Abstract

Nowadays, optimization methods are widely used to adjust controller parameters and tune their optimal values in order to enhance the efficiency and performance of dynamic systems. In this study, the parameters of a linear Proportional–Integral (PI) controller were optimized by using five different optimization algorithms, such as Artificial Tree Algorithm (ATA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Differential Evolution Algorithm (DEA), Constrained Multi-Objective State Transition Algorithm (CMOSTA), and Adaptive Fire Forest Optimization (AFFO). The optimized controllers were implemented in real time for temperature control of a Heat-flow System (HFS) under various step and time-varying reference signals. In addition, the Ziegler–Nichols (Z–N) method was also applied to the system as a benchmark to compare the temperature tracking performance of the proposed optimization methods. To further evaluate the performance of each optimization algorithm, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values were calculated, and improvement ratios were obtained. The experimental results showed that the proposed optimization methods provided more successful reference tracking and enhanced controller performance as well.

1. Introduction

Temperature control is a fundamental requirement in many industrial and laboratory processes, including heating furnaces, chemical reactors, drying systems, heat exchangers, and climate-control units. In such applications, poor temperature control may lead not only to increased energy consumption and product quality degradation but also to potential safety risks. Consequently, there is a continuous demand for control strategies that can ensure accurate reference tracking, minimal overshoot, and robust behavior under uncertainty and time delay [1,2]. As examples of these strategies, the PI and Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID)-based controllers have remained the most widely used solutions in practice due to their simple structure, ease of implementation, and compatibility with existing industrial hardware [3,4,5,6,7]. However, their performance is highly sensitive to the choice of gain parameters, and manual or heuristic tuning is often insufficient for processes with strong nonlinearities, large time constants, or transport delays typical of thermal systems. Classical tuning rules such as Z–N and Cohen–Coon offer simple formulas based on step response or ultimate gain tests, but they were originally derived under restrictive assumptions (e.g., low-order linear models) and often yield aggressive responses with significant overshoot in slow temperature processes. For this reason, there has been growing interest in optimization-based tuning, where controller gains are obtained by minimizing a performance index such as the Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error (ITAE), Integral of Absolute Error (IAE), or a multi-objective criterion balancing tracking and energy consumption. In the literature, recent works have applied metaheuristic algorithms to tune the PI/PID controller parameters for power systems, thermal plants, and multivariable processes, showing that these approaches can outperform classical rules in terms of settling time, overshoot, and robustness [8,9,10]. For example, PSO has been widely used to tune PI/PID controller parameters and to enhance system identification and diagnostic techniques, enabling improved performance and early detection of anomalies in various industrial processes [11,12,13,14,15,16].

Parallel to these developments, the last 10 years have seen a rapid evolution of nature-inspired metaheuristics, including improved variants of the ATA, state transition algorithms, and adaptive and fire or forest fire-based optimization methods. Improved ATA designs, such as multi-population and feedback-based versions, have introduced new branch update operators, competition mechanisms between subpopulations, and hybridization with other search strategies to enhance convergence speed and solution quality [17]. Similarly, the state transition algorithm has been extended to constrained multi-objective optimization; recent CMOSTA methods with adaptive bidirectional coevolution have demonstrated strong performance on complex engineering problems, where they maintain diversity while efficiently exploring feasible Pareto fronts [18,19].

Moreover, forest fire-inspired algorithms have also gained attention for tuning the controller parameters. The AFFO method and its related variants have been proposed for routing and energy efficiency in wireless sensor networks, and for modeling or simulating forest-fire spreading, benefiting from their strong global search capability and ability to escape local minima [20,21]. In parallel, the DE method continues to be a benchmark global optimizer, and recent studies have introduced constraint-handling, multitasking, or hybrid strategies to further improve its robustness and performance on high-dimensional or uncertain problems [22,23,24,25,26,27]. Despite this rich algorithmic development, most of these methods are still evaluated primarily on benchmark test functions or static optimization problems; their systematic comparison on real-time control tasks, especially for slow thermal processes with time delay, has been relatively limited.

In this paper, the controller parameters of an HFS have been obtained by using ATA, PSO, DEA, CMOSTA, and AFFO optimization methods, and then tested in a real-time experimental setup. The obtained results have been compared with the Z–N method and analyzed in detail in terms of rise time, reference tracking success and improvement rate, etc. In addition, the reference tracking success of all the optimization methods, compared to Z–N, has also been analyzed numerically by calculating their MAE values by using real-time data, as well. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed optimization methods provide superior reference tracking performance compared to the classical Z–N method and significantly enhance the performance of the linear controller.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Modeling and Experimental Setup

The total thermodynamic model of the HFS includes specific optimization models and experiments. Using a heater and a fan, the air temperature is measured from three temperature sensors at selected points on a duct, a model is obtained from the response of the system, and a PI controller is designed to control the system. By applying an analog step signal to the HFS, the temperature changes at each sensor can be observed. The following formula can be used for the thermodynamic model of the system [28,29]:

where is the temperature at the nth sensor, is the voltage applied to the heater, is the voltage applied to the fan, is the ambient temperature, and is the distance of the nth sensor to the heater [28]. The operating curves of the system must be obtained from the measurements from each sensor. The first-order model of the system to be derived in this way should be approximately written as follows [28,29]:

where and represent the time constant and steady state gain for the nth sensor [28,29]. Another issue is temperature control. The temperature of the room is maintained using an on–off control and a compensator. The voltage–temperature transfer function of the HFS can be written as given below [28,29].

where and is the time constant of the system. The PI controller equation for a feedback control system that will control the temperature at the first sensor of the system and reset the steady-state error is as follows [28,29]:

where is the control signal that is applied to the system, and are the controller gains, is the reference temperature signal, and is the measured temperature signal, respectively. If this expression is used in a closed-loop system, the following relation is obtained as given below [28,29]:

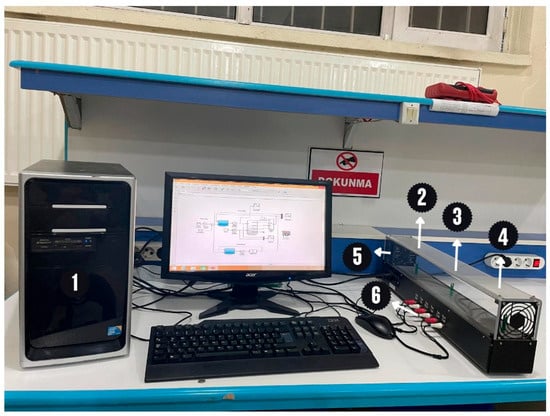

where is the system gain. Moreover, Figure 1 presents the hardware components included in our experimental system. First of all, component 1 corresponds to the main PC of the system, while components 2, 3, and 4 denote the temperature sensors. Component 5 represents the blower unit, and component 6 refers to the front panel connectors, which include the sensor outputs as well as the heater and fan control inputs. Furthermore, the experimental HFS used to evaluate the performance of each optimization algorithm, along with its technical specifications, is summarized in Table 1. In this study, Sensor 1, denoted as component 2, was used as the primary measurement point for temperature feedback.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup used in real-time experiments [28].

