Abstract

This systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of iterative reconstruction (IR) and deep learning reconstruction (DLR) in reducing radiation dose in computed tomography (CT) while preserving diagnostic image quality. We systematically searched PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (last search 22 March 2025); the protocol was registered in the OSF (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/TUQDS). Eligible studies were English-language adult (≥18 years) investigations published between 2020 and 2025 that used IR or DLR and reported radiation-dose outcomes; studies on paediatric, phantom, cadaver, cone-beam, and spectral CT were excluded. In accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines, 4371 records were identified, and 30 met the inclusion criteria. Risk of bias was assessed using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool; most studies were deemed to be at low risk. Data were narratively synthesised and structured by a reconstruction approach and anatomical region. Across the 30 studies, IR achieved a dose reduction of 24–50% (mean ≈ 45%) and a DLR reduction of 34–89% (mean ≈ 58%); several DLR protocols enabled reductions of ≥75% without impairing diagnostic quality. Thirty studies in total were included (total N = 2581; range 24–289). It was determined that both approaches substantially reduce radiation exposure while maintaining diagnostic image quality; DLR generally demonstrates greater noise suppression and dose efficiency, especially in ultra-low-dose applications. However, heterogeneity in methods, designs, and scanner technologies limits the ability to draw uniform conclusions. Standardised protocols, multi-vendor prospective studies, and long-term evaluations are needed.

1. Introduction

Ionising radiation poses stochastic and deterministic risks; in CT, protocol optimisation is therefore a central focus to minimise radiation dose while preserving diagnostic accuracy. The repercussions of this form of radiation may manifest as either stochastic effects or deterministic effects, which are contingent upon the dosage and duration of exposure. Since the introduction of computed tomography (CT) in the 1970s, it has become a widely used and integral diagnostic tool in medicine. However, this technological advancement has also contributed to a significant increase in radiation exposure across global populations. In light of ongoing discussions regarding the stochastic effects of ionising radiation, including potential carcinogenic risk, the optimisation of CT protocols has become an important focus in clinical imaging to reduce radiation dose while preserving image quality [1,2].

The concept of keeping radiation “As Low As Reasonably Achievable” (ALARA) is a basis of medical imaging safety, and radiation dose optimisation has become a central topic in CT research and clinical practice. Iterative Reconstruction (IR) and Deep Learning (DLR) techniques have emerged as two promising solutions for dose reduction. IR methods, such as sinogram-affirmed iterative reconstruction (SAFIRE), offer significant noise reduction by reconstructing images iteratively rather than relying solely on traditional filtered back projection [3,4]. Similarly, as reported in the literature, DL-based reconstruction algorithms leverage data training to suppress noise and improve image quality even at substantially reduced radiation doses, offering robust performance across varied clinical scenarios [5,6]. Evidence suggests that IR with techniques like automatic Tube Voltage Modulation (e.g., CARE kV) can achieve radiation dose reductions of up to 41% without compromising image quality [3,4].

Despite significant technological progress, substantial variability in CT radiation doses persists internationally, and it is often attributable not to patient or machine factors but to institutional choices regarding protocol settings [1,2]. Such variability underscores the importance of standardising dose-reduction strategies and promoting wider adoption of advanced reconstruction techniques. The objective of this systematic review is to evaluate human adult CT studies investigating radiation dose reduction achieved by iterative reconstruction and deep learning reconstruction and to compare their dose efficiency and diagnostic image quality across anatomical regions.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic review followed a predefined methodology and is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Extension for Systematic Reviews Guidelines (PRISMA 2020) [7,8]. To ensure methodological transparency and facilitate reproducibility, the protocol has been registered and is publicly available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) under the DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/TUQDS. Full methodological details are transparently reported in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Peer-reviewed human adult studies (≥18 years), 2020–2025, in English, evaluating IR or DLR for CT dose reduction and reporting radiation dose metrics (e.g., CTDIvol, DLP, ED) and/or diagnostic image quality (noise, SNR/CNR, lesion detectability). Paediatric, phantom, cadaver, cone-beam or spectral-CT reviews, guidelines, and non-original research were excluded.

2.2. Information Sources

A comprehensive electronic database search was conducted from February to 22 March 2025, to identify relevant articles published between 2020 and 2025. Searches were performed in PubMed (last searched 22 March 2025), Scopus (22 March 2025) and Web of Science (22 March 2025) using the same predefined queries in all databases.

2.3. Search Strategy

The search strategy development process involved conducting a brief overview of the subject through a preliminary Google search complemented by the author’s expertise and an examination of keywords used in relevant publications. From this process, the following candidate terms were identified: “Computed Tomography”, “CT Exam”, “Dose Reduction”, “Radiation Risk”, “Radiation Dose Reduction”, “Iterative Reconstruction”, “Tube Voltage Modulation”, “Automatic Exposure”, “Tube Current Modulation”, “Noise-based tube current”, and “Innovation”. Each term was individually tested across databases to assess retrieval performance, after which different combinations were evaluated for eligibility.

The final search strategy applied free-text terms to titles and abstracts using three complementary conceptual strings focused on computed tomography, radiation dose reduction, and acquisition-related optimisation techniques. These core search strings were intentionally designed to be broad and vendor-neutral to capture a wide range of reconstruction-based dose optimisation studies. Although deep-learning reconstruction-specific terms were not included as primary search keywords, this approach was adopted to avoid restricting retrieval to particularly proprietary or rapidly evolving algorithm nomenclature. Studies employing deep learning-based reconstruction were nonetheless retrieved through broader reconstruction-related indexing and were included when they met the predefined eligibility criteria. This strategy ensured sensitivity while minimising bias associated with algorithm-specific terminology. Full database-specific strategies are provided in Appendix A Table A1. Filters applied, where available, were humans, article, English, and publication years 2020–2025.

2.4. Selection Process

All retrieved articles were imported into Mendeley (Mendeley Reference Manager—Mendeley, London, UK) [9] and to Rayyan Software (Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) [10]. Duplicate records were identified and removed using Rayyan Software to ensure data integrity. Two reviewers (S.C. and M.L.D.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of 208 records according to the predefined inclusion criteria. Potential relevant studies were retrieved in full text for further assessment. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or, when necessary, by consultation with a third reviewer (J.S.B.). Automation tools were not used during the selection process. Studies were included if they reported radiation dose reduction in CT examinations using IR or DLR. Exclusion criteria comprised studies involving phantoms, paediatrics, cadavers, cone-beam CT, or Spectral CT, as well as studies with incorrect publication types, outcomes, or populations.

2.5. Data Collection

Thirty full-text articles met the inclusion criteria and were screened for data extraction using Rayyan software. The data charting process was conducted with a structured Excel-based data extraction form via SciSpace software (SciSpace; PubGenius Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA) [11]. This process involved systematic extraction of predefined data items initially performed with the support of SciSpace and subsequently verified by two researchers (S.C. and M.L.D.) to ensure accuracy and consistency. In this data form, each line corresponds to a different study. Corresponding authors were contacted if data were missing or unclear.

