Abstract

Reinforced concrete shear wall structures (RCSWs) are commonly used as explosion-resistant chambers for storing hazardous chemical materials and housing high-pressure reaction equipment, serving to isolate blast waves and prevent chain reactions. In this study, full-scale experiments and numerical simulations were conducted to investigate the blast resistance of RC shear wall protective structures subjected to internal explosions. A full-scale RC shear wall structure measuring 9.7 m × 8 m × 6.95 m with a wall thickness of 0.8 m was constructed, and an internal detonation equivalent to 200 kg of TNT was initiated to simulate the extreme loading conditions that may occur in explosion control chambers. Based on experimental data analysis and numerical simulation results, the damage mechanisms and dynamic response characteristics of the structure were clarified. The results indicate that under internal explosions, severe damage first occurs at the wall–joint regions, primarily exhibiting through-thickness shear cracking near the supports. The structural damage process can be divided into two stages: local response and global response. Using validated finite element models, a parametric study was carried out to determine the influence of TNT charge weight and reinforcement configuration on the structural dynamic response. The findings of this research provide theoretical references for the design and strengthening of blast-resistant structures.

1. Introduction

In chemical and energy production industries, accidental explosions of high-pressure reactors and raw material storage facilities often result in severe loss of life and property [1]. An effective approach to mitigating such explosion hazards is to construct robust protective structures that isolate hazardous devices and incorporate venting designs to redirect blast waves away from adjacent equipment, thereby preventing secondary or chain explosions [2,3,4]. Compared with free-field explosions of the same charge weight, internal explosions generate significantly higher peak overpressures and impulses due to reflection and confinement effects, which in turn lead to distinct structural responses and failure mechanisms [5]. Farrimond et al. [6] investigated TNT detonations in confined air environments and reported that enhanced combustion under constrained conditions can substantially increase the peak internal pressure. Guo et al. [7] conducted scaled TNT internal explosion tests on reinforced concrete shear wall structures, revealing that, relative to free-field conditions, the peak overpressure at different locations increased by approximately two to eleven times. Moreover, the expansion of detonation products compresses the air within the enclosure, producing a quasi-static pressure phase of comparatively long duration following the initial pressure peak, whereas the positive pressure phase of free-field explosions is typically shorter and decays rapidly [8,9].

Yang et al. [10,11] conducted full-scale experimental studies on reinforced concrete (RC) beams subjected to contact explosions. At the explosion center, the beams experienced severe penetration damage; although the reinforcing bars remained intact, extensive concrete spalling and material loss occurred, leading to the formation of plastic hinges. Wang et al. [12] performed blast tests on RC slabs with side lengths ranging from 0.75 m to 1.25 m under different scaled standoff distances. The results indicated that, under identical charge weights and standoff distances, larger slabs exhibited more severe penetration damage. The scaled distance had a pronounced effect on the damage mode of the slabs— as the distance increased, the failure pattern gradually shifted from localized damage to overall structural damage.

Ruggiero et al. [13] carried out full-scale blast resistance tests on a 3.6 m × 4 m × 0.34 m reinforced concrete slab. Under contact detonation, a distinct penetration zone developed at the mid-span. However, owing to the relatively large size and thickness of the slab, the damage was confined to the vicinity of the explosion center, and cracks did not propagate toward the supports. Dua et al. [14] experimentally investigated contact explosions at the ends of concrete columns and found that columns with different cross-sectional geometries exhibited varying degrees of damage. Square columns sustained more severe damage than rectangular ones, as the latter shape effectively reduced the transmission of blast waves to the rear side of the column. Xiao et al. [15] explored the damage mechanisms of arched concrete slabs under contact explosions at various locations and concluded that stress wave reflection was the primary cause of concrete damage. This phenomenon also explains why highly localized damage is commonly observed in experimental studies of concrete components. Chu et al. [16] examined the propagation characteristics of blast-induced stress waves in concrete. When the scaled standoff distance was small (<0.25 m/kg1/3), the stress wave exhibited an exponential attenuation trend; as the standoff distance increased, the attenuation curve became non-monotonic and resembled a pulse with multiple peak values.

While these experimental studies have provided valuable data on the local damage of individual components, they primarily focused on contact or close-in explosions. Consequently, although these studies effectively captured localized failures, they could not fully reflect the complex interaction between blast waves and the structural system, particularly the superposition effects of blast waves within semi-confined spaces.

Under blast loading, concrete damage is primarily governed by tensile, shear, and flexural failures. Therefore, concrete materials with superior tensile performance have become a major focus of recent research. Li et al. [17,18,19] conducted blast tests on ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) slabs with thicknesses ranging from 100 mm to 150 mm. Under a 1 kg TNT charge, the crater diameter on the UHPC slabs was reduced by approximately 50% compared with that of normal concrete, and both the maximum fragment size and total number of fragments were significantly smaller. In addition to directly increasing the matrix strength, fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) has also demonstrated excellent performance in resisting blast loading, particularly in mitigating punching and spalling failures.

Zhao et al. [20] experimentally investigated the blast resistance of steel fiber–reinforced concrete (SFRC) slabs and found that when the steel fiber content was approximately 1.3% by volume, the enhancement in blast resistance was maximized. Yang et al. [21] performed full-scale blast tests on 2 m × 2 m × 0.4 m SFRC slabs and conducted a parametric study on the fiber length and diameter. Their results indicated that decreasing the fiber length, increasing the aspect ratio, and raising the fiber volume fraction all significantly improved the slab’s anti-spalling performance.

Despite significant advancements in High-Performance Concrete (HPC) materials, their practical engineering application remains challenged by construction difficulties and high costs. Ultra-High-Performance Concrete (UHPC) is prone to early-age cracking due to autogenous shrinkage and localized thermal concentration, while Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete (SFRC) faces limitations during casting and vibration, particularly in regions with dense reinforcement. For large-scale protective structures, the use of HPC often entails prohibitive costs. In contrast, conventional reinforced concrete remains the most widely used form for protective structures due to its material availability, moderate cost, and mature construction techniques. Therefore, it remains necessary to investigate the failure mechanisms of shear wall structures constructed with normal concrete under extreme internal blast loads.

Reinforcement plays a critical role in determining the blast resistance of concrete structures. At larger standoff distances, flexural effects become more dominant, and the reinforcement begins to carry tensile loads. An appropriate reinforcement configuration can enhance ductility during the flexural response stage and reduce the propagation rate of cracks. Wu et al. [22] conducted blast tests on concrete slabs with various reinforcement layouts and reported that, for the same reinforcement ratio, slabs with double-layer reinforcement exhibited superior deformation capacity compared to those with a single reinforcement layer. As the standoff distance increased, the rebound peak displacement of double-layer slabs was significantly lower than that of single-layer slabs. Thiagarajan et al. [23], using a Blast Load Simulator, investigated the influence of high-strength and conventional reinforcing bars on the blast response of concrete slabs. Their results showed that the use of high-strength reinforcement reduced the central deflection of the slab by approximately 12.7%.

Zhou et al. [24] conducted experimental studies on reinforced concrete (RC) beams coated with sprayed polyurea. The addition of the polyurea layer reduced the peak and residual displacements at the beam mid-span by 74.8% and 73.7%, respectively. Within a TNT equivalent range of 0.3–10 kg, a 1.5 mm-thick polyurea coating increased the beam’s equivalent TNT resistance by approximately 25%. Both concrete and reinforcing steel exhibit pronounced strain-rate sensitivity under high-rate loading conditions. The dynamic compressive and tensile strengths of concrete can increase by one to five times depending on the strain rate; however, its brittle fracture and fragmentation behavior also become more complex [25,26,27]. Although the dynamic strength enhancement may partially resist short-duration peak pressures, it cannot counteract the global failure caused by large impulses or quasi-static pressures.

However, most of the aforementioned tests were conducted on individual components with idealized boundary conditions. Under internal blast loading, the joint regions connecting adjacent members often experience significant stress concentrations, potentially leading to joint failure occurring prior to component failure. Therefore, investigating the damage mechanism of unsimplified wall–slab joints within a full-scale structure is crucial for evaluating global structural safety and preventing progressive collapse.

Although extensive research has been achieved regarding the blast resistance of concrete structures, most studies rely on small-scale experiments and scaled models, which cannot accurately reflect the realistic mechanical response of large-scale structures under blast loading. Due to scale effects, full-scale structures may exhibit failure modes significantly different from those of scaled models; hence, it is necessary to conduct research on the blast resistance of full-scale Reinforced Concrete Shear Walls (RCSWs).

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Model Dimensions and Reinforcement

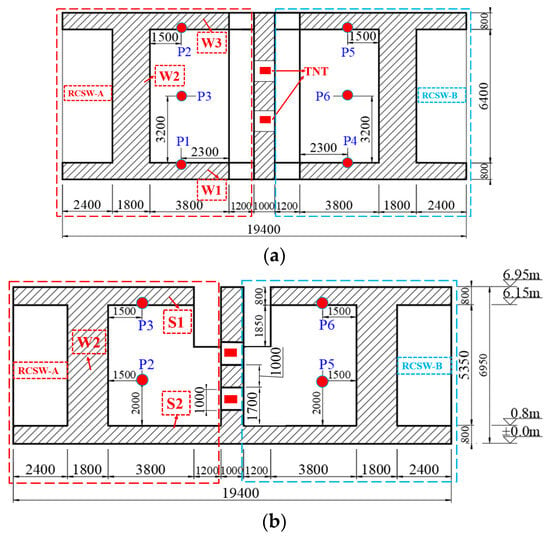

The test specimen is a Reinforced Concrete Shear Wall (RCSW) structure. Its design is based on the typical dimensions of hazardous chemical storage chambers and high-pressure reactor facilities widely employed in the chemical and energy industries. The thickness of the foundation, walls, and roof slab was uniformly set to 0.8 m. The clear height between the foundation and the top of the slab was 5.35 m, while the overall length and width of the structure were 9.7 m and 8 m, respectively. The structure was designed in accordance with GB/T50779-2022 [28]. For protective structures designed to withstand internal explosions, a fully sealed configuration would result in excessively high construction costs, as extremely thick walls and dense reinforcement would be required. Therefore, blast vent openings are generally incorporated at the top of the structure to prevent the development of excessively high internal pressures that could cause structural failure. In the experimental specimen, a blast vent measuring 1.2 m × 8 m × 2.65 m was provided at the top. Except for this vent, all other regions of the structure were fully sealed, with no doors or windows.

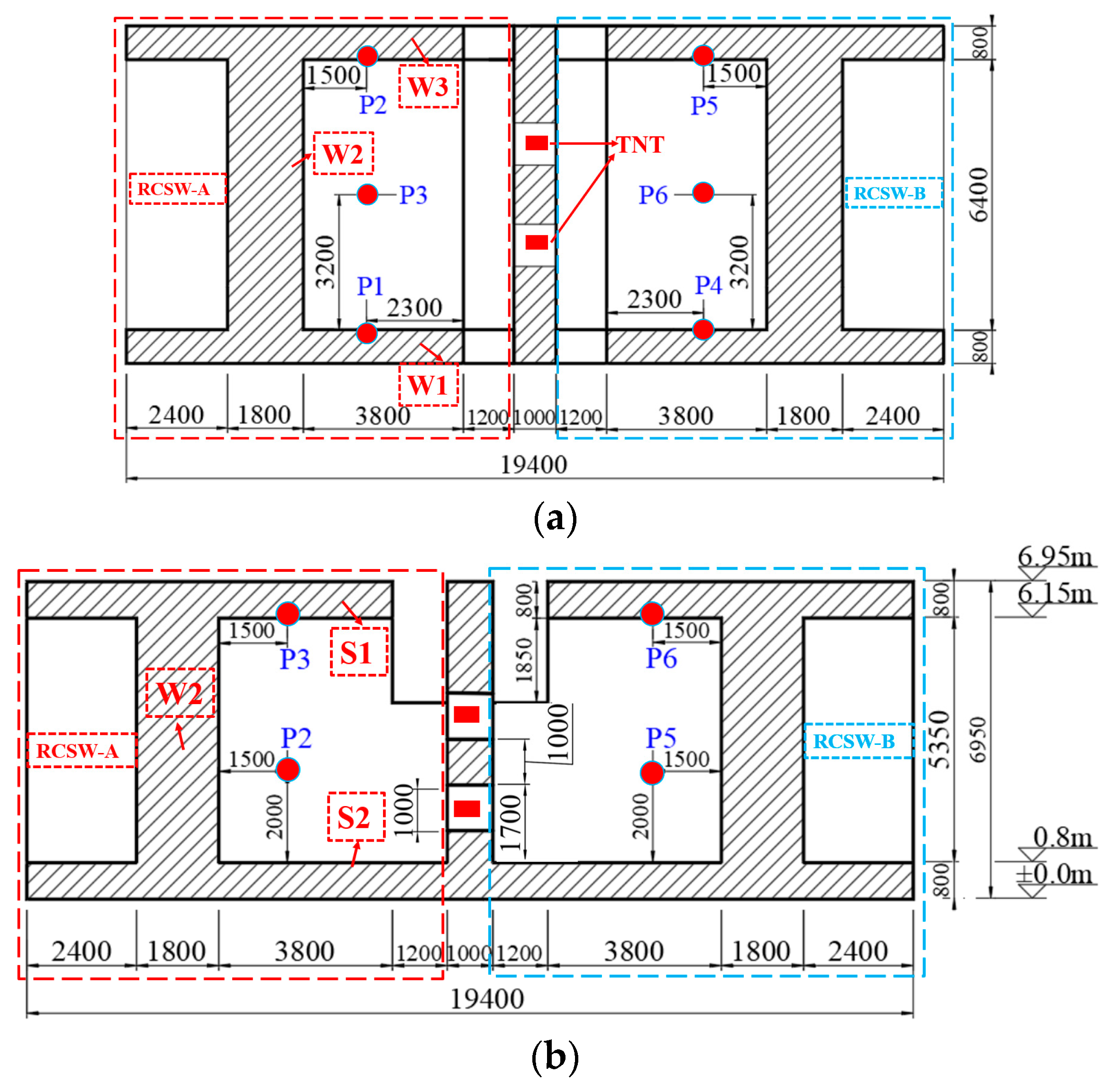

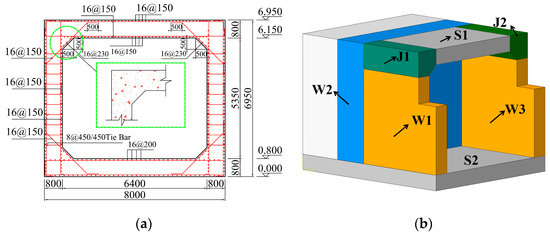

The walls at both lateral ends had a thickness of 1.8 m and were additionally reinforced. During subsequent experiments and numerical simulations, both end walls exhibited sufficient stiffness and were treated as rigid supports. Figure 1 illustrates the geometric dimensions of the structure and the locations of the blast pressure sensors (P1~P6). (The values in the figure are all in millimeters)

Figure 1.

Structural geometry and positions of blast pressure measurement points. (a) Horizontal sectional view (mm). (b) Vertical sectional view (mm).

