Abstract

Motor recovery after stroke is highly variable and closely linked to the extent of corticospinal tract (CST) damage. Neurophysiological biomarkers, such as motor evoked potentials (MEPs) and structural imaging markers, including CST lesion load and fractional anisotropy (FA), show promise for predicting motor outcomes. This scoping review evaluated the prognostic value of these biomarkers and the utility of multimodal models for individualized rehabilitation. A systematic search (April 2024) in PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and Scopus identified empirical studies examining biomarkers predictive of post-stroke motor recovery. Biomarkers were primarily derived from magnetic resonance imaging (resting-state functional connectivity and diffusion-weighted imaging) and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Nineteen studies (1219 patients) met the inclusion criteria. Structural biomarkers, particularly lower CST FA and higher weighted lesion load, were generally associated with poorer motor recovery. Combining neurophysiological measures, such as MEP status, with functional imaging and artificial intelligence-based analyses may improve prognostic precision. Multimodal approaches appeared promising in some studies, but evidence remains limited and heterogeneous. Integrating diverse biomarkers into multimodal prognostic models may enhance the prediction of motor recovery and support personalized rehabilitation after stroke, although heterogeneity in study design and outcome assessment highlights the need for standardized, large-scale longitudinal studies to enable clinical implementation.

1. Introduction

Stroke remains a leading cause of disability worldwide and accounted for approximately 10% of global deaths in 2021, ranking as the third leading cause of mortality after ischemic heart disease and COVID-19 [1]. Despite an average annual decline of 2.8% in stroke-related mortality in the United States between 1975 and 2019, the burden on healthcare systems is expected to increase [2]. This is further supported by projections of a 27% rise in stroke survival across the European Union by 2047 [3]. This is largely due to the persistent and debilitating consequences of stroke, particularly motor and cognitive impairments, which substantially reduce patients’ quality of life and increase dependency [4,5].

Effective motor rehabilitation is crucial for restoring functional independence [6]. However, the heterogeneity of stroke pathology leads to substantial variability in recovery outcomes. Consistent with this, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of upper-limb recovery under usual care reported clinically meaningful improvements in the subacute phase, while highlighting baseline severity and corticospinal tract lesion load as factors associated with recovery [7]. Standard clinical tools, such as the Fugl–Meyer Assessment (FMA) and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), provide initial prognostic value. This is clinically relevant because motor recovery is typically most pronounced within the first months after a stroke, and initial motor impairment is a major determinant of subsequent outcomes [8]. However, they are less accurate for patients whose recovery trajectories deviate from expected patterns (“non-fitters”), compared with “fitters” who follow the proportional recovery rule [9,10,11]. In 2012, Coupar et al. synthesized evidence on predictors of upper-limb motor recovery after stroke across demographic, clinical, lesion-related, and neurophysiological factors [12]. They identified baseline upper-limb impairment and motor evoked potentials among the most consistently supported predictors, while noting substantial heterogeneity across studies. Since then, prognostic research has increasingly shifted toward biomarkers that more directly capture the neural substrates of motor recovery, alongside newer prediction approaches.

In this context, recent research has focused on identifying biomarkers that reflect the biological substrates underlying motor recovery and enable more personalized rehabilitation strategies. A key neuroanatomical substrate implicated in post-stroke motor recovery is the corticospinal tract (CST), which serves as the principal conduit between the primary motor cortex and spinal motor neurons [13,14]. CST integrity is essential for voluntary motor control, particularly of distal muscles [15,16]. Post-stroke damage to the CST is a major determinant of motor deficits. The extent of CST degeneration, quantified using imaging modalities such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has been associated with differential recovery outcomes [14]. Similar associations have been reported for functional assessments, including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and electroencephalography (EEG) [17]. For instance, patients with mild CST injury may regain up to 70% of upper limb function, whereas those with severe injury often recover less than 30% [17].

Structural and functional biomarkers, including lesion size, fractional anisotropy (FA) asymmetry, and the presence of motor evoked potentials (MEPs), have been linked to recovery trajectories in both fitters and non-fitters [18,19,20]. Additional predictors such as CST involvement on diffusion-weighted imaging, interhemispheric functional connectivity, and MEP status further enhance prognostic accuracy [21,22]. MRI-derived measures of CST damage do not consistently outperform baseline clinical assessments such as the FMA [23]. However, advanced markers, such as weighted CST lesion load (wCST-LL), and multimodal biomarker approaches may improve prognostic precision, although their generalizability requires further validation [24,25].

