Rethinking Cities Beyond Climate Neutrality: Justice and Inclusion to Prevent Climate Gentrification

Abstract

1. New Rules, Tools, Procedures, and Operational References for a Socially and Eco-Sustainable Approach to Urban Regeneration

2. Methodology

- Documentary analysis, aimed at constructing the theoretical framework of reference;

- Case study analysis, aimed at comparing market-driven and strongly public-led urban regeneration projects;

- Comparative analysis, focused on defining preliminary guidelines to inform environmentally and socio-economically sustainable urban regeneration interventions capable of preventing the phenomenon of climate gentrification.

- Urban welfare and the public city: the role of public spaces and essential services in promoting equity and social cohesion;

- Integrated socio-environmental crisis: definitions and interconnections between environmental challenges (climate crisis) and social challenges (inequality, urban poverty, housing exclusion);

- Climate gentrification and spatial justice: analysis of the dynamics of social displacement caused by climate adaptation measures and “green” urban regeneration initiatives.

- Thematic relevance: eligible cases had to display either dynamics of climate gentrification or, conversely, successful practices in promoting climate and social justice;

- Geographical variety: two case studies were selected from different urban contexts in order to highlight their specificities and to provide a generalised, internationally relevant framework of the issue.

- Strategic vision and governance;

- Housing and mobility accessibility;

- Distribution of environmental benefits;

- Employment generation and community empowerment;

- Safeguarding of cultural and social identity.

