Featured Application

This work is designed for satellite on-board registration of remote sensing images, with limited storage or computational resources. It would significantly improve the timeliness of satellite data.

Abstract

Satellite on-board registration is becoming increasingly prevalent since it shortens the data processing chain, enabling users to acquire actionable information more efficiently. However, current on-board processing hardware exhibits severely constrained storage and computational resources, making traditional ground-based methods infeasible in terms of storage and time efficiency. Meanwhile, real-time orbit parameters are normally less accurate, causing a large initial geolocation offset. In this paper, we propose a novel registration framework based on a well-designed lightweight universal database to address the challenges of limited storage as well as poor initial accuracy. Firstly, for the global matching step, a lightweight universal database is designed by storing a feature vector of control points instead of a traditional basemap (such as Digital Orthophoto Map and Digital Surface Model) for on-board processing. We replace the keypoint detection stage with a sparse sampling strategy, which significantly improves time efficiency. In addition, the sparsely sampled control points avoid the problem of keypoint repeatability, allowing the proposed method to perform robust global matching with few control points and little storage usage. Then, for the local matching step, we introduce relative total variation to extract the most obvious and significant structures from the basemap, so that unimportant feature or noise can be omitted from the database. Combined with Run-Length Encoding, the masked binary edge feature yields high precision with considerably reduced storage. Quantitative experiments demonstrate that the proposed reference database occupies less than of raw image storage, while maintaining efficiency and accuracy comparable to SOTA methods.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of satellite platforms and payload hardware, low-cost, lightweight, and constellation-capable satellites have become a mainstream approach for Earth observation [1,2,3]. At the same time, the spatial resolution of satellite systems continues to improve. Current operational Earth observation satellites typically achieve 0.5 m resolution, while Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites demonstrate capabilities of up to 0.3 m resolution. Notably, China’s Gaofen-11 satellite reaches 0.1 m resolution during close-range observations. The expansion of satellite constellations and advances in imaging resolution have together led to an exponential increase in remote sensing data volume [4]. State-of-the-art (SOTA) satellites offer clear advantages in launch flexibility, cost efficiency, and on-board intelligent processing hardware, making it possible to deploy satellite networks for rapid collaborative observation [5].

The increasing frequency of natural disasters and escalating geopolitical tensions have placed time-sensitive Earth observation at the forefront of industry priorities, making rapid response a critical determinant in addressing emergent events. This urgency has rendered the inherent conflict between conventional data processing workflows and the demand for high temporal resolution increasingly acute. Systemic inefficiencies persist throughout the end-to-end workflow, from data acquisition to operational deployment. In a traditional workflow, satellites must first downlink raw data to ground stations when within coverage, after which computational analysis is performed on Earth. This multi-stage pipeline—encompassing data transmission, ground processing, and product dissemination—typically requires hours to days, resulting in insufficient responsiveness for emergency scenarios and necessitating substantial human intervention. Furthermore, this approach suffers from several major drawbacks, which are exacerbated by explosively growing data volumes: The estimation and adjustment of satellite imaging parameters are entirely dependent on ground systems, leading to complex implementation paths, multiple intermediate links, poor timeliness, and low execution efficiency. Downlinked data often contain substantial invalid information, such as scenes with excessive cloud cover, areas lacking the mission target, or unusable content due to poor imaging conditions. These invalid data cause a significant waste of satellite resources, consumes ground system capacity, and places undue pressure on downlink bandwidth [6,7]. Consequently, the specific target information users need becomes buried within massive volumes of raw downlinked data, as ground systems must fully process all data before specific images can be extracted and utilized.

High-precision geometric rectification is an essential prerequisite for conducting on-board tasks such as change detection, terrain classification, and mission-specific military operations. This necessity motivates the investigation of a novel spaceborne feature matching methodology in this study. Given the significant constraints of on-board hardware compared to ground-based systems, specially designed processing approaches are required. Satellite storage units, for instance, predominantly employ radiation-hardened EMMC (Embedded MultiMediaCard) architectures to endure the unique space environment. While radiation-hardened, these storage resources remain strictly limited, necessitating the development of a lightweight reference feature library. For example, a global 1 m resolution basemap would require approximately 150 TB of storage, far exceeding typical on-board capacity. Furthermore, on-board systems are subject to multiple constraints, including power consumption, thermal management, and strict size/weight limitations [6,8,9]. Additionally, less accurate real-time orbit parameters often lead to larger initial geometric offsets. These limitations preclude the unrestricted hardware expansion feasible in ground stations, compelling the adoption of highly efficient and optimized methodologies. Critically, traditional approaches relying on full-resolution basemaps or ground control point (GCP) libraries demand excessive storage. Therefore, a compact, lightweight feature database that can be deployed within stringent on-board storage constraints is imperative.

It is therefore clear that both the compression of the feature library and the simplification of algorithms affect registration accuracy, necessitating a balanced design in our methodology. Given the substantial compression of the reference feature library and the constrained on-board computational capacity, the positioning accuracy achievable on-board is not expected to equal that of ground-based processing. Nevertheless, our method can still deliver sufficiently accurate positioning to support subsequent on-board tasks such as change detection and terrain classification. Moreover, on-board positioning enables the selective downlink of image slices from regions of interest (ROIs) with improved geo-reference accuracy to ground stations for further high-precision processing [10,11]. This reduces the burden on satellite-ground transmission systems and enhances overall operational efficiency. Consequently, for on-board positioning, the most critical metrics are storage footprint and processing timeliness. A certain degree of accuracy compromise under these constraints is considered acceptable.

There has been extensive research conducted on image matching methods and algorithms for on-board hardware implementation. Wan et al. developed Weighted Structure Saliency Feature (WSSF) and improved-gradient location and orientation histogram (GLOH) methods to enhance matching performance [12]. Yang et al. proposed a registration method based on adjacent self-similarity-based 3D convolution (ASTC) [13]. Efe et al. introduced a Deep Feature Matching (DFM) method, which eliminates the need for keypoint detection [14]. Xiang et al. applied phase congruency approaches to SAR images (SARPC) [15]. However, nearly all these methods require access to original images or abundant GCPs for reference, making these methods impractical for on-board satellite storage.

For on-board processing algorithms, common strategies include reducing algorithmic complexity or deploying solutions on specialized hardware. Most algorithms can be simplified through approximations—albeit with some performance trade-offs—such as dimensionality reduction [16,17], quantization [18,19,20], calculation approximation [21,22], or the integration of neural networks [7,11,23]. Applications in military operations, disaster response, and humanitarian missions require integrated remote sensing services that are available around the clock and capable of time-critical responses. This drives the development of intelligent spaceborne processing architectures that utilize AI-accelerated hardware to deliver high computational performance, ultra-low power consumption, and multifunctional capabilities. Such systems must support cross-domain applicability through the systematic integration of advanced AI algorithms and domain-specific models, thereby enabling real-time solutions beyond the limits of conventional approaches. Furthermore, AI model parameters should be dynamically reconfigurable via all-weather satellite constellations, allowing adaptive optimization for diverse industrial applications through space–ground collaborative intelligence.

