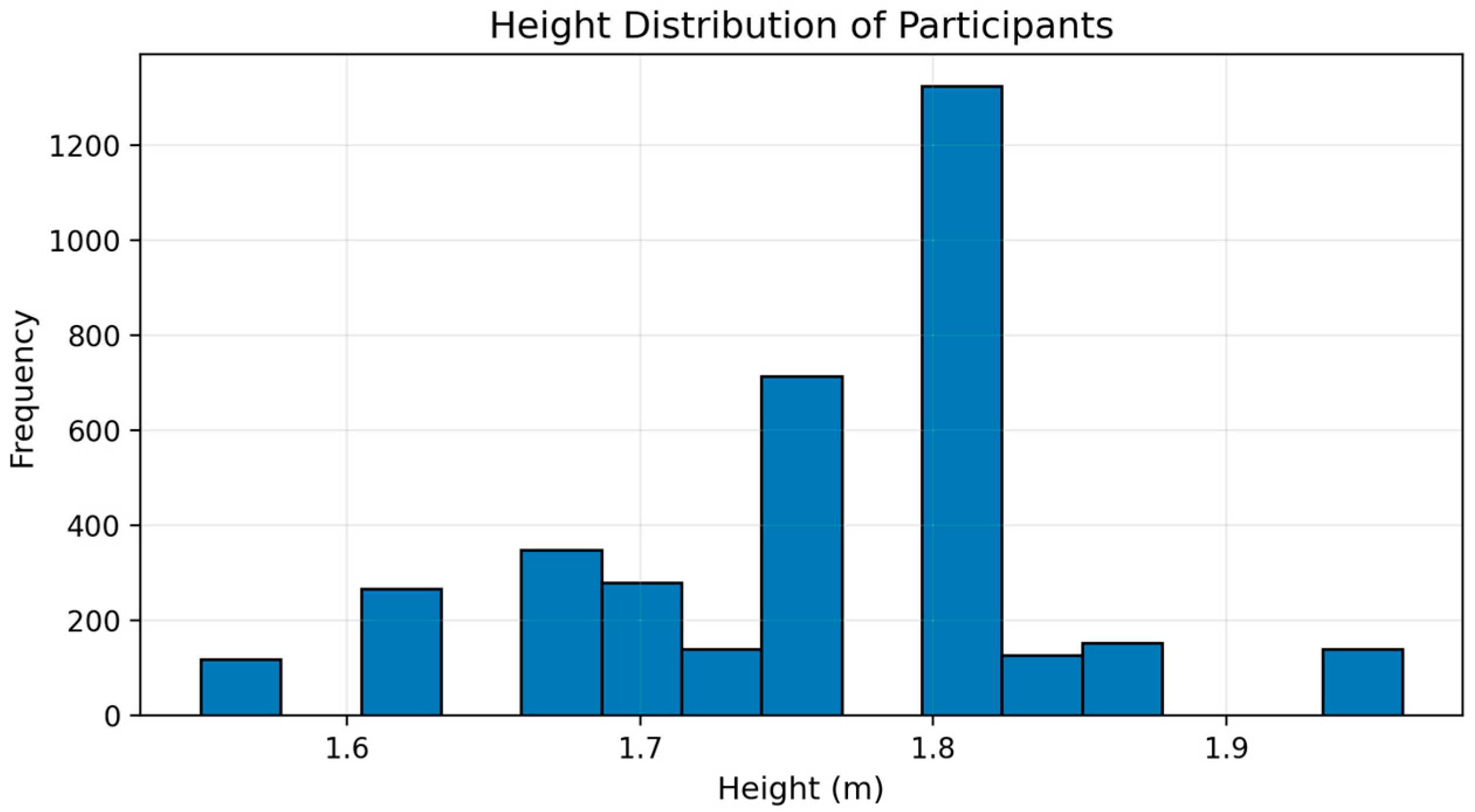

3.4. Dataset Composition

A total of 103 participants were asked to perform 5 physical movements with 2 repetitions, and time-dependent coordinated information was collected. The statistical information contained in the data set is provided in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Average Years of Sport Experience: 6.7 years

Average Weight (kg): 75.13 kg

Average Height (m): 1.77 m

Mean height and weight values are reported to summarize overall participant characteristics. Accuracy-related analyses were performed using each individual’s BMI and experience level rather than aggregated mean values.

