Abstract

Facial expression recognition (FER) is a fundamental component of Affective Computing and is gaining increasing relevance in mental health applications. This study presents an approach for facial expression recognition using feature extraction and machine learning techniques. Starting from a publicly available dataset, a manual cleaning and relabeling process led to the creation of a refined dataset of 35,625 facial images grouped into four emotional macroclasses. Features were extracted using the SqueezeNet and Inception v3 embedders and classified using various algorithms. The experimental results show that Inception v3 consistently outperforms SqueezeNet and that feature normalization improves classification stability and robustness. The results highlight the importance of data quality and preprocessing in applied FER systems.

1. Introduction

The wide adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is now well established in several fields, including mental health. The integration of such tools presents both several opportunities and inherent challenges, making a thorough understanding of how they work imperative. This is crucial to ensure their ethical and correct use, preserving the central role of mental health professionals and, in particular, ensuring the protection of patients’ privacy.

In a clinical setting, facial emotion recognition plays a crucial role. This field of research, part of Affective Computing, focuses on the analysis of facial expressions (using images and video) to interpret human emotional states. Affective Computing was defined by Picard as “computing that relates to, arises from, or deliberately influences emotions” [1] to create a computer system that perceives, recognizes, and understands human emotions, resulting in intelligent and natural responses useful for better human–computer interaction [2].

To understand human emotions, the analysis of facial expressions is fundamental, a process that relies on the detection of the positions of facial landmarks (e.g., the tip of the nose, eyebrows) and, in videos, their variations to identify the contractions of a muscle group [3].

However, emotion recognition through facial expressions is often influenced by factors such as occlusions, pose variations, lighting, and low image quality. To address these issues, it is important to consider facial muscle movements, which represent the main mechanism underlying emotional expressions. Some muscle movements are in fact specific and mutually exclusive between different emotions, while certain facial regions, although in the minority, provide discriminating information even in the presence of occlusions [4]. In this context, models that exploit the relationships between muscle movements can improve the performance of facial expression recognition (FER). An example is the Muscle Movement-Aware Transformer (MMATrans), which uses discriminative feature generation (DFG) and muscle relationship mining (MRM). The DFG module produces robust representations, reducing the impact of any labelling errors, while the MRM module leverages semantic relationships between facial muscle movements to improve FER accuracy. By removing redundant information, the model can focus on minority but critical facial regions, while reducing computational complexity and achieving superior results compared with several approaches in the literature [4].

Head position is often studied using infrared images, which are often degraded or ambiguous. To address this, Liu et al. (2021) [5] propose a nonuniform Gaussian label distribution learning network (NGDNet), coupled with a multi-label Gaussian-like distribution that reduces the effects of low-quality IR images. This method proves to be robust and effective, achieving an accuracy of 77.39% on the dataset created by the authors (IRHPE dataset) and 99.08% and 87.41% on two other public datasets, proving to be a state-of-the-art model [5].

Another key feature is facial symmetry, which allows us to predict the characteristics of the other side of the face even when it is occluded. Liu et al. (2024) [6] propose a method composed of Context-Aware Local Feature Learning (CALL) and Adaptive Feature Relationship Induction (AFRI). CALL detects local features, allowing the model to understand symmetrical and harmonious facial features. AFRI applies a Transformer to capture global patterns of faces. The model appears robust and effective in facial expression recognition, achieving accuracies of 89% and 95% on two distinct datasets [6].

FER analysis, conducted by Artificial Intelligence algorithms, can be particularly useful for mental health professionals, especially during online sessions. Indeed, the real-time detection of a patient’s emotions can support the monitoring of his or her emotional state, decision making processes for diagnosis, and, more generally, the work of the psychologist. Moreover, Affective Computing has been extended to the study of several psychiatric pathologies, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, bipolar disorder, and PTSD, offering an objective identification and assessment of emotions, complementary to traditional diagnostic tools (characterized by greater subjectivity) and promising for the screening and evaluation of therapeutic efficacy [2].

An algorithm’s primary task in this context is to attribute meaning to non-verbal signals using pre-labelled and supervised datasets. A central aspect of our work is the pivotal role assigned to the psychologist, who analyzed an open-source dataset and then re-labelled it based on his own expertise. This process allowed the creation of a new dataset, to overcome the uncritical automatism of many Al systems, promoting a model in which technology acts as an objective amplifier of the practitioner’s clinical sensitivity.

Based on the foregoing discussion, this study introduces a method aimed at analyzing emotions by means of facial expressions using Deep Learning. The implementation of this approach was conducted through the Orange software, facilitating a critical comparison between two distinct datasets: the Kaggle dataset, widely accessible as an open-source resource, and a new dataset reworked by our research group. The latter was created in response to the detection of misclassifications in the original dataset, which included errors in emotion labelling and the presence of irrelevant images (e.g., blank or textual images instead of faces). Specifically, our study focuses on the identification and classification of the seven basic emotions: anger, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, disgust, and neutrality.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 offers a review of the most recent scientific literature concerning emotion recognition. Section 3 describes in detail the methodology employed for the labelling of facial expressions and the algorithmic analysis conducted on the Orange platform. Section 4 presents an evaluation of the results in terms of precision and recall for the dataset analyzed by our team. Finally, Section 5 outlines future directions of research in the field of emotion recognition.