Digital Signal Processors (DSPs) and Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) have traditionally been the primary computing hardware for satellite systems [10,24,25,26,27,28,29]. While providing strong performance in power consumption control and computational efficiency, these devices face limitations in addressing emerging operational imperatives for on-board processing systems. In recent years, Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) have demonstrated significant advantages in development ecosystems, dynamic reconfiguration capabilities, and versatility, positioning them as potential dominant platforms for future satellite edge computing.

Certain on-board processing tasks have demonstrated the capability of GPUs to efficiently process data in parallel. Wang et al. implemented an on-board streaming computation scheme based on an embedded NVIDIA GPU platform, meeting the real-time correction requirements in terms of performance, power consumption, efficiency, and accuracy [4]. Xu et al. combined CFAR detection with a lightweight deep learning network to realize an on-board ship detection scheme on a spaceborne GPU computing platform, reducing processing time by nearly half compared to traditional methods [7]. Xie et al. utilized the lightweight MobileNetV2 network to extract features and improved the triplet loss, embedding control point features into a hypersphere to save storage space. They tested processing times under different power budgets on an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier, achieving positioning accuracy within 30 m [23]. In another work, Xie et al. parallelized differential geo-registration on a GPU to eliminate geometric distortion between panchromatic and multispectral images, achieving near-real-time processing efficiency [30]. Inzerillo et al. designed two knowledge distillation components to enhance the teacher model’s guidance for the student model, thereby developing a lightweight model with performance comparable to the original one, which improved the real-time capability of on-board change detection [31]. As general-purpose computing hardware, GPUs enable dynamic allocation of computational tasks across satellite networks within constellations, freeing systems from application-specific constraints. Moreover, their mature ecosystem offers enhanced accessibility and are developer-friendly.

In this paper, we present an on-board rectification database under a two-step framework, including a high-dimensional feature vector database for fast global localization and a binary edge feature database for accurate refinement. We apply sparse sampling to the global database and main-structure ROI extraction to the local registration database to minimize overall data storage. Both global and local registration are implemented on GPUs to guarantee efficiency. Quantitative experiments confirm that the proposed method achieves viability in efficiency and accuracy, with storage usage below of the original images. The proposed method is different from existing studies in two aspects. First, it does not apply the traditional feature extraction-hash learning framework. Instead, the feature compression method introduced applies sparse sampling and an RTV mask. Although these techniques are widely applied, they have never been applied to image registration for the purpose of storage reduction. Secondly, methods exist for on-board registration task of satellite images, but they could not be applied to SAR images in the past since their feature library was too simple; the proposed two-step database can be applied to SAR images. The major contributions of this work are as follows:

1. A robust multi-source reference database establishment method applicable to all land-cover types with high accuracy.

2. A terrain-agnostic database compression method combining sparse sampling for the global database and automatic ROI mask generation for the local registration database.

3. A two-step matching framework design and GPU-accelerated implementation for enhanced computational efficiency.

2. Related Works

Current global spaceborne processing systems reveal critical gaps in systematic architectural design. Predominantly limited to technology demonstrations, experimental trials, or basic scenario implementations, these systems lack the standardized platform ecosystems and system-level engineering required for sustained, around-the-clock operational readiness. This highlights a substantial shortfall in achieving full-scale deployment. On-board processing hardware remains largely reliant on DSP–FPGA hybrid architectures, with commercial AI accelerators (e.g., from NVIDIA, Cambricon, or Orbita) yet to see widespread adoption. Moreover, prevailing spaceborne platforms predominantly follow closed-system paradigms that lack open-architecture standards, significantly hindering the debugging, testing, and validation lifecycle of AI algorithms. These constraints fundamentally limit the cross-platform scalability, technology dissemination, and iterative evolution of satellite-based intelligent processing systems.

Due to the early stage of development in spaceborne intelligent computing platforms and the stringent storage constraints of on-board processing, there is currently limited international research on making the feature library lightweight. In contrast, some scholars have conducted a certain degree of research in this area. For example, Huo et al. utilized hash mapping learning to achieve lightweight descriptors and adaptive matching for on-board control points, improving the robustness, stability, and efficiency of on-board matching [32]. Yue et al. employed hash learning and a Hamming space to map original floating-point feature descriptors, resulting in higher computational efficiency and better method generalizability [33]. Zhang et al. also used sparse coding to address storage space and matching efficiency issues [34]. Ji et al. generated control points through block adjustment, described features using SIFT, and converted feature descriptors into hash codes, achieving a compression ratio of over 300 times compared to before hash learning [35]. Chen et al. proposed a method that uses the relative positions of celestial bodies in space as a reference to construct a feature library for on-orbit geometric correction. However, their algorithm stores positional information of star maps and relies on relativity theory along with internal and external parameter models for calibration, making it unsuitable for the remote sensing image registration task studied in this paper [36].

From the above review of current research, it can be seen that existing methods primarily remain within the framework of feature extraction–sparse coding. The so-called hash learning, or hash mapping learning, refers to specific algorithms that map high-dimensional feature vectors into low-dimensional binary data, while ensuring that similar original data remain close after mapping and dissimilar ones become distant. Although binarization mapping based on hash learning significantly reduces the storage occupied by feature descriptors, the irreversible information loss caused by sparse coding—mapping high-dimensional features into low-dimensional binary representations—severely compromises their descriptive and matching capabilities. The limited expressive power of binary coding substantially damages the information contained within the features. Furthermore, since complex designs are often required in matching to improve success rates and accuracy across multi-source images, hash learning struggles to ensure that the encoded results retain sufficiently strong matching ability. Moreover, most of these methods rely solely on SIFT for feature point detection, without considering the differences between multi-source images or whether feature points consistently appear at the same locations in both reference and target images. Relying on a single handcrafted feature extraction approach cannot guarantee strong representational ability under complex conditions. Additionally, the simple mapping process appended after feature extraction increases the risk of unstable registration results. Such a mapping process, like hash learning, lacks remote sensing physical meaning, making it difficult to ensure reliable performance. In more recent research, Zhao et al. used multiple images of the same area under different observation conditions and employed various feature extraction algorithms to investigate the repeatability of GCPs [37], aiming to identify stable and repeatable keypoints across different times and methods. However, for a global feature library, the workload required to collect dozens of suitable images for every region on Earth is prohibitively large. Additionally, this method does not account for differences in imaging characteristics across various sensors and performs well only on optical imagery.

The current mainstream approach to make the feature library lightweight typically focuses on keeping the number of GCPs unchanged while making the feature vectors sparse. However, if the descriptive power of the feature vectors is insufficient, even a large number of GCPs cannot achieve effective matching. This paper adopts a different perspective for feature library compression: reducing the number of GCPs while preserving the completeness of the feature vectors. Even if the number of available reference control points is limited, as long as the feature vectors possess sufficient matching performance, a reliable matching result can still be provided. Regarding the potential impact of reduced control points on accuracy, this paper does not rely solely on the GCP method to maintain precision. Instead, after coarse matching is completed using the GCP method, a lightweight edge template feature library is introduced to perform fine matching. This feature library avoids the large storage capacity required by complex features while ensuring final positioning accuracy. Compared to existing research, the proposed method better meets the various requirements of on-board processing.