2.6. Data Items

Eligible outcomes were radiation dose reduction, iterative reconstruction, deep learning, machine learning, dose length product (DLP), CT dose reduction, and CT radiation risk reduction. Any measurement of these outcomes was eligible for inclusion, with no restrictions on the type of measurement. The researcher anticipated that outcomes would be grouped by reconstruction type and anatomic region to facilitate the most comprehensive analysis of the information. If multiple outcomes existed, the result that provided the most complete information was chosen. A formal critical appraisal of the included studies was conducted using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool across multiple domains relevant to observational and before-and-after study designs.

For each selected study, data were extracted regarding the report (author, year, title, and country), study characteristics (research focus and objectives), methodology (study type, population, anatomical region, analysis group, standard/control group, protocol used for screening, reconstructed protocol, standard protocol, equipment type/vendor/model, variables measured, reconstruction type) and research outcomes (radiation dose, dose reduction achieved, image achievements with IR/DLR, most dose reduction vs. image quality, radiation dose reduction achieved with IR/DLR, noise DLR, contrast DLR, main findings regarding radiation dose reduction, conclusions, limitations, future research, detected bias, observations).

2.7. Risk of Bias

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for observational cohort and before-and-after study designs, which is appropriate for the non-randomised imaging designs included in this review. The tool covers nine domains: clarity of study question, definition of the study population and eligibility criteria, group comparability or intra-individual design, reporting of CT acquisition parameters, validity of outcomes measurements, blinding of image reviewers, inter-observer agreement, data completeness, and potential funding/vendor bias. Each domain was rated as low, moderate, or high risk. Items not reported were judged based on their potential to introduce bias. An overall rating was assigned using a conservative worst-case rule, where a domain was considered high if any domain was rated high, moderate if at least one domain was rated moderate, and low when all domains were rated low.

Retrospective design was not automatically penalised, and use of different scanners was not considered a source of bias when inherent to the technology being evaluated (e.g., DLR/IR available only on specific hardware). Funding bias was rated high only when direct industry sponsorship of the study was declared; authors working with vendors without direct study funding were not downgraded.

2.8. Effect Measures

The primary effect measure was the percentage reduction in radiation dose relative to the standard dose protocol. Percentage dose reduction was extracted as reported in each study. It was calculated by comparing reduced-dose acquisitions or reconstruction techniques with the reference protocol used within the same study or institution. As no standardised reference protocol was applied across all included studies, reference dose levels varied according to scanner type, clinical indication, and institutional practice. Secondary effect measures included the mean differences in image noise, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), and qualitative image quality ratings between reconstruction techniques.

2.9. Synthesis of Results

Given the heterogeneity of the included studies, a narrative synthesis was performed. Data were organised by reconstruction techniques (IR or DLR), anatomical region, and reported dose reduction. We tabulated study-level estimates with 95% confidence intervals when reported—region/vendor conducted planned subgroup analyses. Results are presented in tables and organised by the outcome domain within which the studies were conducted.

2.10. Reporting Bias and Certainty Assessment

Potential reporting biases were evaluated qualitatively by examining completeness of outcomes, funding statements, and patterns of publication. Selective reporting, or publication bias, was considered suspected when authors had industry affiliations, although only direct industry funding was considered in the risk-of-bias rating.

Certainty of evidence for each outcome was evaluated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) framework across five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias. Overall certainty for each outcome was rated as high, moderate, or low according to the standard GRADE guidance.

3. Results

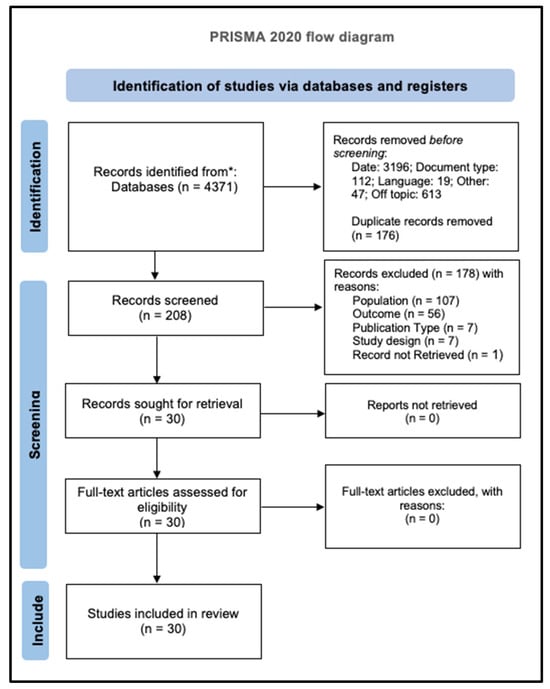

The selection process was done according to the PRISMA methodology. Figure 1 presents an overview of the articles identified in each step.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram: records identified (n = 4371); after deduplication (n = 4195); screened (n = 208); full text assessed (n = 30); included (n = 30). No records were excluded after full-text assessment [8].

3.1. Study Selection

The initial database search retrieved 4371 articles. Subsequently, filters were applied, excluding 3196 by publication date, 112 by document type, 19 due to language criteria, 47 for other reasons (non-human/phantom, non-diagnostic outcomes, or non-CT modalities), and 613 by out-of-topic criteria. This process resulted in 384 articles, from which duplicates were removed using the Rayyan software, resulting in the exclusion of 176 records. During title and abstract screening, 178 of the remaining 208 articles were excluded, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. During the screening process, some studies initially appeared eligible but were excluded because they did not involve human adult populations [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Of the 30 full-text articles, all were retrieved with full text, and none were excluded at this stage, as all met the eligibility criteria.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Study Characteristics Overview

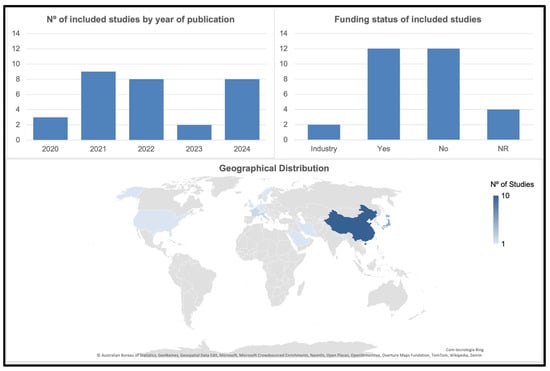

A total of 30 studies were included in this systematic review, which were published between 2020 and 2025. Most publications were concentrated in 2021 (n = 9), followed by 2022 and 2024, with each contributing eight studies. In contrast, 2020 and 2023 had only three and two studies, respectively. Geographically, most investigations were conducted in China (n = 10), followed by Japan (n = 5) and Korea (n = 4), indicating a significant prevalence in East Asia. A few studies originated from Europe (Italy, France, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom), the Middle East (Iran and Saudi Arabia), and the United States.

Study Design and Duration

Although all studies were comparative, some heterogeneity existed in study designs. The majority were prospective comparative studies (n = 12), followed by retrospective comparative studies (n = 9). A smaller portion consisted of comparative designs without specified temporal directions (n = 6). In addition, one study used a mixed comparative design, combining prospective, and retrospective cohorts (n = 1) [21], and one study employed a cross-sectional comparative approach (n = 1) [22]. One study was classified as a prospective multi-institutional comparative study (n = 1) [23]. Overall, the evidence base is characterised by non-randomised, comparative designs, reflecting real-world clinical and feasibility constraints in CT dose-reduction research. The duration of the included studies ranged from 2 to 42 months, with an average duration of approximately 10 months, reflecting medium-term investigations into imaging practices and outcomes.

