Abstract

In vitro testing of ventricular assist devices, constructing a mock circulation system that reproduces physiological cardiac function, is critical. However, current ventricular simulators often lack biomimetic fidelity and may introduce hemolysis and coagulation risks during prolonged operation, affecting hemocompatibility assessment. This study proposes a motor-driven torsional 3D-printed left ventricular simulator to reconstruct the hemodynamics of severe heart failure and related pathological conditions. The system integrates a 3D-printed elastic ventricular model with programmable torsional actuation, allowing the simulation of various cardiac conditions by adjusting the motor torsion angle and rotational speed, peripheral resistance and compliance. Fresh porcine blood was circulated for 4 h in a closed-loop system, with periodic measurements of plasma-free hemoglobin (PfHb), thrombin–antithrombin complex (TAT), and P-selectin. The results show that the system successfully reproduces typical hemodynamic features of severe heart failure, while hemolysis and coagulation markers remain low. After 4 h, PfHb was below 20 mg/dL, with no significant platelet activation or thrombosis. This study demonstrates that the proposed system enhances biomimicry while maintaining excellent hemocompatibility, offering a reliable platform for in vitro performance and safety evaluation of ventricular assist devices.

1. Introduction

In recent years, ventricular assist devices (VADs) have made significant progress as an effective treatment for ventricular pump failure. While VADs can reduce ventricular load and improve cardiac function, clinical studies have shown that they may also cause complications such as bleeding and renal failure [1,2]. The most common complications associated with VADs are thromboembolism and hemolysis. If the mechanical circulatory support system malfunctions, it may lead to hemolysis, which can then trigger renal damage [3]. Therefore, multiple testing during the development phase is essential for optimizing and improving device performance. After the device is developed, a series of performance tests, including in vitro simulation experiments and animal model experiments, are required to ensure Safety and efficacy. While some institutions use animal experiments to test and evaluate the performance of assist pumps, this approach has obvious drawbacks, including long experimental cycles, high costs, and operational complexity [4]. Particularly in simulating severe heart failure, animal experiments are difficult to perform. Consequently, developing a highly realistic in vitro simulation system becomes crucial, as it can replicate the actual state of the human heart and vasculature [5]. Conventional left-ventricular simulators typically employ rigid chambers driven by reciprocating motors or elastic diaphragms actuated pneumatically to generate periodic pulsatile flow [6]. These systems usually provide only simplified cyclic volume changes, lack of simulation of the real heart model and torsional motion, and often rely on complex and costly mechanical components, which makes rapid adjustment to different physiological conditions difficult [7]. In reality, ventricular contraction is not a simple linear shortening process. Under normal physiological conditions, the helical arrangement of myocardial fibers causes left-ventricular contraction to be accompanied by pronounced twisting and rotational motion, analogous to wringing a towel [8]. Vignali et al. designed a pneumatically actuated left-ventricle pump for mock circulatory loops that reproduces radial deformation and twist rotation, with performance assessed via ventricular displacement and ejection fraction. Likewise, Singh et al. developed a biohybrid soft robotic right ventricle that recapitulates chamber biomechanics and hemodynamics [9]. However, improvements are still needed in terms of modularity and controllability, rapid switching of preset operating conditions, and cost. More importantly, besides hemodynamic verification such as pressure-flow waveform and EF, there is a lack of testing for blood compatibility. Building upon previous work, this study addresses the trade-off between the degree of biomimicry, control complexity, and the requirement for rapid switching among different physiological conditions in ventricular simulation systems. To this end, we developed an integrated extracorporeal circulation setup incorporating an improved left-ventricular simulator. We propose a motor-driven torsional left-ventricular simulation system for evaluating the hemodynamic performance and blood compatibility of artificial cardiac devices under extracorporeal circulation conditions. A medical-grade silicone left-ventricular chamber was fabricated by three-dimensional printing based on cardiac magnetic resonance images, and the apical region was innovatively driven to rotate around the long axis by an electric motor, thereby inducing torsional systolic deformation of the ventricular cavity and enabling more physiological ejection and filling. This design preserves essential biomimetic motion while markedly reducing overall system complexity; motion parameters can be rapidly adjusted via software control to flexibly reproduce cardiac function states ranging from normal physiology to various grades of heart failure. In this paper, we describe in detail the configuration of the proposed simulator, its actuation and control strategies, and the associated numerical simulations and experimental protocols. We further compare its deformation mechanism, control flexibility, and hemodynamic fidelity with previously reported systems, evaluate its blood-compatibility performance, and discuss current limitations and potential directions for improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Numerical Simulation Analysis

During system development, numerical simulations were employed to evaluate the structural and fluid-dynamic characteristics of the biomimetic left ventricle [10,11]. A finite-element structural model of the ventricle was constructed from cardiac MRI data using SolidWorks 2021 and was subsequently meshed in ICEM CFD (2023 R2) [12]. Two-way fluid–structure interaction (FSI) analysis was conducted in the ANSYS Workbench 2023 environment using the System Coupling module, with ANSYS FLUENT 2023 solving the fluid domain and ANSYS Mechanical 2023 solving the structural domain, while data exchange between the two solvers was managed by the System Coupling interface.

Because of the complex ventricular geometry, large deformations, and high computational cost associated with FSI, unstructured tetrahedral meshes were generated for both the fluid and structural domains. Mesh independence was assessed using three mesh resolutions (0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 million cells), which showed differences in outlet flow rate and cavity volume change of less than 5%. Therefore, a 0.6-million-cell mesh was selected as a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy. The ventricular wall was modeled using a rubber-like hyperelastic material [13].

A torsional displacement boundary condition equivalent to motor-driven apical rotation was applied to the ventricular apex, while the base was fixed. This allowed computation of the stress–strain distribution of the ventricular wall during contraction, the temporal evolution of the apical twist angle, and the corresponding volume changes. Blood properties were defined with a density of 1060 kg/m3 and a viscosity of 0.0035 Pa·s. Pressure inlet and pressure outlet conditions were imposed on the ventricular inflow and outflow boundaries, such that the deformation-induced pressure field drove blood flow. For the fluid domain, pressure-type boundary conditions were applied at the ventricular inlet and outlet. Specifically, the inflow boundary was defined as a pressure inlet representing the prescribed preload, while the outflow boundary was defined as pressure outlet. The k–ω turbulence model was adopted [14]. ANSYS Mechanical employed the finite-element method (FEM), whereas ANSYS FLUENT used the finite-volume method (FVM) to solve the transient three-dimensional Navier–Stokes equations. A time step of 0.001 s was chosen to adequately capture rapid variations in pressure and velocity fields.

