Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using a Stacking Model Based on Multidimensional Feature Collaboration and Pseudo-Labeling Techniques

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A Stacking model is employed to integrate Random Forest (RF), TabNet, LeNet, and ViT methods, fully leveraging their complementary strengths in shallow rule extraction and deep semantic modeling.

- (2)

- To address the effects of limited feature representation on model performance, we propose a multidimensional feature collaborative modeling strategy. This strategy employs a Stacking model to integrate global statistical attributes extracted from one-dimensional vectors with multi-scale spatial topological features derived from three-dimensional vectors. Through this cross-dimensional feature collaboration, the model achieves unified representation learning, thereby enhancing its ability to characterize relevant environmental factors.

- (3)

- To address the issue of sample scarcity, we introduce the pseudo-labeling technique from semi-supervised learning. A dual-validation mechanism, combining self-training and multi-network collaboration strategies, is employed to generate high-confidence pseudo-labels. This method effectively exploits the latent feature information of unlabeled samples for auxiliary training, thereby improving model stability and generalization capability.

- (4)

- We validated the effectiveness of the proposed model using two representative study areas, Zigui to Badong in the Yangtze River Basin and Ya’an City in Sichuan Province, where it consistently outperformed traditional EL models across all accuracy metrics.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. The Zigui–Badong Section of the Yangtze River Basin

