Abstract

The accurate prediction of crack initiation and propagation is essential for assessing the structural integrity of mechanically joined components and other complex assemblies. To overcome the limitations of existing finite element tools, a modular Python framework has been developed to automate three-dimensional crack growth simulations. The program combines geometric reconstruction, adaptive remeshing, and the numerical evaluation of fracture mechanics parameters within a single, fully automated workflow. The framework builds on open-source components and remains solver-independent, enabling straightforward integration with commercial or research finite element codes. A dedicated sequence of modules performs all required steps, from mesh separation and crack insertion to local submodeling, stress and displacement mapping, and iterative crack-front update, without manual interaction. The methodology was verified using a mini-compact tension (Mini-CT) specimen as a benchmark case. The numerical results demonstrate the accurate reproduction of stress intensity factors and energy release rates while achieving high computational efficiency through localized refinement. The developed approach provides a robust basis for crack growth simulations of geometrically complex or residual stress-affected structures. Its high degree of automation and flexibility makes it particularly suited for analyzing cracks in clinched and riveted joints, supporting the predictive design and durability assessment of joined lightweight structures.

1. Introduction

In fracture mechanics, the reliable prediction of crack initiation and propagation is a crucial requirement for the assessment and design of engineering structures [1]. In recent years, the increasing use of lightweight materials together with advanced joining techniques in manufacturing has introduced new challenges for structural integrity [2,3]. Mechanical joining methods such as clinching and riveting are widely employed in the automotive and aeronautical industries because they are cost-efficient and allow for the joining of dissimilar materials [4]. In the subproject B04 “Crack growth in joined structures” of the collaborative research center TRR285 “Method development for mechanical joinability in versatile process chains”, the Applied Mechanics working group of Paderborn University [FAM] is investigating fatigue crack growth in sheet metal starting from clinched or riveted joints. However, these joints represent potential weak points since the material plastically deforms during the joining process. Thus, damage processes occur where crack growth may initiate [5,6,7,8] and propagate under cyclic or static loading conditions [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. The aim of the investigations is to predict the crack growth lifetime of joined structures under fatigue loading. One of the tasks to achieve this aim is the development of customized experimental methods for determining the crack growth rate curves of the materials to be joined due to the influence of the previous plastic deformation in the vicinity of the joint [16]. Another task is the development of an approach for the formulaic description of experimentally determined crack growth rate curves, in which the material-dependent parameters can be determined easily and robustly. Such approaches are needed to calculate the number of load cycles for a defined crack growth increment at a specific stress intensity at the crack [17]. However, the essential task is the numerical simulation of crack growth. In the context of the TRR285, crack growth simulation is the final part of a complete simulation chain for the life cycle of mechanically joined structures using the finite element method (FEM), which ranges from the simulation of the joining process itself [18,19] to the simulation of the service life during the usage phase [7,8]. For this purpose, the commercial program system LS-DYNA must be used for the entire simulation chain within the context of the TRR285 to ensure the reliable transfer of intermediate simulation results. Traditional finite element analyses, although well established for global structural simulations, often lack the ability to accurately capture crack growth within complex joined regions. Advanced numerical approaches have opened the possibility of investigating arbitrary three-dimensional crack trajectories, non-proportional loading states, and local material inhomogeneities, such as CRACKTRACER [20], PROCRACK [21], and ADAPCRACK3D [22,23]. Further commercial programs for simulating crack propagation processes, such as FRANC3D and ZENCRACK, are described in the review paper by Alshoaibi and Fageehi [24]. However, such simulations, especially for special applications such as mechanical joining, typically require specialized implementations that go beyond standard commercial software solutions [25]. Experimental investigations, while indispensable for validation purposes, are time-consuming and often limited in their ability to resolve the internal evolution of cracks. Consequently, there is a strong need for simulation tools that can predict crack growth behavior within a finite element framework, both to support structural design optimization and to enhance the physical understanding of crack growth mechanisms. However, most existing commercial programs lack the flexibility needed to integrate user-defined modules to import preexisting residual stress fields, or to handle complex contact interactions [23]. Therefore, existing crack growth simulation programs usually require the use of specific software, such as ABAQUS [23,24], which, however, conflicts with the requirement that LS-DYNA must be used in the TRR285 research project. Furthermore, LS-DYNA does not offer modules such as the submodel technology, which is used, for example, for fracture mechanics analysis in the simulation program ADAPCRACK3D developed by the FAM [23]. To address these limitations, the FAM has developed GmshCrack3D, a new freely programmable and solver-independent simulation environment for modeling three-dimensional crack growth. The framework builds upon the open-source pre- and postprocessing platform Gmsh [26] and provides automated procedures for crack definition, adaptive local–global meshing, and iterative crack-front advancement. The objectives are for GmshCrack3D to offer at least the same capabilities as ADAPCRACK3D [23], to be compatible with the LS-DYNA program system, and to enable the free implementation of additional customized applications. Although the primary motivation arises from the simulation of crack growth in clinched and riveted joints, the proposed framework is general and applicable to a wide range of crack growth problems. The subsequent sections outline the theoretical background, the numerical methodology, and representative simulation results that demonstrate the capability and versatility of the developed tool.

