Abstract

Accurate colorimetric quantification presents a significant challenge, as traditional imaging technologies fail to resolve metamerism and even hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is compromised by nonlinearities and specular reflections. This study introduces a high-fidelity colorimetric system using cross-polarized HSI to suppress specular reflections, integrated with a Support Vector Regression (SVR) model to correct the system’s nonlinear response. The system’s performance was rigorously validated, demonstrating exceptional stability and repeatability (average ). The SVR calibration significantly enhanced accuracy, reducing the mean color error from to . Furthermore, when coupled with a Random Forest classifier, the system achieved 99.0% accuracy in discriminating visually indistinguishable (metameric) samples. In application-specific validation, it successfully quantified cosmetic color shifts and achieved high-precision skin-tone matching with a fidelity as low as . This study demonstrates that the proposed system, by synergistically combining cross-polarization and machine learning, constitutes a robust tool for high-precision colorimetry, addressing long-standing challenges and showing significant potential in fields like cosmetic science.

1. Introduction

Color is a perceptual phenomenon arising from the interaction of light with the physical properties of objects, specifically their manner of reflection, transmission, or emission [1]. While color perception is a subjective human experience [2], its foundation lies in the objective, measurable properties of light and its interaction with matter [3]. Precise color measurement and reproduction are pivotal across diverse scientific and industrial sectors, where obtaining objective, reliable data is essential for ensuring application-specific efficacy. These applications include factory quality inspection [4], maintaining the color of textile dyes [5], managing the color in digital photos [6], preserving and restoring works of art [7], and special uses in makeup and skin care [8]. The development of novel instrumentation for accurate color measurement holds significant scientific and practical value.

Spectrophotometers are widely regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for color measurement [9]. The other category is the imaging colorimeter [10]. It can obtain a very detailed reflection spectrum from a single point, thereby enabling the calculation of accurate color values, such as CIE XYZ and Lab* values. Its main disadvantage is that it cannot provide information about the whole area. Some surfaces are uneven in color or have complex patterns. Single-point measurement is not enough to show the color of the whole object. Traditional photo equipment, such as colorimeters or digital cameras, uses red, green, and blue (RGB) filters. For example, a colorimeter or a digital camera. They can quickly take two-dimensional images of an area. They are widely used in factory inspection and visual inspection [11]. These devices work by mixing various optical information. They imitate the way of human vision [12]. This means that they are inefficient at extracting detailed spectral information. The biggest problem with this method is the low spectral resolution. Metamerism occurs when two objects with different spectral reflectance curves appear to match under one specific illuminant but subsequently fail to match under a different illuminant [13].

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) technology provides an excellent solution to these problems [14]. This technology combines conventional images with spectral analysis, and can obtain two-dimensional spatial information and one-dimensional spectral information of objects at the same time, thus constructing a three-dimensional “Hypercube”. In this cube, each pixel point carries a complete and fine spectrum of reflected light. The spectrum usually covers the visible and near-infrared light bands. This unique “spectral fingerprint” information enables HSI to distinguish metameric samples, thus achieving a color measurement accuracy far exceeding that of conventional RGB cameras [15].

This special advantage makes HSI technology widely used in fields that require extremely high color accuracy. In the field of agriculture, Shao et al. used HSI technology to achieve nondestructive testing of tomato maturity and color value, thus establishing a quality grading system [16]. In terms of cultural relics protection, Liang et al. accurately identified the pigment components in ancient paintings and documents through this technology. These cultural relics gradually deteriorated over time [17]. This method can also show the hidden pictures under the surface, which provides a solid scientific basis for art restoration and authenticity identification. Zeng et al. pioneered the adoption of a standard color system to restore faded hyperspectral images through digital technology, which made the color reproduction extremely high, and significantly improved the computer restoration effect and realism of ancient murals [18]. In the field of textile and printing, HSI technology also plays a key role. It ensures the color consistency of different batches of products and accurately regulates the color quality of the printed materials [19,20,21]. All these successful applications confirm that HSI is a powerful tool for obtaining highly realistic color measurement data.

To fully leverage the potential of HSI, we must solve some major technical problems. The measurement accuracy of the HSI system mainly depends on two points: the hardware equipment that requires precision manufacturing and the extremely strict data calibration process. In actual measurement, several factors will seriously affect the accuracy of the final color measurement: the light source may be unevenly distributed in space, and the camera sensor may not respond linearly (nonlinear characteristics). Specular reflection will also cause interference. This poses a major challenge to slightly shiny objects such as skin or coatings—high light reflection will “overwhelm” the diffuse reflection component, which carries the true color information of the object. As a result, the measurement results will be seriously distorted [22].

The limitations of traditional linear calibration methods necessitate the adoption of advanced data-driven approaches. Recent studies in complex engineering systems, such as the fault detection of air handling units, have empirically demonstrated that machine learning models can effectively capture nonlinear behaviors from high-dimensional multisensory data [23]. Drawing a parallel to optical metrology, we employ Support Vector Regression (SVR) to model the complex relationship between hyperspectral signals and colorimetric values, leveraging its robustness against sensor nonlinearities.

This framework aligns with the design philosophy of hybrid Finite Element Method (FEM)-AI systems used in biomedical monitoring by integrating a physical constraint layer with a data-driven calibration. While traditional hybrid systems often embed complex forward physical models, our approach adopts a more lightweight architecture that prioritizes practical deployability and calibration efficiency. By utilizing cross-polarization to physically suppress surface glare, the system simplifies the input space for the SVR model. This synergistic “physical-algorithmic” design ensures high-fidelity colorimetry while maintaining the robustness required for rapid cosmetic and clinical applications.

