Suppression of Sound by Polyurethane Mats in Ventilation Ducts—A Study with a Laboratory Model Setup

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

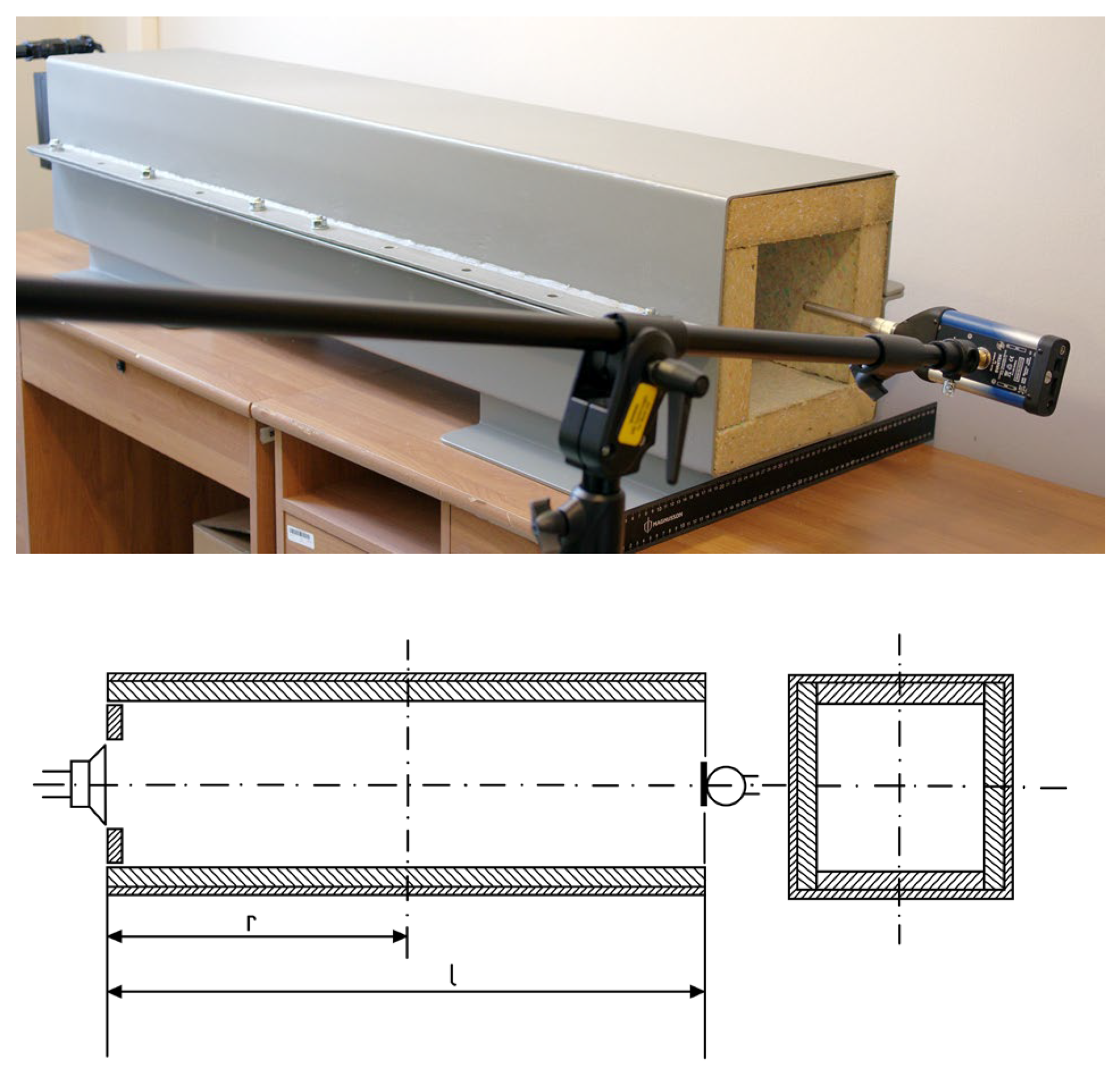

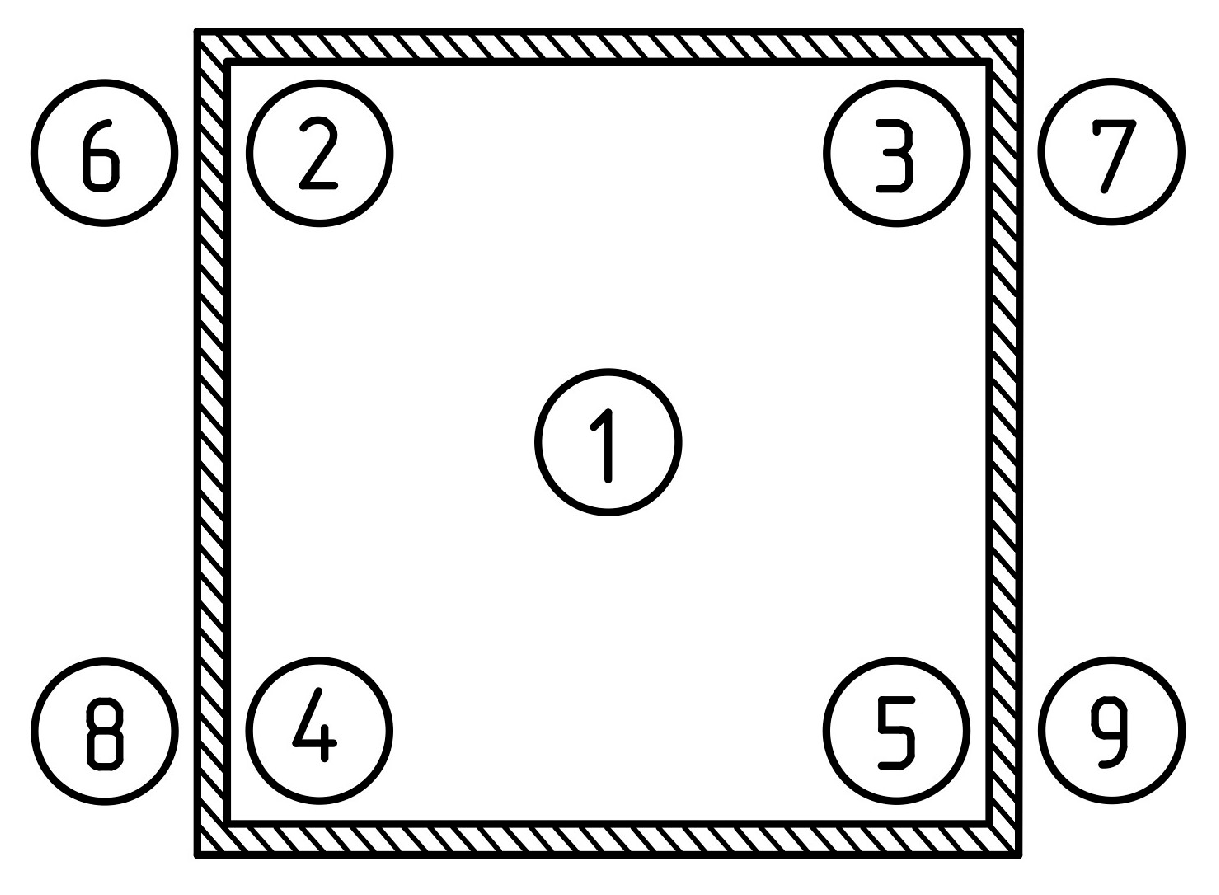

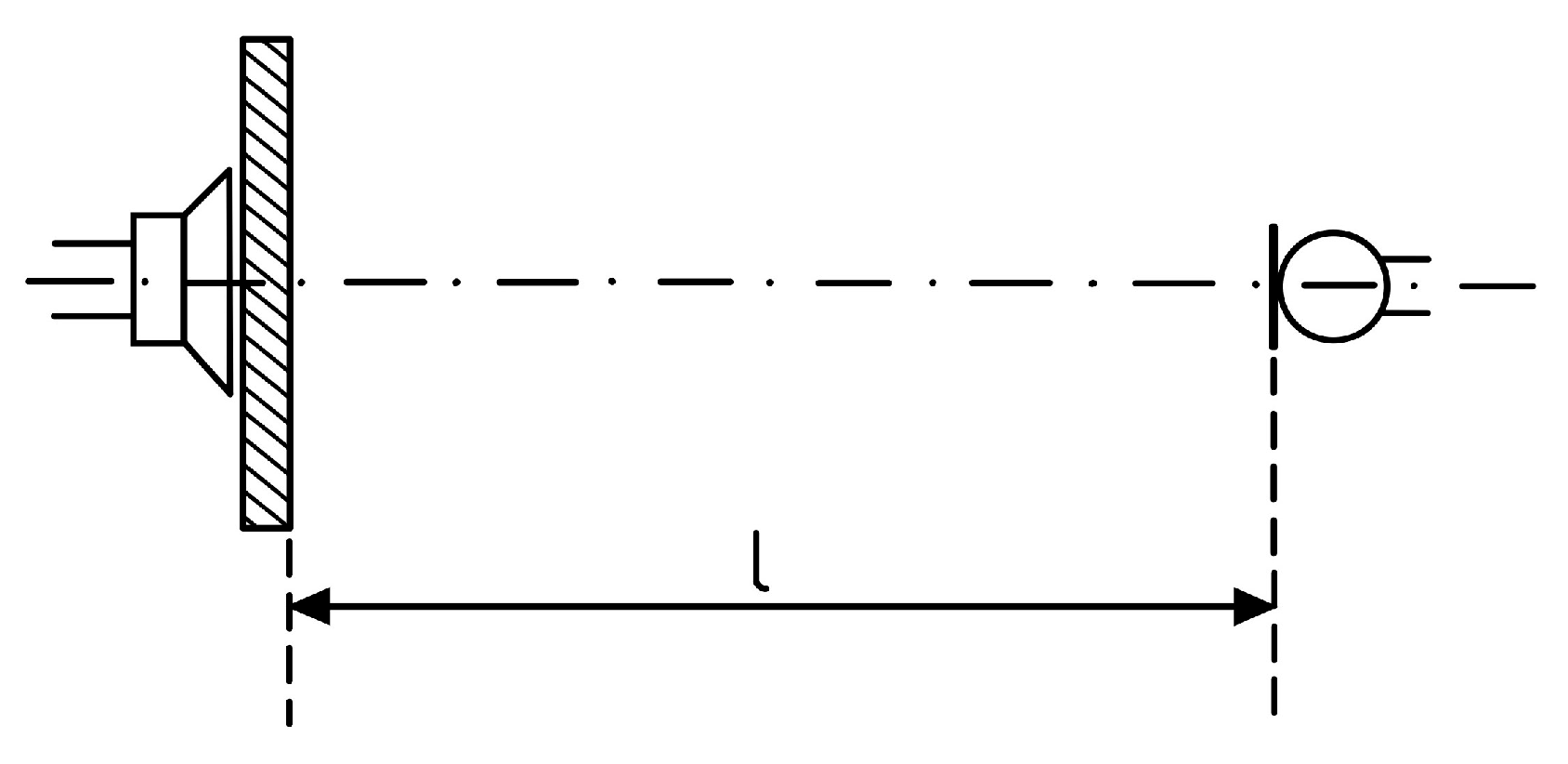

2.2. Apparatus and Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

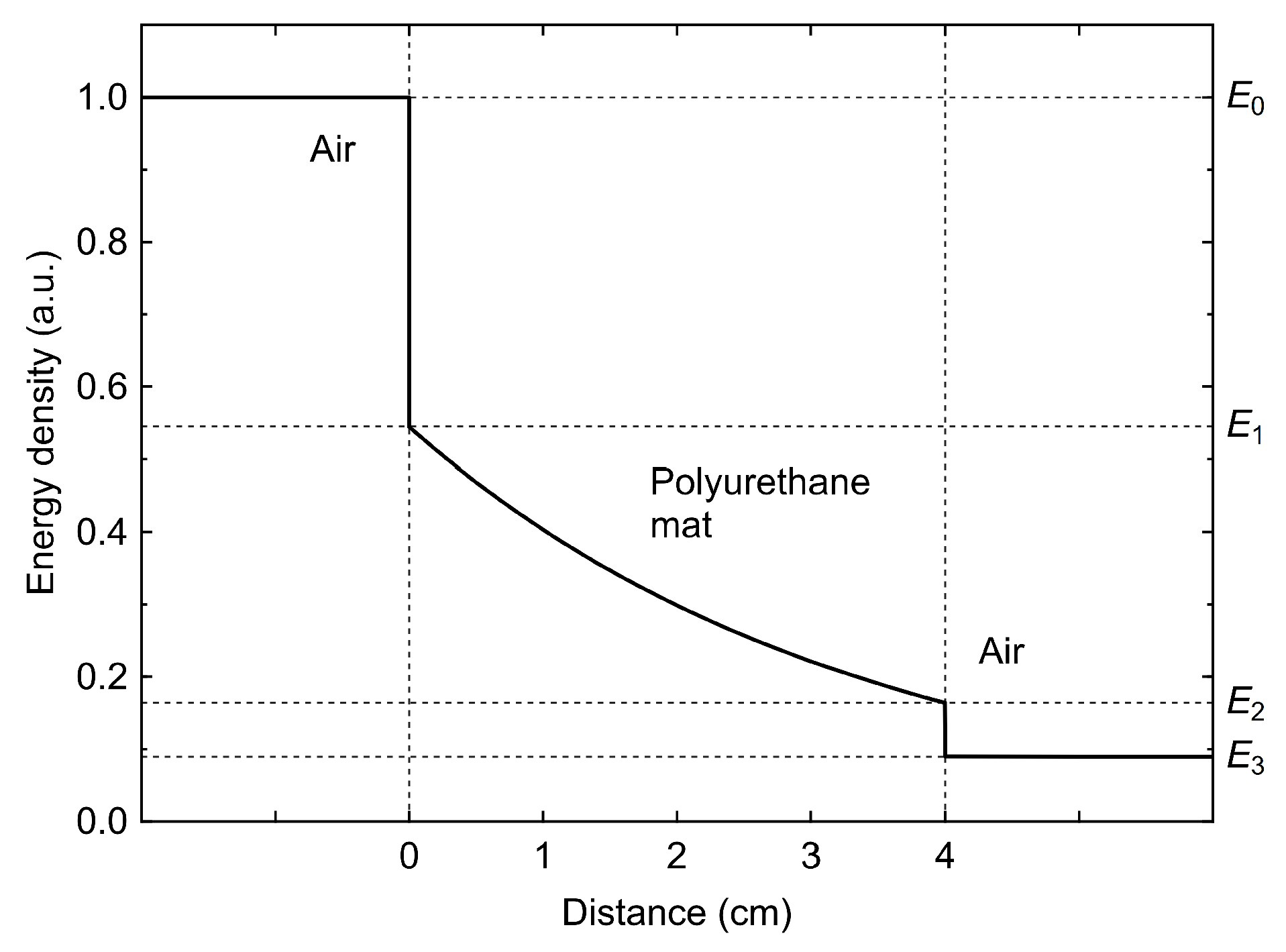

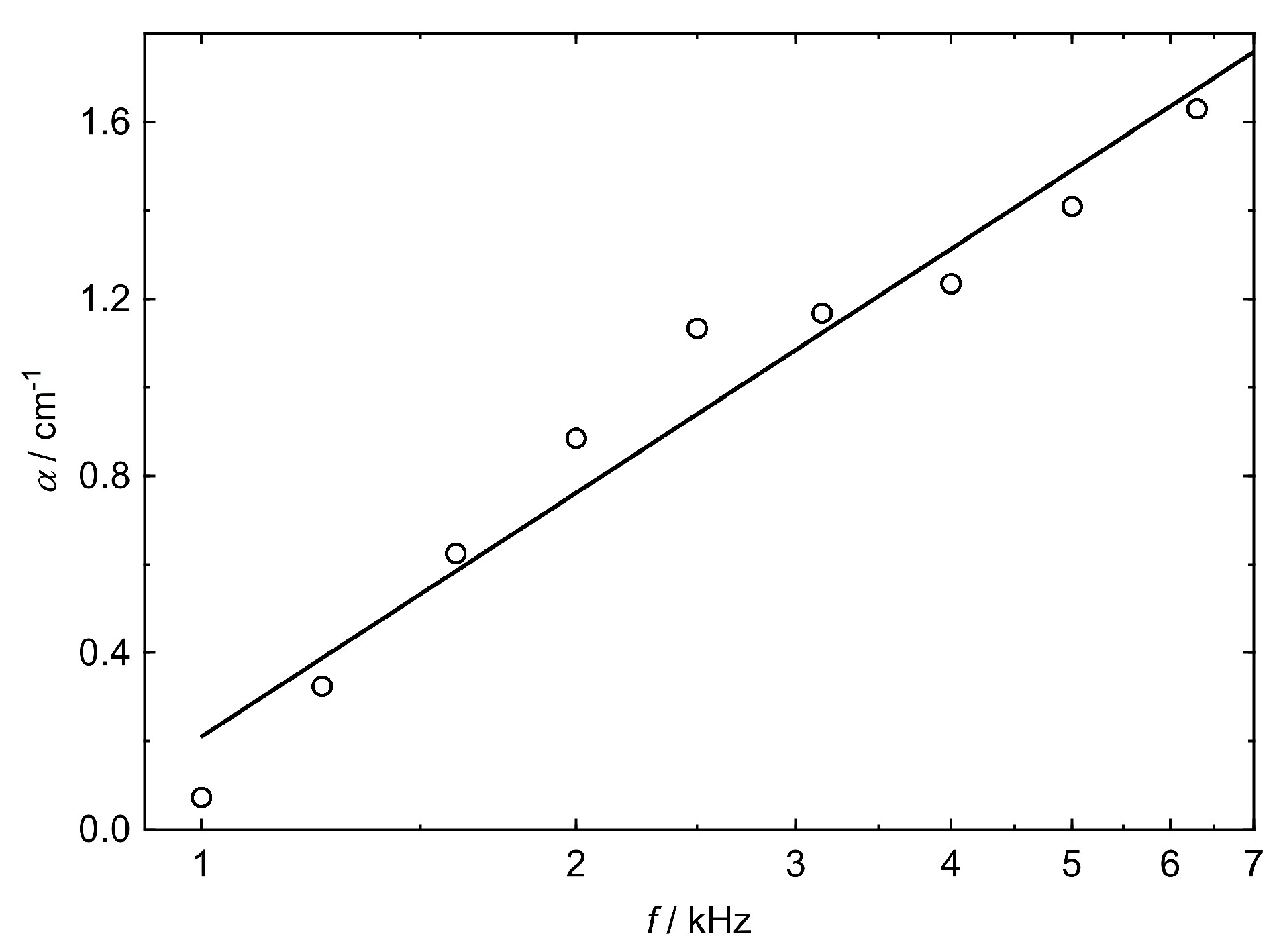

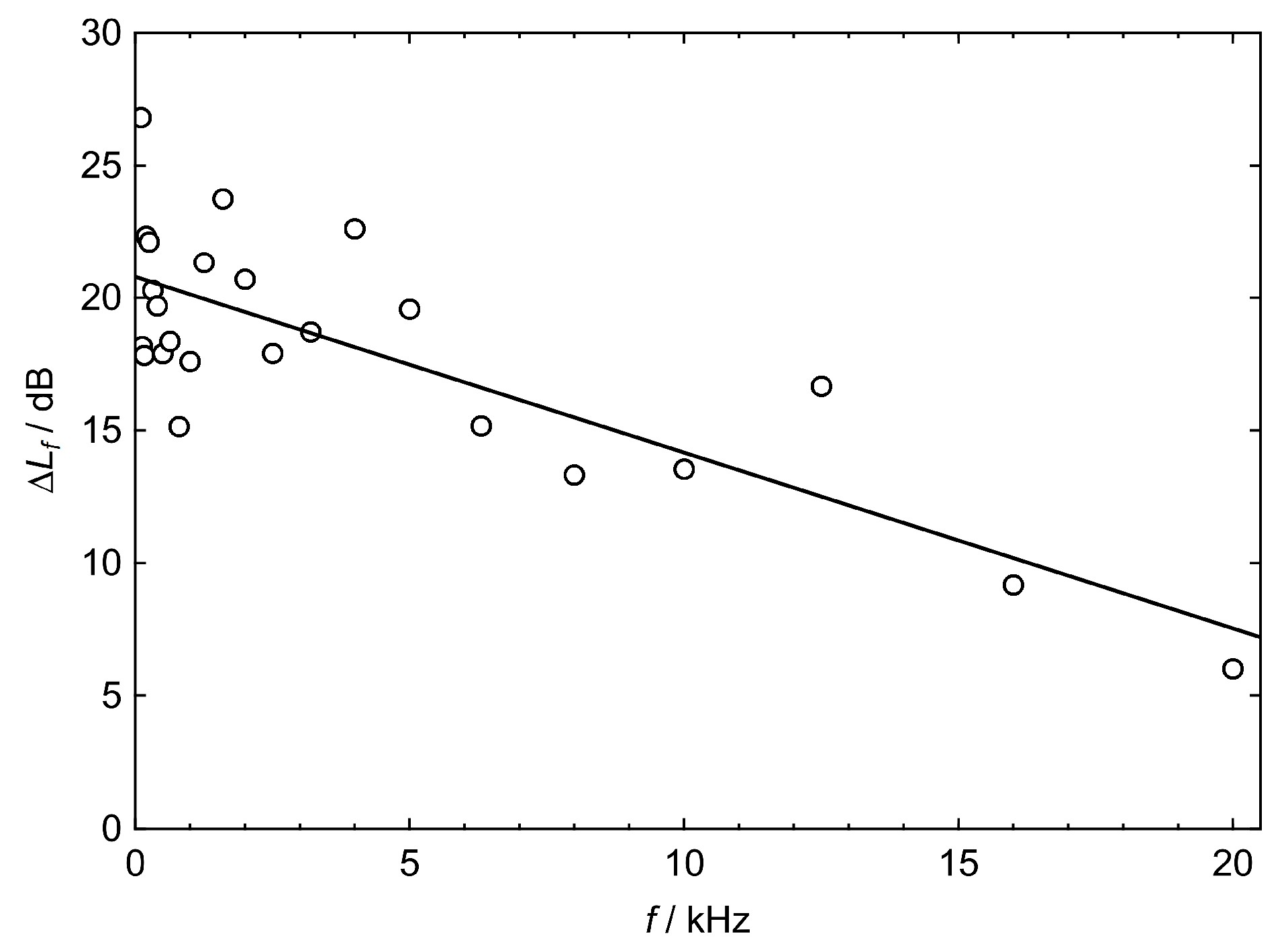

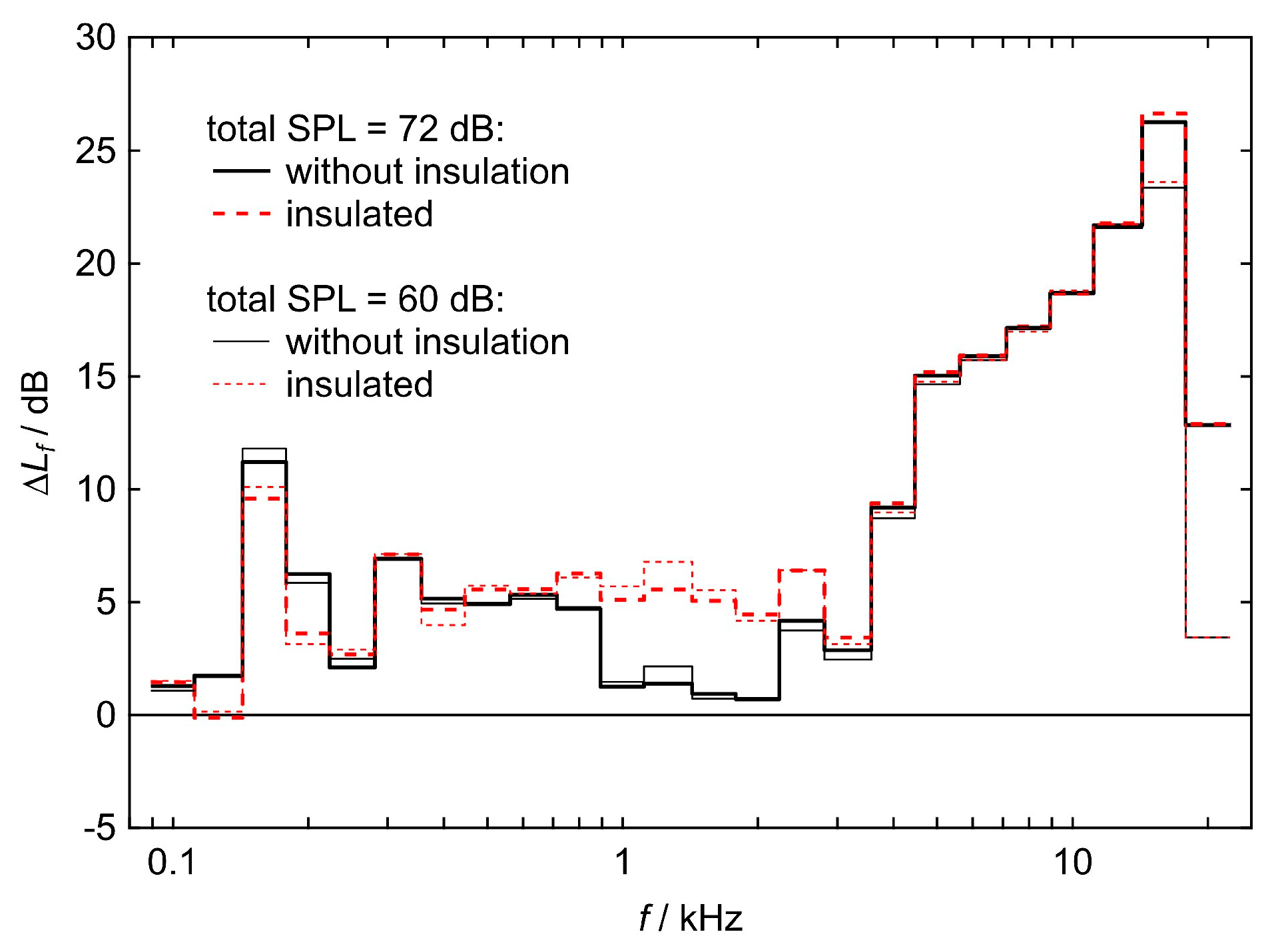

3.1. Assessment of the Attenuation Coefficient of a PUR Mat

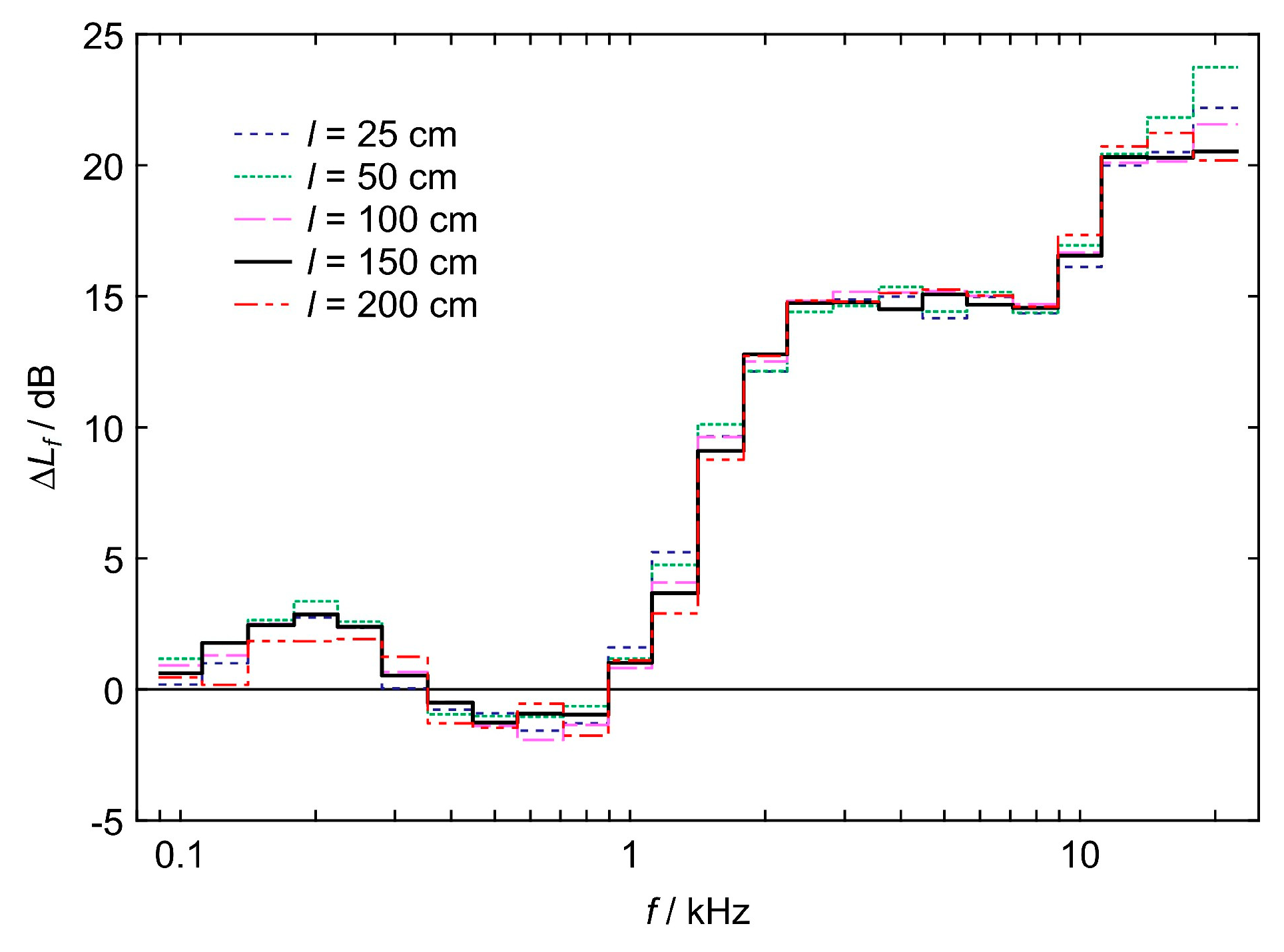

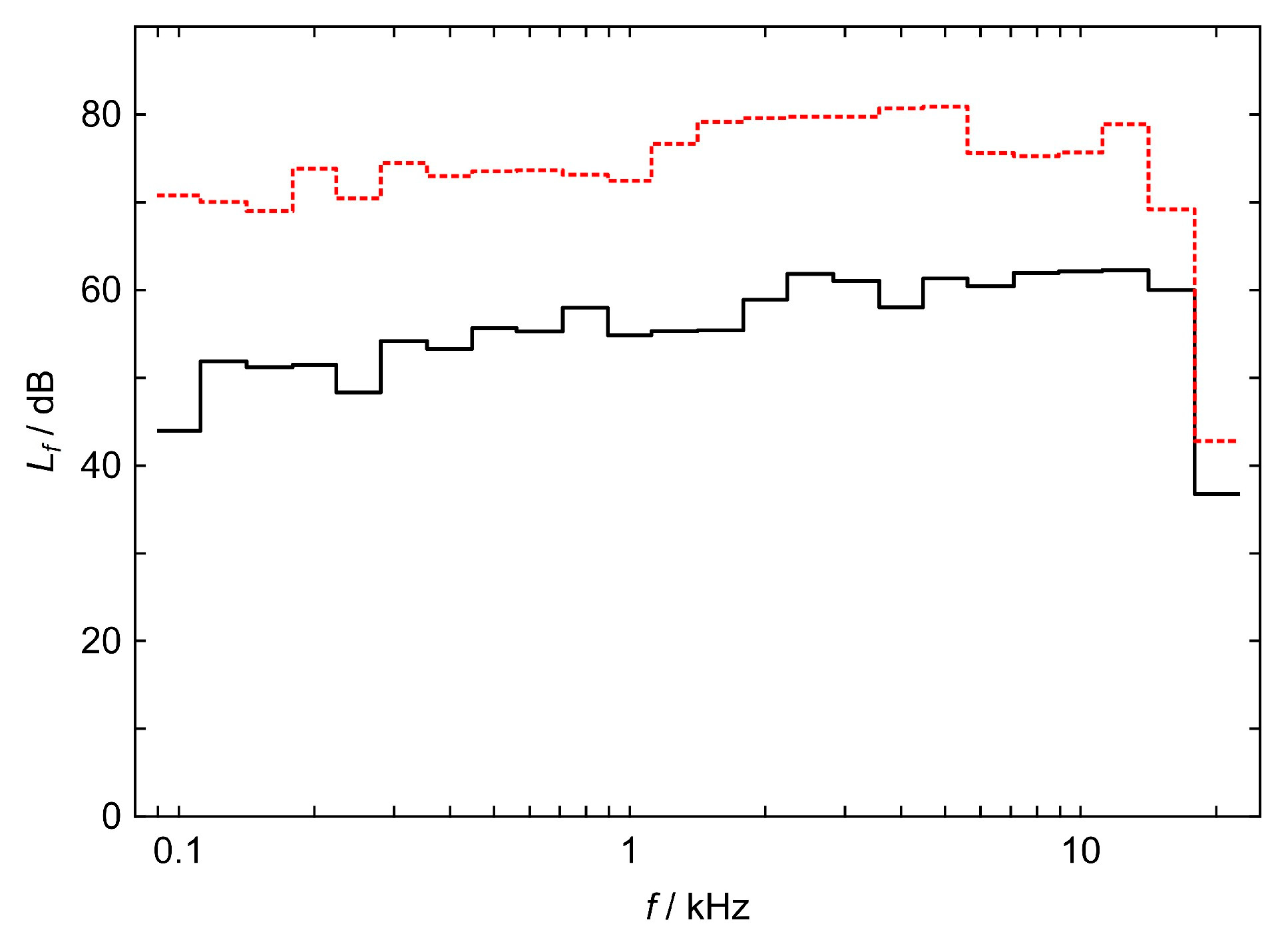

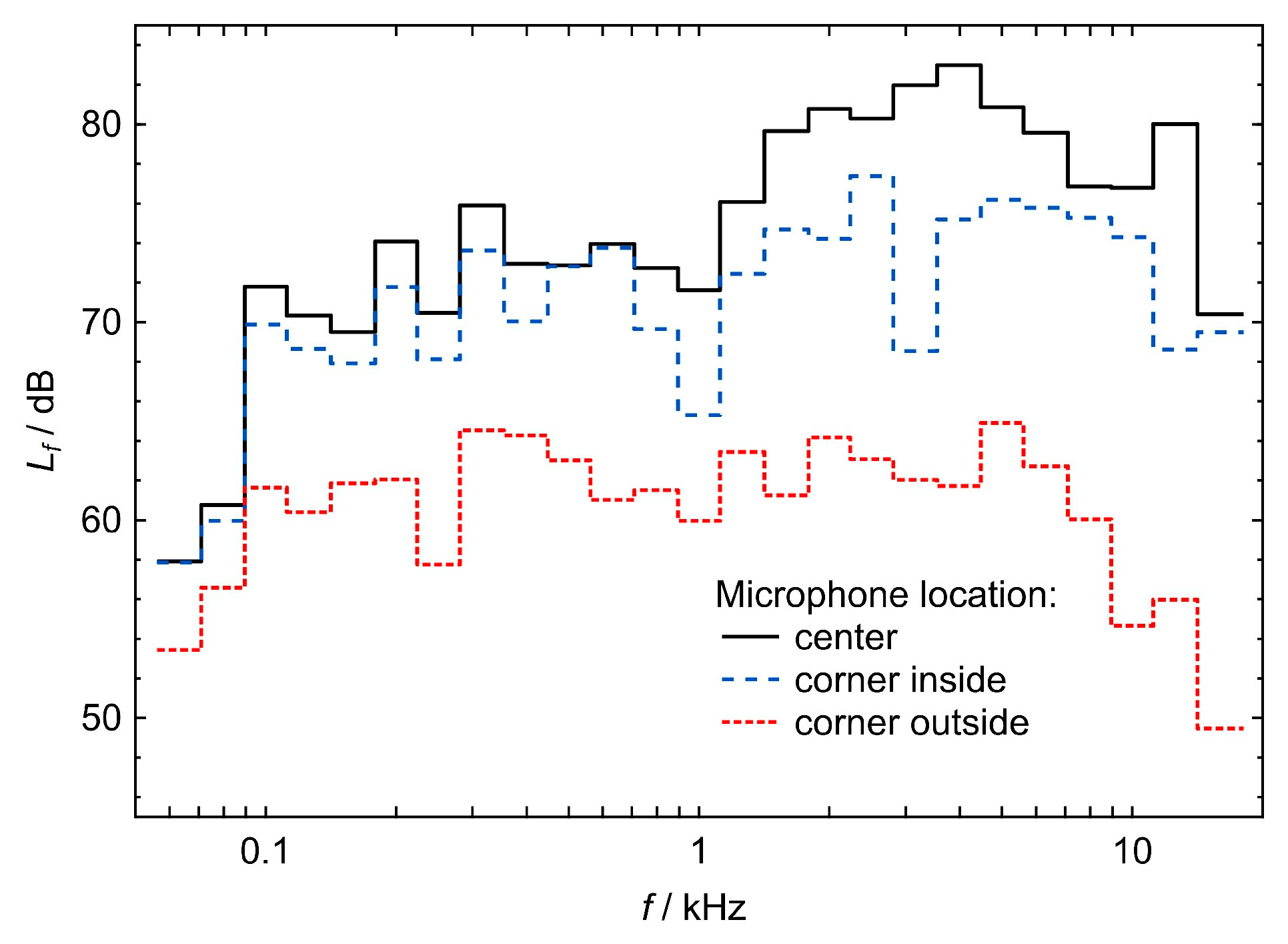

3.2. Empirical Characteristics of the Acoustic Beam Propagating Through the Model Ventilation Duct

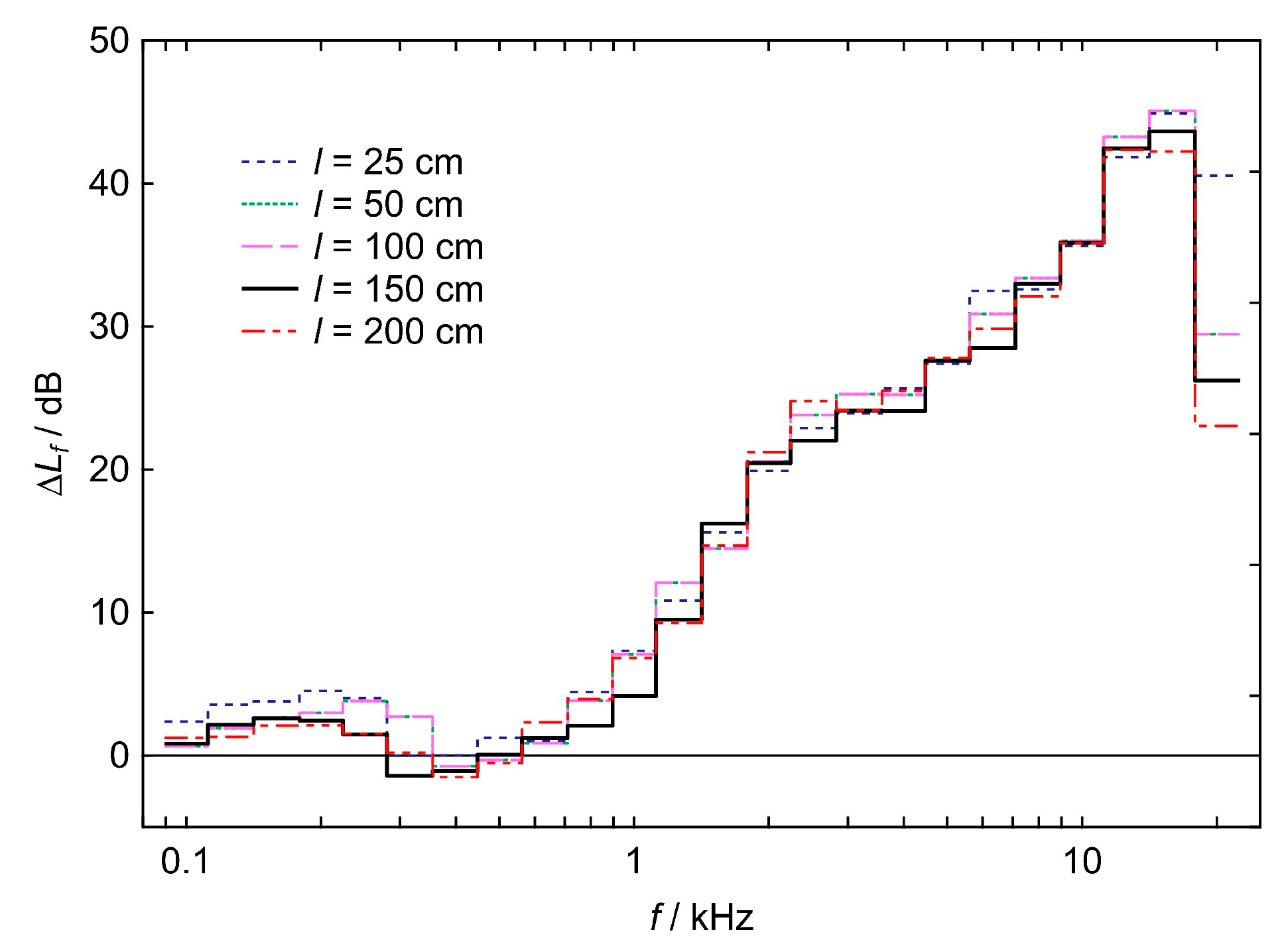

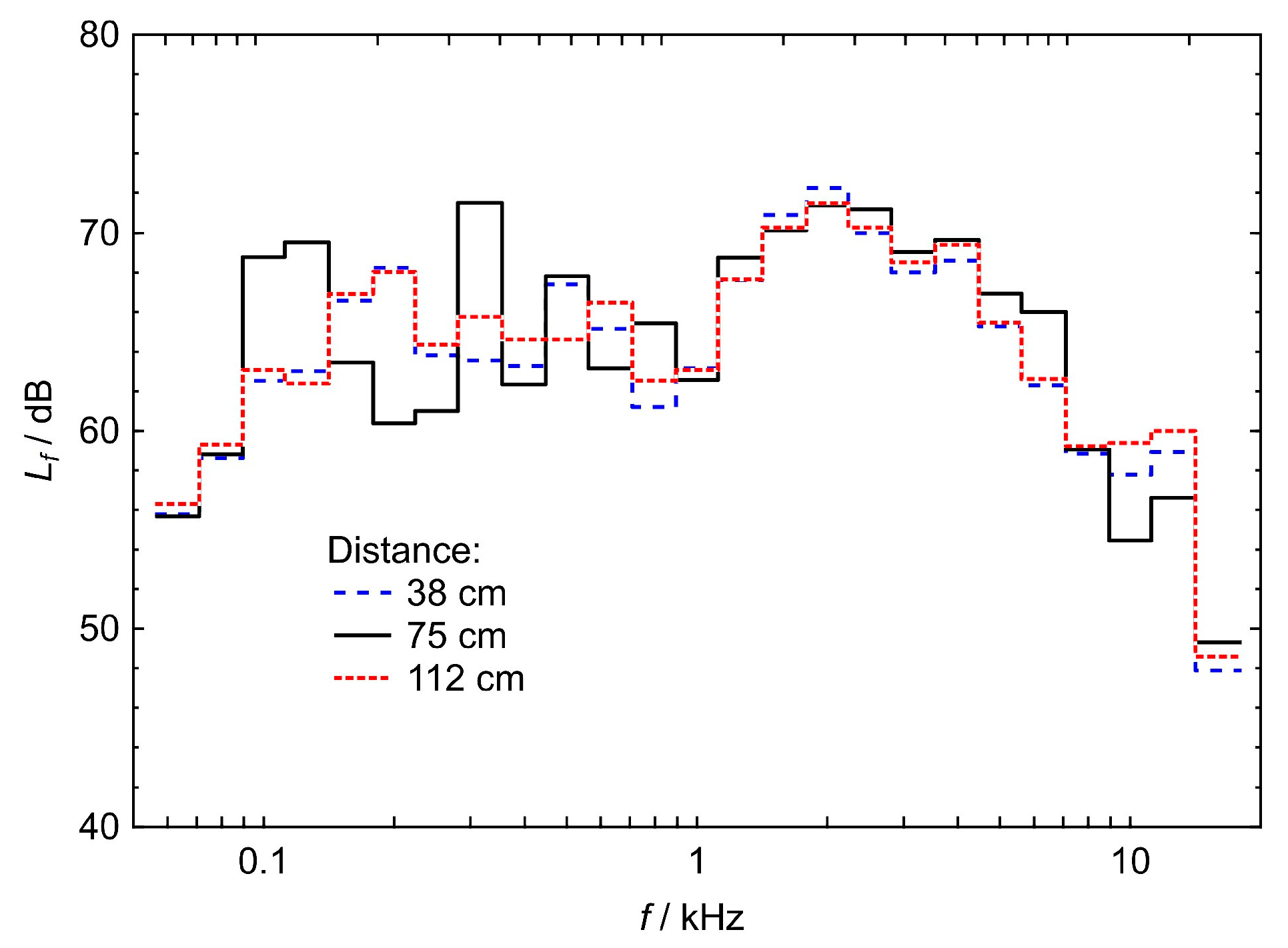

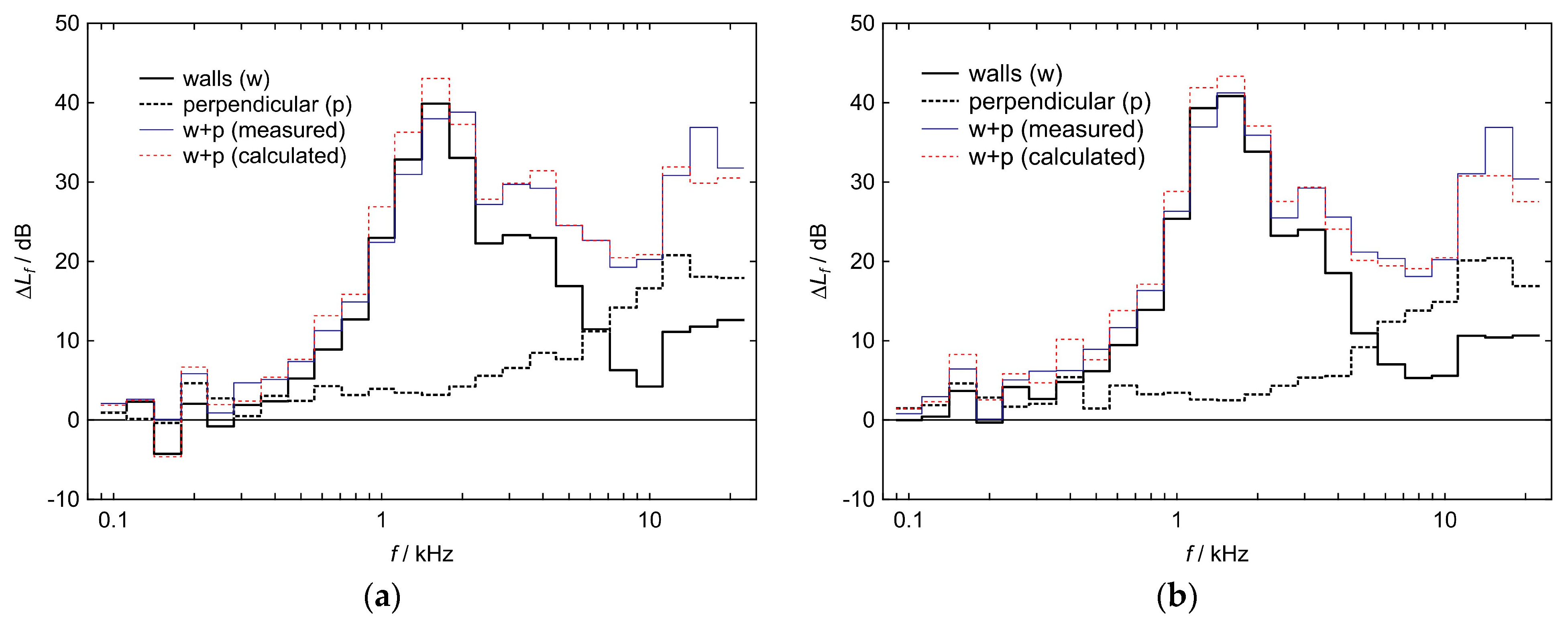

