Abstract

Due to the influence of various dynamic meteorological factors, accurate Tropical Cyclone (TC) track prediction is a significant challenge. However, current deep learning based time series prediction models fail to simultaneously capture both short-term and long-term dependencies, while also neglecting the change in meteorological environment pattern associated with TC motion. This limitation becomes particularly pronounced during sudden turning in the TC track, resulting in significant deterioration of prediction accuracy. To overcome these limitations, we propose LFInformer, a hybrid deep learning framework that integrates an Informer backbone, a Frequency-Enhanced Channel Attention Mechanism (FECAM), and a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network for TC track prediction. The Informer backbone is underpinned by ProbSparse Self-Attention in both the encoder and the causally masked decoder, prioritizing the most informative query–key interactions to deliver robust long-range modeling and sharper detection of turning signals. FECAM enhances meteorological inputs via discrete cosine transforms, band-wise weighting, and channel-wise reweighting, then projects the enhanced signals back into the time domain to produce frequency-aware representations. The LSTM branch captures short-term variations and localized temporal dynamics through its recurrent structure. Together, these components sustain high accuracy during both steady evolution and sudden turnin. Experiments based on the JMA and IBTrACS 1951–2022 Northwest Pacific TC data show that the proposed model achieves an average absolute position error (APE) of 72.39 km, 117.72 km, 145.31 km and 168.64 km for the 6-h, 12-h, 24-h and 48-h forecasting tasks, respectively. The proposed model enhances the accuracy of TC track predictions, offering an innovative approach that optimally balances precision and efficiency in forecasting sudden turning points.

1. Introduction

TC are among the most destructive natural disasters globally [1], particularly in the Northwest Pacific region, where TC frequently occur and cause severe impacts on the economy, society, and ecosystems of coastal areas. The intense storm surges, heavy rainfall, and strong winds associated with TC often result in significant loss of life and property damage. For example, in 2017, China experienced eight TC landfalls, affecting 5.879 million people and causing approximately 5 billion USD in economic losses [2]. Therefore, accurate TC track prediction is crucial not only for minimizing losses, but also for providing timely warnings to the government and the public, and offering a scientific foundation for post-disaster response and mitigation [3].

The evolution of TC track is influenced by a variety of factors, including ocean temperature, air pressure, topography, wind speed, and other complex meteorological environmental factors [4]. The interactions among these factors result in highly nonlinear and complex TC track. However, traditional TC track prediction methods rely on statistical models (CLIPER) [5] and numerical weather prediction (NWP) [6] models. Statistical models typically base their predictions on the relationship between historical data and meteorological factors, using regression analysis and pattern recognition techniques. While they provide quick results, their accuracy is significantly limited when handling complex nonlinear relationships and long-term predictions [7]. However, NWP models can more accurately simulate meteorological conditions, but they come with higher computational complexity and often exhibit large errors in medium- to long-term track predictions [8].

With the rapid increase in meteorological observation data, traditional prediction methods may face challenges in efficiently handling such large-scale spatiotemporal data, which has led deep learning methods to gradually emerge as a promising research direction in the field of TC track prediction. In particular, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [9] and their variants, such as long short-term memory networks (LSTM) [9] and gated recurrent units (GRU) [10], excel at handling long-term dependencies in sequential data, leading to significant advancements in TC track prediction [11]. For example, Lian, J et al. [12] proposed a TC track prediction model that combines RNN and attention mechanisms, demonstrating the effectiveness of deep learning in handling complex meteorological data. However, traditional RNNs still face challenges such as long-term dependencies and gradient vanishing [13], which limit their performance in practical applications. To address these issues, LSTM networks have been widely applied to TC track prediction [14]. By introducing gating units, LSTM effectively overcomes the gradient explosion and vanishing problems in RNNs, and performs more stably in learning from long time-series data [15]. For example, Gao, S et al. [16] trained an LSTM network on TC data from mainland China and proposed a new TC track prediction method, significantly improving prediction accuracy. Tong, B et al. [17] proposed a spatiotemporal model based on ConvLSTM, which combines the advantages of convolutional neural networks and LSTM to better handle large-scale meteorological data. However, LSTM models still face issues such as high computational resource requirements and slow training speeds, especially when handling long time-series data, which limits their effectiveness [18]. With the development of deep learning technologies, the Informer model [19], as a new framework for processing sequential data, has begun to demonstrate its potential in the field of meteorological forecasting. The Informer model, by introducing Self-Attention Mechanisms and Sparse Attention computation, is capable of efficiently processing long time-series data, particularly suited for large-scale meteorological datasets. Compared to traditional LSTM and GRU models, which struggle with capturing long-term dependencies due to their limited memory and vanishing gradient issues, Informer excels at modeling long-term sequential dependencies, significantly improving both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency.

Recent TC forecasting studies have also explored more domain-tailored deep learning architectures. For example, Transformer-based models have been developed for joint TC track–intensity prediction [20]. Beyond TC-specific models, GNN-based global weather forecasting systems have demonstrated strong medium-range skill and can support tropical cyclone tracking [21]. In addition, climate-oriented Transformer foundation models provide a unified pretrained backbone that can be fine-tuned for diverse weather and climate prediction tasks [22].

In summary, many current deep learning approaches for TC track prediction face challenges in jointly learning multiple temporal features, hindering their ability to simultaneously capture both short-term dynamic changes and long-term development trends of TC track progression. thereby affecting their ability to accurately predict the overall trend of the TC. Furthermore, several traditional approaches to TC track prediction often overlook the periodic change characteristics of meteorological environment factors such as wind speed and air pressure that are related to TC track development, which affects their ability to accurately predict sudden turning points in the TC’s track. We use the term “periodic change” to denote recurring meteorological environment change patterns rather than strict cycles; a precise definition and modeling rationale are provided in Section 2.3. Additionally, LSTM has advantages in handling short-term temporal dependencies, and the Informer model can effectively address the computational complexity issues in long-sequence predictions. However, there is scant research on combining the two to enhance the ability to capture the complex dynamic change in TC characteristics. To address this, this paper proposes a novel TC track prediction model, LFInformer, with the following main contributions:

- A novel neural network LFInformer: Integrating Informer, FECAM and LSTM. The model can simultaneously focus on overall development trends of TC track turning and the local dynamic features.

- TC track turning critical time point attention block: Introducing ProbSparse Self-Attention mechanism into Informer encoder, this mechanism has the ability to filter out critical time points and focus precise attention on points carrying turning point information, effectively improving the ability to predict TC track critical turning points.

- Meteorological environment change pattern perception block: This block is mainly composed of Frequency-Enhanced Channel Attention mechanis, enabling our model to find physical processes at different time scales in the raw data based on DCT, and focus on rapidly changing meteorological factors during TC trajectories. This provides crucial pattern features for predicting sudden turnings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. LFInformer Architecture

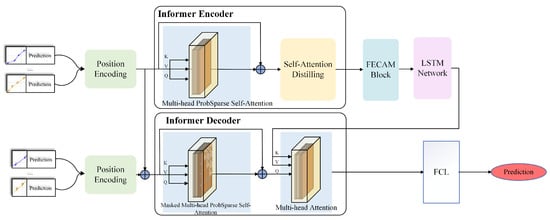

To improve the accuracy and stability of TC track prediction, this paper proposes a new Informer architecture—LFInformer, an efficient Transformer-style architecture [23]. Its core objective is to combine short-term and long-term temporal capturing abilities and enhance the capture of the influence of periodic change in meteorological factors change patterns on track development. The structure of LFInformer is shown in Figure 1, which mainly consists of the Informer encoder, Informer decoder, LSTM network, FECAM block and fully connected layer (FCL). The block order is designed to first obtain a compact long-range temporal representation via the Informer (with distilling/downsampling), and then refine it using FECAM and LSTM for periodic-pattern enhancement and short-term dynamics modeling before the final regression layer.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the proposed method.

