Featured Application

The suggested system enables automated, verifiable BIM through the integration of blockchain, smart contracts, and semantic oracles. It facilitates secure BIM versioning, automated design verification, and smart contract-based payment disbursement, thereby enhancing transparency and reliability in construction project management.

Abstract

The integration of Building Information Modelling (BIM), blockchain technology, and smart contracts presents a significant opportunity to fundamentally reevaluate the administration of information and contracts in construction projects. This article introduces a distributed system that amalgamates BIM models, decentralized storage via IPFS, semantic oracles, and smart contracts to automate essential procedures such as versioning, design verification, and payment issuance contingent upon execution milestones. This proof of concept, built on a Proof-of-Authority blockchain using actual IFC models, demonstrates the technical viability of the method and evaluates its performance, constraints, and operational implications. The applications of SAL automation and design review demonstrate that integrating off-chain verification with on-chain documentation can reduce uncertainty, enhance accountability, and enable hitherto unattainable forms of contract automation. The suggested framework acknowledges the need for improved information standards and Oracle governance, demonstrating that integrating BIM and distributed technologies can significantly transform the digitalisation of the construction sector.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is experiencing digital change, which, although progressing swiftly, remains obstructed by structural inefficiencies and persistent information fragmentation. The implementation of BIM has established a novel approach to project data management, consolidating geometric, semantic, and performance information into a single digital model accessible to diverse stakeholders in the construction process [1,2,3]. The increasing importance of BIM is further substantiated by the Italian regulatory framework, which mandates its use in public procurement starting in 2025, for new construction and intervention on existing buildings with a value exceeding 2 million euros, laying the groundwork for broader digitalization across the entire supply chain [4,5].

Concurrently, blockchain and innovative contract technologies are gaining prominence, offering automation, traceability, and verifiability procedures in sectors historically marked by a deficiency of transparency. Smart contracts, defined as self-executing programs inscribed on the blockchain, have been proposed as a substitute for conventional agreements due to their resilience against manipulation, potential to reduce interpretative ambiguity, and capacity to autonomously activate operational clauses encoded in software [6,7].

In the construction domain, the following attributes are notably significant: payment delays, challenges in ascertaining the genuine advancement of the work, and persistent conflicts among the client, contractor, and suppliers are among the primary factors that substantially influence the overall operational risk of the project, as evidenced by recent research focused on cash flow management and the automation of payment processes utilizing blockchain and 5D BIM models [8,9,10].

Nonetheless, the amalgamation of BIM, blockchain, and smart contracts remains unrefined, with several solutions articulated in the literature still in an initial experimental stage. Decentralized systems exist for managing model versions, utilizing distributed architectures and multi-branch structures to guarantee the traceability and immutability of BIM data, alongside conceptual frameworks that investigate the application of smart contracts to automate verification, validation, and design review processes in a BIM-centric environment [11,12,13]. Nonetheless, a deficiency persists in integrated, fully functional models that can unify these contributions into a cohesive architecture suitable for real-world projects and compliant with existing regulatory and procedural constraints [14,15,16].

This is accompanied by a set of implicit assumptions that frequently arise in scientific discourse. The adoption of blockchain is commonly seen as an inherently advantageous alternative, almost as if decentralisation were inherently better than any centralised method currently in use [17,18,19]. A more detailed investigation indicates that numerous inefficiencies within the sector stem from organisational, legal and contractual issues that can only be resolved through the implementation of new technologies [20,21,22]. Moreover, a substantial portion of the control, verification, and coordination processes relies on qualitative, relational, and contextual evaluations that are not readily convertible into formal regulations or computable criteria; this constrains the capacity to delegate contract execution to an entirely autonomous smart contract fully [23,24,25].

An additional crucial aspect, little discussed in the literature and absent from everyday practice, is the scalability of the distributed infrastructures used for information flows in the AEC sector. While blockchain provides transparency and immutability that centralized architectures struggle to replicate, its capacity to handle high transaction volumes is still constrained by the complexity and frequency of activities characteristic of a Common Data Environment [26,27,28,29]. The incessant generation of models, modifications, attachments and verifications puts considerable pressure on the network, particularly if each update requires association with a hash, connection to an oracle and validation through a consensus process [30,31,32]. The internal latency of distributed systems and their proportionally low throughput could be a problem if appropriate techniques, such as hybrid architectures, side chains, or off-chain aggregation layers, are not adopted. Incorporating this issue into the introductory framework is crucial, as it clarifies that the aim is not to migrate the entire information ecosystem to the blockchain, but to identify which components of the process genuinely benefit from distributed ledger technology and how this can be implemented without undermining the overall efficiency of the digital flow [33,34,35].

One of the objectives of this study is to clarify the circumstances in which the integration of BIM, blockchain and smart contracts can offer real added value, distinguishing between actual potential and implausible aspirations [36,37]. Therefore, the objective is to develop a valid and up-to-date methodological proposal to assess the impact of these technologies on contractual and information processes in the construction sector, suggesting a coherent structure that promotes automation, traceability and verifiability of operations. This work’s primary scientific breakthrough is the cohesive formalization of a distributed workflow that seamlessly and verifiably links data production in the BIM model, its off-chain semantic transformation, and on-chain contract execution [38,39,40]. While the literature presents discrete instances of blockchain versioning, payment automation, and distributed document management, none of these studies amalgamate the complete information and operational flow into a computable, reproducible framework [41,42,43,44]. The proposed model addresses fragmentation through an end-to-end architecture that integrates multi-branch versioning, distributed storage, semantic oracles, and executable smart contracts, demonstrating the technical interoperability of these components and their ability to support essential processes such as model validation, design rule verification, and automatic milestone settlement. This integration, along with the delineation of on-chain data structures and operational algorithms detailed in the appendix, represents a significant advancement over current methodologies, providing a thorough and adaptable operational framework for the digital management of construction projects. The proposed framework fits within the growing Industry 5.0 paradigm, which prioritizes human-centric, resilient, and interoperable cyber–physical systems. The architecture facilitates human-in-the-loop decision-making by integrating computational verification with institutional and professional governance, rather than seeking complete automation. In this context, blockchain is utilized not as a singular data repository, but as an interoperable trust layer that ensures integrity, traceability, and accountability across distributed entities. Semantic oracles serve as modular data-validation layers that connect physical and digital realms, whereas smart contracts codify procedural logic without supplanting expert judgment. This positioning underscores the framework’s applicability outside the construction sector, indicating its significance for other Industry 5.0 contexts defined by collaborative workflows, distributed accountability, and verified data-driven processes. The research is based on three main questions:

RQ1: To what degree may blockchain and smart contracts mitigate inefficiencies associated with payments, verifications, and liability management in BIM-based processes?

RQ2: What architectural models and information mechanisms provide technically coherent integration among BIM models, distributed ledgers, and smart contracts, therefore addressing the limits of existing experiments?

RQ3: What are the constraints, facilitating conditions, and operational, organizational, and regulatory ramifications that affect the implementation of BIM–blockchain–innovative contract solutions in the construction industry?

