1. Introduction

Autonomous transportation technologies are redefining the interaction between goods, materials, and infrastructure in industrial and urban environments [

1,

2]. Although much of the early focus in autonomy has centered on large-scale road vehicles, recent developments have highlighted the growing importance of compact, task-specific mobile systems operating in semi-structured domains. In parallel, the rise of micromobility and small-scale autonomous platforms has been recognized as a key enabler of sustainable transportation, reducing energy consumption, emissions, and spatial footprint while improving the flexibility of urban logistics and last-mile delivery [

3]. Beyond single-robot navigation, city-logistics deployment increasingly requires fleet-level coordination and routing integrated with motion planning under real-world uncertainty [

4]. Among these, heavy-duty skid-steer robots have emerged as robust solutions for logistics tasks that demand compact dimensions with high load capacity, and resilience against uneven terrain or environmental variability.

Intralogistics and infrastructure maintenance represent two domains in which such platforms provide immediate benefits. Intralogistics involves the autonomous handling and transportation of materials within factories, ports, and construction sites, where precise motion and repeated task execution are required in semi-constrained environments. Similarly, infrastructure-oriented robots are being increasingly deployed for inspection, surveying, and material handling in outdoor areas that lack structured navigation features. When designed for short-distance, energy-efficient operations, such compact robots contribute to sustainable mobility ecosystems by complementing larger autonomous vehicles and reducing the environmental impact of frequent low-payload transport tasks. In both domains, compact heavy-duty robots offer the advantage of maneuverability within confined areas while providing sufficient strength to transport or manipulate substantial payloads. However, achieving such performance introduces challenges related to kinematic feasibility and control smoothness [

5].

Heavy-duty skid-steer platforms are typically designed with an emphasis on stability, traction, and mechanical robustness rather than agility. Their limited steering capability and non-negligible turning radius make it impossible to perform in-place rotations or instantaneous heading changes. As a consequence, feasible trajectories are curvature-bounded, and controllers that neglect these constraints may issue infeasible commands or induce wheel slip. Classical differential-drive controllers, which assume free rotational capability, often fail to ensure curvature continuity and can produce discontinuous or unstable motion profiles on such platforms. A reliable motion control framework for these robots must therefore explicitly consider the geometric and physical limits imposed by the platform design.

The increasing deployment of skid-steer mobile platforms across industrial, agricultural, and inspection domains has intensified research on motion planning and control strategies tailored to the unique properties of this locomotion paradigm. Skid-steer mobile robots (SSMRs) exhibit fundamentally different turning characteristics than differential-drive or Ackermann-steered systems, as steering is achieved exclusively through differential wheel speeds. This mode of locomotion inherently induces wheel slip, lateral skidding, and strong terrain-dependent interactions. As vehicle mass and payload capacity increase, the resulting shear forces impose strict practical limits on the feasible turning radius; exceeding these limits can lead to structural stress, tire degradation, or unstable motion. Consequently, explicit curvature constraints become essential in the motion control of heavy-duty SSMRs.

A variety of modelling and control approaches have been proposed to address these issues. A learning-based modelling framework was introduced in [

6], capturing both slip dynamics and energy consumption for improved motion planning accuracy. Classical modelling work such as [

7] establishes detailed kinematic and dynamic formulations for four-wheel skid-steer platforms, highlighting stability limitations and the non-holonomic structure induced by differential speed control. More recent developments include a curved-path-following controller based on backstepping that accounts for both kinematic and steering dynamics [

8]. These contributions demonstrate that SSMRs cannot assume zero turning radius or arbitrarily large yaw rates, reinforcing the need for controllers that explicitly respect curvature or turning-radius bounds.

Trajectory planning methods for mobile robots often overlook the physical turning-radius constraint, despite its critical importance for vehicles that cannot rotate in place without inducing substantial lateral slip. Classical Dubins curves provide a minimum-turning-radius model but remain restricted to simple geometric primitives and do not address smooth, continuous trajectories or closed-loop tracking [

9]. More recent research explicitly integrates curvature feasibility. A curvature-constrained vector-field formulation for non-holonomic robots was proposed in [

10], ensuring bounded-curvature trajectories and guaranteeing convergence under actuation limits. Similarly, a Hamilton–Jacobi PDE-based formulation for optimal motion generation of curvature-bounded vehicles has been developed in [

11]. A recent survey of sampling-based motion planners [

12] further reveals that many widely used planners inadequately address curvature and non-holonomic constraints, thereby motivating the integration of curvature bounds into both global path planning and local control layers.

In addition to geometric feasibility, real-world trajectory execution requires speed profiles consistent with curvature and dynamic constraints. This is especially relevant for heavy-duty platforms, where abrupt changes in speed or curvature may lead to excessive drivetrain loading, wheel slip, or payload oscillation. The S-curve trajectory planning method presented in [

13] incorporates curvature radius and centripetal acceleration constraints, illustrating the strong coupling between curvature and velocity. The FDSPC framework [

14] further extends this line of work by generating G

2-continuous trajectories with integrated speed planning for bounded-curvature vehicles. For continuous-curvature path design, clothoid-based smoothing is a well-established approach for differential-drive robots under kinematic constraints, providing curvature continuity while remaining computationally tractable [

15]. These contributions underline the need for motion controllers that jointly regulate heading, curvature, and velocity while maintaining simple deployment for field deployment.