3. First Phase: Documentary Analysis

3.1. An Integrated Socio-Environmental Crisis

3.2. Climate Gentrification and Spatial Justice

4. Second Phase: Case Study Analysis

4.1. A Case of Climate Gentrification: The Secondary Migration of Little Haiti

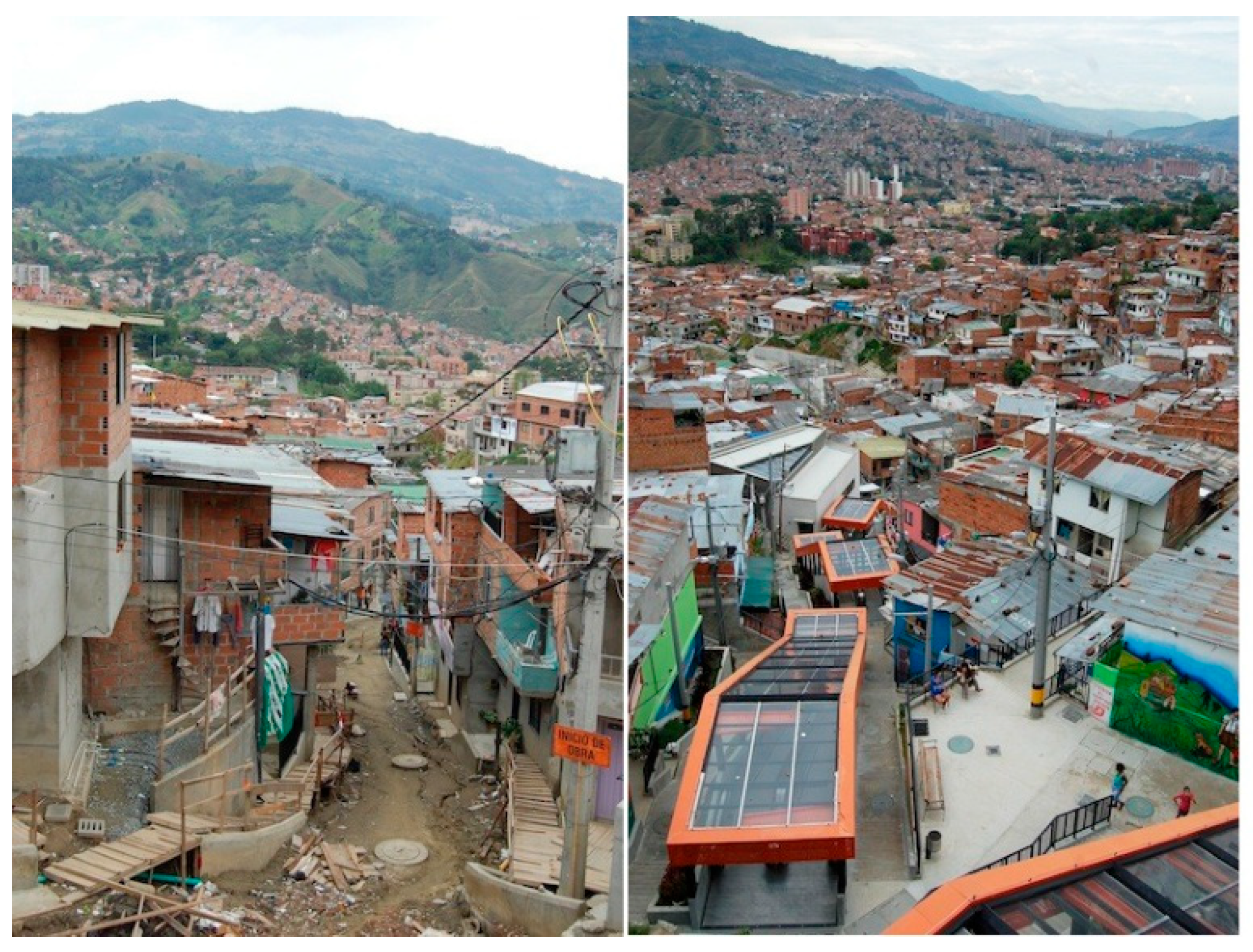

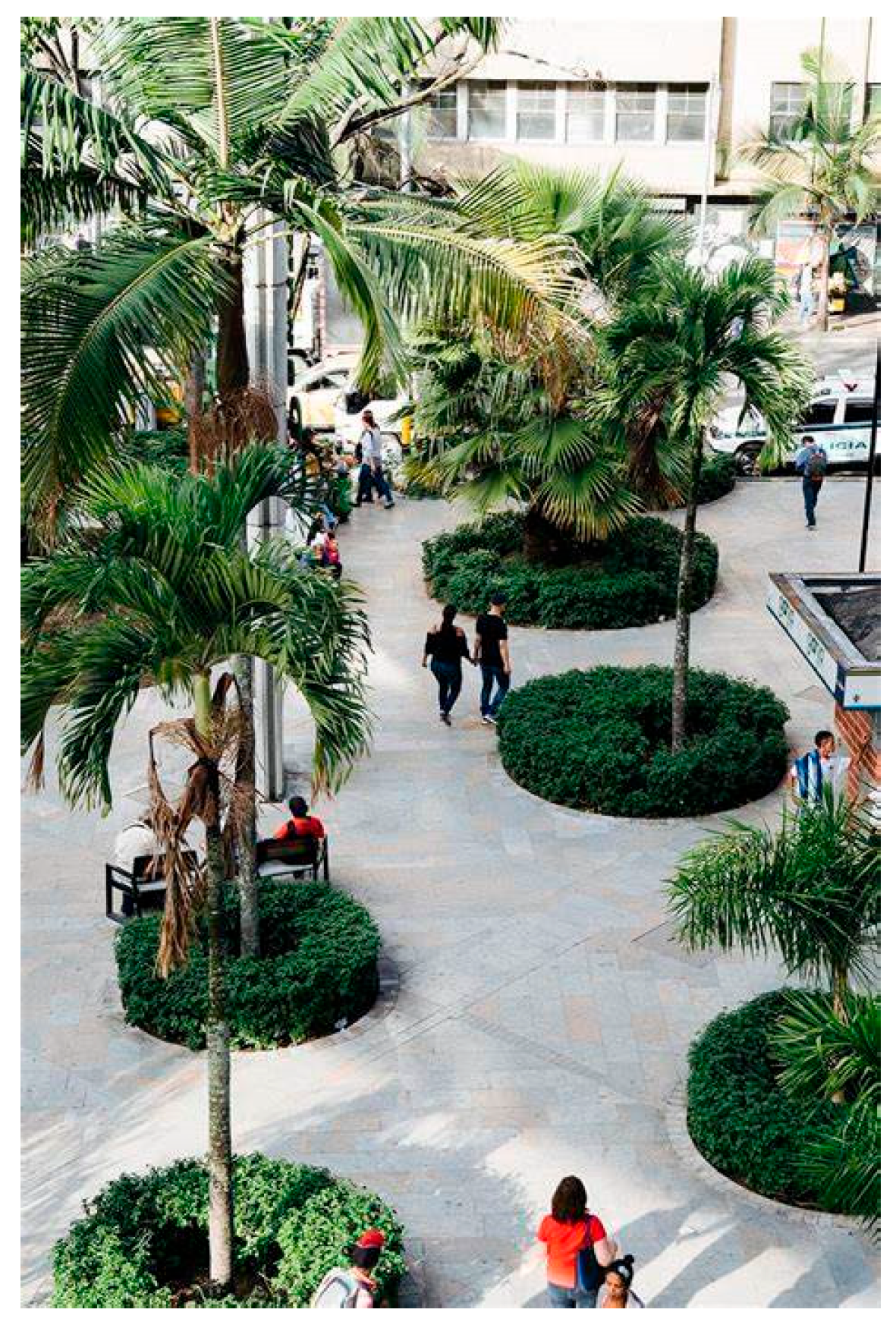

4.2. An Example of Climate Justice: The Green Revolution of Medellín

- A modern and innovative integrated public transport system, including the metro and metrocable (a network of cable cars connecting the city’s suburbs);

- An eco-sustainable approach to urban regeneration, emphasising blue and green infrastructure as structuring elements of urban design;

- Cultural promotion, through the development of cultural services such as universities, museums, schools, libraries, and cultural centres, which became new spaces for social aggregation.

- Mitigate the Urban Heat Island effect and improve air quality;

- Increase the climate resilience of the urban system;

- Promote biodiversity and ecological connectivity through the integration of green and blue infrastructure;

- Foster social inclusion and create employment opportunities for the most vulnerable population groups;

- Strengthen social capital and civic participation in the management of public spaces.

5. Third Phase: Comparison

5.1. Comparative Method and Descriptors

5.2. Comparative Analysis of the Results

- Governance: Unlike the fragmented approach of Little Haiti, Pietralata requires a binding public governance pact (between the Municipality, the University, and investors) that requires social impact assessments prior to approval.

- Housing: To prevent “studentification” or gentrification induced by the new campus, the redevelopment plan must include rent-controlled social housing within the new complexes, protecting long-term residents from market saturation.

- Environmental benefits: Following the Medellín model, the “green” component cannot simply be a landscape element for the new campus but must serve as a public ecological connector. The planned park should be designed as a network of green corridors that penetrate the existing building fabric to lower temperatures uniformly, not just within the boundaries of the Technopol.

- Community empowerment: The Technopol’s “innovation” must not remain a foreign object. A local employment clause should be introduced, giving priority to residents for facilities management and green maintenance jobs, along with digital skills training programs for local youth.

6. Conclusions and Future Developments

- Participatory Budgeting and Displacement: To what extent can binding participatory budgeting mechanisms (as evidenced in Medellín) effectively mitigate the rise in real estate values in European cities undergoing climate regeneration?

- Co-design and Long-Term Resilience: Does the early inclusion of local communities in the co-design of green infrastructure significantly increase the “appropriation” and maintenance of these spaces, preventing the alienation typical of top-down “green gentrification”?