The proposed model input is divided into two parts: the Informer encoder input and the Informer decoder input.In the encoder section, the input consists of the predefined step-length data of the TC’s track, with each time step processed through position encoding to ensure the model can comprehend the order and dependencies of the time series. The decoder operates under a causal constraint. It only consumes the historical prefix of the target sequence together with the encoder context; no future observations are used In this way, the model can simultaneously utilize both preceding and subsequent data to predict the turning in the TC’s track, thereby improving the accuracy and stability of the TC track forecast. Furthermore, the core components of the model include two main parts: the Informer encoder and the Informer decoder. The Informer encoder employs a Probabilistic Sparse Self-Attention Mechanism to capture the global dependency characteristics of the input sequence through efficient sparse computation, while also using Self-Attention distilling to extract key information and compress data redundancy. The Informer decoder section utilizes a Masked ProbSparse Self-Attention Mechanism to generate high-quality decoding outputs, ensuring no information leakage during the prediction process. Additionally, the decoder uses a multi-head attention mechanism to combine the encoder’s output features with the decoder’s contextual information, thereby enhancing its ability to predict future turning in the TC’s track.

Furthermore, to enhance the model’s ability to capture the complex periodic dynamic features of meteorological factors patterns during the TC’s development and turning, the FECAM block is introduced. This module combines frequency domain enhancement techniques and channel attention mechanisms to extract the periodic change in meteorological environment change patterns in the TC’s track, such as the impact of the periodic change in environmental factors like wind speed and air pressure on the track trend, thereby enhancing the model’s sensitivity to periodic change and nonlinear relationships in time series data. The FECAM block receives the output from the Informer encoder, and the output features of the FECAM block are fed into the LSTM network to further capture and process short-term dependencies and local dynamic change, ensuring that the model can effectively handle the short-term fluctuations and trend turning in the TC’s track. Finally, the output of the Informer decoder is mapped to the target space through a fully connected layer, generating the predicted results for the TC’s track. The LFInformer model fully combines the Informer framework’s global modeling capability for long sequences, LSTM’s short-term dependency modeling ability, and FECAM’s periodic dynamic feature enhancement mechanism, providing an efficient and reliable solution for accurate TC track forecasting.

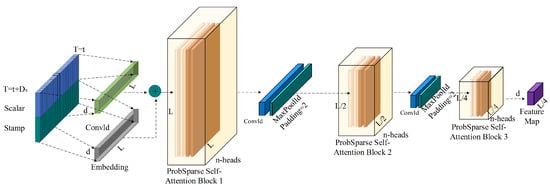

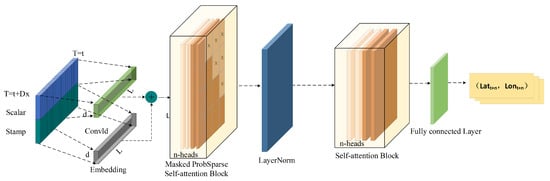

2.2. Informer Encoder

The Informer encoder is designed to improve computational efficiency in long-term time series forecasting, while enhancing the model’s ability to capture both global dependencies and local features.Compared to Transformer architectures proposed prior to Informer, the Informer encoder incorporates a Probabilistic Sparse Self-Attention Mechanism, integrates Conv1d to enhance feature extraction, and employs a progressive downsampling strategy to reduce sequence length, thereby preserving critical information while lowering computational cost. Figure 2 illustrates the complete architecture of the Informer encoder, which consists of several key components: input embedding, ProbSparse Self-Attention Blocks, Conv1d, Maxpooling for downsampling, and feature map generation.

Figure 2.

The structure of Informer encoder.

The input sequence is first processed by the input embedding layer, which maps the raw time series data into a high-dimensional feature space and incorporates temporal information to enhance the model’s ability to capture temporal dependencies. Subsequently, the data passes through multiple ProbSparse Self-Attention Blocks, where Sparse Attention matrices are computed to capture global dependencies. In addition, the one-dimensional convolution layer is employed to further enhance the representation of local information, providing more stable temporal features. To reduce computational complexity, the encoder applies Maxpooling layers to downsample the sequence, gradually compressing the data stream while reducing redundant information, and ultimately generating feature maps for use by the decoder.

2.2.1. Input Embedding

The input embedding method of Informer enables the time series data to incorporate not only basic feature information, but also fully leverage time stamp and time difference information. Let the input time series be:

where T denotes the number of time steps, and d represents the dimensionality of the input features. To enhance the model’s understanding of temporal information, each time step is augmented with a corresponding time scalar and timestamp , resulting in the final input representation as:

The Conv1d is used to map temporal information into the same dimensional space, ensuring that the model can capture time-dependent features. In this way, the Informer encoder leverages not only the numerical features of the data but also incorporates temporal information, thereby enhancing its ability to handle irregular time intervals.

2.2.2. ProbSparse Self-Attention Blocks

The Self-Attention Mechanism in Transformers, while powerful for feature extraction, suffers from quadratic computational complexity in processing long sequences. Recent studies reveal that self-attention weights demonstrate inherent sparsity patterns [24], suggesting opportunities for efficiency optimization. The Sparse Transformer leverages spatial correlations to reduce computation, while the LogSparse Transformer employs exponential step sizes to capture temporal patterns [25]. More recently, the Longformer extends these approaches with configurable sparsity patterns [26]. However, current methods face two critical limitations: their heuristic designs lack theoretical grounding, and their uniform treatment of attention heads overlooks the multi-head mechanism’s diverse representational capacities. These shortcomings result in both computational redundancy and suboptimal performance, particularly in long-sequence temporal forecasting tasks.

To address this issue, the model in this paper employs a ProbSparse Self-Attention Mechanism that focuses on the most informative query positions, significantly reducing computational complexity while maintaining the model’s predictive capability.

The core idea of the ProbSparse Self-Attention Mechanism is to quantify the dependence distribution discrepancy between query vectors and key vectors using a sparsity scoring function, and select the attention terms that contribute the most to the prediction. Given the input sequence , its Q (Query), K (Key), and V (Value) [27] matrices are generated through linear transformations:

where , , and are learnable parameters. For each query vector , the sparsity scoring function is defined as:

This function measures the concentration of the dependence distribution of over the key set K. A higher score indicates that has significant dependence on a few . Let L be the sequence length. Based on the sparsity scoring , the Self-Attention Mechanism employs a Top-U selection strategy, retaining only the top highest-scoring terms in each row to construct the Sparse Attention matrix . The calculation is accelerated through random projection approximation. The process involves randomly sampling candidate key vectors from K, then calculating the similarity between and the candidate keys to approximate , and finally selecting the top U keys with the highest scores to generate Sparse Attention weights.

Only the top U important terms are retained in the attention matrix, and the scores of the remaining positions are set to zero. Subsequently, the Sparse Attention matrix performs a weighted sum on the value matrix V, generating the global representation for the time step:

This ProbSparse Self-Attention Mechanism effectively captures the dependencies between important time steps in TC track prediction, such as moments when significant changes occur in wind speed or pressure, or critical time points when the TC track undergoes major shifts.

