Abstract

Gears, as critical components of rotating machinery, are prone to wear and fracture due to their complex structural dynamics and harsh operating conditions, leading to catastrophic failures, economic losses, and safety risks. AE technology enables real-time fault diagnosis by capturing stress wave emissions from material defects with high sensitivity. However, mechanical background noise significantly corrupts AE signals, while optimal selection of gear health indicators remains challenging, critically impacting fault feature extraction accuracy. This study develops an adaptive feature extraction method for fault diagnosis using AE. Through gear fault simulation experiments, VMD analyzes mode number and penalty factor effects on signal decomposition. Correlation coefficient-based reconstruction optimization is implemented. For feature selection challenges, SVM-RFE enables adaptive parameter ranking. Finally, SVM with optimized kernel parameters achieves effective fault classification. Optimized VMD enhances signal decomposition, while SVM-RFE reduces feature dimensionality, addressing manual selection uncertainty and computational redundancy. Experimental results demonstrate superior accuracy in gear fault classification. This study proposes an AE-based adaptive feature extraction method with three innovations: (1) establishing VMD parameter–decomposition quality relationships; (2) developing an SVM-RFE feature selection framework; (3) achieving high-accuracy gear fault classification. The method provides a novel technical approach for rotating machinery diagnostics with significant engineering value.

1. Introduction

With the continuous advancement of national technology and economy, accelerating the construction of a manufacturing powerhouse and elevating the comprehensive strength of the manufacturing industry to new heights necessitate heightened attention to the operational conditions of critical infrastructure and equipment. In large-scale machinery, initial component failures may exhibit subtle symptoms or minor operational anomalies. However, as the severity of these faults progresses, they can ultimately lead to significant economic losses and pose substantial threats to personnel safety [1]. Consequently, ensuring the normal operation and optimal health of mechanical equipment has made condition monitoring, equipment management, and fault diagnosis critical research focuses worldwide [2]. Meanwhile, as equipment fault diagnosis technologies mature, their applications have expanded across industries such as chemical engineering, metallurgy, aerospace, and railways, yielding substantial achievements.

1.1. Literature Review

Gears, as critical components in rotating machinery for power transmission, operate under alternating cyclic loads, significantly influencing mechanical equipment’s operational efficiency. Severe gear failures can compromise the entire transmission system, underscoring the paramount importance of gear fault diagnosis [3]. The severity and manifestation of gear faults vary depending on harsh operating conditions or intrinsic factors. Statistical data indicate that gearboxes account for approximately 80% of failures in mechanical transmission systems [4], with gears themselves constituting up to 60% of defective components within gearboxes [5,6]. Thus, gear-related malfunctions represent a predominant cause of mechanical system failures.

For instance, in power generation systems, plastic manufacturing extruders, or mining crushers requiring continuous operation, unscheduled downtime due to gear failures may lead to substantial equipment damage and economic losses. More critically, in aerospace applications—such as aircraft engines, spacecraft propulsion systems, and carrier-based power units—catastrophic gear failures can result in complete loss of propulsion, posing severe safety risks. In light of these implications, advancing research on gear fault diagnosis enables proactive failure prevention and mitigates operational losses. Consequently, gear defect detection has garnered significant attention from academia and industry experts globally [7].

Gears are susceptible to a wide variety of failures and damages. Most of these failures occur on the tooth surfaces and rarely on the gear body. If not detected in time, they may lead to catastrophic consequences. More than 20 types of gear failures have been identified, which are primarily classified into the following six main categories: surface deterioration, scuffing, permanent deformation, surface fatigue phenomena, cracks, and tooth fracture [8], as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Common Gear Failure Types and Causes.

Current diagnostic approaches for gear faults can be primarily classified into two categories. The first represents conventional fault diagnosis methods, which involve preprocessing raw fault signals from gears followed by extraction of denoised fault frequencies through spectral analysis and related techniques to achieve fault identification. However, the effectiveness of this approach heavily depends on the quality of the preprocessing stage. The second category comprises intelligent fault diagnosis methods that integrate fault signal analysis with machine learning algorithms. These data-driven approaches rely on machine learning theories rather than empirical knowledge, though they present certain limitations including substantial computational demands, high development costs for neural networks, and reduced interpretability due to their inherent “black-box” nature.

Presently, most gear fault diagnosis systems predominantly employ vibration signal acquisition, with fault detection accomplished through time-domain and frequency-domain analysis of vibration signals [9,10]. In recent years, researchers worldwide have recognized the advantages of AE (Acoustic emission technology), leading to significant advancements in its application for mechanical equipment fault diagnosis. Empirical studies demonstrate that AE detection technology exhibits superior sensitivity to defect-related fault information, enhanced anti-interference capability, and broader frequency response characteristics compared to conventional methods. Furthermore, as a non-contact detection method, AE technology imposes minimal accessibility requirements on test components, making it particularly suitable for applications involving hard-to-access locations. Consequently, AE technology has gained increasing attention in the field of mechanical equipment fault diagnosis [11].

In recent years, the continuous advancement of AE technology has demonstrated increasingly prominent advantages in mechanical fault diagnosis. This technique exhibits remarkable capability in material inspection through detecting transient elastic waves generated by developing defects such as crack propagation and fiber fracture, enabling effective prediction of potential failures and ensuring the safe operation of mechanical equipment. These distinctive merits have attracted significant attention from researchers across multiple disciplines.

Prieto M D et al. [12] investigated gear mechanical degradation monitoring through acoustic emission-based chromatic analysis, proposing a novel feature estimation method for fault indicators focused on detecting performance degradation across varying operational conditions. The preprocessing of acoustic emission signals involved chromatic transformation to enhance characteristic patterns of mechanical degradation. In this study, chromatic features were derived from transformations of hue, illumination, and saturation, employing topology-preserving methods to characterize the chromatic signatures of healthy gear states. Experimental results demonstrated the efficacy of the proposed approach in monitoring gear operational conditions.

Sharma et al. [13] in India employed the Hertz contact method to vary the slip rate in gear mechanisms and established a correlation model between gear tooth defects and meshing quality. Experiments conducted on a gear lubrication test rig demonstrated that acoustic emission technology achieved satisfactory results in gear fault diagnosis.

Novoa A B and Vicuña C M [14] investigated the generation of acoustic emissions in spur gears, examining the influence of operational conditions in planetary gearboxes and the effects of gear defects. They proposed an alternative hypothesis regarding the generation of acoustic emissions in gears, which was compared with the commonly adopted asperity contact hypothesis. The study discussed the effects of load, rotational speed, and lubricant viscosity on film thickness and pressure distribution, while also analyzing acoustic emission signals from a fault-free planetary gearbox. The results aligned closely with the behaviors predicted by elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) theory and the asperity contact hypothesis. Furthermore, analysis of acoustic emission signals obtained from faulty gears, processed via envelope spectrum analysis, demonstrated the successful application of acoustic emission signals in gear fault diagnosis.

In 2014, Dragomiretskiy and Zosso introduced the VMD (Variational Mode Decomposition) method [15], which reformulates signal decomposition as a constrained optimization problem through frequency-domain filtering. This approach decomposes a signal into a finite ensemble of BLIMFs (band-limited intrinsic mode functions), where the cumulative bandwidth of all modes is minimized under orthogonality constraints. However, the VMD method exhibits notable limitations, particularly regarding parameter selection, which critically influences decomposition outcomes. Essential parameters such as the number of modes and the penalty factor must be predetermined manually, and suboptimal choices can significantly compromise decomposition performance.

