Abstract

Real-time estimation of vehicle sideslip angle is essential for both safety and performance applications. This study presents a temperature-adaptive Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) that estimates the sideslip angle of a racing vehicle by integrating dynamic and kinematic information. A temperature-dependent Pacejka tire model, derived directly from track tests, is embedded in a 3-degree-of-freedom dual-track vehicle model and used within the EKF to compensate for temperature-induced variations in tire behavior. The adaptive model parameters are identified from standard on-track maneuvers conducted at different tire temperatures, without the need for additional indoor rig testing. Experimental validation on a race track demonstrates that incorporating tire temperature adaptation and combining dynamic and kinematic estimation significantly enhance estimation accuracy, particularly underow-grip and high-performance driving conditions attested by a reduction of 40–50% in RMS error and a further reduction in maximum absolute error.

1. Introduction

Accurate real-time estimation of the vehicle sideslip angle is essential for both active safety systems and performance-oriented control, particularly for yaw stability management [1]. Direct measurement of this variable typically requires either dual-antenna GPS systems or non-contact optical sensors. The former can provide the velocity of two points on the vehicle chassis to reconstruct the overall velocity vector and sideslip angle, but it suffers from packaging constraints andow sampling rates (typically 1 Hz), which are insufficient for dynamic estimation. Optical sensors, on the other hand, employ high-frequency cameras to detect the vehicle’s ground speed and direction with excellent precision, but they are expensive and must be installed with a clear and unobstructed view of the road surface—posing integration challenges, especially for compact vehicles.

Given theimitations of direct measurement systems, observer-based and sensor-fusion estimation methods have been widely investigated, including inertial-based observers [2], inertial-GPS fusion approaches [3], and optimization-based constrained estimation frameworks [4]. Ref. [5] provides the optimal filtering formulations for several model-based vehicle state observers. These works have explored both kinematic and model-based approaches, and in some cases, adaptive schemes that account for variations in tire working conditions such as pressure, temperature, and wear [6]. The main objective of these efforts has been to develop robust and accurate sideslip estimation methods suitable for a wide range of driving scenarios. For instance, refs. [2,7] proposed a combined approach integrating dynamic estimation with a kinematic sideslip derivative. This pseudo-integration strategy improves robustness to modeling uncertainties, although the underlying dynamic model assumes ainear relation between tireateral force and slip angle, eading to grip overestimation. Furthermore, their validation wasimited toateral maneuvers, without evaluating behavior at theimits of adhesion.

Unmodeled effects such as road conditions, tire parameter uncertainty, and parameter drift can significantly degrade estimation accuracy and the performance of model-based control systems. Jonathan et al. [8] showed that tire temperature and wear effects introduce significant variability in observed vehicle behavior during automated drifting maneuvers using nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC). Similarly, Kobayashi et al. [9] introduced a tire model that explicitly accounts for the temperature dependence of tire–road friction by incorporating a temperature state dynamic into vehicle trajectory planning, and validated its impact on automated drifting control performance through LQR-based experiments on a full-scale platform.

As highlighted in the review [10], several adaptive strategies have been proposed to address these issues through online tire-parameter updating for vehicle dynamics state estimation applications. Ahangarnejad et al. [11] employ a dual-EKF architecture to jointly estimate vehicle states and tire parameters, while Naets et al. [12] propose a two-stage estimator that performs online identification of tire model parameters.

In [6], an adaptive tire model and a UKF-based axle force observer were introduced to estimate sideslip angle. However, this method relies on extensive indoor tire testing, which is costly and difficult to replicate under real driving conditions. The model also considers only pureateral tire dynamics, imiting its applicability when combinedongitudinal andateral forces occur.

To overcome theseimitations, this work presents a temperature-adaptive sideslip angle estimation strategy that combines the strengths of kinematic and model-based approaches within an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) framework. The proposed method dynamically adjusts the internal tire model using a temperature-adaptive Pacejka formulation derived directly from on-track experiments. Starting from a baseline .tir file, the Pacejka parameters are rescaled using data from standard track maneuvers performed at different tire temperatures, thus avoiding the need for additionalaboratory testing.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the case study vehicle, the experimental setup, and the test procedures. Section 3 describes the sideslip angle estimation algorithm, emphasizing the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) architecture, the kinematic contribution, and the temperature-adaptive Pacejka tire model. Section 4 presents the experimental validation, including both pureateral maneuvers and a complete trackap. The numerical results are analyzed and discussed in Section 5, focusing on estimation accuracy through RMS error, and Maximum Absolute Error metrics. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the main findings and outlines directions for future work.