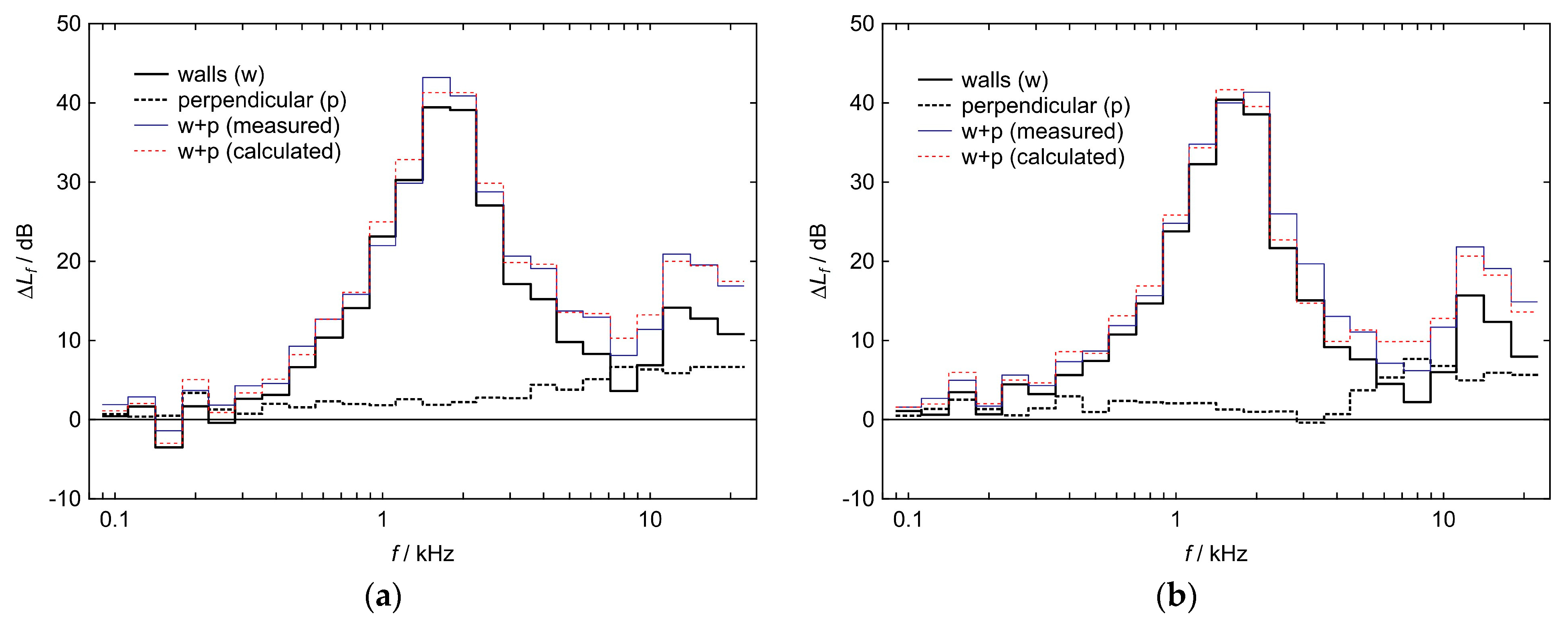

3.3. Suppression of Sound by a PUR Mat Perpendicular to the Longitudinal Axis of the Model Ventilation Duct

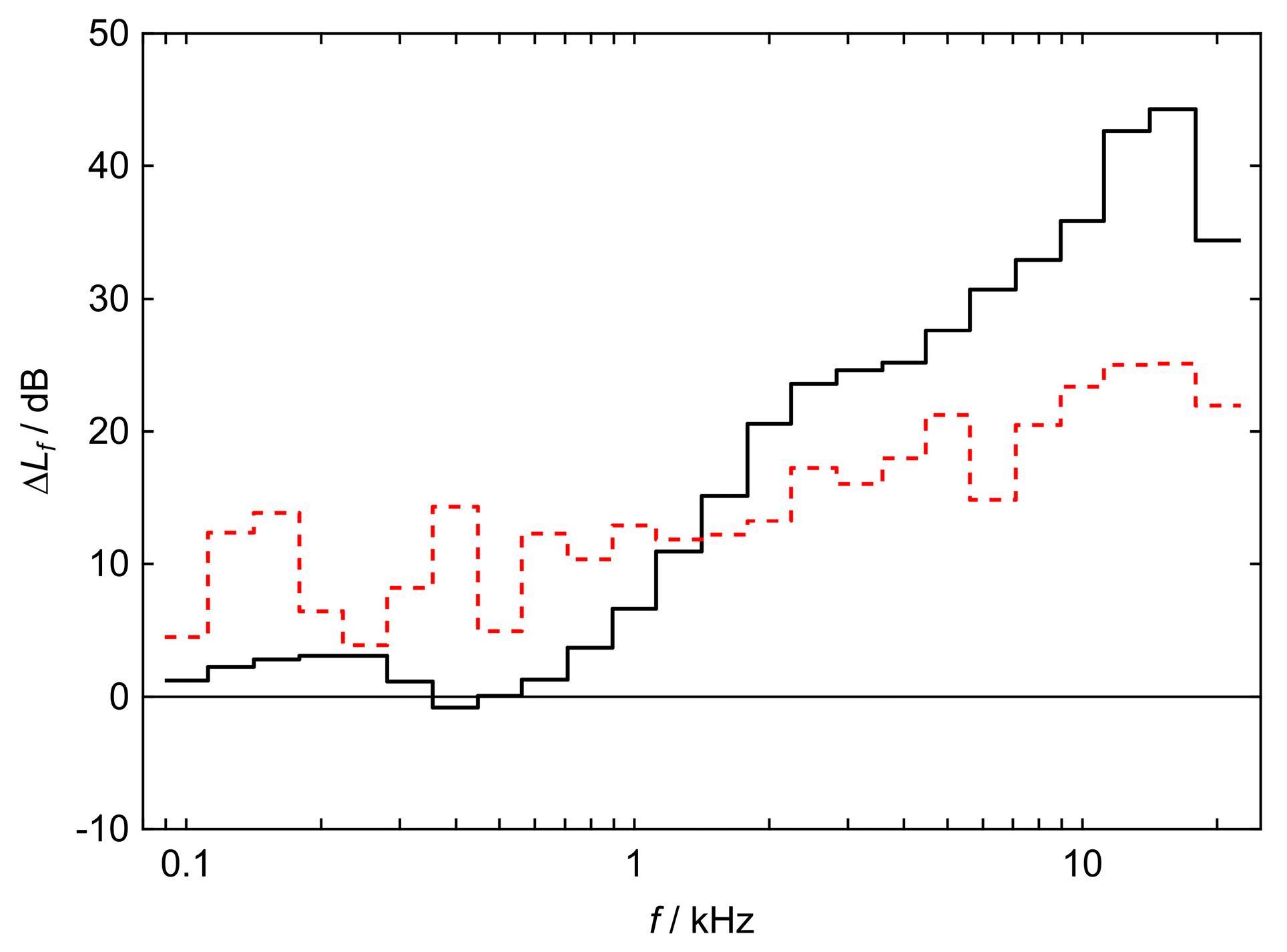

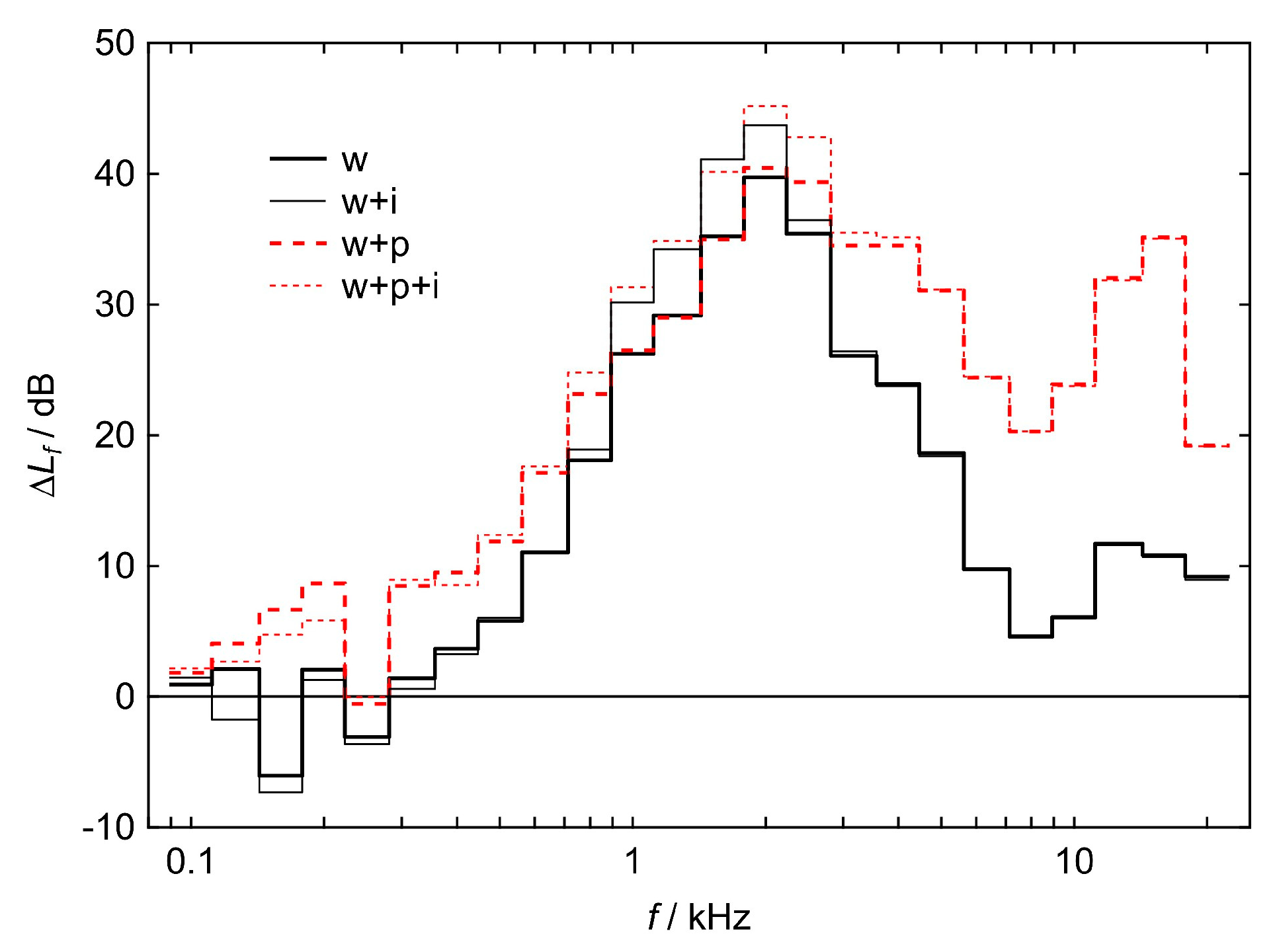

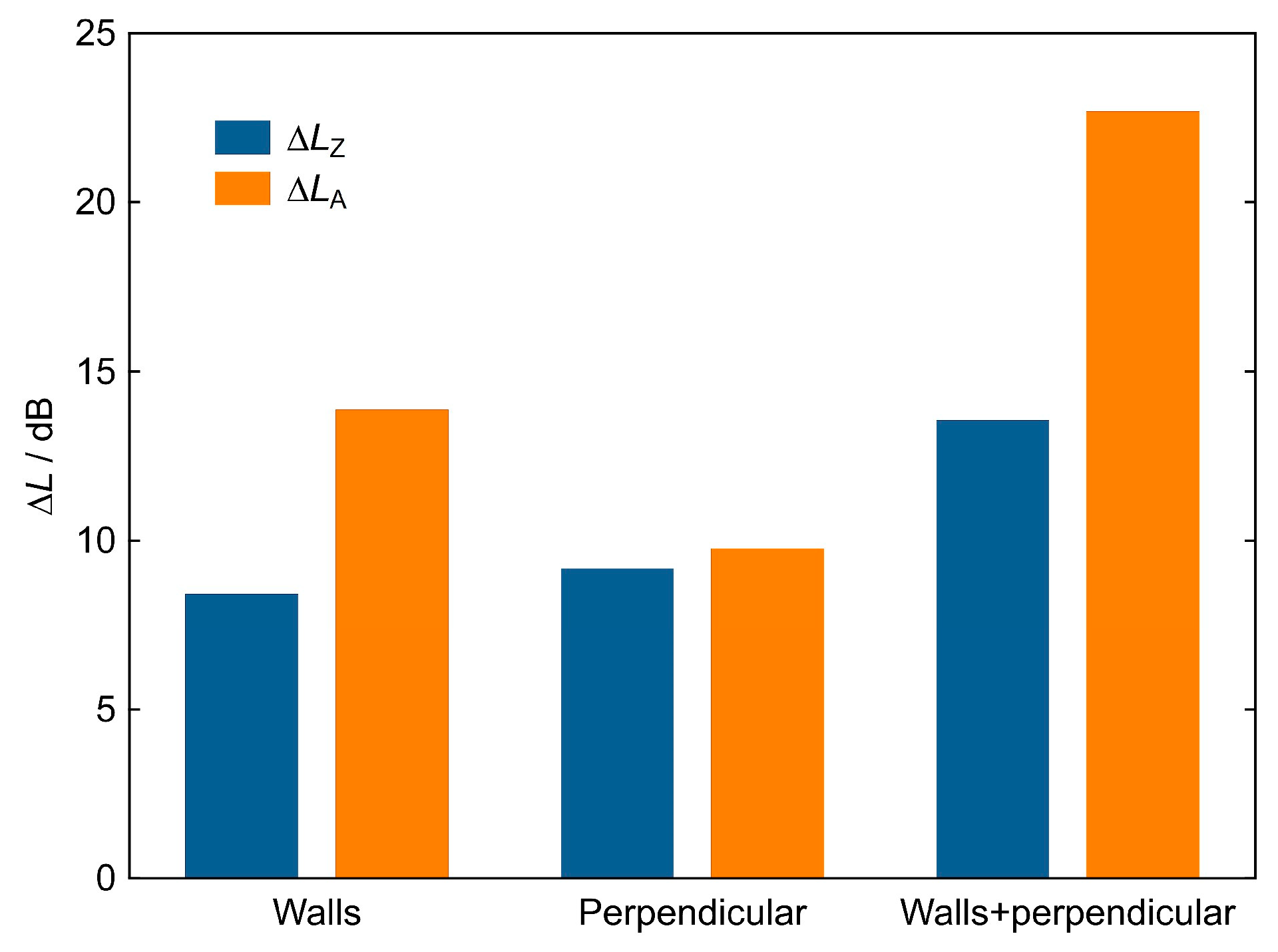

3.4. Suppression of Sound by Polyurethane Mats in Various Configurations in the Model Ventilation Duct

- Only the inner walls covered (referred to as “walls” from now on);

- The mat perpendicular to the tube longitudinal axis, fixed at a distance of r = 75 cm from the speaker (referred to as “perpendicular”);

- The mats were both on the walls and perpendicular (“walls + perpendicular”).

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ISO 17497-2:2012; Acoustics—Measurement of Sound Scattering Properties—Part 2: Measurement of the Directional Diffusion Coefficient in a Free Field. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- PN-EN ISO 354:2005; Acoustics—Measurement of Sound Absorption in a Reverberation Chamber. PKN: Warszawa, Poland, 2025. (In Polish)

