Featured Application

This study presents a GIS-based and explainable machine learning framework for screening heavy metal enrichment in agricultural topsoils at the field scale using only routine soil indicators. Farm managers and environmental agencies can use the Heavy Metal Enrichment Index (HMI) and associated field maps to identify persistently enriched fields and emerging hot spots, prioritize follow-up sampling, and focus management review on locations where enrichment signals are most consistent. Because the framework relies on widely available laboratory measures of soil acidity (pH in H2O and pH in KCl) and humus content, it is suitable for operational monitoring programs and can be extended by incorporating satellite-derived covariates to support scalable screening in data-limited regions, including Central Asia.

Abstract

Heavy metal enrichment in agricultural soils can affect crop safety, ecosystem functioning, and long-term land productivity, yet farm-scale screening is often constrained by limited routine monitoring data. This study develops a GIS-based framework that combines field-scale spatial analysis with explainable machine learning to characterize and predict heavy metal enrichment on an intensively managed cereal farm in eastern Kazakhstan. Topsoil samples (0 to 20 cm) were collected from 34 fields across eight campaigns between 2020 and 2023, yielding 241 composite field–campaign observations for eight metals (Pb, Cu, Zn, Ni, Cr, Mo, Fe, and Mn) and routine soil properties (humus, pH in H2O, and pH in KCl). Concentrations were generally low but spatially heterogeneous, with wide observed ranges for several elements (for example, Pb 0.06 to 2.20 mg kg−1, Zn 0.38 to 7.00 mg kg−1, and Mn 0.20 to 38.0 mg kg−1). We synthesized multi-metal structure using an HMI defined as the unweighted mean of z-standardized metal concentrations, which supported field-level screening of persistent enrichment and emerging hot spots. We then trained Extreme Gradient Boosting models using only humus and pH predictors and evaluated performance with field-based spatial block cross-validation. Predictive skill was modest but nonzero for several targets, including HMI (mean R2 = 0.20), indicating partial spatial transferability under conservative validation. SHAP analysis identified humus content and soil acidity as dominant contributors to HMI prediction. Overall, the workflow provides a transparent approach for field-scale screening of heavy metal enrichment and establishes a foundation for future integration with satellite-derived covariates for broader monitoring applications.

1. Introduction

Heavy metal contamination of agricultural soils has become a critical environmental and food-security issue worldwide. In recent years, geospatial technologies, digital soil mapping (DSM), and machine learning have been increasingly employed to characterize the spatial distribution of heavy metals and to support risk assessment. For example, Liu et al. used multiple geospatial covariates and deep neural networks to produce high-resolution DSM products for heavy metals, demonstrating the potential of advanced feature selection and deep learning to improve prediction accuracy [1]. Yao et al. exploited hyperspectral satellite imagery to estimate heavy metal concentrations in croplands while explicitly accounting for emission sources and migration pathways, illustrating how remote sensing can capture both pollution levels and transport processes [2]. At larger scales, spatial zoning approaches have been applied to delineate areas with different degrees of heavy metal accumulation in geological high-background regions, facilitating targeted management and land-use planning [3].

Understanding the sources of heavy metals is essential for interpreting spatial patterns and designing mitigation strategies. Integrated source-apportionment frameworks combining geochemical indicators, multivariate statistics and land-use information have been developed for peri-urban agricultural soils [4]. Campus-scale studies have mapped pollution density and source distribution using GIS-based interpolation and hotspot analysis [5], while other work in arid regions has combined GIS with multivariate statistics to distinguish natural from anthropogenic contributions to soil contamination [6]. Source identification has also been linked to hydrological functions, for instance, in the water-source area of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project, where spatial drivers such as land use, topography and proximity to infrastructure strongly control heavy metal distribution [7]. More recently, field-scale investigations in intensively cultivated areas have combined spatial distribution analysis with pollution source identification to support local management decisions.

A growing body of research has revealed that heavy metals in agricultural soils exhibit strong spatial structure across multiple scales, influenced by legacy pollution, parent material, and management practices [8]. Regional studies in Xinjiang, China, highlight the combined roles of geology, irrigation, industrialization, and agricultural inputs in shaping heavy-metal patterns [9]. In rapidly industrializing landscapes, geospatial visualization and ecological risk indices have been used to assess heavy-metal hazards in rice soils near new industrial zones [10]. At the catchment scale, Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi et al. applied digital soil assessment and Random Forest models to analyze the spatial-temporal evolution of heavy metals in arid soils, demonstrating that machine learning can capture both spatial gradients and temporal trends [11]. Complementary work has used mixed-effects models, land-use regression, and GIS-based ecological-risk frameworks to analyze heavy-metal contamination and associated exposure pathways in agricultural regions [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. In arid ecosystems, adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems coupled with GIS have been proposed as novel tools for predicting heavy-metal contamination from environmental covariates [19], and several regional studies have analyzed the spatial-temporal distribution of heavy metals and their sources in agricultural soils of Northwest China [20,21].

These developments are rooted in and extend the broader DSM literature. Seminal work established the conceptual SCORPAN framework and its application to digital soil mapping, emphasizing the use of environmental covariates for spatial prediction of soil properties [22]. Subsequent initiatives, such as GlobalSoilMap, expanded DSM to continental scales and highlighted the importance of quantifying and validating uncertainties for mapped soil attributes. Recent reviews have synthesized advances in DSM methods and applications, including the integration of machine learning, remote sensing, and proximal sensing, as well as challenges related to scale, data quality, and model interpretability. Within this context, studies on heavy-metal contamination increasingly adopt DSM concepts to generate field-to-regional-scale maps of metal concentrations, enrichment indices, and associated risks [23,24,25,26,27].

Remote sensing has emerged as a significant source of covariates for heavy-metal assessment. Hyperspectral inversion models have been used to study spatial heterogeneity of heavy metals in lake-adjacent soils, and remote-sensing and GIS techniques have been combined to evaluate soil degradation and heavy-metal hazards in cultivated deltas [28]. More recent work integrates hyperspectral and geochemical data with dimensionality-reduction techniques to estimate soil arsenic contamination [29,30,31], develops comprehensive reviews of hyperspectral remote sensing for soil heavy-metal inversion [32], and applies projection-pursuit and gradient-boosting models to predict heavy-metal concentrations in different farmland soils from hyperspectral images [33]. These studies demonstrate that satellite- and UAV-based observations can, in principle, support large-scale monitoring of soil contamination when coupled with appropriate inversion models [34,35,36].

At the same time, there has been a rapid shift from “black-box” machine-learning models towards explainable frameworks that explicitly quantify variable importance and spatial effects. Probabilistic and index-based approaches better represent uncertainty and risk; Aparisi-Navarro et al. proposed a GIS-based pollution index to assess heavy-metal contamination in soils, quantifying exceedance probabilities relative to thresholds [12]. Explainable machine-learning models have been used to reveal synergistic spatial effects in soil heavy-metal pollution [32] and to improve the prediction of metal(loid) concentrations by combining co-kriging with geographically and temporally weighted regression [33]. In parallel, advances in halophyte-mediated metal immobilization provide complementary, process-based remediation options for degraded arid soils [35]. Collectively, these works emphasize the importance of integrating spatial analysis, risk assessment, explainable modelling, and remediation planning across diverse climates and socio-economic contexts.