2. Fundamentals of Fracture Mechanics

An understanding of the fundamental fracture mechanisms that govern crack propagation is indispensable for developing reliable numerical crack growth simulation tools [27]. Fracture mechanics provides the theoretical framework that links stresses, strains, and energy changes at the crack tip to measurable quantities, such as stress intensity factors and energy release rates. In structural components, the presence of a crack introduces a strong stress intensity whose magnitude depends on the geometry, the applied loading, and the material properties. When the local stress intensity or strain energy in the vicinity of the crack tip exceeds a critical level, the crack begins to advance. Describing this process quantitatively requires a formulation that relates the microscopic fracture processes at the crack tip to macroscopic quantities accessible in finite element simulations. Classical linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM) offers such a formulation by expressing crack driving forces either in terms of the stress intensity factor () or the energy release rate () [28]. These two quantities are energetically equivalent and form the basis for most analytical and numerical methods of crack growth analysis. The following sections summarize the main theoretical concepts, introduce the energy release rate and the different crack-tip loading modes, and outline their implementation within the newly developed simulation framework GmshCrack3D.

2.1. Energy Release Rate

The fundamental concept governing the onset and propagation of cracks in solid materials is the balance of energy at the crack tip. When a crack advances by a small increment, a portion of the elastic strain energy stored in the surrounding material is released. This quantity, normalized by the newly created fracture surface area, is defined as the energy release rate (), representing the mechanical driving force for crack propagation:

where denotes the change in the potential (elastic) energy of the body, and denotes the increase in the crack surface area [28]. A crack will continue to grow in an unstable manner when the available energy release rate () reaches or exceeds the critical energy release rate (), also referred to as the material’s fracture toughness. The energy release rate is therefore a fundamental link between material behavior and external loading, expressed in terms of energy per crack area with the unit J/m2 [28].

2.2. Crack-Tip Loading Modes

Stress and deformation at the crack tip can be decomposed into three independent loading modes:

- Mode I (opening mode): tensile separation normal to the crack plane.

- Mode II (sliding or in-plane shear mode): opposed sliding of the crack surfaces in the direction of the crack.

- Mode III (tearing or out-of-plane shear mode): opposed sliding of the crack surfaces in the direction of the crack front.

In practical applications, cracks are often subjected to a combination of these loading modes. The corresponding total energy release rate then results as [28]

2.3. Linear Elastic Fracture Mechanics Relation

Within the linear elastic framework, the local stress state in the vicinity of the crack tip is characterized by the stress intensity factors , , . These factors quantify the intensity of the singular stress field at the crack tip and are related to the energy release rate () through the energetic equivalence

where is the Young’s modulus and is the Poisson’s ratio. This relation forms the theoretical basis for calculating crack-tip parameters in numerical simulations. It enables direct conversion between stress-based and energy-based quantities and thus a flexible assessment of mixed-mode loading conditions [28].

The theoretical background outlined in this section provides the physical basis required for the numerical simulation of crack propagation. By linking the energy-based fracture mechanics criteria to discrete quantities such as forces and displacements in a finite element model, crack growth can be described in a consistent and solver-independent manner. Building on these principles, the following section presents the structure and functionality of the developed modular simulation framework GmshCrack3D, in which the theoretical concepts of fracture mechanics are realized through automated geometric and numerical procedures.

3. Structure and Functionality of Simulation Framework

A modular Python (version 3.11.8) framework has been developed to automate the complete workflow of a local–global fracture mechanics simulation in finite element (FE) models. The program organizes a sequence of geometric, meshing, and numerical operations, enabling a fully automated simulation of stepwise crack propagation in three-dimensional solid structures. Each stage is encapsulated as a dedicated Python module that executes a specific task, while all modules are coordinated by a single main driver script. This modular design is advantageous, as individual tasks can easily be modified or replaced. In the current version, the program runs with LS-DYNA; however, the steps for file handling and simulation can be adapted to support other solvers and stored as separate program variants, establishing a fully solver-independent framework.

3.1. Input Processing and Model Initialization

In the first step (ProcessInputfile), the framework analyzes the user-specified LS-DYNA keyword file and constructs the directory hierarchy for the crack stage under consideration. A unique working directory, Crack_N, is created for each simulation cycle, containing subfolders for the global model and local submodels. All relevant .k and .inc files of the model are copied into this workspace to ensure version control and clean-restart capabilities. If the model uses an include structure and the user provides an include file instead of a keyword file, it is automatically duplicated as .k format to guarantee compatibility with LS-PrePost.

3.2. Separation into Local and Global Models

The module DivideIntoLocalGlobal imports the LS-DYNA mesh of the whole model via meshio, converts it to the Gmsh format, and merges it with a CAD representation of the crack surface (.brep). Using the Gmsh ExtractElements plugin, each element centroid is inspected to determine whether its distance from the crack surface is smaller than a prescribed local model size (LMS). Elements inside this radius are assigned to the local model, while all others constitute the global model. After the crack-proximal elements have been tagged, the model is made invisible, except the tagged local elements. This is followed by an iterative connectivity filter. In each pass, the script checks whether every remaining local tetrahedron shares enough nodes (is sufficiently connected) with its neighbors. Any elements that fall below this threshold, indicating isolation or geometric degeneracy, are removed. The loop continues until no further orphaned elements remain, ensuring that the extracted submesh forms a coherent, physically meaningful model. Finally, the global mesh is reloaded, and the same element list is used to hide (mask out) these regions in the global model, leaving a clean cavity where the refined local mesh will later be inserted. This three-step procedure: visibility control, connectivity filtering, and global masking, yields separate, consistent .msh files for the local and global models, ready for subsequent simulation stages.

