Abstract

Fast and accurate indoor occupancy detection is critical for energy efficiency and emergency rescue in the fields of smart building and indoor positioning. However, existing image-based indoor occupancy detection models often neglect small human targets and suffer from large parameters, compromising detection accuracy, real-time performance, and deployment on resource-constrained devices. To address these issues, this study proposes a modified lightweight indoor occupancy detection model based on YOLO v8. Firstly, a patch expanding layer is added to the neck of the YOLO v8 model for reshaping the feature maps of adjacent dimensions into higher-resolution feature maps. Secondly, the standard convolution in the original neck is replaced with the GSConv, boosting the non-linear representation by adding DSC layers and a shuffle operation, efficiently preserving hidden connections between channels. Additionally, the VoV-GSCSP in the neck is designed to adopt one-shot aggregation with GS bottlenecks based on GSConv, followed by a cross-stage partial network module. Experiments on the SCUT-HEAD dataset show the modified lightweight YOLO v8 reduces parameters by 9.3% and computational complexity by 8.6%, while increasing mAP50 by 1.4% compared to the baseline. The proposed model can detect indoor occupancy in a fast and precise manner.

1. Introduction

With the elevation of societal prosperity, the share of building energy consumption in the overall social energy consumption has gradually increased. Building energy consumption is mainly used to maintain the operation of various environmental systems, like the HVAC, ventilation systems, lighting systems, and so on [1,2,3].

However, traditional control strategies for the environmental systems typically set time and status based on static energy demands, lacking intelligence and adaptability. The key to solving this problem lies in obtaining accurate occupancy information. By integrating real-time occupancy information, environmental control systems can dynamically adjust the operating parameters of HVAC and lighting systems to better reflect actual indoor demand. Within the HVAC system, this adaptive capability is particularly evident in the operation of an air handling unit (AHU), which serves as the core component responsible for ventilation, filtration, heating, and cooling. An AHU responds directly to occupancy-driven variations in sensible heat load and required ventilation rates; therefore, accurate occupancy information enables them to modulate supply air volume, temperature, and outdoor-air intake more efficiently, ultimately improving energy utilization while maintaining indoor thermal comfort and air quality [1,4]. Recent studies have further demonstrated the value of occupancy-related information in AHU operation. For example, Wang [5] introduced a data-generation approach to address data imbalance issues in real operational AHU fault diagnosis, which observed that occupancy-driven variations in system load significantly affect diagnostic performance. In addition, Wang [6] evaluated the cross-building transferability of an attention-based Automated Fault Detection and Diagnosis (AFDD) model for AHU, showing that building-specific occupancy patterns influence diagnostic performance. These studies highlight that capturing accurate occupancy information is not only essential for intelligent environmental control, but also closely tied to robust AHU operation and reliable diagnostic performance. From an application perspective, energy efficiency is a critical requirement for edge-deployed indoor occupancy and people counting systems that rely on continuous visual perception under limited computational resources. Occupancy-aware person detection has therefore become a core component for indoor occupancy estimation in smart buildings and surveillance applications [7,8], where both accuracy in dense small-target scenes and computational efficiency are essential for real-time and long-term deployment on resource-constrained devices [9].

Moreover, real-time occupancy detection is crucial for indoor emergency rescue [10,11], providing support for planning feasible escape routes for each person inside. Thus, the detection of occupancy information is closely related to indoor localization capabilities and is fundamental to achieving these goals. The occupancy information in buildings can be detected through the following means: sensor networks, Wi-Fi, PIR, smart meters, and cameras [12,13,14]. Among them, means such as cameras can obtain occupancy information including precise location data, track the positions of people in specific areas or rooms, and provide assistance for indoor positioning. Compared with other methods, image-based occupancy information detection methods can not only sense fine-grained information, but also provide better detection accuracy as well as real-time capability, providing precise pixel coordinates for indoor passive visual positioning and achieving positioning accuracy at the centimeter level.

Image-based indoor occupancy information detection models are mainly grouped into traditional machine learning methods as well as deep learning methods [15]. Specifically, traditional machine learning methods extract texture features from images using techniques such as local binary pattern (LBP) [16], Haar-like features [17], and histogram of oriented gradient (HOG) [18]. These extracted features are then classified and detected using machine learning classifiers like support vector machines (SVM) [19], decision trees [20], and adaptive boosting (Adaboost) [17]. Jia et al. [21] considered surveillance cameras as boundary sensors as well as utilized the HOG classifier based on the SVM to detect persons. In the classroom, Yang et al. [22] assessed the effectiveness of occupancy counting by employing PTZ cameras focused on facial detection. However, traditional machine learning methods often exhibit diminished recognition accuracy and poor robustness, as they cannot adequately capture the complexity and diversity of objects during image feature processing.

Recently, deep learning methods (e.g., Transformer [23] and CNN) have attained state-of-the-art effectiveness in object detection tasks. To address the challenges faced when performing person detection under overhead fisheye cameras, Chen et al. [24] introduced an innovative method called group equivariant transformer (GET). Based on the YOLO model, Meng et al. [25] developed a CNN-based, end-to-end system for predicting dynamic occupancy loads in building spaces and enabling real-time estimation of occupancy loads. To approximate room occupancy count, Mutiset et al. [26] developed a multi-stream deep neural network for identifying human activities, which employed the YOLOv3 network for object detection. Choi et al. [27] assessed the effectiveness of YOLOv5 algorithm within two office environments, concurrently gauging user approval to the technology through survey-based feedback. Nevertheless, due to the anchor-based mechanism (ABM) adopted by YOLO v5, the model generalization capacity was limited. In the occupancy detection task, the imbalance between positive as well as negative examples arose due to the significant difference in the quantity of both positive and negative samples.

Introduced in January 2023 by the YOLO v5 team, YOLO v8 is a continuation of the YOLO family, supporting multiple image processing tasks, like object detection, instance segmentation, and image classification. Compared to the YOLO v5, the YOLO v8 replaces anchor-based with anchor-free. As a result, YOLO v8 is easier for resolving the challenge of positive, as well as negative, sample imbalance and shows better generalization ability. Currently, the YOLO v8 based deep learning model is being utilized in diverse research domains, such as corn leaf disease identification [28], marine oil spill detection [29], dangerous behavior detection [30], etc. Within this research, YOLO v8 is innovatively used in the field of indoor occupancy detection. However, due to the relatively small target, the persons in indoor scenes often exhibit weak feature expression capacity, which increases the challenge of detection. The model has fewer usable features, which make it difficult to accurately identify the information of small target persons. Thus, the one-stage method can be combined with other modules to achieve fast detection and improve detection accuracy.

In order to acquire richer information about the features of small objects, Kisantal et al. [31] introduced a copy and paste approach, which enhances detection effectiveness by repeatedly copying as well as pasting small objects. Meanwhile, Chen et al. [32] attained superior enhancement effects by scaling and stitching images together. To cope with the constraints of small object resolution, Romano et al. [33] suggested a super-resolution method that allows the neural network to learn the mapping relationship between low-resolution images and their corresponding high-resolution counterparts. Although data augmentation and super-resolution techniques help mitigate the challenges of small objects with limited information and low resolution to some extent, they inevitably introduce additional computational overhead and increase training and inference complexity. The patch expanding layer, which was suggested by Cao et al. in 2021 [34], captures more detailed information by improving the resolution of the input feature map and increases the visibility and detectability of small target persons. Although effective, the patch expanding layer has mainly been applied in medical image segmentation to enhance the resolution of pathological tissue features, and it has not yet been integrated into YOLOv8 for capturing the spatial details of small and densely distributed human heads in indoor scenes. In the context of indoor head detection and occupancy estimation, several studies have reported improved detection accuracy by adopting deeper networks, multi-stage detection pipelines, or additional preprocessing modules [8,35]. However, due to the large model size, increased parameter count, and high floating-point operations (FLOPs) of these enhanced approaches, it remains difficult to achieve a satisfactory balance between detection effectiveness and resource consumption, which poses significant challenges for deployment on edge devices in smart-building environments. Instead of relying on heavier models or computationally expensive enhancement strategies, this work focuses on improving the representation of small indoor targets within the lightweight YOLOv8 framework. Specifically, the original upsampling layer in YOLOv8 is replaced with a patch expanding layer, which enables feature map resolution enhancement and feature dimension expansion without introducing additional convolution or interpolation operations.