Building upon our previous work which employed a global-to-local framework, we note that micro-satellites often exhibit large initial positioning offsets. Therefore, performing coarse image localization prior to precise registration is advisable to avoid excessively broad search ranges. For instance, Xiang et al. proposed a global-to-local registration method based on multidirectional anisotropic Gaussian derivatives (MAGDs) [38]. In our own prior research, we developed a database compression method using a similar two-step registration framework [39]. However, that method specifically targeted areas with distinctive linear features, such as airport runways and coastlines. These regions could be pre-labeled using OpenStreetMap and converted into masks for database reduction, which limited its generalizability to arbitrary geographic areas. In the present study, we replace the open-source geolocation ROI with an automated main-structure mask to establish a lightweight database applicable regardless of terrain type. This proposed mask generation strategy imposes no constraints on terrain feature types, enabling the lightweight database to cover entire islands or continents. Furthermore, we replace the previously used downsampled binary edge features for global registration with a more robust and reliable feature vector database, thereby enhancing the overall stability and reliability of the method.

3. Methodology

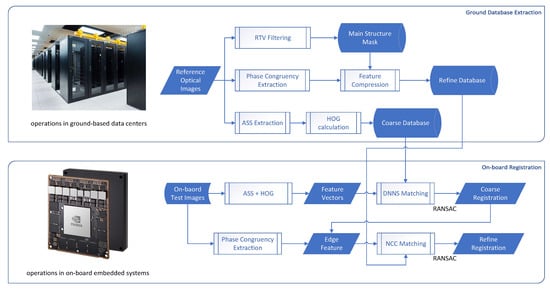

The proposed method follows a two-step registration framework, as illustrated in Figure 1. First, a global registration database is constructed using adjacent self-similarity (ASS) feature extraction [40] combined with a novel sparse sampling strategy. Subsequently, a local registration database is built based on phase congruency features, and relative total variation (RTV) [41] is applied to retain only the most essential structural information. Through this global-to-local framework, the method achieves high efficiency, improved accuracy, and significantly reduced storage requirements. The reference database is prepared in ground-based data centers and uploaded to the satellite before launch, enabling fully autonomous on-board operation without dependency on ground systems during mission execution.

Figure 1.

Overall structure of the proposed method. The coarse (ASS+HOG), refined (PC) database, and mask (RTV) are extracted at ground data center, then stored on-board satellites. The testing images extract coarse and refined features simultaneously before two-step registration.

3.1. Global Registration Database Construction

To establish a lightweight feature vector database for global registration, our goal is to obtain relatively accurate geolocation estimates, thereby narrowing the subsequent search radius for local registration. The proposed method is adapted from existing approaches to satisfy the constraints of on-board processing.

Although keypoint detection is effective for image registration, its repeatability—especially across multi-sensor platforms—remains a critical limitation. Moreover, feature descriptors must be both robust and compact to optimize storage efficiency. Our solution builds upon the RIFT (Rotation-Invariant Feature Transform) framework [42]. We replace phase congruency with adjacent self-similarity (ASS) to improve cross-sensor feature consistency [40]. By eliminating conventional keypoint detection, we implement a sparse uniform sampling strategy and characterize reference points using directional histograms with enlarged sampling windows.

The ASS feature represents an improved feature representation with reduced computational and memory costs. It compares adjacent subimages by applying a local statistics-weighted difference operation to suppress coherent speckle noise, making it particularly suitable for multi-source image registration [40]. We define a window W whose center is the same as the original image. The width and height of window W is 2 pixels less than the original image; therefore, W can be interpreted as the original image without boundary pixels. The central subimage slice is the image cropped within range W, while other subimage slices are acquired by moving W in different directions by 1 pixel. The mathematical definition of these subimages is expressed as:

The self-similarity map response at an arbitrary orientation is defined as:

where k is the weight function based on image average and variance, and is a window with radius 2, which was recommended by the original author [40]. The discrete index map of the maximum SSM is then written as:

where is a threshold value to suppress noise. In our experiment, was set to 0.001 for optical images and 0.05 for SAR images. The values of were adjusted according to the extraction effect of ASS index map. Subsequently, the index map O can be converted into histogram vectors to serve as feature descriptors. The Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) represents a classical approach for describing keypoint features. In SIFT-based methods, an image patch is divided into blocks, with each block contributing a histogram of gradient orientations. However, precise registration remains challenging because such statistical representations are not optimal for pixel-level matching. In contrast, compressing image patches into histogram-based feature vectors significantly reduces storage requirements. A compact descriptor of this kind is well suited to global registration, delivering sufficient accuracy to reduce initial offsets. As shown in Figure 2, the ASS index maps exhibit moderate structural consistency between optical and SAR images, which supports successful matching.

Figure 2.

Index map of ASS on optical and SAR images.

Conventional keypoint detectors are often sensitive to variations in imaging conditions and sensor characteristics, frequently requiring a large number of ground control points (GCPs) to ensure reliability. To overcome this limitation, we replace keypoint localization with a fixed-interval grid-based sparse sampling strategy. For reference images, we adopt a sampling step of 200 pixels; coordinates are thus recorded at positions such as (200,200), (200,400), (400,200), and (400,400). While the reference image uses a coarse step (e.g., 200 pixels), the sensed image is sampled at a much finer interval (e.g., 10–20 pixels). This design theoretically ensures that any pixel in the sensed image lies within 5 pixels (half of the finer step) of a reference coordinate, providing sub-pixel alignment accuracy adequate for subsequent refinement. Compared to keypoint-dependent methods, this systematic sampling strategy substantially reduces the number of feature vectors required.

Although bypassing keypoint detection may reduce the repeatability of individual reference point locations, our approach emphasizes improving the repeatability of feature vectors through structural enhancement. Under default RIFT parameters, the histogram window size is set to 96 pixels. While smaller windows enhance discriminative power for precise matching, global registration prioritizes maximizing feature overlap over pixel-level precision. Therefore, we expand the window size to 384 pixels. This enlarged configuration allows histogram vectors to capture broader contextual information, increasing their similarity across corresponding regions compared to the original 96-pixel implementation.