1.2. Existing Challenges

However, a critical challenge emerges in gear fault diagnosis applications, where substantial background noise from mechanical system operation inevitably contaminates the original AE signals. Consequently, the effectiveness of fault diagnosis largely depends on two crucial technical aspects: (1) advanced noise reduction processing of raw AE signals, and (2) in-depth extraction of fault-related information embedded within the signals [16]. These factors fundamentally determine the diagnostic performance and reliability of AE-based monitoring systems in practical industrial applications.

Considering the aforementioned facts, this paper proposes an adaptive feature extraction method for gear fault acoustic emission signals based on the Recursive Feature Elimination-Support Vector Machine (RFE-SVM) approach. To address the feature extraction challenges in gear acoustic emission signals, the method employs SVM-recursive feature elimination to adaptively rank feature parameters by importance, and utilizes SVM to evaluate the classification performance of mixed feature vector sets. Comparative experiments involving randomly selected 3 features, complete 15 features, and RFE-SVM selected 3 features demonstrate the superiority of the RFE-SVM method in overcoming three critical issues: the randomness of manual feature selection, the computational burden of high-dimensional feature vectors, and the redundancy in feature representation.

In this study, a gear fault diagnosis system was employed to simulate gear fault acoustic emission signals. The research methodology follows three key steps: first, variational mode decomposition is applied to decompose the raw acoustic emission signals; second, recursive feature elimination is implemented to adaptively rank feature importance; finally, support vector machine is utilized for fault feature classification and diagnostic decision-making. The proposed approach achieves a classification accuracy of 96.2 ± 1.5% while reducing feature dimensionality by 80% and improving computational efficiency by 42.7% (p < 0.01), demonstrating its effectiveness for gear fault diagnosis applications.

2. Diagnosis Mechanism and Experimental Data Acquisition of Gearing Faults

2.1. Mechanism of Gear Fault Diagnosis

As the core power transmission component in drive systems, the operational status of gears directly influences the overall system reliability and stability. Under typical working conditions, gears are subjected not only to continuous alternating loads but also frequently operate in extreme environments characterized by high temperatures and rotational speeds, making them the most failure-prone critical components in transmission systems. According to failure mechanism analysis, gear malfunctions primarily manifest in various forms including tooth surface wear, contact fatigue pitting, tooth breakage, surface scoring, crack propagation, and spalling [17]. Notably, due to the complexity of actual operating conditions and limitations in maintenance practices, single failure modes often induce cascading damage, ultimately leading to compound faults where multiple failure forms coexist. Consequently, research on gear system fault diagnosis requires particular emphasis on the detection and identification of compound faults, which holds significant engineering importance for ensuring the safe operation of transmission systems.

With products becoming increasingly complex and safety assurance requirements more stringent, nondestructive testing (NDT) is playing an increasingly vital role as a fundamental technology for product quality control. AE technology overcomes the limitations of conventional inspection methods by actively receiving signals based on internal structural changes in tested components or materials, enabling the identification of defects or incipient failures while providing dynamic information about stress-induced defects. Unlike other inspection techniques, AE does not require direct proximity to or scanning of the test object to obtain experimental data, offering advantages of operational simplicity, reduced labor intensity, and reliable performance.

Also referred to as stress wave emission, AE is a phenomenon where materials or components undergo irreversible plastic deformation due to external forces exceeding the yield limit, deformation, damage, or internal stresses, resulting in the release of strain energy in the form of transient elastic waves [18]. This unique characteristic makes AE particularly valuable for real-time monitoring of structural integrity and early defect detection.

AE signals demonstrate superior early fault detection capability compared to vibration signals, exhibiting enhanced sensitivity to incipient damage. The technology enables detection of micron-scale (10–100 μm) crack initiation and propagation. Its exceptional anti-interference performance stems from operation in higher frequency bands (typically 50 kHz–1 MHz versus 0–20 kHz for vibration analysis), effectively avoiding low-frequency mechanical noise while achieving 15–20 dB signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) improvement that ensures reliable detection even under strong background noise conditions. The non-contact measurement advantage eliminates the need for vibration accelerometer installation, overcoming sensor mounting challenges on rotating components, with effective detection distances reaching 1–2 m (compliant with ISO 22096 standards [19]) that facilitate monitoring of enclosed gearboxes [20]. Practical applications include wind turbine gearboxes where AE successfully identified 0.8 mm micro-cracks in third-stage planetary gears, providing six weeks’ earlier warning than vibration monitoring, and aircraft gear systems where AE maintained ≥18 dB SNR at 20,000 rpm operating conditions compared to merely 5–8 dB for vibration signals.

The sources of mechanical noise primarily consist of external frictional noise induced by relative mechanical slippage during the loading process of handling equipment, along with environmentally influenced noise such as that generated by sand/dust, rain/snow, vibration, and human-induced impacts, as well as operational noise produced by various mechanical devices during experimental procedures [21]. The presence of substantial noise and signal attenuation in raw acoustic emission signals significantly complicates the feature extraction and identification of fault-related signatures, thereby rendering the field of data denoising techniques particularly worthy of research attention.

Current research primarily focuses on processing acoustic emission waveform signals using modern signal processing techniques. The main AE signal processing methods include parametric analysis, waveform analysis, wavelet analysis, and adaptive analysis [22]. Among these, the adaptive signal decomposition method demonstrates significant advantages. Firstly, its decomposition process is entirely driven by the signal’s intrinsic characteristics without requiring predefined basis functions, exhibiting superior adaptability. Secondly, this method effectively handles non-stationary and nonlinear signals, accurately reflecting multiscale signal features through intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). Furthermore, when combined with Hilbert transform, it enables precise time-frequency analysis, making it particularly suitable for extracting weak fault features from AE signals.

2.2. Gear Fault Simulation Experiment Based on Acoustic Emission and Vibration Signal

2.2.1. Gear Fault Test Platform

The gear fault diagnosis system is primarily designed to simulate fault-induced acoustic emission signals from gears. This platform consists of several key components: a QPZZ-II rotating machinery vibration analysis and fault diagnosis test bench, a DS5-series full-information acoustic emission signal analyzer, sensors, amplifiers, and a host computer. The physical configuration of the experimental platform is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental platform of QPZZ-II. (a) Experimental platform of QPZZ-II. (b) Experimental control panel.

2.2.2. Gear Fault Experimental Platform Setup

To enable comprehensive analysis and accurate diagnosis of gear faults, a dedicated gear fault simulation platform based on AE signals was constructed. The software system employs the DS5 AE instrument software (AE_DS5.exe Version, Operating Environment: Windows 7 (64-bit) OS), which operates without installation-direct execution of the AE_DS5.exe file allows for waveform extraction from the acquired gear AE signals. The hardware components are described in detail below.