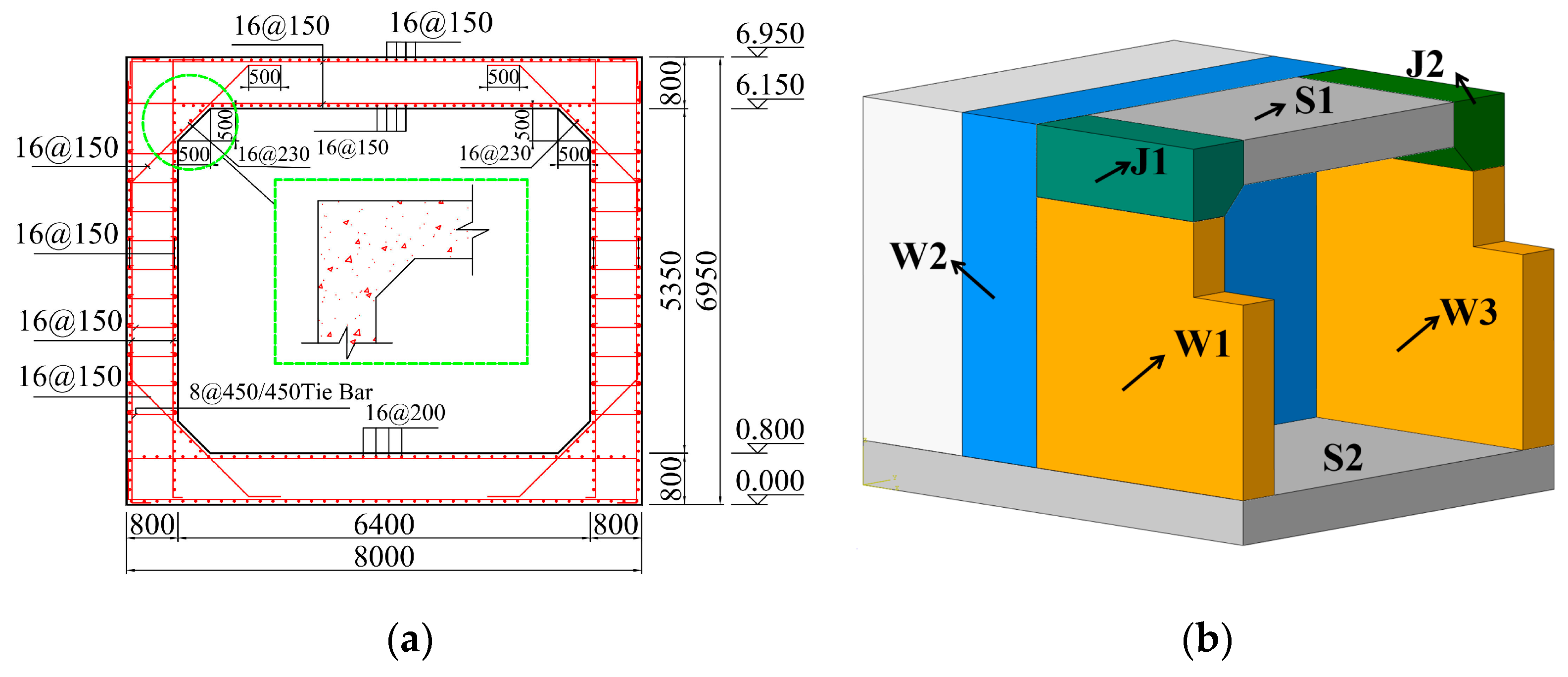

Both the walls and slabs were reinforced with double layers of reinforcement. The horizontal and vertical reinforcements were HPB400 grade with a diameter of 16 mm. The spacing of both transverse and longitudinal rebars was 150 mm, with a tie bar of 8 mm diameter provided every 450 mm. Chamfers were added at the wall–slab joints, and diagonal rebars were arranged along the chamfered surfaces. The reinforcement ratio of the wall panels was 0.33%. The reinforcement layout and the names of each component of specimen RCSW-A are shown in Figure 2. The concrete used had a strength grade of C40. Mechanical property tests were conducted on the concrete and reinforcement used in the experiments. The concrete was sourced from the commercial ready-mixed concrete batching plant nearest to the test site, while the steel reinforcement was supplied by a local steel processing center. Mechanical property tests on the reinforcement were conducted prior to fabrication and assembly, and concrete strength tests were performed prior to casting. The measured properties of the concrete and steel are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional reinforcement layout and component names of RCSW-A. (a) Reinforcement layout of the cross-section. (b) Component names of RCSW-A.

Table 1.

Measured mechanical properties of concrete and reinforcement.

2.2. Blast Sources and Sensors

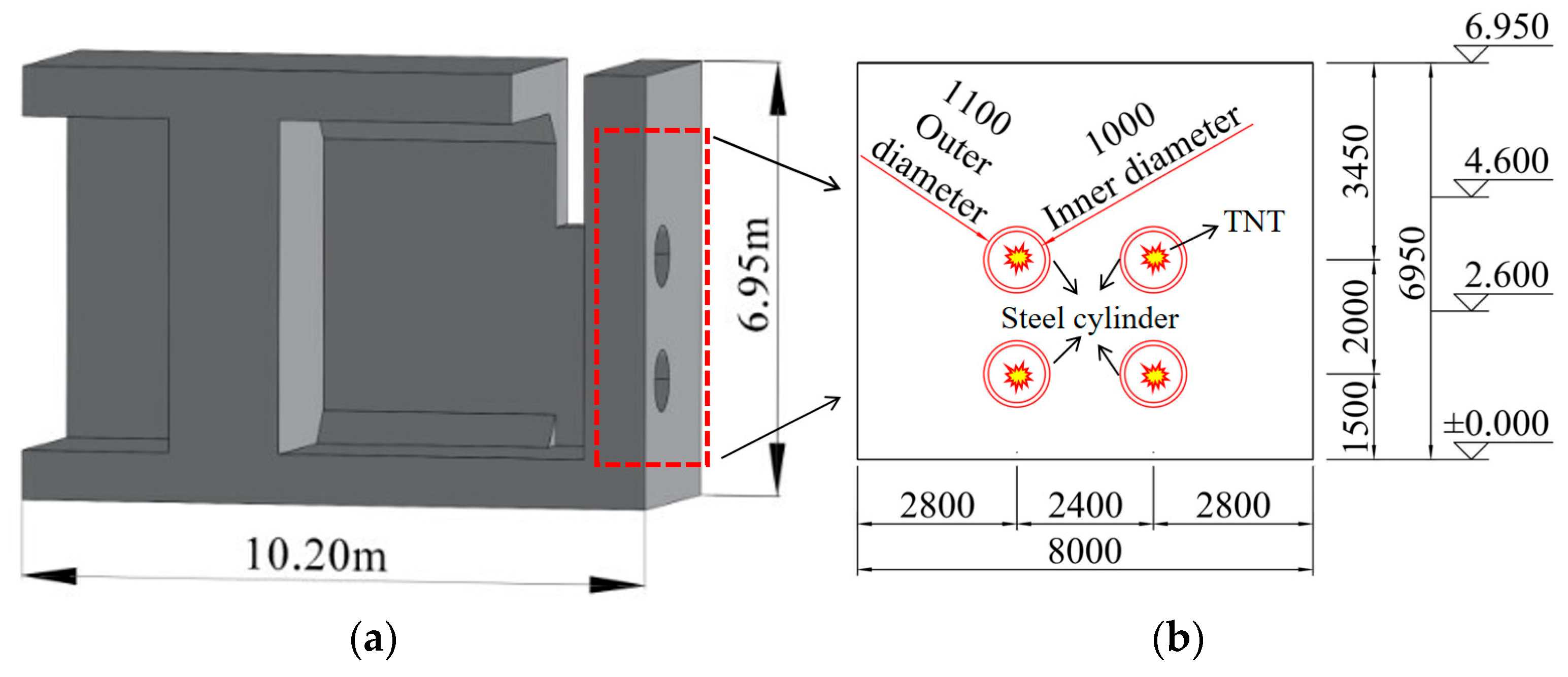

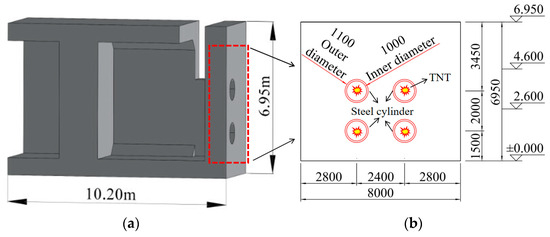

In practice, high-pressure storage installations may consist of multiple storage units; when one or more units detonate in sequence due to a chain reaction, multiple blast origins can be produced. In semi-confined spaces, the propagation, superposition, and reflection of blast waves lead to a multi-peaked pressure field that differs markedly from the idealized single-point blast model. Multi-point detonations therefore better reproduce the typical loading features that a protective structure may experience: compared with a single concentrated charge, multiple simultaneous charges induce more complex internal shock wave interactions and thus more realistically reflect the loading and failure mechanisms of structures under realistic explosion scenarios. For these reasons, the blast load in this study was applied by simultaneously initiating four charge locations.

A reinforced concrete partition wall (1.0 m thick) was installed at the centerline between specimens RCSW A and RCSW B. Four steel sleeves (internal diameter = 1.0 m, wall thickness = 50 mm) were embedded within this wall. Each steel sleeve contained 50 kg of TNT, giving a total charge weight of 200 kg. The TNT uses rectangular blocks measuring 100 mm × 50 mm × 25 mm and arranged on wooden supports to form an approximately cylindrical charge with a length-to-diameter ratio close to 1:1. The axes of the TNT assemblies were coaxial with the steel sleeves. Approximately 1000 TNT blocks were used in total. Detonation cord was routed through the center of the TNT assemblies to interconnect the four steel sleeves, ensuring simultaneous initiation of all charges. Figure 3 presents a three-dimensional semi-schematic view of RCSW A and the explosive charge configuration.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of Explosion Source Setup. (a) Semi-schematic view of RCSW-A. (b) Explosive source configuration.

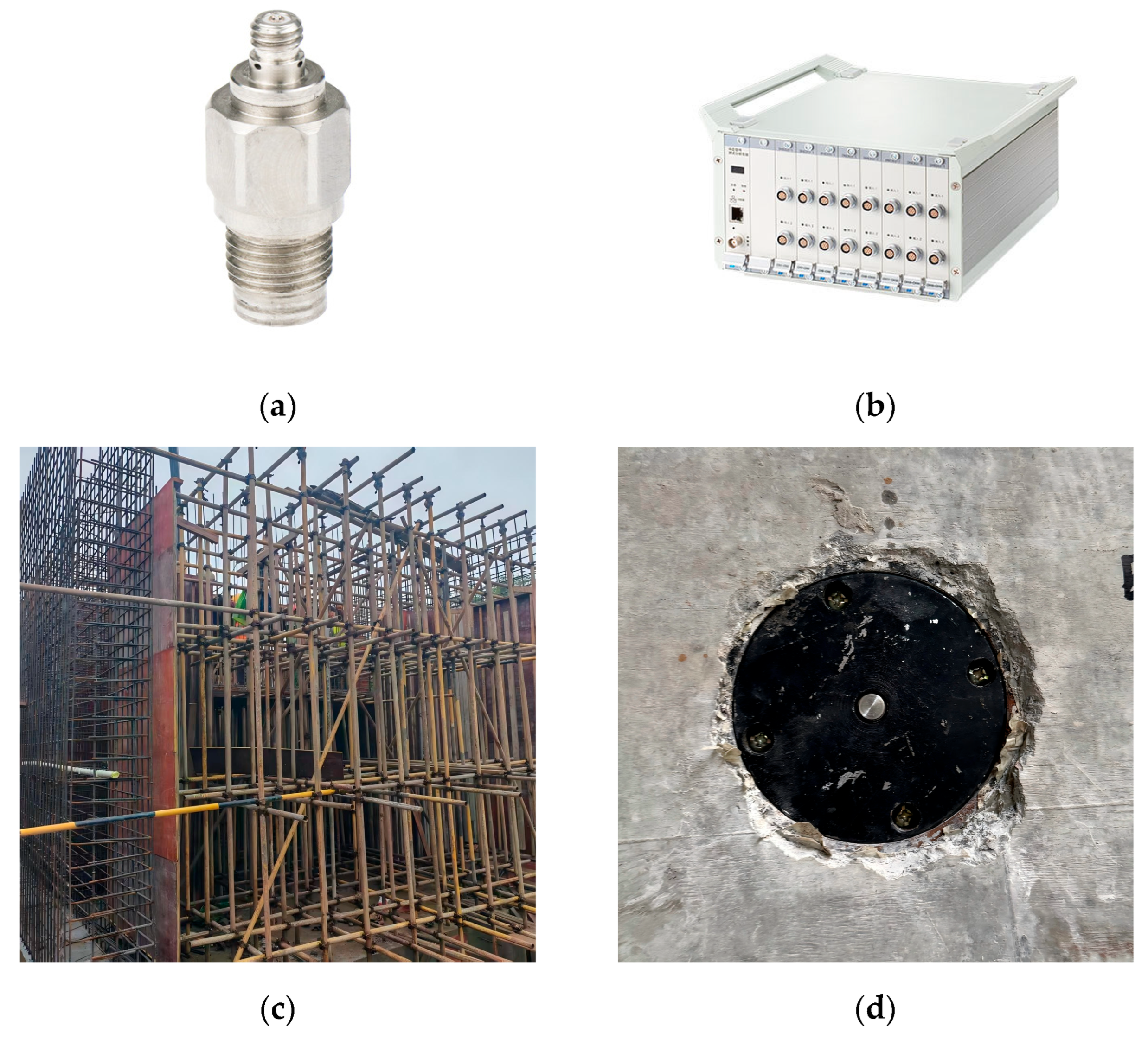

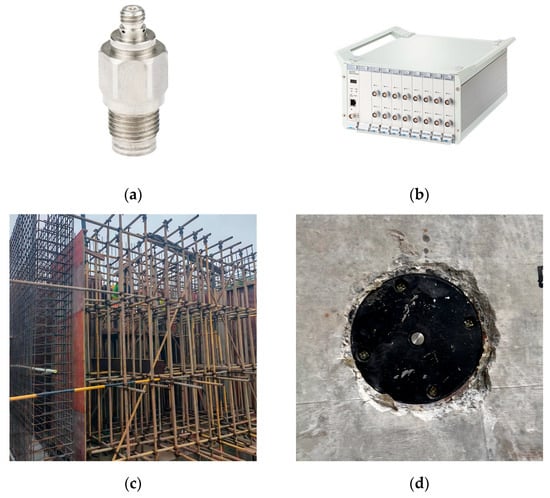

Six blast pressure sensors were installed inside the structure; their locations are shown in Figure 1. Piezoelectric pressure transducers manufactured by Zhejiang Donghua Testing Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) were used. Data were acquired using a DH5960 recorder (Zhejiang Donghua Testing Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) at a sampling frequency of 1 MHz. The sensor faces were flush with the wall surface, and both the sensor bases and the cable conduits were embedded in the concrete. Figure 4a,b show the measuring instruments used, while Figure 4c,d illustrate the construction process of the structure.

Figure 4.

Measurement instruments and construction process. (a) Piezoelectric pressure sensor. (b) Data acquisition system. (c) Construction process of the structure. (d) Sensor installation.

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Reflected Pressure

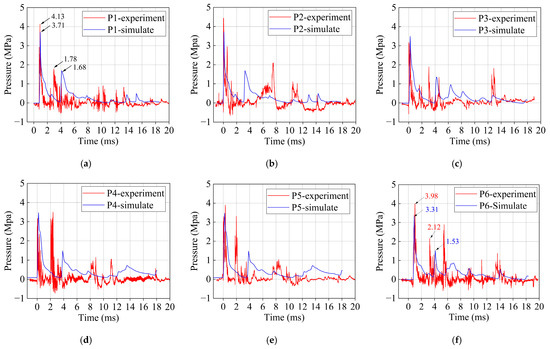

The propagation of blast waves from TNT detonation in confined spaces is highly complex. Compared with free-field blast pressure curves, the pressure histories in confined spaces exhibit multiple peaks and a longer positive-phase duration, indicating that the forces acting on the structure are correspondingly complicated. The measured blast pressures are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Experimental and simulated blast pressure histories. (a) Sensor P1; (b) Sensor P2; (c) Sensor P3; (d) Sensor P4; (e) Sensor P5; (f) Sensor P6.

Most sensors recorded maximum reflected pressure peaks in the range of 3–4 MPa, and multiple peaks were observed at each measurement point. Approximately 5 ms after TNT detonation, the blast wave reached the sensor locations, producing the first peak. Subsequently, reflected waves from adjacent structural components generated a second peak. Around 10 ms after detonation, a third, more pronounced pressure peak appeared, caused by reflections from the structure’s blast-facing surface, with a pressure magnitude of approximately 1 MPa.

3.2. Structural Damage

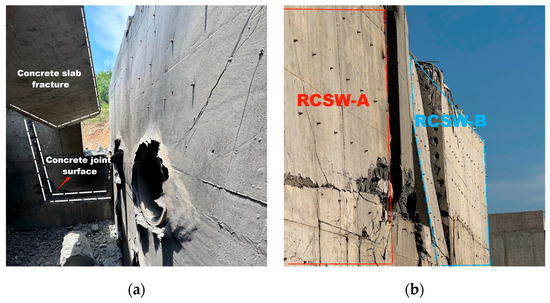

The overall structural failure is shown in Figure 6. It should be noted that RCSW B was cast in two stages to evaluate the blast resistance of an extended structure. As shown in Figure 6a, the concrete along the casting joint of RCSW B—corresponding to the plane of the wall cracks—completely failed, and most of the reinforcement was fractured. The portion of the roof slab near the blast source, at the wall–slab intersection, suffered severe damage; the slab was fully fractured at the edges and remained suspended in the air, held in place only by a few remaining rebars. For safety considerations during post-test cleanup, this portion was dismantled. Consequently, subsequent analyses focus primarily on the RCSW A specimen.

