Featured Application

This study provides a validated framework that quantifies deliverable heat output, primary energy savings, CO2 emissions reduction, and economic payback for using data centre waste heat in fifth, fourth, and third generation DH systems. The framework assists municipal DH utilities, data centre operators, energy planners, and energy regulators in decision-making for waste heat use in urban heating networks. Results are applicable for sizing, setting tariffs, and planning practical implementation, especially for urban districts aiming to increase system-wide energy efficiency and minimize carbon emissions.

Abstract

Growing demand for computing resources is increasing electricity use and cooling needs in data centres (DCs). Simultaneously, it creates opportunities for decarbonisation through the integration of waste heat (WH) into district heating (DH) systems. Such integration reduces primary energy (PE) consumption and emissions, particularly in low-temperature DH networks. In this study, the possibility for utilisation of WH from DC hybrid cooling system into third generation (3G), fourth generation (4G), and fifth generation (5G) DH systems is investigated. The work is based on the dynamic simulations in TRNSYS. The model of the hybrid cooling system consists of a direct liquid cooling (DLC) loop (25–30 °C) and a chilled water rack coolers (CRCC) loop (10–15 °C). For 3G DH, a high-temperature water-to-water heat pump (HP) is applied to ensure the required water temperature in the system. Measured meteorological and equipment data are used to reproduce real DC operating conditions. Relative to the reference system, integrating WH into 5G DH reduces PE consumption and CO2 emissions by 88%. Results indicate that integrating WH into 5G DH and 4G DH minimises global cost and achieves a payback period of less than one year, whereas 3G DH, requiring high-temperature HPs, achieves 14 years. This approach to integrating waste heat from a hybrid DLC+CRCC DC cooling system is technically feasible, economically and environmentally viable for planning future urban integrations of waste heat into DH systems.

1. Introduction

Data centres (DCs) are rapidly becoming important factors in urban energy systems. Their electrical load is increasing, matched by a growing discharge of low-to-medium-grade heat from the cooling system to the environment. Converting that by-product into a useful resource for buildings and district heating (DH) networks presents a credible pathway to reduce primary energy (PE) use and CO2 emissions, while enhancing overall system efficiency.

DCs use different types of cooling systems. The basic classification of cooling systems includes computer room air conditioning (CRAC), computer room air handling (CRAH) systems, direct liquid-cooled (DLC), two-phase systems, and hybrid liquid/air systems [1]. Typical recoverable temperatures in air streams are 25–35 °C or 10–20 °C in chilled water loops for air-cooled systems, rising to 50–60 °C for DLC systems. In hybrid cooling systems, 30–40% of energy is dissipated on air at 25–35 °C, while the rest of the heat (60–70%) is transferred to liquid at 50–60 °C. Waste heat can be supplied directly to low-temperature DH or raised by heat pumps (HP) to higher-temperature DH [2]. Air-cooled reuse via return-air or DC chiller condenser loops typically yields sources up to 50 °C, necessitating HP lift to 70–90 °C [3]. Hot water-cooled DCs commonly provide 50–60 °C, enabling efficient DH integration [4]. Environmental benefits include reduced PE consumption and reduced CO2 emissions at the network scale when waste heat (WH) displaces boilers and combined heat and power units [5].

The economic feasibility of utilising WH from DCs in DH systems depends on the required investment in the heat recovery and integration infrastructure, and the price at which this heat is sold to the DH system. There are different price models for purchasing WH from DCs. In Finland, the emphasis is on a “transparent and, above all, predictable” price for WH. Pricing is based on marginal costs, meaning it is set below the cost of producing thermal energy from conventional sources and is therefore economically attractive for the DH operator to buy [5]. In Sweden, the DH utility purchases WH at a price indexed to the outdoor temperature [6]. The key element of the Danish model is the rule that surplus heat must be sold at a cost-based price without generating profit, unless significant CO2 emission reductions can be demonstrated, in which case partial profit is exempt from taxation [7]. In the UK, the utilisation of heat from data centres is further incentivised by the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme. The government support is paid per kWh of heat produced. Eligibility requires that the HP achieve a minimum COP of 2.9 [2].

At the EU level, there is still no unified cost model for purchasing WH from DCs. To improve energy efficiency and enhance the sustainability of the energy system, it has become legally mandatory to consider the integration of WH from DCs into DH networks. EU Directive 2023/1791 [8] imposes additional obligations on DCs with installed information technology (IT) power exceeding 500 kW. Beyond the existing requirements for monitoring and reporting power usage effectiveness (PUE), water usage effectiveness (WUE), and carbon usage effectiveness (CUE), the directive introduces new key performance indicators, including utilisation of renewable energy, energy reuse, cooling system efficiency, and IT equipment efficiency.

The review paper [1] increasingly frames DCs as “prosumers” within DH entities that both consume electricity and produce heat. Reviews of European and Nordic cases document that coupling DCs with DH can displace fossil boilers, provided temperature levels, temporal profiles, and network hydraulics are adequately matched. Integration waste-heat recovery (WHR) challenges include mismatches in location, temperature levels, regulatory constraints, and data confidentiality concerns.

Yuan et al. [9] present a comprehensive review of WHR applications in DCs, categorising strategies by WH grade and end-use (e.g., space heating, absorption chillers, electricity generation). They highlight that low-grade WH, common in air-cooled systems, necessitates temperature upgrading via HPs, whereas high-grade heat from liquid cooling is directly usable. Furthermore, they advocate for the integration of thermal energy storage (TES) systems and policy incentives to bridge the economic gap for widespread implementation.

The case study-based papers analysing the integration of WHR into DH are summarised in Table 1. The studies examine DH temperature, DC capacity, the recovery method, and the usable heat potential.

Table 1.

The case study-based papers with the integration of waste-heat recovery into district heating.

Air-cooled systems have been analysed in the studies [3,11,12,13]. Oró et al. [3] used TRNSYS simulations to evaluate energy and economic viability for several air-cooled DC configurations (CRAH + chiller, rear door cooling) in urban contexts. The DH regime is high-temperature 90/70 °C (3G DH) with a return/supply feed-in configuration. Their study underscores the pivotal role of Energy Reuse Factor (ERF) as a metric, reporting values up to 55% for condenser-based recovery via HP into DH. While they confirm technical feasibility, the economic analysis shows that integration becomes viable only under favourable conditions (e.g., high energy prices, supportive policy frameworks).

The study [11] aims to explore the techno-economic and environmental performance of utilising CO2 transcritical HPs for recovering WH from DCs with CRAH cooling system for DH applications. It compares four configurations to determine the optimal system design for maximising energy efficiency and economic viability. They consider DH regimes 75/30 °C (3G DH) and 50/20 °C (4G DH) with the optimisation of CO2 transcritical HPs for these temperature levels. Results indicate that recovering heat from the IT room cooling-water stream outperforms chiller-based recovery, increasing the maximum COP by 18.2–28.9% and lowering system investment by 4.2–10.2%. The cycle with the shortest dynamic payback is contingent on prevailing electricity and heat prices. WHR enhances overall DC efficiency; for an annual heating period of 121 days, the energy reuse effectiveness (ERE) can be reduced from 1.296 to 0.902.

Beyond single installations, optimisation studies try to determine the best way to integrate DC heat into low-temperature DH [12]. Yu et al. highlight the importance of dispatch strategies, temperature lift, and substation control, often finding that direct return-line injection is efficient where network return temperatures are low, whereas HP assistance is needed for higher supply set-points or when simultaneous cooling and heating demands are misaligned. Urban, air-cooled DCs also present recoverable heat. Modelling and demonstration work indicate that, even where server rooms are cooled by conventional CRAH and CRAC systems, condenser-side or exhaust-air heat can be captured and routed to buildings or DH, increasing network energy efficiency and enabling higher ERF.

Miškić et al. [13] investigated the techno-economic optimisation of WH integration from air-cooled DCs into low-temperature DH networks. Using pinch analysis and thermodynamic modelling, they developed hourly merit-order dispatch strategies for combining HEX and HP technologies. Their findings reveal that effective integration depends strongly on matching WH temperature profiles with DH supply regimes, and that hybrid configurations consisting of HEX with HP offer superior flexibility and economic performance under varying ambient and load conditions.

Water-cooled systems have been analysed in the studies [4,10,14].

Feike et al. [4] evaluated a real-world installation at TU Darmstadt, where hot-water cooling combined with HP enables heat injection into the DH return line. Their monitoring data shows high system efficiency and reduced reliance on compression cooling. However, they also highlight operational challenges such as variable heat loads and underutilisation during low-demand periods, stressing the need for flexible control algorithms.

Lu et al. [10] advance the discussion by modelling liquid-cooled DCs as “data furnaces” capable of directly building space heating without intermediate HPs. Comparing primary and secondary loop recovery schemes, they find that secondary-side heat recovery offers higher efficiency and more stable output. Both configurations achieve payback within one year and significant lifecycle CO2 reductions, underscoring the viability of decentralised heating solutions for office buildings and campuses.

