Featured Application

This study highlights the proven need to apply complementary methods—genetic prediction and slide agglutination—for reliable identification of rare or atypical Salmonella serovars.

Abstract

Salmonella is a globally important pathogen and one of the World Health Organization and One Health priority organisms. Reptiles represent environmental reservoirs of Salmonella serovars that can cause reptile-associated salmonellosis (RAS) in humans. Due to distinct biochemical features and uncommon O and H antigen variants, reptile-associated isolates may be difficult to identify using standard microbiological diagnostics. This study analyzed 62 Salmonella isolates obtained from wild and kept snakes in Poland. Samples originated from Natrix natrix, N. tessellata, Coronella austriaca, Zamenis longissimus, Elaphe dione and Nerodia fasciata species. Serovar prediction using SeqSero1.2 was compared with classical slide agglutination. Seventeen serovars were confirmed, with S. enterica subsp. diarizonae (IIIb) 38:r:z being the most frequent. For seven isolates, molecular and serological results were inconsistent. Among three isolates from Coronella austriaca predicted as IIIb 38:z10:z50, three distinct second-phase flagellar phenotypes were detected. Slide agglutination confirmed the presence of serovar 38:z10:z6, which has not been previously listed in the White–Kauffmann–Le Minor scheme or described in the scientific literature. The findings highlight the utility of genetic serovar prediction while emphasizing the need for continuous validation, particularly for the identification of rare or atypical Salmonella serovars associated with reptiles.

1. Introduction

Salmonella spp. are Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae within the order Enterobacterales. The genus Salmonella is divided into two species, Salmonella enterica and Salmonella bongori, of which only S. enterica has a significant impact on public health due to its wide host range and pathogenic potential [1,2,3,4]. Environmental reservoirs of Salmonella spp. are mainly associated with the intestinal microbiota of animals such as birds, rodents, and reptiles, regardless of whether they are wild or kept in captivity [2]. Nontyphoidal Salmonella (NTS) serovars represent a group of zoonotic pathogens responsible for foodborne infections worldwide [5]. Among them, S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium are among the serovars most frequently associated with human salmonellosis [3,4]. The importance of these pathogens has been highlighted by the One Health initiative and the World Health Organization (WHO), which classify fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella as high-priority microorganisms for antimicrobial research and monitoring [6].

Reptiles play a significant role in the epidemiology of salmonellosis, as their microbiota constitutes a natural reservoir of Salmonella [7,8,9]. Salmonellosis most often manifests as a self-limiting gastrointestinal infection. However, reptile-associated salmonellosis (RAS) represents a distinct form of nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Human infection may occur through both direct and indirect contact with reptiles or their environment. In some cases, RAS can develop into extraintestinal disease, leading to severe conditions such as meningitis, necrosis and sepsis. RAS often requires hospitalization and, in rare cases, may result in death [10,11,12,13].

Biochemical and proteomic identification assays are generally sufficient for the identification of most Enterobacterales [14,15,16,17,18]. However, due to their limitations, serovar determination is required for the full identification of Salmonella. High antigenic variability is a characteristic feature of the genus Salmonella. To date, more than 2600 serovars have been described and differentiated according to the Kauffmann–White–Le Minor scheme and its subsequent supplements [19,20]. The majority of Salmonella serovars belong to the species S. enterica and are associated with zoonotic infections in humans. Serovar diversity arises from structural variations in the somatic O antigen (O-Ag), which is a part of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the flagellar component (H antigen, H-Ag) [19]. Accurate characterization of these antigens is essential for the complete identification of Salmonella isolates. Serovar identification is routinely performed using the slide agglutination method [21]. The variation among serovars is directly linked to the sequences of genes responsible for the biosynthesis of these surface structures. The rfb gene cluster primarily determines O-Ag variation, whereas fliC gene encodes the phase 1 flagellin (H1-Ag) and fljB gene encodes the phase 2 flagellin (H2-Ag) [22,23]. Due to the extensive diversity and variability of O and H antigens in Salmonella, serotyping of rare variants requires access to, validation of, and maintenance of a large collection of polyvalent and monovalent antisera. A practical alternative is to predict the serovar based on genetic sequences, an approach that has been increasingly and successfully reported in recent studies [24].

Against this background, the aim of this study was to evaluate the usefulness of genetic serovar prediction for exotic Salmonella isolates originating from selected species of wild and captive snakes in Poland. The accuracy of genetic prediction was compared with the results of the classical slide agglutination method, which remains the routine diagnostic approach for Salmonella serotyping in microbiological laboratories.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

A total of 62 Salmonella isolates from Poland were included in this study. The isolates originated from cloacal swabs from wild snakes (Natrix natrix, NN, n = 30; N. tessellata, NT, n = 15; Coronella austriaca, CA, n = 6; Zamenis longissimus, ZL, n = 2) and kept snakes (Nerodia fasciata, NF, n = 3; Elaphe dione, ED, n = 6). All isolates were obtained in previous research activities, confirmed as Salmonella and deposited in the resources of the Department of Microbiology, University of Wrocław, and in the Polish Collection of Microorganisms (PCM) and characterized earlier for antibiotic resistance and virulence factors [17,25].