Other variables that may influence interpretation.

Information on funding varied across the included studies. Two studies reported financial support from scanner manufacturers, representing a potential source of industry-related influence [23,24]. Twelve studies were funded by academic or public institutions, including universities, hospitals, foundations, or national research programmes, with no apparent commercial conflicts of interest [2,4,21,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Four studies did not provide funding information [34,35,36,37]. The remaining studies explicitly declared no funding, suggesting a low likelihood of external influence on their findings [22,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

Figure 2 provides a visual overview of key study characteristics, including publication trends, funding status, and geographical distribution. Detailed methodological and clinical characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Visual summary of study characteristics, number of publications per year, funding classification, and geographical distribution of the included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 30 included studies, including publication year, country, study design, population, anatomical region, scanner model, reconstruction technique, standard protocol, low-dose protocol, and dose reduction achieved.

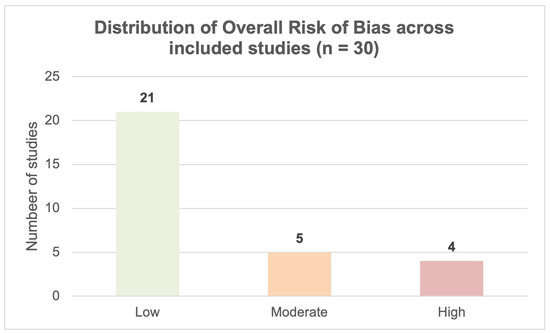

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool. Overall, the evidence base demonstrated acceptable methodological robustness, with 21 of 30 studies (70.0%) judged to be at low risk of bias, 5 (16.7%) at moderate risk, and 4 (13.3%) at high risk of bias. Most low-risk studies employed intra-individual designs, which minimised confounding and ensured strong internal validity. The moderate-risk design rating was primarily attributed to between-group comparisons without randomisation, limited blinding of image reviewers, or incomplete reporting of inter-observer reliability. High-risk ratings occurred in studies with substantial methodological constraints, including unblinded assessments and the absence of standardised image-quality methods. Importantly, the reporting of radiation dose (CTDIvol, DLP, ED) was consistently comprehensive across all studies. The overall risk-of-bias profile supports the credibility of the observed improvements in dose reduction and image quality.

Detailed domain-level assessments are provided in Appendix A Table A2 and Figure A1, with the overall distribution of risk of bias shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of overall risk of bias ratings across the 30 included studies; based on the NIH Quality Assessment Tool (21 low, 5 moderate, and 4 high risk).

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

To support transparency and allow comparison across heterogeneous study designs, the detailed results of each study are presented in Table 2. This table reports the absolute dose metrics, percentage dose reduction, and key findings related to image quality metrics.

Table 2.

Summaries of absolute dose metrics, percentage dose reduction, and key findings related to image quality metrics. Funding codes: NR = not reported; No = no funding declared; Yes = funding received but not from manufacturers; Industry = manufacturer-funded.

The review summarises multiple studies assessing radiation dose reduction in CT exams using IR or DLR. IR was analysed in 6 studies and DLR in 24 studies. Some studies mentioned the commercial name of the reconstruction tool, but for standardisation and comparison, they were categorised into IR or DLR.

All included studies achieved dose reduction while maintaining diagnostic image quality [2,31,35,40]. In most studies, preservation of diagnostic image quality was inferred from objective image quality metrics and radiologist-based assessment rather than from formal diagnostic accuracy testing. On average, iterative reconstruction achieved a 45.4% dose reduction, whereas deep learning reconstruction achieved a mean decrease of 58.4%. As shown in Table 3, IR protocols reported dose reductions ranging from 24% to 50%, while DLR yielded substantially wider and higher reductions, ranging from 34% to 89%, with several studies exceeding 75% [25,34]. Deep learning reconstruction consistently allowed greater dose reduction than conventional IR while maintaining or improving image quality, as supported by marked noise suppression and enhanced SNR/CNR performance across multiple studies [2,21,32]. Image quality assessment varied across the included studies: the majority reported objective, quantitative metrics, including noise measurements, SNR, CNR, and related parameters. Subjective image quality evaluation by radiologists using Likert or Visual grading scales was also frequently employed, often in combination with objective measures. Only one study relied exclusively on subjective image assessment without reporting quantitative image quality metrics [35].

Table 3.

Comparison of hybrid iterative reconstruction (HIR), model-based iterative reconstruction (MBIR), and deep learning reconstruction (DLR) across standard CT quality and dose metrics.

Eight anatomical regions were represented across the included studies. The abdomen was the most frequently investigated site (12/30; 40%) [23,27,32], followed by combined abdomen and pelvis (5/30; 16.7%) and combined chest and abdomen examinations (4/30; 13.3%). Chest-only studies accounted for 10% (3/30), while brain and cardiac examinations were each represented by two studies (6.7%). Highly specific protocols, such as Brain and Cardiac (Stroke) and whole-body Head–Chest–Abdomen acquisitions, were reported only once each [33,39]. This distribution reflects the broad clinical applications of low-dose CT techniques across emergency, oncological, thoracic, abdominal, and cardiovascular settings. Table 4 summarises the mean dose reduction achieved within each anatomical region, together with the reconstruction technique applied and its typical clinical contexts.

Table 4.

Summary of radiation dose reduction by anatomical region across 30 studies. It integrates study counts, reconstruction techniques, mean percentage dose reduction, and main clinical applicability.

Sample sizes across the studies ranged widely, ranging from 24 to 289 participants, with an estimated mean of 86 patients per study. Across all 30 studies, population sizes were sufficient to support comparative analyses of reconstruction algorithms and dose-reduction strategies. However, demographic details such as age, sex, or BMI were inconsistently reported and therefore not used for table standardisation. Regarding image reconstruction techniques, iterative reconstruction was used in approximately 20% of the studies (n = 6), while deep learning-based reconstruction was notably more prevalent, featuring in 70% of the studies (n = 21). Three studies used both methods. This highlights the growing adoption of DLR technologies in dose-reduction strategies.

Among studies reporting quantitative dose reduction, the average reduction achieved was 58.4% (±21.2%), underscoring the substantial potential of advanced reconstruction methods, particularly DLR, to lower radiation exposure while maintaining diagnostic image quality. Table 2 presents the dose reduction achieved in each study, along with the reconstruction technique employed.

A broad range of CT scanners and reconstruction systems was represented across the included studies. Canon Medical (Otawara, Japan) and GE Healthcare (Chicago, IL, USA) accounted for most of the datasets, using systems ranging from 64- to 128-slice scanners to 320-detector Aquillon One and Revolution Apex platforms. Philips Healthcare (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and Siemens Healthineers (Erlangen, Germany) systems were also represented, although less frequently, together with isolated examples from Toshiba and United Imaging. Reconstruction approaches included conventional IR families (ASIR, ASI-V, AIDR, iDOSE, IMR); model-based IR; and several DLR implementations such as TrueFidelity, DLIR, AiCE, and Precis DL (Beta). Some studies used generic or custom reconstruction pipelines where vendor information was not reported. Overall, this diversity reflects the rapid evolution of reconstruction technologies and the growing interest in optimising CT dose efficiency across manufacturers, as summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Vendors, scanner models, iterative reconstruction (IR) algorithms, and deep learning reconstruction (DLR) version represented in the 30 included studies.

