Abstract

The accurate determination of nuclear level density (NLD) is essential for a wide range of applications in nuclear science, including reactor design, nuclear astrophysics, and nuclear data evaluation. Traditional phenomenological models often face challenges in capturing key physical effects, such as collective excitations and shell structure, particularly in heavy and transitional nuclei, where the level density grows exponentially. Machine learning (ML) approaches have shown promise in improving predictive accuracy but are often limited by their purely data-driven nature, leading to challenges in interpretability and performance in regions with sparse experimental data. In this study, we propose a Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) framework, enhanced through multi-task learning (MTL), to address these limitations. The proposed model simultaneously predicts cumulative levels and mean resonance spacings by integrating experimental data with theoretical constraints, ensuring consistency with nuclear structure theory and robustness in extrapolating beyond the training data. Validation against both cumulative and yrast levels highlights the model’s ability to accurately capture rotational and vibrational excitations across a wide range of isotopes. Comparative evaluations demonstrate that the PINN model significantly outperforms traditional phenomenological models and purely data-driven approaches, offering a comprehensive and interpretable framework for advancing nuclear level density predictions and supporting practical applications in nuclear energy and astrophysics.

1. Introduction

Nuclear level density (NLD), defined as the number of excited states per unit energy interval, is a critical parameter in nuclear physics and nuclear engineering, playing a vital role in nuclear reactor design, nuclear astrophysics, and nuclear waste management [1]. Accurate predictions of nuclear level density are essential for reliable simulations and modeling of nuclear processes [2]. However, traditional theoretical approaches to calculating nuclear level density have faced significant challenges, particularly when dealing with complex, heavy nuclei. The nuclear level density is heavily influenced by collective effects, such as nuclear deformation and pairing correlations, which are often inadequately captured by traditional models like the Fermi gas model and other phenomenological approaches [3,4,5,6].

In addition to phenomenological level density models, combinatorial approaches have been extensively developed to describe nuclear level densities based on microscopic nuclear structure information [7]. These methods construct level densities by explicitly counting particle–hole configurations on top of mean-field single-particle spectra, often including pairing correlations and collective enhancements through rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom [8]. Notable examples include the Hartree–Fock–Bogoliubov plus combinatorial (HFB+C) models, which have demonstrated good predictive power across wide regions of the nuclear chart [9,10]. While combinatorial methods provide a more microscopic description than purely phenomenological models, they are computationally demanding, and their accuracy depends strongly on the underlying nuclear structure inputs, motivating the exploration of complementary data-driven and physics-informed machine-learning approaches.

Machine-learning techniques have also been extensively applied in nuclear mass modeling, which represents the most mature and widely explored application of data-driven approaches in nuclear physics [11,12,13,14]. A variety of methods, including kernel ridge regression, Bayesian neural networks, principal component analysis, Gaussian processes, and deep neural networks, have been successfully employed to improve mass predictions beyond traditional macroscopic–microscopic models [15,16]. These studies have demonstrated that machine learning can capture complex, non-linear correlations in nuclear data while providing enhanced predictive power, particularly for nuclei far from stability. The success of machine-learning-based nuclear mass models has motivated the extension of similar techniques to other nuclear observables, including nuclear level densities, where data scarcity and strong physical constraints pose additional challenges.

In recent years, machine learning (ML) techniques have garnered considerable attention in nuclear physics, offering the potential to improve the accuracy and efficiency of various applications [17,18,19]. Machine learning has been applied across diverse areas, including nuclear data evaluation [20,21], radiation transport [22,23], reactor physics [24], and nuclear astrophysics [11,13]. These advancements demonstrate the broad applicability and promise of ML in nuclear physics. Specifically, machine learning algorithms have been employed to calculate nuclear level densities, in order to uncover the underlying physics governing level density behavior [25,26,27,28]. Although these data-driven approaches have shown promise, their performance is fundamentally constrained by the availability and quality of training data [29,30]. Additionally, purely data-driven models may struggle to capture the fundamental physical mechanisms underlying nuclear level densities, particularly in scenarios where the data is sparse or incomplete. These models often lack interpretability, which poses challenges in deriving meaningful physical insights from their predictions [14].

In nuclear physics, where the adherence to fundamental physical principles is paramount, it is crucial to develop models that combine the predictive capabilities of machine learning with physics-based constraints and insights [31,32]. For nuclear level density calculations, this involves integrating knowledge about nuclear shell structure, pairing interactions, and collective effects into the machine learning framework. The complexity of heavy nuclei presents an additional challenge. As the nuclear mass increases, the nuclear level density grows exponentially, making both theoretical modeling and data-driven approaches increasingly difficult [1,33,34]. This exponential growth underscores the need for hybrid methodologies that merge physics-informed models with machine learning techniques. Such approaches can overcome the limitations of existing methods and provide more accurate and interpretable predictions [35,36].

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) offer a promising approach to addressing the challenges inherent in modeling nuclear level density. These models integrate prior knowledge about the underlying physical system directly into the neural network architecture, enabling predictions that are not only accurate but also physically meaningful, while preserving the flexibility and versatility of machine learning techniques [37]. By embedding the governing physics into the model, PINNs can outperform purely data-driven machine learning models, particularly in capturing complex phenomena such as collective effects and shell structure, which play a significant role in nuclear level density [1,3]. One of the key advantages of PINNs is their ability to quantify and propagate uncertainties in nuclear physics calculations. This capability is especially critical for applications that require reliable uncertainty estimates, such as nuclear data evaluation and astrophysical modeling [18,20,38]. Furthermore, by incorporating physical principles into their architecture, PINNs can help uncover previously unknown patterns and relationships within nuclear data, potentially leading to new insights and discoveries in the field [19,24,39]. PINNs also facilitate the integration of experimental data with theoretical models, offering a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of nuclear phenomena. This hybrid approach is particularly suited for studying complex systems such as nuclear level density, where combining experimental observations with theoretical insights can yield significant advances [25,28]. By leveraging both data-driven and physics-informed methodologies, PINNs provide a robust framework for advancing nuclear physics research and addressing the limitations of traditional approaches.

Multi-task learning (MTL) has emerged as a powerful machine learning paradigm, particularly for improving model performance by leveraging shared information across related tasks. Given the complex nature of nuclear level density (NLD), where collective effects, shell structure, and pairing interactions influence predictions, MTL provides a promising framework for jointly optimizing interrelated predictive tasks. By learning shared representations, MTL can enhance the model’s accuracy, efficiency, and robustness compared to single-task approaches. MTL has demonstrated success in various fields, including polymer informatics, computer vision, and engineering, where it has improved performance and scalability [40,41,42]. For example, in polymer informatics, MTL has enabled accurate predictions of multiple material properties while reducing data requirements [40]. Similarly, in engineering applications, integrating MTL with physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) has improved the modeling of complex physical systems [43]. Inspired by these advancements, we extend the MTL paradigm to nuclear physics by incorporating predictions of both the cumulative number of levels and mean resonance spacings within the same framework.