Mapping the landscape of post-stroke biomarkers and their relationship to motor outcomes may support improved patient stratification and the development of individualized rehabilitation strategies. Therefore, this scoping review aims to synthesize current evidence on structural and functional biomarkers associated with motor recovery following CST damage in stroke, with particular emphasis on neurophysiological and neuroimaging-based predictors of outcome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was conducted as a scoping review following the guidelines in the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis and best practices recommended by Peters et al. (2022) [26,27]. In addition, the review was reported in accordance with the PRISMA-Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) by Tricco et al. (2018) [28]. The review protocol was registered a priori on the Open Science Framework (OSF) and is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DSEH4 (accessed on 25 December 2025). The PRISMA checklist can be found in Supplementary File S1.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were formulated using the Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework [26,27]. Studies were required to investigate imaging or neurophysiological biomarkers associated with motor outcomes following post-stroke CST damage. Eligible studies included adults (≥18 years) with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, regardless of etiology or clinical complications, provided that CST damage was assessed and linked to motor outcomes; studies in pediatric populations or non-stroke conditions were excluded. Biomarkers of interest included conventional structural MRI sequences (T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and FLAIR) used for lesion delineation, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) for ischemic lesions and tract integrity, susceptibility-based sequences (GRE/SWI) for hemorrhagic lesions, and rs-fMRI–derived resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC). We also considered computed tomography (CT), EEG, and TMS. Studies were required to report at least one validated motor outcome measure (upper and/or lower extremity impairment, function, or activity). Studies were excluded if they did not report motor outcomes (for example, imaging-only endpoints, cognition, mood, or other non-motor outcomes), which were classified as “incorrect outcomes” during full-text screening. Study designs considered included randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and longitudinal designs. Non-English language publications, case reports, commentaries, editorials, and conference abstracts were excluded.

2.3. Search Strategy and Screening Process

A comprehensive search was conducted in April 2024 across PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Scopus databases, guided by the PCC framework. The initial search terms were developed by an experienced researcher and refined through pilot searches and team discussions. Included studies comprised quantitative experimental, descriptive, correlational, and longitudinal designs aligned with the PCC criteria. Both confirmatory (hypothesis-driven) and exploratory analyses were eligible, including analyses conducted in primary studies and secondary analyses of existing datasets. Text and opinion publications (e.g., editorials, commentaries, perspectives) and letters were excluded because they generally lack empirical data and, therefore, do not address the objectives of this review. Detailed search strategies for all databases are provided in Supplementary File S2.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by four reviewers (P.B., R.A.L., T.C., and D.G.) using Rayyan software (www.rayyan.ai) [29]. Full-text screening and data extraction were conducted by two independent reviewers per record, with the four reviewers working in two pairs and each pair assessing a predefined subset of studies. In cases of disagreement regarding study selection or data extraction within a reviewer pair, B.C. was consulted as an adjudicating reviewer to reach consensus.

2.4. Data Extraction

From each included study, the following data were extracted: authors’ names, year of publication, sample characteristics, and key findings relevant to the review questions. Data were compiled in an extraction table for subsequent analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

The initial search yielded 294 articles from PubMed, 329 from Scopus, and 124 from the Cochrane Library. After removing duplicates, 413 articles remained for abstract screening, which was conducted independently by four authors. Of these, 94 articles proceeded to full-text review, and ultimately 19 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

In total, the 19 studies enrolled 1219 patients (Table 1). Sixty-three participants were explicitly reported as having hemorrhagic stroke (two studies); in the remaining studies, stroke type was ischemic or not reported. Most studies did not specify the treatment regimen provided to participants (whether pharmacological or physical therapy). Three studies conducted regular physiotherapy, one included combined physical and occupational therapy.

Table 1.

Overview of neurophysiological and neuroimaging biomarkers.

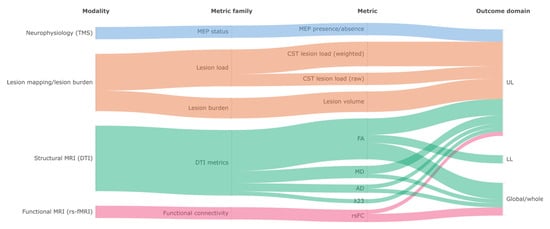

To provide an overview of how biomarkers were operationalized across included studies, we visualized the relationships between modality (e.g., TMS, structural MRI, rs-fMRI), metric family, specific metrics, and the motor outcome domain (upper limb, lower limb, or global/whole) using an alluvial diagram (Figure 2). The figure includes only biomarkers (specific metrics) reported in at least two studies. The diagram highlights the predominance of structural MRI (DTI) metrics, particularly fractional anisotropy, and lesion-based measures (including CST lesion load), and shows how these metrics were distributed across outcome domains.

Figure 2.

Alluvial diagram mapping biomarker modality, metric family, and specific metrics to motor outcome domain across included studies. Band widths are proportional to the number of studies contributing to each link; biomarkers reported in only one study are not displayed. TMS: transcranial magnetic stimulation; MEP: motor evoked potential; CST: corticospinal tract; rλ23: transverse diffusivity ratio; DTI: diffusion tensor imaging; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; rs-fMRI: resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging; FA: fractional anisotropy; MD: mean diffusivity; AD: axial diffusivity; rsFC: resting-state functional connectivity; UL: upper limb; LL: lower limb.

3.3. Motor Outcomes and Prediction

3.3.1. Neurophysiological Predictors (TMS and MEPs)

Two studies evaluated the predictive value of neurophysiological biomarkers, including TMS and MEPs, for motor recovery post-stroke. Yen et al. (2023) [30] reported that, in patients with moderate-to-severe impairment (baseline FMA ≤ 38), MEP+ status was associated with higher FMA at 30 days and 90 days (Wald χ2 = 9.13 and 4.09, respectively, p < 0.05), and higher proportional recovery at 30 days and 90 days (Wald χ2 = 13.90, p < 0.001, and 7.84, p < 0.05). At 90 days, a good functional outcome (modified Rankin Scale ≤ 1) was more frequent in MEP+ vs. MEP−, but this did not reach statistical significance after age adjustment (OR = 9.08, 95%, p = 0.059). In milder cases (baseline FMA > 38), all patients were MEP+, limiting the discriminative value of MEP status [30].