2.1.2. Ya’an City in Sichuan Province

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.2.1. Positive Sample

2.2.2. Negative Sample

2.3. Landslide Conditioning Factors

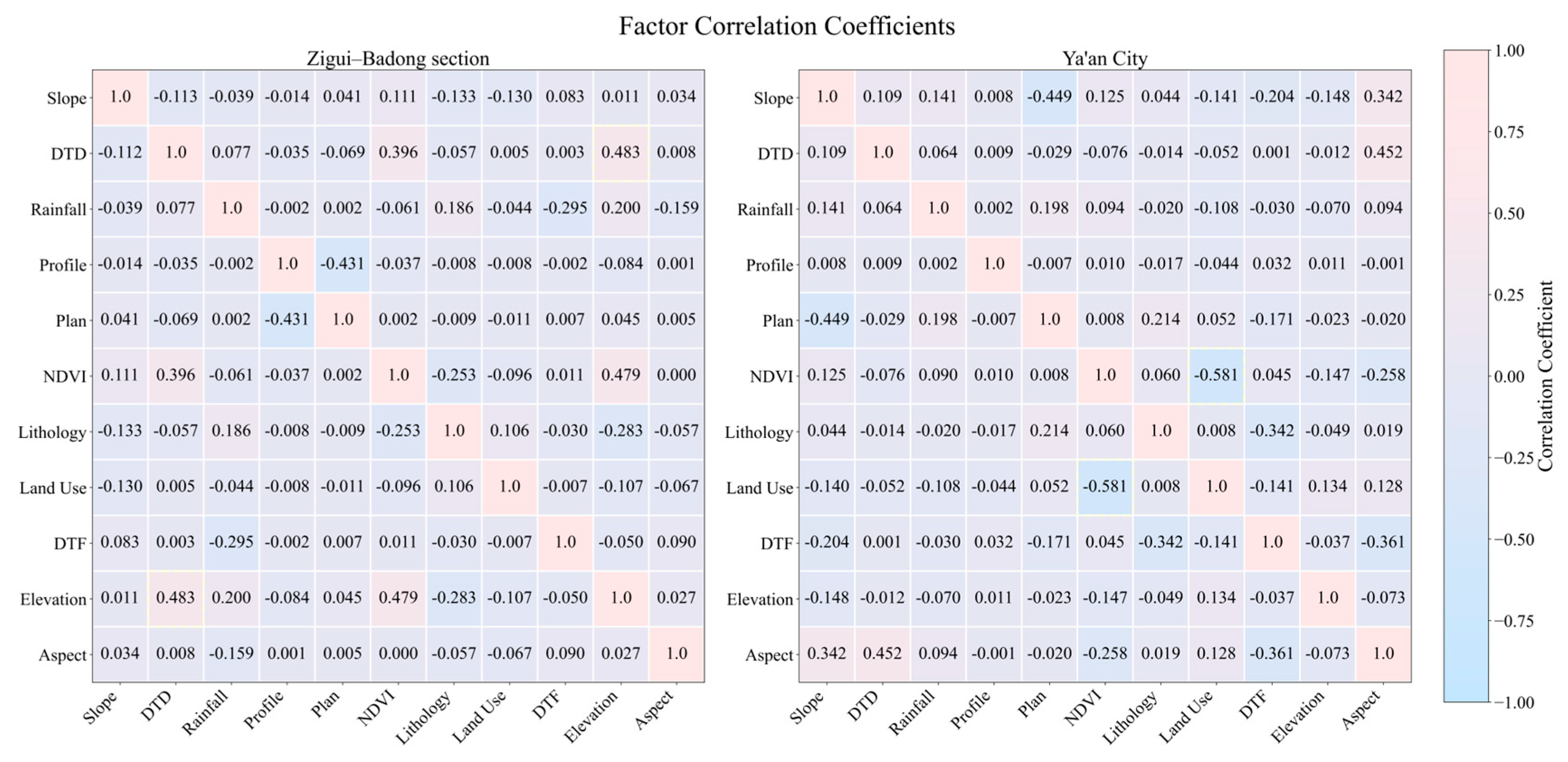

2.4. LCFs Analysis and Selection

2.4.1. Multicollinearity Analysis

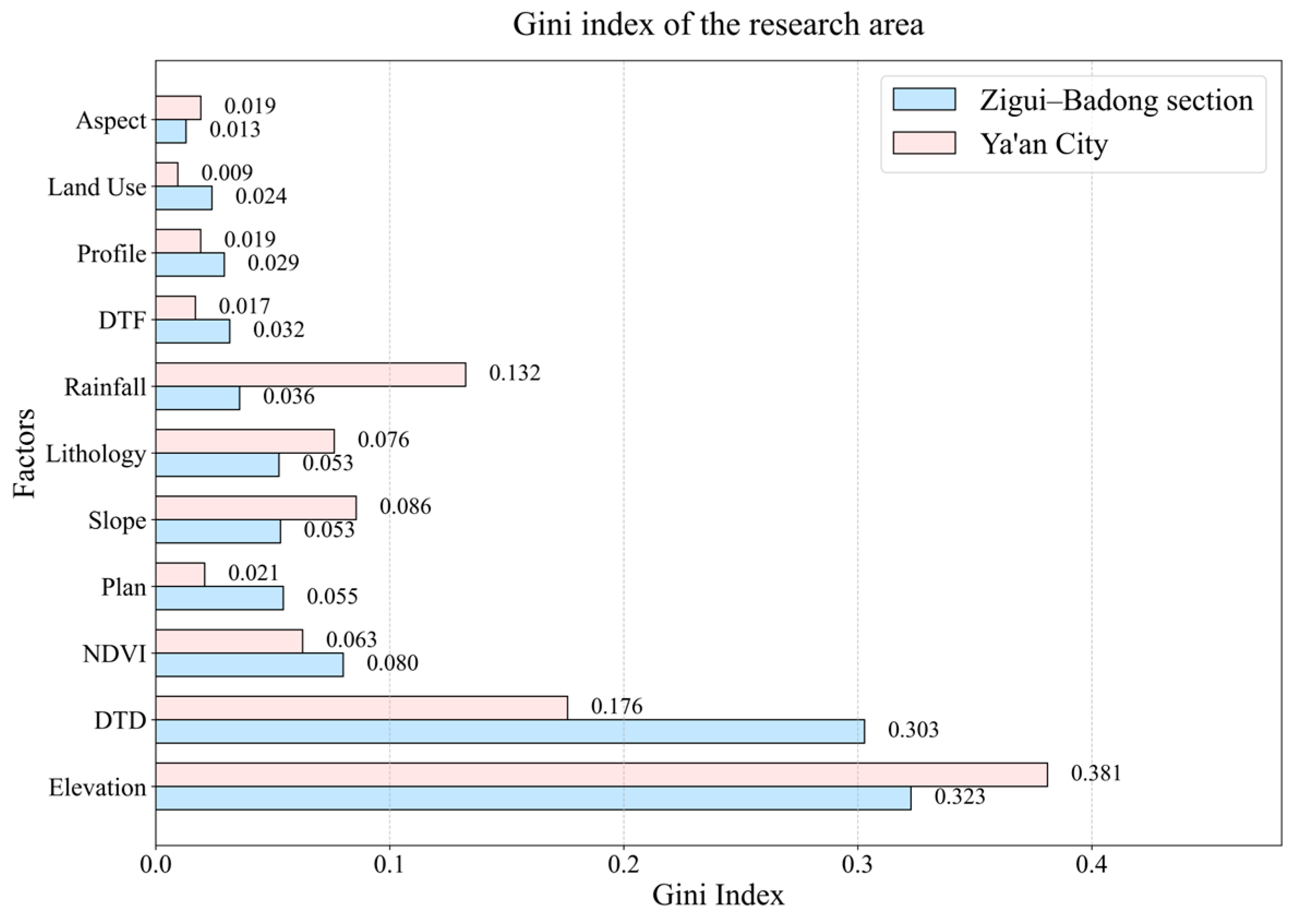

2.4.2. Importance Evaluation

3. Methods

3.1. Multidimensional Vector Production

3.2. Single Classifiers

3.2.1. RF

3.2.2. TabNet

3.2.3. LeNet

3.2.4. ViT

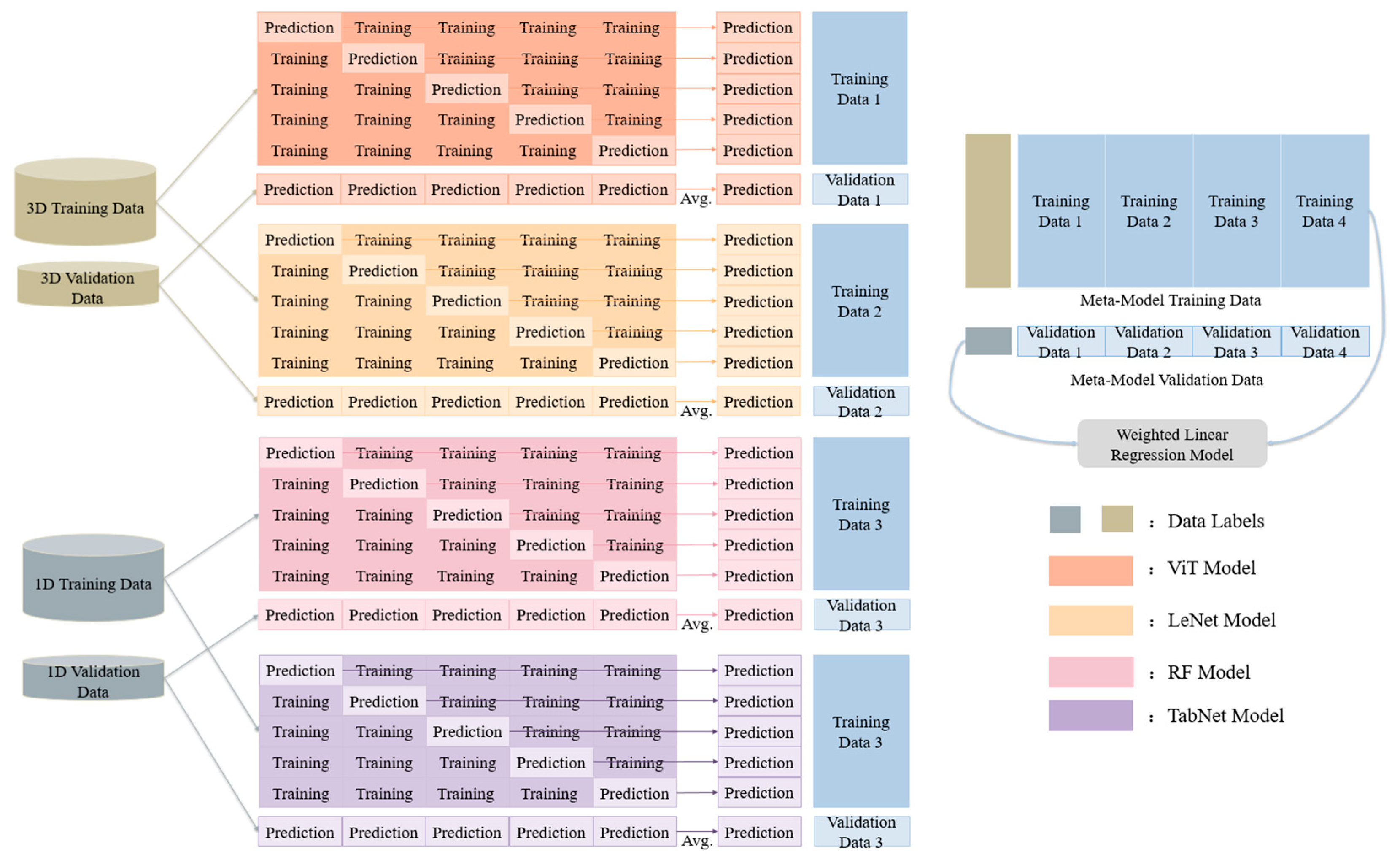

3.3. Stacking Model

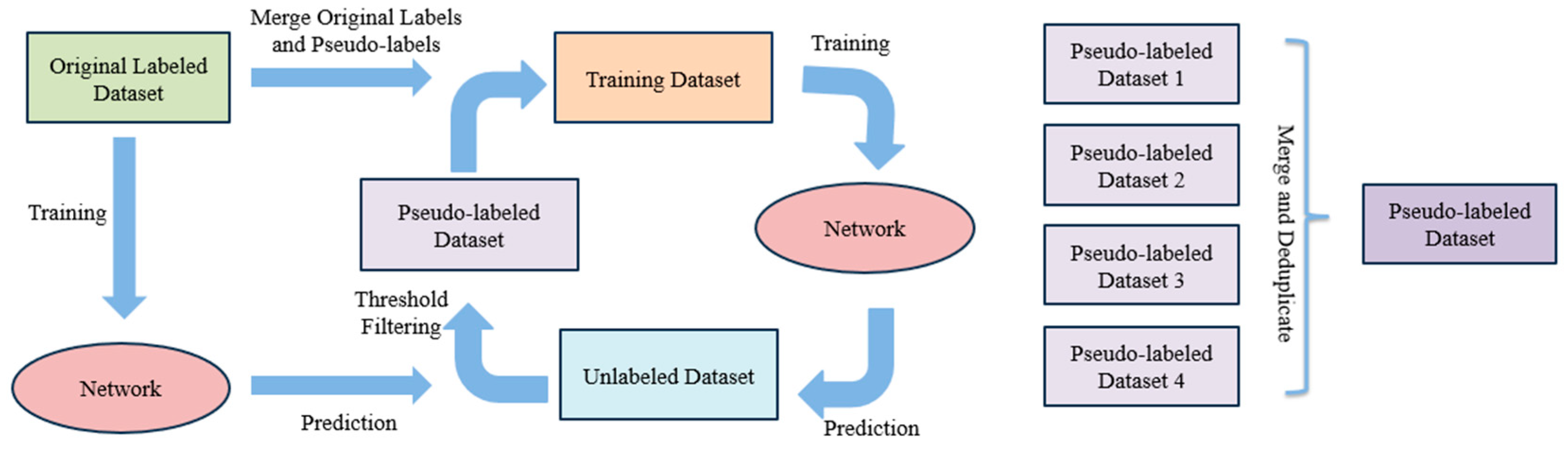

3.4. Pseudo-Labeling Technique

3.5. MFP_Stacking

3.5.1. Multidimensional Feature Collaborative Modeling

3.5.2. Pseudo-Label Augmentation

3.6. Model Evaluation Measures

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the LCFs

4.2. Model Parameter Settings

4.3. Comparison of LSM Results

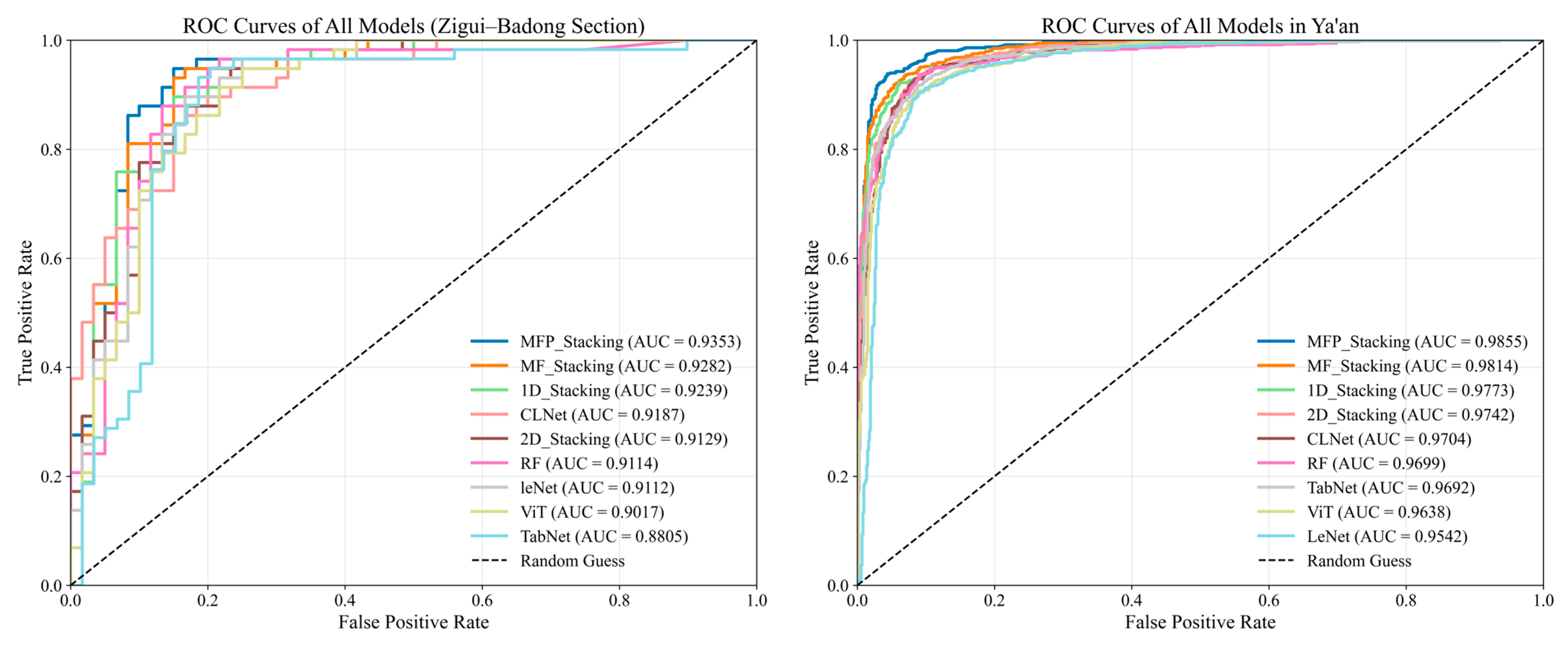

4.4. Model Performance Evaluation

5. Discussion

5.1. Model Complexity and Its Practical Implications