2.2. Structural Design of the Simulated Circulatory System

In reality, ventricular contraction is not a simple linear shortening process. Under normal physiological conditions, the helical arrangement of myocardial fibers causes left-ventricular contraction to be accompanied by pronounced twisting and rotational motion, analogous to wringing a towel [8]. This torsional deformation plays a crucial role in enhancing systolic ejection and diastolic filling: the counter-directional rotation of the apex and base generates a torsional “torque” that augments ejection, while rapid elastic recoil in early diastole produces intraventricular negative pressure that facilitates ventricular filling.

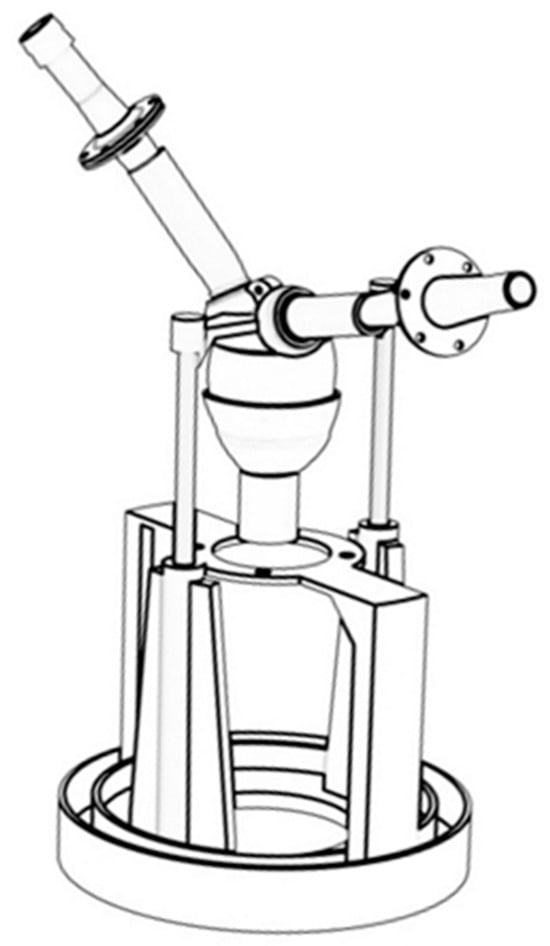

The 3D-print biomimetic left-ventricular circulation system developed in this study comprises a silicone left-ventricular model, a motor-driven actuation mechanism, valve components, peripheral resistance and compliance modules, pressure and flow sensors, and a blood-reservoir unit. To test aortic flow, the flow sensor was placed behind the compliant chamber. As shown in Figure 1, the geometry of the silicone left-ventricular chamber was reconstructed from adult cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data. Briefly, the endocardial surface was segmented from MRI, and the segmentation was exported as a surface mesh for further processing and manufacturing. The surface mesh was then smoothed and repaired to remove stair-step artifacts. The LV chamber was fabricated by direct 3D printing using medical-grade liquid silicone elastomer. The end-diastolic volume is approximately 150 mL, and the wall thickness transitions gradually according to MRI data of the human body. An attachment slot is embedded at the apical region to couple with the drive shaft, whereas the basal region is rigidly fixed. Replaceable mitral and aortic bioprosthetic valves are mounted at the inlet and outlet using custom flanges to ensure unidirectional flow and facilitate rapid replacement.

Figure 1.

Biomimetic left ventricular model and valve model.

The actuation mechanism consists of a servo motor, attachment slot, and support frame. The motor is mounted on a rigid frame, and its output shaft engages the apical slot with a clearance fit to transmit torque to the ventricular chamber. During actuation, the motor induces long-axis rotation of the apex accompanied by moderate axial displacement constrained by a linkage mechanism, resulting in combined torsional and longitudinal shortening of the elastic ventricular wall. Because the basal region is fixed, this motion generates a physiologic apex-to-base counter-twist similar to that of the native heart. By selecting appropriate motor speeds and rotation angle, the single-axis rotation is transformed into complex systolic–diastolic deformation, enabling realistic cyclic modulation of ventricular volume. Compared with conventional linear reciprocating piston mechanisms, the torsional actuation produces deformation patterns more consistent with helical myocardial contraction and promotes physiologic vortex formation and spiral outflow structures. The actuation module adopts a modular architecture, with adjustable motor mounting positions and linkage dimensions, allowing convenient replacement of ventricular chambers of different sizes and flexible adjustment of deformation amplitudes. Moreover, to ensure the comparability of the results between the simulation and the experiment, the same loading conditions were strictly maintained. In both setups, the left ventricular model was fully filled before each stroke to represent identical preload conditions, ensuring that the variations in ejection fraction (EF) were solely attributable to the changes in twist angle.

To monitor hemodynamic parameters throughout the circuit, pressure and flow sensors were installed at key locations. A pressure sensor was positioned at the ventricular outflow to record instantaneous aortic pressure, while a flow sensor placed downstream in the aortic conduit measured beat-to-beat flow waveforms. All sensor outputs were fed into a data acquisition system, enabling synchronized recording of pressure and flow over the entire cardiac cycle and supporting feedback for closed-loop control and performance evaluation.

2.3. Control Strategy and Physiological State Simulation

The control system stores predefined parameter sets corresponding to normal, mild, moderate, and severe heart failure, including target heart rate, maximum twist angle, systolic ratio, and waveform parameters. During experiments, the operator can directly activate any desired configuration, and the controller outputs the corresponding PWM signals or position trajectories to drive the motor and reproduce the target physiological state.

In organ perfusion pressure regulation [15,16], proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control is among the most widely applied algorithms. As a classic feedback strategy [17,18], PID control minimizes steady-state error and enhances dynamic response by continuously adjusting system input based on the deviation between measured and target signals. To improve pressure and torsion control accuracy, a closed-loop PI scheme was implemented in this system. Real-time ventricular pressure, twist angle, and its rate of rise were incorporated to feed peak pressure and torsional dynamics back into the controller, enabling modulation of motor amplitude and waveform. Peak left-ventricular pressure was regulated to approximately 120 mmHg in the normal state and below 80 mmHg under heart-failure conditions, with twist amplitude reduced proportionally. This closed-loop architecture compensates for disturbances such as changes in peripheral resistance, fluid viscosity, or material nonlinearities, ensuring consistent pressure–flow–torsion relationships across physiological states.