3.3. Mesh-to-Geometry Conversion

In Mesh2Geometry, the finite element mesh of the local model is reconstructed as a topological B-rep geometry. Each element node is converted into an OCC (OpenCascade) vertex, edges are created between the corresponding corner nodes, and plane surfaces are generated from these edge loops. Finally, a closed surface shell and a single OCC solid are created, representing the defect-free local volume around the crack region. The geometry is exported as .brep and used as a geometric container for inserting and manipulating the crack surface.

3.4. Insertion of the Crack Geometry

The CrackInsertion module merges the CAD file of the crack surface (Crack_N.brep) with the previously constructed local volume. A Boolean fragment operation (occ.fragment) is executed to explicitly cut the crack surface through the local volume. Newly generated faces belonging to the crack are identified and grouped into physical sets for the crack surface, the crack boundary, and the crack fronts. An auxiliary routine classifies edges along the crack surface and assigns physical IDs for each front segment. These groups allow for the later identification of crack faces during meshing, simulation, and postprocessing.

3.5. Controlled Local Remeshing

In LocalmodelPremeshing, anisotropic mesh-size fields are defined around the crack front and the crack surface using Gmsh mesh field functions. Distance fields are created for the edges of each crack front and for the crack surface faces. Two threshold functions specify the desired minimum and maximum element sizes at given distances from these features. These fields are combined using a Min operation to ensure that, at any location, the smallest element size dictated by either distance criterion is applied. The mesh for the local volume with the crack is generated with a 3D algorithm and optionally corrected for inverted surface normals. If neighboring crack surface patches have opposite orientation, element orders are reversed locally to maintain consistent normal vectors. The final remeshed local model, now with the crack included, is exported as Localmodel_modified.msh.

3.6. Creation of the Submodel Around the Crack Tip

The module CreateRecSubmodel builds an additional refined rectangular or cylindrical submodel around the crack-tip region intended for fracture mechanics evaluation. Starting from the crack-front edges, the routine determines the nodal coordinates and tangent, normal, and cross-product vectors by evaluating parametric derivatives and surface normals in Gmsh. These vectors define orthogonal local coordinate systems along the crack front. A structured mesh block is then generated by extruding points along these local vectors, creating successive layers of hexahedral elements in front of and behind the crack tip. Physical groups define the crack face, front line, and surrounding volume, which later allows for extraction of stress intensity factors. The mesh is subsequently generated as a transfinite, mostly hexahedral block using Gmsh’s setTransfinite instructions, ensuring consistent node numbering and alignment. The number of elements surrounding each crack-front node can be specified by the user (default value = 4). This module uses the same theoretical background as the submodel technique used in ADAPCRACK3D [22,23].

3.7. Final Meshing and Introduction of Double Nodes

In LocalmodelFinalmeshing, the LS-DYNA Crack plugin is executed on the local model to split the mesh along the crack surface. This operation duplicates all nodes lying on the crack surface, producing coincident nodes for the opposing crack faces. Line and surface elements that are not part of the 3D domain are hidden and subsequently deleted to prevent solver errors. The outer surface of the final local model with the crack mesh is numerically consistent with the outer surface of the original local model and ready for reintegration into the global model.

3.8. Merging with the Global Model

The module MergeLocalGlobalModel first computes centroids of all local and global solid elements and matches overlapping regions using a k-d tree algorithm with a very small tolerance. Matching elements in the global model are replaced by the corresponding elements of the local model with the crack. Node duplication along the common interface between the global model and the local model is resolved by coordinate matching, ensuring full geometric continuity.

3.9. Transfer of Initial Stresses

If the global model already contains an INITIAL_STRESS_SOLID section, the Stressmapping module reads the integration point stresses from the LS-DYNA input, computes equivalent nodal values through interpolation or extrapolation (depending on the element order), and maps these to the new mesh coordinates. Volumetric- and coordinate-based consistency checks ensure that mass and stress integrals are preserved. The rewritten _modified.k file thus represents a complete, stress-consistent global model with the newly inserted cracked region. This module enables consideration of initial stresses arising from the manufacturing process of a joined component in the subsequent fracture mechanics simulations.

3.10. File Formatting and Main LS-DYNA Run

Before starting the finite element analysis, the model keyword file is reformatted through the LSPrePostReformating module. A command file is automatically written and passed to LS-PrePost, which resaves the keyword deck in a standardized syntax compatible with the target LS-DYNA version.

3.11. Simulation

Subsequently, the LSRun module launches the solver with user-defined parameters, such as number of CPUs and memory allocation, ensuring that all output is placed in the working directory of the current crack stage. This step can be exchanged to accommodate other solvers, further improving the generality of the framework. Since the finite element simulation is executed solely by LS-DYNA and Gmsh is used only for mesh preparation, all solver-specific operations (contact definitions, boundary conditions, material models) remain fully accessible when using GmshCrack3D.