2. Case Study Vehicle and Equipment

This study was conducted using an FSAE vehicle, shown in Figure 1, instrumented with several sensors for data acquisition during on-track testing and validation. The main measurements were provided by an IMU–GNSS N-Ellipse unit from SBG Systems [13], which supplied yaw rate (r) as well asateral andongitudinal accelerations ( and ) with a sampling frequency of 200 Hz. Ground speed components ( and ) were measured using a Correvit S-Motion non-contact optical sensor from KISTLER (Winterthur, Switzerland) [14] with a sampling frequency of 500 Hz. From these quantities, the total speed magnitude (V) and vehicle slip angle () were derived. The lateral speed component was corrected to account for the distance between the vehicle’s center of gravity (CoG) and the sensor position, as well as the measured yaw rate. The steering wheel angle () was measured using an RM08 rotary magnetic encoder from RLS (Lake Mary, FL, USA) [15], a compact and high-speed sensor specifically designed for dynamic applications with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. Temperature acquisitions are performed with a needle probe pyrometer HPM5 by Prisma Electronics (Pineto, TE, Italy), with an accuracy of ±0.1 °C. All track tests were carried out using the FSAE vehicle, whose main characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Relevant equipment for track tests: (a) Correvit S-Motion non-contact optical sensor mounted at the back of the vehicle, employed to measure the magnitude of vehicle speed and slip angle; (b) test vehicle.

Table 1.

Squadra Corse PoliTo FSAE vehicle data.

The test campaign comprised several maneuvers designed to evaluate the vehicle dynamics and estimator performance under different conditions. The Double Lane Change (DLC) test, adapted from the standard automotive procedure, was executed at full throttle with the vehicle powerimited to 12 kW, resulting in an entry speed of approximately 50 km/h. A Slalom maneuver with cone spacing of about 8 m was performed, during which the driver was instructed to brake at the entry gate and accelerate at the exit. The Constant Radius Cornering (CRC) test was conducted on a circular path with a radius of 10 m to characterize tire behavior and to identify the required parameters, while a Steering Sine Sweep maneuver was carried out at various speeds to validate slip angle estimation. Finally, a complete Track Lap was performed on the test circuit, approximately 350 m inength, featuring tight corners and a maximum speed of around 80 km/h, with an averageap time of about 30 s. This test was used to assess the estimator performance under combinedongitudinal andateral dynamic conditions.

For each maneuver and each tire, tread temperatures were measured immediately after the test using the tire pyrometer at three positions (inner, middle, and outer). The mean of these three measurements was taken as the representative tire temperature. It should be noted that, due to the ambient conditions during testing, tire operating temperatures were relativelyow—ranging between 20 and 45 °C—whereas the optimal working temperature for this type of tire is approximately 60 °C. Data obtained with tire temperatures are available and are used to fit the model up to 65 °C. Nonetheless, these conditions are still considered representative for two reasons: first, this category of vehicle typically operates with relatively cold tires; and second, ow-grip scenarios generally present the most challenging conditions for vehicle dynamics estimation and control.

3. Side Slip Angle Estimation Algorithm

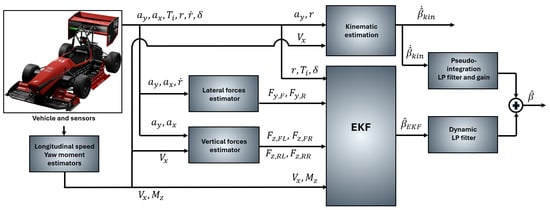

Figure 2 describes the proposed vehicle slip angle estimation strategy, inspired by [2] but with tire temperature compensation. It is a comprehensive multi-sensor fusion architecture designed for the robust estimation of the vehicle sideslip angle (). The methodology combines estimates from two parallel processing streams:

Figure 2.

Estimator architecture: Longitudinal vehicle speed is estimated by another model, as for . Vertical andateral forces estimator equation are reported respectively in Equations (8)–(11) and in Equations (13) and (14). Kinematic estimator equations are reported in (2) and (3). EKF internal model equations are reported in (4) and (5). The pseudo integrator and the Dynamic LP filters are presented in Equation (1).

- 1.