Stock et al. [14] developed a simulation model to assess the integration of DC WH into an existing German DH network with supply temperature of 95–132 °C and return temperature of 65 °C corresponding to second-generation district heating (2G DH). The simulation considers integrating WH into a medium-temperature DH network with supply temperature of 80–100 °C and a return temperature of 60 °C. The WH source from the new high-performance computing cluster (HPC) is approximately 44 °C, consistent with DLC systems, although this is not explicitly specified. Their findings reveal that up to 40% of the system’s demand can be met through WH, but lowering supply temperatures introduces hydraulic and thermal constraints. The study underscores the need for careful system-level modelling to ensure reliability and optimal performance.

The paper [6] analyses the transition from an air-cooled DCs with rear-door water HEX to hot-water direct-to-chip cooling with an outlet temperature of around 45 °C on a case study of TU Darmstadt’s Lichtenberg II HPC DC. DH network operates on average 88/58 °C (supply/return), but return varies between 50 °C and 70 °C, hence a HP is required. Their analysis contrasts with two integration scenarios: one supplying heat directly to adjacent buildings, and another feeding into the return line of the university’s DH network via an HP. The study demonstrates that up to 50% of WH can be reused, yielding CO2 savings of up to 720 tonnes annually.

Davies et al. [2] take a system-level perspective, proposing the integration of London-based DCs into urban heat networks via HPs. A techno-economic analysis is conducted for several configurations: air cooling (CRAC/CRAH); hybrid liquid–air (60–70% liquid at 50–60 °C and 30–40% air at 25–35 °C); and fully DLC with WH at 50–60 °C. A delivery temperature of 70 °C for the recovered heat is proposed, achieved via heat pumps. Their modelled scenario suggests that coupling a 3.5 MW data centre with a DH system can save over 4000 tonnes of CO2 and nearly EUR 1.150 million annually. The paper also identifies temporal mismatches between peak DC heat availability and DH demand, advocating for buffer storage and smart control solutions.

The analysis of DC cooling systems in the studies [3,6,10,11,12,14] was carried out using the method of dynamic simulation. Studies [3,11,12] analysed air-based cooling systems; studies [4,10,14] examine water-based cooling systems, while study [6] investigates the transition from air to water cooling systems. Hybrid cooling systems consisting of air and water-cooling equipment were not considered in any study to date. A systematic analysis that represents the simultaneous operation of a hybrid cooling system within a single simulation model, under identical dynamic conditions for DCs employing air and liquid cooling, is absent. Moreover, few studies [4,6,10] address DCs with capacities under 1 MW, whereas no study examines a smaller DC with a capacity of approximately 0.1 MW.

In these studies, the measured hourly load of equipment is seldom used; instead, idealised or average profiles are commonly adopted, which introduces uncertainty into the results of the studies conducted. Among the studies that consider the use of HPs for WH recovery [2,3,4,6,9,10,11,12,13,14], only studies [3,4] examine the technical characteristics of commercial HP.

Taken together, these observations indicate the need for an integrated approach that combines real operational data, comprehensive dynamic analysis, and the relevant local regulatory and economic context.

The novelty of this study is threefold:

- Development and experimental validation of a comprehensive TRNSYS simulation model for a real-world hybrid cooling system in an HPC DC. The model integrates DLC and CRCC with dry coolers and water-cooled chillers within a unified framework, using measured IT load profiles and ambient temperature data.

- Quantitative comparison of WHR from DC into 5G and 4G networks, as well as 3G DH network using high-temperature water-to-water HPs, with explicit evaluation of impacts on delivered thermal energy, PUE, and ERF.

- Integration of technical performance results with a life-cycle cost analysis based on local energy tariffs, providing a robust techno-economic assessment.

Collectively, these contributions establish a consistent energy and techno-economic foundation for the practical integration of hybrid-cooled DCs into DH systems.

2. Materials and Methods

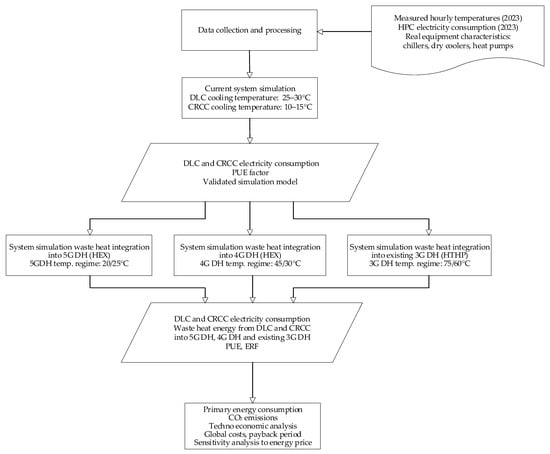

This study employs a comprehensive framework combining dynamic simulation, calculation of energy and environmental indicators, economic evaluation, and regulatory analysis to assess the integration of DC WH into DH networks. Dynamic simulations were carried out in TRNSYS 17 software, enabling hourly resolution modelling of the hybrid cooling configuration, which comprises DLC coupled with CRCC. The simulation of the HPC cooling system incorporates models of all the equipment required for real operation, including dry coolers, water-cooled chillers, plate HEXs, and a thermal storage tank to capture realistic operational dynamics. WH utilization is considered for three different generations of DH systems in use today. For 3G DH, a high-temperature water-to-water HP is implemented in the system due to the required temperature regime in the DH system, while direct recovery strategies are examined for low-temperature 4G DH and 5G DH systems. The primary flowchart of the modelling and simulation cycle is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the modelling and simulation cycle.

To quantify energy performance, PE consumption is calculated using PE factors for energy carriers, which are defined at the national level. In parallel, annual CO2 emissions are calculated from energy consumption acquired from simulation outputs. These metrics are complemented by DC-specific performance indicators, PUE calculated in accordance with the standard ISO/IEC 30134-2:2016 [15] and ERF calculated in accordance with the standard ISO/IEC 30134-6:2016 [16], which are widely applied in contemporary WH recovery research.

An economic assessment is conducted in accordance with EN 15459:2017 [17], applying life-cycle cost analysis to calculate global cost and payback periods for different integration strategies. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was performed on the results by analysing different electricity prices to provide insight into the financial feasibility of using high-temperature HPs versus direct recovery, accounting for electricity and heat energy market prices.

2.1. System Configuration

2.1.1. Existing Hybrid Cooling System

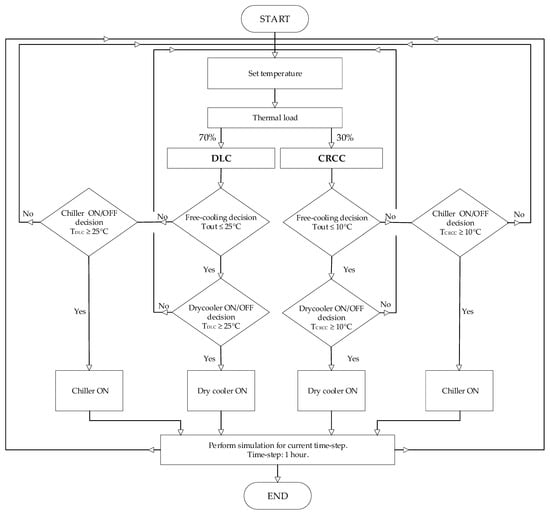

The HPC Bura located on the campus of the University of Rijeka, Croatia, was set in operation in 2016. The hybrid cooling system of HPC consists of a hot-water DLC subsystem for cooling computing nodes, and a chilled-water subsystem for cooling auxiliary components through water-cooled in-row units CRCC. Under full computational load, the electrical demand reaches 108.5 kW. This HPC cluster serves a wide spectrum of academic and industrial applications, with particular emphasis on life sciences and biotechnology. The control logic governing the operation of the DLC and CRCC systems is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Control logic diagram of the DLC and CRCC system operation.

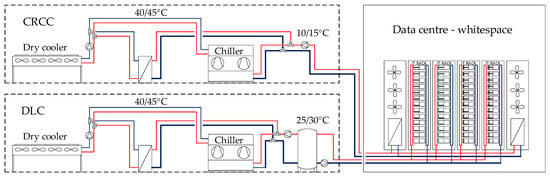

The hot-water DLC subsystem is the primary cooling arrangement. It is implemented through four DLC cabinets equipped with water-cooled processor units. Cooling is achieved by circulating coolant directly to the heat sinks of processors and other computing components, with water temperatures maintained between 25 °C and 30 °C. This subsystem provides high efficiency, removing approximately 70% of the heat generated by the IT equipment [4]. The residual heat is dissipated via a chilled-water loop operating between 10 °C and 15 °C, connected to two in-row CRCC units. These units, installed adjacent to the DLC racks, extract warm air from the hot aisle and transfer the heat as air passes over the server racks.

The DLC subsystem is supported by two water-cooled chillers (duty and standby units). Similarly, the CRCC subsystem operates with two water-cooled chillers. Both subsystems are equipped with free-cooling capability through integrated dry coolers, which discharge condenser heat to the ambient environment. The technical features of the existing cooling equipment DLC and CRCC subsystems, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The technical features of the DLC and CRCC subsystems cooling equipment.

In the DC cooling system, the temperature must be maintained at 25 °C for the DLC system and 10 °C for the CRCC system. When the dry-cooling system can no longer maintain required temperatures, chillers are turned on. The schematic representation of the hybrid cooling system is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The schematic representation of the hybrid cooling system in the DC.

