Influence of Segment Width on Tunnel Deformation and Ground Settlement in Shield Tunneling Beneath Residential Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Engineering Overview

2.1. Project Introduction

2.2. Geological Conditions

3. Numerical Simulation Analysis

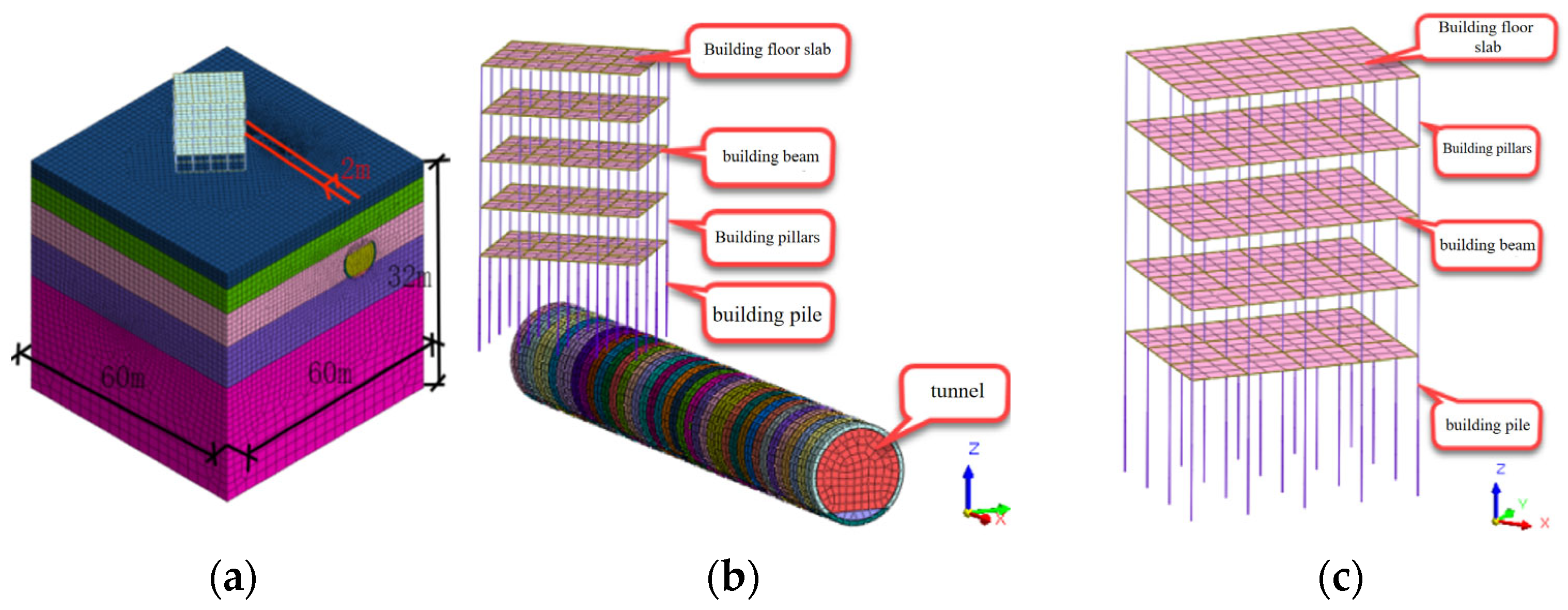

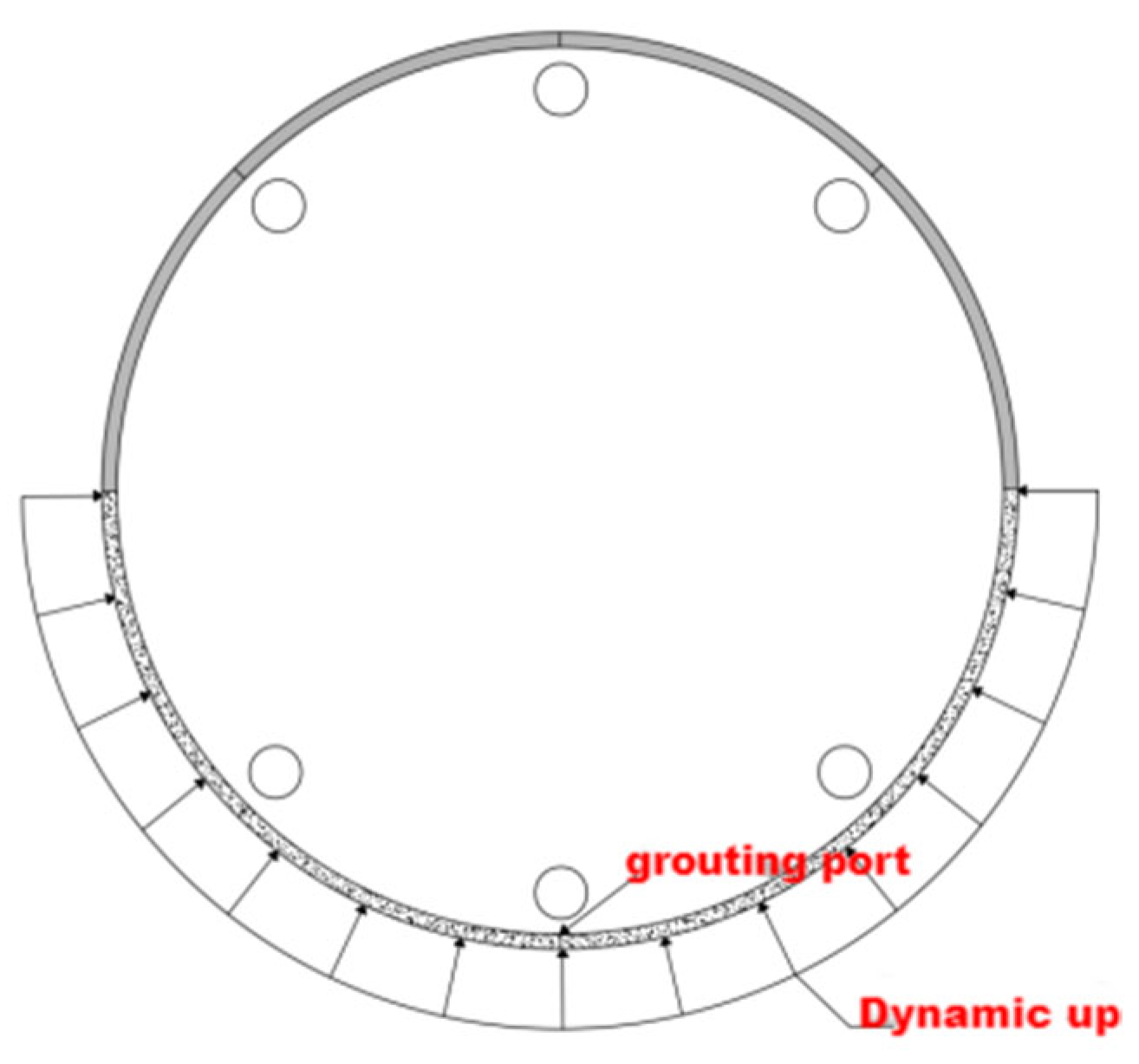

3.1. Model Establishment

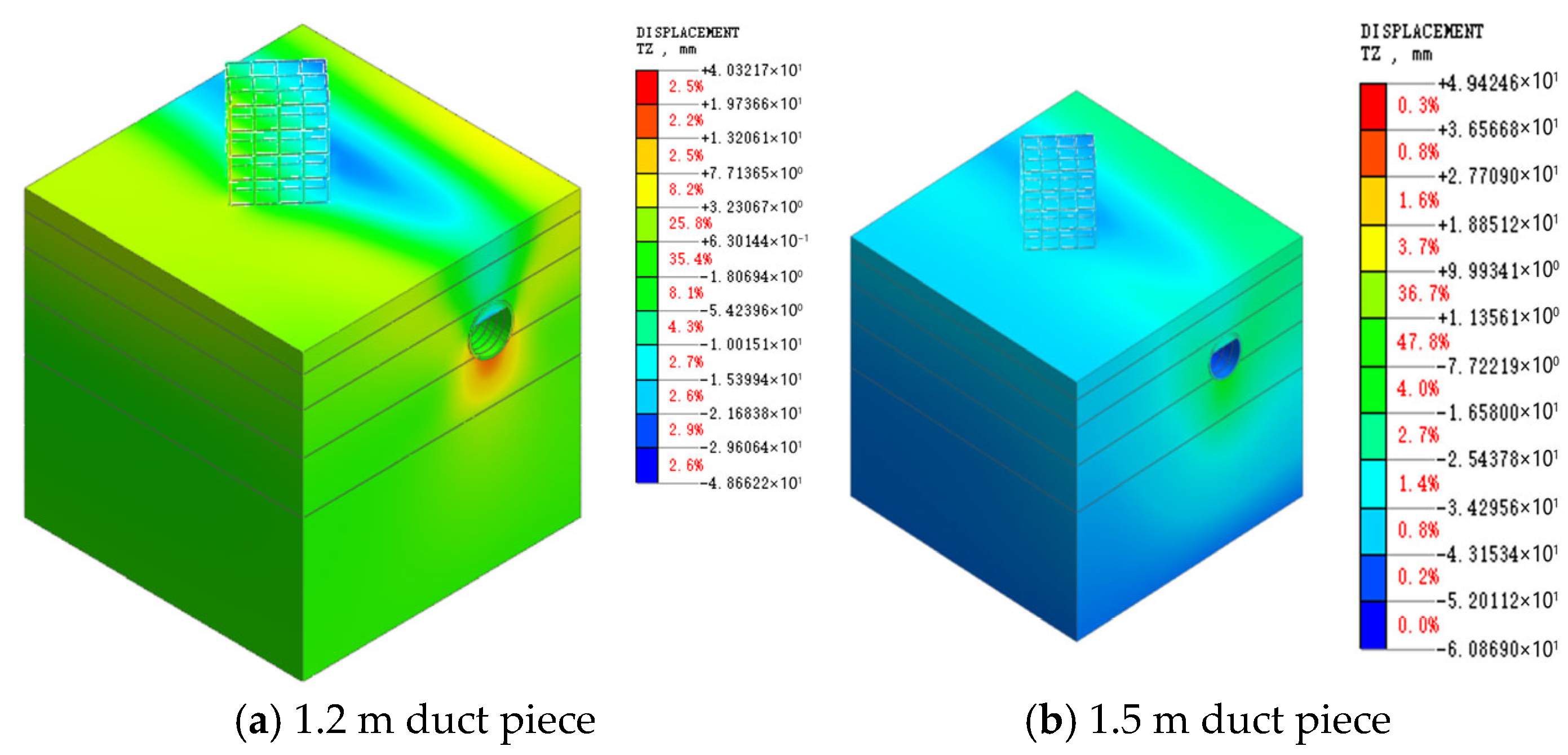

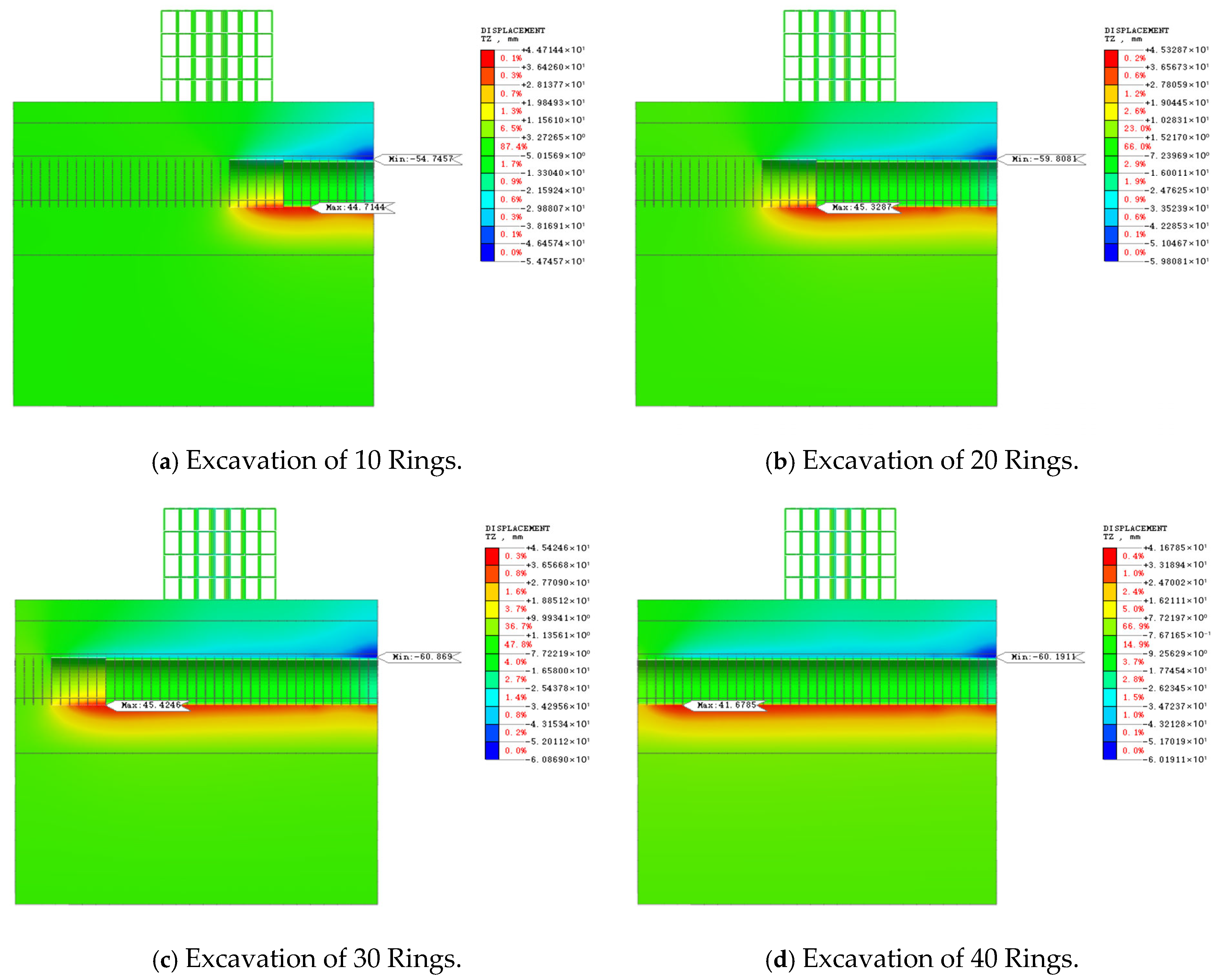

3.2. Analysis of Ground Deformation Results

3.3. Analysis of the Displacement Result of Shield Tunnel Segment

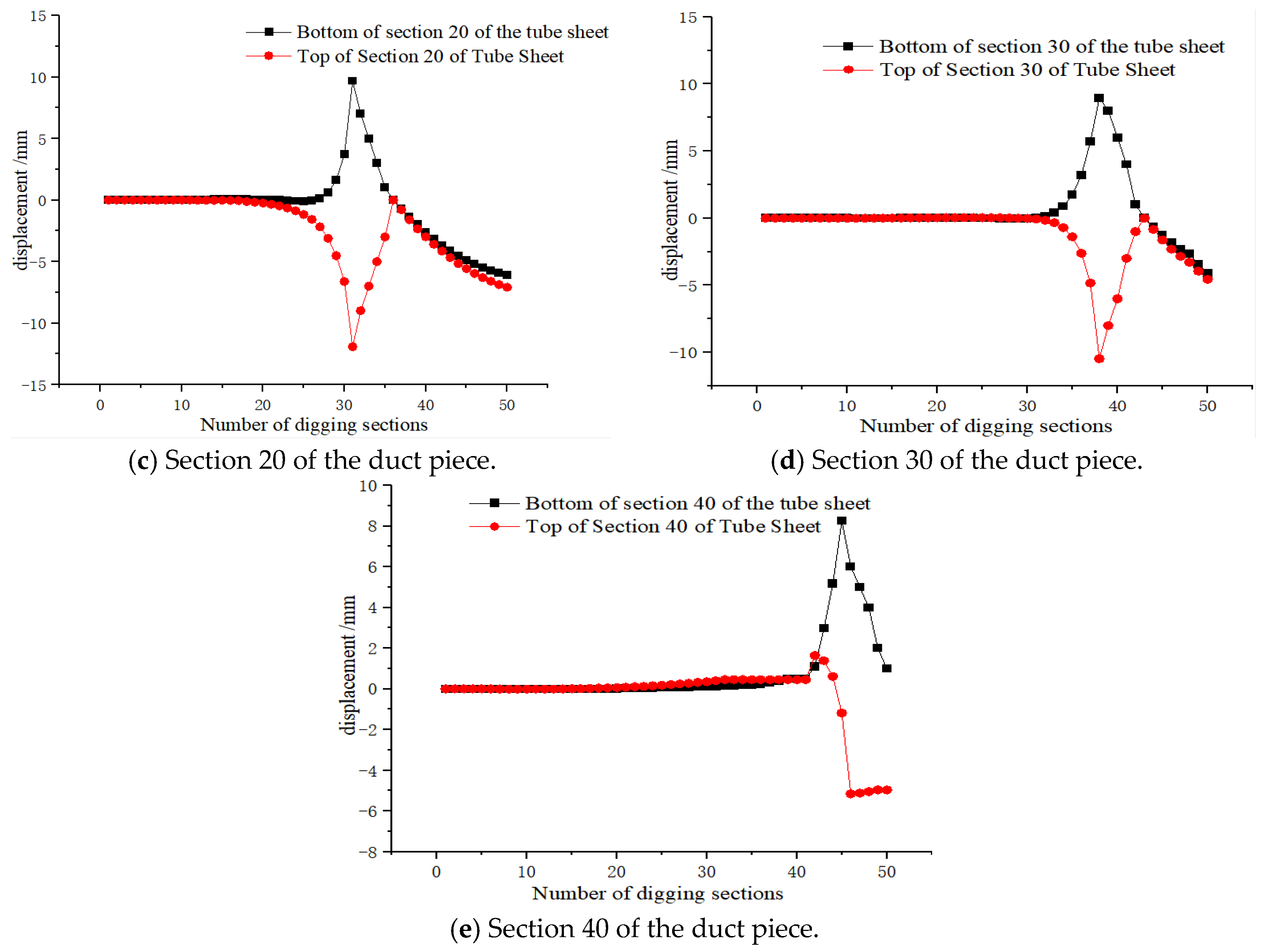

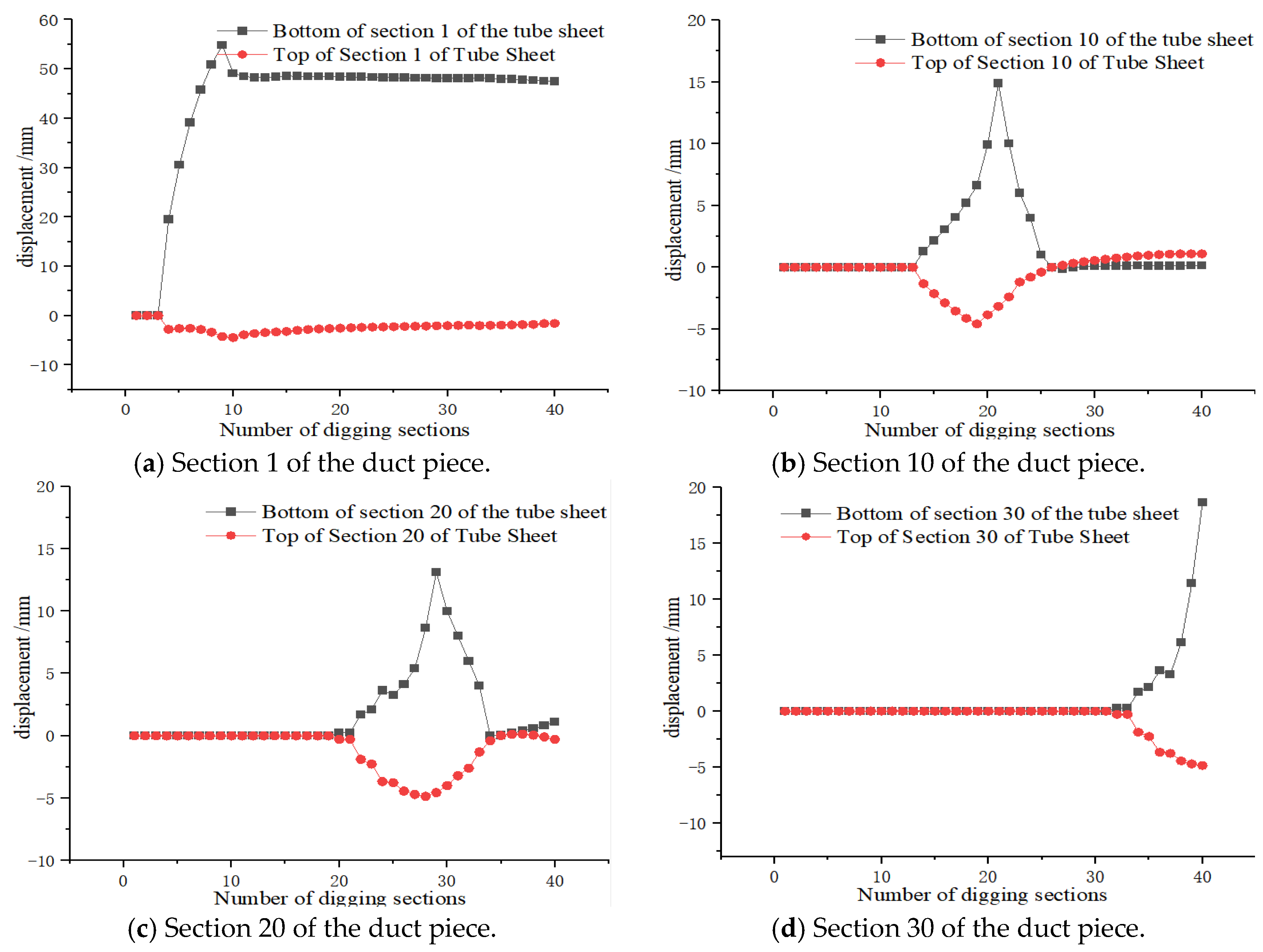

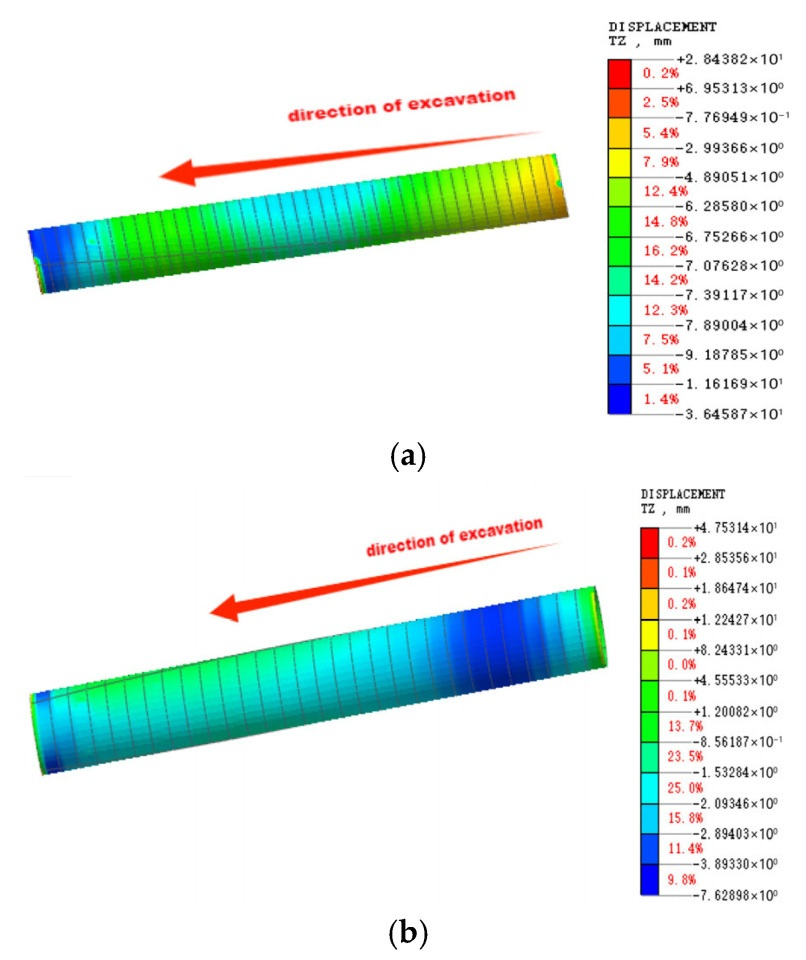

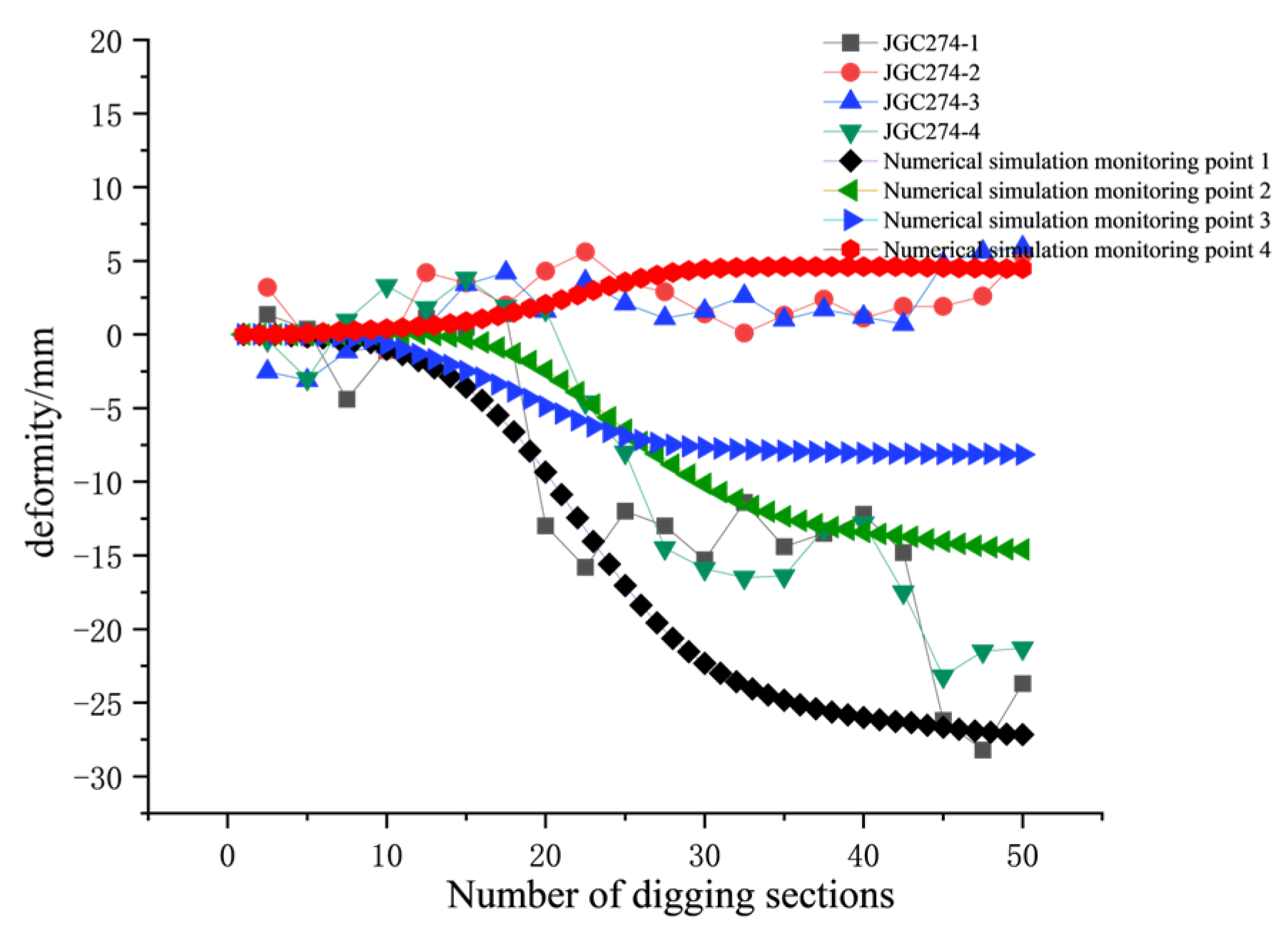

3.3.1. Analysis of Segment Displacement During Shield Tunnel Excavation

3.3.2. Analysis of Overall Displacement Cloud Map of Shield Tunnel

4. Analysis of Measured Engineering Results

4.1. Ground Settlement Analysis

4.2. Analysis of Final Segment Displacement

5. Discuss

5.1. The Influence of Pipe Segment Width on Formation Deformation

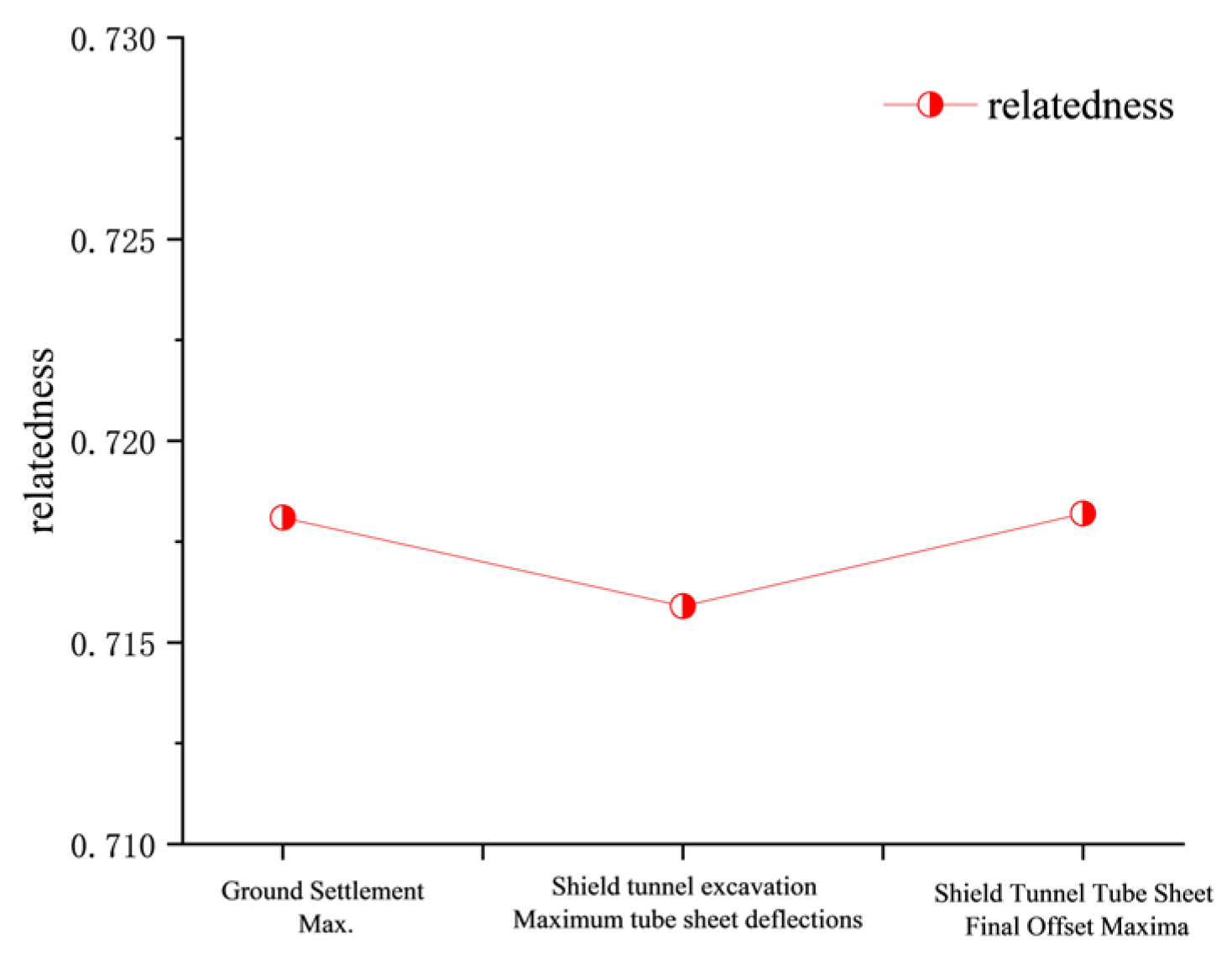

5.2. Gray Relational Analysis of Influencing Factors Related to Segment Width

6. Results