In our approach, MTL simultaneously predicts the cumulative number of levels as a function of excitation energy and the mean resonance spacings, both of which are critical for validating theoretical models against experimental data. The cumulative number of levels directly relates to the density of states, while the mean resonance spacings provide essential constraints derived from experimental measurements. By optimizing these related tasks jointly, the model benefits from shared physical knowledge, leading to improved predictions and enhanced interpretability. This approach ensures that the predictions of cumulative levels and resonance spacings are consistent with one another and grounded in the underlying nuclear structure. Moreover, the simultaneous prediction of both quantities helps to bridge the gap between theoretical calculations and experimental observations, making the model more reliable for practical applications in nuclear reactor design, astrophysics, and nuclear data evaluation. By leveraging MTL, we provide a robust framework for addressing the limitations of traditional approaches, improving both the accuracy of predictions and their consistency with physical reality.

In this paper, we propose a novel approach to predicting nuclear level density using a physics-informed neural network (PINN). Our method incorporates physical principles directly into the machine learning model to improve accuracy and interpretability, addressing the limitations of purely data-driven approaches. By leveraging a combination of theoretical insights, experimental data, and advanced preprocessing techniques, the proposed model effectively captures the influence of collective effects and shell structures on nuclear level density.

Although the present study primarily focuses on cumulative level distributions and neutron resonance spacings, these quantities are direct experimental manifestations of the underlying nuclear level density. In particular, the cumulative number of levels is related to the level density through , while mean resonance spacings provide a well-established constraint on the level density at the neutron separation energy. Consequently, comparisons based on cumulative levels and resonance spacings are widely used as practical and physically meaningful benchmarks for evaluating nuclear level density models, especially when direct differential level density data are unavailable or incomplete. For this reason, the term “nuclear level density” is used throughout the manuscript in its conventional sense, encompassing both differential densities and their experimentally accessible integral representations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the theoretical foundations of the PINN approach and details its implementation, including preprocessing and model architecture. Section 3 presents the results of our calculations, highlighting the performance of the model compared to traditional methods and purely data-driven models. Finally, in Section 4, we discuss the implications of our findings, along with potential applications and limitations, summarize the study, and outline directions for future research.

2. Methods

This section outlines the theoretical framework for nuclear level density (NLD) calculations and the implementation details of the Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) enhanced with multi-task learning (MTL). The approach combines analytical formulations with machine learning to simultaneously predict the cumulative number of excited states and mean resonance spacings.

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The foundation of our method lies in the Fermi gas model, which serves as the basis for many nuclear level density (NLD) formulations [33]. The nuclear level density quantifies the number of excited states per unit energy at a given excitation energy E and plays a central role in modeling nuclear reactions and decay processes. The general expression for the level density is given by:

where a is the level density parameter, U is the effective excitation energy, and denotes the spin cutoff factor, which accounts for the distribution of nuclear spins. The parameter a is critical for capturing the energy dependence of the level density and reflects the effects of nuclear structure, including shell corrections and pairing interactions.

Therefore, a key aspect of NLD formulations is accurately modeling the level density parameter a, which governs the variation of the nuclear level density as a function of the effective excitation energy U. The effective energy depends on excitation energy E as and accounts for corrections from pairing effects, ensuring that the model properly reflects the underlying nuclear structure. Here, denotes the back-shift parameter (in MeV), which accounts for pairing and shell effects by shifting the effective excitation energy as commonly used in back-shifted Fermi-gas type level-density formulations. Traditionally, is described using Ignatyuk’s formula, which introduces energy-dependent corrections to incorporate the influence of these effects [44]:

where is the asymptotic level density parameter at high excitation energies, represents the shell correction energy, and is a damping parameter controlling the transition to the asymptotic value. This formulation effectively bridges the low-energy and high-energy regimes by gradually incorporating the shell correction as energy increases.

To further enhance accuracy and account for collective effects such as rotational and vibrational excitations, a Laplace-like energy-dependent expression for can be used, as proposed in [3]:

Here, is the collective amplitude, is the energy of the first phonon state, and is the scale parameter of the Laplace distribution. This formulation ensures that collective effects are incorporated from the onset, significantly improving the model’s ability to predict level density distributions across different nuclei. By accounting for both shell corrections and collective phenomena, this approach provides a more comprehensive representation of the nuclear level density, particularly in heavy and deformed nuclei.

The cumulative number of excited states up to an excitation energy E is then calculated by integrating the total level density:

where represents the total level density for a given spin J and parity . This cumulative number of excited states provides valuable information for comparing theoretical predictions with experimental observations.

The mean resonance spacings , a crucial quantity in validating nuclear level density predictions, is defined by summing over all contributing nuclear spins at the neutron separation energy :

where I is the spin of the target nucleus before neutron capture. The mean resonance spacings reflect the density of states at and are experimentally derived from neutron-induced resonance data. These quantities serve as critical benchmarks for validating theoretical predictions of the nuclear level density and its effective parameterization.

In the present approach, no explicit parameters of Equation (1) are optimized. Rather than fitting model parameters such as level density parameters or back-shift energies, the neural network outputs the cumulative number of levels and mean resonance spacings directly. The agreement with experimental data from ENSDF is evaluated through data-driven loss terms, while physics-informed constraints are enforced implicitly through the choice of observables, monotonicity requirements, and task coupling within the multi-task learning framework.

In the present framework, the spin variable s is used as an input to condition the level density predictions, rather than being treated as a target for direct energy prediction; consequently, the model does not aim to predict excitation energies as explicit functions of spin , which lies outside the scope of level density modeling.

The training dataset consists of experimentally established nuclear level schemes and resonance spacing data compiled for medium and heavy nuclei across the nuclear chart. Structural properties () are available for all nuclei included in the dataset. Deformation parameters () and microscopic correction energies were obtained from widely used macroscopic–microscopic nuclear models and are available for all nuclei considered in this study. Excitation energies and spin assignments for discrete levels were extracted from evaluated experimental nuclear structure databases.

In total, cumulative level data were available for 1136 isotopes, while experimentally measured mean resonance spacings were available for 289 nuclei [45]. All input features used for a given nucleus were required to be simultaneously available; nuclei with missing deformation, microscopic correction, or excitation-energy information were excluded from the training dataset. This ensured a consistent and physically meaningful input space for the PINN model.

The dataset used in this study covers a broad region of the nuclear chart, including nuclei with proton numbers approximately ranging from up to , and corresponding mass numbers extending from light to heavy nuclei where experimental information is available. No explicit preference was imposed with respect to nuclear parity: the dataset includes even–even, odd–A, and odd–odd nuclei. All nuclei for which the required structural, deformation, excitation energy, and resonance spacing data were simultaneously available were retained, ensuring that the trained model captures general nuclear level density trends across different mass regions and pairing classes.

Nuclei with missing values in any of the required physical input features were excluded from the dataset to avoid introducing unphysical biases through imputation and to ensure consistency with the physics-informed modeling framework.

A standard training–validation split was employed, with 80% of the data used for training and 20% reserved for test and validation. No data augmentation techniques were applied, as the inputs correspond to physically well-defined nuclear properties and discrete experimental observations rather than images or stochastic signals.

