Abstract

The application of remote sensing technology for pose estimation in beekeeping has the potential to transform colony management, improve bee health and mitigate the decline in bee populations. This paper presents a novel bee pose estimation method that integrates the accuracy and efficiency of two existing deep learning models: a variant of the classic VGG-19 network architecture for feature extraction and an adaptation of OpenPose for part detection and assembly. The proposed approach, OpenBeePose, is compared with state-of-the-art methods, including YOLO11 and the original OpenPose. The dataset used consists of 400 high-resolution images of the hive ramp (1080 × 1920 pixels) taken during daylight hours from eight different hives, totaling more than 3600 bee samples. Each bee is annotated in the YOLO format with two key points labeled: the stinger and the head. The obtained results show that OpenBeePose achieves a high level of accuracy, similar to those of other methods, with a success rate exceeding 99%. However, the most substantial advantage is its computational efficiency, which makes it the fastest method among those compared for 540 × 960 images, and it is almost twice as fast as OpenPose.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, pose estimation has emerged as a prominent topic, with significant advancements occurring in conjunction with the rapid development of deep learning methods. Due to hardware constraints, these networks were initially utilized in rather simplistic ways, with the capacity to process only small images or patches. In contrast, state-of-the-art networks exhibit substantially higher efficiency and capabilities [1]. Within this context, remote sensing is becoming increasingly relevant, as non-invasive imaging technologies, such as fixed and mobile cameras, enable the continuous monitoring of living organisms without physical contact. In beekeeping, the camera-based observation of hive entrances provides a remote sensing modality that captures high-resolution behavioral data, which can then be analyzed using deep learning-based pose estimation.

The problem of pose estimation involves identifying keypoints in images, which can represent various parts of a person, animal, or plant, such as joints, landmarks, or other distinct features. These parts correspond to salient points within an image or video that are critical for biosystems analysis tasks such as object identification, description, or scene feature matching. The process of pose estimation is based on algorithms that frequently use repetitive techniques to determine the closest points. The fundamental concept underpinning this process revolves around establishing a correlation between two-dimensional (2D) image features and points on a three-dimensional (3D) model. However, it is important to note that these algorithms may not be suitable for images in which objects are partially occluded. The identification of keypoints of an object within an image typically involves the application of feature detection algorithms.

Pose estimation has been applied in a variety of domains [2,3], including healthcare (patients’ movements during physical therapy), sports (biomechanical analysis of athletes), entertainment (motion capture to create realistic animations in movies), manufacturing (human–robot interaction), and agriculture (plant and animal monitoring). Despite years of research in human and animal body pose estimation, several challenges remain partially unsolved. Key issues include variations in animal appearance across images, changes in body structure, partial occlusions caused by self-articulation or overlapping objects in the scene, the inherent complexity of animal skeletal structures, and the high dimensionality of pose configurations.

Ongoing research in related areas, such as gesture tracking, could further increase productivity and usefulness in different domains. For example, Li et al. [4] introduced the FasterNest Block and Depth Block to enhance cattle pose estimation using the RTMPose model. The FasterNest Block, featuring a three-branch structure, significantly improved the accuracy without compromising the inference speed. The Depth Block, utilizing depth-wise separable convolutions, achieved accuracy of 82.9% on a cattle dataset. Farahnakian et al. [5] applied five deep learning networks, namely ResNet50, ResNet101, MobileNet, EfficientNet, and DLCRNet, for piglet pose estimation. The experimental results indicated that MobileNet successfully detected seven body parts of the piglet with a median test error of 0.61 pixels. Another algorithm was introduced by Wei et al. [6] for the automatic detection of cow conditions in real farms based on spatiotemporal features of the skeleton. A total of 780 images were used to validate three poses, which were standing, walking, and lying down. Fang et al. [7] employed a deep neural network approach to estimate the posture of chickens. Their method achieved a standard deviation of 0.013 for precision and 0.027 for recall.

Concerning the specific case of bee pose estimation, Sledevič et al. [8] studied this problem using YOLOv8 models. Bounding boxes were annotated with keypoints to indicate the orientations of the bees using two points, one for the head and another for the stinger. The results showed accuracy of over 98%. It is also noteworthy that the authors provided a publicly available dataset of bees traversing the beehive ramp in the wild. On the other hand, the work of Smith et al. [9] studied the behavior of bumble bee colonies. In their research, a proprietary dataset of 50 grayscale images was used, which were downsampled to a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels. Pose estimation was performed using Social LEAP Estimates Animal Pose (SLEAP), which is based on a specialized U-Net network. In this case, the images were taken inside the hive.

Another related method was proposed by Bozek et al. [10]. They studied the detection and orientation of bees inside hives, using a dataset of 720 images extracted from a grayscale video. The images were analyzed using a U-Net network architecture specifically designed for this purpose, incorporating an identity and orientation loss function. Finally, Rodriguez et al. [11] also studied the poses of bees at the entrances to hives, although they performed a more detailed analysis based on the head, thorax, abdomen, and left and right antennae. The pose detector architecture was based on a backbone using VGG-19, followed by the part affinity fields (PAF) approach for part-to-part associations. Although the images in the dataset were captured at a high resolution, the model processed them at a resolution of 640 × 360 pixels.

Surprisingly, none of the existing bee monitoring works mention the use of OpenPose [12], a popular method originally designed for multi-person pose detection that has also been successfully applied to animals [13]. OpenPose comprises several steps that were introduced in previous studies: a VGG-19 backbone for feature extraction; a multi-stage convolutional neural network (CNN) with several stages for generating PAFs and part confidence maps; and the final matching of parts using the Hungarian algorithm. Only in the paper by Padubidri et al. [14] was the bee pose estimated using a method similar to OpenPose. In their approach, the PAF stages were replaced with part affinity confidence masks, and the Hungarian algorithm with a greedy inference method was used to connect the bee parts. However, the authors were more interested in counting the total number of bees than in accurately estimating the pose, which was only used to determine whether the bees were entering or leaving the hive.

In summary, monitoring bee activity in beehives plays a vital role in improving hive management and gaining a deeper understanding of their behavior. Estimating the poses of individual bees allows their movements to be tracked more accurately, enabling population dynamics to be assessed and the effects of environmental factors on their lives to be evaluated. This approach offers valuable insights into hive health and the wider ecosystem, enabling more effective conservation and intervention strategies to be developed. Thus, the goal of this work was to design a new pose estimation method that achieves performance comparable to that of current state-of-the-art techniques across a range of evaluation metrics, while surpassing them in inference speed. The proposed method, termed OpenBeePose, is based on OpenPose and involves several adaptations to the feature extraction and multi-stage CNN networks. These adaptations improve the efficiency while maintaining high accuracy in locating bees, making OpenBeePose suitable for real-time applications where fast decision-making is critical.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset for Bee Pose Estimation

When experimenting with machine learning systems, it is crucial to select datasets that are large and varied enough to train the models correctly. Using public datasets also allows different methods to be compared and promotes open science. For these reasons, a public dataset of bee images was chosen. Specifically, the dataset [15] provided by Sledevič et al. [8] comprises 400 photos with a resolution of 1080 × 1920 pixels, captured from 8 beehives and totaling 3668 bees. Some samples are shown in Figure 1. These images, taken from above the beehive ramp during daylight, are annotated in the YOLO format [16] with two keypoints per bee: the stinger and the head. A random split with the seed value set to 42 was used to allocate 70% of the data for training (2560 bees), 20% for validation (729 bees), and 10% for testing (379 bees). The same split was applied in all subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Sample images from the bee dataset [15].