Although the literature offers extensive insights into skid-steer modelling, curvature-constrained planning, and smooth trajectory generation, several gaps remain for compact heavy-duty SSMRs operating in semi-structured outdoor logistics environments. Much of the existing research relies on idealized vehicle models such as Dubins cars or planar unicycles, which do not accurately represent the traction conditions, slip behavior, or turning limitations of high-mass skid-steer platforms. Furthermore, several curvature-aware planning approaches impose computational complexity.

At the same time, advances in localization and software infrastructure have made the deployment of these robots increasingly accessible. Global Navigation Satellite Systems with Real-Time Kinematic (GNSS-RTK) enable centimeter-level localization in open environments, while inertial measurement units (IMUs) provide complementary short-term motion estimates. The Robot Operating System 2 (ROS 2) offers a deterministic, modular middleware for integrating sensing, planning, and control components. Browser-based tools such as Foxglove Studio [

16] extend this ecosystem by providing intuitive mission supervision and trajectory editing capabilities, facilitating operator oversight even in remote or distributed setups.

This paper presents a generalized curvature-constrained trajectory execution framework tailored for compact heavy-duty skid-steer robots. The proposed approach introduces an explicit curvature-bounded control law integrated into a discrete event-driven state machine that governs waypoint alignment, progression, and mission-driven stopping behaviors. The architecture combines curvature-aware control with modular localization, trajectory management, and supervision components within the ROS 2 framework. In addition, it integrates a browser-based operator interface developed in Foxglove Studio, allowing users to define waypoints, assign speeds, and monitor mission execution in real time. The system has been validated in field conditions, demonstrating centimeter-level accuracy and stable curvature compliance in diverse operating scenarios.

The present work addresses these gaps by introducing a curvature-constrained trajectory execution framework tailored specifically to compact heavy-duty skid-steer robots. The proposed system embeds curvature bounds directly into the control law, employs a finite-state machine for robust mission execution, and integrates seamlessly with GNSS–RTK–IMU localization and ROS 2-based supervision. The method prioritizes geometric feasibility, computational simplicity, and practical deployability, and its effectiveness is demonstrated through field experiments.

This article extends our earlier conference paper [

17]. While [

17] focused on a specific application scenario and platform-level implementation, the present work provides a generalized and hardware-independent formulation of curvature-constrained trajectory execution. In addition, the current manuscript introduces (i) an explicit curvature-bounded control formulation with geometric interpretation of the minimum turning radius, (ii) a systematic comparison against baseline controllers without curvature constraints, and (iii) an expanded field evaluation using rosbag-based analysis across multiple trajectory patterns and waypoint densities. These additions significantly extend the scope, analysis depth, and reproducibility beyond the conference version.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the architecture, sensing, and control framework developed for curvature-constrained trajectory execution on compact heavy-duty skid-steer robots. The system integrates real-time localization, modular communication under ROS 2, a curvature-aware motion controller, and a web-based human–machine interface for mission supervision. Unlike clothoid-based smoothing methods that explicitly construct paths, the present work focuses on online curvature feasibility during execution via curvature saturation, combined with optional waypoint resampling for spacing control. The overall design prioritizes geometric feasibility, real-time responsiveness, and operator interpretability over algorithmic complexity.

2.1. System Architecture

The robot platform was designed to balance structural robustness with modularity and serviceability.