2. Related Work

Facial expression recognition (FER) systems include several approaches and technologies that are part of Affective Computing (AC), a field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) [7]. Among these technologies we have conventional approaches, based on hand-created features, Deep Learning (DL)-based approaches, based on features learned from data [8], and more recent attention- and Transformer-based architectures.

Our work will involve the analysis of images, from a large dataset (black and white), relating to the primary emotions, first described by Ekman (1969), namely, surprise, sadness, happiness, fear, disgust, and anger [9], to which we have also added the “neutral” class. Over the years, the technologies used for the recognition and emotional analysis of faces have gradually improved: between the 1960s and the 1990s the focus was on the development of algorithms based on facial features such as the mouth, nose and, eyes [10], with Eigenfaces techniques and algorithms such as Elastic Bunch Graph Matching (EBGM) and the Active Appearance Model (AAM) [11], while since the 2000s, machine learning models (e.g., Hidden Markov Models), Deep Learning models, and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have taken hold [12,13,14].

The FER system involves data acquisition, preprocessing, face detection, feature extraction, and classification algorithms [10,13,14]. Among the algorithms used in face detection we have the Viola–Jones algorithm [15], Haar’s cascade classifier [16], and Adaboost Contour Points [17]. Meanwhile, to extract features from an identified face, commonly used algorithms are Local Binary Patterns (LBPs), Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), and Active Shape Models (ASMs) [8]. In contrast, the extraction of facial features to classify emotional states is achieved by means of traditional ML techniques, such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) [18], Random Forest (RF) [19], and Dynamic Bayesian Network (DBN) [20].

As suggested by a review by Adyapady & Annapp (2023) [21], several ML techniques for emotion classification have been proposed in the literature, such as the work of Ghimire et al. [22] who, building upon the effectiveness of Local Binary Pattern (LBP) as a local texture descriptor for facial image representation [23], integrated it with the geometric descriptor Normalized Central Moments (NCMs). This combined feature set (NCM + LBP) was then fed into a Support Vector Machine (SVM) for classification, demonstrating that feature descriptors from specific local regions are better than global representations. Instead, Zhong et al. [24], in addition to using LBP and its uniform variant to extract features, also employed two-stage Multi-Task Sparse Learning (MTSL) to analyze both general and specific information related to different facial expressions. Although based on the LBP technique, Liong et al. [25] took a slightly different approach to encoding facial expressions, as they synthesize LBP features from three orthogonal planes (LBP-TOP) with the Bi-Weighted Oriented Optical Flow (Bi-WOOF) feature extractor. Another strategy reported in the review [21] is the extraction of features from the face region of interest (ROI) using Gabor filters and, subsequently, selecting the most relevant features using Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Other work investigated by the review under consideration [21] continues in this vein, aimed at detecting even minimal changes in ROI. Two works are interesting in this sense: Guo et al. [26] proposed Extended Local Binary Patterns on Three Orthogonal Planes (ELBPTOP) by taking into account the radial and angular differences in a local patch, thus integrating the differences between a pixel and its neighbours (LBPTOP). Likewise, Rashmi and Annappa [27] developed a technique that combines geometric and texture features, employing the Delaunay triangulation (DT) and Voronoi Diagram (VD) approach. This combination is then sent to the DL classifier to categorize the micro-expressions.

Although ML techniques are very valid and popular, several Deep Learning (DL) architectures have been proposed in recent years to improve the performance of facial expression recognition (FER). As suggested by the analyzed review [21], Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) are mainly used, which learn discriminative patterns when fed with extracted features (e.g., via Extracted Scale-Invariant Feature Transform), and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in combination with image processing techniques to extract specific features of facial expressions.

Other uses of CNNs are based on spatiotemporal characteristics. For example, Kim et al. [28] trained a short-term memory (LSTM), generating a discriminative spatiotemporal representation of facial expressions. Zhang et al. [29] used the bidirectional part-based hierarchical Recurrent Neural Network (PHRNN) and multi-signal CNN (MSCNN) to extract dynamic and morphological variations in facial expressions. Finally, Sun et al. [30] extracted both the spatial characteristics from a grey-level image and the optical flux characteristics from the X and Y components of a neutral and an emotional face; subsequently they combined these different features using the multi-channel deep space–time fusion (MDSTFN) neural network to analyze facial expressions.

Despite the progress made by DL, recognizing facial expressions in unconstrained contexts involves many challenges, such as database variations in ecological contexts, cross-cultural problems, computational complexity, overfitting, and poor data samples [21]. To address these challenges, different methods have been tried, such as combining a CNN with Bag-of-Visual-Words (BOVW) handcrafted features architectures, in order to predict an emotional label [31]. Feature Decomposition and Reconstruction Learning (FDRL) is suitable for modelling expression similarities, characterizing specific variations and reconstructing characteristics [32]. In addition, equally relevant are the Identity-Free Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (IF-GAN) [33] and emotion-rich feature learning network (CEFLNet) [34], respectively, useful for reducing intersubjective variations due to attributes that give a specific identity to a specific face [33] and for identifying dynamic facial expressions [34].