2.2. Bee Pose Estimation with OpenPose

Two-dimensional pose estimation involves understanding objects in an image by localizing their joints [16]. These methods are generally categorized into two approaches: top-down and bottom-up. Top-down methods [17,18,19,20,21] first detect objects and then estimate their poses individually. By contrast, bottom-up methods [22,23,24] first identify keypoints regardless of their object associations and then group them into individual instances.

OpenPose [12] is a good example of a bottom-up method for pose estimation. It is a real-time, multi-object human pose estimation framework that employs a state-of-the-art deep learning approach. It uses the concepts of confidence maps, which represent the likelihood of finding object parts, and part affinity fields (PAFs) to associate body parts with specific individuals in an image. PAFs and confidence maps are processed through separate CNN branches, with both branches being updated at each stage of training. Each block in the architecture consists of five 7 × 7 convolutional layers and two 1 × 1 convolutional layers. For feature map generation, the model uses the first 10 layers of VGG-19, which are fine-tuned during training [25].

In a later update of the OpenPose method, the conventional architecture of 7 × 7 convolutional layers was replaced with three successive 3 × 3 convolutional layers, thereby reducing the computational cost and enabling faster inference while preserving the receptive field. In addition, the outputs of these three layers are concatenated, following a strategy similar to DenseNet [26]. Interestingly, the method proposed in OpenPose is so generic that it has been applied not only to people but also to animals and plants [13].

2.3. Bee Pose Estimation with YOLO-Pose

You Only Look Once (YOLO) [16] is a 2D multi-object detection framework that formulates the task as a regression problem rather than a classification problem. Since its inception in 2015, YOLO has been successfully extended to classification, segmentation, tracking, and pose estimation problems. In the present study, a variant called YOLO-Pose [27] was used—specifically, YOLO11-Pose. A key advancement in YOLO11 is the introduction of the cross-stage partial with kernel size 2 (C3k2) block, which replaces the C2f block used in previous versions. This modification decomposes a large convolutional block into two smaller ones, resulting in faster processing, similar to the approach used in YOLOv8. Additionally, YOLO11 integrates the Spatial Pyramid Pooling—Fast (SPPF) module from previous versions and introduces a new convolutional block with parallel spatial attention (C2PSA) block. The C2PSA block boosts spatial attention within the feature maps, allowing the model to focus more effectively on important regions in the image.

To improve the comparison, YOLOv8-Pose was also used in the experiments. In both cases, the specific fine-tuning of the YOLO models was performed using the bee dataset, with 70% of the bee samples for training and 20% for validation, which was the same in all experiments.

2.4. Bee Pose Estimation with OpenBeePose

The method proposed in the present work, OpenBeePose, has been designed as a variant or adaptation of OpenPose for the specific case of bees. The goal is to maintain, or even improve, the accuracy metrics in pose estimation while increasing its computational efficiency. The proposed variations mainly concern image preprocessing, feature extraction, and the multi-stage CNN networks with PAFs and confidence map branches.

- Concerning image preprocessing, a small initial step was added to the original method, consisting of normalizing the RGB values of the input images. The images, in RGB format, were normalized per channel using the mean and standard deviation values from ImageNet [27], as shown in Table 1. This pre-normalization aimed to improve the weighting between the different channels, enabling the convolutional models to subsequently be fitted more accurately.

Table 1. Normalization of the mean and standard deviation values for each input channel.

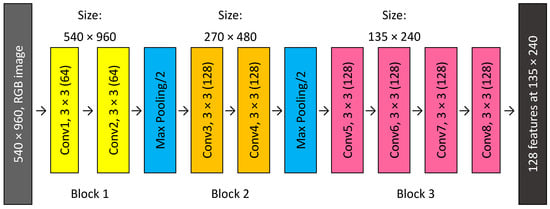

Table 1. Normalization of the mean and standard deviation values for each input channel. - In the feature extraction step, the first 10 layers of the VGG-19 network architecture [25] (which were used for feature extraction in OpenPose due to their superior performance compared to other backbone networks) were also employed in OpenBeePose. This part of the network consists of 8 convolutional layers and 2 max pooling layers, applying 3 × 3 convolutions. However, two important adaptations were made. First, instead of resizing the images to 224 × 224 pixels, as typically required by the VGG-19 architecture, the images were fed either at the full resolution of 1080 × 1920 pixels or at 540 × 960 pixels to preserve the details necessary for accurate bee pose estimation. Experiments were conducted to test both alternative sizes. Secondly, the resulting number of features that are later fed into the multi-stage CNNs was reduced to 128, instead of 256. The proposed network architecture is presented in Figure 2 for the case of 540 × 960 images.

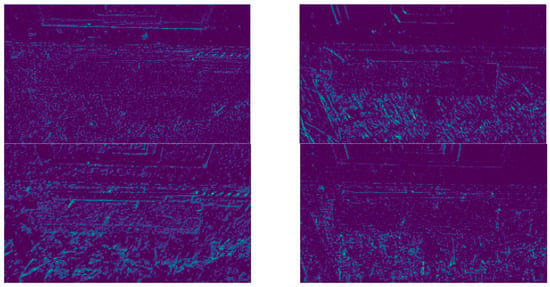

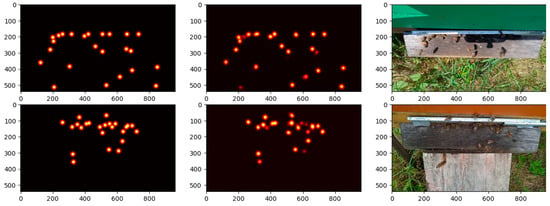

Figure 2. Architecture of the feature extraction network, based on the first 10 layers of VGG-19. “Conv1, 3 × 3 (64)” means convolutional layer 1, with 64 convolutions of size 3 × 3.This approach significantly reduces subsequent calculations, thereby improving the system’s efficiency. Although this involves reducing the amount of information available for later stages, the fact that our problem is more specific than that of OpenPose means that the number of 128 features is sufficient for our domain of interest.After processing the images through this feature extraction network, the output dimensions (width and height) are reduced by a factor of 4, since the network uses two pooling operations with a stride of 2, resulting in 128 feature maps of size 270 × 480 pixels for the full-resolution images and 135 × 240 pixels for the half-sized images. Figure 3 shows some of these features extracted by our VGG-19 variant for several sample images. Notably, YOLO models bypass VGG-19 entirely because they extract feature maps using their own convolutional layers.