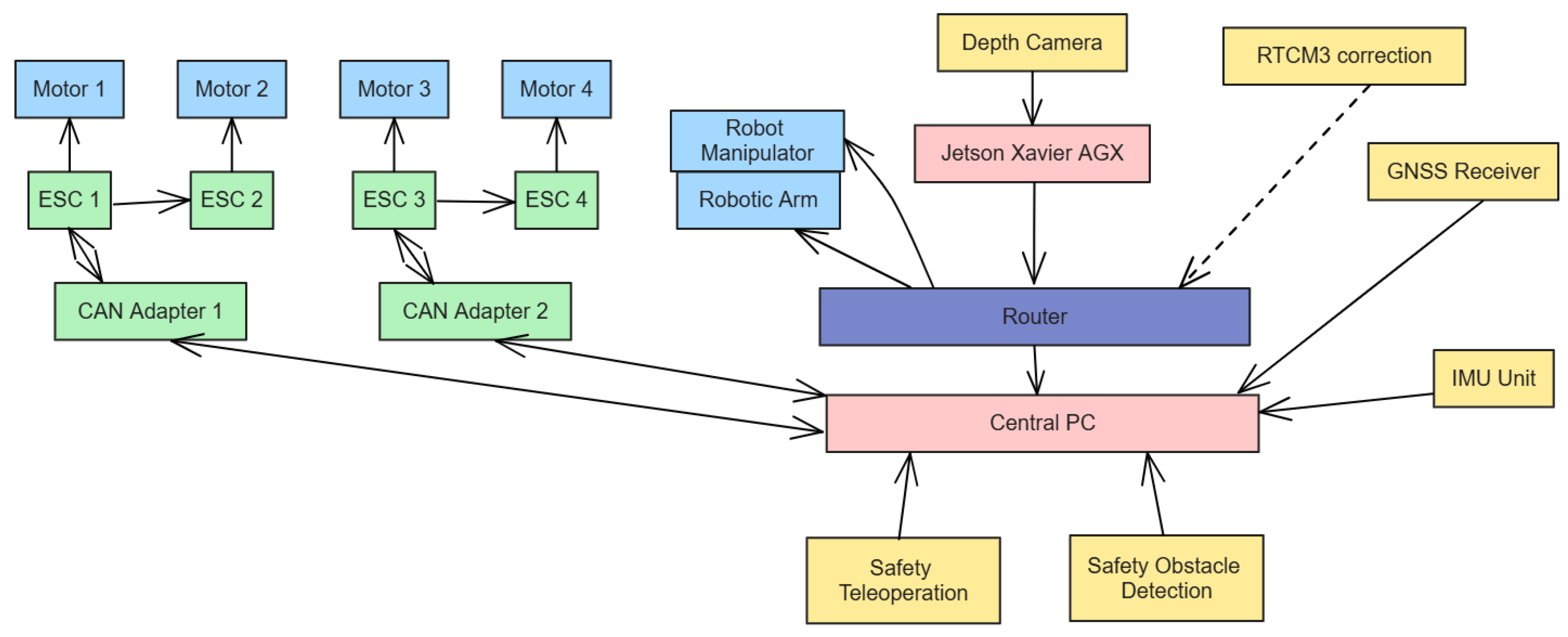

Figure 1 illustrates the main hardware and software components. Each of the four brushless drive motors is controlled by an electronic speed controller (ESC) interfaced via Controller Area Network (CAN) bus. Two independent CAN segments are managed by a central industrial PC to ensure fault isolation and deterministic communication. The compute unit hosts ROS 2 nodes for localization, control and supervision, while a secondary embedded GPU computer may be used for perception or data entry tasks. Both systems communicate over a high-bandwidth local network using a router that also provides remote access through a secure virtual private network.

Inertial data are provided by a six-axis IMU directly connected to the industrial PC through a serial interface. The global position is obtained from a GNSS-RTK (Drotek DP0601) receiver capable of centimeter-level accuracy under open-sky conditions. Real-time corrections are received through the Networked Transport of RTCM via Internet Protocol (NTRIP). The localization used by the controller does not rely on a tightly coupled GNSS–IMU fusion filter. Instead, global position is obtained directly from the GNSS receiver, while orientation (yaw) is provided by the onboard IMU. These signals are combined via a ROS 2 transform (/tf) to provide the robot pose used by the controller. No additional state estimation or filtering beyond sensor-level processing is applied. This design choice prioritizes transparency and allows the controller behavior to be evaluated independently of a specific fusion algorithm.

The control loop runs at 10 Hz under ROS 2 using a single-threaded executor, ensuring deterministic state-machine transitions and bounded latency.

2.2. Human–Machine Interface

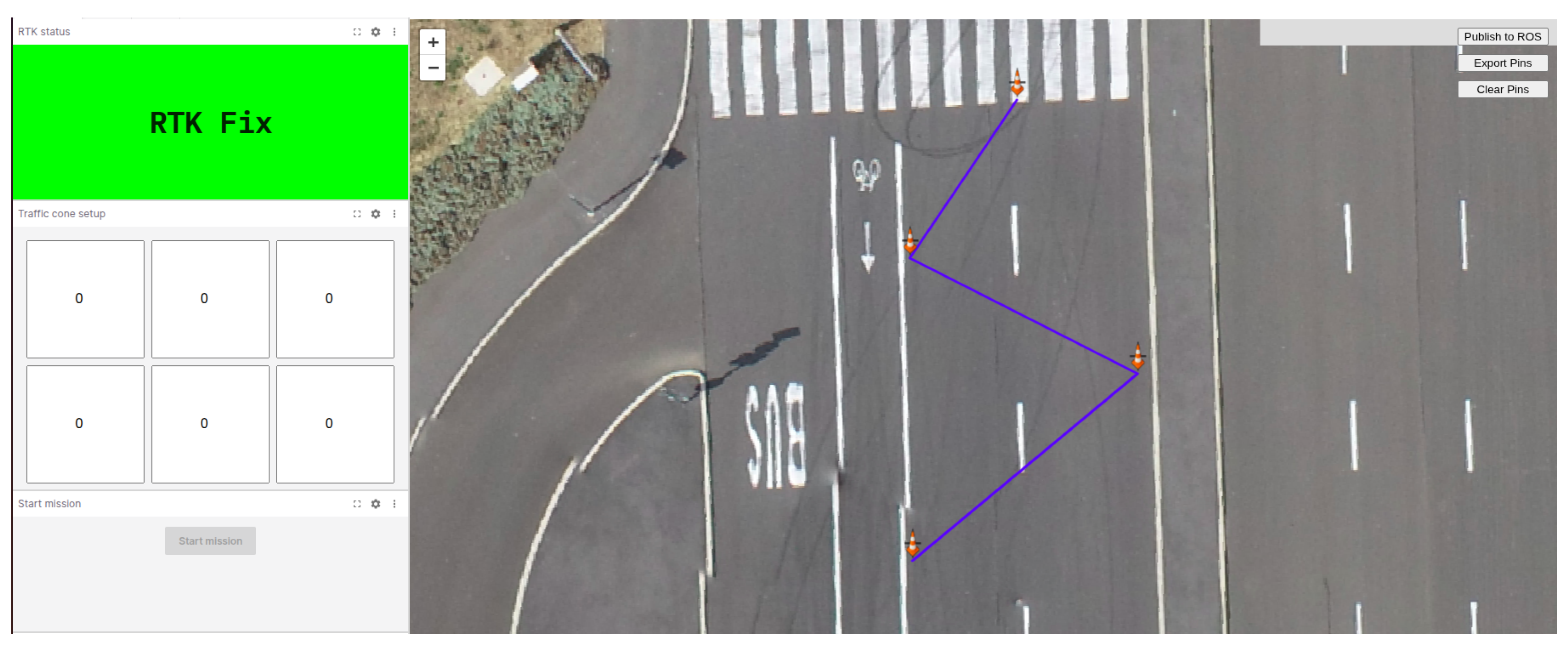

A custom supervision interface was developed using Foxglove Studio, a web-based visualization and mission control tool compatible with ROS 2. The interface allows the operator to author, edit, and monitor trajectories directly on a map view, as shown in

Figure 2. The panel was implemented as a Foxglove extension written in React and TypeScript and communicates with the robot through a WebSocket bridge. It provides access to the robot’s real-time state, published topics, and available ROS services.