3.12. Submodel Preparation and Mapping of Global Displacements

After completion of the global analysis, the submodel created previously in 3.6 is prepared for the local evaluation (SetupSubmodel). The displacements obtained from the global simulation (d3plot) are mapped onto the boundary nodes of the submodel, ensuring that its boundary conditions remain fully consistent with the global model.

3.13. Fracture Mechanics Evaluation of Submodel

In the next step, the EvalMaxKv module performs the fracture mechanics evaluation of the prepared submodel. Nodal forces extracted from the LS-DYNA binout database are combined with the interpolated global displacement field to calculate the relative displacements between paired nodes on the opposing crack faces. From these quantities, the local energy release rate components () are computed according to [28]

is the nodal force at the crack tip, is the relative displacement of the duplicated nodes at a distance () in front of the crack tip, and is the partial width of the additional crack area assigned to the crack-tip node, where times is the partial additional crack area () assigned to the crack-tip node. To suppress numerical oscillations, a polynomial smoothing of the resulting -distributions along the crack front is applied [29]. Subsequently, the stress intensity factors (, , and ) are derived from the smoothed energy release rates describing the state of mixed-mode loading at each crack-front position. The effective mixed-mode stress intensity factor () and the crack kinking angle (), as well as the crack twisting angle () depending on the mixed-mode ratio are then evaluated using the -criterion [1], describing the direction and proportion of the crack growth increment at each crack-front position. This module uses the same fracture mechanical background as the submodel technique used in ADAPCRACK3D [22,23].

3.14. Crack-Front Update and Geometry Regeneration

In EvalSubmodel, the local crack growth increment () is derived from a Paris-type law [17,30,31], in which the increment depends on the local . It is scaled so that the maximum growth per simulation step depending on the maximum does not exceed a prescribed value max (). The number of load cycles for this maximum crack increment is estimated using the calculated range of the stress intensity and the experimentally determined crack growth rate curves [17,30,31]. This establishes a direct link between the theoretical fracture mechanics framework, the implemented computational procedure, and experimental results. For each crack-front node, the crack growth vector is computed from the interpolated normal and in-plane direction vectors using the mode-mixing angles and [1]. The displaced front points are written into the CAD representation of the crack surface. In Gmsh, these points are converted into OCC vertices, connected by B-splines, and combined with the existing crack edges to reconstruct a new crack surface via occ.addSurfaceFilling. The geometry is healed to remove duplicate entities and exported as a new Crack_{N+1}.brep file, which serves as input for the next simulation step. This step closes the simulation loop, allowing for fully automated iterative crack growth analyses without manual user interaction.

3.15. Overall Workflow

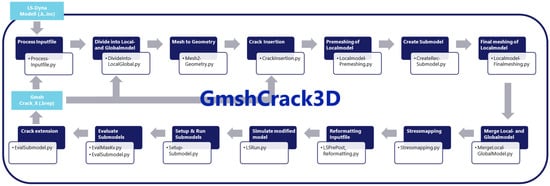

The main driver script sequentially executes all modules in the order described, automatically passing essential data, such as file paths, physical group IDs, element types, and crack-front properties, between them. After each iteration, the workflow provides the updated global keyword files, solver outputs, and geometric representation of the newly propagated crack surface. The modular structure allows for the optional replacement or refinement of individual steps, enabling straightforward adaptation to other materials, element types, or crack growth laws. Through the main script, various global parameters can be adjusted to optimize the simulation performance and accuracy. The workflow of the program is shown schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of program workflow and associated file-processing steps.

To illustrate the individual operations and to verify the functionality of the overall process, representative simulations were carried out using a mini-compact tension (Mini-CT) specimen. The following section demonstrates each stage of the workflow as applied to this benchmark geometry and highlights the correlation between the theoretical concepts and their practical realization within GmshCrack3D.

4. Application Example for a Mini-CT

To demonstrate the functionality and degree of automation of the developed simulation framework, a verification study was carried out using a mini-compact tension (Mini-CT) specimen. The dimensions of this specimen are a width () of 20 mm, a thickness () of 2.5 mm, and a length of the starter notch () of 4 mm. This standardized geometry is widely used in fracture mechanics testing and therefore provides a suitable benchmark for assessing the performance of the implemented local–global workflow. While the individual steps follow the methodology described in Section 3, the focus here is on demonstrating the practical application of the program and the sequential transformation of the model from the original finite element mesh to the final configuration with crack.

The finite element model of the Mini-CT specimen was designed to replicate the experimental boundary conditions of a standard tensile test setup using pins. Since no rigid clamping jaws or contact surfaces are present in the real test setup, the boundary conditions were implemented to reflect the realistic mechanical behavior of pin fixation. Specifically, four key nodes, located at the corners of the specimen, were assigned displacement constraints to prevent rigid body motion:

- The bottom right corner (front face) was fixed in all three translational directions (x, y, z).

- The bottom right corner (rear face) was constrained only in the x-direction.

- The bottom left corner (front face) was constrained only in the y-direction.

