Acute Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation Improves Repeated Sprint Ability in Recreational Female Football Players: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

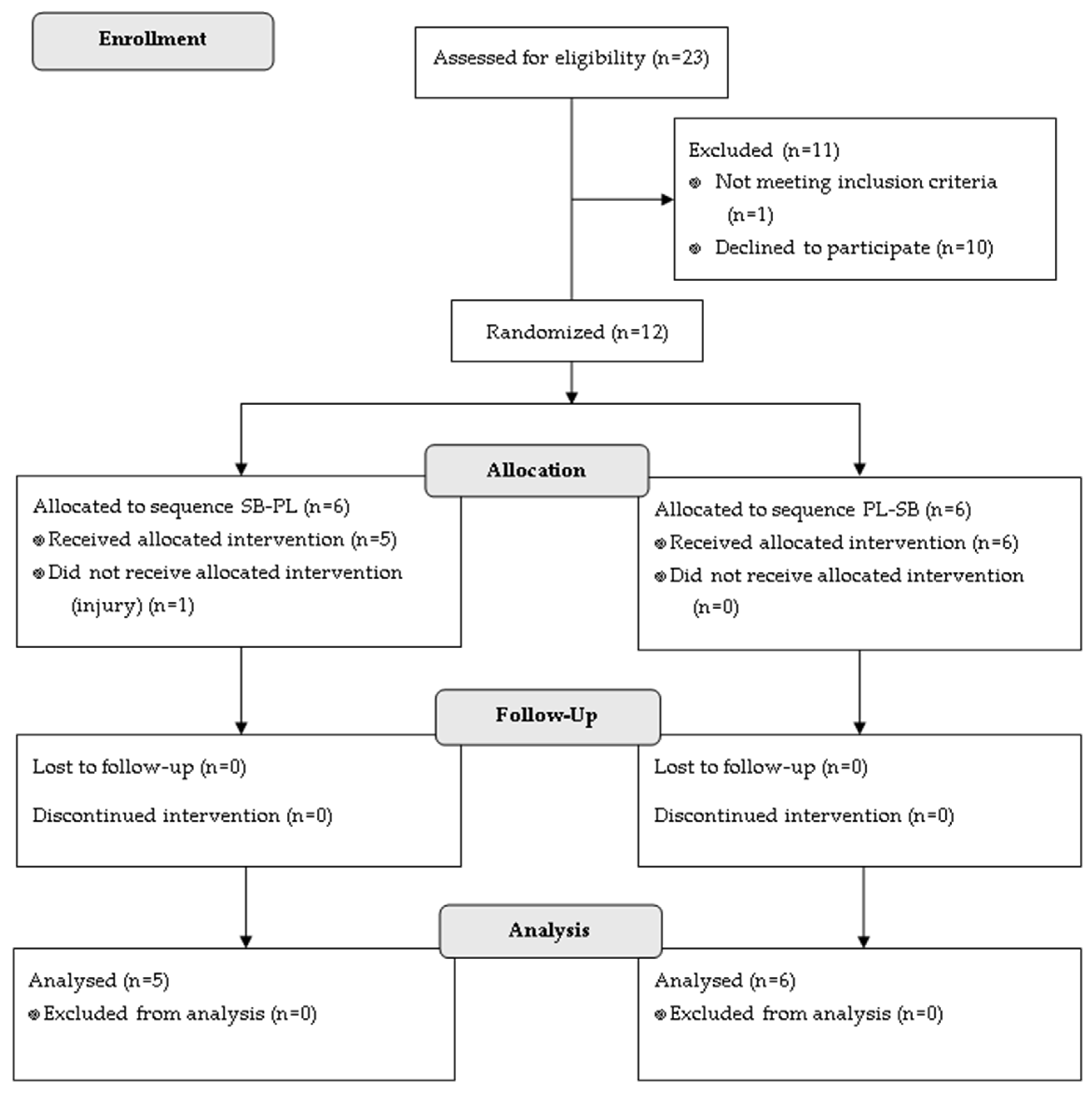

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Anthropometry and Body Composition