The parameters for the four main physiological states are shown in Table 1. This table summarizes the ranges of key parameters for the different simulated cardiac functional states in this system, including heart rate (HR), systolic time fraction, left-ventricular peak pressure, stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF), aortic systolic/diastolic pressure, and the corresponding maximum twist angle. As shown, under the normal condition, the EF is approximately 60%, the aortic pressure is around 120/80 mmHg, and the maximum apical twist angle approaches 90°. With progressive deterioration of cardiac function, the EF decreases to roughly 50%, 35%, and 25%, while aortic pressure is reduced to approximately 110/75, 100/70, and 80/45 mmHg, and the maximum twist angle decreases from about 60° to 45°. These trends demonstrate that the system provides a wide and physiologically consistent adjustable range in terms of pressure, flow-related indices, and torsional kinematics, enabling reliable reproduction of graded cardiac functional states.

Table 1.

Physiological parameters corresponding to the four physiological conditions.

2.4. Experimental Setup

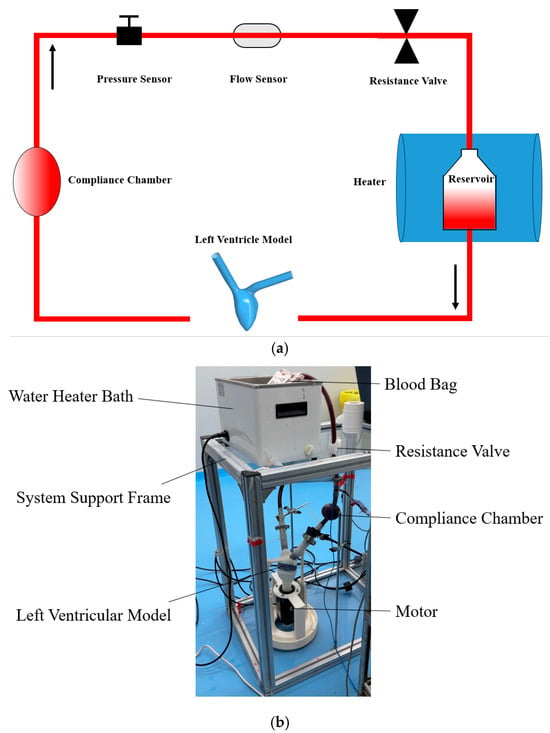

The experimental setup was designed to replicate the hemodynamics of severe heart failure and its altered states. A motor-driven biomimetic left ventricle, equipped with two bioprosthetic valves (BalMedic, Beijing, China), was used to simulate ventricular contraction. A self-designed compliant chamber was used to simulate aortic compliance. As shown in Figure 2a, the circulation loop included a pulsatile pump, tubing (“3/8” PVC tubing, Wego, Weihai, Shandong, China), a silicone compliant chamber, a water bath (Joanlab, Huzhou, Zhejiang, China), and a blood reservoir (Nigale, Chengdu, Sichuan, China). Invasive pressure sensors (Abbott type, TuoRen, Changyuan, Henan, China) were used to continuously monitor the pressure at the aortic site. The output flow from the ventricle was measured using an ultrasonic flow sensor (Transonic System, Ithaca, NY, USA), as shown in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

(a) The schematic view of the mock circulation loop; (b) the photograph of the experimental setup.

The experiments consisted of five different configurations: the static blood control group (CG, n = 3), the test condition 1 (TC1, n = 3), the test condition 2 (TC2, n = 3), the test condition 3 (TC3, n = 3), and the test condition 4 (TC4, n = 3). CG represents the condition where blood is stored in a container at the same temperature as the testing circulation blood. TC1 represents the severe heart failure condition. TC2 represents the decreased resistance condition, based on TC1 (vascular dilation symptom). TC3 represents the valve regurgitation condition, based on TC1 (aortic valve insufficiency after implanting a miniature assist pump). TC4 represents the decreased compliance condition, based on TC1 (arteriosclerosis symptom).

The experiments were conducted at Silver Snake (Shanghai, China) Biotechnology Co., and all blood samples were collected in compliance with the applicable laws and regulations approved by the ethics committee of Silver Snake (Shanghai, China) Biotechnology Co. (SHYS-No. 202509-124B). After the experiments, the samples were processed as required by the study. Fresh blood was collected from healthy large white pigs weighing approximately 59–70 kg, and stored at 4 °C to preserve the blood properties. To maintain consistent hemoglobin levels and viscosity at baseline, all blood for a particular set of experiments was sourced from the same donor pig. In each experiment, 500 mL of blood was circulated. The tests were performed at a physiological temperature of 37 °C.

2.5. Hemolysis and Coagulation Markers Measurements

Plasma-free hemoglobin (PfHb) concentration was measured to quantify hemolysis [19]. To account for differences in total hemoglobin, a hemolysis index (HI) was used to normalize PfHb levels between samples and was defined as:

where Hb denotes the PfHb concentration in whole blood (mg/L) and ΔHb represents the increase in PfHb relative to the baseline value (mg/L). Hematological parameters were obtained using a blood gas analyzer (Edan Instruments, Shenzhen, China). For PfHb measurement, 1 mL of whole blood placed in a serum-separating tube was centrifuged at 1000× g for 20 min, and the supernatant was processed using a porcine PfHb ELISA kit (Mlbio, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Rayto, Shenzhen, China), and PfHb concentration was calculated from the standard curve.

Coagulation status was evaluated by measuring plasma levels of thrombin–antithrombin complex (TAT) and P-selectin. TAT is a 1:1 complex formed between thrombin and antithrombin upon activation of the coagulation cascade and serves as a sensitive marker of coagulation activation and thrombin generation [20]. P-selectin is an important cell-adhesion molecule that is rapidly expressed on the platelet surface upon platelet activation [21]. For coagulation assays, 1 mL of whole blood was centrifuged to obtain approximately 300 μL of plasma, and porcine TAT and P-selectin ELISA kits (both from Mlbio, Shanghai, China) were used to quantify plasma TAT and P-selectin levels [22].