Concerning the difficulties related to ethnic differences, the works of Xie et al. [35] and Li and Deng [36] stand out by proposing, each, a convolutional multi-path attentional deep neural network (DAM-CNN), and the Deep Locality-Preserving CNN (DLP-CNN) together with Loss Locality Preserving (LP). Finally, in order to overcome the overfitting problem, Sun and Xia [37] proposed the AlexNet [38] and GoogleNet [39] architectures to improve the accuracy of the CNN architecture by augmenting the data through an “artificial face”. Shao and Qian [40] also devoted themselves to solving the same limitation, proposing three new CNN architectures that ultimately overcame the high computational complexity and the scarcity of training samples.

Recent studies point to other methodologies employed in FER, such as a modified AlexNet architecture integrating Gabor and LBP, also introducing depthwise-separable convolution layers (Safarov et al., 2025 [41]). In their study, the authors conclude that the proposed methodology outperforms previously used methodologies, including RS-exception, Custom Lightweight CNN-based Model (CLCM), and Lightweight Facial Network with Spatial Bias, in terms of accuracy, reaching 98.10% for the FER2013 dataset and 93.34% for the RAF-DB dataset [41].

Other authors emphasize the importance of the extracted facial features employed in FER; specifically, Shiwei Li et al. (2025) [42] propose a fine-grained human facial key feature extraction and fusion method compared with the face recognition models usually employed, which instead focus on the extraction of global features or representations of local features of faces. The authors, for emotion recognition, employ a two-branched convolutional neural network (CNN) to merge global and local features, allowing the model to capture all the characteristics involved in facial emotion changes during training. Their study demonstrates that the approach they propose improves and exceeds the accuracy of emotion recognition compared with existing models [42].

Still concerning facial features, Jaehyun So et al. (2025) [43] designed a Network for utilizing Keypoint Features (NKF). These features are extracted from significant facial regions within the combined feature maps of a dorsal network and a facial alignment network. This approach allows for the more effective and comprehensive use of detailed information from specific facial regions, thus overcoming the limitations of methods that rely solely on reference point coordinates for image alignment or the holistic interpretation of feature maps. The NKF proposed by the authors outperforms several state-of-the-art methods [43].

To address frequent problems in FER, specifically the issue of assigning an emotional label to a certain facial expression (label ambiguity), together with the numerical disparity of images present in a certain emotional class compared with another (class imbalance), JunGyu Lee et al. (2025) [44] proposed a new framework, the Navigating Label Ambiguity (NLA), which addresses label ambiguity to mitigate both noise and class imbalance in FER. The authors demonstrate that NLA, compared with other pre-trained methods for FER, has a higher overall and average accuracy on different datasets used for FER [44].

In recent years, head position estimation (HPE) has acquired a central role in areas such as image processing [45], human–machine interaction [46], and facial landmark analysis [47]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have so far been the primary tool for HPE, achieving competitive results [48], but CNNs show limitations in scenarios characterized by significant occlusions, unfavourable illumination, or extreme orientations.

Recently, several studies have explored the use of Transformers as an alternative to CNNs, due to their ability to model long-range, high-level relationships between image patches. Liu et al. (2023) [49] propose the TokenHPE model, which combines visual tokens and face orientation tokens to learn the relationships between different face parts and face orientation features in baseline regions. TokenHPE achieves a state-of-the-art performance, successfully addressing challenges arising from poor lighting, occlusions, and extreme orientations, highlighting the importance of relationships between facial features and facial orientation, which have been often overlooked in previous approaches [49].

Narayan et al. (2025) [50] propose FaceXFormer, an end-to-end unified Transformer model capable of simultaneously tackling multiple facial analysis tasks, including facial landmark detection, head pose estimation, and expression recognition. The model integrates a lightweight decoder, equipped with a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism, which improves the learning of robust and generalizable facial representations. The experimental results show an excellent state-of-the-art performance in several tasks, maintaining real-time processing capabilities at 33.21 FPS [50]. Finally, Wu et al. (2025) [51] propose an approach for estimating 3D human poses from 2D sequences in monocular videos, based on a Transformer–LSTM Encoder and a Body Joint Transformer Encoder. The model is designed to capture both the spatiotemporal characteristics and structural information of joints, integrating the characteristics of individual body parts and considering kinematic coordination between joints. This combination allows for the more accurate estimation of 3D poses and better generalization ability. The experimental results demonstrate that the method outperforms previous approaches even in scenarios with limited supervision, highlighting the flexibility of the model and its applicability to different body movements and configurations [51].

In conclusion, several scientific articles can be found in the literature regarding the development of methodologies used in face and emotion recognition. But precisely because it is a rapidly growing field, it deserves further research and development of algorithms that improve the recognition of facial emotions.