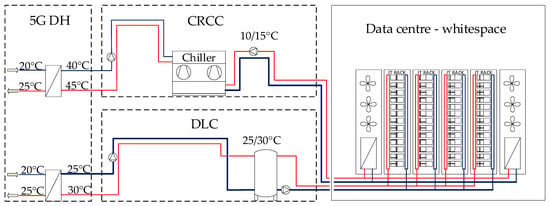

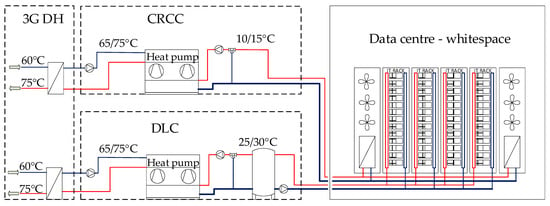

2.1.2. Integrating DC Waste Heat into 5G DH

The 5G DH system is defined as a thermal network in which water acts as the transfer medium, providing both a heat source and a heat sink for HPs located within substations [18]. This configuration corresponds to the well-established concept of a water loop heat pump (WLHP) system [19]. The characteristic of a 5G DH system is the use of water as the heat carrier at a temperature of approximately 20 °C. For the integration of WH into such a network, it is necessary to install a HEX and a connection pipeline in place of the dry coolers, as illustrated in Figure 4. In the DLC subsystem, the WH from HPC is directly rejected to the DH system via a HEX.

Figure 4.

The schematic representation of the integration of the hybrid cooling system with 5G DH.

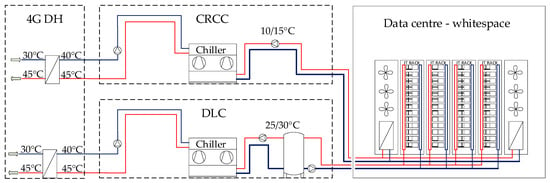

2.1.3. Integrating DC Waste Heat into 4G DH

Some of the fundamental features of the 4G DH system are the possibility of integration of WH and the reduction in distribution network temperatures compared with existing DH systems [20]. Typical supply/return temperature regimes range from very low temperature 65/30 °C to ultra-low temperature 45/30 °C [21].

The 4G DH with a temperature regime of 45/30 °C was considered, in which the existing chillers remain in operation with condenser water temperatures of 45/40 °C. The connection to the 4GDH system is arranged such that the DH return [4,6,12] at 30 °C enters the HEX, is heated to the specified setpoint, and is then fed into the supply line. This return/supply configuration does not affect the DH return temperature and enables efficient heat delivery to the DH network [3]. The schematic representation of the integration of the hybrid cooling system with 4G DH is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The schematic representation of the integration of the hybrid cooling system with 4G DH.

2.1.4. Integrating DC Waste Heat into 3G DH

The DH networks in the city of Rijeka belong to the 3G DH, with a tendency to converge towards 4G DH, particularly in terms of lowering the supply and return temperatures in the distribution network. The supply/return temperature regime of the “District heating system East” in Rijeka is 75/60 °C. Upon completion of the DH renewal, it will supply 22,000 MWh of thermal energy annually to its users. The total thermal capacity of the gas boilers and combined heat and power (CHP) units is 15 MW.

For the DH demand, hourly space heating and DHW loads were taken from the validated TRNSYS model of the Kozala DH system in Rijeka developed by Požgaj et al. [22], which represents a 3 MW DH plant. Because the “District heating system East” is in the same climate (Rijeka) and serves a predominantly 1970s building stock like Kozala, the Kozala hourly load profile was scaled to match the installed boiler and CHP capacity of the “District heating system East” (15 MW) and adopted as its hourly DH demand.

Due to the mode of domestic hot water (DHW) preparation in substations, the supply temperature of the considered DH system cannot be reduced below 65 °C. The maximum condenser temperature of the existing water chillers is 55 °C; therefore, WH cannot be utilized in the DH network without the use of additional HP. In place of the existing chillers for DC cooling, high-temperature water-to-water HPs must be installed for both the DLC and CRCC subsystems, enabling the recovered heat to be upgraded to the required temperature level. Two water-to-water HPs are required for the DLC subsystem and two for the CRCC cooling subsystem. According to the manufacturer’s data for the Climaveneta EW-HT-G05 unit, the maximum condenser leaving water temperature is 78 °C, based on operation with R513A refrigerant [23]. The technical specifications of the units are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The technical features of the water-to-water heat pumps.

WH integration of the hybrid cooling system with a 3G DH network is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The schematic representation of the integration of the hybrid cooling system with 3G DH.

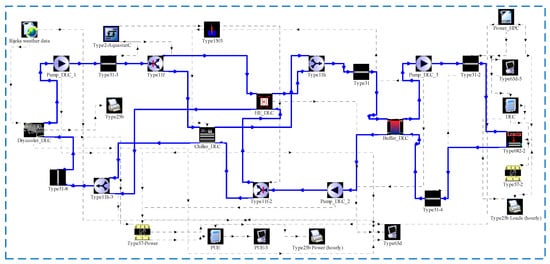

2.2. Simulation

The simulation model was developed in the TRNSYS environment, a modular transient system simulation software widely applied in energy system studies [24]. This enables simulation of the interaction between the DC cooling system and the DH network. Specific TRNSYS models, called Types, were used to represent the equipment in the system, hybrid cooling loops, HEXs, thermal storage, and HPs, allowing for a realistic representation of operational dynamics. The DLC cooling subsystem in the TRNSYS interface is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The DLC cooling subsystem in the TRNSYS environment.

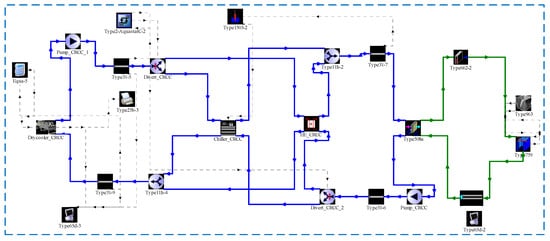

The thermal load from the HPC is introduced as the load to a flow stream using component Type 682 [25]. In the DLC subsystem, the cooling water is maintained at a temperature between 25 °C and 35 °C. For the simulation of the chiller with a water-cooled condenser, Type 666 [26] was used. The chiller characteristics are implemented through a performance map file with normalised values. Operation of the chillers is controlled by a temperature controller (Type 1503) [27]. To simulate free cooling, the dry fluid cooler model was used (Type 511) [26]. The dry cooler is controlled by a logic implemented using a series of equations. Free cooling is feasible when the outdoor temperature is lower than the required cooling temperatures of the DLC and CRCC subsystems. If the target temperature cannot be achieved, the chillers are activated. Switching between free cooling and chiller operation is managed by diverting valves (Type 11f) [28] controlled by a controller (Type 2) [28]. For modelling the HEX in TRNSYS, the Type 91 component was employed [28]. The water storage tank in the DLC subsystem is simulated using Type 534 [29], with a volume of 1 m3. Weather data for the city of Rijeka is implemented through Type 15 [30]. This study employed hourly ambient air temperatures for 2023 recorded at the University of Rijeka Campus, measured using the Davis Vantage Pro2 Wireless Weather Station. The CRCC cooling subsystem in the TRNSYS interface is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The CRCC cooling subsystem in the TRNSYS interface.

Air cooling is provided by CRCC in-row water–air units located within the DC. The recirculated room air is used for cooling purposes, with the chilled-water supply temperature for the in-row units maintained between 10 °C and 15 °C. To simulate the computer room, the simple lumped capacitance model (Type 759) [25] was applied. The thermal load within the space is introduced via a lumped mass (Type 963) [25]. For the simulation of the water-cooled chiller operation, the cooling coil (Type 508) [26] and fan (Type 662) [26] were employed in combination, representing the functioning of the in-row cooling units. The indoor air temperature is maintained at 24 °C. As with the DLC subsystem, the water-cooled chiller (Type 666) was used for simulating the chiller with a water-cooled condenser.

For the integration of WH into the 5G DH system, a HEX (Type 91) [28] is installed in place of the dry cooler. The inlet temperature on the load side of the HEX is 20 °C, while on the source side, the supply temperature for the DLC racks is 25 °C. The source-side outlet temperature after the HEX is monitored. The operation of the chiller (Type 666) [26] is controlled by a thermostat Type 1503 [27], with a set-point activation temperature of 25 °C. The operating range of the condenser in the existing chiller is between 20 °C and 60 °C. The DLC subsystem chiller, therefore, remains inactive. Since the supply temperature of the 5G DH network is lower than the required temperature for the DLC system, operation of the chiller is unnecessary.

For the integration of WH into the 4G DH system operation of both the DLC and CRCC chillers is required, since the DH supply temperature is higher than the cooling temperatures of the DLC and CRCC subsystems.

For the integration of WH into the 3G DH system, a high-temperature water-to-water HP (Type 1221) [26] was employed. The HP characteristics are implemented through a performance map file with normalised values. The operation of the HP is controlled by a thermostat controller (Type 1502) [27].