Waypoints are represented as a geometry_msgs/msg/PoseArray message, while associated speed values are transmitted in a corresponding std_msgs/msg/Float32MultiArray. Operator commands, including start, stop, or reset actions, are implemented via standard std_srvs/srv/Trigger services. The graphical interface allows trajectory definition through direct map interaction: each click adds a waypoint, which can be repositioned or removed dynamically. Speed values can be adjusted per waypoint to encode velocity profiles or task semantics such as temporary stops. Once the configuration is finalized, the panel publishes the updated waypoint array and speed sequence to the controller node.

This design choice ensures platform-independent deployment: the panel does not require a local ROS installation, which simplifies multi-user access and supports remote operation. The use of Foxglove’s native React environment enables responsive visualization and low-latency updates synchronized with ROS 2 communication.

2.3. Trajectory Definition, Resampling, and Execution

The system follows a waypoint-based trajectory definition strategy. A trajectory is represented as an ordered set of waypoints in global coordinates, accompanied by a corresponding speed profile . Each waypoint defines a desired position and orientation, while its assigned speed value determines the target linear velocity in the vicinity of that waypoint. Speed values may vary continuously or include explicit zeros, indicating mission-driven stops for task execution or safety checks.

In addition to the operator-defined waypoint list, the framework optionally performs waypoint resampling (densification) to obtain a desired spatial spacing

s between consecutive points (e.g.,

m in the evaluation). For each consecutive pair of waypoints

and

, we compute the segment length

and insert

intermediate points by linear interpolation

The corresponding speeds are interpolated linearly between and . This resampling step improves geometric fidelity for sparse waypoint sets, while kinematic feasibility is guaranteed online by the curvature saturation in the controller.

The resulting waypoint sequence is published as discrete targets for the controller, which sequentially processes them in real time.

2.4. Kinematic Model and Curvature Constraints

The robot’s motion is modeled by a standard nonholonomic unicycle formulation [

18,

19]:

where

denotes the robot’s pose,

v the linear velocity, and

the angular velocity. The instantaneous curvature

is defined as the ratio of angular to linear velocity and is bounded by the platform’s physical constraints:

The controller explicitly enforces this bound at every update cycle, ensuring that the robot’s commanded motion never exceeds its geometric turning limits. This approach allows continuous forward-facing trajectories even in scenarios where abrupt direction changes would otherwise require in-place rotation.

The kinematic model neglects dynamic effects such as mass, wheel–terrain interaction, lateral slip, and load transfer. These effects do not appear explicitly as disturbance terms in the model and no formal disturbance rejection or robustness proof is claimed. In practice, their influence manifests only as deviations in the measured pose, which are corrected indirectly by the closed-loop geometric feedback and by conservative curvature limiting. The present formulation therefore focuses on geometric feasibility and bounded curvature rather than explicit dynamic compensation.

2.5. Curvature-Constrained Control Framework

The control strategy is implemented as an event-driven finite-state machine composed of three operational states [

20]:

Align,

Goto, and

Pause. In the

Align state, the robot gradually adjusts its heading toward the next waypoint while moving at a reduced speed, using a curvature-bounded forward arc rather than an in-place rotation. Once the heading error falls below a predefined tolerance, the system transitions to the

Goto state, during which the robot advances toward the target while continuously regulating its curvature within allowable limits. When a waypoint with zero assigned speed is reached, the controller switches to the

Pause state, halts the robot, executes any pending service commands, and resumes motion after a parameterized delay.

To ensure smooth and kinematically feasible motion, angular velocity is computed using a curvature-based control strategy. Let

denote the current pose of the robot, and let

be the position of the target waypoint. The Euclidean distance to the waypoint is given by:

The desired heading is computed using the two-argument arctangent function [

18]:

To compute a smooth angular error, we use the wrapped angle difference:

From the heading error and distance, we compute an instantaneous curvature

:

where

is a small positive constant used to prevent division by zero at short distances.

To respect the robot’s physical turning limits, the curvature is clamped to a maximum value

, where

is the minimum turning radius [

19]:

where

denotes a saturation operator:

It is important to mention that is not claimed to prevent slip, it reduces the impact by avoiding aggressive, tight turns. The minimum turning radius was defined geometrically as a design parameter, independent of any dynamic or physical stress model. The objective was to ensure that the robot can reach laterally offset waypoints using smooth forward motion without requiring in-place rotation. After that, the value was tuned by slight changes based on empirical observation on one surface type, asphalt.

Specifically,

was selected as the smallest radius of a circular arc that connects the robot’s initial pose to a target waypoint located at a longitudinal offset

and a lateral offset

. Assuming a forward circular arc, the required turning radius can be computed as

which corresponds to the radius of the circle passing through the start point and the target waypoint with an initial tangent aligned to the forward direction.