Figure 2. Architecture of the feature extraction network, based on the first 10 layers of VGG-19. “Conv1, 3 × 3 (64)” means convolutional layer 1, with 64 convolutions of size 3 × 3.This approach significantly reduces subsequent calculations, thereby improving the system’s efficiency. Although this involves reducing the amount of information available for later stages, the fact that our problem is more specific than that of OpenPose means that the number of 128 features is sufficient for our domain of interest.After processing the images through this feature extraction network, the output dimensions (width and height) are reduced by a factor of 4, since the network uses two pooling operations with a stride of 2, resulting in 128 feature maps of size 270 × 480 pixels for the full-resolution images and 135 × 240 pixels for the half-sized images. Figure 3 shows some of these features extracted by our VGG-19 variant for several sample images. Notably, YOLO models bypass VGG-19 entirely because they extract feature maps using their own convolutional layers. Figure 3. Sample features obtained for some images of the bee dataset using the proposed feature extraction network. The feature maps are one-quarter of the size of the input images.

Figure 3. Sample features obtained for some images of the bee dataset using the proposed feature extraction network. The feature maps are one-quarter of the size of the input images. - The second major component of OpenPose is the multi-stage CNN networks with PAF and confidence map branches. Instead of the original OpenPose architecture, an alternative architecture with an iterative prediction mechanism was applied, inspired by Wei et al. [28], that refines predictions over successive stages. In this method, PAFs are updated in the first T stages, followed by updates to the confidence maps in the subsequent T stages. This approach contrasts with [29], where both the PAFs and the confidence maps are refined simultaneously at each stage.

In addition, rather than using the conventional six-stage architecture employed by OpenPose [12], OpenBeePose comprises only four stages to improve real-time inference and prevent gradient vanishing issues. This consists of 2 stages for the PAF network and 2 stages for the confidence maps. Experiments have shown that using four stages is the most effective way to learn PAFs. Furthermore, the number of channels in the intermediate convolutional blocks was reduced to 64 to reduce the size of the architecture and avoid overfitting. Finally, our adaptation permits the utilization of a custom sigma (the variance of the ground-truth confidence maps) and PAF width (the thickness of part affinity fields), which were not designated as hyperparameters in the original OpenPose paper.

The CNN networks of the multi-stage part were optimized using the Adam optimizer for the training of the proposed model. The model was trained for 40 epochs with a batch size of 8 and a learning rate of 0.00005. To generate ground truth representations, the hyperparameters PAF width and sigma were used for part affinity field (PAF) and confidence map generation, respectively. The model loss consists of two losses

where losspaf is the validation PAF error, and lossconf is the validation confidence map loss. Each of them is computed as a mean squared error.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

The primary metric used to evaluate and compare the pose estimation models is the mean average precision (mAP) [30], which is computed using object keypoint similarity (OKS). Additionally, performance is typically assessed using other metrics, including OKS [31,32,33], the percentage of correct keypoints (PCK) [34,35], percentage of correct parts (PCP) [36], mean per-joint position error (MPJPE) [1], precision, and recall [37]. For the sake of completeness, the definitions of all these metrics are included below.

Equation (2) provides the formula used for object keypoint similarity (OKS) for a single bee instance :

where represents the two keypoints of a bee ( for head and for stinger); is the Euclidean distance between the predicted keypoint and the ground-truth keypoint; is the scale of the object, defined as the square root of the bounding box area; is a per-keypoint constant that controls the falloff; and is the visibility flag of that keypoint.

The mean OKS (Equation (3)) over all images and instances is calculated as

where N is the total number of bees in the images. OKS is a crucial metric for this task because it provides scale invariance, keypoint-specific tolerance, and smooth error penalization. OKS is used to evaluate both the mAP@50 and mAP@50–95 in this paper. Specifically, mAP@50 is defined as the mean average precision computed using OKS at a threshold of 0.50, meaning that a predicted keypoint is considered correct if its OKS with the ground truth exceeds 0.50. In contrast, mAP@50–95 is the mean average precision computed over a range of OKS thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95 (in 0.05 increments), providing a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance over different varying levels of localization precision.

The PCK metric in Equation (4) measures the accuracy of the predicted keypoints by computing their proximity to the ground-truth keypoints. The PCK formula is

where M is the total number of keypoints across all images, is the predicted keypoint, is the ground-truth keypoint, is the scale factor (computed as the square root of the bounding box area, similar to OKS), and is the threshold. PCK@0.5 (with ) was used to evaluate the model. Equation (5) provides an alternative, computationally simpler formulation of PCK that calculates the metric for each bee individually before averaging the results over all instances:

For body part prediction evaluation, rather than keypoint prediction, the percentage of correct parts (PCP) is used. The PCP formula is given in Equation (6):

Here, the superscript (1) denotes the head, and (2) denotes the stinger. PCP evaluates whether the average distance of the predicted limb to the ground-truth limb is within a factor of the true limb length. In this study, ‘limb’ refers to the line segment connecting the head and the stinger. For our experiments, PCP@0.3 was used, meaning that .

To compute the mAP@50 and mAP@50–95, the precision (Equation (7)) and recall (Equation (8)) are first calculated at various OKS thresholds:

where is the number of correctly detected keypoints, is the number of incorrectly detected keypoints, and is the number of missed keypoints. The thresholds for computing , , are set based on OKS values.

Finally, the mean per-joint position error (MPJPE) measures the average Euclidean distance between the ground-truth keypoints and the predicted keypoints (see Equation (9)). MPJPE quantifies the model’s accuracy in keypoint localization by calculating the mean positional error across all joints:

2.6. System Information

The experiments were carried out using a high-performance computing system equipped with a 13th Gen Intel® Core™ i9-13900K processor (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA), paired with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The system was configured with 128 GB of RAM, running on Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS with the 6.8.0-52-generic Linux kernel. For deep learning computations, we utilized CUDA 11.8 to accelerate model training and inference. Our implementation was based on PyTorch 2.5.1, with Python 3.11.10 providing the programming environment.

As the proposed method is also intended for use with edge computing devices, the inference times were also tested on a low-end computer to simulate the average performance of such devices. This computer was a laptop with a 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-12700H processor at 2.30 GHz, configured with 16 GB of RAM, also running on Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS. In this case, the GPU was not used in the experiments. As model training is a one-time offline process, this computer was only used to measure inference times and not for training.