The article addresses these questions through a systematic analysis of current knowledge, a critical synthesis of existing solutions, and the proposal of an integrated framework to effectively enhance synergies among the three technologies, thereby establishing a credible pathway for the digitalization of the AEC sector. This work contributes by establishing an integrated framework that addresses the fragmented approach prevalent in present research, which typically emphasizes specific blockchain applications or standalone innovative contract experiments devoid of any substantial connection to the BIM information cycle [45,46,47]. Current research has demonstrated the viability of recording model hashes, monitoring versions, and automating specific administrative tasks; however, none have comprehensively addressed the need for an infrastructure that integrates data generation within the IFC model, off-chain semantic verification, and on-chain contract execution within an expanded Common Data Environment [14,48,49]. The proposed framework presents a comprehensive architecture that incorporates multi-branch versioning, distributed storage, computational oracles, and executable smart contracts, demonstrating the technical compatibility of these components and their ability to facilitate essential processes such as automated milestone settlement and design review. This integration, along with experimental validation on actual models and performance analysis of the distributed workflow, represents a scientific development beyond the current state of the art and provides an operational paradigm that can be duplicated in real-world scenarios.

2. Related Work

The digitization of the construction industry has been solidified in recent years by the proliferation of BIM, which has evolved from a basic three-dimensional modeling tool into a sophisticated, collaborative information framework. The capacity of BIM to integrate geometric, temporal, economic, and performance data has facilitated enhanced collaboration among diverse stakeholders in the construction process, while underscoring the need for reliable systems to manage versions, information responsibilities, and interdependencies among disciplines, as evidenced by numerous studies on the topic [5].

The advancement of blockchain technologies has established a novel framework for distributed data management, characterized by decentralization, immutability, and consensus processes to ensure ledger integrity. Initial research examining the ramifications of blockchain in contractual frameworks emphasized that its resistance to manipulation, capacity to eliminate ambiguity, and potential to automate operational clauses via smart contracts could serve as a substitute for conventional legal agreements, which frequently face varied interpretations and procedural intricacies [25,50]. This research laid the groundwork for investigating the use of smart contracts in complex, fragmented industries such as construction [51,52].

Research activities initiated in the AEC sector have focused on the use of blockchain technology for monitoring, authenticating and validating critical processes, including skills transfers, authorisations and document exchanges. Multiple studies have emphasized that integration with BIM enhances the transparency and trustworthiness of information, particularly in collaborative procedures where revision management is crucial. Recent studies have suggested decentralized solutions for model versioning that leverage blockchain and distributed file systems. The implementation of multi-branch architectures has demonstrated the ability to concurrently document model development, associated design challenges, and interdisciplinary interrelations, thereby addressing numerous significant problems characteristic of centralized management systems [44,53,54].

A significant domain pertains to economic and contractual procedures. The literature indicates that delayed payments and challenges with timely, objective verification of work progress are primary sources of inefficiency and disagreement in projects. The integration of 5D BIM models with smart contracts is proposed to trigger automatic payments upon the occurrence of specific steps within the model, thus limiting liquidity checks and reducing the need for intermediaries. A critical framework has shown how such a system can produce permanent and verifiable records of financial transactions, thereby improving the financial stability of projects [55,56,57].

In addition to these research efforts, conceptual contributions have emerged, focusing on establishing interoperability models between BIM and blockchain, as well as on examining the use of smart contracts in design verification procedures. Specific research has suggested architectures that utilize distributed ledgers to automate checks, reviews, and validations, emphasizing that the ability to associate computable conditions with model objects can provide novel insights for automating design review procedures. Nonetheless, these methodologies have revealed certain structural constraints: numerous technical evaluations still require human judgment, are difficult to formalize, and are therefore only partially convertible into provisions executable by a smart contract. The research has identified issues related to interoperability, cybersecurity, and permission management, indicating that implementing distributed ledgers could provide solutions, albeit requiring novel governance frameworks and technological standards [8,58,59].

The current state of the art indicates a swiftly evolving, although still investigatory, scientific domain (in summary in Table 1). The ability of blockchain technology to improve the traceability, security and reliability of information and contractual processes has been widely demonstrated; at the same time, considerable methodological, regulatory and computational difficulties remain. The integration of BIM, blockchain and smart contracts is interesting, but requires a careful approach to identify conditions, constraints and potential expansions for effective use in the construction industry.

Table 1.

Summary of related work.

3. Application Background

Notwithstanding progress in digitalization and the increasing implementation of BIM, the construction sector is marked by structural challenges that profoundly impact the transparency, predictability, and efficiency of its processes. The main difficulties concern both the information aspect, in relation to the management and quality of data relating to the activity, and the contractual and economic aspect, where the absence of a reliable control system leads to delays, disagreements and price increases. An examination of the present circumstances indicates that these issues cannot be ascribed to a singular cause, but rather stem from an interplay of technical, organizational, and regulatory deficiencies that exacerbate one another [60].

A critical challenge pertains to information management, specifically the quality, consistency, and traceability of data in BIM-based collaborative workflows. The digital model was developed as a collective representation of the project; yet, in reality, accountability for information is frequently dispersed across designers, consultants, contractors, and suppliers. In many cases, each individual competitor works on incomplete or obsolete versions, with the risk of producing inconsistencies, overlaps and errors that multiply in subsequent stages. The issue of versions is particularly relevant: the implementation of centralised data sharing settings does not ensure complete oversight of the chronological sequence of changes, their responsibility or the integrity of the reference models. The literature shows that this weakness can lead to reduced traceability, conflicts over responsibility for changes and problems in reconstructing the decision-making process that led to the final configuration of the project.

The complexity of BIM requires continuous updating, validation, and adherence to criteria that vary depending on entities, projects, and disciplines. Without a robust system to guarantee the immutability of data and the provenance of information, trust in the model could be compromised. If data cannot be independently validated, it becomes difficult to use it as a basis for contractual, financial, or operational decisions. The lack of a reliable certification method is fundamentally responsible for numerous inefficiencies and disagreements, particularly during execution phases, where discrepancies in data can lead to conflicts over progress, unexpected changes, and delivery delays.

The economic-contractual aspect has analogous deficiencies. Compensation for public and commercial projects relies on incremental, often manual evaluations of completed work. These evaluations require time, involve numerous individuals, and are usually open to varying interpretations. The literature has emphasized that delayed payments can lead to cash flow instability, heightened financial risks, and strain on the client-contractor relationship. It is common for one party to challenge the legitimacy of the data used to authorize a payment, or for procedural delays to result in substantial discrepancies between actual progress and the official status of the job. This structural problem in the sector adversely affects the entire supply chain, thereby impacting the quality and timing of the project.

A further issue is the inherent characteristics of contracts used in the building industry, which are conventionally based on lengthy, intricate, and often ambiguous documents. The provisions delineating obligations, timetables, responsibilities, and punishments are usually articulated in a manner that lacks complete determinism, allowing significant scope for interpretation. Lexical, syntactic, and temporal ambiguities, extensively recorded in legal and technical literature, create variances in sentence interpretation and facilitate disagreements. In the most intricate circumstances, the outcome is not merely a deceleration of operations but also an escalation in expenses, a deterioration of mutual trust, and an exacerbation of collaborative fragmentation.

These issues underscore a prevalent challenge: the construction supply chain is hindered by the absence of an integrated management system that ensures transparency, consistency, and verifiability in information and decision-making processes. The presence of multiple players, each with distinct tasks, duties, and tools, complicates establishing a uniform, reliable, and unambiguous environment. Digitalization has enhanced certain facets; nonetheless, it has not addressed the fundamental challenge: ensuring that data, decisions, and responsibilities are monitored, verifiable, and disseminated without the risk of manipulation or loss of essential information.