5.1.1. The Substantive Significance of Performance Gains in Early Warning Applications

5.1.2. Model Complexity

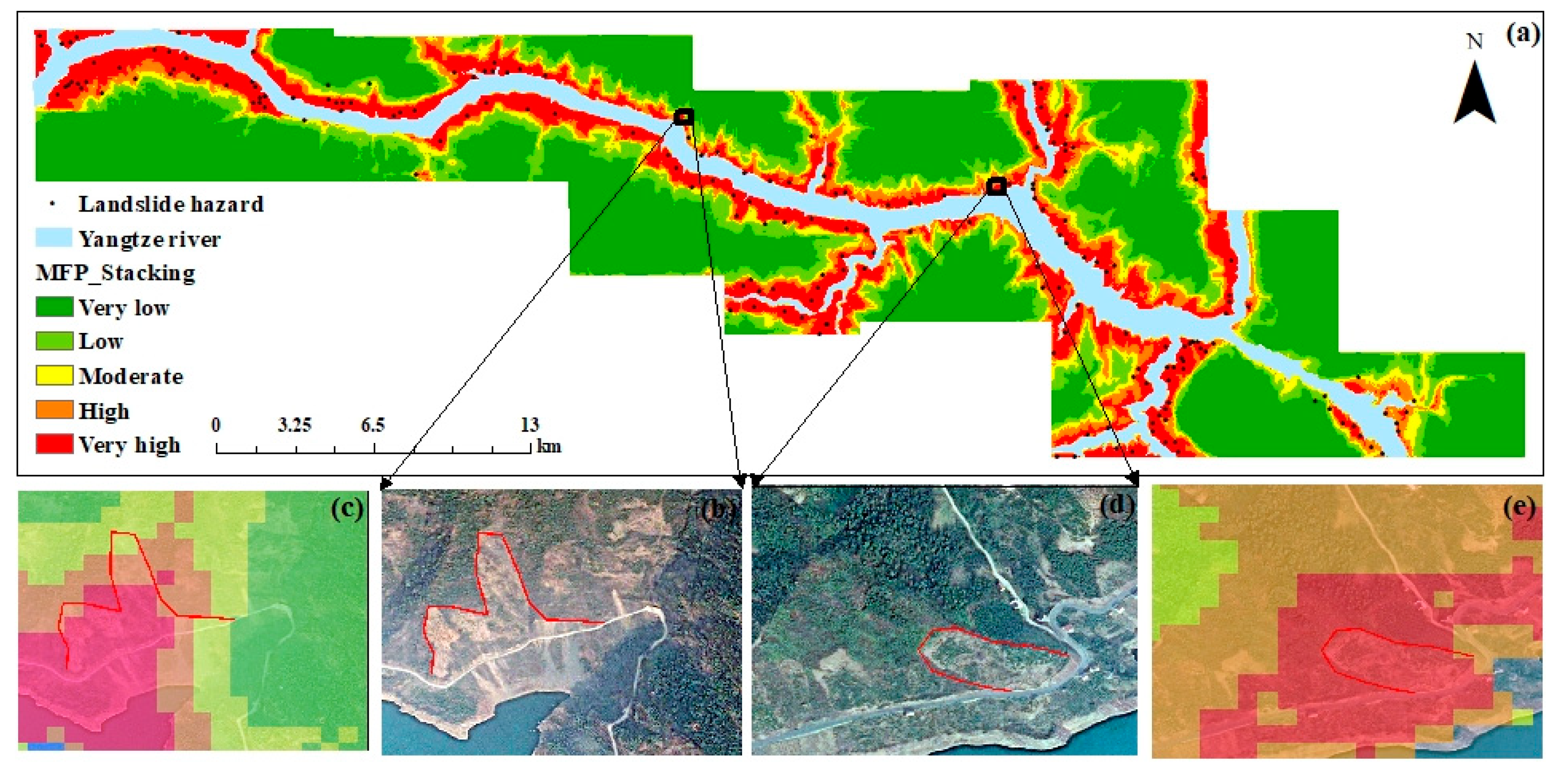

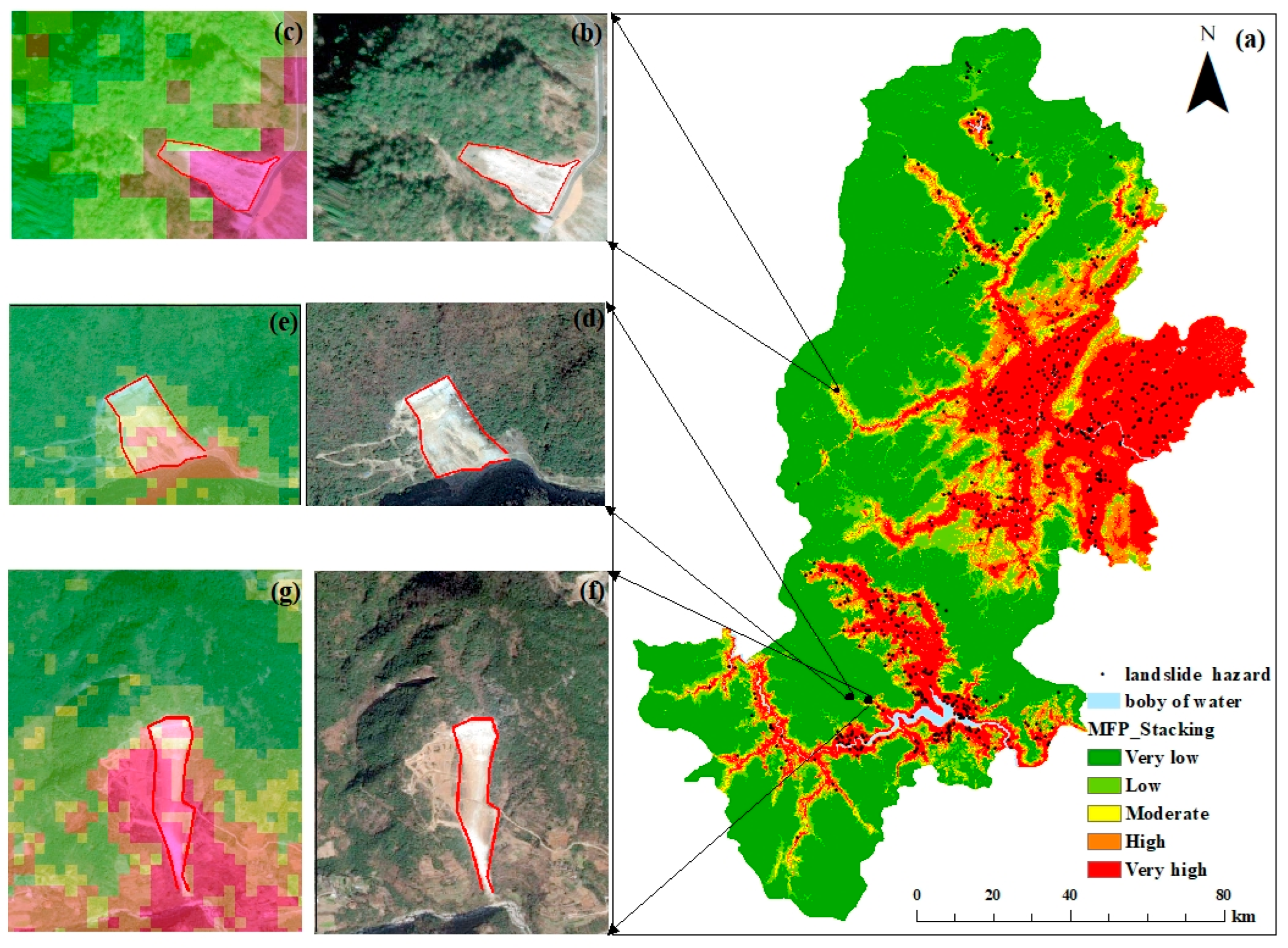

5.2. Visualization of an LSM for the Proposed Model

5.3. Model Stability Analysis

5.4. The Scalability and Limitations of the Model

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The MFP_Stacking model effectively integrates the advantages of various single classifiers, yielding a higher-quality landslide susceptibility zonation map.

- (2)

- The collaborative modeling of multidimensional features enables the model to simultaneously consider both spatial and non-spatial characteristics, significantly improving the performance of the ensemble model.

- (3)

- Incorporating pseudo-labeling techniques effectively alleviates data scarcity in small-sample scenarios, enabling the model to sustain robust and reliable learning performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dai, F.; Lee, C.F.; Ngai, Y. Landslide risk assessment and management: An overview. Eng. Geol. 2002, 64, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Chen, N.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y. A medium-sized landslide leads to a large disaster in Zhenxiong, Yunnan, China: Characteristics, mechanism and motion process. Landslides 2025, 22, 3365–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, V.; Niazi, Y.J.L. Development of hybrid wavelet packet-statistical models (WP-SM) for landslide susceptibility mapping. Landslides 2016, 13, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Gan, C.; Cao, W. Undersampling Ensemble and Deep Learning-Based Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Method for Geological Hazard Warning. In Proceedings of the China Automation Congress (CAC), Chongqing, China, 17–19 November 2023; pp. 7296–7301. [Google Scholar]

- CHU, J.-L.; DU, J.-Q. Landslide hazard evaluation of Wanzhou in Chongqing based on GIS. Geol. Bull. China 2008, 27, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar]