2.2. DNA Isolation and Whole Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using the GeneMATRIX Bacterial & Yeast Genomic DNA Purification Kit (EURx, Gdansk, Poland, cat. no. E3580) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration was assessed on a 1% agarose gel in TAE buffer (EURx) against the Qubit dsDNA HS Standard #2 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and samples were diluted in nuclease-free water (EURx) to a final concentration of 15 ng/µL. DNA was stored at 4 °C for up to two days for immediate analyses and subsequently at −20 °C until use. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed with Oxford Nanopore Technology. DNA libraries were prepared with the Rapid Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-RBK144, Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) following the manufacturer’s protocol, in which 150 ng of genomic DNA was fragmented and barcoded using transposase. Barcoded samples were multiplexed, adapter-ligated, and sequenced on a MinION™ Mk1B device using a MinION Flow Cell R10.4.1 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Raw sequencing data were basecalled with Dorado v0.9.1 using the high-accuracy (HAC v5.0.0) model. FASTQ reads were demultiplexed based on barcode sequences, and genome assemblies were generated with Flye v2.9.5-b1801 using default parameters for Nanopore data (-nano-raw) and saved in FASTA format. The completeness and contamination of the assembled genomes were assessed using CheckM2 1.1.0 with version 3 of the database (10.5281/zenodo.14897628) [26]. The quality of the genomic reads was checked using NanoStat 1.6.0. Chromosome coverage was calculated using Flye, based on the coverage values of the longest contigs in the samples.

2.3. Genetic Prediction of Salmonella Serovars

Salmonella serovars were determined based on characteristic genomic loci. The web-based tool SeqSero1.2 was used to predict the Salmonella antigenic formula (https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/SeqSero, accessed on 20 November 2025). The tool analyzes sequence variability within the rfb cluster for typing of the somatic O-Ag and the fliC and fljB alleles for the first and second phases of the H-Ag [27]. Genome assemblies in FASTA format were annotated using Prokka (Prokaryotic genome annotation, Galaxy v1.14.6+galaxy1) employing default parameters [28,29]. To further validate the presence of selected antigen-coding genes, pairwise nucleotide sequence alignments were performed using BLASTn (BLAST+ v2.17.0) implemented in the NCBI BLAST web interface (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 20 November 2025), applying the megablast algorithm optimized for highly similar sequences and default parameters. The predicted serovars were subsequently compared with classical serotyping by slide agglutination.

2.4. Slide Agglutination

Slide agglutination serotyping was performed according to ISO/TR 6579-3: Microbiology of the food chain—Horizontal method for the detection, enumeration and serotyping of Salmonella—Part 3: Guidelines for serotyping of Salmonella spp. [21]. Slide agglutination serotyping was performed to confirm the genetic predictions of the serovars. Before the assay, a control agglutination in a drop of 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl) suspension was performed to evaluate potential autoagglutination of the strains. The determination of O-Ag was performed during an earlier phase of the study and has been previously published; however, the full antigenic formulas were not included in that publication [25]. Briefly, typing of the somatic O-Ag was carried out using fresh cultures grown on Nutrient Agar (Biomaxima, Lublin, Poland) for 18 ± 2 h at 37 °C. For each reaction, 2–3 Salmonella colonies were suspended in a drop of the tested antiserum. Since none of the analyzed strains carried the Vi antigen, masking of O-Ag epitopes did not occur and heat treatment was not necessary.

Inocula for flagellar antigen serotyping were obtained from Schwörm agar (SSI Diagnostica, Hillerød, Denmark), which promotes flagellar motility. For isolates expressing biphasic flagella, inhibition of the H1 phase was made by supplementing the Schwörm agar with 200 µL of H1-specific antiserum during plate preparation what allowed the expression and subsequent identification of the H2 antigen. H-Ag serotyping was carried out using commercially available H-specific antisera, including H:1, H:5, H:e, H:l, H:n, H:x H:z10, H:z13, H:z15, H:z28, H:z35, and H:z4,z23 (Sifin, Berlin, Germany); H:7, H:k, H:v, H:z and H:z6 (Biomed, Kraków, Poland) and H:r (Immunolab, Gdańsk, Poland).

3. Results

All Salmonella genomes (N = 62) were confirmed by CheckM2 analysis to be 100% complete with low contamination (≤5%) and were therefore included in subsequent analyses. Additional read and genome statistics are provided in the Supplementary Material as Figures S1.1 and S1.2.