3.5. Reporting Biases and Certainty of Evidence

Based on the assessment of publication bias, no strong evidence of selective reporting or publication bias was identified. Although a small number of studies involved authors affiliated with scanner manufacturers, only two studies reported direct industry funding, and these were appropriately accounted for in the risk-of-bias and GRADE assessment. Most studies were classified as undetected for publication bias, suggesting that there are no indications of unpublished negative results. This assessment provides confidence that the reported effects are not driven by the selective non-publication of studies with negative findings.

Certainty of evidence, evaluated using the GRADE framework, was predominantly high across core outcomes. Twenty-six studies (86.7%) were graded as high certainty, reflecting effects, precise estimates, and well-reported methodologies. Two studies (6.7%) were graded as moderate certainty, typically due to residual confounding or limited sample sizes, and two studies (6.7%) were graded as low certainty, mainly because of high risk of bias or inconsistency. Certainty was particularly strong for radiation dose reduction and image quality metrics (noise, SNR, CNR) and moderate for lesion detection due to sample size variations. These findings indicate that the evidence supporting the benefits of dose reduction and image quality preservation in low-dose CT protocols is reliable and robust. An overall distribution of risk of bias is presented in Figure 4, and the synthesis of the GRADE certainty assessment is provided in Appendix A Table A3, with study-level linkage provided in Table A4.

Figure 4.

Summary of certainty across the 30 studies.

4. Discussion

This systematic review summarises the existing literature on radiation dose reduction in CT examinations with IR and DLR. The research findings demonstrate considerable variability across studies in the assessment of reconstruction algorithms, including differences in technical characteristics, clinical applications, and reported outcomes related to dose reduction and image quality. Overall, the review highlights the ongoing evolution and clinical impact of advanced image reconstruction techniques—particularly iterative reconstruction and deep learning-based reconstruction in supporting radiation dose optimisation in computed tomography.

It is important to note that IR and DLR techniques do not directly reduce radiation dose in isolation. Instead, the dose reductions reported across the included studies reflect the extent to which these reconstruction methods enable the optimisation of acquisition parameters—such as tube voltage, tube current, automatic tube current modulation, noise index, and protocol design—while maintaining diagnostic image quality. Within this context, DLR and IR were generally associated with meaningful radiation dose reductions in optimised CT protocols across the 30 included studies while preserving diagnostic image quality. Several studies reported that low-dose or ultra-low-dose CT protocols incorporating DLR maintained both subjective and objective image quality, with improvements in noise, SNR, and CNR when compared with IR [27,35,40,41].

The results reinforce the emerging consensus in the literature: deep learning reconstruction techniques were generally associated with better performance than iterative reconstruction approaches in achieving radiation dose reduction across various clinical applications. In this review, DLR achieved larger dose reductions (median ≈ 58%) than IR (≈45%), with several DLR protocols enabling ≥75% reduction while preserving diagnostic quality [25,34,35,43]. In the present review, DLR consistently achieved larger reductions (median ≈ 62%) than IR (≈45%), with several DLR protocols enabling ≥75% reduction while preserving diagnostic quality.

DLR methods demonstrated a trend toward greater substantial dose reductions than traditional IR approaches while maintaining or even improving diagnostic image quality. DLR was generally associated with better performance than IR in terms of radiation dose mitigation. Among studies implementing DLR algorithms, dose reductions ranged up to 83% [25], with several studies reporting reductions well above 70% [27,34,35,40]. On average, DLR studies achieved a mean dose reduction of 58.4%, with a standard deviation of ±21.2%, supporting the reproducibility of findings across studies of this technique in clinical settings. In contrast, while effective, IR methods generally yielded more modest reductions, which were often limited by image noise and longer reconstruction times [4,28,36,47].

In abdominal and thoracic imaging, where dose accumulation is particularly concerning due to the frequency of surveillance imaging, DLR protocols achieved median reductions of up to 76% while preserving or improving diagnostic confidence. These figures reflect their enhanced performance in real-world clinical applications, such as cardiac and lung CT [26,29]. DLR reduced doses in abdominal CT by 54–76% [21,31,32,34,40,43] and in cardiac CT enabled a 43% reduction in coronary CTA, with the dose reduced to 0.8 mSv without stenosis misclassification [44]. Ultra-low-dose CT with sub-mSv doses (<1 mSv) was achieved in the evaluation of pulmonary nodules [29]. In contrast, while effective, IR methods generally yielded more modest reductions, often limited by image noise and longer reconstruction times [35,46]. For oncology follow-up, MBIR enabled a 75% dose reduction in metastatic liver surveillance [33].

In terms of image quality, DLR has superior noise reduction and higher SNR/CNR vs. IR [43]. IR improved diagnostic confidence, but with higher noise at extreme dose reductions [47]. Hybrid IR introduced artefacts in abdominal CT [43]. MBIR performance varied across scanners [21,43,46]. A strong conclusion was that DLR maintains diagnostic acceptability even at very low dose levels, including in challenging clinical cases such as colonography [25], coronary calcium scoring [26,39,44], urolithiases [38], interstitial lung imaging [30], emphysema quantification [2], and abdominal oncology assessment [32,33,41,43]. In some cases, DLR was reported to provide improved lesion detectability or anatomical conspicuity compared with hybrid or model-based IR, as reported in comparative studies [25,27,30,37,42,44].

DLR enables high-quality LDCT for lung cancer screening [29]. In comparative designs where both methods were applied, several studies reported an advantage of DLR. For instance, refs. [27,40,41] demonstrated that DLR yielded better contrast-to-noise ratios and improved lesion detectability at significantly lower radiation doses than IR. These findings are particularly relevant for populations that require repeated imaging, such as patients with oncology or those undergoing chronic disease follow-up.

The importance of regional and institutional protocol standardisation is also evident, as significant dose variability often stems from site-specific decisions rather than patient or technical constraints. Practical approaches include harmonising acquisition parameters, using reference dose thresholds by anatomical region, and the routine incorporation of DRL into protocol optimisation workflows. However, despite the technical benefits reported for iterative and deep learning reconstruction techniques, several practical barriers to widespread clinical adoption remain. These include requirements for dedicated computational infrastructure and the associated implementation and maintenance costs, challenges related to integrating into existing clinical workflows, and the need for targeted staff training, particularly in resource-limited settings. Broader implementations of DLR will depend on continued regulatory endorsement, vendor-specific integration, and rigorous validation in large-scale, multi-centre clinical trials. DLR-based techniques represent the next evolution in low-dose CT imaging. Overall, DLR represents an evolving approach to dose optimisation in CT imaging, with studies suggesting potential benefits across a range of clinical applications, particularly in examinations with higher imaging frequency or radiation exposure.