- Kinematic Estimation Path: Utilizing sensor inputs such asateral acceleration (), yaw rate (r), and longitudinal velocity (), the kinematic estimation block provides a responsive but drift-prone estimate (). This estimate is subsequently processed by a pseudo-integration LP filter and gain block to mitigate integration drift.

- 2.

- Dynamic Estimation Path: The second path employs an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) based on a dynamic vehicle model. The EKF combines direct sensor measurements (), other relevant estimates (), with the estimatedateral forces from theateral force estimator () and the verticaloads from the vertical force estimator (). The EKF produces a stable, model-based estimate of the sideslip angle (), which remains reliable even when kinematic data are unavailable or noisy.

The final, high-fidelity sideslip angle estimate () is achieved by fusing (summing) the outputs of the two processed streams as in [2]. This architecture capitalizes on the short-term accuracy of the kinematic approach and theong-term stability of the dynamic EKF to produce an accurate and noise-resistant estimate across all driving conditions.

where is the time constant of the filters and is set to , following [2].

3.1. Kinematic Estimator

The kinematic estimator equations are reported in (2) and (3). The integration of the kinematic slip angle time derivative cannot be implemented in real world applications because it is affected by drifting induced by bias errors in the IMU [16,17].

The case-study vehicle exhibited a roll gradient such that the roll angle was extremely small. It was therefore reasonable to assume it to be zero in order to simplify the equations and measurements.

3.2. Model-Based Estimator

The model based estimator consists in an Extended Kalman Filter. The well known estimation algorithm is reported in appendix from [18]. The vehicle dynamics are represented by the following non-linear continuous-time differential equations:

with and as front and rear wheelbase, and t as the track of the vehicle equal for front and rear axles. is the estimated yaw moment commanded by the torque vectoring and traction control installed on the vehicle and induced by groundongitudinal tire forces. Lateral forces are calculated from a Pacejka tire model fed with vertical forces, tire temperature, and tire side slip angles. The latter are calculated as follows:

with and as theongitudinal andateral component, respectively, of the vehicle speed, such that . A detailed description of the tire model calibration process is provided in Section 3.4. Vertical forces are estimated as in Equations (8)–(11), starting from known vehicle parameters, vehicle speed, and accelerations through a rigid body, modeled as

The terms are the aerodynamic repartition between front and rear axles, taking into account for theoad shift due to aerodynamic drag force as well. These are important when the vehicle has an important aerodynamic downforce and an uneven distribution of the generated forces: aerodynamic force balance has an effect on the vehicle balance (understeer or oversteer) that if not taken into account will induce an internal model mismatch with respect to reality. is the air density, and is the aerodynamic downforce coefficient. Yaw rate andateral acceleration are measured via the IMU, and a steering sensor provides the steering angle.

Equations (4)–(11) represent the nominal model of the vehicle and can be condensed to the non-linear time-domain representation

with the state vector , the yaw moment as the manipulated input, the steering angle () as the known disturbance input: . Vector umps the time-varying parameters:ongitudinal speed, ongitudinal acceleration, andateral acceleration of the chassis and tire temperatures, respectively, all assumed as measured quantities available from the vehicle control unit (VCU). Hereinafter, the non-linear system (12) is referred to as the nominal model of the vehicle and used by the EKF to predict the vehicle dynamics.

Regarding the measurements used in the update phase of the EKF, the lateral forces (, ), estimated from inertial measurements, are added as measured quantities [18,19]:

The measured yaw acceleration was obtained through real-time filtering using a Kalman filter specifically designed and tuned for derivative estimation. The measurement vector, used during the update phase of the estimator, is given by

with the measured and found with a bicycle model as in Equations (13) and (14).

The algorithm is implemented through the Euler discretization method with a sampling time of 0.01 s. The process and measurement covariance matrices are defined as follows and are assumed to be time-invariant:

The state vector is always initialized at since for all the maneuvers the initial vehicle motion is in a straightine. The initial error covariance matrix is set equal to Q.