To advance the state of the art in high-fidelity colorimetry, this work introduces a novel system defined by three unique contributions: (1) Optical Robustness: The integration of cross-polarization optics into HSI to physically suppress specular reflections and isolate the pure diffuse reflectance signal. (2) Algorithmic Accuracy: The application of SVR for machine learning-based nonlinear calibration, which significantly reduces the mean color error from to . (3) Application Breakthrough: Comprehensive validation demonstrating superior performance in minute color difference discrimination (99.0% accuracy) and high-precision cosmetic effect quantification, which directly addresses long-standing challenges in applied color science.

This study focuses on building and testing a HSI system using cross-polarization. The system is made to get very exact, measurable data about color. It uses a special light path with orthogonal polarization. This path stops shiny reflections from the surface. The signal it captures comes mostly from the light that scatters inside, which holds the real color details. A full calibration method was also set up. This method includes a nonlinear color calibration using SVR. The method’s goal is to make the system’s colors as true as possible [24]. This paper presents a comprehensive validation of the developed system. It looks at the system’s stability, repeatability, and accuracy. Two tough experiments were done. One was telling tiny color differences apart. The other was measuring makeup effects. These tests demonstrate the system’s advantages over traditional methods. They also prove it works well and has many uses as a tool for exact color checking.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Instruments

This study used a core measurement system, standard reference materials, and experimental samples. We describe these items below.

2.1.1. HSI System

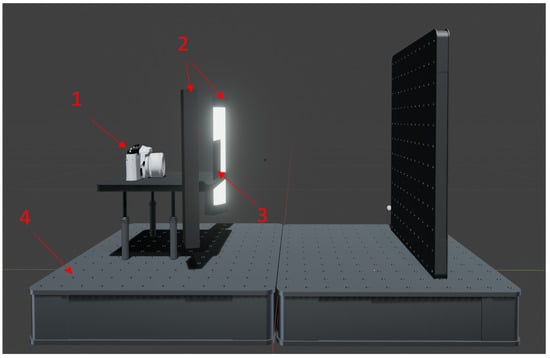

A cross-polarized HSI system was developed for this study, as shown in Figure 1. The system has these main parts:

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of HSI system structure: 1—hyperspectral camera; 2—polarized light source; 3—polarizing plate; 4—optical platform.

Hyperspectral Camera: A Specim IQ portable hyperspectral camera (Specim, Finland) was used. This camera has a push broom (line-scanning) imaging sensor. It covers a spectral range of 400–1000 nm. Its spectral resolution (FWHM) is 7 nm. It features 204 contiguous spectral bands. The sensor gives a 31° × 31° field of view (FOV). As a critical parameter for scene breadth, the FOV should be optimized based on the task—using wider views for holistic structures and narrower views for detailed feature extraction—to ensure data utility [25]. It takes pictures with a spatial resolution of 512 × 512 pixels. The system also incorporates a built-in RGB camera, which is used for real-time focusing and FOV positioning.

Illumination and Polarization Optics: The illumination component consisted of two LED polarized light sources (CST). We wanted to get rid of shiny spots (highlights) from the sample surface. We only wanted to capture the diffuse reflection. This reflection has the color information. A polarizer was put on the camera lens. This polarizer was turned at a right angle to the light source’s polarization. This setup created a cross-polarization optical path.

Mounting Platform: The whole experiment was set up on an optical platform. This kept it stable and in the same place while we took data.

2.1.2. Polarization Efficiency and Specular Quantification

The effectiveness of specular suppression in the cross-polarization configuration is primarily determined by the extinction ratio () of the employed linear polarizers. In the present system, manufacturer-specified polarizers with a nominal extinction ratio on the order of were used to attenuate surface specular reflections.

As a first-order engineering approximation, an upper bound for the residual specular leakage can be estimated based on Malus’s using Equation (1) while accounting for finite mechanical alignment tolerances ():

This estimation indicates that, under typical laboratory alignment conditions, the recorded hyperspectral signals are expected to be dominated by diffuse reflectance components, with residual specular contamination confined to the subpercent level. It is emphasized that this value represents a conservative upper-bound estimate rather than a directly measured quantity.

2.1.3. Experimental Samples

Standard Color Chart: The calibration target comprised 64 swatches from the PANTONE SkinTone Guide. Unlike offset printing, these lacquer-coated swatches ensure high spectral homogeneity and minimal metamerism without halftone dots. Derived from spectrophotometric measurements of diverse human skin tones under D65 illumination, the swatches served as physical targets while their official CIELAB values provided the numerical ground truth. This framework allows the SVR model to effectively compensate for minor physical deviations arising from production tolerances or substrate aging.

Standard White Panel: We used a standard white panel. It was made of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) with 99% reflectance (Spectralon, Labsphere, Inc.). The primary use of this panel is for white reference correction of hyperspectral images. This correction step helps to obtain physically significant reflectance data. When testing the stability of the system, we also used the panel as a standard target.

Cosmetic samples: We also want to verify the operation effect of the system in practical applications. We have selected two liquid foundation products, which can be purchased in a variety of stores. One of them is a dark foundation (Puadaier), and the other is a light foundation (Mabelline FIT ME, color number 102).

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing Pipeline

2.2.1. Hyperspectral Data Acquisition and Radiometric Calibration

Samples (e.g., color cards or skin) were positioned at the center of the camera field of view (FOV), and optimal focus was achieved via manual adjustment of the hyperspectral camera’s focus mechanism. The camera integration time was set to 20 ms, resulting in a total acquisition time of less than one minute per scan. This configuration provides a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) while avoiding image saturation and overexposure.

The hyperspectral images we obtained need to be preprocessed. The original data collected is not the real reflectance, but only the signal intensity captured by the camera sensor, reflecting the intensity values of different positions and different spectral bands. The accuracy of spectral data will be affected by many factors [26]. These include uneven lighting, the sensor’s own spectral response, and the thermal dark current that always happens during a capture. Radiometric calibration is very important. It changes the raw HSI data into real, physically meaningful reflectance data. This study used the common black-and-white correction method. It included the following capture steps.