Despite this progress, several gaps remain. First, many studies focus on regional or catchment scales, with fewer examining field-scale variability within individual farms, where management decisions are made, and remote-sensing data are often aggregated [30]. Second, although machine-learning techniques such as Random Forests, deep neural networks, and gradient boosting are now widely applied, explainable frameworks that clarify how soil properties, management, and environmental factors jointly influence heavy-metal enrichment are still relatively rare [33]. Third, Central Asian agricultural systems—despite their proximity to metallurgical and mining complexes, such as Qarmet JSC in Kazakhstan, remain under-represented in the digital soil contamination literature [26].

Heavy metals in croplands originate from both natural and anthropogenic sources, including parent material, atmospheric deposition, industrial emissions, fertilizers, wastewater irrigation, and domestic waste. These pathways result in both direct soil contamination and indirect inputs via air and water (Figure 1) [29].

Figure 1.

Major sources and pathways of heavy metal release into the environment, including natural, agricultural, industrial, domestic, and miscellaneous inputs [29].

In cereal-based systems, such as wheat, elevated heavy-metal concentrations can induce phytotoxicity and compromise grain quality, ultimately threatening food security and human health [29]. There is therefore a pressing need for farm-scale frameworks that (i) quantify the spatial variability and co-occurrence of multiple heavy metals in agricultural soils, (ii) synthesize this information into interpretable indices of enrichment and risk, and (iii) leverage explainable machine learning to predict metal concentrations from routine soil properties that can later be linked to satellite-derived indicators [2,11,23,31,32,34,36].

In this study, we address these gaps by developing a GIS-based spatial analysis and explainable gradient-boosting framework for heavy-metal enrichment in agricultural soils at the field scale. Using multi-year soil data from 34 fields in an intensively managed farm in eastern Kazakhstan, we first characterize temporal dynamics, field-scale variability, and inter-metal correlations, and construct a composite HMI. We then implement Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) models with field-based spatial block cross-validation to predict individual metal concentrations and the composite index from basic soil properties, and we apply SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values to quantify the contribution of each predictor. Our working hypothesis is that a substantial fraction of the spatial–temporal variability in heavy-metal enrichment can be explained by routine soil attributes, allowing conservative but informative field-scale predictions without direct metal measurements. The novelty of this work lies in (i) its focus on field-level spatial heterogeneity within a single agricultural enterprise, (ii) the integration of GIS-based enrichment mapping with explainable gradient boosting and spatial cross-validation, and (iii) its application to a Central Asian agro-ecosystem that has been largely absent from the digital soil contamination literature. The specific objectives are therefore to: (1) analyze the spatial and temporal patterns of multiple heavy metals in agricultural topsoil; (2) develop and map a composite heavy-metal enrichment index at the field scale; and (3) build and interpret an explainable machine-learning model for predicting heavy-metal enrichment from routine soil properties as a foundation for future integration with remote-sensing covariates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Design

This study was conducted at an intensively managed agricultural enterprise in eastern Kazakhstan (hereafter, Site N), located near Ust-Kamenogorsk and centred at approximately 49.9° N and 82.6° E. The enterprise comprises 34 operational fields cultivated predominantly with spring wheat and other cereal crops. Topsoil was sampled from 0 to 20 cm during eight monitoring campaigns conducted between August 2020 and April 2023.

Within each field and campaign, multiple soil cores were collected along short within-field transects and pooled into a single composite sample following standard agronomic practice. After quality control, 241 composite samples were retained. Each sample corresponds to a unique field and campaign combination and includes laboratory measurements of heavy metals and routine soil properties.

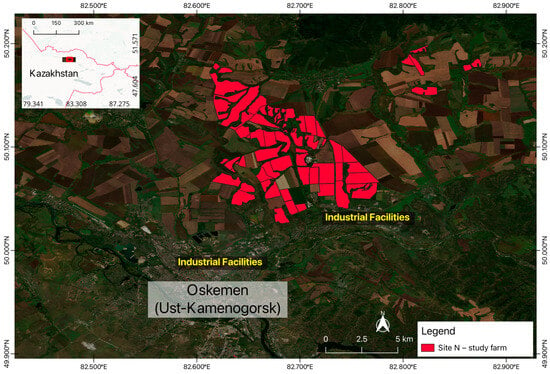

Site N is situated within the broader influence zone of major industrial facilities in the Ust-Kamenogorsk area, including non-ferrous metallurgy, titanium and magnesium production, and uranium and rare-metal processing. These facilities are located approximately 1 to 30 km from the study fields, providing a realistic context for evaluating field-scale variability under potential exposure to both diffuse background inputs and industry-associated contributions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Location of Site N in Eastern Kazakhstan and nearby industrial facilities. The map shows the extent of the 34 agricultural fields, the position of Ust-Kamenogorsk, and several large industrial facilities involved in non-ferrous metallurgy, titanium–magnesium production, and uranium/rare-metal processing, located approximately 1–30 km from the study area. The coordinate grid is provided for reference.

2.2. Laboratory Analyses and Dataset Structure

All samples were air-dried, gently disaggregated, and sieved to 2 mm. Routine soil properties were analyzed in an accredited laboratory using standard agronomic protocols. The routine properties used for modelling in this study were humus content (%), pH measured in water (pH in H2O), and pH measured in potassium chloride (pH in KCl).

Pseudo-total concentrations of eight metals (Pb, Cu, Zn, Ni, Cr, Mo, Fe, Mn) were determined after aqua regia digestion (HCl: HNO3, 3:1 v/v), consistent with common agricultural soil assessment protocols. Pb, Cu, Zn, Ni, and Cr were measured by flame atomic absorption spectrometry, whereas Fe, Mn, and Mo were measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. Concentrations are reported on a dry-mass basis in mg kg−1.

The raw data were stored in Microsoft Excel and imported into R (version 4.5.2) for processing and statistical analysis. Field boundaries were digitized from farm maps and used as the fundamental spatial units. All analyses and inferences therefore refer to the field scale rather than sub-field resolution.

2.3. Data Screening, Missingness Handling, and Exploratory Analysis

Data pre-processing included screening for implausible values, harmonizing variable names and units across campaigns, and ensuring consistent field identifiers. Descriptive analyses were conducted at the campaign and field scales using boxplots to characterize temporal variability and spatial heterogeneity.

Pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to summarize co-occurrence patterns among metals. For metals and , the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated as:

where is the concentration of metal in sample , is the sample mean of metal , and is the number of samples used for the given calculation.