3.3. Internal Model Mismatches: The Need of an Adaptive Pacejka Model

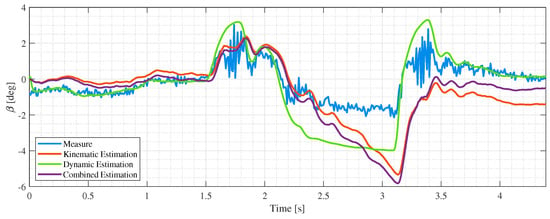

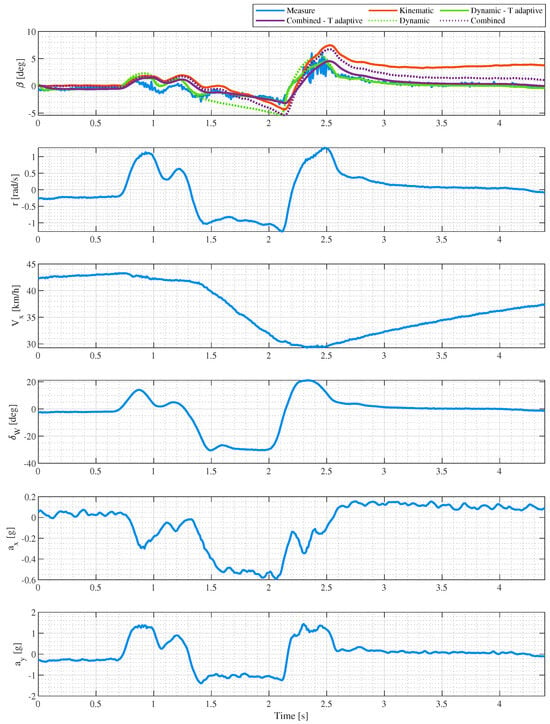

The above-mentioned model is implemented with a given and validated Pacejka tire model, found with the tire in optimal condition regarding the temperatures, and it has already been rescaled to suit the track application in order to adapt the actual grip, cornering stiffness and saturation characteristics. Results for these implementations are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, which report the kinematic estimation , the EKF estimation , and the combined estimation versus the measured slip angle duringow tire temperature maneuvers.

Figure 3.

Slip angle estimation with a standard EKF and no tire model adaptation with respect to temperatures for a DLC maneuver with a tire temperatureower than .

Figure 4.

Slip angle estimation with a standard EKF and no tire model adaptation with respect to temperatures for a DLC maneuver with tire temperatureower than .

It can be noticed that the EKF contribution is stable but also fairly inaccurate since it overestimates the available grip and the vehicle slip angle. As a result, the combined estimation is not reliable enough, especially for a DLC maneuver in which the vehicle undergoes to an extreme understeer situation, exploiting the model of the tires in strong saturation.

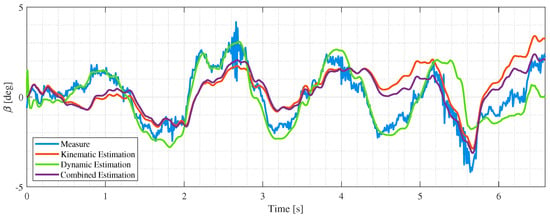

The behavior of the vehicle changes dramatically when tire temperatures drop below the correct working window. This affects the estimation capability of the EKF due to mismatches between real vehicle and internal model. In Figure 5, we reported a comparison between two CRC maneuvers run with different tire temperatures.

Figure 5.

On theeft side: vs. for two CRC runs at different tire temperatures, with the respective simulations held with a tuned Pacejka model (solidines). On the right side, a GG plot of the same maneuvers. The red and blue dashedines indicate the peakateral acceleration values obtained after post-processing the measurements for CRC runs at and , respectively.

Experimental points are obtained with Equation (14) and are associated with the maximum measured tire temperature betweeneft and right, the hotter tire happens to be the external one since it is the moreoaded. Solidines are obtained with simulations of CRC maneuvers with a Pacejka model that tries to replicate the very same behavior as in the real world. Lateral andongitudinal accelerations are displayed in a GG diagram as suggested by [20] to highlight the different available peakateral coefficient available: with hot tires, the vehicle can guarantee 1.9 g, while with cold tires, the maximum possible acceleration is below 1.5 g.

From the figures above, it is clear that is not just a matter of tuning the grip scaling coefficients due to differences between the test rig and track adherence, because a single Pacejka model parameter set cannot interpolate correctly both the maneuvers. There is an important relationship with tire temperature since all other parametersike vehicle setup, air temperature, track temperature, and general condition are extremely similar, since the tests have been performed in the same session.