In the 3G DH configuration, the high-temperature water-to-water HPs operate in two seasonal modes: a winter space-heating regime with a 75/60 °C DH supply/return temperature and a summer regime dominated by DHW preparation with 65/50 °C DH supply/return temperatures. The Type 1221 model uses a manufacturer’s performance map in which the COP is expressed as a function of the instantaneous source and sink temperatures.

The thermal coupling between the DC cooling loops and the DH system is represented by counterflow HEX (Type 91), based on the ε–NTU formulation [28] with a constant effectiveness of 0.60 adopted for all analysed configurations.

The simulation model represents all main components of the hybrid cooling system and the DH interface with dedicated TRNSYS Types, as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. The IT heat load from the HPC Bura is introduced as a time-varying thermal load using Type 682, while the server room is represented by a lumped-capacitance zone (Type 759) with an internal lumped mass (Type 963) to capture the thermal inertia of the space and equipment. The water-cooled chillers are modelled by Type 666 using manufacturer-based performance maps, and the dry coolers are represented by Type 511. Plate heat exchangers between the DLC and CRCC loops and the DH networks are represented by Type 91, and the thermal storage tank in the DLC loop is modelled with Type 534. Weather boundary conditions are supplied by Type 15 using hourly ambient temperatures measured at the University of Rijeka Campus in 2023. For the 3G DH case, the high-temperature water-to-water HPs are modelled with Type 1221, again using performance maps derived from manufacturer data shown in Table 3.

The equipment characteristics implemented in these types are consistent with the technical data reported in Table 2 and Table 3, including cooling and heating capacities, compressor power, and temperature regimes for the Climaveneta NECS-W 302 chillers and the EW-HT-G05 0262 high-temperature HPs. The control of the hybrid cooling system and DH coupling follows the temperature regimes: in the DLC subsystem, the coolant is maintained between 25 °C and 30 °C, while the CRCC chilled-water supply is maintained between 10 °C and 15 °C; for the DH systems, the characteristic DH supply/return temperature levels are 25/20 °C for 5G DH, 45/30 °C for 4G DH, and 75/60 °C for 3G DH. These values define the setpoints and deadbands used in the control components. The chillers (Type 666) are controlled by thermostats Type 1503 or Type 1502, whereas the switching between free cooling (Type 511) and chiller cooling is realised via diverting valves Type 11f driven by a differential controller Type 2. In the 5G DH configuration, the DLC subsystem rejects heat directly to the DH return line through a heat exchanger (Type 91). In the 4G DH configuration, both DLC and CRCC chillers operate, while for the 3G DH case, the high-temperature HPs (Type 1221) are controlled to maintain the 65–75 °C condenser outlet required by the existing 3G DH network.

2.3. Input Data and HPC Model Validation

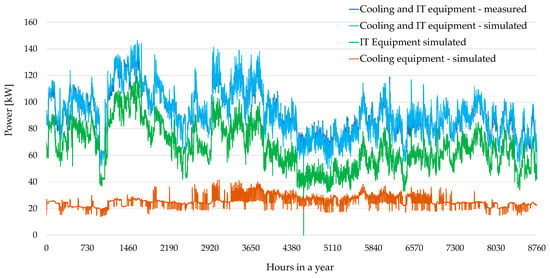

The input for the simulation of the existing cooling system, hourly values of electrical power measured at the HPC UPS during 2023, and ambient temperature readings are used. The measurements encompass the total electric power of the cooling plant and the IT equipment, shown in Figure 9. By simulating the existing system, the disaggregated power of the cooling equipment and the IT equipment is obtained. It is assumed that the electrical power required to operate the IT equipment is entirely converted into heat [2] and, in subsequent simulations, is treated as the thermal load. The total annual electricity consumption for the HPC Bura was obtained from meter readings at the metering point.

Figure 9.

Hourly load profiles.

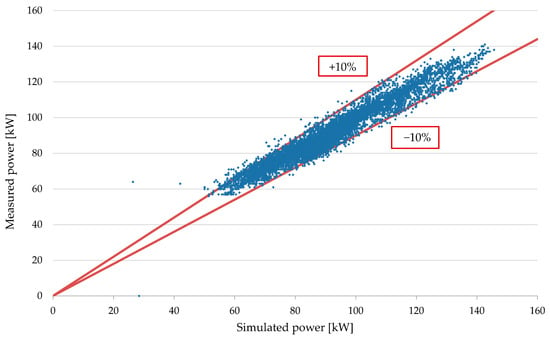

The comparison between the simulated and measured hourly power required by the cooling equipment and the IT equipment is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Deviation between the simulated and measured hourly power data.

The annual electricity consumption for supercomputer operation amounts to 579,408 kWh, for the cooling system 223,710 kWh, while other consumption totals 62,310 kWh. The overall annual electricity consumption is therefore 865,429 kWh. The electricity consumption of the current cooling system in the DC is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Electricity consumption of the current cooling system in the DC.

The TRNSYS model of the existing hybrid cooling system was validated against the measured operation of the HPC Bura in 2023. Figure 9 and Figure 10 compare the simulated and measured hourly powers of IT equipment and the cooling system, while Table 4 summarises the corresponding annual electricity consumption by end-use. The simulation reproduces the magnitude and variation in the measured cooling electricity demand and IT load with acceptable agreement. On this basis, the validated model is used as the reference configuration for the scenarios with integration into 5G DH, 4G DH, and 3G DH systems and for the subsequent energy, environmental, and economic analyses.

The adequacy of the model was further assessed by comparing the deviation between simulated and measured hourly values with results reported in previous validation studies. TRNSYS-based models of complex HVAC systems report maximum hourly relative errors in the range of 10–20% while still being judged sufficiently accurate for energy analysis [31]. Most simulated hourly values fall within ±10% of the measured values, with a normalized mean bias error (NMBE) of just 1%. In addition, the error metrics applied here are consistent with the calibration thresholds recommended by ASHRAE Guideline 14 [32] for hourly data (NMBE ≤ 10%, CV(RMSE) ≤ 30%), which are widely used as acceptance criteria for calibrated building energy models. Hence, the deviation obtained in this work is in line with the literature and is acceptable for the subsequent techno-economic assessment.

2.4. Instrumentation and Measurement Uncertainty

Hourly IT load of the DC was obtained from the integrated metering of a Schneider Electric Galaxy VM 200 kVA UPS, rated 200 kVA/180 kW at 400 V three-phase [33]. Ambient air temperature was measured with a Davis Vantage Pro2 wireless weather station [34] installed in the vicinity of the HPC Bura. The measurement range and standard uncertainty for each instrument are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Measurement range and standard uncertainty for instruments.

The term u(P)/P represents the relative standard uncertainty of the power measurement for a coverage factor k = 1, while u(T) denotes the standard uncertainty of the temperature measurement for k = 1.

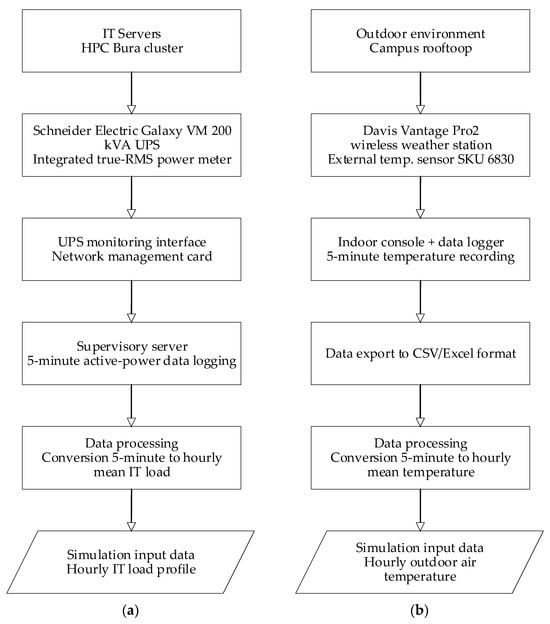

Figure 11 shows the instrumentation used to obtain experimental data on the hourly IT load of the DC and the ambient air temperature: the Schneider Electric Galaxy VM 200 kVA UPS, and the Davis Vantage Pro2 wireless weather station.

Figure 11.

(a) Schneider Electric Galaxy VM 200 kVA UPS, (b) Davis Vantage Pro2 wireless weather station.

The data-acquisition diagram for the hourly IT load of the data centre is shown in Figure 12a. The IT servers of the HPC Bura cluster are supplied through a Schneider Electric Galaxy VM 200 kVA UPS. The internal three-phase Root Mean Square (RMS) power meter of the UPS records the output active power at 5 min intervals. These data are transmitted via the UPS monitoring interface to the facility supervisory server, where they are aggregated to hourly mean IT load values and exported in spreadsheet format for subsequent analysis and model input.

The data-acquisition diagram for the outdoor air temperature is shown in Figure 12b. The temperature sensor SKU 6830 of the Davis Vantage Pro2 wireless weather station, Davis Instrument Corporation, Hayward, CA, USA is installed in a passive radiation shield at the rooftop level on the university campus. The sensor signal is transmitted wirelessly to the indoor console with an integrated data logger, which stores measurements at 5 min intervals. The recorded data are then exported in Comma-Separated Values (CSVs) or Excel format, processed to obtain hourly mean outdoor air temperature, and used as climatic input for simulations.

