Abstract

Blast-induced rock fragmentation plays a critical role in mining and civil engineering. One of the primary objectives of blasting operations is to achieve the desired rock fragmentation size, which is a key indicator of the quality of the blasting process. Predicting the mean fragmentation size (MFS) is crucial to avoid increased production costs, material loss, and ore dilution. This study integrates three tree-based regression techniques—gradient boosting regression (GBR), histogram-based gradient boosting machine (HGB), and extra trees (ET)—with two optimization algorithms, namely, grey wolf optimization (GWO) and particle swarm optimization (PSO), to predict the MFS. The performance of the resulting models was evaluated using four statistical measures: coefficient of determination (R2), root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). The results indicate that the GWO-HGB model outperformed all other models, achieving R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE values of 0.9402, 0.0251, 0.0185, and 0.0560, respectively, in the testing phase. Additionally, the Shapley additive explanations (SHAP), local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME), and neural network-based sensitivity analyses were applied to examine how input parameters influence model predictions. The analysis revealed that unconfined compressive strength (UCS) emerged as the most influential parameter affecting MFS prediction in the developed model. This study provides a novel hybrid intelligent model to predict MFS for optimized blasting operations in open-pit mines.

1. Introduction

Rock fragmentation is a critical operation that involves breaking rock masses or ores into smaller fragments through drilling and blasting, a process widely used in mining, civil, and tunnel engineering [1,2,3,4]. Research indicates that 70% of the explosive energy is not effectively utilized for fragmentation but is instead dispelled into the ground and air, leading to undesirable effects such as backbreak, airblast, flyrock, and ground vibration [5,6,7]. The fragmentation size has a significant impact on various aspects of mining and excavation operations, including ore extraction, productivity, downstream processes, and material handling efficiency [8,9,10,11]. As a result, to mitigate these challenges and achieve optimal fragments, it is essential to thoroughly understand the fragmentation process and predict fragmentation with high accuracy.

Predicting optimal fragmentation size presents challenges owing to the intricate nature of the blasting operations [12,13,14]. Consequently, numerous scholars have suggested diverse approaches aimed at parameter optimization and problem complexity reduction. For instance, Kuznetsov [15] developed a predictive model for the mean fragmentation size (MFS) that utilizes rock mass and explosive properties as the primary input factors. Cunningham [16,17] and Hekmat et al. [18] improved the Kuznetsov model and proposed the Kuz–Ram model, which linked the specific energy of the blasting mechanism to fragmentation size and incorporated rock mass properties. However, these empirical models were still inaccurate and had limited predictive capability, as they lacked consideration of other critical parameters, such as blast design. To address these limitations, empirical models that account for the distribution of blasted fragment sizes were developed. Examples include the Rosin–Rammler function [19], the Swebrec function [20], and the distribution-free function [21]. Other notable empirical models include the modified Kuz–Ram model [22] and the Bergmann, Riggle, and Wu (BRW) model [23], which was later modified by Holmberg and Larsson [24]. For ease of use, several researchers have developed simplified equations for the BRW model [25,26,27].

As aforementioned earlier, the empirical models often lack accuracy due to their heavy reliance on field blast experiments and the empirical relationship between rock properties and blasting outcomes. Consequently, attention has shifted towards artificial intelligence (AI)-based methods because of their remarkable achievements in the geotechnical field [28,29,30]. AI-based methods have demonstrated significant potential to improve the accuracy of rock fragmentation prediction by learning from data, identifying patterns, and managing complex interactions between blasting parameters and outcomes. For instance, support vector machines (SVMs) have been applied to predict mean particle size [31,32,33], while artificial neural networks (ANNs) have been among the most widely used AI-based techniques for predicting rock fragmentation size [11,34,35,36,37,38]. In addition, adaptive neural fuzzy inference systems (ANFISs) and fuzzy inference systems (FISs) have also been commonly utilized for rock fragmentation size prediction [14,39,40,41,42,43]. Despite the progress made by AI-based methods in enhancing the prediction accuracy of rock fragmentations, some limitations remain. For instance, ANNs perform well with large datasets but require extensive labeled data for training, while SVMs tend to show poor performance when dealing with large datasets.

Recently, hybrid machine learning (ML) techniques that combine traditional algorithms such as random forest and SVMs with advanced ensemble techniques have been applied to predict blasting outcomes [44,45]. Additionally, hybrid optimization algorithms have also gained the attention of scholars because of their better performance than traditional metaheuristic optimization algorithms [46,47,48].

Tree-based algorithms have gained popularity for predicting particle size distribution and MFS in rock fragmentation. For instance, Armaghani et al. [49] utilized a light gradient-boosted machine (LightGBM) algorithm optimized by the Jellyfish search optimizer (JSO) to predict blast-induced rock fragmentation. This work aimed to identify a model capable of managing the inherent noise present in dataset measurements and predictions. Consequently, this study prefers tree-based algorithms over ANNs and SVMs due to their superior generalization capabilities on noisy data and their adaptability to datasets of varied sizes [50].

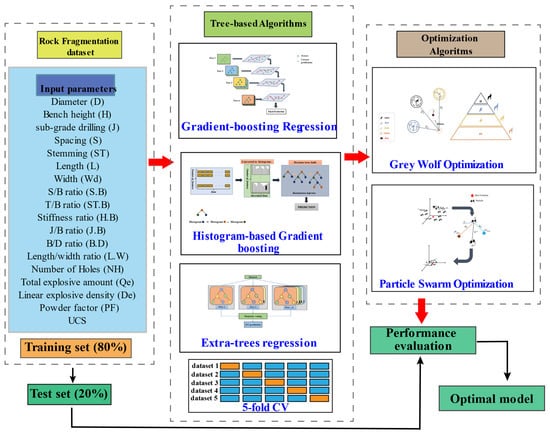

For the development of the predictive model, this study utilized a rock fragmentation dataset containing 76 blast records with 19 input features collected by Sharma and Rai [51]. This dataset offers an extensive range of features compared with other studies on similar topics, facilitating models in learning complex interactions and non-linear relationships of features. Three tree-based regression algorithms, i.e., histogram-based gradient boosting machine (HGB), gradient boosting regression tree (GBR), and extra-trees (ET) algorithms, were used as base predictors, in combination with two nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization techniques, particle swarm optimization (PSO) and grey wolf optimization (GWO), to optimize the hyperparameters because of their computational efficiency during training and optimization, which is one of the objectives of this study. The coefficient of determination (R2) was employed to evaluate the optimization process. Furthermore, K-fold cross-validation was employed to evaluate the generalization capabilities of various models. The models’ performance was measured using four statistical metrics: R2, root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). Finally, the Shapley additive explanation (SHAP), local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME), and neural network-based sensitivity analyses were applied and compared to evaluate and quantify the impact of input parameters on the model predictions.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Description