Figure 6.

Overall structural failure. (a) Internal damage. (b) Structural deformation.

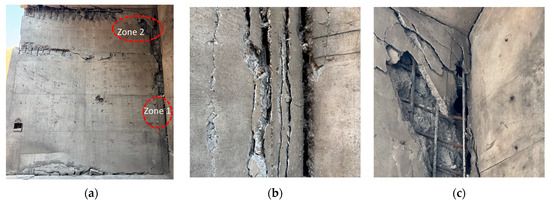

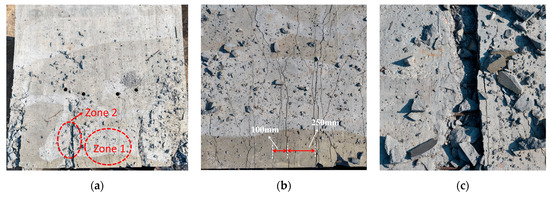

Damage on the blast-facing wall W1 is shown in Figure 7. The damage primarily occurred around the supports. As stress waves propagated from the interior of the wall to the joints, compressive waves and reflected waves superimposed and interfered, producing ring-shaped cracks around the wall. It is noteworthy that the orientation of these cracks is not perfectly perpendicular to the wall thickness. Under near-field blast loading, the blast waves do not act exactly normal to the wall surface, causing the direction of maximum principal stress in the concrete to deviate and form a small acute angle with the wall surface. This stress condition led to the formation of slab-like concrete fragments in Zone 1.

Figure 7.

W1 Frontal Impact Damage. (a) Damage on the blast-facing surface. (b) Zone1. (c) Zone2.

The damage on the rear surface of the wall is presented in Figure 8. On wall W1, a wide primary crack originated from the blast vent on the right and propagated toward the left. During its development, multiple smaller cracks branched off upward and downward from this primary crack. In Zone 1, the concrete exhibited extensive spalling and scabbing; the outer layer of concrete detached from the wall, exposing the reinforcement mesh. The damage pattern on the rear face indicates that the concrete was subjected to tensile stresses perpendicular to the surface, which exceeded the dynamic tensile strength of the material. However, even in the regions with the most severe concrete damage, the reinforcement did not fracture.

Figure 8.

Rear surface damage of W1. (a) Damage on the rear surface. (b) Zone 1. (c) Zone 2.

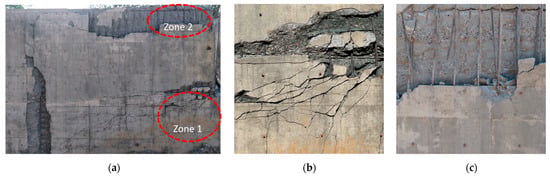

Figure 9 illustrates the damage on the blast-facing surface of slab S1. Similar to the wall, dense ring-shaped cracks developed along the wall–slab boundaries. Compared with those on the wall, these cracks were finer but greater in number. The enlarged view of Zone 2 reveals that wide oblique cracks penetrated through the entire thickness of the joint, indicating that the joint interface was unable to withstand the excessive shear forces transmitted from the slab to the wall.

Figure 9.

S1 Frontal Impact Damage. (a) Damage on the blast-facing surface. (b) Zone 1. (c) Zone 2.

The damage on the rear surface of slab S1 is presented in Figure 10. In Zone 1, fine cracks exhibited a Y-shaped distribution, extending from the center toward the supports with spacing ranging from 100 mm to 250 mm. In contrast to the local shear failure observed at the supports, this crack distribution pattern indicates that slab S1 underwent significant flexural deformation. Based on the failure patterns observed at the plate ends and mid-span regions, it can be determined that the plate sustained combined shear-bending damage.

Figure 10.

S1 Back Explosion Surface Damage. (a) Damage on the blast-facing surface. (b) Zone 1. (c) Zone 2.

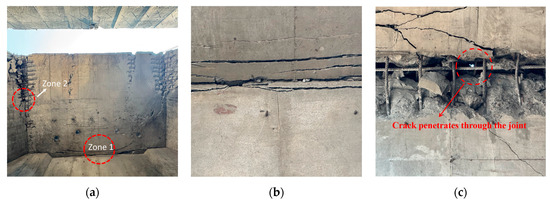

Figure 11 illustrates the failure mode of wall–slab joint J1. Most of the concrete near Zone 1 was fragmented, and the reinforcement was twisted but did not break, preventing the collapse of broken concrete in the core of the joint. Damage severity increased closer to the blast source, with the fractured zone extending to roughly half the slab width.

Figure 11.

Failure of the wall–slab joint J1. (a) Damage on the blast-facing surface. (b) Zone 1. (c) Zone 2.

Along the slab thickness, two oblique cracks originated from the edges of the chamfer at the wall–slab joint: the upper crack extended approximately 1330 mm, and the lower crack approximately 970 mm, both fully penetrating the cross-section of the component. It should be noted that the final shape of the oblique rebars was bent rather than tensile. This bending occurred because, after the roof slab reached its maximum upward displacement, the rebars were compressed and deformed under the combined action of rebar recovery force and gravity during the slab rebound.

4. Numerical Simulation

4.1. Model Setup

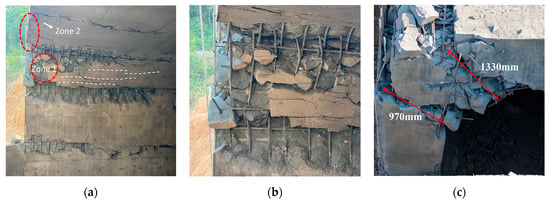

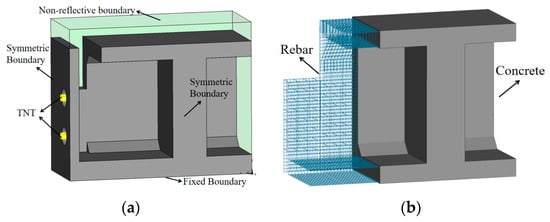

The dynamic explicit analysis software LS-DYNA (version 2024 R1) was used to further investigate the structural damage process and failure mechanisms. An ALE (Arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian) formulation was employed for the numerical simulation [29,30]. Due to the structural and loading symmetry in both longitudinal and transverse directions, a one-quarter model was used to improve computational efficiency [31].

Since the structure is built on a solid foundation, fixed constraints are set at the bottom of the concrete model. To prevent shock waves from reflecting at the boundaries of the air domain, non-reflecting boundary conditions were applied to the top and side surfaces of the air model using the keyword *BOUNDARY_NON_REFLECTING. This boundary condition functions by applying normal and shear stresses at the boundaries to absorb incident waves, thereby allowing shock waves to propagate outward to simulate an infinite air medium.

The interaction between the ALE domain and the Lagrangian domain was established using a fluid–structure interaction (FSI) algorithm, defined by the keyword *CONSTRAINED_LAGRANGE_IN_SOLID. When the fluid comes into contact with the solid, the algorithm automatically generates coupling forces at the interface. These forces serve to transfer the blast pressure to the wall while simultaneously preventing air penetration through the structure. Figure 12 shows the finite element setup for a one-half structural model.

Figure 12.

Finite element model setup. (a) Model boundary conditions. (b) Reinforcement and concrete.

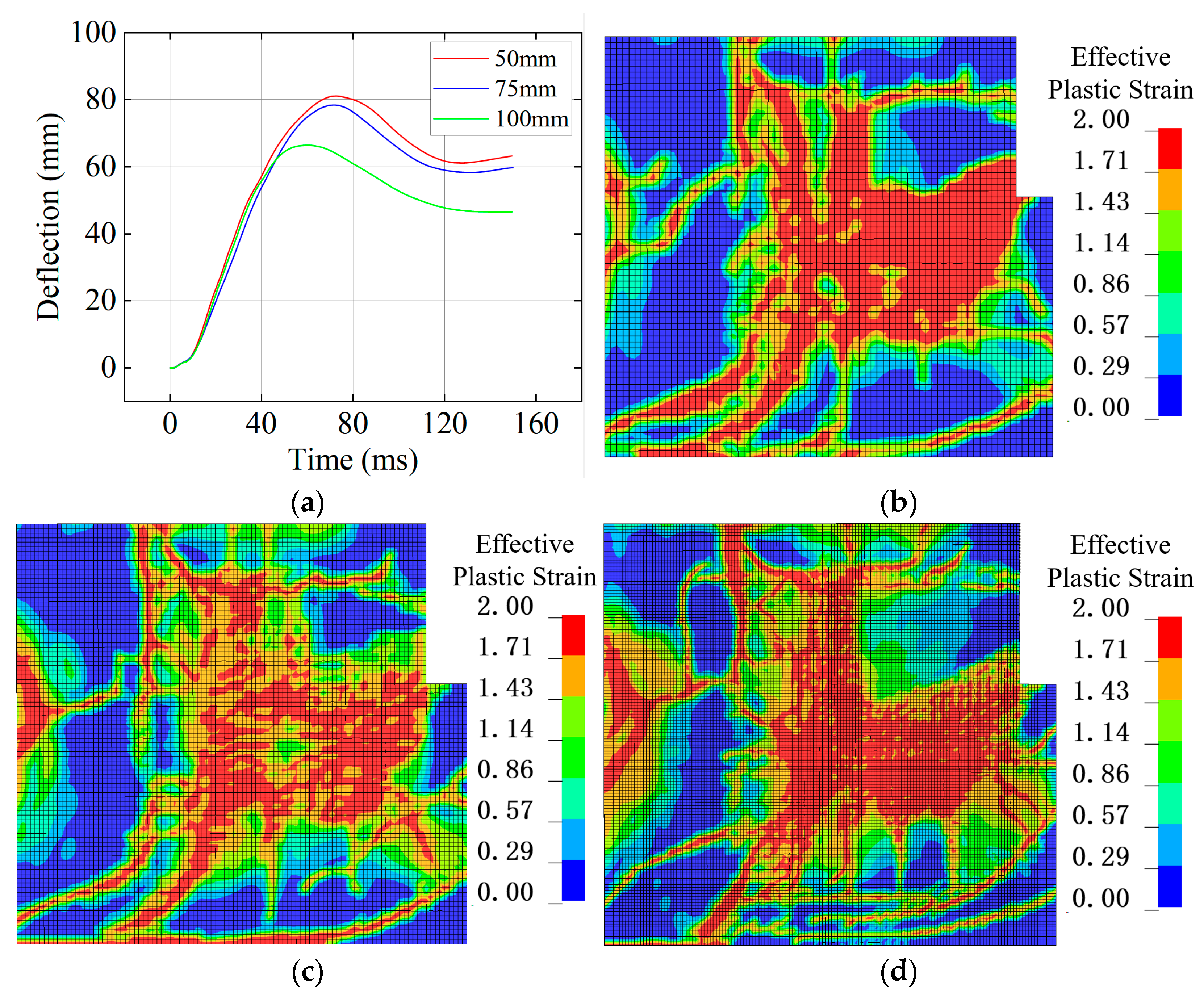

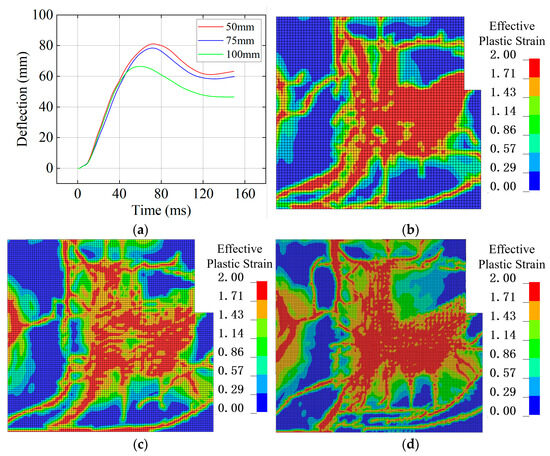

Concrete and Cylindrical Steel Tube were modeled using Lagrangian elements, while TNT and air were discretized using ALE-structured meshes. Reinforcement was defined with beam elements. Although smaller concrete elements generally provide a clearer representation of crack propagation [32,33], for a full-scale model, very fine meshes would require excessive computational resources. Therefore, mesh sensitivity analyses were conducted with concrete element sizes of 50 mm, 75 mm, and 100 mm. The mid-span deflection of the free end of slab S1 and the damage on the blast-facing wall W1 were used as comparison metrics, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Mesh sensitivity analysis. (a) Deflection curves. (b) 100 mm mesh. (c) 75 mm mesh. (d) 50 mm mesh.

When the element size was 100 mm, both the peak and residual mid-span deflections were underestimated due to excessive numerical energy dissipation caused by the coarse mesh. For element sizes of 50 mm and 75 mm, the differences in peak and residual deflections were relatively small. As the mesh was refined, the damage on W1 became clearer, capturing narrower cracks more accurately. Considering both accuracy and computational efficiency, a mesh size of 50 mm was chosen for concrete, reinforcement, and air, resulting in approximately 1.13 million, 98,000, and 3.1 million elements, respectively.

4.2. Material Model

4.2.1. Concrete Properties

Under explosive loading, concrete exhibits complex nonlinear mechanical behavior. The Karagozian & Case (K&C) [34] model uses a nonlinear yield surface based on hydrostatic pressure and deviatoric stress invariants. This yield surface is smooth and continuous in stress space, allowing for an accurate representation of concrete strength under various stress triaxialities, particularly capturing shear and other combined damage mechanisms. The model also incorporates built-in strain rate effects, automatically adjusting material yield strength and damage evolution via a strain rate factor [35,36].

In LS-DYNA [37], the K&C concrete model is defined using the keyword *MAT_CONCRETE_DAMAGE_REL3. Three failure surfaces are used to define the plastic behavior of concrete: the initial yield surface, the ultimate strength surface, and the residual strength surface, expressed as follows:

The failure surfaces of concrete under different stress states are obtained by linear interpolation, expressed as:

where is the damage variable, which is a function of the equivalent plastic strain, and represents the critical damage state, characterizing the hardening and softening stages of concrete.

Since the K&C model does not include an equation of state, it is defined via *EOS_TABULATED_COMPACTION. In LS-DYNA, most parameters can be directly generated based on the unconfined compressive strength [38]. The parameters required for the K&C model are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Material Parameters for the K&C Model.

4.2.2. Reinforcement Properties

The reinforcement is defined using the *MAT_PLASTIC_KINEMATIC keyword, which accounts for strain rate effects via the Cowper–Symonds model. Here, σy represents the dynamic yield stress, is the strain rate, C and P are the Cowper–Symonds parameters, and σ0 is the yield stress [39]. The material properties of the steel are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cowper–Symonds Material Parameters for Steel.

4.2.3. Air and TNT Properties

The air properties were defined using the keywords *MAT_NULL and *EOS_LINEAR_POLYNOMIAL. The linear polynomial equation of state expresses pressure as a polynomial linear combination of density compression and internal energy [40], given by:

where are user-defined constants, , is the current density, is the reference density, and is the initial specific internal energy. The parameter values are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Air Properties.

