Abstract

Currently, the formation and evolution processes of overpressure in the Upper Paleozoic tight sandstones of the Ordos Basin are not clearly understood. Taking the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the Yanchang area, southeastern Ordos Basin, as an example, we adopted a numerical simulation method considering pressurization effects (e.g., hydrocarbon generation and disequilibrium compaction) to quantitatively reconstruct the paleo-overpressure evolution history of target sandstone and shale layers before the end of the Early Cretaceous. We calculated two types of formation pressure changes since the Late Cretaceous tectonic uplift: the pressure reduction induced by pore rebound, temperature decrease and pressure release from potential brittle fracturing of overpressured shales, and the pressure increase in tight sandstones caused by overpressure transmission, thus clarifying the abnormal pressure evolution process of the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation tight sandstones in the study area. The results show that at the end of the Early Cretaceous, the formation pressures of the target shale and sandstone layers in the study area reached their peaks, with the formation pressure coefficients of shale and sandstone being 1.41–1.59 and 1.10, respectively. During tectonic uplift since the early Late Cretaceous, temperature decrease and brittle fracture-induced pressure release caused significant declines in shale formation pressure, by 12.95–17.75 MPa and 20.00–25.24 MPa, respectively, resulting in the current shale formation pressure coefficients of 1.00–1.06. In this stage, temperature decrease and pore rebound caused sandstone formation pressure to decrease by 12.07–13.85 MPa and 16.93–17.41 MPa, respectively. Meanwhile, the overpressure transfer from two phases of hydrocarbon charging during the Late Triassic–Early Cretaceous and pressure release from shale brittle fracture during the Late Cretaceous tectonic uplift induced an increase in adjacent sandstone formation pressure, with a total pressure increase of 7.32–8.58 MPa. The combined effects of these three factors have led to the evolution of the target sandstone layer from abnormally high pressure in the late Early Cretaceous to the current abnormally low pressure. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of the formation process of underpressured gas reservoir in the Upper Paleozoic of the Ordos Basin.

1. Introduction

The formation and evolution of abnormal pressure play a crucial role in controlling the accumulation and preservation of hydrocarbons, and represent one of the key scientific issues in the field of petroleum-bearing basin research. Globally, underpressure reservoirs are widely developed in shallow low-permeability strata following tectonic uplift and overlying strata erosion. However, systematic studies on their distribution patterns, multi-factor coupled genetic mechanisms, and evolutionary characteristics remain scarce [1]. For instance, underpressure is extensively developed in Mesozoic and Paleozoic low-permeability strata in the Central Continental and Great Plains regions of the United States, whose formation is closely related to regional tectonic uplift [2,3]. In the Jurassic-Triassic low-permeability reservoirs in the northern Norwegian Barents Sea, underpressure is induced by the combined effects of tectonic uplift and glacial unloading, making it a typical analog area for underpressure research in high-latitude regions worldwide [4]. Similarly, significant underpressure characteristics are observed in shallow low-permeability strata in the Huimin Sag of the Bohai Bay Basin and the central Sichuan Basin, China, where pore rebound and formation temperature reduction caused by tectonic uplift are the main genetic factors [5,6]. These global cases collectively reveal that the coupling effect of tectonic uplift and low-permeability media serves as the foundation for the formation of underpressure. Nevertheless, the differences in the genesis and evolutionary processes of underpressure under diverse geological backgrounds still require further clarification through targeted regional studies.

As one of China’s major petroleum-bearing basins, the Ordos Basin is endowed with abundant and diverse natural gas resources in the Upper Paleozoic strata, encompassing various types such as tight gas, shale gas, coalbed methane, limestone gas, and bauxite-associated gas [7,8]. As of the end of 2022, the cumulative proven natural gas reserves of the basin had reached 6.86 × 1012 m3 [9]. In recent years, significant progress has been achieved in the exploration of tight sandstone gas within the Shanxi Formation of the Upper Paleozoic strata and marine–continental transitional shale gas in the basin, highlighting substantial exploration potential [10,11,12]. Currently, the tight sandstone reservoirs in this stratigraphic interval generally exhibit abnormally low pressure; however, they typically developed abnormally high pressure during the late Early Cretaceous [13,14]. The formation process of this “paleo-overpressure–present-day underpressure” transition is crucial for the accumulation and preservation of natural gas.

For evaluation of the genetic mechanisms and evolutionary processes of ancient overpressure in the Ordos Basin, Han [14] investigated the genesis of ancient overpressure in the southeastern part of the basin using mudstone compaction curves and numerical simulations, suggesting that disequilibrium compaction and hydrocarbon generation-induced pressure buildup are the primary genetic mechanisms of ancient overpressure in this study area. Constrained by paleo-pressure data reconstructed from fluid inclusions and utilizing numerical simulation techniques via PetroMod software, Wang et al. [15] and Wang et al. [16] quantitatively restored and reconstructed the evolutionary history of ancient overpressure in the Upper Paleozoic strata of the Hangjinqi area. In terms of the genetic mechanisms and evolutionary processes of present-day underpressure in the Upper Paleozoic of the Ordos Basin, previous studies have suggested that the formation of such low pressure is closely associated with intense uplift and erosion since the Late Cretaceous, and that pore rebound and temperature decrease resulting from the uplift-erosion process are key factors contributing to the decline in formation pressure. In addition, gas diffusion through microfractures or fractures, as well as chemical reactions in formation water, also exert significant influences [17,18,19,20]. Guo et al. [21] and Wang et al. [16] integrated fluid inclusion data and applied numerical simulation techniques to reconstruct and analyze the pressure evolution process from paleo-overpressure to present-day underpressure or normal pressure for the Upper Paleozoic reservoirs in the Linxing area and the Lower Shihezi Formation reservoirs in the Hangjinqi area, respectively. However, these studies were mostly restricted to qualitative analysis and have not yet quantitatively evaluated the amount of formation pressure reduction caused by various influencing factors, as well as their contributions to pressure reduction. Wang et al. [15] and Jing et al. [19] employed a multi-method integrated approach to reconstruct reservoir paleo-pressure and quantitatively calculated the magnitude of pressure reduction and the percentage of pressure reduction contribution induced by temperature decrease, gas diffusion, and pore rebound. They concluded that these first two factors are the main contributors to the formation of underpressure in the Upper Paleozoic reservoirs of their respective study areas. In contrast, Kang et al. [20] conducted a quantitative analysis on the genetic mechanism and evolutionary process of underpressure in the Qian-5 Member of the Upper Paleozoic reservoirs in the Yulin-Shenmu area, pointing out that pore rebound and temperature decrease are the primary causes of the present-day development of underpressure in that area. In summary, the dominant controlling factors of abnormal low pressure in the Upper Paleozoic across different regions of the Ordos Basin exhibit significant differences, and a consistent understanding has not yet been formed. Furthermore, He et al. [22] and Lu et al. [23], in their research on the sealing capacity of mudstone caprocks in the Sichuan Basin, noted that during significant tectonic uplift of the strata, mudstone and shale layers exhibit enhanced brittle properties, rendering them highly prone to fracturing and subsequent pressure release. This process is particularly prominent in mudstone and shale formations with pre-existing overpressure. The burial history of the Ordos Basin is analogous to that of the Sichuan Basin; however, it remains unclear whether brittle fracturing and pressure release occurred in the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation mudstones and shales during late-stage intense uplift, and whether this process drove pressure increases in adjacent tight sandstones, thus limiting the understanding of their pressure evolution. Overall, previous studies on the evolutionary process of abnormal pressure in the Upper Paleozoic strata of the Ordos Basin still have limitations: first, most studies focus on a single stage of paleo-overpressure formation or present-day underpressure genesis, lacking systematic characterization and quantitative coupling evaluation of the complete evolutionary process from “paleo-overpressure––present-day underpressure”; second, the differences in the abnormal pressure evolutionary process under different source-reservoir assemblage types have not been addressed, and the contribution weights of various factors in pressure evolution lack precise quantification, making it difficult to reveal the intrinsic causes of regional pressure differences.

To address the aforementioned issues, this study takes the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the Yanchang area of the southeastern Yishan Slope, Ordos Basin as the case study and utilizes data from drilling, logging, well testing, as well as measured vitrinite reflectance (Ro) and temperature. A numerical simulation method accounting for hydrocarbon generation, disequilibrium compaction, and other pressurization effects was applied to reconstruct the paleo-overpressure evolution history of the target sandstone and shale layers prior to the end of the Early Cretaceous. On this basis, by calculating the formation pressure decrease induced by pore rebound, temperature reduction, and brittle fracturing with pressure release of overpressured shale during the tectonic uplift process since the Late Cretaceous, as well as the formation pressure increase in tight sandstones caused by overpressure transfer, the evolution process of abnormal pressure in the tight sandstones of the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation in the study area was clarified. The innovations of this study are as follows: ① establishing a quantitative evaluation framework for the complete evolutionary process of “paleo-overpressure—present-day underpressure”, which further improves the understanding of pressure evolutionary mechanisms; ② aiming at different source-reservoir assemblage types in the study area, precisely quantifying the contribution weights of various factors in pressure evolution, and systematically revealing the differences in their abnormal pressure evolutionary processes. This study enhances the in-depth understanding of the formation and evolution of underpressure in the Upper Paleozoic gas reservoirs of the Yanchang area, southeastern Ordos Basin, and provides guidance for natural gas exploration in this area.