2.2. PINN Model Architecture and Multi-Task Learning

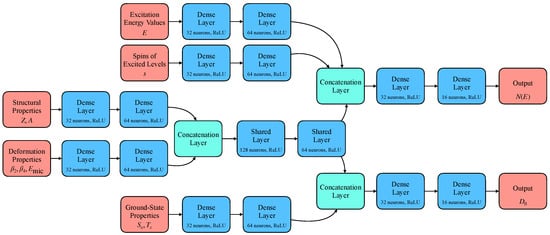

The proposed Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) model integrates theoretical constraints of nuclear level density directly within the learning framework by leveraging key nuclear properties as inputs. Figure 1 provides a detailed visualization of the proposed architecture, highlighting the flow from input features through dense layers, shared layers, and task-specific branches to the final outputs. As shown in Figure 1, the architecture consists of five input branches, each corresponding to critical features in nuclear physics: (1) structural properties comprising the proton number Z and mass number A, (2) deformation properties including the deformation parameters and along with the microscopic correction energy , (3) excitation energy E, (4) spin s, and (5) ground-state properties consisting of the neutron separation energy and the spin of the ground state of the isotope .

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed PINN architecture with multi-task learning. The diagram illustrates the input branches, shared feature extraction layers, and task-specific branches for predicting cumulative levels and mean resonance spacings .

Each input branch undergoes two dense transformations to capture relevant feature interactions before being concatenated to form a unified representation. This concatenated output is then passed through shared hidden layers designed to extract common patterns across these inputs, such as the influence of shell effects and collective excitations. The shared features are further processed by task-specific branches to predict (i) the cumulative number of excited states as a function of excitation energy and (ii) the mean resonance spacings , which serve as experimental validation for the theoretical predictions.

It should be emphasized that Equation (1) is not directly fitted to experimental data through adjustable parameters, as in traditional phenomenological level density models. Instead, the proposed PINN learns the mapping between nuclear properties and level density observables directly from experimental data, while Equation (1) serves as a physical reference that motivates the structure of the learning problem and the choice of observables.

To emphasize the physics-informed nature of the proposed architecture, each network component is designed to reflect distinct physical roles in nuclear level density modeling. The dense layers applied at the beginning of each input branch act as nonlinear feature extractors that capture correlations within a specific physical domain, such as global nuclear structure effects associated with Z and A, collective deformation effects encoded by and , or the excitation-energy and spin dependence of the level density. In this context, dense layers provide flexible, physics-inspired mappings rather than purely abstract transformations.

Concatenation layers are used to merge feature representations originating from different physical subsystems. These layers do not introduce additional trainable parameters; instead, they simply combine the outputs of multiple branches into a single feature vector. Consequently, the number of neurons in a concatenation layer is not specified explicitly, as it is determined automatically by the dimensionality of the incoming feature representations. From a physical perspective, this operation reflects the coupling of independent nuclear effects—such as shell structure, deformation, and threshold properties—into a unified description of the nucleus.

Following feature merging, shared layers are introduced to extract latent representations that are common to both prediction tasks. These layers encode physical information that simultaneously influences the cumulative number of levels and the mean resonance spacing , such as the global growth rate of the level density and its dependence on excitation energy and shell effects. The shared layers therefore enforce physical consistency between the two outputs, ensuring that both observables are governed by the same underlying nuclear structure information before diverging into task-specific branches.

Nuclear structure data, essential for accurately predicting nuclear level density, was collected by analyzing experimental discrete level schemes and resonance spacing measurements. The data acquisition process included gathering key nuclear properties such as proton number Z, mass number A, deformation parameters and , shell correction energies, and spin values from the Evaluated Nuclear Structure Data File (ENSDF) [45]. The discrete level schemes provided information on the cumulative number of excited states as a function of excitation energy, which is crucial for constructing the cumulative level distribution. The resonance spacing data, particularly the mean resonance spacings , was obtained by analyzing neutron-induced reactions in the relevant isotopes. This spacing reflects the density of levels near the neutron separation energy, serving as a key experimental benchmark for model validation.

The multi-task learning setup is realized by defining two output branches, each optimized using its respective loss function. The overall objective is expressed as:

where and represent the losses associated with cumulative levels and resonance spacings, respectively. The weighting factors are set to and . This selection reflects the fact that experimental cumulative level data is available for 1136 isotopes, whereas experimental values of mean resonance spacings are available for only 289 nuclei. By prioritizing the cumulative level predictions, the model leverages the larger dataset for improved generalization while still assigning sufficient weight to the resonance spacings to maintain accuracy in this critical region.

It should be emphasized that, unlike conventional PINN formulations where physical laws are enforced through explicit penalty terms added to the loss function, the physics-informed constraints in the present work are incorporated implicitly through the model architecture and learning strategy. The loss function in Equation (6) consists solely of data-driven terms associated with experimentally measured observables; however, physical consistency is enforced by (i) the selection of physically meaningful input features, (ii) the separation of these features into physics-motivated input branches, and (iii) the use of shared latent representations within the multi-task learning framework.

By simultaneously optimizing cumulative level distributions and mean resonance spacings—two observables governed by the same underlying nuclear level density—the model is constrained to learn representations that remain consistent with known nuclear structure behavior. In this sense, the physics constraints are applied in addition to the data loss through architectural and task-coupling mechanisms, rather than through explicit analytical penalty terms in the loss function.

In addition to the data-misfit terms, physics-inspired constraints are incorporated directly at the task-loss level. For the cumulative-level task, we penalize nonphysical negative predictions and use a relative-squared error to account for the large dynamic range of :

where is a large penalty coefficient enforcing . For the resonance-spacing task, we use a log-ratio loss (suited for positive quantities) and ignore entries where is unavailable:

computed over nuclei with .

The architecture’s design ensures that the shared representations help transfer knowledge between the two tasks, leading to enhanced prediction accuracy, particularly in regimes where experimental data is limited or sparse. The task-specific outputs benefit from this shared knowledge, yielding predictions that are consistent and interpretable within the context of nuclear physics.

To train the model effectively, the Adam optimizer was employed, using an adaptive learning rate schedule to enhance convergence. Regularization was applied through -norm penalties with a coefficient of in the shared and task-specific dense layers to control overfitting and improve generalization. Early stopping, with a patience parameter of 500 epochs, was utilized to terminate training when the validation loss ceased to improve, preventing excessive iterations that could lead to overfitting. Batch normalization was not included in the architecture; instead, the model relied on regularization and careful monitoring of the training process to maintain stability and achieve optimal performance.

The Adam optimizer was selected not only for its computational efficiency but also for its adaptive learning-rate mechanism, which is particularly well suited for multi-task learning problems involving heterogeneous loss terms with different scales. In preliminary experiments, alternative optimizers such as stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with momentum and RMSProp were also tested; however, Adam consistently demonstrated faster convergence and more stable training behavior across different random initializations.

The -norm regularization coefficient was set to based on empirical tuning aimed at balancing model flexibility and generalization. Smaller values were found to have a negligible effect on overfitting, while larger values led to underfitting and reduced predictive accuracy. The selected coefficient therefore, represents a compromise that effectively suppresses excessive weight growth without degrading model performance.