- Lingling, S.; Lianyou, L.; Chong, X.; Jingpu, W. Multi-models based landslide susceptibility evaluation—Illustrated with landslides triggered by Minxian earthquake. J. Eng. Geol. 2016, 24, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ercanoglu, M.; Gokceoglu, C. Assessment of landslide susceptibility for a landslide-prone area (north of Yenice, NW Turkey) by fuzzy approach. Environ. Geol. 2002, 41, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Chen, S.-C. Determining landslide susceptibility in Central Taiwan from rainfall and six site factors using the analytical hierarchy process method. Geomorphology 2009, 112, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, R.; Liang, Y.; Xu, S.; He, Y.; Yu, X.; Wu, W. Synergizing multiple machine learning techniques and remote sensing for advanced landslide susceptibility assessment: A case study in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merghadi, A.; Yunus, A.P.; Dou, J.; Whiteley, J.; ThaiPham, B.; Bui, D.T.; Avtar, R.; Abderrahmane, B. Machine learning methods for landslide susceptibility studies: A comparative overview of algorithm performance. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 207, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onagh, M.; Kumra, V.; Rai, P.K. Landslide susceptibility mapping in a part of Uttarkashi district (India) by multiple linear regression method. Int. J. Geol. Earth Environ. Sci. 2012, 2, 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, Z. GIS-based logistic regression for rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility mapping under different grid sizes in Yueqing, Southeastern China. Eng. Geol. 2019, 259, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Lin, Q.; Wang, Y. Landslide susceptibility mapping on a global scale using the method of logistic regression. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 17, 1411–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, L. Review on landslide susceptibility mapping using support vector machines. Catena 2018, 165, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Prakash, I.; Dou, J.; Singh, S.K.; Trinh, P.T.; Tran, H.T.; Le, T.M.; Van Phong, T.; Khoi, D.K.; Shirzadi, A. A novel hybrid approach of landslide susceptibility modelling using rotation forest ensemble and different base classifiers. Geocarto Int. 2020, 35, 1267–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Chen, B.; Mao, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L. Landslide susceptibility prediction modeling and interpretability based on self-screening deep learning model. Earth Sci. 2023, 48, 1696–1710. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, A.M.; Pradhan, B.; Dikshit, A.; Al-Katheri, M.M.; Matar, S.S.; Mahdi, A.M. Landslide susceptibility mapping using CNN-1D and 2D deep learning algorithms: Comparison of their performance at Asir Region, KSA. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameen, M.I.; Pradhan, B.; Lee, S. Application of convolutional neural networks featuring Bayesian optimization for landslide susceptibility assessment. Catena 2020, 186, 104249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Hong, H. Comparison of convolutional neural networks for landslide susceptibility mapping in Yanshan County, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, L. A deep learning algorithm using a fully connected sparse autoencoder neural network for landslide susceptibility prediction. Landslides 2020, 17, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, A.; Sehgal, V.K. Landslide susceptibility detection using ResNet. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON), Pune, India, 25–27 August 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, P.T.T.; Panahi, M.; Khosravi, K.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Kariminejad, N.; Cerda, A.; Lee, S. Evaluation of deep learning algorithms for national scale landslide susceptibility mapping of Iran. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patekar, A.S.; Daniel, E.; Seetha, S.; Manimekalai, M. Applying U-Net CNN Approach for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2024 Third International Conference on Intelligent Techniques in Control, Optimization and Signal Processing (INCOS), Krishnankoil, India, 14–16 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Du, A.; Hu, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, H. Landslide susceptibility evaluation based on active deformation and graph convolutional network algorithm. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1132722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Shi, Z.; Li, G.; Peng, M.; Liu, L.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, C. A novel deep learning framework for landslide susceptibility assessment using improved deep belief networks with the intelligent optimization algorithm. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 167, 106106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X. Application of transformer models to landslide susceptibility mapping. Sensors 2022, 22, 9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, J. Landslide risk evaluation in Shenzhen based on stacking ensemble learning and InSAR. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Peng, L.; Hong, H. Potential of ensemble learning to improve tree-based classifiers for landslide susceptibility mapping. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 4642–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Duan, G.; Peng, L. Landslide susceptibility mapping using rotation forest ensemble technique with different decision trees in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Trinder, J.C.; Niu, R. Object-oriented landslide mapping using ZY-3 satellite imagery, random forest and mathematical morphology, for the Three-Gorges Reservoir, China. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhu, L.; Niu, R.-q.; Trinder, C.J.; Peng, L.; Lei, T. Mapping landslide susceptibility at the Three Gorges Reservoir, China, using gradient boosting decision tree, random forest and information value models. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhuang, J.; Zheng, J.; Fan, H.; Kong, J.; Zhan, J. Application of Bayesian hyperparameter optimized random forest and XGBoost model for landslide susceptibility mapping. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 712240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Fu, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, F.; Wang, H.; Han, L. Bagging-based machine learning algorithms for landslide susceptibility modeling. Nat. Hazards 2022, 110, 823–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Chen, T.; Dou, J.; Plaza, A. A hybrid ensemble-based deep-learning framework for landslide susceptibility mapping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 108, 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wen, T.; Chen, N.; Tang, R. Assessment of Landslide Susceptibility Based on the Two-Layer Stacking Model—A Case Study of Jiacha County, China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Konečný, M.; Che, X.; Xu, S.; Li, P. Landslide susceptibility mapping by fusing convolutional neural networks and vision transformer. Sensors 2022, 23, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, T.; Dou, J.; Liu, G.; Plaza, A. Landslide susceptibility mapping considering landslide local-global features based on CNN and transformer. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 7475–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Luo, H.; Qin, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhou, X. Enhanced Landslide Susceptibility Assessment in Western Sichuan Utilizing DCGAN-Generated Samples. Land 2024, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Feng, W.; Yi, X.; Xue, Z.; Bai, L. Enhanced landslide susceptibility mapping in data-scarce regions via unsupervised few-shot learning. Gondwana Res. 2025, 138, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xi, W.; Huang, G.; Yang, Z.; Yang, K.; Zhuang, Y.; Cao, R.; Zhou, D.; Ma, Y. Landslide Susceptibility Evaluation Based on the Combination of Environmental Similarity and BP Neural Networks. Land 2025, 14, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Shan, H.; Wang, G. Spice: Semantic pseudo-labeling for image clustering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 7264–7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, L.; Li, Y.; Liang, G.; Zhang, Y. Pseudo Labeling Methods for Semi-Supervised Semantic Segmentation: A Review and Future Perspectives. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 35, 3054–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirpulatov, I.; Illarionova, S.; Shadrin, D.; Burnaev, E. Pseudo-labeling approach for land cover classification through remote sensing observations with noisy labels. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 82570–82583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xiong, T.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, J. Comparative assessment of the efficacy of the five kinds of models in landslide susceptibility map for factor screening: A case study at Zigui-Badong in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Gao, H. A landslide susceptibility map based on spatial scale segmentation: A case study at Zigui-Badong in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Li, J.; Luo, Z.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Pei, X. Analyzing the spatiotemporal vegetation dynamics and their responses to climate change along the Ya’an–Linzhi section of the Sichuan–Tibet Railway. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shu, X.; Liu, X.; Duan, Z.; Ran, Z. Risk assessment of debris flow in Ya’an city based on BP neural network. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Guangzhou, China, 20–22 December 2019; p. 012006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Li, W.; Hou, E.; Zhao, Z.; Deng, N.; Bai, H.; Wang, D. Landslide susceptibility mapping based on GIS and information value model for the Chencang District of Baoji, China. Arab. J. Geosci. 2014, 7, 4499–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, L.; Yamagishi, H. The application of GIS-based logistic regression for landslide susceptibility mapping in the Kakuda-Yahiko Mountains, Central Japan. Geomorphology 2005, 65, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ado, M.; Amitab, K.; Maji, A.K.; Jasińska, E.; Gono, R.; Leonowicz, Z.; Jasiński, M. Landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning: A literature survey. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YE, R.; LI, S.; GUO, F.; FU, X.; NIU, R. RS and GIS analysis on relationship between landslide susceptibility and land use change in Three Gorges Reservoir area. J. Eng. Geol. 2021, 29, 724–733. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Gao, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Dou, J.; Niu, R.; Plaza, A. BisDeNet: A new lightweight deep learning-based framework for efficient landslide detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 3648–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulesteix, A.-L.; Bender, A.; Lorenzo Bermejo, J.; Strobl, C. Random forest Gini importance favours SNPs with large minor allele frequency: Impact, sources and recommendations. Brief. Bioinform. 2012, 13, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingze, S.; Yingxu, S.; Xin, Z.; Jie, Z.; Degang, Y. Comparative analysis of the TabNet algorithm and traditional machine learning algorithms for landslide susceptibility assessment in the Wanzhou Region of China. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 7627–7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Gao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, C. A survey of remote sensing image classification based on CNNs. Big Earth Data 2019, 3, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Zafar, A.; Khalil, U. Comparative analysis of multiple conventional neural networks for landslide susceptibility mapping. Nat. Hazards 2023, 115, 673–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Tang, C.; Wang, X.; Zheng, B. A ViT-based multiscale feature fusion approach for remote sensing image segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlyshenko, B. Using stacking approaches for machine learning models. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE second international conference on data stream mining & processing (DSMP), Lviv, Ukraine, 21–25 August 2018; pp. 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L.; Hong, H. A comparative study of heterogeneous ensemble-learning techniques for landslide susceptibility mapping. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2021, 35, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kage, P.; Rothenberger, J.C.; Andreadis, P.; Diochnos, D. A review of pseudo-labeling for computer vision. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.07221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.E.; Lee, Y.J.; Dórea, J.R. Using pseudo-labeling to improve performance of deep neural networks for animal identification. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassani, H.; Silva, E.S. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov based test for comparing the predictive accuracy of two sets of forecasts. Econometrics 2015, 3, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Data Source | Study Area | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| positive sample | Resource and Environment Science Data Center | Zigui–Badong section | 197 |