2. Geological Settings

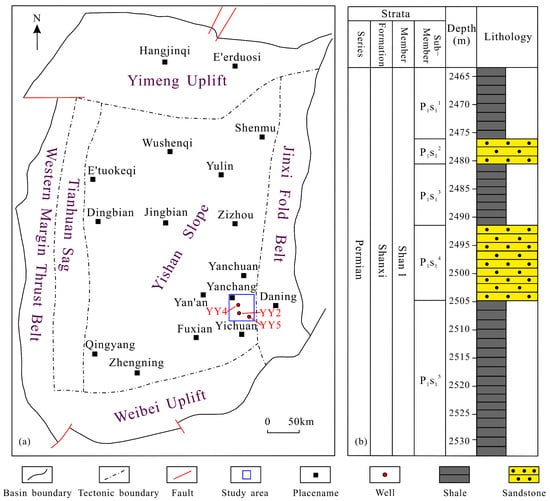

The Ordos Basin is situated on the western margin of the North China Craton (NCC), extending from the Yinshan and Daqingshan Mountains in the north to the Qinling Mountains in the south, the Helan and Liupan Mountains in the west, and the Luliang and Taihang Mountains in the east. Covering five provinces/municipalities, namely Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi, it has a total area of approximately 370,000 km2 and is recognized as one of the important large-scale sedimentary basins in northwestern China. As a typical polycyclic cratonic basin, it exhibits a complex tectonic evolutionary history and distinctive sedimentary filling characteristics [24,25,26,27]. The basin has experienced five phases of tectonic movements: the Caledonian, Hercynian, Indosinian, Yanshanian, and Himalayan orogenies, leading to the formation of an asymmetric large-scale north–south syncline. This syncline is characterized by a narrow and steep western limb and a broad and gentle eastern limb. Currently, faults and folds are well-developed in the peripheral areas of the basin, whereas its internal structure remains relatively stable [28,29,30]. Based on the structural morphology and characteristics of the basin, it can be further divided into six primary tectonic units (Figure 1a). Since the Mesozoic, the basin has undergone four phases of uplift and erosion. Following the Late Cretaceous, driven by the Yanshanian and Himalayan orogenies, the basin experienced intense erosion; the uplift and erosion processes persisted for 90–100 Myr, leading to the formation of the current structural framework characterized by westward thrusting and eastward uplift [31,32,33]. The study area is located in the Yanchang-Yichuan region, which is structurally situated in the southeastern part of the Yishan Slope (Figure 1a). The strata in this region are gentle, with a dip angle of less than 1°, exhibiting a westward-dipping monocline structure [34].

Figure 1.

(a) Tectonic units of the Ordos Basin and location of the study area [29]; (b) Lithological column of the Permian. Notes: YY2, YY4, and YY5 are the well locations selected for this study.

The oil and gas distribution in the Ordos Basin exhibits a typical “upper oil and lower gas” assemblage characteristic: the upper part of the basin features oil reservoirs developed in the Mesozoic strata, with the main oil-bearing sequences being the Jurassic and Triassic systems; the lower part hosts gas reservoirs developed in the Paleozoic strata, with the primary gas-bearing sequences including the Carboniferous-Permian systems of the Upper Paleozoic and the Ordovician system of the Lower Paleozoic; these oil and gas reservoirs collectively form a vertical composite oil-gas system [35,36]. Within the Ordos Basin, the Permian strata of the Upper Paleozoic are sequentially developed from bottom to top as the Taiyuan Formation, Shanxi Formation, Shihezi Formation, and Shiqianfeng Formation; among these four formations, the Shanxi Formation is the main gas-bearing stratum deposited during the Early Permian and serves as the target formation of this study [33]. During the depositional period of the Shanxi Formation, the southeastern Ordos Basin was in a marine–continental transitional depositional environment, developing a lacustrine-deltaic depositional system. The Shanxi Formation is divided into the Shan 1 Member and Shan 2 Member from top to bottom. Its lithology is dominated by organic-rich shale, sandstone, and coal seams [37,38,39,40]. The Shan 1 Member exhibits an interbedding pattern of “organic-rich shale-sandstone” (Figure 1b). The Shanxi Formation is characterized by self-generating, self-storing, and self-capping reservoir-forming conditions: the source rocks are shale and carbonaceous mudstone deposited in the delta front subfacies; the reservoirs are sandstones developed in the underwater distributary channel subfacies of the delta front within the same depositional system; and the cap rocks are shale deposited in the delta plain and lacustrine subfacies of the same depositional system. These three elements collectively form a complete source-reservoir-cap assemblage [33,40,41]. In the study area, the cumulative thickness of the shale in the Shan 1 Member ranges from 44.7 to 51.6 m (average: 48.2 m). The thickness of the sandstone in each sub-member varies from 3 to 13.4 m (average: 6.8 m). Among these lithologies, the organic matter type of the shale is dominated by Type III, with a total organic carbon (TOC) content ranging from 0.1% to 11.5% and primarily distributed between 1.3 and 2.9%. The Ro values of the shale range from 1.7% to 2.5%, indicating a high-to-overmature thermal maturity stage with gas generation as the main hydrocarbon generation process [42,43,44]. The reservoir sandstone in the Shan 1 Member has a porosity ranging from 0.51% to 10.37%, and its permeability ranges from 0.0019 to 75.8 × 10−3 μm2 (average: 0.37 × 10−3 μm2), exhibiting low-porosity and low-permeability characteristics [45].

3. Data and Methods

In this study, the origin of paleo-overpressure in the target layer of the study area was first identified using mudstone compaction curves and acoustic velocity–density cross plots. After clarifying its genetic mechanism, the paleo-pressure evolution history of the source rock interval was reconstructed based on measured data. During the Late Cretaceous tectonic uplift stage, the controlling factors and contribution ratios of pressure reduction for different source-reservoir assemblages were quantitatively evaluated, followed by a comprehensive analysis and inversion of the entire reservoir pressure evolution process. On this basis, the differences in pressure evolution among these assemblages were investigated, and combined with pressure evolution characteristics, their controlling effects on hydrocarbon accumulation and preservation were discussed.

3.1. Data

The data for this study were provided by Yanchang Petroleum (Group) Co., Ltd. (Xi’an, China), including well logging, mud logging, and drilling data from three wells in the study area, as well as measured formation temperature and Ro data. The well logging data include acoustic time difference (AC), density (DEN), and compensated neutron log (CNL) curves, which provide a basis for analyzing the genetic mechanism of paleo-overpressure in the target strata of the study area. The information on formation lithology (e.g., shale and sandstone) and burial depth recorded in the mud logging and drilling data sheets serves as a crucial foundation for reconstructing the burial history, thermal history, and paleo-overpressure evolution history of typical wells. Furthermore, the measured formation temperature and Ro data directly constrain the numerical simulation process, effectively ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the paleo-overpressure evolution history simulation results.

3.2. Numerical Simulation Method for Paleo-Overpressure Reconstruction

Numerical simulation of paleo-pressure utilizes pre-established mathematical-geological coupling models to quantitatively analyze the formation and evolution of overpressure in disequilibrium compaction strata. This method has been widely applied in the study of stratigraphic pressure evolution in various sedimentary basins [46,47]. In this study, the inverse backstripping method was employed to conduct burial history simulation for individual wells, while the reconstruction of the thermal maturity evolution history of source rocks was performed based on the Easy% Ro chemical kinetic model [48,49]. Additionally, considering the limitation of traditional basin simulation software (e.g., PetroMod and BasinMod) in inadequately accounting for hydrocarbon generation and pressurization effects during pressure evolution history reconstruction, this study, on the basis of completing the burial and thermal history reconstruction of target single wells, further applied the hydrocarbon generation and pressurization model proposed by Guo et al. [50,51] to quantitatively reconstruct the hydrocarbon generation and pressurization evolution history of the target strata during geological periods. The application of this method provides more accurate data and theoretical support for precisely simulating the hydrocarbon generation process in the study area and deeply analyzing the characteristics of pressure evolution.