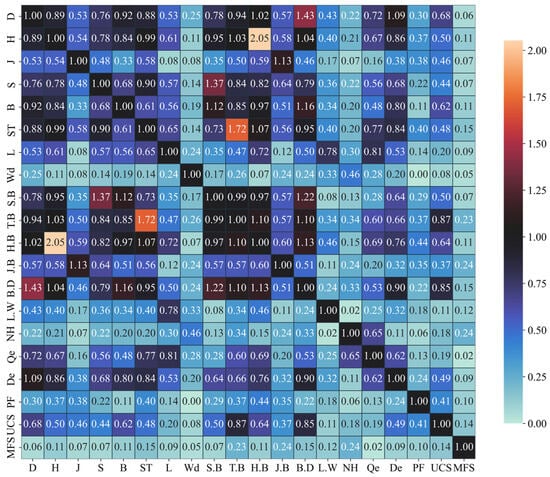

This study used 76 groups of datasets to develop a prediction model for estimating the blasting fragmentation size. The dataset contains 19 influencing parameters, categorized into blast design, explosive, and rock mass parameters. Figure 1 shows a mutual information regression (MI) heatmap illustrating the relationship between the influencing parameters and the target parameter (MFS, m). The bright and dark colors indicate that the input features share a lot of information with the target feature and are highly relevant, whereas the light colors indicate that they share little information and are of little relevance to the target feature. MI quantifies the amount of information shared between two variables, making it particularly suitable for non-linear relationships, as it does not assume a specific data distribution. Therefore, MI is a suitable technique for the used dataset, which is non-linear. Figure 1 reveals that the input features most strongly correlated with the target variable (MFS) include stemming–burden ratio (T.B), stemming (ST), sub-grade drilling–burden ratio (J.B), number of holes (NH), burden–blast hole diameter ratio (B.D), and uniaxial compressive strength (UCS, MPa). In addition to examining the correlation between parameters, the data distribution provides valuable insights. Figure 2 shows the general distribution of the data using boxplots. In these boxplots, the red line represents the median value, the green dotted line represents the mean value, the ‘light blue’ boxes indicate the range of data from lower to upper quartiles, and the tips of the whiskers represent the maximum and minimum values, respectively. The small brown boxes represent outliers. For instance, Figure 2 shows that ST, width (Wd), NH, total explosive amount (Qe, t), powder factor (PF, kg/m3), and UCS contain outliers. Table 1 summarizes the categories of the parameters and provides the summary statistics of the blast fragmentation data.

Figure 1.

Mutual information regression (MI) heatmap of rock fragmentation parameters.

Figure 2.

Rock fragmentation data distribution based on boxplots.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of rock fragmentation data.

2.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

2.2.1. Tree-Based Boosting Algorithms

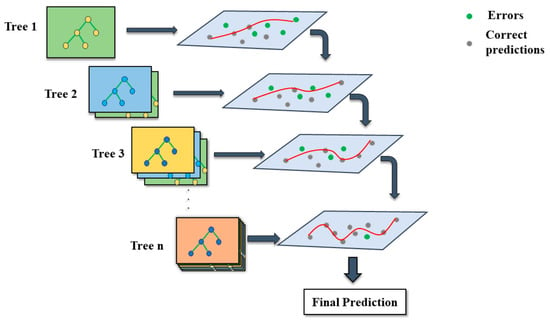

Tree-based boosting algorithms were proposed by Freund [52]. Therefore, boosting-based algorithms are an ensemble of machine learning algorithms that use decision trees as their base learners. They operate by iteratively combining weak learners to adjust their weights and correct their errors, ultimately resulting in a strong learner. Later, Friedman [53] introduced a gradient boosting algorithm by introducing gradient descent into the boosting algorithms, making it more practical and efficient. In this study, two boosting-based algorithms, GBR and HGB, are used to compare their performance in estimating the value of MFS. The schematic work of the GBR algorithm is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The GBR algorithm framework.

Gradient boosting regression tree (GBR): For a given training dataset , gradient boosting aims to find an approximation, , of the function . Gradient boosting is a weighted sum of the additive approximation of .

where is the weight of the function, . These are models of the decision trees.

First, the weak learner is initialized, and the approximation is built iteratively as follows:

where is the loss function.

The following weak learners with optimal negative gradient fitting are calculated as follows:

However, rather than solving the optimization problem directly, each is viewed as a greedy step in the gradient descent optimization for . For j samples in the training dataset, , where , the residual along the gradient direction is calculated as follows:

where n is the number of estimators.

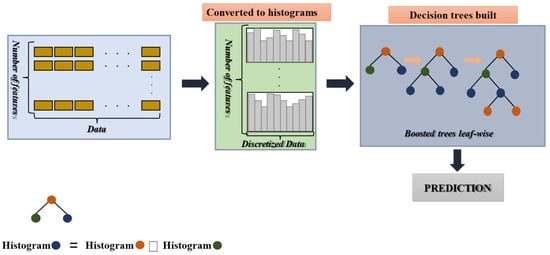

HGB: HGB is inspired by the light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), which is a GBDT algorithm that incorporates two innovative techniques: gradient-based one-sided sampling (GOSS) and exclusive feature bundling (EFB) [54]. In HGB, during tree fitting, the training samples are first discretized into integer-valued histograms. Instead of evaluating all possible splits for each feature in the training dataset, the histograms are used during the node-splitting process [55]. Figure 4 illustrates the framework of the HGB algorithm.

Figure 4.

The HGB algorithm framework.

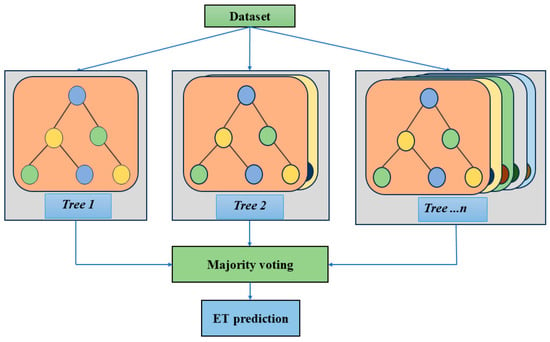

2.2.2. Extra Trees Algorithm

The ET algorithm, derived from the random forest (RF) algorithm, is an ensemble-based technique introduced by Geurts et al. [56]. The ET differs from RF in two primary ways: (1) the ET employs the whole training dataset to build each tree, thereby minimizing bias; (2) the ET randomizes the selection of cutting points and partitions the nodes by randomly choosing from these points [57]. The splitting process in the ET method is controlled by two parameters: K and nmin. K defines the number of nodes, with randomly chosen attributes at each node, while nmin denotes the minimum sample size required for the node partitioning. The two parameters enhance the model accuracy while mitigating overfitting in the ET algorithm [58,59].

Like the RF, the ET performs regression through bootstrapping and bagging. During the bootstrapping stage, a random sample of the training dataset is employed to construct the decision trees. In the bagging stage, the decision tree nodes are partitioned into random subsets of the training data. The final prediction is determined by randomly selecting a subset and its corresponding value. The framework of the ET algorithm is illustrated in Figure 5. Mathematically, the ET regression process is expressed by the equation proposed by Breiman [60]:

where is the nth predicting tree, and is a uniform, independently distributed vector.

Figure 5.

The framework of ET algorithm.

2.3. Optimization Algorithms

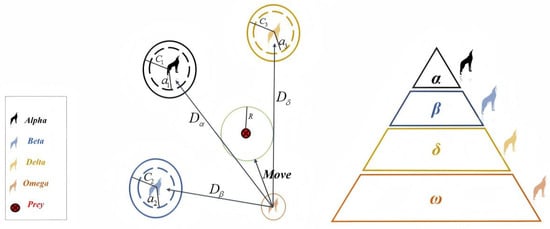

2.3.1. Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)

The GWO is a recent swarm-based algorithm suggested by Mirjalili et al. [61]. It is inspired by the social structure and hunting behavior of grey wolves [62]. The hierarchical structure of the pack typically consists of four distinct types of wolves, each fulfilling different roles, as illustrated in Figure 6. The alpha wolf (α) is the leader and decision-maker of the pack. It issues commands to the other wolves, who submit to its authority [63]. The beta wolves (β) rank second in the hierarchy. They assist the alpha in decision making, offer advice, enforce the alpha wolf’s orders to the lower-ranking wolves, and provide feedback. The delta wolves (δ) serve as the caretakers, hunters, elders, and scouts. This group includes wolves responsible for patrolling boundaries, alerting the pack to potential threats, and hunting for food. The omega wolves (ω) are the lowest-ranking wolves in the pack. While they may seem insignificant, their role is crucial in maintaining the social structure of the pack. As the scapegoats, they help prevent internal conflicts by absorbing aggression from higher-ranking wolves.