To attain efficient real-time detection of indoor persons and better accommodate complex actual indoor application environments, it is necessary to boost the capability of the model to extract person features and decrease its complexity. Yang et al. [36] suggested Maize-YOLO, an adaptation of YOLOv7 that incorporated the CSPResNeXt-50 and VoV-GSCSP modules to achieve a balance between accuracy and speed for maize pest detection. But its intended targets are large and low-density pests, which differ fundamentally from the small and overlapping person targets in indoor environments. Liu et al. [37] proposed Small-YOLOv5 based on the YOLOv5s model. In this approach, GSConv is introduced to reduce model parameters for rice growth–stage recognition; however, it lacks modules to compensate for the feature loss caused by lightweight convolution and is not applicable to the anchor-free paradigm of YOLOv8. Small-YOLOv5 not only replaced the backbone network of YOLOv5s with MobileNetV3, but also introduced GSConv [38] to replace the standard convolution, thereby reducing the model size as well as the quantity of model parameters. Nevertheless, these modifications are still not directly applicable to the YOLOv8 framework. Wang et al. [39] proposed the lightweight PDSI-RTDETR model, which integrated GSConv and VoV-GSCSP for tomato maturity detection. Yet it did not address the loss of spatial details in small target detection and was built upon the RT-DETR framework rather than YOLOv8. In contrast to prior methods, the improved lightweight YOLOv8 developed in this study introduces scenario-specific enhancements for indoor occupancy detection through the coordinated integration of three complementary modules. The patch expanding layer is incorporated into the YOLOv8 neck to replace conventional upsampling, thereby alleviating spatial detail loss in small target detection. GSConv is employed to substitute standard convolutions, enabling lightweight computation while preserving representational capacity. Additionally, the combination of VoV-GSCSP and GSConv forms a refined slim-neck structure that compensates for the correlation loss induced by GSConv alone and facilitates cross-stage feature aggregation for dense indoor targets. Rather than a simple module assemblage, this design offers a targeted solution to the dual challenges of small target detection accuracy and resource-constrained deployment in smart-building environments, which conventional single-module or cross-domain optimization techniques fail to adequately address.

In addition to the application constraints mentioned above, several other factors can affect detection accuracy, such as occlusion by furniture or other people, densely overlapping targets, scale distortion caused by variations in camera height and viewing angle, and privacy concerns associated with visible-light imaging. These factors should be carefully taken into account in practical target detection tasks.

Building on this foundation, this research intends to overcome the challenges of low detection accuracy for the small target persons and to decrease the complexity of the model when detecting persons in indoor environments. An object detection model based on the YOLOv8n architecture was developed, which is called improved lightweight YOLO v8. The following highlights the primary contributions of this research endeavor:

- (1)

- To resolve the challenge of detecting small target persons in indoor environments, the patch expanding layer is introduced into the YOLO v8 model. The patch expanding layer is added to the neck of the YOLO v8 model to substitute the original upsampling module. The patch expanding layer achieves efficient upsampling by reshaping the feature maps, which aids in the recovery of spatial data lost during the encoding process and enhances the detection accuracy for small indoor target persons.

- (2)

- To decrease the parameters of the model and save computational costs, this study utilizes the GSConv to substitute the traditional convolution in the YOLOv8’s neck network. The computational cost of GSConv is roughly half that of standard convolution (SC), yet its contribution to the method’s learning ability is comparable to the SC, which can significantly decrease model computational complexity and parameters while preserving model accuracy.

- (3)

- To more quickly and accurately identify indoor persons on resource-constrained equipment, this study replaces the C2f modules with the VoV-GSCSP modules to optimize the neck structure of the YOLO v8 model. The improved neck structure not only effectively balances the reduction in model computational complexity with the enhancement of detection accuracy but also facilitates the deployment of detection algorithms on devices with limited performance.

- (4)

- To fully certify the effectiveness of the indoor person detection model suggested in this research, a correlation experiment was conducted on the SCUT-HEAD dataset as well as the Brainwash dataset. When compared to the current mainstream algorithms, the experimental results of the suggested model indicate that it achieves satisfactory detection effectiveness on both datasets.

2. Related Work

The indoor person detection network suggested in this study is a novel improvement of the constituents based on the basic YOLO v8’s architecture. YOLO v8 demonstrates superior performance by integrating numerous advantages of the YOLO series algorithms and maintaining high accuracy while preserving real-time effectiveness. Consequently, this research takes YOLO v8 as the object to develop a more suitable indoor person occupancy detection algorithm.

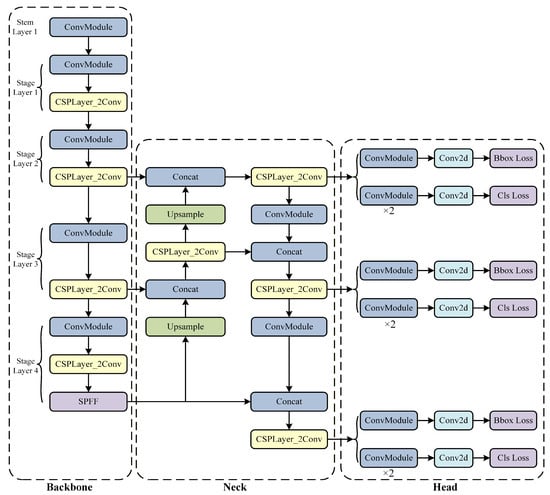

The input segment, a backbone network, a neck, and an output segment are comprised in the YOLO v8 model, which is a fast one-stage method for object detection. The basic structure of the YOLO v8 model is described in Figure 1. The central structures of the YOLO v8 network comprise the backbone network as well as the neck module. Multiple Conv and C2f modules process the input image to obtain feature maps at various scales. In fact, the main residual learning module is the C2f module, which is an enhanced version of the C3 module. The SPPF module processes the output feature maps by utilizing pooling with different kernel sizes to combine them, and subsequently the results are fed into the neck layer.

Figure 1.

Detailed structure of YOLO v8.

The neck layer of YOLO v8 can boost the model’s feature fusion capacity by employing the structure of FPN combined with PAN. The network becomes better equipped by adopting this method to fuse features from objects of various scales, consequently improving its detection effectiveness on objects at different scales. In its detection head architecture, YOLO v8 follows the common approach of separating the classification head from the detection head. It encompasses loss calculation as well as object detection box filtering. The TaskAlignedAssigner [40] method serves to determine positive as well as negative sample assignments in the loss calculation process. Classification as well as regression are the two components involved in the loss computation. The regression branch utilizes distribution focal loss as well as CloU loss functions, whereas the classification branch makes use of binary cross-entropy loss [41].