Raw sample image (): The sample was placed on the imaging platform, and its raw hyperspectral data cube was acquired through spectral scanning.

White reference image (): After removing the sample, a standard 99% reflectance polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) white reference panel (Spectralon, Labsphere, Inc., North Sutton, NH, USA) was placed at the same position and scanned using identical acquisition settings. This measurement captures both the illumination characteristics and the spectral response of the imaging system.

Dark reference image (): Dark reference data were acquired by turning off the illumination and completely covering the camera lens with an opaque cap. This measurement characterizes the detector dark current at the specified integration time. To mitigate the influence of temperature-dependent dark current drift during prolonged operation, the dark reference image was re-acquired at hourly intervals, thereby ensuring consistency of the radiometric calibration baseline with the sensor’s evolving thermal state.

To eliminate systematic artifacts and ensure the metrological integrity of the spectral data, the raw hyperspectral images—initially recorded as digital numbers (DNs)—were converted into physically meaningful reflectance values. This radiometric calibration was performed on a pixel-wise basis using Equation (2):

By accounting for (white reference) and (dark current), this procedure effectively mitigates nonuniform illumination and pixel-specific sensor response variances, resulting in a standardized hyperspectral data cube where each pixel contains a reliable reflectance spectrum.

2.2.2. Data Processing and Colorimetric Parameter Calculation

Upon acquisition of the reflectance data cube, a post-processing pipeline was implemented using Python (version 3.9.21).

Region of Interest (ROI) Extraction: A program was made to mark an ROI. The mean reflectance spectrum was subsequently computed by averaging all pixel intensities within the designated ROI. This average became the spectrum used for that sample.

Spectral Truncation: To mitigate sensor noise in regions of low responsivity, the spectral range was truncated to 400–700 nm.

Color Difference Assessment: We needed to calculate color difference. We used the CIEDE2000 () color difference formula [27]. As a refined iteration of CIE76 and CIE94, this formula incorporates specific correction terms for lightness, chroma, and hue. The formula’s results are a better match for how people see color. This formula is shown as Equation (3).

Through this standardized procedure, the acquired high-dimensional hyperspectral data are transformed into internationally accepted, quantifiable colorimetric parameters.

2.3. Methods for Measurement System Performance Evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the HSI system developed in this study, three quantitative experiments were designed and conducted to assess measurement stability, repeatability, and colorimetric accuracy in a systematic and objective manner.

2.3.1. Stability Assessment

System stability was evaluated using the mean-range () control chart method, derived from Statistical Process Control (SPC) [28]. It was used to watch and check the system’s output over a specific time. The experiment took place in an optical darkroom where the temperature was controlled. A standard PTFE white panel was put in the center of the capture area. We turned on the camera and light sources. By implementing a 30 min preheating protocol, the system achieves the necessary thermal stability to mitigate fluctuations in both LED output and sensor sensitivity This proactive stabilization ensures a consistent physical baseline, which is critical for the reliability of the long-term stability monitoring and the precision of the colorimetric results. We collect images at fixed intervals, adopting a fixed integral time of 20 milliseconds. The sampling plan included 7 tests every half-day. This continued for a total of 1.5 days. Each test, comprising 3 images, constituted a subgroup (n = 3), yielding a total of 21 subgroups (k = 21).

An ROI of 100 × 100 pixels was selected from the center of the imaging area, and three representative spectral bands were analyzed independently: Blue (449.35 nm), Green (548.55 nm), and Red (598.60 nm). For each band, the mean () and range (R) of each subgroup were calculated. Then, the grand mean () and the average range () for all 21 subgroups were computed. These statistics were used to calculate the upper control limit (UCL) and lower control limit (LCL) for both the mean and range charts. The control chart is described by Equations (4)–(6) and the R control chart is described by Equations (7)–(9).

Mean Control Chart ( Chart):

Range Control Chart ( Chart):

Based on the control chart coefficient table for a subgroup size of , the coefficients , , and were used. The control charts were then plotted and analyzed. The measurement system is determined to be stable if all subgroup means () and ranges (R) fall within their respective upper and lower control limits.

2.3.2. Repeatability Assessment

Once system stability was confirmed, the study proceeded to evaluate short-term color repeatability. Repeatability refers to the system’s ability to mitigate random errors and yield consistent measurements [29]. The experiment utilized three representative color swatches from the PANTONE SkinTone Guide, corresponding to light, medium, and dark tones. Twenty hyperspectral images were acquired for each swatch in rapid succession under consistent environmental settings.

All collected data cubes were processed. The processing process adopts the method described above to convert the data cube into CIELAB color space coordinates. In order to verify the measurement consistency of a single color, we constructed a color difference comparison matrix, and each color sample corresponds to an independent matrix. Every element inside this matrix showed color difference values. This matrix was shown as a heatmap. This made it easy to see the internal variation. This variation came from the system’s repeated measurements of the same color swatch. This process validated its repeatability.

2.3.3. Color Calibration

While standard reflectance correction was performed, residual systematic bias may persist due to unaccounted experimental confounding factors. The system’s measured color values might not match the true colorimetric standards. This difference often comes from nonlinear problems built into the system. These problems can be in the camera sensor, the optical parts, and the color space transformation model. We wanted to make the HSI system’s color accuracy even better. A nonlinear color calibration model was created. This model was based on SVR.

The calibration target selected for this study was the PANTONE SkinTone Guide, which contains 64 precisely manufactured standard color swatches spanning light, medium, and dark tones. The ground truth CIELAB values for these swatches were obtained from the official Pantone Connect service. Subsequently, the HSI system was used to acquire images of these 64 swatches, and the data were processed to obtain the corresponding system-measured CIELAB values.