2.5. Main Modelling Assumptions

To ensure comparability across all considered configurations, several modelling assumptions are adopted. First, the hourly IT load of HPC Bura is represented by the measured UPS power for the year 2023, and it is assumed that the IT electricity demand is entirely converted into heat within the DC. The same hourly load profile is applied to the reference configuration and to the 5G, 4G, and 3G DH integration options. Second, the climate input is based on hourly outdoor air temperatures measured at the University of Rijeka Campus in 2023 and is used identically for all scenarios. Third, internal heat losses between the cooling equipment and the DC/DH interface are neglected owing to the short pipework and good insulation. Finally, the high-temperature water-to-water HPs are modelled using manufacturer performance data for the EW-HT-G05 0262 units, from which performance curves are derived over the operating temperature range. The COP is therefore not imposed as a fixed value but is calculated at each timestep as a function of source and sink temperatures.

Figure 12.

(a) IT load data acquisition, (b) ambient temperature data acquisition.

2.6. Calculation of the PUE and ERF Factors

Power usage effectiveness (PUE) [15] is calculated as the ratio of the total energy consumed, Etotal, to the energy consumption of the DCs IT equipment, EIT. For the existing cooling configuration of the HPC Bura, Etotal was obtained by measurement, whereas for the other cooling configurations with 5G DH, 4G DH, and 3G DH systems, it was obtained by simulation. PUE is calculated according to the following expression:

PUE = Etotal/EIT

Energy Reuse Factor (ERF) [16] denotes the proportion of energy that can be reused beyond the DC boundary relative to the total energy consumed within the DC, and is calculated as follows:

where Qreused is the useful WH from the DC delivered to the DH system. For the current cooling configuration of the DC, the WH is discharged to the environment via a dry cooler, and therefore, Qreused equals zero.

ERF = Qreused/Etotal

2.7. Energy Performance Calculation

The net imported final energy to the DC is defined as the difference between the DCs’ total energy consumption and the useful WH delivered to the DH system, and is calculated by the following:

Eimp = Etotal − Qreused

In all scenarios with DH coupling, the useful waste heat delivered to the DH system, Qreused is obtained on the DH side of the coupling component HEX. At each simulation time step (t), the instantaneous recovered heat is calculated as follows:

where mDH is the DH-side mass flow rate, cp = 4186 kJ/(kg, K) is the specific heat capacity of water, and TDH,out and TDH,in are the inlet and outlet temperatures on the DH side.

Qreused(t) = mDH(t)∙cp∙[TDH,out(t) − TDH,in(t)]

The PE consumption is determined by the following:

where the PE factor for electricity fPE,el is 1.614, nationally defined [35].

PE = Eimp∙fPE,el

2.8. Calculation of the CO2 Emissions

CO2 emissions are calculated as the product of the net imported final energy and the specific emission factor, using the following:

where Eimp is the imported electricity (kWh), and EFCO2 is the specific emission factor (kg CO2/kWh). For electricity, EFCO2 = 0.2348 kg/kWh, nationally defined [35].

mCO2 = Eimp∙EFCO2

2.9. Calculation of Costs

Total global costs comprise the initial investment in equipment together with annual operating and maintenance expenses. The present value of the global costs over the accounting period τ is calculated as the sum of discounted annual costs, considering the residual value at the end of the period:

where C0 is the initial investment, Cop(p) is the annual operation and maintenance (O&M) cost in year p, Vres is the residual value at the end of the period, and d(p) is the discount factor. The discount factor is defined as follows:

where i is the discount rate.

CG(τ) = C0 + SUM(Cop(p)∙d(p) − Vres∙d(τ))

d(p) = [1/(1 + i/100)] p

2.10. Regulatory Framework for WH Producers

The role of WH producers, entities that generate and supply surplus thermal energy to DH networks, is increasingly recognised as part of decarbonisation strategies within EU energy systems [8].

The Croatian legislative framework does not currently provide formal recognition for WH producers. The Heat Energy Market Act [36] and the Energy Act [37] define the roles of producers, distributors, and suppliers, but do not foresee the integration of heat from third-party sources. Moreover, the tariff methodology supervised by the Croatian Energy Regulatory Agency [38] does not include a dedicated model for determining the price of heat supplied from private sources.

Nordic countries provide some of the most advanced examples of regulating such entities, and their legislative frameworks may serve as models for upgrading Croatian regulation. In Denmark, the integration of surplus heat into local DH networks is permitted, with regulated pricing and technical conditions applying particularly to commercial sources such as DCs, supermarkets, and industry. A key feature of that model is the rule that surplus heat must be sold at cost-based prices without profit, except where significant CO2 emission reductions are demonstrated, in which case partial profit is tax-exempt in accordance with the Danish Energy Agency [7].

DC waste-heat prices vary by country. In Spain, in 2016, the DC operator’s selling price for WH was 10% lower than the DH tariff, at EUR 31.48/MWhth [3]. In Espoo (Finland), prices ranged from EUR 13.8/MWhth in July to EUR 40.4/MWhth in February [5,6]. In Stockholm (Sweden), the sale of surplus heat to the DH network is also available. In winter, the DC operator is paid up to ten times more than in summer, although the exact price is not specified [1]. In the UK, government incentives under the Renewable Heat Incentive are available to motivate interested DC operators to implement waste-heat recovery. In the economic analysis conducted in [2], an incentive price for WH of EUR 0.0287/kWh over 20 years is assumed. For a 3.5 MW DC, the authors estimate financial support of up to EUR 0.8 million per year.

Future national policies should explicitly address the technical, economic, and institutional mechanisms necessary to facilitate the integration of these sources into heating systems.

2.11. Operational Cost Components: Energy, Equipment, and Maintenance

Global costs and payback periods are evaluated over an accounting period of 20 years using the life-cycle cost method in EN 15459-1:2017, with a real discount rate of 3%.

The price of electricity for enterprise customers at medium voltage is set at EUR 0.174/kWh for the high tariff and EUR 0.105/kWh for the low tariff, as of 1 January 2025, according to the National distributor for enterprise customers [39] in Croatia.

According to the regulatory framework in Croatia, the cost of WH that can be supplied to the DH network is not defined by law. It is governed by a contract between the DC and DH operator. Under the economic model assumed in this analysis, the DC operator invests in the equipment required to utilise WH and sells the recovered heat to the DH operator.

In Croatia, the heat tariff comprises two components: a capacity charge for the contracted thermal power (EUR/kWth) and a variable heat charge (EUR/MWhth). The price at which the DC operator sells heat is based on the variable DH tariff. For the analysis, a price that is 10% below the variable DH tariff is assumed. The DH supplier [40] charges EUR 70.70/MWh for variable heat; accordingly, the DC operator’s selling price is EUR 63.63/MWh. Such an economic model between the DC operator and the DH system operator is considered in the paper [3].

To investigate the impact of changes in energy prices on total costs and payback period, a sensitivity analysis was conducted over simulation results. Electricity prices in European markets are generally subject to fluctuations and volatility owing to the generation mix (particularly variable renewables), demand patterns, and other factors such as fuel and CO2 prices, cross-border interconnector flows, and capacity availability. The sensitivity analysis was performed by varying the electricity price from −50% to +50% of the base price.

In the current configuration of the DC cooling system, no investment is required. For integration into 5G DH and 4G DH networks, investment is needed in HEXs, a heat meter, and a connection pipeline to the DH distribution system located in the immediate vicinity of the DC. For integration into the 3G DH network, investment is required in water-to-water HPs, HEXs, a heat meter, and a connection pipeline to the distribution system. Prices were obtained from equipment suppliers. The investment and maintenance costs are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Investment and maintenance costs.

Annual maintenance costs were considered for all the systems. Maintenance costs of the chillers and HPs are estimated at 4% of the value of the new equipment. In the 5G DH system, chillers for the DLC loop are not required; consequently, maintenance costs are lower than in the other systems.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Simulation Results

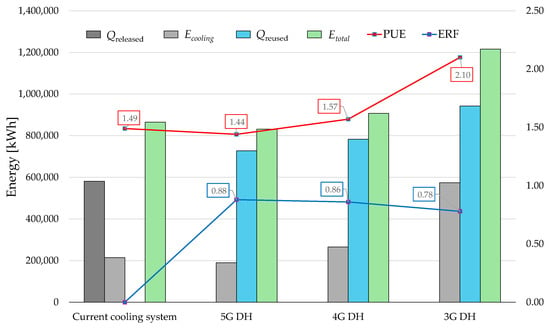

Through dynamic simulation of the hybrid cooling system of the DC, the energy released to the environment in the current system (Qreleased), the heat delivered to the considered DH networks (Qreused), the electricity for the cooling system (Ecooling), total electricity consumption (Etotal), as well as the PUE and ERF factors were obtained. The electricity consumption of the IT equipment (EIT) across all four systems totals 579,410 kWh. The results of the dynamic simulation are presented in Table 7 and Figure 13.

Table 7.

Obtained energy forms and the associated PUE and ERF values for the analysed systems.

Figure 13.

Obtained energy forms and the associated PUE and ERF values for the analysed systems.