Figure 3 demonstrates the proposed feature vector description strategy. With a 96-pixel histogram window, reference window 1 and sensed window 2 exhibit no spatial overlap. When expanded to a 384-pixel range, reference window 3 and sensed window 4 share a overlapping area, significantly enhancing feature vector similarity. During the establishment of the reference database, histogram normalization is omitted to reduce storage. But before on-board registration, the system would temporarily perform histogram normalization to the reference feature vectors in the selected geographic range, which only takes a short time. Therefore, the storage optimization does not affect accuracy. Since most histogram values remain below 256, each entry requires only 1 byte of storage instead of 4 bytes for floating-point numbers. Collectively, the proposed global database enhances feature vector repeatability while reducing stored point density, thus achieving sufficient accuracy for subsequent refinement processes. The sampling interval parameters are adjustable based on the actual registration performance. Our goal is to keep the global registration error under 10 pixels. A large sampling interval would increase the chance of mismatch in global registration, while a small one would result in more control points, leading to more storage. We first set the sampling intervals to a larger value to reduce storage and establish the reference database. If the global registration turns out to be unstable (failure or error greater than 10 pixels), we reduce the sampling interval to increase the robustness of global registration, and vice versa. After several rounds of adjustment, the intervals are finally set to 200 pixels for optical and 100 pixels for SAR as the result, since multi-source image similarity is weaker. It should also be noted that more control points also requires more GPU memory usage for parallelization.

Figure 3.

The HOG calculation window before and after adjustments. The adjusted windows 3 and 4 have much more overlap than before.

3.2. Local Registration Database Construction

As previously noted, the results of global registration remain preliminary and require further refinement using a local registration database. In earlier work, we demonstrated the feasibility of a masked-edge feature database for specific target areas [39], where feature compression was guided by four principles: intrinsicality, invariance, robustness, and uniqueness. Specifically, features extracted from the same scene must remain consistent across different imaging conditions and modalities, be resilient to minor terrain variations, and retain sufficient distinctiveness to support reliable matching. However, constructing a global database makes it impractical to manually define fixed patterns for all terrain types. This necessitates an automated region-of-interest (ROI) selection strategy rather than reliance on manual annotation. While adjacent self-similarity (ASS) improves the cross-sensor similarity of index maps, multi-scale phase congruency offers superior pixel-wise registration accuracy for precise local alignment.

Total variation was applied in our other previous work as an image smoothing method [43]. RTV is an extension of total variation, which happens to meet our requirements as an ROI selection method [41]. The general total variation measure is written as:

where R(p) is a window around pixel p, q belongs to window R(p), and x and y denote the directions of derivatives. is a weight function:

The parameter is the window scope. The general total variation preserves both prominent structures and texture elements. However, in a lightweight database, we wish to preserve as little information as possible. Compared to random textures, the main structures obviously fit our feature selection principles better. A novel windowed inherent variation helps distinguish between main structures and normal texture:

It does not sum the absolute values of gradients. Therefore, if the gradients in a window coincide, would be significant, which indicates the main structure. On the other hand, a small determines that the region belongs to texture regions. The overall loss function is written as:

During the filtering process, still eliminates noise, which is similar to the original TV model. The difference is that is small in texture regions, while remaining large in main structures. Since the optimization process minimizes , texture regions gradually disappear as iterations increase. At the end of filtering, we obtain a main structure image without noise, fine details, or textures.

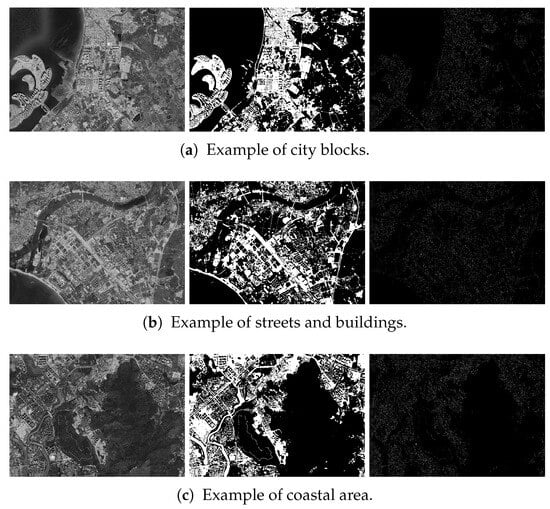

After generating the main structure binary mask, we apply Run-Length Encoding (RLE) to compress the masked edge features. As demonstrated in our earlier work, RLE proves to be an effective technique for reducing storage requirements in this design. The binary mask contains extensive continuous regions of zero values, which can be recorded by storing the count of zeros rather than each individual digit. By retaining only the principal structures, the mask preserves sufficient information for successful registration, while the high-resolution pixel-wise edge features ensure accurate matching results. This fully automatic strategy does not rely on specific terrain types and can therefore be easily generalized to global scenarios. Examples of the resulting masked features are presented in Figure 4, where the most stable and reliable edges are preserved by the main structure mask. In each example, the left panel shows the original basemap, the middle panel displays the RTV-extracted mask, and the right panel presents the final masked edges. The RTV model automatically extracts the dominant structures, which are most discriminative and useful for local registration.

Figure 4.

Illustration of feature in local registration database, including the original reference images, the RTV masks, and masked edges.

3.3. Global-to-Local Overall Framework

The global and local databases described above are constructed in ground-based data centers and uploaded to the satellite for on-board storage. During on-board processing, each acquired image undergoes a two-step global-to-local registration procedure. The advantages of this hierarchical matching strategy were outlined in previous sections. When an image is first captured, its initial geometric localization accuracy is typically poor, making a direct wide-area search highly inefficient. Within the two-step framework, global registration quickly provides a coarse but sufficiently accurate location estimate. This significantly narrows the search space for subsequent refinement, thereby greatly reducing computational cost.

We next explain how the proposed database design aligns with the requirements of this two-step framework. The framework itself builds upon our prior work, which used downsampled template features for global registration [39]. In this study, we revisit the feature design strategy for the global reference database. The earlier simplified approach proved less effective in regions with indistinct features, prompting our shift to a feature vector-based global registration database. Unlike template features, feature vectors support geolocation-aware matching across the entire database, effectively handling large initial positioning offsets.

The refinement stage continues to utilize masked edge features as registration elements, a method whose efficacy was established in our previous work [39]. Since deriving a universal masking rule through prior knowledge is impractical, we propose to automatically extract dominant structural outlines from reference images. This allows the region-of-interest (ROI) masks to generalize across diverse geographic regions. To this end, we introduce relative total variation (RTV) to preserve structures with high contrast, large scale, and well-defined shapes—such as streets, buildings, bridges, highways, rivers, and agricultural fields—while filtering out fine details and noise. This approach achieves performance comparable to earlier methods without relying on prior knowledge or imposing localization constraints.

Both the global and local registration databases are built from optical basemaps. The adjacent self-similarity (ASS) and phase congruency features are applicable to cross-modal image registration, as they were sufficiently validated in prior research. Therefore, the proposed processing framework applies to both optical and SAR sensed images, with only minor adjustments in parameters and the phase congruency algorithm for SAR data [15].

The overall framework is illustrated in Figure 1. First, global registration is performed by searching the feature vector database using the approximate geolocation metadata of the input image. Subsequently, refinement is carried out by querying the binary edge features and ROI masks within the local database. It is important to note that high precision is required only in the local registration phase, while global registration prioritizes computational efficiency. Furthermore, in on-board processing tasks, storage constraints take precedence over other metrics. The specific details of the registration algorithms are elaborated in the following section.