Careful monitoring of the training process involved tracking both training and validation losses for each task, as well as the combined multi-task loss. Early stopping with a patience of 500 epochs was employed to terminate training once no further improvement in validation loss was observed, ensuring that the final model parameters correspond to the best generalization performance, rather than the minimum training error.

To avoid information leakage between nuclei, the dataset was split at the isotope level, rather than at the individual data-point level. Unique combinations were divided into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets. All excitation-energy points associated with a given isotope were assigned exclusively to a single subset.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the performance evaluation of the proposed PINN model in predicting cumulative levels and mean resonance spacings. The effectiveness of the model is assessed using the goodness-of-fit estimator for cumulative levels and the root mean square deviation of the mean resonance spacings . Additionally, comparisons with traditional phenomenological models highlight the advantages of the proposed approach.

3.1. Model Evaluation Metrics

The predictive accuracy of the PINN model was assessed using two key evaluation metrics designed to capture different aspects of the model’s performance. The goodness-of-fit estimator for cumulative levels is defined as:

where represents the predicted cumulative number of levels up to excitation energy , and k denotes the index of each observed excited level for a given nucleus. This metric evaluates how accurately the model captures the cumulative distribution of excited states compared to experimental data, penalizing larger deviations. The root mean square deviation of the mean resonance spacings is given by:

where and are the predicted and experimental mean resonance spacings for the i-th nucleus, and N is the number of nuclei in the evaluation set. This metric quantifies the model’s ability to predict the density of levels near the neutron separation energy accurately, with smaller values indicating closer agreement between predicted and experimental spacings.

We note that Equations (9) and (10) quantify the data misfit for the resonance-spacing task; the physics-informed component of the training is introduced through physically motivated constraints (e.g., positivity penalties) and through multi-task coupling of and , rather than through an explicit differential-equation residual term.

Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance, addressing both the cumulative level predictions over a broad energy range and the accuracy of localized level density predictions near key thresholds such as the neutron separation energy.

3.2. Performance Comparison with Traditional Models

The performance of the proposed PINN model was evaluated in terms of its predictive accuracy compared to traditional phenomenological models. The comparison focused on two key metrics: , which measures the accuracy of predicted mean resonance spacings, and , which assesses the model’s ability to capture the cumulative distribution of discrete levels.

The PINN model’s performance was compared to well-known traditional models, including the back-shifted Fermi gas model (BSFGM), the composite Gilbert-Cameron model (CGCM), and the generalized superfluid model (GSM). Table 1 summarizes this comparison, highlighting the significant improvements achieved by the proposed approach.

Table 1.

Comparison of the predictive power of the proposed PINN model with traditional level density models. The covers 289 nuclei with experimental resonance spacings, and covers 1136 nuclei with available discrete level scheme data.

For the purpose of comparison, the same evaluation metrics used for the PINN predictions were also applied to the traditional level density models listed in Table 1. The cumulative level metric was calculated by comparing the predicted cumulative number of levels obtained from each traditional model with the corresponding experimental cumulative level distributions extracted from ENSDF. Specifically, represents the mean squared relative deviation between the predicted and experimental cumulative level counts over the excitation-energy range where discrete levels are available.

The resonance-spacing metric was computed by comparing the predicted mean resonance spacings from each traditional model with the experimentally measured values. Following standard practice, was evaluated as a logarithmic root-mean-square deviation, which penalizes multiplicative discrepancies and provides a robust measure of agreement over several orders of magnitude. In both cases, the same experimental datasets, energy ranges, and isotope selections were used for all models to ensure a fair and consistent comparison.

The improvement in demonstrates the PINN model’s superior ability to accurately capture the cumulative distribution of excited states by integrating theoretical constraints into the learning process. The reduction in highlights the model’s enhanced precision in predicting mean resonance spacings, which are crucial for applications in neutron-induced reactions and reactor design.

Unlike traditional phenomenological models that often struggle with large discrepancies due to their limited treatment of collective effects and shell structure, the proposed PINN model leverages multi-task learning and shared feature representations to overcome these limitations. This approach proves particularly effective in regions with sparse or incomplete experimental data, where the PINN model continues to generalize well.

Overall, the results in Table 1 confirm that the proposed PINN model significantly outperforms traditional models in both metrics, with notable improvements in . This advancement underscores the model’s potential to improve nuclear structure predictions and facilitate more reliable applications in nuclear energy and related fields.

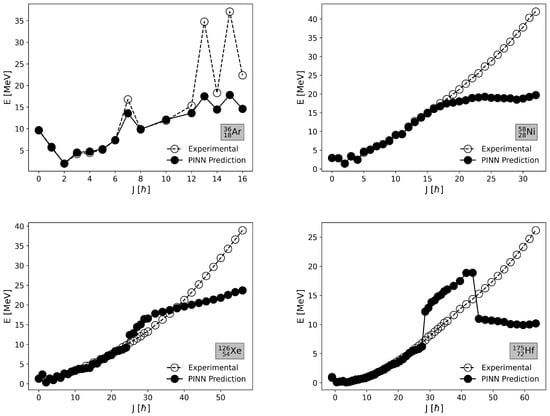

3.3. Evaluation of the Number of Cumulative Levels

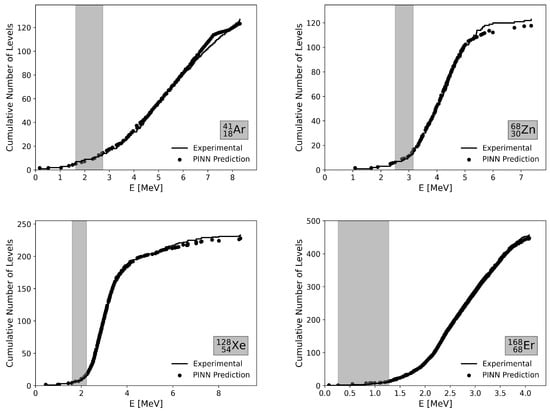

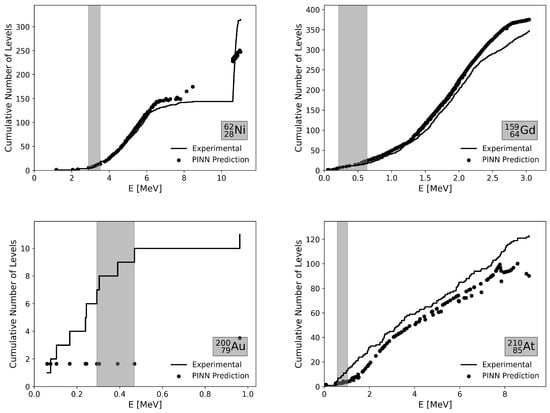

To evaluate the performance of the proposed PINN model in predicting the cumulative number of levels , we compare the model predictions to experimental data for selected isotopes. The isotopes were chosen from the 10 best and 10 worst cases, ensuring a balanced selection across light, medium, and heavy mass regions. The goodness of fit is quantified using the reduced chi-squared metric , defined as the contribution of a single isotope to the overall value. This metric evaluates the deviation between the predicted and experimental cumulative levels, providing a detailed insight into the accuracy of the model. Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the isotopes with the best and worst agreement, respectively, based on this metric.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the cumulative number of levels for the best-performing isotopes: 41Ar, 68Zn, 128Xe, and 168Er. The step function shows the experimental data, while the full circles represent the predictions of the PINN model. The gray rectangle indicates the – range typically used for phenomenological model fitting, which is not a restriction in our calculation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the cumulative number of levels for the worst-performing isotopes: 62Ni, 159Gd, 200Au, and 210At. The step function shows the experimental data, while the full circles represent the predictions of the PINN model. The gray rectangle indicates the – range typically used for phenomenological model fitting, which is not a restriction in our calculation.