- During tunnel excavation, the 1.2 m segments primarily induced settlement deformation, with a maximum ground deformation of −48.66 mm, whereas the 1.5 m segments produced uplift-dominated deformation, reaching a maximum value of 49.82 mm. For both segment widths, significant deformation occurred above the tunnel crown and beneath the tunnel invert.

- The maximum displacements recorded at each monitoring ring for the 1.5 m segments were consistently larger than those for the 1.2 m segments, with the peak displacement reaching 47.73 mm (compared with −37.681 mm for the 1.2 m segments). This indicates that the 1.2 m segment width provides better displacement control performance.

- After tunnel breakthrough, the displacement associated with the 1.2 m segments remained settlement-dominated, whereas the 1.5 m segments exhibited repeated transitions between settlement and uplift with increasing ring number. The maximum deformation for both widths occurred at Ring 1, and the peak displacement for the 1.5 m segments was close to the 50 mm warning threshold, further confirming the superior deformation control capability of the 1.2 m segments.

- The numerical simulation results demonstrated good agreement with field monitoring data, with error rates of 3.43%, 3.92%, and 5.17% for maximum settlement, uplift, and segment displacement, respectively. Gray relational analysis further revealed that the influence of segment width on deformation indicators decreases in the following order: maximum segment displacement during excavation, maximum ground deformation, and final post-excavation segment displacement.

- This study was conducted under specific geological conditions involving underpassing residential buildings. The mechanisms governing the influence of segment width may vary among different ground types (e.g., soft soil, rock formations), and the present work focuses primarily on the widely used 1.2 m and 1.5 m segment widths. Future research could expand the comparative analysis across diverse geological environments to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, this study does not account for the coupled effects of segment material properties, assembly procedures, and other construction factors, which may interact with segment width to influence tunnel deformation. Incorporating multifactor coupling models in future studies would provide a more comprehensive understanding of segment deformation mechanisms.

- 6.

- Exploring the compatibility between geological conditions and segment width to develop a dynamic segment width decision-making model based on ground characteristics;

- 7.