- The top right corner (front face) was constrained only in the z-direction.

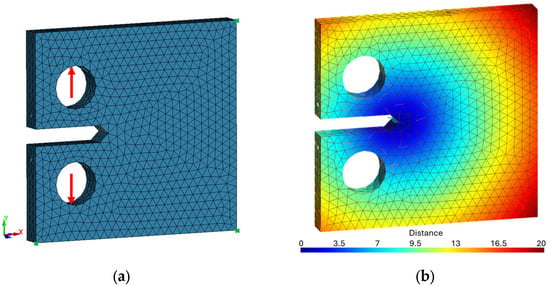

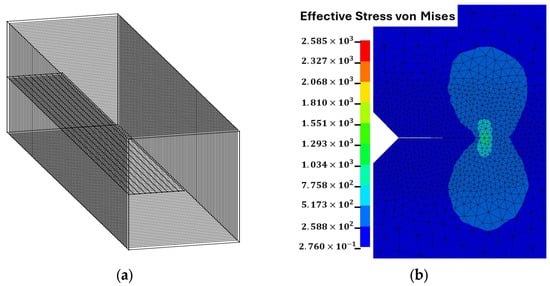

This statically determined configuration ensures full restraint against rigid body motions while allowing for small rotational degrees of freedom, which is consistent with the actual physical behavior of pin joints. The applied load was simulated by introducing opposite forces (1 kN) at the pin-hole locations. The loading was applied in the y-direction of the specimen, ensuring a uniform and realistic stress state around the preexisting crack. Figure 2a shows the initial finite element (FE) model of the Mini-CT specimen with the location of the boundary conditions in green and the applied load. The model consists of a three-dimensional tetrahedral mesh representing the complete specimen geometry. At this stage, the structure is continuous, without any predefined crack geometry, and serves as the global starting model for all subsequent operations.

Figure 2.

(a) Boundary conditions and loading setup for the finite element model of the Mini-CT specimen. The model is restrained at four corner nodes. (b) Distance field for element centroids to the imported crack surface.

In the first automated preprocessing step, the module DivideIntoLocalGlobal determines which elements belong to the local model. For this purpose, the distance from each element centroid to an imported initial crack surface definition is calculated. The used starting crack was modeled as a rectangular through a thickness crack measuring 1.0 × 2.5 mm, positioned within the Mini-CT specimen so as to produce a straight crack front across the thickness, resulting in an initial crack length of 4.5 mm. Elements located within the user-defined local model size (LMS = 4) are assigned to the local model, while the remaining elements form the global model. Figure 2b visualizes the computed distance field used for this classification; the color gradient clearly separates the critical crack-tip zone from the surrounding structure.

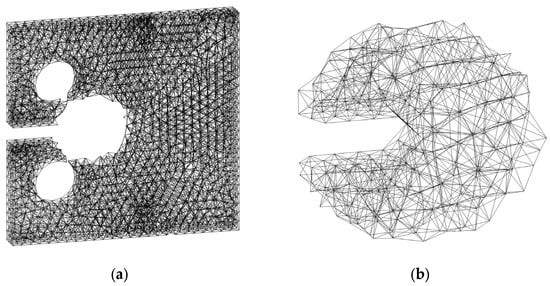

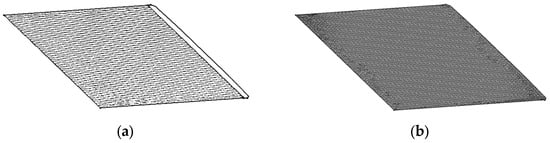

Based on the distance criterion, the complete mesh is divided into two geometrically consistent part meshes. Figure 3a and Figure 3b show the resulting global and local models, respectively. The local model encloses the region around the pre-crack and is subsequently converted into a B-rep geometry for further CAD-based operations, whereas the complementary global model remains as the outer domain into which the modified local model with crack is later reinserted. This separation enables refined meshing and data mapping strictly within the fracture-relevant region, maintaining computational efficiency.

Figure 3.

(a) Global model with separated local model; (b) local model around the crack.

After separation, the local finite element mesh is reconstructed into a B-rep geometry This reconstructed solid acts as a geometric container for the definition of the crack. The CrackInsertion module merges the defined CAD surface of the crack into this volume and performs a Boolean fragment operation, cutting the surface through the solid. Newly created crack faces, crack fronts, and boundary edges are automatically detected and grouped into physical groups. Figure 4a shows the newly generated crack geometry with the identified crack edges and the front line. This representation forms the geometric basis for the subsequent meshing and fracture mechanics evaluation.

Figure 4.

(a) Local model with the detected crack edges (red) and crack front (yellow); (b) remeshed local model, refined around the crack tip.

The modified local geometry is remeshed with anisotropic refinement around the crack surface to ensure the accurate resolution of stress and displacement gradients (Figure 4b).

