Plant-Derived Biostimulants and Liposomal Formulations in Sustainable Crop Protection and Stress Tolerance

Abstract

1. Introduction

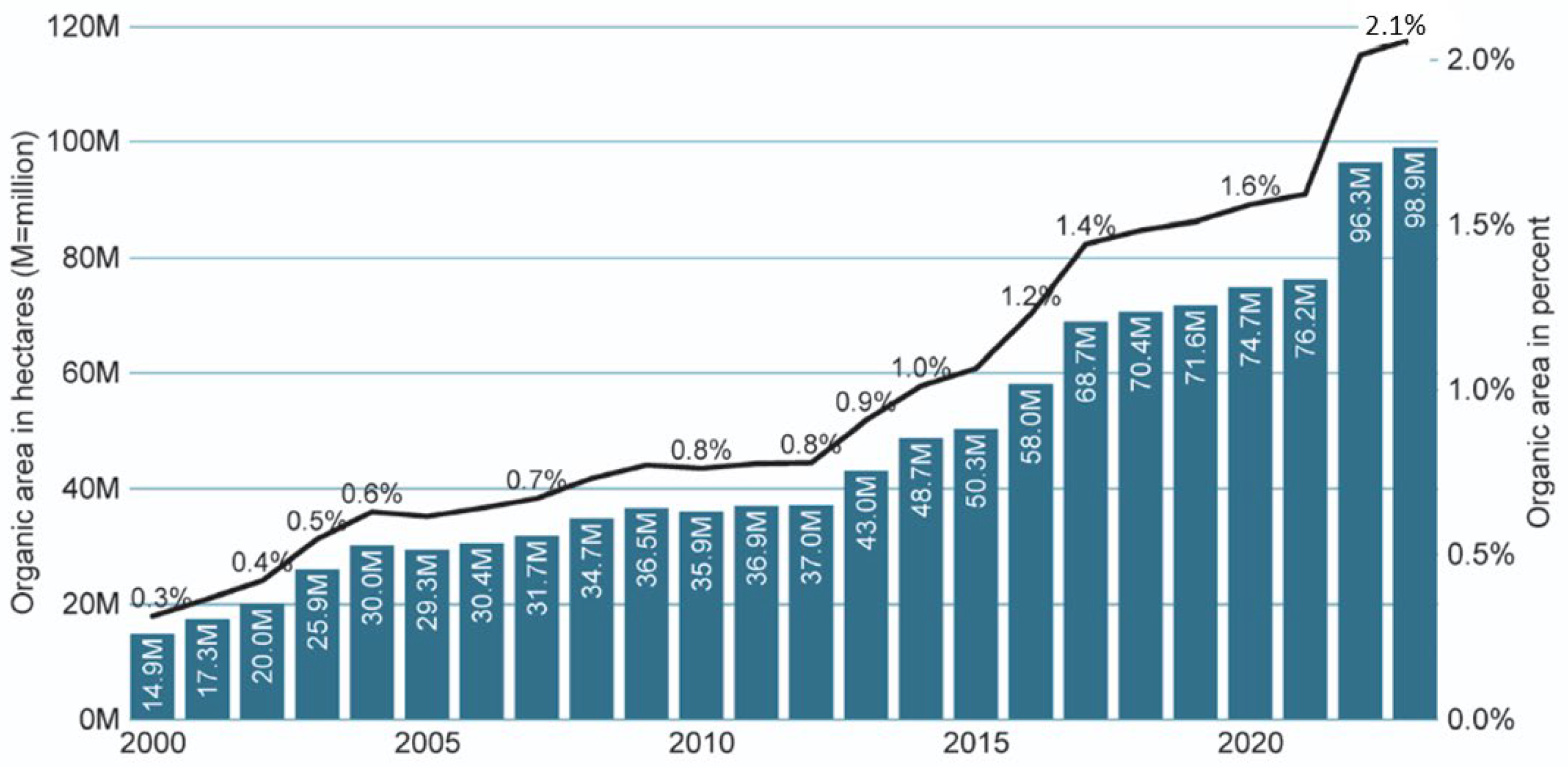

2. Organic Agriculture and Regulatory Frameworks

2.1. The Significance of Organic Agriculture Globally and in the European Union

2.2. Types of Fertilizing Products, Plant Conditioners, and Plant Protection Preparations, and the Regulation of Their Use in Organic Farming