Limitations and Biases in Current Research

Despite the promising results, several limitations emerged across the included studies. Many relied on small, single-centre samples with short study durations, which may limit generalisability. Patient BMI was frequently cited as a constraint, with some studies reporting lower BMI values compared to global averages. This may overestimate the apparent performance of DLR [27,31,32]. In addition, dose reduction percentages were derived from within-study comparisons using institution-specific reference protocols, which limits the direct comparability of quantitative dose reduction values across studies. Although most studies assessed image quality using objective quantitative metrics—such as image noise, SNR, and CNR—the choice of metrics, measurement methods, and scoring systems varied considerably, and subjective radiologist-based assessments were inconsistently applied. This methodological variability restricts direct cross-study comparisons and precludes quantitative synthesis. Nevertheless, within the scope of dose optimisation, these metrics and radiologist assessment were consistently used to support the conclusion that radiation dose reductions could be achieved without clinically relevant loss of diagnostic capability.

Further limitations relate to technological scope and external validity. The predominance of vendor-specific reconstruction software further limits cross-platform comparability, as most DLR studies were conducted on GE/Canon scanners (n = 18/30), which can introduce a degree of vendor bias into the evidence base and limit the generalisability of these findings to other major CT vendors, such as Siemens or Philips. The restriction of the review to studies published between 2020 and 2025 was intended to focus on contemporary reconstruction technologies currently implemented in clinical practice; however, this approach excludes earlier evidence on iterative reconstruction and may place greater emphasis on more recent deep learning-based implementations.

Methodological biases also emerged, predominantly selection bias due to retrospective designs and the exclusion of specific subgroups, such as obese or paediatric populations. Twelve studies reported some form of institutional collaboration or technical support from equipment manufacturers; however, only two studies reported direct manufacturer funding [23,24]. Although no consistent pattern of vendor-dependent bias was identified, and most studies were rated to have a low risk of bias according to the NIH Quality Assessment, the potential for optimism bias in studies with manufacturer involvement cannot be entirely excluded. A minority of studies presented moderate or high concerns, which were mainly related to limited blinding and insufficient reporting of inclusion criteria.

The certainty of evidence, as assessed by the GRADE, was high for most objective dose-reduction outcomes but decreased to moderate or low for subjective image quality measures, reflecting limitations inherent to non-randomised designs, heterogeneity in scanning protocols, and small sample sizes. Despite these constraints, the body of evidence demonstrates overall methodological robustness and internal consistency, providing a reliable foundation for advancing IR and DLR applications in CT dose reduction.

Further research would benefit from larger, multi-centric studies to improve generalisability across diverse populations and clinical settings. Greater standardisation of dose reporting metrics (CTDIvol, DLP, and effective dose) and reconstruction parameters across vendors may also facilitate reproducibility and cross-study comparability. From a practical perspective, DLR has been increasingly explored as a reconstruction option in clinical practice where available. However, its broader implementation remains dependent on local infrastructure, regulatory considerations, and further validation. Additionally, the integration of DLR with artificial intelligence-assisted diagnostics represents a promising direction for advancing in this field.

5. Conclusions

In 30 human adult studies (2020–2025), iterative reconstruction achieved ~24–50% dose reductions (mean ≈ 45%), while deep learning reconstruction achieved ~34–89% (mean ≈ 58%), with several DLR protocols enabling ≥ 75% reductions while maintaining diagnostic image quality. Given heterogeneity, a narrative synthesis was appropriate. Overall certainty ranged from high for dose-reduction and image quality outcomes to moderate–low for lesion detection, indicating that while the evidence strongly supports dose optimisation, deep learning-based reconstruction may be considered as part of dose optimisation strategies where available, with caution regarding diagnostic performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.C. and M.d.L.D.; methodology, S.C. and J.S.B.; investigation, S.C. and M.d.L.D.; data curation, S.C. and M.d.L.D.; formal analysis, S.C. and M.d.L.D.; writing –original draft preparation, S.C.; writing – review and editing, S.C. and M.d.L.D., M.F. and J.S.B.; supervision, J.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated. Template forms and extracted tables are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author; no analytic code was used.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the professors of the Doctoral Program in Occupational Safety and Health at the University of Porto.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Database-specific strategies.

Table A1.

Database-specific strategies.

| Database | Platform | Search String (Title/Abstract) | Filters Applied | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | NCBI | ((“Computed Tomography”[All Fields] OR “CT Exam”[All Fields]) AND (“Dose Reduction”[All Fields] OR “Radiation Risk”[All Fields] OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”[All Fields]) AND (“Iterative Reconstruction”[All Fields] OR “Tube Voltage Modulation”[All Fields])) AND ((humans[Filter]) AND (2020/1/1:2025/3/22[pdat]) AND (english[Filter])) | Humans, English; 2020–2025 | 22 March 2025 |

| ((“Computed Tomography”[All Fields] OR “CT Exam”[All Fields]) AND (“Dose Reduction”[All Fields] OR “Radiation Risk”[All Fields] OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”[All Fields]) AND (“Automatic Exposure”[All Fields] OR “Tube Current Modulation”[All Fields])) AND ((humans[Filter]) AND (2020/1/1:2025/3/22[pdat]) AND (english[Filter])) | ||||

| ((“Computed Tomography”[All Fields] OR “CT Exam”[All Fields]) AND (“Dose Reduction”[All Fields] OR “Radiation Risk”[All Fields] OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”[All Fields]) AND (“Noise-Based Tube Current”[All Fields] OR “Innovation”[All Fields])) AND ((humans[Filter]) AND (2020/1/1:2025/3/22[pdat]) AND (english[Filter])) | ||||

| Scopus | Elsevier | TITLE-ABS-KEY((“Computed Tomography” OR “CT Exam”) AND (“Dose Reduction” OR “Radiation Risk” OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”) AND (“Iterative Reconstruction” OR “Tube Voltage Modulation”))AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,”ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE,”j”)) AND LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE,”English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE,”final”)) | Article, Journal, English; 2020–2025 | 22 March 2025 |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY((“Computed Tomography” OR “CT Exam”) AND (“Dose Reduction” OR “Radiation Risk” OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”) AND (“Automatic Exposure” OR “Tube Current Modulation”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,”ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE,”j”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE,”English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE,”final”)) | ||||

| TITLE-ABS-KEY((“Computed Tomography” OR “CT Exam”) AND (“Dose Reduction” OR “Radiation Risk” OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”) AND (“Noise-Based Tube Current” OR “Innovation”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE,”j”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE,”English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,”ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,”re”)) | ||||

| Web of Science | Clarivate | (“Computed Tomography” OR “CT Exam”) AND (“Dose Reduction” OR “Radiation Risk” OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”) AND (“Iterative Reconstruction” OR “Tube Voltage Modulation”) (Topic) and 2025 or 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 (Publication Years) and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages) | Article, English; 2020–2025 | 22 March 2025 |

| (“Computed Tomography” OR “CT Exam”) AND (“Dose Reduction” OR “Radiation Risk” OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”) AND (“Automatic Exposure” OR “Tube Current Modulation”) (Topic) and 2025 or 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 (Publication Years) and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages) and Article (Document Types) | ||||

| (“Computed Tomography” OR “CT Exam”) AND (“Dose Reduction” OR “Radiation Risk” OR “Radiation Dose Reduction”) AND (“Noise-Based Tube Current” OR “Innovation”) (Topic) and 2025 or 2023 or 2021 or 2020 (Publication Years) and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages) |

Table A2.

Risk of bias.

Table A2.