| Ya’an City | 737 | ||

| negative sample | Information Value Method | Zigui–Badong section | 197 |

| Ya’an City | 737 |

| Data | Zigui–Badong Section | Ya’an City | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Type | LCFs | Data Source | Resolution | Data Source | Resolution |

| Topography & Geomorphology | Elevation | ASTER GDEM Version 2 | 30 m | ALOS 12.5 m Digital Elevation Model | Downsampled from 12.5 m to 30 m |

| Slope | |||||

| Aspect | |||||

| Plan Curvature | |||||

| Profile Curvature | |||||

| Geological Settings | Distance to Fault | Geological map from the Hubei Geological Bureau | 1:50,000 | Geological map from the China Geological Survey | 1:2,500,000 |

| Lithology | |||||

| Hydrometeorology | Rainfall | National Meteorological Information Center (2001–2010) | - | National Meteorological Information Center (2013–2020) | - |

| Distance to Drainage | ASTER GDEM Version 2 | - | 2 m Google imagery | - | |

| Land Cover | Land Use | Landsat 5 TM images (2010) | 30 m | ESA land cover data | 10 m |

| NDVI | Sentinel-2 satellite data (2020) | 10 m | |||

| Classifier | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Applicable Scenarios | Specific Role in Stacking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | Ensembles multiple decision trees and integrates predictions via a voting mechanism | Robust to overfitting, handles high-dimensional features, insensitive to outliers | Limited in capturing complex nonlinear relationships, less interpretable | Structured data classification, feature importance analysis | Processes 1D vectors, provides robust baseline predictions, enhances ensemble diversity and generalization |

| TabNet | Uses attention to select features, leveraging sequence to capture interactions. | Outperforms traditional DL on tabular data | High computational complexity, hyperparameter tuning challenging | Tabular data modeling requiring feature selection | Processes 1D vectors, captures complex interactions overlooked by RF, contributes diverse predictions |

| LeNet | Extracts local spatial features through convolutional layers and reduces dimensionality via pooling | Strong local feature extraction, efficient via parameter sharing, translation invariant | Limited receptive field, cannot capture global dependencies | Image classification, local pattern recognition | Processes 3D vectors, learns local environmental influence on landslides, provides spatially local perspective |

| ViT | Splits input into patches, models global dependencies via self-attention | Global receptive field, captures long-range dependencies | High data requirement, computationally expensive | Tasks needing global context understanding | Processes 3D vectors, models global spatial patterns, complements LeNet’s local focus |

| Model | Hyperparameter and Search Space |

|---|---|

| RF | n_estimators: {50, 60, 70, …, 150}; max_depth: {6, 8, 10, 12}; max_features: {“sqrt”, “auto”} |

| TabNet | n_d, n_a: {8, 9, 10, …, 16}; n_steps: {3, 4, 5}; Gamma: {1, 1.1, 1.2}; lr: {0.0001, 0.0005, …, 0.01} |

| LeNet | lr: ibid.; Batch size: {32, 64, 128}; Epochs: {300, 400, 500}; Patience: {10, 20, …, 60, Early stopping} |

| ViT | lr: ibid.; patch_size: {3}; Embedding dimension (ED): {64, 128, 256}; MLP ratio: {2, 4}; batch size: {32, 64, 128}; Epochs: {100, 200, 300, 400}; Patience: {10, 20, 30, 40, Early stopping} |

| CLNet | lr, patch_size, ED, MLP ratio, batch size, Epochs, Patience: ibid.; cnn_outdim: {32, 64, 128, 256} |

| Stacking | Meta-model type: {weighted linear regression}; Cross-validation folds: {3, 4, 5} |

| Model | Zigui–Badong Section | Ya’an City |

|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Parameters | |

| RF | n_estimators = 100; max_depth = 8; max_features = ‘auto’ | n_estimators = 50; max_depth = 8; max_features = ‘auto’ |

| TabNet | n_d = 14; n_a = 14; n_steps = 3; gamma = 1.1; lr = 0.001 | n_d = 13; n_a = 13; n_steps = 3; gamma = 1.1; lr = 0.001 |

| LeNet | batch_size = 64; epochs = 400; patience = 50; lr = 0.001 | batch_size = 64; epochs = 400; patience = 50; lr = 0.005 |

| ViT | patch_size = 3; ED = 128; patience = 20; lr = 0.0001; mlp_ratio = 4; batch size = 64; epochs = 200 | patch_size = 3; ED = 128; patience = 10; lr = 0.0001; mlp_ratio = 4; batch size = 64; epochs = 100 |

| CLNet | patch_siz, ED, patience, mlp_ratio, batch size, epochs: ibid.; lr = 0.001; cnn_outdim = 64 | patch_siz, ED, patience, mlp_ratio, batch size, epochs: ibid; lr = 0.001; cnn_outdim = 64 |

| 1D_Stacking | Single classifiers: SVM, TabNet, RF; Meta-model: weighted linear regression; cross-validation: 5-fold | Single classifiers: GBDT, TabNet, RF; Meta-model: weighted linear regression; cross-validation: 3-fold |

| 2D_Stacking | Single classifiers: CNN, LeNet, ViT; Meta-model: ibid.; cross-validation: ibid. | Single classifiers: LeNet, ViT; Meta-model: ibid.; cross-validation: ibid. |

| MF_Stacking | Single classifiers: RF, TabNet, LeNet, ViT, Meta-model: ibid.; cross-validation: ibid. | Single classifiers: RF, TabNet, LeNet, ViT, Meta-model: ibid.; cross-validation: ibid. |

| MFP_Stacking | Single classifiers: ibid., Meta-model: ibid.; cross-validation: ibid.; Number of pseudo-labels: 200 × 4; Segmented selection of pseudo-labels: 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1 | Single classifiers: ibid., Meta-model: ibid.; cross-validation: ibid. Number of pseudo-labels: 280 × 4; Segmented selection of pseudo-labels: 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1 |

