Transformer-Based Multi-Task Segmentation Framework for Dead Broiler Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

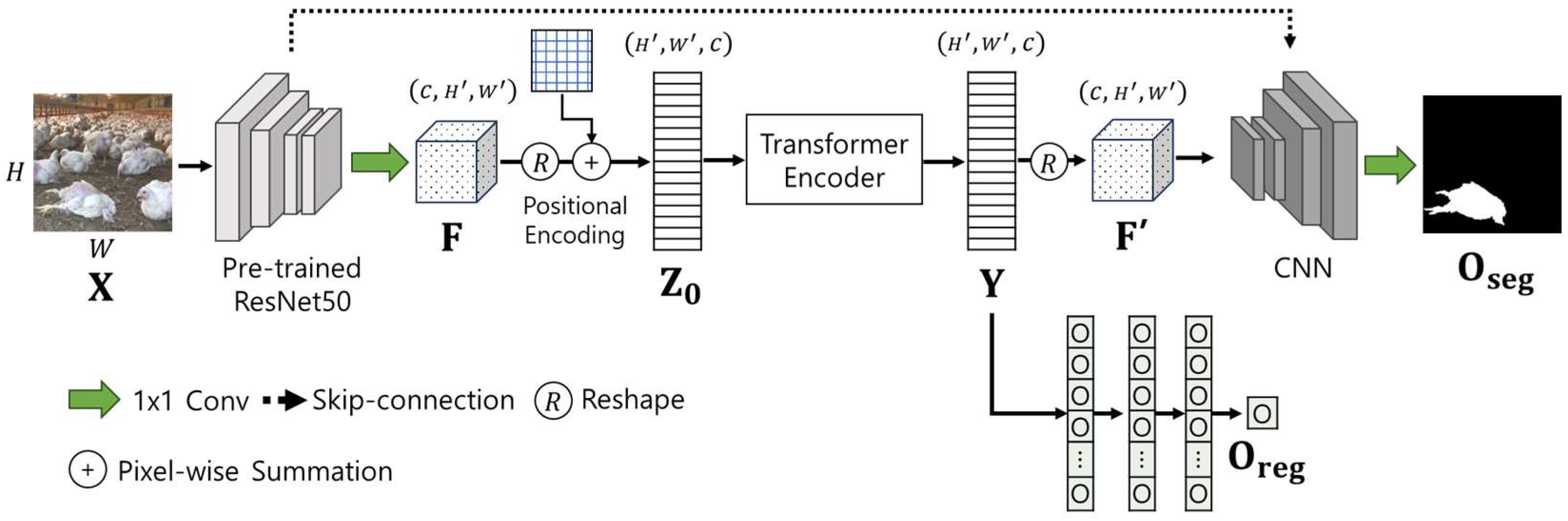

- We propose a transformer-based architecture that jointly performs dead broiler segmentation and auxiliary count regression. The regression branch is specifically designed to reinforce segmentation by encouraging consistent object-level reasoning across diverse scenes.

- By integrating a transformer block into the encoding stage, the model captures long-range spatial relationships that are crucial when live and dead broilers appear in close proximity, or exhibit visually similar textures. This improves the ability to isolate dead individuals, even under crowded conditions.

- The regression of dead broiler counts provides a structured supervisory feature that redirects the feature representation toward regions relevant to mortality, allowing the segmentation network to avoid misclassifying live animals, and to focus on spatially coherent dead broiler regions.