- PN-EN ISO 10534-1:2004; Acoustics—Determination of Sound Absorption Coefficient and Acoustic Impedance in Impedance Tubes—Part 1: Standing Wave Coefficient Method. PKN: Warszawa, Poland, 2004. (In Polish)

- Herget, W. Insertion Loss, Sound Power Level and Pressure Measurements on Splitter Silencers; IBP-Report P-TA 31/2014; Fraunhofer-Institut für Bauphysik IBP: Stuttgart, Germany, 2014. Available online: https://www.alnor.com.pl/index/download/certyfikaty/tlumiki/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Tang, X.; Yan, X. Acoustic energy absorption properties of fibrous materials: A review. Compos.-A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 101, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, V.H.; Nguyen, T.V.; Nguyen, T.H.N.; Nguyen, M.T. Design of sound absorbers based on open-cell foams via microstructure-based modeling. Arch. Acoust. 2022, 47, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, C. Calculation of acoustic absorption in ducts with perforated liners. Appl. Acoust. 2015, 89, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, L.; Pan, J.; Yu, G. Sound absorption of a micro-perforated panel backed by an irregular-shaped cavity. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 127, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cao, G.; Zuo, G.; Liu, C.; Ma, F. Ultra-thin ventilated metasurface pipeline coating for broadband noise reduction. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 200, 111916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beranek, L.L. Noise Control. In Acoustics; Acoustic Society of America: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 332–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kemona, A.; Piotrowska, M. Polyurethane Recycling and Disposal: Methods and Prospects. Polymers 2020, 12, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignolo, G.; Malucelli, G.; Lorenzetti, A. Recycling of polyurethanes: Where we are and where we are going. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 1132–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JAG®. Flexible Rebound Polyurethane Foam. Available online: https://jag.pl/en/oferta/elastyczna-pianka-poliuretanowa-wtornie-spieniana-typ-r/ (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- IEC 61672-1; Electroacoustics—Sound Level Meters—Part 1: Specifications. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- IEC 60942; Electroacoustics—Sound Calibrators. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Turkiewicz, J. Określenie Fizycznego Współczynnika Pochłaniania Dźwięku Materiału Zgodnie z Normą ISO 10534-1; Raport AGH: Kraków, Poland, 2013; (Unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Beranek, L.L. Sound in enclosures. In Acoustics; Acoustic Society of America: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 285–331. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, R.; Antani, L.; Manoch, D. Source Directivity and Spatial Audio for Interactive Wave-Based Sound Propagation. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Auditory Display (ICAD–2014), New York, NY, USA, 22–25 June 2014; Available online: https://repository.gatech.edu/bitstreams/cd7afdd5-2700-434f-8d1e-c40650eccebe/download (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Pierre, R.; Maguire, D.J. The Impact of A-weighting Sound Pressure Level Measurements During the Evaluation of Noise Exposure, Noise-Con 2004, Baltimore, Maryland (USA). Available online: https://storeycountywindfarms.org/ref3_Impact_Sound_Pressure.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Fletcher, H.; Munson, W.A. Loudness, its definition, measurement and calculation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1933, 5, 82–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 226:2023; Acoustics—Normal Equal-Loudness-Level Contours. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

| Material | Typical Applications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyurethane foams (PU, open-cell PU foam) |

|

|

|

| Open-cell silicone foams |

|

|

|

| Open-cell metal foams (aluminum, nickel) |

|

|

|

| Fibrous materials (mineral wool, glass fiber, technical nonwovens) |

|

|

|

| Acoustic metamaterials/ “slow-sound” coatings |

|

|

|

| Type | Apparent Density, kg/m3 | Thickness, cm | Hardness (Min.), N/mm2 | Tensile Strength (Min.), kPa | Elongation at Break (Min.), % | Permanent Deformation (Max.), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-40 (PUT) | 40 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| R-220 (PUR) | 220 | 2 | 3400 | 300 | 60 | 15 |

| R-220 (PUR) | 220 | 4 | 3400 | 300 | 60 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nowacki, K.; Łakomy, K.; Kołodziejczyk, E.; Marczak, W. Suppression of Sound by Polyurethane Mats in Ventilation Ducts—A Study with a Laboratory Model Setup. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010385

Nowacki K, Łakomy K, Kołodziejczyk E, Marczak W. Suppression of Sound by Polyurethane Mats in Ventilation Ducts—A Study with a Laboratory Model Setup. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010385

Chicago/Turabian StyleNowacki, Krzysztof, Karolina Łakomy, Eliza Kołodziejczyk, and Wojciech Marczak. 2026. "Suppression of Sound by Polyurethane Mats in Ventilation Ducts—A Study with a Laboratory Model Setup" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010385

APA StyleNowacki, K., Łakomy, K., Kołodziejczyk, E., & Marczak, W. (2026). Suppression of Sound by Polyurethane Mats in Ventilation Ducts—A Study with a Laboratory Model Setup. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010385