3.4. Adaptive Model Formulation and Parameters Fitting

The following adaptive Pacejka tireateral model [21] has been chosen to have the temperature information to change the and saturation characteristic versus .

where is the camber angle, , and are the interpolated coefficients. The Jacobian matrices for the EKF are adapted with the new coefficients, not recomputed from scratch since temperature is not only measured by also slowly varying with respect to the states. An insight to the shown parameters can be found also in [22].

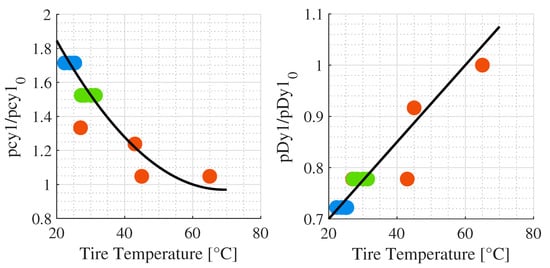

The above mentioned coefficients have been found with the a process that includes raw data filtering, Pacejka parameter fitting, and temperature-dependent coefficient fitting. During raw data filtering, axleateral forces and tire sideslip angles are filtered through a moving average filter, with a sliding window of 0.1 s. Then Pacejka parameters and from a nominal temperature set are rescaled in order to minimize the squared error between the predicted axle force and the measured force. Subsequently, the obtained values of and are fitted as functions of the temperature at which they were identified yielding temperature-dependent coefficients, again minimizing the squared errors between the predicted Pacejka coefficient and the fitted Pacejka parameters. The result is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Interpolation of temperature-dependent coefficients. On theeft, the relative change of is reported; this parameter affects tire behavior at saturation operating conditions (high sideslip angles). On the right, the relative change of , which is directly related to . The maneuvers used for the interpolation are CRC, DLC 1, and slalom 1, represented in orange, blue, and green, respectively.

A parabolic approximation has been chosen for behavior, while ainear model is used for . Each point represents a tire with its registered temperature, and points with the same color are associated with the same maneuver. To ensure the integrity of the results, the specific maneuvers utilized for tire model extraction were excluded from the validation dataset.

The registered tire temperatures are reported in Table 2. As mentioned, temperatures are measured for each tire at three different points at the end of the maneuver.

Table 2.

Table with tire temperature for the analyzed maneuvers.

It must be pointed out that, for this work, temperatures are acquired during testing but are processed offline. Once the thermal model is defined through interpolation with standard maneuvers, tire temperature is artificially kept constant to the measured value from the end of the test with, as a “maneuver-wise” adaptation.

4. Experimental Results

The new and temperature adaptive estimations, represented with a solidine, are compared to the standard non-adaptive ones, represented with dashed lines.

4.1. Slalom and DLC: Pure Lateral Maneuvers

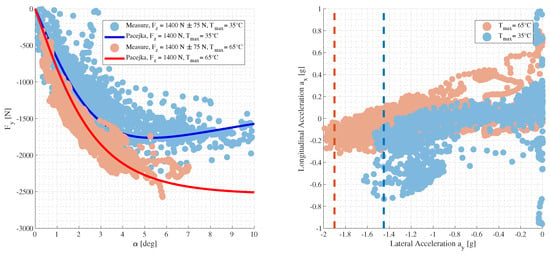

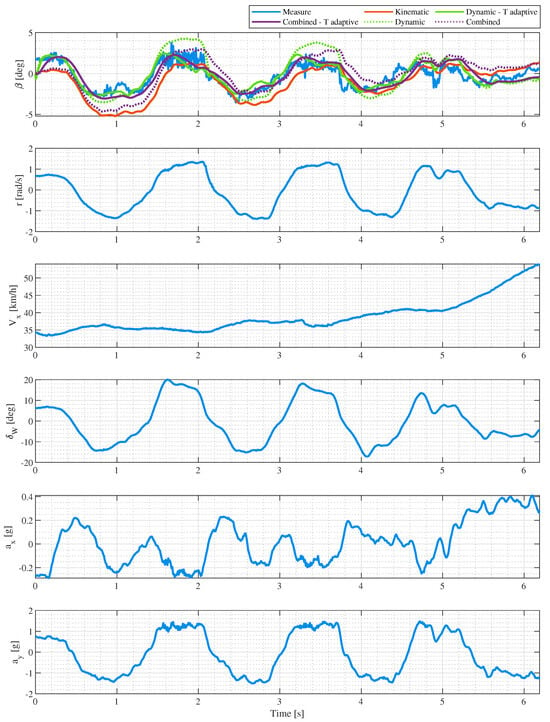

Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate the results concerning mainlyateral maneuvers: DLC and slalom, respectively. The internal model of the EKF should be much more reliable, since it is based on aateral only Pacejka and vehicle model, as it happens to be.