2.3. Regulatory Context of Liposomal Nano-Formulations in the European Union

2.4. Biopesticides

2.5. Categories of Plant Biostimulators and Their Use as Plant Conditioners

3. Plant-Derived Biostimulators

3.1. Bioactive Compounds of Plant-Biostimulators

3.2. An Example for a Complex of Plant-Extracts: EliceVakcina Biostimulator

3.3. Garlic-Extract as Biostimulator

3.4. Plant Biostimulators in Stress Tolerance

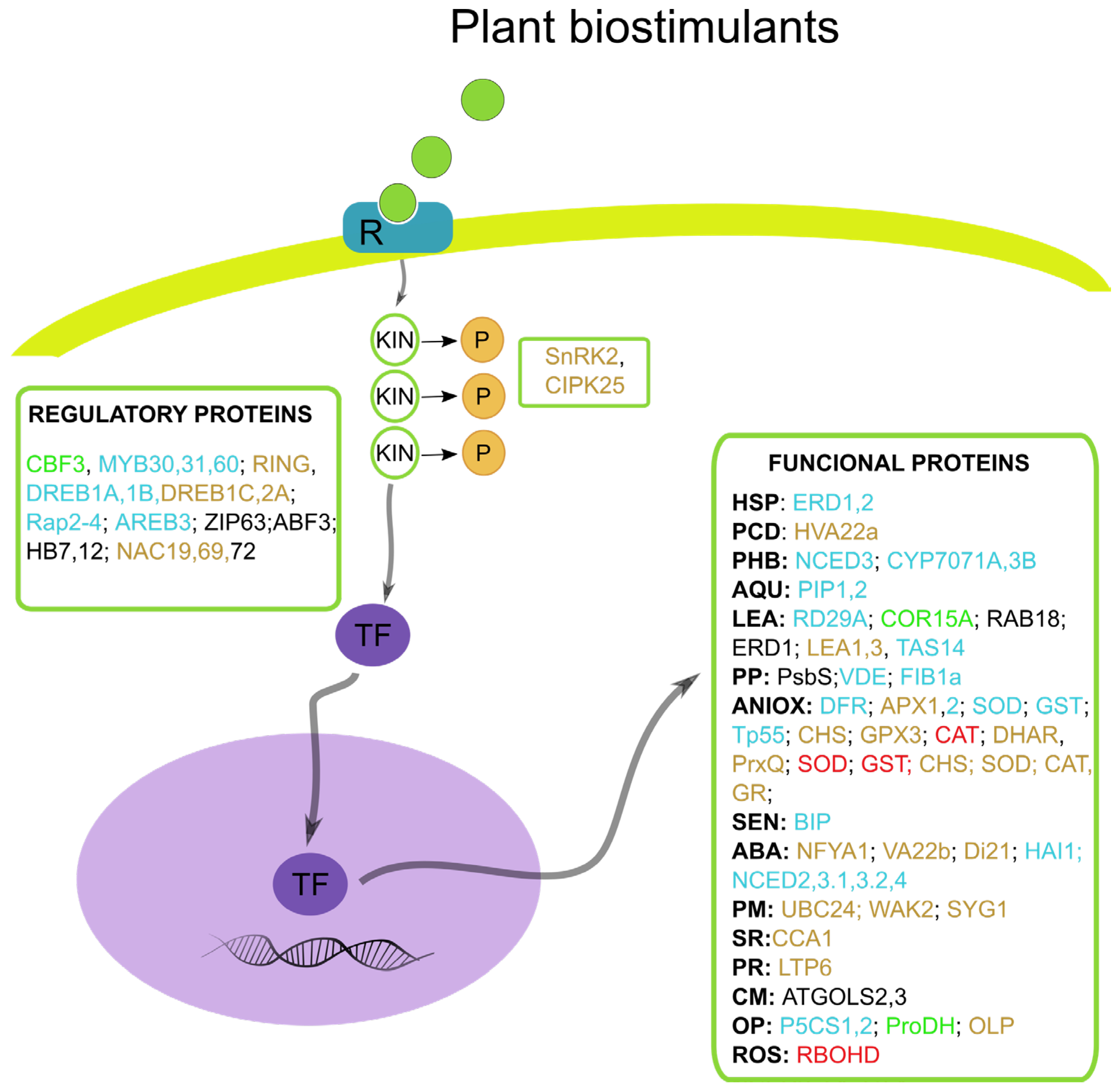

3.5. The Transcriptomic Effect of Plant-Based Biostimulators in Abiotic and Biotic Stress

4. Nanotechnology in Biostimulator- and Biopesticide Formulation

4.1. Nano-Biopesticides

4.2. Nano-Sized Carrier Biopesticides

5. Liposomal Formulations

5.1. Micro- and Nanoencapsulation Strategies: Methods, Characterization, and Practical Considerations

5.2. Encapsulated Formulations in Agriculture

Prospective Encapsulated Biostimulant Formulations for Different Stress Types

5.3. Liposomes in Agriculture

5.3.1. Translocation Pathways and Stability of Liposomal Nanoformulations in Crop Systems

5.3.2. Antiviral Effects of Liposome-Formulated Plant Extracts Against Phytopathogenic Viruses

5.3.3. Antibacterial Effects of Liposome-Formulated Plant Extracts Against Phytopathogenic Bacteria

5.3.4. Antifungal Effects of Liposome-Formulated Plant Extracts Against Phytopathogenic Fungi

5.3.5. Insecticidal and Repellent Effects of Liposome-Formulated Plant Extracts

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| AGE | aqueous garlic extract |

| APX | ascorbate peroxidase |

| CAT | catalase |

| DLS | dynamic light scattering |

| DHAR | dehydroascorbate reductase |

| DPPC | dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| FPR | Fertilising Products Regulation |

| GR | dehydroascorbate glutathione reductase |

| HSP70 | heat shock protein 70 |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| NP | nanoparticle |

| OLP | osmotin-like protein |

| POD | peroxidase |

| PrxQ | peroxiredoxin |

| PB | plant biostimulant |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SnRK | SNF1-related protein kinase |

| SC-CO2 | supercritical carbon dioxide extraction |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| TMV | tobacco mosaic virus |