2.2.3. MaxPooling

Although the ProbSparse Self-Attention Mechanism effectively reduces redundant attention computations, the generated feature representations may still contain some redundant information. To address this, the Informer encoder incorporates a Self-Attention distillation operation, which refines the feature representations by pruning the temporal dimension, significantly improving computational efficiency. The Self-Attention distillation extracts local features through Conv1d and handles nonlinear relationships with an ELU activation function [28]. As shown in Figure 2 Then, MaxPooling with a stride of 2 is applied to downsample the input temporal dimension [29,30], halving the input length. The computation process can be expressed as:

where represents the output of Multi-Head ProbSparse Self-Attention. The kernel size of the 1D convolution is 3, and the stride of the max pooling is 2, reducing the temporal dimension length from to optimize memory. In the distillation operation, the encoder adopts a pyramid structure to gradually reduce the input temporal dimension while ensuring that the output hidden representations retain global contextual information. The time step length of each layer’s output is progressively reduced, and the final hidden representation of the is generated by stacking the outputs of each layer:

2.3. FECAM Block

In this paper, we do not use “periodic” to mean a strict, perfectly repeating cycle. Rather, we refer to recurring short-term temporal patterns in environmental fields (e.g., wind and pressure) over time scales of hours to days. Concretely, the track tendency often responds in a similar way when a sequence of changes reappears—for example, a gradual strengthening of easterly steering flow followed by a brief relaxation can repeatedly nudge the track poleward–eastward. To this end, we endow the model with climate–environmental pattern perception: FECAM operates in the frequency domain to highlight the time scales where such repeatable patterns live and uses channel attention to emphasize those bands that are most predictive of track deflection. In short, the model learns mappings from Δwind/Δpressure patterns over a recent window to the subsequent track tendency, and can reuse this knowledge when similar patterns recur later in the sequence.

FECAM is a novel attention mechanism block introduced in this paper, aimed at significantly enhancing the ability to capture frequency-domain features in time series prediction tasks. Traditional attention mechanisms primarily focus on capturing temporal dependencies in sequential data. However, in many practical applications, especially in tasks like TC track prediction, which depend on the periodic change of meteorological factors environment change patterns, the frequency-domain information of environmental factors plays a crucial role. Traditional methods often overlook the periodic change of these meteorological environmental factors in the frequency domain, making it difficult for the model to accurately capture the long-term trends and dynamic turning of the TC track.

The innovation of FECAM lies in the introduction of DCT [31] to replace the traditional Fourier Transform (FT), effectively overcoming the Gibbs phenomenon [32,33] that may occur in Fourier Transform. This approach avoids the interference of high-frequency noise with the model by eliminating the associated artifacts. FECAM can more accurately capture the periodic change of meteorological factors patterns in the TC track, such as the temporal variations in wind speed, pressure, and other factors. By extracting these frequency-domain features, FECAM not only enhances the model’s sensitivity to frequency-domain information but also strengthens its ability to understand complex dynamic turning, thereby optimizing the TC track prediction performance.

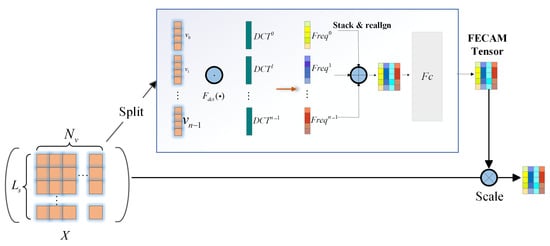

In the TC track prediction task, the input multivariate time series includes longitude, latitude, time, wind speed, and pressure. As shown in Figure 3, the FECAM aims to explicitly extract and utilize periodic patterns hidden in these time series features.

Figure 3.

The structure of frequency enhanced channel attention mechanism.In this diagram, the color coding represents different data states and operations: the orange squares denote the input feature segments after splitting; the teal vertical blocks indicate the DCT operations; the distinct colors (yellow, purple, reddish-brown) represent different frequency components extracted from the input; the light grey block corresponds to the Fully Connected (Fc) layer; and the multi-colored grids illustrate the stacked and realigned frequency-enhanced features.

The input to FECAM is the feature tensor , where denotes the number of variables and denotes the sequence length. First, the module splits the feature tensor along the variable channel dimension, treating each variable’s sequence independently. Each of these sequences is then transformed into the frequency domain using the DCT, which has stronger energy compaction properties than the traditional Fourier Transform and avoids boundary effects such as the Gibbs phenomenon.

The frequency representation of each input is computed as follows:

where represents the j-th basis function of the DCT for variable i, and is the length of the frequency vector. The DCT operation extracts both the low-frequency components and high-frequency components from the input sequences.

Once the DCT is applied to all n variables, the resulting frequency vectors are stacked together to form a comprehensive frequency-domain representation:

This stacked frequency tensor is then fed into a fully connected layer to generate attention weights for each variable channel, allowing the model to emphasize features with strong periodic signals. The output attention weights are used to scale the original feature tensor X, enhancing the model’s capacity to capture periodic and trend-related dependencies in TC dynamics.

Based on the frequency domain tensor, FECAM further optimizes feature representation through a channel attention mechanism. Specifically, FECAM first calculates the global feature vector for each channel via Global Average Pooling ():

where represents the global feature description for each channel. Then, the channel attention mechanism generates channel weights through a two-layer fully connected network:

where and are learnable weight parameters, is the ReLU activation function, and is the Sigmoid activation function. The channel weights represent the relative importance of different variables and dynamically adjust the contribution of variables such as wind speed and pressure to the TC track prediction. FECAM optimizes the frequency domain features by adjusting the channel weights, generating enhanced feature representations:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. In this way, FECAM captures both the periodic patterns and the dynamic interactions between channels, providing more accurate input for the subsequent LSTM module.

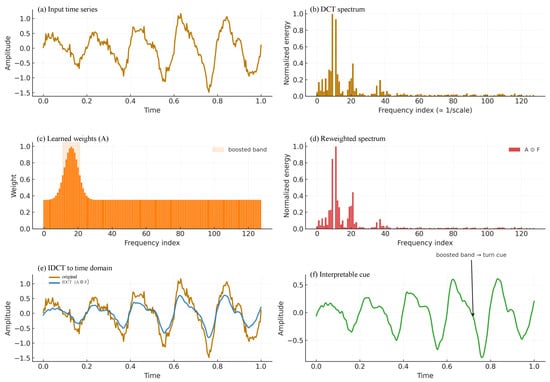

Figure 4 illustrates how FECAM leverages frequency-domain information to complement time-domain attention. Starting from the environmental time series (Figure 4a), each channel is transformed from the time domain to the frequency domain so that energy is separated by time scale; the DCT spectrum (Figure 4b) makes slow trends (low frequencies) and recurring short-term motifs (higher frequencies) explicit, with the frequency index inversely related to period. On this spectrum, FECAM learns data-driven channel–frequency weights A (Figure 4c) that emphasize scales which historically precede track deflection while de-emphasizing irrelevant bands. Applying these weights yields the reweighted spectrum (Figure 4d), suppressing noise and amplifying informative scales. The enhanced signal is then projected back to the time domain via IDCT (Figure 4e, blue), which can be interpreted as a scale-aware version of the original input (gold). Finally, the emphasized band produces a stable time-domain signature that cues a turn tendency (Figure 4f) and is less sensitive to phase shifts than position-based, time-domain attention. In short, FECAM attends to scales×channels rather than positions, providing a denoised, scale-selective representation that is fused with the main branch for track prediction.

Figure 4.

FECAM frequency-domain processing with panels (a–f). In panel (a), the orange line represents the input time series. In panel (b), the yellow bars indicate the magnitude of the DCT spectrum frequencies. In panel (f), the green line illustrates the extracted interpretable cue highlighting the periodic patterns.

FECAM combines the dual advantages of frequency domain enhancement and channel attention mechanisms. In the TC track prediction task, this module is capable of capturing the periodic in meteorological factors environment change patterns during the development of the TC track. At the same time, FECAM dynamically adjusts the relative weights between variables, enabling the model to efficiently extract key information even in the presence of complex multivariable interactions. Through this feature optimization, FECAM effectively compensates for the encoder’s limitations in modeling the periodic change of TC environmental factors patterns.