Hayward et al. (2017) similarly found that MEP presence was the only neurophysiological biomarker consistently associated with better upper-limb motor outcome (t = 3.32, p < 0.01) [31]. A significant MEP-by-recording-location interaction was also observed (t = −2.64, p = 0.01), with a larger FM-UL difference between MEP+ and MEP− when MEPs were recorded from the forearm (vs. hand). By contrast, the CST asymmetry index (FA-based interhemispheric CST asymmetry) showed no meaningful association with recovery (t = 0.05, p = 0.96).

3.3.2. White Matter Integrity and Functional Connectivity Predictors

Elameer et al. (2023) found that FA in the centrum semiovale (r = 0.457, p = 0.016) and FA in the cerebral peduncle (r = 0.423, p = 0.032) correlated with lower limb recovery, while muscle volume showed mixed effects on clinical improvement [32]. Vastus lateralis fat fraction negatively correlated with NIHSS recovery (r = −0.401, p = 0.04), suggesting impaired recovery with greater muscle degeneration. Combining brain and muscle biomarkers did not enhance predictive accuracy.

Xia et al. (2021) demonstrated that early interhemispheric rsFC restoration (weeks 1–4) correlated with motor improvement (r = 0.695, p < 0.001), but from weeks 4 to 12, only ipsilesional CST FA remained predictive (β = 0.557, p = 0.001) [33]. Higher initial FA was linked to better recovery trajectories, whereas contralesional CST FA was not associated with outcomes.

Puig et al. (2019) identified posterior limb of the internal capsule (PLIC) involvement by intracerebral hemorrhage within the first 12 h as a significant predictor of poor motor outcome at 3 months (Odds Ratio, OR = 10.80; p = 0.002) [34]. Quantitative DTI measures (including FA-derived ratios) did not influence outcome or add predictive value beyond clinical scores. The best-performing model combined 72 h modified NIHSS with PLIC involvement, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) = 0.94 (95% CI 0.86–1.00), sensitivity = 92%, and specificity = 86%.

Liu et al. (2018) reported that larger lesion volumes predicted poor recovery (18.6 mL vs. 3.5 mL, p < 0.001), with lesion volume as the sole predictor in severely impaired patients (ρ = −0.950, p < 0.001) [35]. In contrast, initial FMA-UE (week 1) predicted recovery only in proportional recoverers (R2 = 0.983, p < 0.001). Axial diffusivity (AD) changes in M1 correlated with motor improvement in all patients (R2 = 0.417, p = 0.002).

Liu et al. (2017) reported that patients with poor recovery had lower local diffusion homogeneity (LDH) at 1 week in the ipsilesional CST, mainly within the superior corona radiata (SCR) and PLIC (p < 0.005) [36]. LDH in the CST region of interest correlated with 12-week motor status (Spearman ρ = 0.74, p < 0.01) and with proportional-recovery model residuals (ρ = −0.66, p < 0.01), with these associations remaining significant after adjustment (ρ = 0.56, p < 0.01; ρ = −0.53, p < 0.01). In multivariate logistic regression, initial FMA and CST LDH jointly predicted recovery group (G = 47.22, p < 0.01), and leave-one-out cross-validation showed accuracy = 0.82. By contrast, FA did not differentiate recovery groups in the acute phase.

Liu et al. (2015) observed progressive FA reductions in the ipsilesional CST (M1 and pons) between weeks 4 and 12, while contralesional FA increases in the medial frontal gyrus (MFG) and thalamocortical pathways correlated with motor recovery (MFG: F = 10.68, p = 0.0045; thalamocortical: F = 13.58, p = 0.0018) [37]. Contralesional CST FA remained unchanged, suggesting plasticity in non-motor pathways.

Song et al. (2012) found that in chronic stroke patients, those with complete hand paralysis had lower rFA and rλ23 in the CST (p < 0.001 and p = 0.015, respectively) [38]. rMD and rλ23 also distinguished complete vs. partial paralysis (p = 0.014, p = 0.016). rλ23 correlated with NIHSS (r = −0.489, p = 0.029) and rMD with FMA-hand (r = −0.512, p = 0.021), suggesting potential biomarker utility.

3.3.3. Structural Biomarkers of Recovery (Lesion Load, CST Integrity and White Matter Measures)

Liu et al. (2020) demonstrated that damage to CST fibers from M1 and SMA correlated with chronic motor deficits (M1: r = 0.454, p < 0.001; SMA: r = 0.333, p < 0.001) [39]. Voxel-based lesion symptom mapping (VLSM) identified that acute lesions in the left M1 fibers and right CST fibers predicted worse long-term outcomes. Early M1 fiber damage was negatively correlated with motor recovery (r = −0.481, p < 0.001), while SMA damage was linked to reduced contralateral cerebellar volume (r = −0.492, p < 0.001), suggesting broader structural reorganization effects.

Lin et al. (2019) found that CST injury explained 20% of the variance in upper extremity motor recovery (R2 = 0.18–0.25, p < 0.01) at 90 days, even when controlling for initial severity [40]. Four CST injury estimation methods (max overlap, raw lesion load, weighted lesion load, and 16-division method) yielded comparable results. CST injury distinguished proportional from limited recoverers (AUC = 0.70–0.80), while structural injury to M1 and PMC did not significantly alter prediction accuracy.