Missingness in predictors relevant to the HMI model is summarized in Table S2. Humus (%) and pH in H2O were complete, whereas pH in KCl contained substantial missingness (89 of 241 records; 36.9%). To avoid artefacts associated with large-scale imputation under non-trivial missingness, predictive modelling that required pH in KCl was conducted on complete-case subsets only (Section 2.8). This yielded an effective modelling sample of observations for the targets reported in the modelling results.

2.4. Metal Standardization and Construction of the Heavy Metal Enrichment Index

To place metals on a comparable scale and summarize multi-metal enrichment, concentrations were standardized to z-scores. For each sample and metal , the standardized value was computed as:

where and are the mean and standard deviation of metal computed across all available samples.

A composite HMI was defined for each sample as the arithmetic mean of standardized concentrations across the metals included:

HMI is used here as a screening-level indicator of relative multi-metal enrichment within Site N, rather than a toxicological or regulatory risk index. An unweighted mean was selected to preserve interpretability as a within-site diagnostic and to avoid introducing jurisdiction-specific thresholds or weighting schemes that vary across countries, land-use contexts, and risk frameworks. Risk-weighted alternatives are feasible, such as weighting by toxicity or scaling to guideline values, but require context-specific benchmark selection and stakeholder input. The unweighted definition is therefore retained for the present objectives.

Although Mo exhibited a limited dynamic range in this dataset and was therefore not modelled as an individual target (Section 2.8), it was retained within the HMI to preserve the full multi-metal structure of the monitoring panel. Including Mo in the composite index supports consistent within-site screening of relative enrichment across the same set of measured metals, while acknowledging that its contribution to predictive modelling is constrained by low variability.

2.5. Field-Scale HMI Trajectory Typology for Monitoring Interpretation

To support monitoring interpretation, fields were grouped into qualitative trajectory classes using their campaign-wise mean HMI time series. The operational definitions and field assignments are summarized in Table S9. Briefly, fields were categorized as chronic (persistently positive HMI), transient (initially elevated HMI followed by a sustained decline toward near-zero or negative values), emergent (near-zero early values followed by sustained increases in later campaigns), or low and stable (HMI at or below zero for most campaigns). This typology was used to structure interpretation of spatio-temporal enrichment patterns and to link results to monitoring priorities at the field scale.

2.6. GIS Data Handling and Spatial Visualization

Spatial data processing and cartographic outputs were produced using QGIS (version 3.40) and R. Field polygons were used for area-based visualization of metals and HMI, and field centroids were used where point representations were more appropriate. The analytical focus was field-resolved assessment rather than interpolation to continuous surfaces. Accordingly, no quantitative claims are made at resolutions finer than the field units.

2.7. Contextual Comparison with Indicative Agricultural Screening Values

To contextualize the magnitude of observed concentrations, the observed ranges and summary statistics were compared with illustrative screening values commonly used for agricultural soils (Table S3). These values are provided for context only because there is no globally harmonized soil-quality standard for heavy metals in agricultural soils, and thresholds vary by jurisdiction, land use, soil properties, and regulatory framework. Fe and Mn are reported without generic screening thresholds because they are major elements typically interpreted within a pedological and geochemical context.

2.8. Predictive Modelling with XGBoost, Cross-Validation Design, Uncertainty Diagnostics, and Interpretability

2.8.1. Modelling Approach and Targets

XGBoost regression was used to predict individual metal concentrations and HMI from routine soil predictors. The final predictor set used for modelling was restricted to humus (%), pH in H2O, and pH in KCl to reflect variables that are routinely available in agronomic monitoring and are mechanistically linked to metal mobility and retention. Predictors were centred and scaled (mean 0, standard deviation 1) prior to modelling.

Separate models were fitted for Pb, Cu, Zn, Ni, Cr, Fe, Mn, and HMI. Mo was not modelled due to its limited dynamic range in this dataset, which reduces the stability and interpretability of predictive evaluation.

2.8.2. Spatial Block Cross-Validation and Fold Construction

To avoid optimistic performance estimates arising from spatial dependence among fields and repeated measurements across campaigns, model evaluation was performed using field-based spatial block cross-validation with five folds. The field was the blocking unit. All observations from the same field across campaigns were assigned to the same fold so that validation always occurred on withheld fields rather than withheld observations within the same field.

Folds were constructed to be geographically coherent by clustering field centroids into five spatial groups using k-means clustering with . The resulting assignments were visually checked to ensure that folds corresponded to compact spatial groupings and that each fold included multiple campaigns. The fold composition and campaign coverage diagnostics are summarized in Table S8.

2.8.3. Performance Metrics and Fold-Wise Variability

For each fold, models were trained on four folds and evaluated on the withheld fold. Predictive performance was summarized using the coefficient of determination and the root mean square error (RMSE):

where is the observed value, is the prediction, is the mean of observations in the evaluation set, and is the number of validation observations for the fold. For each target, metrics were computed for each fold and summarized as mean and standard deviation across the five spatial folds. Fold-wise performance for HMI is reported in Table S5. Reporting the standard deviation across folds provides a transparent measure of how strongly performance varies by withheld spatial region and therefore quantifies spatial robustness.

Because pH in KCl contained substantial missingness (Table S2), the modelling workflow used complete-case data for the predictors required by the model. This produced an effective modelling sample size of complete-case observations for the modelled targets and evaluation.

2.8.4. Reliability Diagnostics Based on Held-Out Prediction Errors

To characterize predictive reliability without relying on parametric prediction standard errors, held-out errors from spatial cross-validation were used as a conservative uncertainty diagnostic. For each observation, the absolute out-of-fold error was computed as:

These absolute errors were aggregated in two ways:

- Field-level reliability diagnostic: Absolute errors were aggregated by field to compute a mean absolute residual for each field, which provides a field-resolved indicator of where predictions are typically more or less reliable under strict spatial validation. Field-level diagnostics for HMI are summarized in Table S6.

- Campaign-level reliability diagnostic: Absolute errors were aggregated by campaign to evaluate whether predictive errors exhibited systematic temporal structure. Campaign-level summaries for HMI are reported in Table S7.

Together, these diagnostics provide transparent evidence on where, and when, the reduced predictor set yields more reliable predictions, while remaining grounded in held-out performance under spatial blocking.

2.8.5. Benchmark Comparison Using Random k-Fold Cross-Validation

To quantify the degree to which spatial dependence inflates apparent predictive performance when ignored, the same modelling workflow was also evaluated using random 5-fold cross-validation. In this benchmark, observations were randomly assigned to folds without spatial blocking, and performance metrics were computed and summarized as mean and standard deviation across folds, analogous to the spatial evaluation. Results are reported in Table S4. This comparison provides a direct measure of the optimistic bias introduced when spatial structure is not controlled.