The impetus to investigate the amalgamation of BIM, blockchain, and smart contracts is specifically in this pivotal domain. The research questions presented in the preceding chapter are addressed here: examining how these technologies can enhance transparency, reduce decision-making uncertainty, automate status and condition verification, and establish an information ecosystem in which trust, accountability, and consistency are ensured not by individual entities but by a collective, verifiable, and tamper-proof infrastructure. The subsequent chapter addresses these potentials by offering a framework to address the identified key challenges, converting the theoretical concepts derived from the literature into a cohesive operational model.

4. Proposed Framework

The integration of BIM, blockchain, and smart contracts offers an auspicious approach to addressing the structural challenges highlighted in the preceding chapter. Nevertheless, the solutions articulated in the literature are sometimes disjointed: many studies focus on versioning, others on payment administration, and others on design verification and review processes. No model exists that integrates these contributions into a cohesive system capable of functioning with a continuous stream of information aligned with the operational requirements of construction projects. This chapter presents a methodology to address this gap by delineating a logically cohesive architecture that facilitates synergistic collaboration among the three technologies.

The issue is not merely the overlay of technologies for redundancy, but rather the allocation of distinct roles to each, aligned with their respective capabilities. BIM offers a computational representation of the project and its features; blockchain provides the assurance that relevant updates, decisions, and transactions are unchangeable; smart contracts enforce the procedural logic that relates the informational states of the model to the contract or administration actions.

The initial element of the suggested architecture pertains to the administration of model data and its versions. Scientific contributions that have introduced multi-branch structures to concurrently represent the evolution of revisions, associated design issues, and interdisciplinary dependencies indicate a clear trend: blockchain is especially effective in ensuring that information appended to a register is verifiable, permanent, and linked to explicit accountability. Integration with distributed file storage systems, such as IPFS, helps manage the volume of BIM models, preventing the ledger from being burdened with excessive data. In this context, the blockchain comprises file hashes, digital signatures, and version metadata, whereas the actual content is stored in a decentralized repository accessible to authorized parties. This method establishes a verifiable sequence of modifications to the model, enabling precise identification of the individual responsible for each change, the timing of the alteration, and the version deemed legitimate for project reference.

The second pillar of the framework pertains to the automation of contractual operations. Smart contracts formalize operational conditions that link the status of the BIM model to the duties and activities stipulated in the agreement, particularly regarding payments. Advanced BIM models, enriched with temporal and financial dimensions, make it possible to combine verifiable milestones with achieved quantities, digital SALs, and advanced indicators. Upon the model documenting a condition that meets a specified criterion—such as the conclusion of a construction phase or the endorsement of a design modification—the smart contract can autonomously validate the condition and, contingent upon the configurations, authorize a payment, log a transaction, inform a party, or initiate a procedure. The integration of BIM and smart contracts formalizes computable connections across technical and administrative domains, thereby minimizing delays, misunderstandings, and disagreements.

The tertiary level of the architecture pertains to decision-making and validation processes. While numerous checks are challenging to automate due to their qualitative nature, a substantial category can be converted into computable rules. The relational requirements among items in the model, geometric consistency, adherence to dimensional limits, compatibility with information standards, and data completeness can be evaluated through defined procedures associated with smart contracts as activation conditions. The blockchain not only documents verification outcomes but also ensures their immutability and maintains transparency and traceability throughout the decision-making process.

The proposed framework defines a coherent operational architecture in which BIM, blockchain, smart contracts, and distributed storage are assigned complementary and non-overlapping roles.

The diagram shows a consistent framework for the management of information and contractual procedures in the construction industry, integrating BIM, blockchain, smart contracts, shared storage via IPFS, and an advanced system for version control using branching structures. The full ecosystem is controlled through an improved shared data environment called TLCCDE, which operates as a central coordination hub. The left side of the diagram emphasises the BIM model versioning module, where project revisions are represented as separate instances of the digital model. Each version is designed as a verifiable unit of information, associated with a single creator and fully documented to guarantee transparency and traceability. The IPFS element supervises the distributed storage of BIM files, allowing substantial information to be stored off-chain.

The system incorporates a multi-branch structure alongside standard versioning, enabling the representation of the collaborative process’s complexity through parallel branches focused on design disciplines, problem tracking, model dependencies, and design variants. This architectural decision acknowledges that BIM evolves non-linearly, manifesting as a multidisciplinary decision graph that blockchain technology can verify and protect against manipulation (Figure 1). The blockchain, positioned at the bottom center of the figure, serves as the system’s technological core: it maintains hashes, metadata, timestamps, and responsibilities, ensuring that every pertinent operation in the process is permanently and unambiguously recorded.

Figure 1.

Description of the distributed architecture incorporating BIM, blockchain, smart contracts, IPFS, and TLCCDE for testable management of information processes.

The centrally located TLCCDE acts as a collaborative platform that incorporates stakeholder contributions and coordinates interactions between BIM, blockchain and smart contracts. It is the channel for the transmission of variants, documents, authorisations and notifications, establishing an abstraction that combines the principles of the conventional CDE with the security offered by distributed systems. On top of the image are the main stakeholders—client, designer and contractor—who interact with the system by signing off documents, sending reviews or requesting checks, and using the blockchain to obtain objective records of the model status and contractual obligations.

On the right side is the intelligent contract module, segmented into functions for automated payments and dispute settlement. By using computational logic, the smart contract can validate the successful completion of milestones specified in the BIM model and autonomously authorise financial payments or start dispute verification and mediation. This element immediately links the technical scope of BIM with the administrative and legal domain of contracts, which minimises uncertainty and accelerates decision-making. The diagram shows an ecosystem defined by circular interactions between BIM, CDE, blockchain and IPFS, vertical connections between smart contracts and stakeholders, and cross-cutting connections involving versioning, dispute resolution, payments and data governance. The result is a coherent representation of a highly interoperable, distributed and automated information infrastructure ecosystem that can address industry inefficiencies and facilitate reliable and verifiable end-to-end procedures.

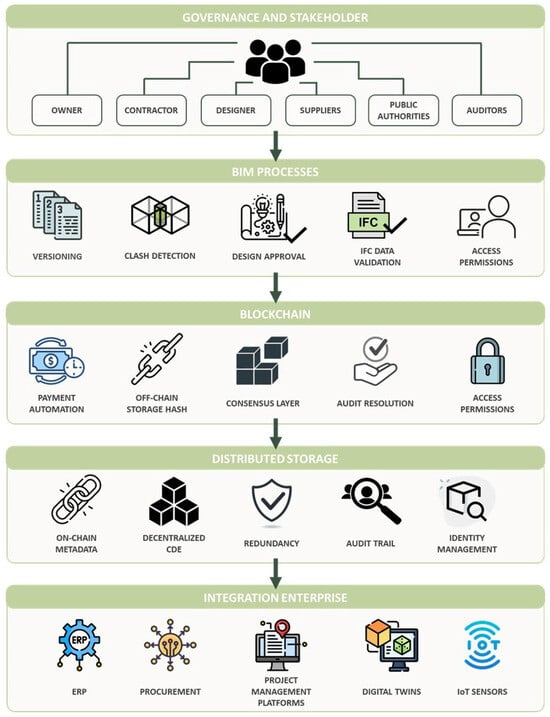

The multilayer representation of the proposed framework illustrates how the integration of BIM, blockchain, smart contracts, IPFS, and enterprise systems enables the development of a comprehensive, scalable information ecosystem that supports the entire life cycle of a construction project. Stakeholder engagement—comprising clients, designers, contractors, suppliers, governmental agencies, and auditors—establishes the decision-making framework and governance for the process. Subordinate to this level are the BIM processes, encompassing technical tasks such as version control, clash detection, design approval, IFC validation, and access authorization management. These operations immediately integrate with the blockchain, which serves as a secure platform for automating payments, storing off-chain hashes, validating metadata, resolving disputes, and managing access rights using smart contracts.