The accuracy of numerical simulation heavily relies on the precise selection of key parameters, the reasonable design of geological models, and a comprehensive understanding of existing geological data. In this study, by integrating drilling, logging, mud logging, and rock cuttings data, we accurately acquired stratigraphic thickness and lithological information, determined the primary lithological composition of each stratum, and made reasonable settings using the software’s lithological mixing module. For the source rocks of the target stratum, pure lithologies were specified, with detailed settings provided in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mixed lithology settings and petrophysical properties of each layer in the study area.

The determination of stratigraphic deposition and erosion times primarily relies on the International Stratigraphic Chart (2021 Edition) [52] and the research findings of Chen et al. [53]. The erosion thickness of each target well during different periods is determined based on the research results of Chen et al. [31] (Table 2). Regarding parameter settings for hydrocarbon generation history simulation, the organic matter type is set to Type III, and the hydrogen index (HI) of kerogen is empirically assigned a value of 160 mg/g based on the research results of Guo et al. [54]. The TOC content is calculated using the ΔlgR method, with constraints from measured TOC data derived from well logging curves [55].

Table 2.

Formation denudation amounts of representative wells in Yanchang area, Ordos Basin.

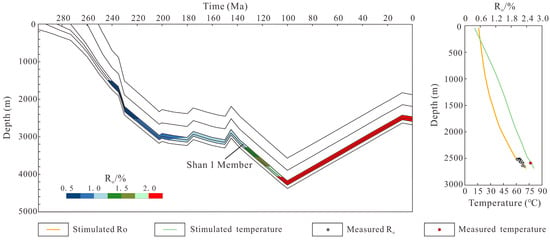

Furthermore, the selection of paleo-heat flow values is crucial for accurately reconstructing thermal history. The paleo-heat flow values for different periods in the study area were referenced from the research results of Yu [56] and Ren et al. [57]. By combining the measured formation temperature and Ro data from target wells in the study area, the heat flow parameters were repeatedly fine-tuned. Finally, the paleo-heat flow values for the Late Carboniferous–Permian period in the study area were determined to be 64–65 mW/m2, with the maximum value reaching 90–95 mW/m2 at the end of the Early Cretaceous. The present-day terrestrial heat flow value is 68 mW/m2, which ensures that the simulation results are consistent with the actual geological conditions.

3.3. Calculation Method for Formation Pressure Reduction

In areas experiencing significant tectonic uplift and erosion, the formation of abnormally low pressure during stratigraphic pressure evolution is often controlled by multiple factors [6,58,59]. Given the substantial uplift and erosion that occurred in the study area after the Late Cretaceous [32], a quantitative analysis and discussion were conducted on the formation of current abnormally low pressure in the target strata of the study area, based on pressure reduction mechanisms such as pore rebound, temperature decrease, and shale brittle fracture-induced pressure relief. The calculation methods for pressure reduction caused by different factors are as follows:

3.3.1. Calculation Method for Pressure Reduction Induced by Pore Rebound and Temperature Decrease

During tectonic uplift, porous rock systems undergo elastic rebound as erosion reduces the overlying load stress, resulting in a decrease in pore fluid pressure [60]. The pressure reduction in sandstone layers induced by pore rebound can be calculated using Formula (1) [20,61].

In the formula, ΔP represents the reservoir pressure change, with units of MPa; ν denotes Poisson’s ratio, assigned a value of 0.25; Cr signifies the rock matrix compressibility, taken as 1 × 10−3 MPa−1; Cw stands for the formation water compressibility, set to 3 × 10−4 MPa−1; ρr indicates the average density of the overlying strata; and g is the gravitational acceleration, taken as 9.8 m/s2; and ∆h represents the erosion thickness, with units of meters.

Meanwhile, existing research has confirmed that the compaction of shale exhibits an irreversible characteristic: Chang et al. [62] observed through laboratory creep experiments that no significant creep recovery occurred when shale samples were unloaded, with the strain recovery being nearly negligible. Furthermore, combined with Perzyna’s Viscoplasticity Theory and the modified Cam-clay model, their analysis revealed that the preconsolidation pressure of shale is permanently increased after unloading, and the pore structure undergoes irreversible compression—thus eliminating the possibility of pore rebound. Based on this, the pore rebound effect during the uplift stage is negligible and has therefore not been included in the quantitative analysis of this study [63].

Furthermore, Baker [64] argued that strata uplift not only induces pore rebound in rocks but also results in a decrease in formation temperature; this effect causes volumetric contraction of both the rock skeleton and pore-fluids (formation water). Typically, the contraction of pore-fluids in rocks is more pronounced than that of the rock skeleton, leading to a relative increase in rock pore volume during cooling and a subsequent decrease in formation pressure [60]. The pressure reduction in sandstone layers induced by temperature decrease can be calculated using Formulas (2)–(4) [20,61]. Based on previous studies, the average porosity of sandstone in the Shanxi Formation of the study area is adopted as 6.46% [45], and the temperature decrease during strata uplift is derived from numerical simulation results.

In the formula: ∆V represents the change in the unit volume of formation pore space, with units of m3; ∆T denotes the formation temperature change, with units of °C; βw is the formation water expansion coefficient, assigned a value of 400 × 10−6 °C−1; βr is the rock expansion coefficient, taken as 9 × 10−6 °C−1; φ signifies the reservoir porosity, with units of %; V0 is the initial pore fluid volume, with units of m3; V is the pore fluid volume after cooling, with units of m3; P0 is the formation pressure before cooling, with units of MPa; P is the formation pressure after cooling, with units of MPa; ∆P is the formation pressure change; and Cw is the pore fluid compressibility, adopted as the formation water compressibility 0.3 × 10−3 MPa−1.

This study employs numerical simulation techniques to obtain the formation pressure of shale layers during the maximum burial depth period. Wang et al. [15] proposed the following assumption: when pressure remains constant, a decrease in temperature leads to a corresponding reduction in the molar volume of gas. However, since the pore volume remains unchanged, this transformation process is equivalent to a pressure reduction effect caused by the relative increase in gas accommodating space under isothermal conditions. The magnitude of this pressure reduction can be calculated using Equations (5)–(7).

In the formula, Vm represents the molar volume of gas; R denotes the gas constant, typically assigned a value of 8.314 J·mol−1·K−1; and a and b are van der Waals constants, whose values depend on the gas type. Analysis of (Table 3) indicates that different gas mixture types within the study area exert a limited influence on the values of parameters a and b, and these two constants mainly affect the variation in gas molar volume before and after temperature reduction. In addition, according to the research methodology proposed by Wang et al. [15], the values of a and b have no influence on the calculated pressure magnitude. Furthermore, referring to the statistical results of natural gas compositions in the Upper Paleozoic gas reservoirs of the Yanchang Gas Field reported by Liu [65], the average methane content in the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation is 95.63%. Based on this finding, the values of a and b adopted in this study are 22.83 × 10−2 Pa·m3·mol−1 and 42.78 × 10−6 m3·mol−1, respectively. P1 is the shale formation pressure at maximum burial depth, with units of MPa; P2 is the shale formation pressure after cooling, with units of MPa; and ∆P is the formation pressure change before and after cooling, with units of MPa.

Table 3.

Calculated a and b values in various scenarios vs. deviations relative to pure methane benchmarks.

3.3.2. Calculation Method for Pressure Reduction Induced by Brittle Fracturing of Shale

Brittleness is a key manifestation of shale mechanical properties, typically characterized by high brittle mineral content and low plastic mineral content [66]. Notably, shale brittleness exerts a significant controlling effect on natural fracture formation. Brittle minerals play a crucial role in inducing rock fracturing and forming complex fracture networks, indicating that higher shale brittleness facilitates fracture initiation and propagation [67,68,69]. Early studies proposed that fracture systems further develop during strata uplift accompanied by overlying strata erosion [70]. This perspective has been increasingly accepted and applied in practical research. Strata uplift and erosion can convert shale into an overconsolidated state, altering rock mechanical properties and manifesting as enhanced brittleness [67]. For overpressured shale formations that have experienced significant uplift, increased brittleness renders them highly susceptible to brittle fracturing. This, in turn, results in hydrocarbon leakage, formation pressure release, and ultimately formation pressure reduction [22,71].