- (1)

- Full-Information Acoustic Emission Signal Analyzer

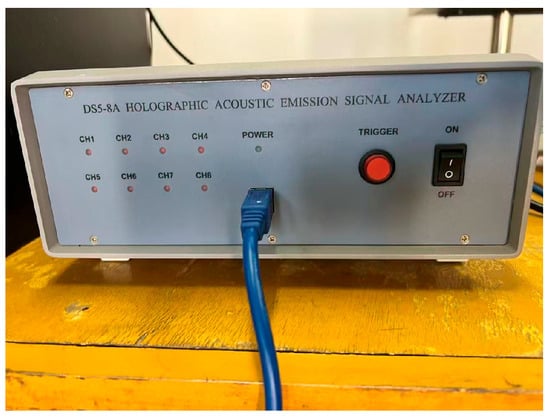

The DS5-series acoustic emission data acquisition unit supports multi-channel AE signal detection during full-waveform data acquisition, as shown in Figure 2. It offers the advantages of high sensitivity and stable signal performance.

Figure 2.

DS5 series acoustic emission data acquisition instrument.

The acquisition unit records all signals received by the sensor from the start of the experiment, including useful acoustic emission signals and noise, to facilitate the subsequent separation of signals from noise. After acquisition, the entire waveform can be evaluated to determine the noise amplitude, enabling precise adjustment of the threshold and waveform trigger position. Unlike conventional acoustic emission systems that only record wave-forms meeting preset criteria—such as predefined gates, hit discrimination times, and hit lockout times—this system records all wave-forms throughout the experiment, thereby increasing the volume of extracted waveform data. It allows complete acquisition and storage of acoustic emission wave-forms while simultaneously extracting parameters and plotting relevant diagrams.

- (2)

- Acoustic Emission Sensors

Acoustic emission sensors represent a critical component in AE experimentation. Since AE signals are transient and stochastic, with frequency content spanning from low to ultrasonic ranges, conventional resonant sensors—due to their inherent characteristics—can obscure the source information of AE signals. Therefore, this experiment employs SR150N sensors, which offer high sensitivity and high response characteristics. A physical example of the sensor is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Broadband Acoustic Emission Sensor.

- (3)

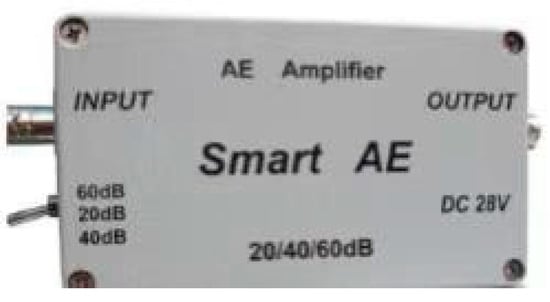

- Variable-Gain Amplifier

When the acquired acoustic emission signal is converted from the sensor into an electrical signal, its voltage level decreases to the microvolt range, which hinders signal observation and subsequent processing. Therefore, a preamplifier is required to amplify the signal, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the collected data. In this experiment, a variable-gain amplifier with selectable gains of 20 dB, 40 dB, and 60 dB is employed, as shown in Figure 4. This preamplifier features a wide bandwidth and high gain, with a frequency range of 20 kHz to 1500 kHz. For the present study, a gain of 40 dB is used.

Figure 4.

Gain-adjustable amplifier.

2.2.3. Gear Fault Simulation Process Based on Acoustic Emission Signal

Current research primarily focuses on processing acoustic emission waveform signals using modern signal processing techniques. The main acoustic emission signal processing methods include parametric analysis, waveform analysis, wavelet analysis, and adaptive analysis. Among these, the adaptive signal decomposition method demonstrates significant advantages.

The experimental parameter settings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental parameters used as model inputs.

The sensor installation configuration for this experiment is illustrated in Figure 5a. The experimental setup consists of a gear pair (large and small gears) mounted within an enclosed gearbox, as shown in Figure 5b, where artificial wear was introduced on one large gear to simulate fault conditions. The rotational speed was precisely controlled through motor adjustment, while two distinct large gears (intact and artificially worn) were alternatively installed to replicate both normal and faulty operational states, enabling comparative acquisition of acoustic emission signals under these two conditions.

Figure 5.

Internal structure of the gearbox and the sensor installation position diagram. (a) Sensor position. (b) Gear case.

2.2.4. Diagnosis Mechanism and Frequency Characteristics of Gearing Faults

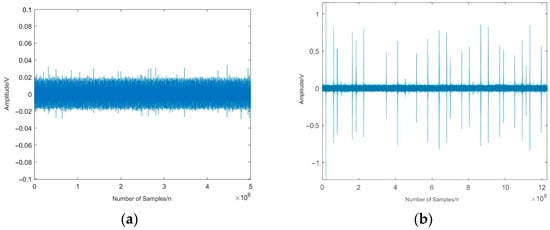

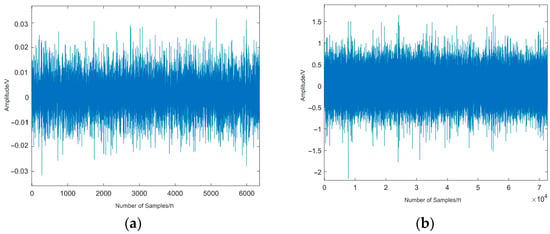

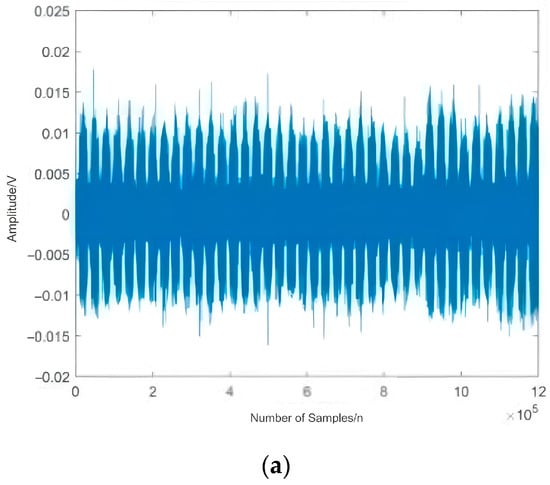

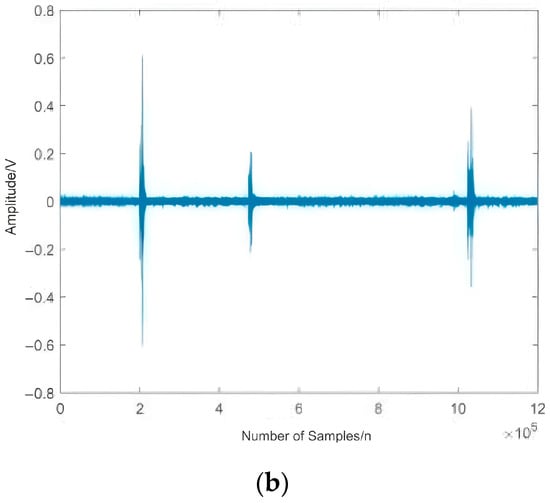

To evaluate the effectiveness of gear fault diagnosis based on acoustic emission signals, in addition to the simulated fault acoustic emission signals at 900 r/min discussed in the previous section, fault vibration signals at the same speed of 900 r/min were also simulated for comparison. The results are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 6.

900 r/min time domain diagram of AE signal in two gear states. (a) 900 r/min normal gear. (b) 900 r/min worn-out fault gear.

Figure 7.