3.4. Matching Algorithm Implementation

In this section, we introduce the details of the matching methods. For global registration of high-dimensional feature vectors, we use the Dense Nearest Neighbor Searching (DNNS) algorithm to find matching pairs. For local registration of template features, the masked NCC (Normalized Cross Correlation) algorithm in our previous work is applied. Both algorithms were implemented on an Nvidia GPU for acceleration.

The proposed method is inspired by DFM multi-scale pyramid DNNS matching. Given the feature vector sets and extracted from reference and sensed images, for an element from and another from , DNNS computes the distance between these two feature vectors. Only when the ratio between the best and second-best match distances is below a threshold do we preserve the coordinates of the feature vectors. These preserved coordinates are later processed by Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) to eliminate outliers. Apparently, the computation between all reference and testing pixels is extremely time-consuming. The multi-scale pyramid DNNS uses downsampling to improve efficiency. For example, an image with 1 m resolution is downsampled to 1/16 of the original size [14]; therefore, we can achieve a rapid matching result with an error of less than 8 m (half of the pixel interval), which is the search radius in the next level of the pyramid. At the next level, the downsampling factor is adjusted to 8, meaning we only have to search within one pixel (8 m) to find a more accurate position. This way, the result is gradually refined while the downsampling factor decreases from 16 to 1.

Considering our requirement for global registration is only to eliminate the initial offset, we modified the multi-scale pyramid DNNS to operate efficiently with minimal storage usage. Taking optical image registration as an example, the reference feature sampling step is set to 200 pixels, and the sensed feature sampling step is set to 10 pixels. Since the number of elements in and is severely unbalanced, we do not require matches to be mutual to retain as many points as possible. This fast registration typically results in a positioning error of approximately 10 pixels. Once global registration is complete, such a small search radius is acceptable for refinement. The local registration based on binary edge features uses NCC to match the database and sensed images [44]. The definition of NCC is given in Equation (9).

The subscripts R and S have the same meaning as in global registration. I denotes intensity, while and represent the mean and variance of the image cropped inside the window W. denote feature points locations detected in the sensed image, to avoid computing NCC at meaningless places. We shift the sensed image by changing dx and dy until the NCC coefficient reaches its maximum; then are considered the accurate locations for the pair , as denoted in Equation (10).

We strove to implement as many computationally intensive processes as possible on the GPU to save processing time. In the DNNS process, we partitioned GPU threads in a 2-D shape, and each thread had coordinates in the x and y directions. We used a two-dimensional GPU block to allocate one thread for each pair for parallel computing. Note that this step requires a certain amount of GPU memory to store float-type distances for all reference-sensed feature pairs. For a (10,000 × 10,000)-pixel image pair, the number of reference points is (10,000/200)2, while the number of sensed points is (10,000/10)2. Thus, it would take 4 × 2500 × 1,000,000 bytes (approximately 9 GB of GPU memory) to store all distance values. Afterwards, a one-dimensional GPU block sorts the distances for each vector in . For real satellite-grade embedded GPUs, our demand for 9 GB GPU memory can be easily meet. The Nvidia series is specially designed for edge computing, which has already been applied in satellites. Jetson Xavier NX/Orin NX edge device can provide 16 GB of GPU memory. There are also GPUs produced in China that provides 24 GB of GPU memory.

As for the NCC matching algorithm, it was already implemented on the GPU in our previous work. For a certain combination of translation , pixels in the template W, and each feature point , a separate thread is applied to compute NCC coefficients in parallel. This step has lower requirements on GPU memory since the features are all binary cropped images around feature points.

In summary, the on-board lightweight database provides moderate accuracy with low storage usage and high processing efficiency. We implemented the following measures:

1. We sampled features at fixed intervals on the histogram of the ASS index map to perform fast global registration with low storage usage.

2. We proposed a novel automatic main structure masking strategy for a lightweight edge database to enable accurate pixel-wise registration.

3. We applied a global-to-local two-step registration structure and GPU implementation to improve efficiency.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experimental Settings

In this section, we first present the evaluation results of the global registration database to verify its feasibility, followed by a comparative analysis between the overall proposed method and state-of-the-art approaches to demonstrate its effectiveness. It should be noted that for on-board processing, whose primary goal is to deliver target image slices to ground data centers for further analysis, positioning precision is not the foremost performance metric. To satisfy the stringent storage and real-time requirements of on-board systems, the proposed method achieves significant compression of the reference feature database. This design choice, while essential for operational feasibility, inevitably entails some reduction in accuracy.

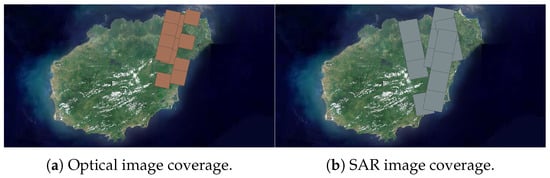

The original reference data covered the entire land area of Hainan Island and incorporated diverse feature types, which was downloaded from Google Maps at a resolution of 1 m. Google Maps might have seasonal variations, but the edge features can resist landscape changing to a certain extent. Google Maps are relatively accurate in geolocation, although they might have minor offsets, but the registration results are compared to original basemaps, which means the performance of experimental methods is not affected. Test datasets comprised both optical and SAR imagery, with 13 optical images acquired from Gaofen-2 (GF-2) at 1 m resolution and 13 SAR images obtained from Gaofen-3 (GF-3) in Ultra-Fine Stripmap (UFS) mode at 3 m resolution. The land coverage of reference and test images are presented in Figure 5. Each image was cropped into several patches as input data. The patch size was fixed to 10,000 × 10,000 pixels for optical and pixels for SAR imagery to simulate on-board processing conditions, as detailed in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Reference image coverage.

Table 1.

Details of testing data.

Since actual on-board hardware were unavailable for testing, all experiments were conducted on a ground-based server equipped with an Intel Core i7-9700K processor and an NVIDIA TITAN RTX GPU with 24 GB of memory. Although on-board devices differ from ground servers in computational capacity and GPU memory, this disparity does not affect the compatibility or validity of the proposed method, as the algorithm is designed to operate within typical embedded constraints. It is important to note that the feature extraction processes for the target image—used in global matching and fine matching, respectively—are mutually independent. Unlike typical sequential registration pipelines, where subsequent computations depend directly on prior results, the extraction of adjacent self-similarity (ASS) features and phase congruency features in our framework is entirely decoupled. On modern multi-core CPU platforms, these two extraction routines can be executed concurrently in a Linux environment. Consequently, when measuring total processing time, only the longer of the two extraction steps must be accounted for, representing an additional efficiency advantage of the proposed two-step framework. Regarding parameter settings, the suggested sparse sampling interval was set to 200 pixels for optical images. For SAR images, which generally exhibit lower resolution and reduced similarity to optical references, the suggested interval was reduced to 100 pixels to improve robustness. We also conducted experiments with different intervals as comparison.