2.4. LSTM Network

In TC track prediction, the dynamic turn in the track is not only influenced by long-term trends but also exhibits significant short-term dependencies. In particular, moments of sudden shifts in the TC track require a more focused learning of short-term dependencies. Although the Informer encoder and FECAM block have captured the global features of the time series and the periodic change of environmental meteorological factors patterns, their performance in capturing short-term dependencies still shows some limitations. Specifically, for the rapid change of variables such as wind speed and pressure at local time steps in the TC track, relying solely on the Informer encoder and frequency domain analysis may fail to capture the fine-grained dynamic information. To address this, the model introduces an LSTM network after FECAM, focusing on enhancing short-term dependencies and local dynamic features, thereby further improving the model’s ability to accurately predict the TC track.

LSTM is a classic variant of RNN that effectively addresses the gradient vanishing and explosion issues in traditional RNN for long-sequence tasks by introducing gating mechanisms. In the TC track prediction task, the LSTM module is placed after the FECAM block to model the short-term dependencies and dynamic changes of environmental factors in the time series. By processing input features step by step, the LSTM can extract local dynamic features of variables such as wind speed and pressure along the track, while preserving key long-term dependency information.

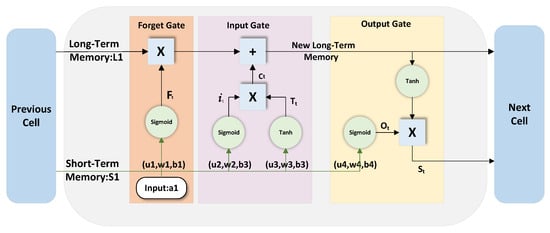

As shown in Figure 5, the input to the LSTM includes the feature at the current time step, the hidden state , and the memory state from the previous time step, with being the output feature from the FECAM block. The output consists of the hidden state at the current time step and the updated memory state . This mechanism ensures the flow of information between consecutive time steps in the time series while dynamically updating the key feature representations.

Figure 5.

The cell structure of LSTM.

In the internal processing flow, the LSTM consists of three main gating mechanisms [34]: the forget gate, the input gate, and the output gate. The forget gate is responsible for selectively retaining or discarding the memory state from the previous time step, the input gate controls the writing of new information, and the output gate determines the update of the hidden state. The specific calculations are as follows:

Forget Gate: Determines which information in the previous time step’s memory state should be retained or discarded:

where is the output of the forget gate, and is the Sigmoid activation function.

Input Gate: Selects the new information to be written into the memory state at the current time step:

Simultaneously, it computes the candidate memory information:

Memory State Update: The memory state for the current time step is updated through the forget and input gates:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

Output Gate: Determines the output of the hidden state, generating the time step feature based on the current memory state:

Through this series of gating operations, LSTM captures short-term dynamic features in time series while effectively memorizing long-term dependencies, preventing interference from redundant or irrelevant information. The primary role of LSTM is to model the local dynamic characteristics in the TC track, such as the impact of wind speed and pressure change at specific time steps on track deviation. Combined with the frequency-domain enhanced features provided by the FECAM block, LSTM further strengthens the temporal dependencies in the time series, generating accurate feature representations for the subsequent decoder module.

2.5. Informer Decoder

The primary task of the Informer decoder is to combine the global features output by the encoder with the historical information of the target sequence, generating predictions for the future TC track step by step. In the TC track prediction task, the decoder captures the short-term dependencies and the interaction between global features through a dynamic attention mechanism, ensuring the temporal continuity and spatial accuracy of the predictions.

The input to the decoder consists of two parts: first, the global feature representations extracted by the Informer encoder, and second, the known historical values of the target sequence. After position encoding, the historical part of the target sequence is combined with the encoder features, and through multi-layer dynamic modeling, the decoder generates the predicted results. Unlike the encoder’s input, the decoder guides the future predictions using the historical values of the target sequence, further enhancing the model’s accuracy. The core components of the decoder include the Masked ProbSparse Self-Attention mechanism and the Multi-head Attention Mechanism. Together, they ensure that the decoder captures short-term dynamic turning while also incorporating the global context from the encoder during the prediction process.

2.5.1. Masked ProbSparse Self-Attention Block

The Masked ProbSparse Self-Attention Mechanism models the historical part of the target sequence. This mechanism ensures that each time step can only access its preceding historical information through the mask operation, preventing future information leakage. The decoder uses a masked matrix M to constrain the self-attention calculation:

The mask ensures that during the prediction at time step i, the model can only access the historical information up to time step , as shown in the Masked ProbSparse Self-Attention Block in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The structure of Informer decoder.

The attention weight calculation method is similar to the one used in the encoder, where Sparse Attention weights are computed under the mask constraint:

where , are the query and key matrices for the decoder input, and is the sparsified attention weight matrix. Using the selection strategy, the top U most important items are retained for each row. For example, when predicting time step , the model can only rely on information from time step t and earlier. Specifically, the mask operation sets the attention weights for future time steps to negative infinity, ensuring that after the Softmax operation, these weights become zero.

2.5.2. Layer Normalization

The main purpose of Layer Normalization is to address the issue of Internal Covariate Shift, which arises due to change in the input distribution of the network layers during training. Its core idea is to normalize the activations of all neurons in a given layer for each sample, ensuring that the input distribution of each layer remains stable, thus accelerating training convergence and improving the model’s generalization ability.

After the Masked ProbSparse Self-Attention, the decoder introduces Layer Normalization (LayerNorm) to stabilize training and improve the model’s convergence speed. The calculation of LayerNorm is as follows:

where H represents the input features, and are the mean and standard deviation of the features, and and are learnable parameters. Through Layer Normalization, the Informer decoder can reduce internal covariate shift, thereby enhancing the stability of training.

2.5.3. Self-Attention Block

After Layer Normalization, the data enters the Self-Attention Block, further enhancing feature representation. On the basis of modeling the historical values of the target sequence, the decoder uses the encoder-decoder Multi-head Attention mechanism to combine the short-term dynamic features of the target sequence with the global features from the encoder. Specifically, the query matrix Q comes from the decoder, and the key matrix K and value matrix V come from the encoder’s global feature representation:

This mechanism captures the time-step relationships between the target sequence and the encoder features, generating a context representation that integrates both short-term and long-term features. After the self-attention computation, the decoder’s output features pass through a Fully Connected Layer () to map the high-dimensional features to the final prediction result, i.e., the future latitude and longitude of the TC track:

3. Results

In this section, we mainly present the experimental dataset and the comparison results of various metrics for TC track prediction to validate the performance of the proposed model. The experiments were conducted on a workstation with an Intel® Core™ i7-6498 DU CPU@2.50 GHz and 256 GB of main memory. All deep learning methods were implemented using Python 3.6 and several open-source machine learning libraries, including scikit-learn 0.20.3 and TensorFlow 2.1.

3.1. Dataset

This experiment utilizes a comprehensive TC track dataset covering the Western North Pacific (WNP) region. The dataset is a collaborative effort between the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) [35] and the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) [36]. The dataset contains records of all TC tracks from 1951 to 2022, including detailed TC track and associated meteorological factors. The dataset covers the genesis, development, movement, and dissipation processes of thousands of TCs, comprising over 60,000 timestamped records. Each record includes key features such as the TC center’s latitude and longitude, maximum wind speed, minimum sea-level pressure (MSLP), storm classification, storm radius, and wind intensity. The records are sampled at 6-h intervals, capturing the critical time points throughout the lifecycle of each TC.

Specifically, each record includes the following features: TCID, name, timestamp, center longitude and latitude, minimum pressure, maximum wind speed, wind circles Radius (Radius30, Radius50, and Radius70), movement speed, movement direction, and TC classification.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, as shown in Table 1, the dataset was randomly divided into training and testing sets, with 90% of the TC records used for training and the remaining 10% for testing. After removing records with missing or incomplete data, a total of 1748 TCs were used for training, and 195 TCs were reserved for testing.

Table 1.

The detailed experiment dataset.

To ensure the statistical reliability of the results and mitigate any bias introduced by a single random split, as shown in Table 2, we employed a 10-fold cross-validation strategy. The entire dataset (1943 TCs) was partitioned into ten subsets. In each round, one subset was utilized for testing while the remaining nine served as the training set. The final performance metrics reported are the averages across these ten independent folds.