Figure 6.

An illustration of grey wolves’ social hierarchy and movement.

As mentioned above, pack hunting is one of the grey wolves’ social behaviors, and it is categorized into two main stages [64].

- Pursuing and encircling prey

Grey wolves pursue and encircle their prey during the hunt, and this can be mathematically expressed below:

where indicate the position vector of prey, grey wolf, and current iteration; and are the coefficient vectors; and is the distance between the grey wolf and its prey.

The and coefficient vectors are calculated as follows:

where are random vectors ranging from 0 to 1, and is a variable that linearly decreases from 2 to 0 as the iterations increase.

- 2.

- Hunting and attacking the prey

The hunt is occasionally led by the alpha wolf (representing the best candidate solution) with assistance from the beta and delta wolves. These three wolves update their position based on the location of the prey, while the remaining wolves (including the omega wolves) also update their positions according to the best hunters. This is mathematically expressed as follows:

The best position of the prey is calculated by estimating the position of alpha, beta, and delta wolves toward the prey as follows:

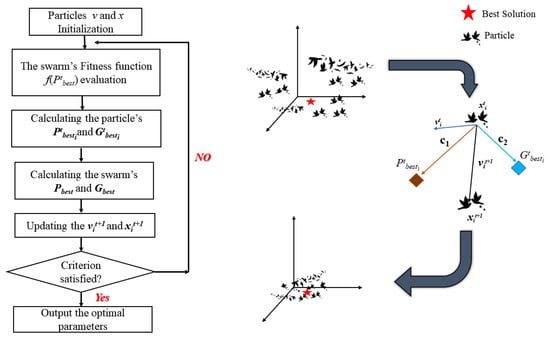

2.3.2. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

The PSO algorithm is inspired by a model called Bird-oid, proposed by Reynolds et al. [65], which simulates the behavior of birds. Similarly, the PSO algorithm solves optimization problems mimicking the behavior of fish schools and bird flocks searching for food [66]. In this process, each bird represents a particle in an N-dimensional search space. Information about the search, such as the food source, position, and distance between the flock of birds, is transmitted among the particles such that each particle knows its position, velocity, and that of the swarm. During the search process, each particle updates its position and global position in the swarm until it reaches its best position (Pbest) and global best position (Gbest) for an optimal solution [67]. Figure 7 illustrates the general steps of the search process of the PSO algorithm.

where , and

where denotes an index of particles, represents the current number of iterations, denotes an objective function, denotes the position of the particle, denotes all particles in the swarm, denotes the velocity vector of particles, denotes inertia weight balancing exploitation and exploration of local and global optimization, respectively, and are random vectors within the 0 to 1 range, and and are acceleration coefficients.

Figure 7.

A general demonstration of the PSO algorithm search process.

2.4. Shapley Additive Explanation

Although AI-based models show great promise and have become prominent in predictive tasks, they are often considered unreliable in many fields. This is primarily because they do not provide sufficient explanations or justifications for their predictions. Moreover, the internal workings of these models are difficult for human logic to interpret, which is why they are referred to as ‘black boxes’ [68]. To enhance transparency and elucidate the intricate relationships between input and output features, explainable AI (XAI) methodologies are utilized for model interpretation [69]. Among these XAI techniques are SHAP and local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME). This study compares SHAP and LIME for model interpretation. SHAP is a cumulative feature attribution algorithm that quantifies the contribution of individual input features. It emulates game theory to explain the results of machine learning models. The main concept is to assess each player’s contribution to the overall reward, taking into account all potential player combinations. The Shapley value for a specific player represents the average marginal contribution they provide over all conceivable coalitions of players. In machine learning, features are regarded as players, whereas the prediction function f(x) is the characteristic function. The objective is to elucidate the forecast f(x) for a certain instance x. For a certain instance x and a model f, the SHAP value for feature i is defined as Equation (18) [70].

where is the subset of features excluding i; is the value of the model prediction instance x with features in D set to their values in x and other features marginalized. denotes the marginal contribution of feature i to the prediction when added to the subset D. is computed by the expected value of the model’s output with respect to the missing features, employing Equation (19). Additionally, this study utilized TreeSHAP, which inherently computes exact conditional expectations because of its internal tree structure and was applied to interpret the model predictions. Therefore, only valid combinations of feature splits are utilized.

2.5. Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations

Local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) explore how data variations affect machine learning model predictions. LIME creates a new dataset with novel samples and black box model predictions. LIME then trains an interpretable model on this new dataset, weighted by sampled example proximity to the instance of interest. The trained model should precisely approximate the machine learning model’s local predictions, but not globally. This accuracy is called local fidelity. Local surrogate models subject to interpretability constraints can be mathematically formulated as follows:

where the explanation model for instance x is the model g that minimizes loss; L denotes loss, which measures how close the explanation is to the original model ; denotes model complexity; and is the proximity measure that defines the size of the neighborhood around the instance for explanation.

2.6. Neural Network Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis (SA) examines the impact of input features on the output of the model. It correlates inputs to outcomes using either data-driven or process-based mathematical models [71]. The SA helps with feature selection, stability assessment, and interpretability of the model [72]. This study examines three extensively utilized SA approaches in neural networks. Moreover, SA is utilized to verify and validate SHAP and LIME interpretations. The three approaches include perturbation-based, gradient-based, and variance-based SAs.

2.6.1. Perturbation-Based SA

Perturbation-based SA measures the output feature’s responsiveness to minor variations (perturbations) in its input parameters. In model f(x), the perturbation sensitivity is expressed using Equation (21):

where denotes perturbation sensitivity score; denotes one-hot vector for the i-th feature; and denotes the minor change. If the output varies significantly, the model exhibits great sensitivity to perturbations. However, if the output remains consistent, it is considered robust. As the becomes infinitesimal, the perturbation sensitivity approaches the gradient:

2.6.2. Gradient-Based SA

Gradient-based SA assesses the output’s response to small changes in each input feature by employing partial derivatives (gradients) as a sensitivity measure. The gradient represents the slope of the prediction surface with respect to each input feature. This approach explains the local behavior by characterizing the model’s performance around the input nominal point [73]. Consequently, the gradient magnitude signifies the local importance of each feature in relation to a particular input sample. However, it is sensitive to scaling features, zero gradient does not invariably indicate a lack of significance, and global ranking is required for highly nonlinear models [74]. For an input x, the sensitivity score for feature i is

where denotes the gradient-based sensitivity score. A large gradient indicates that a small change in feature results in a significant change in the prediction, whereas a small gradient suggests that the feature has minimal impact.

2.6.3. Variance-Based SA

Variance-based SA is a global approach that quantifies each input feature’s contribution to the variability of a model’s output, especially in complex nonlinear models [75]. Suppose the model is . Then, each input contributes a specific fraction to the total output variance [76]. The total output variance is the sum of three contributions: individual features, interactions between features, and higher-order interactions. The high-order interactions include the first-order Sobol index and the total-order Sobol index, which are key sensitivity indices [75]. The sensitivity indices are calculated using Monte Carlo sampling as per Equations (24) and (25). This approach offers the advantages of capturing effects across the entire input space, not just locally, and it also quantifies feature interactions explicitly.

where q and p are two random sample matrices with shape ; are hybrid matrices where all columns come from q, except column i, which comes from p.