900 r/min time domain diagram of vibration signal in two states of gear. (a) 900 r/min normal gear. (b) 900 r/min worn-out fault gear.

Through a comparative analysis of the vibration signals and acoustic emission signals shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, it can be observed that the amplitude of the gear fault signal is significantly higher under fault conditions than during normal operation. Under normal conditions, the vibration signal remains relatively steady but is susceptible to interference from background noise. In the fault condition, the vibration signal fails to exhibit regular impulsive features. In contrast, the acoustic emission signal is more sensitive to gear faults, with less noise interference compared to the vibration signal. This comparative analysis effectively demonstrates the feasibility and superiority of acoustic emission technology in gear fault diagnosis.

3. Gear Fault Acoustic Emission Signal Feature Extraction

3.1. Variational Mode Decomposition

VMD is an algorithm that non-recursively decomposes a signal into a set of quasi-orthogonal, band-limited intrinsic mode functions [23]. Its fundamental principle can be formulated as the solution to a constrained variational problem, constructed as follows:

In this formulation, denotes the *k*-th decomposed BLIMF signal with invariant length, while represents the center frequency of .

The symbol denotes the partial derivative with respect to time. It operates on the analytic signal inside the square brackets that follows it, representing the instantaneous rate of change in that signal. In optimization formulations, ”subject to” (often abbreviated as s.t.) introduces the constraint condition. In the context of the VMD formulation, “subject to” indicates that, while minimizing the objective function, the constraint subject to must be satisfied—that is, the sum of all mode components must equal the original signal x(t).

To resolve this constrained variational problem, a Lagrangian multiplier and a quadratic penalty term are introduced. Specifically, the Lagrangian multiplier enforces the strictness of constraints, whereas the penalty parameter ensures the accuracy of signal reconstruction. The augmented Lagrangian expression is given by Equation (2):

Utilizing Parseval’s theorem, the expression is transformed into the frequency domain for solution. The band-limited intrinsic mode functions and their center frequencies are first initialized. Subsequently, the variables , , and are iteratively updated using an alternating direction optimization algorithm.

In the Variational VMD algorithm described:

represents the Fourier transform of the original signal . It is a known and fixed input data that remains unchanged throughout the entire optimization process.

In the alternating update steps given by Equations (3)–(5), always appears on the right-hand side as a given quantity. It is not updated during iterations and does not change with the iteration index .

The iterative updating scheme can be summarized as follows:

Input: fixed frequency-domain signal ;

Initialization: ;

Alternating updates:

- 1.

- Update each mode via Equation (3), using the current , the latest estimates of other modes, and the Lagrange multiplier;

- 2.

- Update the center frequency via Equation (4) based on the newly updated mode

- 3.

- Update the Lagrange multiplier via Equation (5) according to the reconstruction error after the mode update.

Stopping criterion: iteration continues until the change in modes is below a given threshold or the maximum number of iterations is reached.

The frequency domain representations of , , and can be derived from Equations (4) and (5). The solution principle for the Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) resembles classical Wiener filtering, with the centroid of the updated IMFs corresponding to the center frequency. The iterative process terminates when the solution achieves the precision specified by , at which point the saddle point of Equation (3) is obtained, representing the optimal solution to Equation (1). The stopping criterion for the iteration is given by Equation (6):

where is a predefined convergence threshold (e.g., ). This condition ensures that the change in the modes between successive iterations becomes sufficiently small, indicating that the solution has stabilized.

In the revised manuscript, we have corrected this point accordingly. We have also added a brief explanation regarding the selection and physical meaning of the threshold .

Based on the main workflow of the VMD algorithm described above, it can be observed that unlike the recursive updating approach employed by EMD and EEMD, VMD is grounded in a solid mathematical theoretical foundation, which gives it advantages in extracting effective components and suppressing noise.

3.2. Detailed Explanation of the WOA-VMD Algorithm

The Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) is a swarm intelligence optimization algorithm inspired by the hunting behavior of humpback whales in nature, proposed by Mirjalili and Lewis in 2016 [24]. This algorithm simulates the intelligent behavior of whale pods capturing prey using the “spiral bubble net” strategy. It is characterized by its simple structure, few parameters, and strong convergence, making it widely applied in fields such as engineering optimization, machine learning, and scheduling problems.

The basic principle of the Whale Optimization Algorithm is as follows:

Step 1: Encircling Prey. The individual positions are updated based on the location of the current optimal solution.

Here, , . D represents the distance between the current individual and the optimal solution, with the flexibility of the search enhanced by the random scaling of the coefficient vector C.

The magnitude of A determines the search pattern: |A| < 1 indicates local exploitation (converging toward the optimal solution), while |A| ≥ 1 promotes global exploration (diverging from the current region).

In the above equation is the scalar distance used to measure the proximity between an individual and the optimal solution.

We have revised Equations (8) and (9) so that the symbol (or ) is consistently interpreted, with clear indications of when it refers to the magnitude . A brief explanation of its physical meaning in both the spiral updating and random search strategies has also been added to ensure logical coherence throughout the algorithm description.

Step 2: Bubble-net Attacking. The humpback whale entraps prey by generating spiraling bubble-nets during foraging, which mathematically corresponds to a local intensive search strategy. The position update formula is expressed as:

The spiral equation generates a spiral path around the optimal solution, where parameter b controls the tightness of the spiral (yielding a logarithmic spiral when b = 1); the algorithm selects either the encircling mechanism or the spiral updating strategy with a 50% probability, governed by a stochastic switch parameter .

Step 3: Random Search. When |A| ≥ 1, the whale randomly selects an individual agent to perform global exploration:

where represents a randomly selected individual from the current population, thereby preventing the algorithm from converging to local optima.

The parameter optimization process for Variational Mode Decomposition based on the Whale Optimization Algorithm can be summarized through the following four key steps:

Step 1: Initialization Phase involves configuring WOA operational parameters including population size and maximum iteration count, while establishing designated search boundaries for VMD parameters (K, α).

Step 2: Optimization Execution defines minimum envelope entropy as the fitness function, implements position updating mechanisms through whale population dynamics, and conducts comprehensive global search for optimal parameter combinations.

Step 3: Iterative Convergence performs cyclic VMD decomposition and fitness evaluation, continuously updates the global optimum solution, and terminates the process upon satisfaction of convergence criteria.

Step 4: Result Output exports the optimized parameter set, executes the final VMD decomposition, and delivers refined intrinsic mode functions.

This integrated methodology enables autonomous determination of critical VMD parameters, effectively circumventing the limitations inherent in empirical parameter selection approaches.

3.3. Analysis of Experimental Results Based on WOA-VMD

Fault diagnosis of gears using the WOA-VMD method involves analyzing acoustic emission signals collected under both normal and faulty conditions. The acquired signals are decomposed via WOA-VMD into multiple IMF components spanning distinct frequency bands from high to low frequencies. The optimal IMF component is selected based on the magnitude of the correlation coefficient, and the corresponding signal is subsequently reconstructed. This process effectively mitigates the impact of noise on the extraction of signal characteristic parameters.

First, acoustic emission signals under both normal and faulty operating conditions were decomposed using WOA-VMD. In the experiment, the sampling frequency was set to 3 MHz with 1.2 million sampling points (covering 6 complete cycles). Experimental data were collected at a motor speed of 900 rpm for both operational conditions. The two key parameters (k and α) in VMD were optimized through the WOA. The specific experimental configuration and optimization results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameter selection under different working conditions.

