Abstract

Peanut, as an important economic crop, is widely cultivated and rich in nutrients. Classifying peanuts based on the number of seeds helps assess yield and economic value, providing a basis for selection and breeding. However, traditional peanut grading relies on manual labor, which is inefficient and time-consuming. To improve detection efficiency and accuracy, this study proposes an improved BTM-YOLOv8 model and tests it on an independently designed pod detection device. In the backbone network, the BiFormer module is introduced, employing a dual-route attention mechanism with dynamic, content-aware, and query-adaptive sparse attention to extract features from densely packed peanuts. In addition, the Triple Attention mechanism is incorporated to strengthen the model’s multidimensional interaction and feature responsiveness. Finally, the original CIoU loss function is replaced with MPDIoU loss, simplifying distance metric computation and enabling more scale-focused optimization in bounding box regression. The results show that BTM-YOLOv8 has stronger detection performance for ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanut pods, with precision, recall, mAP50, and F1 score reaching 98.40%, 96.20%, 99.00%, and 97.29%, respectively. Compared to the original YOLOv8, these values improved by 3.9%, 2.4%, 1.2%, and 3.14%, respectively. Ablation experiments further validate the effectiveness of the introduced modules, showing reduced attention to irrelevant information, enhanced target feature capture, and lower false detection rates. Through comparisons with various mainstream deep learning models, it was further demonstrated that BTM-YOLOv8 performs well in detecting ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanut pods. When comparing the device’s detection results with manual counts, the R2 value was 0.999, and the RMSE value was 12.69, indicating high accuracy. This study improves the efficiency of ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanut pod detection, reduces labor costs, and provides quantifiable data support for breeding, offering a new technical reference for the detection of other crops.

1. Introduction

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) is one of the major oil and food crops worldwide [1], cultivated in more than 100 countries, particularly in Asia and Africa [2]. Grading and sorting peanuts is a crucial step prior to marketing, as it directly influences product quality classification and the realization of premium pricing. At the same time, sorting serves as an essential process in oil extraction, food processing, breeding, and consumption. Through effective screening, the diversified utilization of peanut products can be promoted while also reducing waste and improving resource utilization. However, traditional peanut screening methods, such as manual and mechanical sorting, are inefficient and prone to damaging the peanut pods, resulting in poor grading outcomes. This limitation hinders the development of the peanut industry. Therefore, achieving efficient and accurate peanut quality detection and classification is of great significance for improving the production efficiency and economic benefits of the peanut industry.

In recent years, with the continuous advancement of computer vision technology, deep learning techniques have been increasingly applied in the field of image recognition. This has enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of automated recognition tasks and expanded the scope of image recognition technology applications. From security monitoring [3,4,5] and medical image analysis [6,7] to autonomous driving [8,9] and industrial visual inspection [10,11], deep learning has demonstrated transformative potential due to its powerful feature extraction capacity and high recognition accuracy. Especially in the field of smart agriculture, significant achievements have been made in the application of deep learning technology, which has become a key technology in this domain.

This study proposes an improved BTM-YOLOv8 peanut pod detection model, which is integrated into a self-designed and fabricated conveyor belt peanut pod detection device, achieving rapid detection and precise counting of ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanuts. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

(1) A dual-route attention mechanism is introduced into the backbone network. By combining coarse-grained regional filtering with fine-grained feature interaction, this mechanism effectively captures long-range dependencies and significantly enhances the model’s capacity for peanut feature extraction.

(2) A branched three-dimensional attention mechanism is employed to establish connections across channel and spatial dimensions. This design substantially improves the model’s sensitivity to subtle features, enriching feature representation and enhancing discriminative capability.

(3) A conveyor belt peanut pod detection device was designed and fabricated, enabling rapid detection and counting of ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanuts.

2. Related Work

In agricultural applications, researchers have explored various methods to detect and classify peanuts and other crops. For example, Chen et al. [12] developed an improved YOLOv8-based CES-YOLOv8 model for strawberry maturity detection, achieving an accuracy of 88.2%. Megalingam et al. [13] proposed an Integrated Fuzzy and Deep Learning Model (IFDM) for coconut maturity grading, reaching an accuracy of 86.3%. Liu et al. [14] introduced a lightweight YOLOv8-LSW model, which replaces the backbone with the LeYOLO-small module, incorporates the ShuffleAttention mechanism, and employs the WIoUv3 loss function, thereby achieving 95.3% accuracy in bitter melon disease detection and offering a lightweight, efficient solution for real-time precision management. Zhao et al. [15] designed a novel Faster R-CNN architecture for disease detection in strawberry leaves, flowers, and fruits, addressing challenges posed by complex backgrounds and small lesions. The model successfully identified seven types of strawberry diseases with a mean average precision (mAP) of 92.18% and an average detection time of 229 ms. Liang et al. [16] developed IPS-YOLO, an improved YOLOv5-based segmentation model for tomato pruning point detection, achieving precision, recall, and mAP values of 93.6%, 86.1%, and 91.2%, respectively. Moallem et al. [17] developed a computer vision-based grading algorithm for Golden Delicious apples, achieving 92.5% accuracy in distinguishing healthy from defective apples and 89.2% accuracy in classifying apples into first-class, second-class, and unqualified categories using a Support Vector Machine (SVM). Li et al. [18] extracted peanut features such as aspect ratio, Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), and Hu invariant moments, and employed SVM to classify single-, double-, and triple-kernel peanuts. The results showed that aspect ratio achieved the highest classification accuracy (96.72%), while HOG and Hu moment features both yielded 81.97%. Momin et al. [19] utilized image processing algorithms to identify split, contaminated, and defective beans, with accuracies of 96%, 75%, and 98%, respectively. Olgun et al. [20] proposed a classification method for wheat kernels using Dense SIFT features combined with SVM, achieving 88.33% accuracy. Koklu et al. [21] applied deep learning methods to classify five common rice varieties in Turkey, with classification success rates of 99.87% for Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), 99.95% for Deep Neural Networks (DNN), and 100% for Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN).