Table 1.

The principal parameters associated with the Heat-Flow System [28].

2.2. Methods

Metaheuristic optimization techniques have gained considerable attention in the literature due to their robustness and flexibility. These algorithms are well-suited for complex, nonlinear, and multimodal optimization problems, where classical gradient-based approaches may fail to identify global optima. For this reason, several metaheuristic optimization techniques, including PSO, ATA, CMOSTA, DEA, and AFFO, are introduced and applied to achieve temperature control of a heat-flow system (HFS) by optimizing the parameters of a PI controller in this section.

2.2.1. Particle Swarm Optimization

PSO is an optimization algorithm based on swarm intelligence, developed by Kennedy and Eberhart in 1995 [30]. It mimics the collective movement logic of real-life bird flocks or fish schools. It is essentially inspired by the social behavior of flocks of birds or fish communities as they search for the best food source [31]. A large number of “particles” move in the search area, updating their positions according to their experiences and the best individual in the swarm [2,14]. This method does not require derivative knowledge; it works even if the system model is not clear. The probability of getting stuck in a local minimum is lower than with other algorithms. It is suitable for parallel processing and gives fast results. Each particle has a position (the solution) and a speed (how that solution will change). Speed determines how much and in what direction this position changes. Each particle remembers the best solution it has ever reached (its own best). The best solution in the swarm is known by all particles, and others tend towards this solution [31,32,33]. Each particle has a two-dimensional vector [11,12] as given below.

Besides, the velocity update can be written as given below [11,13,34,35]:

where pbest (personal best) represents the best position reached by the particle, gbest (global best) represents the best position reached by all particles, w represents the inertia weight operated between 0.7 → 0.4, represent the cognitive and social coefficients, and and represent the random numbers in the range [0, 1] [35,36,37,38]. Also, the position update can be written as in (8) [36,37].

At each iteration, particles update their positions and velocities according to these equations, and the best values are continuously refined until convergence.

2.2.2. Constrained Multi-Objective State Transition Algorithm

The CMOSTA focuses on determining controller parameters using a dynamic model of the heat-flow system. A mathematical model of the system is obtained or estimated from an experimental data set. Using the obtained model, the controller parameters are adjusted to optimize a certain performance criterion. Then, the obtained parameters are applied to the real system or tested by simulation. If necessary, the optimization is repeated [39].

The CMOSTA first generates an initial solution candidate randomly or at certain intervals. Each solution is evaluated by a multi-objective fitness function [19]. In the CMOSTA method, firstly, the set of Pareto-optimal solutions is found as [35,36]:

Here, x is the decision vector, m is the objective, p is the inequality, q is the equality constraint. After that, one can define a feasible region as given below [18,19,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Moreover, defining constraint violation functions as [19]:

where

Here, balances the equality violations. Also, this state implies that the solution vector can be defined as . Additionally, the population at each iteration can be obtained as , and At keeps Pareto front approximations.

Defining two solutions as x and y, one can obtain the following possibilities [19]:

- If x is feasible and y infeasible; then .

- If both are feasible, usual Pareto dominance satisfies with strict inequality holding for at least one .

- If both are infeasible, the solution with smaller total violation dominates as given below:

- Remove any y ∈ At for which x’ dominates y.

- If no member of At dominates x’, add x’.

- To limit archive size, apply truncation based on diversity metric (crowding distance or grid density).

To maintain diversity in the objective space, the following expression can be written [18,19,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]:

For this study, in the CMOSTA algorithm, the rotation factor was set to 1.4, the translation factor to 1.0, the expansion factor to 1.6, and the axesion factor to 1. In addition, the coevolution mechanism was applied with five coevolution cycles per iteration as well.

2.2.3. Artificial Tree Algorithm

The Artificial Tree Algorithm (ATA) is a nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization method that mimics the natural growth and reproduction processes of real trees. The algorithm imitates how trunks, branches, and leaves expand and develop in response to environmental conditions. In this analogy, obtaining the optimal solution within a search space corresponds to a tree growing toward the most favorable light, water, or nutrient source. Thus, ATA searches for increasingly better solutions by modeling how real trees adapt and restructure themselves in nature. In heat-flow systems, the relationship between controller parameters and system performance is typically modeled using historical operational data or simulation results [17]. This model allows prediction of appropriate controller parameter values under new or unseen operating conditions. As the system is operated with different controller parameter sets, error signals and performance indicators are collected. These data form input–output pairs where the inputs may include variables such as temperature, flow rate, or previously applied control parameters, while the outputs contain corresponding performance measurements. Based on the collected dataset, a decision-tree model is constructed. Each branch of the tree represents a classification or a regression rule that describes how the system behaves under different parameter combinations [42]. When a new system state is observed, the model traverses the decision tree and recommends the most suitable PI controller parameters corresponding to the given input variables.

For a general optimization problem, the following formulation is considered [35,43]:

subject to:

In ATA, the solution space is treated as a forest, each individual solution is represented as an artificial tree, and the fitness of a tree is evaluated by the objective function . The algorithm begins with a main stem (root node), which represents an initial pair of randomly generated solutions. For a PI controller design, an initial solution can be expressed as given in (6) [1,44].

Over time, the artificial tree grows by branching. Each new branch corresponds to a newly generated solution, obtained by applying a deviation from its parent solution. This branching mechanism enables exploration of new regions of the search space [31]. A general branching (growth) operator is described by [42,43]:

where is a small step-size parameter and is a standard Gaussian random variable [45]. To enable learning from the best solution, ATA updates solutions by moving them toward the current global best [42,43]:

Here, is the current solution, is the best solution found so far, and is the learning rate, taken as 0.2. Finally, similarly to the natural dispersal of seeds, ATA introduces new candidate solutions by randomly planting trees in the feasible region [42,43]:

where ensuring broad global exploration. For the ATA algorithm, the branch factor was set to 3; the competition coefficient to 0.4; the local search probability to 0.3; and the seedling regeneration rate to 0.15. In this study, the maximum number of iterations was determined as 150, and the population size was taken as 40 artificial trees.