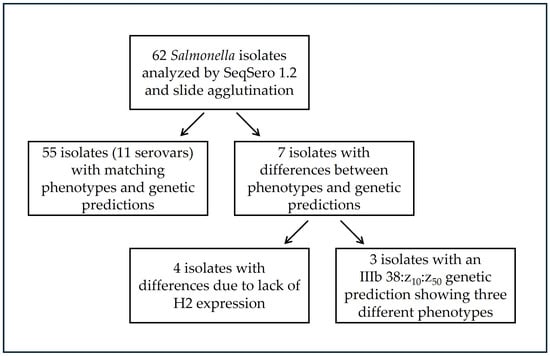

For all isolates the antigenic formula was successfully determined. In total, 17 serovars were genetically predicted among the Salmonella isolates obtained from snakes. For most isolates, consistent results were obtained between genetic serovar prediction using SeqSero1.2 and conventional slide agglutination (n = 55/62), as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of phenotypic and genetic serovar identification for tested isolates (N = 62).

Eleven of the detected serovars (11/17; 64.7%) showed complete agreement between the two methods (Table 1). The majority of isolates belonged to S. enterica subsp. diarizonae (IIIb), whereas only a few represented S. enterica subsp. enterica houtenae (IV). The most prevalent serovar was IIIb 38:r:z, detected in both N. tessellata (n = 15) and N. natrix (n = 7) and it was the only serovar confirmed in more than one snake species. Another frequently identified serovar was IIIb 57:k:e,n,x,z15, isolated from N. natrix (n = 14). Less common serovars included IIIb 11:l,v:z, IIIb 35:z10:z, IIIb 47:k:1,5,7 and IV 11:z4,z23:−, each detected in 3 individuals; serovars IIIb 18:l,v:z and IIIb 50:r:z35 found in 2 individuals and IIIb (6),14:z10:z, IIIb 17:z10:e,n,x,z15 and IIIb 50:k:z, each found in single snake. Most of the serovars confirmed by both methods were biphasic, except for three monophasic isolates with the antigenic formula IV 11:z4,z23:-, detected exclusively in N. natrix.

Table 1.

Salmonella serovars identified by SeqSero1.2 that matched slide agglutination results.

For 7/62 isolates, differences were observed between the genetic serovar prediction obtained using SeqSero1.2 and the conventional slide agglutination method. All observed differences concerned the H-Ag, while no differences were noted between the genetic prediction and serological reactions specific to O antigens (Table 2). In isolates originating from NN, ZL, and ED, genetically predicted as IV 11:z4,z23:l,z13,z28, IIIb (6),14:z10:z, and IIIb 48:k:z53, respectively, the second flagellar phase was not confirmed. After blocking the motility associated with the first flagellar phase, the isolates completely lost swimming motility, indicating the absence of functional phase 2 flagella. In the isolate genetically predicted as IIIb 18:l,v:z, apart from the lack of phase 2–dependent motility, no agglutination with the H:v antiserum was observed, confirming the antigenic formula of the serovar 18:l:-. Considerable variability and challenges in serovar identification were noted for three isolates obtained from C. austriaca (CA9.6, CA10.5, and CA10.6). All three isolates were classified using SeqSero1.2 as serovar IIIb 38:z10:z50. The H1 antigen z10 was also confirmed by slide agglutination for isolates CA10.5 and CA10.6, whereas CA9.6 showed no flagella expression. Isolates CA10.5 and CA10.6 were capable of motility after blocking the first-phase antigen, indicating biphasic flagellar expression. Based on slide agglutination, the serovar of isolate CA10.5 was confirmed as 38:z10:z6, and that of CA10.6 as 38:z10:z53.

Table 2.

Salmonella serovars identified by SeqSero1.2 that differed from slide agglutination results.

For all three isolates with the predicted antigenic formula 38:z10:z50, sequence similarity analysis of the fliC and fljB genes was performed using nBLAST to identify the most homologous sequences (Table 3). The fliC gene sequences of all isolates showed homology to the flagellin sequence of serovar IIIb 28:z10:z57, with sequence identity ranging from 99.60% to 99.90% and an E-value of 0.0, indicating high-quality alignment. In contrast, the fljB gene sequences exhibited variable degrees of homology to several phase-2 flagellin variants, including H:z53, H:z50, H:z, and H:z6, with sequence identities ranging from 87.99% to 99.60% and an E-value of 0.0, confirming strong alignment for multiple second-phase variants. Interestingly, isolate CA10.5 showed a positive agglutination reaction with the H:z6 antiserum despite having the lowest sequence identity (87.99%) with the corresponding fljB variant.

Table 3.

Comparison of fliC and fljB sequences and slide agglutination results for isolates genetically predicted as serovar IIIb 38:z10:z50.