- Regulatory Transferability: What specific anti-displacement tools (e.g., Community Land Trusts, rent caps) are legally and politically viable to accompany large tech hubs like the Pietralata Technopole, ensuring they function as inclusive public cities rather than exclusive enclaves?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ricci, L. Governare la città contemporanea—Riforme e strumenti per la rigenerazione urbana | Governing contemporary cities—Reform and measures promoting urban regeneration. Urbanistica 2017, 160, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Urban-Rural Linkages: Guiding Principles. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/urban-rural-linkages-guiding-principles (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Ricci, L.; Mariano, C.; Iacomoni, A. Nuova questione urbana e nuovo welfare—Regole, strumenti, meccanismi e risorse per una politica integrata di produzione di servizi. Ananke 2020, 90, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Urban Agenda for the EU. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/eu-regional-and-urban-development/topics/cities-and-urban-development/urban-agenda-eu_en (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Giffinger, R.; Fertner, C.; Kramar, H.; Meijers, E. Smart Cities Ranking of European Medium-Sized Cities; Centre of Regional Science: Vienna, UT, USA, 2007; Available online: http://www.smart-cities.eu/download/city_ranking_final.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- European Commission. Communication on the European Green Deal. European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/communication-european-green-deal_en (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2021/1056 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing the Just Transition Fund. Official Journal of the European Union 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/1056/oj/eng (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- European Commission. Horizon Europe (2021–2027): The Framework Programme for Research and Innovation. European Commission 2021. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/funding-tenders/find-funding/eu-funding-programmes/horizon-europe_en (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Italian Government/Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze. Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (PNRR). Available online: https://www.mef.gov.it/en/focus/The-National-Recovery-and-Resilience-Plan-NRRP/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ricci, L. Governare il cambiamento—Più Urbanistica, più Piani. In Sulla Città Futura—Verso un Progetto Ecologico; Franceschini, A., Ed.; ListLab: Trento, Italy, 2014; pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Il Diritto Alla Città; Ombre Corte: Verona, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, B. La Città dei Ricchi e la Città dei Poveri; Laterza Editore: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, J.M.; Hill, T.; Gumber, A. Climate gentrification: From theory to empiricism in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 054001. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aabb32 (accessed on 12 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chu, E.; Anguelovski, I.; Aylett, A.; Debats, D.; Goh, K.; Schenk, T.; Seto, K.C.; Dodman, D.; Roberts, D.; et al. Roadmap towards justice in urban climate adaptation research. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Edwards, G.A.; Fuller, S. Contesting climate justice in the city: The politics of urban sustainability transitions. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 25, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; Univ of Minnesota Pr: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 1989, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Wdowinski, S.; Bray, R.; Kirtman, B.P.; Wu, Z. Increasing flooding hazard in coastal communities due to rising sea level: Case study of Miami Beach, Florida. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 126, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Gustafson, M.T.; Lewis, R. Disaster on the horizon: The price effect of sea level rise. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 134, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Clerici, N.; Staudhammer, C.L.; Corzo, G.T. Socio-ecological dynamics and inequality in Bogotá and Medellín: A historic-urban ecology perspective. Urban For. Urban Green 2015, 14, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, P.; Dávila, J.D. Mobility Innovation at the Urban Margins: Medellín’s Metrocables. City 2011, 15, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor, L. Dealing with dangerous spaces: The construction of urban policy in Medellín. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2017, 44, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashden. Cooling by Nature: Medellín’s Green Corridors; 2019 Award Winner Case Study; Ashden: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://ashden.org/awards/winners/alcaldia-de-medellin/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). Medellín Shows How Nature-Based Solutions Can Keep People and Planet Cool, 2019. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/medellin-shows-how-nature-based-solutions-can-keep-people-and-planet-cool (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.; Brand, A.L. From landscapes of utopia to the margins of the green urban life: For whom is the new green city? City 2018, 22, 417–436. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13604813.2018.1473126?utm_source=researchgate.net&utm_medium=article (accessed on 5 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Cole, H.; Garcia-Lamarca, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Baró, F.; Martin, N.; Conesa, D.; Shokry, G.; Del Pulgar, C.P.; et al. Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3816. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-31572-1 (accessed on 5 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Just Transition Mechanism: Making Sure No One Is Left Behind. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal/just-transition-mechanism_en (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2020: The Value of Sustainable Urbanization. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/world-cities-report-2020-the-value-of-sustainable-urbanization (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Miami-Dade County. Miami-Dade County Sea Level Rise Strategy How Can We Gracefully, Strategically Live with Two Feet of Additional Sea Level Rise? Available online: https://miami-dade-county-sea-level-rise-strategy-draft-mdc.hub.arcgis.com/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Miami-Dade County. Resilient305 Strategy: Our Greater Miami & The Beaches. Available online: https://www.miamidade.gov/global/environment/resilience/resilient305.page (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Magic City District. The Magic of Opportunities. Available online: https://magiccitydistrict.com/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Zillow Research. Little Haiti Home Values and Real Estate Market Overview; Zillow Group: Seattle, WA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.zillow.com/home-values/127110/little-haiti-miami-fl/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Alcaldía de Medellín. Plan de Desarrollo 2016–2019: Medellín Cuenta con vos; Gaceta Oficial; Alcaldía de Medellín: Medellín, Colombia, 2016. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/irj/portal/medellin?NavigationTarget=contenido/8845-Plan-de-Desarrollo-2016---2019--Gaceta-oficial (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Alcaldía de Medellín. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente: Official Website. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/es/secretaria-medio-ambiente/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Yeung, P. How Medellín is beating the heat with green corridors. BBC Future, 22 September 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20230922-how-medellin-is-beating-the-heat-with-green-corridors (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Moloney, A. FEATURE-Colombia’s Medellin Plants ‘Green Corridors’ to Beat Rising Heat. Reuters 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/business/autos-transportation/feature-colombias-medellin-plants-green-corridors-to-beat-rising-heat-idUSL8N2OY69Q/ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Viglucci, A. Little Haiti Is Up for Grabs. Will Gentrification Trample Its People and Culture? Miami Herald 2022. Available online: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/real-estate-news/article232134932.html (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Hernandez, S. Little Haiti’s Fight to Preserve Its History and Roots. 6 South Florida 2024. Available online: https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/little-haitis-fight-to-preserve-its-history-and-roots/3454251/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Martin, A. Welcome to Miami: Speculation, Gentrification and Inundation. Equal Times 2022. Available online: https://www.equaltimes.org/welcome-to-miami-speculation?lang=en (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Soto-Estrada, E.; Correa-Echeveri, S.; Posada-Posada, M.I. Thermal analysis of urban environments in Medellin, Colombia, using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). J. Urban Environ. Eng. 2017, 11, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mourato, J.M.; de Wit, F. The geography of urban sustainability transitions: A critical review. In Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environmental and Health Research: Addressing Cross-Cutting Issues; Leal Filho, W., Guedes Vidal, D., Pimenta Dinis, M.A., Cunha Dias, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; O’Brien, K. Climate and Society: Transforming the Future; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Solecki, W.; Romero-Lankao, P.; Mehrotra, S.; Dhakal, S.; Ali Ibrahim, S. (Eds.) Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. The European Environment—State and Outlook 2020: Knowledge for Transition to a Sustainable Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/soer-2020 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Vargas-Hernandez, J.G.; Vargas-González, O.C. Urban Anthropocene-socio-ecology planning resilience. In Perspectives on Global Biodiversity Scenarios and Environmental Services in the 21st Century; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.; Poli, I.; Marino, M. Urban welfare and regeneration—Sustainability and social inclusion for achieving the SDGs. AGATHÓN|Int. J. Archit. Art Des. 2025, 17, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Shi, L.; Chu, E.; Gallagher, D.; Goh, K.; Lamb, Z.; Reeve, K.; Teicher, H. Equity impacts of urban land use planning for climate adaptation: Critical perspectives from the Global North and South. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2016, 36, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Renovation Wave for Europe—Greening our Buildings, Creating Jobs, Improving Lives. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1835 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Marino, M. Governare la Transizione. Il Piano Urbanistico Locale tra Sperimentazione e Innovazione Climate-Proof; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Marino, M. From Urban Challenges to “ClimaEquitable” Opportunities: Enhancing Resilience with Urban Welfare. Land 2023, 12, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, J.L. Societal adaptation to climate change. In The Impact of Climate Change: A Comprehensive Study of Physical, Biophysical, Social and Political Issues; Letcher, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.L.; Cohen, D.A.; Long, J.; Jurjevich, J. Urban Climate Justice: Theory, Praxis, Resistance (Geographies of Justice and Social Transformation); University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IDMC—International Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2024 Global Report on Internal Displacement. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2024/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Waters, M.C. Preparing for climate migration and integration: A policy and research agenda. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2024, 51, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM—UN Migration. World Migration Report 2022. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022 (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Lefebvre, H. La Révolution Urbaine; Librairie du Bassin: Paris, France, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Community Justice Project. Miami Workers Center. Housing Justice in the Face of Climate Change; Technical Report; Community Justice Project: Miami, FL, USA, 2020; Available online: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/catalystmiami/pages/140/attachments/original/1590720073/Housing_Justice_is_Climate_Justice_2020-compressed.pdf?1590720073 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- City of Miami. Planning Department: Official Website. Available online: https://www.miami.gov/My-Government/Departments/Planning (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- UN-Habit. Annual Report 2010. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/annual-report-2010 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Alcadia de Medellin. Plan de Desarrollo 2004–2007. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/irj/portal/medellin?NavigationTarget=contenido/8841-Material-de-Consulta:-Plan-de-Desarrollo--2004---2007 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- BBC News. Colombia’s Medellin Named ‘Most Innovative City’. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-21638308 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Alcadia de Medellin. Medellín, Ejemplo de Urbanismo Social y Arquitectura Escolar: 90 Delegados Internacionales Visitaron la Ciudad. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/es/sala-de-prensa/noticias/medellin-ejemplo-de-urbanismo-social-y-arquitectura-escolar-90-delegados-internacionales-visitaron-la-ciudad/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- DepoBeta. Review of Green Corridor Medelline as a Nature Based Solution (NBS) Infrastructure. Available online: https://depobeta.com/magazine/artikel/review-of-green-corridor-medelline-NBS/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Instituto de Estudios Urbanos. Available online: https://ieu.unal.edu.co (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Przeworski, A.; Teune, H. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Landman, T. Issues and Methods in Comparative Politics: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lijphart, A. Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1971, 65, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Su, Q.; Chen, Y.S. Establish an assessment framework for risk and investment under climate change from the perspective of climate justice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 66435–66447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.; Mariano, C.; Marino, M. Public City as Network of Networks: A Toolkit for Healthy Neighbourhoods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IISD—International Institute for Sustainable Development. Social Impact Assessment (SIA). Available online: https://www.iisd.org/learning/eia/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/SIA.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Vanclay, F. International Principles for Social Impact Assessment. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal 2003, 21, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. Aggiornamento Indicatori Bes—Aprile 2025. Available online: https://www.istat.it/notizia/aggiornamento-indicatori-benessere-equo-e-sostenibile/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| Key Concept | Definition and Conceptual Distinction | Theoretical Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Public City | Defined not merely as state-owned property, but as the structural network of public spaces, essential services (mobility, health, education), and welfare infrastructures that guarantee the universal right to the city. It acts as the primary physical platform for social cohesion. | Ricci (2020); Lefebvre (1968) [3,12] |