3. Model Development

The accuracy of machine learning algorithms depends on the combination and interaction of their internal hyperparameters. However, determining the optimal set of hyperparameters for a given problem can be challenging. To address this, GWO and PSO optimization algorithms were used to identify the optimal hyperparameters for GBR, HGB, and ET models, resulting in more accurate prediction models for determining the MFS after blasting. As a result, six predictive models, namely, GWO-HGB, GWO-GBR, GWO-ET, PSO-HGB, PSO-GBR, and PSO-ET, were trained on the dataset and compared to identify the best model for predicting MFS.

Firstly, the data were randomly divided into training and test sets. The training set comprised 80% (60 data samples), while the test set accounted for 20% (16 data samples). The 80/20 ratio works better on a small-scale dataset since it provides sufficient training data for the model’s generalization capabilities, hence mitigating the likelihood of overfitting. Secondly, five-fold cross-validation was employed, given the dataset size, to enhance the generalization and robustness. Finally, the proposed optimization algorithms fine-tuned the models’ hyperparameters until the best fitness value was achieved. Each model was optimized three times with different swarm sizes for comparison. The framework of the developed model is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The proposed predictive models’ framework.

This study used four evaluation metrics to assess the performance of the proposed models on test data, including , RMSE, MAE, and MAPE. These evaluation metrics are computed using the following equations:

where denotes the actual MFS values; denotes the predicted MFS values; denotes the mean value of MFS; and denotes the total number of MFS training samples. R2 squared measures the variance in the predicted variable, where its values range from 0 to 1, and close to 1 means the model performed great, while close to 0 means it performed poorly. RMSE measures how far the predicted values are from the actual values; lower RMSE values mean better performance. MAE shows the mean absolute difference between the predicted and the actual values; lower MAE values mean better performance. MAPE measures the accuracy of the model as a percentage; a lower MAPE value indicates better accuracy of the model.

4. Results and Discussion

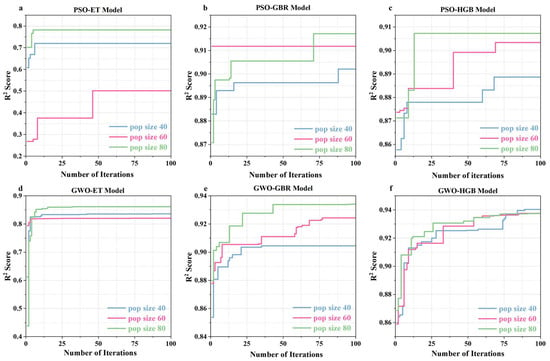

4.1. Optimization Process

As mentioned in Section 3, two optimization algorithms (PSO and GWO) were employed to enhance the performance of the models. The two meta-heuristic optimization algorithms are influenced by several parameters, including the number of iterations and swarm sizes. Larger swarm sizes result in slower convergence but generally yield better optimization fitness, while smaller swarm sizes lead to faster convergence. A higher number of iterations increases computation, prolonging convergence, while a small number of iterations may lead to underfitting and prevent proper convergence. Therefore, this study compares swarm sizes of 40, 60, and 80 to identify the best swarm size. To balance performance and computational cost, the number of iterations is set to 100 for all models. The average computational time for training each algorithm was under 5 min; however, the optimization time varied significantly. GWO-optimized algorithms required 30 min to achieve optimal fitness, while PSO-optimized algorithms took 45 and 60 min to attain the same aim. However, this extended duration was attributable to insufficient computational resources, specifically a graphical processing unit (GPU), which may potentially halve the time required or lower it even more. Table 2 lists the hyperparameters, search spaces, and regression algorithms optimized to obtain the best fitness value for the models.

Table 2.

Optimized hyperparameters with their search spaces.

Figure 9 depicts the best fitness values of the different swarm sizes and their predictive models after optimization. The y-axis represents the best fitness values, while the x-axis represents the number of iterations. The best fitness value was evaluated using the R2. When comparing the results, it is observed that the swarm size of 80 produces the best fitness value for the other models, except for the GWO-HGB model. Additionally, GWO-optimized models obtained the best fitness value in comparison with the PSO-optimized models, with the GWO-HGB model demonstrating the best performance. As a result, the optimal hyperparameters for each model are listed in Table 3.

Figure 9.

Optimization process of the predictive models: (a) PSO-ET model, (b) PSO-GBR model, (c) PSO-HGB Model, (d) GWO-ET Model, (e) GWO-GBR Model, and (f) GWO-HGB Model.

Table 3.

The optimal hyperparameters for each prediction model.

4.2. Comparison of the Model Performance

Although GWO-optimized models produced the best fitness values compared with PSO-optimized models, it is not conclusive that GWO-optimized models will yield the best prediction overall results. Therefore, the six models were used to predict the MFS on both training and test sets after optimizing hyperparameters. Table 4 and Table 5 present the evaluation metrics and rank scores used to compare the prediction results of the different models on the training and test sets, respectively. According to Table 4, PSO-GBR achieves the highest rank score on the training set, making it the best-performing model with R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE values of 0.9999, 0.0003, 0.0001, and 0.0003, respectively. Meanwhile, in Table 5, on the test set, GWO-HGB attains the highest rank score of 19 and best prediction performance with R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE values of 0.9403, 0.0251, 0.0185, and 0.0560, respectively. However, a significant decline in performance on the test set for GWO-ET, PSO-ET, and PSO-GBR models is observed, which indicates potential overfitting. This results from the complexity of the models and insufficient training data.

Table 4.

Models’ performance on the training set.

Table 5.

Models’ performance on the test set.

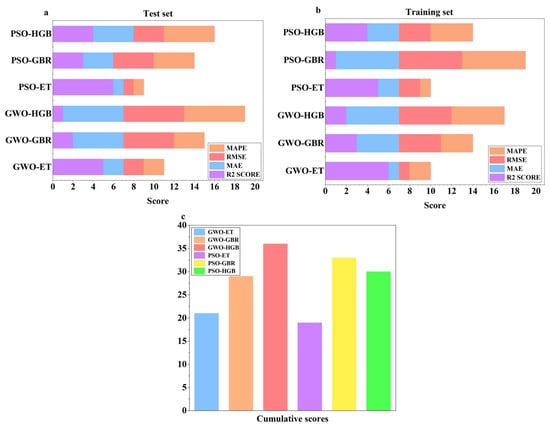

For an intuitive comparison, the ranking scores of the evaluation metrics of the models are displayed using bar charts in Figure 10. As shown in Figure 10a, on the test set, PSO-HGB, GWO-HGB, and GWO-GBR all rank above 15, and GWO-HGB achieves the highest rank score of 19. Meanwhile, as shown in Figure 10b on the training set, PSO-GBR and GWO-HGB had ranking scores above 15, and PSO-HGB reached the highest score of 19. Overall, GWO-HGB outperformed all other models with a total score of 36, as shown in Figure 10c. Interestingly, the HGB regression algorithm performed excellently in both phases, regardless of the optimization algorithm used. This demonstrates the robustness of the HGB algorithm in predicting the rock fragmentation size.

Figure 10.

Rank scores of valuation metrics: (a) test set; (b) training set; and (c) cumulative scores.