Three independent SVR models with Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernels [30] were constructed to map the system-measured values [, , ] to their ground truth counterparts. To ensure optimal generalization, hyperparameters (penalty C and kernel width ) were optimized via Grid Search with 5-fold Cross-Validation [31]. The search space was defined logarithmically: and . Calibration performance was evaluated using CIEDE2000 statistics (), with the primary criterion being a mean error below the human perception threshold (JND ). The optimized SVR hyperparameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Optimized SVR hyperparameters for each CIELAB channel.

2.4. Application Experiment Design

2.4.1. Evaluation of Hyperspectral Minute Color Difference Discrimination

Human vision and conventional RGB systems possess a limited ability to differentiate between samples that, while spectrally distinct, appear visually similar (a phenomenon known as metamerism or near-metamerism). This experiment was designed to assess whether the proposed HSI system can overcome this limitation. The objective is to evaluate the system’s capability to utilize its core spectral information to distinguish color samples that are visually indistinguishable.

For this study, five color swatches were intentionally selected from the PANTONE SkinTone Guide series. These swatches are visually indistinguishable to the human eye, defined by a pairwise color difference of less than 1.0 between two samples.

A “round-robin” method was used to collect the data. This approach helps to get more varied data. It also reduces the impact of possible changes over time on any single class [32]. The five target color swatches were placed one after another in the same spot. The imaging system captured each one. This whole sequence was called one round. This entire process was repeated 20 times. This gave a total of separate hyperspectral images.

To enhance model robustness and fully exploit the spatial information embedded within the hyperspectral images, a spatial segmentation strategy was employed [33]. A large “macro-Region of Interest” (macro-ROI) was defined at the geometric center of each color swatch. This macro-ROI was then partitioned into a grid, yielding 36 distinct “micro-ROIs.” These small areas were strictly nonoverlapping. This constraint was enforced to ensure the statistical independence of the extracted spectral samples and to prevent data redundancy, which is essential for an unbiased evaluation of the model’s classification performance. This grid-based sampling approach aligns with data augmentation strategies used in the analysis of spatially heterogeneous surface signals. Recent studies on sEMG signal processing have demonstrated that data augmentation is essential for handling nonstationary and complex signal patterns, significantly improving the classification accuracy of models [34]. Similarly, by segmenting the ROI into 36 micro-ROIs, we implement a form of spatial augmentation that prevents the model from overfitting to global averages and enhances its robustness against local surface texture variations. The average reflectance spectrum was calculated within each micro-ROI and treated as an independent sample. This procedure expanded the original dataset of 100 hyperspectral images into a comprehensive dataset of 3600 spectral samples, thereby capturing subtle colorimetric variations across the sample surface.

To achieve robust discrimination between samples with subtle colorimetric discrepancies, a high-precision classification framework was implemented. The Random Forest (RF) algorithm was employed to classify samples with minute color differences [35]. The model was configured with 100 decision trees (n_estimators = 100) and utilized standard Scikit-learn default hyperparameters for node splitting and maximum depth. This configuration was selected because RF is inherently robust to high-dimensional spectral data; using default settings balances computational efficiency while mitigating the risk of over-parameterization. The input (X) consisted of reflectance spectral vectors spanning the 400–700 nm range, and the output (Y) represented the corresponding color swatch labels.

To ensure a rigorous evaluation and prevent data leakage due to the spatial correlation of adjacent micro-ROIs, an image-grouped 5-fold cross-validation strategy was implemented. Crucially, the data split was conducted at the level of the original physical images, ensuring that all 36 micro-ROIs derived from a single capture were assigned exclusively to either the training or test set. This constraint guarantees that the model is evaluated on entirely unseen physical captures, providing an unbiased assessment of its generalization capability. Model performance was quantified using overall accuracy, confusion matrices, precision, recall, and F1-scores.

2.4.2. Cosmetic Effect Validation and Color Matching

To simulate real-world scenarios of cosmetic selection and application, this experiment was designed to evaluate the system’s comprehensive performance in quantifying instantaneous makeup effects and performing personalized color matching. It should be noted that this phase of the study serves as a preliminary proof-of-concept validation. Accordingly, a single subject participated in the experiment to demonstrate the operational feasibility of the proposed measurement workflow.

A flat, uniform region on the outer forearm was selected as the experimental test site. HSI was used on the bare skin in this area. No product was applied. This scan gave us the basic CIELAB color space values. We named this the “target skin color.” This color was also checked against the PANTONE SkinTone Guide library. This check was to find the “best-match swatch” in theory.

Two separate test areas were then marked on the forearm. We applied equal amounts of two liquid foundations. Each foundation went on its own area. They were spread on evenly. One was a dark-toned foundation (Puadaier). The other was a light-toned foundation (Maybelline, shade 102). HSI was performed right after they were applied.

The color changes from both foundations were measured using data and charts. These colors, after the makeup was on, were compared to the “best-match swatch.” This “best-match swatch” was the one found earlier in the PANTONE SkinTone Guide. The comparison was carried out in two ways: naked eye observation and color difference analysis (CIEDE2000). This process clearly quantifies the instant makeup effect of the product, and at the same time shows the performance ability of the system in practical application.

