Abstract

Microplastics represent a pressing global environmental concern due to their persistence, widespread occurrence, and adverse impacts on aquatic ecosystems and human health. Effective removal of these contaminants from water is essential to safeguard biodiversity and ensure water quality. This work focuses on the pivotal role of membrane-based filtration technologies, including microfiltration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, membrane bioreactors, and dynamic membranes, in capturing and eliminating microplastics. The performance of these systems depends on key membrane characteristics such as pore size, material composition, hydrophilicity, mechanical strength, and module design, which govern retention efficiency, fouling resistance, and operational stability. Membrane filtration offers a highly effective, scalable, and sustainable approach to microplastic removal, outperforming conventional treatment methods by selectively targeting a wide range of particle sizes and morphologies. By highlighting the critical contribution of membranes and filtration processes, this study underscores their potential in mitigating microplastic pollution and advancing sustainable water treatment practices.

1. Plastics and Microplastics

1.1. Definition of Plastics: Types and Properties

Plastic is a material made from large molecules called polymers, which are formed by chemically linking together many smaller, repeating units called monomers, like beads on a string, creating long chains (polymer) that give plastic its strength, flexibility, and moldability (its ‘plastic’ nature), being used in a range of applications, including packaging, medical devices, and consumer products [1,2]. Its strength and low weight make it useful across numerous industries, improving efficiency in manufacturing, distribution, and waste management. Natural plastics, produced or secreted by microorganisms, are often biodegradable but rarely used on a large scale, while the synthetic plastics, derived mainly from petrochemical sources such as natural gas, petroleum, or coal, are widely employed and commonly referred to as petroleum-based plastics [3]. The main plastic materials identified in effluents are polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polycarbonate (PC), polyamides (PA), polyester (PES), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and rigid thermoplastic polyurethane (PU). These thermoplastics are recyclable since they can be reheated, reshaped, and cooled multiple times without significant loss of properties [4,5]. Many polymers are derived from petroleum and contain ester functional groups within their repeating units, with polyethylene terephthalate (PET) being the dominant polyester used in textile production. In addition, polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) are widely utilized across numerous sectors, with PP and PE being the most prevalent.

Plastics differ from polymers in that they are formulated materials, typically a single polymer or polymer blend combined with low-molecular-weight additives such as stabilizers, flame retardants, dyes, antioxidants, pigments, antimicrobial agents, lubricants, and fillers [6,7,8,9,10] (Table 1).

Table 1.

The most widely produced polymers are presented with their abbreviations, common uses, specific densities, and recycling symbols, with particular focus on synthetic polymers present in the marine environment (adapted from [9,10]).

1.2. Plastic Production Has More than Doubled in the Last Two Decades

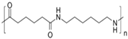

The first synthetic plastic, Bakelite, was developed in 1907, marking the beginning of the modern plastics industry. Since the 1950s, plastic production has increased dramatically due to its versatility and low production cost, accompanied by a comparable rise in plastic waste generation. Over the subsequent 70 years, annual plastic output increased nearly 230-fold, reaching 460 million tonnes by 2019, highlighting its rapid and sustained expansion [11]. The handling of this vast quantity of waste has been largely inefficient, with about 79 wt.% ultimately disposed of in landfills or released into the natural environment, both on land and in marine ecosystems [1,11]. Since the latter half of the 20th century, global plastic production has grown exponentially, reaching 400.3 million tonnes in 2022, intensifying the environmental concerns, particularly plastic pollution, which disrupts ecological processes [12] and affects the global carbon cycle [13]. In 2022, global plastic production totalled 400.3 million tonnes, representing a 1.6% rise compared to the previous year and highlighting the material’s versatility and ongoing growth in market demand (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual global plastic production from 1950 to 2022 (in million metric tonnes), along with the projected total production forecast through 2060 [1,11].

The absence of evidence for a decline in plastic debris in marine environments, together with projections estimating an additional 33 billion tonnes of plastic by 2050, underscores the urgent need for sustainable practices and the adoption of circular economy strategies [14,15,16]. Plastic production continues to increase, rising from 335 million tonnes in 2016 to 348 million tonnes in 2017, with Asia remaining the largest producer (50.1%), followed by Europe (18.5%), NAFTA countries (17.7%), the Middle East and Africa (7.71%), Latin America (4%), and the CIS (2.6%) [14,16]. The total amount of plastic currently present in the world’s oceans is estimated at 236,000 metric tonnes, while an additional 4.8 to 12.7 million tonnes enter marine environments annually [2,17]. Once introduced into aquatic systems, plastics can persist for periods ranging from months to millennia, gradually fragmenting through mechanical and photochemical processes into microplastics (<5 mm) and nanoplastics (<1 μm) [18,19].

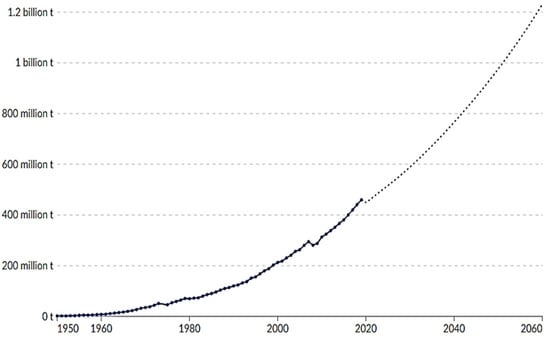

The plastics are produced in large quantities and degrade very slowly, and consequently, it accumulates in the environment, especially through wastewater discharge, generating a vast plastic waste, much of which enters aquatic ecosystems, raising serious environmental concerns [1,20]. Although plastic waste is landfilled, incinerated, or recycled, a substantial portion remains poorly managed and ultimately escapes into the natural environment. Over the past 70 years, global dependence on plastics has increased sharply. Between 1950 and 2015, plastic production grew at an average annual rate of 8.4% [1], and its recent growth has even surpassed that of carbon emissions [21,22] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Country-level estimates of per capita plastic waste emitted to the ocean in 2019. Values represent the annual emissions and reflect waste generated within each country; exported waste is not included in national totals. It depicts the country’s total waste (MT year−1) per country exported overseas, which represents a higher risk of entering the ocean. Adapted from [22].

1.3. Types of Microplastics

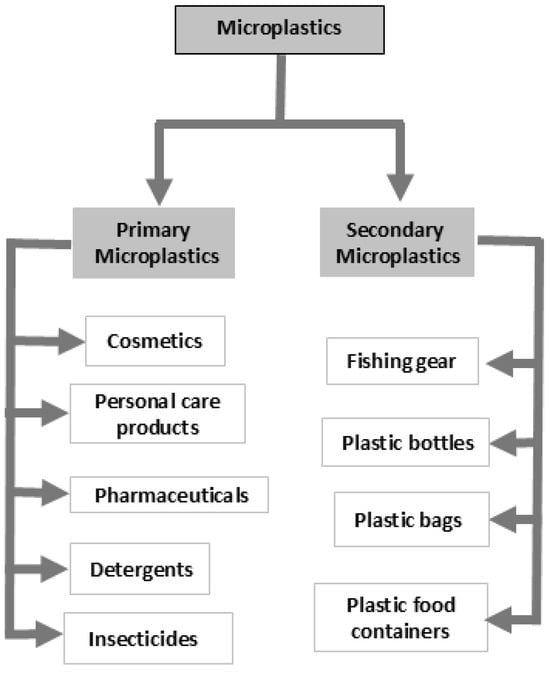

Microplastics (MPs) are synthetic polymer particles released into water from sources such as surface water, groundwater, wastewater, tap water, and bottled water [23,24,25,26,27,28]. MPs vary in size and morphology, fragments, films, pellets, foams, and fibers, and are categorized by size as nanoplastics (<0.1 µm), microplastics (1 µm–5 mm), mesoplastics (5–25 mm), macroplastics (25 mm–1 m), and megaplastics (>1 m) [29,30]. Common polymer types include polyethylene, polypropylene, and polystyrene [31] (Figure 3). They originate from primary MPs, which are intentionally manufactured for products like cosmetics, personal care items, pharmaceuticals, and detergents, and secondary MPs, formed from the degradation of larger plastics, including bottles, bags, and fishing gear [32].