The YOLO v8 employs decoupled heads to generate prediction boxes for forecasting classification scores as well as regression coordinates. Ultimately, a task-aligned assigner in YOLO v8 is employed to compute a task alignment metric employing the classification scores as well as regression coordinates. By combining the classification scores with the intersection over union value, the task alignment metric enables the optimization of both classification and localization.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of the Architecture

The direct application of YOLO v8 to indoor person occupancy detection tasks still faces issues such as low accuracy and poor real-time performance. Inspired by YOLO v8, this paper proposes a model named improved lightweight YOLO v8, which aims to decrease the count of parameters and boost the detection accuracy. Unlike the original YOLO v8, the detection accuracy of improved lightweight YOLO v8 has been improved, and most indoor persons can be detected.

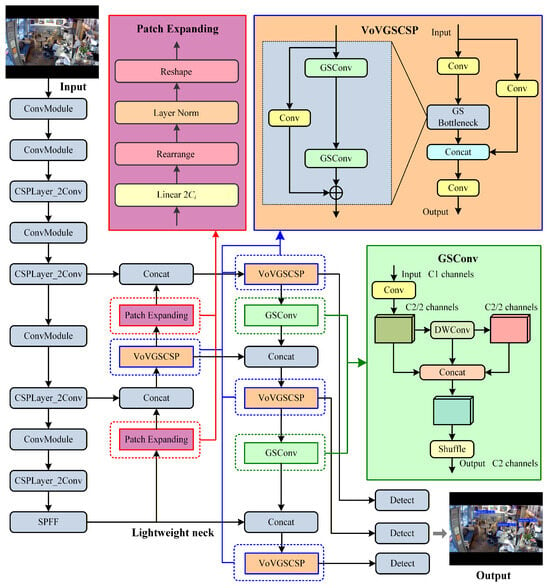

Figure 2 depicts the architecture of the improved lightweight YOLO v8. In the neck stage, improved lightweight YOLO v8 employs the patch expanding layer to replace the original upsample operation. Meanwhile, inspired by the slim-neck design paradigm, by utilizing GSConv and VoV-GSCSP, a brand-new lightweight neck structure is designed in this research, which significantly decreases the count of model parameters as well as size, while ensuring decoding accuracy.

Figure 2.

The basic structure of the improved lightweight YOLO v8 network.

3.2. Patch Expanding Layer Replace the Upsampling of YOLO v8

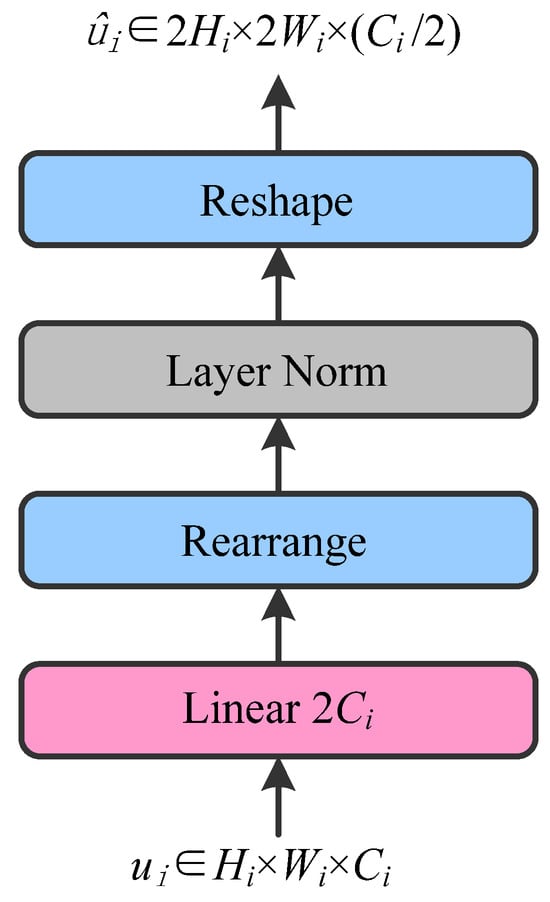

Due to the relatively small size of people in indoor scenes, their pixel occupancy tends to also be small, resulting in a weaker ability to express features. For this issue, this research suggests a solution to resolve the difficulty of indoor small target person detection. Inspired by swin-transformer, this paper chooses to use the patch expanding layer for upsampling operations in the original YOLO v8 model for indoor small target person detection. Different from the original upsampling module of YOLO v8, the patch expanding layer achieves efficient upsampling by reshaping the feature maps, which not only helps restore the spatial information lost during encoding due to pooling or merging operations but also allows the model to capture more details. Thus, this enhances the detection accuracy for small indoor target persons. To address the interface between CNN feature maps and reshaping operations, the input 4D CNN feature tensor (N × C × H × W) is first flattened into a 3D token sequence (N × (H × W) × C) while preserving the original spatial order of adjacent pixels. This ensures that the local receptive field correlations inherent in CNN features are maintained. A linear projection layer then doubles the channel dimension (e.g., from 8C to 16C), acting as a pre-encoding step to compress redundant information and facilitate uniform spatial redistribution in subsequent reshaping.

As shown in Figure 3, it exhibits the structure of the patch expanding layer. Considering a patch expanding layer as an illustrative example, a linear layer is employed to double the feature dimension of the input features, which originally have dimensions (W/32×H/32×8C), to (W/32×H/32×16C). Subsequently, the paper employs the rearrange operation to double the resolution of the input features while decreasing the feature dimension to one-quarter of its original input dimension, specifically transitioning from (W/32×H/32×16C) to (W/16×H/16×4C). Critically, this rearrange operation avoids aliasing by uniformly splitting the expanded channel dimension (16C) into four subsets (4 × 4C), each corresponding to one of the 2 × 2 new spatial positions. This inheritance-based mapping ensures that newly generated pixels derive features directly from the original CNN local regions rather than interpolated approximations, thereby preserving fine-grained spatial details and preventing high-frequency artifacts. In addition, to suppressing noise amplification, which would otherwise exacerbate aliasing, calibration steps are added at key nodes in the layer. First, Layer Normalization (LN) is used to balance the feature distribution across channels, ensuring uniform feature intensity at each spatial position after splitting. Second, a ReLU activation is applied after reshaping to filter low-amplitude noise and strengthen the semantic consistency of new features, indirectly suppressing aliasing artifacts. The definition of patch expanding is given by Equation (1):

where ui and ûi represent the feature maps before and after upsampling at the ith stage, respectively. C represents a linear transformation responsible for doubling the channel dimension. LN (∙) represents layer normalization. RA (∙) denotes the rearrange operation, and RS (∙) denotes the reshape operation.

Figure 3.

Patch expanding layer details.

3.3. Improved Lightweight Neck Inspired by the GSConv and VoV-GSCSP

The growing proliferation of deep learning methods in practical applications has created a pressing need for algorithm lightweighting. Although YOLO v8 exhibits outstanding performance in object detection tasks, its operational efficiency on lightweight devices commonly used in indoor person detection is hindered by its relatively large model size. In resource-constrained environments, the need to refine as well as to lightweight YOLO v8 becomes increasingly urgent. Optimizing the YOLO v8 model by decreasing model size and improving computational efficiency is crucial for effectively addressing the practical requirements of indoor person detection. The lightweight architecture both supports real-time detection on embedded devices and lowers costs, thus boosting the system’s practical usability. To attain balanced performance across diverse scenarios during the lightweighting of YOLO v8, it is essential to comprehensively evaluate metrics such as model accuracy, power consumption and speed. Pivotal strategies for lightweighting consist of adopting more efficient network structures, reducing parameter complexity.