2.4.2. Gastrointestinal Effects of the Supplement

2.4.3. Sprint Performance

2.4.4. Blood Lactate Accumulation

2.4.5. Pulmonary Gas Exchange and Heart Rate

2.4.6. Muscle Oxygenation

2.4.7. Jump Performance

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characterization

3.2. Gastrointestinal Effects of the Supplement

3.3. Sprint Performance

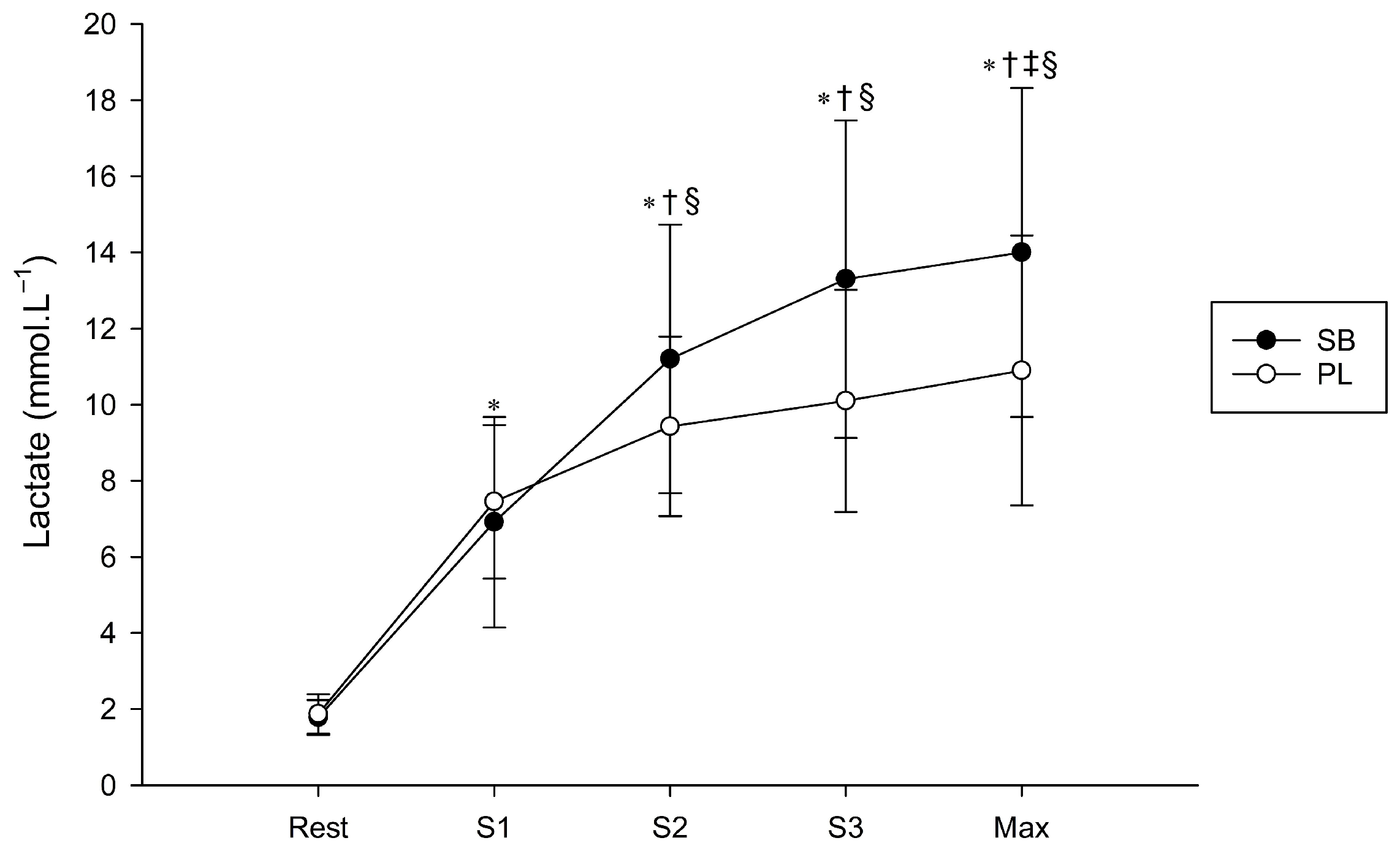

3.4. Blood Lactate Accumulation

3.5. Pulmonary Gas Exchange and Heart Rate

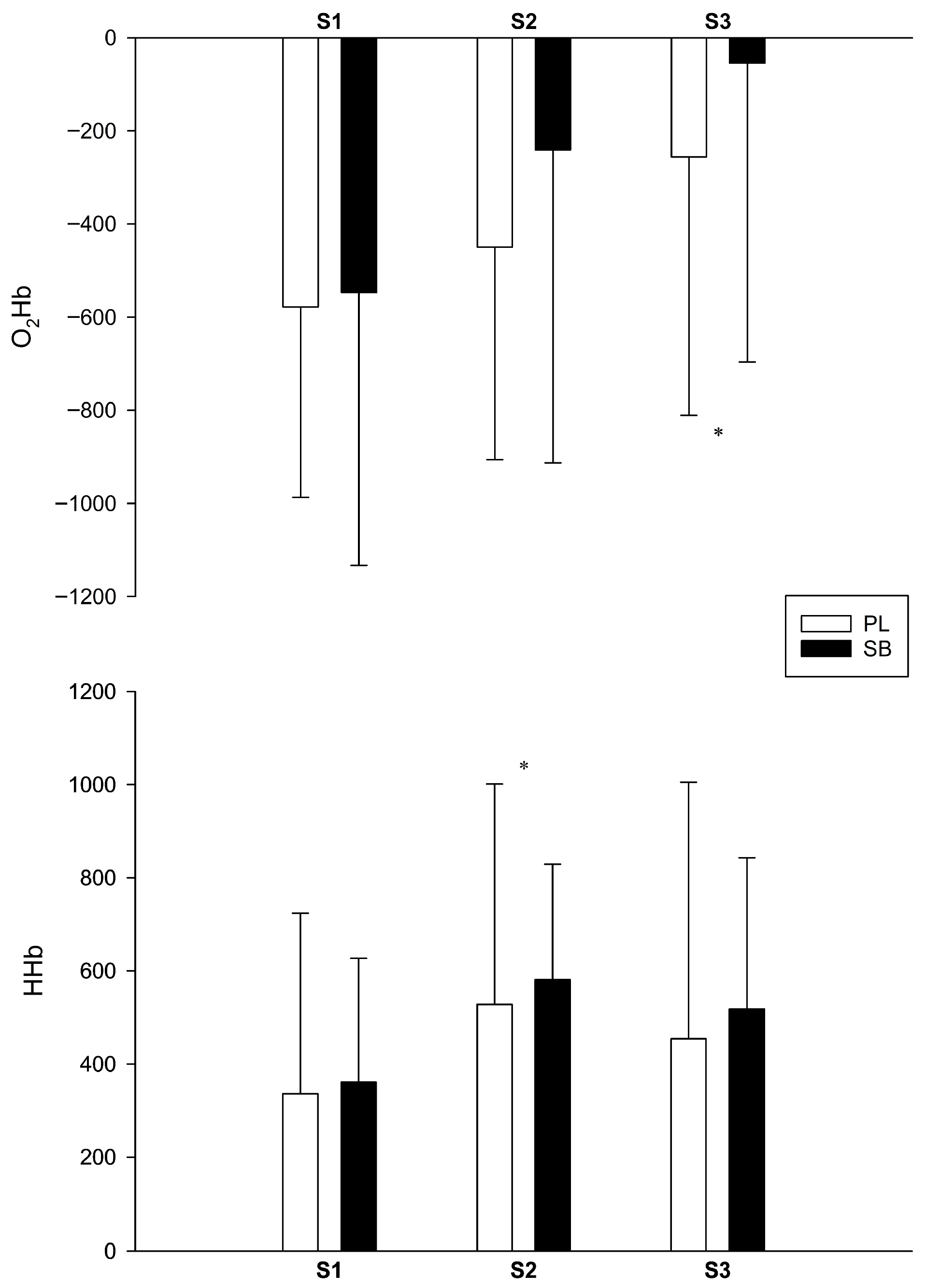

3.6. Muscle Oxygenation