In each figure, the step function represents the experimental cumulative number of levels, while the full circles represent the predictions of the PINN model. A gray rectangular region is shown in each plot, corresponding to the energy interval –, which is typically used for fitting phenomenological models. However, it is important to note that, in this study, we did not restrict the calculation of to the – range. Instead, we utilized all available discrete level data for a comprehensive evaluation.

The best-performing isotopes, including 41Ar, 68Zn, 128Xe, and 168Er, exhibit excellent agreement between the predicted and experimental cumulative levels across the entire excitation energy range. The low values in these cases suggest that the PINN model effectively captures key nuclear properties, such as deformation and shell effects, in regions where experimental data is reliable. The selected isotopes demonstrate how the model excels in accurately reproducing the cumulative level distributions when the underlying nuclear structure effects are properly represented.

The isotopes with the largest deviations—62Ni, 159Gd, 200Au, and 210At—present challenges primarily due to collective effects and structural complexities. In these cases, the discrepancies are more pronounced at higher excitation energies, where rotational bands and collective vibrations typically play a significant role. The inability to fully capture these effects results in the observed deviations, suggesting that further refinements in modeling deformation and rotational effects could improve accuracy. Additionally, the presence of shell closures in some isotopes might contribute to the error by altering the density of states in a way that is not fully captured by the current model formulation.

To further investigate the discrepancies observed at higher excitation energies in Figure 2, we analyzed the relative deviation between the predicted and experimental cumulative number of levels, defined as , as a function of excitation energy. This analysis reveals that the relative deviations are the largest at low excitation energies, where the cumulative number of levels is small and statistical fluctuations are inherently amplified. As the excitation energy increases and the number of observed levels grows, the relative deviation rapidly decreases and stabilizes around zero.

Importantly, no systematic increase of the relative deviation with excitation energy is observed. Instead, the discrepancies remain bounded and largely energy-independent at moderate and high excitation energies, indicating that the PINN model accurately captures the overall growth behavior of the cumulative level density. This suggests that the larger absolute differences at high energies seen in Figure 2 primarily reflect the cumulative nature of rather than a degradation of model performance.

Figure 3 focuses on a direct comparison between experimental data and PINN predictions in order to highlight the model’s ability to reproduce cumulative level schemes at the isotope level. Traditional phenomenological models, such as the back-shifted Fermi gas or constant temperature models, are typically calibrated over restricted excitation-energy intervals and are not designed to reproduce the detailed stepwise structure of experimental cumulative level distributions for individual nuclei.

For the nuclei shown in Figure 3, traditional models generally capture the global trend of level density growth but tend to deviate at low excitation energies, where shell effects and discrete structural features dominate, and near the upper end of the fitted energy range. In contrast, the proposed PINN consistently reproduces both the low-energy discrete behavior and the smooth transition to higher excitation energies without requiring nucleus-specific parameter refitting. Within the scope of this study, we do not observe cases where traditional phenomenological models systematically outperform the PINN approach across the full excitation-energy range considered.

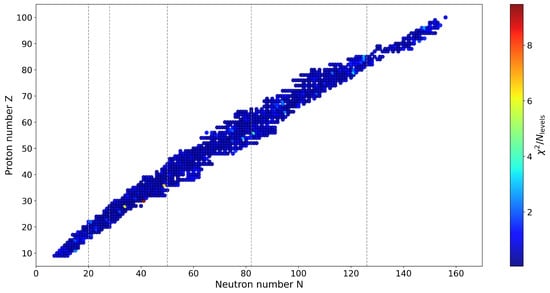

The selected isotopes demonstrate that the proposed PINN model generally performs well across a wide range of mass regions. While the model excels in predicting the cumulative level distribution for many isotopes, it also highlights challenging cases that offer valuable insights for further improvement. Figure 4 provides an overview of the error distribution across the nuclear chart, showing the values for all evaluated isotopes.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of the values across the nuclear chart. The size of the circles and the color intensity both indicate the magnitude of the errors, with larger, warm-colored circles (red and yellow) corresponding to higher errors and smaller, cool-colored circles (blue) indicating better agreement. The figure reveals regions of the chart where the model performance is optimal and regions where significant discrepancies exist.

As seen in Figure 4, the errors are generally lower in regions with well-established experimental data, particularly for nuclei with medium to large mass numbers and well-characterized deformation effects. The combination of the size and color coding provides a clear visual representation of the relative importance of the errors. Higher errors are observed near regions with shell closures and isotopes with pronounced collective behavior, such as those in the actinide region and transitional zones. This suggests that future improvements to the model should focus on better parameterization of collective modes, such as rotational and vibrational excitations, and refining the incorporation of shell effects.

By analyzing the distribution of errors, it is clear that the proposed PINN model provides valuable insights into nuclear structure, and addressing the challenging cases could lead to substantial advancements in predictive accuracy.

3.4. Validation Using Yrast Levels

In nuclear structure studies, validation against reliable experimental benchmarks is essential to ensure the accuracy and generalization of theoretical models. Traditional phenomenological models require validation to confirm that they properly capture nuclear properties like shell structure and collective excitations. When neural networks are employed, validation becomes even more critical—an obligation rather than a choice—due to the inherent data-driven nature of these models. Unlike purely physics-based models, neural networks rely heavily on training data to generalize to unseen cases, making them susceptible to overfitting or poor performance in regions with sparse or complex data. Therefore, validating the proposed PINN model using independent benchmarks such as yrast levels is vital to verify its robustness and reliability across diverse nuclear environments.

The yrast levels correspond to the states with the lowest energy for a given spin J. They play a significant role in nuclear spectroscopy as they govern the decay patterns and collective behaviors of nuclei. By validating against yrast levels, we can test the model’s ability to reproduce critical nuclear properties, such as rotational and vibrational modes, that are often prominent at higher spins.

The calculation of the theoretical yrast levels was performed using an iterative root-finding algorithm based on the Brent method [46], which combines bisection, secant, and inverse quadratic interpolation to efficiently find the roots of nonlinear equations. The goal of this method was to identify the excitation energy corresponding to the lowest-energy state at each spin J, known as the yrast level. For each isotope, we first sorted the discrete level data by spin and energy to identify the lowest experimental level for each spin J. This provided the reference “true” yrast energies. The corresponding predicted yrast energies were then obtained by solving the equation:

where represents the energy predicted by the model, and is the experimentally observed energy. The Brent method was chosen due to its robustness and efficiency in cases where derivative information is unavailable, as is common in energy level prediction. For each spin J, the root-finding algorithm iteratively refined the energy prediction within a specified tolerance of , ensuring convergence to the correct yrast energy or falling back to the initial energy estimate when convergence was not achieved.