3. Results

In the following section, the results obtained by the proposed OpenBeePose model will be presented and compared with those of OpenPose and various versions of the YOLO models, in terms of accuracy and computational efficiency. As mentioned in Section 2, the dataset was randomly split, with 70% of the images used for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing. All models were trained or fine-tuned using the same data and with similar training parameters. For example, the number of epochs and training time were kept consistent.

3.1. OpenBeePose Results and Ablation Analysis

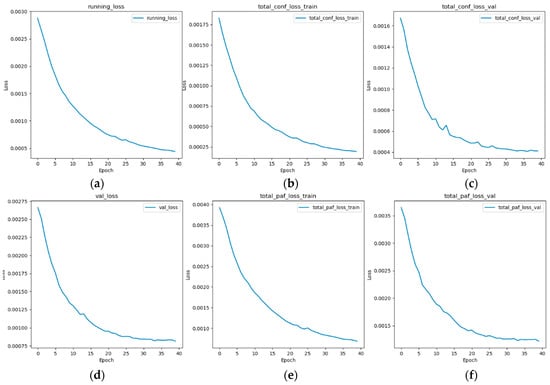

Figure 4 shows the loss functions during the training of the OpenBeePose model for 540 × 960 images. The smooth convergence shown in this figure indicates that the model is gradually approaching the optimal solution, and the similar decrease in both training and validation losses suggests that there is no overfitting. The gradual decrease in all losses confirms effective learning, with no sharp spikes or sudden increases that would indicate instability or divergence.

Figure 4.

Loss plots of OpenBeePose training on the bee dataset along 40 epochs. (a) Total training loss (sum of total_conf_loss_train and total_paf_loss_train). (b) Training confidence map loss. (c) Validation confidence map loss. (d) Total validation loss (sum of total_conf_loss_val and total_paf_loss_val). (e) Training PAF loss. (f) Validation PAF loss.

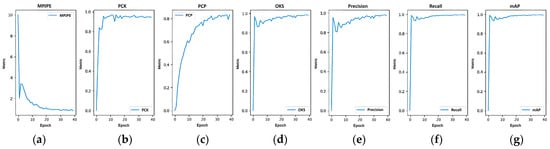

Figure 5 shows the progression of the evaluation metrics during OpenBeePose training for the 540 × 960 images. All evaluation metrics exhibit a smooth increase until reaching a stable peak, except MPJPE, where a lower value is preferable. This behavior suggests that the model is not only learning effectively, but it is also generalizing well.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the evaluation metrics over 40 epochs of training of OpenBeePose on the bee dataset. (a) MPJPE. (b) PCK. (c) PCP. (d) OKS. (e) Precision. (f) Recall. (g) mAP@50–95.

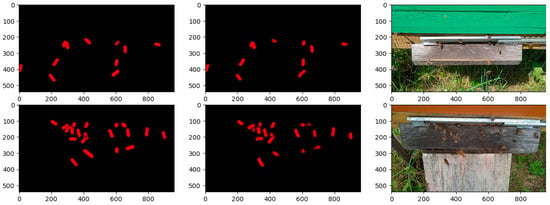

Figure 6 presents the predicted confidence maps of the bee heads generated by OpenBeePose for two example images, to enable more detailed observation of what the network is learning. These images show that the model maintains its robustness even in images with many bees. The heatmaps in the middle should closely match the one on the left, which is observed in this case. It is also noteworthy that there are almost no mispredictions using this method. Figure 7 shows a similar visualization to Figure 6, but for the PAFs. The results show a good correlation between the predicted and ground-truth PAFs for OpenBeePose, with almost no mispredictions.

Figure 6.

Sample confidence maps for the head joints of bees in two sample images. (Left column): Ground-truth confidence maps. (Middle column): Confidence maps predicted by OpenBeePose. (Right column): Corresponding images of the bee dataset.

Figure 7.

Part affinity fields (PAFs) for two sample images of the bee dataset. (Left column): Ground-truth PAFs. (Middle column): PAFs predicted by OpenBeePose. (Right column): Corresponding images of the bee dataset.

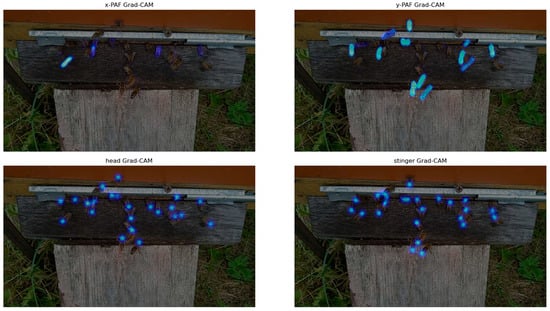

To improve the interpretability, the Grad-CAM [38] visualization method was also applied. This method identifies the most influential regions in images, making it easier to evaluate the model’s performance. As shown in Figure 8, the proposed model focuses primarily on areas containing bees, ensuring that irrelevant parts of the images do not influence its predictions.

Figure 8.

Grad-CAM output highlighting the most influential regions of each image in the prediction process of OpenBeePose. (Upper row): PAF predictions. (Lower row): Head and stinger confidence maps.

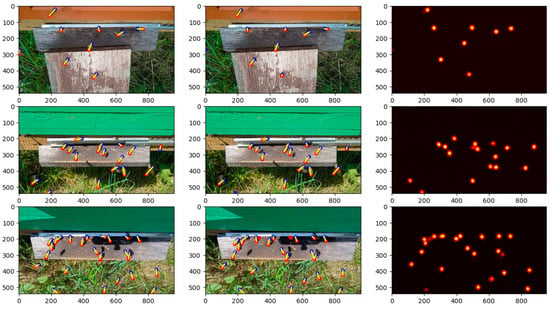

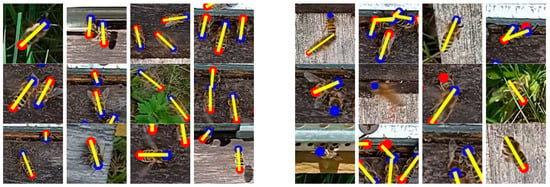

The x-PAF (x-component of PAF) and y-PAF (y-component of PAF) maps highlight the regions that contribute most to the predicted PAFs. Notably, the model focuses more on the y-component, probably because most bees are oriented vertically, making the x-component less significant. Additionally, the head and stinger diagrams illustrate that the model selectively concentrates on the keypoints required for generating the confidence maps, effectively filtering out redundant data. Figure 9 shows the OpenBeePose predictions on the test data. Blue dots represent heads and red dots represent stingers. This demonstrates that the model can handle cases where parts of the body are occluded.

Figure 9.