In the current cooling system, WH is released to the environment via dry coolers, and therefore, Qreused equals zero. The total energy released into the environment amounts to 581,020 kWh annually. The total electricity (Etotal) consumption is 865,430, the PUE factor is 1.49, while the ERF factor equals zero.

In the 5G DH case with WHR, the PUE decreases to 1.44 compared with the reference system, because the DLC subsystem chiller is not required, and consequently, the total electricity consumption (Etotal) is lower at 831,530 kWh. However, when the DH temperature regime is raised to 30 °C in 4G DH, both chillers operate, increasing Etotal to 907,490 kWh and the PUE to 1.57. Installing a high-temperature HP to raise the temperature above 60 °C, which is the return-line temperature in 3G DH, further increases Etotal to 1,215,970 kWh and raises the PUE to 2.1.

Oro et al. [3] argue that PUE is not an adequate indicator when integrating heat-recovery systems, and it can be as high as 2.2. with 3G DH. Li et al. [11] report that the annual PUE can be reduced to 1.287 with waste-heat recovery and the utilisation of WH in the DH system, but they do not specify under which conditions.

Comparing the systems, the ERF is most favourable when integrating WH into 5G DH, where it is 0.88. With integration into 4G DH, it is 0.86, and into 3G DH, it is 0.78. In Oro et al. [3], where air-cooled systems are considered, the ERF is 55% for integration into 3G DH with heat taken from the chiller condenser. When heat-recovery solutions are integrated into the return air stream, ERF values lie between 25% and 45%. The authors assess ERF in terms of PE and denote it ERFPE, which is not aligned with the standard [16]. Some authors [5,11] calculate the Energy Reuse Effectiveness (ERE) factor, a combination of the PUE and ERF metrics. However, it is not standardised to the same level as PUE and ERF and is not used in this paper.

The measured hourly UPS power of the HPC Bura for 2023 was converted into available WH and coupled with this scaled DH demand profile, so that the temporal matching between DC heat output and DH demand is explicitly captured in the simulations. Owing to the large difference in capacity, the DH demand remains significantly higher than the available waste heat throughout the heating season. In the 3G DH configuration, the annual recovered heat of 942,910 kWh corresponds to roughly 4% of the annual DH heat supplied (about 22,000 MWh). In this case study, the DH system effectively acts as a heat sink that can always absorb the DC waste heat during network operation.

3.2. PE Consumption and CO2 Emissions

The reference system represents the existing hybrid cooling configuration of the HPC, in which water-cooled chillers and dry coolers reject all waste heat to the ambient environment, and no heat is supplied to the DH network. Primary energy consumption and CO2 emissions for the reference and all WHR variants are calculated in accordance with Equations (3), (5) and (6), using the nationally defined primary energy and emission factors for electricity in Croatia. All indicators are obtained from a full-year TRNSYS simulation with hourly resolution, driven by measured hourly IT power and ambient temperature data for 2023, so that the reported reductions reflect the complete annual operating profile of the DC.

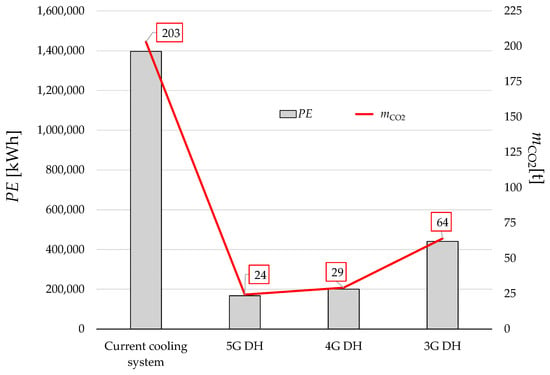

The PE consumption and CO2 emissions for the current hybrid cooling system, as well as for the integration of WH into 5G DH, 4G DH, and 3G DH, are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The PE consumption and CO2 emissions.

Integrating WH into the 5G DH system, the PE consumption is reduced by 88% compared with the current cooling system. Integration of WH into the 4G DH system reduces the PE by 86% compared with the current cooling system, while integration into the 3G DH system reduces the PE by 68% compared with the current system.

In the current cooling system, CO2 emissions amount to 203 tonnes per year. With the integration of WH into the 5G DH system, CO2 emissions are reduced to 24 tonnes per year. With integration into the 4G DH system, emissions amount to 29 tonnes per year, while integration into the 3G DH system results in 64 tonnes of CO2 emissions annually.

In the 3G DH variant, the higher primary energy consumption compared with 5G and 4G DH is mainly driven by the additional electricity required to operate the high-temperature HPs at lower seasonal COP, especially in the winter 75/60 °C regime when both temperature lift and DH load are highest. During the summer period, characterised by 65/50 °C DH supply/return temperatures, the HPs operate with slightly higher COP and therefore lower specific electricity use per unit of recovered heat.

From a physical perspective, the annual heat deliveries and ERF values reported in this section should be interpreted as an upper bound of the WHR potential of the modelled hybrid-cooled DC. They assume continuous availability of a suitable DH heat sink, negligible additional distribution losses, and ideal control of the hybrid cooling system. In real projects, the practically usable WH will be lower and will depend on the coincidence between IT load and DH demand, DH return temperatures, network constraints, outages, and maintenance.

These results are consistent with previous DC–DH case studies once differences in system boundaries are considered. Davies et al. [2] report that integrating a 3.5 MW DC into a London DH network can save over 4000 t of CO2, while Stock et al. [14] and Oltmanns et al. [6] show that HPC WH can supply up to 40–50% of the heat demand of German DH networks and campus buildings, with CO2 savings of up to 720 t/year. Oró et al. [3] obtain ERF values up to 0.55 for 3G DH in Barcelona, and Wahlroos et al. [5] quantify large-scale integration of 20–50 MW DC capacity into the Espoo DH system, with an annual heat potential of 487 GWh. In our case, the 62–88% reductions in PE consumption and CO2 emissions are calculated at the DC boundary, where the reference configuration rejects all heat to the ambient and the recovered heat displaces imported grid electricity via nationally defined primary energy and emission factors. The absolute contribution of the 0.1 MW HPC to the existing 3G DH system in Rijeka is about 4% of the annual heat demand, which is lower than the fractions reported for larger Nordic and German systems, but consistent with the smaller DC capacity considered here.

3.3. Cost Performance Results and Sensitivity Analysis

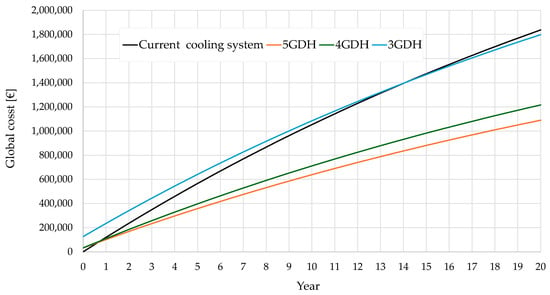

The global costs over the considered period for the considered system variants are presented in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

The global costs for the current cooling system and integration of WH into 5G DH, 4G DH, and 3G DH systems.

According to Figure 14, 5G DH achieves the lowest global costs. The payback period for 5G DH and 4G DH is less than one year, while 3G DH, owing to higher capital expenditure (CAPEX) and greater electricity use for the temperature lift, achieves a payback of 14 years. The ranking aligns with the energy results, since in 5G DH, the DLC chiller is not required, reducing exposure to electricity prices and operating costs. The figure therefore confirms that low-temperature integration 5G DH is the most cost-effective option, 4G DH is feasible but costlier, and 3G DH is the least economically robust.

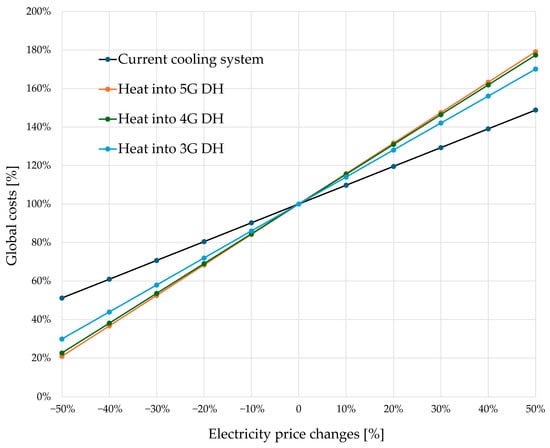

The impact of electricity price changes on global costs is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

The impact of electricity price changes on global costs.

Figure 16 shows the sensitivity of global costs to variations in the electricity price. Results are presented as relative values, normalised by the reference cost. For the current cooling system, a change in electricity price yields global costs from 51% to 149%. Over the same range, 3GDH spans from 30% to 170%, 4GDH from 23% to 177%, and 5GDH from 21% to 179%. In 3GDH, the heat pump operates with a higher temperature lift and thus higher electricity use, but the high CAPEX moderates the gradient relative to 4GDH and 5GDH systems. In 4GDH and 5GDH, electricity constitutes the dominant variable cost, producing the steepest curves.