By iterating over the spins for each isotope, we generated a set of predicted yrast levels that were compared directly to the experimental values. This approach efficiently accounted for cases where the energy landscape was complex or non-linear, providing accurate yrast energy predictions across a wide range of nuclear species.

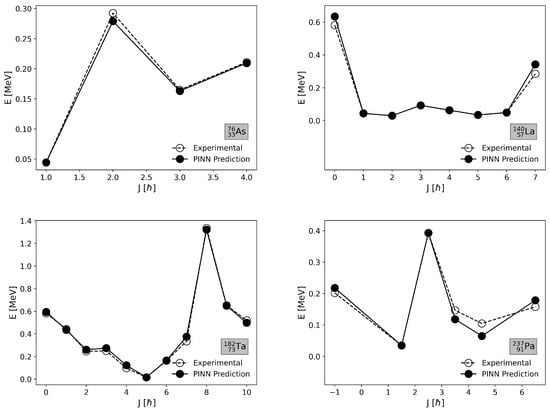

Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the comparison between predicted and experimental yrast levels for selected isotopes. In each plot, the open circles represent the experimental yrast energies, while the full circles correspond to the model predictions. The isotopes were selected based on their performance as determined by the mean absolute energy error across all spin values, with a balanced selection from different mass regions.

Figure 5.

Comparison of predicted and experimental yrast levels for selected isotopes with the best agreement: 76As, 140La, 182Ta, and 237Pa. The model successfully captures the yrast level trends, demonstrating excellent predictive accuracy across a wide range of spins and mass regions.

Figure 6.

Comparison of predicted and experimental yrast levels for selected isotopes with the worst agreement: 36Ar, 58Ni, 126Xe, and 175Hf. The discrepancies are more pronounced at higher spins, suggesting the need for improved treatment of collective effects.

For the best-performing isotopes—76As, 140La, 182Ta, and 237Pa—the model predictions align closely with the experimental values across the entire spin range. Minimal deviations are observed, particularly at both low and high spin states, indicating that the model effectively captures the underlying nuclear structure and rotational band progression. This accurate representation is especially notable for 182Ta and 237Pa, which involve complex deformation and rotational dynamics. The nearly parallel trends between the predictions and experimental values demonstrate the model’s robustness in capturing the gradual energy increase associated with rotational motion in deformed nuclei.

Conversely, the worst-performing isotopes—36Ar, 58Ni, 126Xe, and 175Hf—show significant discrepancies, particularly at higher spin states where collective rotational effects dominate. For example, in 36Ar and 58Ni, the model underestimates the energy at high spin values, reflecting limitations in the parameterization of shell effects and the onset of rotational bands. Similarly, for 126Xe and 175Hf, the deviations become more pronounced as spin increases, indicating challenges in accurately modeling the transitions from vibrational to rotational motion.

A common trend observed in the worst-performing cases is the divergence between the predicted and experimental values as spin increases. This highlights a potential area for improvement, specifically in refining the treatment of high-spin states, where centrifugal stretching and other collective effects become significant. Addressing these issues by incorporating more advanced deformation models or collective behavior approximations could enhance the model’s accuracy.

Overall, the results underscore the model’s general ability to predict yrast levels accurately for many isotopes while identifying cases where additional refinements are needed. The successful predictions for the best-performing isotopes suggest that the model handles nuclei with stable rotational properties well, but further optimization is necessary for isotopes with complex rotational-vibrational transitions or shell closures.

The relatively larger deviations observed for yrast energies compared to cumulative level predictions can be attributed to the fundamentally different nature of these observables. Cumulative levels represent integrated quantities that average over many excited states and are therefore statistically smoother and less sensitive to local structural fluctuations. In contrast, yrast energies correspond to specific lowest-energy states at fixed spin and are strongly influenced by detailed shell effects, deformation changes, and collective rotational dynamics. Additionally, the amount of experimental yrast data is significantly smaller than that of cumulative level schemes, limiting the model’s ability to constrain spin-dependent features. These factors collectively make yrast bands more challenging to reproduce with the same level of accuracy as cumulative levels.

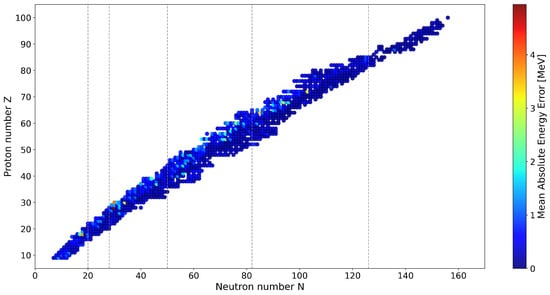

Figure 7 illustrates the general distribution of errors across the nuclear chart, where the size and color intensity of the circles indicate the magnitude of the mean absolute energy error. The heatmap highlights that isotopes located in regions with significant collective phenomena, such as transitional and deformed nuclei, exhibit larger errors. These regions typically involve the interplay of rotational and vibrational modes, shell closures, and deformation effects, which pose challenges for accurate modeling. The systematic pattern of errors suggests that further improvements in parameterization, particularly in regions dominated by collective excitations, could significantly enhance model performance. Refining the representation of high-spin states and accounting for centrifugal stretching effects are promising directions to mitigate the discrepancies observed in such nuclei.

Figure 7.

Heatmap showing the mean absolute energy error of the predicted yrast levels across the nuclear chart. Larger, warm-colored circles indicate higher errors, while smaller, cool-colored circles represent better agreement. The distribution highlights regions where the model performs well and areas requiring further refinement.

The validation using yrast levels demonstrates that the proposed PINN model effectively predicts yrast level trends for a diverse range of isotopes, accurately capturing the energy progression associated with rotational and collective modes in most cases. The close agreement for the best-performing isotopes highlights the model’s ability to handle well-characterized rotational bands, while the discrepancies in certain isotopes underscore the need for further refinements. Specifically, large errors at high spin states and in regions with complex collective behavior indicate that enhancing the modeling of rotational and vibrational modes, as well as improving the treatment of shell closures and deformation, is critical.

Future work will focus on integrating advanced theoretical models of collective motion, such as coupling vibrational and rotational modes, and optimizing the learning process to better represent high-spin phenomena. Additionally, expanding the training dataset with more experimental data and incorporating dynamic parameterization for transitional nuclei will further improve the model’s accuracy and robustness across the nuclear chart.

3.5. Discussion

The significant improvements achieved by the proposed PINN model, particularly in predicting cumulative levels and mean resonance spacings, underscore the advantages of incorporating theoretical constraints into the learning process. Unlike traditional models, which often rely on empirical parameter fitting with limited flexibility, the PINN model uses multi-task learning and shared feature extraction to simultaneously optimize both cumulative level and resonance spacing predictions. This enables the model to effectively capture the interplay of collective and shell effects that shape nuclear level densities across different mass regions.