2. Related Works

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Collection and Description

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Feature Encoding

3.2.2. Transformer Module

3.2.3. Segmentation Module

3.2.4. Regression Module

3.2.5. Loss Function

3.2.6. Implementation Detail

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Performance Comparison

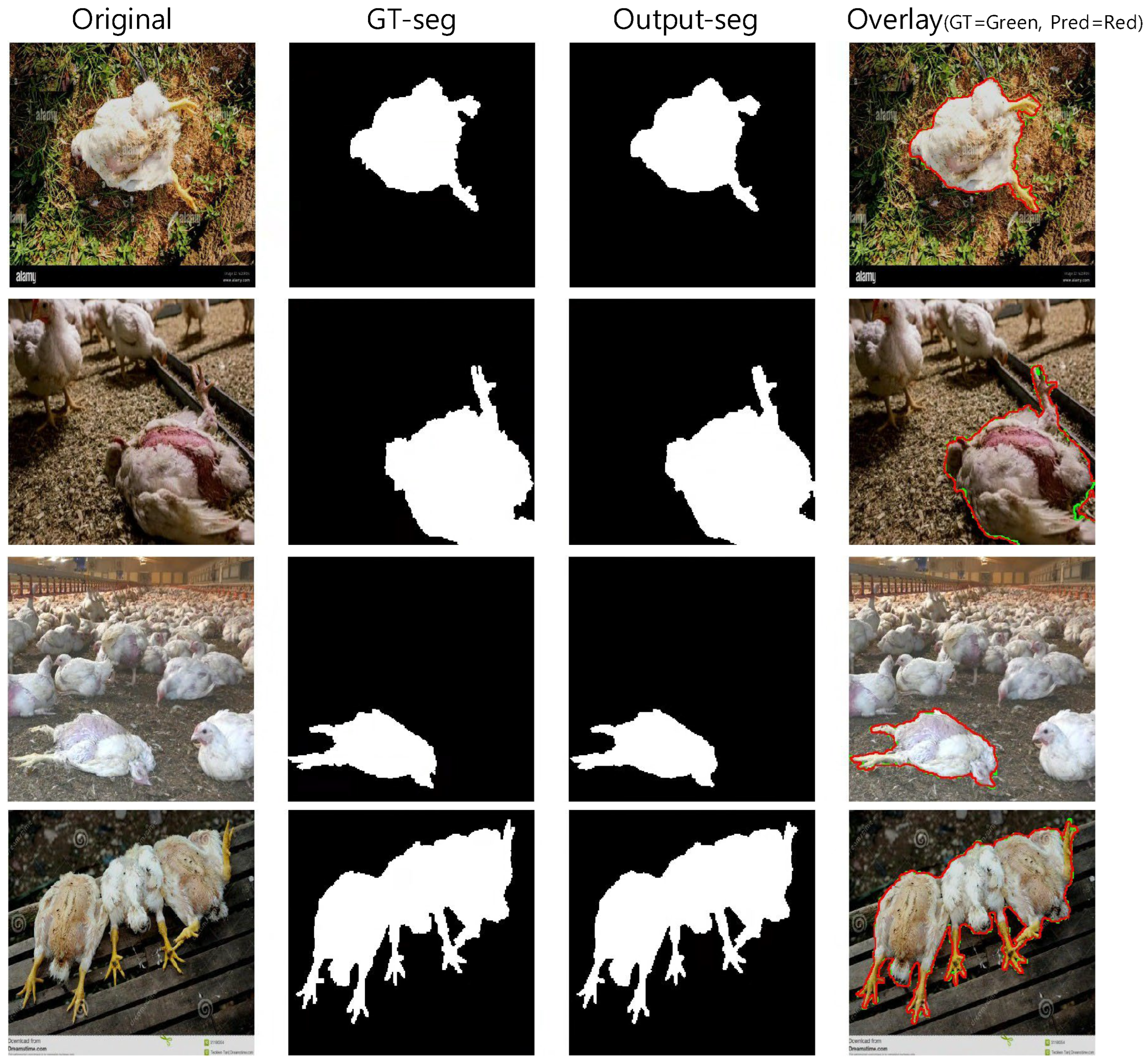

4.3. Visualization Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.-W.; Chen, C.-H.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Hsieh, K.-W.; Lin, H.-T. Identifying Images of Dead Chickens with a Chicken Removal System Integrated with a Deep Learning Algorithm. Sensors 2021, 21, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, A.; Cen, H.; Wan, L.; Mehmood, K.; He, Y. Nutrient Status Diagnosis of Infield Oilseed Rape via Deep Learning-Enabled Dynamic Model. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 4379–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, G.-S.; Oh, K. Dead Broiler Detection and Segmentation Using Transformer-Based Dual Stream Network. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdanan Mehdizadeh, S.; Neves, D.P.; Tscharke, M.; Nääs, I.A.; Banhazi, T.M. Image Analysis Method to Evaluate Beak and Head Motion of Broiler Chickens During Feeding. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 114, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.F.; Miyamoto, B.C.B.; Maia, G.D.N.; Sales, G.T.; Magalhães, M.M.; Gates, R.S. Machine Vision to Identify Broiler Breeder Behavior. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 99, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Recent Advances in Wearable Sensors for Animal Health Management. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2017, 12, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Zhang, T. Detection of Sick Broilers by Digital Image Processing and Deep Learning. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 179, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Fang, P.; Duan, E.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. A Dead Broiler Inspection System for Large-Scale Breeding Farms Based on Deep Learning. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bist, R.B.; Yang, X.; Subedi, S.; Chai, L. Mislaying Behavior Detection in Cage-Free Hens with Deep Learning Technologies. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, M.B.R.; Hasan, M.A.; Salam, M.A.; Ali, M.A. Digital Image Analysis to Estimate the Live Weight of Broiler. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2010, 72, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, A.K.; Lisouski, P.; Ahrendt, P. Weight Prediction of Broiler Chickens Using 3D Computer Vision. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 123, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amraei, S.; Mehdizadeh, S.A.; Nääs, I.D.A. Development of a Transfer Function for Weight Prediction of Live Broiler Chicken Using Machine Vision. Eng. Agric. 2018, 38, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.-W.; Yu, Z.-W.; Kang, R.; Yousaf, K.; Qi, C.; Chen, K.-J.; Huang, Y.-P. An Experimental Study of Stunned State Detection for Broiler Chickens Using an Improved Convolution Neural Network Algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, M.A.; Baki, S.R.M.S.; Tahir, N.M.; Rahman, R.A. An Approach of Halal Poultry Meat Comparison Based on Mean-Shift Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Systems, Process Control (ICSPC), Malacca, Malaysia, 13–15 December 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, A.S.; Marasigan, R.I., Jr.; Nicolas- Mindoro, J.G.; Casuat, C.D. An Image Processing Approach of Multiple Eggs’ Quality Inspection. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2019, 8, 2794–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S.; Tuteja, S.K.; Huang, S.T.; Kelton, D. Recent Advancement in Biosensors Technology for Animal and Livestock Health Management. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 98, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syauqi, M.N.; Zaffrie, M.M.A.; Hasnul, H.I. Broiler Industry in Malaysia. Available online: http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/files/ap_policy/532/532_1.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2018).