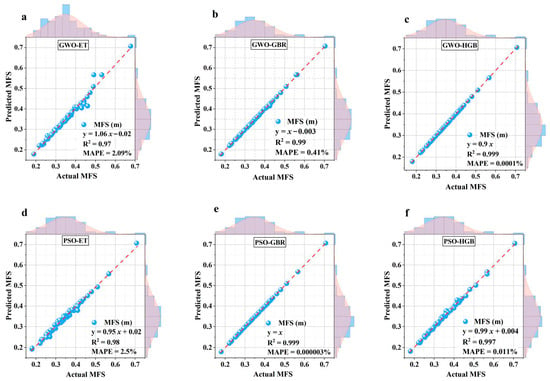

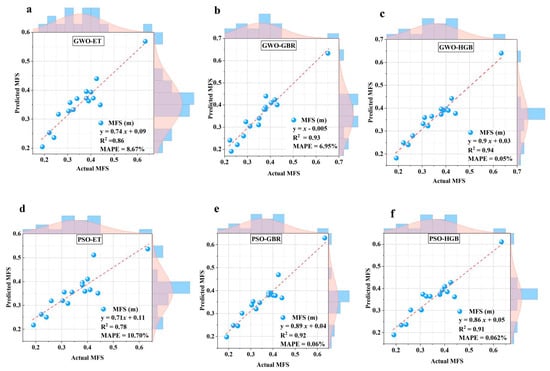

Figure 11 and Figure 12 are scatter plots illustrating the relationship between the actual and predicted MFS using regression diagrams for both the training and test sets, offering a detailed analysis of the prediction outcomes. The vertical represents the predicted values, while the horizontal axis represents actual MFS values. The diagonal red dotted line indicates the line of best fit, where the relationship between the actual and predicted variables (y = x) is ideal. Therefore, data points along this line indicate a strong correlation between the actual and predicted MFS, while points deviating from the line highlight prediction errors. As observed in Figure 11b,c,e, the GWO-GBR, GWO-HGB, and PSO-GBR models exhibit a nearly perfect correlation between the actual and the predicted MFS values, with no prediction errors in the training set. However, in the test set, some prediction errors are present. Among the six models, the GWO-HGB model demonstrates the smallest prediction errors, achieving an MAPE of 0.05% as illustrated in Figure 12c. While PSO-GBR performs slightly better than GWO-HGB on the training set, GWO-HGB outperforms PSO-GBR in terms of generalization on the test set, exhibiting superior performance compared with the other models. Although PSO-ET performs well on the training set, it shows poor generalization on the test set, indicating overfitting of the model. In general, HGB-based models outperform GBR-based and ET-based models.

Figure 11.

Scatter plots showing the relationship between predicted and actual MFS on training set: (a) GWO—ET, (b) GWO-GBR, (c) GWO—HGB, (d) PSO—ET, (e) PSO—GBR, (f) PSO—HGB.

Figure 12.

Scatter plots showing the relationship between predicted and actual MFS on test set: (a) GWO—ET, (b) GWO-GBR, (c) GWO—HGB, (d) PSO—ET, (e) PSO—GBR, (f) PSO—HGB.

As shown in Figure 13, the Taylor diagram provides further insight into the performance of the proposed models. Typically, a Taylor diagram includes three statistical metrics: the standard deviation, correlation coefficient, and RMSE. The figure has a black arc indicating correlation coefficient values, with both the x- and y-axes displaying standard deviation values, while the different colored concentric arcs signify the RMSE. The red curved line marking a reference point (red square) on the x-axis represents the actual MFS. The model’s proximity to the reference point indicates superior predictive performance. As shown in Figure 13a, the GWO-HGB, PSO-HGB, and PSO-GBR models outperform the other models on the training set, achieving a correlation coefficient of 0.99, closely aligning with the actual MFS and exhibiting an RMSE value of less than 0.02. In Figure 13b, the GWO-HGB model is distinguished as the best-performing model on the test set, with a correlation coefficient of 0.97 and an RMSE value below 0.04, thereby exceeding the other models in predictive accuracy.

Figure 13.

Comparison of model performance using Taylor diagram: (a) training set; (b) test set.

Table 6 compares the AI models in this study with other AI models developed in other studies on the same dataset. It can be observed in the table that the model in this study performs much better compared with the models in different studies.

Table 6.

Comparison of other models with the models in this study.

4.3. Model Interpretation

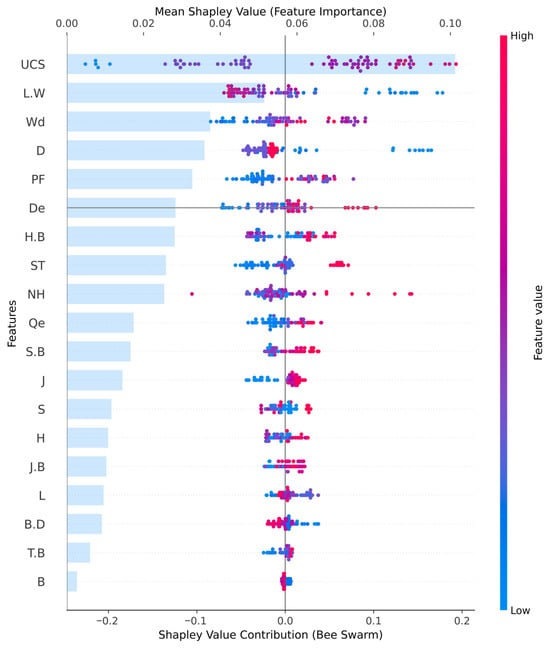

4.3.1. SHAP

To enhance model transparency and clarify its decision-making processes, the SHAP methodology was employed. In this study, the GWO-HGB model was selected for interpretive analysis due to its superior performance compared with the other evaluated models. Figure 14 depicts a composite visualization integrating a local bar plot and a bee swarm plot to illustrate the contributions of each feature to the model’s predictions. The bars in the local bar plot represent the SHAP values for each feature, providing insight into their contributions and distributions. The upper x-axis displays the mean SHAP values derived from the local bar plot, whereas the lower x-axis corresponds to the SHAP value contributions shown in the bee swarm plot. A color gradient in the bee swarm plot signifies the spectrum of feature values, with blue denoting lower values and red indicating higher values. From Figure 14, it is evident that UCS has a significant impact on the model’s predictions, with higher UCS values contributing positively and lower values contributing negatively. In contrast, B shows a relatively lower impact on the model’s prediction among all parameters, with higher B values indicating a positive contribution.

Figure 14.

A bar plot and a bee swarm plot display the contribution of features.

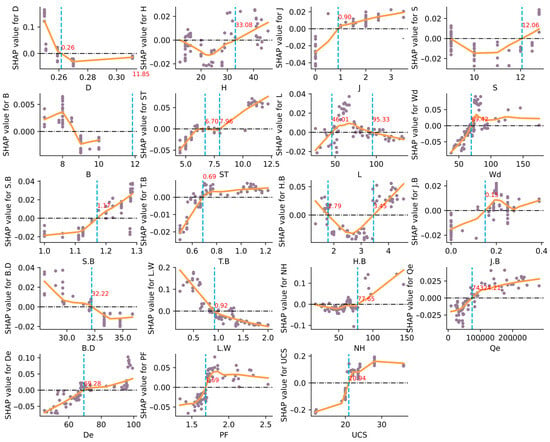

Figure 15 shows scatter plots with a LOWESS fit curve to elucidate the local influence of each attribute on the model’s predictions. The orange LOWESS curve denotes a locally weighted regression line that smooths out non-linear patterns in the data. The figure displays the fitted curves for all features in the dataset. Focusing on the features closely related to the MFS, as mentioned in Section 2.1, it can be observed from Figure 15 that T.B values below 0.69 negatively impact the model’s predictive output, while values above 0.69 have a positive influence. This indicates that higher T.B values should be prioritized when blasting rocks to achieve an optimal MFS. According to Figure 15, an optimal MFS can be achieved when T.B values are between 0.7–0.8 and 1.0–1.2. ST shows two significant points with no effect on the model, at values of 6.70 and 7.96. Values between 6.70 and 7.96 exert a negative effect on the prediction. While values above 7.96 impact the prediction positively. J.B values lower than 0.15 negatively influence the prediction, while values above 0.69 have a good effect on the prediction. NH positively influences the model’s prediction when its value exceeds 77; otherwise, it has a minor impact on the prediction. BD exhibits an inverse relationship with the Shapley values. Lower values have a more positive influence, while higher BD values lead to a more negative impact on the prediction, with a significant change occurring at 32.22. UCS is the most impactful feature in the model’s prediction. For UCS values above 20.94, the model’s prediction is positively influenced, while values below 20.94 have a negative impact. However, this does not mean that very high UCS values will produce better blasting results. As observed, UCS values close to 30 have a better impact than UCS values greater than 30 on the model prediction. Figure 16 illustrates the less impactful B, with an intersection line at 11.85, which exceeds the maximum value of B in this study. As a result, B has a negligible effect on the model’s prediction.