Unlike general neural networks that rely purely on statistical correlations in the training data, the proposed Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) incorporates domain-specific physical knowledge directly into its structure and learning strategy. In conventional neural networks, all input features are typically processed through a single feedforward pathway, which can lead to overfitting and limited extrapolation capability, particularly in nuclear systems where experimental data are sparse.

In contrast, the proposed PINN explicitly separates input features according to their physical roles and enforces shared latent representations for multiple physically related tasks. The multi-task learning framework further acts as a regularization mechanism by requiring the network to simultaneously reproduce both the cumulative number of levels and the mean resonance spacing . This constraint promotes physically consistent representations and improves robustness when extrapolating to nuclei and excitation-energy regions not well covered by experimental data. These physics-informed design choices explain why the proposed PINN consistently outperforms general neural networks and traditional phenomenological approaches, as reflected in the quantitative comparisons presented in Table 1.

A key advantage of the proposed physics-informed framework is its enhanced capability to extrapolate to experimentally uncharted regions of the nuclear chart. In many nuclei—particularly those far from stability or at high excitation energies—experimental level schemes and resonance data are incomplete or entirely unavailable, posing a fundamental limitation for purely data-driven machine-learning approaches.

In the proposed PINN, extrapolation is supported by multiple physics-informed constraints. First, the separation of input features according to their physical roles ensures that predictions remain consistent with known nuclear structure trends, such as shell effects, deformation-driven collectivity, and the exponential growth of level density with excitation energy. Second, the shared latent representations enforced by the multi-task learning framework couple information from cumulative levels and resonance spacings, reducing the likelihood of unphysical predictions when extrapolating beyond the training domain.

As a result, the model does not rely solely on interpolation between neighboring data points but instead learns physically meaningful relationships that remain valid in regions with sparse or missing experimental data. This behavior is reflected in the model’s stable performance across a wide range of isotopes and excitation energies, including nuclei not explicitly used during training. Such extrapolation capability is essential for practical applications in nuclear data evaluation, reactor physics, and astrophysical modeling, where reliable predictions are required for nuclei and energy ranges that are difficult or impossible to access experimentally.

The model’s superior generalizability, demonstrated through accurate predictions for out-of-sample nuclei, highlights its practical utility in scenarios where experimental data is sparse or incomplete. This capability is particularly valuable for applications in nuclear reactor design, where precise knowledge of level densities is crucial for accurate cross-section calculations, and in astrophysical simulations involving nucleosynthesis processes. Furthermore, the successful prediction of yrast levels reinforces the model’s robustness in handling complex rotational and vibrational excitations, even in isotopes with intricate structural features.

Well-established nuclear reaction codes, such as TALYS, incorporate phenomenological and microscopic nuclear level density models and are widely used for cross-section and reaction-rate calculations. In the present work, we focus on a controlled and transparent comparison with representative phenomenological level density models, rather than a direct code-to-code comparison with TALYS, in order to isolate the impact of the proposed physics-informed learning strategy on level density observables. Since TALYS relies on internally implemented level density prescriptions, its predictions are ultimately governed by the same classes of models used for comparison in this study.

Overall, the proposed approach not only delivers substantial improvements in predictive accuracy, but also provides valuable insights into the underlying physics governing nuclear structure. These findings highlight the potential of PINN models as powerful tools for advancing nuclear theory and informing future experimental investigations.

Beyond its immediate scientific contributions, the proposed physics-informed neural network framework has the potential to serve a broad segment of the nuclear physics and engineering community. By providing fast and reliable predictions of nuclear level densities and resonance spacings, the method can support nuclear data evaluators, reactor physicists, and applied nuclear engineers who require consistent level-density inputs for reaction modeling and cross-section calculations.

Moreover, the data-driven yet physics-guided nature of the approach makes it suitable for integration into existing nuclear reaction codes and evaluation pipelines as a complementary tool, particularly in regions of the nuclear chart where experimental information is sparse or incomplete. From a wider perspective, the methodology may also benefit education and training by offering an accessible framework that connects nuclear structure theory with modern machine-learning techniques, thereby helping bridge the gap between traditional nuclear modeling and emerging computational approaches.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) with multi-task learning (MTL) as a powerful framework for predicting nuclear level density and related properties. By integrating theoretical constraints directly into the neural network architecture, the proposed model effectively addresses the limitations of traditional phenomenological approaches and purely data-driven machine learning methods. The model simultaneously predicts cumulative levels and mean resonance spacings, achieving significant improvements in predictive accuracy and interpretability compared to conventional methods.

The results highlight the model’s ability to capture key nuclear properties, including collective effects and shell structure, as demonstrated through accurate predictions of both cumulative levels and yrast levels across a diverse range of isotopes. The best-performing isotopes exhibited excellent agreement with experimental data, reflecting the model’s robustness in regions with well-characterized nuclear structure. Meanwhile, discrepancies observed in the worst-performing cases revealed areas where further refinements are necessary, particularly in high-spin states and regions with complex collective phenomena.

The heatmap analyses of the error distributions for both cumulative levels and yrast levels provided valuable insights into the regions of the nuclear chart where the model performs well and areas requiring further improvement. Larger errors were observed in transitional and deformed nuclei, emphasizing the need for enhanced parameterization of collective modes, rotational band progression, and shell effects.

Future work will focus on several key areas to further enhance the model’s accuracy and generalizability. These include refining the representation of high-spin states through improved modeling of rotational and vibrational couplings, integrating dynamic parameterization for nuclei undergoing structural transitions, and incorporating additional experimental data into the training process. Additionally, expanding the model to predict other nuclear observables, such as gamma-ray transition probabilities and neutron capture cross sections, could further enhance its applicability in nuclear reactor design, astrophysics, and nuclear data evaluation.