Risk of bias.

| Ref. | Authors | Date | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 | Overall RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | Jeong-A Yeom, Ki-Uk Kim, et al. | 7.2022 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [4] | Karolin J Paprottka, Karina Kupfer, et al. | 11.2021 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [21] | Weitao He, Ping Xu, and Mengchen Zhang, et al. | 9.2024 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [22] | Sarah Prod’homme, Roger Bouzerar, et al. | 3.2024 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [23] | Ramandeep Singh, Subba R Digumarthy, et al. | 3.2020 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | High | High |

| [24] | Yuko Nakamura, Keigo Narita, et al. | 1.2021 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High |

| [25] | Yanshan Chen, Zixuan Huang, et al. | 3.2024 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [26] | Liyong Zhuo, Shijie Xu, et al. | 9.2024 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [27] | Akio Tamura, Eisuke Mukaida, et al. | 5.2022 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [28] | Ali Chaparian, Mohamadhosein Asemanrafat, et al. | 12.2021 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [29] | Huiyuan Zhu, Zike Huang, et al. | 11.2024 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [30] | Ruijie Zhao, Xin Sui, et al. | 6.2022 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [31] | Shumeng Zhu, Baoping Zhan, et al. | 9.2024 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [32] | Nieun Seo, Mi-Suk Park, et al. | 2.2021 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| [33] | Peijie Lyu, Zhen Li, et al. | 1.2023 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [34] | Tetsuro Kaga, Yoshifumi Noda, et al. | 3.2022 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| [35] | E Hettinger, M.-L Aurumskjöld, H Sartor, et al. | 3.2021 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [36] | Hayato Tomita, Kenji Kuramochi, et al. | 6.2022 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [37] | Xu Lin, Yankun Gao, et al. | 3.2024 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| [38] | Abdul Rauf, Saqib Javed, et al. | 10.2023 | Low | Moderate | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| [39] | Angélique Bernard, Pierre-Olivier Comby, et al. | 1.2021 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [40] | L E Cao, Xiang Liu, et al. | 9.2020 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [41] | June Park, Jaeseung Shin, et al. | 1.2022 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [42] | Emilio Quaia, Elena Kiyomi, et al. | 6.2024 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [43] | Sungeun Park, Jeong Hee Yoon, et al. | 7.2022 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [44] | Dominik C Benz and Sara Ersözlü, et al. | 11.2022 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| [45] | Lingming Zeng, Xu Xu, et al. | 1.2021 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| [46] | Davide Ippolito, Cesare Maino, et al. | 6.2021 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| [47] | A Sulieman, H Adam, et al. | 5.2020 | Low | Low | High | Low | Moderate | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| [48] | Yoshifumi Noda, Tetsuro Kaga, et al. | 2.2021 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Table A3.

Summary of certainty of evidence (GRADE) for each outcome category across included studies.

Table A3.

Summary of certainty of evidence (GRADE) for each outcome category across included studies.

| Ref. | Authors | Main Outcome | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Imprecision | Indirectness | Publication Bias | Overall Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | Jeong-A Yeom, Ki-Uk Kim, et al. | Emphysema quantification (ULCT vs. SDCT) | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [4] | Karolin J Paprottka, Karina Kupfer, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [21] | Weitao He, Ping Xu, and Mengchen Zhang, et al. | CT enterography IQ + dose (IBD) | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [22] | Sarah Prod’homme, Roger Bouzerar, et al. | Stone detection on sub-mSv CT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [23] | Ramandeep Singh, Subba R Digumarthy, et al. | Sub-mSv chest/abdominal CT DLIR vs. IR | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Suspected | Moderate |

| [24] | Yuko Nakamura, Keigo Narita, et al. | U-HRCT abdomen DLIR vs. IR/MBIR | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Suspected | Moderate |

| [25] | Yanshan Chen, Zixuan Huang, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [26] | Liyong Zhuo, Shijie Xu, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [27] | Akio Tamura, Eisuke Mukaida, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [28] | Ali Chaparian, Mohamadhosein Asemanrafat, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [29] | Huiyuan Zhu, Zike Huang, et al. | Sub-mSv LDCT for subsolid nodules | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [30] | Ruijie Zhao, Xin Sui, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [31] | Shumeng Zhu, Baoping Zhan, et al. | Abdominal LDCT with DLIR vs. routine dose IR | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [32] | Nieun Seo, Mi-Suk Park, et al. | ULDCT IR in follow-up of abscess | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [33] | Peijie Lyu, Zhen Li, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [34] | Tetsuro Kaga, Yoshifumi Noda, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [35] | E Hettinger, M.-L Aurumskjöld, H Sartor, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [36] | Hayato Tomita, Kenji Kuramochi, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [37] | Xu Lin, Yankun Gao, et al. | LD DECT enterography DLIR vs. ASIR-V | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Suspected | High |

| [38] | Abdul Rauf, Saqib Javed, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | Low |

| [39] | Angélique Bernard, Pierre-Olivier Comby, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [40] | L E Cao, Xiang Liu, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [41] | June Park, Jaeseung Shin, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [42] | Emilio Quaia, Elena Kiyomi, et al. | ICU CT: DLIR vs. FBP/IR dose + IQ | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [43] | Sungeun Park, Jeong Hee Yoon, et al. | Liver CT: LD DLD vs. SD MBIR | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Suspected | High |

| [44] | Dominik C Benz and Sara Ersözlü, et al. | CCTA dose + plaque metrics | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Suspected | High |

| [45] | Lingming Zeng, Xu Xu, et al. | Half-dose liver CT DLIR vs. HIR | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [46] | Davide Ippolito, Cesare Maino, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| [47] | A Sulieman, H Adam, et al. | Dose metrics with IR package | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | Low |

| [48] | Yoshifumi Noda, Tetsuro Kaga, et al. | Whole-body CT lesion detection + dose | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

Table A4.

Study-level linkage between included studies, their primary outcome, and GRADE certainty of evidence.

Table A4.

Study-level linkage between included studies, their primary outcome, and GRADE certainty of evidence.

| Ref. | Author | Outcome | GRADE Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | Jeong-A Yeom, Ki-Uk Kim, et al. | Emphysema quantification (ULCT vs. SDCT) | High |

| [4] | Karolin J Paprottka, Karina Kupfer, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | |

| [21] | Weitao He, Ping Xu, and Mengchen Zhang, et al. | CT enterography IQ + dose (IBD) | High |

| [22] | Sarah Prod’homme, Roger Bouzerar, et al. | Stone detection on sub-mSv CT | High |

| [23] | Ramandeep Singh, Subba R Digumarthy, et al. | Sub-mSv chest/abd CT DLIR vs. IR | Moderate |

| [24] | Yuko Nakamura, Keigo Narita, et al. | U-HRCT abdomen DLIR vs. IR/MBIR | Moderate |

| [25] | Yanshan Chen, Zixuan Huang, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [26] | Liyong Zhuo, Shijie Xu, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [27] | Akio Tamura, Eisuke Mukaida, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [28] | Ali Chaparian, Mohamadhosein Asemanrafat, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [29] | Huiyuan Zhu, Zike Huang, et al. | Sub-mSv LDCT for subsolid nodules | High |

| [30] | Ruijie Zhao, Xin Sui, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [31] | Shumeng Zhu, Baoping Zhan, et al. | Abdominal LDCT with DLIR vs. routine dose IR | High |