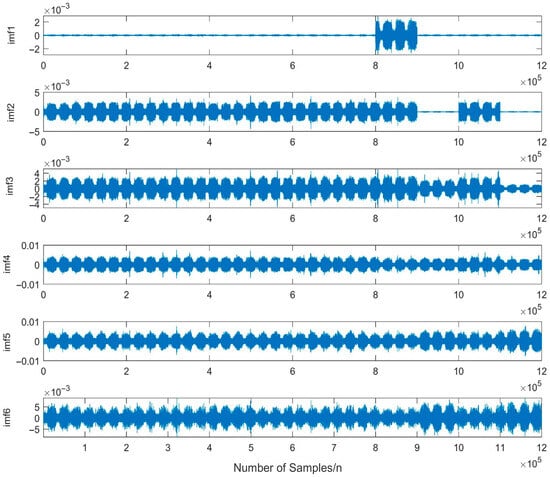

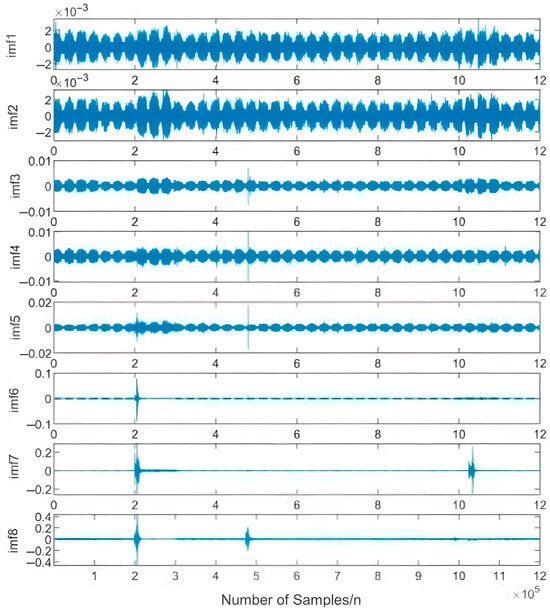

The obtained parameters k and α were subsequently incorporated into the VMD algorithm. The resulting decomposition waveforms of the acoustic emission signals from gears under both normal and wear fault conditions, processed using WOA-VMD, are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Decomposition waveform of gear under normal condition using WOA-VMD.

Figure 9.

Decomposition waveform under compound fault condition using WOA-VMD.

Secondly, to select effective IMF components containing fault-related information for signal reconstruction, correlation analysis was performed on the decomposed IMFs. The correlation coefficients of IMF components under both operational conditions are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficient for each IMF component in the two running states.

As evidenced by the data presented in Table 4, noise signals exhibit low correlation with the original signal, resulting in diminished correlation coefficients. Consequently, IMF4, IMF5, and IMF6 from the normal gear, along with IMF6, IMF7, and IMF8 from the faulted gear, were selected as effective fault signatures for reconstruction (Figure 8 and Figure 9), The reconstructed signals are shown in Figure 10a,b. The remaining components, identified as noise, were discarded to achieve denoising of the original acoustic emission signals.

Figure 10.

Results diagram of reconstruction in two running states. (a) Reconstructed time-domain waveform of IMF 4, 5, and 6 for the normal gear. (b) Reconstructed time-domain waveform of IMF6, 7, and 8 for the faulted gear.

4. Adaptive Selection of Gear Fault Characteristic Parameters

4.1. RFE-SVM

In gear fault diagnosis, determining appropriate feature parameters is a critical issue within the entire diagnostic system. If the selected feature parameters effectively represent samples of various fault types in a component and are well separated from each other, the accuracy of subsequent classifiers can be ensured. Conversely, if the chosen features fail to adequately distinguish between different fault patterns, even the most sophisticated classification methods will result in poor accuracy [25].

It is well known that even for the same equipment or component, under different operating conditions, the effectiveness of a feature in classifying different fault modes can vary significantly. If the selected features align well with the characteristics of the fault modes, the classification performance will be highly effective. On the other hand, if the feature selection is inappropriate and the features do not effectively represent the fault modes, the fault diagnosis is likely to fail. Therefore, to meet both requirements, it is often necessary to extract multiple types of features to form a high-dimensional feature vector for the equipment. While this provides a more comprehensive description of the fault modes, high-dimensional feature vectors can lead to inaccurate fault classification results and may sometimes even reduce classification accuracy [26]. Thus, it is essential to perform optimal selection from the initial feature set.

This paper focuses on the issue of feature selection and proposes the use of a recursive feature elimination approach. In other words, a new and rational feature space is constructed by selecting the most relevant original feature parameters and filtering out less significant ones.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a feature selection algorithm that operates by recursively removing the least important features. The process begins with the entire set of features, fits a specified model, ranks the features based on their importance, and discards the least significant ones. This procedure is repeated recursively on the pruned set until a predefined number of features remains.

In 2002, Guyon et al. introduced a backward recursive elimination feature selection algorithm for gene selection, which utilized the classification performance of Support Vector Machines (SVM) as the evaluation criterion. This method, termed SVM-RFE, operates by iteratively removing the features deemed least relevant to the classifier under a specific ranking criterion, continuing until only one feature remains. SVM-RFE is recognized for prioritizing an optimal subset of features during the ranking process. It is noteworthy that the top-ranked single feature does not necessarily guarantee the best identification performance for the classifier; instead, combining several good features often yields superior results.

As a supervised learning algorithm, the Support Vector Machine SVM demonstrates robust classification performance. Additionally, it is relatively insensitive to the dimensionality of the feature space, thus proving highly effective in managing high-dimensional problems. Consider a binary classification problem with a training set comprising “l” samples, each having “n “features. Here, the equation metaphorically signifies the two distinct classes. Let be the class label of a training sample . The SVM classification task is formulated as solving an optimization problem.

where:

controls the size of the classification margin;

are slack variables, permitting some training samples to violate the margin constraint;

is the penalty parameter, balancing margin maximization and classification error.

The class label of an unknown sample is predicted by the decision function , where is the feature weight vector.

If , the sample is predicted as class + 1; otherwise, it is predicted as class−1. This function directly outputs the class label for a given sample.

For a given feature “j”, let denote the value of the criterion after its removal. The magnitude of the corresponding weight is approximately equal to the variable of the optimization problem. The objective of the RFE-SVM algorithm is to find a feature subset that minimizes . Consequently, can be utilized as a criterion for evaluating feature importance.

The workflow of the RFE-SVM algorithm is as follows:

Input: Training set , is a sample in an n-dimensional space. The class label is denoted as .

Step 1: Initialize the feature ranking set Q as an empty set and set the current feature index sequence as k = [1, 2,…, n];

Step 2: Based on the current feature set, acquire new sample data and train a Support Vector Machine SVM with this new dataset;

Step 3: Features are sorted in descending order according to the magnitude of their corresponding weights . The feature with the lowest ranking is then placed into the feature ranking queue ;

Step 4: Eliminate the feature with the lowest ranking from the existing feature set.

Step 5: The algorithm then reverts to Step 1, and the iteration continues until the feature index sequence is empty.