Participant Demographic Distributions

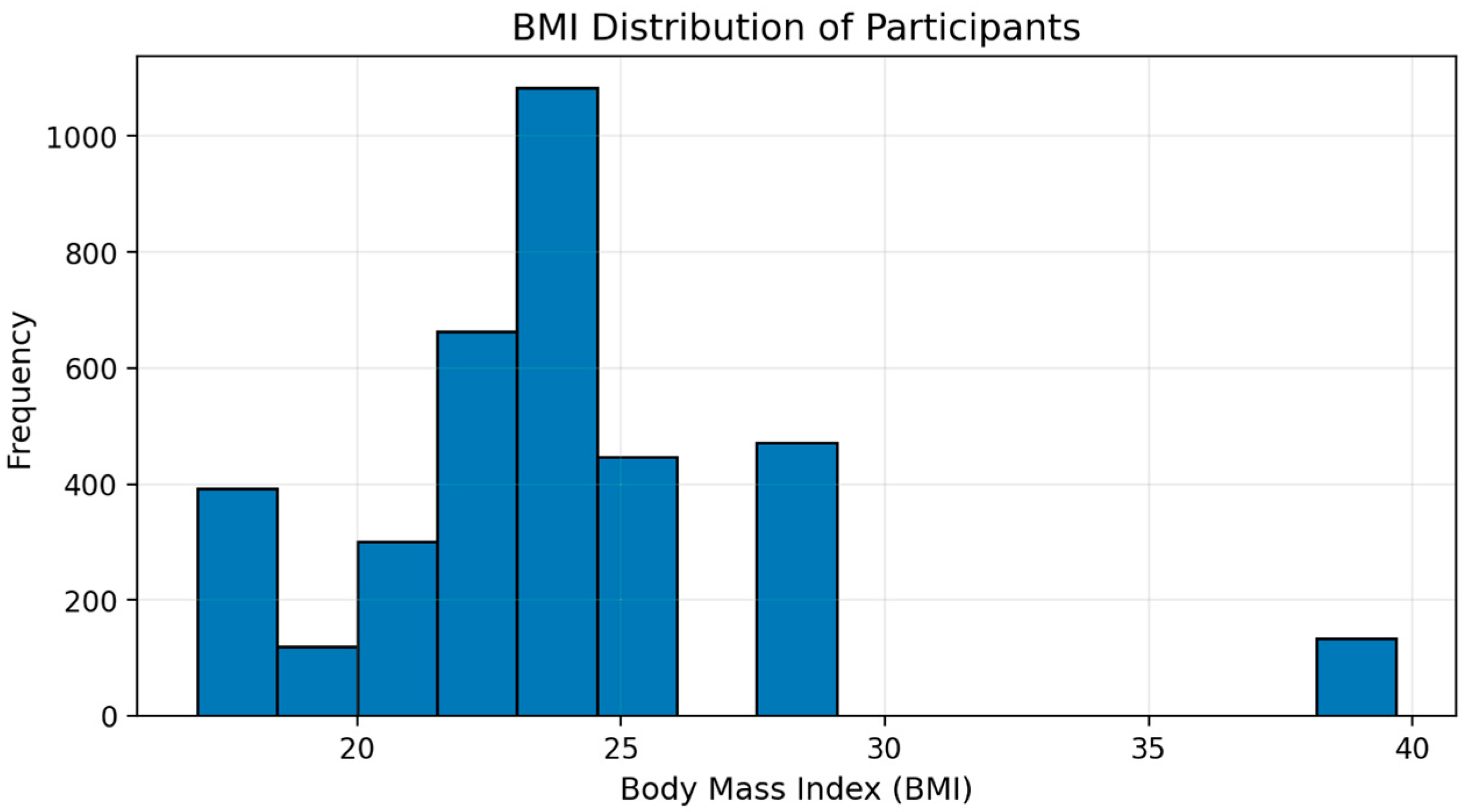

The distributions of weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) across the 103 participants are presented in

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. These histograms provide a clear overview of the anthropometric diversity within the dataset and illustrate that the participant group spans a wide range of physical characteristics. Such variability enhances the generalizability and applicability of the proposed exercise-recognition system.

Demographic and anthropometric differences are also relevant for understanding model behavior, as factors such as body proportions and BMI may influence pose trajectories and joint-angle dynamics. Including these distribution plots offers a more comprehensive description of the dataset and supports a deeper interpretation of the model performance reported in later sections.

4. Results

A total of 103 participants were instructed to perform five distinct exercises, each repeated twice, resulting in a comprehensive dataset comprising 2060 samples. The coordinate data of 33 anatomical landmarks were synchronously captured from a dual-camera setup at a constant frame rate using custom-developed software. This data was further enriched with participant-specific information, including demographic attributes and physical characteristics.