4. Discussion

Salmonella enterica subsp. diarizonae is characteristic of reptiles and has been frequently isolated from these animals [2,30,31]. Despite its ecological association with ectothermic hosts, reptile-associated strains can cause invasive extraintestinal infections in humans [10,32,33]. Previous reports have documented the occurrence of Salmonella spp. in wild Natrix natrix or Vipera berus populations, whereas other snake species inhabiting Central Europe, such as Coronella austriaca, Natrix tessellata, and Zamenis longissimus, have not been investigated to date with respect to Salmonella serovar composition [7,34]. Our previous work demonstrated the presence of virulence genes in these isolates [17]. According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), as well as national surveillance reports, exotic Salmonella serovars are rarely associated with human zoonotic infections in Poland and Europe [3,4,35,36]. Nevertheless, some of these uncommon variants are capable of causing severe disease in humans, particularly when associated with reptile carriers. In this study, we identified a single isolate belonging to the O48 group, predicted as serovar 48:k:z53. This variant has previously been reported in human salmonellosis cases in Poland [20]. Our findings suggest that these infections may have had a reptile-associated origin. The identification of Salmonella may pose diagnostic challenges due to its atypical biochemical profiles. Lactose fermentation ability and lack of H2S production are unusual for the genus Salmonella [37,38]. Our previous results indicate that many isolates obtained from wild snakes are lactose-positive [17]. In addition, reptile-specific Salmonella subspecies (IIIa, IIIb, IV) often display O-Ag and H-Ag variants rarely described in reference collections [19,20]. Such atypical metabolic profiles may complicate or delay Salmonella identification in routine diagnostics. Advances in molecular typing have introduced in silico tools such as SeqSero1.2 which predict antigenic formulas based on sequence variability in the flagellar genes (fliC and fljB) and in the rfb genes cluster responsible for LPS biosynthesis [27,39,40]. These methods provide valuable insights into the genetic background of serovar diversity. In our study, in silico serovar prediction was first validated using reference Salmonella genomes, showing concordant results between SeqSero1.2 and SeqSero2, and SeqSero1.2 was subsequently applied throughout the research. However, as demonstrated in our study, phenotypic confirmation remains essential to achieve accurate identification. Out of 62 isolates tested, the prediction was fully consistent with slide agglutination for 55 isolates, whereas seven required integration of both methods to resolve discrepancies, including one isolate representing a previously undescribed serovar, IIIb 38:z10:z6. This serovar is indicated in the present study as potentially novel; however, its formal recognition as a new serovar will require further independent verification. In this case, reliance on in silico prediction alone could have resulted in incorrect serovar assignment, and accurate typing required the combined application of genomic prediction and classical slide agglutination. Differences between predicted and phenotypically determined serovars have also been reported by other authors [41,42].

For isolates belonging to the serovars (6),14:-:-; 18:l:-; 38:-:- and 48:k:- determination of the H2 phase by slide agglutination was not possible due to the absence of flagella-dependent swimming motility on Schwörm agar. In these isolates, either a complete lack of motility or motility arrest following suppression of the dominant H1 flagellar phase was observed. Although the direct cause of the lack of flagellar expression was not experimentally confirmed in this study, several molecular and regulatory mechanisms underlying this phenomenon have been described. A key factor involved is the Hin invertase, which directly controls phase variation by regulating the expression of either fliC or fljB [43]. Both phase switching and flagellar structure and activity are complex processes modulated by multiple additional proteins, including LuxS, IacP, STM0347, FlgE, and Fin [43,44,45,46]. Moreover, flagellar biogenesis and activity are strongly influenced by environmental conditions and stress responses, with factors such as temperature and exposure to host immune components, including acid signals and the complement system, affecting flagellar expression [47,48]. These mechanisms have direct implications for bacterial virulence, as although the absence of flagella limits motility, it may promote systemic infection by reducing the immunogenicity of Salmonella cells [49].

A discrepancy was observed for isolate CA10.5, in which the fljB gene showed only 87.99% sequence similarity to the reference H:z6 allele, while slide agglutination yielded a positive reaction with the corresponding antiserum. This finding may indicate the presence of a divergent fljB allele variant that retains key antigenic epitopes recognized by commercial H:z6 antisera despite substantial sequence divergence. To further evaluate the specificity of the H2 phase reaction, slide agglutination was additionally performed using other available H:z factor antisera, including H:z, H:z10, H:z13, H:z15, H:z28, H:z35, H:z4,z23, and H:z53; no cross-reactive agglutination was observed with these antisera, and a positive reaction was detected exclusively with H:z6. Such cases highlight the limitations of relying exclusively on sequence similarity thresholds for H-antigen prediction and underscore the importance of integrating in silico analyses with classical serological methods for accurate serovar determination. The H:z6 flagellar antigen is not a novel antigen and is established within the Kauffmann–White scheme, where it has been reported as a component of several recognized Salmonella serovars and antigenic formulas. Serovars carrying the H:z6 antigen have previously been described, including, for example, S. Bury (4,12,27:c:z6), S. II 6,7:a:z6, S. Sekondi (3,10:e,h:z6), S. Evry (35:i:z6), and several others [19]. These serovars exhibit diverse phase-1 flagellar antigen compositions. However, neither the Kauffmann–White scheme nor available literature reports a serovar combining the H:z10 antigen in the first flagellar phase with H:z6 in the second phase. The specific antigenic configuration observed in this study therefore represents an unreported combination.