2.2.4. Differential Evolution Algorithm Optimization Method

The Differential Evolution Algorithm (DEA) is an evolutionary optimization algorithm capable of performing global optimization without requiring explicit mathematical models or analytical gradients. It is widely used in complex and nonlinear systems, particularly in parameter tuning problems. DEA is well-suited for optimizing controller parameters in delayed and dynamic environments such as heat-flow systems, based on either experimental data or simulation results [27]. DEA mimics natural evolutionary processes. Its main idea is to exploit the differences between existing high-quality solutions to generate new, potentially better candidate solutions. A population of random parameter vectors is first initialized within the parameter space. The system is then simulated, or data are collected from the real plant. A performance (cost) function is defined to evaluate controller quality. Differential Evolution improves individuals in the population iteratively by applying mutation, crossover, and selection.

The parameter set that minimizes the performance function is ultimately chosen as the optimal controller [24,46]. An individual in the population can be represented as given in (6) [24,47,48]. For each target vector , three distinct individuals from the population are randomly selected. A mutant vector is generated as follows [22,23,24,46,47,48,49,50]:

where are randomly chosen and mutually different individuals, is the mutation (differential weight) factor and set to 0.78, and is the mutant vector, as well.

For crossover, the trial vector is generated by mixing components of the target vector and the mutant vector according to a crossover probability [22,23,24,36,46,47,48,49,50]:

where is the crossover probability to 0.8, , and ensures that at least one component is always taken from The population size consists of 40 individuals as well.

Finally, DEA applies a greedy selection to determine the next-generation individual [22,23,24,46,47,48,49,50]:

This ensures that the population never deteriorates from one generation to the next.

2.2.5. Adaptive Forest Fire Algorithm Optimization Method

The Adaptive Forest Fire Optimization (AFFO) method analyzes the incremental functional responses of a system such as temperature variations in heat-flow processes to identify and model its dynamic characteristics. By examining the functional growth curve of the system output, the AFFO method extracts essential dynamic parameters such as delay time and time constant. Using experimental data, these dynamic characteristics are estimated and used for controller design [20]. AFFO is inspired by the natural forest fire cycle. Although forest fires appear destructive, they ultimately promote long-term ecological renewal. This concept is translated into optimization as follows: eliminate poor solutions (“burned trees”), intensify the spread of promising solutions (“fire spread”), and explore new regions of the search space through regeneration [31]. In this manner, the algorithm simultaneously performs exploration and exploitation while maintaining population diversity [20,36,51,52,53]. For initialization, a population of trees (candidate solutions) is randomly generated as

where is the ith solution at iteration t, d is the dimensionality of the decision vector, l and u are the lower and upper bounds of the search space [36,51]. Each solution generates sparks—new candidate solutions around itself [20,52,53];

Here, is the adaptive burning radius and operated between , is the adaptive scaling factor, and is a uniformly distributed random vector. The burning radius decreases over time to shift from exploration to exploration as given below [20,36,52,53];

The worst solutions (burned trees) are replaced with new random solutions:

where is the regeneration ratio. Additionally, the adaptive scaling factor in (29) is updated using the following equation [52,53]:

where is the decay rate of the function. In addition, the renewal probability, which governs random regeneration events, is defined as given below.

Here, the renewal probability in (33) is governed by . For the AFFO algorithm, the defined penalty-based fitness function can be defined using Deb’s Constraint Dominance Principle [20,36,52,53]:

where are the inequality constraints, represents the equality constraints, and is the penalty weight, respectively [54]. Furthermore, the population for the next iteration is selected from the union of current solutions, sparks, and regenerated ashes [36,52,53]:

The operator BestN selects the N best individuals with respect to the penalized fitness function F(x).

In this study, DEA was applied to PI tuning by representing each individual in the population as a vector [Kp, Ki]. Mutation, crossover, and selection operators were applied directly to these parameters to minimize the ITAE performance index of the heat-flow system. The results of the proposed optimization framework can be applicable not only to this study but also to a variety of slow thermal processes, including heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) control, industrial heating equipment, chemical reactors, and renewable energy thermal systems. The optimal parameters of the PI controller were obtained by minimizing a single performance criterion. Specifically, we adopted the ITAE as the objective function, which is widely used in control engineering due to its ability to penalize long-duration errors more severely. The ITAE index is defined as follows [55]:

where e(t) denotes the tracking error and T is the simulation time horizon, respectively. For systems such as the HFS studied here, where slow error decay is undesirable, ITAE provides a more meaningful and application-oriented performance measure. Thus, the optimization problem is formulated as a single-objective problem [55]:

subject to the stability constraints of the closed-loop system and the feasible bounds of the controller parameters. The metaheuristic algorithms used in this study search for the parameter set (Kp, Ki) that minimizes .

3. Experimental Results

In this section, the experimental results of all optimization methods have been presented. The lower and upper bound values of the controller parameters are selected as and , respectively. Also, the controller parameter values obtained from all optimization methods are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The controller parameter values obtained via each optimization method.

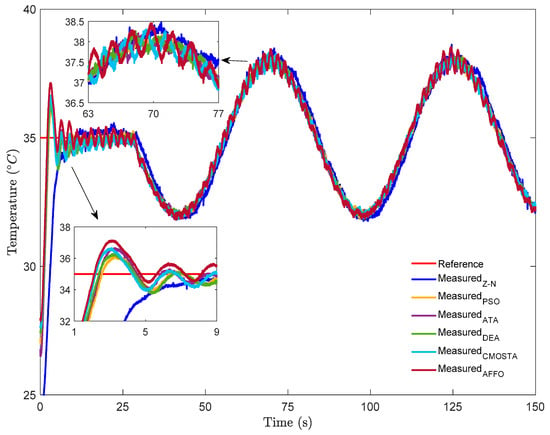

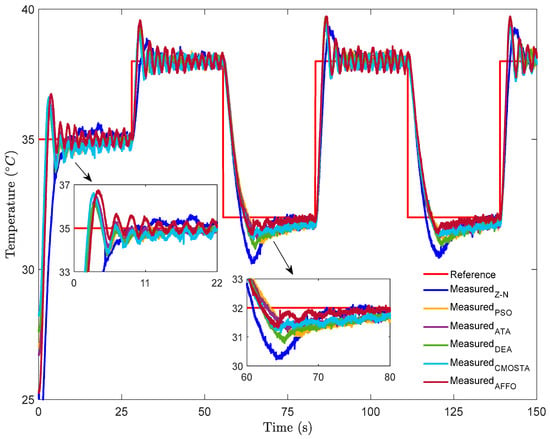

In Figure 2, a step + sinusoidal reference signal is applied to the HFS. For the step part of the reference signal, all optimization methods exhibited nearly the same rise time, with the exception of the Z–N method. As can be seen in the figure, the AFFO method reached the reference signal faster than the other optimization methods. However, although the AFFO method achieved the shortest settling time, it also exhibited a larger overshoot magnitude value compared to the other optimization techniques. Examining the performance of the Z–N method, it is observed that the reference signal was reached at approximately the 11th second, after which the method continued to track the reference with a noticeable overshoot. Furthermore, although all methods except Z–N followed the reference with slight oscillations, the DEA method demonstrated the best temperature tracking performance among them.