Figure 3.

Microplastics are classified as primary (intentionally manufactured particles) or secondary (fragments derived from the degradation of larger plastics). Adapted from [33].

1.3.1. Primary Microplastics

Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured and used as raw materials in industrial processes or directly in consumer and commercial products [34]. These particles enter the environment mainly through consumer wash-off, moving into wastewater systems and eventually passing through wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) into aquatic and coastal ecosystems. The plastics industry uses small plastic pellets as production feedstock, and while some losses occur during manufacturing, significant amounts are released during handling and transport [35,36].

1.3.2. Secondary Microplastics

Unlike primary microplastics, which are deliberately manufactured as small particles, secondary microplastics result from the breakdown of larger plastic items through processes such as fragmentation, waste treatment, weathering, and exposure to UV radiation [34]. In coastal areas, shipyards produce plastic debris from the degradation of ship-coating paints, while further particles are released during ship dismantling at the end of a vessel’s service life [23,37,38,39]. Construction materials such as plastic paints contain polymeric resins that degrade into small fragments through removal or climatic exposure, which can then be washed into aquatic environments [40,41]. Secondary microplastics originate from synthetic textiles, interior coatings, and polyurethane fillers, among others. The degradation of microplastics is caused by exposure to temperature and UV rays, which cause structural changes, cracking, color fading, and weakening of particles [42]. Fragmentation is further promoted by mechanical forces such as wind, waves, fauna, and human activities. On beaches, where UV radiation and abrasion are more intense, degradation occurs more rapidly [43]. Urban runoff is another important source, transporting waste from asphalt, car tires [44,45], and road signs [40] into waterways. In the agricultural sector, microplastics originate from the degradation of plastic films used for ground covering and silage. In landfills, the combined influences of temperature, pH, and mechanical compaction accelerate plastic breakdown, generating microplastic debris that can be transported through leachate or dispersed by wind [35].

1.4. Microplastics in the Environment—Source and Characteristics

Microplastics represent the most prevalent form of plastic pollution in marine environments [46]. These are small synthetic particles that do not dissolve in water and are highly persistent and non-degradable materials that are present in both saltwater and freshwater ecosystems [47,48,49].

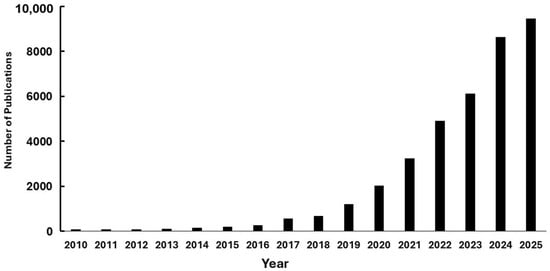

Environmental studies initially concentrated on larger plastics, but attention has increasingly shifted toward smaller particles, microplastics, which encompass granules, fragments, and fibers less than 5 mm [50]. The trend in scientific publications on microplastics from 2001 to 2023, based on data from ScienceDirect®, highlights the growing importance of this topic in the scientific community, especially from 2018 onwards (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of publications related to microplastics from 2001 to 2025 (source: ScienceDirect, 26 October 2025), representing a significant interest in this specific topic.

1.5. Main Sources of Microplastics and Their Distribution

Microplastic pollution has emerged as a critical environmental issue, with secondary microplastics now recognized as the main source in ecosystems [51]. Fibers and pellets in freshwater systems primarily originate from wastewater discharges containing synthetic textiles and personal care products, while poor landfill management also contributes to their release [52,53,54]. Sludge from wastewater treatment plants further adds to microplastic contamination [55]. Erosion and precipitation can increase the transport and resuspension of microplastics in surface waters [56,57]. Rapid economic development and higher living standards have led to a surge in plastic waste, often improperly disposed of along roads, open spaces, or illegal dumps, with an estimated 4.97 billion tonnes accumulated in landfills. Particles and fibers from these sites can enter soil ecosystems through atmospheric deposition [58]. Soil-associated dust, particularly urban street dust, is a notable source of microplastics. It primarily originates from atmospheric deposition of suspended particles or the accumulation of surface materials linked to human activities [59]. Road dust can be easily transported by surface runoff into water bodies, making it a significant pathway for microplastic pollution [51]. With increasing production, microplastics are now widespread across multiple environmental compartments, including freshwater and marine systems [60,61], sea ice [62], sediments [63], soil [64], and the atmosphere [65]. They have even been detected in remote areas such as mountains, lakes [66], the Gobi Desert, and karst groundwater [67]. Once in soil, microplastics can be transported to other environmental matrices, including the atmosphere and nearby water bodies, via wind erosion, runoff, or human activities, it can infiltrate the groundwater system [67,68]. The aquatic environments are dynamic systems characterized by continuous hydrodynamic activity, including rainfall, monsoons, wave action, tides, and ocean currents. Microplastics may move between terrestrial and aquatic environments via tidal movements and flooding events [69]. Wind and associated wave action can induce vertical mixing within the water column, causing the resuspension of plastics from the sediments. The transport and distribution of microplastics are influenced by intrinsic material properties, including density, size, color, and shape [70]. Microplastics originating from plastic production and consumption are carried via surface runoff through watersheds into rivers. These rivers serve as major conduits, transporting approximately 88% to 95% of global microplastic loads toward coastal and estuarine environments.

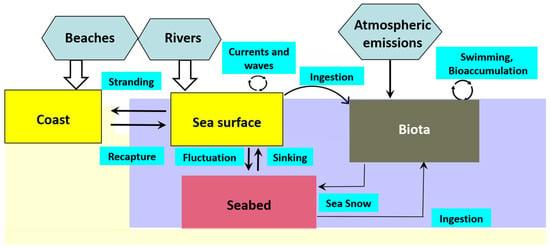

In freshwater systems, microplastic density affects vertical distribution within the water column. Low-density microplastics tend to remain at the surface, while high-density particles typically accumulate in the bottom [71,72]. The sources of microplastics in aquatic environments can be broadly categorized into land-based and atmospheric deposition [73]. Plastic debris in marine systems accumulates in different oceanic compartments as a consequence of transfer processes between these environments [74] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic representation illustrating the sources of plastic debris entering the sea (ovals), the oceanic compartments where it accumulates (rectangles), and the processes facilitating its transfer between compartments (Adapted from [74]).

Microplastics move between different environmental compartments through processes such as atmospheric transport and surface runoff, allowing them to be transferred from inland regions to marine environments [75]. Plastic pollution in aquatic systems is largely the result of inadequate waste management in the urban, tourism, agricultural and industrial sectors. In addition, maritime traffic, fishing, and other maritime activities directly release plastics into the aquatic environment, contributing to varying levels of contamination [76,77,78]. Larger plastic waste, such as bottles, bags, and packaging, tends to float on the surface of the water, being transported by winds and currents to coastal areas and ocean currents. In contrast, denser fragments sink, forming reservoirs of debris that negatively affect habitats and benthic organisms [79]. In turn, microplastics suspended in the water column, resulting from the degradation of larger plastics by processes such as photodegradation and abrasion, can travel long distances through ocean currents, posing a persistent threat to marine life [1].

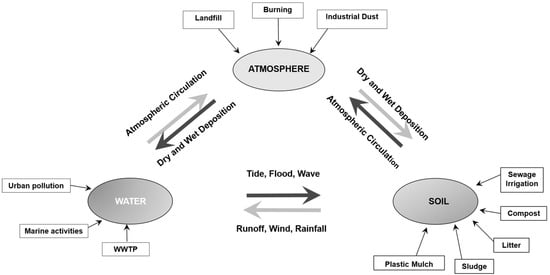

Atmospheric microplastics originate from a wide range of sources and associated degradation processes, including industrial dust, textile fibers, particles released from building materials, and various daily human activities, all of which contribute to their continuous and persistent emission into the atmosphere [80,81]. Once airborne, these microplastics can contribute to pollution in both aquatic and terrestrial environments. The transport and deposition of atmospheric microplastics are governed by several factors, including wind speed and direction, precipitation, and particle density [82]. While some microplastics remain suspended in the air, others are deposited through dry and wet deposition processes and may subsequently be resuspended and redistributed, eventually reaching terrestrial and aquatic systems through surface contact [58] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cycles of microplastics in the environment (Adapted from [51]).

