Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a prevalent mental health condition that requires accurate and objective diagnostic tools. Electroencephalogram (EEG) signals provide valuable insights into brain activity and have been widely studied for mental disorder classification. In this study, we propose a novel DML + ANFIS framework that integrates deep metric learning (DML) with an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) for the automated diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) using EEG time series signals. Time–frequency features are first extracted from raw EEG signals using the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) and the continuous wavelet transform (CWT). These features are then embedded into a low-dimensional space using a DML approach, which enhances the inter-class separability between MDD and healthy control (HC) groups in the feature space. The resulting time–frequency feature embeddings are finally classified using an ANFIS, which integrates fuzzy logic-based nonlinear inference with deep metric learning. The proposed DML + ANFIS framework was evaluated on a publicly available EEG dataset comprising MDD patients and healthy control (HC) subjects. Under subject-dependent evaluation, the STFT-based DML + ANFIS and CWT-based models achieved an accuracy of 92.07% and 98.41% and an AUC of 97.28% and 99.50%, respectively. Additional experiments using subject-independent cross-validation demonstrated reduced but consistent performance trends, thus indicating the framework’s ability to generalize to unseen subjects. Comparative experiments showed that the proposed approach generally outperformed conventional deep learning models, including Bi-LSTM, 2D CNN, and DML + NN, under identical experimental conditions. Notably, the DML module compressed 1280-dimensional EEG features into a 10-dimensional embedding, thus achieving substantial dimensionality reduction while preserving discriminative information. These results suggest that the proposed DML + ANFIS framework provides an effective balance between classification performance, generalization capability, and computational efficiency for EEG-based MDD diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common and serious mental illnesses affecting more than 320 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. MDD is characterized by symptoms such as persistent low mood, loss of interest and pleasure, cognitive decline, feelings of worthlessness, and sleep disturbances, which significantly impair an individual’s emotional and social functioning and quality of life [2]. These clinical features are also identified as key diagnostic criteria for MDD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) [3,4]. Furthermore, MDD is characterized by a high relapse rate and an increased risk of suicide, often leading to social dysfunction and disability [5]. Therefore, early diagnosis and timely intervention are crucial. In a 2008 report, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified MDD as the third leading cause of global disease burden and predicted that its proportion will increase by 2030 [6]. Despite this severity, current clinical diagnostic methods for MDD still have inherent limitations. Current assessments mainly depend on patients’ self-reported symptoms obtained through clinical interviews or standardized questionnaires, including the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [7] and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [8]. These approaches are susceptible to evaluator bias, patient temporal emotional states, and response bias, thus making them inaccurate in reflecting actual symptom changes and potentially compromising the consistency and objectivity of diagnosis.

To overcome these limitations, recent research has increasingly focused on developing objective diagnostic methods for MDD based on biosignals. In particular, electroencephalography (EEG) detects biosignals that directly reflect the brain’s electrical activity, and it offers the advantages of being non-invasive and cost-effective and providing high temporal resolution [9]. Owing to these advantages, EEG has been widely explored as a neurophysiological biomarker for identifying abnormal brain dynamics associated with MDD. Therefore, research has been actively conducted recently to automatically extract and classify characteristic EEG patterns related to MDD states using machine learning and deep learning techniques [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. This approach complements subjective assessment methods based on clinical questionnaires and is being evaluated as a novel direction for enabling quantitative and reproducible MDD diagnosis.

Recently, the EEG-based diagnosis of MDD has attracted increasing attention with the rapid advancement of AI and deep learning technologies. Traditional statistical and machine learning methods have struggled to effectively capture the complex temporal and frequency patterns of EEG signals. To overcome these limitations, recent studies have focused on deep learning-based and hybrid neural architectures that automatically learn discriminative representations of EEG data [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Rafiei et al. [10] proposed a deep learning-based approach for the automatic detection of MDD using EEG signals. A customized InceptionTime model was constructed by directly inputting 19-channel raw EEG time series data, thereby improving computational efficiency by eliminating the need for separate feature extraction or image transformation processes. The experimental results demonstrated an accuracy of 91.67% when using all 19 channels and 87.5% even after reducing the number of channels to 10.

Hashempour et al. [11] proposed a hybrid CNN–TCN (Convolutional Neural Network–Temporal Convolutional Network) model to predict the severity of depression by analyzing EEG signals based on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores. Using EEG recordings from 119 participants, the model was evaluated through 10-fold cross-validation, demonstrating superior performance compared to conventional machine learning and deep learning approaches. Specifically, the CNN–TCN model achieved high prediction accuracy with an MSE of 5.64 ± 1.6 and 9.53 ± 2.94 and MAE of 1.73 ± 0.27 and 2.32 ± 0.35 in the eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions, respectively.

Bagherzadeh et al. [12] proposed a hybrid approach that combines a Wavelet Convolutional Neural Network (WCNN) and a Multi-class Support Vector Machine (MSVM) to enhance emotional state recognition from EEG signals. Experimental evaluations on the DEAP and MAHNOB-HCI datasets demonstrated that features extracted from the intermediate convolutional layer (Res2a) of ResNet-18 led to approximately 20% and 12% improvements in average accuracy, precision, and recall compared to conventional methods. Furthermore, when combining scalograms from key brain regions such as the frontal and parietal lobes, the proposed method achieved average accuracies of 77.47% on the MAHNOB-HCI dataset and 87.45% on the DEAP dataset.

Xia et al. [13] proposed an end-to-end deep learning model for classifying MDD using resting-state EEG data. The proposed framework integrates a multi-head self-attention mechanism to automatically learn inter-channel dependencies, followed by a parallel dual-branch CNN module for high-level feature extraction and a fully connected layer for final classification. The model was evaluated using EEG recordings from 57 subjects (34 MDD patients and 23 healthy controls) and achieved an average classification accuracy of 91.06% through leave-one-subject-out cross-validation (LOSO-CV).

Wang et al. [14] proposed DiffMDD, which is a diffusion-based deep learning framework for the diagnosis of MDD using EEG signals. The framework first employs a forward diffusion noise learning module to extract robust and noise-invariant features, addressing the inherent noise characteristics of EEG data. Subsequently, a reverse diffusion-based data augmentation module is introduced to generate high-quality and diverse EEG samples, thereby enhancing the classifier’s ability to learn generalized representations. Finally, the classifier is retrained using the augmented EEG dataset to further improve diagnostic performance. Experimental evaluations on two publicly available EEG datasets demonstrated that the proposed diffusion-based framework effectively enhances both noise robustness and generalization capability in MDD detection.

Cui et al. [15] proposed a multi-view sparse dynamic graph convolution-based region-attention feature fusion network (MV-SDGC-RAFFNet) for the EEG-based diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). The proposed model incorporates a multi-view (MV) feature extractor that simultaneously captures the temporal, spectral, and time–frequency characteristics of EEG signals, thereby providing a comprehensive representation of the patient’s emotional state. A sparse dynamic graph convolution network (SDGCN) is then employed to effectively learn inter-channel relationships among high-dimensional EEG features while mitigating the over-smoothing and redundant edge issues inherent in conventional graph neural networks (GNNs). Finally, a region-attention feature fusion network (RAFFNet) is introduced to adaptively integrate multi-domain features by assigning attention weights to different brain regions. The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed method achieved outstanding MDD detection performance, yielding accuracies of 95.53% and 99.19% on the MODMA and HUSM datasets, respectively.

Kowli et al. [16] proposed three novel EEG-based models for MDD diagnosis. First, they modeled multi-channel EEG signals as multivariate time series and built a MultiRocket-based multivariate time series classification (MTSC) model. This model effectively learned multidimensional temporal information about the EEG. Second, to utilize the EEG’s temporal spatial information, the authors represented the multi-channel EEG as a temporally evolving graph signal and performed MDD detection as a graph signal classification problem using the Temporal Dynamic Graph Neural Network (TodyNet) architecture. Third, the authors proposed a feature connectivity-based model to quantify the relationships between EEG channels, utilizing inter-channel interaction information as features. Finally, they integrated the outputs of the three models to build an integrated MDD detection model that combines the unique information from each approach, achieving a classification accuracy of approximately 95%.