| Model | Susceptible Partition | Zigui–Badong Section | Ya’an City | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | PL | LD | PC | PL | LD | ||

| TabNet | Very low | 0.3140 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.4177 | 0.0159 | 0.0380 |

| Low | 0.2188 | 0.0152 | 0.0695 | 0.1559 | 0.0238 | 0.1527 | |

| Moderate | 0.1548 | 0.0406 | 0.2623 | 0.1090 | 0.0529 | 0.4853 | |

| High | 0.1460 | 0.1878 | 1.2863 | 0.1071 | 0.1455 | 1.3581 | |

| Very high | 0.1665 | 0.7563 | 4.5423 | 0.2102 | 0.7619 | 3.6248 | |

| RF | Very low | 0.4741 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.4412 | 0.0172 | 0.0390 |

| Low | 0.1900 | 0.0152 | 0.0801 | 0.1523 | 0.0291 | 0.1911 | |

| Moderate | 0.0863 | 0.0152 | 0.1765 | 0.1333 | 0.0860 | 0.6450 | |

| High | 0.0912 | 0.0761 | 0.8346 | 0.1103 | 0.1812 | 1.6422 | |

| Very high | 0.1584 | 0.8934 | 5.6395 | 0.1628 | 0.6865 | 4.2159 | |

| LeNet | Very low | 0.4863 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.2441 | 0.0013 | 0.0050 |

| Low | 0.1282 | 0.0203 | 0.1584 | 0.2332 | 0.0212 | 0.0907 | |

| Moderate | 0.0931 | 0.0305 | 0.3271 | 0.1842 | 0.0463 | 0.2514 | |

| High | 0.1081 | 0.1320 | 1.2207 | 0.1390 | 0.1508 | 1.0850 | |

| Very high | 0.1843 | 0.8173 | 4.4344 | 0.1996 | 0.7804 | 3.9107 | |

| VIT | Very low | 0.6326 | 0.0101 | 0.0160 | 0.5172 | 0.0212 | 0.0409 |

| Low | 0.0624 | 0.0101 | 0.1627 | 0.1285 | 0.0344 | 0.2677 | |

| Moderate | 0.0528 | 0.0305 | 0.5772 | 0.0802 | 0.0503 | 0.6271 | |

| High | 0.0731 | 0.0863 | 1.1810 | 0.0795 | 0.0979 | 1.2318 | |

| Very high | 0.1792 | 0.8629 | 4.8149 | 0.1947 | 0.7963 | 4.0887 | |

| CLNet | Very low | 0.6594 | 0.0152 | 0.0231 | 0.4860 | 0.0145 | 0.0299 |

| Low | 0.0568 | 0.0203 | 0.3577 | 0.1653 | 0.0304 | 0.1840 | |

| Moderate | 0.0490 | 0.0406 | 0.8294 | 0.0615 | 0.0370 | 0.6018 | |

| High | 0.0652 | 0.0914 | 1.4002 | 0.0521 | 0.0556 | 1.0653 | |

| Very high | 0.1696 | 0.8325 | 4.9082 | 0.2349 | 0.8624 | 3.6709 | |

| 1D_Stacking | Very low | 0.4534 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.5615 | 0.0291 | 0.0518 |

| Low | 0.1804 | 0.0152 | 0.0844 | 0.0768 | 0.0159 | 0.2066 | |

| Moderate | 0.0992 | 0.0254 | 0.2559 | 0.0658 | 0.0251 | 0.3818 | |

| High | 0.0960 | 0.1371 | 1.4276 | 0.0748 | 0.0992 | 1.3260 | |

| Very high | 0.1709 | 0.8223 | 4.8109 | 0.2210 | 0.8307 | 3.7583 | |

| 2D_Stacking | Very low | 0.5633 | 0.0051 | 0.0090 | 0.4974 | 0.0093 | 0.0186 |

| Low | 0.1212 | 0.0152 | 0.1256 | 0.1383 | 0.0278 | 0.2009 | |

| Moderate | 0.0663 | 0.0355 | 0.5356 | 0.0752 | 0.0410 | 0.5453 | |

| High | 0.0764 | 0.1218 | 1.5936 | 0.0748 | 0.0833 | 1.1146 | |

| Very high | 0.1727 | 0.8223 | 4.7618 | 0.2143 | 0.8386 | 3.9129 | |

| MF_Stacking | Very low | 0.5484 | 0.0051 | 0.0093 | 0.4884 | 0.0079 | 0.0162 |

| Low | 0.1304 | 0.0101 | 0.0778 | 0.1367 | 0.0278 | 0.2032 | |

| Moderate | 0.0713 | 0.0254 | 0.3561 | 0.0823 | 0.0410 | 0.4982 | |

| High | 0.0813 | 0.1167 | 1.4352 | 0.0830 | 0.0833 | 1.0034 | |

| Very high | 0.1685 | 0.8426 | 4.9990 | 0.2095 | 0.8399 | 4.0093 | |

| MFP_Stacking | Very low | 0.5190 | 0.0051 | 0.0098 | 0.5318 | 0.0093 | 0.0174 |

| Low | 0.1471 | 0.0051 | 0.0345 | 0.1113 | 0.0251 | 0.2259 | |

| Moderate | 0.0818 | 0.0152 | 0.1863 | 0.0568 | 0.0331 | 0.5823 | |

| High | 0.0913 | 0.1015 | 1.1114 | 0.0866 | 0.1138 | 1.3140 | |

| Very high | 0.1608 | 0.8731 | 5.4310 | 0.2135 | 0.8188 | 3.8348 | |

| Research Area | Model | Performance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oa | Kappa | Precision | Recall | F1 | MCC | Auc | ||

| Zigui–Badong section | TabNet | 0.8475 | 0.6949 | 0.8361 | 0.8644 | 0.8500 | 0.6953 | 0.8805 |

| RF | 0.8559 | 0.7124 | 0.8028 | 0.9138 | 0.8618 | 0.7174 | 0.9114 | |

| LeNet | 0.8136 | 0.6289 | 0.7368 | 0.9655 | 0.8358 | 0.6601 | 0.9112 | |

| ViT | 0.8305 | 0.6619 | 0.7794 | 0.9138 | 0.8413 | 0.6716 | 0.9017 | |

| CLNet | 0.8475 | 0.6954 | 0.8125 | 0.8966 | 0.8525 | 0.6900 | 0.9187 | |

| 1D_Sk | 0.8560 | 0.7125 | 0.8060 | 0.9310 | 0.8640 | 0.7209 | 0.9239 | |

| 2D_Sk | 0.8475 | 0.6955 | 0.8030 | 0.9138 | 0.8548 | 0.7020 | 0.9129 | |

| MF_Sk | 0.8728 | 0.7463 | 0.8209 | 0.9483 | 0.8800 | 0.7551 | 0.9282 | |

| MFP_Sk | 0.8813 | 0.7632 | 0.8333 | 0.9483 | 0.8871 | 0.7703 | 0.9353 | |

| Ya’an City | TabNet | 0.9127 | 0.8254 | 0.9127 | 0.9126 | 0.9128 | 0.8254 | 0.9692 |