Figure 2.

Experimental results for all optimization methods under step + sinusoidal reference signal.

For the sinusoidal part of the reference signal, the Z–N method was observed to have difficulty tracking the reference signal, exhibiting large tracking errors and frequent overshoots. In addition, the AFFO method followed the reference signal with more pronounced oscillations compared to the other optimization methods, with CMOSTA showing the closest performance to it. Furthermore, similarly to the behavior observed in the step part of the reference signal, the DEA method demonstrated superior performance in tracking the smoothly varying sinusoidal reference signal compared to the other methods.

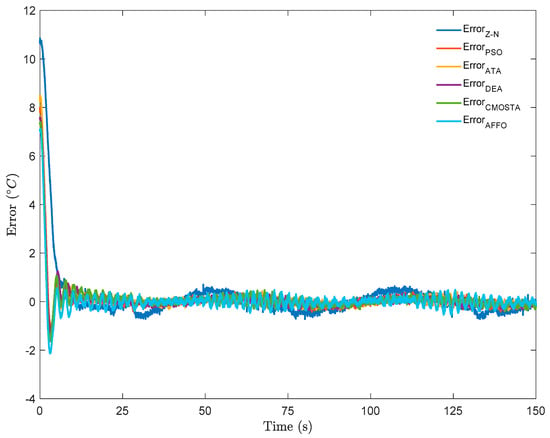

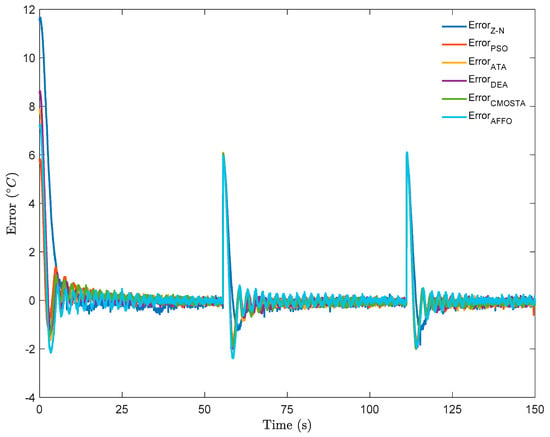

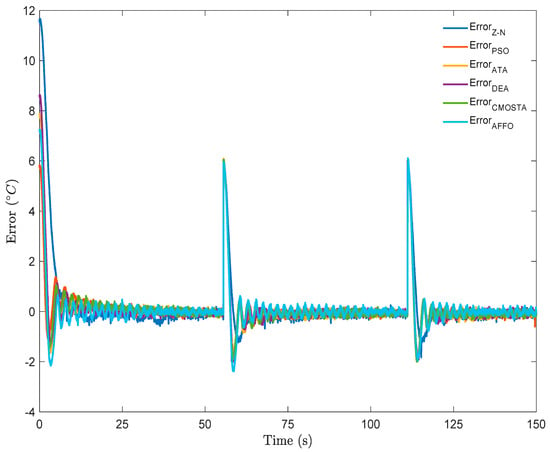

In Figure 3, the error signals for all optimization methods are presented. As can be seen from the figure, the Z–N method exhibited the highest reference tracking error. All methods exhibit a pronounced transient error at the beginning of the experiment, which is expected due to the initial mismatch between the setpoint and the measured temperature and the intrinsic thermal inertia of the heat-flow system. However, clear differences emerge in both the transient attenuation and the steady-state error behavior. The Z–N-tuned controller produced the largest error amplitude and the most persistent deviation from zero, indicating a comparatively less robust tuning for this slow thermal process. This behavior suggests weaker disturbance rejection and a suboptimal balance between response speed and damping, which results in larger excursions during tracking.

Figure 3.

Error signals of all optimization methods under step + sinusoidal reference signal.

For the metaheuristic-based controllers, the error signals converge more rapidly toward a narrow band around zero, implying improved damping and more consistent reference tracking. Although their steady-state error magnitudes are close to each other, the DEA-based tuning exhibits a visibly smaller error envelope over the entire time horizon. In particular, the DEA curve remains closer to zero not only after the initial transient but also during later intervals where small oscillatory components and low-frequency drift appear. This indicates that the DEA-tuned PI parameters provided a better trade-off between tracking accuracy and robustness against measurement noise, airflow disturbances, and unmodeled dynamics.