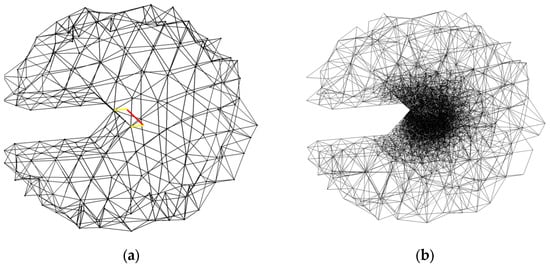

Following remeshing, a structured submodel is created around the crack-tip region (Figure 5a). This submodel mainly consists of hexahedral elements aligned with the local crack-front coordinates and provides the spatial resolution required for calculating energy release rates and stress intensity factors.

Figure 5.

(a) Submodel around the crack tip for fracture mechanical evaluations; (b) representative result of a single simulation step.

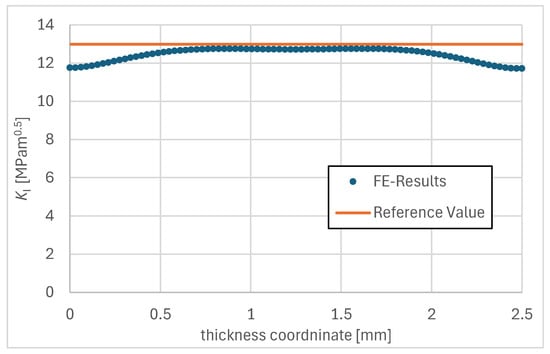

The prepared and remeshed local model with crack is reinserted into the global structure, and the complete assembly is analyzed using LS-DYNA. Figure 5b presents a representative simulation result showing the deformed configuration and a contour plot of the von Mises stress distribution of the Mini-CT specimen with the inserted crack under applied tensile loading. The numerical data extracted from this stage is the basis for evaluating the local fracture mechanics parameters and validating the implemented propagation procedure. Based on this numerical basis, the stress intensity factor () for the crack-tip node in the middle of the specimen is considered a representative value and compared with the reference value calculated using the -factor equation for CT specimens from the literature [28]. The crack length of = 4.5 mm and the applied force of = 1000 N are used for the calculation of the reference value. The numerically calculated representative value is = 12.74 MPa. The reference value is = 12.99 MPa. Figure 6 shows the course of the numerically calculated stress intensity factors () across the thickness of the Mini-CT specimen compared with the constant reference value (). The maximum values of agree very well with the reference value (), confirming the applicability of the implemented submodeling strategy and the fracture mechanical analysis. Typically, the values for decrease towards the surfaces, which causes the well-known thumbnail shape of the crack front in experimental investigations of Mini-CT specimens. and are zero except for numerical deviations.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the course of with the reference value () across the thickness of the Mini-CT specimen.

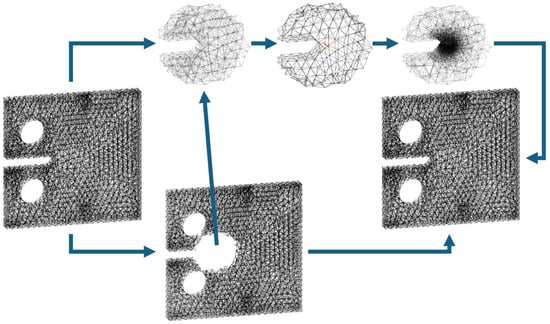

After the numerical evaluation, the crack-front data obtained from the fracture mechanical analysis of the submodel are used to generate the geometry for the next simulation step. The local crack growth increment is determined for each node along the crack front according to the implemented propagation criterion. The updated front coordinates are then written into the CAD description of the crack surface. New crack-front segments are created and connected by spline curves, and a closed B-rep surface representing the advanced crack is generated. Figure 7a illustrates the resulting new crack geometry together with the previous front position. This automated reconstruction ensures geometric continuity between successive propagation steps and allows the overall simulation loop, from analysis to geometry regeneration, to proceed without manual intervention. Figure 7b shows the final crack geometry for the following step.

Figure 7.

(a) Initial crack geometry with crack extension; (b) new crack geometry for next simulation step.

The presented example demonstrates the fully automated workflow of GmshCrack3D applied to a standardized specimen geometry. Each stage, from model segmentation to crack insertion and local remeshing, proceeds without manual interaction and ensures geometric consistency between local and global models. The workflow shown in Figure 8 is repeated for each crack growth increment, enabling the stepwise simulation of propagation under defined loading conditions. The Mini-CT example thus confirms the robustness and computational reliability of the framework in handling realistic three-dimensional crack scenarios and provides the foundation for its application to more complex joined structures, such as clinched or riveted connections.

Figure 8.

Schematic workflow of the finite element model from the division into local and global domains (DivideIntoLocalGlobal) to their reintegration (MergeLocalGlobalModel).

Having established the reliability and automation of the framework on this benchmark configuration, the following discussion focuses on its advantages, efficiency, and significance for analyzing fracture phenomena in mechanically joined structures.

5. Discussion

Having established the reliability and automation of the framework through the Mini-CT benchmark, this section discusses the broader significance and performance of the developed approach. Emphasis is placed on its advantages and disadvantages in flexibility, computational efficiency, and applicability to joined structures.