1.6. Hazard and Risks Associated with the Release of Microplastics Settle

Microplastics have a significant negative impact on marine life, drawing the attention of the scientific community and, consequently, society to their effects on ocean ecosystems [14]. Plastic contamination in marine environments is a widespread and effectively irreversible process, constituting a global chemical pollution threat [83]. Owing to their small size, microplastics can be ingested by organisms, thereby entering the food chain and accumulating at higher trophic levels [84].

1.6.1. Plastic Ingestion by Marine Biota

Plastic debris in the marine environment has significant negative impacts, mainly through ingestion by various organisms, being consumed across trophic levels, from zooplankton and invertebrates to echinoderm larvae, posing risks to ecosystems and human health [14,85]. Ingestion can occur directly, when plastics are mistaken for food, or indirectly via contaminated prey, enabling microplastics to move up the marine food web from plankton to higher predators [86].

1.6.2. Plastic as a Source and a Vector of Potential Toxins

Plastics exert a considerable environmental impact due to the presence of potential toxic materials, such as plastic additives, including monomers and oligomers, which are released during degradation processes and negatively affect marine organisms [16,87,88,89,90,91,92,93]. Microplastics can also act as transport vectors for chemical compounds associated with plastic particles, such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and chemicals derived from the plastics themselves, which tend to be concentrated on the surface of the particles [16,90,94,95,96]. At the same time, high concentrations of chemical additives have been detected in marine plastics, including bisphenol A, a monomer used in polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins lining food and beverage cans; nonylphenol (NP), a stabilizer present in polypropylene, and polystyrene; polybrominated diphenyl ethers, used as brominated flame retardants; and phthalates, plasticizers used to make plastics flexible [97].

1.6.3. Microplastics and Derivatives in Marine Organisms

Microplastics are widely distributed across natural habitats and, consequently, in various organisms, including benthic invertebrates, lobsters, numerous fish species, seabirds, and marine mammals, among others [98,99,100,101,102,103]. The broad range of affected species highlights the widespread nature of the problem, impacting multiple levels of the food web and demonstrating the potential transfer of microplastics from planktonic organisms at the base of the trophic chain to higher-level predators [2]. The presence of microplastics and associated chemical additives, such as PBDEs, phthalates, nonylphenols, bisphenol A, and antioxidants, has been reported in various marine organisms as well as in their surrounding environments [3], highlighting the scale of the issue and the risks posed across different habitats (Table 2).

Table 2.

Some examples of the presence of plastics and their derivatives are found in different organisms.

1.7. Impacts of Microplastic Ingestion on Organisms

Microplastics can be readily ingested by marine organisms across different levels of the food web, including zooplankton, invertebrates, echinoderm larvae, and others [14]. The detection of microplastics in zooplankton, fish, and marine mammals has raised concerns regarding their adverse effects on aquatic biota, and represents a potential risk to human health, given the significant role of these species in human consumption (Table 3). Reported adverse effects include alterations in the reproductive system, neurotoxic effects, increased cancer risk, immune system dysfunctions, and potential toxicity resulting from the leaching of chemical additives present in plastics [125,126].

Table 3.

Some reported examples of adverse effects resulting from the ingestion of microplastics and their derivatives in the organisms.

1.8. Microplastics and Domestic Wastewater—The Critical Importance of Microfibers

In the coming decades, the human population is expected to continue growing significantly, particularly in major coastal cities, resulting in increased volumes of wastewater discharged into marine environments and, consequently, in the enhanced accumulation of microplastics [141]. Regarding domestic wastewater, microplastics can originate from two main sources: (a) primary microplastics, including polyethylene, polypropylene, and polystyrene particles derived from personal care products, cosmetics, and cleaning agents; and (b) secondary microplastics, consisting of fibers from the degradation of synthetic textiles, such as polystyrene, acrylic (PMMA—polymethylmethacrylate), and nylon (polyamide), released during mechanical washing processes [35,142]. Among these, microfibers are particularly critical, being classified as microplastics smaller than 5 mm in size [50].

The textile industry is considered one of the most polluting sectors in terms of microfibers, due to the use of potentially hazardous materials in its production, including additives and textile microfibers, which pose risks to human health and the environment due to their release during washing. Synthetic fibers, predominantly polyester, acrylic, and polyamide, are of particular concern. For example, a single garment can release more than 1900 fibers per wash, reaching concentrations of more than 300 mg per kilogram of washed fabric, although these values vary depending on washing conditions [143,144,145]. These fibers are discharged into domestic sewage systems and routed to wastewater treatment plants.

Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTP) are generally effective at filtering microplastics, achieving removal rates between 65% and 99.9%, depending on the size of the particles. WWTPs act as barriers to reduce uncontrolled microplastic emissions by removing them from wastewater. However, despite their efficiency, large amounts of microplastics continue to enter the environment through WWTP effluents due to the huge volumes of water produced [53]. Given the enormous volume of water processed, there is a pressing need for more robust and continuous investment in the development of technologies that can be implemented upstream. One potential solution is the development and implementation of environmentally friendly technologies in washing machines to capture microfibers released during laundering. Because current wastewater treatment systems have limited capacity to remove microplastics, there is an increasing need to develop and optimize more effective approaches, such as advanced membrane filtration processes [5,146,147]. These advances can play a key role in reducing the release of microfibers into the environment. Wastewater treatment plants are generally effective at removing microplastics, achieving rates between 65% and 99.9%, depending on the size of the particles. These facilities act as barriers, reducing the uncontrolled emission of microplastics by retaining most of the particles present in wastewater. However, despite their efficiency, significant amounts of microplastics are still released into the environment through effluents, due to the huge volume of treated water [53].

Given this scenario, there is a pressing need for continuous and robust investments in the development of technologies that can be implemented upstream. One potential solution is the creation and application of environmentally friendly technologies in washing machines, capable of capturing microfibers during the wash cycle. As current wastewater treatment methods have limitations in removing microplastics, it is increasingly necessary to develop and optimize more efficient processes, such as membrane filtration [5,146,147]. Such advances can play a key role in reducing the release of microfibers into the environment.

2. Processes Associated with Microplastic Removal

2.1. Membrane Applications in Water Treatment

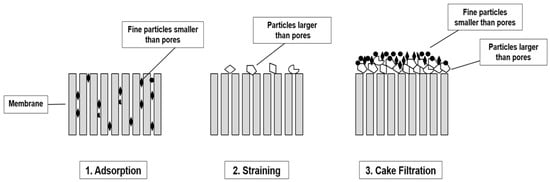

Microplastic pollution can be managed through strategies focused on containment, mitigation, and separation, all of which aim to limit the release of MPs from major sources into the environment. Containment involves proper plastic disposal practices to prevent environmental release, while mitigation promotes behaviors that reduce MP generation and spread, thereby limiting environmental accumulation. Separation targets the removal of MPs during wastewater treatment to prevent their entry into aquatic ecosystems, and ongoing research is critical to improve these technologies sustainably. In particular, optimizing membrane materials to minimize fouling, enhance durability, and reduce energy demands is essential for large-scale adoption [148]. Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are designed to remove solid particles and toxic residues from effluent and sludge, achieving minimal environmental impact after discharge [53], and standard facilities can reduce MP concentrations to approximately one particle per liter [5]. Several unit operations within WWTPs show promise for MP removal [5,149], with filtration systems effectively separating MPs based on size, although their efficiency decreases in viscous sludge. Different techniques such as skimming and gravity separation may remove some MPs; however, their effectiveness is limited by the variable buoyancy of MPs and the presence of organic contaminants [150,151]. Filtration operates through three primary mechanisms: physical retention of particles larger than membrane pores, cake-layer formation as accumulated solids create an additional resistance layer, and adsorption, where smaller particles adhere to membrane surfaces, a temporary process occurring primarily after backwashing but one that contributes significantly to fouling and necessitates cleaning. Surface water often contains elevated concentrations of suspended solids, including MPs, dissolved organic matter, and microorganisms, requiring advanced filtration and treatment processes. Water treatment may employ granular media filters or membrane filters, applicable at both central plants and point-of-use, with post-filtration disinfection essential to prevent recontamination. Despite these advances, microplastic-induced fouling remains a critical challenge, highlighting the need for a mechanistic understanding of pore-blocking behavior, cake-layer formation, and synergistic interactions with natural organic matter (NOM) or extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Pore-blocking reduces flow as MPs lodge within membrane pores, cake-layer formation adds hydraulic resistance while potentially trapping NOM/EPS, and synergistic interactions can accelerate fouling, degrade membranes, and compromise long-term stability. Clarifying the relative contributions of these mechanisms through experimental and modeling approaches is essential for designing fouling-resistant membranes, optimizing cleaning protocols, and enabling effective large-scale MP removal [53,55,151,152,153]. Over time, filtration technology has evolved from the removal of large particles, such as sand, silt, and organic matter, using porous stone or sandy media to the efficient retention of particulate matter (PMs) ranging from a few micrometers to several millimeters. This evolution underscores the central role of filtration in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and highlights the effectiveness of specific filtration methods in mitigating microplastic pollution (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The main removal mechanisms of particles by membrane.