TNT material is defined using the keywords *MAT_HIGH_EXPLOSIVE_BURN and *EOS_JWL. The equation of state is expressed as:

where is the pressure, is the specific internal energy per unit initial volume, is the relative volume. The equation consists of three terms, which control the high-pressure, medium-pressure, and low-pressure portions of the curve, respectively [41]. Specific material parameters are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

TNT Properties.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Shock Wave Propagation Characteristics

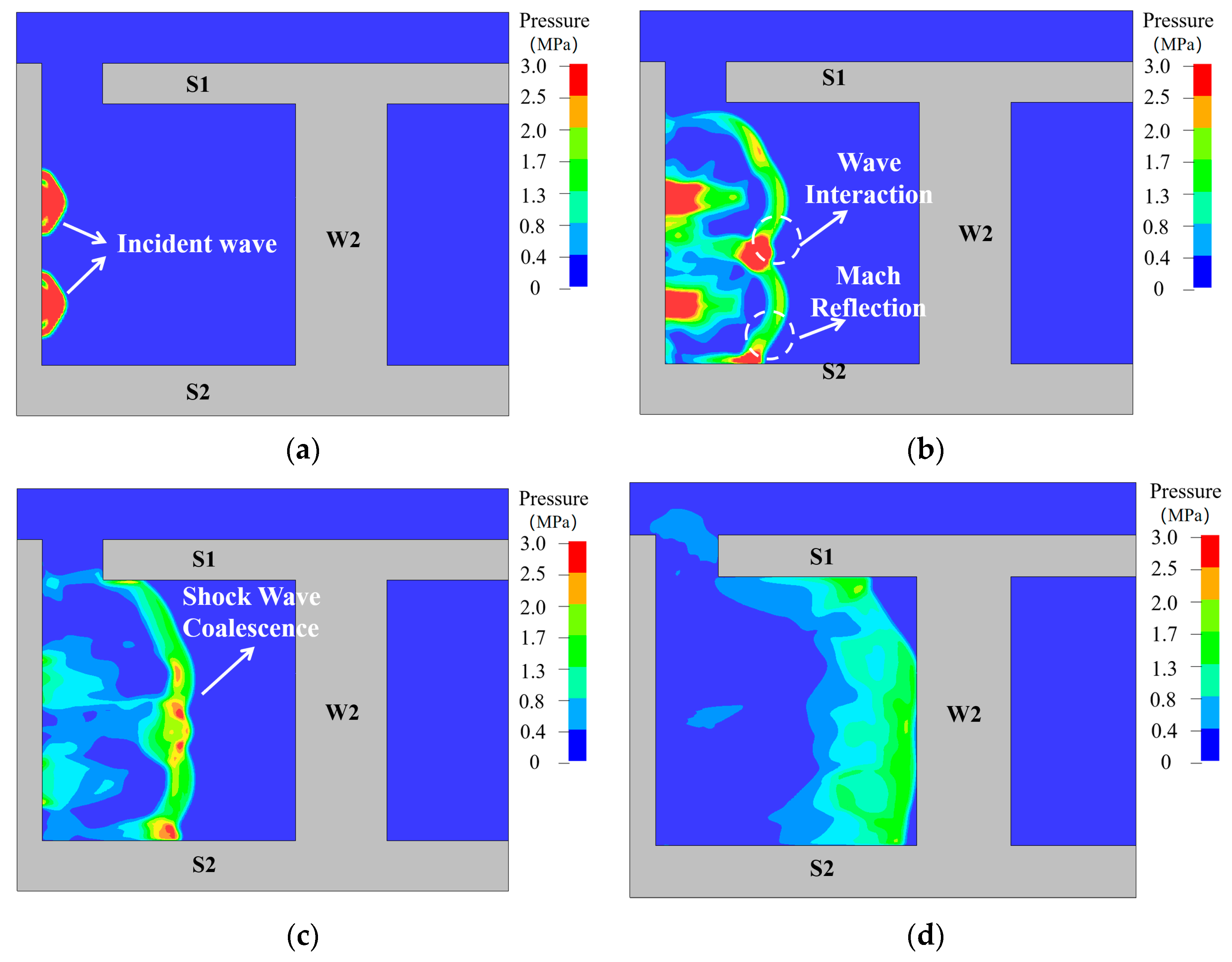

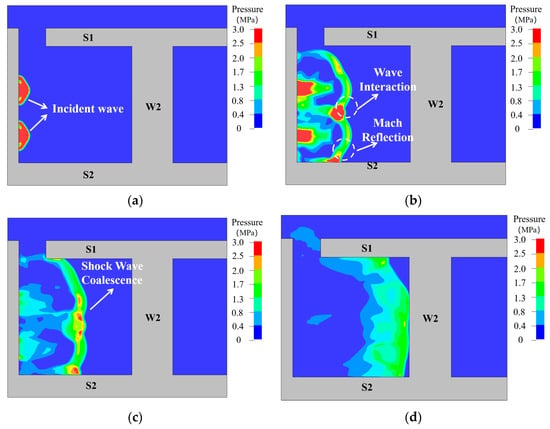

When TNT detonates in a closed or semi-closed space, the blast wave propagating forward undergoes reflection, interference, and other phenomena between different structural walls. When the spatial volume is small, the expansion of detonation products is constrained, and energy cannot be released in time, resulting in internal pressures on the structure that are far higher than those in free-field explosions. Figure 14 illustrates the propagation process of blast waves inside the structure.

Figure 14.

Propagation process of shock waves inside the structure. (a) 0.02 ms; (b) 0.8 ms; (c) 1.5 ms; (d) 2.5 ms; (e) 3.5 ms; (f) 5 ms; (g) 7 ms; (h) 10 ms.

At approximately 0.02 ms, the blast wave emerges from the source wall, forming an incident wave with extremely high pressure, which decays exponentially as it propagates forward. Around 0.8 ms, interference occurs between the upper and lower blasts, creating another high-pressure zone at the interference location. Meanwhile, the blast wave reflects off slab S2, and the reflected wave intersects with the incident wave, forming a Mach wave. At about 1.5 ms, the blast wave acts on slab S1, causing immediate reflection on the slab.

By 2.5 ms, the wave reaches wall W2. Around 3.5 ms, the blast wave undergoes vertical reflection at W2, with reflected pressures several times higher than the incident pressure. At the top and bottom of the wall, reflections from the wall interfere with incident waves from the ceiling and floor, resulting in pressures significantly higher than in other regions. From 7.5 ms to 10 ms, the blast wave reaches the source wall again, producing secondary reflections. This cycle continues repeatedly until the blast wave energy is fully dissipated.

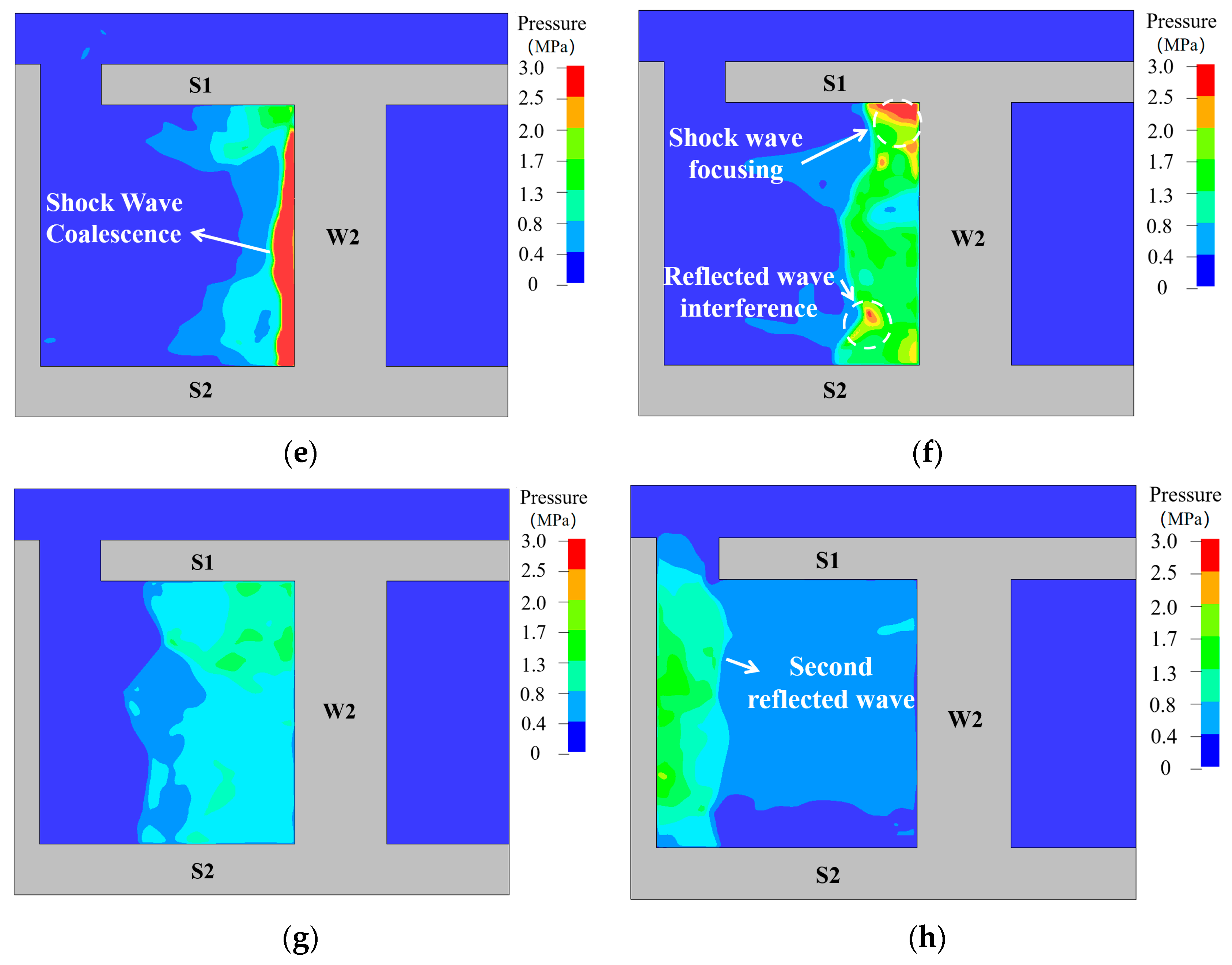

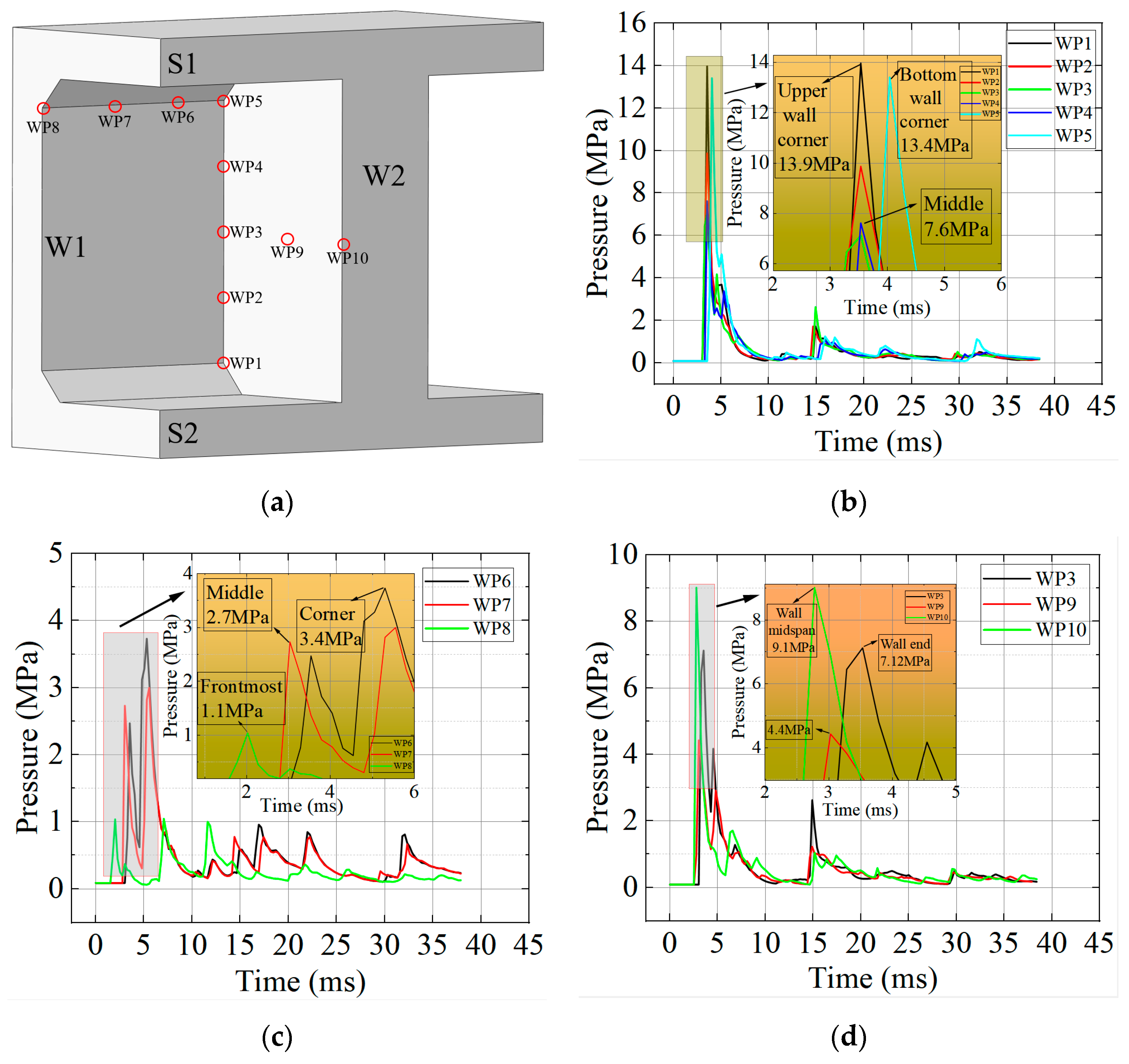

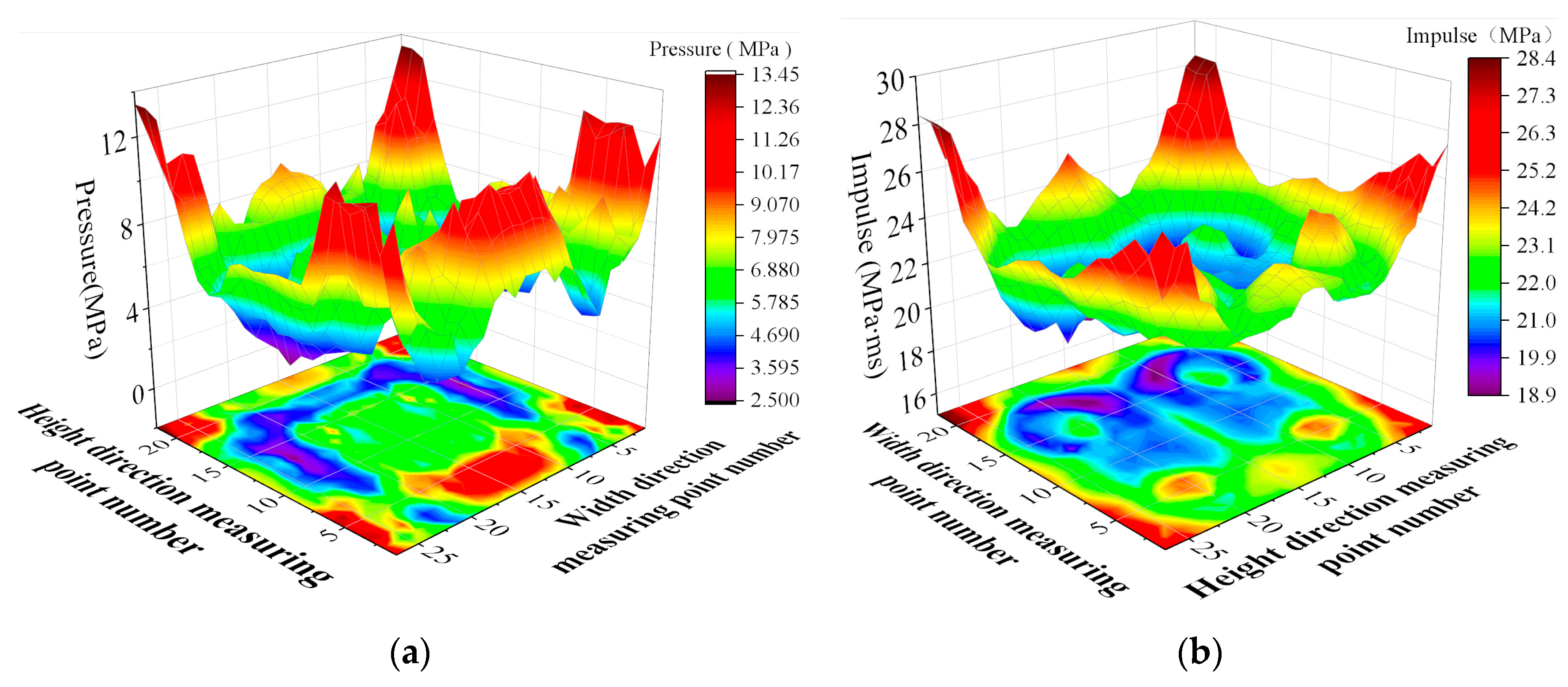

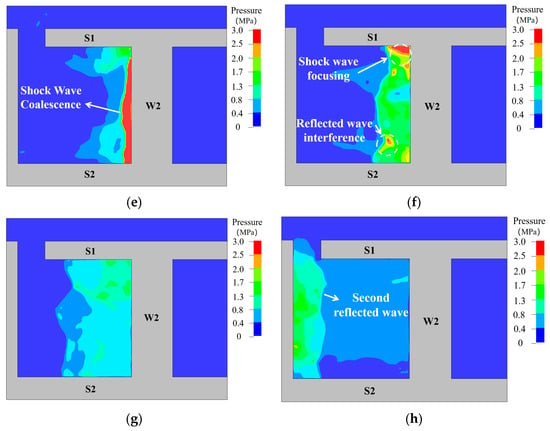

To investigate the variation in reflected pressure at different locations, ten measurement points were selected inside the structure. Figure 15 shows the time–pressure curves at these points. At the nodes of W1 and W2, the pressure along the height exhibited a non-uniform distribution: the pressures at the top and bottom corners of the wall (WP5 and WP1) were the highest, measuring 13.9 MPa and 13.4 MPa, respectively, while the pressures at the mid-wall measurement points ranged between 7 MPa and 10 MPa. This is mainly because the wall corners are subjected to reflected pressures from three intersecting members, whereas the mid-wall points experience only two reflected pressures.