Results of OpenBeePose for some images of the bee dataset. Blue: Head keypoint. Red: Stinger keypoint. Yellow: Head–stinger segment. (Left column): Ground-truth skeletons of bees. (Middle column): Skeletons predicted by OpenBeePose. (Right column): Head confidence maps predicted by OpenBeePose.

On the other hand, one of the main advantages of OpenBeePose is its excellent inference time, which makes it very suitable for real-time tasks. It achieved an inference time of 17.6 ms for 540 × 960 images and 8.17 ms for 384 × 640 images, on the high-end computer. The execution times of the different models will be presented and compared in more detail in the following subsections.

3.2. Pose Estimation Results for YOLO11-Pose

In addition to the YOLO11-Pose model described in Section 2, other previous versions of YOLO were used and compared in the experiments: YOLOv8-n (nano), YOLOv8-m (medium), YOLO11-n (nano), YOLO11-m (medium), and YOLO11-l (large). The same partition of the dataset used for OpenBeePose was applied. Training on YOLO was performed for 100 epochs, at which point convergence was achieved, and both the loss and mAP remained stable thereafter.

The results obtained for the metrics in the bounding box detection of the bees for these five models are presented in Table 2. Both the v11 and v8 models performed similarly, except in terms of the mAP@50–95, where the medium model exhibited a 3% improvement. Additionally, YOLO11-n shows a noticeable increase in mAP@50–95 compared to YOLOv8-n, indicating more robust performance for the smaller models.

Table 2.

Comparison of bounding box detection metrics of YOLO11 and YOLOv8 on the bee dataset for different model sizes. l: large. m: medium. n: nano. The resolution of the images used for each model is shown in parentheses.

As can be seen, YOLO11 shows slightly better performance than YOLOv8 for bounding box predictions. Furthermore, enhanced computational efficiency has been achieved for YOLO11-m, attaining an average inference time of 31.0 ms for 1080 × 1920 images on the high-end server. It is also noticeable that the nano version has almost the same performance as the medium and large versions. YOLO11 achieved mAP@50 values of 98.90, 99.20, and 99.20% for nano, medium, and large, respectively. This shows that the task does not require a large pose estimation model, as the variations in the bees’ poses are not particularly large, except for the angles of the bees and the occlusions. YOLO11 showed a large increase in mAP@50–95 for the nano version, reaching almost 80%.

3.3. Comparison of OpenBeePose, OpenPose, and YOLO

After presenting the results obtained by each method separately, this section compares their effectiveness. Table 3 summarizes the seven evaluation metrics for OpenBeePose, the original version of OpenPose, and the five variants of YOLO studied.

Table 3.

Comparison of the performance evaluation metrics achieved by OpenBeePose and the different versions of OpenPose and YOLO on the bee dataset.

While OpenBeePose performed slightly worse in precision than the rest of the methods, it achieved better recall than the YOLO models, indicating that it is more robust to mispredictions. This fact results in OpenBeePose achieving the highest mAP@50 score of 99.59%. The most significant advantage of OpenPose over YOLO is in the PCP@0.3, which measures the accuracy of limb predictions. The original OpenPose achieves 83%, outperforming all YOLO models by around 10–15%, and OpenBeePose is at an intermediate position between them. In addition, regarding the PCK@0.5, OpenBeePose performed about 1.5% better than the best YOLO model and slightly better than OpenPose, further demonstrating its superiority in keypoint localization. In general, YOLO11 models improve the results of the previous version, YOLOv8. Moreover, the precision of YOLO11 models is clearly related to the size of the model, achieving the best results for the large model and the worst results for the nano model.

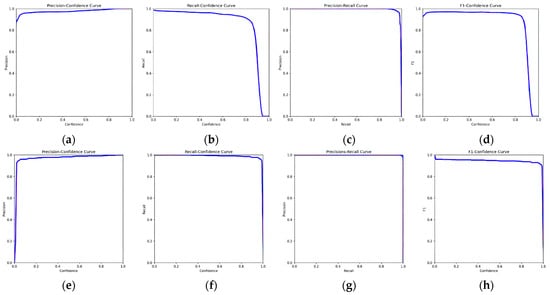

Figure 10 presents the usual precision–confidence, recall–confidence, precision–recall, and F1–confidence curves for the YOLO11-m and OpenBeePose models. This figure shows that the precision curves for both models are almost identical and always remain high. However, OpenBeePose exhibits a more stable curve with a smoother decline at higher confidence levels. In contrast, YOLO11’s recall drops off faster as the confidence increases, meaning that OpenBeePose is better at detecting objects at higher confidence levels. When comparing the precision–recall curves, OpenBeePose demonstrates a more gradual trade-off, suggesting that it generalizes better in ambiguous scenarios. Furthermore, although YOLO11’s F1-score is high overall, it declines sharply at higher confidence levels, while OpenBeePose shows a more consistent balance between precision and recall. This stability contributes to its overall robustness. Therefore, this figure clearly shows the superiority of OpenBeePose over YOLO.

Figure 10.

Performance curves of YOLO11-m and OpenBeePose models for the bee dataset. (a–d) Results for YOLO11-m. (e–h) Results for OpenBeePose. (a,e) Precision–confidence. (b,f) Recall–confidence. (c,g) Precision–recall. (d,h) F1–confidence.

Another interesting aspect to analyze is how the image resolution affects model accuracy. In general, lower-resolution images are expected to produce worse results. However, larger images require more inference time, so it is necessary to find a balance between the image resolution and inference time. Table 4 shows a comparison of the accuracy metrics for the OpenBeePose, OpenPose, and YOLO11-l models, using three resolutions: 1080 × 1920, 540 × 960, and 384 × 640 pixels.

Table 4.

Comparison of the performance evaluation metrics achieved by OpenBeePose, OpenPose, and YOLOv11-l on the bee dataset for different image resolutions.

These results reveal a disparity in outcomes, indicating that the assumption that higher-resolution images necessarily yield greater accuracy does not always hold. Nevertheless, it can be observed that, in general, reducing the resolution from 1080 × 1920 to 540 × 960 pixels does not lead to a significant decrease in accuracy, particularly for the OpenBeePose model. This finding demonstrates that, within the camera configuration employed in the dataset, the intermediate resolution of 540 × 960 pixels provides sufficient detail for the reliable estimation of bee poses.

Concerning computational efficiency for different image resolutions, the comparative results obtained by the models are shown in Table 5, using the high-performance computer with an RTX 4090 GPU.

Table 5.

Comparison of inference times and frame rates between OpenBeePose, OpenPose, and YOLO, using different versions and a high-performance computer with an RTX 4090 GPU.