3. Materials and Methods

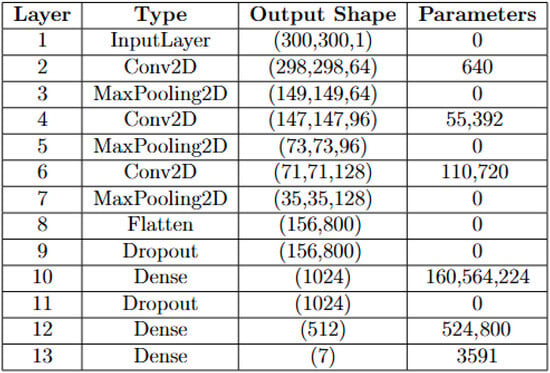

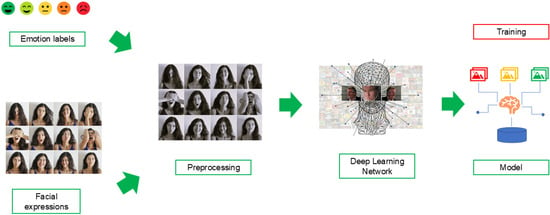

The emotion recognition method adopted in this study is based on a deep learning architecture (Figure 1) and consists of two main phases: the first is training (shown in Figure 2), aimed at creating a predictive model for emotion recognition, and the second is testing (shown in Figure 3), aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of the model.

Figure 1.

The Deep Learning model architecture step.

Figure 2.

Training step.

Figure 3.

Testing step.

The training phase begins with the collection of the dataset (i.e., Facial Expressions in Figure 2), considering facial expressions that have one or more movements or positions of the muscles under the skin of the face. Facial expressions are a form of voluntary or involuntary non-verbal communication, the underlying neural mechanisms of which differ in each case. Voluntary facial expressions are often socially conditioned and follow a cortical pathway in the brain. In contrast, involuntary facial expressions are innate and follow a subcortical pathway [3].

The images considered are labelled with one of the following emotions: anger, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, disgust, and neutrality (i.e., the emotion labels in Figure 1). Once we have obtained the facial expression images, we make them uniform through a preprocessing step (in Figure 1), in which we crop the images aligned on the face, resize them all to the same target size of 48 × 48 pixels, with a resolution of 96 dpi and bit depth of 8, and finally convert the images into a single grayscale channel.

All preprocessing, training and testing phases were performed using Orange Data Mining version 3.38.1 (Bioinformatics Laboratory, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia). Regarding models for emotion detection, in this paper we experiment with the following embedders:

- SqueezeNet: a deep model for image recognition with a thin structure, fewer structural parameters, and fewer calculations, in fact it only has 1 × 1 and 3 × 3 convolution kernels, with the aim of simplifying the network, while maintaining a classification accuracy similar to a public network [52].

- Inception v3: a deep Convolutional Neural Network’s framework that is particularly effective for image classification and recognition problems such as those of the ImageNet dataset. It has the innate ability to obtain fewer errors. It also has the advantage of minimizing concatenation operations to highly associated nodes so that they remain scattered [53].

For each embedder we consider the following algorithms (Table 1):

Table 1.

Hyperparameters set for each algorithm.

- Logistic Regression: a classification algorithm with LASSO (L1) or ridge (L2) regularization. It learns a Logistic Regression model from the data and it only works for classification tasks [54].

- Neural Network: uses sklearn’s Multi-layer Perceptron algorithm that can learn non-linear models as well as linear [55].

- Gradient Boosting: a distributed gradient enhancement optimized library designed to be efficient and flexible. It provides parallel tree boosting, implementing machine learning algorithms under the Gradient Boosting framework [56].

- Random Forest: an ensemble learning method used for classification, regression, and other tasks [57].

At this point, we have the dataset, or input, to feed into the convolutional neural network we have designed (Deep Learning Network in Figure 1), which consists of 14 layers that can be grouped into the following six levels:

- Conv2D: A 2-dimensional (2D) convolution layer with the purpose of generating a convolution kernel to produce an output tensor;

- MaxPooling2D: Performs down sampling of the input along its spatial dimensions to obtain the maximum value on an input window for each input channel;

- Batch Normalization: Essential for stabilizing the training of neural networks, its goal is to standardize the output, keeping the mean close to 0 and the standard deviation close to 1. During the training phase, it normalizes the data using the mean and standard deviation of the input batch. Instead, during inference, it uses a moving average of the statistics (mean and standard deviation) collected during training;

- Flatten: Converts multidimensional matrices into a two-dimensional matrix, typically in the transition from the convolutional layer to the fully connected layer, without influencing the batch size;

- Dropout: Prevents overfitting by randomly setting inputs to 0 during the training phase at a rate frequency at each step from this layer, while inputs not set to 0 are scaled by 1/(1 − rate) so that the sum of all inputs does not change;

- Dense: Each neuron takes input from every neuron in the prior layer, executing a matrix–vector multiplication. The values in this matrix, which serve as the layer’s parameters, can be learned and refined using backpropagation.

When the model has been built, we assess its effectiveness during the testing phase (Figure 3). This second phase uses images of facial expressions not used during the training phase (i.e., Face image in Figure 3). As in the previous phase, in this case we proceed with a preprocessing step to adapt the images to the format used for the images used during the training phase. Once the preprocessed facial image is entered into the constructed model, it will generate an emotional label for the analyzed face image (e.g., Emotion Detection in Figure 3).

4. Results

Our work began with an analysis of the ‘Emotion Detection’ dataset, obtained from the Kaggle repository, which is available online free of charge for research purposes [58]. Specifically, we carried out a quality check to verify whether the classification of the seven basic emotions (anger, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, disgust, and neutrality) was correct. This check revealed several misclassifications, such as the presence of unclear images, completely black images, written words instead of faces, or even the presence of images belonging to a certain emotional class under another label. Considering this, we created a new dataset according to a new labelling of emotions, eliminating ‘useless’ images. For example, Figure 4 shows examples of ‘useless’ images, such as black images, memes, symbols, unclear images, drawings, and words; Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show some misclassifications in the emotion labelling.