Figure 15.

Internal Reflected Pressure. (a) Schematic diagram of measurement points. (b) Pressure distribution at the supports. (c) Pressure distribution at the joints. (d) Pressure distribution on the blast-facing surface.

Comparing the reflected pressures at WP3, WP9, and WP10, which were 7.1 MPa, 4.4 MPa, and 9.1 MPa, respectively, it can be seen that the reflected pressure at the center of W2 was the highest. Moving away from the center, the pressure decreases but rises again near the supports. This is because at WP10, the incident wave was nearly perpendicular, producing the highest reflected pressure. At WP9, the incident angle increased, reducing the reflection coefficient and lowering the reflected pressure by 51.6% relative to WP10. At WP3, overlapping of different reflected waves caused the pressure to increase by 61.8% compared to WP9. Notably, although WP10 was closest to the center of the shock wave front, its maximum reflected pressure was still 34.5% and 32.1% lower than those at WP1 and WP5, respectively.

At the J1 node, located at the intersection of S1 and W1, the reflected pressure increases rather than decreases as the explosive wave propagates farther. This is partly because the incident angle of the wave continuously increases during propagation, forming a Mach wave at the node, and partly because reflected waves from W1 and S1 converge at the node. The combined effect of these two phenomena raises the pressure above the decay of the original wave.

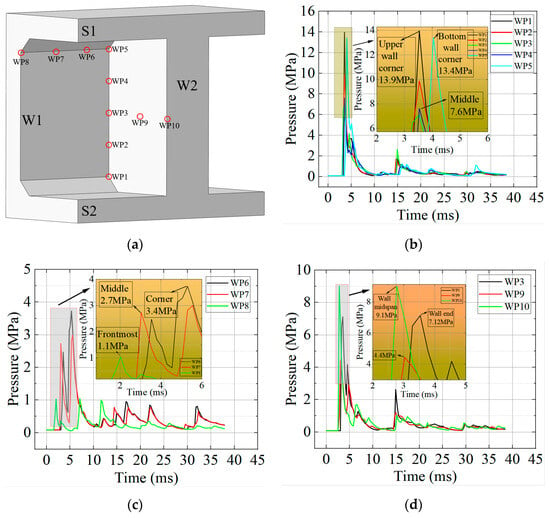

Reflected pressure measurement points were uniformly selected on the surface of the W2 wall in the semi-structured model to reveal the distribution pattern of the explosion pressure across the wall. The horizontal and vertical spacing between adjacent points was 20 cm, resulting in a total of 308 measurement points. Figure 16 shows the maximum reflected pressure across the wall and the impulse distribution at 100 ms. It can be seen that the maximum peak pressure does not occur at the wall center but rather at the bottom and four corners. The impulse exhibits a similar distribution pattern, with the largest values at the edges of the wall and the highest values at the endpoints of each edge. This distribution explains why, in both experiments and numerical simulations, the damage at the wall supports is significantly greater than at other locations.

Figure 16.

Maximum reflected pressure and impulse distribution on W2. (a) Distribution of blast pressure. (b) Distribution of Impulse.

5.2. Analysis of Structural Damage Mechanisms

Energy Transfer Mechanism

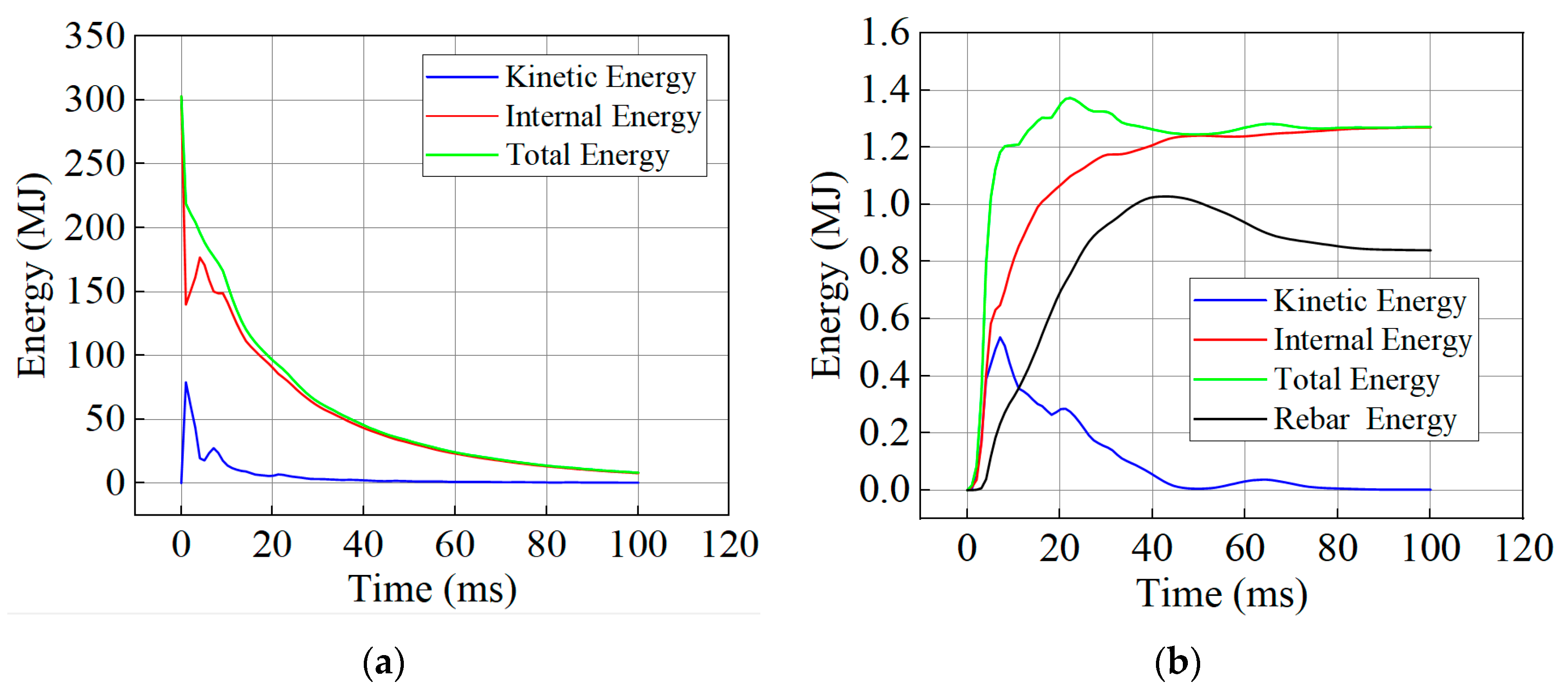

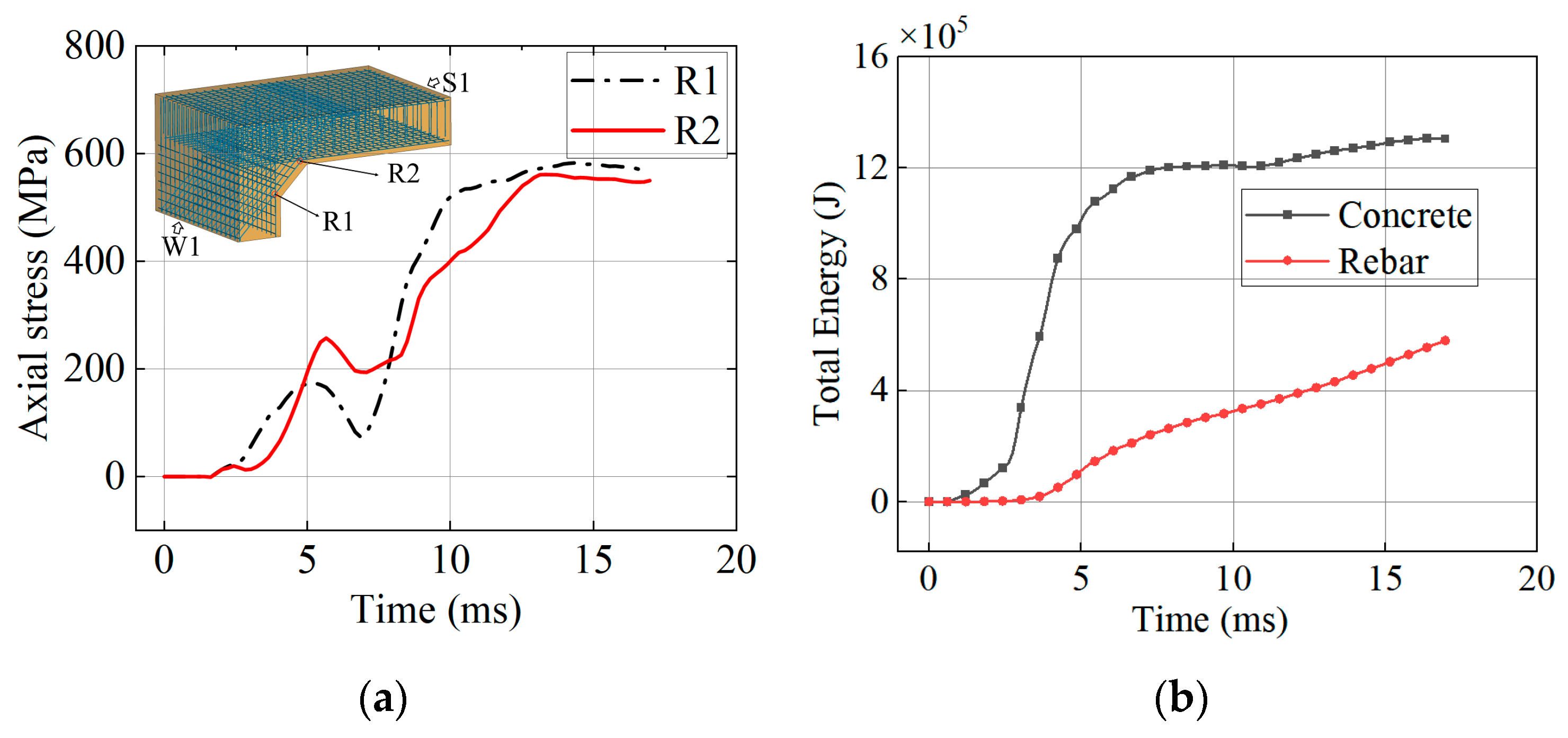

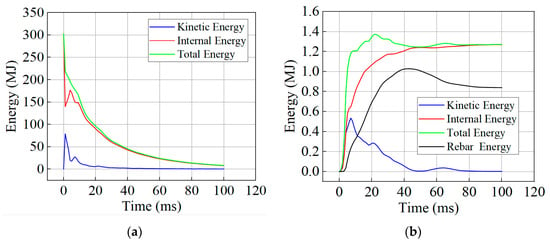

Figure 17 illustrates the energy evolution process of the air, concrete, and reinforcement. Upon the detonation of the TNT, chemical energy is instantaneously converted into the internal and kinetic energy of the air, followed by an exponential decay. When the incident shock wave impinges on the concrete wall, the significant acoustic impedance mismatch between the air and the concrete generates a reflected overpressure. This pressure pulse performs mechanical work on the structural surface, facilitating the rapid transfer of the shock wave’s kinetic energy to the structure. Within a few milliseconds, the total energy of the concrete and reinforcement rises sharply. However, the energy absorption of the reinforcement exhibits a distinct time lag relative to the concrete. This phenomenon is attributed to the fact that the concrete initially dissipates energy through local shear failure, whereas the reinforcement requires the structure to undergo sufficient deformation before it can significantly participate in energy absorption.

Figure 17.

Energy-time history curves. (a) Energy evolution of the air domain. (b) Energy evolution of concrete and reinforcement.

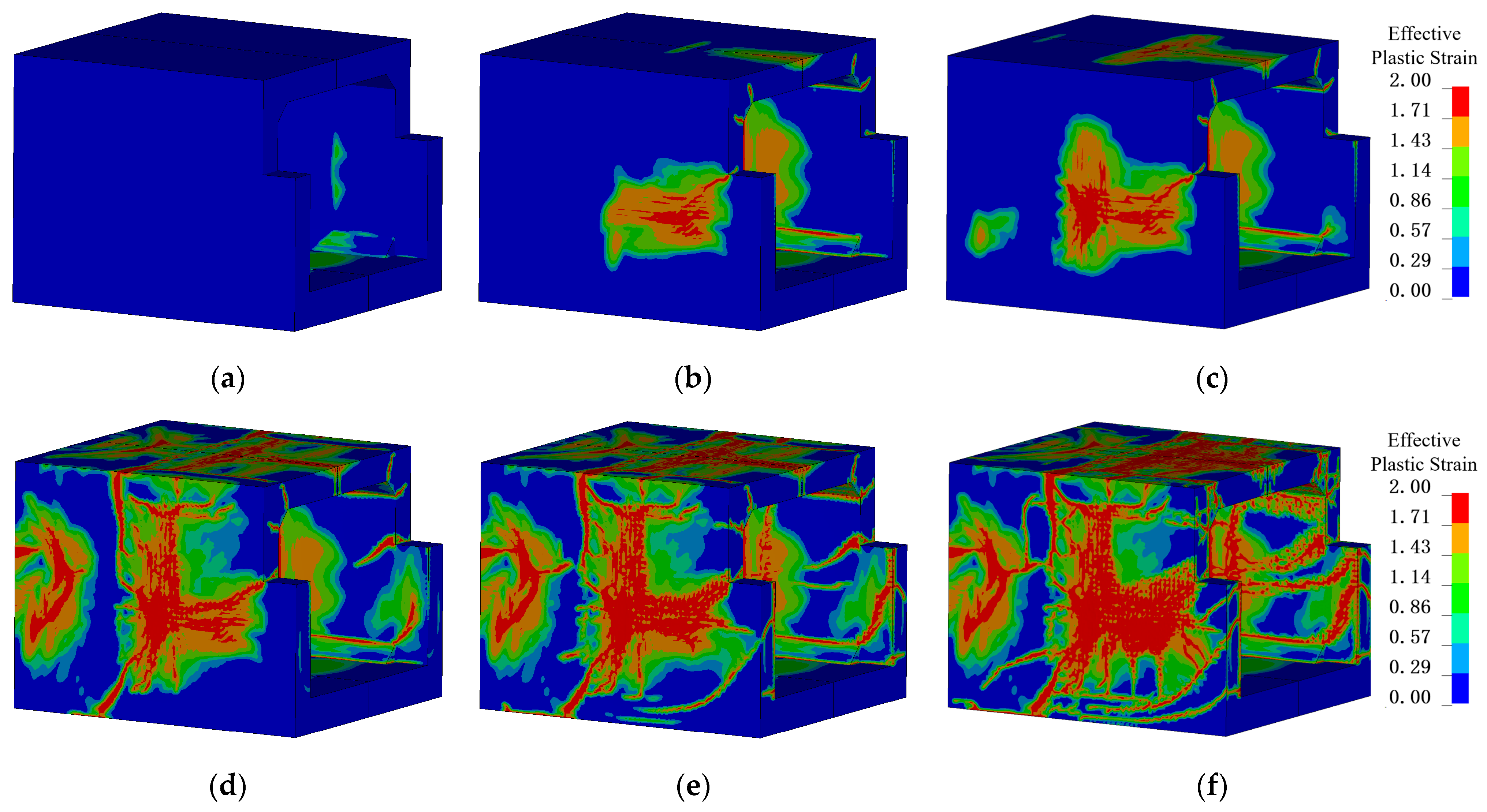

Figure 18 illustrates the damage evolution process of RCSW-A. Approximately 2 ms after the TNT detonation, the blast wave impacted the side walls of the structure. Around 4 ms, stress waves propagated to the outer surface, generating tensile waves that caused tensile damage in the concrete at the center of the rear surface of wall W1, with the damaged area developing obliquely. Simultaneously, shear cracks appeared at the wall–slab joint locations.