The overconsolidation ratio (OCR) is a key parameter for evaluating the consolidation state of clays. Low OCR values are associated with plasticity, whereas high OCR values correlate with brittleness. Nygård et al. [67] utilized the overconsolidation ratio (OCR) to quantify the brittleness of shales and mudrocks. They conducted consolidated undrained (CU) triaxial compression tests and systematically analyzed triaxial test data from 40 different types of shales and mudrocks collected from the North Sea region, thereby comprehensively investigating the correlation between OCR and brittle fracture of shales and mudrocks. This study provides robust support for the applicability of OCR as a criterion for assessing brittle fracture in shales and mudrocks. Furthermore, a power function relationship between the normalized undrained shear strength and OCR was established, which was quantitatively verified using the Brittleness Index (BRI): when BRI > 2, the corresponding critical OCR value is 2.5, above which shales and mudrocks are prone to brittle fracture; when OCR reaches 2.6, shales and mudrocks exhibit complete brittleness and are thus more susceptible to brittle fracturing [72]. This conclusion further confirms the applicability of OCR in evaluating brittle fracture of shales and mudrocks under tectonic uplift settings. Generally, an OCR of 1 indicates normally consolidated shale (i.e., the current effective vertical stress in the shale formation is equal to or greater than the maximum effective vertical stress experienced at any point in geological history); an OCR greater than 1 denotes overconsolidated shale (referring to shale formations that have attained maximum burial depth and been unloaded to the current in situ effective vertical stress due to significant uplift). Given that temperature decrease is the most quantifiable factor during shale formation uplift and exerts a distinct impact on formation pressure, this study assumes that the Shanxi Formation shale formations are solely governed by the pressure reduction effect induced by temperature decrease during the uplift stage. The formation pressure data retrieved via numerical simulation will be converted to obtain the effective vertical stress during key geological periods from the Late Cretaceous to the present, considering only the temperature-driven pressure reduction mechanism. OCR values for each period during the late stage of strata uplift will be calculated using Formula (8), and the specific timing at which shales attain the brittle fracturing threshold (OCR = 2.6) and satisfy the brittle fracturing criteria will be further derived.

In the formula, OCR denotes the overconsolidation ratio of shale, which is a dimensionless parameter; σvmax represents the maximum vertical effective stress experienced by the stratum during its geological history, with the unit of MPa; and σv refers to the vertical effective stress of the stratum during a certain period of its later uplift process. Specifically, in this study, it denotes the vertical effective stress of the stratum corresponding to the OCR reaching the fracture threshold of 2.6, with the unit of MPa.

The study area is located in the southeastern part of the basin and has experienced intense tectonic uplift and erosion since the maximum burial depth period, with erosion thickness ranging from 1600 to 1800 m [31]. Tectonic uplift after the Late Cretaceous transformed the plastic state of the Shanxi Formation shale strata (from the maximum burial depth period) into a brittle state. During continuous uplift, the brittle shale strata are prone to fracturing and pressure relief, resulting in a decrease in formation pressure [23]. In the Shanxi Formation shale of the study area, quartz (a brittle mineral) content ranges from 10.0% to 66.0%, with an average of 37.0%. The overall average content of brittle minerals (quartz + feldspar + pyrite) is 43% [44]. The average brittleness index (BI) of the Shanxi Formation shale in this area, derived from the combination of the elastic modulus method and logging parameter interpretation, is 47.5%, indicating a certain degree of brittleness during geological history. Xiong et al. [73] further confirmed, through uniaxial compression tests, that the shale of the Shanxi Formation in the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin exhibits distinct brittle characteristics. Meanwhile, previous observations via field outcrops, core samples, and microscopic analysis have revealed that the Shanxi Formation shale in the study area is relatively rich in both macroscopic and microscopic fractures. Macroscopic fractures are dominated by vertical fractures, with some shear fractures also developed in the cores. Microscopic fractures are extensively developed under microscopic observation [74,75]. Furthermore, in the Dingshan area of the southeastern Sichuan Basin, which shares a similar tectonic uplift background (continuous uplift from 82 to 0 Ma), Fan et al. [76] determined the main fracture formation period in this area as the middle-late Yanshanian period (82–71.1 Ma) to the late Yanshanian–mid-Himalayan period (71.1–22.3 Ma) through outcrop and core observations, rock acoustic emission experiments, apatite fission track analysis, combined with fracture-filled inclusion homogenization temperatures and thermal burial history. This indicates that the tectonic uplift process promotes fracture development. Gao et al. [77] studied the Middle Permian Maokou Formation in the southern Sichuan region and pointed out that the area underwent significant uplift and developed numerous fractures under the influence of the Himalayan tectonic movement. These fractures promoted the adjustment of the Maokou Formation gas reservoir: the fifth reservoir formation stage corresponds to the adjustment and stabilization period from the Late Cretaceous to the present, with gaseous hydrocarbons charged after the Late Cretaceous and a reservoir formation time span of 45–23.5 Ma. This further confirms that fractures generated by late-stage tectonic uplift play a crucial role in shaping the current gas reservoir distribution pattern. The aforementioned research further provides evidence for the brittle fracturing of the Shanxi Formation shale during the tectonic uplift of the Ordos Basin. Comprehensive analysis indicates that the shale layer in the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the study area transitions to a highly brittle state and undergoes fracturing-induced pressure relief during uplift, resulting in a rapid decrease in formation pressure to hydrostatic pressure. Assuming this pressure reduction process lasted for 5 Ma, the magnitude of brittle fracturing-induced pressure relief in the shale formation was calculated.

3.4. Calculation Method for Formation Pressure Increment in Sandstone Induced by Overpressure Transmission

Overpressure transmission refers to the flow of overpressured fluid released or leaked from an overpressure system, which induces an increase in pore fluid pressure in other pressure systems. Its transmission mechanisms include overpressured fluid charging, migration along permeable sand bodies, and expansion of overpressure compartments [78]. Drawing on previous research, the overpressure transmission effect in the study area is primarily controlled by hydrocarbon fluid charging during the Late Triassic to Early Cretaceous and brittle fracturing-induced pressure relief of overpressured shale, which was induced by tectonic uplift since the early Late Cretaceous. On the one hand, overpressure in the Shan 1 Member shale of the study area was generated by hydrocarbon generation expansion, disequilibrium compaction, and other factors during the Late Triassic to Early Cretaceous. Driven by the excess pressure difference between the source rock and reservoir, overpressured hydrocarbon fluids migrated along fractures to adjacent sandstones, resulting in an increase in internal fluid pressure [19]. On the other hand, intense tectonic uplift since the early Late Cretaceous caused brittle fracturing of the Shan 1 Member shale in the study area, developing numerous fractures. Driven by the high excess pressure difference between the shale and adjacent sandstones, overpressured fluids in the Shan 1 Member shale migrated along the newly formed fractures to adjacent sandstones, facilitating an increase in sandstone reservoir pressure [59].

The calculation method for fluid pressure increment induced by overpressure transmission in the target reservoir of the study area is as follows: Firstly, the formation pressure of the target sandstone reservoir at the end of the Early Cretaceous is obtained based on the aforementioned overpressure numerical simulation. Secondly, the current formation pressure of the target sandstone reservoir is derived through quantitative calculations of pore rebound caused by tectonic uplift and pressure reduction induced by temperature decrease since the early Late Cretaceous. Thirdly, the current measured formation pressure is subtracted from the formation pressure of the sandstone reservoir obtained in the previous step, and the difference is regarded as the total overpressure transmission-induced increment in the target reservoir of the study area. Finally, considering the main controlling factors of overpressure transmission, a physics-based dual-factor quantitative model of “source-reservoir excess pressure difference-fracture openness” is established to realize the reasonable allocation of overpressure transmission-induced pressurization magnitude in each period: Based on previous research [79] on hydrocarbon charging periods, it is confirmed that there are three phases of hydrocarbon charging in the study area, and the source-reservoir excess pressure differences during each charging phase are calculated as 4.96–6.17 MPa, 12.23–21.26 MPa, and 14.27–31.50 MPa, respectively; combined with the characteristics of regional fault activities, the northeast-trending faults in the Upper Paleozoic of the study area were activated during the mid-to-late Yanshanian Movement and Himalayan Movement, and their activation timing matches the hydrocarbon accumulation periods of the Late Triassic–Early–Middle Jurassic, Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous, and the tectonic uplift stage, providing effective pathways for hydrocarbon migration [80]. The fracture openness in each period is quantified by parameters such as fault activity intensity. In this study, a normalization method is adopted to construct the allocation formula of overpressure transmission-induced pressurization magnitude for each charging phase, and the formation pressure increment in sandstone caused by overpressure transmission in each phase is calculated via Equation (9).

In the formula, Qi is the overpressure transmission-induced pressurization magnitude in the i-th phase; Qtotal is the total pressurization magnitude; ∆Pi is the average source-reservoir excess pressure difference in the i-th phase; and Fi is the quantitative coefficient of fracture openness in the i-th phase.

4. Results

4.1. Current Reservoir Pressure Distribution Characteristics

Accurate acquisition of reservoir pressure is a critical foundation for hydrocarbon reservoir evaluation and development strategy optimization [81]. Based on the statistical analysis of previous measured reservoir pressure data in the Upper Paleozoic of the southeastern basin, the current pressure coefficient (defined as the ratio of formation pressure to hydrostatic pressure) of tight sandstone reservoirs in the Shanxi Formation, southeastern Yishan Slope of the Ordos Basin, ranges from 0.75 to 1.10, with an average of 0.92, thus exhibiting overall subnormal pressure or normal pressure characteristics [36,82]. Given the lack of measured pressure data in this study, we further refer to the gas testing statistical results of 324 intervals in the Yanchang Gas Field reported by Liu [65], and determine that the current average pressure coefficients of tight sandstone reservoirs in the Shan 1 Member and Shan 2 Member of the study area are 0.823 and 0.898, respectively, both of which fall into the underpressure category. According to the formation pressure classification scheme for the basin proposed by Li [83] and Qin et al. [36], the current formation pressure of the target reservoirs in the study area is in a subnormal pressure state.