In peanut detection, some deep learning-based methods have achieved notable results. Yang et al. [22] applied an improved deep convolutional neural network to classify 12 peanut varieties, reaching an average accuracy of 96.7%. Guo et al. [23] employed a Deep Module Combination Optimization (DMCO) algorithm integrated with hyperspectral imaging to improve detection accuracy of aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) in peanuts, achieving a mean absolute error of 0.945 in the validation set. Huang et al. [24] addressed the inefficiency of traditional peanut quality grading methods by proposing LE-YOLO, a lightweight and efficient YOLOv8n-based model for peanut quality detection. Although some deep learning-based methods have achieved good results, most of the research is still limited to the laboratory stage and has not been applied in practical production.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Construction

The number of kernels within a peanut pod is a key characteristic for evaluating its fruit structure. Based on the number of kernels contained inside, peanut pods can be classified into single-kernel pods, double-kernel pods, triple-kernel pods, and multi-kernel pods. Single-kernel pods are usually smaller in size but contain relatively plump kernels; double-kernel and triple-kernel pods contain two and three kernels, respectively; multi-kernel pods contain four or more kernels.

The data for this study were collected from the Digital Agriculture Research Institute of the Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, using the peanut variety “Quan Hua 557.” This variety exhibits a rich range of pod traits, with a large span of pod sizes and diverse appearance variations. All peanut images were captured on a conveyor belt device with a black background. The device, as shown in Figure 1, is constructed with aluminum profiles, where the conveyor belt frame uses 4080-type profiles and other parts use 4040-type profiles. The system is equipped with a continuously variable-speed motor (model: 5RK90RGU-CF) and a US-52 controller for speed regulation. An industrial camera (model HT-GE1000C-T-CL) with a resolution of 10 million pixels was used for image acquisition. Two adjustable lamp holders were installed on both sides of the camera, each equipped with a dimmable LED light source. The industrial camera was mounted 50 cm above the conveyor belt, with the focal length adjusted to ensure optimal imaging quality.

Figure 1.

Conveyor-type peanut pod detection device. a. Control box; b. Variable-speed motor; c. Conveyor belt; d. Industrial camera lens; e. Industrial camera; f. Adjustable lamp holder; g. LED light source.

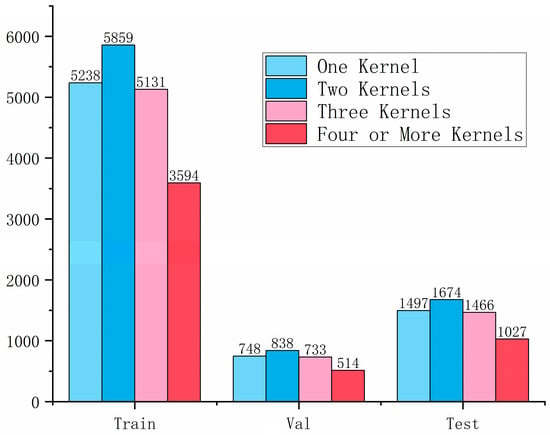

Peanuts were transported by the conveyor belt into the imaging area, where RGB images were captured using the industrial camera mounted above. A total of 432 peanut images were collected, comprising 8328 peanut targets. The diversity of these targets enables the model to learn the features and variations in different peanut targets. To increase dataset diversity and size, accelerate model convergence during training, improve detection accuracy, and enhance model generalization ability [25], several data augmentation techniques were applied, including rotation, brightness adjustment, Gaussian blur, contrast adjustment, and random translation [26]. Subsequently, the images were manually annotated using LabelImg (v1.8.0) software to generate annotation files containing bounding box coordinates and peanut class labels. The annotated images and corresponding labels were randomly shuffled and divided into training, validation, and testing sets at a ratio of 7:1:2. The dataset contains 1582 images, with a total of 28,319 peanut targets. Of these, 1108 images are used for training, 158 for validation, and the remaining 316 for testing. The number of samples in each subset is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The number of samples for each category in different datasets.

3.2. Model Improvements

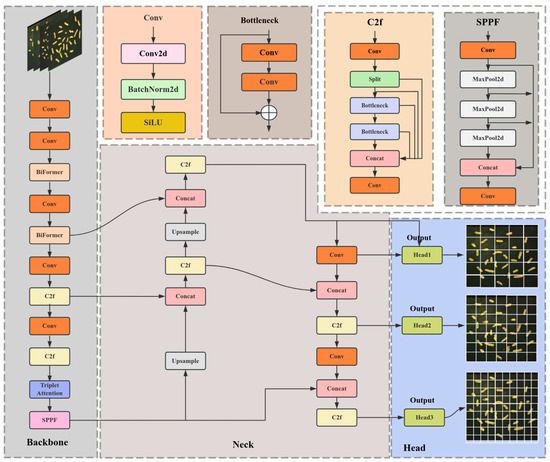

The YOLOv8 model [27] is an advanced version of the You Only Look Once series, designed as a real-time single-stage multi-task detection framework. It offers advantages such as fast inference speed and low memory consumption [28]. The model adopts a hierarchical three-stage architecture, consisting of a backbone network, a neck, and a detection head. The backbone is composed of standard convolutional modules (Conv), cross-stage feature fusion modules (C2f), and a fast spatial pyramid pooling module (SPPF) [12]. The neck is based on a bidirectional feature pyramid (BiFPN-PAN), which dynamically aggregates multi-resolution features from the backbone through weighted bidirectional cross-scale connections. In this structure, the top-down pathway fuses deep semantic information to enhance small-object detection, while the bottom-up pathway strengthens shallow detail features to improve localization accuracy [29]. The detection head adopts a decoupled design, separating classification and regression into independent branches. The classification branch performs multi-label prediction using binary cross-entropy loss (BCE Loss), while the regression branch combines distribution focal loss (DFL) with complete intersection-over-union loss (CIoU Loss). Bounding box coordinates are modeled via discrete probability distributions, and an anchor-free mechanism directly predicts target center offsets and scale factors. End-to-end optimization is achieved through a dynamic task-aligned label assignment strategy (Task-Aligned Assigner) [30].

Building upon the YOLOv8 structure, this study proposes the improved BTM-YOLOv8 network. The modifications include the introduction of a BiFormer module into the backbone, which applies dynamic sparse attention to flexibly adjust attention weights according to input image features. A Triple Attention mechanism is incorporated above the SPPF layer to enhance multidimensional feature interactions. Additionally, the original loss function is replaced with MPDIoU, improving bounding box regression by simplifying distance computation and focusing on scale alignment. The overall architecture of the improved BTM-YOLOv8 model is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the BTM-YOLOv8 network.