Plantin et al. (2019) highlighted the association between early severe spasticity and poor motor recovery, with spasticity prevalence increasing from 33% at 3 weeks to 51% at 6 months [41]. Severe spasticity was linked to significant passive range of motion loss (25° reduction at 6 months) and increased arm pain. wCST-LL correlated with spasticity severity both early and chronically (T1: R = 0.49, p = 0.0004; T3: R = 0.61, p < 0.0001). VLSM identified lesions in white matter beneath the hand knob as predictors of spasticity onset.

Feng et al. (2015) found that both wCST-LL and FM-UE strongly correlated with 3-month motor outcomes (R2 = 0.69 vs. 0.67, p = 0.43) [24]. In severely impaired patients (FM-UE ≤ 10 at baseline), wCST-LL outperformed FM-UE in predicting recovery (R2 = 0.47 vs. 0.11, p = 0.03). Patients with wCST-LL ≥ 7.0 cc had poor motor outcomes (FM-UE ≤ 25) at 3 months, with 100% positive predictive value. While NIHSS arm scores at 3 months were similarly predicted by wCST-LL and initial NIHSS (R2 = 0.58 vs. 0.55, p = 0.39), wCST-LL was not a strong predictor of global functional outcomes (NIHSS total score: R2 = 0.45).

Zhu et al. (2010) confirmed that weighted CST lesion load was the strongest independent predictor of motor impairment (adjusted R2 = 0.727, p < 0.001), outperforming lesion size alone, which was a weaker predictor (R2 = 0.307, p < 0.001) [42]. Raw and weighted CST lesion load strongly correlated with motor impairment (R2 = 0.664 and 0.724, p < 0.001). VLSM confirmed that CST damage, rather than total lesion size, determined motor deficits.

3.3.4. Multimodal Studies

Birchenall et al. (2019) found that patients with smaller CST lesion loads and near-complete recovery of CST excitability (MEPs) had better hand motor recovery (FM-UE hand scores) [43]. However, fine dexterity impairments (finger tapping rate, independence of finger movements) persisted in all patients at six months, despite improvements in gross hand function. The two patients with the poorest recovery showed persistent MEP absence and the largest CST lesions, reinforcing the role of CST excitability in motor recovery.

Liu et al. (2022) demonstrated that acute-stage FA of M1 fibers was the strongest predictor of long-term motor recovery (r = 0.562, p < 0.001), while FA in PMC, S1, and SMA fibers did not show significant associations with outcomes [22]. In the subacute stage, M1–M1 rsFC increased, correlating negatively with FA decline in M1 and SMA fibers (r = −0.415, p = 0.005), suggesting functional reorganization to compensate for CST damage.

Lee et al. (2021) examined early (2 weeks post-stroke) clinical and imaging factors as predictors of 3-month change in motor function for the upper extremity (UE) and lower extremity (LE) using bivariate linear regression [44]. UE recovery was associated with CST lesion load (R2 = 0.233, p < 0.001), lesion volume (R2 = 0.086, p = 0.033), ipsilesional CST FA (R2 = 0.260, p < 0.001), and interhemispheric rsFC (R2 = 0.111, p = 0.018), whereas LE recovery was associated with ipsilesional CST FA (R2 = 0.174, p = 0.004), contralesional CST FA (R2 = 0.100, p = 0.026), and MMSE (R2 = 0.082, p = 0.0365) [44]. Contralesional CST FA was more relevant for LE recovery, while CST lesion load and lesion volume were stronger predictors for UE recovery. In addition, a cognitive–motor difference factor (normalized difference between early MMSE and FMA) emerged as a robust predictor of LE motor recovery (R2 = 0.243), underscoring the prognostic value of preserved cognitive capacity relative to initial motor impairment for lower-limb gains.

Du et al. (2018) demonstrated that baseline motor task-based fMRI (BOLD activation during an affected-hand finger-tapping task) activation in SMA and ipsilesional M1 correlated significantly with better motor recovery (M1: r = 0.466, p = 0.005; SMA: r = 0.488, p = 0.003) [45]. Incorporating fMRI measures into clinical models significantly improved motor outcome prediction (Adj R2 = 0.736, p < 0.001), while structural MRI measures (FA asymmetry, infarct volume) did not add predictive value. Increased activation in ipsilesional M1 at 3 months correlated with functional improvement, reinforcing the importance of early functional reorganization.

Moon et al. (2022) applied AI-based prognostic modeling, finding that automated weighted lesion load correlated strongly with baseline (R2 = 0.784, p < 0.0001) and 90-day NIHSS (R2 = 0.875, p < 0.0001), confirming its predictive utility for global impairment [46]. Lesion load also significantly predicted 90-day FMA (R2 = 0.570, p < 0.0001), though its correlation with motor-specific recovery was weaker. A constrained quintic polynomial regression model outperformed linear regression, improving predictive accuracy.

3.4. Variability in Study Designs

The methodological heterogeneity across studies complicates direct comparisons of findings. Most investigations evaluated outcomes at approximately 3 months or 90 days post-stroke [24,32,34,44,45,46], while others followed different timelines, such as 12-week intervals [33,35] or assessments spanning up to 6 months [22,30,43]. Some studies incorporated multiple checkpoints, such as 30 and 90 days [30], or more frequent follow-ups at 7 days, 1, 3, and 6 months [22], while others used a 2-, 3-, and 6-month framework [43]. Additionally, Liu et al. (2020) related acute-stage DWI-based CST fiber damage to motor outcome assessed in the chronic stage (WE-FM) in patients with subcortical stroke [39].