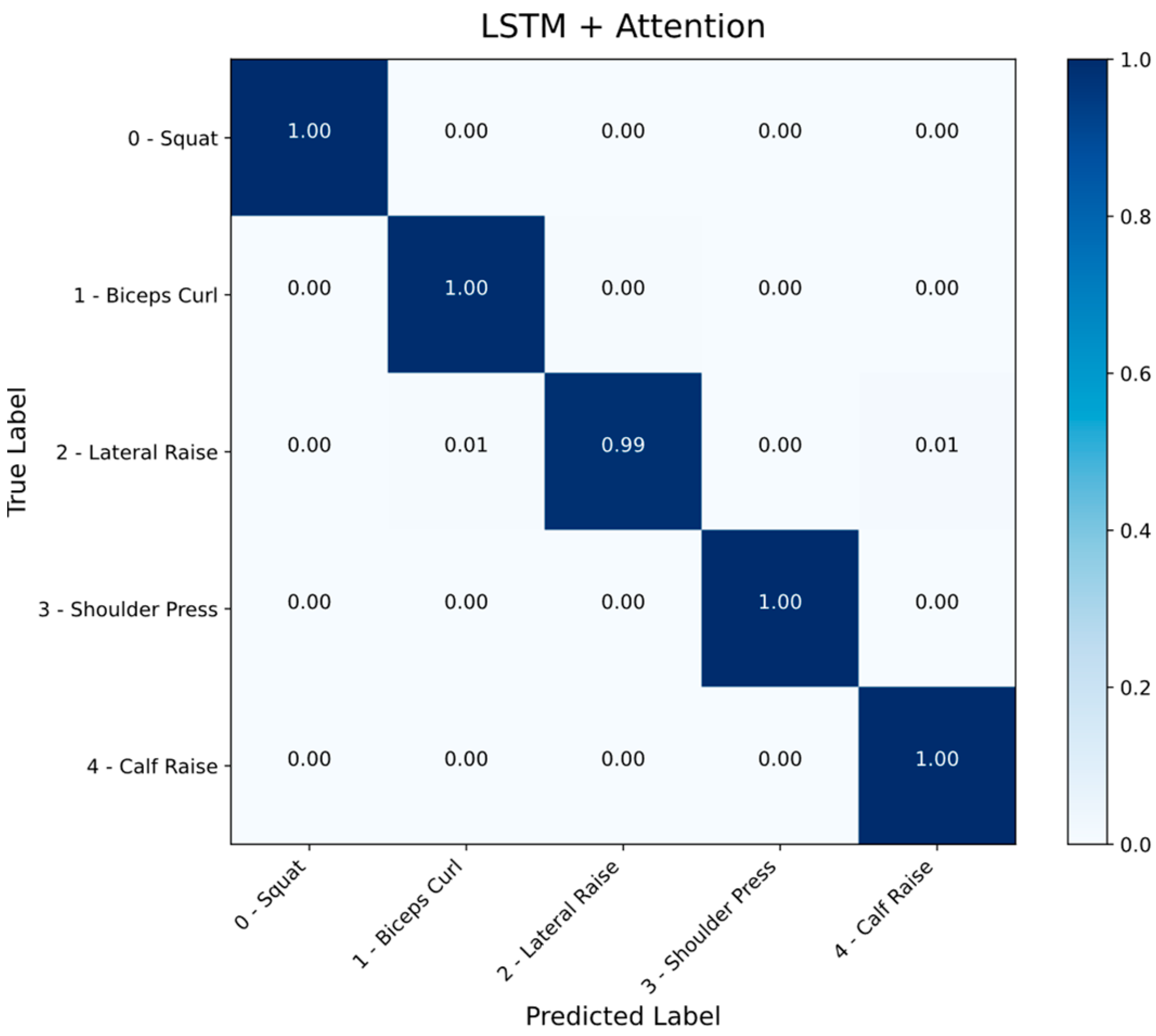

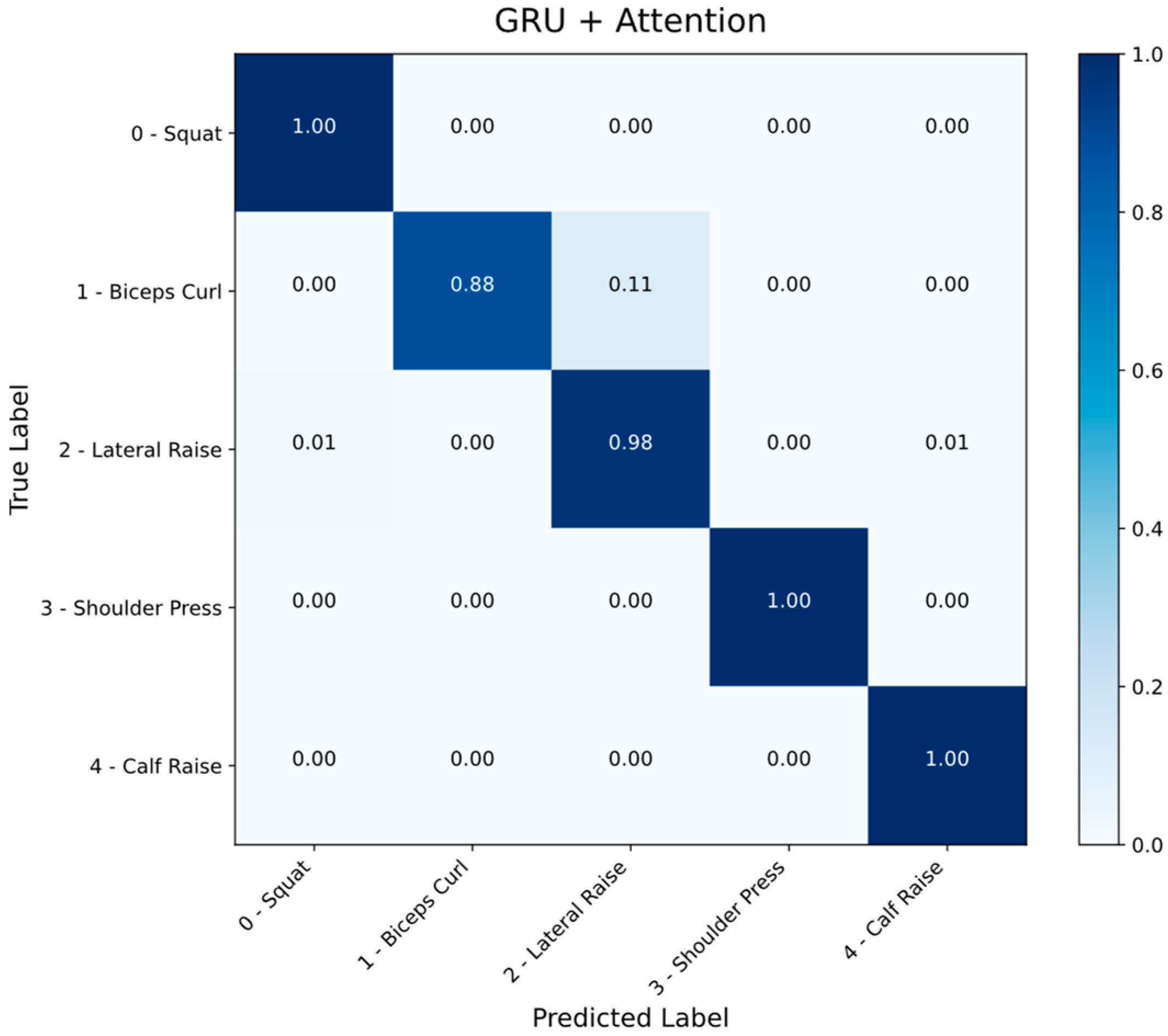

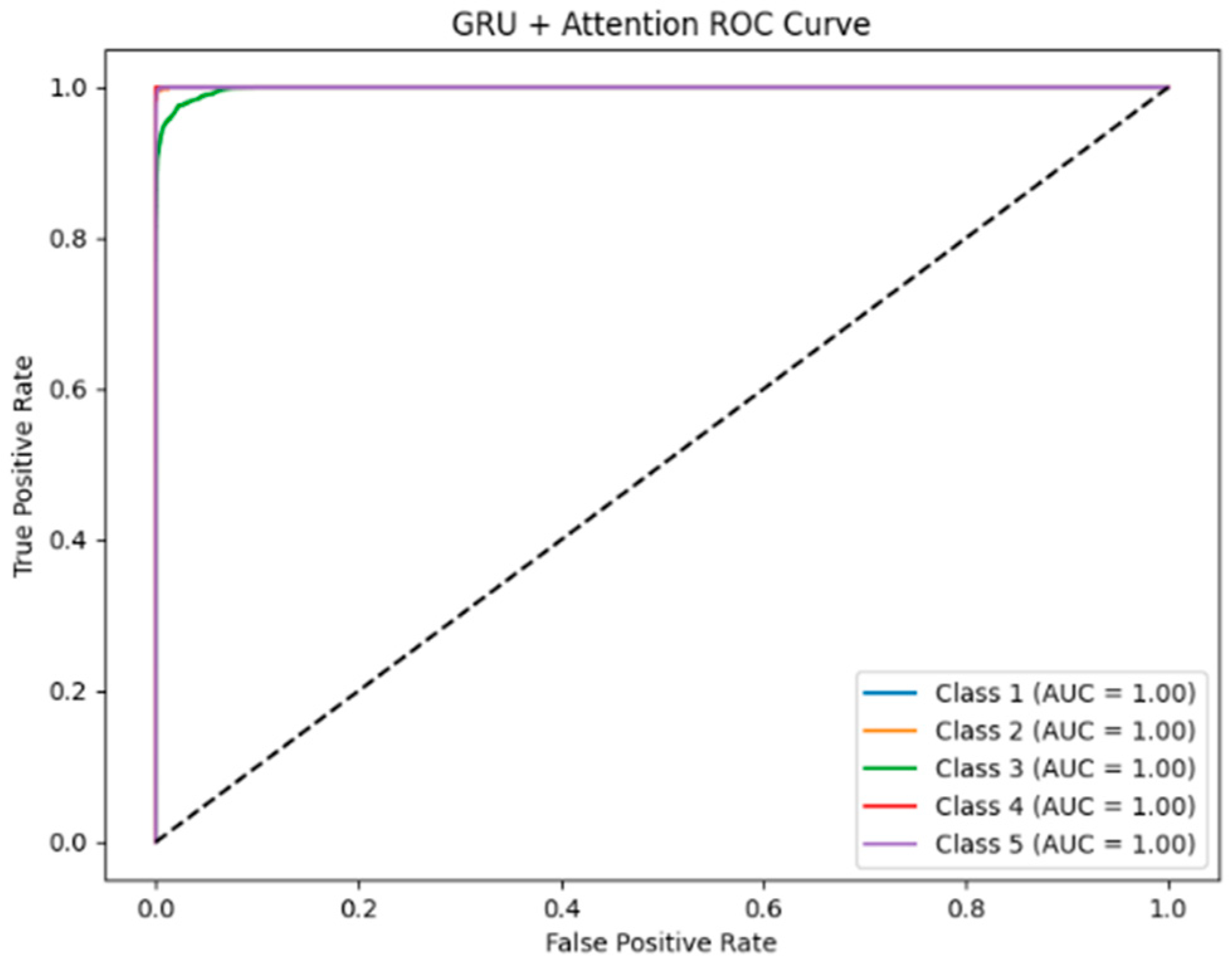

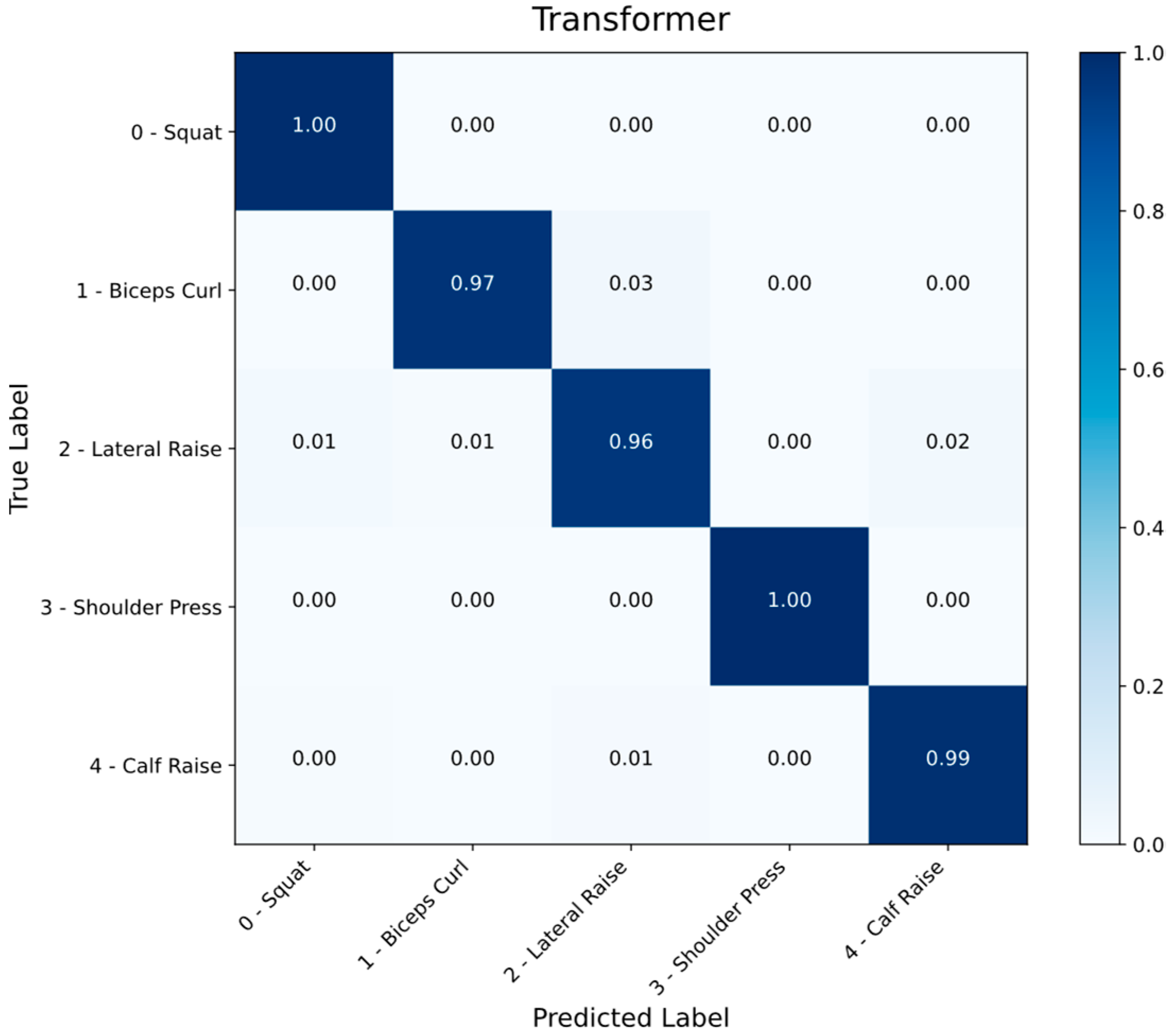

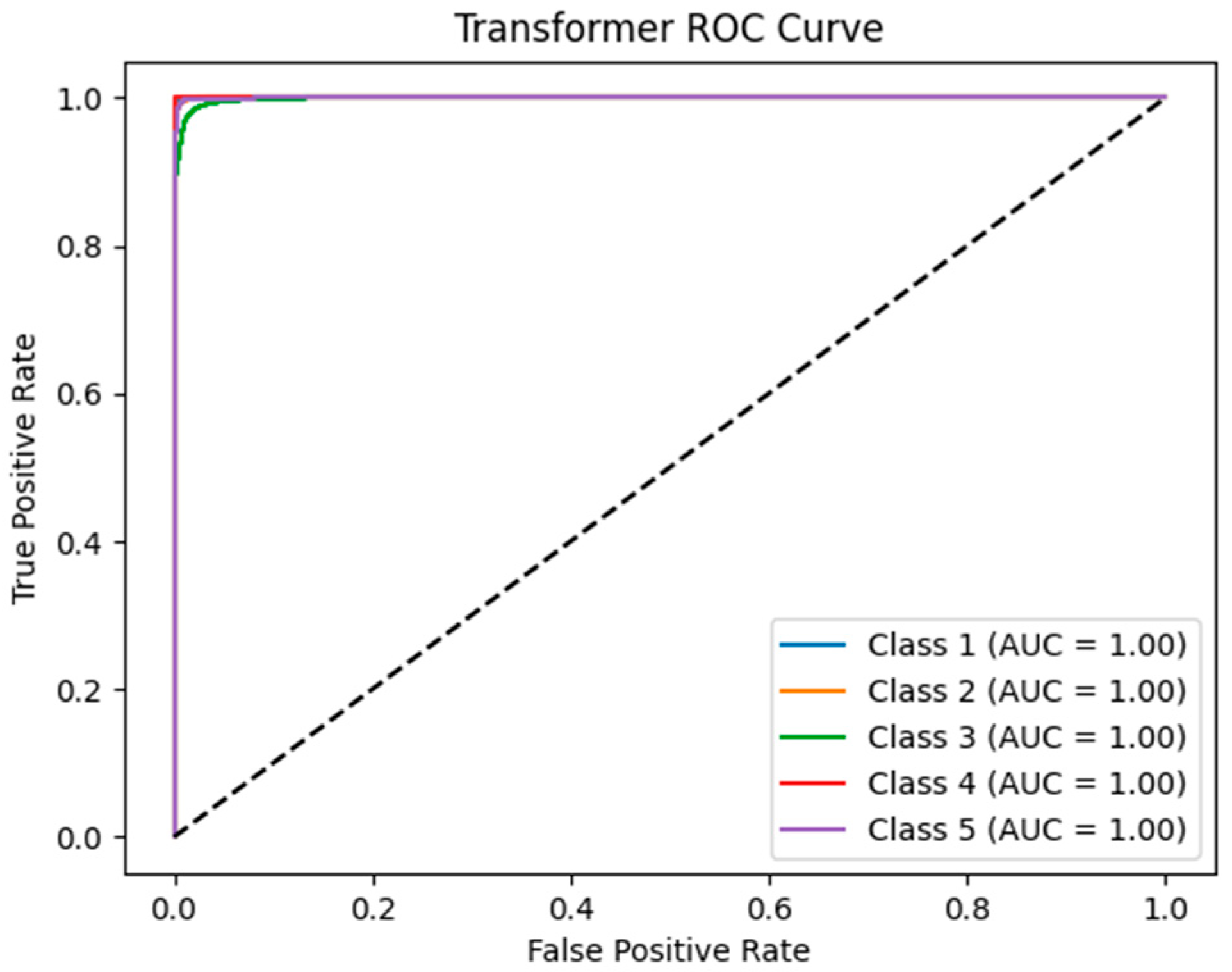

To further assess model behavior beyond mean accuracy values, confusion matrices and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for each model. These visualizations provide additional insight into classification consistency and class-specific discrimination ability. Confusion matrices and ROC curves are shown in

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

As shown in the confusion matrices, all three models demonstrated strong overall classification performance, with a clear diagonal dominance indicating high true positive rates. The LSTM + Attention and GRU + Attention models yielded particularly compact and well-defined confusion matrices, reflecting minimal class confusion. In contrast, the Transformer model exhibited relatively more dispersed misclassifications, especially between Biceps Curl and Lateral Raise exercises.

In terms of ROC analysis, all models achieved near-perfect AUC values (close to 1.00) across all classes, indicating excellent sensitivity and specificity. Nevertheless, the ROC curves of the Transformer model revealed slightly more fluctuation, suggesting minor instability in class-level discrimination compared to the recurrent-based models.

The LSTM + Attention model showed extremely high precision in recognizing “Shoulder Press” and “Calf Raise”, with negligible false positives.