The layer for distributed storage, using systems like IPFS, complements the blockchain by enabling the storage of substantial BIM files within a scalable, redundant, and decentralized framework, thereby maintaining consistency between on-chain data and off-chain storage. The enterprise layer ultimately integrates the comprehensive framework with existing organizational management systems, including ERP platforms, digital procurement systems, project management tools, digital twins, and IoT sensor networks. This bidirectional link enables the conversion of technical and contractual data produced by the top layers into operational choices, process automation, real-time monitoring, and predictive analytics. The operational workflow of the proposed system is delineated by four algorithms: the on-chain BIM update framework, the automated milestone validation and payment process, the off-chain semantic verifications conducted by the computational oracle, and the conclusive on-chain registration of the review results. The algorithms are comprehensively outlined in Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D to guarantee reproducibility. The comprehensive framework is thus a highly interoperable system in which many technological and organizational levels communicate cohesively, diminishing uncertainty, enhancing transparency, and facilitating more efficient and verifiable administration of building projects (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Multilayer depiction of the framework linking stakeholders, BIM workflows, blockchain, distributed storage, and business systems.

Within this intricate structure, the research questions outlined in the introduction receive initial responses. Blockchain and smart contracts provide tangible mechanisms for mitigating inefficiencies and ambiguities, contingent upon their integration within an information ecosystem that utilizes BIM as the principal data source. The development of a cohesive architecture encompassing versioning, contract automation, and computable verification enables overcoming the constraints posed by discrete experiments, delineating a framework that, despite inherent obstacles, can serve as a robust foundation for tangible undertakings. The next chapter will explore the advantages and disadvantages of this framework, highlighting both the prospects and the conditions necessary for its credible and sustainable implementation in the construction sector.

5. Advantages and Limitations

The examination of the proposed framework and architectures presented in the preceding chapters reveals several tangible benefits for project management, alongside inherent structural constraints that hinder their complete implementation. The integration of BIM, blockchain, smart contracts and distributed storage systems allows several important and long-standing challenges within the industry to be resolved, thereby reducing information inefficiencies, contractual opacity and vulnerabilities in managing responsibilities. Despite its considerable potential, however, the technology does not in itself resolve the organisational, regulatory and operational challenges that characterise the construction supply chain. The advantages and disadvantages should be considered in a complementary way, as part of an important balance in assessing adoption.

A major advantage is blockchain’s ability to guarantee the traceability, immutability and verifiability of essential data. In circumstances where design information is frequently edited, swapped between various stakeholders and used to influence economic and operational decisions, having a distributed register that authenticates the history of each version is a big improvement. The integration with BIM simplifies the direct connection of model changes with stakeholder obligations, thereby reducing uncertainty and improving accountability. The implementation of multi-branched architectures provides an accurate and verifiable representation of the complexities of the digital model’s development, while the delegation of essential files to systems such as IPFS enables architectural scalability without adding to the burden on the registry.

A secondary advantage concerns economic and contractual aspects. Smart contracts facilitate the automation of key operations, including payments contingent upon verification of milestone achievements within the model, as well as the start of review or dispute resolution processes. This reduces the time required for verification, mitigates the risk of payment delays, and improves transparency between the client, contractor, and subcontractors. The BIM model provides a computable representation of the project’s progress, allowing smart contracts to act as neutral intermediaries that fulfil predefined conditions, thereby minimising subjective interpretations and the probability of disputes. The outcome is a more predictable, stable, and automatable system, even from an administrative perspective.

The architecture improves consistency and uniformity between CDEs, blockchains, and enterprise systems from an information process management perspective. The use of an advanced CDE such as TLCCDE makes it easier to integrate variants, authorisations, documents, and notifications into a unified platform, which improves the smoothness of transitions between design tasks and management procedures. The layered design facilitates integration between the model’s technical domain and the operational domains of ERP, IoT, and digital twin systems, thereby enabling sophisticated scenarios for real-time monitoring, predictive modeling, and control during both construction and operational phases.

Despite these strengths, the framework’s applicability is partially constrained by several restrictions. A primary restriction is the quality and organisation of BIM data. Even though digital models are getting denser and more complex, a lot of the info needed for contract and evaluation processes still is not properly represented in a computable way. Most technical valuations need human interpretation, expert judgement, and contextual analysis, which are difficult to code into logical rules suitable for a smart contract. This indicates that automation can operate only on a subset of operations, and the complete digitization of the contract remains a potential rather than an operational reality.

Another constraint is the design’s scalability and complexity. Implementing blockchain incurs unavoidable computational costs and requires a resilient infrastructure capable of handling large volumes of transactions and consensus verification without significant delays. Moreover, the existing fragmentation of technology—several BIM platforms, disparate IFC standards, and blockchains with non-interoperable consensus mechanisms—hinders the establishment of cohesive, genuinely open ecosystems. The framework needs participants to be pretty digitally savvy, to set up innovative and distributed governance structures, and to collectively approve automated processes, which calls for some serious cultural and regulatory changes.

The legal dimension is a further cause for concern. Although smart contracts can consistently meet requirements, their legal validity and integration with conventional contracts depend on the legislative environment and the ability to formally establish complex provisions without sacrificing interpretative flexibility. Blockchain presents new challenges in data security, liability for code malfunctions, and digital identity management. It is crucial to recognise that technology can improve operations, even if it cannot completely replace the function of settled legal norms and practices.

The integrated BIM–Blockchain–Smart Contracts architecture has significant potential to improve transparency, efficiency, and reliability in building projects. To transform these advantages into widespread practical applications, a pragmatic strategy is required that recognises existing limitations, promotes standardisation, and promotes the simultaneous advancement of organisational, regulatory, and technical standards. The system can only realise its full potential through a balance between digital innovation and institutional adaptation.

6. Enabling Conditions for Adopting the Framework

The successful implementation of the integrated framework of BIM, blockchain, smart contracts, and distributed storage systems should not be seen as a simple technological endeavor. Implementation requires a set of favourable conditions that encompass the technical, organisational, regulatory and cultural aspects of the construction supply chain. Without these conditions, the technology may be confined to isolated trials or preliminary demonstrations, without having a substantial impact on actual processes. Favourable conditions are a prerequisite for potential benefits to translate into actual change.

The first critical factor concerns the digital maturity of organisations. Integrating BIM with blockchain requires models and information flows to be pre-structured, consistent and unified. This suggests the ability of stakeholders to generate high-quality BIM models that comply with common standards and have an adequate level of semantic organisation. Incomplete and inconsistent models, particularly those that lack universal classification criteria, hinder the automation of controls, the activation of smart contracts and the registration of crucial information on the blockchain. Digital maturity includes not only the generation of information, but also the presence of internal systems that systematically facilitate versioning, validation and quality control.

The existence of interoperable standards and protocols is crucial, in addition to the technical aspect of BIM. Implementing blockchain and smart contracts requires explicit delineation of roles, permissions, governance protocols, data formats, and verification processes. In the lack of a unified set of regulations, the framework is susceptible to disintegration into proprietary deployments that lack interoperability, thereby reducing the effectiveness of blockchain as a shared trust infrastructure. Standards such as IFC, MVD, ISO 19650 [61] or formalised authorisation methods must be merged with technical requirements for smart contracts, digital identity management and distributed auditing systems. An ecosystem of coordinated standards is essential to extend the framework beyond stand-alone pilot projects.