Figure 7.

Slip angle estimation with an adaptive EKF for a DLC maneuver with tire temperatureower than .

Figure 8.

Slip angle estimation with an adaptive EKF for a slalom maneuver with tire temperatureower than .

4.2. Track Lap: Combined Longitudinal–Lateral

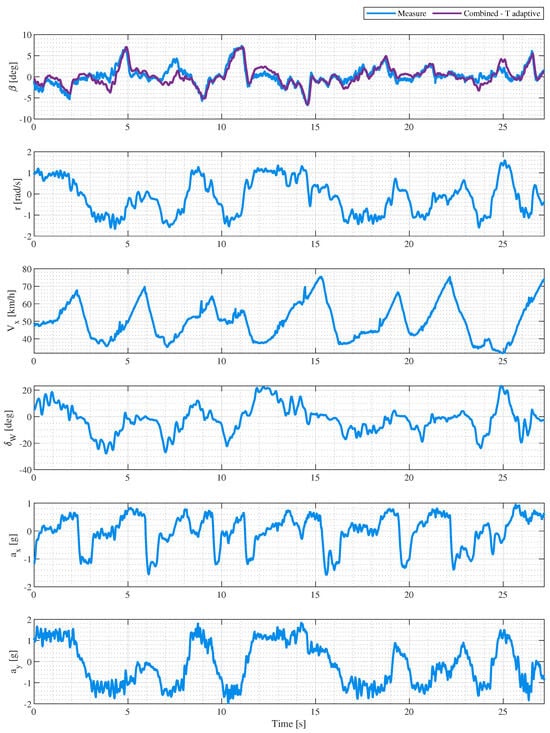

We have seen in previous figures that the EKF performs very well inateral operation. The estimation algorithm must work in all possible situations, that is, for a trackap when the vehicle is found to be at its adherenceimit in a combined operation that includes braking while cornering (trail braking) and strong acceleration at the corner exit, as in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Slip angle estimation with an adaptive EKF for a slalom maneuver with tire temperatureower than .

It can be seen that, during a trackap, the combined estimation with the temperature adaptation is fairly reliable. We want to highlight that the tests are performed with a racing vehicle that usually exploits up to 8 deg of side slip angle. The estimator works perfectly while tracking the slip angle peaks, which are, for sure, the most delicate situations for both performance and safety. It is evident how, during a trackap, the vehicle experiences bothateral andongitudinal accelerations simultaneously, meaning that the tires are in combinedongitudinal–lateral slip working points. Since the implementation presents a pureateral Pacejka tire model, there is aimit in the performance of the EKF. The accuracy during acceleration and braking is not completely degraded, but is still guaranteed by the kinematic component .

5. Discussion

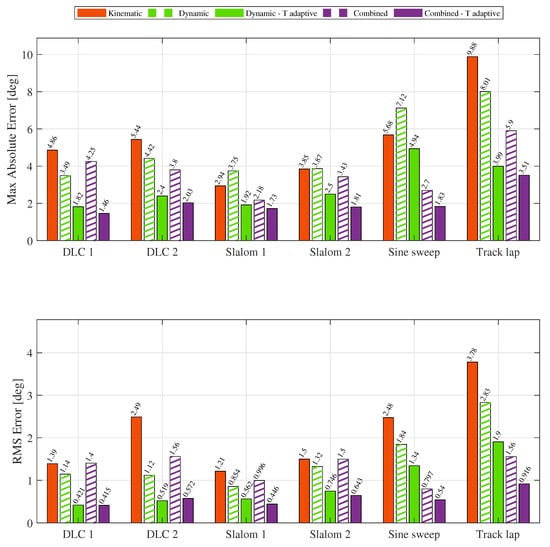

The accuracy is now numerically assessed byooking at Maximum Absolute Error and RMS Error between each of the possible estimations and measurement. The errors are reported in the bar chart in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Bar chart representing the performance of the different contributions for the combined estimator tested on a representative maneuver set, comprehensive of DLC, slalom, steering sine sweep, and a trackap. A comparison is performed between the EKF with non-adaptive model and the tire-dependent one. The figure shows results for both fitting and validation maneuvers described in Table 2.