Figure 18.

Damage evolution process of RCSW-A under internal blast loading. (a) 2 ms; (b) 4 ms; (c) 5 ms; (d) 7 ms; (e) 10 ms; (f) 100 ms.

By 5 ms, the cracks on the rear surface of W1 rapidly extended upward to the edges of the component, while the damage zone in the concrete expanded outward from the component center. At 7 ms, vertical cracks at the left end reached the intersection of W1 and the lower surface of S1, forming horizontal cracks. Prior to 7 ms, the components primarily experienced shear damage. By 10 ms, the crack distribution at the supports had stabilized, whereas the damage in the central concrete of the walls continued to expand. By approximately 100 ms, the overall structural damage had essentially reached its final extent.

Under internal blast loading, when the explosion wave first impacts the structural surface, a compressive wave is initially generated on the component surface and propagates toward the back face. Because concrete has high compressive strength and is subjected to significant confinement effects, it is difficult for the compressive wave alone to damage the concrete. In contrast, the acoustic impedance of air is much lower than that of concrete; when the compressive wave reaches the back face of the component, it reflects as a tensile wave with nearly the same magnitude as the incident compressive wave, causing tensile damage in the concrete. Figure 8b,c illustrate this phenomenon, where the tensile failure surface of the concrete is largely parallel to the surface of the member.

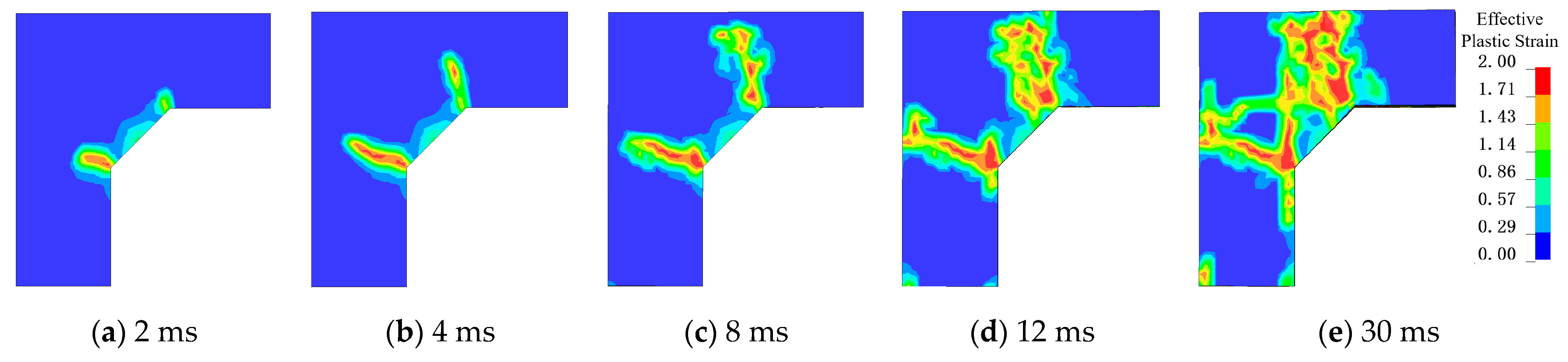

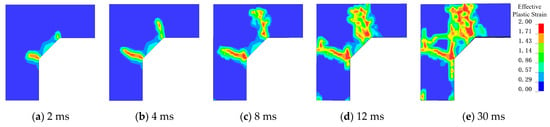

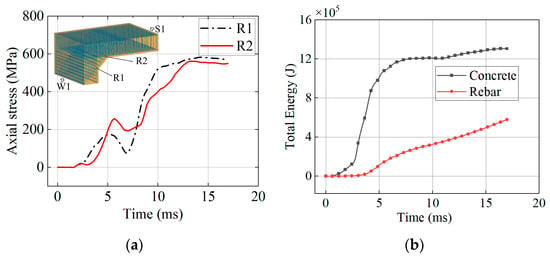

Figure 19 illustrates the damage progression of joint J1. At 2 ms, shear damage appeared in the concrete at the bottom of the joint—where the wall and slab cross-sections change. By 4 ms, these bottom cracks evolved into macroscopic oblique cracks and continued propagating upward. The shear cracks formed in less than 2 ms, primarily due to stress wave reflection and superposition at the joint. The elastic modulus of concrete is significantly lower than that of steel reinforcement, so the stress borne by the steel at this stage is relatively small. As shown in Figure 20a, prior to 4 ms, the reinforcing steel has not yet yielded and remains in the elastic stage. Figure 20b also shows that during the initial blast phase, the total energy absorbed by the steel was far lower than that absorbed by the concrete.

Figure 19.

Damage evolution process of joint J1. (a) 2 ms; (b) 4 ms; (c) 8 ms; (d) 12 ms; (e) 30 ms.

Figure 20.

Reinforcement behavior during the local response phase. (a) Stress in J1 reinforcement. (b) Total energy absorbed by concrete and reinforcement.

After 4 ms, tensile effects induced by outward deformation of the components widened the shear cracks, and the reinforcement began to carry tensile forces. As structural displacements developed, negative bending moments appeared in adjacent members at the joint, accelerating joint failure. Between 8 ms and 12 ms, the concrete in the sloped bottom region of the joint failed as it exceeded its maximum tensile strength. This phenomenon is visible in Figure 11a, where horizontal cracks are uniformly distributed across the sloped surface, perpendicular to the inclined reinforcement. By 30 ms, the joint was completely surrounded by failure surfaces, forming a plastic hinge; thereafter, the joint relied entirely on the reinforcement to maintain structural integrity.

Stress waves generated within a component not only reflect at the back-explosion surface but also propagate and superimpose at the node region. Stress waves originating from adjacent components cause shear stress to rise rapidly. Due to the characteristics of internal blast loading, the components are subjected to multiple peak reflected pressures and long-duration positive pressure, which produces a relatively uniform surface load over the member. As a result, the component experiences extremely high acceleration. Because the component does not have sufficient time to deform, large constraint reactions develop at the supports, leading to pronounced stress concentrations. Coupled with stress wave reflections at the joints, the edge concrete rapidly reaches its maximum tensile strength, initiating cracks that propagate obliquely inward. This phenomenon occurs in both experimental tests and numerical simulations, with nearly all joints exhibiting shear cracks. Although this type of damage develops more slowly than the direct stress-wave-induced damage, it is still classified as local damage.

As the blast wave dissipates and energy is released, the local response of the structure diminishes while the overall response intensifies. Members begin to undergo bending deformation, generating negative bending moments at the supports. However, shear cracks have already formed in the concrete at the support cross-sections prior to this stage. Consequently, under the influence of negative bending moments, these cracks at the supports rapidly propagate. When the bearing is severely weakened and loses its capacity to resist bending moments, only the reinforcing steel provides tensile force to prevent outward movement of the member. Therefore, although the reinforcing steel has limited effectiveness in restraining shear cracks generated during the early stages of the explosion, it plays a crucial role in preventing structural disintegration and ensuring overall integrity during the later stages.

Overall, the failure of structural members under internal explosion loads can be divided into three stages:

Stage 1—Early Explosion Phase: Upon the initial contact of the explosion wave with the structural surfaces, stress waves rapidly propagate through the members, reflecting at the opposite surfaces as tensile waves that induce concrete layer splitting. When the stress waves reach the supports, extremely high shear stresses develop, causing the formation of shear cracks. Damage at this stage primarily affects the concrete because the overall structural deformation is minimal, and the reinforcement provides limited resistance; the response is dominated by local effects.

Stage 2—Coupled Shear-Bending Response: If the nodes possess sufficient strength, and the shear cracks from the early phase do not penetrate the full section, the member can develop adequate end constraints and enter a combined shear-bending response. The panels and walls move outward under the explosion pressure, bending cracks form near mid-span, and rotations at the supports generate negative bending moments, which further accelerate the propagation of early shear cracks. However, if the node strength is insufficient, the initial shear cracks quickly penetrate the section as bending begins, resulting in limited member deformation and a brittle failure characteristic.

Stage 3—Late Bending Phase: During the later bending response, the explosive load has dissipated, and the structure is mainly influenced by inertia. If the member’s kinetic energy is low at this stage, the deformation stabilizes, with cracks at the supports potentially becoming through-cracks. If the reinforcement is intact and sufficiently strong, the member exhibits clear peak and residual displacements. Conversely, if significant kinetic energy remains and the supports fail completely, the reinforcement bears all tensile forces; if the reinforcement strength is insufficient, the member may detach entirely, leading to structural collapse.

5.3. Comparison Between Experimental and Numerical Results

Table 6 presents the error analysis between the experimental and numerical blast pressures. The maximum peak pressure errors at all measurement points were within ±20%, which is acceptable given the extreme blast environment. Figure 5 compares the time–pressure histories from the experiments and numerical simulations.

Table 6.

Errors between experimental and simulated blast pressures.

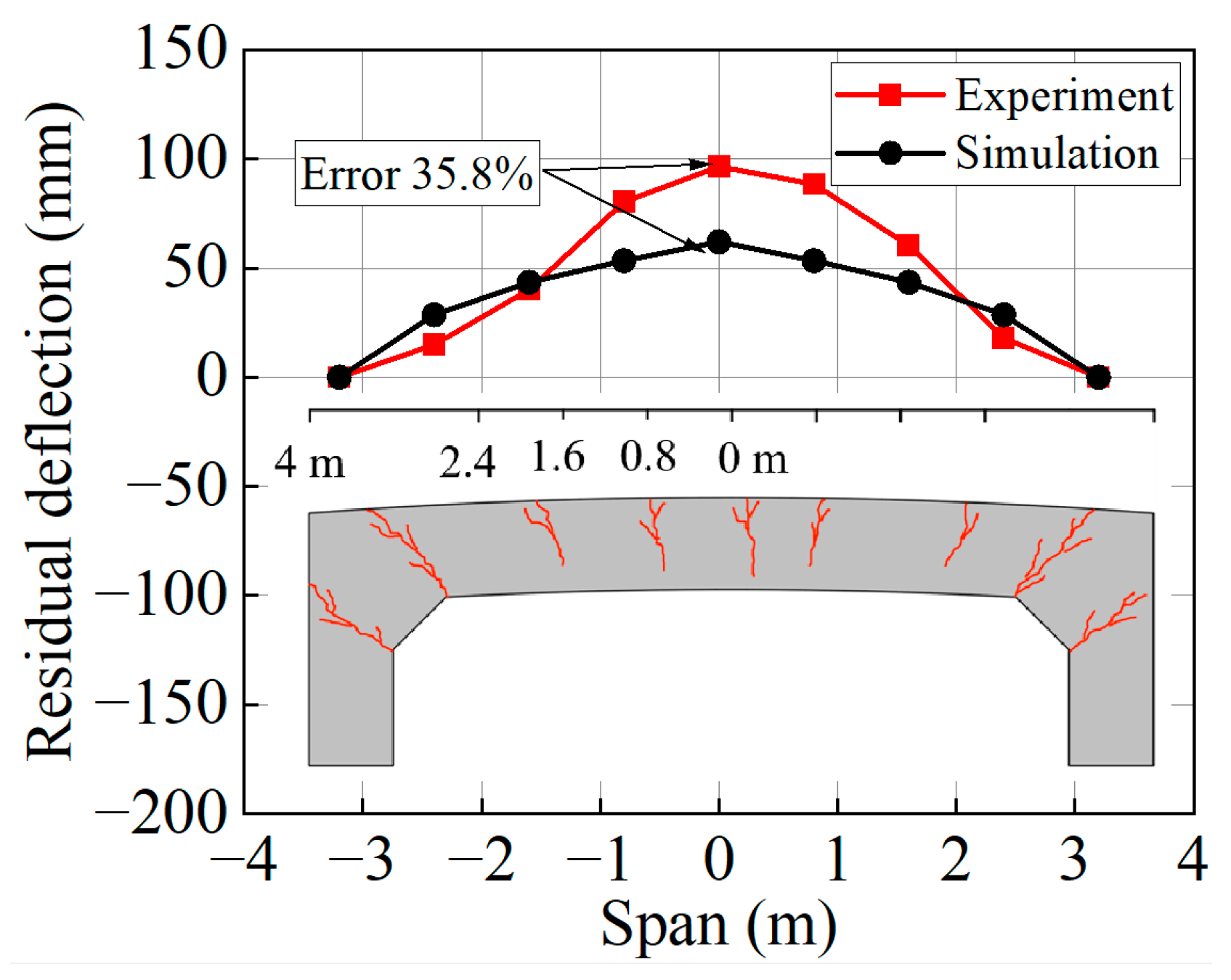

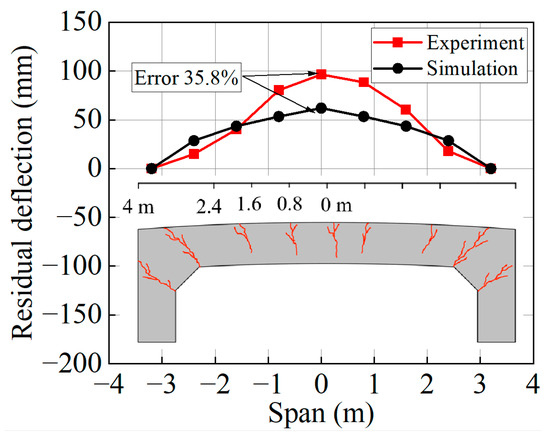

Due to the large structure size, it was difficult to install displacement sensors, and thus, displacement response data during the blast were not obtained. After the test, a laser distance meter was used to measure the residual deflections of the components. Figure 21 shows the comparison between experimental and numerical residual deflections at the free end of slab S1.

Figure 21.

Comparison of residual deflections between experimental measurements and numerical simulations.