Output: The feature ranking queue Q.

The absolute value (or its square ) of the weight vector component reflects the contribution of the k-th feature to the classification decision-a larger value indicates greater feature importance. RFE uses this criterion to iteratively remove the least important features.

4.2. Adaptive Ranking and Selection of Features Based on RFE-SVM

Based on the introduced feature parameters and to address the challenge of effectively extracting gear fault characteristics, a sliding window sampling method was employed to obtain 400 samples of acoustic emission signals from gears under normal conditions and with wear faults at 900 r/min. From these samples, seven time-domain parameters, four frequency-domain parameters, and four entropy-based feature parameters were extracted. The labels assigned to these three categories are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Feature index sequences.

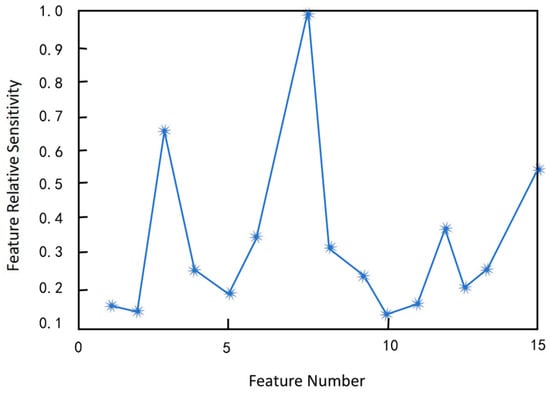

The training set was fed into the RFE-SVM for model training and automatic feature ranking. The optimal indicators from time-domain, frequency-domain, and entropy features were obtained, and the top three features from each domain were selected to form a hybrid feature set. The resulting feature ranking queue is shown in Figure 8.

As shown in Figure 11 below, the features on the vertical axis are ranked by sensitivity according to their squared weight w2, with those having smaller values being eliminated first. Therefore, for the acoustic emission signals of normal and worn gears in this experiment, the optimal indicators that best represent the gear condition are features No. 3, 7, and 15, namely root amplitude, kurtosis, and energy entropy. Accordingly, these three indicators are combined to form a high-dimensional feature vector set, which serves as the input to the support vector machine.

Figure 11.

Feature sorting queue graph.

5. Gear Fault Acoustic Emission Signal Recognition Based on PSO-SVM

Regarding the effectiveness of adaptive feature parameter extraction for gear fault characterization using acoustic emission signals, the Support Vector Machine SVM demonstrates strong generalization capability, maintaining high classification accuracy even in environments with sparse training samples [27]. Therefore, this chapter applies this method to classify feature vector set samples to validate the effectiveness of the RFE-SVM approach. Furthermore, to address the issue of parameter selection in the algorithm, an improvement using the Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm is proposed.

5.1. Support Vector Machine

The Support Vector Machine SVM is a binary classification model designed for small-sample learning. Its fundamental model is defined as a linear classifier that operates on the principle of maximizing the margin in the feature space, which ultimately translates into solving a convex quadratic programming problem. Whether in the sample space or feature space, SVM constructs an optimal hyperplane that maximizes the distance between samples of different classes, thereby maximizing generalization capability [28]. The final decision function of SVM is determined solely by a small number of support vectors. Its computational complexity depends on the number of support vectors rather than the dimensionality of the sample space, thus effectively mitigating issues caused by high-dimensional feature parameters.

5.2. Analysis of Gear Fault Diagnosis Results Based on RFE-SVM

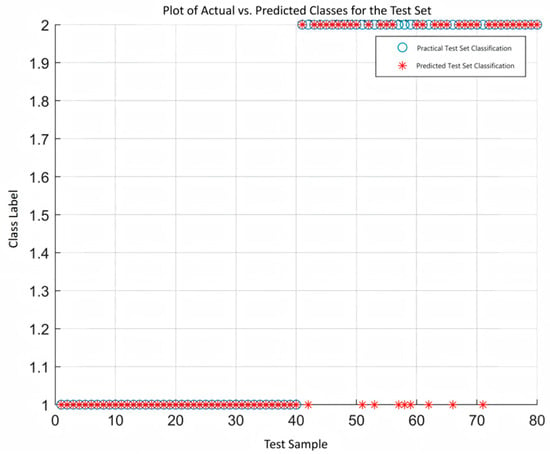

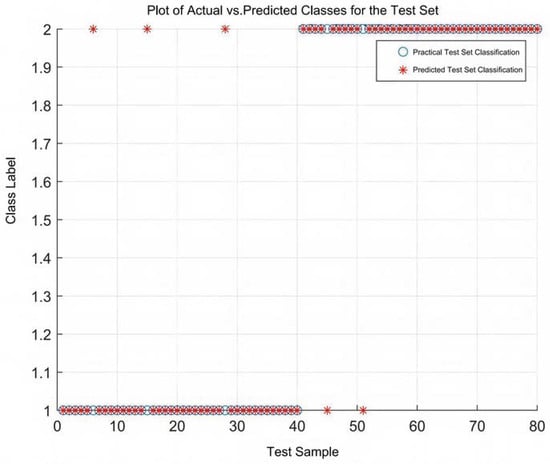

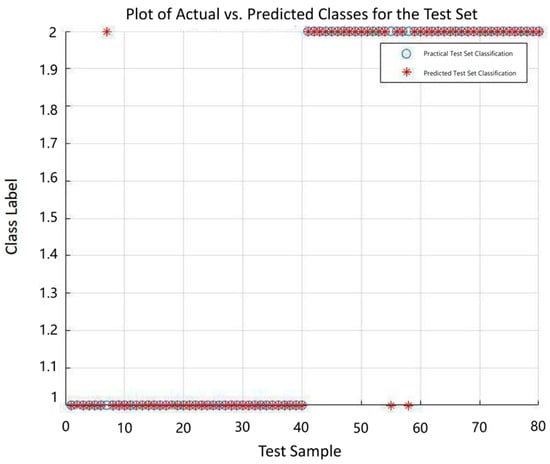

After adaptive feature parameter extraction via RFE-SVM, the root amplitude, kurtosis, and energy entropy were selected to form a hybrid feature vector set as input to the Support Vector Machine [29]. For comparison, two alternative feature sets were constructed: one with three randomly selected feature parameters and another containing all fifteen original feature parameters. The experimental results, as illustrated in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, demonstrate the following:

Figure 12.

The SVM classification results for the 3 feature parameters.

Figure 13.

The SVM classification results for the 15 feature parameters.

Figure 14.

REF-SVM selected the SVM classification results for 3 feature parameters.

A comparison between Figure 12 and Figure 14 reveals that the classification accuracy using three randomly selected feature parameters is relatively low at 88.75% (71/80), with 9 misclassified samples. When all 15 feature parameters are used as input, the classification accuracy increases to 93.75% (75/80), with only 5 misclassified samples, indicating an improvement over the random selection approach. In contrast, Figure 11 demonstrates that the three optimal feature parameters selected by RFE-SVM achieve an accuracy of 96.25% (77/80).

In summary, the use of randomly selected feature parameters tends to reduce SVM classification accuracy due to the inherent uncertainty in manual selection. While employing all 15 high-dimensional feature parameters does improve accuracy, it also increases computational burden and fails to address issues such as information redundancy and correlation among features. By prioritizing features based on their importance through RFE-SVM, the results show that not only is computational efficiency improved, but classification accuracy is also enhanced.