2.2. Membrane Filtration—Typology and Properties

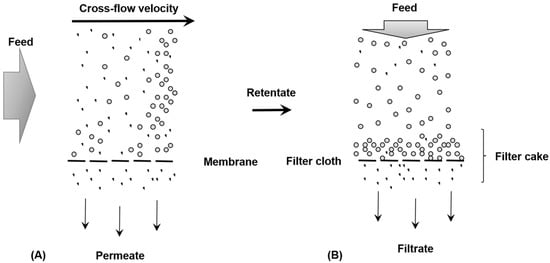

Membrane filtration is an advanced physico-chemical separation process that uses thin (<1 mm) semi-permeable synthetic polymeric membranes. Water is driven through the membrane under pressure, producing permeate (filtered water) and retentate (concentrated rejected particles). Unlike conventional filtration, which removes particles larger than 0.1 mm, membrane processes can remove particles as small as 0.0001 mm, depending on the membrane type. Membrane filtration is widely used in water treatment to remove fine particles, microorganisms, colloids, dissolved organic matter, and certain ions. Four main types of membrane filters are classified by their nominal pore size [154]. Membrane flux, the rate at which molecules pass through the membrane, is a key characteristic influenced by operating conditions such as pressure, temperature, and flow velocity. Membranes function as selective barriers, permitting certain substances to pass while restricting others, with separation governed by properties such as particle size and charge. Transport across a membrane requires a driving force, which may include pressure differentials, concentration gradients, or electric potential fields. Pressure-driven membrane systems are classified according to their operating pressure [155]. Membrane filtration is commonly conducted using either cross-flow (tangential-flow) or conventional “dead-end” filtration configurations (Figure 8A,B). In cross-flow systems, the feed stream flows parallel to the membrane surface. The fraction that passes through the membrane is referred to as the permeate or filtrate, whereas the retained components constitute the retentate or concentrate.

Figure 8.

Operating schemes for cross-flow membrane filtration (A); and conventional “dead-end” (B).

The main advantage of cross-flow filtration is its ability to continuously remove material from the membrane surface, reducing the accumulation of solids or cake that can hinder performance in conventional filtration. This mechanism lowers resistance to filtration and improves overall efficiency. The effectiveness of tangential-flow systems depends on the rate at which retained molecules are transported from the membrane to the bulk fluid, minimizing surface fouling [156].

The membrane is often operated with recirculation of the retentate, as the permeate flow rate is typically much lower than the transverse flow rate of the fluid. This recirculation allows the feed to come into repeated contact with the membrane, enhancing permeate separation. Membranes are classified into two main categories: symmetric (homogeneous) and asymmetric (anisotropic) [157].

Symmetric membranes have uniform pore sizes throughout their cross-section, providing consistent morphology and functioning as both surface and depth filters. Flow through these membranes can occur in either direction. While symmetric membranes effectively retain material on their surface, they also capture particles of similar size to the membrane’s pores, which can lead to reduced efficiency over time due to particle entrapment within the membrane structure. This makes them prone to irreversible blockage.

Asymmetric membranes, on the other hand, consist of a thin, dense separation layer supported by a porous substrate. This layered structure improves filtration efficiency by reducing transport resistance. The ultra-thin skin layer (0.1–1 μm) selectively filters particles, while the thicker macroporous layer helps minimize permeate resistance. Flow through asymmetric membranes is unidirectional, moving from the dense skin layer to the macroporous layer. These membranes act primarily as surface (screen) filters, preventing particles from becoming trapped within the membrane. As a result, asymmetric membranes are less prone to blockage compared to symmetric membranes, and cleaning is more straightforward, requiring treatment only on the surface rather than throughout the entire membrane, resulting in more efficient, long-lasting filtration performance [157].

2.3. Membrane Properties and Performances

2.3.1. Polymeric Membranes

Membrane performance is defined by permeability (flow) and selectivity, which depend on properties such as pore size or molecular weight cut-off (MWCO). MWCO is the molecular weight (Da) at which the membrane retains ~90% of a solute and is one of the main UF indicators. Ideal membranes combine high porosity and flow with well-defined rejection characteristics such as mechanical strength and flexibility, resistance to temperature/pH/pressure fluctuations, low fouling propensity, and cost-effective manufacturability. Based on the nature of the materials used in their fabrication, membranes employed in wastewater treatment are generally classified as polymeric or inorganic. Polymeric membranes are typically more economical and easier to manufacture than inorganic membranes [158].

Membranes made from polymers such as polyether sulfone (PES), polysulfone (PSf), polyetherimide (PEI), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), polyamide (PA), polyacrylonitrile (PAN), cellulose acetate (CA), polycarbonate (PC), and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) are widely used in filtration due to their durability, chemical resistance, and reliable performance [159,160,161,162]. Among these, PES is favored for ultrafiltration and nanofiltration because of its high flow rates, rapid wetting, asymmetric pore structure, and strong mechanical and chemical stability [163,164]. PES membranes offer high porosity, low protein adsorption, precise particle retention, and good pH tolerance, making them ideal for biotechnology and pharmaceutical applications. However, their inherent hydrophobicity can promote fouling, reducing water flux and increasing maintenance.

Cellulose acetate (CA), a natural, hydrophilic polymer, provides biodegradability, environmental compatibility, low toxicity, and cost-effectiveness [165,166,167,168]. CA membranes are used in water and wastewater treatment, gas separation, pharmaceuticals, and adsorption processes. They support various filtration methods, including microfiltration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis. Additionally, CA membranes can be fabricated in diverse forms: flat sheet, hollow fiber, or electrospun, offering flexibility for specific applications. Their combination of hydrophilicity, durability, and sustainability makes CA an attractive alternative for environmentally conscious membrane technologies.

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), known as Teflon, has a 3D porous structure resembling a spider’s web, making it highly effective for non-stick, water-resistant filtration and particle removal [169,170]. Its chemical inertness, hydrophobicity, and durability stem from the strong carbon-fluorine bonds (485 kJ mol−1) and the properties of fluorine, including high electronegativity and low polarizability. These characteristics make PTFE membranes suitable for harsh environments and long-term applications, particularly in liquid/air separation. However, PTFE membranes face challenges due to their single-pore structure and strong hydrophobicity. Relatively large and unevenly distributed pores can cause moisture retention issues, while hydrophobicity can promote fouling and reduce efficiency in water treatment [171,172]. To overcome these limitations, surface modifications or treatments are often required to enhance wettability, minimize fouling, and improve overall membrane performance across various applications.

Polyamide (Nylon) membranes are hydrophilic and solvent-resistant, suitable for filtering both aqueous and organic solutions. Their relatively large pores enable efficient isolation of unicellular and some multicellular organisms in biological and environmental applications. Cellulose nitrate membranes are widely used for sterile filtration and quality control, providing effective microbial retention across various pore sizes. Blended cellulose nitrate–cellulose acetate membranes offer improved thermal stability and higher flow rates, making them versatile for microbiological and pharmaceutical filtration.