3.2.1. BiFormer Module in the Backbone Network

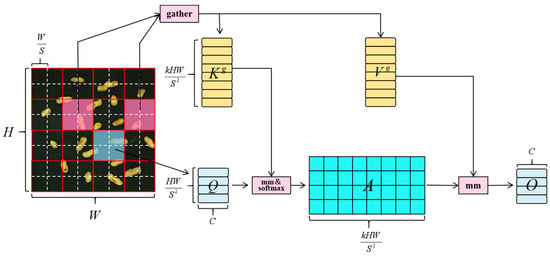

In this study, to address the insufficient feature extraction capability of the original network in peanut kernel recognition tasks, the BiFormer module [31] was integrated into the backbone to enhance feature learning. The structure of the module is illustrated in Figure 4. BiFormer is a novel vision Transformer architecture, whose core innovation lies in the Bi-Level Routing Attention (BRA) mechanism. This mechanism employs dynamic sparse attention to flexibly adjust attention weights according to the characteristics of the input image, allocating varying levels of attention to different positions or features. In doing so, it captures long-range dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency [32]. Compared with traditional Transformer models, which rely on global self-attention and thus suffer from excessive computational complexity, BiFormer substantially reduces computational cost while improving efficiency and performance in prediction tasks [33].

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the BiFormer module.

Specifically, in the vision Transformer, the Bi-Level Routing Attention (BRA) mechanism first partitions the input feature map into S × S non-overlapping regions, with each region containing feature vectors. This can be expressed as follows:

The queries and keys are then subjected to region-level average pooling to obtain region-level queries Qr and keys Kr:

Here, Q and K are the query and key tensors generated through linear projection. Next, an inter-region affinity map is constructed:

The affinity map Ar is then pruned to retain only the top-k connections for each region, yielding the routing index matrix . Based on Ir, the corresponding key and value tensors are gathered:

Here, V denotes the value tensor obtained through linear projection. Finally, attention operations are applied to the collected key and value tensors:

where dwconv represents depthwise separable convolution, which introduces local contextual information.

In the task of recognizing the number of peanut kernels, BiFormer’s dual-layer routing mechanism effectively distinguishes the boundary features of attached peanut seeds and suppresses background noise (such as soil particles or broken shells) through adaptive weighting, thereby capturing the boundary features of the peanut kernels and avoiding misdetection. Furthermore, its sparse attention mechanism is particularly suitable for processing high-resolution images in later real-time detection stages, enabling more precise localization and recognition of peanut pods while ensuring computational efficiency.

3.2.2. Triplet Attention Module

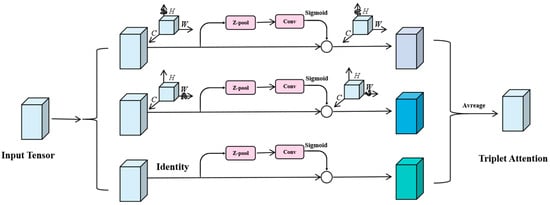

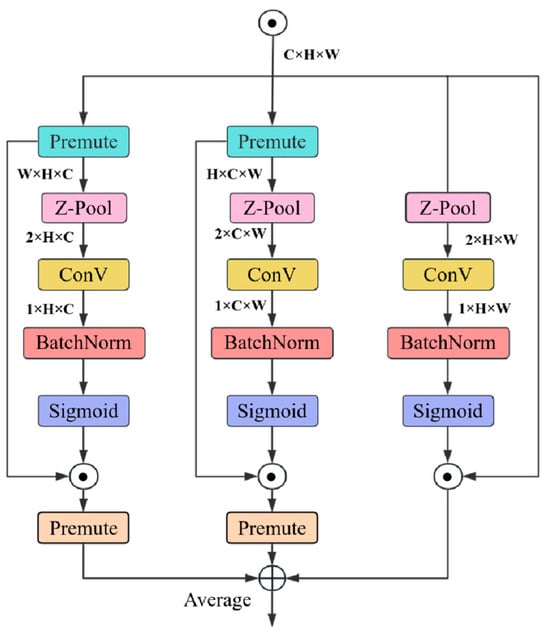

To enhance cross-dimensional interactions in image information and enrich feature representation, this study incorporates the Triplet Attention Module proposed by Misra et al. [34]. This module is a lightweight, parameter-free attention mechanism that emphasizes cross-dimensional feature interaction without introducing computational bottlenecks. Its core principle lies in modeling cross-dimensional interactions between channels and spatial dimensions through a combination of rotation, pooling, and convolution to compute attention weights. As shown in Figure 5, the Triplet Attention Module consists of three parallel branches. The first two branches capture cross-dimensional interactions between the channel dimension (C) and the spatial dimensions (H or W), while the third branch establishes spatial attention. The outputs of all three branches are aggregated using simple averaging, thereby addressing the limitations of traditional attention mechanisms (e.g., SE, CBAM), which often neglect coupling between different dimensions.

Figure 5.

Architecture of the Triplet Attention Network.

The Triplet Attention (TA) module captures cross-dimensional information through three parallel branches to compute attention weights. Given an input tensor , each branch processes it independently, as illustrated in Figure 6. In the first branch, interactions are established between the height (H) and channel (C) dimensions. The input tensor A is rotated 90° counterclockwise along the height dimension to obtain A1 (dimension: W × H × C). After applying the z-pooling operation, it is simplified to (dimension: 2 × H × C). A convolution layer followed by batch normalization generates an intermediate tensor of size 1 × H × W. This tensor is passed through a sigmoid activation function to produce attention weights, which are applied to A1 and then rotated 90° clockwise to restore the original dimension. In the second branch, the interaction between the width (W) and channel (C) dimensions is captured. The input tensor A is rotated 90° counterclockwise along the width dimension to form A2 (dimension: H × C × W). After z-pooling, a simplified representation is obtained. A convolution and batch normalization are applied to generate an intermediate tensor of size 1 × H × W. The resulting tensor is activated by a sigmoid function to produce attention weights, which are applied to A2 and rotated 90° clockwise to recover the original dimension. The third branch is designed to capture the spatial dependency of the input tensor. A z-pooling operation is performed along the channel dimension to obtain A3 (dimension: 2 × H × W). After passing through a convolution and batch normalization, an intermediate tensor of size 1 × H × W is generated. Following sigmoid activation, the attention weights are directly applied to the original input tensor.