4.2. Global Registration Results

In the global matching stage, precision was not the primary focus, provided that the result could confine the subsequent fine matching to a sufficiently small search radius (typically 10–20 pixels). Therefore, the most critical metrics in this phase were the feature extraction time for the sensed image and the storage footprint of the reference database. Among the compared methods, DFM, being based on a VGG model, is not applicable to SAR imagery. The RIFT method used in the optical experiment shares the same sparse sampling strategy as our proposed approach; however, its features lack sufficient similarity to ensure reliable matching on SAR images. Thus, in the SAR experiments, RIFT still relies on traditional keypoint detection. Both KAZE [45] and WSSF would also fail under a sparse sampling scheme. Moreover, unlike our method and RIFT—which use non-normalized histograms—WSSF and KAZE store floating-point feature vectors, demanding significantly more storage. Combined with their large numbers of detected keypoints, the storage requirements of these two methods would exceed even that of the original reference images. Consequently, for KAZE and WSSF, we used the original images as reference rather than storing a fixed set of detected keypoints. It should be noted that none of these comparative methods were originally designed with a lightweight reference database in mind.

The keypoint experiment results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. The successful rate metric refers to the percentage of global registration with an error of less than 10 pixels. The proposed method was significantly more efficient than the comparative methods, especially for large input image sizes. The ASS method consists of simple matrix computation, so it took little time for an image with a large size. The RIFT method required more time for multi-scale phase congruency computation. The KAZE method had similar time consumption for feature space establishment and keypoint extraction compared to RIFT, but generated more keypoints than the ASS method, thereby taking up more storage. The DFM and WSSF methods were extremely inefficient in comparison. For every control point in DFM, a image patch must be processed through VGG19, which is considerably time-consuming even with a high-end GPU. As for WSSF, it achieved the best accuracy in comparison, but both its efficiency and storage usage were unacceptable for on-board processing. In the original paper of WSSF, it was mentioned by the author that their method was very time-consuming even on smaller image patches, which fits our experimental results. The WSSF and KAZE methods are listed here to demonstrate that it is possible to achieve high accuracy through keypoint detection methods, but the storage cost and time usage of keypoint detection step could be severe. Similarly, the RIFT-SAR method also requires a keypoint detection step to function, but the int-type feature vectors result in less storage. Among the comparative methods, ASS had the best efficiency and lowest storage consumption. Although the accuracy was lower than comparative methods due to the proposed sparse sampling strategy, a registration error of less than 10 pixels was acceptable to subsequent refinement, which aligned with our expectation of global registration. To further demonstrate the setting of sampling intervals, we established the reference database with different intervals for the global registration. For the recommended settings (200 pixels for optical, 100 pixels for SAR), the proposed method was capable of stable registration with an error of less than 10 pixels. But when the sampling interval increased, some of the sensed images became unstable. A decreased sampling interval would not harm the registration accuracy or stability, but it would result in more storage usage. Since we implemented GPU parallelization for DNNS, the registration efficiency was hardly affected by different sampling intervals.

Table 2.

Optical global registration results.

Table 3.

SAR global registration results.

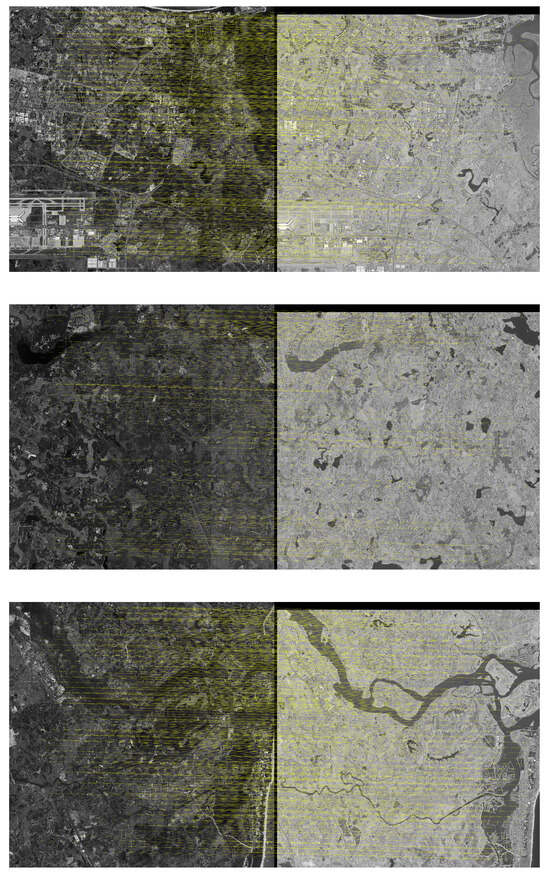

Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrates the global registration result of optical reference and SAR test images. In each scenario, the left side is the reference basemap, the right side is the sensed image, and the successfully matched points are connected with lines. The testing images cover a wide range of landscapes. Global registration is only stable when a large number of matching points appear. As shown in the figures, the matching points are spread evenly across the images regardless of imaging sensors, demonstrating the feasibility of the proposed strategy.

Figure 6.

Matching control points of global registration on optical images.

Figure 7.

Matching control points of global registration on SAR images.

In summary, ASS ensures consistent feature description between optical reference and SAR test images, as it is less affected by variations in imaging conditions, data sources, or sensor noise. Sampling at fixed intervals avoids the clustering of keypoints and enhances matching reliability. The extraction of ASS features is computationally efficient, while the use of HOG descriptors and a large sampling interval for reference images minimizes storage requirements. It should be noted that although keypoint-based methods—such as WSSF, KAZE (SAR), and RIFT-SAR—can achieve more accurate matching results than the proposed method, they still perform inferior to template-based registration in terms of overall robustness and applicability under the given constraints.

4.3. Overall Registration Results

After global matching, the localization error should be constrained within 10 pixels; therefore, the fine matching then requires only a minimal search range. The experiment conducted comparative analyses with three state-of-the-art methods, including OFM [46], ASTC [13], and MAGD [38], to validate the precision impact of database compression and efficiency achieved by the two-stage matching architecture. We also sued the CROP method, a variation of our previous work [39], where most distinguished patches from the testing images are cropped to establish a simple lightweight baseline. Note that the overall results of the proposed method refer to the global and local registration combined. Specifically, in our experiment in Hainan province, the optical reference basemap occupied 33.8 GB, while the global-matching reference database consumed 294 MB (optical) and 197 MB (SAR), and the fine-matching feature library required 520 MB for optical images at 1 m resolution and 65 MB for SAR images at 3 m resolution. Consequently, the proposed multi-source reference database achieved a total storage requirement of 1.05 GB.