| TF | transcription factor |

| TEM | transmission electron microscope |

References

- Di Sario, L.; Boeri, P.; Matus, J.T.; Pizzio, G.A. Plant biostimulants to enhance abiotic stress resilience in crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szopa, D.; Witek-Krowiak, A. Optimization of the composition of biopolymer matrices for encapsulating liquid biostimulants. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Arias, D.; Morales-Sierra, S.; García-García, A.L.; Herrera, A.J.; Pérez Schmeller, R.; Suárez, E.; Santana-Mayor, Á.; Silva, P.; Borges, J.P.; Pinheiro de Carvalho, M.Â. Alginate Microencapsulation as a Tool to Improve Biostimulant Activity Against Water Deficits. Polymers 2025, 17, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorente, S.E.; Martí-Guillén, J.M.; Pedreño, M.Á.; Almagro, L.; Sabater-Jara, A.B. Higher plant-derived biostimulants: Mechanisms of action and their role in mitigating plant abiotic stress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyhorn, F.; Muller, A.; Reganold, J.P.; Frison, E.; Herren, H.R.; Luttikholt, L.; Mueller, A.; Sanders, J.; Scialabba, N.E.-H.; Seufert, V. Sustainability in global agriculture driven by organic farming. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, L.A.; Pérez-Méndez, N.; Garratt, M.P.; Gemmill-Herren, B.; Miguez, F.E.; Dicks, L.V. Policies for ecological intensification of crop production. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyjaszczyk, E. Legislative situation of botanicals used in plant protection in the European Union. JPDP 2023, 130, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, H.; Kestens, V.; Rasmussen, K.; Linsinger, T.; Stefaniak, E. Guidance on the Implementation of the Commission Recommendation 2022/C 229/01 on the Definition of Nanomaterial; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nederstigt, T.A.; Brinkmann, B.W.; Peijnenburg, W.J.; Vijver, M.G. Sustainability claims of nanoenabled pesticides require a more thorough evaluation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 2163–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, A. Biopesticides: Present status and the future prospects. J. Fertil. Pestic. 2015, 6, 1000e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenibo, E.O.; Ijoma, G.N.; Matambo, T. Biopesticides in sustainable agriculture: A critical sustainable development driver governed by green chemistry principles. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 619058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suteu, D.; Rusu, L.; Zaharia, C.; Badeanu, M.; Daraban, G.M. Challenge of utilization vegetal extracts as natural plant protection products. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laznik, Ž.; Tóth, T.; Lakatos, T.; Vidrih, M.; Trdan, S. Control of the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata [Say]) on potato under field conditions: A comparison of the efficacy of foliar application of two strains of Steinernema feltiae (Filipjev) and spraying with thiametoxam. JPDP 2010, 117, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiber, J.N.; Coats, J.; Duke, S.O.; Gross, A.D. Biopesticides: State of the art and future opportunities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 11613–11619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarić-Krsmanović, M.; Gajić-Umiljendić, J.; Radivojević, L.; Šantrić, L.; Đorđević, T.; Đurović-Pejčev, R. Sensitivity of Cuscuta species and their hosts to Anethum graveolens essential oil. Pestic. I Fitomedicina 2023, 38, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilar, M.; Bayan, Y.; Aksit, H.; Onaran, A.; Kadioglu, I.; Yanar, Y. Bioherbicidal effects of essential oils isolated from Thymus fallax F., Mentha dumetorum Schult. and Origanum vulgare L. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 25, 4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, R.; Mathur, P. Functional attributes of microbial and plant based biofungicides for the defense priming of crop plants. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2022, 34, 301–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šernaitė, L.; Rasiukevičiūtė, N.; Valiuškaitė, A. The Extracts of cinnamon and clove as potential biofungicides against strawberry grey mould. Plants 2020, 9, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, P.K.; Deng, A.L.; Ogendo, J.O.; Kariuki, S.T.; Kamatenesi-Mugisha, M.; Mihale, J.M.; Torto, B. Residual contact toxicity and repellence of Cupressus lusitanica Miller and Eucalyptus saligna Smith essential oils against major stored product insect pests. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2017, 110, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubiri, S.; Baaliouamer, A. Potentiality of plants as source of insecticide principles. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2014, 18, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Kaur, A. Control of insect pests in crop plants and stored food grains using plant saponins: A review. LWT 2018, 87, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.L.; Campos, E.V.R.; Bakshi, M.; Abhilash, P.; Fraceto, L.F. Application of nanotechnology for the encapsulation of botanical insecticides for sustainable agriculture: Prospects and promises. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1550–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, P.; Nelson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant Soil. 2014, 383, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Horticult. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Jardin, P.; Xu, L.; Geelen, D. Agricultural Functions and Action Mechanisms of Plant Biostimulants (PBs) an Introduction. In The Chemical Biology of Plant Biostimulants; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in plant science: A global perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Michalak, I.; Dmytryk, A.; Wilk, R.; Gorecki, H. Innovative Natural Plant Growth Biostimulants; Studium Press LLC: Houston, TX, USA, 2014; pp. 451–489. [Google Scholar]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Vakhitov, V.A.; Ibragimov, R.I.; Yumaguzhin, M.S.; Kalimullina, Z.F. Metabolic changes in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under action of bioregulator stifun. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2011, 47, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.; Lubyanov, A.; Yakhin, I. Changes in cytokinin, auxin, and abscisic acid contents in wheat seedlings treated with the growth regulator Stifun. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 59, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, L.; Cinti, S.; Righetti, L.; Stefan, A.; Matteo, R.; D’Avino, L.; Lazzeri, L. Production of an enzymatic protein hydrolyzate from defatted sunflower seed meal for potential application as a plant biostimulant. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 75, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.; Siddhuraju, P.; Becker, K. Plant Secondary Metabolites; Springer: Humana Totowa, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 393. [Google Scholar]