A further enabler is the institution of a distributed governance mechanism capable of coordinating stakeholders and regulating the use of blockchain and smart contracts. Technology alone does not determine who is authorised to act, which contract clauses can be automated, how to resolve conflicts, or how to establish write and read permissions. It is essential to develop mutual interaction protocols, delineate responsibilities, and implement independent verification procedures. Governance must also address digital identity management, the safeguarding of sensitive information, and the establishment of intermediary entities capable of supervising the implementation of the system in complex projects.

The framework necessitates computable processes and data quality requirements for verification and contract automation procedures. Smart contracts can solely automate processes that can be encapsulated in logical rules. Consequently, a substantial amount of the information presently transmitted in projects must be reorganized to facilitate automatic evaluation of its condition. This encompasses milestones, digital SALs, design specifications, compliance criteria, and performance indicators. The lack of formalizable data constrains automation and necessitates the retention of extensive grey zones reliant on human interpretation, hence diminishing the advantages of blockchain utilization.

A crucial requirement is infrastructure capability, encompassing both technological and organizational aspects. Blockchain implementation requires stable networks, reliable distributed nodes, consensus algorithms tailored to the performance demands of the AEC context, and robust, secure off-chain storage systems. Moreover, the connection with corporate systems—such as ERP, digital procurement, digital twins, or IoT sensors—requires that organizations maintain a cohesive, modular IT architecture with interfaces that enable interoperability and bidirectional data synchronization. Inadequate infrastructure compromises the stability of the system and can create bottlenecks that reduce its effectiveness.

Ultimately, implementing the regulatory framework requires a significant cultural shift among participants. The collaborative, transparent and verifiable characteristics of blockchain clarify tasks and decisions that may be implicit or negotiable in traditional practices. This transformation requires trust in technologies, openness to changing ingrained behaviours, and the ability to operate within more organised frameworks that rely less on informal mediation. A legislative framework is needed that recognises the legal validity of distributed ledgers, smart contracts, and signed digital documents, thus avoiding ambiguities and interpretation issues.

The effective adoption of the BIM–Blockchain–Smart Contracts framework requires a convergence of digital maturity, standardised protocols, decentralised governance, adequate infrastructure, information computability criteria, and a supportive organisational culture. These circumstances form the essential basis for technological change to produce concrete, lasting, and collective benefits throughout the entire construction supply chain.

7. Application Scenarios

The automation of the tasks associated with work progress reports (WPRs) is a key application scenario for assessing the actual effectiveness of the combination of BIM, blockchain and smart contracts. Issuing WPRs in a conventional context requires the involvement of multiple specialists, involves manual checks, requires the exchange of documents and can cause delays or incorrect communications related to payments (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Automation of the Work Progress Report workflow utilizing IFC, semantic oracle, and smart contracts for milestone verification.

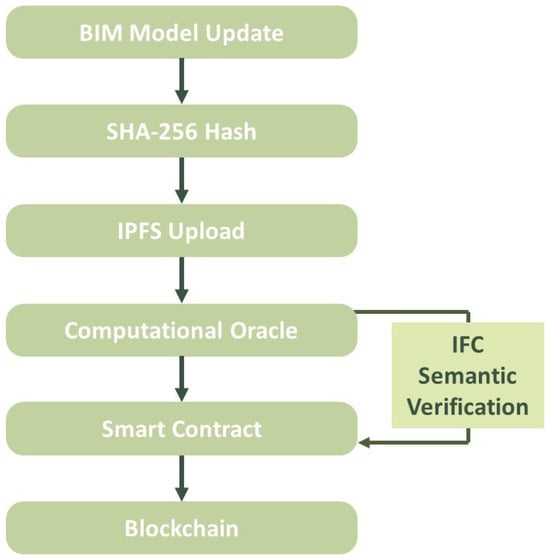

Let us examine a construction project in which the structural, architectural and plant engineering components are modelled in accordance with the IFC 4.3 standard. Each element of the BIM model has a range of attributes that define quantities, progress and associated contractual milestones. After completing a construction phase, the contractor reviews the BIM model, producing a new version that is submitted to the CDE. The system autonomously generates a distinct SHA-256 hash of the file, which is documented on the blockchain. The file is stored on IPFS to prevent overloading the registry.

The procedure includes not only the transmission of the reviewed model, but also the documentation of the blockchain of essential metadata, such as the reference milestone, the person responsible for the update and the timestamp of the edit. Thus, each iteration of the BIM model becomes a traceable, verifiable object with defined accountability. The operators’ digital signatures make sure that only authorised people can take part in moving the activity forward, cutting down the risk of tampering.

At this point, a key part of the system comes in: the computational oracle. The blockchain inherently lacks the capacity to interpret the semantic content of the IFC file directly; the oracle retrieves the model from IPFS, analyzes its structure using libraries such as IfcOpenShell, and confirms that the stated modification aligns with the model’s content. This involves verifying numbers, milestone attributes, the integrity of information, and compliance with previous versions. The oracle then generates a digital certificate confirming the verification and transmits it to the designated smart contract.

The smart contract executes a sequence of logical checks: it confirms that the milestone has not been previously compensated, that the validator’s signature is included, and that the semantic evaluation is affirmative. Once all conditions are met, the contract automatically authorises the milestone payment. The transfer is documented on the blockchain as an unchangeable transaction, ensuring the transparency and verifiability of the process (Appendix B).

The main advantage lies in the system’s ability to remove discretion and delays: the entire SAL-progress-payment cycle becomes a deterministic procedure governed by verifiable codes. The blockchain serves as a reliable infrastructure, whereas BIM provides the information from which automated decisions are generated.

Moreover, the system’s architecture facilitates its extension to sub-processes such as variation management, compliance verification, or monitoring through IoT sensors. Information from the construction site can be incorporated into the BIM model and evaluated automatically, establishing a continuous cycle of information status, control, verification, and payment.

The system architecture needs the blockchain info to be organised really carefully to make sure BIM procedures can be tracked, cannot be changed, and can be checked. The on-chain data structure comprises a collection of model update records, each represented as a tuple containing the IFC file hash (fileHash), the model version (modelVersion), the milestone identification (milestoneID), the approving validator (validator), and the event timestamp (Appendix A). This concise and predictable approach enables each BIM model version to be associated with a cryptographic proof, thereby removing uncertainty in process reconstruction and enabling a distributed, autonomous audit.

A smart contract made in Solidity works on this data structure, with the job of automating contract procedures, especially checking key milestones and making payments. The smart contract administers a registry of milestones, specifying their quantity, completion status, and payment status. The authorized validator can verify the model modification by linking an IFC hash to a milestone, creating an immutable event on the blockchain. After verifying the technical conditions and avoiding duplications or unauthorised payments, the contract can proceed with the automatic execution of the financial transfer to the contractor. The integration of events, security modifiers and logical controls improves the robustness and resilience of the contract, ensuring that each stage is verifiable and that the administrative logic derives directly from the status of the certified information in the BIM model.

Second Application Case—Automated Design Review Using BIM and Smart Contracts

A second notable application case pertains to the automation of design review, one of the most onerous, iterative, and subject to subjective interpretation processes within the entire design cycle. In public projects, design compliance verification must adhere to many codified and regulatory standards, encompassing geometric, performance, and safety requirements. In this case, evaluate a project to ensure that all doors comply with the minimum height required by regulations, that ramps maintain slopes within the permitted limits, that each emergency exit is accurately marked and compliant, and that interference between disciplines does not exceed the 2% threshold identified by interference detection. Traditionally, these evaluations require time-consuming assessments that rely heavily on the technician’s expertise, leading to significant ambiguity and inadequate accountability.