| RF | 0.9161 | 0.8322 | 0.9189 | 0.9127 | 0.9158 | 0.8322 | 0.9699 | |

| LeNet | 0.8876 | 0.7752 | 0.8448 | 0.9496 | 0.8941 | 0.7812 | 0.9542 | |

| ViT | 0.9053 | 0.8106 | 0.8961 | 0.9168 | 0.9064 | 0.8108 | 0.9639 | |

| CLNet | 0.9210 | 0.8419 | 0.9187 | 0.9237 | 0.9212 | 0.8419 | 0.9703 | |

| 1D_Sk | 0.9209 | 0.8417 | 0.9065 | 0.9386 | 0.9223 | 0.8423 | 0.9773 | |

| 2D_Sk | 0.9217 | 0.8433 | 0.9143 | 0.9305 | 0.9223 | 0.8435 | 0.9742 | |

| MF_Sk | 0.9285 | 0.8569 | 0.9188 | 0.9401 | 0.9293 | 0.8572 | 0.9814 | |

| MFP_Sk | 0.9380 | 0.8760 | 0.9281 | 0.9496 | 0.9387 | 0.8763 | 0.9855 | |

| Research Area | Model | Parameter Count | Training Time per Epoch (s/epoch) | Total Training Time (s) | Inference Time (ms/Sample) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zigui–Badong section | RF | No | No | 0.771 | 1.9600 |

| TabNet | 4.24 K | 0.4094 | 52 | 0.6480 | |

| LeNet | 0.245 M | 0.1252 | 47 | 0.2241 | |

| ViT | 2.21 M | 1.5833 | 57 | 1.8513 | |

| CLNet | 2.32 M | 2.0976 | 86 | 1.7733 | |

| Ya’an City | RF | No | No | 0.554 | 0.5054 |

| TabNet | 5.37 K | 0.9500 | 133 | 0.5165 | |

| LeNet | 0.245 M | 0.4600 | 140 s | 0.1988 | |

| ViT | 2.21 M | 5.1785 | 145 | 1.2743 | |

| CLNet | 2.32 M | 7.4815 | 202 | 2.3556 |

| Research Area | Model | Percentage of the Training Set | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | ||

| Zigui–Badong section | TabNet | 0.3071 | 0.3427 | 0.3576 | 0.8529 | 0.8590 | 0.8754 | 0.8805 | 0.8685 | 0.8476 |

| RF | 0.8689 | 0.8774 | 0.8842 | 0.8981 | 0.9052 | 0.9009 | 0.9114 | 0.8955 | 0.8864 | |

| LeNet | 0.8847 | 0.9005 | 0.9068 | 0.9137 | 0.9182 | 0.9143 | 0.9112 | 0.9095 | 0.9132 | |

| ViT | 0.7612 | 0.8544 | 0.9002 | 0.9010 | 0.9010 | 0.9105 | 0.9017 | 0.9049 | 0.9209 | |

| CLNet | 0.8451 | 0.8744 | 0.8953 | 0.8985 | 0.9114 | 0.9191 | 0.9187 | 0.9137 | 0.9200 | |

| 1D_Sk | 0.8809 | 0.8868 | 0.8976 | 0.9166 | 0.9180 | 0.9209 | 0.9239 | 0.9172 | 0.9114 | |

| 3D_Sk | 0.8874 | 0.8991 | 0.9131 | 0.9139 | 0.9188 | 0.9150 | 0.9130 | 0.9100 | 0.9250 | |

| MF_Sk | 0.9019 | 0.9127 | 0.9188 | 0.9206 | 0.9286 | 0.9276 | 0.9282 | 0.9288 | 0.9305 | |

| Ya’an City | TabNet | 0.8724 | 0.9292 | 0.9442 | 0.9555 | 0.9472 | 0.9614 | 0.9692 | 0.9711 | 0.9750 |

| RF | 0.9361 | 0.9501 | 0.9603 | 0.9686 | 0.9703 | 0.9705 | 0.9699 | 0.9726 | 0.9739 | |

| LeNet | 0.9294 | 0.9359 | 0.9423 | 0.9484 | 0.9522 | 0.9544 | 0.9542 | 0.9518 | 0.9493 | |

| ViT | 0.9218 | 0.9235 | 0.9312 | 0.9399 | 0.9501 | 0.9606 | 0.9639 | 0.9445 | 0.9432 | |

| CLNet | 0.9251 | 0.9409 | 0.9491 | 0.9551 | 0.9653 | 0.9704 | 0.9703 | 0.9721 | 0.9740 | |

| 1D_Sk | 0.9405 | 0.9539 | 0.9609 | 0.9663 | 0.9716 | 0.9740 | 0.9773 | 0.9727 | 0.9754 | |

| 3D_Sk | 0.9306 | 0.9370 | 0.9474 | 0.9544 | 0.9658 | 0.9657 | 0.9742 | 0.9740 | 0.9701 | |

| MF_Sk | 0.9491 | 0.9586 | 0.9637 | 0.9679 | 0.9760 | 0.9777 | 0.9814 | 0.9773 | 0.9788 | |

| Research Area | Ratios; Pseudo-Label Selection Strategy; Final Number | AUC | W | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zigui–Badong section | 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 1:0:0; 200 × 4; 550 | 0.9383 | 0.87 | 0.0619 |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 7:3:0; 200 × 4; 550 | 0.9223 | 0.82 | 0.0653 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:4:0; 200 × 4; 550 | 0.9216 | 0.81 | 0.0983 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 5:5:0; 200 × 4; 550 | 0.9184 | 0.78 | 0.0963 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1; 200 × 4; 550 | 0.9353 | 0.78 | 0.0989 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:2:2; 200 × 4; 550 | 0.9106 | 0.75 | 0.0733 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1; 100 × 4; 270 | 0.9349 | 0.83 | 0.1312 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1; 300 × 4; 850 | 0.9133 | 0.76 | 0.0747 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1; 400 × 4; 1090 | 0.8934 | 0.72 | 0.0558 | |

| Ya’an City | 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 1:0:0; 280 × 4; 760 | 0.9892 | 0.90 | 0.1531 |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 7:3:0; 280 × 4; 760 | 0.9751 | 0.87 | 0.1689 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:4:0; 280 × 4; 760 | 0.9734 | 0.80 | 0.1626 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 5:5:0; 280 × 4; 760 | 0.9710 | 0.84 | 0.1531 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1; 280 × 4; 760 | 0.9855 | 0.81 | 0.1760 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:2:2; 280 × 4; 760 | 0.9694 | 0.79 | 0.1536 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1; 140 × 4; 380 | 0.9813 | 0.81 | 0.2144 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1; 420 × 4; 1120 | 0.9726 | 0.78 | 0.1262 | |

| 1–0.8:0.8–0.6:0.6–0.4 = 6:3:1; 560 × 4; 1500 | 0.9609 | 0.77 | 0.0851 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Xu, L.; Wu, K.; Liu, H.; Zhou, D. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using a Stacking Model Based on Multidimensional Feature Collaboration and Pseudo-Labeling Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010430

Li X, Xu L, Wu K, Liu H, Zhou D. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using a Stacking Model Based on Multidimensional Feature Collaboration and Pseudo-Labeling Techniques. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010430

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xinyu, Lina Xu, Ke Wu, Huize Liu, and Dandan Zhou. 2026. "Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using a Stacking Model Based on Multidimensional Feature Collaboration and Pseudo-Labeling Techniques" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010430

APA StyleLi, X., Xu, L., Wu, K., Liu, H., & Zhou, D. (2026). Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using a Stacking Model Based on Multidimensional Feature Collaboration and Pseudo-Labeling Techniques. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010430