Overall, the proposed PINN model offers a comprehensive and interpretable approach to nuclear level density predictions, bridging the gap between theoretical nuclear structure models and experimental observations. Its success in accurately predicting both cumulative and yrast levels across various isotopes demonstrates its potential to advance nuclear theory, support future experimental investigations, and enable reliable applications in nuclear science and engineering.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Bora Canbula was employed by the company Canbula Sofware Research and Development Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Koning, A.; Hilaire, S.; Goriely, S. Global and Local Level Density Models. Nucl. Phys. A 2008, 810, 13–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goriely, S.; Larsen, A.C.; Mücher, D. Comprehensive Test of Nuclear Level Density Models. Phys. Rev. C 2022, 106, 044315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canbula, B.; Bulur, R.; Canbula, D.; Babacan, H. A Laplace-like Formula for the Energy Dependence of the Nuclear Level Density Parameter. Nucl. Phys. A 2014, 929, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassid, Y. The Shell Model Monte Carlo Approach to Level Densities: Recent Developments and Perspectives. Eur. Phys. J. A 2015, 51, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S.A.; Dehghani, V. Influence of Nuclear Deformation on Level Density Parameter. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2016, 31, 1650211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelevinsky, V.; Horoi, M. Nuclear Level Density, Thermalization, Chaos, and Collectivity. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2019, 105, 180–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilaire, S.; Goriely, S. Global microscopic nuclear level densities within the HFB plus combinatorial method for practical applications. Nucl. Phys. A 2006, 779, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen’kov, R.; Zelevinsky, V. Nuclear level density: Shell-model approach. Phys. Rev. C 2016, 93, 064304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goriely, S.; Hilaire, S.; Koning, A.J. Improved microscopic nuclear level densities within the Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov plus combinatorial method. Phys. Rev. C 2008, 78, 064307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goriely, S.; Hilaire, S.; Péru, S.; Sieja, K. Gogny-HFB+ QRPA dipole strength function and its application to radiative nucleon capture cross section. Phys. Rev. C 2018, 98, 014327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.P.; Wang, Y.J.; Lü, H.L.; Li, Q.F.; Shen, C.W.; Liu, L. Machine Learning the Nuclear Mass. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2021, 32, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Liang, H. Nuclear mass predictions with machine learning reaching the accuracy required by r-process studies. Phys. Rev. C 2022, 106, L021303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, E.; Soydaner, D.; Bahtiyar, H. Nuclear Mass Predictions Using Machine Learning Models. Phys. Rev. C 2024, 109, 064322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumpower, M.R.; Sprouse, T.M.; Lovell, A.E.; Mohan, A.T. Physically Interpretable Machine Learning for Nuclear Masses. Phys. Rev. C 2022, 106, L021301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, R.; Piekarewicz, J.; Prosper, H. Nuclear mass predictions for the crustal composition of neutron stars: A Bayesian neural network approach. Phys. Rev. C 2016, 93, 014311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, P. Predicting nuclear masses with the kernel ridge regression. Phys. Rev. C 2020, 101, 051301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.A.B.; Beh, H.G.; Shahrol Nidzam, N.N.; Chew, X.Y.; Ayub, S. Generation of Cross Section for Neutron Induced Nuclear Reaction on Iridium and Tantalum Isotope Using Machine Learning Technique. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2022, 187, 110306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Minato, F.; Kimura, M.; Iwamoto, N. Nuclear Data Generation by Machine Learning (I) Application to Angular Distributions for Nucleon-Nucleus Scattering. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, B.; Ren, R.; Cui, C. FECSG-ML: Feature Engineering for Nuclear Reaction Cross Sections Generation Using Machine Learning. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2024, 214, 111545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neudecker, D.; Grosskopf, M.; Herman, M.; Haeck, W.; Grechanuk, P.; Vander Wiel, S.; Rising, M.; Kahler, A.; Sly, N.; Talou, P. Enhancing Nuclear Data Validation Analysis by Using Machine Learning. Nucl. Data Sheets 2020, 167, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.; Kokalova, T.; Freer, M.; Wheldon, C.; Smith, R.; Walshe, J.; Soić, N.; Prepolec, L.; Tokić, V.; Marqués, F.M.; et al. The Identification of α-Clustered Doorway States in 44,48,52Ti Using Machine Learning. Eur. Phys. J. A 2021, 57, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, A.; Wainwright, H.M.; Sansavini, G. Machine Learning-Enabled Weather Forecasting for Real-Time Radioactive Transport and Contamination Prediction. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 173, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.; Pilania, G.; Couet, A.; Uberuaga, B.P.; Sun, C.; Li, J. Machine Learning in Nuclear Materials Research. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2022, 26, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhareef, M.H.; Wu, Z. Physics-Informed Neural Network Method and Application to Nuclear Reactor Calculations: A Pilot Study. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2023, 197, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdoğan, H.; Üncü, Y.A.; Şekerci, M.; Kaplan, A. Estimations of Level Density Parameters by Using Artificial Neural Network for Phenomenological Level Density Models. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2021, 169, 109583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.X.; Shang, T.S.; Geng, K.P.; Li, J.; Fang, D.L. Inference of Parameters for Back-shifted Fermi Gas Model Using Feedback Neural Network. Phys. Rev. C 2024, 109, 044325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Niu, Z.; Li, Z. Study of Nuclear Low-Lying Excitation Spectra with the Bayesian Neural Network Approach. Phys. Lett. B 2022, 830, 137154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Y. Uncertainties of Nuclear Level Density Estimated Using Bayesian Neural Networks. Chin. Phys. C 2024, 48, 084105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.H.; Ren, Z.X.; Zhao, P.W. Nuclear Energy Density Functionals from Machine Learning. Phys. Rev. C 2022, 105, L031303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, A.E.; Mohan, A.T.; Sprouse, T.M.; Mumpower, M.R. Nuclear Masses Learned from a Probabilistic Neural Network. Phys. Rev. C 2022, 106, 014305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnlein, A.; Diefenthaler, M.; Fanelli, C.; Hjorth-Jensen, M.; Horn, T.; Kuchera, M.P.; Lee, D.; Nazarewicz, W.; Orginos, K.; Ostroumov, P.; et al. Machine Learning in Nuclear Physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022, 94, 031003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.B.; Ma, Y.G.; Pang, L.G.; Song, H.C.; Zhou, K. High-Energy Nuclear Physics Meets Machine Learning. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2023, 34, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethe, H.A. Nuclear Physics B. Nuclear Dynamics, Theoretical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1937, 9, 69–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, T. The statistical model and nuclear level densities. Adv. Phys. 1960, 9, 425–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faroughi, S.A.; Pawar, N.; Fernandes, C.; Raissi, M.; Das, S.; Kalantari, N.K.; Mahjour, S.K. Physics-Guided, Physics-Informed, and Physics-Encoded Neural Networks in Scientific Computing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2211.07377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, J.; Jia, X.; Xu, S.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Integrating Scientific Knowledge with Machine Learning for Engineering and Environmental Systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G. Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Deep Learning Framework for Solving Forward and Inverse Problems Involving Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, G.; Sjöstrand, H.; Hansson, J.; Rochman, D.; Koning, A.; Capote, R. Conception and Software Implementation of a Nuclear Data Evaluation Pipeline. Nucl. Data Sheets 2021, 173, 239–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, T. Precision in Medical Isotope Production: Nuclear Model Calculations Using Artificial Neural Networks. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2024, 213, 111478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenneth, C.; Rajan, A.C.; Tran, H.; Chen, L.; Kim, C.; Ramprasad, R. Polymer informatics with multi-task learning. Patterns 2021, 2, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenhende, S.; Georgoulis, S.; Gansbeke, W.V.; Proesmans, M.; Dai, D.; Gool, L.V. Multi-Task Learning for Dense Prediction Tasks: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 3614–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yao, W.; Peng, W.; Zhang, X.; Bao, K. Physics-Informed MTA-UNet: Prediction of Thermal Stress and Thermal Deformation of Satellites. Aerospace 2022, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yao, J.; Wang, J.; Xie, X.; Ablameyko, S.V. Multi-Task Learning Enhanced Physics-Informed Neural Network for Solving Fluid-Structure Interaction Equations. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chongqing, China, 20–22 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatyuk, A.; Smirenkin, G.; Tishin, A. Phenomenological Description of Energy Dependence of the Level Density Parameter. Yad. Fiz. 1975, 21, 485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Evaluated and Compiled Nuclear Structure Data. 2024. Available online: https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/ensdf/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Brent, R.P. Some efficient algorithms for solving systems of nonlinear equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1973, 10, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.