4.2. Genesis of Formation Paleo-Overpressure

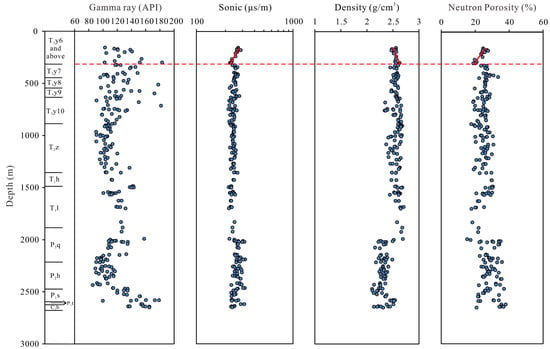

Based on the geological conditions of the study area, the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation is characterized by a low sandstone ratio—defined as the ratio of sandstone thickness to total formation thickness—with the value ranging from 17.4% to 25.8%, and a substantial cumulative thickness of shale. The rapid deposition from the Late Jurassic to the end of the Early Cretaceous created favorable conditions for the development of disequilibrium compaction overpressure in the shale formations. The comprehensive compaction curve of shale in the study area (Figure 2) indicates that, in the strata above the Chang 6 oil reservoir of the Yanchang Formation, the acoustic travel time and neutron porosity of shale decrease while density increases with increasing burial depth, exhibiting characteristics of a normal compaction trend. In contrast, in the strata from the top of the Chang 7 oil reservoir downward, the variations in acoustic travel time, density, and neutron porosity of most shale deviate from the normal compaction trend to varying degrees. Specifically, with increasing burial depth, these parameters show significantly abnormal acoustic travel time, reduced density, and abnormally high neutron porosity. Such deviations are particularly pronounced in the shale of the Shihezi Formation, Shanxi Formation, and Taiyuan Formation, indicating that disequilibrium compaction is widespread in the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation of the Yanchang area. Drawing on the research results of Chen et al. [31], the Yanchang area generally reached its maximum burial depth by the end of the Early Cretaceous. Therefore, the disequilibrium compaction-induced pressure buildup of the Shanxi Formation shale in this area should have peaked by the end of the Early Cretaceous.

Figure 2.

Comprehensive compaction characteristics of shales in typical wells of Yanchang area. Notes: The red dashed line represents the top of overpressure, and its upper part corresponds to the normal compaction interval. The red solid line reflects the variation trends of acoustic time difference, density, and neutron porosity with depth within the normal compaction interval. The arrows indicate the position of the Taiyuan Formation.

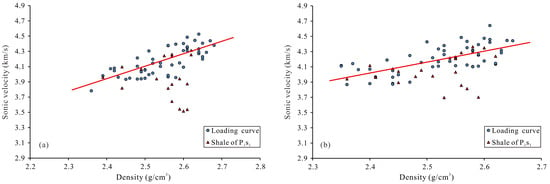

The typical well acoustic velocity–density crossplot (Figure 3) indicates that some data points in the shale interval of the Shanxi Formation deviate from the normal compaction trend, exhibiting reduced acoustic velocity and unchanged or slightly decreased density—this phenomenon suggests hydrocarbon generation-induced pressurization. Another set of data points lies on the loading curve; this is inferred to be potentially associated with the dissipation of hydrocarbon generation-induced pressurization caused by tectonic uplift after the Late Cretaceous. In addition, the TOC content of organic-rich shale in the study area is generally high, primarily ranging from 1.3% to 2.9%. Furthermore, the Ro in some areas reached over 2.0% by the end of the Early Cretaceous, indicating high thermal evolution degree and significant hydrocarbon generation potential [42]. Using numerical simulation technology, this study reconstructed the excess pressure generated by hydrocarbon generation in the target shale layer of the study area at the end of the Early Cretaceous, which ranged from 13.97 to 16.04 MPa. This further confirms that hydrocarbon generation is also a key factor in the formation of paleo-overpressure in the Shanxi Formation shale strata of this area. Based on the shale compaction curve, acoustic velocity–density crossplot, and regional geological characteristics, it can be concluded that the main controlling factors for paleo-overpressure formation during the maximum burial depth period of the Shan 1 Member shale in the Shanxi Formation are disequilibrium compaction and hydrocarbon generation.

Figure 3.

Crossplot of acoustic velocity and density of typical wells in Yanchang area. (a) Well YY4; (b) Well YY5. Notes: The red solid line represents the curve obtained by linearly fitting the data of the normal compaction interval.

4.3. Simulation Results of Paleo-Overpressure in the Target Strata of a Single Well

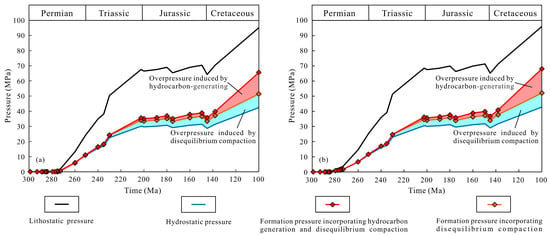

This study selected two wells, YY2 and YY5, in the research area. Based on the rational selection of parameters, simulations of the single-well burial history, thermal history, and hydrocarbon generation history were conducted to reconstruct the overpressure evolution history during their respective geological periods. Meanwhile, the simulated thermal history results of Well YY2 are in good agreement with the measured values—this indicates that the selected parameters can effectively construct the simulation model, thereby ensuring the rationality and reliability of the numerical simulation results (Figure 4). From the thermal history simulation results of Well YY2 (Figure 4), it can be observed that approximately 230 Ma ago, the Ro of the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation reached 0.6%—marking the onset of the hydrocarbon generation threshold. During this period, disequilibrium compaction and hydrocarbon generation began to intensify, with an initially slow rate of increase. At 202.5 Ma, the excess pressure values generated by hydrocarbon generation and disequilibrium compaction in the P1s13 sub-member source rocks were 1.37 MPa and 4.05 MPa, respectively. For the P1s15 sub-member source rocks, the excess pressure values derived from hydrocarbon generation and disequilibrium compaction were 1.60 MPa and 4.09 MPa, respectively. Subsequently, the strata in this area underwent multiple episodes of subsidence and uplift-erosion. By 100 Ma, the strata reached its maximum burial depth, with the Ro of the Shan 1 Member exceeding 2.0%—marking the entry into the peak period of hydrocarbon generation. During this period, the strata pressure reached its peak: the excess pressure due to hydrocarbon generation and disequilibrium compaction in the P1s13 sub-member source rocks reached 13.97 MPa and 9.21 MPa, respectively, while for the P1s15 sub-member source rocks, the corresponding excess pressure values increased to 16.04 MPa and 9.27 MPa, respectively (Table 4, Figure 5). The continuous uplift of the strata since the Late Cretaceous led to a decrease in strata temperature and pressure, thereby terminating hydrocarbon generation.

Figure 4.

Burial and thermal history simulation results of the Shanxi Formation in Well YY2, Yanchang area, Ordos Basin.

Table 4.

Pressure increases and their proportions induced by disequilibrium compaction and hydrocarbon generation during the maximum burial depth period for the shales of each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member in typical wells of the Yanchang area.

Figure 5.

Paleo-overpressure evolution history of shale formations in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member, Well YY2, Yanchang area (before the end of the Early Cretaceous). (a) Shale of the P1s13 sub-member; (b) Shale of the P1s15 sub-member.

4.4. Calculation Results of Pressure Reduction Induced by Pore Rebound and Temperature Decrease

The preceding analysis indicates that the pressure decline in the sandstone of the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the study area is associated with pore rebound and temperature reduction, while the pressure decline in the shale is related to temperature reduction—with the pressure reduction induced by pore rebound in the shale being negligible. Based on this, the pressure reduction magnitudes of sandstone and shale in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member for individual wells in the study area were calculated. The results show that from the strata’s maximum burial depth to the present (100–0 Ma), the pore rebound-induced pressure reduction in the sandstone of each Shan 1 Member sub-member ranges from 16.93 to 17.41 MPa, with an average of 17.17 MPa. In contrast, the temperature reduction-induced pressure reduction ranges from 12.07 to 13.85 MPa, with an average of 12.96 MPa (Table 5). For the shale of/in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member, the temperature reduction-induced pressure reduction ranges from 12.95 to 17.75 MPa, with an average of 15.35 MPa (Table 6).