Differences also emerged in the frequency and type of rehabilitation protocols. While most studies did not specify the treatment regimens provided to participants, three conducted standard physiotherapy [40,42,45], one incorporated combined physical and occupational therapy [24], and one integrated acupuncture-based rehabilitation with inpatient and outpatient therapy [33].

Patient demographics varied considerably across studies. For instance, Birchenall et al. (2019) included only male participants [43], while Lee et al. (2021) reported a 50% female sample [44]. The proportion of patients with hemorrhagic stroke was also inconsistent; only 63 patients across two studies had hemorrhagic stroke [34,41], while the remaining studies either focused exclusively on ischemic stroke or did not specify stroke type [31,38,39]. These variations in follow-up timing, rehabilitation exposure, and patient characteristics highlight the complexity of generalizing findings across different cohorts.

4. Discussion

In this scoping review, we explore the predictive value of biomarkers and the effect of lesion size on motor recovery in post-stroke patients with CST damage. MEPs provide a clinically accessible index of corticospinal excitability and effective corticospinal conduction. The presence of MEPs indicates that key motor pathways remain at least partially intact, a factor that is critical in the context of post-stroke recovery. In patients with moderate-to-severe impairments, studies have consistently shown that those who are MEP+ tend to exhibit significantly better motor recovery, as evidenced by higher FMA scores at both early and later time points. This suggests that the integrity of the corticospinal tract, as reflected by MEPs, serves as a robust biomarker for predicting the potential for motor improvement.

Furthermore, the prognostic value of MEPs is most significant in patients with substantial initial impairment; in milder cases, where most patients are MEP positive, the measure loses its discriminatory power, underscoring the need for patient stratification. For example, Birchenall et al. (2019) found that patients with smaller CST lesion loads and near-complete CST excitability recovery showed better hand motor recovery (FM-UE hand scores), although fine dexterity remained impaired at six months [43]. Notably, the two patients with the poorest recovery had a persistent absence of MEPs and the largest CST lesions. These findings suggest that TMS and MEP evaluations are powerful tools for assessing motor pathway function. Some studies used these measures alongside structural markers (e.g., lesion load) and clinical scales, but the incremental gain in prediction accuracy from combining indicators was not consistently quantified across studies.

Neuroimaging biomarkers, particularly FA and rsFC, could play a role in predicting post-stroke motor recovery. Higher FA in the CST is generally associated with better outcomes, while reductions in FA within the CST and PLIC are linked to poorer recovery [32,33,34]. Interhemispheric rsFC appears relevant in the early phase but tends to stabilize after approximately four weeks, with contralesional white matter plasticity potentially supporting further improvement [33,37]. FA in M1 fibers has been proposed as a marker of CST integrity and long-term motor recovery, and compensatory M1–M1 rsFC changes may reflect functional reorganization [22]. Limb-specific patterns have also been reported, with contralesional CST FA more relevant for lower-limb improvement, and lesion load plus ipsilesional CST FA stronger predictors of upper-limb function [44]. Task-based fMRI further suggests that ipsilesional M1 and SMA activation is associated with better outcomes, supporting structural–functional interactions in recovery [45]. However, the evidence was not uniform, and FA did not always discriminate recovery groups or add predictive value beyond clinical models [34,36], while rsFC effects appeared phase-dependent across follow-up windows [33]. Muscle MRI markers showed variable associations, and combining brain and muscle biomarkers did not appear to enhance prediction [32].

Other diffusion and functional measures (LDH, AD, rλ23, rMD) may provide additional insights, particularly within the CST and motor areas [35,36,38]. Baseline fMRI activation in M1 and SMA has been shown to improve motor outcome predictions beyond FA alone, suggesting that integrating functional imaging could enhance prognostic accuracy [45].

CST integrity plays an important role in motor recovery, with greater damage to CST fibers from M1 and SMA linked to poorer outcomes [39]. Early M1 fiber damage shows a negative association with recovery [39], and CST injury accounts for a moderate proportion of the variance in upper limb motor improvement [40]. wCST-LL is consistently associated with motor impairment, with higher lesion loads predicting weaker recovery, though lesion size alone is a less reliable indicator [42,43]. CST damage is also related to spasticity severity, as greater wCST-LL correlates with increased spasticity over time, and lesions in the white matter beneath the hand knob are linked to its onset [41].

4.1. Clinical Implications

Neurophysiological and imaging biomarkers show strong prognostic value. MEPs predict better outcomes in moderate-to-severe stroke, while FA in the CST correlates with improved recovery. Structural measures like wCST-LL, lesion volume, and VLSM may improve prognostic performance in some models.

Despite their potential, biomarkers have limitations in clinical application. In mild stroke, where most patients are MEP+, MEP status offers limited discriminatory value. In such cases, prognostication may depend more on baseline clinical severity and quantitative structural measures of CST injury (e.g., lesion load/overlap metrics), rather than MEP status alone.