Umair et al. [17] proposed a federated learning framework that integrates machine learning and deep learning techniques to classify patients with MDD and healthy controls using EEG signals. In their study, they combined machine learning algorithms such as Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and Gradient Boosting with deep learning models based on transformers and Autoencoders to capture the complex temporal and spectral patterns in EEG signals. The experimental results demonstrated that the Transformer–Random Forest ensemble model achieved a classification accuracy of up to 99% while maintaining over 95% accuracy across three client nodes in the federated setting. Notably, the best-performing client achieved 96.23% accuracy, thus indicating that the proposed approach can simultaneously ensure high diagnostic performance and data privacy even under conditions of limited computational resources.

Recently, a wide range of deep learning and hybrid models have been proposed for the EEG-based diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD), including architectures based on CNNs, TCNs, transformers, and graph neural networks. These approaches have improved diagnostic accuracy by enabling the automatic learning of complex EEG patterns without manual feature extraction. However, several limitations remain. Many existing models insufficiently capture the non-stationary nature of EEG signals and the complex interactions between temporal and frequency components. In addition, EEG signals are inherently noisy and exhibit substantial inter-subject variability, which can degrade learning stability and generalization performance. Moreover, increasing model complexity often leads to reduced computational efficiency and training robustness.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a hybrid framework that integrates deep metric learning (DML) with an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) for EEG-based major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosis. In the proposed framework, time–frequency representations extracted using the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) and continuous wavelet transform (CWT) are first mapped into a compact low-dimensional embedding space via DML, thereby enabling substantial dimensionality reduction while preserving discriminative information. This compact representation contributes to improved computational efficiency and controlled model complexity, which is particularly important under limited data conditions. An adaptive temperature mechanism is incorporated into the contrastive learning objective to enhance training stability and representation balance. The resulting embeddings are then classified using the ANFIS, which models nonlinear decision boundaries in the low-dimensional space. The proposed framework is evaluated under both subject-dependent and subject-independent validation protocols to assess classification performance and generalization capability in realistic EEG-based diagnostic settings.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the main methodologies used in the proposed framework. Specifically, it introduces the concepts and application of the STFT and CWT methods for extracting time–frequency features from EEG signals. It also details the fundamental principles and architectural design of the DML + ANFIS model, which integrates DML with the ANFIS proposed in this study. Section 3 describes the MDD EEG dataset and the data preprocessing procedure used on the data, followed by a performance evaluation and comparative analysis of the DML + ANFIS model using STFT- and CWT-based feature embedding. Section 4 discusses the experimental results and the performance characteristics of the proposed model. Finally, Section 5 concludes this paper with conclusions and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

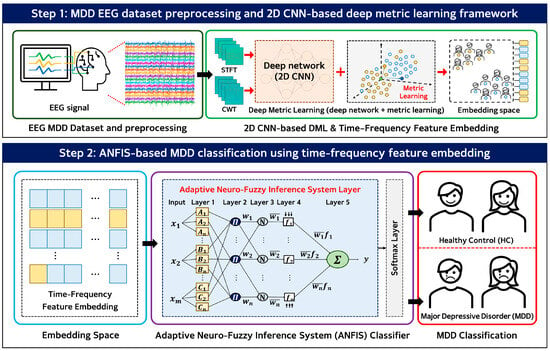

In this study, we propose an integrated EEG-based deep metric learning and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (DML + ANFIS) framework for the diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). As illustrated in Figure 1, the proposed framework is organized as a two-stage pipeline that sequentially transforms raw EEG signals into discriminative low-dimensional representations and performs final classification.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the proposed DML + ANFIS framework. Step 1: EEG signals are transformed into time–frequency representations and embedded using a 2D CNN–based deep metric learning method. Step 2: The resulting feature embeddings are classified using an ANFIS-based classifier to distinguish HC and MDD subjects.

In the first stage, raw EEG signals are preprocessed and transformed into the time–frequency domain using the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) and continuous wavelet transform (CWT) to reflect the non-stationary characteristics of EEG signals. These transformations generate two-dimensional time–frequency representations that jointly encode temporal and spectral information. The resulting time–frequency features are then provided as inputs to a 2D CNN-based deep metric learning (DML) network. The DML network is trained using a contrastive learning objective to map high-dimensional time–frequency features into a compact embedding space while preserving discriminative information. In this study, the DML network produces fixed-length embeddings of 10 dimensions, achieving substantial dimensionality reduction. A normalized temperature-scaled cross-entropy (NT-Xent)-based loss function with an adaptive temperature mechanism is employed to improve training stability and maintain balanced representations, particularly under limited data conditions.

In the second stage, the low-dimensional embeddings generated by the DML network are used as inputs to an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) classifier. The ANFIS performs nonlinear classification in the compact embedding space through fuzzy inference and determines whether each sample corresponds to an MDD patient or a healthy control (HC) subject. The number of fuzzy rules is set equal to the cluster number k, which serves to control model complexity, and no explicit rule pruning strategy is applied.

All experiments were conducted using both subject-dependent and subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation protocols to evaluate classification performance and generalization capability while preventing subject-level data leakage.

2.1. Time–Frequency Feature Extraction Method from EEG Signals

In this study, a time–frequency transformation was applied to EEG signals to facilitate deep metric learning (DML) based on a 2D CNN. Since EEG signals exhibit non-stationary characteristics, stationary frequency analysis alone cannot sufficiently represent the spectral changes in the signal over time [18]. To address this, two signal processing methods—the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) [19] and the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) [20]—were employed to generate two-dimensional time–frequency representations that simultaneously reflect both the temporal changes and frequency components of EEG signals. The transformed time–frequency representations were used as inputs to the DML network to learn complex spectral patterns that distinguish MDD from HC. These time–frequency features served as the foundation for effectively generating low-dimensional time–frequency feature embeddings, which were subsequently utilized by the ANFIS classifier.

2.1.1. Short-Time Fourier Transform

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) is one of the most widely used methods for transforming non-stationary signals, whose frequency components change over time, into the frequency domain. In this method, the input signal is segmented into fixed-length windows, and the Fourier transform is applied to each segment to capture the evolution of spectral information across the time and frequency domains [21]. This process generates a spectrogram, which represents the frequency distribution of the signal over time, and is expressed as the magnitude squared of the complex result of the STFT. The STFT exhibits a trade-off between time resolution and frequency resolution depending on the window length. Specifically, shorter windows yield higher temporal resolution at the expense of frequency resolution, while longer windows provide better frequency resolution but reduced temporal precision [22]. Therefore, the STFT has the advantage of allowing for the precise observation of frequency variations within a given interval and is widely used for analyzing the frequency characteristics of time-varying signals such as EEG signals. The STFT formula is as shown in Equation (1) [23].

where represents the STFT of the EEG signal, is the input EEG signal, is the window function centered at time , and and represent time and frequency variables, respectively. The window function influences the time–frequency localization of the signal and is commonly implemented using Gaussian or Hamming windows. In this study, a Hamming window was employed to mitigate spectral leakage while maintaining a reasonable balance between time and frequency resolution, which is important for analyzing nonstationary EEG signals.