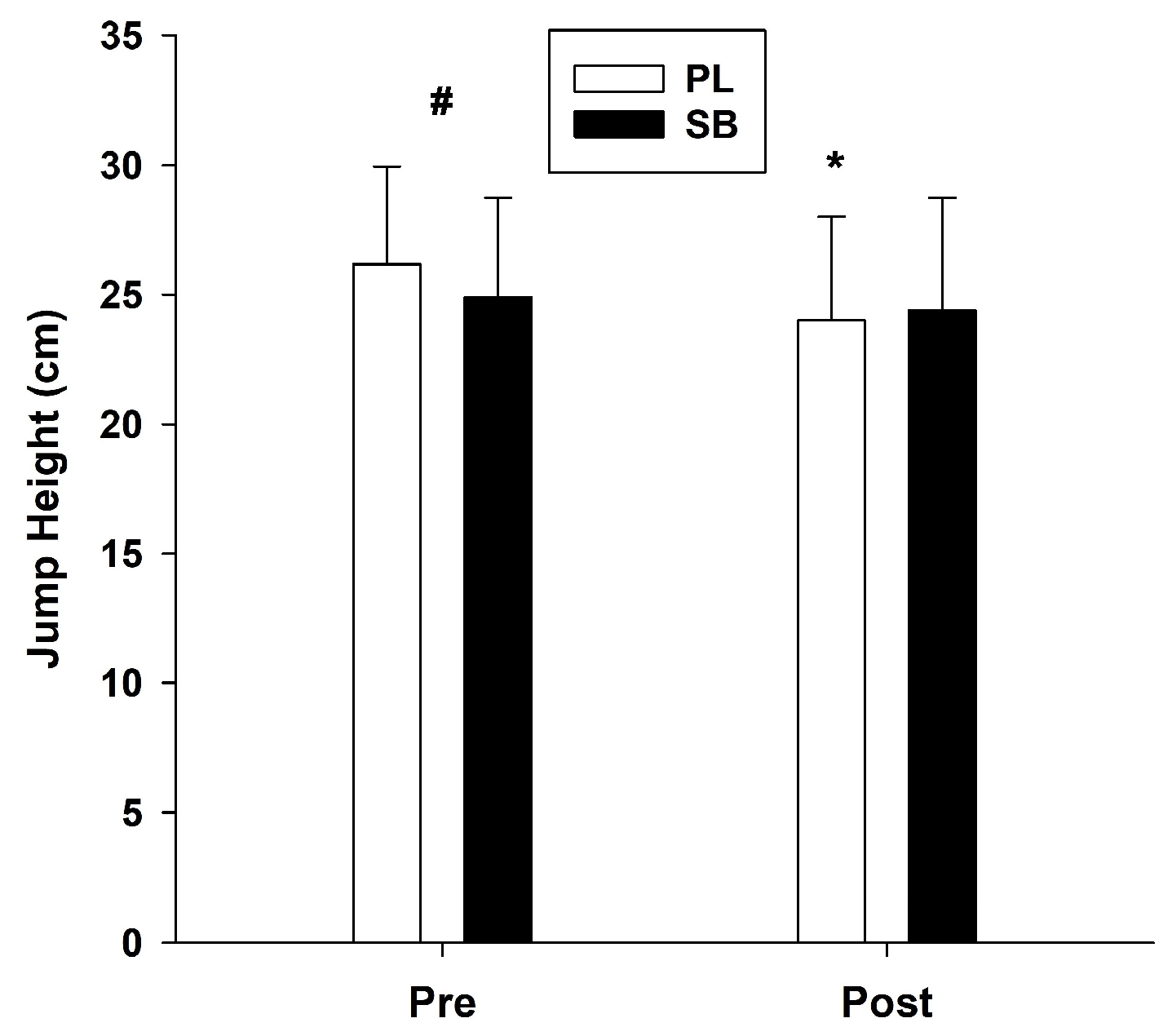

3.7. Jump Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | body mass index |

| CMJ | countermovement jump |

| FFM | fat-free mass |

| FM | fat mass |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| H+ | hydrogen ion |