2.5. Spectral Jitter Analysis

To evaluate the sensitivity of the classification model to sensor-induced uncertainties, a spectral jitter analysis protocol was established. We simulated varying levels of measurement noise by injecting additive Gaussian white noise, , into the normalized reflectance spectra of the test set. The standard deviation was varied across seven levels: , corresponding to SNRs ranging from ∞ down to 10:1. The model was trained on the original clean dataset and subsequently evaluated on the noisy test samples to determine the critical SNR threshold for reliable discrimination between metameric classes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Measurement System Performance

3.1.1. Stability

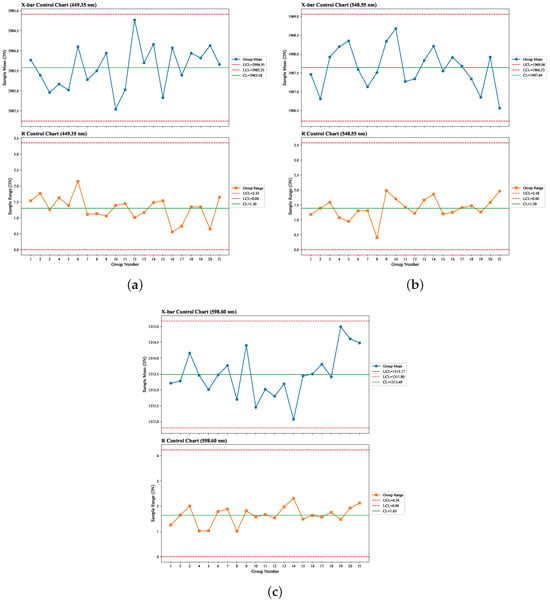

The stability of the HSI system was evaluated by monitoring its continuous operation over 1.5 days. A mean-range () control chart analysis was employed, based on 21 data subgroups acquired from the standard white panel. To comprehensively assess the system’s performance across different spectral regions, three specific spectral bands were analyzed independently: Blue (449.35 nm), Green (548.55 nm), and Red (598.60 nm). The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Process stability control charts for the HSI system: (a) 449.35 nm; (b) 548.55 nm; and (c) 598.60 nm. Each panel shows the sample mean () and range (R) values for 21 subgroups.

As observed in the charts, all 21 subgroup mean () and range (R) data points fell within their respective upper and lower control limits. The points are distributed randomly and do not exhibit any nonrandom abnormal patterns. This result indicates that the system possesses excellent long-term operational stability and is capable of acquiring high-quality, comparable data.

3.1.2. Repeatability

To assess the system’s short-term measurement repeatability, 20 consecutive hyperspectral images were acquired for each of three representative PANTONE SkinTone Guide swatches (light, medium, and dark). The resulting pairwise color difference (CIEDE2000) comparison matrix for each swatch is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Color repeatability difference matrices for the HSI system on single color swatches: (a) light swatch; (b) medium gray swatch; and (c) dark swatch.

As shown in the figure, all three heatmaps exhibit exceptionally low overall color difference values, indicating that the color discrepancy between any two of the 20 consecutive measurements was minimal. The average repeatability color difference () for all three swatches was less than 0.1. The repeatability errors for the medium gray and dark swatches were slightly higher than that for the light swatch. This observation is consistent with the general principles of optical measurement: at lower reflectance levels, fewer photons are received by the sensor, resulting in a reduced SNR. This, in turn, leads to relatively larger random fluctuations in the measurement data [36]. These values are still much smaller than the threshold of human color perception. This demonstrates the system’s ability to mitigate random errors. It gives measurement readings that are very steady. This makes the system more precise than what human eyes can perceive.

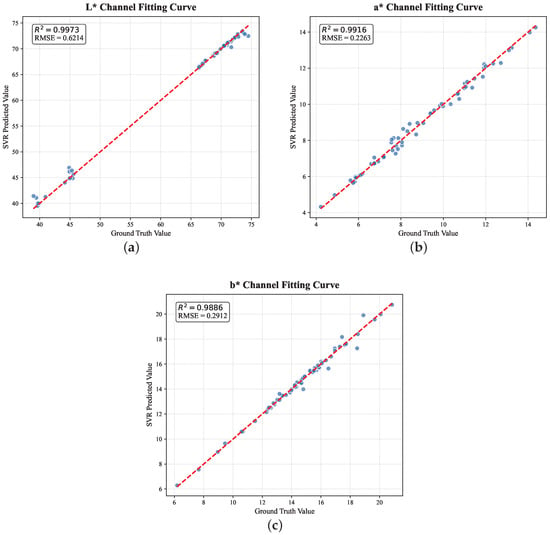

3.2. Color Calibration Performance

This study built a nonlinear color calibration model with SVR. Figure 4 shows how well the model fits. The statistical performance metrics, including the coefficient of determination () and root mean square error (RMSE), are summarized in Table 2. The R-squared (R2) [37] values for the L*, a*, and b* channels were all higher than 0.988. This calibration significantly improved the color accuracy. Table 3 summarizes these improvements. The mean color difference () was substantially reduced from 4.36 to 0.43, and the maximum color difference decreased dramatically from 10.18 to 2.18. These results fully demonstrate that an effective machine learning calibration model can successfully compensate for nonlinear errors within the complex system, thereby ensuring the accuracy of the final color data.

Figure 4.

Fitting performance of the SVR calibration models for each CIELAB channel: (a) channel; (b) channel; and (c) channel. The red dashed line represents the 1:1 reference.

Table 2.

Goodness-of-fit of the SVR regression models.

Table 3.

Color error metrics before and after calibration.

Standard radiometric calibration relies on the linearity of the sensor response between the dark reference and the white PTFE target. However, the significant spectral disparity between the high-reflectance white target (≈99%) and lower-reflectance samples (such as skin or cosmetics) often introduces systematic errors due to residual sensor nonlinearity and optical stray light. This is reflected in the high ’Pre-Calibration’ error () shown in Table 3. The proposed SVR model explicitly mitigates this limitation by establishing a nonlinear mapping based on the PANTONE SkinTone Guide. These colored swatches act as intermediate spectral references, effectively bridging the dynamic range gap between the white panel and biological samples, which explains the substantial accuracy improvement to .

Beyond the statistical metrics presented above, a critical concern in machine learning calibration is the risk of overfitting to the training targets. In this study, the application experiment on human skin (Section 3.3.2) serves as a rigorous external validation. Although the SVR model was trained solely on industrial lacquer coatings, it successfully achieved a high-fidelity match (, as discussed in the later application experiment), on biological tissue, which possesses fundamentally different optical textures. This successful generalization confirms that the optimized parameters () have effectively modeled the underlying instrument response rather than memorizing the specific features of the training dataset.