| Urban welfare | A spatial reinterpretation of the traditional Welfare State that shifts focus from purely economic assistance to the equitable distribution of spatial opportunities. It views the city’s physical infrastructure (public spaces, mobility, housing, ecosystem services) as the primary provider of social security and rights, ensuring that high-quality urban environments are accessible to all citizens regardless of income. | Ricci et al. (2020); Secchi (2013) [3,13] |

| Climate Gentrification | Distinct from ordinary gentrification (driven by the rent gap in undervalued areas), this phenomenon is triggered by the “resilience gap”. It occurs when capital flows into areas with lower climate risk (e.g., higher elevation) or newly implemented green infrastructure, displacing lower-income residents due to the “safety premium” on property values. | Keenan et al. (2018); Shi et al. (2016) [14,15] |

| Climate Justice | Climate Justice is the normative goal: fair distribution of environmental benefits and burdens. | Schlosberg (2007) [16] |

| Equitable Adaptation | Equitable Adaptation is the operational process: the specific planning tools (e.g., anti-displacement protocols, participatory design) used to achieve that goal and prevent maladaptation. | Bulkeley et al. (2014) [17] |

| Spatial Justice | The fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to use them. In this paper, it implies that access to climate resilience (e.g., cool islands, flood protection) must not depend on a neighborhood’s socioeconomic status. | Soja (2010) [18] |

| Most Vulnerable Groups | Identified through an intersectional approach: populations characterized not only by low income but by limited adaptive capacity due to overlapping factors (housing informality, age, ethnicity, health status) that make them disproportionately sensitive to climate shocks. | IPCC (2023); Crenshaw (1989) [19,20] |

| Research Phase | Document Typology | Quantity | Description and Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Theoretical Framework & Context | Academic Literature | 25 | Peer-reviewed articles and books defining the theoretical paradigms of urban welfare, climate justice, and gentrification. Examples: Ricci et al. (2020) [3]; Schlosberg (2007) [16]; Soja (2010) [18]; Keenan et al. (2018) [14]; Anguelovski et al. (2018, 2022) [27,28]; Crenshaw (1989) [20]. |

| Policy Reports & Guidelines | 12 | Official documents from international bodies and EU frameworks. Examples: European Green Deal (2019) [6]; Just Transition Mechanism [30]; IPCC Synthesis Report (2023) [19]; UN-Habitat World Cities Report (2020) [31]; EU Horizon Europe Framework (2021) [8]. | |

| Phase 2: Case Study Analysis (Miami & Medellín) | Local Planning & Technical Documents | 11 | Official masterplans, government strategies, and technical datasets. Miami: Miami-Dade Sea Level Rise Strategy [32]; Resilient305 Strategy [33]; Magic City Innovation District Master Plan [34]; Zillow Real Estate Market Overview [35],; Medellín: Plan de Desarrollo 2016–2019 [36]; Secretaría de Medio Ambiente Indicators [37]; UNEP “Cooling by Nature” Report [27]; Ashden Award Case Study [26]. |

| Investigative Media & News Reports | 6 | Major media analysis tracking real-time gentrification and project outcomes. Examples: BBC Future (Yeung, 2023) [38]; Reuters (Moloney, 2021) [39]; Miami Herald (Viglucci, 2022) [40]; NBC 6 South Florida (Hernandez, 2024) [41]; Equal Times (Martin, 2022) [42]. | |

| Methodological references | 4 | Specific quantitative and qualitative academic studies applied to the analyzed cities. Examples: Wdowinski et al. (2016) on flooding hazards in Miami [21]; Soto-Estrada et al. (2017) on thermal analysis in Medellín [43]; Escobedo et al. (2015) on socio-ecological dynamics [23]; Bernstein et al. (2019) on sea-level rise price effects [22]. | |

| Total | 58 |

| Descriptors | Qualitative Assessment Criteria (What Was Evaluated?) | Key Analytical Dimensions (Indicators Looked for in Documents) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Strategic vision and governance | Assessment of the governance model and its orientation towards public interest versus private profit. | Public vs. Private Logic: Is the intervention driven by market speculation or public welfare? Regulation: Presence/Absence of binding protocols for social inclusion. Coordination: Level of inter-institutional cooperation described in plans. |

| 2. Housing accessibility and mobility | Evaluation of the project’s impact on housing stability and connectivity for original residents. | Protection Mechanisms: Presence of policies to prevent displacement (e.g., affordable housing requirements). Market Pressure: Evidence of speculative trends or “climate gentrification” risks in reports. Connectivity: Integration with public transport networks serving vulnerable areas. |

| 3. Distributive environmental benefits | Analysis of who physically accesses and benefits from the environmental improvements. | Access Rights: Are the green/blue infrastructures public and open, or privatized/gated? Geographic Coverage: Do interventions target marginalized neighborhoods or only high-income zones? Nature of Intervention: Focus on luxury landscaping vs. functional ecosystem services (e.g., cooling). |