- Šernaitė, L. Plant extracts: Antimicrobial and antifungal activity and appliance in plant protection. Sodinink. Daržinink 2017, 36, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hegedűs, G.; Kutasy, B.; Kiniczky, M.; Decsi, K.; Juhász, Á.; Nagy, Á.; Pallos, J.P.; Virág, E. Liposomal formulation of botanical extracts may enhance yield triggering PR genes and phenylpropanoid pathway in Barley (Hordeum vulgare). Plants 2022, 11, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decsi, K.; Kutasy, B.; Hegedűs, G.; Alföldi, Z.P.; Kálmán, N.; Nagy, Á.; Virág, E. Natural immunity stimulation using ELICE16INDURES® plant conditioner in field culture of soybean. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.F.; Al-Yasi, H.M.; Issa, A.A.; Hessini, K.; Hassan, F.A. Ginger extract and fulvic acid foliar applications as novel practical approaches to improve the growth and productivity of Damask Rose. Plants 2022, 11, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouch, R.; Kthiri, Z.; Soufi, S.; Jabeur, M.B.; Bettaieb, T. Assessing the biostimulant effect of micro-algae and thyme essential oil during in-vitro and ex-vitro rooting of strawberry. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 162, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jabeur, M.; Vicente, R.; López-Cristoffanini, C.; Alesami, N.; Djébali, N.; Gracia-Romero, A.; Serret, M.D.; López-Carbonell, M.; Araus, J.L.; Hamada, W. A novel aspect of essential oils: Coating seeds with thyme essential oil induces drought resistance in wheat. Plants 2019, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diretto, G.; Rubio-Moraga, A.; Argandoña, J.; Castillo, P.; Gómez-Gómez, L.; Ahrazem, O. Tissue-specific accumulation of sulfur compounds and saponins in different parts of garlic cloves from purple and white ecotypes. Molecules 2017, 22, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, B.; Suman, B.; Venkataswamy, M.; Thyagaraju, K. A study on phytochemicals, functional groups and mineral composition of Allium sativum (garlic) cloves. Int. J. Curr. Pharm. Res. 2017, 9, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L.D. Garlic: A review of its medicinal effects and indicated active compounds. Blood 1998, 179, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougou, I.; Boughalleb-M’hamdi, N. Biocontrol of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae affecting citrus orchards in Tunisia by using indigenous Bacillus spp. and garlic extract. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest. Control 2018, 28, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perello, A.E.; Noll, U.; Slusarenko, A.J. In vitro efficacy of garlic extract to control fungal pathogens of wheat. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 1809–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfraz, M.; Nasim, M.J.; Jacob, C.; Gruhlke, M.C. Efficacy of allicin against plant pathogenic fungi and unveiling the underlying mode of action employing yeast based chemogenetic profiling approach. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusanmi, M.; Amadi, J. Studies on the antimicrobial properties and phytochemical screening of garlic (Allium sativum) extracts. EthnoLeaflets 2010, 2009, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Borlinghaus, J.; Albrecht, F.; Gruhlke, M.C.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Slusarenko, A.J. Allicin: Chemistry and biological properties. Molecules 2014, 19, 12591–12618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuettner, E.B.; Hilgenfeld, R.; Weiss, M.S. The active principle of garlic at atomic resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 46402–46407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, T.; Rabinkov, A.; Mirelman, D.; Wilchek, M.; Weiner, L. The mode of action of allicin: Its ready permeability through phospholipid membranes may contribute to its biological activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2000, 1463, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusarenko, A.J.; Patel, A.; Portz, D. Control of plant diseases by natural products: Allicin from garlic as a case study. Sustain. Dis. Manag. A Eur. Context 2008, 121, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, H.; Noll, U.; Störmann, J.; Slusarenko, A.J. Broad-spectrum activity of the volatile phytoanticipin allicin in extracts of garlic (Allium sativum L.) against plant pathogenic bacteria, fungi and Oomycetes. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2004, 65, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzaawely, A.A.; Ahmed, M.E.; Maswada, H.F.; Al-Araby, A.A.; Xuan, T.D. Growth traits, physiological parameters and hormonal status of snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) sprayed with garlic cloves extract. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 2018, 64, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.H.; Badr, E.A.; Sadak, M.S.; Khedr, H.H. Effect of garlic extract, ascorbic acid and nicotinamide on growth, some biochemical aspects, yield and its components of three faba bean (Vicia faba L.) cultivars under sandy soil conditions. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Cheng, Z.; Ahmad, H.; Ali, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, M. Garlic, from remedy to stimulant: Evaluation of antifungal potential reveals diversity in phytoalexin allicin content among garlic cultivars; allicin containing aqueous garlic extracts trigger antioxidants in cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, S.; Ahmad, H.; Ali, M.; Ren, K.; Cheng, Z. Aqueous garlic extract stimulates growth and antioxidant enzymes activity of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Ahmad, H.; Ali, M.; Hayat, K.; Khan, M.A.; Cheng, Z. Aqueous garlic extract as a plant biostimulant enhances physiology, improves crop quality and metabolite abundance, and primes the defense responses of receiver plants. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, S.; Solís-Gaona, S.; Valdés-Caballero, M.V.; Juárez-Maldonado, A.; Loredo-Treviño, A.; Benavides-Mendoza, A. Transcriptomics of biostimulation of plants under abiotic stress. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 583888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.; Tran, L.-S.P. Impacts of priming with silicon on the growth and tolerance of maize plants to alkaline stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.; Abdel Latef, A.A.; Hashem, A.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Gucel, S.; Tran, L.-S.P. Nitric oxide mitigates salt stress by regulating levels of osmolytes and antioxidant enzymes in chickpea. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Biostimulants in agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sible, C.N.; Seebauer, J.R.; Below, F.E. Plant biostimulants: A categorical review, their implications for row crop production, and relation to soil health indicators. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Devireddy, A.R.; Sengupta, S.; Azad, R.K.; Mittler, R. Systemic signaling during abiotic stress combination in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13810–13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dias, M.C.; Freitas, H. Drought and salinity stress responses and microbe-induced tolerance in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 591911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desoky, E.-S.M.; ElSayed, A.I.; Merwad, A.-R.M.; Rady, M.M. Stimulating antioxidant defenses, antioxidant gene expression, and salt tolerance in Pisum sativum seedling by pretreatment using licorice root extract (LRE) as an organic biostimulant. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 142, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.; Jaleel, C.A.; Salem, M.A.; Nabi, G.; Sharma, S. Roles of enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants in plants during abiotic stress. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2010, 30, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Koussevitzky, S.; Mittler, R.; Miller, G. ROS and redox signalling in the response of plants to abiotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, G.; Cocetta, G.; Trivellini, A.; Ferrante, A. Transcriptional regulation in rocket leaves as affected by salinity. Plants 2019, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Schumaker, K.S.; Guo, Y. Sumoylation of transcription factor MYB30 by the small ubiquitin-like modifier E3 ligase SIZ1 mediates abscisic acid response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12822–12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Xue, F.; Zhang, H.; Ji, W. Wheat NAC transcription factor TaNAC29 is involved in response to salt stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 96, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, A.; Pedrotti, L.; Wurzinger, B.; Anrather, D.; Simeunovic, A.; Weiste, C.; Valerio, C.; Dietrich, K.; Kirchler, T.; Nägele, T. SnRK1-triggered switch of bZIP63 dimerization mediates the low-energy response in plants. elife 2015, 4, e05828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-mediated transcriptional regulation in response to osmotic stress in plants. J. Plant Res. 2011, 124, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wu, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Lu, Q.; Song, M. Identification and Characterization of the HD-Zip Gene Family and Dimerization Analysis of HB7 and HB12 in Brassica napus L. Genes 2022, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkuwayti, M.; El-Sherif, F.; Yap, Y.-K.; Khattab, S. Foliar application of Moringa oleifera leaves extract altered stress-responsive gene expression and enhanced bioactive compounds composition in Ocimum basilicum. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.L.M.; Wiebke-Strohm, B.; Bredemeier, C.; Margis-Pinheiro, M.; de Brito, G.G.; Rechenmacher, C.; Bertagnolli, P.F.; de Sá, M.E.L.; Campos, M.d.A.; de Amorim, R.M.S. Expression of an osmotin-like protein from Solanum nigrum confers drought tolerance in transgenic soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Basu, A.; Kundu, S. Overexpression of a new osmotin-like protein gene (SindOLP) confers tolerance against biotic and abiotic stresses in sesame. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Cui, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.; Bortolini, C.; Chen, M.; Liu, L.; Dong, M. Nanoliposomes containing Eucalyptus citriodora as antibiotic with specific antimicrobial activity. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 2653–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Cota-Ruiz, K.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Valdes, C.; Medina-Velo, I.A.; Turley, R.S.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Manganese nanoparticles control salinity-modulated molecular responses in Capsicum annuum L. through priming: A sustainable approach for agriculture. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latef, A.A.H.A.; Alhmad, M.F.A.; Abdelfattah, K.E. The possible roles of priming with ZnO nanoparticles in mitigation of salinity stress in lupine (Lupinus termis) plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 36, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchikanti, P. Bioavailability and environmental safety of nanobiopesticides. In Nano-Biopesticides Today and Future Perspectives; Koul, O., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, B.D.; Gogle, D.P. Nano-biopesticides: Synthesis and applications in plant safety. In Nanobiotechnology Applications in Plant Protection: Volume 2; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 169–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeson, L.L. Nanosilver: US EPA’s pesticide office considers how best to proceed. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2010, 19, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Liu, Y.; Rahman, M.M.; Dharmarajan, R.; Duan, L.; Uddin, A.F.M.J.; Naidu, R. Nanobiopesticides: Composition and preparation methods. In Nano-Biopesticides Today and Future Perspectives; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 69–131. [Google Scholar]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Liu, Y.; Naidu, R. Nanoencapsulation, nano-guard for pesticides: A new window for safe application. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 1447–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurro, M.; Miguel-Rojas, C.; Pérez-de-Luque, A. Safe nanotechnologies for increasing the effectiveness of environmentally friendly natural agrochemicals. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2403–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Cui, B.; Zeng, Z. Development strategies and prospects of nano-based smart pesticide formulation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 66, 6504–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, B.D.; Tardy, B.L.; Pezhman, M.; Kämäräinen, T.; Linder, M.; Schreiner, W.H.; Magalhães, W.L.; Rojas, O.J. Controlled biocide release from hierarchically-structured biogenic silica: Surface chemistry to tune release rate and responsiveness. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, M.C.; Campos, E.V.R.; Monteiro, R.A.; do Espirito Santo Pereira, A.; de Freitas Proença, P.L.; Fraceto, L.F. Development of stimuli-responsive nano-based pesticides: Emerging opportunities for agriculture. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Nehra, M.; Dilbaghi, N.; Marrazza, G.; Hassan, A.A.; Kim, K.-H. Nano-based smart pesticide formulations: Emerging opportunities for agriculture. J. Control. Release 2019, 294, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattos, B.D.; Tardy, B.L.; Magalhaes, W.L.; Rojas, O.J. Controlled release for crop and wood protection: Recent progress toward sustainable and safe nanostructured biocidal systems. J. Control. Release 2017, 262, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahdokht, D.; Gao, Y.; Faramarz, S.; Poustforoosh, A.; Abbasi, M.; Asadikaram, G.; Nematollahi, M.H. Conventional agrochemicals towards nano-biopesticides: An overview on recent advances. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.-L.; Li, X.-G.; Zhu, F.; Lei, C.-L. Structural characterization of nanoparticles loaded with garlic essential oil and their insecticidal activity against Tribolium castaneum (Herbst)(Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10156–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, I.K.; Pirsa, S.; Tağı, Ş. Preparation of chitosan/zinc oxide/Melissa officinalis essential oil nano-composite film and evaluation of physical, mechanical and antimicrobial properties by response surface method. Polym. Test. 2019, 79, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.H.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Hassanin, M.M.; Al-Askar, A.A.; AbdElgawad, H.; Attia, M.S. Potential Impacts of Clove Essential Oil Nanoemulsion as Bio Fungicides against Neoscytalidium Blight Disease of Carum carvi L. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasoglu, T.; Mansuroglu, B.; Derman, S.; Gumus, B.; Kocyigit, B.; Acar, T.; Kocacaliskan, I. Enhancement of Antifungal Activity of Juglone (5-Hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone) Using a Poly (d, l-lactic-co-glycolic acid)(PLGA) Nanoparticle System. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 7087–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Yu, A.; Wang, G.; Zheng, F.; Hu, P.; Jia, J.; Xu, H. A novel water-based chitosan-La pesticide nanocarrier enhancing defense responses in rice (Oryza sativa L) growth. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 199, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L.; Gao, Z.; Feng, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q. Cellulose based materials for controlled release formulations of agrochemicals: A review of modifications and applications. J. Control. Release 2019, 316, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakiba, S.; Astete, C.E.; Paudel, S.; Sabliov, C.M.; Rodrigues, D.F.; Louie, S.M. Emerging investigator series: Polymeric nanocarriers for agricultural applications: Synthesis, characterization, and environmental and biological interactions. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Hu, Q.; Li, J.; Chao, Z.; Cai, C.; Yin, M.; Du, X.; Shen, J. A star polycation acts as a drug nanocarrier to improve the toxicity and persistence of botanical pesticides. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 17406–17413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Hwang, I.C.; Park, J.W.; Park, H.J. Photoprotection for deltamethrin using chitosan-coated beeswax solid lipid nanoparticles. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 1062–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Guenther, R.H.; Sit, T.L.; Lommel, S.A.; Opperman, C.H.; Willoughby, J.A. Development of abamectin loaded plant virus nanoparticles for efficacious plant parasitic nematode control. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 9546–9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chariou, P.L.; Dogan, A.B.; Welsh, A.G.; Saidel, G.M.; Baskaran, H.; Steinmetz, N.F. Soil mobility of synthetic and virus-based model nanopesticides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chariou, P.L.; Steinmetz, N.F. Delivery of pesticides to plant parasitic nematodes using tobacco mild green mosaic virus as a nanocarrier. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4719–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, G.; Dai, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, B.; Bian, P.; Zheng, K.; Wu, Z.; Cai, D. Fabrication of light-responsively controlled-release herbicide using a nanocomposite. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 349, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabihi, A.; Basti, A.A.; Amoabediny, G.; Khanjari, A.; Bazzaz, J.T.; Mohammadkhan, F.; Bargh, A.H.; Vanaki, E. Physicochemical Characteristics of Nanoliposome Garlic (Allium sativum L.) Essential Oil and Its Antibacterial Effect on Escherichia coli O157: H7. J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2017, 4, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Lu, P.-M.; Piao, J.-H.; Xu, X.-L.; Chen, J.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, J.-G. Preparation and physicochemical characteristics of an allicin nanoliposome and its release behavior. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, T.; Vestine, A.; Kim, K.D.; Kwon, S.J.; Sivanesan, I.; Chun, S.C. Antibacterial activity of nanoparticles of garlic (Allium sativum) extract against different bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans and Poryphormonas gingivalis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallito, C.J.; Bailey, J.H. Allicin, the antibacterial principle of Allium sativum. I. Isolation, physical properties and antibacterial action. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1944, 66, 1950–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Rojas, D.F.; de Souza, C.R.F.; Oliveira, W.P. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): A precious spice. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Rojas, D.F.; Souza, C.R.; Oliveira, W.P. Encapsulation of eugenol rich clove extract in solid lipid carriers. J. Food Eng. 2014, 127, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggini, V.; Semenzato, G.; Gallo, E.; Nunziata, A.; Fani, R.; Firenzuoli, F. Antimicrobial activity of Syzygium aromaticum essential oil in human health treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.-K.; Kamal, M.; Ayuba, S.; Sakirolla, R.; Kang, Y.-B.; Mohandas, K.; Balijepalli, M.; Ahmad, S.; Pichika, M. A comprehensive review on eugenol’s antimicrobial properties and industry applications: A transformation from ethnomedicine to industry. Phcog. Rev. 2019, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.M.; Kamaruddin, A.H.; Nadzir, M.M. A review on extraction, antimicrobial activities and toxicology of cinnamomum Cassia in future food protection. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2023, 13, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarasu, P.; Kim, M.; McClements, D.J.; Kinchla, A.J.; Moore, M.D. Inactivation of Viruses by Charged Cinnamaldehyde Nanoemulsions. Foods 2025, 14, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molania, T.; Saeedi, M.; Morteza-Semnani, K.; Negarandeh, R.; Hosseinnataj, A.; Lotfizadeh, A.; Fadaei, H.; Jafari, A.; Salehi, M.; Haghani, I. Antifungal efficacy of cinnamaldehyde and nano-cinnamaldehyde particles against candidiasis: An in-vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, K.A.; Mohammed, S.A.; Khan, O.; Ali, H.M.; El-Readi, M.Z.; Mohammed, H.A. Cinnamaldehyde-based self-nanoemulsion (CA-SNEDDS) accelerates wound healing and exerts antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects in rats’ skin burn model. Molecules 2022, 27, 5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, R.; Napoli, E.; Granata, G.; Di Vito, M.; Garzoli, S.; Geraci, C.; Rizzo, S.; Torelli, R.; Sanguinetti, M.; Bugli, F. Study of the chemical profile and anti-fungal activity against Candida auris of Cinnamomum cassia essential oil and of its nano-formulations based on polycaprolactone. Plants 2023, 12, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbeltagi, S.; Alharbi, H.M.; Aodah, A.H.; Eldin, Z.E. Investigation and optimization of naringin-loaded in MOF-5 encapsulated by liponiosomes as smart drug delivery, cytotoxicity, and apoptotic on breast cancer cells. Version 1. Res. Sq. Prepr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Azim, W.M.A.; Balah, M.A. Nanoemulsions formation from essential oil of Thymus capitatus and Majorana hortensis and their use in weed control. Indian J. Weed Sci. 2016, 48, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemaa, M.B.; Falleh, H.; Serairi, R.; Neves, M.A.; Snoussi, M.; Isoda, H.; Nakajima, M.; Ksouri, R. Nanoencapsulated Thymus capitatus essential oil as natural preservative. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 45, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hao, K.; Yu, F.; Shen, L.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Su, C. Field application of nanoliposomes delivered quercetin by inhibiting specific hsp70 gene expression against plant virus disease. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.I.; Monteiro, M.; Araújo, A.R.; Rodrigues, A.R.O.; Castanheira, E.M.; Pereira, D.M.; Olim, P.; Fortes, A.G.; Gonçalves, M.S.T. Cytotoxic plant extracts towards insect cells: Bioactivity and nanoencapsulation studies for application as biopesticides. Molecules 2020, 25, 5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e Santos, P.C.; Granero, F.O.; Junior, J.L.B.; Pavarini, R.; Pavarini, G.M.P.; Chorilli, M.; Zambom, C.R.; Silva, L.P.; da Silva, R.M.G. Insecticidal activity of Tagetes erecta and Tagetes patula extracts and fractions free and microencapsulated. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 45, 102511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashamaite, C.V.; Ngcobo, B.L.; Manyevere, A.; Bertling, I.; Fawole, O.A. Assessing the Usefulness of Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract as a Biostimulant to Supplement Synthetic Fertilizers: A Review. Plants 2022, 11, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trucillo, P.; Campardelli, R.; Reverchon, E. Liposomes: From bangham to supercritical fluids. Processes 2020, 8, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P.I. Toxicity of some charged lipids used in liposome preparations. Cytobios 1983, 37, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jogaiah, S.; Singh, H.B.; Fernandes-Fraceto, L.; De Lima, R. Advances in Nano-Fertilizers and Nano-Pesticides in Agriculture; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussan, E.; Cassel, S.; Blanzat, M.; Rico-Lattes, I. Drug delivery by soft matter: Matrix and vesicular carriers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, M.R. Nanocarrier Technologies: Frontiers of Nanotherapy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chawda, P.J.; Shi, J.; Xue, S.; Young Quek, S. Co-encapsulation of bioactives for food applications. Food Qual. Saf. 2017, 1, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, S.; Azadmard-Damirchi, S.