Table 2.

The 10-fold cross-validation results (APE, unit: km) of LFInformer at different forecast horizons.

3.2. Performance Measurements

The objective evaluation metrics used in this study include Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and Average Positioning Error (APE). MAE represents the average of the absolute differences between the predicted values and the observed values. It is calculated as follows:

where n is the number of records in the test set, is the predicted value, and is the observed value, A larger MAE indicates poorer model performance.

RMSE is the square root of the ratio between the squared deviations of predicted values from the actual values and the number of observations. It is defined as:

MAPE represents the average percentage error of the predictions relative to the actual values. It takes into account both the magnitude of the prediction error and its proportion relative to the actual track. A MAPE value of 0 indicates a perfect model, while values greater than 1 suggest poorer performance. It is calculated as:

APE is calculated using the formula below, where R is the radius of the Earth, , represent the actual latitude and longitude of the tropical cyclone, and , represent the predicted position. APE measures the distance between the actual and predicted positions, with the unit being kilometers. A smaller APE indicates better model performance.

3.3. Experimental Results

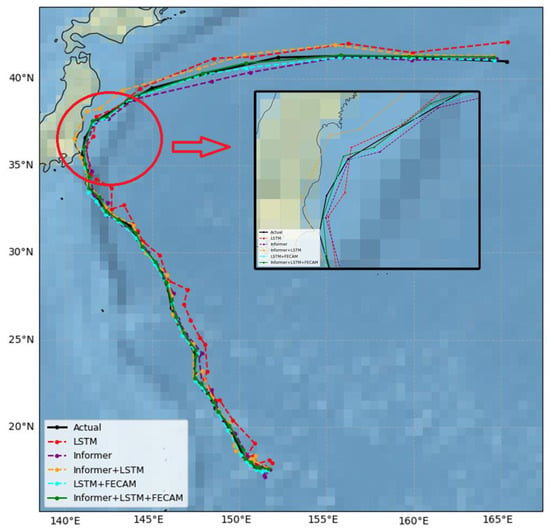

3.3.1. Ablation Experiments

To evaluate the performance of each major network component designed in this study for TC track prediction, we conducted ablation experiments with different module combinations. The evaluation metrics include MAE, RMSE.

Table 3 presents the results of the ablation study. Taking the 6-h TC prediction experiment as an example, the prediction performance improves significantly as more modules are added to the model configuration. When the LSTM module is used alone, it can handle short-term dependencies in TC track. However, the MAE and RMSE values for both longitude and latitude predictions remain relatively high, indicating that the model has considerable errors in capturing the dynamic turning in TC track. In contrast, the Informer model demonstrates significant advantages in the 6-h TC track prediction task due to its powerful ability to capture global dependencies. Notably, the prediction performance shows clear improvements in RMSE, indicating that the Informer model is more effective in capturing the long-term trends of TC track. By combining the Informer and LSTM modules, the prediction accuracy is further improved, particularly with significant reductions in MAE and RMSE values. This demonstrates that the integration of both modules effectively compensates for the limitations of individual models in capturing short-term and long-term dependencies. When the LSTM module is combined with the FECAM block, the model’s capability to handle the periodic change of meteorological factors patterns in TC track is further enhanced, resulting in lower RMSE values. This highlights FECAM’s role in improving the model’s sensitivity to the cyclical fluctuations of the meteorological environment. Ultimately, the combination of the Informer, LSTM and FECAM achieves the best performance across all evaluation metrics, especially with notable improvements in metrics.

Table 3.

Taking 6-h typhoon track prediction as an example, we conduct a comparative evaluation of different module combinations and the evaluation based on MAE (°) and RMSE (°) metrics, bold values indicate the best performance for each metric.

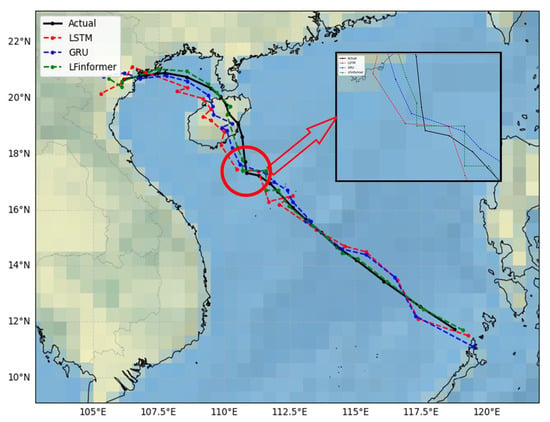

In summary, with the continuous optimization of the model architecture and the enhancement of its components, the accuracy of TC track prediction has been significantly improved. Our proposed model (Informer + LSTM + FECAM) achieves the best prediction performance across all evaluation metrics. The results presented in Table 3 validate the effectiveness of each component in the LFInformer model. As more modules are integrated, the model performance improves consistently, fully demonstrating the synergistic effects among the components and providing strong support for further enhancing prediction accuracy. In addition, the visual comparison in Figure 7 highlights the path prediction differences across module combinations. An inset around the turning point highlights the differences, where other module combinations show larger deviations. The proposed model aligns best with the actual track, visually validating its superior performance.

Figure 7.

The visualization of ablation experiments.The red circle highlights the key turning point region of the typhoon track, and the red arrow indicates the corresponding zoomed-in view shown in the inset box. The inset allows for a detailed comparison of different models’ performances in this critical area.

3.3.2. Comparison Experiment

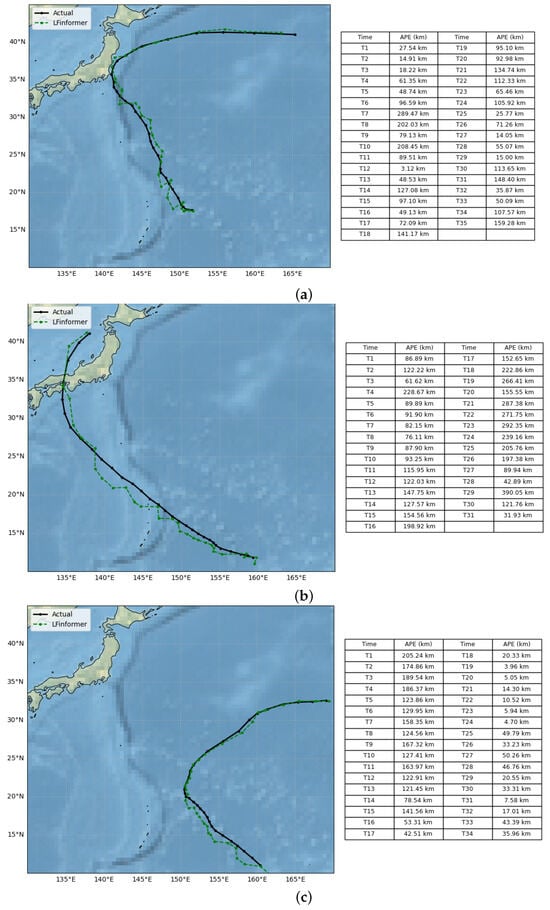

This section presents a performance comparison between the LFInformer model and traditional deep learning methods (such as RNN, GRU, LSTM, and Transformer) in TC track prediction. To comprehensively evaluate the predictive capabilities of each model, we selected multiple forecasting time steps (6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h) and calculated the Absolute Position Error (APE) for each method. The main objective of this experiment is to verify whether the LFInformer model can achieve more accurate TC track predictions than traditional methods across different time scales, particularly in longer-term forecasts.