The YOLO v8 model employs many standard convolutions as well as C2f modules to improve accuracy, but this improvement is accompanied by a decrease in speed and an increase in model parameters. To diminish the model’s complexity without compromising its accuracy, inspired by the slim-neck design paradigm, this study designs a lightweight neck structure for YOLO v8 model by applying the lightweight convolutions GSConv as well as the VoV-GSCSP structure. The slim-neck structure is designed as a coordinated integration of GSConv and VoV-GSCSP, where computational efficiency and feature representation are jointly considered, rather than as a collection of independent module replacements.

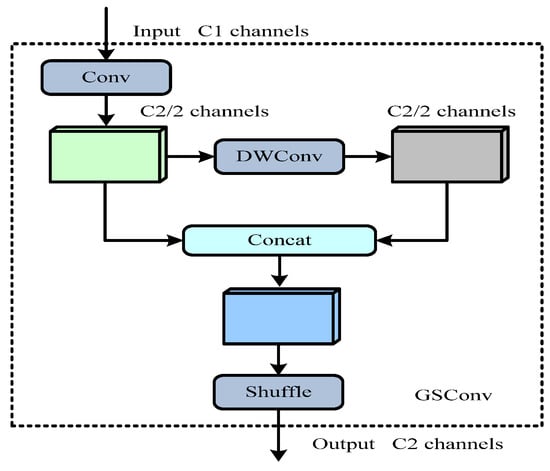

3.3.1. Gsconv Replace the Traditional Convolution of YOLO v8’ Neck

The GSConv lightweight convolution module was suggested by Li et al. [38]. The GSConv is a key module in the lightweight neck, which reduces computational complexity by decreasing redundant information and compressing unnecessary repetitive information. The GSConv convolution is a lightweight convolution. Figure 4 displays the structure of GSConv convolution, which contains the standard convolution (SC), depthwise separable convolution (DSC) as well as shuffle operation.

Figure 4.

GSConv convolution operation.

The input channel and output channel of GSConv convolution are numbered C1 and C2, respectively. Specifically, a standard convolution decreases the input channel number by half to C2/2 at first; Subsequently, the channel number keeps unchanged through DSC; Furthermore, the result produced by the first convolution is concatenated and shuffled with the structure after depthwise separable convolution. During the last shuffle operation, channel information is evenly shuffled to guarantee the effective preservation of multi-channel data.

The shuffle operation is employed to converge the information produced by SC (channel dense convolution operation) into each channel of DSC. The shuffle serves as a unified blending strategy, capable of ensuring the information from SC is completely converted into DSC by exchanging local feature information across different channels. Below is the complexity of the three convolutional models:

where signifies the count of input channels, signifies the count of output channels, K signifies the convolution kernel size, while H and W denote the height and width of the feature map, respectively, representing its spatial dimensions. The GSConv’s complexity is approximately half (0.5) that of SC. In the neck network, this research employs the GSConv to substitute classical convolutions, so as to decrease computational effort while preserving more local information of the models.

3.3.2. VoV-GSCSP Module Replace the C2f Module of YOLO v8’ Neck

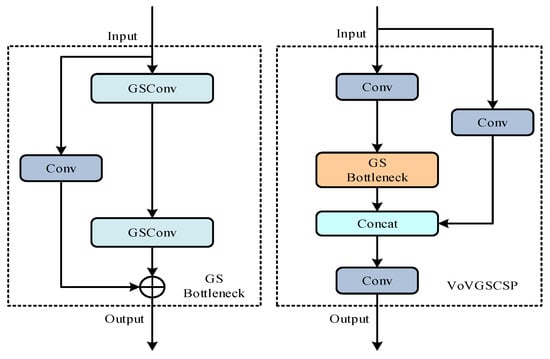

For the purpose of enhancing accuracy and decreasing the complexity of models, this study utilizes the VoV-GSCSP module to take the place of four C2f modules in the YOLO v8’ neck. VoV-GSCSP is a novel computational module that enhances the efficiency and accuracy of lightweight convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Built on GSConv, VoV-GSCSP can significantly reduce computational complexity and inference time through efficient feature fusion and utilization strategies. The module uses GSConv as the core and utilizes GSConv for feature reorganization to enhance feature representation. VoV-GSCSP reduces redundant computation and improves feature utilization efficiency through cross-stage feature fusion, which enables the network to share and reuse features across different stages, thus reducing the network computational burden. VoV-GSCSP also employs a partial-network design, which uses only a portion of the network to process specific inputs rather than the entire network. This approach further enhances the network’s overall efficiency. Figure 5 exhibits the elaborate architecture of the VoV-GSCSP module, which consists of three convolution operations as well as a GS bottleneck. It is noteworthy that the GS bottleneck consists of a classical convolution and two GSConvs in series.

Figure 5.

The architecture of the GSbottleneck module and VoV-GSCSP module.

In the neck network, this study employed GSConv modules to substitute the classical convolutions as well as utilized the VoV-GSCSP modules to substitute the C2f modules. This replacement not only achieves information aggregation across stages and decreases model complexity but also enhances inference speed without compromising instance segmentation accuracy. This paper achieves the required neck structure for improved lightweight YOLO v8 by testing various methods and flexibly utilizing the GSConv, GSbottleneck, and VoV-GSCSP, and verifies the effectiveness of this structure through experiments.

3.4. Indoor Occupancy Detection Strategy

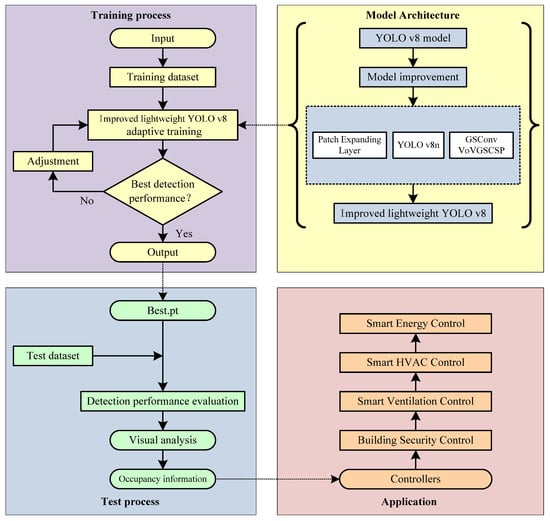

More and more scholars are utilizing image analysis to detect room occupancy rates, in order to control environmental systems such as lighting and HVAC in buildings. This approach holds significant energy-saving potential in the field of building energy efficiency. Figure 6 demonstrates the workflow for indoor occupancy detection, which utilizes an improved lightweight model derived from YOLO v8.

Figure 6.

The structure of a novel lightweight indoor occupancy detection model based on improved YOLO v8.

Firstly, to tackle the issue of detecting small target persons in indoor environments, this paper employs the patch expanding layer to replace the original upsampling module in the neck model of YOLOv8. Furthermore, to reduce the parameters of the model and save computational costs, this paper utilizes the GSConv to substitute the traditional convolution in the YOLOv8’s neck network. Through the above improvements, we have obtained the improved lightweight YOLO v8. Subsequently, the improved lightweight YOLOv8 model was applied to the training process.

In the training process, the experimental dataset, which is used as the input, is partitioned into the training dataset as well as the test dataset. Then, the training dataset is input into the improved lightweight YOLO v8 network. After the training is completed, a PR curve for this training will be generated along with two weights: best.pt and last.pt. Among these, best.pt represents the best weights from this training, while last.pt corresponds to the weights from the final epoch.