Figure 4.

Images that pollute the ‘Emotion Detection’ dataset from the Kaggle repository.

Figure 5.

Sad images classified in angry.

Figure 6.

Some misclassifications in neutral.

Figure 7.

Some misclassifications in sadness.

Furthermore, to optimize the performance of embedders, we have grouped the seven classes of emotions into four macroclasses of emotional labels following the criterion of the positivity and negativity of their emotional value. The four macroclasses are as follows:

- Disgust + Fear

- Happiness + Surprise

- Angry + Sadness

- Neutral

Table 1 shows the number of facial expression images for each emotional label we considered in the experiment, i.e., from the dataset created from scratch by our team, a total of 35,625 facial expression images were considered in our study.

Table 2 shows how we set the hyperparameters shown for model training. To perform the experiment, we used a machine with an 8th generation Intel i7 CPU and 16 GB of RAM, running Microsoft Windows 11 Pro. We used the software Orange (version 3.38.1) which is freely available online [59].

Table 2.

Our dataset. The # symbol indicates the number of images.

4.1. Experiment 1

We trained the models on 80% of the dataset, with the remaining 20% reserved for testing. A manual verification was performed to ensure that no identical images appeared in both the training and testing datasets, maintaining the integrity and independence of the evaluation process. To assess the model’s ability to recognize and distinguish different emotions from facial expression images, we considered the parameters of precision and recall. The results of the experimental analysis, based on the embedder used, are reported in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Precision, recall, and F1 Score with SqueezeNet.

Table 4.

Precision, recall, and F1 Score with Inception v3.

Essentially, Gradient Boosting achieved better results particularly with the Inception v3 embedder (precision 0.622, recall 0.626, F1 score 0.623), outperforming other algorithm–embedder combinations.

4.2. Experiment 2

In this section we show the results related to a subsequent experiment, in which we added a further preprocessing step obtained with a normalization of the interval [0–1], which was applied to all images of the dataset. Maintaining the dataset split into 80% of the images for training and the remaining 20% for testing, we obtained the results shown in Table 5 and Table 6. In this case, we considered all the metrics that Orange’s “Test and Score” widget provides: AUC, AC, F1 score, precision, recall, and MCC.

Table 5.

Results with SqueezeNet after normalization preprocessing.

Table 6.

Results with Inception v3 after normalization preprocessing.

Comparing the SqueezeNet and Inception v3 embedders, performance differences are highlighted depending on the classification algorithm used.

For Logistic Regression, the use of Inception v3 resulted in slightly higher values across all reported metrics. Accuracy increased from 0.605 to 0.611, while precision, recall, and F1 score increased from 0.589 to 0.599, from 0.605 to 0.611, and from 0.587 to 0.603, respectively. A corresponding increase in MCC was also observed (from 0.421 to 0.436).

Similar trends were observed for the remaining classifiers. With Random Forest, Inception v3 yielded marginal improvements in precision (0.627 vs. 0.620) and recall (0.579 vs. 0.573), while the F1 score remained unchanged (0.524). For the neural network, higher performance values were obtained when using Inception v3, with precision increasing from 0.610 to 0.624, recall from 0.611 to 0.627, and F1 score from 0.610 to 0.625. Gradient Boosting also showed improved results with Inception v3, with a higher precision (0.609 vs. 0.599), recall (0.611 vs. 0.596), and F1 score (0.584 vs. 0.564).

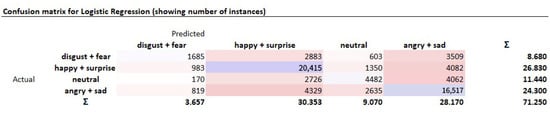

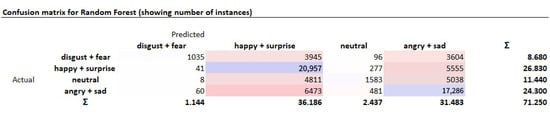

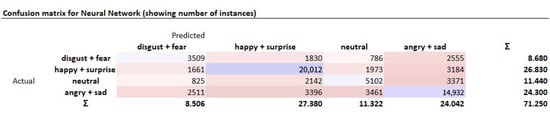

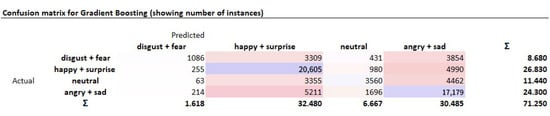

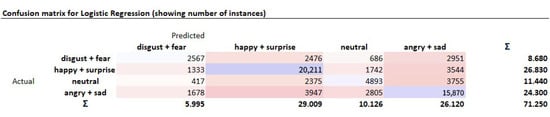

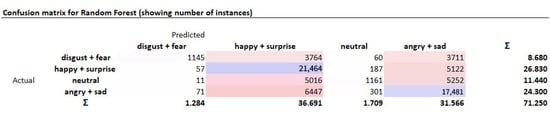

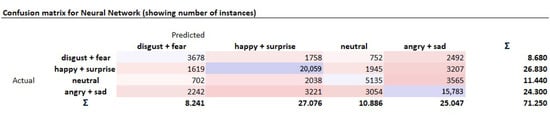

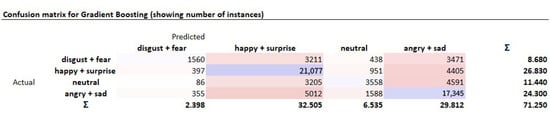

In addition to the quantitative evaluation, the classification performance was further analyzed through confusion matrices, which provide a detailed view of the distribution of correctly and incorrectly classified samples (Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15).