2.8.6. Model Interpretability Using SHAP Values

To interpret the fitted HMI model, SHAP values were computed using the tree-based SHAP algorithm. For an observation with predictor vector , the model prediction can be expressed as:

where is the baseline prediction and is the contribution of predictor to the prediction. Global feature importance was quantified using the mean absolute SHAP value across all observations. Mean absolute SHAP values for the predictors in the HMI model are reported in Table S1, enabling a transparent ranking of predictor influence within the constrained predictor set.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Overview and Temporal Dynamics at the Site Scale

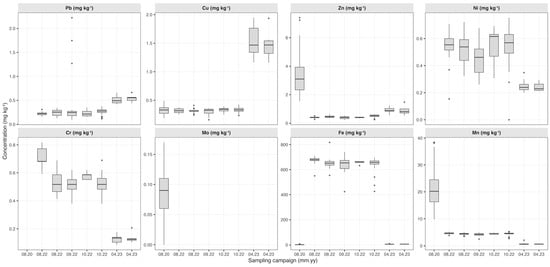

Campaign-wise distributions of heavy metal concentrations are shown in Figure 3. Across all campaigns, absolute concentrations of Pb, Cu, Zn, Ni, Cr, Mo, Fe, and Mn are low in the context of commonly reported background ranges for agricultural topsoils. At the same time, the dataset exhibits pronounced heterogeneity across campaigns and among fields within campaigns. This combination of generally low concentrations and substantial relative variability indicates that enrichment signals, where present, are spatially localized and temporally non-uniform rather than representing a single, site-wide contamination episode.

Figure 3.

Campaign-level distributions of heavy metal concentrations in topsoil (Pb, Cu, Zn, Ni, Cr, Mo, Fe, Mn). Boxplots summarize the intra-campaign variability across all fields; x-axis labels denote sampling campaigns (mm.yy).

Lead (Pb) concentrations are typically between 0.10 and 0.40 mg kg−1, with occasional higher values up to about 2 mg kg−1. Median Pb values vary moderately across campaigns, consistent with gradual and spatially heterogeneous accumulation rather than a single short-lived pulse. Copper (Cu) is generally within 0.20 to 0.80 mg kg−1, with a subset of samples reaching about 2 mg kg−1. Zinc (Zn) shows the broadest dispersion among the trace metals, with medians typically around 2 to 4 mg kg−1 and maxima approaching 7 mg kg−1 in some campaigns, whereas other campaigns display lower and more homogeneous Zn distributions. Nickel (Ni) and chromium (Cr) have narrower interquartile ranges centred around 0.4 to 0.6 mg kg−1, but still exhibit campaign-to-campaign shifts in central tendency.

Molybdenum (Mo) remains very low throughout the monitoring period, typically 0.03 to 0.12 mg kg−1, with limited temporal variation. Among the major elements, Fe is consistently high, in the hundreds of mg kg−1, reflecting its role as a principal soil constituent. Mn shows moderate variability, with most samples around 10 to 25 mg kg−1 and occasional higher values.

Descriptive statistics aggregated across fields and campaigns are summarized in Table 1. Sample sizes are consistent across metals in this dataset (n = 241). Coefficients of variation are highest for Pb and Cu and remain substantial for Zn and Mn, confirming pronounced heterogeneity within this intensively managed site despite its limited spatial extent.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for heavy metal concentrations (mg kg−1) in topsoil across all fields and campaigns (n ≈ 241 samples).

3.2. Field-Scale Variability and Identification of Hot-Spot Fields

Field-scale variability is depicted in Figure 4, which shows field-wise boxplots for each metal across the 34 fields, ordered by median Pb concentration to provide an intuitive enrichment ranking. Even within this compact study area, both median concentrations and within-field spreads differ substantially among fields. This indicates strong spatial structuring of heavy metal distributions at the operational field scale.

Figure 4.

Field-scale variability of heavy metals. Vertical boxplots show distributions for each field (ordered by median Pb); panels correspond to individual metals.

Several fields show consistently elevated Pb, Zn, and Mn, often accompanied by broader interquartile ranges and higher upper tails than the site median. In contrast, other fields maintain uniformly low concentrations with narrow distributions, consistent with limited inputs and or more conservative retention conditions. For Cu and Zn, some fields combine relatively high medians with long upper tails, suggesting localized hot spots superimposed on an elevated field-level background. Ni and Cr are comparatively more homogeneous but still show fields that are systematically enriched relative to others.

Overall, these field-resolved patterns support treating the field as the fundamental spatial monitoring unit, rather than assuming that Site N behaves as a single homogeneous entity.

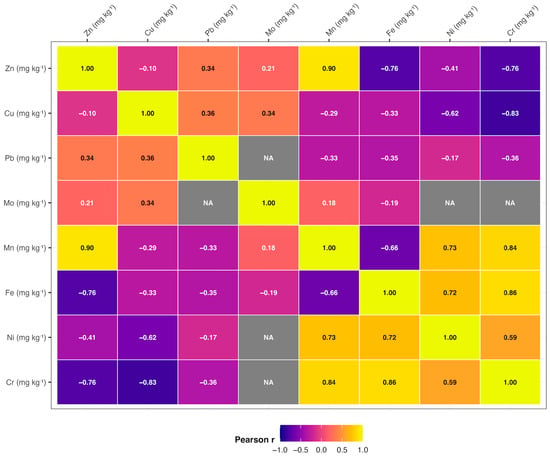

3.3. Inter-Metal Correlations

The Pearson correlation matrix (Figure 5) summarizes co-occurrence patterns among metals. Most pairwise correlations are weak to moderate, with absolute values generally not exceeding about 0.5. This indicates that the eight metals do not behave as a single tightly coupled assemblage, but instead form partially overlapping groups.

Figure 5.

Pairwise Pearson correlation matrix of heavy metal concentrations. Colours denote correlation coefficients from −1 to +1; cells are annotated with r values. Rows and columns are ordered using hierarchical clustering to highlight groups of co-varying metals.

Zn, Ni, and Mn show moderate positive correlations, consistent with shared associations with fine fractions, redox-sensitive Fe and Mn oxide phases, and management inputs that may introduce multiple elements simultaneously. Pb is moderately correlated with Zn and Ni, suggesting that mixed agrochemical inputs and or shared retention mechanisms may contribute to co-enrichment in a subset of fields. Fe exhibits weak correlations with the trace metals, implying that the bulk Fe pool is governed primarily by parent material and pedogenesis rather than recent anthropogenic inputs. Mo is weakly correlated with most metals, consistent with its distinct geochemical behaviour as a pH-sensitive oxyanion influenced by organic matter and oxide surfaces. Cr shows low to moderate correlations with Ni and Zn, reflecting partial co-location in specific fields rather than uniform site-wide coupling.

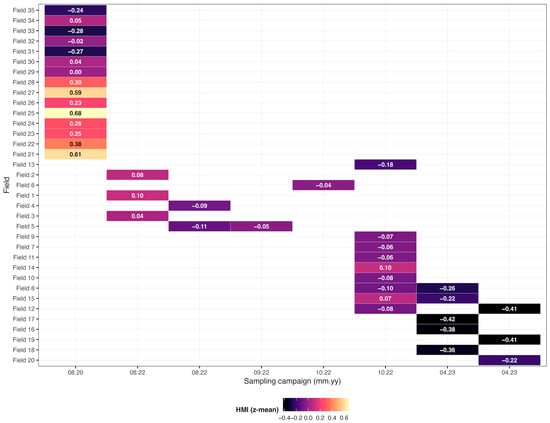

3.4. Composite Heavy Metal Enrichment Index

To synthesize multi-metal patterns, we computed the HMI as the arithmetic mean of z-standardized concentrations across the eight metals. Figure 6 shows the resulting field-by-campaign tile plot. HMI values are dimensionless, with 0 representing the site-wide mean across samples.