Polycarbonate membranes are durable thermoplastics with excellent mechanical strength and chemical resistance. Their precisely controlled pore structures allow selective separation of particles in liquids or gases. Available in pore sizes from nanometers to micrometers, polycarbonate membranes are ideal for applications requiring accurate particle retention and consistent performance. Studies evaluating the performance of polycarbonate, cellulose acetate, and polytetrafluoroethylene microfiltration membranes, all with a nominal pore size of 5 μm, reported effective filtration of polyamide and polystyrene particles with diameters ranging from 20 to 300 μm. Based on these findings, the membranes demonstrated particulate matter (PM) removal efficiencies exceeding 94% [173]. However, PM larger than 5 μm were occasionally detected in the permeate, which the authors attributed to membrane abrasion. Additionally, some PM observed in the permeate were smaller than those present in the feed, a phenomenon likely caused by PM fragmentation resulting from mechanical stress during filtration [173].

2.3.2. Inorganic Membranes

Inorganic membranes are made from materials such as alumina (Al2O3), titania (TiO2), silica (SiO2), zirconia (ZrO2), silicon carbide (SiC), silicon nitride, and zeolites, typically comprising a support layer, an intermediate layer, and a top separation layer [174]. Compared to polymeric membranes, they offer superior thermal, chemical, and mechanical resistance, making them suitable for harsh environments. Their hydrophilicity, narrow pore size distribution, and antibacterial properties provide high flux and enhanced separation efficiency [175,176,177]. Common materials include TiO2, SiO2, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), halloysite nanotubes (HNTs), and Al2O3, with hydrophilicity often evaluated via filtration flux recovery [177,178,179].

Inorganic membranes have a longer lifespan (over 10 years) than polymeric membranes, making them ideal for extended operations. However, their fragility and high production costs limit widespread use, leading to the continued preference for polymeric membranes in both large-scale applications, such as wastewater treatment plants, and small-scale laboratory studies (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of polymeric (PES, PVDF, CA, PA) and inorganic/ceramic (alumina, titanium, zirconia, SiC) membranes for microplastic removal, covering processes, pore sizes, MP retention, fouling, cleaning, integration, selectivity, costs, environmental impact, and emerging trends.

3. Characterization of Different Membranes and Filtration Processes Involved in MP

Membrane filtration is a widely used separation technology in water and wastewater treatment. It offers advantages such as high solids retention, high throughput, process flexibility, environmental compatibility, and compact system design. However, membrane systems are susceptible to fouling and often exhibit limited tolerance to aggressive cleaning agents, solvents, extreme pH conditions, and pressure variations. Membrane performance is largely determined by properties such as pore size, hydrophilicity, surface charge, chemical stability, thickness, mechanical strength, and thermal resistance. These characteristics depend on the membrane material, structural configuration, and intended application. In water treatment, for example, semi-permeable membranes enable selective passage of water while retaining pollutants through sieving and diffusion mechanisms, with pressure acting as the primary driving force. Over time, several membrane technologies have been developed: microfiltration (MF, ~0.1 µm), ultrafiltration (UF, ~0.01 µm), nanofiltration (NF, ~0.001 µm), and reverse osmosis (RO, <0.001 µm). These advanced systems are widely used in water and wastewater treatment and typically operate at pressures between 5.2 and 17.25 bar [155]. Low-pressure systems such as MF and UF operate at 0.7–2.1 bar, with MF effectively removing particles larger than 0.08–2 μm at pressures of 0.7–1.0 bar. Efficient MF membranes should exhibit high chemical resistance, low flow resistance, and a uniform pore size distribution [155].

3.1. Microfiltration Membranes

Microfiltration (MF) membranes are porous structures with pore sizes ranging from 0.1 to 10 μm, operating under low pressures of 0–2 bar, being a suitable option for removing suspended solids, colloids, and bacteria, and are commonly used as a pre-treatment step to reduce fouling in downstream UF, NF, and RO systems [188]. Reported MP removal efficiencies range from 81.5% to 100%, with laboratory studies achieving up to 98.5%. MPs larger than the membrane pore size are retained on or within the membrane matrix, whereas typical MPs remaining in treated WWTP effluent are around 100 μm. However, WWTPs often fail to adequately remove smaller MPs, contributing to their release into aquatic environments [189,190,191,192,193]. The frequent detection of MPs < 500 μm in effluents highlights this limitation [194,195]. Improved MP retention can be achieved using MF membranes with pore sizes <1 μm and adequate mechanical strength to withstand operating pressures. Accurate design of permeate collection systems is essential to prevent the unintended passage of microplastics (PM). Microfiltration (MF) membranes have been developed in various forms, including polymeric, ceramic, nanocomposite, and nanofibrous structures, with nanofibrous membranes being particularly promising for applications at submicron to nanometer scales [196]. Commonly used polymers include polyvinylidene fluoride, polysulfone, polyamide, polyether sulfone, polyether ether ketone, polytetrafluoroethylene, and polycarbonate [197] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Overview of membrane filtration technologies for microplastic (MP) removal in water treatment: membrane type, material/characteristics, microplastic abundance in effluent, removal efficiency, size range removed, permeate flux, energy consumption/operational complexity, scalability/technology readiness level (TRL), and key references.

3.2. Ultrafiltration

Ultrafiltration employs asymmetric membranes with pore sizes of 0.001–0.100 µm, operating at 1–10 bar and suggesting low energy consumption with high separation efficiency [211]. Ultrafiltration effectively retains particles and macromolecules such as proteins, fatty acids, bacteria, protozoa, viruses, and high–molecular–weight organic compounds [212,213]. Primarily governed by sieving, UF can complement or replace flocculation, sedimentation, and coagulation in wastewater treatment. Although less efficient at removing low–molecular–weight organics, UF remains valuable as a standalone, sub-, or co-process and serves as an effective pretreatment step for reverse osmosis, protecting downstream systems [20,214].

Distinctions between microfiltration and UF can overlap, as membrane performance depends on pore size, structure, and feed characteristics. UF is particularly advantageous in cell recovery due to its ability to retain macrosolutes with molecular weights of 103–106 Da. Performance enhancements include micellar- and polymer-enhanced UF membranes [215]; micellar-enhanced UF uses surfactants to selectively remove impurities via electrostatic interactions, improving flux, and purification [216]. Polyacrylonitrile-based UF membranes have demonstrated >90% chromium removal and show potential for microplastic (MP) removal, with performance further improved through hydrolysis modifications.

UF membranes are produced in hollow fiber, tubular, sheet, or spiral-wound configurations, typically made from high–pore–density polymeric films. Their asymmetric structure, featuring a thin selective layer supported by a porous sublayer, enables efficient filtration at low resistance. Recent designs incorporate active layers on both sides for bidirectional filtration. Hollow fiber membranes provide high surface area–to–volume ratios and high flux under low pressures. Maintaining antifouling properties is essential for stable permeation, reduced energy demands, and improved hydrophilicity [154]. UF membranes demonstrated strong MP removal capabilities (1–5000 μm), with studies reporting 78.16% MP reduction and overall removal efficiencies approaching 97% when integrated into conventional wastewater treatment processes [197].

3.3. Nanofiltration

Nanofiltration (NF) is define as a pressure-driven membrane process operating at 5–15 bar with pore sizes of 0.001–0.010 µm. NF is primarily used for removing multivalent salts and organic molecules with molecular weights above ~200 Da (MWCO) from wastewater, allowing passage of particles smaller than 0.002 μm while selectively retaining dissolved constituents [217,218]. NF offers higher salt rejection than UF under comparable conditions and provides greater permeate flux than RO [190]. However, its very small pore size requires high operating pressures, limiting broader application; NF use in water treatment has been reported to increase energy demand by 60–150% [219,220].