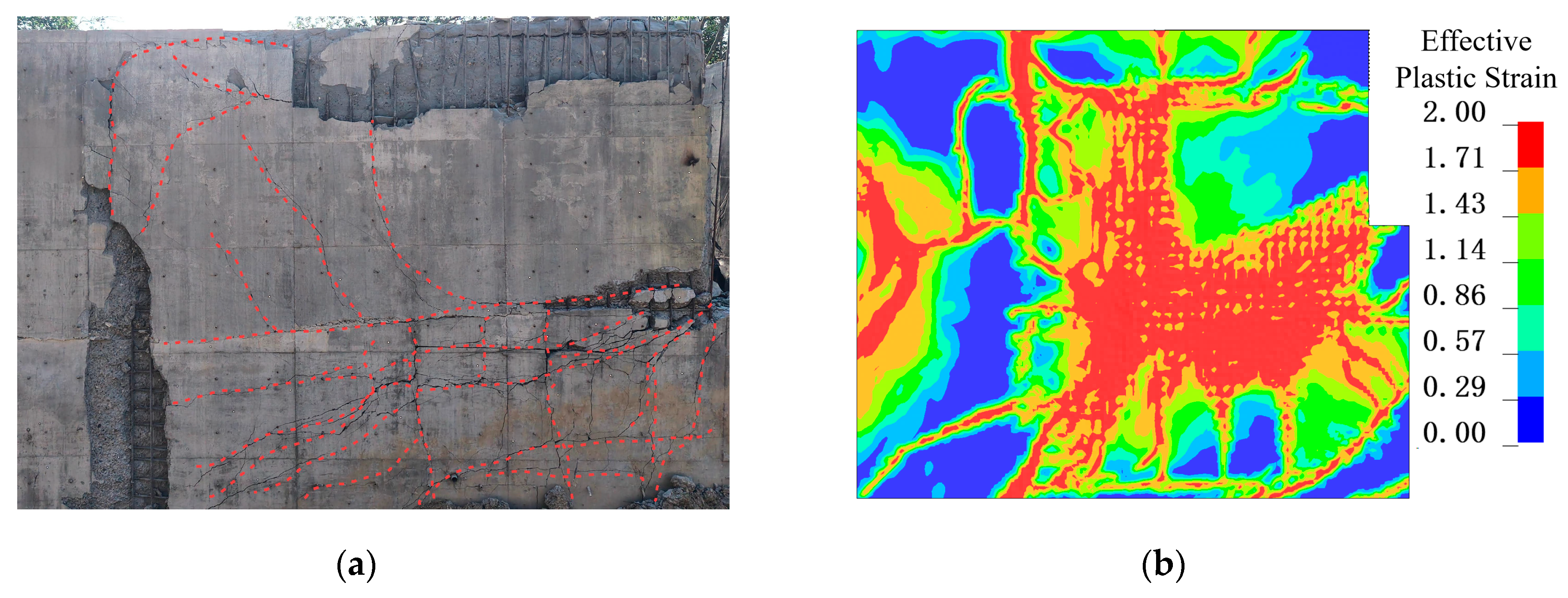

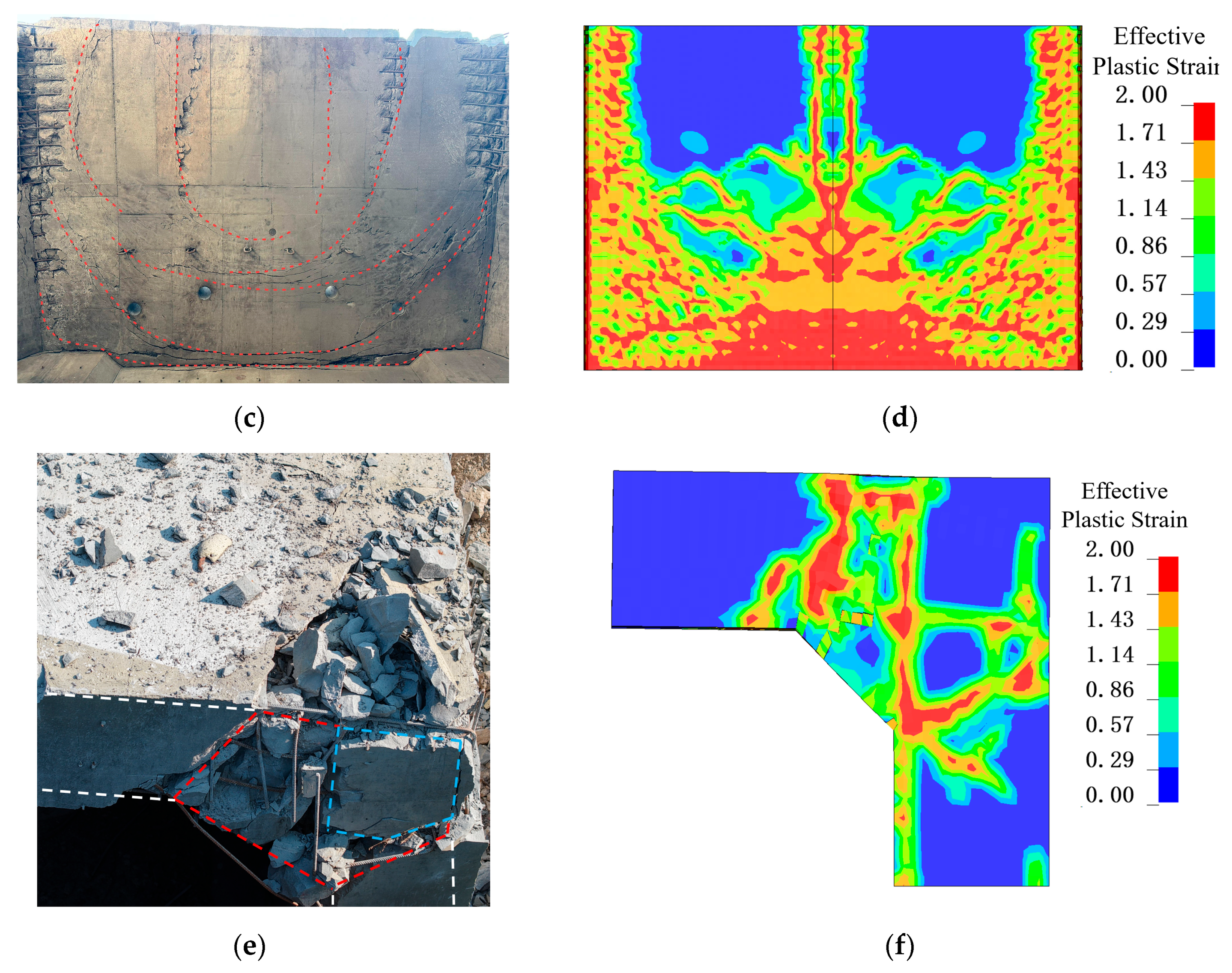

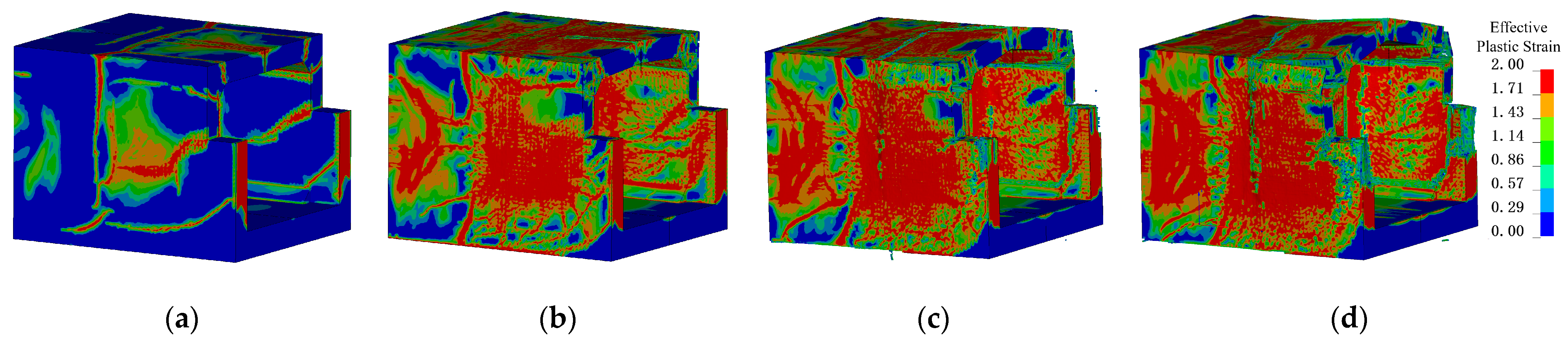

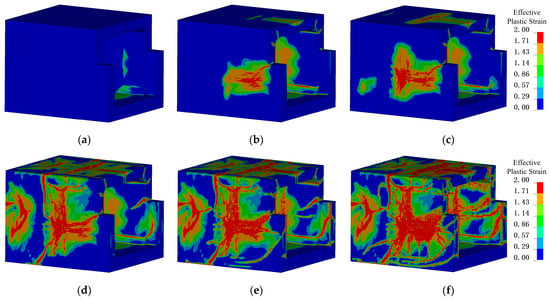

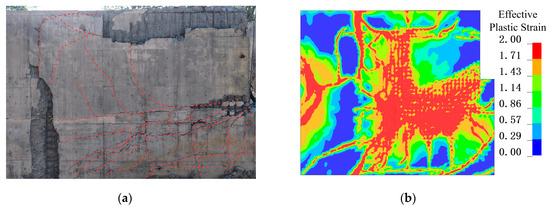

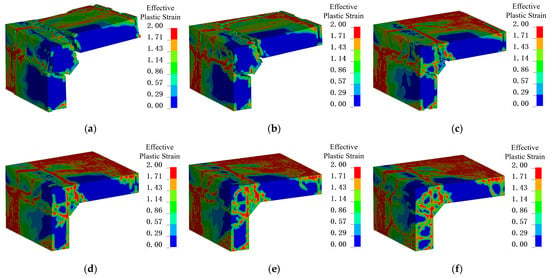

In the experiment, apart from a few wider cracks, most of the fine cracks in the components had widths between 2 mm and 10 mm, much smaller than the concrete mesh size. Therefore, concrete damage was represented using equivalent plastic strain. Figure 22 shows the comparison between experimental observations and numerical simulation results.

Figure 22.

Comparison between experimental and numerical results. (a) W1 experimental damage; (b) W1 simulated damage; (c) S1 experimental damage; (d) S1 simulated damage; (e) J1 experimental damage; (f) J1 simulated damage.

The numerical simulation of wall and slab damage achieved satisfactory accuracy compared with the experimental results. The extent and pattern of cracks on both the blast-facing and rear surfaces of W1 closely matched the observations from the tests. On the blast-facing surface (S1), circular cracks formed around the supported region of the slab, and this phenomenon was also captured in the simulation. For joint J2, as observed experimentally, two primary oblique cracks at the bottom of the joint penetrated the entire cross-section. These results indicate that the numerical approach employed in this study can accurately capture the structural response characteristics of reinforced concrete shear walls under internal blast loading

5.4. Effect of TNT Mass and Reinforcement Ratio

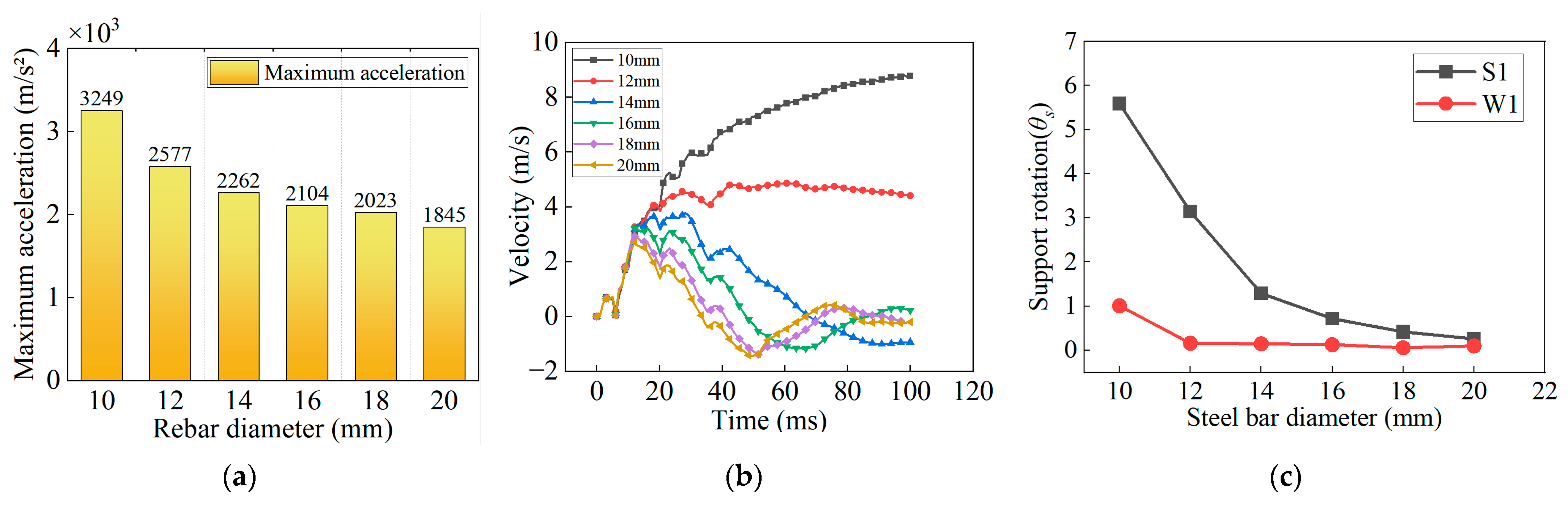

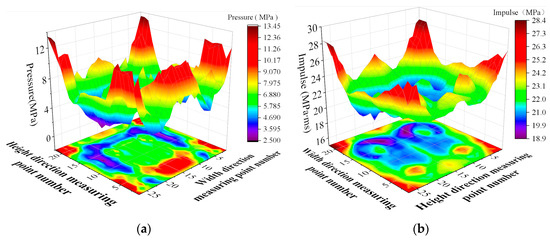

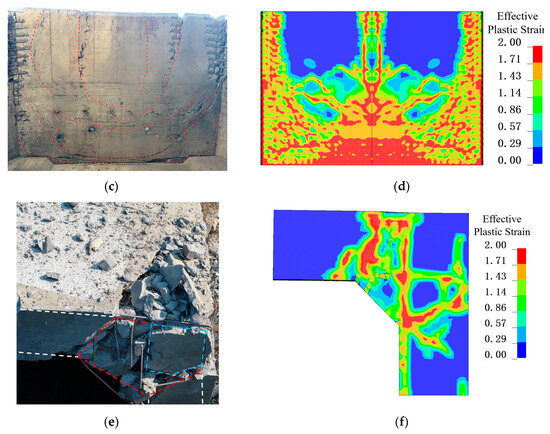

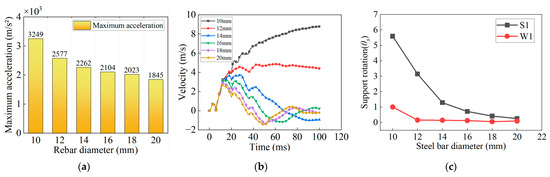

The magnitude of the blast load and the inherent strength of the structure are the key factors determining the final damage. To investigate these effects, a validated numerical simulation method was employed for parametric analysis. Models with TNT masses of 100 kg, 300 kg, 400 kg, and 500 kg were established to study the effect of different blast loads on structural damage. Meanwhile, models with reinforcement diameters of 10 mm, 12 mm, 14 mm, 18 mm, and 20 mm (corresponding reinforcement ratios of 0.13%, 0.18%, 0.25%, 0.42%, and 0.52%) were created to examine the influence of steel reinforcement on controlling structural failure modes.

Table 7 presents the computational results for different models. Peak and residual deflections were measured at the mid-span of the free end of S1. In the cases of W400-16, W500-16, W200-10, and W200-12, the reinforcement at the S1 supports fractured and was ejected, so deflection data for these models were not recorded. Increasing TNT mass had a significantly adverse effect on structural damage. For example, the TNT masses in W200-16 and W300-16 were 2 and 3 times that of W100-16, yet the peak deflections of S1 were 4.03 and 11.6 times higher, and residual deflections were 3.7 and 10 times higher, respectively. Increasing the reinforcement ratio reduced structural deformation: for W200-18 and W200-20, which had reinforcement ratios 1.68 and 2.08 times that of W200-14, peak deflections decreased by 56.5% and 65.2%, and residual deflections decreased by 66.8% and 70.1%.

Table 7.

Model parameters and deflection results.

Figure 23 shows the damage states of the models at 100 ms for different TNT charges. When the TNT mass is 100 kg, the structure primarily experiences punching-shear failure along the supports, with limited overall deformation. The shear cracks are very narrow, indicating that structural damage is mainly governed by the local response stage. When the TNT mass increases to 300 kg, in addition to the support cracks, the walls and slabs exhibit significant bulging deformation, plastic hinges form at the nodes, and most of the concrete on the blast-facing surfaces fails. For TNT masses above 400 kg, the side walls undergo overall shear failure at the supports, while the top slab shows complete concrete failure at the three supports and mid-span; most of the lower reinforcement in the nodes fractures, and the upper reinforcement carries all the tensile load. The slab splits into two parts at mid-span, forming a reversed “catenary” effect, with the two fractured portions primarily in tension, connected only by the nodes and unbroken mid-span reinforcement, showing a tendency toward structural collapse. When the TNT equivalent further increases to 500 kg, the outward expansion of the components becomes more pronounced. During large deformations, the reinforcement reaches its ultimate strength but still cannot absorb all the kinetic energy, resulting in fracture at the nodes and eventual structural disintegration.

Figure 23.

Structural failure states under different TNT qualities. (a) 100 kg; (b) 300 kg; (c) 400 kg; (d) 500 kg.