3. Results

3.1. Hemodynamic Performance

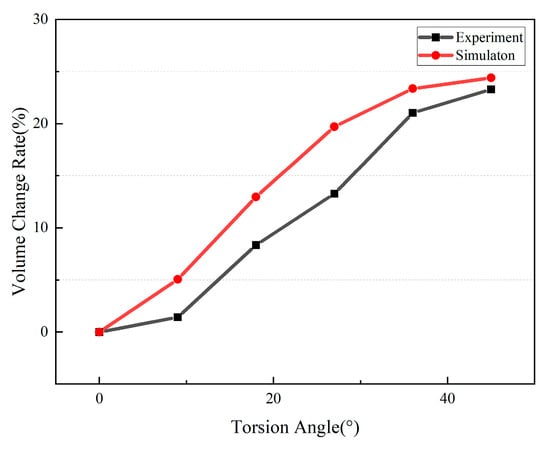

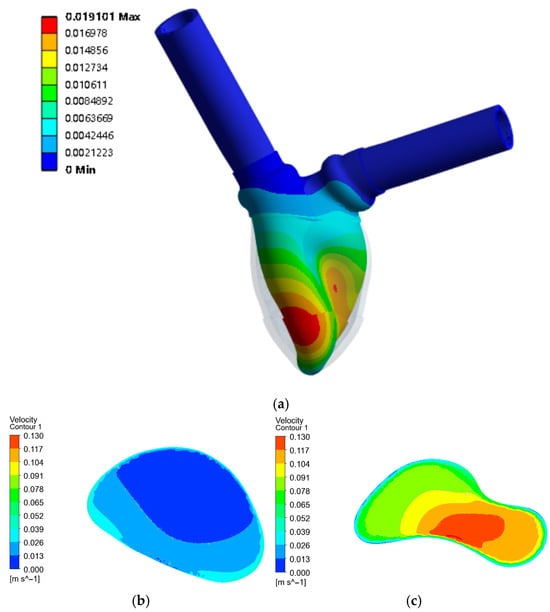

During the gradual increase in the torsion angle from 0° to 45°, the simulation and experiment results provided the ventricular volume-change ratios corresponding to different apical twist angles, as shown in Figure 3. The deformation of the simulated model and the corresponding internal flow-field contour maps are shown in Figure 4. The volume-change ratio is equivalent to the ejection fraction (EF). In the simulation, the total fluid-domain volume was measured as 216.5 mL, and after excluding the inlet and outlet segments, the effective ventricular chamber volume was approximately 155.5 mL. At an apical twist of 45° at end-systole, the ventricular volume decreased to 117.5 mL, corresponding to an EF of approximately 24.4% [23].

Figure 3.

Simulation and experimental results of the relationship between torsion angle and volume change rate.

Figure 4.

(a) Displacement of the ventricular model with 45° torsion; (b) The initial internal cross-sectional flow field; (c) The internal cross-sectional flow field with 45° torsion.

Compared with the target experimental condition corresponding to severe heart failure, the simulation suggested that an apical twist angle of 45° would be appropriate for experimental replication. In the experimental setup, the end-diastolic chamber volume was set to 150 mL, and the measured end-systolic volume was approximately 115 mL, yielding an EF of about 23.3%. This condition was therefore used to simulate severe heart failure (target EF ≈ 25%).

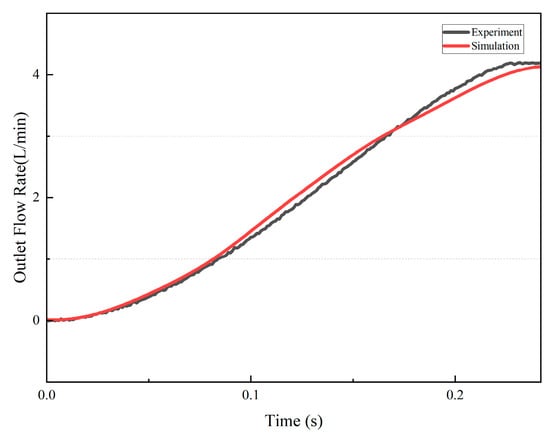

Under this condition, the simulated outlet flow waveform and volume-change curve were obtained and compared with the corresponding experimental measurements, as shown in Figure 5. The two profiles demonstrated close agreement. These results confirm the reliability of the simulation framework in reproducing torsion-induced ventricular dynamics.

Figure 5.

Simulation and experimental results of the outlet flow rate.

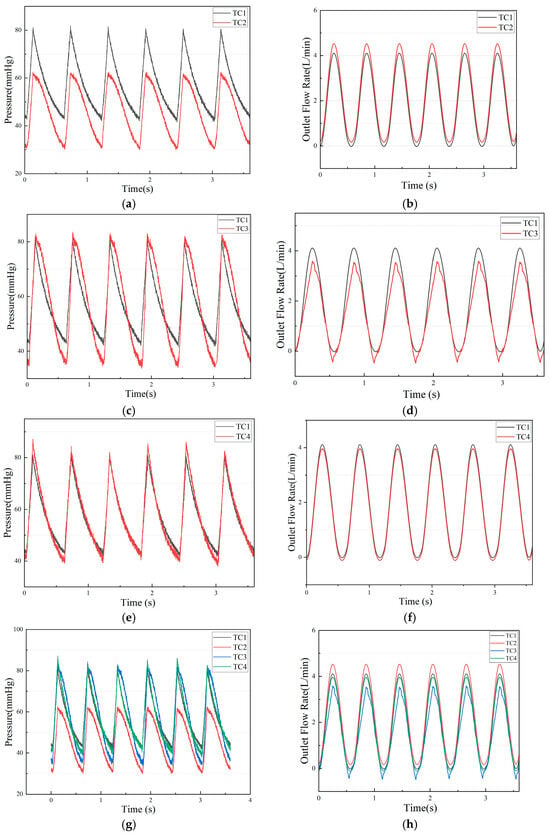

Test condition 1 (stage SEVERE heart failure): The extracorporeal simulation system successfully reproduced pressure and flow waveforms close to those of adult patients with severe heart failure. The peak left-ventricular systolic pressure was about 80 mmHg and the diastolic pressure was about 45 mmHg (80/45 mmHg), with a mean aortic pressure of about 63 mmHg. The peak flow rate during ejection was about 4 L/min, and the aortic flow was about 2.0 L/min.