5.3. Particle Swarm Optimized Support Vector Machine

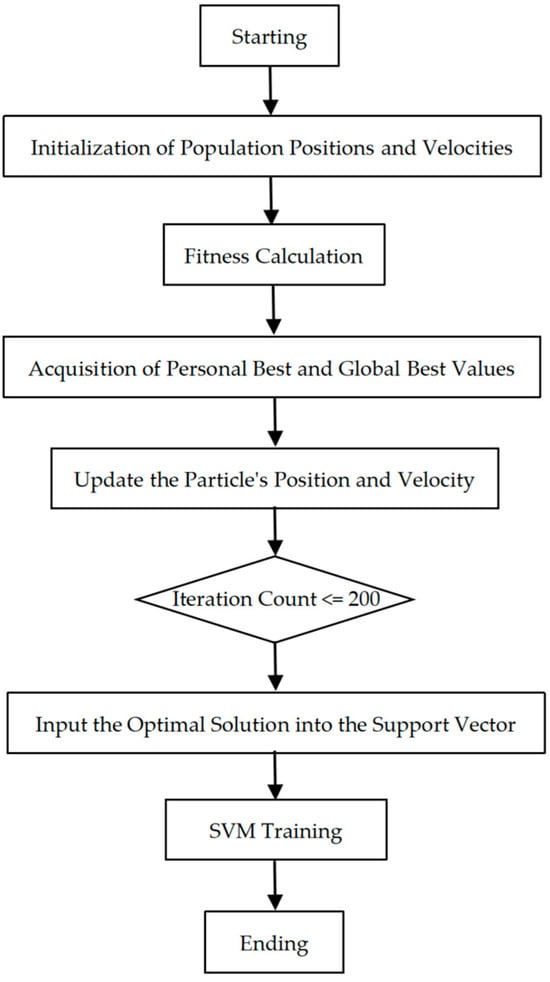

The detailed workflow of the PSO-SVM algorithm is illustrated in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Flow chart of PSO-SVM.

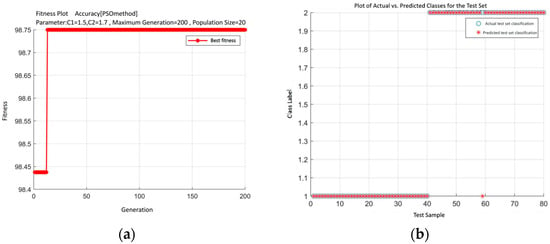

However, since the penalty factor C and kernel parameter g in the Support Vector Machine SVM can significantly affect the accuracy of the results, the Particle Swarm Optimization PSO algorithm is also introduced for parameter optimization. This study proposes a novel method for gear wear fault diagnosis that integrates GWO-VMD with PSO-SVM. The proposed method is validated and analyzed through experimental data, and the experimental results of PSO-SVM for fault diagnosis are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Results of PSO-SVM. (a) Fitness Curve. (b) PSO-SVM Classification Results.

From the fitness curve in Figure 16a and the classification results of the test set in Figure 16b, it can be observed that: in Figure 16a, the initial values of the kernel parameter *g* and penalty factor C are set to 1.5 and 1.7, respectively, with a population size of 20 and a maximum of 200 generations. Using the optimized parameter values as shown in Figure 16a, the experimental results based on PSO-SVM achieve an accuracy of 98.75% (79/80), with only one misclassified sample. This indicates that after the parameter optimization via the Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm, the classification accuracy of the SVM is significantly improved.

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion on the Content of This Study

This paper focuses on an adaptive feature extraction method for gear faults that integrates WOA-VMD and RFE-SVM. The VMD algorithm is applied to decompose simulated acoustic emission signals of gears, demonstrating superior decomposition performance by effectively addressing mode aliasing issues, enhancing decomposition completeness, and reducing reconstruction errors [30]. The WOA is employed to optimize the selection of the mode number *k* and penalty factor α in VMD, enabling effective decomposition of experimentally acquired gear acoustic emission signals while mitigating noise interference.

To validate the effectiveness of the RFE-SVM-based feature extraction method, SVM classification is performed using three randomly selected features, all 15 features, and the top three features identified by RFE-SVM. Comparative experimental results demonstrate that the three features selected by RFE-SVM achieve the highest classification accuracy. To address parameter selection in SVM, the PSO algorithm is introduced for optimization, with experimental results confirming its effectiveness.

As both VMD and PSO are intelligent optimization algorithms, their performance is influenced by parameter selection. Therefore, determining appropriate parameters for these optimization algorithms remains a topic for further investigation [31]. Although this study achieves diagnosis of gear wear faults based on acoustic emission signals, it does not precisely localize fault positions. Future work should focus on fault localization to enable early fault resolution, ensure safe and stable operation, and reduce economic losses and resource waste.

6.2. Future Research Directions

The influence of material types and their tribological properties on gear noise and signal characteristics has not yet been systematically investigated. Future research will focus on:

- (1)

- Comparing the acoustic emission response differences among various materials (e.g., cast iron, composites, surface-coated gears) under identical failure modes;

- (2)

- Analyzing the mechanisms through which material damping, hardness, and surface properties affect noise spectra and signal attenuation;

- (3)

- Establishing a coupled “material–lubrication–noise” relationship model by incorporating lubricant variables, with the aim of enhancing the diagnostic method’s applicability across diverse engineering scenarios.

Extent of Investigation into Material Tribological Properties. This study primarily focuses on fault-diagnosis methods based on AE signals. The examination of material tribological properties is mainly reflected in the following manner: AE signal characteristics—such as energy, counts, and frequency features—indirectly capture the stress-wave release behavior of near-surface material during wear-related damage processes on gear teeth. This behavior is inherently linked to tribological properties of the material, including hardness, toughness, and surface-treatment techniques. However, the present work does not systematically compare the AE responses of different materials (e.g., cast iron, composites, surface-coated gears) under identical operating conditions, nor does it establish a quantitative model relating material parameters to noise-emission characteristics. Consequently, the influence of material tribological properties on noise is addressed in an indirect and qualitative manner in this study.

The type of lubricant significantly influences gear noise generation, and existing research has elucidated its mechanisms from multiple perspectives including rheological properties, film formation mechanisms, and additive effects. Studies indicate that high-viscosity synthetic oils can effectively suppress mid-to-high-frequency meshing impact noise by enhancing elastohydrodynamic lubrication film thickness, while lubricants containing extreme-pressure additives reduce stick-slip vibrations at contact surfaces under boundary lubrication conditions through the formation of tribochemical reaction films.

Recent cutting-edge research has further focused on the active noise-control potential of smart lubricants (e.g., magnetorheological fluids, nano-modified lubricants), as well as the synergistic effects of lubricant-temperature-surface topography in multiphysics coupling models.

However, current research still faces challenges such as operational-condition adaptability contradictions (e.g., viscosity stability over wide temperature ranges), the matching specificity of lubricant–material pairs, and insufficient quantification of the impact of long-term aging on noise characteristics. In the field of fault diagnosis, lubricants not only act as a noise variable, but their rheological changes also modulate the baseline energy and spectral distribution of acoustic emission signals. Future work needs to establish decoupling models between lubrication states and fault signals to enhance diagnostic robustness.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Main Work of This Study

This paper systematically elucidates the causes and typical failure modes of gear faults, while providing a detailed introduction to AE signal processing techniques. Through the design of gear fault AE experiments, the application efficacy of AE technology in the field of gear fault diagnosis is thoroughly investigated.