The presented simulation framework integrates geometry handling, adaptive meshing, and fracture mechanics evaluation into one automated process. Compared with traditional manual modeling approaches, this automation significantly reduces user effort and eliminates common sources of error, such as inconsistent mesh transitions or incomplete data exchange between stages. The modular Python structure further ensures easy adaptation to different solvers and element formulations, enabling application across diverse engineering scenarios. A key advantage of the presented workflow is the consistent transfer of data between the local model and the global model. The automated mapping of stresses, displacements, and geometry updates guarantees continuity at their interface after each crack growth increment. This robust coupling allows for the sequential simulation of multiple growth steps without manual remeshing or boundary condition redefinition, maintaining geometric and mechanical consistency throughout the analysis.

It is expected that the local–global approach substantially reduces the computational time and modeling effort while maintaining high resolution in the crack-tip region. This balance between detail and model economy enables three-dimensional crack growth simulations even on standard workstation hardware. Comparison of numerical and theoretical results for the Mini-CT specimen confirms the accuracy of the implemented algorithms, yielding physically consistent energy release rates and stress intensity factors. The adaptive refinement and automated correction of the element orientation preserve the mesh integrity across successive crack-front updates, ensuring numerical stability for long-term fatigue analyses. Overall, the expected efficiency and stability, based on many years of experience with ADAPCRACK3D [23], demonstrate that the framework provides a practical computational compromise between accuracy and cost.

While the Mini-CT specimen serves as a verification case, the primary motivation behind the framework lies in its application to mechanically joined components, such as clinched or riveted structures. These assemblies involve residual stress, local plastic deformations, and material inhomogeneities introduced by the joining process. Conventional fracture mechanics analysis tools often fail to capture these effects because of geometric complexity and contact interfaces. The developed framework addresses these limitations by enabling fully automated crack insertion and evaluation at arbitrary positions within preexisting, often complex FE models. Through the modular architecture, refined local meshes can be generated directly around interfaces, rivet holes, or clinch joints, while the global stress state, including residual stresses from manufacturing, is preserved using the implemented mapping routines. Consequently, GmshCrack3D should provide a robust tool for investigating crack propagation starting from an initial technical crack in joined structures, where experimental access is limited.

Cracks in the vicinity of clinched or riveted joints are usually internal cracks, so that at least two crack fronts are typical. In the case of such multiple cracks, the method described for inserting the crack geometry into the global model and the fracture mechanical evaluation using the submodel technique is applied to each partial crack. In the FE simulation of the global model, all cracks are considered simultaneously, including their mutual influence. In the case of crack branching or crack coalescence, manual intervention is still necessary at the current stage of GmshCrack3D to consider the resulting change in the crack-front description.

6. Conclusions

A modular Python framework for the automated simulation of three-dimensional crack propagation in finite element models has been developed and verified within this study. The main advantage of GmshCrack3D is its solver-independent architecture, which enables straightforward coupling with existing FE environments while maintaining full flexibility for user-defined extensions and specialized material models. By unifying geometric operations, remeshing, and field-mapping routines, the framework enables detailed investigation of the fracture mechanics behavior in regions affected by residual stress, material inhomogeneities, or contact interfaces, effects that are often inaccessible through experimental methods alone. Future extensions will target fatigue and mixed-mode crack growth capabilities, as well as the enhanced modeling of interface-dominated damage in multimaterial joints, since the program is a prerequisite for the scientific investigation of crack propagation in the vicinity of mechanically joined bonds, especially using LS-DYNA as a solver of FE models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K. and S.K.; methodology, T.D. and S.K.; software, T.D.; validation, S.K.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.K.; writing—original draft, S.K.; writing—review and editing, G.K. and S.K.; visualization, T.D. and S.K.; supervision, G.K. and R.O.; project administration, B.S.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—TRR 285/2—418701707.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: www.trr285.de.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-5 for language polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Crack surface | |

| CAD | Computer Aided Design |

| CT | Compact tension |

| Young’s modulus | |

| Force | |

| FAM | Applied Mechanics working group of Paderborn University |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| Energy release rate | |