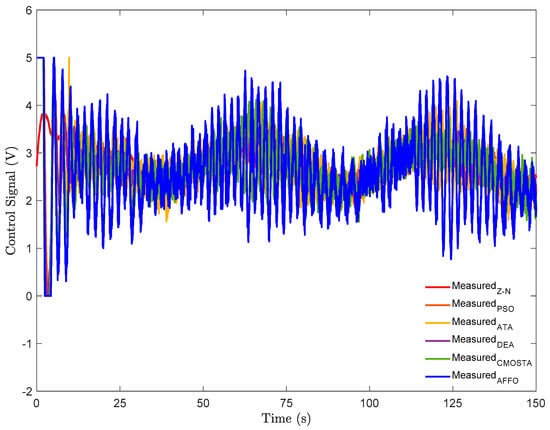

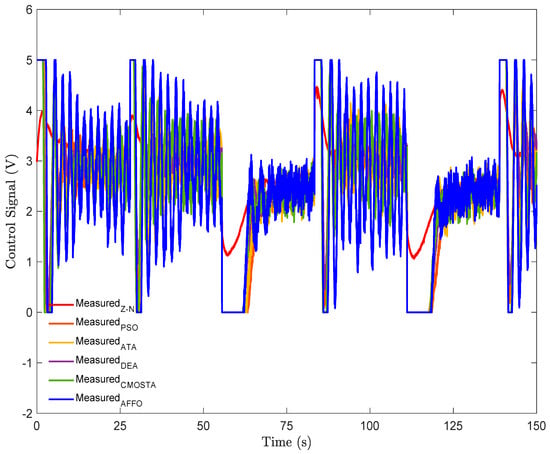

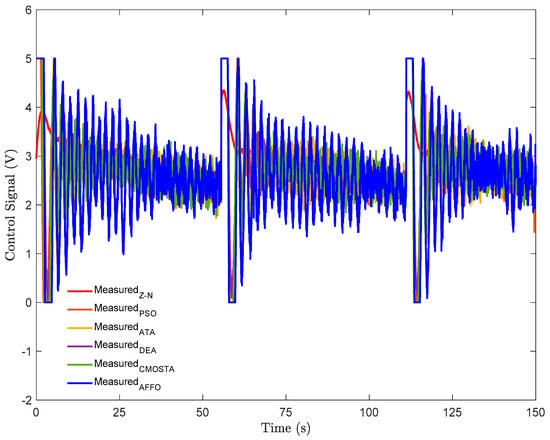

In Figure 4, the control signals of all optimization methods have been depicted. For each method, the amplitude of the control signal applied to the system for temperature tracking was kept within the range of 0–5 V. As illustrated in the figure, the AFFO method produced the highest amplitude and most oscillatory control signal along the reference trajectory compared to the other methods. Although the Z–N method generated the least oscillatory control signal, the control effort produced by the controller parameters obtained with this method was insufficient for effective reference temperature tracking. In contrast, the DEA method, which provided the best temperature tracking performance, produced one of the lowest amplitude control signals, together with CMOSTA.

Figure 4.

Control signals of all optimization methods for step + sinusoidal reference signal.

Moreover, the MAE values obtained from the experimental results to analyze the reference temperature tracking performance of all optimization methods are presented in Table 3. For the step part of the reference signal, the DEA method had the lowest MAE value of approximately 0.6188, which shows that it is the optimization method with the highest tracking accuracy. After that, the DEA was followed by AFFO with 0.6291, PSO with 0.6416, CMOSTA with 0.6602, and ATA with 0.6650, respectively. Furthermore, the highest MAE value, 1.3471, was observed for the Z–N method, indicating that it exhibited the worst reference tracking performance for the step part of the reference signal. When analyzing the MAE values for the sinusoidal part of the reference signal, it is seen that all optimization methods had almost the same MAE value, but the method with the lowest MAE value was the DEA, with approximately 0.0901. Further, it was observed that this method was followed by CMOSTA with 0.1011, PSO with 0.1098, ATA with 0.1107, AFFO with 0.1307 and Z–N with 0.2930, respectively. Additionally, it was observed that the DEA achieved the lowest overall MAE value for the entire reference signal, approximately 0.2055, indicating the best tracking performance, while Z–N recorded the highest MAE value, around 0.4898.

Table 3.

The MAE values of all optimization methods for step + sinusoidal reference signal.

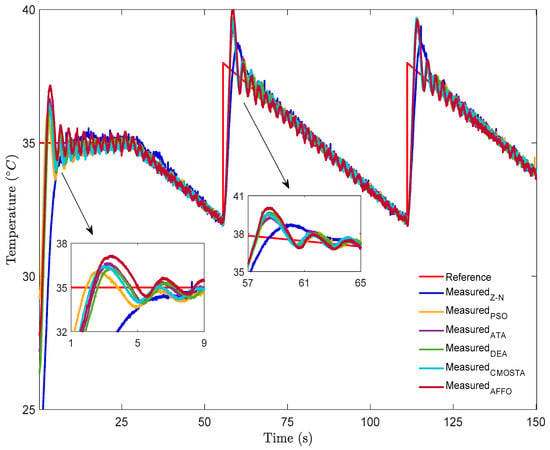

In Figure 5, the experimental results for all optimization methods have been depicted for step + square reference signal. Examining the step part of the reference signal, it is observed that the CMOSTA, DEA, and PSO methods exhibited closely similar rise time performance, whereas the AFFO method displayed the largest overshoot compared to the other techniques. In addition, the AFFO and CMOSTA methods showed more pronounced oscillations during reference tracking relative to the remaining methods. In contrast, the performance of the Z–N method indicated that the reference signal was reached at approximately the 11th second, after which the method continued to track the reference with a noticeable overshoot. In the time-varying portion of the reference signal, a square temperature signal form was applied to evaluate how the controller parameters respond to sudden changes. As illustrated in the figure, the DEA, AFFO, and CMOSTA methods responded more rapidly to the sudden changes in the square reference than the other methods. However, the AFFO method exhibited the highest overshoot, and together with CMOSTA, produced larger oscillations during reference tracking compared to the other approaches. Furthermore, in the decreasing phase of the square reference, the Z–N method showed the highest overshoot, while the DEA method followed the reference temperature with performance comparable to CMOSTA, ATA, and PSO.

Figure 5.

Experimental results for all optimization methods under step + square reference signal.

In Figure 6, the error signals of all optimization methods throughout the step + square reference signal have been depicted. In the step part of the reference signal, the DEA method exhibited a lower reference tracking error compared to the other methods. In contrast, the AFFO method showed some error oscillations with amplitudes ranging from −2 to 1. Similar oscillatory behavior was observed in the CMOSTA method. The PSO and ATA methods exhibited nearly the same error amplitudes. When examining the Z–N method performance, while the other methods maintained the error values around approximately 0, the error magnitude for Z–N varied within the range of −0.5 to 0.5 throughout to the square reference signal. For the time-varying part of the reference signal, it was observed that under sudden changes, the AFFO method produced higher error values (−1 to 1) compared to the other methods, whereas the Z–N method exhibited errors due to overshoot. Moreover, the PSO method showed the next highest error oscillations following AFFO, followed by CMOSTA, ATA, and DEA, with the DEA method achieving the lowest error magnitude overall.

Figure 6.

Error signals of all optimization methods under step + square reference signal.

In Figure 7, the control signals of all optimization methods have been given. In the step part of the reference signal, the AFFO method produced a higher amplitude control signal compared to the other methods. The method with the next highest control signal amplitude was ATA, followed by CMOSTA, PSO, and DEA, in that order. Although the Z–N method generated the least oscillatory control signal, the controller parameters obtained with this method resulted in the poorest temperature tracking performance. For the square reference signal, the control signal amplitudes showed a similar trend: the AFFO method exhibited the highest amplitude and oscillations, followed by ATA, CMOSTA, PSO, and DEA. Notably, although the DEA method produced the lowest amplitude control signal, it achieved the lowest error magnitude, as also illustrated in the error graph in Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Control signals of all optimization methods for step + square reference signal.