Typically, best.pt is used as the training weights for validation on the test set. In the test process, the test dataset and best.pt are used to evaluate the performance of indoor persons and conduct visual analysis of the results. By using the best.pt model to capture indoor occupancy information for managing environmental equipment, energy efficiency can be maximized and energy waste decreased.

In practical deployment, camera placement is crucial for maintaining sufficient resolution of small indoor targets. Ceiling-mounted cameras with wide field of view and appropriate height help reduce occlusion, while lightweight PTZ setups suit sparse environments. Real-time occupancy monitoring on edge devices typically requires ≥30 fps and <100 ms latency, and the lightweight design of the proposed model facilitates meeting these constraints.

4. Experiment and Result Analysis

4.1. Comparison Method and Parameter Setting

This study employed the Pytorch 1.8.0 deep learning framework to train 100 epochs for each model on the SCUT-HEAD dataset as well as the brainwash dataset for the occupancy detection issue. The AdamW [42] optimizer was employed for parameter optimization. The operating system of this experimental platform was a 64-bit Windows operating system, the GPU was NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti 16 GB and was used to train the detection model.

This research utilizes parameters, FLOPs, and mean average precision (mAP) to assess the ability of YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, and the baseline model YOLO v8n to detect persons. To fairly compare the performance of improved lightweight YOLO v8 with other algorithms, experiments in this study were conducted in an identical experimental environment, with detailed training hyperparameters listed in Table 1. Considering GPU memory constraints and training stability introduced by the multi-scale neck structure, the batch size was set to 24 for all models to ensure fair comparison.

Table 1.

Training hyperparametric configuration.

To ensure the traceability and interpretability of the lightweight improvement strategies (i.e., patch expanding layer, GSConv, and VoV-GSCSP) proposed in this study, the comparison experiments are mainly conducted on models of the same lightweight scale (YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, and YOLOv8n) with consistent architecture paradigms. Although other lightweight detectors, such as YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv7-lite, and YOLOv8s, are also relevant baselines, these models follow different scaling strategies and backbone-neck design choices from YOLOv8n, which makes it difficult to clearly attribute performance differences to the proposed lightweight neck modifications. Similarly, lightweight detectors including NanoDet, PP-YOLOE-tiny, and EfficientDet-D0 adopt distinct detection heads, feature pyramid structures, or training paradigms, whereas lightweight transformer-based detectors introduce global self-attention mechanisms and token-based feature representations; these heterogeneous architectural assumptions differ substantially from the convolutional design of YOLOv8 and would reduce the interpretability of a controlled comparison. While YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 have been released as newer iterations of the YOLO series, they are not included in the comparison set for two key reasons. First, the core architecture of YOLOv9 (with its GELAN feature fusion layer) and YOLOv10 (with its NMS-free post-processing mechanism) differ significantly from YOLOv8; introducing them would lead to ambiguity in attributing performance differences to either the lightweight strategies in this study or the fundamental architectural innovations of the new models, thus undermining the rigor of verifying the independent contribution of each improvement module. Second, relevant prior studies have confirmed that YOLOv8 still maintains state-of-the-art (SOTA) comprehensive performance in indoor occupancy detection tasks, as its anchor-free mechanism and balanced encoder–decoder structure are more adaptable to small-target indoor human detection scenarios compared with the newer versions that are optimized for general object detection rather than scenario-specific lightweight demands.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

Floating-point operations (FLOPs), mean average precision (mAP), and parameters are adopted as evaluation indicators for effective assessment. Parameters serve to describe the size of the model, which represent the total count of parameters to be trained in model training. In addition, FLOPs and parameter count are used as architecture-level indicators to evaluate model efficiency and computational complexity. mAP is calculated by averaging the AP values of all classes to indicate the accuracy of the model prediction. The mAP@0.5 represents the mAP value with an intersection over union (IoU) threshold of 0.5, while mAP@0.5:0.95 denotes the average mAP at different IoU thresholds—from 0.5 to 0.95 in increments of 0.05. The AP is defined as the area under the PR curve, while the mAP is obtained by averaging the AP values across all categories, as shown in Equations (5) and (6).

where Precision (P) signifies the ratio of samples predicted as positive that are actually positive, while Recall (R) denotes the proportion of actual positive samples among the predicted positive samples, relative to the total number of positive samples in the entire dataset. The calculation formulas for P and R are detailed below:

Rather than emphasizing hardware-dependent inference speed, which may vary significantly across different platforms, this study focuses on architecture-level efficiency indicators, such as FLOPs and parameter count, to provide a more hardware-agnostic and reproducible evaluation of lightweight design.

4.3. Experimental Dataset

4.3.1. The SCUT-HEAD Dataset

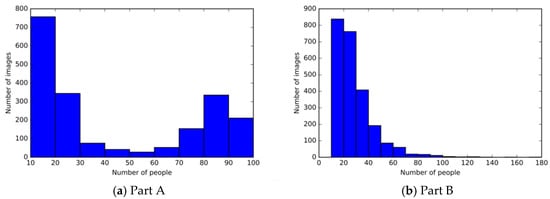

As a large-scale dataset for head detection, the SCUT-HEAD dataset [7] consists of 4405 images with 111,251 heads labeled. The average density of heads in this scene is extremely high (the average head density per image is about 25.2), which makes this dataset particularly challenging. The figures in Figure 7a,b depicts that the dataset comprises two parts. Part A comprises 2000 images, with 67,321 head annotations. Part B includes 2405 images, which are obtained from internet crawlers and feature 43,930 head annotations. The SCUT-HEAD dataset are segregated into the training dataset as well as test dataset. And the number of images with different numbers of people in the dataset can also be observed in Figure 8. In this study, following the methods of Zhang et al. [43] and Hou et al. [44], the SCUT-HEAD dataset is evaluated as a whole to assess the overall robustness and generalization of the proposed method, reflecting its general detection capability in different indoor scenarios.

Figure 7.

The sample of SCUT-HEAD. (a) Part A comprises 2000 images, with 67,321 head annotations; (b) Part B includes 2405 images, which are obtained from internet crawlers and feature 43,930 head annotations.

Figure 8.

The composition of SCUT-HEAD. (a) The composition of SCUT-HEAD of Part A; (b) the composition of SCUT-HEAD of Part B.

4.3.2. The Brainwash Dataset

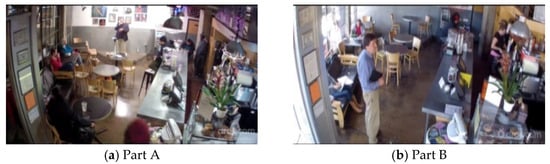

The Brainwash dataset is an extensive public dataset specifically designed for head detection tasks. This dataset is captured in crowded scenes where the average head count is large, averaging at approximately 7.89 persons. Given the extensive size of the original dataset, the dataset employed in this experiment is a randomly selected subset from the brainwash dataset [8]. The dataset comprises 1414 images for the training dataset as well as 353 images for the test dataset. The sample from the brainwash dataset is depicted in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Samples of the Brainwash dataset. (a) Part A comprises 1414 images for the training dataset; (b) part B includes 353 images for the test dataset.