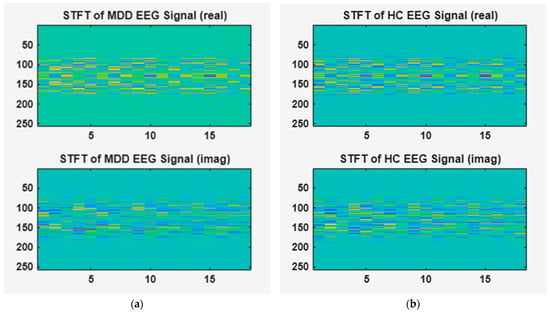

Figure 2 shows the results of the STFT applied to the EEG signals of MDD patients and HC groups. In this figure, (a) corresponds to an EEG signal from a subject with MDD, whereas (b) represents an EEG signal from a HC. We used the STFT by overlapping Hamming windows with a signal length of 1280, an FFT length of 256, and a 1 s window by approximately 0.75 s. Additionally, the spectral energy distribution of and phase variation in the signal are visually represented, including both real and imaginary components. The upper and lower parts of Figure 2 show the real and imaginary parts of the STFT-transformed EEG signal, respectively.

Figure 2.

Time–frequency features of EEG signals obtained using STFT. (a) STFT of MDD EEG signal, (b) STFT of HC EEG signal.

2.1.2. Continuous Wavelet Transform

The continuous wavelet transform (CWT) is a method that can analyze signals with various time and frequency resolutions and precisely represent the time–frequency characteristics of non-stationary signals. While the Fourier transform provides a fixed frequency resolution for the entire signal, the CWT dynamically adjusts the time and frequency resolution according to a scale factor, allowing for the analysis of detailed changes in specific intervals [22,24]. These characteristics make the CWT effective in analyzing biosignals, such as EEG signals, whose frequency components vary over time. The analytic wavelet is a complex-valued wavelet whose Fourier transform is zero in the negative frequency domain, providing both amplitude and phase information in time–frequency analysis. Because the complex-valued wavelet coefficients precisely capture the instantaneous spectral variations and phase fluctuations in a signal, the analytic wavelet-based CWT is particularly suitable for analyzing the temporal and frequency changes in non-stationary EEG signals [25]. The CWT formula is as shown in Equation (2) [26].

where represents the CWT for the EEG signal x(t), denotes the mother wavelet function, and * represents the complex conjugate operator [27]. The scale factor controls the dilation or compression of the mother wavelet, and is the transform or time shift.

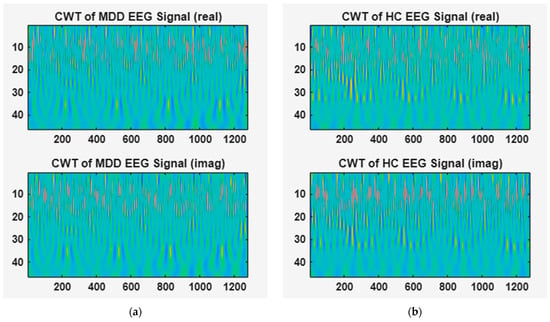

Figure 3 illustrates the results of the CWT applied to the EEG signals of MDD patients and HC groups. In this figure, (a) corresponds to an EEG signal from a subject with MDD, whereas (b) represents an EEG signal from a HC. In this study, analytic Morlet (Gabor) wavelets, which produce complex-valued coefficients in the time domain, were used to extract CWT-based features. The transformation was performed over a signal length of 1280 and a frequency range of [0.01–0.23], visually representing the signal’s spectral energy distribution and phase shift, including both real and imaginary components. The upper and lower parts of Figure 3 show the real and imaginary parts of the CWT-transformed EEG signal, respectively.

Figure 3.

Time–frequency features of EEG signals obtained using CWT. (a) CWT of MDD EEG signal, (b) CWT of HC EEG signal.

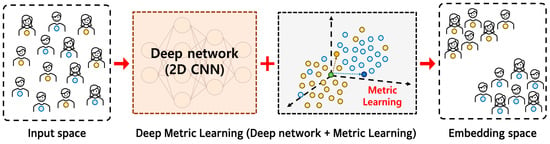

2.2. Deep Metric Learning

In this study, we applied deep metric learning (DML), which is a technique that integrates deep learning-based representation learning and metric learning [28], to enhance the discriminative power of EEG signals for diagnosing MDD. The core idea of DML is to project input data into an embedding space through a deep neural network and to learn a distance space in which samples belonging to the same class are positioned close together, whereas those from different classes are placed farther apart [29]. Through this process, the model learns a distance-based representation function that can effectively distinguish the similarity and difference between EEG signals. Figure 4 shows a conceptual overview of the DML architecture, illustrating how input EEG signals are projected into an embedding space via a 2D CNN-based deep network, in which class separability is optimized through metric learning.

Figure 4.

Overview of 2D CNN-based deep metric learning process.

In the deep learning training process, we used normalized temperature-scaled cross-entropy (NT-Xent) [30], which is a loss function based on contrastive learning. Pairwise, NT-Xent computes the cosine similarities among all samples within a mini-batch and generates a similarity matrix in the range of [−1, 1]. This matrix is subsequently rescaled using a temperature coefficient . Low values of temperature coefficient encourage the model to focus more on hard negative pairs that are difficult to distinguish, and the cross-entropy objective is optimized to maximize the similarity of positive pairs while minimizing that of negative pairs. In this study, to complement the limitations of the existing NT-Xent loss, we introduced the adaptive temperature method and improved it to dynamically modulate the contrast intensity according to the difficulty of the sample. Since conventional NT-Xent uses a single constant temperature for all samples, this can result in excessive penalties for anchor–hard examples with low similarity, destabilizing the learning process. To address this, an individual temperature was assigned to each anchor sample based on its maximum positive similarity . Its definition is shown in Equation (3). By incorporating this equation into the conventional NT-Xent loss function, the adaptive temperature NT-Xent loss function was constructed. The overall equation is shown in Equation (4) [30].

where is the batch size, represents the cosine similarity, and is the temperature parameter for each sample. In this study, the batch size was set to 32, and the temperature range was defined as . Specifically, a low temperature was applied to ‘easy’ samples with high similarity to enhance the contrastive effect, and a high temperature was applied to ‘difficult’ samples with low similarity to mitigate excessive loss. This adaptive strategy dynamically adjusts the temperature for each sample while preserving the original NT-Xent framework, thereby enhancing both training stability and discriminative performance without introducing additional parameters or memory overhead. Through this, the DML model in this study could effectively generate a low-dimensional time–frequency feature embedding that reflects the subtle feature differences between MDD and HC groups from EEG signals.

2.3. Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System

The adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) is a hybrid inference model that combines the strengths of fuzzy inference and artificial neural networks (ANNs). First proposed by Jang [31], the ANFIS is designed to effectively model nonlinear and complex systems by integrating the rule generation capability based on fuzzy logic with the learning capability of neural networks. The ANFIS automatically learns fuzzy rules in the form of “If–Then” from input–output data, and the parameters of each rule are optimized using a combination of the backpropagation (BP) algorithm and the least squares estimation (LSE) method [32]. This structure has the significant advantage of imparting the adaptive learning capability of neural networks while maintaining the interpretability of fuzzy systems.

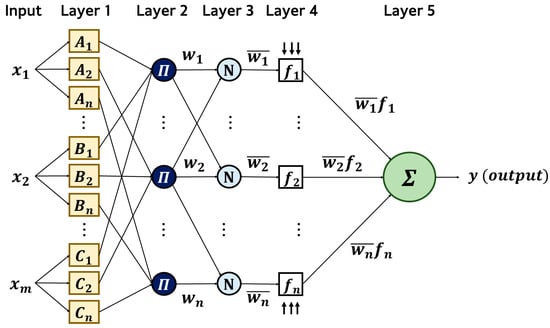

Figure 5 shows the overall structure of the ANFIS. This model is based on the Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy model and generally consists of five layers. The first layer transforms input variables into corresponding fuzzy sets and calculates the membership degree of each membership function. The second layer determines the rule firing strength based on the membership degree. The third normalizes the rule firing strength, and the fourth calculates the conclusion of each rule based on the normalized firing strengths. Finally, the fifth layer synthesizes the outputs of all rules to derive the final result.