Notably, the greatest discrepancies between in silico prediction and phenotypic serotyping were observed among isolates obtained from free-living C. austriaca. All of these isolates originated from a single population inhabiting the same geographic area, suggesting exposure to shared environmental and ecological conditions [25]. Some of the shelters used by this population were also occupied by individuals of the analyzed N. natrix. Under such conditions, horizontal gene transfer, genomic rearrangements, or host-driven selective pressures may contribute to the emergence of atypical antigenic profiles, including altered flagellar phase combinations. Adaptation of Salmonella surface structures to specific hosts or shared ecological niches may therefore play a role in shaping the observed antigenic diversity. Notably, all three isolates CA9.6, CA10.5, and CA10.6 originated from the same snake population. Moreover, isolates CA10.5 and CA10.6 were recovered from the same individual host. Despite this close ecological and host-related association, these isolates differed in their H2 flagellar variants, further supporting the notion that flagellar phase expression and composition represent highly variable structures. Further studies focusing on detailed structural and comparative analyses of flagellar genes and associated regulatory elements are warranted to better understand the genetic basis and ecological drivers of such antigenic variability in reptile-associated Salmonella populations.

Although the occurrence of such rare serovars appears limited, their detection in multiple reptile species underscores the complexity of Salmonella ecology and the role of reptile-associated strains in the epidemiological chain of salmonellosis. The number of studies on the prevalence of Salmonella serovars in reptiles is growing, indicating the need for further research and increased public awareness of RAS, in line with the One Health concept. Italy, Spain, and Poland are the three European countries with the highest number of studies on Salmonella prevalence in reptiles between 1986 and 2023. European studies mainly concern captive reptiles (81%), while studies on other continents focus primarily on free-living reptiles [50]. For this reason, our team conducts research on free-living snakes in Poland [17,25,34].

One of the key aspects associated with RAS and other zoonoses is the potential of bacteria to develop antimicrobial resistance, including multidrug resistance (MDR), as well as resistance to the human immune system. Antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, including Salmonella, have been classified by the WHO as critical priority pathogens [6]. In our previous studies, we assessed the resistance of the analyzed snake-associated Salmonella isolates against a broad panel of antimicrobials. We demonstrated that resistance to tigecycline was prevalent within this population and was observed in 24% (15/62) of the isolates [17,25]. Tigecycline resistance was observed in isolates from both free-living (NN, NT, CA; serovars 38:r:z, 38:z10:z53, 47:k:1,5,7, 57:k:e,n,x,z15) and captive snakes (NF, ED; serovars 11:l,v;z, 18:l,v:z, 18:l:-, 50:r:z35), which may indicate a nonspecific resistance mechanism or potential horizontal gene transfer. Resistance to other antimicrobial classes was detected only in single isolates. However, one Salmonella 38:r:z isolate was classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) and exhibited resistance to penicillin, cephalosporins, tigecycline, and fosfomycin [25]. Although the specific mechanism responsible for tigecycline resistance in this population was not identified, genomic analyses confirmed the presence of the tolC gene [17]. Available literature indicates that efflux pump activity contributes to tetracycline resistance in Enterobacteriaceae [51,52].

Overall, the analyzed isolates were largely susceptible to the tested antimicrobials, and multidrug resistance was not widespread within the studied population. In contrast, a high level of resistance to the bactericidal activity of human serum was observed. We demonstrated that 89% of isolates were resistant and capable of active proliferation in 50% human serum [25]. The remaining isolates were classified as serum-sensitive (n = 5; serovars 35:z10:z, 38:r:z, 50:k:z and 50:r:z35) or intermediate (n = 1; serovar 38:r:z). The phenomenon of serum resistance is likely associated with alterations in outer membrane proteins (OMPs) and structural features of LPS, which are known to modulate susceptibility to complement-mediated killing [53,54,55]. The three serovars sharing the same genetic antigen prediction (isolates CA9.6, CA10.5, CA10.6), which constitute the primary focus of this study, exhibited comparable phenotypic profiles with respect to both antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance to the bactericidal activity of human serum.

Further analyses of virulence determinants and genomic features of these isolates are required to better understand their pathogenic potential. Our ongoing research focuses on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying virulence and serum resistance in reptile-associated Salmonella, which may contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of their zoonotic and ecological significance.

5. Conclusions

Literature reports have increasingly highlighted the presence of Salmonella in diverse reptile hosts worldwide, emphasizing the need for detailed characterization of this reservoir as a potential link between the natural environment and human infections. At the same time, the environmental origin of these isolates may contribute to distinct phenotypic and genotypic traits resulting from adaptation to external conditions.