3.3. Application Experiment Results

3.3.1. Minute Color Difference Discrimination Capability

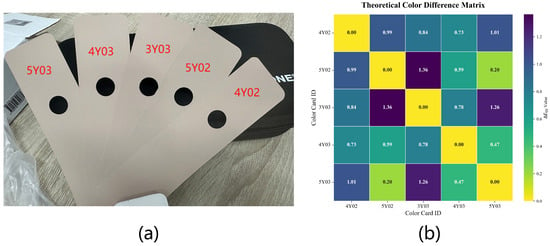

This experiment validated the performance of the HSI system, combined with machine learning algorithms, in distinguishing color samples that are visually indistinguishable. Following the methods described previously, a classification was performed on five PANTONE SkinTone Guide swatches (4Y02, 5Y02, 3Y03, 4Y03, and 5Y03) that are difficult for the human eye to differentiate. The physical photograph and the color difference matrix for these swatches are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

(a) Photograph of the five selected color swatches. (b) Theoretical color difference matrix for the selected swatches.

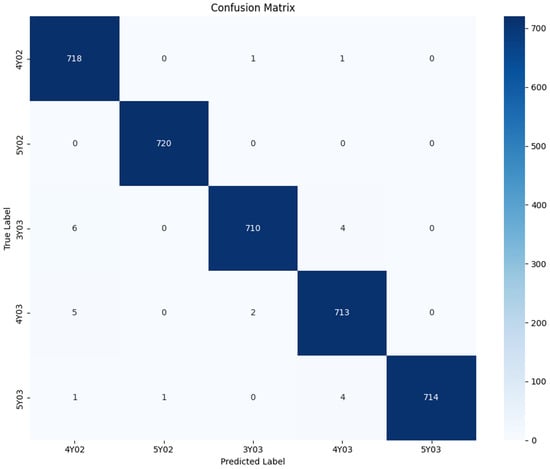

To obtain a reliable evaluation of the model’s generalization ability, this study employed an image-grouped 5-fold cross-validation strategy to eliminate the risk of data leakage. The Random Forest (RF) classifier demonstrated exceptional performance on the test sets, achieving an overall classification accuracy of 99.0%. The detailed classification performance is further presented in Figure 6 and Table 4.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix for the Random Forest classifier used for minute color difference discrimination. The diagonal elements represent the number of correctly classified samples.

Table 4.

Classification performance metrics for each class.

As shown in Figure 6, the confusion matrix [38] exhibits a nearly perfect diagonal form. The vast majority of samples were classified correctly, with very few misclassified samples (off-diagonal elements). This indicates that the model possesses an extremely high discriminative ability among the five visually similar classes.

As shown in Table 4, all five classes achieved exceptionally high scores (above 0.988) for precision, recall, and F1-score [39]. This demonstrates the model’s high-precision and well-balanced recognition capability across all categories.

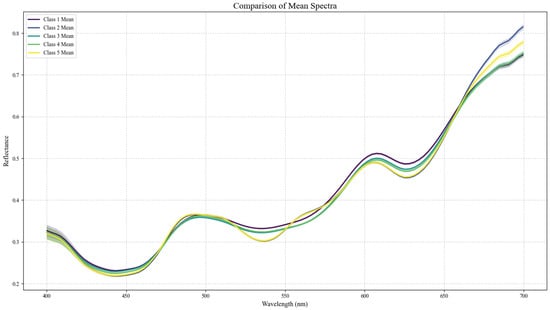

The classification is very accurate. This accuracy comes from the detailed physical information inside the hyperspectral data. Figure 7 helps explain this. The five color samples look almost the same to our eyes; in the visible spectrum, a person cannot tell them apart. Their spectral reflectance curves, however, tell a different story. These curves are like “fingerprints”: they show clear, steady differences in shape at many different bands. This finding strongly supports the system’s mechanism. It accurately reveals the operation mechanism of the system and can resolve the problem of “metamerism”, which is a known problem faced by conventional tristimulus vision. The system can deeply explore the spectral characteristics under the color appearance and realize high-precision material identification, and its performance far exceeds the ability of the human eye. It is difficult for the conventional RGB system to solve the metamerism problem easily, which highlights the core advantages of our new method.

Figure 7.

Average spectral reflectance curves for five color samples that look alike.

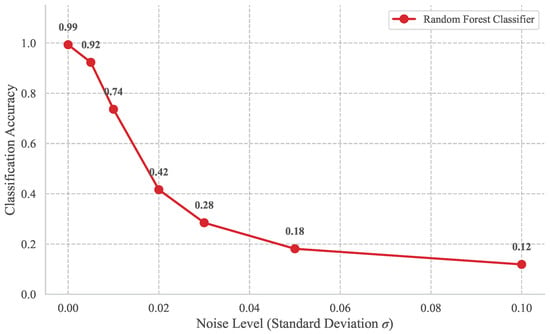

3.3.2. Spectral Jitter and SNR Robustness Analysis

To quantify the impact of sensor noise on classification performance, the results of the jitter analysis are presented in Figure 8. The Random Forest model maintains a high classification accuracy of at a noise level of (SNR = 200:1), demonstrating robust performance within the typical hardware noise floor. As the noise level increases to (SNR = 100:1), the accuracy decreases to . This sensitivity to noise levels exceeding is physically consistent with the subtle spectral discrepancies characteristic of metameric samples. The analysis underscores that the proposed system’s high-SNR hardware design and radiometric calibration are essential for capturing the stable spectral fingerprints required for successful discrimination.

Figure 8.

Robustness of the Random Forest classifier against spectral noise (jitter analysis).