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (SqueezeNet).

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix for Random Forest (SqueezeNet).

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix for Neural Network (SqueezeNet).

Figure 11.

Confusion matrix for Gradient Boosting (SqueezeNet).

Figure 12.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (Inception v3).

Figure 13.

Confusion matrix for Random Forest (Inception v3).

Figure 14.

Confusion matrix for Neural Network (Inception v3).

Figure 15.

Confusion matrix for Gradient Boosting (Inception v3).

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper we proposed the adoption of several machine learning models for automatic emotion recognition starting from facial expression images.

The proposed models are designed to classify images of facial expressions into one of seven basic emotions: anger, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, disgust, and neutrality. A preliminary analysis was conducted on a dataset of 35,625 images. We analyzed the combined effects of data preprocessing, feature extraction through deep embedders, and classical machine learning classifiers. We considered SqueezeNet and Inception v3 embedders and compared model performance both before and after the application of a [0–1] normalization step.

The results obtained in Experiment 1, where no normalization was applied, indicate that classification performance depends on the choice of embedder and classifier. In this setting, Inception v3 consistently outperformed SqueezeNet across all evaluated classifiers, achieving higher precision, recall, and F1 score values. In particular, the combination of Inception v3 with Gradient Boosting yielded the best overall performance; conversely, models based on SqueezeNet generally exhibited a lower performance, highlighting potential limitations in capturing discriminative facial features without additional preprocessing.

The introduction of feature normalization in Experiment 2 combined with the inclusion of additional performance metrics, such as accuracy and MCC, resulted in more balanced classification behaviour. In particular, classifiers that showed limited effectiveness in Experiment 1, such as Random Forest, achieved more meaningful performance levels after normalization.

When comparing the two embedders under normalized conditions, Inception v3 again demonstrated a superior performance. Across all classifiers, the use of Inception v3 resulted in either consistent or marginally improved values for accuracy, F1 score, and MCC compared with SqueezeNet. These improvements were particularly evident for Neural Networks and Gradient Boosting. Logistic Regression also benefited from Inception v3, although the observed gains were moderate.

A further comparison between Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 highlights the positive impact of normalization on overall model behaviour. While Experiment 1 already showed clear differences between embedders, the application of normalization in Experiment 2 reduced performance variability across classifiers and improved result consistency. This suggests that normalization plays a key role in facilitating effective learning from deep feature embeddings, particularly when using heterogeneous classifiers.

In summary, the experimental findings indicate that Inception v3 represents a more effective embedding strategy than SqueezeNet for facial emotion recognition in the considered setting. Moreover, the adoption of feature normalization proves to be a critical preprocessing step, enhancing classifier robustness and enabling more reliable performance comparisons. These results emphasize the importance of jointly considering preprocessing, feature extraction, and classifier selection when designing emotion recognition systems based on deep feature embeddings.

From the limitations point of view, we are aware that mainly there are: class imbalance, poor quality and ambiguity for some images of the dataset and limited detailed control over learning parameters. More specifically:

- Our dataset shows a significant imbalance between the class “Happiness + Surprise” (13,417 images) and the class “Angry + Sadness” (with 12,151 images), compared with the classes “Disgust + Fear” (4339 images) and the single class “Neutral” (5718 images). To begin with, however, the “Disgust” and “Fear” classes, as present on the Kaggle repository, are individually made up of a smaller number of images, with 547 images for “Disgust” and 5121 images for “Fear”, compared with the 8989 images in the “Happiness” folder, 4002 images in the “Surprise” folder, 4953 images of the class “Angry”, and 6077 images of the class “sadness”. Therefore, a potential bias in favour of majority classes cannot be ruled out, which makes it appropriate to conduct future studies on more balanced datasets.

- The quality of some images within the dataset could be another factor influencing the learning capabilities of the model. Moreover, some images are characterized by a certain degree of ambiguity and similarity which makes it difficult to choose which emotional class they belong to, in addition to the fact that each classification, even if to a minimal extent, can be influenced by the subjectivity of the person analyzing the dataset during the classification of emotions.

- The Orange environment primarily provides a graphical interface that abstracts many implementation details. While this limits fine-grained control over learning parameters, it was selected to streamline experimentation and demonstrate model comparisons clearly. While Orange indeed abstracts some implementation details, it was intentionally chosen for its reproducibility and accessibility in comparative model evaluation. Despite limited parameter control, the environment supports standardized preprocessing and model benchmarking, ensuring fair and consistent comparisons across algorithms.