The proposed architecture transforms the entire process into a computable sequence that incorporates BIM, blockchain, and smart contracts. Upon the designer’s upload of a new IFC model version to the CDE, the system autonomously calculates the cryptographic hash of the file. It documents it on the blockchain, establishing immutable evidence of the design modification. A computational oracle concurrently executes a series of predefined evaluations (design rule checks) utilizing a semantic verification engine that interprets the attributes of the IFC model, including door heights, ramp slopes, emergency exit classifications, and disciplinary collision statistics. The oracle juxtaposes these principles against regulatory and contractual stipulations, producing a structured and digitally signed report to ensure its integrity and provenance (Appendix C).

The smart contract for design review receives the signed verification result and records it on the blockchain, thereby ensuring full traceability of the control operations. Upon completion of a review, the contract autonomously updates the design milestone status and initiates any subsequent procedures within the CDE; conversely, an immediate message is dispatched to the pertinent stakeholders, clearly detailing the identified non-conformities. The entire procedure is permanently documented, facilitating complete reconstruction of the verification chain and ruling out any retroactive manipulation of results.

Responsibilities are fully traceable, as each participant leaves a digital signature, allowing each decision to be connected to the specific version of the model used. The decentralised nature of the blockchain allows for independent audits, mitigating the risk of disputes and increasing participant confidence. Consequently, design review has evolved from a static, subjective procedure into a rigorous, transparent, and automated workflow that improves design quality and mitigates risks in subsequent phases of the construction cycle.

In automated design review, the control mechanism is segmented into two complementary tiers: an off-chain oracle that conducts semantic evaluations of the IFC model and an on-chain smart contract that permanently documents the review’s results. The oracle code, implemented in Python using IfcOpenShell (version 0.7.0; https://ifcopenshell.org, accessed on 15 November 2025), imports the IFC file associated with the BIM model and performs a series of checks on the design rules defined as computable conditions. This includes validating the minimum height of doors, assessing the maximum slope of ramps, verifying the presence and correct identification of emergency exits, and ensuring compliance with a maximum conflict threshold between different disciplines. The oracle consolidates the various outcomes into a cohesive data structure that includes the model hash, the Boolean values about the specific rules, the overall result, and a pointer to a comprehensive report (e.g., a JSON or PDF stored on IPFS). The structure is then digitally signed to ensure the integrity and non-repudiation of the verification result.

The Solidity smart contract operates on the basis of this result without re-running the geometric validations; its purpose is not to ‘re-evaluate the evaluation,’ but to validate its existence and authority within a shared ledger. The contract defines a review structure that incorporates the model hash, the overall result (pass/fail), the report URI, the reviewer address, and the record timestamp. An indexed mapping, such as a reviewID generated from the model hash and review cycle, enables historical reviews to be retrieved at any time. Only specifically authorised reviewer addresses can use the submitReview function, which creates a new on-chain record and triggers a DesignReviewed event, allowing the CDE to update the project status and automatically notify stakeholders (Appendix D). As a result, the responsibility for oversight remains with the oracle and its administrators. At the same time, the blockchain provides unchangeable and verifiable proof of the decisions made, reducing the uncertainties inherent in conventional verification methods and allowing for a complete reconstruction of the review process even after a significant amount of time has passed.

8. Validation of Framework

The validation of the BIM–Blockchain–Smart Contracts framework necessitates a holistic approach rather than a mere point-by-point verification of individual components, as it must assess the entire information chain, from data generation in the BIM model to the automated execution of contractual logic on the blockchain. This study involved validation via a proof-of-concept software that incorporates an IFC parsing engine, a semantic verification oracle, a distributed storage system using IPFS, a private blockchain using a Proof-of-Authority consensus mechanism, and a collection of smart contracts written in Solidity. The objective is not to showcase the system’s perfection, but to ascertain whether the framework is technically coherent, fully operational, and adequately performant to be deemed adoptable in practical settings, at least in a pilot capacity.

Operationally, authentic BIM models in IFC 4.3 format were used across architectural, structural, and plant engineering disciplines, totaling about 180 MB of data. The models were uploaded to a simplified CDE environment, which manages version updates and the interaction with other components. Each new version of the model produces a cryptographic hash calculated through SHA-256; this hash is documented on the blockchain along with critical metadata, such as the timestamp and the name of the person who uploaded it, while the effective IFC file is stored on IPFS. This creates a clear division between substantive off-chain data and on-chain integrity verification, an essential prerequisite for supporting system scalability.

During the project review, the same engine evaluates geometric and performance criteria, including minimum door heights, ramp slopes, accurate identification of emergency exits, and compliance with maximum interference limits between disciplines. The results of these verifications are compiled into a concise data structure that includes the model hash, the overall result, and a reference.

Smart contracts function based on this result without reiterating the technical verifications. The agreement governing milestones and payments ensures that the milestone linked to a specific model version remains unsettled, that the validator is among the authorized parties, and that the result of the semantic verification is affirmative. Payment is authorized, and a transaction is generated that permanently records the transfer only when all these conditions are satisfied. The contract documenting design review outcomes maintains a record for each review, including the model hash, verification result, report reference, and reviewer’s identity; this facilitates the reconstruction of the review history and the transparent attribution of responsibilities.

The validation encompassed both logical accuracy and performance considerations. Regarding accuracy, all iterations of the models used were accurately documented on the blockchain, and no update operation overwrote existing data. Each modification generated a new transaction, affirming the ledger’s append-only characteristic. The concordance between off-chain data and on-chain hashes was confirmed by recalculating the hashes of files retrieved from IPFS and comparing them with the data stored on the blockchain, revealing no inconsistencies. The oracle’s semantic checks accurately detected non-conformities deliberately embedded in the test models and produced findings aligned with human assessment, in accordance with the established standards.

From a performance perspective, average processing times showed suitability for practical use in non-extreme conditions. IFC model analysis and control rule execution often took 0.3–0.9 s per model, depending on file complexity, while uploading to IPFS and spreading blocks across the network resulted in latencies of several hundred milliseconds. Transactions on the PoA blockchain used in the tests were validated in an average of three to five seconds, with an overall latency from model update to payment release of a few seconds, which is entirely acceptable compared to the durations typically associated with administrative processes in the construction industry. The registered throughput means it’s possible to handle a significant number of daily milestones without any apparent loss of performance; however, scenarios with significantly higher volumes would require further optimisation or the implementation of layer 2 solutions.

The entire logic implemented during the validation tests aligns with Algorithm A2 (Appendix B) for milestone verification and payment disbursement, and with Algorithms A3 and A4 (Appendix C and Appendix D) for the semantic review process. All variables, data flows, and decision criteria are thoroughly delineated in the appendices.

The validation also underscored structural constraints. The quality and uniformity of IFC models are crucial; inconsistencies in property definitions or the absence of relevant verification information ultimately result in incomplete automation. Moreover, reliance on oracles, albeit alleviated by digital signatures and authorization constraints, introduces an external trust component to the blockchain that needs to be resolved through governance and certification procedures. Ultimately, scalability is determined by the selection of a blockchain platform and the volume of monitored events: the proof of concept illustrates the technological viability of the framework. However, it does not fully address its applicability in national or multi-project ecosystems.