Table 5.

Pressure reductions and their proportions induced by temperature decrease and pore rebound in sandstones of each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member in typical wells of the Yanchang Area.

Table 6.

Pressure reduction caused by temperature decrease in shales of each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member in typical wells of the Yanchang Area.

4.5. Calculation Results of Pressure Reduction Induced by Brittle Fracture of Shale

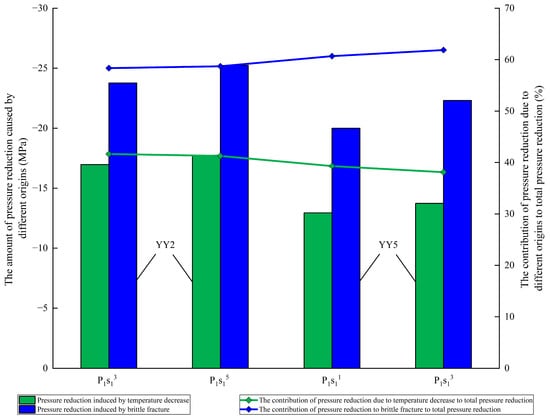

According to the data in Table 6, when only considering the pressure reduction mechanism induced by temperature decrease, the calculated pressure coefficients of the shale in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation exceed 1.9; this differs significantly from the actual drilling fluid density range of 1.01–1.22 used in drilling operations. This indicates that, in addition to the temperature-induced pressure reduction mechanism, other pressure reduction mechanisms exist, which have reduced the current formation pressure of the target shale layer to near-normal pressure. Combined with the preceding analysis, the shale layers transitioned from a ductile to a strongly brittle state during the Paleogene–Neogene period, undergoing brittle fracture and pressure relief, which led to a decrease in formation pressure. When only considering the temperature-induced pressure reduction mechanism, the calculated time for each shale layer to reach the brittle fracture threshold ranges from 26.18 to 38.67 Ma, with a corresponding brittle fracture pressure relief magnitude of 20.00–25.24 MPa (Table 7). The current distribution range of the shale formation pressure coefficients is 1.00–1.06, generally exhibiting a normal pressure formation, with weak overpressure developing in some areas. Quantitative analysis shows that temperature decrease and brittle fracture pressure relief are the main controlling factors for the formation of normal pressure (weak overpressure) in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member shale formation. Among the total formation pressure decrease, the contribution from temperature decrease accounts for 38.11–41.65%, while the contribution from brittle fracture pressure relief accounts for 58.35–61.89% (Figure 6).

Table 7.

Statistics of the time when the OCR reaches the fracture threshold and the fracture pressure relief volume of the shale layers in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member from typical wells in the Yanchang Area.

Figure 6.

Histogram of pressure reduction composition during the tectonic uplift process of shale in different sub-members of the Shan 1 Member from typical wells in the Yanchang Area.

Meanwhile, an error analysis was conducted on the selection of the shale brittle fracture threshold (OCR value) to verify the reliability of the research results (Table 8). In the analysis process, OCR = 2.6 was selected as the benchmark value to systematically explore the influence of different OCR values on the calculation results of pressure reduction caused by brittle fracture of shale layers (i.e., brittle fracture pressure relief volume): when the OCR value is lower than the benchmark value, the calculation results show that the corresponding brittle fracture pressure relief volume is slightly lower than that calculated with the benchmark value (OCR = 2.6), and the absolute value of the error is less than 0.5%; when the OCR value is higher than the benchmark value, scenarios where the OCR is 5% (OCR = 2.73) and 10% (OCR = 2.86) higher than the benchmark value were calculated, respectively. The results indicate that although the brittle fracture pressure relief volume of shale layers calculated under such circumstances fluctuates slightly below or above the result of the benchmark value, the absolute value of the overall error is controlled within 1.1%. Overall, the influence of different OCR values on the calculation results of brittle fracture pressure relief volume is limited, which further confirms the accuracy and stability of the research results.

Table 8.

Analysis of the effect of different OCR values on pressure relief volume from brittle fracturing of shale layers.

5. Discussion

5.1. Impact of Hydrocarbon Charging and Shale Brittle Fracture Pressure Relief on the Sandstone Strata Pressure of the Shanxi Formation in the Study Area

The evolution of sandstone formation pressure in the Shanxi Formation of the study area is influenced by multiple factors. When only considering the two depressurization mechanisms of temperature decrease and pore rebound, the calculated formation pressure coefficient ranges from 0.48 to 0.49—this is significantly lower than the average reservoir pressure coefficient of 0.823 in the Shan 1 Member of the area. This indicates the existence of other pressurization mechanisms during reservoir pressure evolution. It is analyzed that hydrocarbon charging and shale brittle fracture pressure relief are key factors contributing to the increase in sandstone formation pressure in the target strata of the study area. Both factors affect changes in sandstone formation pressure through overpressure transmission.

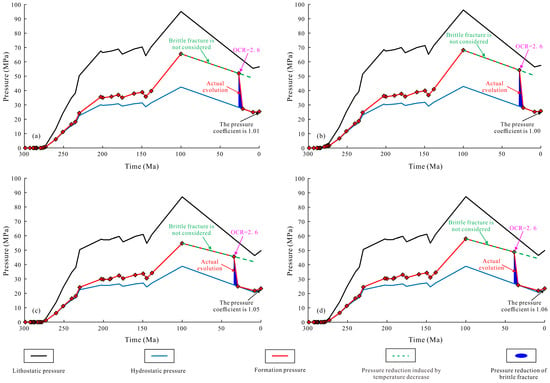

Guo et al. [79] pointed out that the reservoirs in the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation experienced two periods of hydrocarbon charging, with reservoir formation times of 220–170 Ma and 160–100 Ma, respectively. Combined with the thermal history characteristics of Well YY2: during the first hydrocarbon charging period, the source rocks had just entered the hydrocarbon generation threshold, with slow hydrocarbon generation and weak charging intensity. Through overpressure transmission, this resulted in an increase of 0.88–1.03 MPa in sandstone formation pressure. During the second hydrocarbon charging period, the source rocks exhibited high thermal maturity and large-scale hydrocarbon generation—this was the main charging period, corresponding to a sandstone formation pressure increment of 2.71–3.17 MPa. These two charging periods jointly dominated the pressure rise process of the sandstone formations at the end of the Early Cretaceous. In addition, the pressure evolution of the shale formations in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member in the study area exhibits distinct stage-specific characteristics, which further affect pressure changes in the sandstone reservoirs through overpressure transmission. This evolution presents a transition process from ultra-high pressure to normal pressure (weak overpressure), which can be divided into three stages: (1) Prior to the end of the Early Cretaceous, the shale formations developed excess pressure due to disequilibrium compaction and hydrocarbon generation. The formation pressure reached its maximum at 100 Ma, with a pressure coefficient ranging from 1.41 to 1.59 (generally exceeding 1.4), indicating the development of overpressure in the strata; (2) During the initial stage of tectonic uplift since the Late Cretaceous, the decrease in temperature led to a corresponding reduction in shale formation pressure, which continued until the shale reached the brittle fracture threshold; (3) When the shale underwent brittle fracture, the overpressure hydrocarbons and fluids accumulated in the early stage migrated rapidly to adjacent reservoirs under a source-reservoir excess pressure difference of 12.23–21.26 MPa, causing the formation pressure to drop sharply to hydrostatic pressure. During this process, the hydrocarbon charging became the driver for the increase in sandstone reservoir pressure, with a pressure increment of 3.73–4.38 MPa. Subsequently, under the overlying load, the fractures gradually closed as overpressure dissipated, reforming a sealed space. At this stage, although the internal pressure continued to decrease due to temperature decline, the formation pressure remained higher than hydrostatic pressure. Currently, the shale formations as a whole exhibit near-normal pressure characteristics (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Diagram of the entire process of formation pressure evolution of shale in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member from typical wells in the Yanchang Area. (a) Shale of the P1s13 sub-member in Well YY2; (b) Shale of the P1s15 sub-member in Well YY2; (c) Shale of the P1s11 sub-member in Well YY5; (d) Shale of the P1s13 sub-member in Well YY5.