As shown in Table 4, the LFInformer model achieved APE values of 72.39 km and 117.72 km for the 6-h and 12-h forecasts, respectively, which are significantly lower than those of other models. For instance, the APE of the RNN model was 106.76 km for the 6-h prediction, while GRU, LSTM, and Transformer recorded 94.81 km, 89.68 km, and 86.73 km, respectively. These results indicate that LFInformer demonstrates outstanding performance in short-term predictions, effectively capturing local variations in TC track. As the prediction horizon increases, although all models experience a rise in prediction error, LFInformer maintains relatively stable performance. In the 48-h forecast, LFInformer achieves an APE of 168.64 km, which is slightly lower than that of LSTM and Transformer, showcasing its advantage in long-term track prediction.To further illustrate the model’s prediction performance, Figure 8 presents the APE of LFInformer at each forecast step, showing its stable accuracy across time and its ability to maintain low errors during sudden track changes.

Table 4.

APE metric comparison: LFInformer versus deep learning methods for TC prediction in the future of 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h, bold values indicate the best performance for each metric.

Figure 8.

APE visualization of 12-h track predictions: (a) TC “Shanshan” (2018), (b) TC “Cimaron” (2018), (c) TC “Halong” (2019).

Furthermore, we analyze and compare the multi–lead-time errors. Table 5 reports the APE at 12, 24, and 48 h for the proposed model and the traditional baselines. At short and medium leads, our errors are still higher than recent operational forecasts, reflecting the advantage of operations in real-time data assimilation and multi-source predictors. At 48 h, however, the proposed model attains 168.64 km, already close to operational skill and lower than all learning baselines, indicating clear potential for longer-range track prediction.

Table 5.

APE metric comparison: LFInformer versus deep learning methods for TC prediction in the future of 12, 24, and 48 h, bold values indicate the best performance for each metric.

In summary, LFInformer demonstrates high prediction accuracy across all forecast horizons for TC track prediction, with particularly superior performance in short-term forecasts.

Table 6 presents a comparison of the objective evaluation metrics—MAE, RMSE, and MAPE—across the RNN, GRU, LSTM, Transformer, and LFInformer models. Taking the 6-h forecast of tropical cyclone positions as an example, the best results are highlighted in bold. As shown in Table 6, the LFInformer model consistently outperforms the other models across all three metrics. Specifically, LFInformer achieves a MAE of 0.555, RMSE of 0.623, and MAPE of 0.585, which are significantly lower than those of RNN and GRU. Compared to LSTM and Transformer, LFInformer also shows notable advantages in MAE and RMSE, indicating its superior ability to capture the dynamic variations in TC track and reduce prediction errors.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of LFInformer versus conventional deep learning approaches (RNN, GRU, LSTM, Transformer) in 6-h typhoon forecasting: evaluation based on MAE (°), RMSE (°), and MAPE (°) metrics, bold values indicate the best performance for each metric.

Additionally, LFInformer excels in the MAPE metric, with a value of 0.585, which is significantly lower than that of LSTM and Transformer. This demonstrates that LFInformer has a strong ability to capture relative errors in TC track predictions. LFInformer not only performs excellently in short-term predictions but also consistently maintains lower error values in medium- and long-term predictions, with a particularly notable improvement in MAPE.

Based on the analysis of these experimental results, LFInformer outperforms traditional deep learning methods across multiple evaluation metrics, demonstrating its superiority in the TC track prediction task. This confirms that by combining the long-sequence processing capabilities of Informer, the short-term handling capabilities of LSTM, and the modeling of periodic change through FECAM, the model can effectively improve the accuracy and stability in capturing TC track variations.

Taking the prediction of the TC’s position for the next 48 h as an example, Table 7 presents a comparison of the RNN, GRU, LSTM, Transformer, and LFInformer models based on objective evaluation metrics such as MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, analyzing their predictive performance in both longitude and latitude directions, This indicates that while traditional models perform well in short-term predictions, their accuracy significantly decreases over longer time horizons, such as in the 48-h TC track prediction. Particularly in the latitude direction, the MAPE of Transformer and LSTM are 3.221 and 3.132, respectively, while LFInformer achieves a lower value of 2.276, demonstrating a significant improvement in prediction accuracy.

Table 7.

Comparative analysis of LFInformer versus conventional deep learning approaches (RNN, GRU, LSTM, Transformer) in 48-h typhoon forecasting: evaluation based on MAE (°), RMSE (°), and MAPE (°) metrics, bold values indicate the best performance for each metric.

Specifically, LFInformer exhibits lower MAE, RMSE, and MAPE values in both the longitude and latitude directions compared to other models. In particular, in terms of MAPE, LFInformer achieves the lowest values of 2.557 and 2.276 in longitude and latitude, respectively, while the MAPE of other models is generally higher than that of LFInformer, indicating LFInformer’s outstanding performance in reducing relative errors. This further demonstrates that LFInformer, by integrating the advantages of LSTM and Informer and introducing the FECAM, can effectively improve the accuracy of TC track prediction, especially in long-term prediction tasks.

Through comparative analysis, LFInformer demonstrated stronger resistance to interference and better performance in the 48-h prediction task. Compared to deep learning models such as LSTM and Transformer, it provides more accurate predictions. Experimental results show that LFInformer not only effectively improves prediction accuracy but also maintains reasonable control over computational complexity, making it suitable for long-term TC track prediction tasks in practical applications.

Beyond prediction accuracy, we further evaluated the model’s efficiency by measuring the average inference time per sample. As shown in Table 8, the LFInformer achieves an inference latency of 5.89 ms. While this incurs a slight computational cost compared to the baseline Informer (4.85 ms) attributed to the integration of the FECAM and LSTM components, it remains substantially faster than the standard Transformer (12.56 ms). This validates the design choice of using an Informer backbone to ensure high efficiency without compromising the enhanced predictive capability.

Table 8.

Comparison of Average Inference Time of Different Models.

3.3.3. Visualization Experiment

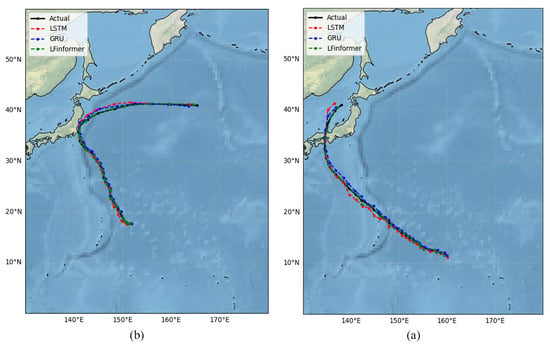

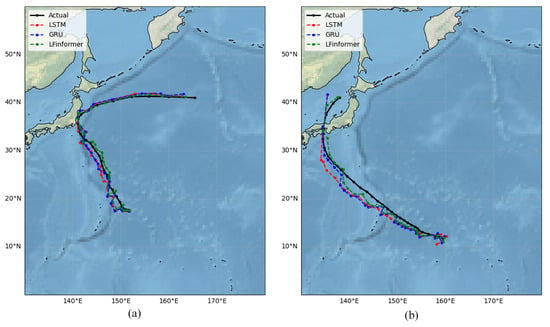

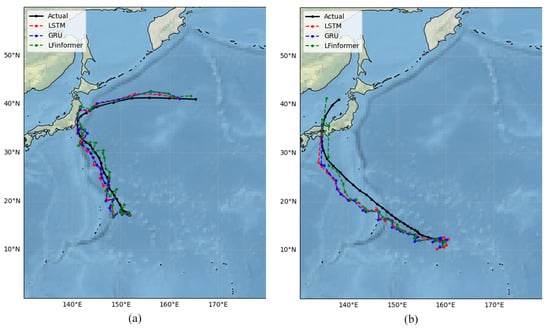

To further demonstrate the performance of the proposed model in TC track prediction, particularly in predicting track mutation points, we used visualization to compare the predictions of LSTM, GRU, LFInformer, and the observed cyclone track for 6-h, 12-h, and 48-h forecasts. Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the predicted track for TCs “Shanshan” (2018) and “Cimaron” (2018).