Similarly, CST lesion load, FA, and lesion volume provide incomplete predictive power, as functional plasticity in non-motor areas can compensate for CST damage. Patients with similar CST injury may achieve different gains due to compensatory network engagement. Clinically, this supports combining CST-based markers with functional assessment and longitudinal monitoring, rather than relying on structural biomarkers alone. It also supports task-specific, high-repetition training with progressive difficulty to promote adaptive reorganization. Longitudinal changes in FA remain inconsistent, making recovery predictions challenging. These findings indicate that single-indicator approaches may be insufficient for some patients. Multimodal models that integrate complementary indicators may be useful, but studies rarely report standardized weighting or the incremental benefit of adding each biomarker, which limits clinical interpretability.

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

While this scoping review provides valuable insights, it has several limitations. Firstly, the heterogeneity in the studies’ designs and assessment methods hinders direct comparisons between studies. To reduce heterogeneity in future prognostic biomarker research, studies should prioritize harmonized outcome definitions and assessment windows, standardized data organization and preprocessing, and quality-control pipelines, and, where feasible, de-identified data and code sharing through collaborative infrastructures that support multisite harmonization and pooled re-analyses [47,48]. Furthermore, most included studies focused on upper-limb motor function and primarily on ischemic stroke, with few studies addressing lower-limb recovery or hemorrhagic stroke, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Evidence on biomarkers for lower limb outcomes remains particularly limited, which constrains the development and validation of prediction models for gait-related recovery and may limit their clinical applicability for mobility outcomes. Additionally, no eligible studies using GRE, EEG, or CT were identified, as none of the retrieved articles met all our inclusion criteria. Consequently, the present synthesis cannot determine whether hemorrhage-sensitive MRI sequences (e.g., GRE), EEG-derived measures, or widely available CT-based markers could improve prognostic models, particularly in hemorrhagic stroke or resource-limited settings. Moreover, by focusing solely on predefined biomarkers during study selection, we may have excluded other potentially relevant predictors. Lastly, multimodal models were reported using heterogeneous integration approaches, often without standardized reporting of biomarker contributions, which limits comparability across studies.

Future research should focus on developing individualized prediction models that integrate clinical, neurophysiological, and imaging data. AI-driven analytics may improve accuracy and help account for variability in recovery trajectories. Although deep learning has been explored in a limited capacity, machine learning techniques can further refine quantitative analyses, such as predictive modeling and effect size estimation. Given the limited and heterogeneous evidence in hemorrhagic stroke, future studies should consistently report stroke subtype and consider subtype-stratified (or interaction) analyses to determine whether biomarker prognostic performance differs between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Longitudinal tracking of neuroplastic changes will help optimize rehabilitation strategies, and integrating multimodal biomarkers into therapy planning could enable more personalized, data-driven interventions.

5. Conclusions

Overall, this scoping review demonstrates that both neurophysiological biomarkers (such as MEPs) and structural imaging markers (including CST lesion load and FA values) possess significant predictive value for post-stroke motor recovery. The integration of these biomarkers into multimodal prognostic models offers a promising avenue for advancing personalized rehabilitation. Nonetheless, the considerable heterogeneity across existing studies underscores the necessity for standardized, large-scale, and longitudinal research to validate and optimize these predictive models for routine clinical use.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010317/s1, Supplementary File S1: PRISMA checklist; Supplementary File S2: Search strategy for databases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C., P.B., R.D.A.L., T.C. and P.K.; methodology, B.C. and P.K.; validation, M.Z. and S.Z.; investigation, P.B., R.D.A.L., T.C. and D.G.; data curation, D.G. and T.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C., P.B., R.D.A.L. and T.C.; writing—review and editing, D.G., M.Z., S.Z., T.R., R.M. and P.K.; visualization, S.Z. and T.R.; supervision, B.C., R.M. and P.K.; project administration, R.M. and P.K.; funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed during this review are included in this manuscript and its Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD | Axial diffusivity |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BI | Barthel Index |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CST | Corticospinal tract |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DTI | Diffusion tensor imaging |

| DWI | Diffusion-weighted imaging |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| FA | Fractional anisotropy |

| FAC | Functional Ambulation Category |

| FM-UE | Fugl–Meyer Assessment, Upper Extremity subscale |

| FMA | Fugl–Meyer Assessment |

| fMRI | Functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| GRE | Gradient echo |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| LDH | Local diffusion homogeneity |

| LE | Lower extremity |

| MD | Mean diffusivity |

| MEP(s) | Motor evoked potential(s) |

| MEP+ | Motor evoked potential present |

| MEP− | Motor evoked potential absent |

| MFG | Middle frontal gyrus |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NIHSS | National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| PCC | Population, Concept, Context |

| PLIC | Posterior limb of the internal capsule |

| PMC | Premotor cortex |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| rFA | Fractional anisotropy ratio |

| rMD | Mean diffusivity ratio |

| rsFC | Resting-state functional connectivity |

| rλ23 | Mean of diffusion tensor eigenvalues λ2 and λ3 ratio |

| SMA | Supplementary motor area |

| TMS | Transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| UE | Upper extremity |