Figure 5.

ANFIS architecture.

Equations (5)–(10) present the hierarchical structure and calculation procedure of the ANFIS model in mathematical form. The input data are processed through a series of sequential operations, during which the parameters of the membership functions, fuzzy rules, and consequent parts are iteratively updated [33,34]. Here, m denotes the number of input channels, and k denotes the number of fuzzy rules. In the ANFIS layer, the number of fuzzy rules is equal to the cluster number k, such that each cluster corresponds to one rule defined over the fixed 10-dimensional DML embedding. No explicit rule pruning or regularization is applied; instead, model complexity is controlled through the choice of k.

- Layer 1 (Fuzzification Layer): In the first layer, input data is converted into linguistic variables, and the corresponding membership degrees are computed using the premise parameters, as defined in Equation (5).The membership function uses a generalized bell-shaped membership function, as shown in Equation (6).where {} represent the premise parameters, is the width of the membership function, controls its slope or tail shape, and indicates the center of the function.

- Layer 2 (Rule Layer): In the second layer, the firing strength of each fuzzy rule is computed by multiplying the membership values obtained from Layer 1. The resulting rule activations are mathematically expressed in Equation (7).

- Layer 3 (Normalization Layer): In the third layer, the firing strengths of each rule are normalized by dividing them by the sum of all firing strengths, as in Equation (8).

- Layer 4 (Defuzzification Layer): The fourth layer receives the normalized firing strengths and the consequent parameter set {, , , } as input and calculates the conclusion output of each rule as in Equation (9).

- Layer 5 (Output Layer): In the fifth layer, the outputs of all rules are integrated using the weighted average method, as shown in Equation (10), to derive the final result.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. EEG Dataset of MDD Patients and Healthy Controls

This study utilized the EEG dataset of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and healthy controls (HCs), published by Mumtaz et al. [35,36]. The dataset, titled “MDD patients and healthy controls EEG data (new)”, is publicly available on Figshare. Each EEG sample is labeled “MDD” or “HC” to distinguish between the subject groups.

The MDD patient group consisted of 34 patients, including 17 men and 17 women, with a mean age of 40.3 years (±12.9 years). All patients were diagnosed with MDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) criteria through a clinical interview conducted by board-certified psychiatrists. EEG signal recordings were obtained prior to the initiation of any pharmacological treatment to minimize potential signal distortion caused by medication effects. The HC group consisted of 30 individuals with no history of psychiatric disorders, including 21 men and 9 women with a mean age of 38.3 years (±15.6), comparable to the MDD group. All participants were thoroughly informed about the purpose and procedures of this study and provided written informed consent prior to participation.

EEG signal recordings were acquired under resting-state conditions. Data were recorded for five minutes each under both eyes-closed and eyes-open conditions, yielding a total of ten minutes of EEG data per subject. All recordings were performed using the Brain Master Discovery system, and electrode placement followed the international 10–20 system. A total of 19 electrodes were positioned at the following scalp sites: Fp1, Fp2, F7, F3, Fz, F4, F8, T3, C3, Cz, C4, T4, T5, P3, Pz, P4, T6, O1, and O2. All EEG signals were digitized at a sampling rate of 256 Hz. A band-pass filter ranging from 0.1 to 70 Hz was applied to suppress low-frequency drift and high-frequency artifacts, while a 50 Hz notch filter was used to eliminate power-line interference.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

In this study, a series of preprocessing steps were performed to ensure signal quality and compatibility with the deep learning architecture while preserving the intrinsic nonlinear characteristics of the EEG signals. First, linear detrending was applied to remove the direct current (DC) drift component. Since the recording durations varied across subjects, all EEG signals were aligned by truncating them to the shortest duration to ensure a uniform input shape. Subsequently, Z-score normalization was performed on each channel independently to standardize the signals to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This step is crucial for mitigating amplitude scaling issues and ensuring stable convergence during the training of the deep metric learning network. We deliberately avoided aggressive artifact removal techniques, such as Independent Component Analysis (ICA), to prevent the potential loss of neurophysiological information essential for MDD diagnosis.

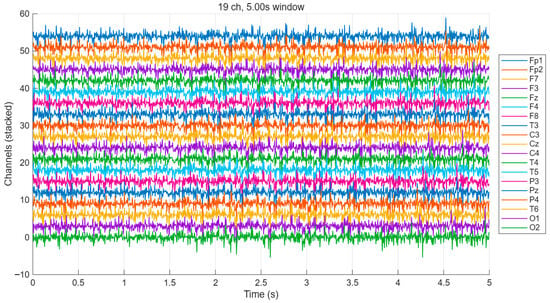

Since EEG signals have non-stationarity, meaning that statistical characteristics change over time, the sliding window-based segmentation of the entire signal was performed to satisfy the quasi-stationarity assumption. Each EEG recording was shape-normalized so that channels corresponded to rows and time to columns. The signals were segmented into 5 s epochs (1280 samples) with a 50% overlap, corresponding to a 2.5 s step, while recordings shorter than the defined segment length were excluded from the analysis. Figure 6 illustrates the segmentation of EEG signals into 5 s windows for each channel, which were subsequently used as input samples for model training.

Figure 6.

Visualization of segmented EEG signals for each channel (5 s window).

3.3. Experimental Results and Performance Analysis

In this study, time–frequency features were extracted from EEG data using the STFT and CWT. These two methods were employed to compare and analyze how different time–frequency representations influence the diagnostic performance of MDD classification. The performance evaluation primarily focused on a deep learning and neuro-fuzzy fusion architecture that combines DML and the ANFIS, which is referred to as the DML + ANFIS model. Variations in key performance metrics—including classification accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, and area under the ROC curve (AUC)—were analyzed according to the time–frequency feature extraction method and the number of clusters k.

The experiments were conducted under two distinct scenarios, and the overall experimental environment is summarized in Table 1. Each experiment was performed on the same EEG dataset, while the learning conditions were controlled by altering the feature extraction methods and clustering configurations. The training parameters of the deep learning model are summarized in Table 2. Specifically, the number of training epochs was set to 30, the L2 regularization coefficient to , the learning rate to , and the mini-batch size to 64. All models were trained under the same experimental conditions to ensure fairness and consistency, thus enabling a reliable comparison of the diagnostic performance across different deep learning-based architectures.

Table 1.

Experimental environment.

Table 2.

Setting the training parameters of the deep learning model.

3.3.1. Analysis of DML + ANFIS Model Performance with STFT Time–Frequency Features

The first experiment aimed to evaluate and analyze the diagnostic performance of the DML + ANFIS model for MDD using the STFT-based time–frequency features extracted from the MDD EEG dataset. Table 3 presents the performance of the DML + ANFIS model with varying numbers of clusters (k), using 10-dimensional STFT time–frequency feature embeddings extracted from the MDD EEG dataset as input.

Table 3.

The performance of the DML + ANSFIS model according to the number of clusters using STFT time–frequency feature embedding.

As shown in Table 3, the DML + ANFIS model maintained stable classification performance, achieving over 90% accuracy across all numbers of clusters (k). Specifically, when k = 2, the model achieved an accuracy of 91.54%, an F1-score of 91.53%, a specificity and sensitivity of 91.50%, and an AUC-ROC of 97.31%. As the number of clusters increased to k = 3 and k = 4, the accuracy slightly decreased to 90.66% and 90.48%, respectively. This minor decline may be attributed to increased uncertainty in the data boundaries as the number of clusters grows. In contrast, when k = 5, the model achieved the best overall diagnostic performance. At this setting, both the accuracy and F1-score reached 92.07%, while specificity and sensitivity were 92.09%, and the AUC-ROC reached 97.28%. These results indicate that the model achieved the most effective learning of cluster density and distribution at k = 5, thus optimizing the distance-based representation of STFT-derived time–frequency features.