Test condition 2 (decreased resistance): On the basis of test condition 1, the resistance valve was adjusted to simulate a physiological state of reduced resistance (vasodilation). As expected, the mean aortic pressure decreased; opening the resistance valve reduced peripheral resistance, causing the aortic pressure under the same heartbeat to fall to 30–60 mmHg, while the aortic flow slightly increased to 2.2 L/min.

Test condition 3 (valve regurgitation): On the basis of test condition 1, the aortic valve with incomplete closure was installed. As expected, the mean aortic pressure slightly decreased to 35–80 mmHg, and the aortic flow decreased to 1.6 L/min.

Test condition 4 (decreased compliance): On the basis of test condition 1, the size of the compliance chamber was adjusted to simulate a physiological state of reduced compliance. The aortic pressure became 40–85 mmHg, and the aortic flow slightly decreased to 1.8 L/min.

Pressure and flow rate under TC1, TC2, TC3, TC4, and the comparison are shown as Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(a) The experimental pressure of TC1 and TC2; (b) The experimental flow rate of TC1 and TC2; (c) The experimental pressure of TC1 and TC3; (d) The experimental pressure of TC1 and TC3; (e)The experimental pressure of TC1 and TC4; (f) The experimental pressure of TC1 and TC4; (g) The experimental pressure of TC1, TC2, TC3 and TC4; (h) The experimental pressure of TC1, TC2, TC3 and TC4.

3.2. Hemolysis-Related Results

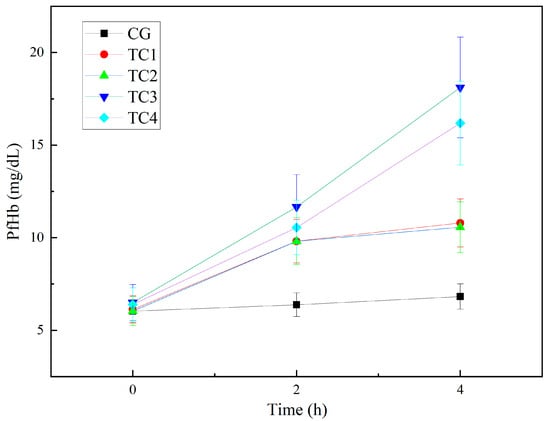

The PfHb results for the control and test conditions are shown in Figure 7. Because rupture of red blood cells releases hemoglobin, the concentration of PfHb is an important indicator of hemolysis [19]. In TC1, TC2, TC3, and TC4, PfHb concentration increased with prolonged circulation time. Compared with CG, the PfHb concentrations in TC1, TC2, TC3, and TC4 were markedly elevated at 120 and 240 min, and at 240 min, the PfHb concentration in TC3 was the highest.

Figure 7.

Experimental results of changes in plasma-free hemoglobin. CG: control group; TC1: test condition 1 (severe heart failure); TC2: test condition 2 (severe heart failure with reduced flow resistance); TC3: test condition 3 (severe heart failure with regurgitation); TC4:test condition 4 (severe heart failure with reduced compliance).

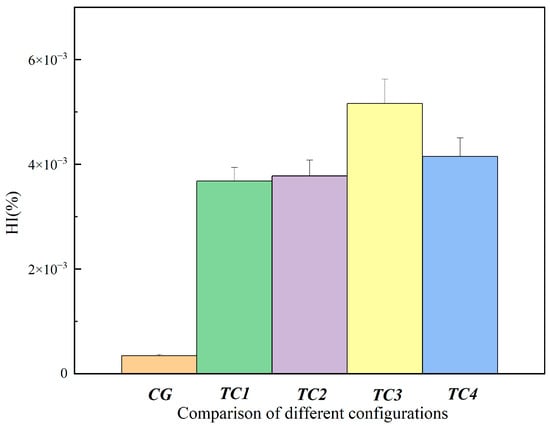

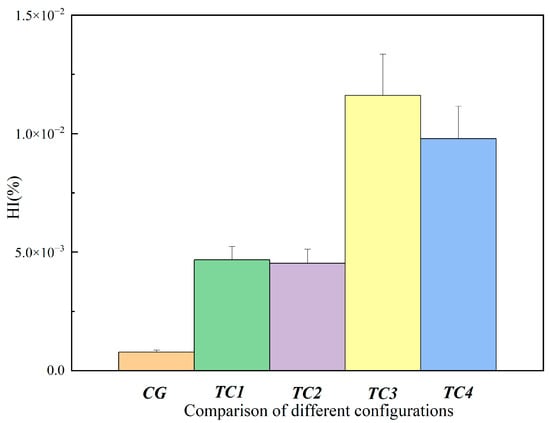

According to the experimental hemolysis index results shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, the hemolysis index (HI) exhibited clear differences among the various test conditions. Compared with the CG control group, the HI values in TC1, TC2, TC3, and TC4 were all increased, with TC3 and TC4 being notably higher than the other conditions. This indicates that the extent of blood damage increased as different pathological states were simulated. Among them, the HI under TC3 and TC4 was significantly higher than under TC1 and TC2. In particular, under TC3 and TC4, blood damage tended to worsen over time, which may be related to higher shear stress and increased flow instability [24]. However, overall, the level of blood damage in all conditions remained relatively low and was consistent with the expectations of the experiment.

Figure 8.

Comparison of hemolysis index between the control group and test conditions at 120 min. CG: control group; TC1: test condition 1 (severe heart failure); TC2: test condition 2 (severe heart failure with reduced flow resistance); TC3: test condition 3 (severe heart failure with regurgitation); TC4: test condition 4 (severe heart failure with reduced compliance).

Figure 9.

Comparison of hemolysis index between the control group and test conditions at 240 min. CG: control group; TC1: test condition 1 (severe heart failure); TC2: test condition 2 (severe heart failure with reduced flow resistance); TC3: test condition 3 (severe heart failure with regurgitation); TC4: test condition 4 (severe heart failure with reduced compliance).