For future developments, remaining faithful to our intent to support the work of mental health professionals, we plan to incorporate explainability techniques such as Grad-CAM, LIME, or SHAP to provide visual and analytical insights into the model’s decision making process. These tools will help highlight the key image regions or features influencing predictions, thereby enhancing the model’s interpretability and clinical applicability. Integrating such activation map illustrations will also support better collaboration between AI systems and clinicians, aligning with this study’s emphasis on human–AI interpretability. We also hope to enrich emotional analysis through a multimodal approach, integrating the recognition of facial expressions with the analysis of vocal signals. Merging data from multiple information channels is a promising field of research, as multimodal recognition can overcome the limitations of a single channel [60]. This approach could provide mental health professionals with more comprehensive and reliable diagnostic and monitoring tools, enriching their assessments with more detailed and complex information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); methodology, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); software, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); validation, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); formal analysis, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); investigation, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); resources, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); data curation, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); writing—original draft preparation, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); writing—review and editing, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); visualization, J.L., M.C., A.S., F.M. (Fabio Martinelli) and F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo); supervision, F.M. (Francesco Mercaldo). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially supported by EU DUCA, EU CyberSecPro, SYNAPSE, PTR 22-24 P2.01 (Cybersecurity) and SERICS (PE00000014) under the MUR National Recovery and Resilience Plan funded by the EU-NextGenerationEU projects, by MUR - REASONING: foRmal mEthods for computAtional analySis for diagnOsis and progNosis in imagING - PRIN, e-DAI (Digital ecosystem for integrated analysis of heterogeneous health data related to high-impact diseases: innovative model of care and research), Health Operational Plan, FSC 2014-2020, PRIN-MUR-Ministry of Health, Progetto MolisCTe, Ministero delle Imprese e del Made in Italy, Italy, CUP: D33B22000060001, FORESEEN: FORmal mEthodS for attack dEtEction in autonomous driviNg systems CUP N.P2022WYAEW and ALOHA: a framework for monitoring the physical and psychological health status of the Worker through Object detection and federated machine learning, Call for Collaborative Research BRiC -2024, INAIL.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset exploited in the experimental analysis was obtained from following Kaggle repository: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ananthu017/emotion-detection-fer/data (accessed before 19 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Campeau, S.; Falls, W.A.; Cullinan, W.; Picard, R.W. Informatica Affettiva; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pel, G.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hua, S.; LI, T. Affective Computing: Recent advances, challenges, and future trends. Intell. Comput. 2024, 3, 0076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarelli, M.; Martinelli, F.; Mercaldo, F.; Santone, A. Emotion recognition from facial expression using explainable deep learning. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, International Conference on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, International Conference on Cloud and Big Data Computing, International Conference on Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech), Calabria, Italy, 12–15 September 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.F. MMATrans: Muscle movement aware representation learning for facial expression recognition via transformers. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 13753–13764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Wang, X. NGDNet: Nonuniform Gaussian-label distribution learning for infrared head pose estimation and on-task behavior understanding in the classroom. Neurocomputing 2021, 436, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Deng, L.; Liu, T.; Meng, R.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.F. ACAForms: Learning Adaptive Context-Aware Feature for Facial Expression Recognition in Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Robotics and Automation Engineering (ICRAE), Singapore, 15–17 November 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli, M.; Cabitza, F. Not in my face: Challenges and ethical considerations in automatic face emotion recognition technology. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 2201–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal, F.Z.; Müller, T.R.; Matias, J.C.; Scotton, G.G.; de Sa Junior, A.R.; Pozzebon, E.; Sobieranski, A.C. A survey on facial emotion recognition techniques: A state-of-the-art literature review. Inf. Sci. 2022, 582, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Sorenson, E.R.; Friesen, W.V. Pan-cultural elements in facial displays of emotion. Science 1969, 164, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrejevic, M.; Selwyn, N. Facial recognition technology in schools: Critical questions and concerns. Learn. Media Technol. 2020, 45, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.; Pentland, A. Eigenfaces for recognition. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1991, 3, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimino, G. Introduction to Modern Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Elettronica e Telecomunicazioni, 2020. pp. 5–20, RAI-Centre for Research, Technological Innovation and Experimentation. Available online: http://www.crit.rai.it/eletel/2020-1/201-2.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Naga, P.; Marri, S.D.; Borreo, R. Facial emotion recognition methods, datasets and technologies: A literature survey. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 2824–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, S.R.; Veer, K. Trends and challenges of image analysis in facial emotion recognition: A review. Netw. Model. Anal. Health Inform. Bioinform. 2022, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Viola, P. Fast Multi-View Face Detection; Mitsubishi Electric Research Lab TR-20003-96; Mitsubishi Electric Research Laboratories, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; Volume 3, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Soo, S. Object Detection Using Haar-Cascade Classifier; Institute of Computer Science, University of Tartu: Tartu, Estonia, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.S.; Prasad, S.; Semwal, V.B.; Tripathi, R.C. Real time face recognition using AdaBoost improved fast PCA algorithm. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Appl. 2011, 2, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, K.; Naveenkumar, M. A robust method for face recognition and face emotion detection system using support vector machines. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT), Mysuru, India, 9–10 December 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Rong, X. Facial expression recognition based on random forest and convolutional Neural Network. Information 2019, 10, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ji, Q. Active affective state detection and user assistance with dynamic Bayesian Networks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 2004, 35, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adyapady, R.R.; Annappa, B. A comprehensive review of facial expression recognition techniques. Multimed. Syst. 2023, 29, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, D.; Jeong, S.; Lee, J.; Park, S.H. Facial expression recognition based on local region specifc features and support vector machines. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 7803–7821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonen, T.; Hadid, A.; Pietikainen, M. Face description with local binary patterns: Application to face recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2006, 28, 2037–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Liu, Q.; Yang, P.; Huang, J.; Metaxas, D.N. Learning multiscale active facial patches for expression analysis. IEEE Transact. Cybern. 2014, 45, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liong, S.T.; See, J.; Wong, K.; Phan, R.C.W. Less is more: Micro-expression recognition from video using apex frame. Signal Process. 2018, 62, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Liang, J.; Zhan, G.; Liu, Z.; Pietikäinen, M.; Liu, L. Extended local binary patterns for efficient and robust spontaneous facial micro-expression recognition. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 174517–174530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, R.A.; Annappa, B. Micro expression recognition using delaunay triangulation and voronoi tessellation. IETE J. Res. 2023, 69, 8019–8035. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Baddar, W.J.; Jang, J.; Ro, Y.M. Multi-objective based spatio-temporal feature representation learning robust to expression intensity variations for facial expression recognition. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2017, 10, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Huang, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, L. Facial expression recognition based on deep evolutional spatial-temporal networks. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 4193–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Li, Q.; Huan, R.; Liu, J.; Han, G. Deep spatial-temporal feature fusion for facial expression recognition in static images. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 2019, 119, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.I.; Ionescu, R.T.; Popescu, M. Local learning with deep and handcrafted features for facial expression recognition. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 64827–64836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Yan, Y.; Lai, S.; Chai, Z.; Shen, C.; Wang, H. Feature decomposition and reconstruction learning for effective facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7660–7669. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Meng, Z.; Khan, A.S.; O’Reilly, J.; Li, Z.; Han, S.; Tong, Y. Identity-free facial expression recognition using conditional generative adversarial network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Anchorage, AK, USA, 19–22 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1344–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, C.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, W.; Qin, J.; Luo, Z. Clip-aware expressive feature learning for video-based facial expression recognition. Inf. Sci. 2022, 598, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Hu, H.; Wu, Y. Deep multi-path convolutional neural network joint with salient region attention for facial expression recognition. Pattern Recogn. 2019, 92, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Deng, W. Reliable crowdsourcing and deep locality-preserving learning for unconstrained facial expression recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 28, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xia, P.; Zhang, L.; Shao, L. A roi-guided deep architecture for robust facial expressions recognition. Inf. Sci. 2020, 522, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.; Qian, Y. Three convolutional neural network models for facial expression recognition in the wild. Neurocomputing 2019, 355, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarov, F.; Kutlimuratov, A.; Khojamuratova, U.; Abdusalomov, A.; Cho, Y.I. Enhanced AlexNet with Gabor and Local Binary Pattern Features for Improved Facial Emotion Recognition. Sensors 2025, 25, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, J.; Tian, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y. A fine-grained human facial key feature extraction and fusion method for emotion recognition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, J.; Han, Y. Facial Landmark-Driven Keypoint Feature Extraction for Robust Facial Expression Recognition. Sensors 2025, 25, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, I.J.; Nam, G.P. Navigating label ambiguity for facial expression recognition in the wild. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Volume 39, pp. 4517–4525. [Google Scholar]