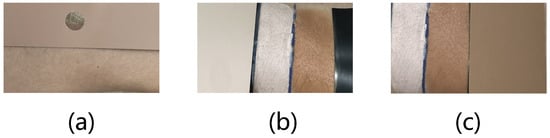

3.3.3. Subject Skin Makeup Effect Validation and Best-Match Swatch Analysis

This experiment was set up to check the system’s full ability. It measures quick makeup looks and judges personal color matching. The makeup effects from two different foundations were measured. The system’s match accuracy for these different color states was then checked. To measure the color changes brought on by the two foundations, we looked at the color gap. This gap was between the foundation-applied skin and the plain skin baseline color. Table 5 shows these results.

Table 5.

Color difference before and after foundation application.

The table shows the HSI system successfully measured the color changes. These changes came from the different foundations. The Maybelline foundation gave a color difference of 7.69 ( from the bare skin). It also made the lightness much higher. The Puadaier dark-toned foundation gave a color difference of 9.60. It made the lightness much lower. These results are perfectly consistent with what the products do (“whitening” and “tanning”). This shows the system is a viable tool: it helps check cosmetic results using objective, digital data.

Building upon the quantification of cosmetic effects, this study further validated the system’s ability to find the best matching swatch from the PANTONE SkinTone Guide for each color state (including bare skin and post-application skin). The system identified 2Y08, 1R05, and 1R11 as the best-match swatches for the bare skin, the Maybelline-applied skin, and the Puadaier-applied skin, respectively. Detailed matching results are presented in Table 6 (where the subscripts M and S denote the system-measured and standard swatch values, respectively) and Figure 9.

Table 6.

Analysis of subject skin color and best-match.

Figure 9.

Skin color and best-match swatches. (a–c) correspond to bare skin, Maybelline-applied skin, and Puadaier-applied skin, respectively.

As indicated by the table and figure, the system is capable of identifying the theoretically optimal matching swatch for skin under different color states; however, the matching accuracy varies. For the Maybelline-applied skin, the system achieved the lowest color difference () of 0.82. In contrast, the best-match color differences for bare skin and the Puadaier-applied skin were 1.56 and 2.97, respectively.

Importantly, there is significant variation in matching accuracy ( from 0.82 to 2.97). This is partly because the colors in the standard swatch library are spread out. This shows a basic problem in measuring color the old way. When foundation goes on skin, it does not just change the color; rather, it creates a new surface texture and gloss. CIELAB is great at measuring color. What people see is a mix of many things, i.e., color, shine, and feel. This whole impression is called “appearance.” A swatch might match the color numbers, but it can look different when shine and feel do not match the skin with makeup.

This involves a more complex scientific problem: how to build a single model to measure the overall appearance, including color, gloss, and texture. This is beyond the main goal of this study. This research focuses on achieving accurate color measurement and points out a very valuable direction for future research. The path means the use of HIS technology, which can not only measure color, but also extract and measure surface features, so as to achieve real full appearance matching and evaluation.

4. Conclusions

This study developed and comprehensively validated a new cross-polarization HSI system that was built for measuring color. Tests showed that the system is very stable over time, and exhibits high repeatability. It is better than what humans can see (mean repeatability ). This reliability builds a strong base for subsequent accurate measurements. The study also shows that nonlinear color calibration is required and the effect is remarkable. When we adopt the SVR model, the average color error of the measured flat results can be greatly reduced from 4.36 to 0.43. This also proves that machine learning is crucial, as it helps fix complex system errors and makes sure the colors look right.

The main achievement of this article is to demonstrate that the built system can distinguish colors, has a very high accuracy, and the recognition ability is better than the human eye. The system successfully distinguishes colors that cannot be distinguished by the naked eye through special spectral “fingerprint” data. The accuracy rate of its five indistinguishable color classification reaches 99.0%, breaking through the limitations of conventional tristimulus vision. This advantage has been verified in the actual test: the system transforms the “makeup effect” of the foundation—a subjective feeling—into an objective color value, and shows the potential to accurately match the individual’s skin tone. This establishes a novel digital metrology framework for the objective evaluation of cosmetic efficacy.

While this study demonstrates significant progress, we acknowledge certain limitations. First, regarding metrological traceability, the ground-truth relied on Pantone’s laboratory standards; although in situ calibration was not performed, newly purchased, light-shielded cards were used to mitigate drift. Second, this study serves as a proof of concept. By extracting intrinsic reflectance and standardizing calculations under D65 illumination, the system maintains high consistency across diverse skin types and lighting conditions. Future studies will involve broader demographics and traceable spectrophotometry. Third, the cosmetic application experiment was limited to a single subject and two specific products. This serves as a proof of concept to validate the measurement workflow and sensitivity. It does not constitute a generalized clinical validation, and statistical performance across diverse skin types and demographics remains to be established in future large-cohort studies. Fourth, the current calibration employs two-dimensional photometry based on a planar white reference, which may induce geometric errors when measuring curved surfaces (e.g., human faces).