The experimental validation confirmed that incorporating tire temperature adaptation within the EKF frameworkeads to a consistent improvement in sideslip angle estimation accuracy. Comparative analysis among the kinematic, dynamic, and combined estimators highlights distinct performance characteristics depending on the driving condition.

For purelyateral maneuvers (such as the DLC and slalom tests), the temperature-adaptive EKF provided a more accurate representation of the tire behavior across different operating temperatures. The lateral force prediction improved markedly, reducing the overestimation of available grip that occurred with non-adaptive models. Consequently, the combined estimator (kinematic plus EKF) achieved theowest RMS and maximum absolute errors in these tests, demonstrating the benefits of integrating tire thermal effects in scenarios dominated byateral dynamics.

During mixedongitudinal–lateral maneuvers, such as the complete trackap, the adaptive EKF maintained good correlation with the measured slip angle, especially around peak sideslip conditions. However, residual discrepancies remained due to the simplifiedateral-only tire model and the absence ofongitudinal slip coupling. These effects become significant during combined braking and acceleration phases, where the trade-off betweenongitudinal andateral force capacity alters the tire’s effective stiffness. The adaptive model partially mitigates these discrepancies by adjustingateral stiffness with temperature, but cannot fully capture combined-slip behavior.

The statistical performance metrics shown in Figure 10 further substantiate these findings. The temperature-adaptive model consistently reduced RMS errors by up to 40–50% across all maneuvers. In particular, the DLC and slalom tests highlight a clear reduction in both RMS and maximum absolute errors when compared with the non-adaptive EKF, confirming the benefits of incorporating tire temperature effects into the estimation loop.

Nevertheless, Figure 10 also reveals that, in some cases, especially during pureateral maneuvers, the combined estimator offers only marginal improvements over the adaptive dynamic EKF alone. This behavior suggests that, once the adaptive tire model compensates for most of the internal model mismatches, the contribution from the kinematic path becomesess dominant in steady-state conditions.

Two additional aspects emerged as crucial for future development. First, tire temperature measurements obtained only at the end of each test are insufficient to fully capture the fast transient behavior observed during trackaps. As specified at the end of Section 3.4, the presented results are obtained through a “maneuvers-wise” tire temperature adaptation, not an online measurement and processing. Implementing real-time infrared temperature sensing would provide the necessary temporal resolution for online model adaptation. Second, the lack ofongitudinal dynamics in the current EKFimits its capability under aggressive acceleration or braking, indicating the need for a combined-slip elliptical tire model and enhanced measurement fusion.

Overall, the proposed adaptive EKF demonstrates a strong balance between modeling accuracy and implementation practicality. It effectively bridges the gap betweenaboratory-calibrated tire models and real-world conditions, providing a robust foundation for high-performance vehicle state estimation and control.

6. Conclusions

This work presented a temperature-adaptive Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) for real-time sideslip angle estimation, validated experimentally on a Formula Student electric race car. The proposed approach integrates a temperature-dependent Pacejka tire model within a dual-track 3-DoF vehicle model, combining dynamic and kinematic estimation paths to enhance accuracy across a range of operating conditions.

The experimental results demonstrated that introducing tire temperature adaptation significantly improves estimation accuracy, particularly underow-grip and cold-tire scenarios. Quantitatively, the temperature-adaptive EKF reduced the RMS estimation error by up to 40–50% across the evaluated maneuvers compared to the non-adaptive baseline. The method showed the greatest benefits in pureateral maneuvers (DLC and slalom), where tire temperature has a dominant influence on cornering stiffness. During full trackaps, the adaptive EKF maintained reliable estimation performance even in transient conditions involving combinedongitudinal andateral forces.

Despite these encouraging results, certainimitations remain. The current EKF formulation does not explicitly includeongitudinal tire dynamics, and tire temperature is only sampled post-maneuver, whichimits responsiveness during highly dynamic tests. Future developments will focus on integrating real-time infrared temperature sensing, combined-slip tire modeling, and state observers capable of online adaptation to tire wear and pressure variations.

Moreover, this methodology is easily transferable since the estimator is completely model-based. The relevant data for tire model fitting can be obtained with few sensors, some of which are already standard in the automotive industry. The needed tests can be performed in any dynamic platform as well as in a racetrack according to vehicle utilization and range of speed. Other Pacejka parameters can be introduced in order to rescale the actual peak gripevel of a new unknown racetrack without modifying the temperature response of the tire only.