The comparative experimental results are presented in Table 4. In terms of processing efficiency, the proposed method had comparable timeliness to the MAGD, since both employed a similar two-stage framework, while ASTC and OFM were significantly slower. The adoption of phase-congruency edge extraction in the proposed method took slightly longer than that of MAGD. Under identical hardware conditions, the proposed method had similar time consumption to the SOTA MAGD method, which demonstrates its efficiency. Regarding accuracy, while the MAGD method achieved optimal precision, our method demonstrated comparable performance to that of OFM and ASTC, with minor degradation attributable to reference feature compression. In actual on-board registration applications, the accuracy requirements typically range from 15 to 30 m, which could be easily met by the proposed method. As for the CROP method, since only small patches of the testing images were used for registration, it took up the least time among all methods, and the storage usage was only that of the original basemap. However, using small patches did not allow the method to perform accurate registration for the entire image, which is why the accuracy of CROP was significantly lower than comparative methods.

Table 4.

Overall experiment results.

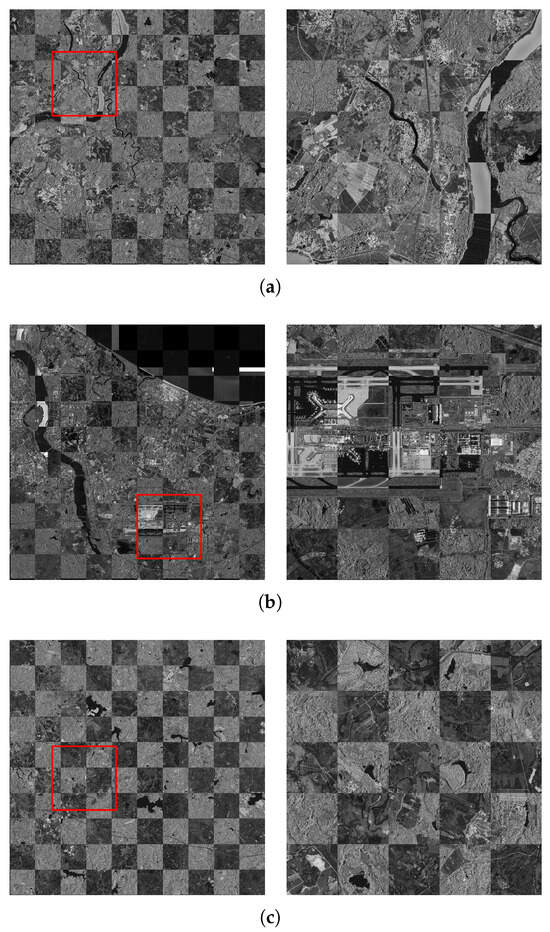

The chessboard of reference and calibrated images are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9. In each image, a patch is selected and enlarged for better visual effect. Most importantly, for storage requirements, these benchmark methods can only operate with original images as references, or their pixel-wise high-dimensional features already exceed the storage usage of reference images. In contrast, our solution achieves slightly inferior accuracy with less than of the original image storage usage. Considering that the storage of the reference database is significantly reduced, the proposed method achieves acceptable accuracy for on-board processing, while outperforming the comparative algorithms in the balance between storage and efficiency. Future research should focus on further enhancing accuracy and efficiency while maintaining the current compression rate of database storage.

Figure 8.

Overall registration results of the proposed method on optical images. (Left and right) columns are chessboards of whole images and enlarged patches in the red box. (a) scenario 1; (b) scenario 2; (c) scenario 3.

Figure 9.

Overall registration results of the proposed method on SAR images. (Left and right) columns are chessboards of whole images and enlarged patches in the red box. (a) scenario 1; (b) scenario 2; (c) scenario 3.

5. Discussion

In this paper, we proposed a lightweight reference database for on-board registration of remote sensing images. Although it met the storage, efficiency, and accuracy requirements of on-board registration, certain aspects could still be improved in future research. In this section, we discuss the limitations of the proposed method.

First, the terrain adaptability of the proposed method is examined. This capability is contrasted with existing studies and our earlier work, in which reference targets were largely confined to well-defined artificial structures such as airports, harbors, or buildings. Unlike these approaches, the proposed method does not depend on semantic definitions of reference targets, nor does it require prior open-source geographic vector data (e.g., OpenStreetMap) to delineate masks for such structures. Instead, a main-structure mask is automatically generated via the RTV model. As a result, the proposed method can be regarded as generally applicable, in contrast to earlier techniques. Nevertheless, certain limitations persist. The RTV mask does not fully differentiate heterogeneous landscapes, which can introduce redundancy into the reference database. Moreover, similar to most registration methods, the proposed approach performs poorly in weakly textured regions such as mountains, sea surfaces, forests, or deserts. As shown in Figure 10, reliable match points are obtained only around built-up areas, whereas mountainous or densely vegetated regions fail to produce sufficiently discriminative feature vectors.

Figure 10.

Failed registration in weakly textured region.

Deep learning-based methods are acknowledged as a major competing direction in current research; however, they present considerable drawbacks for on-board registration tasks. At present, the proposed method demonstrates advantages over neural descriptors in several key respects. First, it requires no labeled training data. Assembling a large volume of high-quality labeled data for global on-board registration would be costly and logistically difficult. Second, deep learning-based methods involve substantially higher computational complexity. Our method can be efficiently deployed on an on-board GPU with 16 GB of VRAM, while deep learning approaches generally demand significantly more memory and computational throughput to achieve efficient inference. Additionally, on-board systems would need to allocate extra storage for complex network models. Given these constraints, designing a viable on-board registration solution solely around deep learning remains challenging. The performance of the DFM method exemplifies these limitations. In future work, we intend to explore the use of deep learning-based techniques (such as variational autoencoders) to encode features into lower-dimensional representations, thereby enabling further reductions in storage footprint.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented a novel lightweight on-board database that substantially reduced storage requirements. The registration process operated on this compressed feature database instead of raw images, using a two-step framework to accommodate large initial geolocation offsets. For global registration, we introduced a sparsely sampled high-dimensional feature vector library that circumvented the keypoint repeatability issue while reducing the number of control points. For local registration, we replaced the earlier masking strategy with relative total variation (RTV) to filter out irrelevant features from the binary edge map. The optimized workflow employed parallelized GPU accelerated implementations for both registration stages, fully utilizing the available on-board computational resources.

Experimental results confirmed that the proposed method achieves superior database storage efficiency while maintaining SOTA accuracy and processing speed. Since existing comparative methods either demand excessive time or storage, none offer a practical solution for on-board registration. The principal contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

1. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first feasible lightweight on-board database designed for multi-sensor satellite image registration.

2. An advanced feature-compression strategy that is independent of terrain types. This includes a sparse sampling method for control points in global registration and an automatic main-structure ROI extraction procedure for local registration, both incurring only minor accuracy loss.