Figure 6.

Spatio-temporal distribution of the HMI. Tiles represent mean HMI per field and campaign; warmer colours indicate higher enrichment relative to the site mean.

The HMI visualization reveals distinct spatio-temporal trajectories. A subset of fields exhibits persistently positive HMI across multiple campaigns, indicating chronically elevated multi-metal enrichment relative to the site mean. Another subset shows elevated HMI in earlier campaigns followed by a gradual decline toward near-zero or slightly negative values, consistent with attenuation or dilution of earlier enrichment pulses. Conversely, some fields transition from near-zero HMI in early campaigns to positive HMI in later campaigns, indicating emergent hot spots.

On this basis, fields can be operationally grouped into three screening classes: chronically enriched fields with persistently elevated HMI, transiently enriched fields with declining HMI trajectories, and emergent hot spots with increasing HMI in later campaigns. This typology provides a practical interpretive layer for prioritizing follow-up sampling and targeted investigation using the field as the management unit. Field assignments and operational definitions are summarized in Table S9.

3.5. XGBoost Prediction of Heavy Metals and HMI from Routine Soil Properties

Descriptive analyses and index construction used the full dataset (n = 241 field–campaign observations). Predictive modelling and SHAP interpretation were conducted on a complete-case subset (n = 152) because pH (KCl) was missing for 89 observations (36.9%; Table S2).

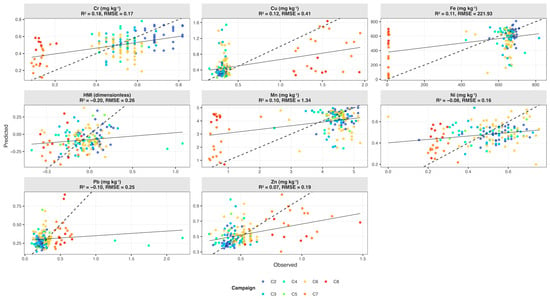

We evaluated the ability of routine soil properties to predict heavy metal concentrations and HMI using XGBoost with field-based spatial block cross-validation. Observed versus predicted values are shown in Figure 7. Performance metrics are reported in Table 2 as the mean and standard deviation across the five spatial folds. Because Mo concentrations show very limited dynamic range, Mo was not modelled.

Figure 7.

Observed versus predicted values from XGBoost models with field-based spatial block cross-validation. Points denote field–campaign combinations, coloured by sampling campaign; the dashed line is the 1:1 line, and the solid line is the fitted regression. Panels show individual metals and HMI, with corresponding cross-validated R2 and RMSE values.

Table 2.

Performance of XGBoost models with field-based spatial block cross-validation.

Across targets, predictive skill under spatial blocking was modest but non-zero for several responses. Under spatial cross-validation, Cr and Cu exhibited the highest performance (Cr: R2 = 0.21 ± 0.11, RMSE = 0.17 ± 0.06; Cu: R2 = 0.19 ± 0.14, RMSE = 0.41 ± 0.09). The HMI model also showed limited but consistent skill (R2 = 0.20 ± 0.12, RMSE = 0.26 ± 0.06), indicating that humus and soil acidity capture part of the multi-metal enrichment signal. Zn and Mn exhibited lower average skill (Zn: R2 = 0.09 ± 0.16, RMSE = 0.19 ± 0.08; Mn: R2 = 0.10 ± 0.18, RMSE = 1.34 ± 0.19). Fe showed a low mean R2 with relatively large fold-to-fold variability (R2 = 0.11 ± 0.15, RMSE = 221.93 ± 35.0), suggesting that transferability varies substantially depending on which spatial field block is withheld.

In contrast, Ni and Pb yielded negative mean R2 under spatial blocking (Ni: R2 = −0.08 ± 0.17, RMSE = 0.23 ± 0.04; Pb: R2 = −0.12 ± 0.18, RMSE = 0.25 ± 0.05). These results indicate that, for Ni and Pb, the selected routine predictors do not consistently outperform a mean-only baseline when evaluated on withheld spatial blocks.

Reporting the standard deviation across spatial folds provides a direct and conservative measure of robustness and spatial transferability. For several targets, the standard deviation of R2 is comparable to or larger than the mean value, indicating that performance depends strongly on which spatial block is withheld. This heterogeneity is consistent with the small number of independent spatial units, the deliberately restricted predictor set, and strict spatial hold-out evaluation designed to test generalization to unseen fields. Accordingly, these models are most appropriately interpreted as screening-level predictors that quantify consistent associations with routine soil properties rather than fully operational predictors of all field-to-field variability.

To quantify the effect of spatial dependence, we also evaluated the same modelling workflow under random 5-fold cross-validation. As expected, random cross-validation produced higher apparent performance than spatial blocking across targets, including HMI (Table S4). This comparison supports interpreting the spatial block cross-validation metrics as a conservative assessment of predictive skill under realistic spatial transfer conditions.

3.6. Spatial and Temporal Reliability Diagnostics from Held-Out Residuals

To provide a spatially explicit diagnostic of predictive reliability without relying on parametric prediction standard errors, we summarized the absolute prediction errors derived from held-out predictions under spatial block cross-validation. Field-level error distributions for HMI are summarized in Table S6. Mean absolute residuals vary among fields, indicating that predictive reliability is not spatially uniform. Fields with higher mean absolute residuals represent locations where predictions based on humus and pH explain less of the observed HMI variability, suggesting that additional drivers such as management history, irrigation inputs, localized sources, or unmeasured soil properties may be more influential in those areas.

To assess temporal structure in errors, absolute residuals were also aggregated by sampling campaign (Table S7). Campaign-level mean absolute residuals are broadly comparable across the monitoring period, indicating no strong temporal degradation in predictive performance. Nonetheless, modest differences among campaigns suggest that certain periods may contain patterns that are less well captured by the restricted predictor set, consistent with the interpretation of emergent enrichment dynamics in a subset of fields.

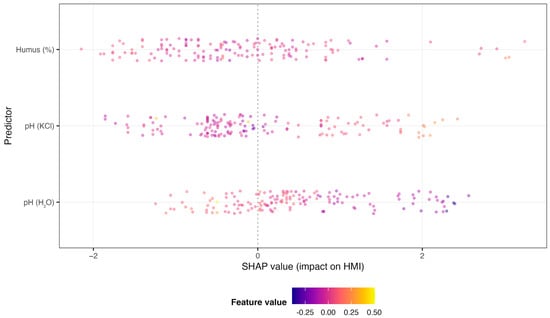

3.7. Model Interpretability Based on SHAP Values

To identify the routine soil properties most consistently associated with predicted HMI, we computed SHAP values for the fitted HMI XGBoost model. Global feature importance is summarized in Table S1 using mean absolute SHAP values and is visualized in the SHAP summary plot (Figure 8). Humus content has the strongest overall contribution to predicted HMI, followed by pH in KCl and pH in H2O. This ranking indicates that organic matter content and soil acidity dominate the model signal within the constrained predictor set.