Figure 6.

Operational flow of the Triplet Attention Module.

For the input tensor , the process of obtaining the refined attention-applied tensor y from the triple-attention mechanism is as follows:

Here, denotes the sigmoid activation function; , , and represent the standard two-dimensional convolutional layers defined by the kernel size k in the three branches of the triple-attention mechanism; , , and indicate the cross-dimensional attention weights computed in the triple-attention module; and and represent the tensors rotated clockwise by 90∘to preserve the original input shape (C × H × W).

In the peanut pod detection task, although the image background is a black conveyor belt, the images not only contain peanut pod targets of various sizes and shapes, but also inevitably include dropped soil particles and pod fragments. The triple attention module enhances the ability to capture fine-grained features, such as the boundaries of peanut pods, by establishing effective interactions between the spatial and channel dimensions. Additionally, the three-branch structure in the module processes the input tensor in parallel, fully utilizing information from different dimensions and compensating for the limitations of traditional convolutional layers in capturing rare features, such as the subtle gaps between peanut pods.

3.2.3. MPDIoU

IoU (Intersection over Union) is a simple function used to calculate localization loss by measuring the overlap between two bounding boxes [35]. In the original YOLOv8 algorithm, the CIoU function is employed to compute the localization loss. The expression for CIoU is given in Equation (11).

In this formulation, and denote the predicted box and the ground-truth box, respectively; represents the Euclidean distance between the centers of the predicted and ground-truth boxes; c indicates the diagonal length of the smallest enclosing region containing both boxes; v and α denote the evaluation parameter and the trade-off factor for aspect ratio, respectively. The detailed formulation is as follows:

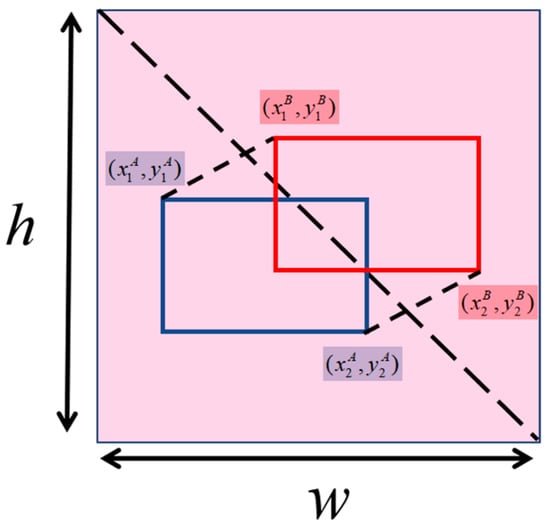

Although CIoU accounts for intersection area, center distance, and aspect ratio, it relies on a different measure of aspect ratio rather than the true differences in width and confidence, which reduces the convergence speed of the model. To address regression issues for both overlapping and non-overlapping bounding boxes while simultaneously considering center distance as well as width and height deviations, this study introduces the MPDIoU loss function [36] as a replacement for the original CIoU. The structural composition is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the MPDIoU loss function.

The MPDIoU loss function minimizes the Euclidean distance between the top-left and bottom-right corners of the predicted and ground-truth boxes, combined with IoU to form a new similarity metric. This approach eliminates the need for complex enclosure calculations, thereby simplifying the computational process to some extent. As a result, the model achieves faster convergence and yields more accurate regression outcomes [37]. The corresponding expressions are provided in Equations (14)–(17).

Here, A and B denote the predicted and ground-truth boxes, respectively; and represent the top-left and bottom-right coordinates of the predicted box A, while and represent the top-left and bottom-right coordinates of the ground-truth box B.

In the peanut pod detection task, due to irregular target boundaries, complex backgrounds, and the possibility of multiple peanut pod targets making contact or overlapping, traditional IoU or CIoU calculations struggle to effectively optimize these complex target boundaries. The MPDIoU loss function, by directly minimizing the distance between the corners of the predicted and ground truth boxes, can more precisely capture these irregular target boundaries. At the same time, it accelerates the model’s convergence and reduces unnecessary computational load.

3.3. Performance Evaluation Metrics

In this study, the following evaluation metrics are used: precision, recall, F1-score, mean average precision at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 (mAP50), and mean average precision across IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 (mAP50-95). Precision is defined as the ratio of true positive predictions to the total number of predictions made by the model, providing a measure of the model’s accuracy in identifying positive samples. Recall, on the other hand, represents the proportion of true positive predictions among all actual positive samples, serving as an indicator of missed detections. The F1-score, which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, offers a balanced evaluation of the model’s performance in handling both positive and negative instances. mAP50 refers to the mean average precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5, which assesses the model’s ability in terms of both object localization and recognition. In contrast, mAP50-95 is the mean of average precision values calculated over a range of IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95, providing insight into the model’s generalization ability across varying matching criteria [38]. The mathematical definitions of these metrics are expressed as follows:

where TP (true positives) represents the number of actual positive samples predicted as positive; FP (false positives) represents the number of actual negative samples predicted as positive; and FN (false negatives) represents the number of actual positive samples predicted as negative. TN (true negatives) represents the number of actual negative samples predicted as negative.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Environment

All experiments in this study were conducted under the same hardware conditions. The training environment was deployed on the Windows 10 operating system, and the entire development process was carried out within the Visual Studio Code 1.95.0 (VS Code) integrated development environment (IDE). The detailed experimental configuration is summarized in Table 1. To ensure consistency and comparability of the experimental results, all algorithms were evaluated and tested under this standardized environment. All input images were uniformly resized to 640 × 640 pixels. The initial learning rate was set to 0.001, and the batch size was fixed at 32.

Table 1.

Experimental Environment Configuration.

4.2. Model Training Results

To evaluate the performance of the BTM-YOLOv8 model, 316 images from the test set were used for validation. As shown in Table 2, the improved BTM-YOLOv8 outperforms the original YOLOv8 model across all metrics. Specifically, it achieves a precision of 98.40%, a recall of 96.20%, an mAP50 of 99.00%, and an F1-score of 97.29%, representing improvements of 3.9%, 2.4%, 1.2%, and 3.14%, respectively, over the baseline network.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison Before and After Model Improvement.