The GRU + Attention model slightly struggled with distinguishing “Biceps Curl” from “Lateral Raise” yet maintained overall high classification accuracy.

The Transformer model, despite its high performance, exhibited increased class confusion, as seen in its confusion matrix and the broader, less concave curves of its ROC plot.

The resulting multimodal dataset was then used to train and evaluate various time-dependent artificial intelligence models. Each of the 10 runs corresponds to an independent model training initialized with a different random seed. This approach follows standard practice for robustness and variance assessment, enabling statistically reliable comparison across architectures. Unlike previous works that report single-run results, this study implements a 10-run randomized evaluation protocol for each architecture, followed by paired t-tests for statistical significance. This framework contributes a rigorous and reproducible methodology for comparing temporal exercise-recognition models, offering a more reliable assessment than traditional single-seed evaluations. The experimental results obtained from these models are presented as follows:

As shown in

Table 3, both the LSTM + Attention and GRU + Attention models produced consistently high and closely aligned accuracy scores across 10 independent runs, with mean accuracy rates of 98.90% and 98.97%, respectively. In contrast, the Transformer-based model achieved a lower average accuracy of 96.57%, and exhibited a higher standard deviation, indicating greater variability and less stable performance.

According to the results of the paired

t-tests presented in

Table 4:

There was no statistically significant difference in accuracy between the LSTM and GRU models (p = 0.9249).

Both the LSTM and GRU models significantly outperformed the Transformer model in terms of classification accuracy (p < 0.01).

Across ten randomized runs on the dual-camera pose dataset (103 participants; 2060 labeled sequences), both recurrent attention-based models achieved high and stable performance. LSTM + Attention and GRU + Attention yielded mean accuracies of ≈98.9% with narrow confidence bounds and low run-to-run variance; paired tests indicated no significant difference between them (p = 0.9249). In contrast, the Transformer baseline averaged ≈ 96.6% with visibly higher dispersion across seeds. Class-wise ROC analyses were uniformly high (AUCs approaching 1.0) for all models, yet the Transformer exhibited larger fluctuations across folds. Confusion matrices revealed that the principal residual errors concentrated on visually similar exercises—most notably “Biceps Curl” vs. “Lateral Raise”—with the misclassification rate for this pair highest under the Transformer. Attention-weight inspections on misclassified sequences indicated that both recurrent models concentrated salience around phase transitions (lift–lower boundaries), aligning with their lower variance and sharper decision boundaries.