The validation used three authentic IFC models for architecture, structural engineering, and plant engineering, totaling roughly 180 MB of data. The models comprise more than 62,000 entities and over 1.2 million total properties, exemplifying the typical complexity of a medium-scale project. The efficacy of the complete process was evaluated using this dataset: The SHA-256 computation requires 18 to 41 milliseconds; uploading to IPFS ranges from 0.4 to 1.1 s based on file size; IFC parsing with IfcOpenShell fluctuates between 0.32 and 0.91 s; semantic verification of the oracle spans 0.11 to 0.37 s; and on-chain transaction finalization (Proof-of-Authority) takes between 3.4 and 5.2 s. The measurements, repeated across 30 iterations for each model, establish a quantitative baseline that facilitates the evaluation of the framework’s sustainability in real-world contexts and serves as a valuable reference for future performance comparisons, including multi-project scenarios or those with elevated update frequencies.

The validation demonstrates that the proposed framework can operate consistently across the entire information chain, ensuring traceability, immutability, and automating essential activities. At the same time, the performance achieved aligns with incremental adoption scenarios. Simultaneously, it underscores the necessity of ongoing data standardization, the establishment of governance frameworks for oracles, and extensive experimentation to facilitate a robust and sustainable transition from proof of concept to operational infrastructure.

Discussion

The validation of the framework and the analyzed application scenarios facilitates critical reflection on the actual extent of integration among BIM, blockchain, and smart contracts within the construction industry. Evidence indicates that integrating these technologies can profoundly affect the management of information and contractual processes, introducing a degree of control, traceability, and automation that is challenging to achieve with conventional systems. The results collected reveal certain structural limits arising from both the nature of the technologies and the organizational and regulatory context in which they function.

It is important to note that, although blockchain offers a decentralised trust framework, it is not sufficient to address the inherent uncertainties of construction processes. The immutability of the ledger ensures transparency of actions taken and accurate accountability; however, the quality of the recorded data depends entirely on the information model and verification mechanisms implemented upstream. Validation has established that the oracle’s function is crucial: in the absence of a semantic engine proficient in consistently interpreting IFC models, blockchain serves as a dependable yet unseen repository. This underscores a tension recognized in the computer science literature on hybrid on-chain/off-chain systems. While the distributed system can provide execution security, it cannot independently address semantic deficiencies in the underlying data. The framework achieves its maximum efficacy only when BIM models are sufficiently structured and consistent to facilitate automated verification.

These considerations necessitate contemplation regarding the computable character of the existing standards. A significant part of the IFC model is inappropriately formalised and subject to interpretation, making it tricky to translate design or performance requirements into logically verifiable rules. This shows that fully integrating BIM and smart contracts requires information standards to become more stringent, with object characteristics outlined more precisely and better suited to automated processing. The research on the topic substantiates this necessity and suggests that the shift to a genuinely machine-interpretable environment is still in its nascent stages.

A comparison with prior contributions underscores that the primary value of the framework is in its capacity to formalize and stabilize processes that presently rely on subjective interpretations. The automation of SAL and design review signifies a tangible advancement in this regard: blockchain provides an autonomous assurance mechanism, while smart contracts convert contractual stipulations into verifiable logic. However, experience confirms that the automation cannot be absolute. Fundamental verification standards, including geometric or quantitative criteria, can be easily implemented; but qualitative, discretionary, or technical elements of judgement inherently resist rigorous formalisation. This does not mean that the model is failing, but rather suggests that the framework should be considered a support tool, not a substitute for professional practices.

Performance investigations suggest that current blockchain infrastructures, when properly configured, can withstand substantial loads without sacrificing system responsiveness. The documented validation times are suitable for operational use, acknowledging that building procedures often do not require high-frequency transactions. Nonetheless, scalability requires meticulous consideration, particularly in the context of extensive projects or multi-project ecosystems. The existing throughput and latency constraints, although not significant in the evaluated contexts, may become more pronounced in intricate scenarios, suggesting the potential to implement strategies such as rollups or validiums to handle elevated loads without compromising the characteristics of the distributed system.

An often-neglected facet of decentralized models in the building industry concerns the actual scalability of blockchain systems and their reliance on well-defined governance frameworks. The analyzed case demonstrates that the implementation of a Proof-of-Authority consensus method facilitates transaction finalization timeframes ranging from 3 to 6 s, a throughput sufficient for the information flows of a CDE, although not comparable to multi-project scenarios with elevated update frequencies. The suggested architecture intentionally refrains from on-chain insertion of IFC files, storing only hashes and metadata, thereby alleviating network traffic; however, it raises concerns about scalability if the volume of concurrent validations escalates substantially. In this scenario, network governance assumes a pivotal role: the delineation of validators, their institutional obligations, onboarding protocols, auditing frameworks, and revocation criteria are critical components in guaranteeing the trustworthiness and impartiality of the process. The same rationale applies to computational oracles, which serve as the interface between the IFC model and smart contracts, requiring verifiable trust protocols, cross-verifications, and openness in the computational rules. The interplay of these factors indicates that the scalability of the framework relies not solely on the blockchain network’s efficiency, but also on the establishment of a coherent, accountable, and technically auditable governance system that can facilitate the progressive development of the distributed information flow over time.

From an organizational perspective, the findings indicate that the primary difficulty is not solely technology, but also socio-technical. A system that ensures the transparency and immutability of activities undertaken by players in the supply chain requires cultural and procedural alignment that cannot be assumed. The proposed framework reduces the likelihood of interpretive variance. It clarifies responsibilities, thereby enhancing process control and predictability, but it requires participants to adopt a greater degree of procedural discipline than is currently common. The technology functions solely when situated within a context that aligns with its aims and adheres to uniform operational norms.

The comprehensive discourse affirms that, while the framework is technically robust and capable of yielding substantial advantages, it is not a “plug-and-play” solution. The efficacy depends on the maturity of BIM data, the presence of uniform standards, the delineation of computable processes, the availability of reliable infrastructure, and stakeholders’ capacity to embrace novel forms of distributed governance. This insight does not diminish the model; instead, it contextualizes it, demonstrating that the technology is sufficiently advanced to manage essential activities but necessitates a correspondingly developed support ecosystem. The convergence of BIM and distributed technologies represents not only a technical transformation, but also an epistemological shift in information management in the construction industry, which can reduce uncertainty, increase transparency, and foster better conditions for collaboration and accountability among stakeholders.

9. Conclusions

This study examined the feasibility of consolidating BIM model updates, distributed storage, semantic validation, and smart contract execution into a cohesive, verifiable workflow. The findings from the proof-of-concept demonstrate that the proposed architecture can facilitate an auditable sequence of operations that connects the generation of IFC data, the off-chain verification procedure, and the on-chain documentation of contractual statuses. These findings demonstrate the potential of decentralized information management to improve the dependability and accountability of building processes; however, they should be regarded as preliminary and not indicative of comprehensive operational implementation.

The validation was conducted under controlled, simplified conditions, with a limited number of stakeholders, deterministic model updates, and a network setup that does not yet reflect the concurrency and variability characteristics of actual construction projects. The system’s scalability under high-frequency versioning, its performance in multi-project situations, and the reliability of the oracle method remain unassessed. The governance framework implemented in the proof-of-concept is deliberately simplistic; subsequent research must address more intricate trust models, institutional authorizations, auditor responsibilities, and procedures for revocation or dispute resolution.