- Okinda, C.; Lu, M.; Liu, L.; Nyalala, I.; Muneri, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Shen, M. A Machine Vision System for Early Detection and Prediction of Sick Birds: A Broiler Chicken Model. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 188, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Lapedriza, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Learning Deep Features for Discriminative Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 2921–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany Proceedings, Part III. ; Volume 18, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16 × 16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, G.S.; Oh, K. Learning Spatial Configuration Feature for Landmark Localization in Hand X-rays. Electronics 2023, 12, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Eijk, J.A.J.; Guzhva, O.; Voss, A.; Möller, M.; Giersberg, M.F.; Jacobs, L.; de Jong, I.C. Seeing Is Caring—Automated Assessment of Resource Use of Broilers with Computer Vision Techniques. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 945534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Fang, C.; Zheng, H.; Ma, C.; Wu, Z. A Detection Method for Dead Caged Hens Based on Improved YOLOv7. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W. Detection System of Dead and Sick Chickens in Large Scale Farms Based on Artificial Intelligence. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 6117–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y. Detection of Sick Laying Hens by Infrared Thermal Imaging and Deep Learning. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2025, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massari, J.M.; de Moura, D.J.; de Alencar Nääs, I.; Pereira, D.F.; Branco, T. Computer-Vision-Based Indexes for Analyzing Broiler Response to Rearing Environment: A Proof of Concept. Animals 2022, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, B. Dead Chickens Dataset. Available online: https://universe.roboflow.com/bruce-wayne-wja03/dead-chikens (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2016, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, A.; Culurciello, E. LinkNet: Exploiting Encoder Representations for Efficient Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP), St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 10–13 December 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Metrics (Std) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOU | Precision | Recall | F-Measure | |

| U-Net | 82.99 (0.77) | 87.86 (0.76) | 88.80 (0.75) | 88.32 (1.11) |

| FCN | 82.34 (1.64) | 82.74 (0.61) | 91.49 (0.68) | 86.89 (0.77) |

| LinkNet | 82.00 (1.71) | 82.18 (0.55) | 88.99 (1.52) | 85.17 (0.81) |

| DeepLabV3 | 83.92 (0.56) | 91.28 (0.87) | 89.79 (0.97) | 90.53 (0.98) |

| Dual-StreamNet | 84.79 (1.59) | 89.13 (1.19) | 94.29 (0.57) | 91.64 (1.27) |

| Proposed method | 87.39 (1.15) | 94.27 (0.87) | 92.84 (1.00) | 93.20 (1.47) |

| Method | Metrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOU | Precision | Recall | F-Measure | |

| Proposed method without regression block | 86.88 (1.36) | 92.11 (1.04) | 93.42 (0.58) | 92.76 (1.19) |

| Proposed method | 87.39 (1.15) | 94.27 (0.87) | 92.84 (1.00) | 93.20 (1.47) |

| Backbone | Metrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOU | Precision | Recall | F-Measure | |

| ResNet18 | 86.82 (0.55) | 89.23 (0.77) | 94.43 (1.06) | 91.76 (1.33) |

| ResNet34 | 87.04 (1.32) | 91.58 (0.79) | 93.58 (1.06) | 92.57 (0.98) |

| ResNet50 | 87.39 (1.15) | 94.27 (0.87) | 92.84 (1.00) | 93.20 (1.47) |

| ResNet101 | 87.58 (1.41) | 92.60 (0.86) | 93.60 (1.53) | 93.07 (1.69) |

| Number of Attention Heads | Metrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOU | Precision | Recall | F-Measure | |

| 2 | 86.99 (0.51) | 93.32 (0.77) | 92.18 (1.16) | 92.75 (1.17) |

| 4 | 87.12 (1.15) | 93.17 (0.87) | 91.14 (1.00) | 92.23 (1.47) |

| 8 | 87.39 (1.15) | 94.27 (1.25) | 92.84 (1.10) | 93.54 (1.46) |

| 10 | 87.18 (1.41) | 91.90 (1.06) | 93.90 (0.53) | 92.89 (0.93) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ham, G.-S.; Oh, K. Transformer-Based Multi-Task Segmentation Framework for Dead Broiler Identification. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010419

Ham G-S, Oh K. Transformer-Based Multi-Task Segmentation Framework for Dead Broiler Identification. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):419. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010419

Chicago/Turabian StyleHam, Gyu-Sung, and Kanghan Oh. 2026. "Transformer-Based Multi-Task Segmentation Framework for Dead Broiler Identification" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010419

APA StyleHam, G.-S., & Oh, K. (2026). Transformer-Based Multi-Task Segmentation Framework for Dead Broiler Identification. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010419