The angular velocity command is obtained as

This formulation yields smooth angular behavior proportional to the alignment error while respecting the physical curvature constraint. The state machine transitions are triggered by distance and heading thresholds, ensuring deterministic progress along the waypoint sequence.

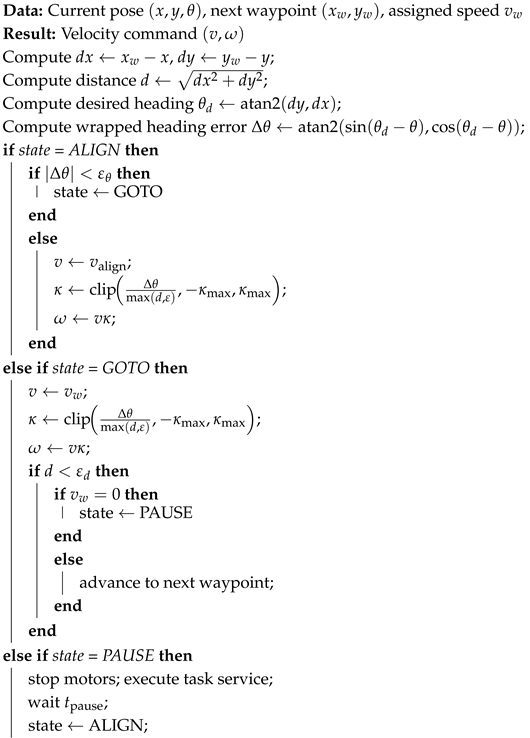

The algorithm based on the aforementioned control rules is summarized in Algorithm 1. It outlines the finite-state decision logic and the curvature-constrained computation of the angular velocity command. The parameters used during the field tests are concluded by

Table 1.

| Algorithm 1: Finite-state curvature-constrained trajectory follower. |

![Applsci 16 00322 i001 Applsci 16 00322 i001]() |

2.6. Stability Considerations

Assuming bounded curvature and positive forward velocity, the closed-loop heading error dynamics can be approximated by

which guarantees an exponential convergence of

towards zero. As a consequence, both heading and position errors remain bounded and asymptotically converge with nominal localization accuracy. The curvature constraint further ensures that motion remains geometrically feasible and mechanically smooth throughout the trajectory. The approximation in Equation (13) represents a local analysis of the unsaturated regime of the controller, where the curvature command is given by

. Under forward motion (

),

, and sufficiently small heading errors, this yields locally exponential convergence of the heading error. When curvature saturation is active, the same linearized dynamics no longer applies; however, saturation guarantees bounded curvature and angular velocity, ensuring safe and geometrically feasible motion. A global stability proof under saturation, slip, and state-machine switching is beyond the scope of this work.

2.7. Baseline Controllers for Comparison

To quantify the effect of explicit curvature saturation, we compare the proposed curvature-clipped point-to-point (P2P) controller against two geometric baselines:

2.7.1. Baseline A: Unclipped Point-to-Point (P2P)

This baseline uses the same heading-to-waypoint control law as the proposed method, but removes the curvature saturation step. In particular,

which may command curvature values exceeding

.

2.7.2. Baseline B: Pure Pursuit

We implement a standard Pure Pursuit follower on the same waypoint polyline. Given a lookahead distance

L, the algorithm selects a lookahead point on the reference path and computes curvature as

where

is the heading angle between the robot’s forward axis and the lookahead point. Unless stated otherwise, Pure Pursuit does not explicitly enforce

(as is typical in standard implementations).

3. Results

The proposed curvature-constrained trajectory control framework was validated through field experiments. The objective of these evaluations was to verify that the controller could accurately follow curvature-feasible waypoint sequences, maintain stability during state transitions, and achieve smooth motion under the physical turning constraints of a compact heavy-duty skid-steer robot.

In addition to the proposed curvature-constrained follower (curvature-clipped point-to-point, clipped P2P), two baseline controllers were evaluated on the same platform: (i) an unclipped P2P controller (identical logic but without curvature saturation), and (ii) a Pure Pursuit controller (PPC). All runs were recorded to rosbag2 for offline analysis and direct reproducibility.