- Abate, A.F.; Bisogni, C.; Castiglione, A.; Nappi, M. Head pose estimation: An extensive survey on recent techniques and applications. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 127, 108591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.Y.; Chung, C.J. A novel eye center localization method for head poses with large rotations. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 30, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, V.; Sullivan, J. One millisecond face alignment with an ensemble of regression trees. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1867–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Hempel, T.; Abdelrahman, A.A.; Al-Hamadi, A. 6d rotation representation for unconstrained head pose estimation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Bordeaux, France, 16–19 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 2496–2500. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.F. Orientation cues-aware facial relationship representation for head pose estimation via transformer. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 6289–6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, K.; VS, V.; Chellappa, R.; Patel, V.M. Facexformer: A unified transformer for facial analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 October 2025; pp. 11369–11382. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.G.; Xie, H.J.; Niu, X.C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.L.; Zhang, S.W.; Shan, Y.Z. Transformer-based weakly supervised 3D human pose estimation. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2025, 109, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wang, M.; Jiang, K.; Cao, M.; Iwahori, Y. A dual neural architecture combined SqueezeNet with OctConv for LiDAR data classification. Sensors 2019, 19, 4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubai, S.; Alqahtani, A.; Sha, M. Genetic hyperparameter optimization with Modified Scalable-Neighbourhood Component Analysis for breast cancer prognostication. Neural Netw. 2023, 162, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://orangedatamining.com/widget-catalog/model/logisticregression/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Available online: https://orangedatamining.com/widget-catalog/model/neuralnetwork/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Available online: https://xgboost.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Available online: https://orangedatamining.com/widget-catalog/model/randomforest/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ananthu017/emotion-detection-fer/data (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Available online: https://orangedatamining.com/download/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Cai, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J. Emotion recognition using different sensors, emotion models, methods and datasets: A comprehensive review. Sensors 2023, 23, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.