In this configuration, almost all models were capable of producing results in less than 0.1 s per image. In addition, with the exception of the maximum resolution of the images (1080 × 1920 pixels), all methods worked in real time, above 30 FPS. It is interesting to recall that the excellent accuracy results achieved by OpenBeePose and YOLO11-l, presented in Table 3, were obtained at a resolution of 540 × 960 pixels. Therefore, this size allows for a mAP@50 that is higher than 99% with speeds of 57 FPS for OpenBeePose and 42 FPS for YOLO11-l. In general, OpenBeePose is faster than the YOLO models; for example, it was able to process images at up to 122 FPS for 384 × 640 images, while YOLOv8-n only reached 67 FPS. OpenBeePose is also significantly faster than the original OpenPose, with an average reduction in inference time of between 32% and 39%.

However, these results may vary in other configurations, especially in the absence of a GPU. Table 6 shows the inference time results obtained using the low-end computer without GPU usage presented in Section 2.6. The weights of the network models were the same as in the previous experiment. In this case, the models based on YOLOv8 were discarded because they were less accurate than YOLO11.

Table 6.

Comparison of inference times between OpenBeePose, OpenPose, and different YOLO versions, using a low-end computer without a GPU.

Under this configuration, the results prove the superiority of the YOLO11-based methods with respect to computational efficiency. In general, all inference times on this computer were longer, so they were measured in seconds rather than milliseconds. OpenBeePose was about twice as fast as OpenPose. Nonetheless, the inference time for the halved images was approximately 1.5 s per image. In contrast, models based on YOLO11 are much faster, although without reaching speeds that are close to real time. As might be expected, the lighter (nano and medium) models are faster than the heavier (large) models. Thus, the YOLO11-m and YOLO11-n models could be a good compromise when high speed is required with low-cost devices, with the former reaching a speed of about 2 FPS and the latter close to 10 FPS.

4. Discussion

After presenting the experimental results, this section will discuss and analyze the findings of this study. First, a detailed analysis is performed on the main difficulties existing in cases of high occlusion of bees and how the proposed models work under these conditions. Then, the results obtained are compared with previous works in the literature. Finally, the main findings are summarized.

4.1. Insight into Bee Pose Estimation Under Heavy Occlusion

In general, it has been observed that all of the studied methods are capable of accurately detecting bees in isolation, with accuracy close to 100%. The main challenge remains the detection of bees in crowded situations, where overlapping and occlusion problems may occur. For this reason, the results obtained on some specific images are discussed in more detail in this subsection. Figure 11 shows some samples of correct detections and the difficulties encountered by OpenBeePose in overlapping cases.

Figure 11.

Some correct and incorrect sample results of OpenBeePose on images of the bee dataset using a 576 × 1024 resolution. Blue: Head keypoint. Red: Stinger keypoint. Yellow: Head–stinger segment. (Left): Correct detections and pose estimations. (Right): Missing detections and incorrect keypoint estimations.

Problems in detecting the bee pose can be mainly due to two factors. Firstly, overlapping or low resolutions of images may cause some bee parts (head or stinger) to not be correctly detected with the VGG-19 features. In these situations, the PAF branch will be unable to make correct associations, resulting in false negatives, i.e., bees that are not detected. This can be seen in the head and stinger confidence maps, which show inaccurate or non-existent locations of these parts, as shown in Figure 6.

The second problem is due to overlapping or the proximity of the bees, which results in the incorrect association of parts with the Hungarian algorithm. Several examples of these incorrect associations can be seen in Figure 11. In particular, it often happens that the same part is associated with two different bees, and some parts can be detached, as can also be seen. Consequently, although the PCK and OKS measures are high (since they measure the keypoints in isolation), the PCP measure decreases because of the failure to obtain a correct association among the parts.

Figure 12 shows some detailed results of YOLO11-l on images with high bee overlap, including correct and incorrect pose estimations. In this case, the images were processed at the maximum resolution of 1080 × 1920 pixels.

Figure 12.

Some correct and incorrect sample results of YOLO11-l on images of the bee dataset using a 1080 × 1920 resolution. Red: Head keypoint. Yellow: Stinger keypoint. (Left): Correct detections and pose estimations; Blue box: bee bounding box. (Right): Missing detections and incorrect keypoint estimations; Green box: correctly detected bees; Red box: missing detections; Blue box: correctly detected bees but with incorrect keypoints.

Overall, the accuracy of YOLO11 in these images of high bee density is excellent. The model was able to detect most of the bees and localize correctly the head and the stinger, even if there were overlaps and partial occlusion. In some cases, occlusion occurs when the bees are entering or leaving the hive; even so, the model was able to recognize them with high likelihood values of around 0.83. This accuracy degrades progressively as the size of the images decreases. It is also interesting to note that this method could detect some bees that were blurred, having been captured in flight. However, some missed bees (false negatives) and, more rarely, some incorrect detections (false positives) can also be seen in areas with many bees. Consequently, although this method does not have problems due to the incorrect association of parts, as is the case with OpenBeePose and OpenPose, other situations may occur that lead to errors in detection.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Works

As mentioned in the Introduction, the four studies that are most closely related to our bee detection and pose estimation problems are as follows. The most related one is [8]. Although this is a recent work, pose estimation was performed using only YOLOv8-Pose, achieving the best results with the medium model; the experiments were performed with sizes of 384 × 640 and 576 × 1024 pixels. This paper introduced the bee dataset that we have used. However, since the specific train/validation/test partitions are not provided in the dataset, it cannot be assumed that the same images were used to train and test the models.

The other three studies used their specific image datasets for bee pose estimation, so it is necessary to place this comparison in context. They are all based on deep learning and, more specifically, convolutional neural networks. Smith et al. [9] used the SLEAP method, based on a U-Net network, to track the behavior of bumble bee colonies; unlike the present work, the images were taken inside the hive, presenting more crowded bee scenes. Bozek et al. [10] introduced their own U-Net network in order to detect and estimate the orientation of bees inside hives. Meanwhile, Rodriguez et al. [11] studied the pose estimation of bees at the entrances of the hives, applying a backbone network based on VGG-19 followed by part affinity fields (PAF). Table 7 presents a comparative analysis of the results reported in these papers.

Table 7.

Comparison of the proposed models for bee pose estimation and other previous works.

These results show that pose estimation based on YOLO11 is more accurate than that based on YOLOv8. However, OpenBeePose is the most accurate method of all, achieving a mAP@50 of 99.59%. Additionally, the two approaches compared in this paper require lower-resolution images, implying a significant reduction in computational overhead. This would allow its execution in real time in the high-end configuration, with a speed of 57 FPS in the OpenBeePose version with a 540 × 960 resolution or up to 2 FPS in the low-end configuration with YOLO11-l, as presented in Table 5. Although specialized systems based on U-Net are unable to achieve state-of-the-art results, we must remember that these works used their own particular datasets. For example, Rodriguez et al. [11] used a blue background to facilitate pose detection, and their images of bees are more detailed than those available from [15]. Another factor that substantially affects the precision measurements is how the pose detection is carried out, since, in many of these previous works, the legs and antennae are also located and not only the head and stinger. In our case, it was deemed sufficient to detect the head and stinger for many of the problems of interest in smart beekeeping, such as counting bees, tracking hive entry and exit, and monitoring interactions between individuals.