| VLSM | Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping |

| wCST-LL | Weighted corticospinal tract lesion load |

| WE-FM | Whole extremity Fugl–Meyer Assessment |

References

- World Health Organization. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Ananth, C.V.; Brandt, J.S.; Keyes, K.M.; Graham, H.L.; Kostis, J.B.; Kostis, W.J. Epidemiology and Trends in Stroke Mortality in the USA, 1975–2019. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 52, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wafa, H.A.; Wolfe, C.D.A.; Emmett, E.; Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Wang, Y. Burden of Stroke in Europe: Thirty-Year Projections of Incidence, Prevalence, Deaths, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years. Stroke 2020, 51, 2418–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katan, M.; Luft, A. Global Burden of Stroke. Semin. Neurol. 2018, 38, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Thayabaranathan, T.; Donnan, G.A.; Howard, G.; Howard, V.J.; Rothwell, P.M.; Feigin, V.; Norrving, B.; Owolabi, M.; Pandian, J.; et al. Global Stroke Statistics 2019. Int. J. Stroke 2020, 15, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhorne, P.; Bernhardt, J.; Kwakkel, G. Stroke Rehabilitation. Lancet 2011, 377, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmos, M.; Munoz-Novoa, M.; Sunnerhagen, K.; Alt Murphy, M.; Kruuse, C. Upper-Extremity Motor Recovery after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Usual Care in Trials and Observational Studies. J. Neurol. Sci. 2025, 468, 123341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, H.T.; van Limbeek, J.; Geurts, A.C.; Zwarts, M.J. Motor Recovery after Stroke: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.P.; Davis, P.H.; Leira, E.C.; Chang, K.-C.; Bendixen, B.H.; Clarke, W.R.; Woolson, R.F.; Hansen, M.D. Baseline NIH Stroke Scale Score Strongly Predicts Outcome after Stroke. Neurology 1999, 53, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Zarahn, E.; Riley, C.; Speizer, A.; Chong, J.Y.; Lazar, R.M.; Marshall, R.S.; Krakauer, J.W. Inter-Individual Variability in the Capacity for Motor Recovery after Ischemic Stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2008, 22, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, R.H.M.; van Wegen, E.E.H.; Harmeling-van der Wel, B.C.; Kwakkel, G.; for the Early Prediction of Functional Outcome After Stroke (EPOS) Investigators. Accuracy of Physical Therapists’ Early Predictions of Upper-Limb Function in Hospital Stroke Units: The EPOS Study. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupar, F.; Pollock, A.; Rowe, P.; Weir, C.; Langhorne, P. Predictors of Upper Limb Recovery after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2012, 26, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineiro, R.; Pendlebury, S.T.; Smith, S.; Flitney, D.; Blamire, A.M.; Styles, P.; Matthews, P.M. Relating MRI Changes to Motor Deficit After Ischemic Stroke by Segmentation of Functional Motor Pathways. Stroke 2000, 31, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinear, C.M.; Barber, P.A.; Smale, P.R.; Coxon, J.P.; Fleming, M.K.; Byblow, W.D. Functional Potential in Chronic Stroke Patients Depends on Corticospinal Tract Integrity. Brain 2007, 130, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canedo, A. Primary Motor Cortex Influences on the Descending and Ascending Systems. Prog. Neurobiol. 1997, 51, 287–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, R.A. The Pyramidal Tract. Neurology 1990, 40, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, E.R.; Rizk, S.; Nicolo, P.; Cohen, L.G.; Schnider, A.; Guggisberg, A.G. Predicting Motor Improvement after Stroke with Clinical Assessment and Diffusion Tensor Imaging. Neurology 2016, 86, 1924–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, B.; Wang, A.; Stinear, C.M. Proportional Recovery After Stroke: Addressing Concerns Regarding Mathematical Coupling and Ceiling Effects. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2023, 37, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerbeek, J.M.; Winters, C.; van Wegen, E.E.H.; Kwakkel, G. Is the Proportional Recovery Rule Applicable to the Lower Limb after a First-Ever Ischemic Stroke? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.K.; Cheung, D.K.; Climans, S.A.; Black, S.E.; Gao, F.; Szilagyi, G.M.; Mochizuki, G.; Chen, J.L. Determining Corticospinal Tract Injury from Stroke Using Computed Tomography. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 47, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Schlaug, G. Resting State Interhemispheric Motor Connectivity and White Matter Integrity Correlate with Motor Impairment in Chronic Stroke. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Cheng, J.; Miao, P.; Li, Z. Dynamic Relationship Between Interhemispheric Functional Connectivity and Corticospinal Tract Changing Pattern After Subcortical Stroke. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 870718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.Y.; Oh, M.-K.; Park, J.; Paik, N.-J. Does Measurement of Corticospinal Tract Involvement Add Value to Clinical Behavioral Biomarkers in Predicting Motor Recovery after Stroke? Neural Plast. 2020, 2020, 8883839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Wang, J.; Chhatbar, P.Y.; Doughty, C.; Landsittel, D.; Lioutas, V.-A.; Kautz, S.A.; Schlaug, G. Corticospinal Tract Lesion Load: An Imaging Biomarker for Stroke Motor Outcomes. Ann. Neurol. 2015, 78, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Winstein, C. Can Neurological Biomarkers of Brain Impairment Be Used to Predict Poststroke Motor Recovery? A Systematic Review. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2017, 31, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; ISBN 978-0-6488488-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.-C.; Chen, H.-H.; Lee, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H. Predictive Value of Motor-Evoked Potentials for Motor Recovery in Patients with Hemiparesis Secondary to Acute Ischemic Stroke. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2225144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, K.S.; Schmidt, J.; Lohse, K.R.; Peters, S.; Bernhardt, J.; Lannin, N.A.; Boyd, L.A. Are We Armed with the Right Data? Pooled Individual Data Review of Biomarkers in People with Severe Upper Limb Impairment after Stroke. NeuroImage Clin. 2017, 13, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elameer, M.; Lumley, H.; Moore, S.A.; Marshall, K.; Alton, A.; Smith, F.E.; Gani, A.; Blamire, A.; Rodgers, H.; Price, C.I.M.; et al. A Prospective Study of MRI Biomarkers in the Brain and Lower Limb Muscles for Prediction of Lower Limb Motor Recovery Following Stroke. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1229681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Huang, G.; Quan, X.; Qin, Q.; Li, H.; Xu, C.; Liang, Z. Dynamic Structural and Functional Reorganizations Following Motor Stroke. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2021, 27, e929092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, J.; Blasco, G.; Terceño, M.; Daunis-I-Estadella, P.; Schlaug, G.; Hernandez-Perez, M.; Cuba, V.; Carbó, G.; Serena, J.; Essig, M.; et al. Predicting Motor Outcome in Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2019, 40, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Peng, K.; Dang, C.; Tan, S.; Chen, H.; Xie, C.; Xing, S.; Zeng, J. Axial Diffusivity Changes in the Motor Pathway above Stroke Foci and Functional Recovery after Subcortical Infarction. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2018, 36, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Tan, S.; Dang, C.; Peng, K.; Xie, C.; Xing, S.; Zeng, J. Motor Recovery Prediction With Clinical Assessment and Local Diffusion Homogeneity After Acute Subcortical Infarction. Stroke 2017, 48, 2121–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Dang, C.; Chen, X.; Xing, S.; Dani, K.; Xie, C.; Peng, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Structural Remodeling of White Matter in the Contralesional Hemisphere Is Correlated with Early Motor Recovery in Patients with Subcortical Infarction. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2015, 33, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Zhang, F.; Yin, D.-Z.; Hu, Y.-S.; Fan, M.-X.; Ni, H.-H.; Nan, X.-L.; Cui, X.; Zhou, C.-X.; Huang, C.-S.; et al. Diffusion Tensor Imaging for Predicting Hand Motor Outcome in Chronic Stroke Patients. J. Int. Med. Res. 2012, 40, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Qin, W.; Ding, H.; Guo, J.; Han, T.; Cheng, J.; Yu, C. Corticospinal Fibers With Different Origins Impact Motor Outcome and Brain After Subcortical Stroke. Stroke 2020, 51, 2170–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.J.; Cloutier, A.M.; Erler, K.S.; Cassidy, J.M.; Snider, S.B.; Ranford, J.; Parlman, K.; Giatsidis, F.; Burke, J.F.; Schwamm, L.H.; et al. Corticospinal Tract Injury Estimated From Acute Stroke Imaging Predicts Upper Extremity Motor Recovery After Stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 3569–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantin, J.; Pennati, G.V.; Roca, P.; Baron, J.-C.; Laurencikas, E.; Weber, K.; Godbolt, A.K.; Borg, J.; Lindberg, P.G. Quantitative Assessment of Hand Spasticity After Stroke: Imaging Correlates and Impact on Motor Recovery. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.L.; Lindenberg, R.; Alexander, M.P.; Schlaug, G. Lesion Load of the Corticospinal Tract Predicts Motor Impairment in Chronic Stroke. Stroke 2010, 41, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchenall, J.; Térémetz, M.; Roca, P.; Lamy, J.-C.; Oppenheim, C.; Maier, M.A.; Mas, J.-L.; Lamy, C.; Baron, J.-C.; Lindberg, P.G. Individual Recovery Profiles of Manual Dexterity, and Relation to Corticospinal Lesion Load and Excitability after Stroke—A Longitudinal Pilot Study. Neurophysiol. Clin. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 49, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.-J.; Chang, W.H.; Kim, Y.-H. Differential Early Predictive Factors for Upper and Lower Extremity Motor Recovery after Ischaemic Stroke. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Xu, Q.; Hu, J.; Zeng, F.; Lu, G.; Liu, X. Early Functional MRI Activation Predicts Motor Outcome after Ischemic Stroke: A Longitudinal, Multimodal Study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018, 12, 1804–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.S.; Heffron, L.; Mahzarnia, A.; Obeng-Gyasi, B.; Holbrook, M.; Badea, C.T.; Feng, W.; Badea, A. Automated Multimodal Segmentation of Acute Ischemic Stroke Lesions on Clinical MR Images. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2022, 92, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, S.-L.; Zavaliangos-Petropulu, A.; Jahanshad, N.; Lang, C.E.; Hayward, K.S.; Lohse, K.R.; Juliano, J.M.; Assogna, F.; Baugh, L.A.; Bhattacharya, A.K.; et al. The ENIGMA Stroke Recovery Working Group: Big Data Neuroimaging to Study Brain–Behavior Relationships after Stroke. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2022, 43, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian Foroushani, H.; Dhar, R.; Chen, Y.; Gurney, J.; Hamzehloo, A.; Lee, J.-M.; Marcus, D.S. The Stroke Neuro-Imaging Phenotype Repository: An Open Data Science Platform for Stroke Research. Front. Neuroinformatics 2021, 15, 597708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.