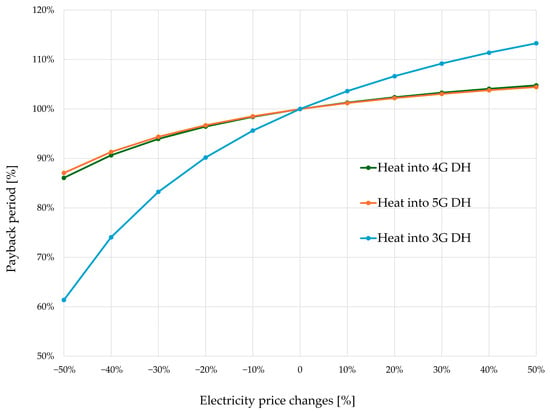

The impact of electricity price changes on payback period is shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

The impact of electricity price changes on the payback period.

Figure 17 illustrates how the payback period responds to electricity price variation. Payback lengthens monotonically as electricity prices rise, reflecting increased operating costs of compressor-driven components. The 5G DH system shows the lowest sensitivity to change in the electricity price, followed by the 4G DH system. In the 3G DH system, changes in the electricity price have a more pronounced effect on the payback period, which ranges from 61% to 113%.

The robustness of these findings is supported by the fact that the simulations are driven by measured hourly IT-load and climate data, while HP performance is derived from manufacturer data rather than prescribed constant COP values. Together with the sensitivity analysis of global costs and payback periods with respect to energy price variations, this reduces the influence of individual modelling assumptions: possible variations in IT load level, ambient temperature profile, network heat losses, or COP mainly shift the absolute values of energy use and economics, but do not change the relative advantage of 5G DH and 4G DH integration over 3G DH and the current configuration.

From an economic perspective, the short payback periods obtained for 4G DH and 5G DH fall within the most favourable range reported in the literature. Davies et al. [2] estimate that coupling a 3.5 MW London DC to DH can yield almost EUR 1.150 million/year of energy-cost savings, which becomes even more attractive when combined with Renewable Heat Incentive support of about EUR 0.8 million/year at an incentive price of EUR 0.0287/kWh. Lu et al. [10] report payback within one year for liquid-cooled “data furnace” concepts supplying decentralised building heating, while Oró et al. [3] emphasise that, for a 1 MW air-cooled DC in Barcelona, economic feasibility is achieved only under favourable combinations of electricity and heat prices. Li et al. [11] similarly show that the dynamic payback of CO2 transcritical HP schemes is highly sensitive to the tariff structure and DH temperature levels, and optimisation studies by Yu et al. [12] and Miškić et al. [13] indicate that configurations with higher temperature lift and larger HP capacity, analogous to our 3G DH variant, incur higher CAPEX and operating costs and are more exposed to electricity price variation. Against this background, the payback of less than one year for 4G DH and 5G DH obtained here lies at the favourable end of the reported range and is mainly driven by the low additional investment (HEX and connection pipeline) and the assumed heat price set 10% below the variable DH tariff, whereas the 14-year payback for 3G DH is consistent with the higher cost and risk associated with high-temperature HP-based integration highlighted in these previous studies.

Although the analysis focuses on a reference 0.1 MW IT DC, the annual energy, emission, and cost indicators normalised per unit of IT power enable meaningful comparison with both smaller and larger facilities using similar cooling technologies. Because the framework is driven by hourly IT load profiles and local meteorological data, it can also be transferred to other climates by replacing the input load and climate time series, together with the corresponding national tariffs and emission factors, without altering the structure of the model. However, the scalability of the concept to large-scale urban applications is constrained by the ability of DH networks to absorb the available WH throughout the year without exceeding permissible supply and return temperatures, by the capacity of the electricity grid to accommodate additional HP and pumping loads, and by the economic feasibility of connection pipelines.

3.4. Limitations and Future Directions

The reported annual heat deliveries and ERF values should be interpreted as an upper bound on the WHR potential of the modelled hybrid-cooled DC. They assume continuous availability of a suitable DH heat sink, negligible additional distribution losses, and ideal control of the cooling plant. In practical implementations, the usable WH will be lower and will depend on the coincidence between IT load and DH demand, actual DH return temperatures, network constraints, outages, and maintenance.

The analysis is based on a single 0.1 MW HPC installation in one climatic and regulatory context, and only vapour-compression HPs coupled to the DLC and CRCC loops are considered. Other options for upgrading low-temperature heat to DH supply levels, such as thermally driven absorption HPs and latent thermal storage using phase-change materials, have been successfully deployed at multi-megawatt scale in industrial and geothermal applications, but were not quantified here because they would require an additional high-temperature driving source and would considerably increase system complexity at the studied site [41,42].

Future work should therefore compare, within a common dynamic framework, electric and absorption HPs and hybrid configurations with thermal storage, and assess their impact on primary energy savings, CO2 reductions, and global costs.

In addition, the present model adopts a baseline HEX effectiveness at the DC–DH interface of ε = 0.6. Higher values (ε ≥ 0.8), achievable with larger or more advanced heat exchangers, would raise the recoverable WH temperature and could further improve ERF, primary energy savings, and CO2 reductions, at the cost of higher investment. Quantifying this trade-off and extending the analysis to larger data centres and DH systems with different temperature regimes will be an important step towards general design guidelines for integrating hybrid-cooled DCs as distributed heat sources in urban energy systems.

4. Conclusions

This study quantified the technical, energy, environmental, and economic aspects of integrating WH from a hybrid-cooled DC (DLC and CRCC) into 5G DH, 4G DH, and 3G DH systems using a validated TRNSYS model driven by measured hourly IT load and ambient temperature data for 2023.

Among the examined variants, low-temperature integration into 5G DH and 4G DH achieves the most favourable combination of DC indicators and system performance. In both cases, PUE remains below 1.6 and ERF above 0.85, whereas 3G DH requires a higher temperature lift and leads to a higher PUE of about 2.1 with ERF around 0.78. Compared with the existing hybrid cooling system without heat recovery, useful heat delivered from the DC to the DH network increases by approximately 25% (5G DH), 35% (4G DH), and 62% (3G DH). Over the full annual operating profile, primary energy consumption at the DC boundary is reduced by about 88% (5G DH), 86% (4G DH), and 68% (3G DH), with similar relative reductions in CO2 emissions.

The technical requirements differ by DH generation. For 5G DH and 4G DH, direct integration via HEX at low and medium temperatures suffices, enabling extensive use of free cooling and reduced chiller operation. For 3G DH under the considered Croatian conditions, high-temperature water-to-water HPs are needed to raise the temperature to the 75/60 °C winter regime and 65/50 °C summer DHW regime, which increases electricity use and reduces the net primary energy benefit.

The life-cycle cost analysis indicates that, under the assumed Croatian electricity tariffs and a heat-purchase price set 10% below the variable DH tariff, integration into 5G DH and 4G DH is highly attractive, with payback periods shorter than one year. The 3G DH configuration remains technically feasible but yields a payback of about 14 years owing to higher CAPEX and the additional electricity required for high-temperature HPs. An updated regulatory framework that recognises WH producers as specific entities and enables cost-based, transparent tariffs for purchasing DC heat would further support these investments and accelerate the integration of such sources into Croatian DH systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.P., B.D., B.P. and V.M.-V.; methodology, D.P. and B.D.; software and simulation, D.P., B.D. and V.M.-V.; formal analysis, D.P.; investigation, D.P.; resources, D.P. and B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P., B.D. and V.M.-V.; writing—review and editing, D.P., B.D. and V.M.-V.; visualisation, D.P., B.D. and V.M.-V.; supervision, B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the University of Rijeka under the project investigating the potential for the renewal of district heating systems using dynamic simulations (uniri-iskusni-tehnic-23-146). This work has been supported in part by the University of Rijeka under the project Increasing of heat exchange efficiency in green energy systems (uniri-mzi-25-33). This study employed hourly ambient air temperatures for 2023. recorded at the University of Rijeka Campus, measured by the Davis Vantage Pro2 Wireless Weather Station. Financing: Development of Research Infrastructure at the University of Rijeka Campus (RISK), co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (RC.2.2.06-0001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2G DH | 2nd Generation District Heating |

| 3G DH | 3rd Generation District Heating |

| 4G DH | 4th Generation District Heating |

| 5G DH | 5th Generation District Heating |

| A | Area (m2) |

| BHP | Booster Heat Pump |

| C | Cost (€) |

| CAPEX | Capital expenditure (€) |

| CSVs | Comma-Separated Values |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| COP | Coefficient of Performance (-) |

| CRAC | Computer Room Air Conditioning |

| CRAH | Computer Room Air Handling |

| CRCC | Chilled Water Rack Coolers |

| CV(RMSE) | Coefficient of Variation of the Root Mean Square Error |

| DC | Data Centre |

| DH | District Heating |

| DHW | Domestic Hot Water |

| DLC | Direct Liquid Cooling |

| E | Energy (kWh) |

| EF | Emission Factor |

| EP | Primary Energy (kWh) |

| ε | Effectiveness |

| ERE | Energy Reuse Effectiveness |

| ERF | Energy Reuse Factor |

| ERFPE | Energy Reuse Factor based on Primary Energy |

| f | Energy factor (-) |

| HEX | Heat Exchanger |

| HP | Heat Pump |

| HPC | High-Performance Computing |

| IT | Information Technology |

| k | Coverage Factor in the Evaluation of Uncertainty |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| m | Mass (t) |