However, when k increased to 6, the model’s performance declined slightly, with an accuracy of 91.37%, an F1-score of 91.35%, and an AUC of 97.09%. These findings suggest that the model’s performance tends to degrade when the cluster number is either too small (k = 2) or excessively large (k ≥ 6). A small number of clusters may result in insufficient data representation, while an excessive number can lead to overfitting and ambiguous inter-cluster boundaries. Therefore, the intermediate cluster configuration (k = 5) yielded the highest generalization capability, demonstrating that the DML + ANFIS architecture effectively distinguishes complex time–frequency patterns within the STFT feature space and captures the nonlinear distribution of EEG signals. Overall, the DML + ANFIS model utilizing STFT-based time–frequency features achieved an average accuracy of approximately 91% and an AUC-ROC of about 97% in classifying MDD EEG data, thereby confirming its stable and reliable diagnostic performance for major depressive disorder detection.

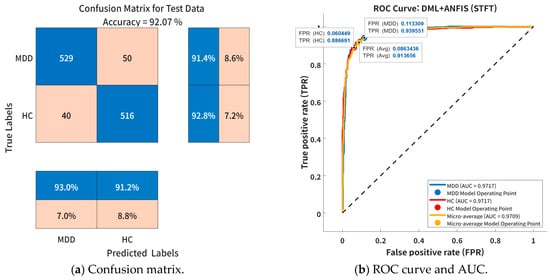

Figure 7 illustrates the classification performance of the proposed DML + ANFIS model using STFT-based time–frequency features at the optimal cluster configuration (k = 5). Figure 7a presents the confusion matrix for the test dataset. The model achieved high classification performance for both MDD patients and HCs, with classification accuracies of 91.4% and 92.8%, respectively. A total of 50 MDD samples and 40 HC samples were misclassified. Figure 7b presents the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the AUC for the same model. For the MDD group, the true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR) were 0.9395 and 0.1133, respectively, while for the HC group, the TPR and FPR were 0.8867 and 0.0604, respectively. These results indicate that the model effectively maintained high sensitivity while minimizing false positive errors. The AUC values for both MDD and HC were 0.9717, demonstrating that the model was capable of near-perfect discrimination between the two groups. Furthermore, the micro-averaged AUC was 0.9709, thus confirming the model’s excellent overall discriminative capability in EEG-based MDD diagnosis.

Figure 7.

Classification performance of proposed DML + ANFIS model (k = 5) using STFT-based time–frequency feature embedding: (a) confusion matrix for test dataset, and (b) ROC curve and AUC values for MDD and HC groups.

Table 4 shows a comparative analysis of the MDD classification performance between the proposed DML + ANFIS model and conventional deep learning-based models when using STFT-based time–frequency features as input. As shown in Table 4, the Bi-LSTM model demonstrated relatively low classification performance, achieving an accuracy of 72.09%, an F1-score of 71.83%, a specificity and sensitivity of 71.92% each, and an AUC-ROC of 80.79%. This indicates that although the Bi-LSTM architecture was able to capture a portion of the temporal dependencies inherent in EEG signals, it was insufficient in representing the complex and distributed time–frequency characteristics present in the data. In contrast, the 2D CNN model achieved improved performance with an accuracy of 84.21% and an AUC-ROC of 93.12%, thus outperforming the Bi-LSTM model. This improvement can be attributed to the CNN’s capability to effectively extract spatial and localized spectral patterns from STFT spectrogram representations. However, the model still exhibited limitations in capturing the nonlinear and dynamic nature of EEG signals, which are critical for precise MDD classification.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of proposed model with traditional deep learning models using STFT time–frequency features.

Meanwhile, when the STFT-based time–frequency feature embeddings extracted through DML were applied to a neural network (NN) classifier (DML + NN), performance variations were observed depending on feature dimensionality. The DML + NN model, which utilized 256-dimensional embeddings, achieved superior diagnostic performance compared to the CNN-based model, attaining an accuracy of 90.40%, an F1-score of 90.38%, and an AUC-ROC of 95.98%. In contrast, the DML + NN model using 10-dimensional embeddings exhibited a slight decline in performance, with an accuracy of 88.63% and an AUC-ROC of 90.15%. This result can be attributed to the loss of discriminative information during the dimensionality reduction process, which in turn reduced the overall feature representational capacity of the model.

In comparison, the proposed DML + ANFIS model effectively mitigated this limitation. With a fixed temperature setting (τ = 0.07), the DML + ANFIS model achieved an accuracy of 91.51% and an AUC-ROC of 96.26%, already surpassing all baseline models. Furthermore, by incorporating the adaptive temperature strategy, the DML + ANFIS model (k = 5, 10-dimensional embedding) achieved the best overall performance, with an accuracy and F1-score of 92.07%, a specificity and sensitivity of 92.09%, and an AUC-ROC of 97.28%. This improvement demonstrates that adaptive temperature scaling plays a critical role in enhancing metric learning by dynamically adjusting contrastive intensity according to sample difficulty. Consequently, the low-dimensional embeddings generated by DML become more discriminative and are effectively exploited by the neuro-fuzzy inference mechanism to construct robust nonlinear decision boundaries.

Overall, the proposed DML + ANFIS framework achieved an accuracy improvement of approximately 20% compared to the Bi-LSTM model and about 8% compared to the 2D CNN while also outperforming the DML + NN model despite using significantly lower-dimensional embeddings. In terms of AUC-ROC, performance gains ranging from approximately 1% to 16% were observed across different baseline models. These results confirm that integrating deep metric learning with adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference substantially enhances both the discriminative capability and generalization performance of EEG-based MDD diagnosis using STFT time–frequency representations.

This experiment was conducted to further evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed DML + ANFIS model using subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation with STFT-based time–frequency feature embeddings. In this setting, EEG data were partitioned at the subject level to ensure that data from the same subject were not simultaneously included in both the training and testing sets. Table 5 summarizes the classification performance of the DML + ANFIS model using 10-dimensional STFT-based feature embeddings under the subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation protocol.

Table 5.

Performance of DML + ANSFIS model according to number of clusters using STFT time–frequency feature embedding under subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation.

As shown in Table 5, the DML + ANFIS model demonstrated stable and consistent classification performance across different cluster configurations, despite the increased difficulty introduced by subject-independent evaluation. The classification accuracy ranged from 78.36% to 80.21%, while the F1-score varied between 76.86% and 79.19%. Specificity and sensitivity were observed in the ranges of 82.67–85.87% and 71.49–76.14%, respectively. In addition, the AUC-ROC values remained consistently high across all values of k, ranging from 88.07% to 89.97%, thus indicating reliable discriminative capability under subject-independent conditions. The best overall performance was achieved when the number of clusters was set to k = 5, yielding an accuracy of 80.21% ± 1.34, F1-score of 79.19% ± 1.56, specificity of 84.19% ± 1.40, sensitivity of 76.14% ± 2.20, and an AUC-ROC of 89.97% ± 1.26. Although the overall performance in the subject-independent setting was lower than that observed in subject-dependent experiments, the relatively small performance variance across different cluster configurations indicates that the proposed model maintains robust generalization capability across unseen subjects.

Table 6 shows a performance comparison between the proposed DML + ANFIS framework and conventional deep learning-based models using STFT-based time–frequency features under a subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation setting. As shown in Table 6, the Bi-LSTM model exhibited the lowest classification performance, achieving an accuracy of 66.68% and an AUC-ROC of 72.45%. The 2D CNN model showed improved performance by exploiting spatial structures in STFT representations, thus achieving an accuracy of 75.41% and an AUC-ROC of 83.38%. The DML + NN model with 256-dimensional embeddings achieved an accuracy of 75.17%, while reducing the embedding dimension to 10 led to improved performance, reaching an accuracy of 76.96% and an AUC-ROC of 78.45%.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of proposed model with traditional deep learning models using STFT time–frequency features under subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation.