Figure 9.

6 h forecast results (markers denote 6-h intervals): (a) Track prediction of TC “Shanshan” (2018). (b) Track prediction of TC “Cimaron” (2018).

Figure 10.

12 h forecast results (markers denote 6-h intervals): (a) Track prediction of TC “Shanshan” (2018). (b) Track prediction of TC “Cimaron” (2018).

Figure 11.

48 h forecast results (markers denote 6-h intervals): (a) Track prediction of TC “Shanshan” (2018). (b) Track prediction of TC “Cimaron” (2018).

In the 6-h prediction results, all models broadly reproduced the synoptic-scale evolution of TC trajectories; in particular, for TCs ”Shanshan” and “Cimaron”, The predicted tracks closely matched the observed paths, whereas LFInformer achieved the lowest overall displacement error, indicating more accurate short-term TC track prediction and better ability to capture the sudden track changes in the TC track.

In the 12-h prediction results, although all models showed some deviation in the predicted track, LFInformer still managed to capture the TC track’s trend more effectively. For TC “Cimaron”, LFInformer stood out, showing the smallest deviation from the actual track, and for TC “Shanshan”, LFInformer demonstrates superior performance in medium-range forecasts, capturing localized dynamic turns in TC tracks more accurately than competing models.

For the 48-h prediction results, all models started to show significant deviations in their predicted tracks, especially for TC “Shanshan”, where the predictions from other models deviated notably from the actual track. However, LFInformer still performed relatively stably, particularly in the case of TC “Cimaron”, where LFInformer’s predicted track had the smallest difference from the observed track. This demonstrates LFInformer’s strong stability and error saturation in long-term time series predictions.

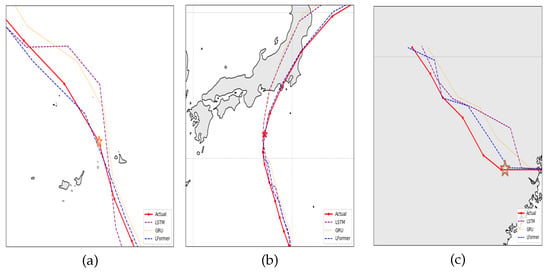

3.3.4. Research on Critical Turning Points

The above results validate that the LFInformer model, through the synergistic design of the FECAM and the ProbSparse Self-Attention mechanism, significantly improves its ability to predict sudden turning in TC track. To further demonstrate the model’s attention to track turning points, three representative cases were selected, all of which historically exhibited pronounced track deviations: TC “Hagibis” (2019) [37], TC “Lekima” (2019) [38], and TC Maria (2018) [39]. Among them, the turning point of “Lekima” occurred over the ocean, that of “Hagibis” occurred just before landfall, and that of Maria occurred after landfall. As shown in Figure 12, the proposed model exhibits notable advantages in predicting track turning points, which are marked by red pentagrams.

Figure 12.

(a) Local map of track turning points for TC “Lekima” (2019) (b) Local map of track turning points for TC “Hagibis” (2019) (c) Local map of track turning points for TC “Maria” (2018). The red pentagrams symbols represent the turning points of the TC track.

For example, in the northwestward turning event of TC “Lekima” shown in Figure 12a, the unexpected breakdown of the subtropical high led to a sudden turning in the TC’s movement direction. Through the collaborative mechanism of FECAM and the ProbSparse Self-Attention, the LFInformer model is able to detect subtle turning in the ridge line of the subtropical high in advance. As a result, the predicted track closely follows the actual track near the turning point, demonstrating strong robustness. In contrast, LSTM and GRU fail to reflect the shift in TC trends, as their predictions continue to follow a northward inertial track due to their neglect of the periodic change of atmospheric circulation. This case highlights that the ProbSparse Self-Attention mechanism in the proposed model effectively selects the most relevant time steps from long historical sequences through a sparsity strategy, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy. In the case of TC “Hagibis” shown in Figure 12b, the TC’s track exhibited a significant northeastward turn during the forecast period due to the sudden intensification of the westerly jet stream [40]. The predicted track of the proposed LFInformer model (blue) almost completely overlaps with the actual track (red) at this turning point, demonstrating accurate detection of the sudden turning of track. This performance is attributed to the model’s internal frequency-domain enhancement module, which amplifies the periodic features of the westerly trough, and the ProbSparse Self-Attention mechanism, which emphasizes critical turning points. In contrast, LSTM and GRU, limited by their short-term memory characteristics, failed to effectively respond to the long-term evolution of the circulation system, resulting in continued northwestward deviation after the turning point and significant departure from the actual track. In the case of TC “Maria” shown in Figure 12c, the TC experienced a turning event after landfall due to the influence of inland convection, affecting pressure, wind speed, and wind direction. The proposed model still managed to accurately track and predict this turning point.

Figure 13 compares the predicted tracks of LSTM, GRU, and the proposed LFInformer with the observed track for TC “Lionrock”. As a canonical abrupt re-curvature event, “Lionrock” provides a stringent test of a model’s sensitivity to turning cues along the track. The cyclone exhibited an abrupt northward re-curvature over the northern South China Sea. While all baselines roughly follow the pre-turn southwesterly leg, they fail to respond promptly to the regime shift at the second turning point. Following the turning point, the LSTM and GRU models tend to retain a west–northwest heading for several steps, which manifests as a left-sided cross-track bias with respect to the observed track. By contrast, LFInformer changes heading earlier and keeps closer to the observed segment after the turning, yielding a visibly smaller cross-track error. In the inset around the second turning point. The enlargement highlights that LFInformer begins its northward adjustment within one–two time steps of the observed turn and then stays nearly on the right of the observed track, avoiding the overshoot seen in the baselines. This behavior is consistent with our design: the FECAM block enhances frequency-domain cues associated with the evolving steering flow, and the ProbSparse self-attention selectively focuses on the most informative historical steps, enabling earlier and more robust detection of the turning signal.

Figure 13.

Case study of TC “Lionrock” (2021): model comparison for the abrupt northward re-curvature. The red circle highlights the key turning point region of the typhoon track, and the red arrow indicates the corresponding zoomed-in view shown in the inset box. The inset allows for a detailed comparison of different models’ performances in this critical area.

The above experiments demonstrate that the proposed LFInformer performs excellently in predicting complex TC movement track. The predicted tracks of the model closely match the actual track at turning points, further validating the effectiveness of the FECAM and ProbSparse Self-Attention mechanisms in joint modeling across frequency and time domains. The synergistic effect of the Frequency-domain Enhanced Channel Attention Mechanism and the ProbSparse Self-Attention mechanism provides a reliable theoretical foundation and technical support for accurately forecasting sudden turning in TC tracks.

4. Conclusions

In this study, in light of the limitations faced by current deep learning models in TC prediction—such as single-feature fusion and the difficulty of balancing short-term and long-term track forecasting, particularly in predicting sudden turning of track.we propose a hybrid deep learning model based on the Informer architecture, integrated with both FECAM block and LSTM modules, to enable accurate TC track prediction. The Informer module captures long-term dependencies. The LSTM focuses on short-term temporal features. FECAM, using frequency-domain enhanced channel attention, models the track’s sensitivity to periodic meteorological environment patterns change. Overall, the proposed model efficiently handles complex TC time series data and achieves accurate track prediction.

This study conducted extensive experiments based on the JMA and IBTrACS dataset, including 6-h, 12-h, 24-h, and 48-h track predictions. The experimental results demonstrate that, compared with traditional models, the proposed model exhibits superior performance in short-term, mid-term, and long-term track predictions, especially in capturing the global trends and local dynamic turning of TC track. Ablation studies further validate the importance of the LSTM and FECAM block within the overall framework, indicating that the synergy among modules effectively enhances the comprehensive performance of the model.