Additionally, the MAE values obtained from the experimental results for the step + square temperature signal, used to evaluate the temperature tracking performance of all optimization methods, are presented in Table 4. For the step portion of the reference signal, the DEA method exhibited the lowest MAE of approximately 0.6006, indicating the highest tracking accuracy among the methods. It was followed by ATA (0.6443), PSO (0.6468), CMOSTA (0.6537), AFFO (0.7966), and Z–N (1.3655). For the square part of the reference signal, all methods showed relatively similar MAE values, with DEA again achieving the lowest value of approximately 0.7014. This was followed by CMOSTA (0.7107), ATA (0.7150), AFFO (0.7357), PSO (0.7483), and Z–N (0.7651). Considering the overall reference tracking performance across the entire signal, the DEA method again achieved the best result with a MAE of 0.7005, followed by ATA (0.7018), CMOSTA (0.7100), AFFO (0.7192), PSO (0.7294), and Z–N (0.8772). These results indicate that the controller parameters obtained using DEA provided the most accurate reference tracking performance.

Table 4.

The MAE values of all optimization methods for step + square reference signal.

In Figure 8, the experimental results for all optimization methods have been depicted for the step + sawtooth reference signal. For the step part of the reference signal, the PSO method reached the reference signal most quickly, followed by CMOSTA, AFFO, ATA, and DEA, respectively. Additionally, the AFFO method exhibited the highest overshoot, while the PSO and DEA (excluding Z–N) displayed the lowest overshoot, and the remaining methods showed closely similar overshoot magnitudes. All methods tracked the reference temperature signal with slight oscillations throughout the step part, with the largest oscillations observed in AFFO. In contrast, the Z–N method reached the reference at approximately the 12th second and continued tracking with overshoot thereafter. For the sawtooth part, which includes both abrupt and smooth changes, the AFFO method again showed the highest overshoot, followed by CMOSTA, DEA, PSO, and ATA. All methods attempted to track the slowly varying portion of the sawtooth reference with slight oscillations, and nearly all optimization methods exhibited similar reference tracking performance and amplitude profiles. Additionally, the Z–N method responded very slowly to the sudden change and continued to track the reference with overshoot.

Figure 8.

Experimental results for all optimization methods under step + sawtooth reference signal.

In Figure 9, the error signals of all optimization methods under the step + sawtooth reference signal have been given. For the step part, the Z–N method exhibited the highest initial error, followed by DEA, ATA, CMOSTA, AFFO, and PSO, respectively. Additionally, the AFFO method, which exhibited the largest overshoot, showed an error magnitude approaching nearly 2. The Z–N method, due to its delayed response and subsequent overshoot, exhibited error values fluctuating between −0.5 and 0.5, whereas the error values of the other optimization methods quickly converged to nearly zero. For the sudden-change part of the sawtooth reference signal, the highest error was observed in the AFFO method, followed by DEA, PSO, ATA, and CMOSTA. The error amplitudes of all methods varied approximately between −0.5 and 0.5 and subsequently converged to nearly zero. In contrast, the Z–N method failed to converge to zero throughout the sawtooth signal, with the error magnitude continuously fluctuating due to overshoot. Overall, the DEA method demonstrated relatively superior reference tracking performance compared to the other methods.

Figure 9.

Error signals of all optimization methods under step + sawtooth reference signal.

Figure 10 presents the control signals obtained from all optimization methods. For the step part of the reference signal, the AFFO and CMOSTA methods produced the highest control signal amplitudes, followed by PSO, ATA, and DEA, in that order. Although the control signal generated by the AFFO method had a higher amplitude, its reference tracking performance was found to be lower compared to the other methods. Additionally, the control signal of the Z–N method exhibited minimal oscillation and varied approximately between 0 and 4 V. For the sawtooth part of the reference signal, the AFFO method again produced the highest amplitude control signal, followed by PSO, ATA, CMOSTA, and DEA. Despite ATA, CMOSTA, and AFFO generating relatively higher control signal amplitudes, the DEA method achieved comparatively more effective reference tracking performance. It was also observed that the control signals reached their maximum value of 5 V at points corresponding to sudden changes in the reference signal, while their amplitudes were significantly lower in regions characterized by smoother changes.

Figure 10.

Control signals of all optimization methods under step + sawtooth reference signal.

Table 5 presents the MAE values obtained from the experimental results for the step + sawtooth temperature signal to analyze the temperature monitoring performance of all optimization methods. Firstly, it was observed that the highest MAE value for the step part of the reference signal was obtained with the Z–N method, with approximately 1.3413. On the other hand, it was observed that the best temperature tracking in the step part of the reference signal was obtained with the controller parameters combined with the DEA method, having the lowest MAE value of approximately 0.6434. Secondly, it was observed that the lowest MAE value for the part of the reference signal containing time-dependent changes was obtained with DEA, of approximately 0.2603, while the highest value was obtained with Z–N, again at 0.3334. Thus, it was observed that the controller parameters obtained with DEA followed the sawtooth reference signal with less error than the other methods. Finally, it was observed that the best reference tracking performance and minimum MAE value, of 0.3310, throughout the entire reference signal were achieved using the controller parameters obtained with the DEA method, followed by CMOSTA (0.3442), PSO (0.3354), ATA (0.3374), AFFO (0.3533), and Z–N (0.5215), respectively.

Table 5.

The MAE values for all optimization methods for step + sawtooth reference signal.

4. Discussion

In this study, the parameters (Kp and Ki) of the PI controller, used in the temperature control of a time-delayed HFS system, were obtained by using Z–N, ATA, AFFO, PSO, CMOSTA, and DEA optimization methods and tested in real time for three different step + time-varying reference signals. The results were analyzed, and both transient response and performance analyses were performed by calculating MAE values. As a result, the following findings were obtained.

- The first experiment, step + sinusoidal temperature reference signal, was implemented to analyze the reference tracking performances of the controller parameters obtained via the mentioned optimization methods, during a smoothly changing signal. Table 6 presents the improvement rates of the PSO, ATA, AFFO, CMOSTA, and DEA methods with respect to the Z–N method. Examination of the table shows that, for the step part of the reference signal, all proposed optimization methods achieved at least a 50% improvement rate in reference tracking performance over the Z–N method. Furthermore, the DEA method demonstrated the highest improvement rate, achieving approximately 54.06% with the obtained controller parameters.

Table 6. Improvement rates of all optimization methods for step + sinusoidal reference signal.

Table 6. Improvement rates of all optimization methods for step + sinusoidal reference signal.