| [32] | Nieun Seo, Mi-Suk Park, et al. | ULDCT IR in follow-up of abscess | High |

| [33] | Peijie Lyu, Zhen Li, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [34] | Tetsuro Kaga, Yoshifumi Noda, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [35] | E Hettinger, M.-L Aurumskjöld, H Sartor, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [36] | Hayato Tomita, Kenji Kuramochi, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [37] | Xu Lin, Yankun Gao, et al. | LD DECT enterography DLIR vs. ASIR-V | High |

| [38] | Abdul Rauf, Saqib Javed, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | Low |

| [39] | Angélique Bernard, Pierre-Olivier Comby, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [40] | L E Cao, Xiang Liu, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [41] | June Park, Jaeseung Shin, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [42] | Emilio Quaia, Elena Kiyomi, et al. | ICU CT: DLIR vs. FBP/IR dose + IQ | High |

| [43] | Sungeun Park, Jeong Hee Yoon, et al. | Liver CT: LD DLD vs. SD MBIR | High |

| [44] | Dominik C Benz and Sara Ersözlü, et al. | CCTA dose + plaque metrics | High |

| [45] | Lingming Zeng, Xu Xu, et al. | Half-dose liver CT DLIR vs. HIR | High |

| [46] | Davide Ippolito, Cesare Maino, et al. | Dose reduction + image quality | High |

| [47] | A Sulieman, H Adam, et al. | Dose metrics with IR package | Low |

| [48] | Yoshifumi Noda, Tetsuro Kaga, et al. | Whole-body CT lesion detection + dose | High |

Figure A1.

Summary of risk of bias across studies by domains.