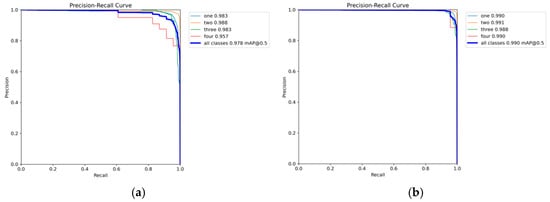

To more realistically reflect model performance—particularly its ability to balance minimizing missed detections (high recall) with suppressing false positives (high precision)—a Precision-Recall (PR) curve was plotted. As illustrated in Figure 8, the original YOLOv8 achieved an mAP@0.5 of 0.978 for the four nut-counting categories, with per-class precision values ranging from 0.957 to 0.988. After optimization, the BTM-YOLOv8 achieved an improved mAP@0.5 of 0.990, with per-class precision values ≥ 0.988. Notably, the precision for the category “four” increased from 0.957 to 0.990, marking a significant improvement of 3.3%. This enhancement demonstrates that the proposed improvements substantially strengthen the model’s capability to capture features of small or partially occluded kernels while also reducing the false positive rate in low-confidence regions. The overall rightward shift in the PR curve further confirms that the improved model maintains higher precision across the full recall range.

Figure 8.

PR curves before and after model improvement. (a) YOLOv8; (b) BTM-YOLO v8.

4.3. Comparative Experiments on Loss Functions

This study further investigates the impact of bounding box regression loss functions on object detection performance through comparative experiments. As shown in Table 3, the baseline model employing inner_CIoU performs well in terms of precision and mAP50; however, its recall remains relatively low, indicating a higher missed detection rate when handling dense targets. In contrast, the SIoU loss function significantly improves recall to 96.00%, but at the cost of reduced precision (94.30%), leading to an increased false positive rate and a lower overall F1-score of 95.14%. Traditional loss functions such as DIoU and GIoU exhibit a more balanced trade-off between precision and recall. Among them, DIoU achieves an F1-score of 94.75%, outperforming GIoU (93.34%), though its mAP50 reaches only 97.40%, leaving room for further optimization. The proposed MPDIoU loss function achieves superior performance across all metrics. Specifically, it attains a precision of 96.40%, improving by 0.6% over inner_CIoU; and a recall of 95.20%, offering a more balanced trade-off compared with SIoU in terms of missed versus false detections. Particularly for the localization accuracy of densely packed peanut kernels, MPDIoU simplifies distance measurement while effectively mitigating the excessive sensitivity of traditional loss functions to center-point distance. This enables bounding box regression to focus more on scale-matching optimization.

Table 3.

Results of Loss Function Comparison.

The experimental results demonstrate that MPDIoU provides a distinct advantage in post-harvest peanut pod detection by simultaneously enhancing detection accuracy and ensuring localization stability.

4.4. Ablation Study

To evaluate the contribution of each improvement in BTM-YOLOv8 to peanut kernel detection performance, ablation experiments were conducted by progressively integrating the proposed modules into the baseline algorithm. The results are summarized in Table 4. The baseline model (ID1) achieved a precision of 94.50% and an mAP50 of 97.80% without any optimization modules. When using the BiFormer backbone alone (ID2), the F1-score increased significantly by 2.3% to 96.45%, demonstrating that its enhanced feature extraction capability plays a critical role in recognizing peanut kernels under complex backgrounds. Incorporating the Triplet Attention module (ID4) improved recall by 2.2% to 96.00%, though precision decreased slightly by 0.4%. This indicates that the attention mechanism effectively strengthens the model’s ability to capture fine-grained targets but may introduce a small amount of noise. The standalone use of the MPDIoU loss function (ID3) increased recall and mAP50 by 1.4% and 0.5%, respectively, validating its optimization effect on bounding box regression. When BiFormer and MPDIoU were combined (ID6), the model achieved an F1-score of 97.35%, an improvement of 3.2% over the baseline, confirming the synergistic optimization between the backbone and the loss function. However, the combination of Triplet Attention and MPDIoU (ID7) led to a decrease in recall. This indicates that, without altering the backbone network and only adding Triplet Attention and MPDIoU, the model may overly focus on certain features during the optimization process, leading to the potential miss detection of some targets. Ultimately, the full integration of all three modules (ID8) yielded the best performance, achieving 98.40% precision and 99.00% mAP50, improvements of 3.9% and 1.2% over the baseline, respectively, with an F1-score of 97.29%. These results demonstrate that the complementary effects of the modules collectively balance detection accuracy and robustness, ensuring high recall while substantially reducing false positives.

Table 4.

Results of Ablation Experiments.

The experimental results fully validate the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed improved design in the ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanut detection task.

4.5. Testing of Peanut Pod Detection Device

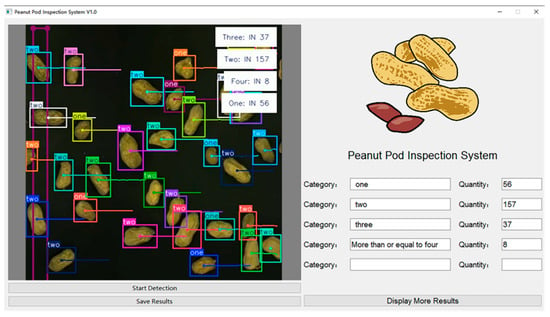

The improved BTM-YOLOv8 was deployed on a custom-made peanut detection device for detecting ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanut pods. To better demonstrate the effectiveness of the device, a graphical user interface (GUI) was developed, which can receive real-time video streams transmitted from the device, perform detection, and automatically count pods with varying kernel numbers. Through this interface, users can simultaneously monitor the process and view the classification results of peanut pods in real time (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

GUI interface of the detection system.