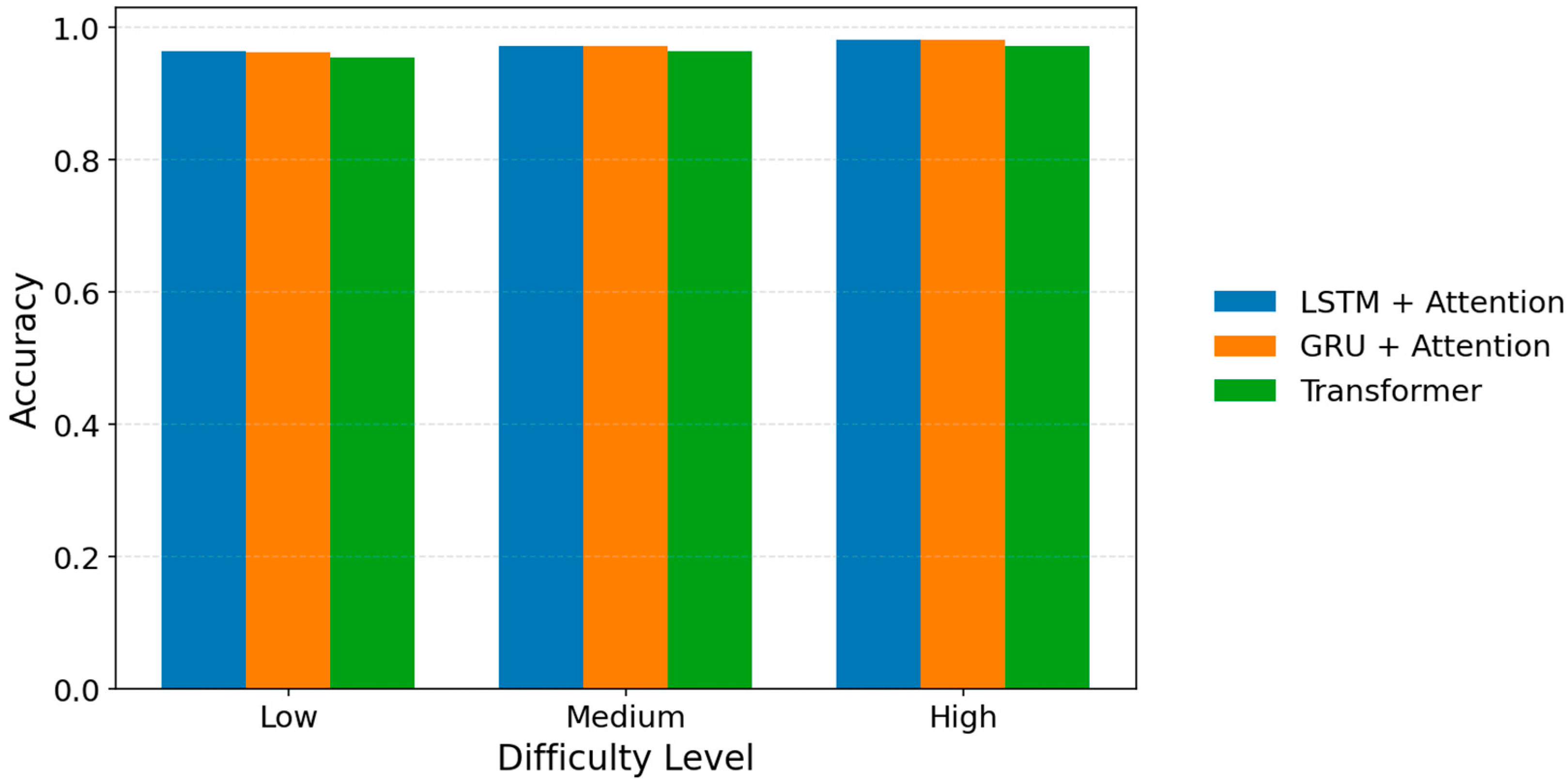

To further evaluate the robustness of the models, we analyzed classification accuracy across three exercise difficulty levels: Low, Medium, and High.

Figure 16 illustrates that all three architectures (LSTM + Attention, GRU + Attention, and Transformer) maintain consistently high accuracy across difficulty categories, indicating that the models generalize well regardless of movement complexity.

Despite slight variations—where the Transformer shows marginally lower performance in all three categories—the accuracy differences remain minimal (≤0.01), demonstrating stable recognition even as exercises become more demanding. This consistency suggests that the temporal–spatial representations extracted from dual-camera pose sequences are sufficiently discriminative across varying levels of biomechanical challenge.