In this context, the identification of rare Salmonella serovars may pose diagnostic challenges. Our study demonstrated the effectiveness of combining genetic prediction with slide agglutination for the identification of reptile-associated Salmonella serovars. The prediction was accurate for 55 out of 62 isolates, whereas for the remaining 11.3%, both approaches had to be integrated to obtain reliable results. We emphasize the continued importance of phenotypic confirmation and believe that, despite the progress in genomic prediction tools, slide agglutination will remain the gold standard for Salmonella identification for years to come. The use of both methods enabled us to identify a serovar IIIb 38:z10:z6, which has not been previously described in the literature and has not been reported among isolated serovars to date. However, these findings require further independent verification, and additional analyses of the investigated strains are currently ongoing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010437/s1, File S1: FASTA sequences of fliC and fljB genes from CA9.6, CA10.5 and CA10.6 isolates; Figure S1.1: Sequencing quality metrics overview; Figure S1.2: Distribution of read quality across samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., A.P. and G.B.-P.; methodology, M.M. and M.W.; investigation: DNA sequencing, M.M. and M.W.; raw data assembling, M.W.; in silico analyses, M.M.; serotyping, M.M.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., A.P., M.W., G.B.-P.; visualization, M.M., M.W.; supervision, A.P., G.B.-P.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in whole by National Science Center, Poland Grant number 2023/49/N/NZ6/03411. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study used only previously collected Salmonella isolates; therefore, no new permits were required. Earlier sampling of snakes was performed under permits issued by the Directorates for Environmental Protection (decisions WPN.6401.61.2021.AP, dated 18 May 2021; WPN.6401.140.2021.AR, 25 May 2021; WPN.6401.270.2019.ZB, 10 April 2019; no. OP.6401.77.2021.KW, 16 April 2021; DZP-WG.6401.91.2020.TŁ, 10 April 2020; no. DZP-WG.6401.80.2023.TŁ.2, 22 May 2023). Sampling procedures complied with the Polish Act of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes, and approval from a local ethics committee was not required for environmental swab collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The nucleotide sequences generated and analyzed in this study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the following accession numbers: PX520105, PX520106, PX520107, PX520108, PX520109, and PX520110. Additional data supporting the findings of this study, including FASTA-format sequences of the fliC and fljB genes used for comparative analysis are provided in Supplementary File S1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Aleksandra Kolanek, Stanisław Bury, Bartłomiej Zając for their assistance in collecting the swab samples that constituted the source material for the isolation of Salmonella analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NN | Natrix natrix |

| NT | Natrix tessellata |

| CA | Coronella austriaca |

| ZL | Zamenis longissimus |

| ED | Elaphe dione |

| NF | Nerodia fasciata |

| RAS | Reptile associated salmonellosis |

| O-Ag | O–antigen |

| H-Ag | H–antigen |

| PCM | Polish Collection of Microorganisms |

References

- Lamichhane, B.; Mawad, A.M.M.; Saleh, M.; Kelley, W.G.; Harrington, P.J., II; Lovestad, C.W.; Amezcua, J.; Sarhan, M.M.; El Zowalaty, M.E.; Ramadan, H.; et al. Salmonellosis: An Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Innovative Approaches to Mitigate the Antimicrobial Resistant Infections. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dróżdż, M.; Małaszczuk, M.; Paluch, E.; Pawlak, A. Zoonotic Potential and Prevalence of Salmonella Serovars Isolated from Pets. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2021, 11, 1975530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2020 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2021, 19, 6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Kumar, S.; Jangid, H.; Dutta, J.; Shidiki, A. The Rise of Non-Typhoidal Salmonella: An Emerging Global Public Health Concern. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1524287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V.; Mock, R.; Burgkhardt, E.; Junghanns, A.; Ortlieb, F.; Szabo, I.; Marschang, R.; Blindow, I.; Krautwald-Junghanns, M.E. Cloacal Aerobic Bacterial Flora and Absence of Viruses in Free-Living Slow Worms (Anguis fragilis), Grass Snakes (Natrix natrix) and European Adders (Vipera berus) from Germany. EcoHealth 2014, 11, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, K.; Koczura, R.; Dudek, M.; Sajkowska, Z.A.; Ekner-Grzyb, A.E. Detection of Salmonella enterica in a Sand Lizard (Lacerta agilis, Linnaeus, 1758) City Population. Herpetol. J. 2016, 26, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zając, M.; Wasyl, D.; Różycki, M.; Bilska-Zając, E.; Fafiński, Z.; Iwaniak, W.; Krajewska-Wędzina, M.; Hoszowski, A.; Goławska, O.; Fafińska, P.; et al. Free-Living Snakes as a Source and Possible Vector of Salmonella spp. and Parasites. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2016, 62, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Forsberg, J.; Gilcher, R.O.; Smith, J.W.; Crutcher, J.M.; McDermott, M.; Brown, B.R.; George, J.N. Salmonella Sepsis Caused by a Platelet Transfusion from a Donor with a Pet Snake. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyriac, J.; Wozniak, E.R. Infantile Salmonella Meningitis Associated with Gecko-Keeping. Commun. Dis. Public Health 2000, 3, 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Paphitis, K.; Habrun, C.A.; Stapleton, G.S.; Reid, A.; Lee, C.; Majury, A.; Murphy, A.; McClinchey, H.; Corbeil, A.; Kearney, A.; et al. Salmonella Vitkin Outbreak Associated with Bearded Dragons, Canada and United States, 2020–2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitten, T.; Bender, J.B.; Smith, K.; Leano, F.; Scheftel, J. Reptile-Associated Salmonellosis in Minnesota, 1996–2011. Zoonoses Public Health 2015, 62, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Książczyk, M.; Kuczkowski, M.; Dudek, B.; Korzekwa, K.; Tobiasz, A.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Paluch, E.; Wieliczko, A.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. Application of Routine Diagnostic Procedure, VITEK 2 Compact, MALDI-TOF MS, and PCR Assays in Identification Procedure of a Bacterial Strain with Ambiguous Phenotype. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 72, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Gao, W.; Tan, X.; Han, Y.; Jiao, F.; Feng, B.; Xie, J.; Li, B.; Zhao, H.; Tu, H.; et al. MALDI-TOF MS Is an Effective Technique to Classify Specific Microbiota. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0030723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.R.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, E.-Y.; Park, E.H.; Hwang, I.Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.A.; Uh, Y.; Shin, K.S.; et al. Performance of MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry (VITEK MS) in the Identification of Salmonella Species. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Małaszczuk, M.; Dróżdż, M.; Bury, S.; Kuczkowski, M.; Morka, K.; Cieniuch, G.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Wzorek, A.; Korzekwa, K.; et al. Virulence Factors of Salmonella spp. Isolated from Free-Living Grass Snakes Natrix natrix. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-H.; Parker, C.H.; Croley, T.R.; McFarland, M.A. Genus, Species, and Subspecies Classification of Salmonella Isolates by Proteomics. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimont, P.; Weill, F.X. Antigenic Formulae of the Salmonella Serovars; WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella: Paris, France, 2007; 166p. [Google Scholar]