During testing, a randomly selected batch of peanut pods was examined in three repeated trials, and the average machine detection results were compared against manual counting. Model performance was further evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2) and root mean square error (RMSE) to measure goodness-of-fit and prediction accuracy. As shown in Table 5, across 2103 kernels tested, the device achieved the highest accuracy in detecting pods with three kernels, yielding results identical to manual counting. However, discrepancies were observed in the categories of two-kernel and one-kernel pods. The model’s R-squared value is 0.999, and the RMSE value is 12.69, indicating that the BTM-YOLOv8 model can accurately predict the number of kernels with minimal error. However, regression metrics alone are not sufficient to fully assess classification performance, especially in cases of class imbalance.

Table 5.

Comparison of Device Detection and Manual Counting Results.

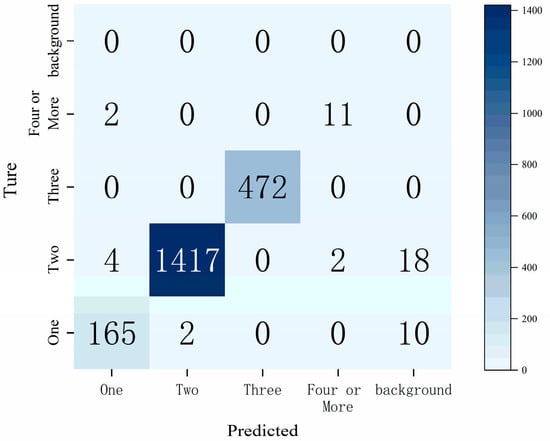

To more comprehensively evaluate the model’s classification performance, we also calculated the accuracy per category and plotted the confusion matrix (Figure 10). From the confusion matrix, it can be observed that although the model’s predictions for the “three kernels” category perfectly match the ground truth, there is still some error in the “one kernel” and “two kernels” categories. In particular, for the “two kernels” category, 24 samples were not accurately identified.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix of detection results for different categories.

Monitoring through the system terminal revealed that when the number of peanut targets below the camera is large and densely distributed, the FPS shows a decreasing trend. In contrast, when the number of targets is smaller, the FPS increases. This phenomenon indicates that as the number of detected targets increases, the computational load per frame also increases, leading to a decrease in FPS. However, the FPS remained stable between 47.53 and 58.22 during this process, indicating that the system is capable of maintaining a certain processing speed.

In summary, although the model still has some prediction errors, it generally meets the requirements for practical use. Based on these data, we believe the device can provide effective detection in most cases. However, performance in certain categories still needs further optimization. In the future, the model’s accuracy can be improved by increasing the training data, enhancing image acquisition conditions, or adjusting model parameters. Additionally, the device’s operational stability and its ability to detect different input sizes are also key factors affecting the detection results. Future research can focus on further optimizing and adjusting these aspects.

4.6. Comparative Experiments with Different Models

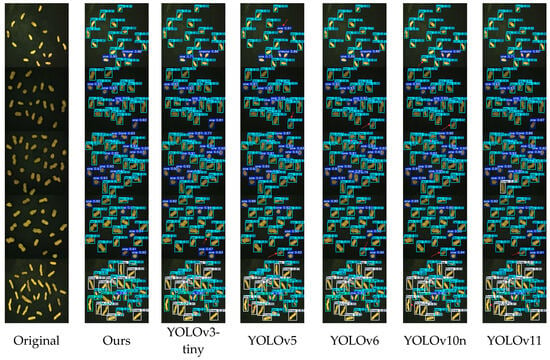

To verify the effectiveness of BTM-YOLOv8 in ‘Quan Hua 557’ detection, this study selected comparison models including YOLOv5, YOLOv6, YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv10, and YOLOv11. A horizontal comparison was conducted under the same dataset, training strategy, and testing environment. All models were trained and tested under identical datasets, training strategies, and experimental environments to ensure fairness. As presented in Table 6, BTM-YOLOv8 outperformed all other models across every metric. In particular, its F1-score of 97.29% was significantly higher than that of competing models, demonstrating an optimal balance between precision and recall. This indicates that the proposed model effectively meets the dual requirements of detection accuracy and recall in practical applications. Among the comparison models, YOLOv5, YOLOv6, and YOLOv9s exhibited relatively balanced performance across different indicators. However, YOLOv6 showed the weakest overall performance, with F1-scores of 91.88%, 87.43%, and 93.04%, respectively. Both YOLOv10n and YOLOv11n achieved high recall values of 93.70%, but their low precision (90.00% and 86.30%, respectively) caused F1-scores to fall below 92%, reflecting frequent false positives in actual target detection. YOLOv3-tiny achieved a precision of 94.60%, second only to the proposed BTM-YOLOv8. Nevertheless, its mAP50 was limited to 94.00%, highlighting deficiencies in localization accuracy. Overall, these comparative experiments strongly confirm that BTM-YOLOv8 offers superior accuracy and stability in peanut pod detection tasks, making it more suitable for real-world deployment than the alternative models.

Table 6.

Results of Comparative Experiments with Different Models.

Additionally, to assess the model’s computational efficiency and real-time potential, we tested the inference speed of all comparison models under the same experimental conditions. As shown in Table 6, the computational complexity of BTM-YOLOv8 (30.5 GFLOPs) is higher than that of lightweight models such as YOLOv11 (6.3 GFLOPs), resulting in a lower FPS. The increase in model complexity is a necessary trade-off for achieving higher performance. However, with a rate of 64.92 FPS, it still exceeds the basic requirement for real-time detection (typically 30 FPS), indicating that the model has real-time processing capability on the current computational platform.

Using all comparison models to perform inference on the test set images, a selection of detection results is shown in Figure 11, where red arrows indicate instances of false or incorrect detections. Analysis of these results reveals that the BTM-YOLOv8 model demonstrates markedly superior performance in accurate target identification and in reducing false positives compared with the other models. This indirectly illustrates that the proposed improvements significantly enhance the model’s ability to capture key features. Consequently, BTM-YOLOv8 proves to be more suitable for deployment in real production environments. In contrast, YOLOv5, YOLOv6, and YOLOv10n exhibited frequent misdetections during the detection process, while YOLOv3-tiny and YOLOv11 also showed a certain degree of false detections, which ultimately reduced their overall accuracy.

Figure 11.

Detection results of selected models.