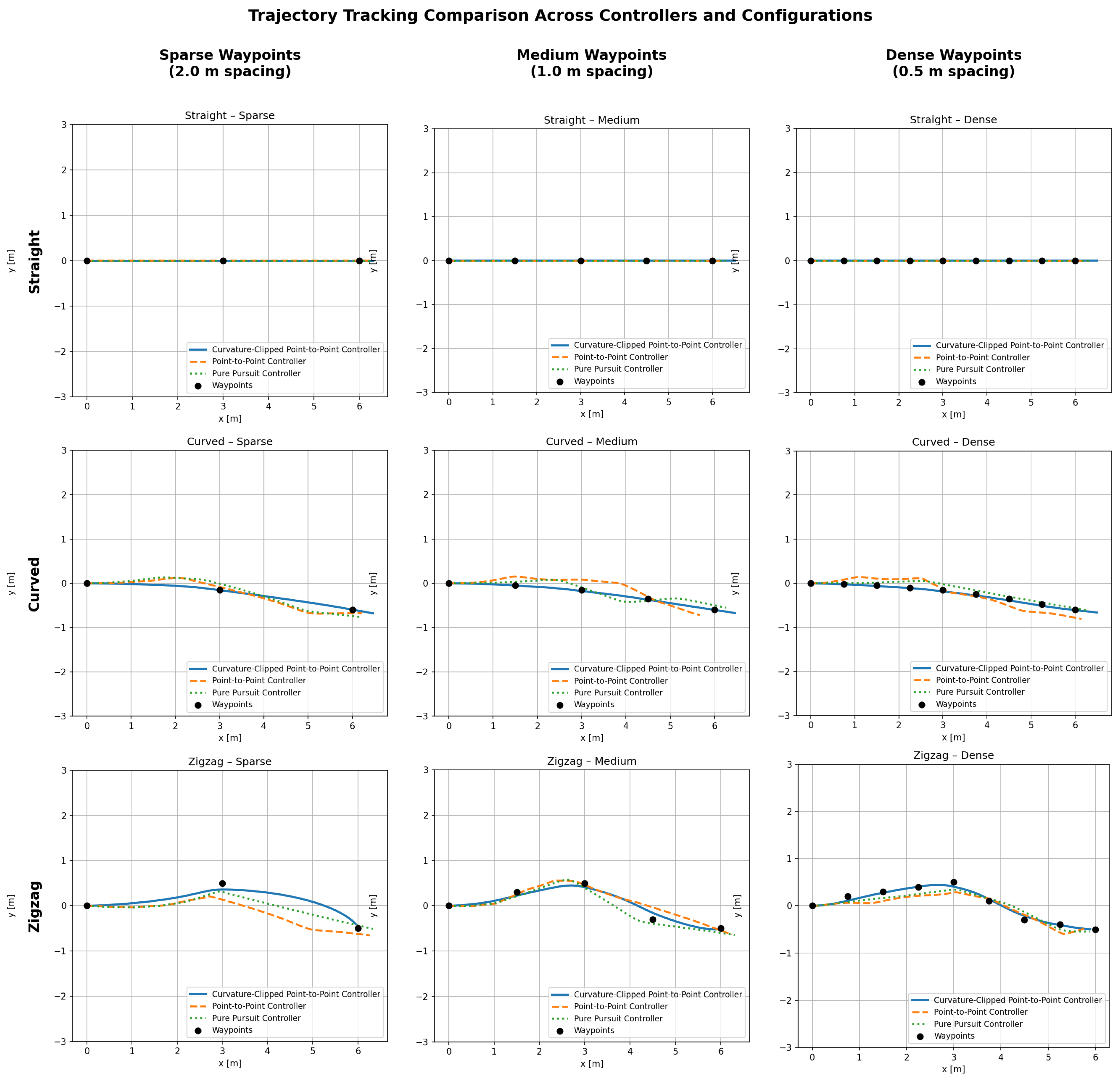

Three representative path patterns were tested: straight, curved, and zig-zag. To study waypoint-density sensitivity, each pattern was executed with three waypoint spacings: sparse (2.0 m), medium (1.0 m), and dense (0.5 m).

Figure 3 summarizes the resulting field trajectories across controllers, patterns, and densities.

For each controller–trajectory–density combination, one representative field run was analyzed; the focus of the evaluation is comparative controller behavior under identical conditions rather than statistical averaging. Runs were carried out with the same environmental conditions.

Trajectory tracking accuracy was evaluated using the recorded robot pose (from

/tf, frame

tyr_base_link) and the waypoint set (from

/waypoint_markers). For each waypoint

, we compute the closest-approach distance to the executed trajectory samples

:

and report waypoint proximity MAE, RMSE, and maximum error over the waypoint set. In addition, we report curvature statistics computed from the recorded trajectory to quantify curvature demand and to highlight violations in the unclipped baseline.