4.3. Summary of the Main Findings and Future Improvements

By integrating advanced technologies to track and analyze the movement and positions of bees, pose estimation provides critical and detailed insights, empowering beekeepers to make informed and efficient decisions. This capability not only optimizes beekeeping practices but also contributes to ecosystem conservation and the mitigation of bee population declines. In this context, the objective of the present work was to propose a novel method that guarantees high accuracy while significantly reducing processing times, making it suitable for real-time applications that demand rapid and precise decision-making. The main findings of this research can be summarized as follows:

- The bee dataset was trained using the proposed method, OpenBeePose, as well as OpenPose and YOLO to facilitate a comprehensive comparison between the latest versions of these models. This comparison focused on evaluating the suitability of each method for high-frames-per-second (FPS) tasks. OpenBeePose proved to be particularly effective for high-FPS real-time tasks, reaching an inference time of 17.6 ms for 540 × 960 images and 8.17 ms for 384 × 640 images. In contrast, YOLOv8-n required approximately 15.0 ms for images of size 384 × 640. These results indicate that OpenBeePose offers a significant advantage in terms of processing speed, making it an attractive option for applications where a real-time response is crucial. This faster processing capability enables the more effective monitoring and analysis of bee behavior, which can be fundamental for rapid decision-making in hive management. It should be noted, however, that the process was run on a high-performance computing server equipped with a high-end GPU (RTX 4090). On the low-end computer without a GPU, these results were reversed, and YOLO11 was found to be much more efficient; nevertheless, OpenBeePose remained about twice as fast as OpenPose. Using a medium resolution of 540 × 960 pixels, YOLO11-l was able to process two images per second; with the lighter version, YOLO11-n, a speed close to 10 FPS was achieved. Although this is far from real time, it is a fast enough processing speed to be able to analyze individual bee behavior and interactions.

- OpenBeePose achieved a mAP@50 of over 99.5% and a mAP@50–95 of over 98.3%. These metrics indicate the high accuracy of OpenBeePose in detecting bee keypoints. A mAP@50 above 99% means that, in most cases, the detected keypoints have an object keypoint similarity (OKS) score of at least 0.50 compared to the ground truth. The mAP@50–95, which averages the mAP over OKS thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95, suggests that the proposed method maintains high accuracy even with stricter localization requirements.

- The most significant advantage of OpenPose over the other models lies in the PCP@0.3, which measures the accuracy of limb predictions. OpenPose achieved 83%, outperforming YOLO methods by approximately 10–15%; OpenBeePose was in an intermediate position between them, with a PCP@0.3 of over 78%. Additionally, in terms of the PCK@0.5, OpenBeePose and OpenPose performed approximately 1.5% better than YOLO, further demonstrating their superiority in keypoint localization. In any case, it has been observed that all methods present difficulties in dense hive environments, where bees are often close and partially occluded. The part association component of OpenPose and OpenBeePose tends to produce incorrect associations of bee parts, while YOLO11 is generally more robust in these situations.

- OpenBeePose is better at detecting objects at higher confidence thresholds. When comparing the precision–recall curves, it showed a more gradual trade-off, suggesting that it generalizes better in ambiguous scenarios. Furthermore, while YOLO11’s F1-score is high overall, it declines sharply at higher confidence levels. The proposed method, however, showed a more consistent balance between precision and recall. This stability contributes to its overall robustness.

- As we have observed in the description of the previous works, there is a disparity in the bee datasets used for experimentation, which vary considerably in size, image resolution, annotation types, and formats, reflecting diverse research purposes like detection, segmentation, and pose estimation. The existing datasets range from those with two keypoints per bee at a resolution of 1080 × 1920 to those with five key body points, and they are labeled with different formats, such as YOLO, COCO, and XML. To ensure fair comparisons and accelerate progress in this field, it is essential to promote the use of standardized public datasets, which allow for objective evaluation and facilitate the development of robust, generalizable methods.

- Concerning possible future improvements, two promising directions are enhancing the system’s robustness to bee occlusions and extending pose estimation to a larger number of keypoints. Regarding occlusion, our current approach has already demonstrated robustness against partial occlusions, as bees are often partially hidden by other individuals or hive structures. However, in cases of severe occlusion, where most of the body is not visible, it is difficult to propose effective solutions without additional sensing modalities. Future work could explore complementary strategies such as multi-view camera setups or temporal information from video sequences, although these were beyond the scope of the present study. Concerning the extension to additional keypoints, the underlying OpenPose framework is inherently flexible and supports an arbitrary number of keypoints. Extending OpenBeePose to more keypoints would therefore not pose a methodological challenge. In our experiments, only two keypoints (head and stinger) were annotated because the available dataset contained labels for these features exclusively. With a more richly annotated dataset, the model could be readily adapted to estimate additional keypoints, enabling more detailed behavioral analyses.

5. Conclusions

Pose estimation in beekeeping is an emerging field that uses computer vision and machine learning to monitor and analyze bee behavior, with the potential to transform hive management and improve bee health. It allows for non-intrusive monitoring and the detailed analysis of bee activity, offering opportunities for the early detection of health issues and the optimization of beekeeping practices. Accurately tracking the positions and orientations of bees can aid in the conservation of these pollinators. For this purpose, in this paper, a new method, called OpenBeePose, has been presented, based on the generic OpenPose model with important adaptations and improvements in image preprocessing, feature extraction, and the multi-stage CNN networks used to obtain confidence maps and part affinity fields.

In the experiments, OpenBeePose, OpenPose, and YOLO11-Pose demonstrated high accuracy in identifying keypoints on bees. These methods improve upon previous work in the field, achieving accuracies above 99%. However, OpenBeePose stands out due to its speed of inference and accuracy in predicting body parts. Its low processing time on GPU devices makes it suitable for real-time applications where the efficient processing of video data is crucial. Its ability to predict body parts accurately enhances its capacity to capture subtle details in bee posture, which is important in analyzing specific behaviors. However, for use with low-end devices without a GPU, YOLO11 is the superior option, with a faster inference speed than OpenBeePose and OpenPose.

A significant challenge in this field is the lack of standardization of datasets, which vary in size, resolution, annotation format, and purpose. This makes it difficult to compare methods objectively and generalize the results. Adopting standardized, public datasets is therefore crucial to enable fairer and more rigorous algorithm evaluations, facilitate reproducibility, and foster the development of more robust and adaptable methods.