| HHb | deoxygenated hemoglobin |

| HR | heart rate |

| JH | jump height |

| [La−] | blood lactate accumulation |

| MPO | mean power output |

| NIRS | near-infrared spectroscopy |

| O2Hb | oxygenated hemoglobin |

| PL | placebo |

| PPO | peak power output |

| RSA | repeated sprint ability |

| SB | sodium bicarbonate |

| SDec | sprint decrement |

| TW | total work |

| VCO2 | carbon dioxide output |

| VE | ventilation |

| VO2 | oxygen uptake |

References

- de Sousa, M.V.; Lundsgaard, A.M.; Christensen, P.M.; Christensen, L.; Randers, M.B.; Mohr, M.; Nybo, L.; Kiens, B.; Fritzen, A.M. Nutritional optimization for female elite football players-topical review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32 (Suppl. S1), 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Liu, T.M.; Stage, A.A.; Lazar, A.; Giuliano, D.V.; Hurley, J.M.; Torne, I.A.; Beiley, M.D.; Birmingham-Babauta, S.A.; Stokes, J.J.; et al. Assessing Repeated-Sprint Ability in Division I Collegiate Women Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 2015–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, L.; Clemente, F.M.; Barrera, J.I.; Sarmento, H.; González-Fernández, F.T.; Rico-González, M.; Carral, J. Exploring the Determinants of Repeated-Sprint Ability in Adult Women Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.L.; Stellingwerff, T.; Artioli, G.G.; Saunders, B.; Cooper, S.; Sale, C. Dose-Response of Sodium Bicarbonate Ingestion Highlights Individuality in Time Course of Blood Analyte Responses. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2016, 26, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle, S.; De Smet, S.; Geuns, W.; Rompaye, B.V.; Hespel, P.; Koppo, K. Effect of Stacked Sodium Bicarbonate Loading on Repeated All-out Exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 2019, 40, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J.; Rodriguez, R.F.; Garofolini, A.; Saunders, B.; Bishop, D.J.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Pedisic, Z. Effects of Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation on Muscular Strength and Endurance: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1361–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J.; Pedisic, Z.; Saunders, B.; Artioli, G.G.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; McKenna, M.J.; Bishop, D.J.; Kreider, R.B.; Stout, J.R.; Kalman, D.S.; et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: Sodium bicarbonate and exercise performance. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.L.; Owen, A.L.; Rouissi, M.; Chamari, K. Effects of Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation on Repeated-sprint Ability in Professional vs. Amateur Soccer Players. J. Complement. Med. Altern. Healthc. 2019, 10, 555780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, H.; Karczemna, A.; Włodarek, D. Nutrition for Female Soccer Players-Recommendations. Medicina 2020, 56, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkalec-Michalski, K.; Nowaczyk, P.M.; Saunders, B.; Carr, A.; Kamińska, J.; Steffl, M.; Podgórski, T. Sex-dependent responses to acute sodium bicarbonate different dose treatment: A randomized double-blind crossover study. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2025, 28, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Oliveira, L.F.; Dolan, E.; Durkalec-Michalski, K.; McNaughton, L.; Artioli, G.G.; Swinton, P.A. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation and the female athlete: A brief commentary with small scale systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullinger, S.A.; Cocking, S.; Robertson, C.M.; Tod, D.; Doran, D.A.; Burniston, J.G.; Varamenti, E.; Edwards, B.J. Time-of-day variation on performance measures in repeated-sprint tests: A systematic review. Chronobiol. Int. 2019, 37, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, L.R.; Ford, S.; Newbold, C. Effect of Sodium Bicarbonate Ingestion on High Intensity Exercise in Moderately Trained Women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1997, 11, 98–102. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/pages/default.aspx (accessed on 3 January 2022). [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.; Girard, O.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. Repeated-sprint ability—Part II: Recommendations for training. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, N.; Mizuno, S.; Ishimoto, S.; Sakamoto, E.; Maruta, M.; Goto, K. Effect of training in hypoxia on repeated sprint performance in female athletes. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.F.; Matias, C.N.; Campa, F.; Morgado, J.P.; Franco, P.; Quaresma, P.; Almeida, N.; Curto, D.; Toselli, S.; Monteiro, C.P. Bioimpedance Vector Patterns Changes in Response to Swimming Training: An Ecological Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, C.N.; Campa, F.; Santos, D.A.; Lukaski, H.; Sardinha, L.B.; Silva, A.M. Fat-free Mass Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis Predictive Equation for Athletes using a 4-Compartment Model. Int. J. Sports Med. 2021, 42, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; Robinson, A.L.; Sparks, S.A.; Bridge, C.A.; Bentley, D.J.; McNaughton, L.R. The Effects of Novel Ingestion of Sodium Bicarbonate on Repeated Sprint Ability. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, O.; Mendez-Villanueva, A.; Bishop, D. Repeated-sprint ability—Part I: Factors contributing to fatigue. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrigna, L.; Karsten, B.; Marcolin, G.; Paoli, A.; D’Antona, G.; Palma, A.; Bianco, A. A Review of Countermovement and Squat Jump Testing Methods in the Context of Public Health Examination in Adolescence: Reliability and Feasibility of Current Testing Procedures. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.; Edge, J.; Davis, C.; Goodman, C. Induced metabolic alkalosis affects muscle metabolism and repeated-sprint ability. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, D.; Claudius, B. Effects of induced metabolic alkalosis on prolonged intermittent-sprint performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macutkiewicz, D.; Sunderland, C. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation does not improve elite women’s team sport running or field hockey skill performance. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkalec-Michalski, K.; Zawieja, E.E.; Zawieja, B.E.; Michałowska, P.; Podgórski, T. The gender dependent influence of sodium bicarbonate supplementation on anaerobic power and specific performance in female and male wrestlers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, J.L.; Xu, H.; Mon-López, D.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Jiménez, S.L. Effect of sodium bicarbonate contribution on energy metabolism during exercise: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollidge-Horvat, M.G.; Parolin, M.L.; Wong, D.; Jones, N.L.; Heigenhauser, G.J. Effect of induced metabolic alkalosis on human skeletal muscle metabolism during exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 278, E316–E329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granier, P.L.; Dubouchaud, H.; Mercier, B.M.; Mercier, J.G.; Ahmaidi, S.; Préfaut, C.G. Effect of NaHCO3 on lactate kinetics in forearm muscles during leg exercise in man. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, A.B.; Holgado, D.; Luque-Casado, A.; Rojo-Tirado, M.A.; Sanabria, D.; González, C.; Mateo-March, M.; Sánchez-Muñoz, C.; Calderón, F.J.; Zabala, M. Effect of induced alkalosis on performance during a field-simulated BMX cycling competition. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, R.; de Morais Junior, A.C.; Schincaglia, R.M.; Saunders, B.; Pimentel, G.D.; Mota, J.F. Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation Does Not Improve Running Anaerobic Sprint Test Performance in Semiprofessional Adolescent Soccer Players. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2020, 30, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delextrat, A.; Mackessy, S.; Arceo-Rendon, L.; Scanlan, A.; Ramsbottom, R.; Calleja-Gonzalez, J. Effects of Three-Day Serial Sodium Bicarbonate Loading on Performance and Physiological Parameters During a Simulated Basketball Test in Female University Players. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala, M.; Requena, B.; Sánchez-Muñoz, C.; González-Badillo, J.J.; García, I.; Oöpik, V.; Pääsuke, M. Effects of sodium bicarbonate ingestion on performance and perceptual responses in a laboratory-simulated BMX cycling qualification series. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.; Maughan, R.J.; Gleeson, M.; Bilsborough, J.; Jeukendrup, A.; Morton, J.P.; Phillips, S.M.; Armstrong, L.; Burke, L.M.; Close, G.L.; et al. UEFA expert group statement on nutrition in elite football. Current evidence to inform practical recommendations and guide future research. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, N.P.; Leach, N.K.; Sparks, S.A.; Gough, L.A.; Craig, M.M.; Deb, S.K.; McNaughton, L.R. A Novel Ingestion Strategy for Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation in a Delayed-Release Form: A Randomised Crossover Study in Trained Males. Sports Med.-Open 2019, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20 ± 2 |