In contrast, the proposed DML + ANFIS model consistently outperformed all baseline models. When a fixed temperature parameter (τ = 0.07) was used, the model achieved an accuracy of 77.70% and an AUC-ROC of 85.24%, already surpassing conventional deep learning approaches. By further introducing the adaptive temperature strategy, the DML + ANFIS model achieved the best overall performance, with an accuracy of 80.21% ± 1.34, F1-score of 79.19% ± 1.56, specificity of 84.19% ± 1.40, sensitivity of 76.14% ± 2.20, and an AUC-ROC of 89.97% ± 1.26. These results demonstrate that adaptive temperature-based deep metric learning significantly enhances the quality of low-dimensional embeddings, which are effectively exploited by the ANFIS classifier to construct robust nonlinear decision boundaries. Overall, the proposed DML + ANFIS framework shows superior generalization performance under subject-independent evaluation, thus confirming its effectiveness for practical EEG-based MDD diagnosis.

Table 7 presents a comparison of model complexity between the proposed DML + ANFIS framework and conventional deep learning models in terms of the number of learnable parameters and parameter memory when STFT-based time–frequency features are used. As shown in Table 7, the Bi-LSTM model exhibits the highest complexity, requiring approximately 4.7 million parameters and 17.9 MB of memory. In contrast, the 2D CNN substantially reduces the model size but still requires considerably more parameters than the proposed approach. The DML-based models show a clear reduction in complexity as the embedding dimension decreases. Notably, the proposed DML + ANFIS model with a 10-dimensional embedding requires only approximately 76,360 parameters and 0.291 MB of memory, thus representing a substantial reduction in both computational and memory requirements compared to the Bi-LSTM and 2D CNN models.

Table 7.

Model complexity comparison using STFT-based time–frequency features.

3.3.2. Analysis of DML + ANFIS Model Performance with CWT Time–Frequency Features

The second experiment aimed to evaluate and analyze the diagnostic performance of the DML + ANFIS model for MDD using the CWT-based time–frequency features extracted from the MDD EEG dataset. Table 8 shows the variation in the diagnostic performance of the DML + ANFIS model for MDD according to the number of clusters (k) when using the CWT-based time–frequency feature embeddings as input. As shown in Table 8, the proposed model consistently maintained high accuracy exceeding 97% and an AUC value above 99% across all cluster configurations, thus demonstrating highly stable diagnostic performance.

Table 8.

Performance of DML + ANSFIS model according to number of clusters using CWT time–frequency feature embedding.

Specifically, when the number of clusters was set to k = 2, the model achieved an accuracy of 98.15%, an F1-score of 98.15%, a specificity of 98.14%, a sensitivity of 98.14%, and an AUC-ROC of 99.38%. When the number of clusters increased to k = 3, the model exhibited its highest performance, with an accuracy of 98.41%, F1-score of 98.41%, specificity and sensitivity of 98.40%, and AUC-ROC of 99.50%. This result suggests that at k = 3, the ambiguity of inter-cluster boundaries was minimized, enabling the DML + ANFIS model to establish a well-balanced clustering structure and optimized fuzzy rule learning within the CWT-based feature space. In contrast, when the number of clusters increased beyond k ≥ 4, slight performance degradation was observed. For instance, the model achieved an accuracy of 97.62% at k = 4, and this slightly decreased to 97.97% for k = 5 and k = 6. This decline can be attributed to the increased complexity of fuzzy rules and the deterioration of generalization ability caused by the excessive partitioning of the feature space. Overall, this trend indicates that the DML + ANFIS model achieves optimal performance and stable learning characteristics with a moderate number of clusters (k = 3), even within the CWT-based feature representation.

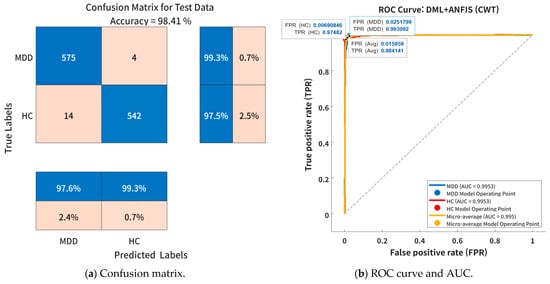

Figure 8 visually illustrates the classification performance of the DML + ANFIS model using CWT-based time–frequency features under the optimal cluster configuration (k = 3). Figure 8a presents the confusion matrix for the test dataset. The proposed DML + ANFIS model (k = 3) correctly classified 99.3% of MDD samples and 97.5% of HC samples. The number of misclassified samples was very small—only 4 for MDD and 14 for HC—indicating that the model effectively captured subtle variations in EEG patterns between the two groups with high discriminative capability. Figure 8b shows the ROC curve and the corresponding AUC for the same model. The ROC analysis revealed a TPR of 0.993 and 0.9748 and an FPR of 0.0257 and 0.0069 for the MDD and HC groups, respectively. The AUC values for both classes were 0.9953, demonstrating near-perfect classification performance. In addition, the micro-average AUC was measured at 0.995, thus confirming that the model maintained excellent overall class separability and precision across categories. These findings suggest that the CWT-based time–frequency features provide a more precise representation of the non-stationary components and frequency fluctuations inherent in EEG signals, enabling the DML + ANFIS model to effectively learn the nonlinear dependencies among these features.

Figure 8.

Classification performance of proposed DML + ANFIS model (k = 3) using CWT-based time–frequency feature embedding: (a) confusion matrix for test dataset, and (b) ROC curve and AUC values for MDD and HC groups.

Due to the adaptive time–frequency resolution of the CWT compared to the STFT, the model was able to more accurately capture the fine-grained spectral variations associated with depression-related EEG activity. Consequently, the DML + ANFIS model utilizing CWT-based features achieved approximately 6% higher average accuracy and 2% higher AUC than the STFT-based model, thus experimentally validating that the integration of DML and ANFIS provides a powerful and robust framework for modeling the complex time–frequency dynamics of EEG signals in major depressive disorder diagnosis.

Table 9 shows a comparative analysis of the diagnostic performance of MDD between the proposed DML + ANFIS model and traditional deep learning-based classification models using CWT-based time–frequency features as input. As shown in Table 9, the proposed DML + ANFIS model consistently outperformed all baseline models across every evaluation metric, thus demonstrating that the CWT-based feature representation effectively captures the complex nonlinear characteristics in EEG signals.

Table 9.

Performance comparison of proposed model with traditional deep learning models using CWT time–frequency features.

The Bi-LSTM model achieved an accuracy and F1-score of 85.87%, with a specificity and sensitivity of 85.88% and an AUC-ROC of 93.70%. The 2D CNN model showed improved performance by exploiting spatial patterns in time–frequency representations, achieving an accuracy of 92.14%, an F1-score of 92.12%, and an AUC-ROC of 97.82%. The DML + NN model demonstrated a clear dependence on embedding dimensionality. When using 256-dimensional embeddings, it achieved strong diagnostic performance with an accuracy of 97.71% and an AUC-ROC of 98.93%. However, reducing the embedding dimension to 10 resulted in a slight performance degradation, with accuracy and AUC-ROC decreasing to 95.86% and 96.03%, respectively, suggesting a minor loss of discriminative information due to dimensionality reduction.

In comparison, the DML + ANFIS model employing a fixed temperature parameter of 0.07 achieved competitive performance, with an accuracy of 97.27% and an AUC-ROC of 98.54%. Notably, introducing the adaptive temperature strategy enabled the proposed DML + ANFIS model (k = 3, 10-dimensional embedding) to achieve the best overall performance, reaching an accuracy and F1-score of 98.41% and an AUC-ROC of 99.50%. This improvement demonstrates that adaptive temperature scaling enhances the discriminative power of low-dimensional embeddings, which are effectively exploited by the neuro-fuzzy inference mechanism to construct robust nonlinear decision boundaries. Overall, the proposed framework achieved approximately 6–12% higher classification accuracy than conventional deep learning models and up to a 2–3% improvement over DML + NN models, thus confirming its effectiveness and computational efficiency for EEG-based MDD diagnosis.