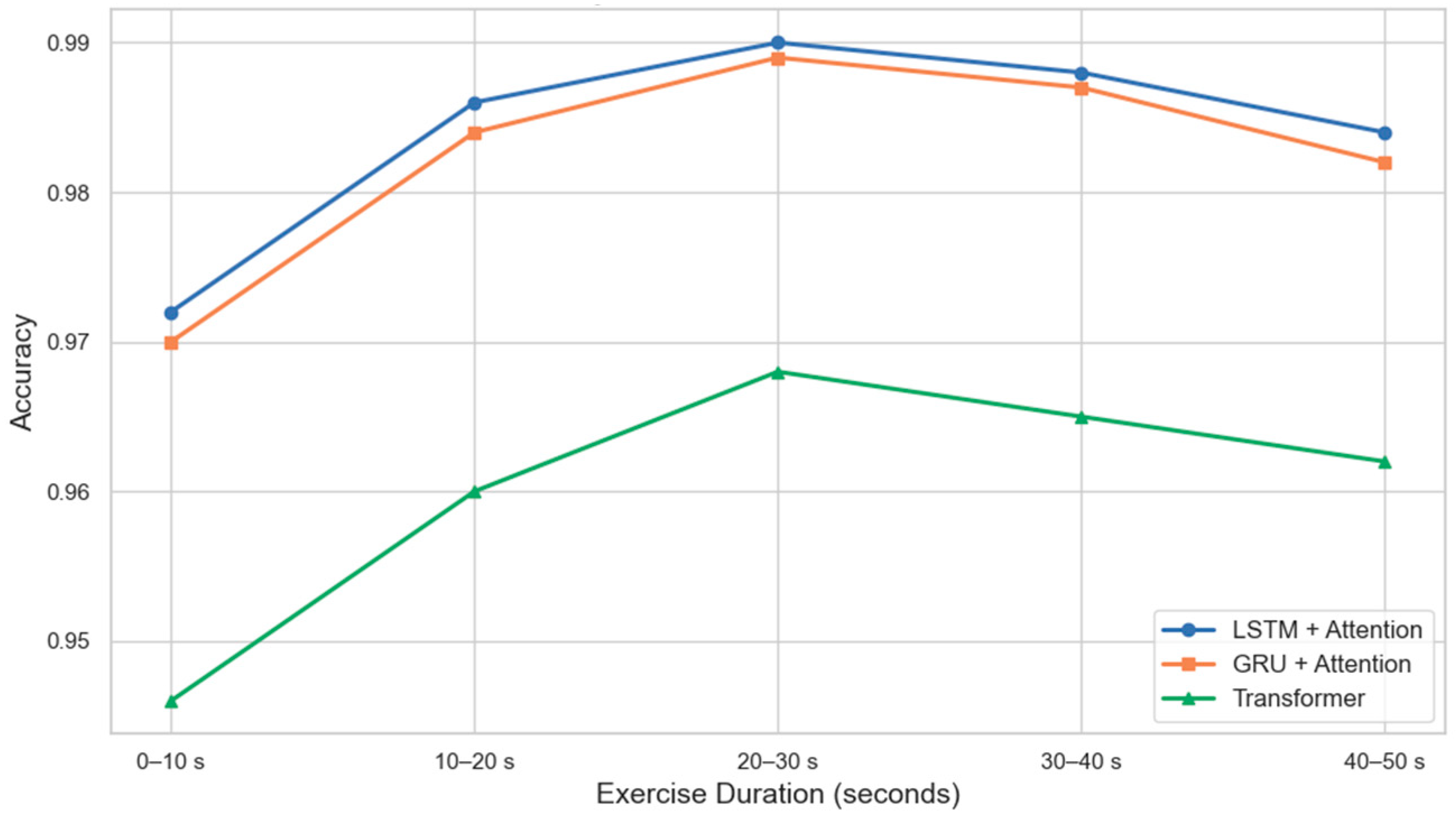

Exercise duration is an important temporal factor that may influence pose stability, movement consistency, and model discriminative performance. Longer sequences can provide richer temporal information for recurrent architectures, whereas shorter sequences may contain more variability due to rapid transitions in posture. To examine how duration affects classification accuracy, the dataset was grouped into five time intervals: 0–10 s, 10–20 s, 20–30 s, 30–40 s, and 40–50 s.

Figure 17 presents the accuracy trends of LSTM + Attention, GRU + Attention, and Transformer models across these duration ranges.

As shown in

Figure 17, both LSTM + Attention and GRU + Attention models exhibit a clear upward trend in accuracy as exercise duration increases from short (0–10 s) to moderate (20–30 s) intervals. This suggests that longer temporal windows provide more stable pose patterns, which are particularly beneficial for recurrent architectures. Accuracy slightly decreases in the 40–50 s interval, likely due to fatigue-related inconsistencies or increased intra-class variation.

In contrast, the Transformer model demonstrates a more modest improvement with duration, showing limited gains beyond the 10–20 s interval. This indicates that, within this dataset, self-attention alone may be less effective than recurrent structures in leveraging fine-grained temporal dependencies for short exercise sequences. Overall, the duration-based analysis highlights how temporal characteristics of exercise execution interact with different model architectures.

These findings suggest that, within the context of the present dataset and the exercise-recognition task, the Transformer-based architecture is less effective relative to attention-augmented recurrent baselines. In contrast, RNN-based models—particularly when enhanced with attention—demonstrate more robust and reliable performance, combining superior mean accuracy with greater stability across random initializations and folds. Taken together with the confusion-structure and ROC evidence, the results indicate that inductive biases favoring temporal continuity and phase localization confer a measurable advantage for short, structured human-movement sequences.

5. Discussion

A close inspection of the error patterns shows that, despite the diagonal dominance of the confusion matrices, cross-confusions—most notably between “Biceps Curl” and “Lateral Raise”—remain more pronounced for the Transformer (

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15). Although the individual components (MediaPipe pose extraction, LSTM/GRU/Transformer architectures) are well-established, the present work provides a methodological advance by integrating (i) synchronized dual-camera temporal acquisition, (ii) multimodal fusion of anthropometrics with pose sequences, and (iii) statistically rigorous 10-run model comparison. These elements collectively provide new insights into viewpoint robustness, personalization, and model stability—areas that remain insufficiently explored in existing exercise-recognition literature. This suggests that local similarities in joint-angle configurations can blur class boundaries when temporal context is not modeled with sufficiently strong inductive biases. In exercise classification tasks where fine-grained temporal cues are critical, recurrent memory dynamics, especially when coupled with attention, appear to yield more separable decision regions than self-attention alone [

37,

42]. While class-wise ROC curves approach unity across all models, the comparatively greater fluctuation observed for the Transformer implies that, under limited and relatively homogeneous data regimes, self-attention may struggle to sustain stable discrimination at the class level [

39,

41]. These observations reinforce the benefit of mechanisms that prioritize “critical instants” along the sequence—e.g., frame-level or segment-level attention—to better capture phase transitions integral to movement identity.

Attention-map examinations on misclassified or low-confidence sequences further indicate that focus often shifts around repetition thresholds (e.g., lift–lower transitions). In the recurrent models, attention weights concentrate more tightly on these transition phases, which enhances signal-to-noise separation; by contrast, the Transformer’s multi-head focus tends to be broader, effectively “diluting” context over short windows. Methodologically, this motivates (i) sequence-length sensitivity analyses (alternative window sizes) and (ii) targeted data augmentation—temporal jitter, speed scaling, and viewpoint/scale perturbations—to sharpen decision boundaries. Consistent with

Table 3 and

Table 4, the tightly clustered mean accuracies of LSTM + Attention and GRU + Attention (≈98.9%) and their low variance indicate more reliable responses to phase changes, whereas the slightly higher standard deviation for GRU points to heightened sensitivity to weight initialization and optimization dynamics.

From an explainability standpoint, projecting attention weights onto the time axis highlights “instructional” frames (e.g., lockout in the shoulder press, heel-rise onset in the calf raise) that help disentangle visually similar postures. Because attention peaks are narrower and more concentrated for LSTM/GRU, these models may also be advantageous for real-time deployment under tight latency budgets: inference can allocate more compute to brief micro-windows containing decisive evidence while maintaining throughput at 30 FPS in a dual-camera setup [

37,

42]. This property aligns with the study’s practical aim of enabling real-time feedback without expert supervision.

In terms of generalizability, the dataset’s scope—103 participants performing five exercises—underscores the need for broader scene diversity (tempo variation, partial repetitions, grip width), clothing/illumination differences, and device heterogeneity to robustly assess out-of-distribution resilience. The Transformer’s higher variance plausibly reflects underexposure to such diversity; this variability may diminish with larger and more heterogeneous corpora and, crucially, with multimodal inputs (e.g., depth, IMU), which can supply complementary cues (perspective, micro-kinematics) that are muted in 2D pose trajectories [

39,

41]. In the interim, hybrid designs that combine recurrent temporal encoders with lightweight self-attention layers offer a pragmatic pathway, potentially harnessing the strengths of both paradigms until data scale and diversity catch up.