Figure 8.

SHAP summary (beeswarm) plot for the HMI XGBoost model. Each point represents a field–campaign combination; the x-axis shows the SHAP value (impact on the predicted HMI), the y-axis lists the predictors, and point colour denotes the scaled feature value.

The SHAP summary plot (Figure 8) clarifies effect directionality. Lower pH in H2O values, corresponding to more acidic conditions, are generally associated with positive SHAP contributions and therefore higher predicted HMI. This pattern is consistent with increased solubility and mobility of many cationic metals under acidic conditions. For pH in KCl, SHAP contributions are more non-linear, consistent with complex interactions involving exchangeable acidity and surface charge behaviour. Higher humus contents correspond to positive SHAP values, indicating higher predicted HMI, which is consistent with stronger sorption capacity and the potential accumulation of historical inputs in organic-rich topsoil.

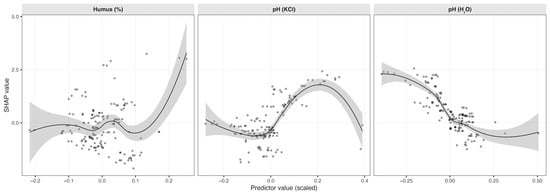

These response patterns are further illustrated in SHAP dependence plots (Figure 9), which show SHAP values versus scaled predictor values with smooth trends. Together, these interpretability outputs link the statistical behaviour of the model to established geochemical controls on metal retention and mobility.

Figure 9.

SHAP dependence plots for the HMI XGBoost model. Points show SHAP values versus scaled predictor values for pH (H2O), pH (KCl), and humus (%); smooth curves (LOESS) summaries non-linear response patterns.

3.8. Missing Data, Modelling Sample Size, and Context Relative to Screening Values

Missingness in the predictors used for the HMI model is summarized in Table S2. Humus (%) and pH in H2O are complete, whereas pH in KCl contains substantial missingness (36.9%). Therefore, model fitting and evaluation were conducted on complete-case subsets for the selected predictor set, resulting in an effective modelling sample of n = 152 observations for the targets reported in Table 2. This conservative strategy avoids artefacts associated with large-scale imputation under substantial missingness and ensures that cross-validation results are grounded in observed predictor information.

For context, Table S3 compares observed concentration ranges with illustrative screening values commonly used for agricultural soil assessment. All observed concentrations at Site N are well below these illustrative thresholds, and the dataset therefore indicates low absolute levels in a regulatory screening context at present. At the same time, field-scale variability and spatio-temporal changes in HMI indicate that relative enrichment patterns and localized hot spots can be resolved at the field scale, supporting the value of a monitoring framework that focuses on spatial targeting and trajectory-based interpretation rather than exceedance-based classification alone.

4. Discussion

This study supports field-scale interpretation of heavy metal dynamics in an intensively managed cereal system located within an industrial influence zone. The main implication is that the observed enrichment structure is most plausibly produced by interacting drivers operating across scales, including lithogenic and pedogenic background, diffuse deposition, and management-mediated inputs and redistribution. Similar mixed control is widely reported for agricultural soils where industrial proximity and evolving farming practices coexist [4,14,18].

Divergent temporal behaviour among metals is more consistent with a superposition of processes than with a single contamination episode. In comparable settings, multi-year variation often reflects changes in amendment composition, liming and acidifying practices, irrigation-related transport, and redistribution by tillage [3,20,30]. Apparent declines in relative enrichment can indicate reduced inputs or dilution, but they can also reflect mixing and convergence toward a local baseline rather than true removal from the system. Conversely, later increases can reflect new inputs or geochemical shifts that favour retention in the sampled topsoil. Spatio-temporal zoning studies in high-background regions likewise emphasize separating persistent background structure from evolving superimposed signals [3].

Field-to-field contrasts are often more actionable than enterprise means because localized practices and micro-environments can concentrate enrichment into specific operational units. GIS-based contamination assessments repeatedly show that hot spots are commonly associated with differential amendment history, irrigation inflows, storage and traffic zones, and local buffering capacity [5,6,25]. Treating the field as the primary unit therefore improves the defensibility of targeted follow-up sampling and supports practical prioritization under limited monitoring resources [6,12].

The HMI used here is designed for within-site screening of relative multi-metal enrichment. This is conceptually distinct from risk, which depends on toxicity, exposure pathways, crop uptake, and jurisdiction-specific thresholds. Composite indices are widely used for spatial screening, but interpretation depends on whether the goal is prioritization or compliance [12,18]. An unweighted index supports transparent within-enterprise comparison and avoids embedding a weighting scheme that may not transfer across jurisdictions. Risk-weighted extensions remain feasible, but they should be implemented only when the regulatory and stakeholder context is explicitly defined [12].

From a modelling standpoint, the most important interpretive point is that spatially constrained validation tests transferability to withheld field blocks, which is the operationally relevant standard for monitoring applications. Random cross-validation can overstate expected performance because nearby units share structure [11,33]. Under this lens, modest but stable skill using only humus and soil acidity (pH in H2O and pH in KCl) indicates that part of the enrichment signal is transferable and captured by interpretable soil controls. Limited or unstable skill for some targets suggests that important drivers are missing, such as detailed management records, irrigation water chemistry, microtopography, and proximity to localized sources. This aligns with digital soil mapping evidence that stronger performance typically requires richer geospatial covariates and explicit handling of spatial dependence [1,11].

Explainable machine learning is increasingly used to diagnose spatial effects and support defensible interpretation of heavy metal models [32]. In this study, SHAP results indicate that humus content and soil acidity dominate HMI prediction, which is mechanistically plausible because organic matter and pH regulate sorption, complexation, and mobility for many cationic metals. Interpretable attribution also clarifies that routine soil variables can act both as direct geochemical controls and as proxies for cumulative management intensity, which supports use of the model for screening and prioritization rather than causal attribution [32].

The trajectory-based typology provides actionable guidance without relying on exceedance alone. GIS-oriented screening studies similarly emphasize hot spot identification and stratified follow-up [6,12]. In practical terms, chronically enriched fields merit targeted source checking and verification sampling; transient fields support confirmation that attenuation persists under current practices; emergent hot spots should trigger rapid review of recent inputs and prioritization in the next sampling campaign [3,18,25]. In the specific regional context, these monitoring and decision workflows can be integrated with broader farm digitalization and remote-sensing based management initiatives that are already being developed for cereal systems in East Kazakhstan [37,38].