4.4. Experiments and Comparisons

4.4.1. Experiment on SCUT-HEAD Dataset

- (1)

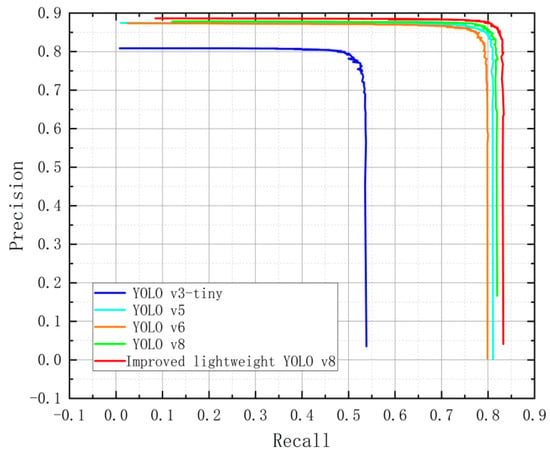

- Training result: To validate the rationality and correctness of the designed model, this paper records the Precision-Recall (PR) curves of the training processes for YOLO v3-tiny, YOLO v5, YOLO v6, the baseline YOLO v8n, and the proposed improved lightweight YOLO v8. Each line in the curve represents a different model, with the X-axis denoting Recall as well as the Y-axis denoting Precision. From Figure 10, it is evident that improved lightweight YOLO v8 significantly outperforms the other models, especially at higher Recall levels, where Precision remains high. YOLO v8, YOLO v5, and YOLO v6 also perform well, but their precision decreases as the Recall approaches higher values. In contrast, YOLO v3 performs relatively poorly, particularly when the Recall reaches 0.5, where its Precision is noticeably less than that of the other methods. The experimental results demonstrate that the improved lightweight YOLO v8 keeps high precision at elevated recall rates, performing excellently in indoor occupancy detection tasks. It not only decreases its own model complexity but also demonstrates its effectiveness as well as reliability in small object detection.

Figure 10. Comparison of PR curves for different models on SCUT-HEAD dataset.

Figure 10. Comparison of PR curves for different models on SCUT-HEAD dataset.

- (2)

- Ablation experiment: The ablation experiments were designed to verify the independent contribution of each improvement module and their synergistic effect, with the baseline model being the original YOLOv8n (without any optimization), as shown in Table 2. First, from the perspective of single-module ablation: (1) When only GSConv is applied to replace the standard convolution in the neck, the model parameters decrease from 3,005,843 to 2,916,083 (a reduction of 2.99%), but the mAP@0.5 drops from 0.877 to 0.863 (a decrease of 1.4%). This is because GSConv reduces computational complexity by splitting channels into standard convolution (SC) and depthwise separable convolution (DSC) branches, but lacks cross-stage feature aggregation capability, leading to the loss of deep-shallow feature correlation and thus reducing detection accuracy for small indoor human targets. (2) When only VoV-GSCSP is used to replace the C2f module (based on standard convolution instead of GSConv), the parameters decrease to 2,654,931 (a reduction of 11.68%), and the mAP@0.5 remains at 0.877 without degradation. This benefit comes from the one-shot aggregation and cross-stage partial network design of VoV-GSCSP, which enhances feature reuse and small-target perception, but its lightweight effect is limited by the retained standard convolution, and the mAP@0.5:0.95 still drops by 0.06 due to insufficient channel-level feature compression. Second, the synergistic effect of GSConv and VoV-GSCSP (i.e., the complete slim-neck structure) is prominent: When the two modules are combined, the model parameters are further reduced to 2,581,555 (a reduction of 14.12% compared to the baseline), and the mAP@0.5 rises to 0.893 (an increase of 1.6% compared to the baseline). The GSConv embedded in the GS bottleneck of VoV-GSCSP further reduces the computational burden of the module, while the cross-stage feature aggregation of VoV-GSCSP makes up for the feature loss of the single GSConv, forming a complementary mechanism between lightweight convolution and multi-scale feature fusion. This verifies that GSConv and VoV-GSCSP are mutually reinforcing in the slim-neck structure. The single application cannot balance lightweight and detection accuracy, while joint application achieves the optimal trade-off. Finally, the combination of the patch expanding layer and the slim-neck structure (GSConv + VoV-GSCSP) achieves the best performance: The model reaches an mAP@0.5 of 89.4% (an increase of 1.7% compared to the baseline), with parameters reduced by 9.3% (from 3,005,843 to 2,725,299) and computational complexity reduced by 8.6%. The patch expanding layer recovers the spatial details of small targets, and the slim-neck structure guarantees lightweight and feature representation capability, realizing the dual improvement of detection accuracy and deployment efficiency for indoor occupancy detection.

Table 2. The effectiveness of various methods on SCUT-HEAD dataset.

Table 2. The effectiveness of various methods on SCUT-HEAD dataset. - (3)

- Validation: To validate the advantage of improved lightweight YOLO v8 over other object detection methods, this research evaluates the effectiveness of several current state-of-the-art detection methods, such as DR-Net [45], Faster R-CNN [46], SANM [46], R-FCN [47], YOLOv3-tiny, YOLO v5, YOLO v6, baseline YOLO v8n, on the SCUT-HEAD dataset. According to Table 3, the verification results show that the effectiveness of the suggested model was better than that of the other methods for indoor person detection. Among the above models, improved lightweight YOLO v8 achieves the highest mAP50, reaching 89.4%, with 2,725,299 parameters and 7.4G FLOPs. Improved lightweight YOLO v8 achieves a mAP50 of 89.4%, which is 3.1% mAP50 higher than DR-Net and defeats FasterR-CNN by 3.74% mAP50. Compared to the mAP50 of SANM and R-FCN, improved lightweight YOLO v8 has improved by 1.17% and 5.9%, respectively. Compared to YOLO v3-tiny, improved lightweight YOLO v8 achieves a 26.2% improvement in mAP50 while decreasing the count of parameters by 9,402,879. In addition, compared to YOLO v6, improved lightweight YOLO v8 exhibits a 3.2% improvement in mAP50 and a reduction of 1,508,544 parameters, while when benchmarked against the baseline YOLO v8n, it demonstrates a 1.7% increase in mAP50 and a decrease of 280,544 parameters. Notably, the proposed method consistently improves detection accuracy while simultaneously reducing model parameters and computational complexity, demonstrating a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off. This improvement is particularly evident on the SCUT-HEAD dataset, which is dominated by small-scale indoor head instances and aligns well with the design motivation of the proposed lightweight neck structure. Although it is slightly inferior to YOLOv5 in terms of parameters and FLOPs, it adequately fulfills the requirements of real-time person detection. The ablation experiments reveal that the improved lightweight YOLO v8, which has been suggested in this study, not only guarantees the training accuracy but also decreases the algorithm volume and computational complexity, highlighting its practical value for lightweight indoor person detection scenarios.

Table 3. The effectiveness of different methods on SCUT-HEAD dataset.

Table 3. The effectiveness of different methods on SCUT-HEAD dataset.

Figure 11 demonstrates the final detection results obtained by the improved lightweight YOLO v8 on the SCUT-HEAD dataset. The model’s actual application results are represented by the prediction box. The model indicates the positions of people’s heads within the room, represented by blue boxes, while the values denote the probability of such detections. In fact, the probability’s increase corresponds to a greater accuracy in indoor person detection. As is illustrated in the images, indistinct and small people can be accurately detected.

Figure 11.

Detection results of the improved lightweight YOLO v8 on SCUT-HEAD dataset.