Notwithstanding these constraints, the study offers a reliable and replicable technical framework, underpinned by clear data formats, algorithms, and baseline performance metrics. This facilitates the connection between theoretical blockchain models and practical BIM-integrated processes. Future research will broaden the experimental assessment to larger-scale scenarios, examine additional consensus mechanisms and storage structures (including side-chains and state channels), and investigate privacy-preserving solutions such as zero-knowledge proofs. The concurrent implementation of semantic ontologies (OWL, SHACL) and AI-driven model interrogation methods may enhance the computability and resilience of the verification process. These advancements are anticipated to reinforce the implementation of decentralized workflows in actual construction settings, aligning digital processes with enhanced assurances of transparency, auditability, and contractual integrity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L. and D.S.; methodology, L.C. and A.L.; software, L.C.; validation, S.A., F.C. and D.S.; formal analysis, S.A. and L.C.; investigation, L.C. and A.L.; resources, S.A. and C.V.; data curation, L.C., A.L. and C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C. and A.L.; writing—review and editing F.C. and D.S.; visualization, S.A., L.C. and C.V.; supervision, F.C. and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEC | Architecture, Engineering and Construction |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| CDE | Common Data Environment |

| CID | Content Identifier (IPFS) |

| DLT | Distributed Ledger Technology |

| ERP | Enterprise Resource Planning |

| ETH | Ether (Ethereum cryptocurrency) |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HASH | Cryptographic Hash Value (e.g., SHA-256) |

| IFC | Industry Foundation Classes |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IPFS | InterPlanetary File System |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LOD | Level of Development |

| MVD | Model View Definition |

| OID | Object Identifier |

| OWL | Web Ontology Language |

| PBFT | Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance |

| PoA | Proof of Authority |

| PoC | Proof of Concept |

| QA | Quality Assurance |

| QC | Quality Control |

| SAL/WPR | Work Progress Report |

| SC | Smart Contract |

| SHA-256 | Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit |

| SHACL | Shapes Constraint Language |

| SQL | Structured Query Language |

| TLC | Two-Layer Container |

| TLCCDE | Two-Layer Container Common Data Environment |

| URI | Uniform Resource Identifier |

| VM | Virtual Machine |

| ZK/ZKP | Zero-Knowledge/Zero-Knowledge Proof |

Appendix A

On-Chain Data Structure for Recording BIM Updates

This technique defines the essential data structure to associate each iteration of the BIM model with a contractual milestone, ensuring traceability, immutability, and distinct allocation of obligations via hashes, timestamps, and validator identities.

| Algorithm A1. BimUpdate data structure stored on-chain |

| Input: fileHash, modelVersion, milestoneID, validator Output: A persistent, immutable BimUpdate record Structure BimUpdate: fileHash ← hash crittografico del file IFC (SHA-256 o CID IPFS) modelVersion ← numero progressivo della versione BIM milestoneID ← identificatore della milestone contrattuale timestamp ← momento della registrazione su blockchain validator ← identità digitale del validatore che ha caricato la versione End Structure |

Appendix B

Milestone Management and Automated Payments

This method delineates the comprehensive process enabling the system to authenticate a milestone following a new update of the BIM model and, subsequently, to autonomously disburse the anticipated payment, utilizing the deterministic logic of smart contracts.

| Algorithm A2. Automatic milestone validation and payment release |

| Given: milestones ← insieme delle milestone registrate validators ← insieme dei validatori autorizzati contractor ← beneficiario dei pagamenti Procedure RegisterMilestone(milestoneID, amount): Require caller = owner milestones[milestoneID].amount ← amount milestones[milestoneID].completed ← false milestones[milestoneID].paid ← false End Procedure Procedure ValidateBimUpdate(milestoneID, fileHash): Require caller ∈ validators Require milestones[milestoneID].completed = false bimHashes[milestoneID] ← fileHash milestones[milestoneID].completed ← true Emit MilestoneCompleted(milestoneID, fileHash, currentTime) End Procedure Procedure ReleasePayment(milestoneID): Require caller ∈ validators Require milestones[milestoneID].completed = true Require milestones[milestoneID].paid = false milestones[milestoneID].paid ← true Transfer milestones[milestoneID].amount → contractor Emit PaymentReleased(milestoneID, amount, currentTime) End Procedure |

Appendix C

Off-Chain Semantic Design Review

The algorithm demonstrates the semantic verification process executed off-chain by a computational oracle: it analyzes the IFC model, applies the design review criteria, and produces a synthetic result along with a structured report archived in distributed storage.

| Algorithm A3. Off-chain semantic design review |

| Input: IFC_file, model_hash Output: DesignCheckResult containing rule outcomes and global verdict Load IFC model from IFC_file //Rule 1—door height doors_ok ← true For each door in IFC: If door.height < MIN_DOOR_HEIGHT: doors_ok ← false End For //Rule 2—ramp slope ramps_ok ← true For each ramp in IFC: If ramp has no geometric parameters: ramps_ok ← false Else if ramp.height/ramp.length > MAX_RAMP_SLOPE: ramps_ok ← false End For //Rule 3—emergency exits exits_ok ← (number of doors tagged “EMERGENCY_EXIT” ≥ 1) //Rule 4—clash ratio clash_ratio ← read IFC property “ClashRatio” (default = 0) clash_ok ← (clash_ratio ≤ MAX_CLASH_RATIO) //Global verdict all_ok ← doors_ok ∧ ramps_ok ∧ exits_ok ∧ clash_ok Return DesignCheckResult(model_hash, doors_ok, ramps_ok, exits_ok, clash_ok, all_ok, report_uri) milestones ← insieme delle milestone registrate validators ← insieme dei validatori autorizzati contractor ← beneficiario dei pagamenti |

Appendix D

On-Chain Recording of Design Review Results

This algorithm delineates the process by which the results of the design review are documented on the blockchain, establishing immutable evidence of the outcome, the reviewer, and the corresponding report, thereby unifying the information flow between off-chain verification and on-chain documentation.

| Algorithm A4. On-chain recording of design review results |

| Given: authorizedReviewers ← insieme delle identità autorizzate reviews ← archivio delle review esistenti Procedure SubmitReview(reviewID, modelHash, passed, reportURI): Require caller ∈ authorizedReviewers Require reviews[reviewID] does not yet exist newReview.modelHash ← modelHash newReview.passed ← passed newReview.reportURI ← reportURI newReview.reviewer ← caller newReview.timestamp ← currentTime reviews[reviewID] ← newReview Emit DesignReviewed(reviewID, modelHash, passed, caller, reportURI, currentTime) End Procedure |

References

- Sacks, R.; Eastman, C.; Lee, G.; Teicholz, P. BIM Handbook; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781119287537. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, R.; Rodrigues, H.; Costa, A.; Rodrigues, F. Building Condition Indicators Analysis for BIM-FM Integration. In Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering; Springer Science + Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Costa, A.A.; Silvestre, J.D.; Pyl, L. Integration of LCA and LCC Analysis within a BIM-Based Environment. Autom. Constr. 2019, 103, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, J.; Parlikad, A.K.; Schooling, J. Design and Development of BIM Models to Support Operations and Maintenance. Comput. Ind. 2019, 111, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamledari, H.; Fischer, M. Measuring the Impact of Blockchain and Smart Contracts on Construction Supply Chain Visibility. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 50, 101444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotta, V.; Mariniello, G.; Asprone, D.; Botta, A.; Manfredi, G. Integration of Blockchains and Smart Contracts into Construction Information Flows: Proof-of-Concept. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]