Future work will focus on addressing these constraints by: (1) incorporating laboratory-grade spectrophotometric validation; (2) extending in vivo validation across a diverse spectrum of skin phototypes and ethnicities and developing 3D spectral calibration algorithms to correct for surface curvature; (3) integrating Bi-directional Reflectance Distribution Function (BRDF) models to move beyond suppressing gloss via polarization, enabling a more holistic assessment of skin appearance that includes both color and surface finish; and (4) exploring the integration of alternative data-driven approaches, such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), to provide uncertainty quantification for spectral characterization and improve the system’s interpretability in complex material analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and X.Y.; Methodology, Z.H., Y.G., and W.H.; Software, Z.H.; Validation, Z.H.; Formal Analysis, Z.H.; Investigation, Z.H.; Resources, L.L. and X.Y.; Data Curation, Z.H., Y.G., and W.H.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.H.; Writing—Review and Editing, Z.H., L.L., and Y.G.; Visualization, Z.H.; Supervision, L.L. and X.Y.; Project Administration, L.L. and X.Y.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the research project titled “Study on optical properties of spectral vision systems” and funded by Sun Yat-sen University, China under Grant 74130-71010023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Guangdong University of Technology (protocol code GDUTXS20250226 and date of approval: 19 November 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable guidance and academic support provided by Li Luo from the School of Physics and Optoelectronic Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology, China, and Xiangyang Yu from the School of Physics, Sun Yat-sen University, China, during the research and manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xiangyang Yu, Yuchen Guo and Weibin Hong was employed by the company Guangzhou Guangxin Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wyszecki, G.; Stiles, W.S. Color Science: Concepts and Methods, Quantitative Data and Formulae; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild, M.D. Color Appearance Models; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, R.W.G.; Pointer, M.R. Measuring Colour; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Park, B.; Kang, R.; Chen, Q.; Ouyang, Q. Quantitative prediction and visualization of matcha color physicochemical indicators using hyperspectral microscope imaging technology. Food Control 2024, 163, 110531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Chae, Y. Quantitative analysis of the color accuracy and reproducibility in digital textile printing: Discrepancies within color reproduction media. Text. Res. J. 2025, 95, 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žeger, I.; Grgic, S.; Vuković, J.; Šišul, G. Grayscale image colorization methods: Overview and evaluation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 113326–113346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L. Reintegration technique (Missing parts): In conservation-restoration of antiquities. Int. J. Archaeol. 2022, 10, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B.N.; Sun, M.; Ashbaugh, A.G.; Ohri, S.; Yeh, C.; Murrell, D.F.; Murase, J.E. Assessment of skin of color and diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: An analysis and call to action. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2021, 7, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, M.C.; Orellana Palacios, J.C.; Hesami, G.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Domínguez, R.; Moreno, A.; Hadidi, M. Spectrophotometric methods for measurement of antioxidant activity in food and pharmaceuticals. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanel, K.; Caglar, A.; Oezcan, M.; Gulsah, K.; Bagis, B. Assessment of color parameters of composite resin shade guides using digital imaging versus colorimeter. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2010, 22, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, R.G.; Santos, R.E.d.; Gaspar, R. Vision-based measurement for quality control inspection in the context of Industry 4.0: A comprehensive review and design challenges. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Li, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Zheng, Y. Visibility constrained wide-band illumination spectrum design for seeing-in-the-dark. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 13976–13985. [Google Scholar]

- Ludaš, A.; Glogar, M.I.; Ražić, S.E. Metamerism problem in the colour recipe calculation. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; Volume 1380, p. 012025. [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava, A.; Sachdeva, A.; Sharma, K.; Alsharif, M.H.; Uthansakul, P.; Uthansakul, M. Hyperspectral imaging and its applications: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. Hyperspectral imaging for clinical applications. BioChip J. 2022, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Ji, S.; Shi, Y.; Xuan, G.; Jia, H.; Guan, X.; Chen, L. Growth period determination and color coordinates visual analysis of tomato using hyperspectral imaging technology. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 319, 124538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H. Advances in multispectral and hyperspectral imaging for archaeology and art conservation. Appl. Phys. A 2012, 106, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, P.; Tang, X.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Hu, B. Virtual restoration of ancient tomb murals based on hyperspectral imaging. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistamah, N. The applications of artificial intelligence in the textile industry. In Artificial Intelligence, Engineering Systems and Sustainable Development: Driving the UN SDGs; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ingle, N.; Jasper, W.J. A review of deep learning and artificial intelligence in dyeing, printing and finishing. Text. Res. J. 2025, 95, 625–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziki, P.; Pieszczek, L.; Daszykowski, M. Toward more efficient and effective color quality control for the large-scale offset printing process. J. Chemom. 2024, 38, e3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artusi, A.; Banterle, F.; Chetverikov, D. A survey of specularity removal methods. Comput. Graph. Forum 2011, 30, 2208–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Evaluating cross-building transferability of attention-based automated fault detection and diagnosis for air handling units: Auditorium and hospital case study. Build. Environ. 2025, 287, 113889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shi, L.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, L.; Cui, X.; Gao, Y. Nondestructive detection for adulteration of panax notoginseng powder based on hyperspectral imaging combined with arithmetic optimization algorithm-support vector regression. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e14096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Development of approach to an automated acquisition of static street view images using transformer architecture for analysis of Building characteristics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, P.D.; Berns, R.S. Error propagation analysis in color measurement and imaging. Color Res. Appl. 1997, 22, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.R.; Cui, G.; Rigg, B. The development of the CIE 2000 colour-difference formula: CIEDE2000. Color Res. Appl. 2001, 26, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zanobini, A.; Sereni, B.; Catelani, M.; Ciani, L. Repeatability and reproducibility techniques for the analysis of measurement systems. Measurement 2016, 86, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramedani, Z.; Omid, M.; Keyhani, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Khoshnevisan, B. Potential of radial basis function based support vector regression for global solar radiation prediction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejuti, Z.A.; Islam, M.S. A hybrid CNN–KNN approach for identification of COVID-19 with 5-fold cross validation. Sens. Int. 2023, 4, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fürnkranz, J. Round robin classification. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2002, 2, 721–747. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, F.; Pratticò, D.; Angiulli, G.; Oliva, G.; Pullano, S.A.; Versaci, M.; La Foresta, F. Development of an Integrated System of sEMG Signal Acquisition, Processing, and Analysis with AI Techniques. Signals 2024, 5, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, R.; Bu, H. Research on pixel SNR of low light image sensor. In Proceedings of the AOPC 2024: Optical Devices and Integration, Beijing, China, 23–26 July 2024; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; Volume 13499, pp. 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Coefficients of determination for mixed-effects models. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2022, 27, 674–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, M.; Doyle, T.E.; Samavi, R. MLCM: Multi-label confusion matrix. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 19083–19095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Zhu, W. Precision–recall curve (PRC) classification trees. Evol. Intell. 2022, 15, 1545–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.