This experiment evaluated the performance of the proposed DML + ANFIS model using CWT-based time–frequency feature embeddings under a subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation setting. Table 10 shows the classification results obtained with different numbers of clusters (k), where 10-dimensional CWT feature embeddings were used as input to the ANFIS classifier.

Table 10.

Performance of DML + ANSFIS model according to number of clusters using CWT time–frequency feature embedding under subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation.

As shown in Table 10, the DML + ANFIS model exhibited stable and consistent classification performance across all cluster configurations, with accuracy values remaining in a narrow range of approximately 82–83%. When k = 2, the model achieved an accuracy of 82.25% and an AUC-ROC of 89.41%. As the number of clusters increased to k = 3, performance slightly improved, reaching an accuracy of 82.79% and an AUC-ROC of 89.37%, which represents the highest overall accuracy among all configurations. For k = 4 and k = 5, the model maintained comparable performance, with accuracies of 82.41% and 82.35%, respectively, and AUC-ROC values consistently around 89.3%. Although sensitivity showed minor fluctuations across different cluster settings, no significant performance degradation was observed. When k was further increased to 6, the model achieved an accuracy of 82.58% and an AUC-ROC of 89.24%, thus indicating that increasing the number of clusters beyond an intermediate range did not yield additional performance gains. Overall, the CWT-based DML + ANFIS model achieved an average accuracy of approximately 82.5% and an AUC-ROC of about 89.3% under subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation.

Table 11 presents a comparative evaluation of MDD classification performance between the proposed DML + ANFIS framework and conventional deep learning-based models using CWT-based time–frequency features under subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation. As shown in the table, the proposed DML + ANFIS model achieved the best overall performance across all evaluation metrics, thus demonstrating its effectiveness in modeling the nonlinear and non-stationary characteristics of EEG signals in a subject-independent setting.

Table 11.

Performance comparison of proposed model with traditional deep learning models using CWT time–frequency features under subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation.

Among the baseline models, Bi-LSTM exhibited limited generalization capability, achieving an accuracy of 61.37% and an AUC-ROC of 66.41%. The 2D CNN improved its performance by exploiting spatial patterns in time–frequency representations, reaching an accuracy of 75.88% and an AUC-ROC of 83.08%. The DML + NN model benefited from metric-based feature embedding, achieving accuracies of 74.78% and 79.49% with 256- and 10-dimensional embeddings, respectively, indicating that low-dimensional embeddings can retain discriminative information while improving efficiency.

In contrast, the DML + ANFIS model with a fixed temperature setting (τ = 0.07) achieved an accuracy of 79.48% and an AUC-ROC of 86.38%, thus suggesting that a single global temperature is insufficient to accommodate varying sample difficulty across subjects. By introducing the adaptive temperature strategy, the proposed DML + ANFIS model (k = 3, 10-dimensional embedding) achieved the best overall performance, with an accuracy of 82.79%, an F1-score of 82.01%, and an AUC-ROC of 89.37%. These results demonstrate that adaptive temperature scaling significantly enhances the stability and discriminative capability of metric learning, producing compact yet informative embeddings that are effectively leveraged by the neuro-fuzzy inference mechanism to construct robust nonlinear decision boundaries.

Table 12 presents a comparison of model complexity in terms of the number of learnable parameters and parameter memory for different deep learning-based classifiers using CWT-based time–frequency features. The Bi-LSTM model shows the highest complexity, requiring approximately 2.1 million parameters and 8.0 MB of memory. Although the 2D CNN significantly reduces complexity, it still requires over 160k parameters. In contrast, models incorporating deep metric learning (DML) achieve substantial reductions in model size by compressing high-dimensional features into compact embeddings. Notably, the proposed DML + ANFIS model with a 10-dimensional embedding requires only about 62,656 parameters and 0.239 MB of memory, thus representing the lowest complexity among all compared models. These results demonstrate that the proposed DML + ANFIS framework achieves high parameter efficiency, thereby allowing for accurate MDD diagnosis while requiring minimal computational cost and memory resources.

Table 12.

Model complexity comparison using CWT-based time–frequency features.

4. Discussion

In this study, we proposed a hybrid DML + ANFIS framework for EEG-based major depressive disorder (MDD) classification and evaluated its performance using time–frequency representations derived from the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) and continuous wavelet transform (CWT). The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed framework generally outperformed conventional deep learning-based classifiers, including Bi-LSTM, 2D CNN, and DML + NN, when evaluated under identical preprocessing and validation conditions. In particular, the CWT-based DML + ANFIS model achieved comparatively higher performance, thus suggesting that multi-resolution time–frequency analysis is effective for capturing the non-stationary and transient characteristics of EEG signals associated with MDD.

A key contribution of the proposed framework lies in the integration of deep metric learning and neuro-fuzzy inference. The DML module compressed high-dimensional time–frequency features (1280 dimensions) into compact 10-dimensional embeddings, achieving substantial dimensionality reduction while preserving discriminative information. This compact representation not only improves computational efficiency but also limits model complexity. Compared with neural network classifiers operating on the same embeddings, the ANFIS classifier generally yielded improved performance, indicating that fuzzy rule-based nonlinear decision boundaries are well suited for exploiting low-dimensional metric embeddings. In addition, the DML module incorporates an adaptive temperature mechanism within the contrastive learning objective. Ablation experiments showed that the adaptive temperature strategy provided consistent performance improvements compared with a fixed-temperature setting. This result suggests that dynamically adjusting the contrastive margin during training can contribute to more stable and discriminative representation learning, particularly under limited data conditions, without increasing model complexity.

To assess generalization performance in a more realistic setting, additional experiments were conducted using a strict subject-independent 5-fold cross-validation protocol. As expected, overall performance decreased compared with subject-dependent evaluation, reflecting the challenge of inter-subject variability in EEG signals. Nevertheless, the proposed DML + ANFIS framework generally outperformed baseline models under subject-independent validation for both STFT- and CWT-based features, indicating that the learned embeddings and fuzzy inference structure retain discriminative capability when applied to unseen subjects.

Despite these findings, several limitations should be considered. First, due to the scarcity of publicly available EEG datasets for MDD, this study relied on a single dataset, which restricts external generalizability. Although subject-independent cross-validation protocols were employed to mitigate overfitting, the absence of validation on an independent cohort remains a limitation. Second, the healthy control (HC) group exhibited demographic imbalance, particularly with respect to sex distribution, which may introduce potential confounding effects given the known sex-related differences in EEG characteristics and depression prevalence. While subject-independent validation reduces subject-specific bias, sex-related confounding cannot be completely ruled out. Additionally, no power analysis or resampling strategies were employed, as the dataset composition was fixed. Furthermore, although recent state-of-the-art models such as transformer-based or graph-based architectures have been reported in the literature, direct performance comparison with these methods was not conducted, as they are often evaluated using different datasets, preprocessing pipelines, and validation protocols, thus making fair comparison under identical experimental conditions challenging. Finally, although the ANFIS is inherently rule-based, the present study does not include a detailed analysis of the learned fuzzy rules or membership functions. In this work, the ANFIS was primarily used as a structured nonlinear inference module operating on compact DML embeddings, and detailed rule-level interpretability is left for future investigation. These factors should be considered when interpreting the reported performance.