- Conducting multi-variable collaborative optimization involving segment width, material parameters, and construction parameters to enhance overall deformation control efficiency;

- 8.

- Integrating large-scale field monitoring data with artificial intelligence algorithms to achieve intelligent prediction of segment width selection and deformation warnings, thereby providing more precise technical support for shield tunneling in complex engineering environments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khabbaz, H.; Gibson, R.; Fatahi, B. Effect of constructing twin tunnels under a building supported by pile foundations in the Sydney central business district. Undergr. Space 2019, 4, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L.; Hu, Y.T. Research on the Calculation of the Total Floating Amount of Segment Considering the Degree of Soil Arching Effect. RCT 2023, 12, 112–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, K. Deformation analysis and control measures for shield tunnel passing under complex buildings. Urban Mass Transit 2023, 26, 62–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, J. Deformation Analysis of Yangtze River Embankment Crossed by Ultra-large Diameter Shield Tunneling in Soft and Water-rich Strata. Sci. Tec. Eng. 2024, 24, 11842–11850. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.Z.; Ji, Y.T.; Zhao, L.G. Influence Law and Control Measures of Shield Tunnel Undercrossing High Speed Railway Station: Taking the Tianjin Metro Line 4 as an Example of Undercrossing Tianjin West Station. J. Sci. Tec. Eng. 2024, 24, 13601–13611. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.Z.; Niu, Y.F.; Wang, R. Influence of Underpass of Subway Shield Tunnel on Surface Building. Con. Qual. 2023, 41, 66–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Qi, Y.J.; Wu, H.J. Changes in circumferential pressure and stresses in existing tunnels caused by tunnel crossing. J. Cent. South Univ. 2020, 51, 515–3527. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, Z.; Wang, S. Study on the Seismic Response Characteristics of Shield Tunnels with Different General Segment Assembly Methods and Widths. Buildings 2023, 13, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.X. Effect of Segment Width on Behavior of Shield Tunnel Assembledin Staggered Pattern. Chin. J. U Space Eng. 2015, 11, 852–858. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Lin, Y.; Li, X. Deformation and adjustment mechanism of segment joint in shield tunneling. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 16, 1622–11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Feng, K. Shear deformation characteristics and failure mechanisms of tunnel segment inter-ring joints: Numerical and experimental study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 158, 108045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, W.S.; Song, K.I.; Kim, K.Y.Y.; Ryu, H.H. Development of Grouting Quality Evaluation System for a Shield TBM Tunnel Using the Impact-Echo Method. Ksce. J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 5335–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50157-2013; Code for Design of Metro. China Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Armen, Z.; Ter, M.; Anzhelo, G.O.; Rud, V.V. The Influence of Metro Tunnel Construction Parameters on the Settlement of Surrounding Buildings. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.H.; Xiao, J.H.; Di, H.G.; Zhu, Y.H. Differential settlement remediation for new shield metro tunnel in soft soils using corrective grouting method: Case study. Can. Geotech. J. 2018, 55, 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bao, X.K. Study on Reinforcement Technology of Shield Tunnel End and Ground Deformation Law in Shallow Buried Silt Stratum. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhu, F.J.; Ge, Z.W.; Hu, H.Q. Prediction and Analysis of Subsurface Settlement in a Double-Line Shield Tunnel. J. Geotech. Geoenviron 2024, 150, 12570–12590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q. Numerical Simulation of Mudstone Shield Tunnel Excavation with ABAQUS Seepage–Stress Coupling: A Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 15, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Jeon, S.; Jeon, S. Study on the behaviour of pre-existing single piles to adjacent shield tunnelling by considering the changes in the tunnel face pressures and the locations of the pile tips. Geomech. Eng. 2020, 21, 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.G.; Yang, T.R.; Xie, J.N. Research on control measures of large-diameter shield tunnel undercrossing existing high-speed railway line. J. Civil. Eng. 2024, 57, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, R.R.; Li, Y.J.; He, C.; Zhu, D.Q.; Li, Y.F. Study on Deformation Characteristics of the Segment in the Underwater Shield Tunnel with Varying Earth Pressure. Buildings 2024, 14, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Yuan, D.J.; Zhou, S.X.; Zhao, D. Short-Term and Long-Term Displacement of Surface and Shield Tunnel in Soft Soil: Field Observations and Numerical Modeling. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3564. [Google Scholar]