5. Discussion

The primary uses of peanuts include oil extraction, direct consumption, and animal feed. The size and number of kernels are key factors determining the processing efficiency and end quality of peanuts [39]. Automated and precise sorting of peanut seeds using deep learning technologies not only improves yield and seed quality but also enhances agricultural safety and efficiency, thereby driving agricultural production toward higher quality, efficiency, and stability [40]. Consequently, peanut detection and classification through deep learning hold significant practical value for quality improvement. Moreover, classifying peanuts by kernel number is crucial for evaluating yield potential, economic value, and varietal traits, providing scientific guidance for seed selection and breeding while advancing modernization and intelligentization of agricultural production.

This study proposes an improved BTM-YOLOv8 detection model, enabling the model to capture the detailed features of peanut seeds more accurately. Significant improvements were achieved across multiple key metrics, with precision reaching 98.40%, recall at 96.20%, F1 score at 97.29%, and mAP50 at 99.00%. These results demonstrate that the BTM-YOLOv8 model exhibits excellent recognition ability and robustness in detecting ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanuts. Compared to the original network and other mainstream object detection models (such as YOLOv5, YOLOv6, YOLOv9s, etc.), BTM-YOLOv8 showed superior performance. It not only provides an efficient and accurate solution for peanut pod detection but also lays the technological foundation for seed detection in other agricultural crops.

However, despite the excellent performance in detection accuracy and efficiency achieved in this study, there are still some limitations. Firstly, this study focused on a single peanut variety (only ‘Quan Hua 557’), and all images were captured on a conveyor belt (with a relatively simple background), which may limit the model’s adaptability to other peanut varieties or different environmental conditions. For example, in detecting peanut pods with significant variation in seed size, the model’s performance may be affected, and its application in real-world fields may also be restricted. Therefore, future research could expand the dataset by introducing more diverse peanut varieties and environmental conditions to improve the model’s generalization ability and adaptability.

Furthermore, as this work focuses primarily on peanuts, the generalizability of the model to other crops remains untested. Future studies may extend the system to explore broader applications in seed detection of various agricultural products.

In addition, the ablation experiments in this study revealed a decline in recall when combining Triplet Attention with MPDIoU. Preliminary analysis suggests that this decrease may be due to the model focusing too heavily on certain features during the optimization process, resulting in insufficient attention to other features, which leads to missed detections. However, the exact cause of this phenomenon remains unclear and requires further investigation. To address this issue, future work will focus on conducting more detailed ablation experiments, combining quantitative class-specific metrics to thoroughly analyze the performance bottleneck of this configuration, and exploring ways to optimize the model’s feature learning process under this configuration.

Looking ahead, as the demand for intelligent and automated technologies in agriculture continues to rise, the BTM-YOLOv8-based detection system could be integrated with other agricultural machinery to form a comprehensive automated seed screening and sorting platform. Future research could also explore integrating multimodal sensing (e.g., infrared imaging, laser scanning) with visual detection to further improve accuracy and stability. Additionally, advancements in hardware call for optimization of computational efficiency. for example, by employing model quantization and pruning techniques [41] to reduce computational costs and enable efficient deployment on edge devices. Such efforts would further accelerate the widespread application of this technology in agricultural production.