Due to their charge-based repulsion mechanisms and selectivity, NF membranes are generally not optimal for removing water-soluble plastics. Studies on microplastic (MP) removal by NF remain limited. At a landfill leachate treatment plant (LLTP) in Turkey, combined UF and NF processes removed 96% and 99% of MPs, respectively [206]. MP concentration in the NF permeate was 2 µg/L, with the remaining particles predominantly >500 μm and fiber shaped [206]. Another study in France evaluated six samples treated with an NF membrane (MWCO 400 Da, pore size 0.001 µm) at a drinking water treatment plant; MPs were absent in four samples and detected at 0.018 µg/L (before degassing) and 0.002 µg/L (after degassing) in the remaining two [181].

These findings indicate that while NF can significantly reduce MPs, targeted and systematic research is still required to fully assess its performance in water and wastewater treatment.

3.4. Reverse Osmosis

Reverse osmosis (RO) employs dense membranes with pore sizes of ~0.0001 µm, operating at high pressures of about 20 bar, which contributes to substantial energy demand [197]. Separation occurs via a solution–diffusion mechanism, enabling RO to remove monovalent ions and all contaminants typically rejected by MF, UF, and NF [221,222]. RO is widely applied in seawater and brackish water desalination, as well as in drinking water and wastewater treatment, and has significantly advanced municipal and industrial treatment systems due to its high removal efficiency [223].

RO membranes, nonporous or extremely tight nanofiltration-type structures (>0.002 μm), effectively remove salts, heavy metals, and diverse contaminants, outperforming MF, UF, and NF. However, studies have reported the presence of microplastics in RO permeate in advanced sewage treatment processes. For example, microplastics around 50 μm, mainly fibers and fragments, have been detected in permeate streams [208]. Fiber-shaped MPs may pass longitudinally through the membrane due to their high aspect ratio [209]. Although RO substantially reduces MP concentrations, millions of particles may still reach receiving waters daily.

The persistence of MPs in permeate raises questions about whether they pass through rare defects, originate from membrane abrasion, or enter from external environmental sources [197]. The integration of membrane technologies into conventional drinking water treatment plants (DWTPs) and wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) improves overall MP removal efficiency [207,224].

3.5. Membrane Bioreactors

Membrane bioreactors (MBRs) combine biological treatment with membrane filtration and are widely used in both municipal and industrial wastewater treatment. Depending on membrane placement, MBR systems are typically classified as submerged or side-stream configurations. MBRs have gained increasing attention for the removal of microplastics and pharmaceutical compounds, as they integrate biodegradation with physical retention to enhance the removal of persistent and emerging contaminants [225,226]. These applications underscore the potential of MBR technology to mitigate fouling and improve overall treatment efficiency [227]. MBRs commonly employ MF or UF membranes made from polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), as their larger pore sizes reduce operating pressure requirements and fouling propensity [228,229]. Compared with conventional activated sludge (CAS) systems, MBRs offer multiple advantages, including the elimination of secondary settling tanks, improved effluent quality, reduced sludge production, shorter hydraulic retention times, higher mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS) concentrations, higher loading rates, and longer sludge retention times [230,231,232]. However, high capital costs, membrane fouling, and membrane replacement needs remain barriers to wider implementation [233].

MBRs consistently demonstrate higher MP removal efficiency than CAS systems [5,55]. In CAS secondary settling, MP removal is often limited due to poor settling behavior influenced by MP properties and operating conditions [191]. In contrast, MBR membranes retain MPs effectively [5]. For example, a pilot MBR system with 0.4 μm flat-sheet membranes at a Finnish WWTP achieved MP reductions from 6.9 to 0.005 MP/L, corresponding to 99.9% removal, whereas pilot CAS systems showed secondary effluent concentrations of 0.2 ± 0.06 MP/L, meaning the MBR permeate contained only 2.5% of the MP level in CAS effluent [5]. In the same WWTP, wastewater treated with sand separation, primary clarification, and an MBR contained 0.4 ± 0.1 MP/L, achieving 99.4% removal, compared with 1.0 ± 0.4 µg/L and 98.3% removal in the CAS system [59]. MBR sludge also shows markedly higher MP accumulation than primary and secondary sludges from CAS systems, further indicating superior MP retention [210,234].

3.6. Dynamic Membranes Technology

The dynamic membrane process has gained attention as an effective technology for treating municipal wastewater [4], surface water [235], oily water [236], industrial wastewater [237], and sludge [238]. A dynamic membrane relies on forming a cake layer on a support membrane, which acts as a secondary barrier to retain particles and foulants. Unlike conventional microfiltration or ultrafiltration, filtration resistance is primarily due to the cake layer, and excessive thickness can reduce performance. Dynamic membrane formation depends on support membrane properties (material, pore size), deposited particle characteristics (size, concentration), and operating conditions (pressure, cross-flow velocity) [237,239].

Dynamic membrane offers several advantages: (i) low-cost materials (e.g., mesh, non-woven fabric, filter fabric, stainless steel mesh); (ii) no additional chemicals, as the cake layer consists of influent pollutants; (iii) compact setups with higher permeation fluxes, reducing module requirements; (iv) lower energy consumption due to gravity-driven operation and reduced transmembrane pressure [239,240]. Dynamic membrane is particularly effective for removing low-density and poorly sedimented microparticles, including microplastics [240].

In laboratory studies, dynamic membrane formed on a 90 µm mesh using diatomite (D90 = 90.5 µm) in synthetic wastewater. After 20 min, effluent turbidity dropped below 1 NTU, confirming effective particle removal. Transmembrane pressures (80–180 mm H2O) were ~16 times lower than conventional MF, significantly reducing energy use. Higher influent flow rates (21 L/h) and particle concentrations accelerated dynamic membrane formation, rapidly lowering turbidity to 1.53 NTU within 5 min [20,240].

Although microplastic removal via dynamic membrane is still emerging, combining dynamic membrane with conventional membranes or MBRs enhances overall efficiency. Removal efficiency depends strongly on particle shape, size, and mass [20]. These findings highlight dynamic membranes as an energy-efficient and effective strategy for the removal of microparticles and microplastics in wastewater treatment.

3.7. Operational Viability, Cost, and Secondary Waste Management

Membrane-based filtration technologies, including microfiltration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, and membrane bioreactors, have proven effective for removing microplastics and nanoplastics from water and wastewater. Removal efficiencies depend on factors such as membrane type, pore size, and operational conditions. A thorough evaluation of these technologies should also consider operational feasibility, material costs, and the management of secondary waste. Microfiltration and ultrafiltration membranes are characterized by low-to-moderate energy requirements and simple operation, making them highly viable for large-scale implementation. Laboratory and full-scale studies report removal efficiencies up to 100% for ultrafiltration (e.g., PVDF 0.03 µm flat-sheet membranes) and up to 99% for MF (e.g., SiC/SiC membranes). These membranes maintain relatively high permeate fluxes, supporting continuous operation. Their widespread commercial availability translates into high Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs), ensuring feasibility for both water treatment plants (WTPs) and wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). NF and RO membranes, while capable of removing smaller nanoplastics (<100 nm), require higher energy inputs and exhibit lower permeate fluxes. RO systems, for instance, can achieve ~99.8% removal of nanoplastics but necessitate stringent pretreatment and careful fouling management. MBR systems, which integrate UF membranes in sludge treatment, show excellent MP retention (>0.04 µm) but involve higher operational complexity, including continuous monitoring, cleaning, and maintenance protocols. Material selection significantly affects both capital expenditure and long-term operational costs. MF and UF membranes, such as PVDF, PES, or CA, are commercially available at moderate costs and offer robust performance. Hollow-fiber and flat-sheet configurations impact initial investment and ease of replacement, with SiC- or ZrO2-based membranes being more expensive but offering longer lifespan and higher chemical resistance, potentially reducing replacement frequency and associated downtime. An important consideration in membrane filtration is the handling of retentate or sludge streams, which concentrate MPs. MF and UF systems generate manageable sludge streams that can be integrated with existing WWTP sludge management infrastructure. In contrast, NF and RO brines contain highly concentrated nanoplastics, necessitating specialized treatment or disposal to prevent environmental release. MBRs, while highly effective at capturing MPs, produce sludge with significant MP loads (e.g., 8.11 × 103 MP/L in Italian WWTPs). This underscores the importance of robust sludge treatment strategies, such as dewatering, stabilization, or controlled incineration, to avoid secondary pollution. MF and UF membranes offer a balanced approach for large-scale water and wastewater treatment, combining high MP removal, moderate energy consumption, manageable material costs, and feasible sludge handling. NF and RO membranes are suitable for high-value water applications requiring nanoplastic removal but require careful energy and brine management due to operational complexity and higher material costs. MBR systems provide a viable solution for wastewater streams with high MP loads but necessitate advanced sludge handling infrastructure to mitigate environmental risks. In conclusion, the selection of membrane technology should carefully balance removal efficiency, energy demand, material durability, and secondary waste management. For sustainable and operationally viable implementation, MF and UF membranes are highly favorable for most water treatment scenarios, while NF, RO, and MBR systems should be reserved for specialized applications where nanoplastic removal or high MP retention is critical.