- Lueprasert, P.; Jongpradist, P.; Jongpradist, P.; Suwansawat, S. Numerical investigation of tunnel deformation due to adjacent loaded pile and pile-soil-tunnel interaction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 70, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Y.T.; Liu, H.Q.; Liu, H.B. Seismic response of a shield tunnel crossing saturated sand deposits with different relative densities. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 166, 107790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Bu, X.B.; Zeng, K.; Xie, X.Y.; Zeng, H.B. Optimization study for cement-based grout mixture ratio of shield tunnel considering spatiotemporal evolution of grout buoyancy. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 442, 137600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Q. Theoretical analysis of floating of through-seam segment in shield tunnel. Urban Roads Bridges Flood Control 2023, 42, 2683–2695. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.B.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wang, X. Staged sensing method of fault sudden water based on gray correlation analysis. Chin. J. Undergr. Chin. Saf. Sci. 2024, 34, 63–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Oh, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Chang, S. Monitoring and Analysis of Ground Settlement Induced by Tunnelling with Slurry Pressure-Balanced Tunnel Boring Machine. Electron. Newsweekly 2018, 2018, 393–415. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Zhu, H.H.; Ding, W.Q. Longitudinal uplift analysis of shield tunnel based on elastic foundation beam. Chin. Rail. Sci. 2008, 4, 65–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Talmon, A.; Bezuijen, A. Analytical model for the beam action of a tunnel lining during construction. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Met. 2013, 37, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level Number | Layer Description | Geological Diagram | Thickness (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <1> | Artificial fill; soil properties: loose to moderately compacted; soil type: medium soft soil |  | 2.4 |

| <2> | Sludge; rock and soil properties: plastic; soil type: weak soil | 4.5 | |

| <3> | Fine clay; rock and soil properties: plastic; soil type: medium soft soil | 3.2 | |

| <4> | Full weathered clastic rock; lithological properties: hard silt-like soil; soil type: medium-hard soil | 3 | |

| <5> | Medium-grained weathered sandstone; rock and soil characteristics: the rock mass is relatively intact | 7 |

| Layer Name | Stratigraphic Depth (m) | Specific Weight (kN·m−3) | Bulk Modulus (MPa) | Modulus of Shearing, Shear Modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miscellaneous fill | 2.2 m | 20.2 | 4.38 | 15 |

| silty clay | 3.5 m | 19.9 | 5.17 | 19.2 |

| Well weathered argilliferous mudstone | 5.3 m | 20.3 | 5.47 | 26 |

| Strongly weathered coarse sandstone | 6 m | 20.6 | 5.81 | 24 |

| Weathered coarse sandstone | 15 m | 25.7 | 5.93 | 28 |

| Structure Name | Thickness (mm) | Severe (kN·m−3) | Modulus of Elasticity (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| duct piece | 320 | 27 | 25.87 |

| Grouting Layer (liquid state) | 160 | 25 | 1.7 |

| Grouting Layer (concreting) | 160 | 20 | 25 |

| Segment Width | Maximum Deformation of Strata | Maximum Displacement of Segment During Excavation | Maximum Displacement of Segment After Excavation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 m | −61.67 mm | −41 mm | −39.41 mm |

| 1.2 m | −48.66 mm | −38 mm | −36.45 mm |

| 1.5 m | 49.52 mm | 55 mm | 47.73 mm |

| Gray correlation results | 0.7181 | 0.7159 | 0.7182 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, P.; Bao, X. Influence of Segment Width on Tunnel Deformation and Ground Settlement in Shield Tunneling Beneath Residential Areas. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010047

Song P, Bao X. Influence of Segment Width on Tunnel Deformation and Ground Settlement in Shield Tunneling Beneath Residential Areas. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Pengjie, and Xiankai Bao. 2026. "Influence of Segment Width on Tunnel Deformation and Ground Settlement in Shield Tunneling Beneath Residential Areas" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010047

APA StyleSong, P., & Bao, X. (2026). Influence of Segment Width on Tunnel Deformation and Ground Settlement in Shield Tunneling Beneath Residential Areas. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010047