Overall, the proposed framework provides an effective and practical compromise between model complexity, calibration effort, and estimation robustness. By relying solely on standard on-track tests to parametrize the adaptive tire model, the approach avoids expensiveaboratory procedures while maintaining high accuracy—making it suitable for both motorsport applications and advanced vehicle dynamics control systems in broader automotive contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M., L.M.C.M. and A.T.; methodology, A.M., R.M. and L.M.C.M.; software, A.M. and R.M.; validation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., R.M. and L.M.C.M.; writing—review and editing, L.M.C.M. and A.T.; supervision, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the LIM Mechatronics Lab, Politecnico di Torino (Turin, Italy), for providing the Correvit S-Motion non-contact optical sensor (Kistler) employed during the experimental campaign.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rajamani, R. Vehicle Dynamics and Control; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Piyabongkarn, D.; Rajamani, R.; Grogg, J.A.; Lew, J.Y. Development and Experimental Evaluation of a Slip Angle Estimator for Vehicle Stability Control. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2009, 17, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Gerdes, J.C. Integrating inertial sensors with GPS for vehicle dynamics control. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2004, 126, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, G.C.; Doná, J.A.; Seron, M.M. Constrained Control and Estimation: An Optimisation Approach; Springer Science & Business Media: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, D. Optimal state estimation: Kalman, H Infinity, and Nonlinear Approaches; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.B. Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation Based on Tire Model Adaptation. Electronics 2019, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, A.; Tozu, K.; Yamaguchi, H.; Asano, K.; Amano, Y. Development of Vehicle Stability Control System Based on Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation. SAE Trans. 2001, 110, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan, Y.M.G.; Thompson, M.; Dallas, J.; Balachandran, A. Beyond the stable handlingimits: Nonlinear model predictive control for highly transient autonomous drifting. Int. J. Veh. Mech. Mobil. 2024, 62, 2590–2613. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T.; Weber, T.P.; Gerdes, J.C. Trajectory planning using tire thermodynamics for automated drifting. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 2–5 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 2103–2109. [Google Scholar]

- Chindamo, D.; Lenzo, B.; Amodeo, S.; Dalla Via, L.; Sakhnevych, A. On the Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation: A Literature Review of Methods, Models, and Innovations. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangarnejad, M.; Ordys, A.; Askari, M.; O’Neill, E.; Iravani, P. ADAP-TYRE DEKF Filtering for Vehicle State Estimation Based on Tyre Parameter Adaptation. Int. J. Veh. Dyn. 2016, 2, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naets, B.; Van Aalst, H.; Desmet, W. Design and Experimental Validation of a Stable Two-Stage Estimator for Automotive Sideslip Angle and Tyre Parameters. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 4573–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SBG Systems. Ellipse Series—Hardware Manual. Available online: https://support.sbg-systems.com/sc/el/files/latest/102924736/102924734/1/1720519483812/Ellipse+3+-+Hardware+Manual.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Kistler. Correvit S-Motion. Available online: https://kistler.cdn.celum.cloud/SAPCommerce_Download_original/003-395e.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- RLS. RM08. Available online: https://www.rls.si/eng/rm08-super-small-non-contact-rotary-encoder (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Selmanaj, D.; Corno, M.; Panzani, G.; Savaresi, S.M. Vehicle sideslip estimation: A kinematic based approach. Control Eng. Pract. 2017, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.; Madau, D.; Ashrafi, B.; Brown, T.; Recker, D. Technical challenges in the development of vehicle stability control system. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE International Conference on Control Applications (Cat. No.99CH36328), Kohala Coast, HI, USA, 22–27 August 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, L.M.C.; Manca, R.; Hegde, S.; Amati, N.; Tonoli, A. Predictive handlingimits monitoring and agility improvement with torque vectoring on a rear in-wheel drive electric vehicle. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2024, 62, 2185–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheli, F.; Sabbioni, E.; Pesce, M.; Melzi, S. A methodology for vehicle sideslip angle identification: Comparison with experimental data. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2007, 45, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, W.F.; Milliken, D.L.; Metz, L.D. Race Car Vehicle Dynamics; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pacejka, H.B. Tyre and Vehicle Dynamics, 3rd ed.; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Genta, G.; Morello, L. The Automotive Chassis: Volume 1: Components Design; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Chapter 2; pp. 53–132. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.