3.8. Emerging Trends and Advanced Membrane Technologies

Recent developments in membrane filtration focus on improving separation efficiency, fouling resistance, energy performance, and the removal of microplastics and micropollutants. Key advancements include nanofibrous and nanocomposite membranes, where electrospun nanofibers or nanoparticle-reinforced composites enhance water flux, mechanical robustness, and the capture of submicron contaminants [196]. Enhanced ultrafiltration (UF) membranes incorporating micellar or polymer additives have demonstrated selective removal of heavy metals, dyes, and microplastics while mitigating fouling and maintaining stable permeate fluxes [215,216].

Hybrid treatment systems that integrate dynamic membranes, membrane bioreactors, adsorption processes, and advanced oxidation processes create multi-barrier configurations capable of tackling complex mixtures of microplastics, pharmaceuticals, and other micropollutants [20,185,240,241].

Additionally, forward osmosis and pressure-retarded osmosis offer energy-efficient alternatives to reverse osmosis by utilizing osmotic gradients instead of high hydraulic pressures, making them attractive for low-energy desalination and resource recovery applications.

Surface modification strategies, such as hydrophilic, zwitterionic, and antimicrobial coatings, further enhance fouling resistance, chemical stability, and contaminant rejection by suppressing biofilm formation and reducing cleaning frequency. Emerging “smart” membranes with tuneable porosity, surface charge, and hydrophilicity provide adaptive and selective filtration, enabling dynamic responses to variations in feedwater composition and improving the targeting of specific pollutants.

Despite these promising advances, their technological readiness for real-scale deployment remains uneven. Many nanofibrous and nanocomposite membranes show excellent performance at the laboratory scale, but challenges related to large-scale manufacturing, long-term stability, nanoparticle leaching, and cost remain barriers to commercialization. Hybrid systems offer high treatment efficiency but require complex integration, higher operational expertise, and careful energy management, making them more suitable for advanced facilities than conventional plants at present. Osmotic processes (FO and PRO) continue to face limitations related to draw-solution regeneration, membrane fouling, and system scale-up. Likewise, surface-modified and smart membranes demonstrate strong potential but require further validation under realistic hydraulic, chemical, and biological stresses before widespread adoption can be achieved.

Overall, while emerging membrane technologies represent the forefront of sustainable water and wastewater treatment, most innovations still require significant pilot-scale demonstration, cost optimization, and long-term performance assessment to achieve full technological readiness for real-scale applications.

3.9. Future Outlook

Addressing microplastic pollution in aquatic environments requires focused innovation in water treatment. Future research should prioritize the development of anti-fouling, high-performance membranes with nanocomposite or functionalized surfaces to enhance flux, selectivity, and durability. The design of hybrid and multifunctional systems, integrating membrane filtration with dynamic membranes, membrane bioreactors, adsorption, or advanced oxidation processes, will enable simultaneous removal of microplastics and co-contaminants with improved energy efficiency. Incorporating sustainable resource recovery strategies, including microplastic recycling, reduced energy consumption, and minimal chemical usage, will support circular economy goals. Additionally, smart monitoring and adaptive management, leveraging sensors and AI-based tools, can optimize treatment performance and ensure consistent microplastic removal. By concentrating on these priorities, the next generation of water treatment technologies can achieve efficient, resilient, and environmentally sustainable solutions to reduce microplastic emissions and protect aquatic ecosystems.