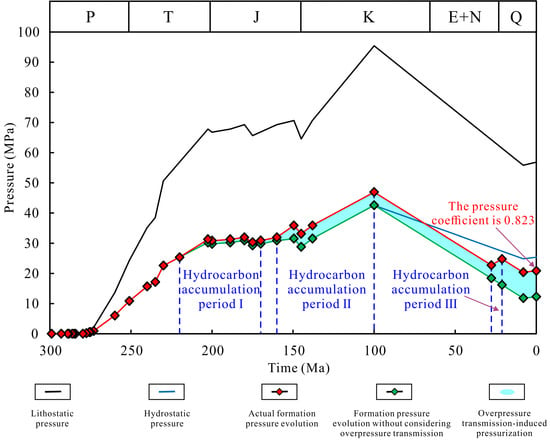

Based on the aforementioned analysis and in conjunction with the pressure evolution process of shale formations, it is evident that overpressure transmission acts as a crucial pressurization mechanism for sandstone formations. The total increase in fluid pressure in the reservoirs induced by overpressure transmission ranges from 7.32 to 8.58 MPa. This insight provides support for revealing the pressure evolution patterns of sandstone formations, thereby facilitating the comprehensive reconstruction of the entire pressure evolution process (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Diagram of the formation pressure evolution process of the P1s14 sub-member sandstone in Well YY2 of the Yanchang Area. Notes: P = Permian, T = Triassic, J = Jurassic, K = Cretaceous, E = Paleogene, N = Neogene, Q = Quaternary.

5.2. Evolution Process of Formation Pressure in the Sandstone of the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation, Study Area

The formation pressure of the Shan 1 Member sandstone in the study area has undergone an evolutionary process from abnormal high pressure to abnormal low pressure, showing a two-stage characteristic of “first increasing and then decreasing” (Figure 8).

Prior to the end of the Early Cretaceous, the sandstone formation underwent an evolution from normal pressure to overpressure. During this period, the Shan 1 Member sandstone experienced two phases of hydrocarbon charging, and the formation pressure increased by 0.88–1.03 MPa and 2.71–3.17 MPa, respectively, induced by overpressure transmission. By the period of maximum burial depth, the formation pressure reached its peak, with a pressure coefficient of 1.10, exhibiting overpressure characteristics. This result is consistent with the research findings of Li et al. [84]. They employed fluid inclusion analysis to conduct paleopressure reconstruction on the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation reservoirs in the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin, obtaining an average trapping pressure coefficient of 1.16, which is numerically close to the paleopressure coefficient obtained in this study. The paleopressure data derived from fluid inclusions provides data constraints for the sandstone formation pressure evolution model established in this paper, further verifying the rationality and reliability of the research results.

From the Late Cretaceous to the present, the sandstone formation has transitioned from overpressure to underpressure. Basin tectonic uplift has become a key triggering factor for pressure evolution, leading to a continuous decrease in sandstone formation pressure: Tectonic uplift induced a decrease in formation temperature, which in turn led to a formation pressure drop of 12.07–13.85 MPa, accounting for 40.94–45.00% of the total pressure reduction; meanwhile, after strata unloading, pore elastic rebound occurs, and pore spaces expand relatively, leading to a formation pressure decrease of 16.93–17.41 MPa, accounting for 55.00–59.06% of the total pressure reduction; additionally, hydrocarbon charging that still occurs during the tectonic uplift period forms a pressure compensation of 3.73–4.38 MPa through overpressure transmission. This partially offsets the pressure reduction effect but does not alter the overall trend, ultimately resulting in the current underpressure state of the sandstone strata. This pressure evolution process is the result of the synergistic effects of overpressure transmission, temperature reduction, and pore rebound.

5.3. Impact of the Evolution of Pressure Differences in Different Lithologic Strata of the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation in the Study Area on Natural Gas Accumulation

The study by Qin et al. [85] revealed that the sandstone reservoir in the Shan 1 Member is characterized by low porosity, low permeability, and strong heterogeneity, and is classified as a tight sandstone reservoir. In the study area, the sandstone types in the Shan 1 Member of the formation are primarily lithic quartz sandstone and lithic sandstone. The pore evolution processes of different types of sandstone vary: during the first hydrocarbon charging phase (Late Triassic–Early–Middle Jurassic), the porosity of both types of sandstone reservoirs did not reach the tightness threshold of 10%. After entering the second hydrocarbon charging phase (Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous), lithic quartz sandstone exhibited a characteristic of “forming reservoirs while becoming tight,” with its porosity decreasing to 7.4–11.1% at the end of the charging stage. Meanwhile, the porosity of lithic sandstone had already decreased to 2.9–10.1% before the second hydrocarbon charging phase. The tightening of the reservoir made it difficult for hydrocarbons to charge into the reservoir via buoyancy alone [79].

Furthermore, the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the study area exhibits a “shale-sandstone-shale” lithological combination, where notable differences exist in the pressure evolution processes between organic-rich shale and sandstone reservoirs. Based on the preceding analysis, it can be concluded that there are three phases of hydrocarbon charging in the Shan 1 Member sandstone of the Shanxi Formation in the study area. The following section will specifically analyze the impact of pressure differential evolution in different lithological strata on natural gas accumulation during different charging phases:

During the first phase of hydrocarbon charging from the Late Triassic to the Early-Middle Jurassic (220–170 Ma), neither lithic quartz sandstone nor lithic sandstone reservoirs had undergone densification, maintaining favorable porosity and permeability. At this stage, the source rocks had just entered the hydrocarbon generation threshold with relatively weak hydrocarbon generation capacity, and could only generate relatively low overpressure through limited hydrocarbon generation and disequilibrium compaction. The uncompacted pore systems of these two sandstone types provided effective pathways for hydrocarbon migration, enabling hydrocarbons to charge into the reservoirs under the combined action of buoyancy and an excess pressure difference of 4.96–6.17 MPa between the source and reservoir. However, due to the insufficient hydrocarbon generation intensity of the source rocks, only small-scale gas reservoirs were formed, and the differences in natural gas accumulation between these two sandstone types were not significant.

During the second phase of hydrocarbon charging from the Late Jurassic to the end of the Early Cretaceous (160–100 Ma), the densification intensity of the two sandstone reservoir types increased, and the porosity and permeability of the reservoirs generally decreased. The excess pressure difference between the source and reservoir became the main driving force for hydrocarbon charging. Among them, the lithic sandstone had already undergone significant densification prior to this hydrocarbon charging phase, with its porosity decreasing to 2.9–10.1%. Reservoir densification increased the resistance to hydrocarbon migration, and effective hydrocarbon charging was difficult to achieve in the absence of sufficient driving force. In contrast, although the lithic quartz sandstone exhibited the characteristic of “reservoir formation during densification” (with porosity decreasing to 7.4–11.1% at the end of charging), it still had to overcome the resistance caused by the continuous reduction in porosity during the charging process. At this stage (100 Ma ago), due to continuous hydrocarbon generation and intense disequilibrium compaction, the formation pressure of the shale in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member reached a peak, forming an excess pressure difference of 12.23–21.26 MPa between the source and reservoir. This high source-reservoir excess pressure difference serves as a key driving force to overcome the migration resistance of the two sandstone types, especially those that have undergone significant densification: For lithic quartz sandstones that were not fully densified during the charging process, the high source-reservoir excess pressure difference drives continuous hydrocarbon charging, which is accompanied by reservoir densification, ultimately leading to large-scale natural gas accumulation; for lithic sandstones that had been densified prior to the charging process, only limited hydrocarbon charging can occur through partially open fractures or residual pores under the action of the high source-reservoir excess pressure difference. The increased migration resistance caused by reservoir densification not only highlights the dominant role of the source-reservoir excess pressure difference in hydrocarbon charging at this stage, but also determines the differences in accumulation scales among sandstone reservoirs of different lithologies.

The tectonic uplift period after the Late Cretaceous is a crucial stage for the adjustment and finalization of the gas reservoir distribution pattern in the study area. At this stage, the two sandstone types had been fully densified, and the source-reservoir excess pressure difference became the core driving force for hydrocarbon charging. With the uplift of the overlying strata, the shale in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member underwent brittle fracturing as its OCR increased to the fracture threshold, and the source-reservoir excess pressure difference further increased to 14.27–31.50 MPa. Driven by this high source-reservoir pressure difference, hydrocarbons within the shale migrated rapidly along the newly formed fractures to the adjacent two types of tight sandstones, while the fluid pressure within the shale itself plummeted to hydrostatic pressure. The remigration and enrichment of hydrocarbons driven by the high source-reservoir excess pressure difference are of great significance for the formation of the current distribution pattern of the two sandstone gas reservoirs. Meanwhile, after undergoing brittle fracturing and pressure relief during the late tectonic uplift, the organic-rich shale is subjected to overburden compaction under the action of the overlying load, forming an excess pressure difference of 4.45–5.22 MPa between the caprock and the reservoir. The late-stage densification of the shale caprock and the existence of excess pressure further enhance the physical properties and overpressure sealing capacity of the shale caprock, which can effectively prevent the dissipation of accumulated hydrocarbons and provide a guarantee for the preservation of the Shan 1 Member tight sandstone gas reservoir.