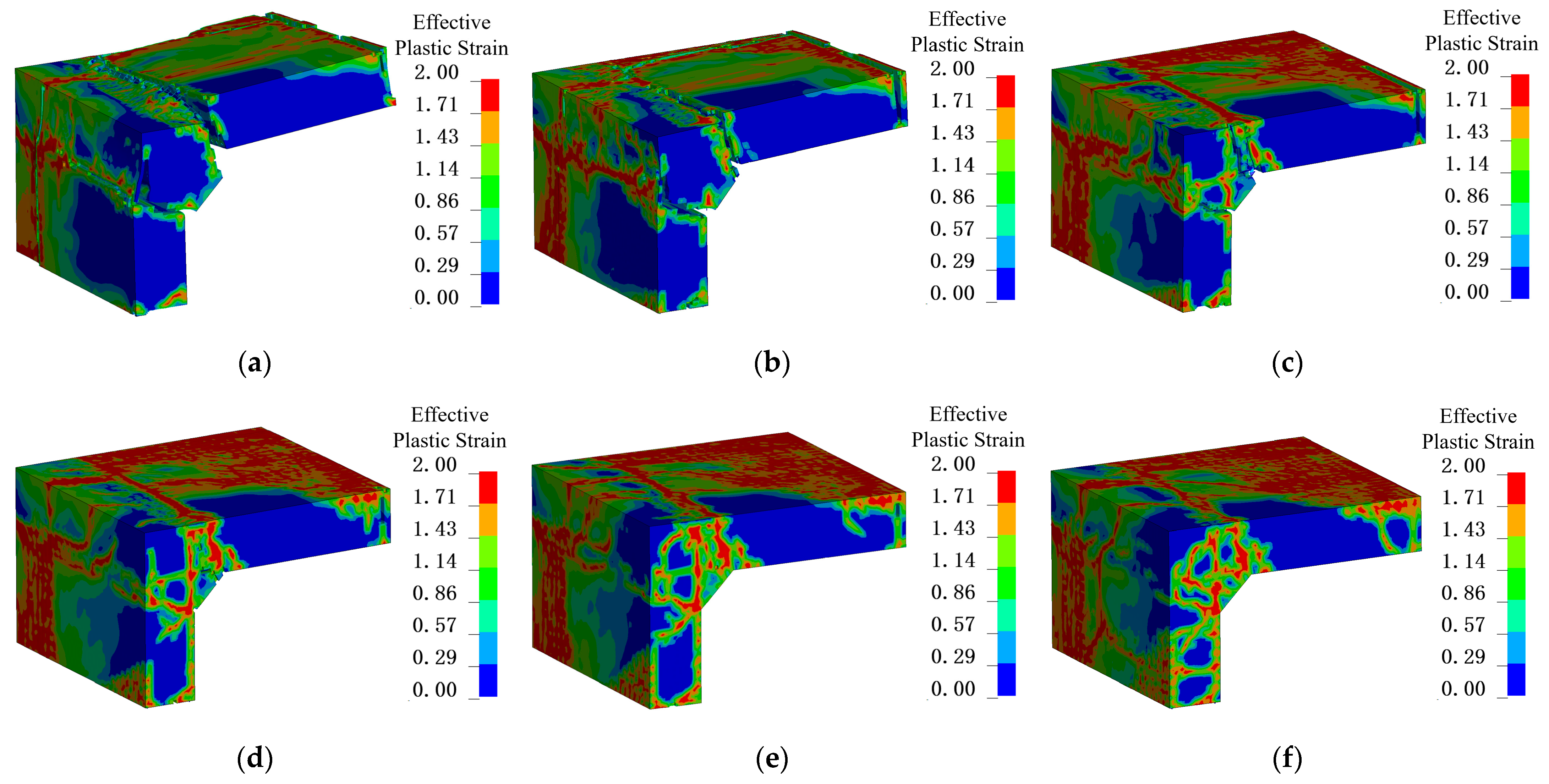

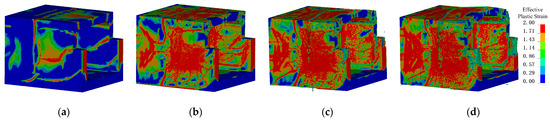

Figure 24 shows the detailed failure patterns of J1 under different reinforcement diameters. When the reinforcement ratio is low (0.13% and 0.19%), the node exhibits pronounced brittle characteristics. After the local response stage, the reinforcement at the supports is unable to restrain the widening of the shear cracks, and the wall–slab node separates entirely from the surrounding elements. At this stage, aside from the shear failure surfaces, the damage to the core concrete of the node is relatively minor. Comparatively, when the reinforcement diameter is smallest, the overall damage extent of the node is minimal, but the shear cracks are widest. As the reinforcement diameter increases, the crack width gradually decreases, while the damage extent of the node expands. This occurs because higher reinforcement ratios enhance the node’s ability to restrain shear crack widening, causing the failure mode to shift from a single wide crack to multiple narrower cracks.

Figure 24.

Failure patterns of J1 under different reinforcement diameters. (a) 10 mm; (b) 12 mm; (c) 14 mm; (d) 16 mm; (e) 18 mm; (f) 20 mm.

Figure 25 shows the mid-span velocity response at the free end and support rotation of S1 under different reinforcement diameters. The maximum mid-span acceleration generally occurs just as the structure is first impacted by the blast wave. When the reinforcement ratio is relatively high, the structure exhibits greater stiffness and a shorter natural period. As a result, before the blast load fully dissipates, the structure begins releasing stored elastic energy, which limits the acceleration peak. The reinforcement primarily contributes during the large-deformation stage, so its effect on controlling mid-span velocity and support rotation is significant. However, this effect is not linear: as the reinforcement ratio increases, the trends of mid-span velocity and support rotation tend to plateau. This occurs because, at high reinforcement ratios, the overall deformation is small and mainly caused by micro-cracks in the concrete, over which the reinforcement has limited control.

Figure 25.

Effect of reinforcement diameter on structural dynamic response. (a) Maximum mid-span acceleration. (b) Mid-span velocity. (c) Wall and slab support rotation.

6. Conclusions

This study conducted a 200 kg TNT internal blast test on a full-scale reinforced concrete (RC) shear wall structure, recording the internal blast pressure history and observing damage in different regions of the structure. A detailed numerical analysis model was established and validated against experimental results. The failure process and damage mechanisms under internal blast were clarified, and the propagation characteristics and pressure distribution of blast waves within the structure were analyzed. Additionally, the effects of TNT charge and reinforcement ratio on structural damage were investigated.

Due to the complexity of full-scale explosion tests, the experimental data provided in this study can be used to validate computational models of reinforced concrete shear walls subjected to internal explosions. The findings of this research offer guidance for the design and safety evaluation of industrial protective structures, particularly for hazardous chemical storage rooms and explosion-resistant chambers of high-pressure reactors. The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

- Under TNT internal blast, RC shear walls exhibit reflected stress wave damage, shear damage, and bending damage. Geometric and stiffness discontinuities at wall-slab joints, combined with stress wave reflections, lead to significant stress concentrations at the joints. Shear cracks consistently appear in wall-slab joint regions, and large crack bands form at supports, representing the primary damage type. In the design of reinforced concrete blast-resistant chambers, priority should be given to enhancing structural joints and improving anchorage, rather than simply increasing the wall thickness.

- The structural damage process can be divided into three stages: a local response stage, a shear–bending combined damage stage, and a global inertia-dominated stage. In the first stage, structural deformation is minimal, with concrete primarily resisting the blast load and reinforcement stress remaining low. In the second and third stages, deformation increases and reinforcement begins to carry tensile force. When joint shear strength is insufficient, global failure occurs in the second stage with minimal bending of the components. If reinforcement strength is inadequate, support reinforcement may fracture in the third stage, causing components to detach from the joints.

- In a semi-enclosed structure, the superposition of reflected waves on different surfaces produces pressures higher than those from direct blast incidence. At wall-slab joints, the maximum pressure increases with the propagation distance of the blast wave. Maximum reflected pressures and impulses occur at the four corners of the structure, with the top and bottom corners of the blast-facing wall exceeding the center by 51.1% and 47.3%, respectively.

- Even with a relatively small TNT charge, shear failure tends to occur at supports because concrete and reinforcement have limited cooperative capacity during the local response stage. Reinforcement ratio plays a key role in controlling the ultimate failure mode. During global response, deformation is primarily controlled by reinforcement. Low reinforcement ratios (0.13% and 0.19%) lead to brittle failure after local shear damage, as reinforcement cannot restrain the component’s kinetic energy and fractures. Increasing the reinforcement ratio effectively limits structural deflection and support rotation but exhibits diminishing returns. Raising the reinforcement ratio from 0.33% to 0.42% and 0.52% reduces the maximum mid-span deflection at the free end of the slab by 31.3% and 47.5%, and residual deflection by 39.3% and 59.1%, respectively.

- Based on the damage characteristics of reinforced concrete shear walls subjected to internal blast loads obtained in this study, practical engineering applications may adopt strategies such as locally increasing the reinforcement ratio or using locally cast high-strength concrete. These approaches help avoid excessively large structural dimensions and overly congested reinforcement. In addition, the tests provide full-scale internal explosion data for shear wall structures, including pressure–time histories, crack patterns, and residual deflections. Researchers and engineers can use these data to calibrate and validate computational models, thereby reducing the development cost of blast prediction tools.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.S.; Writing—Original Draft, H.S. and W.G.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.L., W.G. and H.S.; Visualization, H.S., W.P. and H.L.; Software, W.G. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, C.F.; Chen, J.Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.J. Damage Mechanism and Response of Reinforced Concrete Containment Structure under Internal Blast Loading. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2012, 61, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yan, Q.; Zhuang, T.S.; Yang, C. Structural Design and Damage Assessment of a Chamber for Internal Blast with Explosion Vent. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2020, 27, 2052–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Hao, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, W. Review of the Current Practices in Blast-Resistant Analysis and Design of Concrete Structures. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2016, 19, 1193–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tascón, A. Design of Silos for Dust Explosions: Determination of Vent Area Sizes and Explosion Pressures. Eng. Struct. 2017, 134, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulei, Z.; Jianjun, S.U.; Zhirong, L.I.; Haiyan, J.; Kai, Z.; Shengqiang, W. Quasi-Static Pressure Characteristic of TNT’s Internal Explosion. Explos. Shock. 2018, 38, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Farrimond, D.G.; Woolford, S.; Barr, A.D.; Lodge, T.; Tyas, A.; Waddoups, R.; Clarke, S.D.; Rigby, S.E.; Hobbs, M.J.; Willmott, J.R.; et al. Experimental Studies of Confined Detonations of Plasticized High Explosives in Inert and Reactive Atmospheres. Proc. A 2024, 480, 20240061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, Y.; McCrum, D.P.; Hu, Y.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. A Reinforced Concrete Shear Wall Building Structure Subjected to Internal TNT Explosions: Test Results and Numerical Validation. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2024, 190, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.E., Jr.; Baker, W.E.; Wauters, D.K.; Morris, B.L. Quasi-Static Pressure, Duration, and Impulse for Explosions (Eg HE) in Structures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 1983, 25, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, M.; Casadei, F.; Valsamos, G.; Larcher, M.; Hauge, K.O.; Minoretti, A.; Børvik, T. Semi-Confined Blast Loading: Experiments and Simulations of Internal Detonations. Shock Waves 2024, 34, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Jia, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Shang, W. Damage of Full-Scale Reinforced Concrete Beams under Contact Explosion. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2022, 163, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yang, C.; Yin, T.; Jia, J.; Yu, J.; Song, J. Blast Resistant Performance and Damage Mechanism of Steel Reinforced Concrete Beams under Contact Explosion. Eng. Struct. 2024, 315, 118472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, D.; Lu, F.; Wang, S.-C.; Tang, F. Experimental Study on Scaling the Explosion Resistance of a One-Way Square Reinforced Concrete Slab under a Close-in Blast Loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2012, 49, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Bonora, N.; Curiale, G.; De Muro, S.; Iannitti, G.; Marfia, S.; Sacco, E.; Scafati, S.; Testa, G. Full Scale Experimental Tests and Numerical Model Validation of Reinforced Concrete Slab Subjected to Direct Contact Explosion. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2019, 132, 103309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, A.; Braimah, A.; Kumar, M. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Rectangular Reinforced Concrete Columns under Contact Explosion Effects. Eng. Struct. 2020, 205, 109891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wu, W.; Guo, P.; Xia, L. Damage Modes and Mechanism of RC Arch Slab under Contact Explosion at Different Locations. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2022, 170, 104360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, G.A.O.; Xiangzhen, K.; Qin, F.; Yin, W.; Ya, Y. Numerical Study on Attenuation of Stress Wave in Concrete Subjected to Explosion. Explos. Shock 2022, 42, 123202-1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wu, C.; Hao, H. Investigation of Ultra-High Performance Concrete Slab and Normal Strength Concrete Slab under Contact Explosion. Eng. Struct. 2015, 102, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Peng, Y.; Xu, S.; Yuan, P.; Qu, K.; Yu, X.; Hu, F.; Zhang, W.; Su, Y. Investigation of Geopolymer-Based Ultra-High Performance Concrete Slabs against Contact Explosions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 315, 125727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, C.; Hao, H.; Wang, Z.; Su, Y. Experimental Investigation of Ultra-High Performance Concrete Slabs under Contact Explosions. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2016, 93, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, J.; Zhao, H.; Jia, Y.; Fang, H.; Wang, J.; Yao, Y.; Wei, D. Experimental and Mesoscopic Modeling Numerical Researches on Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Slabs under Contact Explosion. In Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 61, p. 106114. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, B.; Liu, G. Experimental Study on Spall Resistance of Steel-Fiber Reinforced Concrete Slab Subjected to Explosion. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.; Mu, C.; Xia, M.; Yang, S. A Research Investigation into the Impact of Reinforcement Distribution and Blast Distance on the Blast Resilience of Reinforced Concrete Slabs. Materials 2023, 16, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiagarajan, G.; Kadambi, A.V.; Robert, S.; Johnson, C.F. Experimental and Finite Element Analysis of Doubly Reinforced Concrete Slabs Subjected to Blast Loads. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2015, 75, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, R.; Wang, M.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y. Explosion Resistance Performance of Reinforced Concrete Box Girder Coated with Polyurea: Model Test and Numerical Simulation. Def. Technol. 2024, 33, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, D.L.; Park, S.W.; Zhou, M. Dynamic Behavior of Concrete at High Strain Rates and Pressures: I. Experimental Characterization. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2001, 25, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A.; Tedesco, J.W.; Kuennen, S.T. Effects of Strain Rate on Concrete Strength. Mater. J. 1995, 92, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.; Hao, H. Numerical Evaluation of the Influence of Aggregates on Concrete Compressive Strength at High Strain Rate. Int. J. Prot. Struct. 2011, 2, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50779-2022; Standard for Design of Blast Resistant Buildings in Petrochemical Enterprise. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Fan, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhou, T.; Ding, S.; Zhao, J.; Tian, B. Dynamic Response of Air-Backed Prestressed Reinforced Concrete Slab Subjected to Underwater Explosion. In Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 70, p. 107935. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Fan, Y.; Wang, G.; Cui, X.; Leng, Z.; Lu, W. Blast Resistance of Air-Backed RC Slab against Underwater Contact Explosion. Def. Technol. 2023, 28, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yue, Y.; Zhu, B.; Chen, Y. Failure Analysis of Underground Concrete Silo under Near-Field Soil Explosion. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 147, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alañón, A.; Cerro-Prada, E.; Vázquez-Gallo, M.J.; Santos, A.P. Mesh Size Effect on Finite-Element Modeling of Blast-Loaded Reinforced Concrete Slab. Eng. Comput. 2018, 34, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracamonte, A.J.; Mercado-Puche, V.; Martínez-Arguelles, G.; Pumarejo, L.F.; Ortiz, A.R.; Herazo, L.C.S. Effect of Finite Element Method (FEM) Mesh Size on the Estimation of Concrete Stress–Strain Parameters. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manual, K.U. LS-DYNA Keyword User’s Manual; LSTC Co.: Livermore, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Song, J.; Jia, J.; Li, Z. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Steel–Concrete Composite Beam Subjected to Contact Explosion. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2024, 187, 104916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Deng, S.; Song, X.; Wang, M. Experimental and Numerical Study of Corrugated Steel-Plain Concrete Composite Structures under Contact Explosions. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 197, 111624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvar, L.J.; Crawford, J.E.; Wesevich, J.W.; Simons, D. A Plasticity Concrete Material Model for Dyna3D. Int. J. Impact Eng. 1997, 19, 847–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Fang, Q.; Li, Q.M.; Wu, H.; Crawford, J.E. Modified K&C Model for Cratering and Scabbing of Concrete Slabs under Projectile Impact. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2017, 108, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Fang, H.; Zhao, X. The Dynamic Response and Damage Models of Rebar Reinforced Polymer Slabs Subjected to Contact and Near-Field Explosions. Def. Technol. 2023, 28, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z. Numerical Simulation of Reinforced Concrete Slab Subjected to Blast Loading and the Structural Damage Assessment. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 118, 104926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Li, M.; Cao, W.; Chen, K.; Xue, P.; Huang, H.; Hua, C.; Gao, D. Numerical Simulations of Trajectories of Shock Wave Triple Points in Near-Ground Explosions of TNT Charges. Energetic Mater. Front. 2022, 3, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.