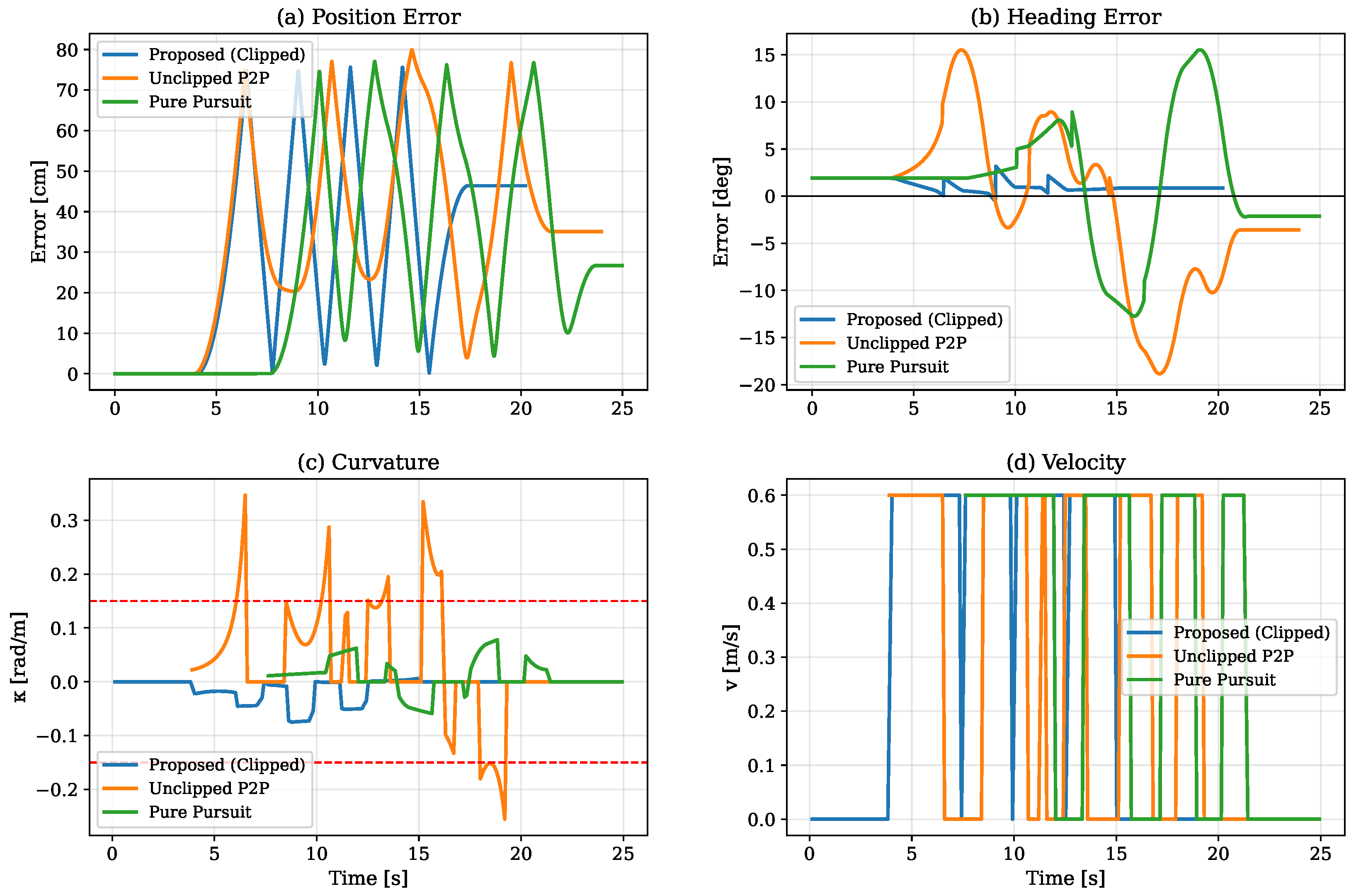

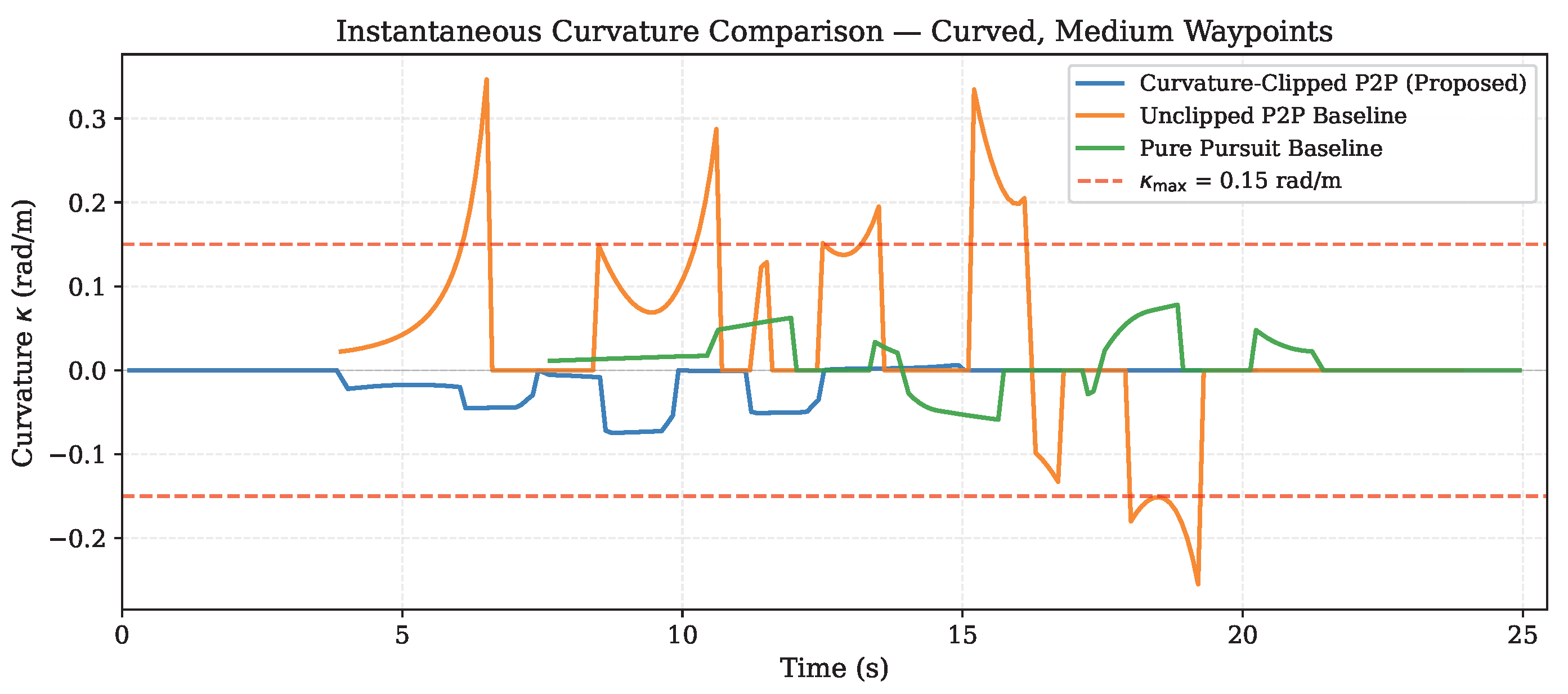

The comparison demonstrates that the curvature-clipped controller provides the most consistent performance on curvature-demanding trajectories while maintaining bounded curvature. In the Curved–Medium configuration, the proposed method achieves MAE

m, compared to

m for the unclipped baseline and

m for Pure Pursuit (

Table 2). Curvature-related differences are further illustrated by the temporal evolution and curvature comparison plots for a representative Curved–Medium run (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), where the unclipped baseline exhibits large curvature peaks while the proposed controller remains bounded.