The results are enterprise-specific, so transfer should be framed as methodological rather than as universal thresholds. Improving completeness of routine predictors and adding operational covariates is the most direct path to stronger spatial transfer, such as amendment categories, liming frequency, and distance to infrastructure or irrigation networks, consistent with multi-covariate digital soil mapping approaches [1,7,11]. Remote sensing and hyperspectral methods are also a realistic pathway to expand covariate coverage where field data are sparse, provided that source and migration pathways are considered explicitly [2,34,36,38]. Finally, the expansion of source apportionment research underscores the need for cautious source claims when direct tracers and detailed management records are unavailable [22].

Overall, the study provides a field-based, explainable screening framework that integrates multi-campaign monitoring, an enrichment-focused index, and spatially conservative validation. This supports transparent prioritization of follow-up sampling and management attention in data-limited agricultural settings under potential industrial influence [6,11,12,32].

5. Conclusions

This study presents a field-scale assessment of heavy metals in agricultural topsoil at a large enterprise in eastern Kazakhstan (Site N) using repeated sampling, GIS-based spatial analysis, and explainable machine learning. Concentrations of Pb, Cu, Zn, Ni, Cr, Mo, Fe, and Mn were measured in composite topsoil samples collected across eight campaigns between 2020 and 2023 from 34 operational fields. The multi-campaign design demonstrates that heavy metal status in intensively managed soils is dynamic. Several elements show meaningful temporal shifts, indicating that single-time-point surveys can miss both emerging enrichment and attenuation trends.

Field-resolved analyses highlight strong spatial heterogeneity within the enterprise. A subset of fields consistently contributes disproportionally to the multi-metal enrichment signal, while many fields remain near the enterprise baseline. The HMI, defined as an unweighted mean of z-standardized metal concentrations, provides a transparent screening indicator of relative multi-metal enrichment within the same farm. Using HMI trajectories, fields can be interpreted in operational classes, including chronically enriched, transiently enriched, and emergent hotspots, which supports targeted follow-up sampling and management review at the scale where decisions are implemented.

Model-based prediction from routine soil properties shows that part of the enrichment structure is transferable across space, but uncertainty is substantial. XGBoost models using humus, pH (H2O), and pH (KCl) and evaluated with field-based spatial block cross-validation achieved modest predictive skill for several targets, including HMI, while other metals were poorly predicted under strict spatial hold-out. Reporting mean and standard deviation of performance across spatial folds (Table 2) improves transparency and directly addresses model robustness. Comparison with random cross-validation (Table S4) confirms that ignoring spatial structure inflates apparent skill and therefore should not be used to judge operational performance.

Explainability analyses strengthen the mechanistic credibility of the modelling results. SHAP values indicate that humus and soil acidity dominate HMI prediction (Table S1), consistent with established roles of organic matter and pH in sorption, complexation, and mobility of many cationic metals. The framework therefore provides interpretable, screening-level decision support rather than a substitute for direct measurement in compliance contexts.

All observed concentrations remain below illustrative screening values compiled for agricultural soils (Table S3). Accordingly, the factors with the greatest current management relevance at Site N are relative enrichment and its spatial concentration in specific fields, not exceedance of regulatory limits. The study provides a practical monitoring logic for similar data-limited agricultural systems: use repeated sampling to resolve trajectories, use field-scale mapping to locate persistent or emerging hotspots, and use spatially conservative, explainable models to prioritize where additional sampling and investigation are most likely to be informative.

Future work should test transferability across additional farms and soil types, improve completeness of routine predictors, and incorporate operational covariates that plausibly drive field-scale differences, such as amendment categories, liming history, irrigation water chemistry, and proximity to infrastructure. Remote sensing-derived indicators may further expand covariate coverage and support scalable screening, but should be integrated with careful attention to local source and transport pathways.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010431/s1, Table S1: Mean absolute SHAP values (|φ_j|) for predictors in the HMI XGBoost model; Table S2: Proportion of missing values for predictor variables used in the HMI model (before imputation; n = 241 field–campaign combinations); Table S3: Observed heavy metal concentrations in topsoil at Site N and comparison with indicative screening values for agricultural soils; Table S4: Random 5-fold cross-validation performance; Table S5: Fold-wise performance for HMI under spatial block cross-validation; Table S6: Field-level predictive reliability diagnostic for HMI (mean absolute residual from OOF predictions); Table S7: Campaign-level aggregation of absolute prediction errors for HMI; Table S8: Spatial-fold composition diagnostics; Table S9: HMI trajectory typology for field-scale monitoring interpretation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and N.B.; methodology, M.S. and N.B.; software, N.B.; validation, M.S. and N.B.; formal analysis, M.S. and N.B.; investigation, N.B.; resources, M.S.; data curation, N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and N.B.; visualization, N.B.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP26100131 «Studies of soil quality in areas of anthropogenic impact of non-ferrous metallurgy enterprises»).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANFIS | Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DSM | Digital Soil Mapping |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| HMI | Heavy Metal Enrichment Index |