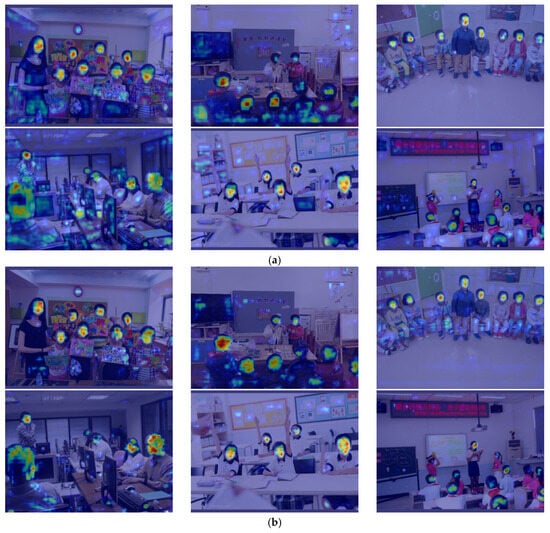

This study employed the Grad-CAM heatmap visualization approach to analyze the RoI of the model during the learning process. Indeed, Grad-CAM is a visualization approach that generates a heatmap to highlight the model’s focus areas. The darker the red part of the image, the greater focus the model gives to that part. As illustrated in Figure 12, the optimized model learns the correct features and can effectively concentrate on the head area of indoor persons, with a greater emphasis on these locations, fully demonstrating the performance of the enhanced model.

Figure 12.

The Grad-CAM heat map of YOLO v8 and improved lightweight YOLO v8 on SCUT-HEAD dataset. Red regions indicate higher contribution to the model prediction, while blue regions indicate lower contribution. (a) YOLO v8; (b) Improved lightweight YOLO v8.

4.4.2. Experiment on Brainwash Dataset

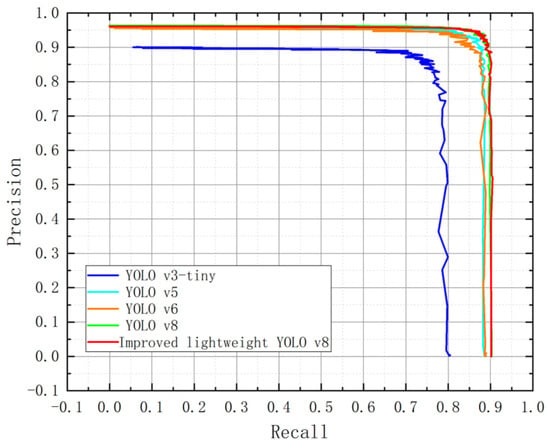

On the brainwash dataset, this paper also records the Precision-Recall (PR) curves of the training processes for YOLO v3-tiny, YOLO v5, YOLO v6, the baseline YOLO v8n, and the proposed improved lightweight YOLO v8. Figure 13 shows that although the PR curve of improved lightweight YOLO v8 is similar to that of the baseline YOLO v8n, it is still above those of the other comparison methods, revealing that the proposed improved lightweight YOLO v8 demonstrates good performance in maintaining training accuracy. YOLO v5 and YOLO v6 also perform relatively well, but their precision decreases when the recall reaches 0.8, falling below the levels of YOLO v8 and improved lightweight YOLO v8. YOLO v3 performs the worst, with its precision notably less than that of the other methods at high recall rates (close to 0.8).

Figure 13.

Comparison of PR curves for different models on Brainwash dataset.

To certify the superiority of improved lightweight YOLO v8 over other object detection models, this research evaluates the effectiveness of several current state-of-the-art detection algorithms, including YOLOv3-tiny, YOLO v5, YOLO v6, baseline YOLO v8n, on the brainwash dataset. The verification results are displayed in Table 4, which demonstrate that the suggested model was more effective than the other models for indoor person detection. Among the above models, improved lightweight YOLO v8 achieves the highest mAP50, reaching 91.7%. Compared to the mAP50 of YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv6 and baseline YOLO v8n, improved lightweight YOLO v8 has improved by 9.5%, 2.1% and 0.4%, respectively. Although the numerical improvement over the baseline YOLO v8n appears modest, it was achieved together with a noticeable reduction in model parameters and FLOPs. This indicates that the proposed slim-neck design is able to preserve and slightly improve detection accuracy under a reduced computational budget, which is particularly meaningful for deployment on resource-constrained devices. Meanwhile, despite being slightly inferior to YOLOv5 in terms of parameters and FLOPs, the proposed model adequately satisfies the requirements of real-time person detection. Overall, the results on the Brainwash dataset highlight the effectiveness of the proposed lightweight modifications in improving the accuracy-efficiency trade-off rather than pursuing large absolute accuracy gains.

Table 4.

The effectiveness of different methods on Brainwash dataset.

From a deployment perspective, the proposed model requires approximately 7.4 GFLOPs per inference and is designed for embedded GPU-based edge devices rather than ultra-low-power microcontroller platforms. With only 2.7 million parameters, the model significantly reduces memory consumption and facilitates deployment on resource-constrained devices. It should be noted that deployment feasibility is evaluated in the inference phase, where no backpropagation or gradient computation is involved. For typical indoor occupancy and person detection scenarios, moderate inference frame rates are sufficient, and under these conditions, the computational cost of the proposed model is acceptable while maintaining improved detection accuracy for small indoor targets. Furthermore, the final detection results can be seen in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Detection results of the improved lightweight YOLO v8 on Brainwash dataset.

5. Conclusions

This paper suggests a new lightweight indoor occupancy detection algorithm based on the improved YOLO v8, called improved lightweight YOLO v8, to overcome the challenge of detecting small target persons as well as to decrease model’s complexity. Firstly, based on the YOLO v8 model, this research incorporates the patch expanding layer to deal with the challenges of small target person detection. Furthermore, this paper substitutes the standard convolution in the original neck of YOLO v8 with the GSConv to save computational costs. Moreover, to decrease the complexity of the model, this study introduces the VoV-GSCSP in the neck section of YOLO v8 model, which is constructed using the one-shot aggregation method. The key distinction of the proposed method from existing YOLOv8 optimization approaches lies in its scenario-specific innovation achieved through the coordinated integration of three modules for indoor occupancy detection. The combination of the patch expanding layer, GSConv, and VoV-GSCSP does not constitute a simple stacking of components; rather, it represents a targeted architectural design that addresses the dual challenges of achieving high small target detection accuracy and enabling deployment under resource constraints in smart-building environments. These challenges cannot be effectively resolved by existing single-module enhancements or by optimization strategies developed for other application scenarios.

Additionally, to fully verify the effectiveness of the indoor person detection model suggested in this research, experiments are performed on the SCUT-HEAD dataset and Brainwash dataset. In comparison to the original method, the improved lightweight YOLO v8 exhibits higher detection accuracy and a smaller volume. Furthermore, when compared to the current mainstream algorithms, the suggested model still shows satisfactory detection effectiveness.