3.3. Coagulation-Related Results

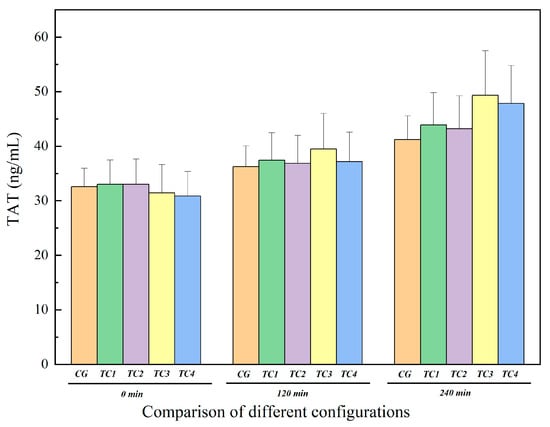

The TAT results for control and test conditions are shown in Figure 10. The TAT concentrations in TC1, TC2, TC3, and TC4 also gradually increased over time. At 120 min and 240 min, the TAT levels in TC1, TC2, TC3, and TC4 were higher than those in CG. During the experiment, the increase in TAT concentration was most pronounced in TC3, especially at 240 min, where the TAT level in TC3 was clearly higher than in TC1 and TC2, suggesting an increased risk of thrombosis under regurgitation conditions.

Figure 10.

Comparison of TAT levels between the control group and test groups. CG: control group; TC1: test condition 1 (severe heart failure); TC2: test condition 2 (severe heart failure with reduced flow resistance); TC3: test condition 3 (severe heart failure with reduced compliance); TC4: test condition 4 (severe heart failure with increased temperature).

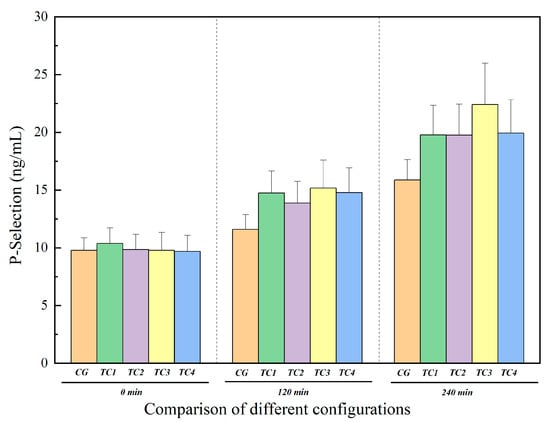

The P-selectin results for control and test conditions are shown in Figure 11. Similarly to TAT, the P-selectin concentrations in TC1, TC2, TC3, and TC4 also gradually increased over time, and at 120 min and 240 min, the P-selectin levels in all test conditions were markedly higher than in CG, indicating progressive activation of the coagulation system during continuous circulation. The increase in P-selectin concentration at 240 min was most evident in TC3, indicating that more platelets were activated under regurgitation conditions.

Figure 11.

Comparison of P-selectin levels between the control group and test groups. CG: control group; TC1: test condition 1 (severe heart failure); TC2: test condition 2 (severe heart failure with reduced flow resistance); TC3: test condition 3 (severe heart failure with reduced compliance); TC4: test condition 4 (severe heart failure with increased temperature).

In summary, the experimental results show that, under all test conditions, TAT and P-selectin concentrations increased significantly with prolonged circulation time, with a higher degree of coagulation activation and platelet activation in TC3, which may be associated with an elevated risk of thrombosis. However, overall, the absolute levels of these two indicators remained relatively low and were consistent with the expectations of the experiment.

4. Discussion

This study analyzes the time-dependent changes in PfHb, HI, TAT, and P-selectin to characterize the accumulation patterns of blood damage under heart-failure conditions. As circulation time increases, blood repeatedly passes through regions of elevated local shear stress within the loop, exposing red blood cells and platelets to recurrent mechanical stimulation. Accordingly, hemolysis- and coagulation-related biomarkers exhibit a slow and progressive rise, consistent with the well-recognized “shear-time cumulative effect” [25] in extracorporeal circulation: even when overall shear levels are not extreme, prolonged exposure under moderate shear conditions can still lead to measurable cellular damage and activation. Based on the absolute values and comparisons across conditions, the increases observed in hemolysis and coagulation markers remain mild, and the differences between experimental conditions fall within a reasonable range, indicating that the system does not introduce additional sources of blood trauma during long-duration operation [26].

From the standpoint of device design, the extracorporeal mock circulation system used in this work incorporates multiple structural and functional features that help minimize blood damage. Firstly, the ventricular part of the device is 3D printed based on the real heart, maximizing the reproduction of the authentic ventricular structure, and both the tubing diameter and circuit layout are optimized to meet the pressure and flow demands of severe heart failure and its variants while avoiding abrupt diameter changes or sharp bends that may generate regions of high shear and strong vortices. Second, key components such as the ventricular chamber and compliance chamber are made from elastic silicone. In combination with the adjustable resistance valve and compliance chamber, the system produces pressure and flow waveforms that are highly controllable across different pathological states, satisfying target hemodynamic conditions without inducing pressure oscillations or overshoot, thereby reducing mechanical blood trauma.

Across all four simulated circulation conditions, blood-damage-related indicators showed a degree of time-dependent increase. Plasma-free hemoglobin (PfHb) rose gradually over the 4 h circulation period, which aligns with the expected cumulative red-cell damage caused by prolonged exposure to shear forces [27]. Because red blood cell rupture releases intracellular free hemoglobin, PfHb is widely regarded as an important quantitative marker for assessing hemolysis [3,4]. The corresponding hemolysis index (HI) followed a similar pattern. In cardiac perfusion applications, the use of red blood cells as the circulating fluid inherently carries a certain degree of hemolysis, and sustained elevation of PfHb can contribute to microcirculatory dysfunction [6]. In this study, even under the most demanding conditions at 4 h, PfHb did not exceed 20 mg/dL, remaining far below the commonly cited threshold of 40 mg/dL associated with hemolysis risk [28] and substantially lower than the 50–100 mg/dL range corresponding to moderate hemolysis [29]. Meanwhile, coagulation-related markers such as P-selectin and TAT exhibited only mild increases and stayed within low ranges overall, indicating that neither extensive platelet activation nor amplification of the coagulation cascade occurred. Taken together, although hemolysis and coagulation markers accumulated gradually with time under the tested conditions, they consistently remained within safe low-value ranges, demonstrating that the device and its operational parameters exert only minimal impact on blood integrity and achieve effective blood protection during extracorporeal simulation.