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Valizadeh, H.; Hesari, J. Liposomes as carrier vehicles for functional compounds in food sector. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2016, 11, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, Y.; Farshbaf, M.; Mohammadhosseini, M.; Mirahadi, M.; Khalilov, R.; Saghfi, S.; Akbarzadeh, A. Recent advances on liposomal nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrychenko, A.; Kovalenko, O. Prospects of Liposomes Application in Agriculture. Mikrobiolohichnyi Zhurnal 2025, 87, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, S.A.; Misaghi, A.; Moosavy, M.-H.; Amoabediny, G.; Basti, A.A. Effect of preparation methods on the properties of Zataria multiflora Boiss. essential oil loaded nanoliposomes: Characterization of size, encapsulation efficiency and stability. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 20, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, M. A review on application of encapsulation in agricultural processes. In Encapsulation of Active Molecules and Their Delivery System; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jíménez-Arias, D.; Morales-Sierra, S.; Silva, P.; Carrêlo, H.; Gonçalves, A.; Ganança, J.F.T.; Nunes, N.; Gouveia, C.S.; Alves, S.; Borges, J.P. Encapsulation with natural polymers to improve the properties of biostimulants in agriculture. Plants 2022, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carrasco, M.; Valdez-Baro, O.; Cabanillas-Bojórquez, L.A.; Bernal-Millán, M.J.; Rivera-Salas, M.M.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Heredia, J.B. Potential agricultural uses of micro/nano encapsulated chitosan: A review. Macromol 2023, 3, 614–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyaril, S.S.; Shanableh, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Rawas-Qalaji, M.; Cagliani, R.; Shabib, A.G. Recent progress in micro and nano-encapsulation techniques for environmental applications: A review. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Mozafari, M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Hamidi, M.; Hajimolaali, M.; Katouzian, I. Industrial-scale methods for the manufacture of liposomes and nanoliposomes: Pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and nutraceutical aspects. Micro Nano Bio Asp. 2022, 1, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Janik, M.; Hanula, M.; Khachatryan, K.; Khachatryan, G. Nano-/Microcapsules, liposomes, and micelles in polysaccharide carriers: Applications in food technology. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzuto, G.; Molinari, A. Liposomes as nanomedical devices. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 975–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, T.; Ganapathyswamy, H. An overview of liposomal nano-encapsulation techniques and its applications in food and nutraceutical. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 3545–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, M.R. Nanoliposomes: Preparation and analysis. In Liposomes: Methods and Protocols, Volume 1: Pharmaceutical Nanocarriers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dragovic, R.A.; Gardiner, C.; Brooks, A.S.; Tannetta, D.S.; Ferguson, D.J.; Hole, P.; Carr, B.; Redman, C.W.; Harris, A.L.; Dobson, P.J. Sizing and phenotyping of cellular vesicles using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2011, 7, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaei, M.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, y.M. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, M.; Hofmann, T. Nanopesticide research: Current trends and future priorities. Environ. Int. 2014, 63, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and zeta potential–what they are and what they are not? J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soppimath, K.S.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Kulkarni, A.R.; Rudzinski, W.E. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles as drug delivery devices. J. Control. Release 2001, 70, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangenechten, B.; De Coninck, B.; Ceusters, J. How to improve the potential of microalgal biostimulants for abiotic stress mitigation in plants? Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1568423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B. Plant essential oils for pest and disease management. Crop Prot. 2000, 19, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, O.; Walia, S.; Dhaliwal, G. Essential oils as green pesticides: Potential and constraints. Biopestic. Int. 2008, 4, 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pavela, R.; Benelli, G. Essential oils as ecofriendly biopesticides? Challenges and constraints. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karny, A.; Zinger, A.; Kajal, A.; Shainsky-Roitman, J.; Schroeder, A. Therapeutic nanoparticles penetrate leaves and deliver nutrients to agricultural crops. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, C.M.B.; Brandelli, A. Antimicrobial activity of nanoliposomes co-encapsulating nisin and garlic extract against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in milk. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 36, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gortzi, O.; Lalas, S.; Chinou, I.; Tsaknis, J. Evaluation of the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Origanum dictamnus extracts before and after encapsulation in liposomes. Molecules 2007, 12, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Haghirosadat, B.F.; larypoor, M.; Ehsani, R.; Yazdian, F.; Rashedi, H.; Jahanizadeh, S.; Rahmani, A. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of liponiosome containing ginger extract as a new strategy for potent antifungal formulation. J. Clust. Sci. 2020, 31, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Ertaş, N.; Demir, M.K. Storage stability, heat stability, controlled release and antifungal activity of liposomes as alternative fungal preservation agents. Food Biosci. 2023, 51, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, C.M.B.; Thys, R.C.S.; Brandelli, A. Antifungal properties of phosphatidylcholine-oleic acid liposomes encapsulating garlic against environmental fungal in wheat bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 293, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, M.; Donadel, O.J.; Ardanaz, C.E.; Tonn, C.E.; Sosa, M.E. Toxic and repellent effects of Baccharis salicifolia essential oil on Tribolium castaneum. Pest. Manag. Sci. Former. Pestic. Sci. 2005, 61, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, Z.; Shakarami, J.; Varshosaz, J.; Jafari, S. Encapsulation of essential oils of Mentha pulegium and Ferula gummosa using nanoliposome technology as a safe botanical pesticide. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 7, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant Extract, Active Compound | Nano-Formulation Type | Main Biological Target Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garlic (Allium sativum) allicin, essential oil | Liposomes; PEG-coated nanoparticles | Antibacterial (E. coli, Listeria), antifungal (Penicillium spp.), insecticidal (Tribolium castaneum) | [102,103,104,105] |

| Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) eugenol | Nanoemulsion; solid-lipid nanoparticles | Antifungal (Botrytis, Aspergillus), antioxidant | [91,106,107,108,109] |

| Cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia) cinnamaldehyde | Liposomes; nanoemulsion | Antifungal, antiviral (broad-spectrum) | [110,111,112,113,114] |

| Ginger (Zingiber officinale) gingerol, shogaol | Liponiosomes; nanocapsules | Antifungal (Aspergillus spp.), antioxidant enhancement | [115] |

| Thyme (Thymus capitatus) thymol, carvacrol | Nanoemulsion; seed coating (biostimulant) | Drought tolerance; enhanced rooting and phenolic metabolism | [37,116,117] |

| Quercetin (plant flavonoid) | Lecithin liposomes | Antiviral (Tobacco mosaic virus) | [118] |

| Ruta graveolens dichloromethane extract | Liposomes; chitosan nanostructure | Insecticidal (Spodoptera frugiperda) | [119] |

| Tagetes erecta, T. patula ethanolic extract | Multilamellar liposomes (DPPC) | Insecticidal (Sitophilus zeamais larvae) | [120] |

| Melissa officinalis essential oil | Chitosan ZnO nanocomposite film | Antibacterial (Escherichia coli), food-preservative potential | [90] |

| Moringa oleifera leaf extract | Nanocapsule, foliar nanoformulation | Salinity-stress tolerance; antioxidant enzyme induction | [71,121] |

| Stress Type | Promising Biostimulant Sources | Key Bioactive Components | Advantages of Micro-, Nanoencapsulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy metal stress | Macroalgae extracts; polyphenol-rich plant materials (e.g., tree leaves, agro-industrial by-products) | Polyphenols, flavonoids, polysaccharides | Enhanced stability, improved bioavailability, controlled release, increased metal-chelating and antioxidant activity |

| Drought stress | Macroalgae; woody plant tissues; osmoprotectant-rich extracts | Betaines, polysaccharides, phytohormone-like compounds | Prolonged activity, improved stress signaling modulation, reduced degradation under field conditions |

| Herbivory, pest attack | Allium species; aromatic and medicinal plants | Sulfur-containing compounds, terpenoids, essential oil components | Reduced volatility, enhanced persistence, controlled release, improved efficacy at lower doses |

| Oxidative stress (general) | Diverse plant extracts; algae-derived biostimulants | Antioxidants, phenolics, carotenoids | Improved formulation stability, sustained antioxidant delivery, enhanced plant tissue penetration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kutasy-Takács, B.; Pallos, J.P.; Kiniczky, M.; Hegedűs, G.; Virág, E. Plant-Derived Biostimulants and Liposomal Formulations in Sustainable Crop Protection and Stress Tolerance. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010490

Kutasy-Takács B, Pallos JP, Kiniczky M, Hegedűs G, Virág E. Plant-Derived Biostimulants and Liposomal Formulations in Sustainable Crop Protection and Stress Tolerance. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010490

Chicago/Turabian StyleKutasy-Takács, Barbara, József Péter Pallos, Márta Kiniczky, Géza Hegedűs, and Eszter Virág. 2026. "Plant-Derived Biostimulants and Liposomal Formulations in Sustainable Crop Protection and Stress Tolerance" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010490

APA StyleKutasy-Takács, B., Pallos, J. P., Kiniczky, M., Hegedűs, G., & Virág, E. (2026). Plant-Derived Biostimulants and Liposomal Formulations in Sustainable Crop Protection and Stress Tolerance. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010490