However, several limitations remain. Detection performance degrades under severe occlusion or dense overlap; camera height and angle variations introduce scale distortion; visible-light imaging raises privacy concerns; and generalization to diverse indoor scenes has not yet been fully validated. Thus, future work will focus on improving detection under occlusion, enhancing robustness to camera perspective changes, exploring privacy-preserving sensing such as infrared, and broadening indoor scene diversity with domain adaptation to strengthen generalization. In addition, the reduction in parameters and FLOPs also benefits embedded deployment by improving quantization efficiency and reducing inference latency on edge devices. Future work will further explore hardware-oriented optimization and enhance detection robustness in occluded and densely populated indoor scenes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and L.L.; Methodology, H.Z. and L.L.; Software, H.Z., L.L., Z.W. and L.B.; Validation, H.Z., L.L. and J.B.; Formal Analysis, H.L. and Z.W.; Investigation, H.Z., L.B. and G.Y.; Resources, J.B., H.L. and G.Y.; Data Curation, H.Z., L.L., Z.W. and L.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, H.Z., L.L. and J.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, H.Z., L.L., J.B., H.L., Z.W., L.B. and G.Y.; Visualization, L.L., H.L., Z.W. and L.B.; Supervision, H.Z., J.B., H.L. and G.Y.; Project Administration, J.B., Z.W., L.B. and G.Y.; Funding Acquisition, H.Z., J.B., H.L. and G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Innovation Technology Project of Higher School in Shandong Province, grant numbers 2022KJ204 and 2023KJ121; the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, grant numbers ZR2024MF148, ZR2021QF077 and ZR2024QD012; the Hebei Natural Science Foundation, grant number D2024523007; and the Hebei Yanzhao Huangjintai Talent Gathering Program Backbone Talent Project (Post doctoral Platform), grant number B2024005023.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository that does not issue DOIs. Brainwash dataset and SCUT_HEAD dataset were analyzed in this study. SCUT-HEAD dataset can be found at [https://github.com/HCIILAB/SCUT-HEAD-Dataset-Release] (accessed on 11 November 2025); Brainwash dataset can be found at [https://exhibits.stanford.edu/data] (accessed on 11 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions, which have greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jingxue Bi was employed by The 54th Research Institute of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Sayed, A.N.; Himeur, Y.; Bensaali, F. Deep and transfer learning for building occupancy detection: A review and comparative analysis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Mehmani, A.; Zhang, J. Deep learning-based real-time building occupancy detection using AMI data. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 2020, 11, 4490–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jiang, C.; Xie, L. Building occupancy estimation and detection: A review. Energy Build. 2018, 169, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Ma, X.; Liu, P.; Zhao, Q. MPSN: Motion-aware Pseudo-Siamese Network for indoor video head detection in buildings. Build. Environ. 2022, 222, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. A hybrid SMOTE and Trans-CWGAN for data imbalance in real operational AHU AFDD: A case study of an auditorium building. Energy Build. 2025, 348, 116447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Evaluating cross-building transferability of attention-based automated fault detection and diagnosis for air handling units: Auditorium and hospital case study. Build. Environ. 2026, 287, 113889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Z.; Cai, Z.; Xie, L.; Jin, L. Detecting heads using feature refine net and cascaded multi-scale architecture. In Proceedings of the 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Beijing, China, 20–24 August 2018; pp. 2528–2533. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.; Andriluka, M.; Ng, A.Y. End-to-end people detection in crowded scenes. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2325–2333. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D. CSRNet: Dilated convolutional neural networks for understanding the highly congested scenes. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 1091–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, M.; Jeon, J.; Han, K.S.; Cho, Y.S. Accurate Long-Term Evolution/Wi-Fi hybrid positioning technology for emergency rescue. ETRI J. 2023, 45, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, B.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Cao, H.; Huang, L.; Xing, H. Precise step counting algorithm for pedestrians using ultra-low-cost foot-mounted accelerometer. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 150, 110619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H. Occupancy detection and localization by monitoring nonlinear energy flow of a shuttered passive infrared sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 8656–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yuan, S. Indoor occupancy estimation method based on carbon dioxide. Ordnance Ind. Autom. 2018, 37, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, H.; Yao, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, M.; Yang, H.; Zhen, J.; Zheng, G. Inverse distance weight-assisted particle swarm optimized indoor localization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 164, 112032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Automatic detection of indoor occupancy based on improved YOLOv5 model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 2575–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleefah, S.H.; Mostafa, S.A.; Mustapha, A.; Nasrudin, M.F. Review of local binary pattern operators in image feature extraction. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2020, 19, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; An, Z. Vehicle recognition algorithm based on Haar-like features and improved Adaboost classifier. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 14, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, S.; Soleimani, P.; Li, K.F.; Capson, D.W. Analysis and comparison of FPGA-based histogram of oriented gradients implementations. IEEE Access. 2020, 8, 79920–79934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisner, D.A.; Schnyer, D.M. Support vector machine. In Machine Learning; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. Decision trees. In Machine Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Q.S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. A distributed occupancy distribution estimation method for smart buildings. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 15th International Conference on Control and Automation (ICCA), Edinburgh, UK, 16–19 July 2019; pp. 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Pantazaras, A.; Chaturvedi, K.A.; Chandran, A.K. Comparison of different occupancy counting methods for single system-single zone applications. Energy Build. 2018, 172, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, J.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, L. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, D.; Li, N.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, Y. GET: Group equivariant transformer for person detection of overhead fisheye images. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 24551–24565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, G.; Xu, S.; Ji, T. Real-time dynamic estimation of occupancy load and an air-conditioning predictive control method based on image information fusion. Build. Environ. 2020, 173, 106741. [Google Scholar]

- Mutis, I.; Ambekar, A.; Joshi, V. Real-time space occupancy sensing and human motion analysis using deep learning for indoor air quality control. Autom. Constr. 2020, 116, 103237. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Um, C.Y.; Kang, K.; Kim, H.; Kim, T. Application of vision-based occupancy counting method using deep learning and performance analysis. Energy Build. 2021, 252, 111389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Y.; Qin, W.; Abbas, A.; Li, S.; Ji, R.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Yang, J. Lightweight Network for Corn Leaf Disease Identification Based on Improved YOLO v8s. Agriculture 2024, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhuang, X.; Zhang, B. Automated marine oil spill detection algorithm based on single-image generative adversarial network and YOLO-v8 under small samples. Mar. Pollut. 2024, 203, 116475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Yu, C.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Y. YOLO-GP: A Multi-Scale Dangerous Behavior Detection Model Based on YOLOv8. Symmetry 2024, 16, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisantal, M. Augmentation for Small Object Detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.07296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Meng, G.; Xiang, S.; Sun, J.; Jia, J. Stitcher: Feedback-driven data provider for object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.12432. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, Y.; Isidoro, J.; Milanfar, P. RAISR: Rapid and accurate image super resolution. IEEE Trans. 2017, 3, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Wang, P.; Hoare, C.; O’Donnell, J. Building occupancy detection and localization using CCTV camera and deep learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xing, Z.; Wang, H.; Dong, X.; Gao, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y. Maize-YOLO: A new high-precision and real-time method for maize pest detection. Insects 2023, 14, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Chen, M.; Zhao, H.; Liao, J. A lightweight recognition method for rice growth period based on improved YOLOv5s. Sensors 2023, 23, 6738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q. Slim-neck by GSConv: A better design paradigm of detector architectures for autonomous vehicles. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.02424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, H.; Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Tang, X. Lightweight tomato ripeness detection algorithm based on the improved RT-DETR. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1415297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.R.; Huang, W. Tood: Task-aligned one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 3490–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.; Chen, S.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, J. Generalized focal loss: Learning qualified and distributed bounding boxes for dense object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 21002–21012. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Xia, S.; Cai, Y.; Yang, C.; Zeng, S. A soft-YoloV4 for high-performance head detection and counting. Mathematics 2021, 23, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Guo, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, K.; Luo, Z. Improved lightweight head detection based on GhostNet-SSD. Neural Process. Lett. 2024, 56, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Niu, M. Head detection based on dr feature extraction network and mixed dilated convolution module. Electronics 2021, 10, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Dou, Y. End-to-end spatial attention network with feature mimicking for head detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 15th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2020), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Peng, D.; Cai, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jin, L. Scale mapping and dynamic re-detecting in dense head detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Athens, Greece, 7–10 October 2018; pp. 1902–1906. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.