| Body mass (kg) | 56 ± 6 |

| Height (m) | 1.633 ± 0.057 |

| BMI (kg/m−2) | 21.0 ± 2.10 |

| FFM (kg) | 43.8 ± 4.24 |

| FM (kg) | 12.2 ± 2.03 |

| FM (%) | 21.7 ± 2.42 |

| Variable | PL | SB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| MPO (W) | 296 ± 35.0 | 285 ± 31.7 * | 288 ± 28.0 | 287 ± 29.6 | 291 ± 29.2 | 291 ± 30.6 |

| PPO (W) | 354 ± 44.8 | 356 ± 47.5 | 355 ± 40.5 † | 343 ± 42.0 | 360 ± 49.9 | 358 ± 45.7 † |

| SDec (%) | 4.43 ± 1.56 | 6.04 ± 2.95 | 5.55 ± 2.19 | 3.55 ± 2.41 | 5.66 ± 3.95 | 4.25 ± 3.43 |

| TW (J) | 10,656 ± 1260 | 10,274 ± 1140 | 10,357 ± 1009 | 10,001 ± 1382 | 10,322 ± 1310 | 10,463 ± 1100 |

| VO2 (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 42.3 ± 4.76 | 41.0 ± 4.85 | 40.5 ± 4.51 | 44.4 ± 11.5 | 42.7 ± 7.24 | 44.5 ± 9.02 |

| VO2 (L·min−1) | 1.74 ± 0.16 | 1.75 ± 0.17 | 1.69 ± 0.30 | 1.74 ± 0.18 | 1.79 ± 0.19 | 1.80 ± 0.23 |

| VCO2 (L·min−1) | 1.90 ± 0.19 | 1.73 ± 0.16 † | 1.64 ± 0.24 † | 1.97 ± 0.24 ‡ | 1.84 ± 0.18 †‡ | 1.81 ± 0.24 †‡ |

| VE (L·min−1) | 93.6 ± 9.67 | 95.9 ± 9.39 | 97.1 ± 14.1 | 90.5 ± 8.63 | 91.4 ± 7.04 | 96.2 ± 11.6 |

| HR (bpm) | 169 ± 11.3 | 173 ± 11.6 | 177 ± 12.2 † | 169 ± 10.7 | 173 ± 10.7 | 178 ± 11.2 † |

| O2Hb (a.u.) | −578 ± 409 | −450 ± 456 | −256 ± 555 † | −547 ± 586 | −241 ± 672 | −54.3 ± 642 † |

| HHb (a.u.) | 336 ± 388 | 528 ± 473 † | 454 ± 571 | 361 ± 266 | 581 ± 248 † | 518 ± 325 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barata, C.F.; Reis, J.F.; Moncóvio, S.A.; Vilares, A.M.; Bento, A.M.; Rosa, C.H.; Espada, M.C.; Matias, C.N.; Monteiro, C.P. Acute Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation Improves Repeated Sprint Ability in Recreational Female Football Players: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010353

Barata CF, Reis JF, Moncóvio SA, Vilares AM, Bento AM, Rosa CH, Espada MC, Matias CN, Monteiro CP. Acute Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation Improves Repeated Sprint Ability in Recreational Female Football Players: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010353

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarata, Cláudia F., Joana F. Reis, Sofia A. Moncóvio, Arminda M. Vilares, André M. Bento, Cristóvão H. Rosa, Mário C. Espada, Catarina N. Matias, and Cristina P. Monteiro. 2026. "Acute Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation Improves Repeated Sprint Ability in Recreational Female Football Players: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010353

APA StyleBarata, C. F., Reis, J. F., Moncóvio, S. A., Vilares, A. M., Bento, A. M., Rosa, C. H., Espada, M. C., Matias, C. N., & Monteiro, C. P. (2026). Acute Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation Improves Repeated Sprint Ability in Recreational Female Football Players: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010353