Further comparison of the present results with publicly reported data from clinically used blood pumps highlights the blood-compatibility advantage of the proposed system. In real mechanical circulatory support, many blood pumps induce substantially higher levels of hemolysis and coagulation activation. For example, hemolysis monitoring is essential during clinical use of the Impella micro-axial pump. In vitro study, the hemolysis index for the Impella CP was approximately 2.78 ± 0.69 under ideal placement, but increased to 18.7 ± 7.8 when the inlet was partially obstructed (simulating malposition), representing a six-fold elevation [30], indicative of significant hemolysis risk under non-ideal conditions [13]. In addition, the Impella 5.5 has been reported to cause PfHb elevation exceeding 40 mg/dL within 4 h of testing [31]. Although the next-generation LVAD HeartMate 3—with its fully magnetically levitated rotor, widened flow gaps, and artificial pulsatility—greatly improves hemocompatibility and has demonstrated near-zero hemolysis and pump thrombosis over one-year follow-up, patients still require long-term anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy to mitigate thrombotic risk [32]. Similarly, centrifugal pumps used in ECMO circuits (e.g., CentriMag) may induce platelet activation and trigger the coagulation cascade at high speeds and pressures; studies have reported that elevated shear forces inside the pump increase the risk of thrombosis and bleeding complications [33], with higher pump power often associated with increased thrombotic events [34]. Collectively, these findings indicate that the system introduces minimal disturbance to the hemorheological environment and maintains hemocompatibility superior to that of many clinical blood pumps. Based on the data above, it can be inferred that the blood damage caused by the in vitro simulated circulatory system is lower than that caused by many clinical pumps. This system can provide a controllable, repeatable, and baseline simulated circulatory device with a blood damage level that does not exceed the clinically relevant range, supporting the evaluation and iterative development of interventional pumps and related flow devices.

5. Conclusions

This study established an extracorporeal mock circulation system for severe heart failure and several common pathological conditions, and systematically examined changes in plasma free hemoglobin (PfHb) and coagulation-related markers, including TAT and P-selectin, over a 4 h circulation period. The system incorporates key biomimetic features of the left ventricle in both structural and kinematic design by reproducing realistic ventricular geometry and torsional contraction patterns, and allows fine adjustment of heart rate, compliance, and resistance. In this way, pressure and flow waveforms under severe heart failure and typical intervention scenarios can be reconstructed with high fidelity, and parameters such as stroke volume and ejection fraction closely match clinical values. The results show that, under all test conditions, these hemolysis- and coagulation-related indicators exhibit only a gradual increase over time and remain at low absolute levels, not reaching the ranges associated with clinically relevant hemolysis or hypercoagulability. This indicates that the device maintains good hemocompatibility while providing high biomimicry and precise parameter control, even when simulating severe cardiac dysfunction and multiple hemodynamic intervention settings.

Limitation: There is a risk of fatigue damage when the silicone 3D-printed left ventricular model operates for more than 24 h. To address the limitation concerning the operational lifespan of the ventricular model, future research will focus on a multi-faceted mitigation strategy. This includes the optimization of the ventricle’s structural geometry to reduce stress concentration and the adoption of advanced biocompatible materials with superior fatigue resistance. As the final application of this device is an in vitro testing platform for interventional pumps, which typically requires a stable operating duration of over 24 h, these improvements will be critical for facilitating prolonged performance evaluations. A further limitation is the use of porcine blood as a surrogate for in vitro hemocompatibility testing. Although porcine blood is commonly adopted in benchtop circulation-loop studies, interspecies differences in platelet reactivity/activation potential and other hemostatic characteristics have been reported, which may influence the absolute levels of coagulation- and platelet-related biomarkers and limit direct extrapolation to human safety. Future work will validate the key findings using fresh human blood (with clinically relevant anticoagulation and hematocrit control) and expanded sample size.