4. Conclusions

Membrane-based technologies have proven highly effective for microplastic and micropollutant removal from water and wastewater. Membrane bioreactors and dynamic membranes exhibit superior MP retention compared with conventional activated sludge systems, combining physical filtration with biological processes or cake-layer formation to achieve removal efficiencies often exceeding 99%. Microfiltration and ultrafiltration (UF) membranes offer a practical balance of high MP removal, moderate energy demand, manageable material costs, and feasible sludge handling, making them highly suitable for large-scale implementation. Nanofiltration and reverse osmosis provide high nanoplastic removal efficiency but require higher energy input and careful brine management, while MBRs excel in high-MP-load wastewater streams but necessitate advanced sludge treatment infrastructure. Emerging trends highlight the potential of nanofibrous, nanocomposite, and surface-modified membranes to improve separation efficiency, fouling resistance, and contaminant selectivity. Hybrid systems integrating membrane filtration with DM, MBR, adsorption, and advanced oxidation processes enable multi-barrier treatment of complex wastewater streams. Smart membranes with tunable properties, forward osmosis, and pressure-retarded osmosis offer promising low-energy alternatives, although large-scale deployment and long-term stability remain challenges. In terms of the future, research should prioritize the development of anti-fouling, high-performance membranes with functionalized or nanocomposite surfaces, and the design of hybrid systems for simultaneous removal of microplastics, pharmaceuticals, and other micropollutants with optimized energy efficiency. Sustainable strategies, including microplastic recycling, minimal chemical use, and energy-efficient operation, should support circular economy goals. Smart monitoring using AI and real-time data can enhance performance, while pilot-scale validation and scale-up studies are essential to ensure operational feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and long-term stability. Focusing on these areas will enable next-generation membrane technologies to deliver efficient, resilient, and environmentally sustainable solutions for reducing microplastic pollution and protecting aquatic ecosystems. Furthermore, urgent actions are needed in urban wastewater treatment in line with the new proposal by the European Parliament and Council, which aims to reduce microplastic emissions by 9% by 2040.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.S. and P.S.S.; Resources, J.P.S., P.S.S. and H.d.P.; Data curation, J.P.S. and P.S.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.P.S. and P.S.S.; Writing—review and editing, J.P.S., P.S.S. and H.d.P.; Visualization, J.P.S., P.S.S. and H.d.P.; Supervision, H.d.P.; Project administration, H.d.P.; Funding acquisition, H.d.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Free-LitterAT project “Advancing towards litter-free Atlantic Coastal communities by preventing and reducing macro and microliter” of Interreg Atlantic Area Program, Co-Funded by European Union (2023) (https://freelitterat.eu/).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, R.; Siegler, T. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.P.; Santos, P.S.M.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. (Nano)plastics in the environment—Sources, fates and effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdogan, Z.; Guven, B. Microplastics in the Environment: A Critical Review of Current Understanding and Identification of Future Research Needs. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J.; Mikola, A.; Koistinen, A.; Setala, O. Solutions to microplastic pollution, removal of microplastics from wastewater effluent with advanced wastewater treatment technologies. Water Res. 2017, 123, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catic, I.; Cvjeticanin, N.; Galic, K.; Godec, D.; Grancaric, A.M.; Katavić, I.; Raos, P.; Rogic, A. Polimeri Od prapočetka do plastike i elastomera. Polimeri 2020, 31, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vegt, A.K. From Polymers to Plastics; Delft University Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Sazali, N.; Ibrahim, H.; Jamaludin, A.S. A short review on polymeric materials concerning degradable polymers. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 88, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šaravanja, A.; Pušić, T.; Dekanić, T. Microplastics in wastewater by washing polyester fabrics. Materials 2022, 15, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GESAMP. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment (Part 1); GESAMP: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rillig, M.C.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, T.Y.; Waldman, W. The global plastic toxicity debt. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2717–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. The Plastic Cycle—An unknown branch of the carbon cycle. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7, 609243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2588–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.C.; Rosenberg, M.; Cheng, L. Increased oceanic microplastic debris enhances oviposition in an endemic pelagic insect. Biol. Lett. 2012, 8, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.A.; Niven, S.J.; Galloway, T.S.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C. Microplastic moves pollutants and additives to worms, reducing functions linked to health and biodiversity. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2388–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Sebille, E.; Wilcox, C.; Lebreton, L. A global inventory of small floating plastic debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issac, M.N.; Balasubramanian, K. Effect of microplastics in water and aquatic systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19544–19562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C.E.; Esteban, M.A.; Cuesta, A. Microplastics in aquatic environments and their toxicological implications for fish. In Toxicology—New Aspects to This Scientific Conundrum; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016; pp. 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poerio, T.; Piacentini, E.; Mazzei, R. Membrane Processes for Microplastic Removal. Molecules 2019, 24, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, R.C.; Seeley, M.E.; La Guardia, M.J.; Mai, L.; Zeng, E.Y. A Global Perspective on Microplastics. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2020, 125, e2018JC014719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, L.J.; van Emmerik, T.; van der Ent, R.; Schmidt, C.; Lebreton, L. More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eaaz5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.P.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egessa, R.; Nankabirwa, A.; Ocaya, H.; Pabire, W.G. Microplastic pollution in surface water of Lake Victoria. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samandra, S.; Johnston, J.M.; Xie, S.; Currell, M.; Ellis, A.V.; Clarke, B.O. Microplastic contamination of an unconfined groundwater aquifer in Victoria, Australia. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 802, 149727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.A.; Arellano, J.P.; Albendín, G.; Rodríguez-Barroso, R.; Quiroga, J.M.; Coello, M.D. Microplastic pollution in wastewater treatment plants in the city of Cádiz: Abundance, removal efficiency and presence in receiving water body. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Jiang, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhong, X. Occurrence and identification of microplastics in tap water from China. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Welch, V.G.; Neratko, J. Synthetic Polymer Contamination in Bottled Water. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, S.; Wagner, M. Characterisation of nanoplastics during the degradation of polystyrene. Chemosphere 2016, 145, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, N.B.; Hüffer, T.; Thompson, R.R.; Hassellöv, M.; Verschoor, A.; Daugaard, A.E.; Rist, S.; Karlsson, T.; Wagner, M. Are We Speaking the Same Language? Recommendations for a Definition and Categorization Framework for Plastic Debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1039−1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, A.N.; Stéphan, R.G.; Zimmermann, S.; Le Coustumer, P.; Stoll, S. Contamination and removal efficiency of microplastics and synthetic fibres in a conventional drinking water treatment plant in Geneva, Switzerland. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S. The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 178, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A.I.; Hosny, M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Omar, S.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Farghali, M.; Yap, P.S.; Wu, Y.S.; Nagandran, S.; Batumalaie, K.; et al. Microplastic sources, formation, toxicity and remediation: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2129–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral-Zettler, L.; Dudas, S.; Fabres, J.; Galgani, F.; Hardesty, D.; Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Hong, S.; Kershaw, P.; Lebreton, L.; Lusher, A.; et al. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Part 2 of a Global Assessment; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016; Volume 93, p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Sundt, P.; Schulze, P.; Syversen, F. Sources of microplastic-pollution to the marine environment (MEPEX). Mepex Nor. Environ. Agency 2014, 86, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, K.K.; Eliasson, K.; Fråne, A.; Haikonen, K.; Hultén, J.; Olshamma, M.; Stadmark, J.; Voisin, A.; Stadmark, J.; Voisin, A. Swedish Sources and Pathways for Microplastic to the Marine Environment: A Review of Existing Data; IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute Report; IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A. Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Jung, S.W.; Shim, W.J. Combined effects of UV exposure duration and mechanical abrasion on microplastic fragmentation by polymer type. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 8963–8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.C.; Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Lee, J.S.; Shim, W.J. Sources of plastic marine debris on beaches of Korea: More from the ocean than the land. Ocean Sci. J. 2014, 49, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, K.; Tainosho, Y. Characterization of heavy metal particles embedded in tire dust. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jartun, M.; Pettersen, A. Contaminants in urban runoff to Norwegian fjords. J. Soils Sediments 2010, 10, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.A.; Corcoran, P.L. Effects of mechanical and chemical processes on the degradation of plastic beach debris on the island of Kauai, Hawaii. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, J.E.; Andrady, A.L. Polymer Degradation and Stability. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1989, 26, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, G.; Pettersen, A.; Nesse, E.; Eek, E.; Helland, A.; Breedveld, G.D. The contribution of urban runoff to organic contaminant levels in harbour sediments near two Norwegian cities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2008, 56, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgheib, S.; Moilleron, R.; Saad, M.; Chebbo, G. Partition of pollution between dissolved and particulate phases: What about emerging substances in urban stormwater catchments? Water Res. 2011, 45, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, C.; Baker, J.; Bamford, H. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects, and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris; University of Washington: Tacoma, WA, USA, 2009; Volumes 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, H.A. Review of Microplastics in Cosmetics: Scientific Background on a Potential Source of Plastic Particulate Marine Litter to Support Decision-Making; IVM Institute for Environmental Studies: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 476, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M.; Lambert, S. Microplastics are Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Freshwater Environments: An Overview; Wagner, M., Lambert, S., Eds.; Freshwater Microplastics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R.C. Microplastic—An emerging contaminant of potential concern? Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2007, 3, 559–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Xia, J. A review on the occurrence, distribution, characteristics, and analysis methods of microplastic pollution in ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2021, 33, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeiren, P.; Muñoz, C.; Ikejima, K. Microplastic identification and quantification from organic-rich sediments: A validated laboratory protocol. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F. Wastewater treatment works (WWTW) as a source of microplastics in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5800–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesa, F.S.; Turra, A.; Baruque-Ramos, J. Synthetic fibers as microplastics in the marine environment: A review from a textile perspective with a focus on domestic washings. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 598, 1116–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laresa, M.; Ncibi, M.C.; Sillanpää, M. Occurrence, Identification and removal of microplastic particles and fibers in conventional activated sludge process and advanced MBR technology. Water Res. 2018, 133, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Shi, H.; Peng, J. Microplastic pollution in China’s inland water systems: A review of findings, methods, characteristics, effects, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1641–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochman, C.M. Microplastics research: From sink to source. Science 2018, 360, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F. Distribution and potential health impacts of microplastics and microrubbers in air and street dusts from Asaluyeh County, Iran. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 244, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Fu, D.; Qi, H. Micro- and nano-plastics in marine environment: Source, distribution and threats—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Mason, S.; Wilson, S. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of the Laurentian great lakes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obbard, R.W.; Sadri, S.; Wong, Y.Q. Global warming releases the microplastic legacy frozen in Arctic Sea ice. Earth’s Future 2014, 2, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Liu, X. Microplastic abundance, distribution and composition in water, sediments, and wild fish from Poyang Lake, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 170, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Microplastics in agricultural soils on the coastal plain of Hangzhou Bay, east China: Multiple sources other than plastic mulching film. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 388, 121814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperi, J.; Wright, S.L.; Dris, R. Microplastics in air: Are we breathing it in? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighicellia, M.; Pietrelli, L.; Lecce, F. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of Italian Subalpine Lakes. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, S.V.; Kelly, W.R.; Scott, J. Microplastic contamination in Karst groundwater systems. Ground Water 2019, 57, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Chen, L. Microplastics in soils: A review of possible sources, analytical methods and ecological impacts. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 2052–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Stock, F.; Massarelli, C. Microplastics and their possible sources: The example of the Ofanto river in Southeast Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 258, 113284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerkes-Medrano, D.; Thompson, R.C.; Aldridge, D.C. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review of the emerging threats, identification of knowledge gaps and prioritisation of research needs. Water Res. 2015, 75, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, L.; You, S.N.; He, H. Riverine microplastic pollution in the Pearl River Delta, China: Are modelled estimates accurate? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11810–11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Krauth, T.; Wagner, S. Export of plastic debris by rivers into the sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12246–12253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]