Figure 15.

LOWESS fit curve with SHAP scatter plot of each feature.

Figure 16.

LOWESS fit curve with SHAP scatter plot of B feature.

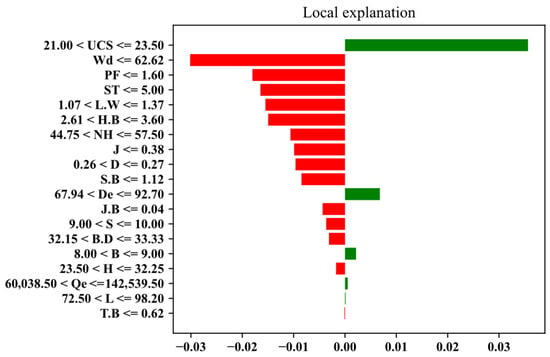

4.3.2. LIME

Figure 17 shows a bar plot with horizontal bars in red and green colors. The red color indicates features with negative weights that decrease the probability of the predicted value, whereas the green color indicates positive weights that increase it. It can be observed that UCS has the highest positive weight of over 0.03, which is pushing toward the prediction of the MFS value. The highest positive weight is observed when the feature values are between 21 and 23.50. Additionally, it can be observed that De, B, Qe, and L features have positive weights toward the model prediction at the local level.

Figure 17.

LIME bar plot showing local interpretations.

Similar to SHAP interpretations of outcomes, the LIME local interpretations also show that UCS is the most influential feature for the model prediction. SHAP indicated that UCS values greater than 20 have a positive influence on the model, while LIME showed that UCS values between 21 and 23.50 positively influence the model prediction. Therefore, the LIME interpretation results verify the SHAP results of UCS being the most significant feature. The UCS exerts the most significant influence on the model’s predictions, since it determines the design pattern, the required explosive energy, and the resultant fragmentation size.

4.3.3. Neural Network-Based Sensitivity Analysis

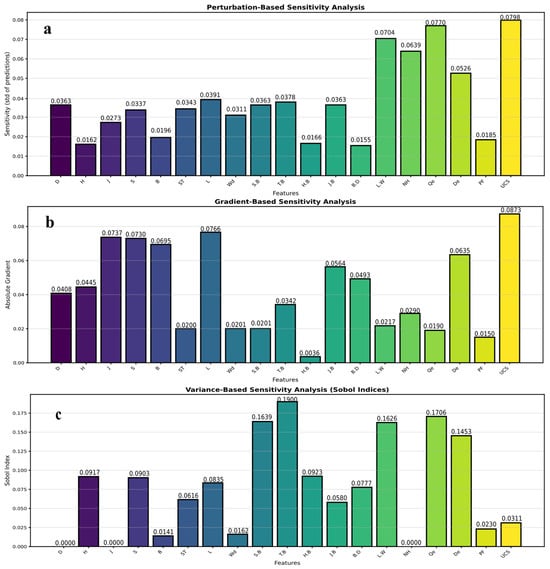

Neural network-based sensitivity analyses were utilized to further examine and validate the results from SHAP and LIME. Three methodologies, specifically perturbation-based, gradient-based, and variance-based SAs, were utilized to examine the sensitivity of predictions to alterations in input features.

Table 7 summarizes the sensitivity analysis results by illustrating the performance of each input feature across the three methodologies. Table 7 indicates that perturbation and gradient methods reveal UCS as the most significant feature in predicting MFS, with weights of 0.079843 and 0.087349, respectively, whereas the variance decomposition method indicates that T.B is the most influential feature. R2 identifies the most significant features as UCS, De, Qe, L.W, and T.B with respective scores of 0.7213, 0.7168, 0.6935, 0.6623, and 0.6217.

Table 7.

Neural network-based sensitivity analysis results.

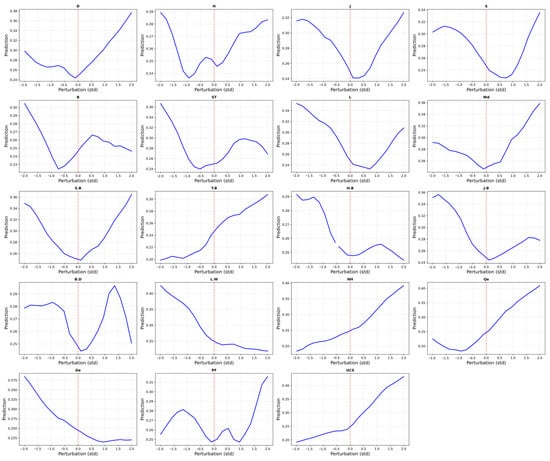

Figure 18 illustrates the distinct response curves of feature perturbations and their impact on the predictions, facilitating a deeper comprehension of the sensitivity study results. The y-axis indicates the predicted values, the x-axis illustrates the feature perturbations, and the dotted vertical red line signifies the point at which the feature remains constant. Given that UCS is the most influential characteristic, it will be the sole feature discussed. The response curve indicates that the UCS curve exhibits a steady rising trajectory with an almost uniform slope, signifying a sustained linear positive correlation. This indicates that during the occurrence of a severe blasting shock wave, the dynamic stress on the rock significantly escalates, yet the rock’s strength mitigates this impact. Consequently, UCS positively influences fragment size.

Figure 18.

Individual response curves of perturbation sensitivity analysis.

Figure 19 illustrates bar charts representing the three sensitivity analysis methodologies, comparing the overall weight of influence for all attributes. Figure 19a indicates that UCS (0.0798) and Qe (0.0770) are the predominant characteristics, but H.B (0.0166) and B.D (0.0155) exert little influence. Figure 19b indicates that UCS (0.0873) is the most significant feature, whereas H.B (0.0036) is the least significant feature in relation to MFS predictions. Figure 19c indicates that UCS (0.0311) is among the least influential features, whereas T.B (0.1900) is the most influential, suggesting that UCS may hold significance only in specific regions. This research indicates that UCS exerts a significant influence, and its interaction with MFS is robust and direct, both locally and globally, as evidenced by LIME and SHAP.

Figure 19.

Sensitivity analysis bar charts: (a) perturbation-based, (b) gradient-based, and (c) variance-based SAs.

4.4. Limitations

The models used in this study achieved satisfying predictions of MFS. However, there are still some limitations and downsides that need to be addressed in future research, including the following:

- The number of data samples used was small, making it challenging to obtain useful insights.

- Owing to the small dataset that the model was trained on, there is a potential risk of the model overfitting the data, as the model fails to learn all the patterns; instead, it memorizes the data. Particularly, this was observed with the PSO-GBR model.

- The comparison of additional swarm sizes and iterations was hindered due to insufficient computational resources.

- The models were solely evaluated on static data, not on time-dependent data; hence, an additional study is required to ascertain their performance with real-time data.

- The feasibility of these models to manage unfiltered and noisy dynamic large-scale data in real-time was not tested.

- Other powerful tree-based regression tools, such as random forest, Catboost, and LightGBM, were not explored and compared in this study.