| HMs | Heavy Metals |

| PPI | Probabilistic Pollution Index |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Liu, Q.; Du, B.; He, L.; Zeng, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, R.; Shi, T. Digital Soil Mapping of Heavy Metals Using Multiple Geospatial Data: Feature Identification and Deep Neural Network. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Niu, R.; Wu, X.; Song, Y. Estimating of Heavy Metal Concentration in Agricultural Soils from Hyperspectral Satellite Sensor Imagery: Considering the Sources and Migration Pathways of Pollutants. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 158, 111416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, X. Spatial Zoning Based on Spatial and Temporal Soil Heavy Metal Changes in Geological High Background Areas. Land 2025, 14, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Wu, C.; He, Z.; Japenga, J.; Deng, M.; Yang, X. An Integrated Approach to Assess Heavy Metal Source Apportionment in Peri-Urban Agricultural Soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 299, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gök, G.; Tulun, Ş.; Çelebi, H. Mapping of Heavy Metal Pollution Density and Source Distribution of Campus Soil Using Geographical Information System. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behairy, R.E.; Baroudy, A.E.; Ibrahim, M.; Mohamed, E.; Rebouh, N.; Shokr, M. Combination of GIS and Multivariate Analysis to Assess the Soil Heavy Metal Contamination in Some Arid Zones. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Hu, W.; Li, M.; Ding, L. Spatial Distribution and Driving Force Analysis of Soil Heavy Metals in the Water Source Area of the Middle Route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoni, H.; Hong, L.; Danfeng, S.; Liandi, Z.; Baoguo, L. Multi-Scale Spatial Structure of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils in Beijing. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 164, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xue, J.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Zha, X.; Fang, G. The Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Heavy Metals in Soil in Xinjiang, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.; Kabir, M.H.; Alam, M.A.; Mashuk, H.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Alam, M.S.; Brodie, G.; Islam, S.M.M.; Gaihre, Y.K.; Rahman, G.K.M.M. Geospatial Visualization and Ecological Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Rice Soil of a Newly Developed Industrial Zone in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Fathizad, H.; Ardakani, M.A.H.; Sodaiezadeh, H.; Kerry, R.; Heung, B.; Scholten, T. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Heavy Metals in Arid Soils at the Catchment Scale Using Digital Soil Assessment and a Random Forest Model. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparisi-Navarro, S.; Moncho-Santonja, M.; Defez, B.; Candeias, C.; Rocha, F.; Peris-Fajarnés, G. Assessing Heavy Metal Contamination in Agricultural Soils: A New GIS-Based Probabilistic Pollution Index (PPI)—Case Study: Guarda Region, Portugal. Ann. GIS 2025, 31, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Shi, Z.; Yu, L.; Fan, H.; Wan, F. Soil Quality and Heavy Metal Source Analyses for Characteristic Agricultural Products in Luzuo Town, China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.; Scheifler, R.; Benslama, M.; Crini, N.; Lucot, E.; Brahmia, Z.; Benyacoub, S.; Giraudoux, P. Spatial Distribution of Heavy Metal Concentrations in Urban, Suburban and Agricultural Soils in a Mediterranean City of Algeria. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 2294–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krami, L.K.; Amiri, F.; Sefiyanian, A.; Shariff, A.R.B.M.; Tabatabaie, T.; Pradhan, B. Spatial Patterns of Heavy Metals in Soil under Different Geological Structures and Land Uses for Assessing Metal Enrichments. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 9871–9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakoloukas, V.; Koutopoulis, G.; Papadimou, S.G.; Spiliotopoulos, M.-E.; Golia, E.E. Predicting Heavy Metal and Nutrient Availability in Agricultural Soils under Climatic Variability Using Regression and Mixed-Effects Models. Land 2025, 14, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Wang, D.; Qian, Y.; Yu, R.; Ding, A.; Huang, Y. Application of Integrated Land Use Regression and Geographic Information Systems for Modeling the Spatial Distribution of Chromium in Agricultural Topsoil. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Luo, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B. Geospatial Analysis, Source Apportionment, and Ecological–Health Risks Assessment of Topsoil Heavy Metal(Loid)s in a Typical Agricultural Area. Agriculture 2025, 15, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.S.; Jalhoum, M.E.M.; Belal, A.A.; Hendawy, E.; Azab, Y.F.A.; Kucher, D.E.; Shokr, M.S.; Behairy, R.A.E.; Arwash, H.M.E. A Novel Approach for Predicting Heavy Metal Contamination Based on Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System and GIS in an Arid Ecosystem. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ma, K. Spatial and Temporal Distribution and Source Analysis of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils of Ningxia, Northwest of China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sorogy, A.S.; Al-Kahtany, K.; Alharbi, T.; Hawas, R.A.; Rikan, N. Geographic Information System and Multivariate Analysis Approach for Mapping Soil Contamination and Environmental Risk Assessment in Arid Regions. Land 2025, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; He, Z.; Deng, C.; Liu, A.; Feng, Y.; Li, L.; Ji, G.; Xie, M.; Liu, X. How Has the Source Apportionment of Heavy Metals in Soil and Water Evolved over the Past 20 Years? A Bibliometric Perspective. Water 2024, 16, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhou, X.; Ding, M.; Wang, B.; Liao, L. Spatial Heterogeneity of Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soil Using Hyperspectral Inversion Models: A Case Study of Dongting Lake Region, South-Central China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.S.; Jalhoum, M.E.M.; Hendawy, E.; El-Adly, A.M.; Nawar, S.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Saleh, A.; Shokr, M.S. Geospatial Evaluation and Bio-Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils in Arid Zones. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1381409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokr, M.S.; Abdellatif, M.A.; El Behairy, R.A.; Abdelhameed, H.H.; El Baroudy, A.A.; Mohamed, E.S.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Ding, Z.; Abuzaid, A.S. Assessment of Potential Heavy Metal Contamination Hazards Based on GIS and Multivariate Analysis in Some Mediterranean Zones. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhakypbek, Y.; Rysbekov, K.; Lozynskyi, V.; Mikhalovsky, S.; Salmurzauly, R.; Begimzhanova, Y.; Kezembayeva, G.; Yelikbayev, B.; Sankabayeva, A. Geospatial and Correlation Analysis of Heavy Metal Distribution on the Territory of Integrated Steel and Mining Company Qarmet JSC. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahal, A.Y.; El-Sorogy, A.S.; De Larriva, J.E.M.; Shokr, M.S. Mapping Soil Contamination in Arid Regions: A GIS and Multivariate Analysis Approach. Minerals 2025, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abowaly, M.E.; Ali, R.A.; Moghanm, F.S.; Gharib, M.S.; Moustapha, M.E.; Elbagory, M.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Elmahdy, S.M. Assessment of Soil Degradation and Hazards of Some Heavy Metals, Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques in the Northern Part of the Nile Delta, Egypt. Agriculture 2022, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, A.; Zaidi, A.; Ameen, F.; Ahmed, B.; AlKahtani, M.D.F.; Khan, M.S. Heavy Metal Induced Stress on Wheat: Phytotoxicity and Microbiological Management. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 38379–38403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; Shi, R.; Ma, J.; Li, H.; Ma, T.; Ma, J.; Liang, X.; Ma, C. Spatial Distribution and Pollution Source Analysis of Heavy Metals in Cultivated Soil in Ningxia. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Xu, Z.; Ma, H.; Liu, X.; Guo, F.; Xu, Z.; Ma, H.; Liu, X. Estimating Soil Arsenic Contamination by Integrating Hyperspectral and Geochemical Data with PCA and Optimizing Inversion Models. Sensors 2025, 25, 6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, Y. Revealing the Synergistic Spatial Effects in Soil Heavy Metal Pollution with Explainable Machine Learning Models. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 482, 136578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, M.; Huang, X.; Song, X.; Cai, B.; Tang, R.; Sun, J.; Han, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Improving Prediction of Soil Heavy Metal(Loid) Concentration by Developing a Combined Co-Kriging and Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression (GTWR) Model. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Guo, B.; Feng, Q. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing for Soil Heavy Metal Inversion: Insights and Applications. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2520474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, S.; Hu, H. Halophyte-Mediated Metal Immobilization and Divergent Enrichment in Arid Degraded Soils: Mechanisms and Remediation Framework for the Tarim Basin, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Shao, X.; Wu, H.; Jiang, R.; Wu, M. Heavy Metal Concentration Estimation for Different Farmland Soils Based on Projection Pursuit and LightGBM with Hyperspectral Images. Sensors 2024, 24, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadenova, M.A.; Beisekenov, N.A.; Varbanov, P.S.; Kulenova, N.A.; Abitaev, F.; Kamenev, Y. Digitalization of Crop Production for Transition to Climate-Optimized Agriculture Using Spring Wheat in East Kazakhstan as an Example. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 96, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadenova, M.A.; Beisekenov, N.A.; Ualiyev, Y.T.; Kulenova, N.A.; Varbanov, P.S. Modelling of Forecasting Crop Yields Based on Earth Remote Sensing Data and Remote Sensing Methods. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 94, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.