References

- Smith-Bindman, R.; Wang, Y.; Chu, P.; Chung, R.; Einstein, A.J.; Balcombe, J.; Cocker, M.; Das, M.; Delman, B.N.; Flynn, M.; et al. International Variation in Radiation Dose for Computed Tomography Examinations: Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2019, 364, k4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeom, J.A.; Kim, K.U.; Hwang, M.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, K.I.; Song, Y.S.; Lee, I.S.; Jeong, Y.J. Emphysema Quantification Using Ultra-Low-Dose Chest CT: Efficacy of Deep Learning-Based Image Reconstruction. Medicina 2022, 58, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.J.; Chung, Y.E.; Lee, Y.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, M.S.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, K.W. Radiation Dose Reduction via Sinogram Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction and Automatic Tube Voltage Modulation (CARE KV) in Abdominal CT. Korean J. Radiol. 2013, 14, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paprottka, K.J.; Kupfer, K.; Riederer, I.; Zimmer, C.; Beer, M.; Noël, P.B.; Baum, T.; Kirschke, J.S.; Sollmann, N. Impact of Dose Reduction and Iterative Model Reconstruction on Multi-Detector CT Imaging of the Brain in Patients with Suspected Ischemic Stroke. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskan, O.; Erol, C.; Ozbek, H.; Paksoy, Y. Effect of Radiation Dose Reduction on Image Quality in Adult Head CT with Noise-Suppressing Reconstruction System with a 256 Slice MDCT. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2015, 16, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyanov, D.; Vedaldi, A.; Lempitsky, V. Deep Image Prior. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 9446–9454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendeley. Com/Reference-Manager. Available online: http://www.mendeley.com (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCISPACE. Available online: http://www.scispace.com (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Rozema, R.; Kruitbosch, H.T.; van Minnen, B.; Dorgelo, B.; Kraeima, J.; van Ooijen, P.M.A. Structural Similarity Analysis of Midfacial Fractures—A Feasibility Study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2022, 12, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozema, R.; Kruitbosch, H.T.; van Minnen, B.; Dorgelo, B.; Kraeima, J.; van Ooijen, P.M.A. Iterative Reconstruction and Deep Learning Algorithms for Enabling Low-Dose Computed Tomography in Midfacial Trauma. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2021, 132, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldle, P.; Grunz, J.P.; Kunz, A.S.; Pannenbecker, P.; Patzer, T.S.; Pichlmeier, S.; Sauer, S.T.; Hendel, R.; Ergün, S.; Bley, T.A.; et al. Influence of Spectral Shaping and Tube Voltage Modulation in Ultralow-Dose Computed Tomography of the Abdomen. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boubaker, F.; Puel, U.; Eliezer, M.; Hossu, G.; Assabah, B.; Haioun, K.; Blum, A.; Gondim-Teixeira, P.A.; Parietti-Winkler, C.; Gillet, R. Radiation Dose Reduction and Image Quality Improvement with Ultra-High Resolution Temporal Bone CT Using Deep Learning-Based Reconstruction: An Anatomical Study. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2024, 105, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaihati, N.; Solomon, J.; McCrum, E.; Samei, E. Development, Validation, and Application of a Generic Image-Based Noise Addition Method for Simulating Reduced Dose Computed Tomography Images. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, K.; Kanbe, T.; Matsushima, H.; Ohtani, Y.; Tanikawa, K.; Kaneko, M. Three-Dimensional CT Imaging in Extensor Tendons Using Deep Learning Reconstruction: Optimal Reconstruction Parameters and the Influence of Dose. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2023, 46, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legeas, O.; Bourhis, D.; Garetier, M.; Pennaneach, A.; Meriot, P.; Ognard, J.; Ben Salem, D. Quantitative and Qualitative Optimisation of Dosimetry in Computed Tomography Explorations of the Temporal Bone Using Two Iterative Reconstruction Algorithms. Neurosci. Inform. 2021, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emoto, T.; Nagayama, Y.; Takada, S.; Sakabe, D.; Shigematsu, S.; Goto, M.; Nakato, K.; Yoshida, R.; Harai, R.; Kidoh, M.; et al. Super-Resolution Deep-Learning Reconstruction for Cardiac CT: Impact of Radiation Dose and Focal Spot Size on Task-Based Image Quality. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2024, 47, 1001–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, H.; Shin, D.S.; Lee, Y. Feasibility Study of Hybrid Scanning Technique Parameters on Dose Reduction and CT-Image Quality. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 226, 112179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xu, P.; Zhang, M.; Xu, R.; Shen, X.; Mao, R.; Li, X.H.; Sun, C.H.; Zhang, R.N.; Lin, S. Deep Learning-Based Reconstruction Improves the Image Quality of Low-Dose CT Enterography in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Abdom. Radiol. 2024, 50, 3907–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prod’homme, S.; Bouzerar, R.; Forzini, T.; Delabie, A.; Renard, C. Detection of Urinary Tract Stones on Submillisievert Abdominopelvic CT Imaging with Deep-Learning Image Reconstruction Algorithm (DLIR). Abdom. Radiol. 2024, 49, 1987–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Digumarthy, S.R.; Muse, V.V.; Kambadakone, A.R.; Blake, M.A.; Tabari, A.; Hoi, Y.; Akino, N.; Angel, E.; Madan, R.; et al. Image Quality and Lesion Detection on Deep Learning Reconstruction and Iterative Reconstruction of Submillisievert Chest and Abdominal CT. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020, 214, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Narita, K.; Higaki, T.; Akagi, M.; Honda, Y.; Awai, K. Diagnostic Value of Deep Learning Reconstruction for Radiation Dose Reduction at Abdominal Ultra-High-Resolution CT. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 4700–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Feng, L.; Zou, W.; Kong, D.; Zhu, D.; Dai, G.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, M. Deep Learning-Based Reconstruction Improves the Image Quality of Low-Dose CT Colonography. Acad. Radiol. 2024, 31, 3191–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, L.; Xu, S.; Zhang, G.; Xing, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Yin, X. Ultralow Dose Coronary Calcium Scoring CT at Reduced Tube Voltage and Current by Using Deep Learning Image Reconstruction. Eur. J. Radiol. 2024, 181, 111742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, A.; Mukaida, E.; Ota, Y.; Nakamura, I.; Arakita, K.; Yoshioka, K. Deep Learning Reconstruction Allows Low-Dose Imaging While Maintaining Image Quality: Comparison of Deep Learning Reconstruction and Hybrid Iterative Reconstruction in Contrast-Enhanced Abdominal CT. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2022, 12, 2977–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemanrafat, M.; Chaparian, A.; Lotfi, M.; Rasekhi, A. Impact of Iterative Reconstruction Algorithms on Image Quality and Radiation Dose in Computed Tomography Scan of Patients with Malignant Pancreatic Lesions. J. Med. Signals Sens. 2022, 12, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Ma, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Tao, G.; Xing, J.; Jiang, H.; Sun, X.; et al. Feasibility of Sub-MilliSievert Low-Dose Computed Tomography with Deep Learning Image Reconstruction in Evaluating Pulmonary Subsolid Nodules: A Prospective Intra-Individual Comparison Study. Acad. Radiol. 2024, 32, 2309–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Sui, X.; Qin, R.; Du, H.; Song, L.; Tian, D.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Song, W.; et al. Can Deep Learning Improve Image Quality of Low-Dose CT: A Prospective Study in Interstitial Lung Disease. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 8140–8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, B.; Tian, Q.; Li, A.; Liu, Z.; Hou, W.; Zhao, W.; Huang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Reduced-Dose Deep Learning Iterative Reconstruction for Abdominal Computed Tomography with Low Tube Voltage and Tube Current. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, N.; Park, M.S.; Choi, J.Y.; Yeom, J.S.; Kim, M.J.; Chung, Y.E.; Ku, N.S. A Prospective Study on the Use of Ultralow-Dose Computed Tomography with Iterative Reconstruction for the Follow-up of Patients Liver and Renal Abscess. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, P.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, N.; Liu, J.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X.; Shang, B.; Wang, L.; et al. Deep Learning Reconstruction CT for Liver Metastases: Low-Dose Dual-Energy vs Standard-Dose Single-Energy. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaga, T.; Noda, Y.; Mori, T.; Kawai, N.; Miyoshi, T.; Hyodo, F.; Kato, H.; Matsuo, M. Unenhanced Abdominal Low-Dose CT Reconstructed with Deep Learning-Based Image Reconstruction: Image Quality and Anatomical Structure Depiction. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2022, 40, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettinger, E.; Aurumskjöld, M.L.; Sartor, H.; Holmquist, F.; Svärd, D.; Timberg, P. Evaluation of Model-Based Iterative Reconstruction in Abdominal Computed Tomography Imaging at Two Different Dose Levels. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2021, 195, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, H.; Kuramochi, K.; Fujikawa, A.; Ikeda, H.; Komita, M.; Kurihara, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Mimura, H. Effects of Model-Based Iterative Reconstruction in Low-Dose Paranasal Computed Tomography: A Comparison with Filtered Back Projection and Hybrid Iterative Reconstruction. Acta Med. Okayama 2022, 76, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Song, J.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Wu, X. Improved Overall Image Quality in Low-Dose Dual-Energy Computed Tomography Enterography Using Deep-Learning Image Reconstruction. Abdom. Radiol. 2024, 49, 2979–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Javed, S.; Chandrasekar, B.; Miah, S.; Lyttle, M.; Siraj, M.; Mukherjee, R.; McLeavy, C.M.; Alaaraj, H.; Hawkins, R. The Use of Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning Reconstruction in Urological Computed Tomography: Dose Reduction at Ghost Level. Urol. Ann. 2023, 15, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Comby, P.O.; Lemogne, B.; Haioun, K.; Ricolfi, F.; Chevallier, O.; Loffroy, R. Deep Learning Reconstruction versus Iterative Reconstruction for Cardiac CT Angiography in a Stroke Imaging Protocol: Reduced Radiation Dose and Improved Image Quality. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2021, 11, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Qu, T.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, J.; Sun, J.; Guo, J. A Study of Using a Deep Learning Image Reconstruction to Improve the Image Quality of Extremely Low-Dose Contrast-Enhanced Abdominal CT for Patients with Hepatic Lesions. Br. J. Radiol. 2021, 94, 20201086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Shin, J.; Min, I.K.; Bae, H.; Kim, Y.-E.; Chung, Y.E. Image Quality and Lesion Detectability of Lower-Dose Abdominopelvic CT Obtained Using Deep Learning Image Reconstruction. Korean J. Radiol. 2022, 23, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaia, E.; Kiyomi Lanza de Cristoforis, E.; Agostini, E.; Zanon, C. Computed Tomography Effective Dose and Image Quality in Deep Learning Image Reconstruction in Intensive Care Patients Compared to Iterative Algorithms. Tomography 2024, 10, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yoon, J.H.; Joo, I.; Yu, M.H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.; Kim, S.W.; Han, S.; Ahn, C.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Image Quality in Liver CT: Low-Dose Deep Learning vs Standard-Dose Model-Based Iterative Reconstructions. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 2865–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, D.C.; Ersözlü, S.; Mojon, F.L.A.; Messerli, M.; Mitulla, A.K.; Ciancone, D.; Kenkel, D.; Schaab, J.A.; Gebhard, C.; Pazhenkottil, A.P.; et al. Radiation Dose Reduction with Deep-Learning Image Reconstruction for Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 2620–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Xu, X.; Zeng, W.; Peng, W.; Zhang, J.; Sixian, H.; Liu, K.; Xia, C.; Li, Z. Deep Learning Trained Algorithm Maintains the Quality of Half-Dose Contrast-Enhanced Liver Computed Tomography Images: Comparison with Hybrid Iterative Reconstruction: Study for the Application of Deep Learning Noise Reduction Technology in Low Dose. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 135, 109487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ippolito, D.; Maino, C.; Pecorelli, A.; Salemi, I.; Gandola, D.; Riva, L.; Franzesi, C.T.; Sironi, S. Application of Low-Dose CT Combined with Model-Based Iterative Reconstruction Algorithm in Oncologic Patients during Follow-up: Dose Reduction and Image Quality. Br. J. Radiol. 2021, 94, 20201223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulieman, A.; Adam, H.; Elnour, A.; Tamam, N.; Alhaili, A.; Alkhorayef, M.; Alghamdi, S.; Khandaker, M.U.; Bradley, D.A. Patient Radiation Dose Reduction Using a Commercial Iterative Reconstruction Technique Package. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2021, 178, 108996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, Y.; Kaga, T.; Kawai, N.; Miyoshi, T.; Kawada, H.; Hyodo, F.; Kambadakone, A.; Matsuo, M. Low-Dose Whole-Body CT Using Deep Learning Image Reconstruction: Image Quality and Lesion Detection. Br. J. Radiol. 2021, 94, 20201329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.