5. Conclusions

Rock fragmentation size is a critical criterion for assessing the effectiveness of blasting operations. Therefore, predicting the optimum fragmentation size is crucial in mining, civil, and tunnel engineering. Due to the inherent complexity of the blasting operations and the intricate interactions among various influencing parameters, it is challenging to predict the MFS. Traditional empirical methods have limitations, while AI-based techniques have demonstrated their ability to capture complex interactions and accurately predict rock fragmentation sizes. The conclusions drawn from this study are as follows:

- According to the MI regression technique, the stemming–burden ratio, stemming, sub-grade drilling–burden ratio, number of holes, burden–blast hole diameter ratio, and unconfined compressive strength are the most closely related parameters to the mean fragmentation size.

- The GWO-HGB model obtained the best performance among all models, achieving R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE values of 0.9403, 0.0251, 0.0185, and 0.0561, respectively, on the test set. This demonstrates its dependability for blasting applications due to its high precision, capacity to manage noisy data, and minimal risk of overfitting. This paper presents a unique hybrid intelligent framework that combines tree-based regression models with metaheuristic optimizers (GWO and PSO) to improve the prediction of mean fragmentation size in blasting operations. The integration of SHAP, LIME, and neural network-based sensitivity analysis enhances model interpretability, providing both enhanced predictability and a more profound comprehension of the essential factors affecting fragmentation behavior. In comparison with other AI models created in different research utilizing the same dataset, the models in this study exhibited superior performance.

- The unconfined compressive strength was the most critical feature, whereas bench height was determined to be the least significant for predicting mean fragmentation size. SHAP, LIME, and neural network-based sensitivity analysis indicate that elevated unconfined compressive strength values enhance the model’s predictions more than lower values. Nonetheless, elevated unconfined compressive strength values may not necessarily yield superior blasting outcomes, as such rocks absorb a smaller proportion of the blast’s total energy and transmit a greater amount as ground vibrations, posing an environmental risk. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis utilizing neural networks indicated that the significance of unconfined compressive strength may be region-specific. These predictive outcomes offer significant assistance for complex blasting designs.