Author Contributions

Q.C. and J.M. contributed equally to this paper, Conceptualization, Q.C., M.Y., Y.L. and J.M.; methodology, Q.C., M.Y., Y.L., Y.Z. and J.M.; software, Q.C. and J.M.; validation, Q.C., M.Y., J.M., J.Y. and H.G.; formal analysis, Q.C., M.Y. and J.M.; investigation, Q.C., J.M. and Y.L.; data curation, Q.C. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.C.; writing—review and editing, Q.C., J.M., M.Y. and Y.L.; project administration, M.Y.; funding acquisition, M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, grant 2022YFC2402601.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Silver Snake (Shanghai, China) Biotechnology Co (protocol code SHYS-No. 202509-124B and 3 October 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nakamura, M.; Imamura, T.; Hida, Y.; Kinugawa, K. Pulmonary Artery Pulsatility Index and Hemolysis during Impella-Incorporated Mechanical Circulatory Support. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attinger-Toller, A.; Bossard, M.; Cioffi, G.M.; Tersalvi, G.; Madanchi, M.; Bloch, A.; Kobza, R.; Cuculi, F. Ventricular Unloading Using the ImpellaTM Device in Cardiogenic Shock. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 856870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leick, J.; Grottke, O.; Oezkur, M.; Mangner, N.; Sanna, T.; Al Rashid, F.; Vandenbriele, C. What Is Known in Pre-, Peri-, and Post-Procedural Anticoagulation in Micro-Axial Flow Pump Protected Percutaneous Coronary Intervention? Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2022, 24, J17–J24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappon, F.; Wu, T.; Papaioannou, T.; Du, X.; Hsu, P.-L.; Khir, A.W. Mock Circulatory Loops Used for Testing Cardiac Assist Devices: A Review of Computational and Experimental Models. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2021, 44, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwinger, R.H.G. Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2021, 11, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baturalp, T.B.; Bozkurt, S. Design and Analysis of a Polymeric Left Ventricular Simulator via Computational Modelling. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Thai, M.T.; Sharma, B.; Hoang, T.T.; Nguyen, C.C.; Phan, P.T.; Vuong, T.N.A.M.; Ji, A.; Zhu, K.; Nicotra, E.; et al. Soft Robotic Artificial Left Ventricle Simulator Capable of Reproducing Myocardial Biomechanics. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eado4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Fan, Y.; Hager, G.; Yuk, H.; Singh, M.; Rojas, A.; Hameed, A.; Saeed, M.; Vasilyev, N.V.; Steele, T.W.J.; et al. An Organosynthetic Dynamic Heart Model with Enhanced Biomimicry Guided by Cardiac Diffusion Tensor Imaging. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eaay9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Bonnemain, J.; Ozturk, C.; Ayers, B.; Saeed, M.Y.; Quevedo-Moreno, D.; Rowlett, M.; Park, C.; Fan, Y.; Nguyen, C.T.; et al. Robotic Right Ventricle Is a Biohybrid Platform That Simulates Right Ventricular Function in (Patho)Physiological Conditions and Intervention. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 2, 1310–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, K.H.; Taskin, M.E.; Griffith, B.P.; Wu, Z.J. The Use of Computational Fluid Dynamics in the Development of Ventricular Assist Devices. Med. Eng. Phys. 2011, 33, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, C.; Hao, P.; He, F.; Zhang, X. Full-Scale Numerical Simulation of Hemodynamics Based on Left Ventricular Assist Device. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1192610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, T.; Malve, M.; Reik, M.; Markl, M.; Jung, B.; Oertel, H. MRI-Based CFD Analysis of Flow in a Human Left Ventricle: Methodology and Application to a Healthy Heart. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 37, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comunale, G.; Di Micco, L.; Boso, D.P.; Susin, F.M.; Peruzzo, P. Numerical Models Can Assist Choice of an Aortic Phantom for In Vitro Testing. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameneva, M.V.; Burgreen, G.W.; Kono, K.; Repko, B.; Antaki, J.F.; Umezu, M. Effects of Turbulent Stresses on Mechanical Hemolysis: Experimental and Computational Analysis. In American Society for Artificial Internal Organs (ASAIO) Platinum 70th Anniversary Special Edition; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, L.; Yao, W.; Peng, Y.; Qi, N.; Xie, S.; Ru, C.; Badiwala, M.; Sun, Y. Model Reference Adaptive Control for Aortic Pressure Regulation in Ex Vivo Heart Perfusion. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2021, 29, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-H.; Lee, B.; Hong, J.; Yang, T.-H.; Park, Y.-H. Reproduction of Human Blood Pressure Waveform Using Physiology-Based Cardiovascular Simulator. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Bai, Y.; Du, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X. Resistance Valves in Circulatory Loops Have a Significant Impact on in Vitro Evaluation of Blood Damage Caused by Blood Pumps: A Computational Study. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1287207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou, C.A.; Kyriakoulis, K.G.; Theochari, C.A.; Kokkinidis, D.G.; Karamitsos, T.D.; Palaiodimos, L. Comprehensive Review of Hemolysis in Ventricular Assist Devices. World J. Cardiol. 2020, 12, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, P.; Winnersbach, P.; Kraemer, S.; Beckers, C.; Buhl, E.; Leonhardt, S.; Rossaint, R.; Walter, M.; Breuer, T.; Bleilevens, C. Comparison of the Hemocompatibility of an Axial and a Centrifugal Left Ventricular Assist Device in an In Vitro Test Circuit. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richtrova, P.; Mares, J.; Kielberger, L.; Trefil, L.; Eiselt, J.; Reischig, T. Citrate-Buffered Dialysis Solution (Citrasate) Allows Avoidance of Anticoagulation During Intermittent Hemodiafiltration—At the Cost of Decreased Performance and Systemic Biocompatibility. Artif. Organs 2017, 41, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.M.; Ahmad, S.; Walenga, J.M.; Hoppensteadt, D.A.; Leitz, H.; Fareed, J. Soluble P-Selectin in Human Plasma: Effect of Anticoagulant Matrix and Its Levels in Patients with Cardiovascular Disorders. Clin. Appl. Thromb. 2000, 6, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, M. The Impact of Transient Control Performance of Pulsatile Flow on Hemolysis and Coagulation in ex vivo Heart Perfusion. Artif. Organs 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.S.P.; Solomon, S.D. Classification of Heart Failure According to Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 3217–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.; Wen, B.; Xie, Q.; Dai, M. Real-Time Regurgitation Estimation in Percutaneous Left Ventricular Assist Device Fully Supported Condition Using an Unscented Kalman Filter. Physiol. Meas. 2024, 45, 055001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faghih, M.M.; Craven, B.A.; Sharp, M.K. Practical Implications of the Erroneous Treatment of Exposure Time in the Eulerian Hemolysis Power Law Model. Artif. Organs 2023, 47, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Mondal, N.K.; Zheng, S.; Koenig, S.C.; Slaughter, M.S.; Griffith, B.P.; Wu, Z.J. High Shear Induces Platelet Dysfunction Leading to Enhanced Thrombotic Propensity and Diminished Hemostatic Capacity. Platelets 2019, 30, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; Fu, H.; Lu, Z.; Yang, M. Impact of Impeller Speed Adjustment Interval on Hemolysis Performance of an Intravascular Micro-Axial Blood Pump. Micromachines 2024, 15, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, A.; Deng, X.; Chen, Z.; Fan, Y. Multi-Method Investigation of Blood Damage Induced by Blood Pumps in Different Clinical Support Modes. ASAIO J. 2024, 70, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Petersdorff-Campen, K.; Schmid Daners, M. Hemolysis Testing In Vitro: A Review of Challenges and Potential Improvements. ASAIO J. 2022, 68, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.; Chandrasekaran, U.; Das, S.; Qi, Z.; Corbett, S. Hemolysis Associated with Impella Heart Pump Positioning: In Vitro Hemolysis Testing and Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2020, 43, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roka-Moiia, Y.; Li, M.; Ivich, A.; Muslmani, S.; Kern, K.B.; Slepian, M.J. Impella 5.5 Versus Centrimag: A Head-to-Head Comparison of Device Hemocompatibility. ASAIO J. 2020, 66, 1142–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krabatsch, T.; Netuka, I.; Schmitto, J.D.; Zimpfer, D.; Garbade, J.; Rao, V.; Morshuis, M.; Beyersdorf, F.; Marasco, S.; Damme, L.; et al. Heartmate 3 Fully Magnetically Levitated Left Ventricular Assist Device for the Treatment of Advanced Heart Failure—1 Year Results from the Ce Mark Trial. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. The Influence of Different Operating Conditions on the Blood Damage of a Pulsatile Ventricular Assist Device. ASAIO J. 2015, 61, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, D.T.; Pietsch, C.; Topalovic, N.; Hofmann, M.; Schmiady, M.O.; Weisskopf, M.; Schmid Daners, M. Preliminary in Vitro Hemolysis Evaluation of MR-Conditional Blood Pumps. Front. Med. Technol. 2025, 7, 1671938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.