Overall, the results suggest that the proposed DML + ANFIS framework provides a balanced trade-off between classification performance, generalization capability, and computational efficiency. The combination of compact metric embeddings, adaptive contrastive learning, and neuro-fuzzy inference may serve as a potential methodological foundation for future EEG-based psychiatric disorder analysis, particularly under limited data conditions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a DML + ANFIS model that fuses deep metric learning (DML) with an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) for the diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). The proposed model was trained using time–frequency features extracted from EEG signals via the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) and continuous wavelet transform (CWT). Under subject-dependent evaluation, the proposed framework demonstrated superior diagnostic performance compared to conventional deep learning architectures, including Bi-LSTM, 2D CNN, and DML + NN. In particular, the CWT-based DML + ANFIS model achieved an accuracy of 98.41% and an AUC of 99.50%. To further assess generalization capability, additional experiments were conducted using a subject-independent validation protocol. Although overall performance decreased under this more challenging setting, the proposed DML + ANFIS model consistently outperformed baseline models for both STFT- and CWT-based features. The DML module reduced the original 1280-dimensional EEG features into a compact 10-dimensional embedding, thus achieving approximately 128× data compression while preserving essential discriminative information. This dimensionality reduction improves computational efficiency and limits model complexity. In addition, the incorporation of an adaptive temperature mechanism within the contrastive learning objective contributed to more stable representation learning, as confirmed by ablation experiments, particularly under limited data conditions. The ANFIS classifier further modeled nonlinear decision boundaries in the low-dimensional embedding space, thus enabling the effective exploitation of complex spectral–temporal interactions captured by the DML embeddings. In conclusion, the proposed framework provides an efficient combination of compact metric embeddings and neuro-fuzzy inference for EEG-based MDD classification. While the results indicate competitive performance and improved parameter efficiency, this study is limited by the size of the dataset and the diversity of available clinical variables. Future work will focus on validating the proposed framework using larger and more diverse EEG datasets, including independent cohorts, to further assess generalization capability. In addition, extensions to multimodal physiological data and interpretable modeling approaches will be explored to enhance robustness and transparency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-H.J. and K.-C.K.; Methodology, A.-H.J. and K.-C.K.; Software, A.-H.J. and K.-C.K.; Validation, A.-H.J. and K.-C.K.; Formal Analysis, A.-H.J. and K.-C.K.; Investigation, A.-H.J.; Resources, K.-C.K.; Data Curation, K.-C.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.-H.J.; Writing—Review and Editing, K.-C.K.; Visualization, A.-H.J. and K.-C.K.; Supervision, K.-C.K.; Project Administration, K.-C.K.; Funding Acquisition, K.-C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and funded by the Ministry of Education (No. 2017R1A6A1A03015496). This research was also supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Gwangju RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and Gwangju Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-05-013).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available in a publicly accessible repository [35,36].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO Depression. Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Otte, C.; Gold, S.M.; Penninx, B.W.; Pariante, C.M.; Etkin, A.; Fava, M.; Mohr, D.C.; Schatzberg, A.F. Major depressive disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.S.; Sarvet, A.L.; Meyers, J.L.; Saha, T.D.; Ruan, W.J.; Stohl, M.; Grant, B.F. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.M.; Adams, M.J.; Shirali, M.; Clarke, T.-K.; Marioni, R.E.; Davies, G.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Alloza, C.; Shen, X.; Barbu, M.C.; et al. Genome-wide association study of depression phenotypes in UK Biobank identifies variants in excitatory synaptic pathways. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remes, O.; Mendes, J.F.; Templeton, P. Biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression: A review of re-cent literature. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major depressive disorder: Hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Beck Depression Inventory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, D.; Pulice, R.F.; Reilly, J.; Brunoni, A.R.; Kapczinski, F.; Passos, I.C. Predicting treatment response using EEG in major depressive disorder: A machine-learning meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiei, A.; Zahedifar, R.; Sitaula, C.; Marzbanrad, F. Automated Detection of Major Depressive Disorder With EEG Signals: A Time Series Classification Using Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 73804–73817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashempour, S.; Boostani, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Sanei, S. Continuous Scoring of Depression From EEG Signals via a Hybrid of Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherzadeh, S.; Maghooli, K.; Shalbaf, A.; Maghsoudi, A. A hybrid EEG-based emotion recognition approach using wavelet convolutional neural networks and support vector machine. Basic Clin. Neurosci. J. 2023, 14, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X. An End-to-End Deep Learning Model for EEG-Based Major Depressive Disorder Classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 41337–41347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, H.; Li, S.; Luo, B.; Li, T.; Pan, G. DiffMDD: A Diffusion-Based Deep Learning Framework for MDD Diagnosis Using EEG. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2024, 32, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Sun, M.; Dong, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liao, X.-F.; Li, Y. A Multiview Sparse Dynamic Graph Convolution-Based Region-Attention Feature Fusion Network for Major Depressive Disorder Detection. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowli, V.P.; Padole, H.P. Detection of Major Depressive Disorder Using EEG Multifeature Fusion. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Ahmad, J.; Alasbali, N.; Saidani, O.; Hanif, M.; Khattak, A.A.; Khan, M.S. Decentralized EEG-based detection of major depressive disorder via transformer architectures and split learning. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1569828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Krishnan, S. Trends in EEG signal feature extraction applications. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 1072801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, D. Theory of communication. Part 1: The analysis of information. J. Inst. Electr. Eng.-Part III Radio Commun. Eng. 1946, 93, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, A.; Morlet, J. Decomposition of Hardy functions into square integrable wavelets of constant shape. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1984, 15, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Saif-Ur-Rehman, M.; Dyck, S.; Glasmachers, T.; Iossifidis, I.; Klaes, C. Enhancing the decoding accuracy of EEG signals by the introduction of anchored-STFT and adversarial data augmentation method. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Kwak, K.C. Personal identification using an ensemble approach of 1D-LSTM and 2D-CNN with electrocardiogram signals. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, R.; Hu, H.; Gao, Y.; Xia, W.; Song, B. Automatic Sleep Staging Method Using EEG Based on STFT and Residual Network. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dişli, F.; Gedikpınar, M.; Fırat, H.; Şengür, A.; Güldemir, H.; Koundal, D. Epilepsy diagnosis from EEG signals using continuous wavelet Transform-Based depthwise convolutional neural network model. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilly, J.M.; Olhede, S.C. Higher-Order Properties of Analytic Wavelets. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2009, 57, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammone, N.; Ieracitano, C.; Morabito, F.C. A deep CNN approach to decode motor preparation of upper limbs from time–frequency maps of EEG signals at source level. Neural Netw. 2020, 124, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daubechies, I. Ten Lectures on Wavelets; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Merchan, F.; Contreras, K.; Gittens, R.A.; Loaiza, J.R.; Sanchez-Galan, J.E. Deep metric learning for the classification of MALDI-TOF spectral signatures from multiple species of neotropical disease vectors. Artif. Intell. Life Sci. 2023, 3, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.D.; Jawade, B.; Setlur, S.; Govindaraju, V. Deep metric learning for computer vision: A brief overview. Handb. Stat. 2023, 48, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Vienna, Austria, 13–18 July 2020; PmLR: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Volume 119, pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.-S.R. ANFIS: Adaptive–network–based fuzzy inference systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1993, 23, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, C.U.; Kwak, K.C. Performance comparison of ANFIS models by input space partitioning methods. Symmetry 2018, 10, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Kwak, K.C. Hybrid Deep-ANFN Model for Dimensionality Reduction and Classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 171743–171752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, T.W.; Kwak, K.C. Speaker Recognition Based on the Combination of SincNet and Neuro-Fuzzy for Intelligent Home Service Robots. Electronics 2025, 14, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, W. MDD Patients and Healthy Controls EEG Data (New); Dataset; Figshare: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, W.; Xia, L.; Yasin, M.A.M.; Ali, S.S.A.; Malik, A.S. A wavelet-based technique to predict treatment outcome for major depressive disorder. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.