Personalization remains central to real-world performance. The demonstrated effects of BMI and athletic experience on accuracy motivate systematic inclusion of contextual and anthropometric covariates in the model input. In line with emerging work on context-aware systems in sports and rehabilitation [

23,

25], a multi-branch fusion layer that ingests demographic/anthropometric features (e.g., limb-segment ratios, flexibility proxies) alongside pose sequences may improve separation between look-alike movements and reduce the shift of errors from inter-class to inter-user variability. Such personalization could, in practice, yield more equitable performance across diverse populations and skill levels. Participants with higher BMI and lower training experience exhibited slightly increased misclassification rates, indicating that anthropometric variability may influence movement execution patterns and consequently affect model performance. This supports the importance of incorporating demographic covariates into personalized feedback systems.

For field deployment, several engineering considerations are salient: (i) complementing software-based dual-camera synchronization with periodic drift calibration or low-latency hardware triggers; (ii) augmenting viewpoint and illumination diversity to harden models against real-world noise; (iii) model compression (quantization; low-bit GEMMs) and pipeline parallelism to sustain edge–device throughput; and (iv) surfacing explanation artifacts in the user interface so that misclassifications come with human-interpretable evidence (“why this feedback now?”). These system-level refinements are well aligned with the stable recurrent performance reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4 (

p = 0.9249 for LSTM vs. GRU; both significantly better than the Transformer) and would facilitate translating lab-grade results to everyday conditions.

Finally, ethical and trust considerations—privacy, informed consent, and transparency—will shape adoption in clinical and home settings. The study’s use of anonymized collection and written consent provides a sound basis for larger-scale trials; extending this with user-visible versioning/audit trails and rationale displays for exercise-level scores can accelerate trust formation and responsible use. Transitioning from these observations, the concluding paragraph’s emphasis on dataset expansion, in-the-wild evaluation, and integration of explainable AI modules follows naturally and sets a concrete agenda for scaling accessibility and confidence in autonomous feedback systems.

6. Conclusions

This study conducted a rigorous comparison of three temporal architectures—LSTM + Attention, GRU + Attention, and a Transformer baseline—for autonomous exercise recognition from dual-camera 2D pose trajectories in a cohort of 103 participants (2060 labeled samples). Across ten randomized runs, both recurrent attention-based models achieved high and stable accuracy (mean ≈ 98.9%) and significantly outperformed the Transformer (mean ≈ 96.6%). Paired t-tests confirmed no meaningful difference between LSTM and GRU (p = 0.9249), while both were superior to the Transformer (p < 0.01), a pattern consistent with confusion-matrix and ROC analyses indicating tighter class separation and lower variance for the recurrent models. These findings highlight that, in modest-scale, relatively homogeneous pose datasets, inductive biases for sequential continuity afforded by RNNs—amplified through attention—remain advantageous over purely self-attentional models. The analyses further showed that participant-specific covariates (e.g., BMI, athletic level) influence recognition performance, supporting the practical value of contextual features for personalization. Together, the results demonstrate a feasible, real-time pathway for expert-free exercise feedback with prospective utility in fitness, sports analytics, and rehabilitation settings.

Beyond these empirical outcomes, the work contributes: (i) a reproducible evaluation protocol with multi-run statistics and significance testing, (ii) an end-to-end pipeline for synchronized dual-camera capture and pose-based temporal modeling, and (iii) evidence that lightweight attention atop recurrent encoders can deliver both accuracy and stability for short, structured exercise sequences. Methodologically, our error analyses (confusion structure and ROC fluctuation) indicate that misclassifications concentrate around phase transitions for visually similar movements (e.g., biceps curl vs. lateral raise), underscoring the utility of attention to emphasize “critical instants” and motivating targeted augmentation (temporal jitter, speed scaling, viewpoint/illumination variation) to harden decision boundaries in real-world deployments.

Nevertheless, several limitations and opportunities for impact remain. The exercise taxonomy is deliberately constrained, and recordings were acquired in controlled conditions; broader scene diversity (tempos, partial repetitions, occlusions, clothing and lighting variations, device heterogeneity) and evaluation “in the wild” are needed to stress-test generalization. The reliance on 2D pose also suppresses depth and fine-grained kinematic cues; richer sensing promises to reduce ambiguity in look-alike patterns. Finally, while demographic features improved contextuality, systematic strategies for equitable personalization and calibration across subgroups are essential for inclusive performance.

Building on these results, several directions can be advanced to strengthen movement recognition and real-time utility. First, recognition robustness can be improved by fusing complementary modalities (RGB-D depth and IMU signals) with 2D pose and by exploring hybrid temporal encoders that combine recurrent filters for local continuity with lightweight self-attention for longer-range dependencies. Second, model resilience under distribution shift can be advanced through targeted augmentation curricula (viewpoint/occlusion, lighting/clothing variation, tempo and partial-rep diversity), domain adaptation, and self-/semi-supervised objectives that leverage large unlabeled repetition corpora. Third, personalization and fairness can be enhanced via multi-branch fusion of anthropometric/demographic covariates with sequence embeddings, together with meta-learning or test-time adaptation to enable rapid per-user calibration and subgroup-aware evaluation to mitigate disparate error rates. Fourth, explainability and safety can be progressed by integrating attention/attribution overlays and calibrated uncertainty estimates directly into the interface, enabling human-interpretable evidence at the moment of decision. Crucially, a quantitative scoring framework can be incorporated to rate movement correctness (e.g., phase-specific form scores, range-of-motion completeness, tempo adherence), which can in turn be fed back into the model as supervision to further reinforce recognition and reduce confusions between visually similar exercises. In parallel, synchronous, real-time feedback can be strengthened by co-designing the end-to-end stack—pose estimation, temporal inference, and rendering—for edge devices using quantization, operator fusion, and low-bit GEMMs to meet tight latency budgets without compromising accuracy; closed-loop evaluations can then assess whether instantaneous cues improve technique and adherence. Finally, longitudinal, IRB-approved trials and the release of reproducible benchmarks, model cards, and privacy-preserving data schemas can extend the work’s external validity and practical impact.

This work shows that attention-enhanced recurrent architectures provide a strong and stable foundation for autonomous exercise recognition in compact pose datasets, clarifies when and why they outperform Transformers, and outlines a practical route to multimodal, explainable, and equitable AI coaching at scale. By advancing robustness, personalization, quantitative scoring of technique, and truly synchronous feedback, we aim to translate lab-grade performance into trustworthy, everyday tools for athletes, patients, and practitioners.