Nevertheless, Several limitations should be noted. Firstly, the current model focuses solely on TC track prediction, without addressing other key TC characteristics such as wind speed and atmospheric pressure. Secondly, for TCs with significant intensity fluctuations, the model’s predictions still exhibit noticeable deviations. In addition, the forecasting time range can be further extended to fully leverage the model’s long-sequence prediction capability, and the ability to predict over longer periods remains to be further explored. Future research will extend LFInformer toward joint track–intensity forecasting by incorporating intensity indicators as additional prediction targets. Specifically, we will adopt a multi-task design with a shared Informer–FECAM–LSTM backbone and separate output heads for track and intensity, and enrich the inputs with intensity-related environmental factors to better represent the physical drivers of intensity changes. We will further investigate appropriate loss balancing between track and intensity objectives and evaluate intensity performance using standard MAE/RMSE metrics alongside track APE, aiming to improve long-term prediction of both TC track and characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M. and L.Z.; methodology, F.M. and L.Z.; software, F.M.; validation, F.M., X.X. and L.Z.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, F.M. and X.X.; resources, L.Z.; data curation, F.M. and X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M. and X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X. and L.Z.; visualization, F.M. and X.X.; supervision, L.Z.; project administration, L.Z.; funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Typhoon Research Foundation from Shanghai Typhoon Institute of China Meteorological Administration under Grant TFJJ202208.

Data Availability Statement

JMA data are available at the Japan Meteorological Agency RSMC archive JMA track archives (https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/jma-eng/jma-center/rsmc-hp-pub-eg/trackarchives.html) (accessed on 26 December 2024). IBTrACS data are available from NOAA NCEI IBTrACS (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/international-best-track-archive) (accessed on 26 December 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, L.; Liu, Q. Tropical cyclone damages in China 1983–2006. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2009, 90, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Meteorological Administration. China Climate Bulletin 2017; China Meteorological Administration: Beijing, China, 2018; Available online: https://www.wmc-bj.net/publish/cms/2e8413abe9d443aba2bec7ed6b2946d2/index.html (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Barnes, M.D.; Hanson, C.L.; Novilla, L.M.; Meacham, A.T.; McIntyre, E.; Erickson, B.C. Analysis of media agenda setting during and after Hurricane Katrina: Implications for emergency preparedness, disaster response, and disaster policy. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, M. Dynamical aspects of typhoon formation. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 1961, 39, 282–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C.J. An Alternate to the HURRAN Tropical Cyclone Forecast System; NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS SR-62; NOAA National Weather Service: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1972. Available online: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/3605 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Al-Yahyai, S.; Charabi, Y.; Gastli, A. Review of the use of numerical weather prediction (NWP) models for wind energy assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Marshall, J.; Leslie, L.; Morison, R.; Pescod, N.; Seecamp, R.; Spinoso, C. Recent developments in the continuous assimilation of satellite wind data for tropical cyclone track forecasting. Adv. Space Res. 2000, 25, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, H.N.; Thanh, N.P.T.; Thanh, H.V.; Thanh, H.P.; Tuan, L.T.; Thi, T.D.; Duy, T.T.; Phuong, H.N.T. Development of an R-CLIPER model using GSMaP and TRMM precipitation data for tropical cyclones affecting Vietnam. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 1241–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boston, MA, USA, 6–9 August 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1597–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Dong, P.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, J.; Liu, K. A novel data-driven tropical cyclone track prediction model based on CNN and GRU with multi-dimensional feature selection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 97114–97128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Dong, P.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, J. A novel deep learning approach for tropical cyclone track prediction based on auto-encoder and gated recurrent unit networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.H. Analysis of gradient vanishing of RNNs and performance comparison. Information 2021, 12, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.S.; Venkataraman, V.; Meganathan, S.; Krithivasan, K. Tropical cyclone intensity and track prediction in the Bay of Bengal using LSTM-CSO method. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81613–81622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.; Tan, F. Bidirectional grid long short-term memory (bigridlstm): A method to address context-sensitivity and vanishing gradient. Algorithms 2018, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhao, P.; Pan, B.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xu, J.; Zhong, S.; Shi, Z. A nowcasting model for the prediction of typhoon tracks based on a long short term memory neural network. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2018, 37, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.; Wang, X.; Fu, J.; Chan, P.; He, Y. Short-term prediction of the intensity and track of tropical cyclone via ConvLSTM model. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2022, 226, 105026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandadi, T.; Shankarlingam, G. Drawbacks of lstm algorithm: A case study. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 11106–11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chu, J.E.; Ham, Y.G. Enhancing tropical cyclone track and intensity predictions with the OWZP-Transformer model. npj Artif. Intell. 2025, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Willson, M.; Wirnsberger, P.; Fortunato, M.; Alet, F.; Ravuri, S.; Ewalds, T.; Eaton-Rosen, Z.; Hu, W.; et al. Learning skillful medium-range global weather forecasting. Science 2023, 382, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Brandstetter, J.; Kapoor, A.; Gupta, J.K.; Grover, A. ClimaX: A foundation model for weather and climate. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/7181-attention-is-all-you-need (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I. Generating long sequences with sparse transformers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.10509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jin, X.; Xuan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.X.; Yan, X. Enhancing the locality and breaking the memory bottleneck of transformer on time series forecasting. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Beltagy, I.; Peters, M.E.; Cohan, A. Longformer: The long-document transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.05150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.H.H.; Bai, S.; Yamada, M.; Morency, L.P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Transformer dissection: A unified understanding of transformer’s attention via the lens of kernel. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevert, D.A.; Unterthiner, T.; Hochreiter, S. Fast and accurate deep network learning by exponential linear units (elus). arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.07289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Koltun, V.; Funkhouser, T. Dilated residual networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 472–480. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_cvpr_2017/papers/Yu_Dilated_Residual_Networks_CVPR_2017_paper.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Gupta, A.; Rush, A.M. Dilated convolutions for modeling long-distance genomic dependencies. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.01278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Qin, M.; Sun, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.K.; Ren, F. Learning in the frequency domain. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1740–1749. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_CVPR_2020/papers/Xu_Learning_in_the_Frequency_Domain_CVPR_2020_paper.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Foster, J.; Richards, F. The Gibbs phenomenon for piecewise-linear approximation. Am. Math. Mon. 1991, 98, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shizgal, B.D.; Jung, J.H. Towards the resolution of the Gibbs phenomena. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2003, 161, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.Y.; Wong, W.K.; Woo, W.C. Convolutional lstm network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 1. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2015/file/07563a3fe3bbe7e3ba84431ad9d055af-Paper.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Kitamoto, A.; Hwang, J.; Vuillod, B.; Gautier, L.; Tian, Y.; Clanuwat, T. Digital typhoon: Long-term satellite image dataset for the spatio-temporal modeling of tropical cyclones. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 40623–40636. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/file/7fc36bce5de315751001981baaf4751a-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Knapp, K.R.; Kruk, M.C.; Levinson, D.H.; Diamond, H.J.; Neumann, C.J. The international best track archive for climate stewardship (IBTrACS) unifying tropical cyclone data. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 91, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Tomita, T. Investigating the effects of super typhoon HAGIBIS in the Northwest Pacific Ocean using multiple observational data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Chen, P.; Yang, S.; Zheng, F.; Yu, H.; Tang, J.; Lu, Y.; Chen, G.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. The impact of Typhoon Lekima (2019) on East China: A postevent survey in Wenzhou city and Taizhou city. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 16, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Lin, L.; Zhao, B.; Wu, D.; Xia, W.; Xu, B. Distinct raindrop size distributions of convective inner-and outer-rainband rain in Typhoon Maria (2018). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2020JD032482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanase, W.; Araki, K.; Wada, A.; Shimada, U.; Hayashi, M.; Horinouchi, T. Multiple dynamics of precipitation concentrated on the north side of Typhoon Hagibis (2019) during extratropical transition. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 2022, 100, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.