Other future research directions include exploring hybrid architectures that combine the strengths of OpenBeePose and YOLO11. For example, YOLO11 could be used for rapid bee detection, while the OpenBeePose architecture could be used for precise pose estimation in the detected regions. Another area for investigation is applying pose estimation techniques to analyze bee behavior in various contexts, such as foraging, social interaction, and responses to environmental factors like pesticides and thermal stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.S., A.N., R.P., G.G.-M., R.F.-B. and M.H.R. Methodology: S.S., A.N. and R.P. Software: S.S. and A.N. Investigation: S.S., A.N., R.P., G.G.-M., R.F.-B. and M.H.R. Visualization: A.N. and R.P. Supervision: S.S., R.P., G.G.-M., R.F.-B. and M.H.R. Funding acquisition: G.G.-M. Writing—original draft: S.S., A.N., R.P. and M.H.R. Writing—review and editing: G.G.-M. and R.F.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by project 22130/PI/22 financed by the Regional Program for the Promotion of Scientific and Technical Research of Excellence (Action Plan 2022) of the Fundación Séneca-Agencia de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Región de Murcia, Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this article was created by Sledevič, T. and Matuzevičius, D. and was presented in the article [15], with the title “Labeled dataset for bee detection and direction estimation on beehive landing boards”. It is available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/8gb9r2yhfc/6 (published: 28 August 2024, Version 6, DOI:10.17632/8gb9r2yhfc.6 (accessed on 25 December 2025)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| FPS | Frames per second (s−1) |

| mAP | Mean average precision (%) |

| MPJPE | Mean per-joint position error (%) |

| PAF | Part affinity field |

| PCK | Percentage of correct keypoints (%) |

| PCP | Percentage of correct parts (%) |

| OKS | Object keypoint similarity (%) |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once (deep learning model) |

References

- Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Zou, B. Estimation of 3D Human Pose Using Prior Knowledge. J. Electron. Imaging 2021, 30, 40502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Ren, Z.; Wang, J. Guest Editorial: Special Issue on Human Pose Estimation and Its Applications. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2023, 34, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapczyński, M.; Werner, P.; Handrich, S.; Al-Hamadi, A. A Baseline for Cross-Database 3d Human Pose Estimation. Sensors 2021, 21, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Sun, K.; Fan, H.; He, Z. Real-Time Cattle Pose Estimation Based on Improved RTMPose. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahnakian, F.; Farahnakian, F.; Björkman, S.; Bloch, V.; Pastell, M.; Heikkonen, J. Pose Estimation of Sow and Piglets during Free Farrowing Using Deep Learning. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gong, C.; Wang, D.; Ye, M.; Jia, Y. Study of Pose Estimation Based on Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of Cow Skeleton. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zheng, H.; Yang, J.; Deng, H.; Zhang, T. Study on Poultry Pose Estimation Based on Multi-Parts Detection. Animals 2022, 12, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sledevič, T.; Serackis, A.; Matuzevičius, D.; Plonis, D.; Andriukaitis, D. Keypoint-Based Bee Orientation Estimation and Ramp Detection at the Hive Entrance for Bee Behavior Identification System. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.Y.; Easton-Calabria, A.; Zhang, T.; Zmyslony, S.; Thuma, J.; Cronin, K.; Pasadyn, C.L.; de Bivort, B.L.; Crall, J.D. Long-Term Tracking and Quantification of Individual Behavior in Bumble Bee Colonies. Artif. Life Robot. 2022, 27, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozek, K.; Hebert, L.; Mikheyev, A.S.; Stephens, G.J. Towards Dense Object Tracking in a 2D Honeybee Hive. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4185–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, I.F.; Chan, J.; Alvarez Rios, M.; Branson, K.; Agosto-Rivera, J.L.; Giray, T.; Mégret, R. Automated Video Monitoring of Unmarked and Marked Honey Bees at the Hive Entrance. Front. Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 769338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Hidalgo, G.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.E.; Sheikh, Y. OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation Using Part Affinity Fields. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathis, M.W.; Mathis, A. Deep Learning Tools for the Measurement of Animal Behavior in Neuroscience. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padubidri, C.; Kamilaris, A.; Charalambous, A.; Lanitis, A.; Constantinides, M. The Be-Hive Project—Counting Bee Traffic Based on Deep Learning and Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the SAI Intelligent Systems Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7–8 September 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Sledevič, T.; Matuzevičius, D. Labeled Dataset for Bee Detection and Direction Estimation on Entrance to Beehive. Data Brief 2024, 52, 110060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.S.; Xie, S.; Tai, Y.W.; Lu, C. RMPE: Regional Multi-Person Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2017, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2353–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkioxari, G.; Hariharan, B.; Girshick, R.; Malik, J. Using K-Poselets for Detecting People and Localizing Their Keypoints. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 3582–3589. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2017, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, U.; Gall, J. Multi-Person Pose Estimation with Local Joint-to-Person Associations. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I; Springer; Cham, Switzerland, Volume 9914, pp. 627–642. [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, G.; Zhu, T.; Kanazawa, N.; Toshev, A.; Tompson, J.; Bregler, C.; Murphy, K. Towards Accurate Multi-Person Pose Estimation in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3711–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, A.; Huang, Z.; Deng, J. Associative Embedding: End-to-End Learning for Joint Detection and Grouping. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 2274–2284. [Google Scholar]

- Papandreou, G.; Zhu, T.; Chen, L.-C.; Gidaris, S.; Tompson, J.; Murphy, K. Personlab: Person Pose Estimation and Instance Segmentation with a Bottom-up, Part-Based, Geometric Embedding Model. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiss, S.; Bertoni, L.; Alahi, A. PifPaf: Composite Fields for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 11969–11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.E.; Ramakrishna, V.; Kanade, T.; Sheikh, Y. Convolutional Pose Machines. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2016, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 4724–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.E.; Sheikh, Y. Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation Using Part Affinity Fields. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, G.; Sun, J. Cascaded Pyramid Network for Multi-Person Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7103–7112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Volume 8693, pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, M.R.; Perona, P. Benchmarking and Error Diagnosis in Multi-Instance Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2017, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriluka, M.; Pishchulin, L.; Gehler, P.; Schiele, B. 2D Human Pose Estimation: New Benchmark and State of the Art Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2014, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 3686–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, A.; Yang, K.; Deng, J. Stacked Hourglass Networks for Human Pose Estimation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Eichner, M.; Marin-Jimenez, M.; Zisserman, A.; Ferrari, V. 2D Articulated Human Pose Estimation and Retrieval in (Almost) Unconstrained Still Images. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2012, 99, 190–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourdarbani, R.; Sabzi, S.; Kalantari, D.; Paliwal, J.; Benmouna, B.; García-Mateos, G.; Molina-Martínez, J.M. Estimation of Different Ripening Stages of Fuji Apples Using Image Processing and Spectroscopy Based on the Majority Voting Method. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.