| NMBE | Normalised Mean Bias Error |

| NTU | Number of Transfer Units |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance Costs (€) |

| PUE | Power Usage Effectiveness |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| SECAP | Sustainable Energy and Climate Energy Plan |

| TES | Thermal Energy Storage |

| u(P)/P | Relative Standard Uncertainty of Power Measurement |

| u(T) | Standard Uncertainty of Temperature Measurement |

| V | Value |

| WH | Waste heat |

| WHR | Waste heat recovery |

| WLHP | Water loop heat pump |

| Subscripts | |

| a | annual |

| cooling | cooling |

| d | discount |

| el | electricity |

| em | emission |

| exp | exported |

| heat | heat |

| i | discount rate |

| I | initial investment |

| imp | imported |

| op | operational and maintenance |

| p | year |

| prod | produced |

| released | released energy |

| res | residual |

| reused | reused energy |

| s | system |

| t | time step |

| total | total |

| Τ | accounting period |

References

- Huang, P.; Copertaro, B.; Zhang, X.; Shen, J.; Löfgren, I.; Rönnelid, M.; Fahlen, J.; Andersson, D.; Svanfeldt, M. A Review of Data Centers as Prosumers in District Energy Systems: Renewable Energy Integration and Waste Heat Reuse for District Heating. Appl. Energy 2020, 258, 114109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.F.; Maidment, G.G.; Tozer, R.M. Using Data Centres for Combined Heating and Cooling: An Investigation for London. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 94, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oró, E.; Taddeo, P.; Salom, J. Waste Heat Recovery from Urban Air-Cooled Data Centres to Increase Energy Efficiency of District Heating Networks. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feike, F.; Oltmanns, J.; Dammel, F.; Stephan, P. Evaluation of the Waste Heat Utilization from a Hot-Water-Cooled High Performance Computer via a Heat Pump. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlroos, M.; Pärssinen, M.; Manner, J.; Syri, S. Utilizing Data Center Waste Heat in District Heating—Impacts on Energy Efficiency and Prospects for Low-Temperature District Heating Networks. Energy 2017, 140, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltmanns, J.; Sauerwein, D.; Dammel, F.; Stephan, P.; Kuhn, C. Potential for Waste Heat Utilization of Hot-Water-Cooled Data Centers: A Case Study. Energy Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 1793–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdom of Denmark, Ministry of Climate, E. & Utilities. Danish Energy Agency. Available online: https://ens.dk/en (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- European Parliament. Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on Energy Efficiency and Amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (Recast) (Text with EEA Relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L231, 1–111. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.; Liang, Y.; Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Kosonen, R. Waste Heat Recoveries in Data Centers: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 188, 113777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Lü, X.; Välisuo, P.; Zhang, Q.; Clements-Croome, D. Innovative Approaches for Deep Decarbonization of Data Centers and Building Space Heating Networks: Modeling and Comparison of Novel Waste Heat Recovery Systems for Liquid Cooling Systems. Appl. Energy 2024, 357, 122473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Hu, S.; Duan, Y.; Yan, J. Optimal Schemes and Benefits of Recovering Waste Heat from Data Center for District Heating by CO2 Transcritical Heat Pumps. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 245, 114591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yan, Y. A Simulation Study on Heat Recovery of Data Center: A Case Study in Harbin, China. Renew. Energy 2019, 130, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miškić, J.; Dorotić, H.; Pukšec, T.; Soldo, V.; Duić, N. Optimization of Data Centre Waste Heat Integration into the Low-Temperature District Heating Networks. Optim. Eng. 2024, 25, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.; Arjuna, F.; Xhonneux, A.; Müller, D. Modelling of Waste Heat Integration into an Existing District Heating Network Operating at Different Supply Temperatures. Smart Energy 2023, 10, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 30134-2:2016; Information Technology Data Centres Key Performance Indicators Part 2: Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63451.html (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- ISO/IEC 30134-6:2021; Information Technology Data Centres Key Performance Indicators Part 6: Energy Reuse Factor (ERF). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/71717.html (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Energy Performance of Buildings—Economic Evaluation Procedure for Energy Systems in Buildings—Part 1: Calculation Procedures, Module M1-14 (EN 15459-1:2017). Available online: https://repozitorij.hzn.hr/norm/HRN+EN+15459-1%3A2017 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Buffa, S.; Cozzini, M.; D’Antoni, M.; Baratieri, M.; Fedrizzi, R. 5th Generation District Heating and Cooling Systems: A Review of Existing Cases in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE (American Society of Heating Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers). ASHRAE Handbook: HVAC Systems and Equipment, SI ed.; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781936504268. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, H.; Werner, S.; Wiltshire, R.; Svendsen, S.; Thorsen, J.E.; Hvelplund, F.; Mathiesen, B.V. 4th Generation District Heating (4GDH). Integrating Smart Thermal Grids into Future Sustainable Energy Systems. Energy 2014, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Hangartner, D.; Lindahl, M.; Pedersen, S.V. IEA Annex 47, Heat Pumps in District Heating and Cooling Systems; Heat Pump Centre: Borås, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Požgaj, D.; Pavković, B.; Delač, B.; Glažar, V. Retrofitting of the District Heating System Based on the Application of Heat Pumps Operating with Natural Refrigerants. Energies 2023, 16, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsubishi Electric. Mitsubishi Electric EW-HT-G05. Available online: https://climatizzazione.mitsubishielectric.it/it/news/prodotti/mitsubishi-electric-ew-ht-g05-e-ew-ht-c-g05-le-unita-ad-alta-temperatura-e-basso-gwp (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Trnsys. Transient System Simulation Tool. Available online: https://www.trnsys.com (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- TESS—Thermal Energy Systems Specialists, LLC. TESSLibs 17: Loads and Structures Library—Mathematical Reference; Thermal Energy System Specialists, LLC (TESS): Madison, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- TESS—Thermal Energy Systems Specialists, LLC. TESSLibs 17: HVAC Library- Mathematical Reference; Thermal Energy System Specialists, LLC (TESS): Madison, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- TESS—Thermal Energy Systems Specialists, LLC. TESSLibs 17: Controls Component Library—Mathematical Reference; Thermal Energy System Specialists, LLC (TESS): Madison, WI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Solar Energy Laboratory, University of Wisconsin-Madison. TRNSYS 17: A TRaNsient SYstem Simulation Program, Volume 4: Mathematical Reference; Thermal Energy System Specialists, LLC (TESS): Madison, WI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, J.W.; Bradley, D.E.; McDowell, T.P.; Blair, N.J.; Duffy, M.J.; LaHam, N.D.; Naik, A.V. TESSLibs 17 Volume 11 Storage Tank Library Mathematical Reference. TRNSYS 17 Doc. 2014, 11, 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- TESS—Thermal Energy Systems Specialists, LCC. TRNSYS 17 Weather Data (TRNSYS Documentation, Volume 8); Thermal Energy System Specialists, LLC (TESS): Madison, WI, USA, 2013; pp. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bogatu, D.I.; Carutasiu, M.B.; Ionescu, C.; Necula, H. Validation of a TRNSYS Model for a Complex HVAC System Installed in a Low-Energy Building. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. C Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2019, 81, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Guideline 14-2014: Measurement of Energy, Demand, and Water Savings; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, Georgia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Electric. Galaxy VM—Three-Phase Power Protection. Available online: https://www.totalpowersolutions.ie/wp-content/uploads/Brochure-Galaxy-VM.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Davis Vantage Pro2 Wireless Weather Station. Available online: https://manuals.plus/asin/B001AMRCDU (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Dović, D.; Duić, N.; Pukšec, T.; Dorotić, H.; Matak, N.; Horvat, I. Primary Energy and CO2 Emission Factors in Croatia. Available online: https://mpgi.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/EnergetskaUcinkovitost/meteoroloski_podaci/ELABORAT_Faktori%20primarne%20energije_final_objava%202022_04_01.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Republika Hrvatska. Zakon o Tržištu Toplinske Energije. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2013_06_80_1655.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Republika Hrvatska. Zakon o Energiji. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2012_10_120_2583.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Republic of Croatia. HERA. Available online: https://www.hera.hr/en/html/index.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- HEP Elektra d.d. National Electricity Operator HEP Elektra d.d., Tariff Items for Supply the Enterprise Customers. Available online: https://www.hep.hr/elektra/poduzetnistvo/tarifne-stavke-cijene-1578/1578 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Heat Energy Distributor Energo. Available online: https://energo.hr/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/CTS-–-Gornja-Vezica-–-Uredba-o-otklanjanju-poremecaja-na-domacem-trzistu-energije-subvencionirana-cijena-toplinske-energije_od-01.10.2024.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Interreg Central Europe Programme; ENTRAIN Project. Waste Heat and Heat Pumps for District Heating; Annex to D.T2.2. Planning Guidelines for Small District Heating; Version 1, April 2021. Available online: https://programme2014-20.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/ENTRAIN/Annex-Waste-Heat-and-Heat-Pumps-for-DH-2.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Thomson, A.; Claudio, G. The Technical and Economic Feasibility of Utilising Phase Change Materials for Thermal Storage in District Heating Networks. Energy Procedia 2019, 159, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.