| 4. Job creation and community empowerment | Assessment of the economic fallout on the local community. | Target Beneficiaries: Are new jobs accessible to current residents or do they require external skilled labor? Training: Existence of professional training programs funded by the project Participation: Degree of community involvement in the management of spaces. |

| 5. Preservation of cultural and social identity | Evaluation of the compatibility between the new project and the existing cultural fabric. | Cultural Continuity: Does the project integrate local traditions/activities or replace them? Heritage Sensitivity: Recognition of the area’s symbolic value in planning documents. Social Mix: Maintenance of the existing demographic diversity. |

| Descriptors | Case study: Magic City Innovation District | Critical Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regressive Interventions | Progressive Interventions | ||

| Strategic vision and governance | Planning is fragmented and developer-led. The absence of mandatory Inclusionary Zoning or binding Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) allowed the Special Area Plan to prioritize real estate volume over social resilience. | ✓ | |

| Housing accessibility and mobility | The “Elevation Hypothesis” drives demand: property values rise due to climate safety. Lack of rent control policies or property tax freezes for long-term low-income owners facilitates rapid displacement by wealthier climate migrants. | ✓ | |

| Distributive environmental benefits | Environmental upgrades (drainage, greening) are privatized within the project boundaries. There is no municipal mechanism to redistribute the “resilience dividend” to the surrounding existing fabric. | ✓ | |

| Job creation and community empowerment | Skill mismatch: new jobs are in high-tech/innovation sectors. Absence of funded workforce development programs for local residents leads to economic exclusion despite job creation. | ✓ | |

| Preservation of cultural and social identity | Zoning changes from industrial/residential to mixed-use commercial encourage the replacement of culturally specific local businesses (botanicas, Caribbean markets) with generic globalized retail. | ✓ | |

| Descriptors | Case Study: Medellin | Critical Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regressive Interventions | Regressive Interventions | ||

| Strategic vision and governance | Public-led governance: The project is funded by public utility revenues (EPM) and anchored in the Plan de Desarrollo, ensuring that climate goals align with the “Social Urbanism” policy of prioritizing vulnerable areas. | ✓ | |

| Housing accessibility and mobility | Anti-displacement strategy: Investments focused on public space rather than private housing stock. Integration with the Metrocable system improved accessibility without triggering immediate mass eviction dynamics. | ✓ | |

| Distributive environmental benefits | Universal Design: The green corridors are public infrastructures (streets, sidewalks) accessible to all, ensuring the cooling effect (−2 °C) benefits pedestrians and residents regardless of income. Empirical data (temperature reduction of 2–3.5 °C, 25% increase in vegetation coverage) confirm an equitable distribution of climate benefits. | ✓ | |

| Job creation and community empowerment | “Jardineros” Program: The municipality directly hired and trained 700 vulnerable residents as “expert gardeners,” transforming maintenance costs into social investment and community ownership. | ✓ | |

| Preservation of cultural and social identity | Reclaiming public space: The design incorporated local knowledge and prioritized pedestrian life, strengthening the “Right to the City” and reinforcing community bonds in historically violent neighborhoods. The enhancement of quebradas and public spaces as cohesion hubs has preserved territorial memory and the sense of collective belonging. | ✓ | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ricci, L.; Mariano, C.; Marino, M. Rethinking Cities Beyond Climate Neutrality: Justice and Inclusion to Prevent Climate Gentrification. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010259

Ricci L, Mariano C, Marino M. Rethinking Cities Beyond Climate Neutrality: Justice and Inclusion to Prevent Climate Gentrification. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010259

Chicago/Turabian StyleRicci, Laura, Carmela Mariano, and Marsia Marino. 2026. "Rethinking Cities Beyond Climate Neutrality: Justice and Inclusion to Prevent Climate Gentrification" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010259

APA StyleRicci, L., Mariano, C., & Marino, M. (2026). Rethinking Cities Beyond Climate Neutrality: Justice and Inclusion to Prevent Climate Gentrification. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010259