In summary, the BTM-YOLOv8-based peanut detection system proposed in this study highlights the potential of deep learning in agriculture. It not only provides a reliable technical approach for peanut seed quality inspection but also introduces new ideas for achieving efficiency and intelligence in agricultural production and crop processing.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes a peanut seed count detection model based on the improved BTM-YOLOv8 to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of detecting and counting peanut pods with different numbers of seeds. The model was integrated into a self-designed conveyor belt peanut pod detection device, achieving high-precision and high-efficiency rapid detection of ‘Quan Hua 557’ peanut pods. The main improvements in BTM-YOLOv8 include: First, the introduction of the BiFormer structure with Bi-Level Routing Attention (BRA) in the backbone network allocates varying levels of attention to different positions or features, capturing long-range dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to extract features of small and densely distributed peanuts and reducing false detections. Second, the integration of the Triple Attention mechanism allows for cross-dimensional interactions, strengthening the modeling of dependencies between channel and spatial dimensions. Finally, the MPDIoU loss function simplifies distance measurement, enabling bounding box regression to focus more effectively on scale-matching optimization. With these improvements, the enhanced BTM-YOLOv8 achieves a precision of 98.40%, recall of 96.20%, F1-score of 97.29%, and mAP50 of 99.00%, representing improvements of 3.9%, 2.4%, 1.2%, and 3.14%, respectively, compared to the original network. Although the computational complexity of BTM-YOLOv8 has increased, the FPS during device operation remained stable between 47.53 and 58.22, which is still above the basic requirement for real-time detection. Testing on the conveyor-based peanut pod detection device further confirmed its high accuracy. In conclusion, the proposed BTM-YOLOv8-based peanut kernel visual detection system demonstrates the significant potential of deep learning in agricultural seed quality inspection and fine-grained sorting, providing new solutions and insights for the intelligent and automated development of agriculture. Looking ahead, further optimization and expansion of this system are expected to promote its broader application in agricultural production, thereby advancing the industry toward higher quality, greater efficiency, and enhanced stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and P.C.; methodology, Y.C., P.C. and T.W.; software, P.C.; validation, Y.C., P.C. and T.W.; formal analysis, Y.C.; investigation, Y.C., P.C. and T.W.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C., P.C. and T.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.C., P.C., T.W. and J.Z.; visualization, T.W.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following grant: Key Technology for Digitization of Characteristic Agricultural Industries in Fujian Province (XTCXGC2021015); Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences Research Project (MINCAIZHI(2024)900).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Since the project presented in this research has not yet concluded, the experimental data will not be disclosed for the time being. Should readers require any supporting information, they may contact the corresponding author via email.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chen, T.; Yang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, B.; Zeng, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Qi, H.; Lan, Y.; et al. Early detection of bacterial wilt in peanut plants through leaf-level hyperspectral and unmanned aerial vehicle data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, D.; Wu, J.; Xue, X.; Hu, M.; Zhi, C.; Pandey, M.K.; Liu, N.; Huang, L.; Bai, D.; Yan, L.; et al. Red fluorescence protein (DsRed2) promotes the screening efficiency in peanut genetic transformation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1123644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Zhan, C.; Ma, J.; Chao, Z.; Liu, Y. Lightweight detection model for safe wear at worksites using GPD-YOLOv8 algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, M. Detection of safety helmet and mask wearing using improved YOLOv5s. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, T.J.; Thinakaran, K. Detection of Crime Scene Objects using Deep Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT), Bengaluru, India, 5–7 January 2023; pp. 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Shan, L.; Yuan, C.; Du, S. Advancing cardiac diagnostics: Exceptional accuracy in abnormal ECG signal classification with cascading deep learning and explainability analysis. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 165, 112056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Rehman, A.; Saba, T.; Nadeem, L.; Bahaj, S.A.O. Recent Advancements and Future Prospects in Active Deep Learning for Medical Image Segmentation and Classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 113623–113652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Liu, Z.; Lan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, A.; Li, J. YOLO-FSE: An Improved Target Detection Algorithm for Vehicles in Autonomous Driving. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 13922–13933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.I.; Tan, S.Y.; Abdullah, A. Vision-Based Autonomous Vehicle Systems Based on Deep Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Frøseth, G.T.; Rønnquist, A.; Kong, X.; Deng, L. A visual inspection and diagnosis system for bridge rivets based on a convolutional neural network. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2024, 39, 3786–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, I.D.; Tzani, M.A. Industrial object and defect recognition utilizing multilevel feature extraction from industrial scenes with Deep Learning approach. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2022, 14, 10263–10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Chang, P.; Huang, Y.; Zhong, F.; Jia, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhong, H.; Liu, S. CES-YOLOv8: Strawberry Maturity Detection Based on the Improved YOLOv8. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megalingam, R.K.; Manoharan, S.K.; Maruthababu, R.B. Integrated fuzzy and deep learning model for identification of coconut maturity without human intervention. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 6133–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, H.; Deng, Y.; Cai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Z.; Ruan, M.; Chen, J.; et al. YOLOv8-LSW: A Lightweight Bitter Melon Leaf Disease Detection Model. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, J.; Wu, S. Multiple disease detection method for greenhouse-cultivated strawberry based on multiscale feature fusion Faster R_CNN. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 199, 107176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wei, Z.; Chen, K. A method for segmentation and localization of tomato lateral pruning points in complex environments based on improved YOLOV5. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 229, 109731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moallem, P.; Serajoddin, A.; Pourghassem, H. Computer vision-based apple grading for golden delicious apples based on surface features. Inf. Process. Agric. 2017, 4, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Niu, B.; Peng, F.; Li, G.; Yang, Z.; Wu, J. Classification of Peanut Images Based on Multi-features and SVM. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, M.A.; Yamamoto, K.; Miyamoto, M.; Kondo, N.; Grift, T. Machine vision based soybean quality evaluation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 140, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgun, M.; Onarcan, A.O.; Özkan, K.; Işik, Ş.; Sezer, O.; Özgişi, K.; Ayter, N.G.; Başçiftçi, Z.B.; Ardiç, M.; Koyuncu, O. Wheat grain classification by using dense SIFT features with SVM classifier. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 122, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklu, M.; Cinar, I.; Taspinar, Y.S. Classification of rice varieties with deep learning methods. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ni, J.; Gao, J.; Han, Z.; Luan, T. A novel method for peanut variety identification and classification by Improved VGG16. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, H.; Dong, H.; Xia, L.; Darwish, I.A.; Guo, Y.; Sun, X. Optimizing aflatoxin B1 detection in peanut kernels through deep modular combination optimization algorithm: A deep learning approach to quality evaluation of postharvest nuts. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 220, 113293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Niu, D.; Hou, C.; Yang, L. Improved Peanut Quality Detection Method of YOLOv8n. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2024, 60, 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Li, J. LGP-YOLO: An efficient convolutional neural network for surface defect detection of light guide plate. Complex Intell. Syst. 2023, 10, 2083–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buslaev, A.; Iglovikov, V.I.; Khvedchenya, E.; Parinov, A.; Druzhinin, M.; Kalinin, A.A. Albumentations: Fast and flexible image augmentations. Information 2020, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohan, M.; Sai Ram, T.; Rami Reddy, C.V. A Review on YOLOv8 and Its Advancements. In Algorithms for Intelligent Systems; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.M.; Rahimi, A. SH17: A dataset for human safety and personal protective equipment detection in manufacturing industry. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2025, 6, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Xu, T.; Shi, C.; Li, S.; Xie, Q.; Rong, L. Research on pig behavior recognition method based on CBCW-YOLO v8. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, R.-Y.; Cai, W. Fracture detection in pediatric wrist trauma X-ray images using YOLOv8 algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Ke, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lau, R. BiFormer: Vision Transformer with Bi-Level Routing Attention. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 10323–10333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Chen, J.; Fu, L.; Zhong, J.; Qiaoi, W.; Luo, J.; Li, J.; Li, N. Real-time citrus variety detection in orchards based on complex scenarios of improved YOLOv7. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1381694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Saffar, M.; Vaswani, A.; Grangier, D. Efficient content-based sparse attention with routing transformers. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2021, 9, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, D.; Nalamada, T.; Arasanipalai, A.U.; Hou, Q. Rotate to Attend: Convolutional Triplet Attention Module. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Virtual, 5–9 January 2021; pp. 3138–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhan, J.; Li, H. A multivariate intersection over union of SiamRPN network for visual tracking. Vis. Comput. 2021, 38, 2739–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 12993–13000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Gao, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Wu, Y.; et al. Pest recognition in microstates state: An improvement of YOLOv7 based on Spatial and Channel Reconstruction Convolution for feature redundancy and vision transformer with Bi-Level Routing Attention. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1327237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia Contributors. Precision and Recall. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Precision_and_recall (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Gebremeskel, G.B.; Mengistie, D.G. Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) seed defect classification using ensemble deep learning techniques. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Zare, A.; Rowland, D.L.; Tillman, B.L.; Yoon, S.-C. Peanut maturity classification using hyperspectral imagery. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 188, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osornio-Rios, R.A.; Cueva-Perez, I.; Alvarado-Hernandez, A.I.; Dunai, L.; Zamudio-Ramirez, I.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A. FPGA-Microprocessor based Sensor for faults detection in induction motors using time-frequency and machine learning methods. Sensors 2024, 24, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.