- Issenhuth-Jeanjean, S.; Roggentin, P.; Mikoleit, M.; Guibourdenche, M.; de Pinna, E.; Nair, S.; Fields, P.I.; Weill, F.X. Supplement 2008–2010 (No. 48) to the White–Kauffmann–Le Minor Scheme. Res. Microbiol. 2014, 165, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO/TR 6579-3; Microbiology of Food and Animal Feed—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 3: Guidelines for Serotyping of Salmonella spp. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- McQuiston, J.R.; Parrenas, R.; Ortiz-Rivera, M.; Gheesling, L.; Brenner, F.; Fields, P.I. Sequencing and Comparative Analysis of Flagellin Genes fliC, fljB, and flpA from Salmonella. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 1923–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, C.; Sherwood, R.; Gheesling, L.L.; Brenner, F.W.; Fields, P.I. Molecular Analysis of the rfb O Antigen Gene Cluster of Salmonella enterica Serogroup O:6,14 and Development of a Serogroup-Specific PCR Assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6099–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uelze, L.; Grützke, J.; Borowiak, M.; Hammerl, J.A.; Juraschek, K.; Deneke, C.; Tausch, S.H.; Malorny, B. Typing methods based on whole genome sequencing data. One Health Outlook 2020, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małaszczuk, M.; Pawlak, A.; Bury, S.; Kolanek, A.; Błach, K.; Zając, B.; Wzorek, A.; Cieniuch-Speruda, G.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Gamian, A.; et al. From Bacterial Diversity to Zoonotic Risk: Characterization of Snake-Associated Salmonella Isolated in Poland with a Focus on Rare O-Ag of LPS, Antimicrobial Resistance and Survival in Human Serum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chklovski, A.; Parks, D.H.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM2: A Rapid, Scalable and Accurate Tool for Assessing Microbial Genome Quality Using Machine Learning. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yin, Y.; Jones, M.B.; Zhang, Z.; Deatherage Kaiser, B.L.; Dinsmore, B.A.; Fitzgerald, C.; Fields, P.I.; Deng, X. Salmonella Serotype Determination Utilizing High-Throughput Genome Sequencing Data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afgan, E.; Baker, D.; Batut, B.; van den Beek, M.; Bouvier, D.; Čech, M.; Chilton, J.; Clements, D.; Coraor, N.; Grüning, B.A.; et al. The Galaxy Platform for Accessible, Reproducible and Collaborative Biomedical Analyses: 2018 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W537–W544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, L.; Vercammen, F.; Bertrand, S.; Collard, J.M.; De Ceuster, S. Isolation of Salmonella from Environmental Samples Collected in the Reptile Department of Antwerp Zoo Using Different Selective Methods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 101, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, V.O.; Fernström, L.L.; Melin, L.; Boqvist, S. Salmonella Isolated from Individual Reptiles and Environmental Samples from Terraria in Private Households in Sweden. Acta Vet. Scand. 2014, 56, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernar, B.; Gande, N.; Bernar, A.; Müller, T.; Schönlaub, J. Case Report: Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Infections Transmitted by Reptiles and Amphibians. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1278910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otake, S.; Ajiki, J.; Yoshida, M.; Koriyama, T.; Kasai, M. Contact with a Snake Leading to Testicular Necrosis Due to Salmonella Saintpaul Infection. Pediatr. Int. 2021, 63, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Morka, K.; Bury, S.; Antoniewicz, Z.; Wzorek, A.; Cieniuch, G.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Cichoń, M.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. Cloacal Gram-Negative Microbiota in Free-Living Grass Snake Natrix natrix from Poland. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2166–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Public Health—National Research Institute. Chief Sanitary Inspectorate. Infectious Diseases and Poisonings in Poland in 2023; National Institute of Public Health—National Research Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. Available online: https://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/2023/Ch_2023.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- National Institute of Public Health—National Research Institute. Chief Sanitary Inspectorate. Infectious Diseases and Poisonings in Poland in 2024; National Institute of Public Health—National Research Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2025. Available online: https://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/2024/Ch_2024.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Hess, C.; Drauch, V.; Spergser, J.; Kornschober, C.; Hess, M. Detection of Atypical Salmonella Infantis Phenotypes in Broiler Environmental Samples. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00106-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, J.; Rebelo, A.; Ribeiro, S.; Peixe, L.; Novais, C.; Antunes, P. Atypical Non-H2S-Producing Monophasic Salmonella Typhimurium ST3478 Strains from Chicken Meat at Processing Stage Are Adapted to Diverse Stresses. Pathogens 2020, 9, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diep, B.; Barretto, C.; Portmann, A.C.; Fournier, C.; Karczmarek, A.; Voets, G.; Li, S.; Deng, X.; Klijn, A. Salmonella Serotyping: Comparison of the Traditional Method to a Microarray-Based Method and an In Silico Platform Using Whole Genome Sequencing Data. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, S.; Simon, S.; Tille, A.; Fruth, A.; Flieger, A. Genome-Based Salmonella Serotyping as the New Gold Standard. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.L.; Low, A.J.; Koziol, A.G.; Thomas, M.C.; Leclair, D.; Tamber, S.; Wong, A.; Blais, B.W.; Carrillo, C.D. Systematic Evaluation of Whole Genome Sequence-Based Predictions of Salmonella Serotype and Antimicrobial Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, G.M.; Morin, P.M. Salmonella Serotyping Using Whole Genome Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, Z.; Xue, B.; Lu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zou, Q. Salmonella Regulator STM0347 Mediates Flagellar Phase Variation via Hin Invertase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K.; Dono, K.; Aizawa, S. Length Control of the Flagellar Hook in a Temperature-Sensitive flgE Mutant of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 3590–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, J.S.; Kim, J.S.; Jang, J.I.; Kim, H.G.; Bang, I.S.; Park, Y.K. Effect of iacP Mutation on Flagellar Phase Variation in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Strain UK-1. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4332–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsukake, K.; Nakashima, H.; Tominaga, A.; Abo, T. Two DNA Invertases Contribute to Flagellar Phase Variation in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Strain LT2. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futoma-Kołoch, B.; Małaszczuk, M.; Korzekwa, K.; Steczkiewicz, M.; Gamian, A.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. The Prolonged Treatment of Salmonella enterica Strains with Human Serum Effects in Phenotype Related to Virulence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, M.; Song, N.; Jia, H.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, C.; Li, B. Host Acid Signal Controls Salmonella Flagella Biogenesis through the CadC–YdiV Axis. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2146979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, L.; Sasías, S.; Martínez, A.; Betancor, L.; Estevez, V.; Scavone, P.; Bielli, A.; Sirok, A.; Chabalgoity, J.A. Repression of Flagella Is a Common Trait in Field Isolates of Salmonella enterica Serovar Dublin and Is Associated with Invasive Human Infections. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslin, C.; Salas-Brito, P.; Coello, D.; Morales-Jadán, D.; Viteri-Dávila, C.; Coral-Almeida, M. Salmonella Prevalence and Serovar Distribution in Reptiles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gut Pathog. 2025, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetri, S.; Bhowmik, D.; Paul, D.; Pandey, P.; Chanda, D.D.; Chakravarty, A.; Bora, D.; Bhattacharjee, A. AcrAB-TolC efflux pump system plays a role in carbapenem non-susceptibility in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, N.K.; Tartor, Y.H.; Gharieb, R.M.A.; Erfan, A.M.; Khalifa, E.; Said, M.A.; Ammar, A.M.; Samir, M. Extensive Drug-Resistant Salmonella enterica Isolated from Poultry and Humans: Prevalence and Molecular Determinants Behind the Co-resistance to Ciprofloxacin and Tigecycline. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 738784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Rybka, J.; Dudek, B.; Krzyżewska, E.; Rybka, W.; Kędziora, A.; Klausa, E.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. Salmonella O48 Serum Resistance is Connected with the Elongation of the Lipopolysaccharide O-Antigen Containing Sialic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, B.; Krzyżewska, E.; Kapczyńska, K.; Rybka, J.; Pawlak, A.; Korzekwa, K.; Klausa, E.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. Proteomic Analysis of Outer Membrane Proteins from Salmonella Enteritidis Strains with Different Sensitivity to Human Serum. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishio, M.; Okada, N.; Miki, T.; Haneda, T.; Danbara, H. Identification of the outer-membrane protein PagC required for the serum resistance phenotype in Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis. Microbiology 2005, 151, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.