- In the second experiment, a step + square reference signal was applied to evaluate the controllers’ responses to sudden changes, in contrast to the previous reference signal. Table 7 presents the improvement rates achieved by the optimization methods proposed in this study compared to the Z–N method. For the step portion of the reference signal, the DEA method exhibited the highest improvement rate at approximately 56.01%, followed by ATA (52.81%), PSO (52.63%), CMOSTA (52.12%), and AFFO (41.66%), respectively. Throughout the square reference signal, the controller parameters obtained by using the DEA method achieved the highest improvement rate in reference tracking compared to Z–N, with an improvement rate of approximately 9.5%, followed by CMOSTA with 8.3%, ATA with 7.75%, AFFO with 5.08%, and PSO with 3.45%. As a result, as shown in the table, the controller parameters obtained by using the DEA method achieved the highest overall reference tracking improvement of 20.14% compared to the Z–N method across the entire reference signal.

Table 7. Improvement rates of all optimization methods for step + square reference signal.

Table 7. Improvement rates of all optimization methods for step + square reference signal.

- The improvement rates achieved in the final experiment, using the step + sawtooth reference signal, are presented in Table 8. As can be seen from the table, in the step part, the DEA method achieved nearly 52% better reference tracking than Z–N, followed by PSO with 51.35%, ATA with 50.84%, CMOSTA with 50.76%, and AFFO with 49.92%. Additionally, for the sawtooth part of the reference signal, which includes both sudden and smooth changes, the DEA method outperformed Z–N, achieving an improvement of approximately 21.92%, followed by CMOSTA with 21.50%, ATA with 20.96%, PSO with 20.06%, and AFFO with 15.92%. Finally, across the entire reference signal, the DEA method not only achieved a 36.52% improvement in reference tracking compared to Z–N, but also demonstrated the highest overall improvement among all the optimization methods.

Table 8. Improvement rates of all optimization methods for step + sawtooth reference signal.

Table 8. Improvement rates of all optimization methods for step + sawtooth reference signal.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the parameters (Kp and Ki) of the linear controller used in the temperature control of a time-delayed HFS system were obtained using the AFFO, PSO, CMOSTA, DEA, and ATA optimization methods and tested in real time for three different step + time-varying reference signals. Performance was assessed using formal response analysis and the MAE metric. Moreover, the Z–N method was selected as the benchmark because it is widely used for slow thermal processes and provides a stable, well-known reference for comparison. The quantitative comparisons have demonstrated that the DEA-based PI controller provided the best overall reference tracking performance among all methods.

For the first experiment under the step + sinusoidal reference signal, the DEA method provided 1.27%, 13.12%, 16.57%, and 24.48% better tracking accuracy compared with the PSO, ATA, CMOSTA, and AFFO methods, respectively.

As a second experiment using a step + square reference signal, DEA achieved improvements of 16.38% over PSO, 0.74% over ATA, 5.36% over CMOSTA, and 10.57% over AFFO.

For the last experiment, realized via the step + sawtooth reference signal, the DEA-based PI controller outperformed PSO by 2.30%, ATA by 3.34%, CMOSTA by 1.67%, and AFFO by 11.67%.

These results clearly show that the DEA consistently yields superior reference tracking performance across all test scenarios. The optimized PI structure is applicable to numerous slow thermal processes, including HVAC systems, industrial furnaces and dryers, chemical reactor temperature regulation, and heat-exchange systems.

In future studies, the number of parameters to be optimized will be increased by employing a fractional-order PI controller, which offers greater flexibility compared to the classical integer-order PI controller. In addition, we aim to enhance the efficiency of the PI controller, which is widely used in industry, by employing other up-to-date optimization methods available in the literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.K. and K.C.; methodology, F.K.; software, F.K.; validation, F.K. and K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.K.; writing—review and editing, F.K. and K.C.; supervision, K.C.; project administration, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available, as they are part of an ongoing master’s thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PI | Proportional-Integral |

| DEA | Differential Evolution Algorithm |

| HFS | Heat-Flow System |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning |

| ATA | Artificial Tree Algorithm |

| AFFO | Adaptive Fire Forest Algorithm |

| AT | Artificial Tree |

| Z–N | Ziegler–Nichols |

| CMOSTA | Constrained Multi-Objective State Transition Algorithm |

| ITAE | Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error |

| IAE | Integral of Absolute Error |

References

- Bejan, A.; ASME, F.; Jones, J.A. From Heat Transfer Principles to Shape and Structure in Nature: Constructal Theory Available to Purchase. J. Heat Transf. 2000, 122, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, M.; Ksiażek, K.; Marciniec, J.; Połap, D. Heat production optimization using bio-inspired algorithms. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 76, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Can, K.; Başçi, A. PI + Feed Forward Controller Tuning Based on Genetic Algorithm for Liquid Level Control of Coupled-Tank System. J. Inst. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyoussef, F.; Kaya, İ.; Akrad, A. Robust PI-PD Controller Design: Industrial Simulation Case Studies and a Real-Time Application. Electronics 2024, 13, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huba, M.; Chamraz, S.; Bistak, P.; Vrancic, D. Making the PI and PID Controller Tuning Inspired by Ziegler and Nichols Precise and Reliable. Sensors 2021, 21, 6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf Talesh, S.H.; Nariman-zadeh, N.; Jamali, A. Multi-objective parametric design of PI/PID controllers via multi-level game-theoretic optimization for systems with time delay. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2022, 44, 2532–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.S. Tuning a PI/PID Controller with Direct Synthesis to Obtain a Non-Oscillatory Response of Time-Delayed Systems. Appl. Sci 2024, 14, 5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izci, D.; Jabari, M.; Çelik, E.; Ekinci, S.; Bajaj, M.; Rubanenko, O.; Prokop, L. Designing a cascaded exponential PID controller via starfish optimizer for DC motor and liquid level systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, S.; Izci, D.; Gider, V.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L. Quadratic interpolation optimization-based 2DoF-PID controller design for highly nonlinear continuous stirred-tank heater process. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk-Allah, R.M.; Ekinci, S.; Jabari, M.; Izci, D.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Rubanenko, O. Enhanced PID controller tuning for nonlinear continuous stirred-tank heaters using a modified Newton-Raphson optimizer with random opposition and Lévy-flight learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighizadeh, D.; Masehian, E. Particle Swarm Optimization Methods, Taxonomy and Applications. Int. J. Comput. Theory Eng. 2009, 1, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Patel, V.K. Thermodynamic optimization of cross flow plate-fin heat exchanger using a particle swarm optimization algorithm. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2010, 49, 1712–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, S.; Gadala, M.S. Effectiveness and Efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization Technique in Inverse Heat Conduction Analysis. Numer. Heat Transf. Part B Fundam. 2009, 56, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Guo, R.; Pan, X.; Li, T. Study on the sliding mode fault tolerant predictive control based on multi agent particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2017, 15, 2034–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.B.; Dada, E.G.; Abidemi, A.; Oyewola, D.O.; Khammas, B.M. Metaheuristic algorithms for PID controller parameters tuning: Review, approaches and open problems. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Deng, Z.; Luo, J. Damage identification of steel bridge based on data augmentation and adaptive optimization neural network. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 24, 1674–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Song, K.; He, Z.C.; Li, E.; Cheng, A.G.; Chen, T. The artificial tree (AT) algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2017, 65, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahak, C.; Nanda, S. Duality for multiobjective variational problems with invexity. Optimization 1996, 36, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, H.; Zhou, X.; Yang, C.; Xie, Y. Optimization of both operating costs and energy efficiency in the alumina evaporation process by a multi-objective state transition algorithm. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 94, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, J.S.; Vijayasekaran, G.; Gugan, I.; Priyadharshi, P.N. Adaptive forest fire optimization algorithm for enhanced energy efficiency and scalability in wire-less sensor networks. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, R.D.L.; Aguayo, M.M.; Contreras-Bolton, C. An optimization-based approach for an integrated forest fire monitoring system with multiple technologies and surveillance drones. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 313, 435–451. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377221723006124 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential Evolution—A Simple and Efficient Heuristic for Global Optimization over Continuous Spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R. On the usage of differential evolution for function optimization. In Proceedings of the Conference of the North American Fuzzy Information Processing Society—NAFIPS, Berkley, CA, USA, 19–22 August 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Mohamed, A.W.; Xiao, T. Adaptive Differential Evolution Based on Successful Experience Information. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164611–164636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Gao, S.; Liao, N.; Liu, H. A nonlinear goal-programming-based DE and ANN approach to grade optimization in iron mining. Neural Comput. Appl. 2016, 27, 2065–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Yan, R.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, H. Application Research of Differential Evolution Algorithm in Resistance Coefficient Identification of Heating Pipeline. Therm. Eng. 2024, 71, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Shang, S.; Cai, X.; Zhao, H.; Song, Y.; Xu, J. An improved differential evolution algorithm and its application in optimization problem. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 5277–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanser Heat Flow Experimental User Manual, Quanser Inc., Markham, ON, Canada, 2005. Available online: https://www.quanser.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Heat-Flow-Experiment-Datasheet.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Orman, K. Design of a Memristor-Based 2-DOF PI Controller and Testing of Its Temperature Profile Tracking in a Heat Flow System. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 98384–98390. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=9889718 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Wang, D.; Yue, C.; Wei, S.; Lv, J. Performance Analysis of Four Decomposition-Ensemble Models for One-Day-Ahead Agricultural Commodity Futures Price Forecasting. Algorithms 2017, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencheikh, G. Metaheuristics and Machine Learning Convergence: A Comprehensive Survey and Future Prospects. Metaheuristic Mach. Learn. Optim. Strateg. Complex Syst. 2024, 276–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, R.J.; Yu, N.Y.; Hu, J.-Y. Application of Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm in the Heating System Planning Problem. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 718345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitak, P.; Glotic, A.; Ticar, I. Heat Transfer Coefficients Determination of Numerical Model by Using Particle Swarm Optimization. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlker, G.; Özkan, İ. SADASNet: A Selective and Adaptive Deep Architecture Search Network with Hyperparameter Optimization for Robust Skin Cancer Classification. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Pan, L.; Fang, X. Bio-Inspired Computing—Theories and Applications. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference, BIC-TA 2015, Hefei, China, 25–28 September, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y. Artificial Intelligence Algorithms and Applications. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium, ISICA 2019, Guangzhou, China, 16–17 November, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Lu, Z.; Wen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L. Energy-Efficient Power Allocation with QoS Guarantee in OFDMA Wireless Networks. In Proceedings of the International Symposium, WPMC 2014, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 7–10 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abada, L.; Bennaceur, M.; Boudjenana, A.A.; Aouat, S. Using PSO metaheuristic to solve photometric 3D reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium, ISPA 2022, Mostaganem, Algeria, 8–9 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Khadraoui, S.; Nounou, H. A Nonparametric Approach to Design Fixed-order Controllers for Systems with Constrained Input. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2018, 16, 2870–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringali, A.; Cocuzza, S. Globally Optimal Inverse Kinematics Method for a Redundant Robot Manipulator with Linear and Nonlinear Constraints. Robotics 2020, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Jin, R. Binary Coding and Optimization Method. In Antenna Optimization and Design Based on Binary Coding; Modern Antenna; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ledezma, G.A.; Bejan, A.; Errera, M.R. Contractual tree networks for heat transfer. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 82, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornuejols, G.; Tütüncü, R. Optimization Methods in Finance; Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2006; p. 349. [Google Scholar]

- Cermak, J.; Deml, M.; Penka, M.A. New Method of Sap Flow Rate Determination in Trees. Biol. Plant. (Praha) 2008, 15, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, H.; Xiang, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X. A Comparative Study on Evolutionary Algorithms and Mathematical Programming Methods for Continuous Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9870359 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, G. Improved Differential Evolutions Using a Dynamic Differential Factor and Population Diversity. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computational Intelligence, Shanghai, China, 7–8 November 2009; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5376243 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Sayah, S.; Zehar, K. Modified differential evolution algorithm for optimal power flow with non-smooth cost functions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 3036–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.V.; Jehan, M.M.L. Differential evolution for multi-objective optimization. In Proceedings of the 2003 Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Canberra, ACT, Australia, 8–12 December 2003; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1299429 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Atofarati, E.O.; Enweremadu, C.C. Industry 4.0 enabled calorimetry and heat transfer for renewable energy systems. iScience 2025, 28, 112994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Xiang, Q.L. Exploring new learning strategies in Differential Evolution algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2008 Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Hong Kong, China, 1–6 June 2008; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4630800 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Q.; Li, Y. Demand Response Strategies for Electric Vehicle Charging and Discharging Behaviour Based on Road–Electric Grid Interaction and User Psychology. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.ejge.com/2015/Ppr2015.0318ma.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Autio, M.; Laitinen, M.; Pramila, A. Systematic creation of composite structures with prescribed thermomechanical properties. Compos. Eng. 1993, 3, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.M.; Al-Dhaifallah, M.; Rezk, H.; Habib, H.U.R.; Hamad, S.A. Optimizing battery discharge management of PMSM vehicles using adaptive nonlinear predictive control and a Generalized Integrator. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, K.J.; Hägglund, T. PID Controllers: Theory, Design, and Tuning, 2nd ed.; Instrument Society of America (ISA): Durham, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.