3. GPU-accelerated implementation for both registration steps, enabling efficient use of limited on-board hardware resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.; methodology, L.W.; software, L.W. and N.J.; validation, L.W. and N.J.; formal analysis, L.W.; investigation, L.W.; resources, G.Z. and H.Y.; data curation, L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review and editing, R.L., N.J. and H.Y.; visualization, L.W.; supervision, G.Z. and H.Y.; project administration, H.Y.; funding acquisition, R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by On-board Data Processing Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, under Grant E4M9082201.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. The Google Earth images were downloaded from the Google Earth platform. The GF-2 and GF-3 images were acquired from internal websites within Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. The authors also specifically thank Yuming Xiang and his team from Tongji University for their valuable contributions to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sweeting, M.N. Modern small satellites-changing the economics of space. Proc. IEEE 2018, 106, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusan, J.; Galica, C. Nasa’s cubesat launch initiative: Enabling broad access to space. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 157, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villela, T.; Costa, C.A.; Brandao, A.M.; Bueno, F.T.; Leonardi, R. Towards the thousandth cubesat: A statistical overview. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5063145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Li, Y. Embedded gpu implementation of sensor correction for on-board real-time stream computing of high-resolution optical satellite imagery. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2017, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, C.; Gonzalez-Llorente, J.; Cardenas, L.; Mendez, J.; Rincon, S.; Rodriguez-Ferreira, J.; Acero, I.F. Cloud detection autonomous system based on machine learning and cots components on-board small satellites. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, K.; Pan, C. Online target recognition for time-sensitive space information networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2017, 3, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; Wu, F.; Zhao, K.; Du, X.; Yang, C.; Zhong, R. On-Board Real-Time Ship Detection in HISEA-1 SAR Images Based on CFAR and Lightweight Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chi, Z.; Hui, F.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B.; Cheng, X.; Chen, Z. Accuracy Evaluation on Geolocation of the Chinese First Polar Microsatellite (Ice Pathfinder) Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, Q.; Yan, X.; Ren, W. Challenges for next generation micro-SAR: Lessons learned from China’s first light and small commercial SAR satellite-Hisea-1. In Proceedings of the EUSAR 2022; 14th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, Leipzig, Germany, 25–27 July 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, B.; Shi, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, L. On-board, real-time preprocessing system for optical remote-sensing imagery. Sensors 2018, 18, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y. On-board ship detection in micro-nano satellite based on deep learning and cots component. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Ye, Z.; Xu, Y.; Huang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, H.; Tong, X. Multimodal remote sensing image matching based on weighted structure saliency feature. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4700816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Mei, L.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y. Adjacent self-similarity 3-d convolution for multimodal image registration. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6002505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, U.; Ince, K.G.; Aydin Alatan, A. Dfm: A performance baseline for deep feature matching. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 4279–4288. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wan, L.; You, H. SAR-PC: Edge detection in SAR images via an advanced phase congruency model. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, N.Y.; Sukthankar, R. Pca-sift: A more distinctive representation for local image descriptors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Washington, DC, USA, 27 June–2 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, G.; Brown, M.; Winder, S. Discriminant embedding for local image descriptors. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–21 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Calonder, M.; Lepetit, V.; Fua, P.; Konolige, K.; Bowman, J.; Mihelich, P. Compact signatures for high-speed interest point description and matching. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 29 September–2 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jégou, H.; Douze, M.; Schmid, C. Product quantization for nearest neighbor search. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. 2011, 33, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingjin, H.; Guoqing, Z.; Xiang, Z.; Rongting, Z. A new fpga architecture of fast and brief algorithm for on-board corner detection and matching. Sensors 2018, 18, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, H.; Tuytelaars, T.; Gool, L.V. Surf: Speeded up robust features. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Computer Vision, Graz, Austria, 7–13 May 2006. Volume Part I. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Xiang, S.; Wang, M. On-board GCPS matching with improved triplet loss function. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, V-2-2020, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, X.; Li, C. Ground control point automatic extraction for spaceborne georeferencing based on fpga. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 3350–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhou, G.; Huang, J.; Zhang, R.; Shu, L.; Zhou, X.; Xin, C. On-board georeferencing using fpga-based optimized second-order polynomial equation. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, H.; Xie, Y. An efficient dual-channel data storage and access method for spaceborne synthetic aperture radar real-time processing. Electronics 2021, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingjin, H.; Guoqing, Z.; Dianjun, Z.; Guangyun, Z.; Rongting, Z.; Oktay, B. An FPGA-based implementation of corner detection and matching with outlier rejection. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 3, 8905–8933. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Chen, L.; Shi, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Long, T. FPGA-based implementation of ship detection for satellite on-board processing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 9733–9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, D.; Huang, J.; Baysal, O. Real-time ortho-rectification for remote-sensing images. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 40, 2451–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xiang, S.; He, L. Near Real-Time Automatic Sub-Pixel Registration of Panchromatic and Multispectral Images for Pan-Sharpening. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzerillo, G.; Valsesia, D.; Fiengo, A.; Magli, E. Compress-Align-Detect: Onboard change detection from unregistered images. arXiv 2025, arXiv:abs/2507.15578. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, M. Lightweight Design and Application of On-Orbit Image Control Points. Ph.D. Dissertation, Information Engineering University, Strategic Support Force, Zhengzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.; Fan, D.; Dong, Y.; Ji, S.; Li, D. A generation method of spaceborne lightweight and fast matching. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2022, 24, 15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z. A lightweight onboard basemap storage strategy. In Proceedings of the 10th China Command and Control Conference, Beijing, China, 7–9 July 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Fan, D. On-board lightweight image control point data generation method. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2022, 51, 413. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xing, F.; You, Z.; Zhong, X.; Qi, K. On-Orbit High-Accuracy Geometric Calibration for Remote Sensing Camera Based on Star Sources Observation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5608211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Long, H.; You, H. An Optical Remote Sensing Image Matching Method Based on the Simple and Stable Feature Database. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, F.; You, H.; Qiu, X.; Fu, K. Detector-free feature matching for optical and SAR images based on a two-step strategy. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5214216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; You, H.; Hu, Y. On-board geometric rectification for micro-satellite based on lightweight feature database. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Jin, G.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, K. Robust registration algorithm for optical and SAR images based on adjacent self-similarity feature. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5233117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yan, Q.; Xia, Y.; Jia, J. Structure extraction from texture via relative total variation. ACM Trans. Graph. 2012, 31, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Q.; Ai, M. Rift: Multi-modal image matching based on radiation-variation insensitive feature transform. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 3296–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiang, Y.; You, H.; Qiu, X.; Fu, K. A robust multi-scale edge detection method for accurate SAR image registration. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 4006305. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Q.; Zha, A.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Onishi, M.; Lei, L.; Er, M.J.; Maruyama, T. Efficient stereo matching on embedded GPUS with zero-means cross correlation. J. Syst. Archit. 2022, 123, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourfard, M.; Hosseinian, T.; Saeidi, R.; Motamedi, S.A.; Abdollahifard, M.J.; Mansoori, R.; Safabakhsh, R. Kaze-SAR: Sar image registration using KAZE detector and modified surf descriptor for tackling speckle noise. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5207612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Wang, M.; Pi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H. A robust oriented filter-based matching method for multisource, multitemporal remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4703316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.