Author Contributions

M.M.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, software, investigation, and writing—original draft. S.H.: writing—original draft and review, methodology, validation, and software. C.L.: formal analysis, visualization, software, and writing—review and editing. X.Z.: investigation, validation, and writing—review and editing. J.Z.: conceptualization, investigation, validation, writing—review and editing, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the State Key Laboratory of Precision Blasting and Hubei Key Laboratory of Blasting Engineering, Jianghan University (no. PBSKL2023A12) and the National Major Science and Technology Project of China (no. 2025ZD1010703).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors confirm that this work complies with the ethical standards required by journals, and all necessary ethical approvals and informed consent have been obtained.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are openly available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2016.10.047.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cheng, R.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, W.; Hao, H. Effects of Axial Air Deck on Blast-Induced Ground Vibration. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 1037–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Lu, W.; Yan, P.; Chen, M.; Gao, Q.; Yang, Z. A new horizontal rock dam foundation blasting technique with a shock-reflection device arranged at the bottom of vertical borehole. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Chen, W.; Hao, H.; Li, J. Dynamic response of road tunnel subjected to internal Boiling liquid expansion vapour explosion (BLEVE). Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 123, 104363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, C.; Khandelwal, M.; Tao, M.; Li, C. Novel approach to evaluate rock mass fragmentation in block caving using unascertained measurement model and information entropy with flexible credible identification criterion. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 3789–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Osanloo, M.; Rashidinejad, F.; Aghajani Bazzazi, A.; Taji, M. Multiple regression, ANN and ANFIS models for prediction of backbreak in the open pit blasting. Eng. Comput. 2014, 30, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Choi, Y.; Bui, X.-N.; Nguyen-Thoi, T. Predicting blast-induced ground vibration in open-pit mines using vibration sensors and support vector regression-based optimization algorithms. Sensors 2019, 20, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Nguyen, H.; Bui, X.-N.; Tran, Q.-H.; Moayedi, H. A Novel Artificial Intelligence Approach to Predict Blast-Induced Ground Vibration in Open-Pit Mines Based on the Firefly Algorithm and Artificial Neural Network. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehu, S.A.; Yusuf, K.O.; Hashim, M.H.M. Comparative study of WipFrag image analysis and Kuz-Ram empirical model in granite aggregate quarry and their application for blast fragmentation rating. Geomech. Geoengin. 2022, 17, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopialipoor, M.; Ghaleini, E.N.; Haghighi, M.; Kanagarajan, S.; Maarefvand, P.; Mohamad, E.T. Overbreak prediction and optimization in tunnel using neural network and bee colony techniques. Eng. Comput. 2019, 35, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaghani, D.J.; Hajihassani, M.; Mohamad, E.T.; Marto, A.; Noorani, S.A. Blasting-induced flyrock and ground vibration prediction through an expert artificial neural network based on particle swarm optimization. Arab. J. Geosci. 2014, 7, 5383–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, E.; Monjezi, M.; Khalesi, M.R.; Armaghani, D.J. Prediction and optimization of back-break and rock fragmentation using an artificial neural network and a bee colony algorithm. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2016, 75, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Yang, F.; Ren, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Khandelwal, M. Prediction of blasting mean fragment size using support vector regression combined with five optimization algorithms. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 1380–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, A.K.; Vajre, R.; Sangode, A.; Chandar, K.R. Application of artificial intelligence in predicting rock fragmentation: A review. In Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Mining and Geotechnical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, S.F.F.; Ebtehaj, I.; Hasanipanah, M.; Bonakdari, H.; Amnieh, H.B. Proposing a novel hybrid intelligent model for the simulation of particle size distribution resulting from blasting. Eng. Comput. 2019, 35, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, V. The mean diameter of the fragments formed by blasting rock. Sov. Min. Sci. 1973, 9, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C. The Kuz-Ram model for prediction of fragmentation from blasting. In First International Symposium on Rock Fragmentation by Blasting; Holmberg, R., Rustan, A., Eds.; Luleå University of Technology: Lulea, Sweden, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, C. The Kuz-Ram fragmentation model–20 years on. In Brighton Conference Proceedings; European Federation of Explosives Engineer: Brighton, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hekmat, A.; Munoz, S.; Gomez, R. Prediction of Rock Fragmentation Based on a Modified Kuz-Ram Model; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchterlony, F.; Sanchidrián, J.A. A review of the development of better prediction equations for blast fragmentation. Rock Dyn. Appl. 2018, 3, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchterlony, F. The Swebrec© function: Linking fragmentation by blasting and crushing. Min. Technol. 2005, 114, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchidrián, J.A.; Ouchterlony, F. A distribution-free description of fragmentation by blasting based on dimensional analysis. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2017, 50, 781–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibie, S.; Aghababaei, H.; Hoseinie, S.; Pourrahimian, Y. Modified Kuz—Ram fragmentation model and its use at the Sungun Copper Mine. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2009, 46, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, O.R.; Riggle, J.W.; Wu, F.C. Model rock blasting—Effect of explosives properties and other variables on blasting results. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1973, 10, 585–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, B. Report on blasting of high and low benches–fragmentation from production blasts. In Proceedings of Discussion Meeting BK74; Swedish Rock Construction Committee: Stockholm, Sweden, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dotto, M.S.; Pourrahimian, Y. The Influence of Explosive and Rock Mass Properties on Blast Damage in a Single-Hole Blasting. Mining 2024, 4, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aler, J.; Du Mouza, J. Predicting blast fragmentation efficiency using discriminant analysis. In Measurement of Blast Fragmentation; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchterlony, F. Influence of Blasting on the Size Distribution and Properties of Muckpile Fagments: A State-of-the-Art Review; Swedish Rock Blasting Research Centre, Swebrec at LTU: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, V.; Biswas, R.; Samui, P.; Kaloop, M.R.; Alzara, M.; Yosri, A.M. Hybrid ELM and MARS-based prediction model for bearing capacity of shallow foundation. Processes 2022, 10, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Samui, P.; Rai, B. Determination of compressive strength using relevance vector machine and emotional neural network. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 20, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaghani, D.J.; Koopialipoor, M.; Marto, A.; Yagiz, S. Application of several optimization techniques for estimating TBM advance rate in granitic rocks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 11, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-z.; Zhou, J.; Wu, B.-b.; Huang, D.; Wei, W. Support vector machines approach to mean particle size of rock fragmentation due to bench blasting prediction. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Salimi, A.; Drebenstedt, C.; Abbaszadeh, M.; Aghajani Bazzazi, A. Application of PCA, SVR, and ANFIS for modeling of rock fragmentation. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 6881–6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Karbasi, M.; Hasanipanah, M.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J. Developing GPR model for forecasting the rock fragmentation in surface mines. Eng. Comput. 2018, 34, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitraki, L.; Christaras, B.; Marinos, V.; Vlahavas, I.; Arampelos, N. Predicting the average size of blasted rocks in aggregate quarries using artificial neural networks. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 2717–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjezi, M.; Mohamadi, H.A.; Barati, B.; Khandelwal, M. Application of soft computing in predicting rock fragmentation to reduce environmental blasting side effects. Arab. J. Geosci. 2014, 7, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, P.F.; Monjezi, M.; Hamidi, J.K.; Armaghani, D.J. Optimization of flyrock and rock fragmentation in the Tajareh limestone mine using metaheuristics method of firefly algorithm. Eng. Comput. 2018, 34, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Monjezi, M.; Goshtasbi, K.; Ghazvinian, A. Prediction of rock fragmentation due to blasting using artificial neural network. Eng. Comput. 2011, 27, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murlidhar, B.R.; Armaghani, D.J.; Mohamad, E.T.; Changthan, S. Rock fragmentation prediction through a new hybrid model based on imperial competitive algorithm and neural network. Smart Constr. Res. 2018, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanipanah, M.; Amnieh, H.B.; Arab, H.; Zamzam, M.S. Feasibility of PSO–ANFIS model to estimate rock fragmentation produced by mine blasting. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 30, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjezi, M.; Rezaei, M.; Yazdian Varjani, A. Prediction of rock fragmentation due to blasting in Gol-E-Gohar iron mine using fuzzy logic. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2009, 46, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, C.; Arslan, C.A.; Hasanipanah, M.; Bakhshandeh Amnieh, H. Performance evaluation of hybrid FFA-ANFIS and GA-ANFIS models to predict particle size distribution of a muck-pile after blasting. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, A.; Monjezi, M.; Talebi, N.; Khandelwal, M. A comparative study on the application of various artificial neural networks to simultaneous prediction of rock fragmentation and backbreak. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2013, 5, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulatilake, P.H.S.W.; Qiong, W.; Hudaverdi, T.; Kuzu, C. Mean particle size prediction in rock blast fragmentation using neural networks. Eng. Geol. 2010, 114, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shylaja, G.; Prashanth, R. A systematic survey of hybrid ML techniques for predicting peak particle velocity (PPV) in open-cast mine blasting operations. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh Shahri, A.; Pashamohammadi, F.; Asheghi, R.; Abbaszadeh Shahri, H. Automated intelligent hybrid computing schemes to predict blasting induced ground vibration. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 3335–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirfallah Lialestani, S.P.; Parcerisa, D.; Himi, M.; Abbaszadeh Shahri, A. A novel modified bat algorithm to improve the spatial geothermal mapping using discrete geodata in Catalonia-Spain. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 4415–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh Shahri, A.; Khorsand Zak, M.; Abbaszadeh Shahri, H. A modified firefly algorithm applying on multi-objective radial-based function for blasting. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 2455–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraninezhad, R.; Asheghi, R.; Ahmadi, H. A new enhanced grey wolf optimizer to improve geospatially subsurface analyses. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, M.; He, B.; Armaghani, D.J.; Abbasi, P.; Mohamad, E.T. A novel ensemble machine learning model to predict mine blasting–induced rock fragmentation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Shen, W. A Review of Ensemble Learning Algorithms Used in Remote Sensing Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Rai, P. Establishment of blasting design parameters influencing mean fragment size using state-of-art statistical tools and techniques. Measurement 2017, 96, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Advances in neural information processing systems. Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Al Adwan, J.; Alzubi, Y.; Alkhdour, A.; Alqawasmeh, H. Predicting compressive strength of concrete using histogram-based gradient boosting approach for rapid design of mixtures. Civ. Eng. Infrastruct. J. 2023, 56, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mame, M.; Qiu, Y.; Huang, S.; Du, K.; Zhou, J. Mean Block Size Prediction in Rock Blast Fragmentation Using TPE-Tree-Based Model Approach with SHapley Additive exPlanations. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, P.; Ernst, D.; Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 2006, 63, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwani, M.; Begum, M.Y. Computational intelligence modeling of hyoscine drug solubility and solvent density in supercritical processing: Gradient boosting, extra trees, and random forest models. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastelini, S.M.; Nakano, F.K.; Vens, C.; Carvalho, A.C.P. Online Extra Trees Regressor. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 6755–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mame, M.; Huang, S.; Li, C.; Zhou, J. Application of Extra-Trees Regression and Tree-Structured Parzen Estimators Optimization Algorithm to Predict Blast-Induced Mean Fragmentation Size in Open-Pit Mines. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; As’arry, A.; Hassan, M.K.; Hairuddin, A.A.; Mohamad, H. Review of the grey wolf optimization algorithm: Variants and applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 2713–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mech, L.D. Alpha status, dominance, and division of labor in wolf packs. Can. J. Zool. 1999, 77, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, C.; Escobedo, R.; Spector, L.; Coppinger, R.P. Wolf-pack (Canis lupus) hunting strategies emerge from simple rules in computational simulations. Behav. Process. 2011, 88, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, C.W. Flocks, herds and schools: A distributed behavioral model. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Anaheim, CA, USA, 27–31 July 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gad, A.G. Particle swarm optimization algorithm and its applications: A systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 2531–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tan, D.; Liu, L. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: An overview. Soft Comput. 2018, 22, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, I.; Meddage, D.; Rathnayake, U. A novel approach to explain the black-box nature of machine learning in compressive strength predictions of concrete using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cho, S.; Vasarhelyi, M. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in auditing. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2022, 46, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.; Jakeman, A.; Saltelli, A.; Prieur, C.; Iooss, B.; Borgonovo, E.; Plischke, E.; Lo Piano, S.; Iwanaga, T.; Becker, W.; et al. The Future of Sensitivity Analysis: An essential discipline for systems modeling and policy support. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 137, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, A.; Lambert-Lacroix, S.; Poggi, J.-M. Random forests for global sensitivity analysis: A selective review. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 206, 107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiang, P.; Hu, C.; Yan, T. Comparison of local and global sensitivity analysis methods and application to thermal hydraulic phenomena. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2023, 158, 104612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghnegahdar, A.; Razavi, S. Insights into sensitivity analysis of Earth and environmental systems models: On the impact of parameter perturbation scale. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 95, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouhri, W.; Homri, L.; Dantan, J.-Y. Handling the impact of feature uncertainties on SVM: A robust approach based on Sobol sensitivity analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 189, 115691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Huang, D.; Chen, Z. An improved sobol sensitivity analysis method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2747, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.