| Energy release rates for Mode I, Mode II, and Mode III loading | |

| Stress intensity factor | |

| Stress intensity factors for Mode I, Mode II, and Mode III loading | |

| Effective mixed-mode stress intensity factor | |

| N | Number of simulation steps |

| Potential elastic energy | |

| Increment of crack length due to crack growth | |

| Relative displacement of duplicated nodes | |

| Partial width of additional crack area () due to crack growth | |

| x, y, z | Coordinates |

| Poisson’s ratio |

References

- Schöllmann, M.; Fulland, M.; Richard, H.A. Three-Dimensional Fatigue Crack Growth Simulation under complex loading with Adapcrack3D. In Fracture Mechanics: Applications and Challenges; Fuentes, M., Elices, M., Martín-Meizoso, A., Martínez-Esnaola, J.-M., Eds.; ESIS Publication 26; CD-ROM-Proceedings, section 9 (numerical methods), paper 5; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, H.E. (Ed.) Leichtbau in der Fahrzeugtechnik, 2nd ed.; Springer-Vieweg: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, J. Praxis der Umformtechnik: Umform- und Zerteilverfahren, Werkzeuge, Maschinen; Springer Vieweg: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Estayeh, M.M.; Hrairi, M.; Mohiuddin, A.K.M. Clinching process for joining dissimilar materials: State of the art. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 82, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, S.K.; Ko, D.C.; Kim, B.M. Parametric study on mechanical clinching process for joining aluminum alloy and high-strength steel sheets. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2010, 24, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewenz, L.; Bielak, C.R.; Otroshi, M.; Bobbert, M.; Meschut, G.; Zimmermann, M. Numerical and experimental identification of fatigue crack initiation sites in clinched joints. Prod. Eng. 2022, 16, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzheim, S.; Ewenz, L.; Zimmermann, M.; Wallmersperger, T. Corrosion phenomena and fatigue behavior of clinched joints: Numerical and experimental investigations. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2022, 6, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Harzheim, S.; Hofmann, M.; Wallmersperger, T. Numerical investigation of the effects of pitting corrosion on high-cycle fatigue of clinched joints. Acta Mech. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, W.; Deng, C.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X.; Men, Y.; Dong, L. Research advances in fatigue behaviour of clinched joints. Critical Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, A.K.; Bajwa, D.S.; Pramanik, A. Fatigue Behaviour of Mechanical Joints: A Review. Metals 2025, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Chen, C. Investigation of crack propagation characteristics in clinched joints under different failure modes. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 212, 113129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, C.; Wang, T.; Xu, C.; Peng, J.; Lu, Y.; Lei, B.; Jiang, J. Fatigue Fracture Mechanism and Life Prediction of TA1 Titanium Alloy Clinched Joints. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2025, 48, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Peng, R.; Xu, H.; Zhu, L.; Wang, T. The fatigue fracture mechanism of Al7075 aluminum alloy clinching joints. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2023, 237, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spak, B.; Schlicht, M.; Nowak, K.; Kästner, M.; Froitzheim, P.; Flügge, W.; Fiedler, M. Estimation of Fatigue Life for clinched joints with the Local Strain Approach. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2022, 38, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilinger, Á.; Cserépi, M.F.; Lukács, J. Behaviour of aluminium/steel hybrid RSW joints under high cycle fatigue loading. Weld World 2024, 68, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, D.; Schramm, B.; Kullmer, G. Holistic investigation chain for the experimental determination of fracture mechanical material parameters with special specimens. Prod. Eng.—Res. Dev. 2021, 16, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullmer, G.; Weiß, D.; Schramm, B. An alternative and robust formulation of the fatigue crack growth rate curve for long cracks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 296, 109826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielak, C.R.; Böhnke, M.; Beck, R.; Bobbert, M.; Meschut, G. Numerical analysis of the robustness of clinching process considering the pre-forming of the parts. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2021, 3, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhnke, M.; Rossel, M.S.; Bielak, C.R.; Bobbert, M.; Meschut, G. Concept development of a method for identifying friction coefficients for the numerical simulation of clinching processes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhondt, G. Application of the Finite Element Method to mixed-mode cyclic crack propagation calculations in specimens. Int. J. Fatigue 2014, 58, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabold, F.; Kuna, M.; Leibelt, T. Procrack: A Software for Simulating Three-Dimensional Fatigue Crack Growth. In Advanced Finite Element Methods and Applications; Apel, T., Steinbach, O., Eds.; Springer Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Fulland, M. Risssimulationen in Dreidimensionalen Strukturen mit Automatischer Adaptiver Finite-Elemente-Netzgenerierung; Fortschritt-Bericht VDI, Reihe 18: Mechanik/Bruchmechanik Nr. 280; VDI-Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, T.D.; Weiß, D.; Schramm, B.; Kullmer, G. Further Development of 3D Crack Growth Simulation Program to Include Contact Loading Situations. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshoaibi, A.M.; Fageehi, Y.A. A Comparative Analysis of 3D Software for Modeling Fatigue Crack Growth: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöllmann, M.; Fulland, M.; Richard, H.A. Simulation of Fatigue Crack Growth using the Finite Element Method. In Advances in Computional Engineering & Sciences; Atluri, S.N., Brust, F.W., Eds.; Tech Science Press: Palmdale, CA, USA, 2000; Volume I, pp. 1059–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Geuzaine, C.; Jean-François Remacle, J.-F.; Gmsh. A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Mesh Generator with Built-in pre- and Post-Processing Facilities. Available online: https://gmsh.info/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Fulland, M.; Schöllmann, M.; Richard, H.A. Simulation of fatigue crack propagation processes in arbitrary three-dimensional structures with the program system ADAPCRACK3D. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Fracture, Fatigue and Fracture, Honolulu, HI, USA, 3–7 December 2001; ORAL REFERENCE: ICF10081OR. Available online: https://www.icfweb.org/Proceedings/ICF10D/294/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Richard, H.A.; Sander, M. Fatigue Crack Growth; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibblee, K. 3D-Risswachstum in Homogenen, Isotropen Sowie Funktional Gradierten Strukturen; Fortschritt-Bericht VDI, Reihe 18: Mechanik/Bruchmechanik Nr. 350; VDI-Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, P.; Gomez, M.; Anderson, W. A rational analytic theory of fatigue. Trend Eng. 1961, 13, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, P.; Erdogan, F. A critical analysis of crack propagation laws. J. Basic Eng. Trans. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 1963, 85, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.