In summary, the coupling effect between the pressure differential evolution of different lithologies and the densification process of sandstones across the aforementioned three stages systematically reveals the reservoir formation mechanism of tight sandstone gas reservoirs in the study area. It clarifies the role of the source-reservoir excess pressure difference in hydrocarbon charging during different densification stages, thereby providing theoretical support for the exploration and development deployment of similar tight sandstone gas reservoirs.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- At the end of the Early Cretaceous, overpressure was extensively developed in the shales of each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the Yanchang area, southeastern Ordos Basin. The genetic mechanism of the paleo-overpressure was attributed to hydrocarbon generation and disequilibrium compaction, which caused respective fluid pressure increases of 13.97–16.04 MPa and 9.21–9.27 MPa.

- (2)

- During the tectonic uplift since the Late Cretaceous, the decrease in formation temperature and brittle fracturing-induced pressure relief are the main controlling factors for the evolution of the shale strata in each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the study area from ultrahigh pressure to the current normal pressure or weak overpressure. Among them, the temperature decrease results in a formation pressure reduction of 12.95–17.75 MPa, with a reduction rate of 38.11–41.65%; the brittle fracturing-induced pressure relief of the shale strata is 20.00–25.24 MPa, with a reduction rate of 58.35–61.89%. Brittle fracturing plays a dominant role in the evolution of the shale strata to the current normal pressure or overpressure state.

- (3)

- The controlling factors for the formation of the current underpressure in the sandstones of each sub-member of the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the Yanchang area, southeastern Ordos Basin, are temperature reduction and pore rebound. These two factors, respectively, induce a formation pressure decrease of 12.07–13.85 MPa and 16.93–17.41 MPa in the sandstones, accounting for 40.94–45.00% and 55.00–59.06% of the total pressure reduction, respectively. Additionally, the hydrocarbon charging during reservoir formation, together with the fracturing-induced pressure relief of the adjacent organic-rich mud shales during the late tectonic uplift stage, collectively induces overpressure transfer; this overpressure transfer contributes a pressure increase of 7.32–8.58 MPa to the sandstone formations in the study area. Under the combined effect of the aforementioned factors, the sandstone formations in the study area have evolved into their current underpressure state.

- (4)

- The pressure differential evolution in the “shale–sand–shale” lithological combination of the Shan 1 Member of the Shanxi Formation in the study area permeates the entire reservoir formation process of tight sandstone gas. The source-reservoir excess pressure differences formed at various stages serve as key driving forces for the multi-stage hydrocarbon charging. During the late tectonic uplift stage, the densification of the shale caprock and the 4.45–5.22 MPa excess pressure difference formed with the adjacent sandstone promote hydrocarbon preservation by enhancing the caprock’s physical sealing capacity and overpressure sealing capacity; these two factors jointly lay the foundation for the current distribution pattern of tight sandstone gas reservoirs in the study area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Z. and S.L.; Data Curation, S.L., F.Z., X.Q. and J.W.; Formal analysis, S.L., Y.J. and Z.L.; Funding acquisition, F.Z., Z.Z. and J.G.; Methodology, S.L., F.Z., Z.Z., X.Q., J.W., J.G., Y.J. and Z.L.; Investigation, S.L., F.Z., X.Q., J.W., Y.J. and Z.L.; Supervision, F.Z., Z.Z. and J.G.; Visualization, S.L. and F.Z.; Writing—original draft, S.L.; Writing—review and editing, F.Z. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was jointly supported by the National Oil & Gas Major Project sponsored by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (Grant No. 2025ZD1400206); and the Graduate Innovation and Practical Ability Training Program of Xi’an Shiyou University (Grant No. YCX2513093).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Birchall, T.; Senger, K.; Swarbrick, R. Naturally occurring underpressure—A global review. Pet. Geosci. 2022, 28, petgeo2021–petgeo2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.H.; Gianoutsos, N.J.; Drake, R.M., II. Underpressure in Mesozoic and Paleozoic rock units in the Midcontinent of the United States. AAPG Bull. 2015, 99, 1861–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umari, A.M.J.; Nelson, P.H.; Fridrich, C.; LeCain, G.D. Simulating the Evolution of Fluid Underpressures in the Great Plains, by Incorporation of Tectonic Uplift and Tilting, with a Groundwater Flow Model. Geofluids 2018, 2018, 3765743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchall, T.; Senger, K.; Hornum, M.T.; Olaussen, S.; Braathen, A. Underpressure in the northern Barents shelf: Causes and implications for hydrocarbon exploration. AAPG Bull. 2020, 104, 2267–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.C.; Chen, D.X.; Gao, X.Z.; Wang, F.W.; Li, S.; Tian, Z.Y.; Lei, W.Z.; Chang, S.Y.; Zou, Y. Evolution of abnormal pressure in the Paleogene Es3 formation of the Huimin Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2021, 203, 108601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.C.; Chen, D.X.; Wang, F.W.; Gao, X.Z.; Zou, Y.; Tian, Z.Y.; Li, S.; Chang, S.Y.; Yao, D.S. Origin and distribution of an under-pressured tight sandstone reservoir: The Shaximiao Formation, Central Sichuan Basin. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2021, 132, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, S.L.; Yan, W.; Liu, X.S.; Zhang, C.L.; Yin, L.L.; Dong, G.D.; Jing, X.H.; Wei, L.B. New fields, new types and resource potentials of natural gas exploration in Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2024, 45, 33–51+132. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.K.; Li, G.X.; Cui, J.W.; Huang, F.X.; Lu, X.S.; Guo, Z.; Cao, Z.L. Geological accumulation conditions and exploration prospects of tight oil and gas in China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2025, 46, 17–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.H.; Zhao, H.T.; Dong, G.D.; Han, T.Y.; Ren, J.F.; Huang, Z.L.; Lu, Z.X.; Zhu, B.D.; Zhu, J.; Yin, L.L.; et al. Discovery and prospect of oil and gas exploration in new areas of Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2023, 34, 1289–1304. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L.C.; Dong, D.Z.; He, W.Y.; Wen, S.M.; Sun, S.S.; Li, S.X.; Qiu, Z.; Liao, X.W.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; et al. Geological characteristics and development potential of transitional shale gas in the east margin of the Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 435–446. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Z.; Qiao, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.K.; Zhou, J.S.; Du, Y.H.; Cao, J.; Xin, C.P.; Song, J.X.; Yuan, F.Z. Innovation and scale practice of key technologies for the exploration and development of tight sandstone gas reservoirs in Yan’an Gas Field of southeastern Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2022, 42, 102–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Qiu, Z.; Zhao, P.H.; Li, S.X.; Dong, D.Z.; Liu, H.L.; Hou, W.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, Y.F.; et al. Research status and prospect of accumulation conditions of transitional facies shale gas in the eastern margin of Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2023, 34, 868–887. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Chen, H.L. Evolution of fluid pressure distribution in the Upper Paleozoic of the Shenmu-Yulin area and its implications for natural gas accumulation. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2007, 37, 49–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.J. Forming Process of Underpressure and Its Impact on Shale Gas Enrichment, Shan1 Member, Southeastern Ordos Basin. Master’s Thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ma, L.Y.; Luo, Q.Q.; Chen, C.F.; Han, B.; Li, C.; Zheng, X.W. Pressure Evolution of Upper Paleozoic in Hangjinqi Area, Ordos Basin. Geoscience 2020, 34, 1166–1180. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Liu, K.; Shi, W.Z.; Qin, S.; Zhang, W.; Qi, R.; Xu, L. Reservoir densification, pressure evolution, and natural gas accumulation in the Upper Paleozoic tight sandstones in the North Ordos Basin, China. Energies 2022, 15, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.L.; Xu, H.Z. Pressure distribution and genesis of fluid in the Upper Paleozoic of the Ordos Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2010, 32, 536–540. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Zhao, J.Z.; Liu, X.S.; Zhao, X.H.; Cao, Q. Distribution characteristics and genesis of present formation pressure of the Upper Paleozoic in the eastern Ordos Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2013, 34, 646–651. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.J.; Wang, L.L.; Ren, K.X.; Ye, Y.F.; Liu, Y.K.; Chen, F.; Ma, L.Y.; Hou, Y.G. Pressure evolution and underpressure generation in the Shanxi sandstone reservoirs of the Xinzhao area, northern Ordos. Bull. Geol. Sci. Technol. 2026, 45, 1–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Yang, Y.; Yan, X.X.; Chen, H.; Jia, L.; Liang, X. Quantitative analysis of the abnormal low pressure of the fifth member of Shiqianfeng Formation in Yulin-Shenmu area, Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2025, 36, 284–292. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.Q.; Song, P.; Zhang, B.; Chen, M.; Wu, W.T. Origin and evolution of paleo-overpressure in the upper Paleozoic in Linxing area, the eastern margin of Ordos Basin, China. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2020, 35, 19–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.L.; Li, S.J.; Nie, H.K.; Yuan, Y.S.; Wang, H. The shale gas “sweet window”: “The cracked and unbroken” state of shale and its depth range. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 101, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]