Overall, the field experiments confirm that explicitly enforcing a curvature constraint improves reliability and repeatability on curved and zig-zag trajectories, while maintaining comparable performance on straight segments. The waypoint-density study further indicates that waypoint spacing influences tracking behavior; overly sparse waypoint sets can induce larger heading transients, while very dense waypoint sets increase the frequency of waypoint transitions in the finite-state logic.

Limitations

The experiments also highlighted several practical limitations that inform future development. The robot requires stable GNSS reception and access to RTK correction data; performance degrades in areas affected by multipath interference or limited satellite visibility. The controller further assumes that all waypoints are geometrically reachable under the robot’s curvature constraints. If waypoints are placed too close together, behind the vehicle, or require curvature exceeding the minimum turning radius, the resulting trajectory may become infeasible, currently necessitating manual adjustment of the waypoint layout.

From an evaluation perspective, the primary quantitative metric used in this work is the waypoint proximity error, defined as the closest-approach distance between the executed trajectory and each waypoint. While this metric directly reflects the controller’s ability to satisfy operator-defined navigation goals, it does not explicitly capture continuous path deviation between waypoints, particularly for sparse waypoint configurations. To address this limitation, the waypoint-based evaluation is complemented by time-resolved cross-track and heading error plots, as well as curvature profiles for representative runs, which reveal transient behavior and curvature feasibility during execution.

Finally, although the curvature constraint enforces geometrically smooth motion, the current control formulation does not explicitly model dynamic effects such as lateral slip, load transfer, or terrain-dependent traction variations. These effects are treated implicitly through closed-loop pose feedback and conservative curvature limits. Incorporating slip-aware or dynamic extensions of the model, as well as automated waypoint feasibility checks, constitutes an important direction for future work.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The results demonstrate that curvature-constrained trajectory execution provides a practical and reliable solution to guide compact heavy-duty skid-steer robots under geometric turning limits. By embedding curvature feasibility directly into the control law and employing a discrete event-driven state machine, the system achieves continuous and stable motion without requiring complex optimization or heavy computation. The experimental results confirm that the robot can follow manually defined trajectories with centimeter-scale accuracy while maintaining smooth and physically consistent motion, validating the suitability of the proposed framework for real-world deployment.

A key advantage of the presented approach is its balance between geometric rigor and implementation simplicity. The explicit curvature bound ensures that all commanded motions remain feasible for the vehicle’s kinematic configuration, thereby preventing infeasible rotational maneuvers or wheel slip that could otherwise arise on high-friction surfaces. The finite-state structure provides intuitive behavioral segmentation—alignment, forward motion, and pause, allowing for clear supervision and integration with task-level logic. The framework is fully compatible with standard ROS 2 infrastructures, which facilitates its reuse across different robotic platforms and control stacks.

The developed operator interface contributes to the system’s practical usability by providing an intuitive, map-based method for defining and editing trajectories. Its web-based deployment and integration with ROS 2 communication channels enable remote supervision and collaborative mission design, aligning with current trends toward human-in-the-loop autonomous systems. This integration is particularly relevant for outdoor robotics and industrial logistics scenarios, where situational awareness and rapid mission adjustment are critical.

The achieved positional accuracy, limited primarily by GNSS-RTK precision, indicates that the proposed control method introduces negligible additional tracking error beyond the localization uncertainty. In addition, the curvature constraint ensures kinematically smooth motion, which is expected to reduce mechanical stress on the drivetrain and improve the predictability of robot motion. Although mechanical stress was not measured directly in this work, enforcing a curvature bound effectively increases the turning radius, which is known to reduce lateral slip and internal shear forces in skid-steer locomotion. As skid-steer-induced stress increases with tighter turning radii, curvature limitation serves as a practical mitigation mechanism.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain. The current control formulation assumes planar motion and neglects dynamic slip effects, which may become significant on deformable or inclined surfaces. Additionally, the trajectory execution layer presumes that all waypoints are reachable under the robot’s curvature limits. In practice, this requires that operators avoid defining sharp reversals or excessively close points that violate geometric feasibility. Addressing such cases would require automatic trajectory regularization or online path reparameterization to enforce curvature continuity between waypoints.

Future work will extend the presented framework in several directions. First, integrating a more detailed motion model incorporating lateral slip estimation will allow adaptive adjustment of curvature limits according to terrain and surface conditions. Second, the operator interface may be expanded with semi-automated trajectory generation tools that suggest feasible paths or perform local optimization while retaining human supervision.

In conclusion, this study provides a generalized, experimentally validated framework for curvature-constrained motion control of compact heavy-duty skid-steer robots. The proposed approach achieves high accuracy and stability within the physical constraints of real-world platforms while maintaining transparency, modularity, and real-time performance. These properties make it a suitable foundation for future developments in heavy-duty mobile robotics, where precise, smooth, and geometrically feasible motion is essential for safe and reliable autonomous operation.