For adaptive extraction of gear fault features, a hybrid method integrating WOA-VMD and RFE-SVM is proposed. This approach first employs the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) to optimize the parameters of VMD, enabling adaptive signal decomposition [32]. Subsequently, RFE-SVM is applied for optimal feature selection. Experimental results demonstrate that the feature parameters selected by RFE-SVM can more effectively characterize gear operating conditions, with classification accuracy significantly surpassing traditional feature selection methods.

Digital twin technology and gear fault identification based on SVM/machine learning are closely linked through a “virtual–physical fusion” mechanism. The digital twin constructs a high-fidelity dynamic model of the gear system, generating simulated data under multiple operating conditions and fault modes, which effectively alleviates the scarcity of real fault samples and provides SVM/machine learning models with abundant training data and feature-enhancement foundations.

Meanwhile, the twin model can inversely deduce the physical mechanisms of faults, thereby imparting interpretability to machine learning outcomes. Collaborative research directions include: twin-data-driven adaptive feature engineering, a virtual-physical closed-loop online incremental learning diagnostic framework, and an integrated fault-prognosis-lifetime-assessment model incorporating damage simulation. Future studies need to address challenges such as twin-model light-weighting, uncertainty quantification, and standardized integration, so as to advance gear fault diagnosis toward a real-time prediction and dynamically optimized intelligent maintenance paradigm [33].

7.2. Main Contributions of This Study

This research addresses challenges in gear fault diagnosis using acoustic emission signals, such as strong noise interference, reliance on manual feature extraction, and empirical dependency in classifier parameter tuning. A diagnostic framework based on adaptive signal decomposition and intelligent feature selection is proposed. The main contributions are as follows:

- 1.

- An adaptive denoising method based on GWO-VMD is proposed. This method overcomes the mode mixing issue of traditional EMD based approaches under strong noise conditions, improving the denoising completeness and reconstruction fidelity of gear wear fault signals.

- 2.

- A feature adaptive screening mechanism using SVM-RFE is introduced. It resolves the problems of dependence on expert experience and high computational redundancy in traditional feature selection methods, enabling automated importance ranking and dimensionality reduction in high-dimensional feature vectors.

- 3.

- A PSO-SVM classification model is developed. By adaptively optimizing the kernel parameters and penalty factors, this model enhances the accuracy and stability of fault classification while avoiding the inefficiency and tendency to fall into local optima associated with traditional grid search methods.

- 4.

- Furthermore, in contrast to deep learning methods such as long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, which are widely used for time-series classification, the proposed PSO-SVM model operates on carefully selected discriminative features rather than raw sequential data. This approach not only reduces computational complexity and training time but also provides clearer insight into which signal characteristics contribute to fault diagnosis-an aspect often lacking in end-to-end LSTM models.

- 5.

- The effectiveness of the proposed framework in gear wear fault diagnosis is experimentally validated. Compared with conventional methods, the framework demonstrates significant improvements in noise robustness, feature interpretability, and classification accuracy.

A comparative analysis between the proposed method and existing typical approaches is summarized below:

- 1.

- In terms of signal denoising: Compared to classical EMD and ensemble EMD (EEMD) methods, the VMD combined with GWO-based parameter selection adopted in this study better suppresses mode mixing under strong background noise and improves signal reconstruction quality.

- 2.

- In terms of feature extraction: Traditional methods often rely on statistical features or manual screening. This study introduces SVM-RFE to achieve adaptive feature ranking, which not only reduces dimensionality but also preserves discriminative information, outperforming conventional PCA or filter-based methods.

- 3.

- In terms of classification modeling: Compared to SVM with default parameters or grid-search tuning, the PSO-optimized SVM parameters used in this study significantly enhance training efficiency while maintaining classification accuracy and avoiding overfitting.

- 4.

- In terms of the overall diagnostic framework and methodological novelty: While many machine learning approaches, including deep learning models (e.g., CNNs, LSTMs) and ensemble methods (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost), have been applied to gear fault classification, most of them operate directly on raw or minimally preprocessed signals, which can be highly sensitive to noise and require large labeled datasets. In contrast, the proposed framework distinguishes itself through its integrated adaptive signal processing and intelligent feature selection pipeline.

Unlike end-to-end deep learning models that act as “black boxes,” our method enhances interpretability by extracting physically meaningful features through VMD and SVM-RFE.

Compared to conventional machine learning models that rely on fixed feature sets or manual engineering, our approach introduces adaptability in both signal denoising (via GWO-optimized VMD) and feature selection (via SVM-RFE), making it more robust in high-noise, limited-data scenarios.

While many existing methods focus solely on classification accuracy, our framework explicitly addresses the full pipeline from noise suppression to feature refinement, offering a more comprehensive and generalizable solution for industrial fault diagnosis under realistic conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, and writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, N.L.; supervision and resources, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Shenyang University of Technology, Shenyang, China, for their support throughout the research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lei, Y.; Jia, F.; Kong, D.; Lin, J. Opportunities and Challenges of Mechanical Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Under Big Data. J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 54, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.B.; He, Z.J.; Chen, X.F.; Lai, Y.N. Basic Research on Mechanical Fault Diagnosis: “Where to Go”. J. Mech. Eng. 2013, 49, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, O.D.; Rantatalo, M.; Aidanpaa, J.O. Dynamic modelling of a one-stage spur gear system and vibration-based tooth crack detection analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2015, 54, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Li, W.; Zhu, X. Practical Technology for Gear and Gearbox Fault Diagnosis; Mechanical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Kou, Y.; Tian, H. Current Status and Development of Fault Diagnosis Technology for Gearbox Systems. Mech. Eng. Autom. 2014, 29, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Research on Early Fault Signal Enhancement and Intelligent Diagnosis Methods for Gearboxes. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z. Research on the Vibration Problem of the Laying Head Gearbox in Xingtai Steel Wire Rod Plant; Beijing University of Technology: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vasić, M.P.; Stojanović, B.; Blagojević, M. Fault analysis of gearboxes in open pit mine. Adv. Eng. Lett. 2020, 5, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xiong, J.; Fu, Z. Fault Diagnosis Method for Low-Speed Heavy-Duty Gearboxes Based on AE Technology. Instrum. Detect. Technol. 2016, 35, 105–106. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Research on Gear Fault Diagnosis of Coal Mining Machinery. Energy Energy Conserv. 2019, 11, 29–30+35. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Han, Z.; Liu, Q. Research on Gear Tooth Surface Fault Simulation Method Based on Dynamics. Mod. Manuf. Eng. 2019, 5, 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, M.D.; Millan, D.Z. Chromatic monitoring of gear mechanical degradation based on acoustic emission. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 8707–8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, A.B.; Vicuña, C.M. New aspects concerning the generation of acoustic emissions in spur gears, the influence of operating conditions and gear defects in planetary gearboxes. Insight—Non-Destr. Test. Cond. Monit. 2016, 58, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, L.; Ralph, B.; Elisabeth, C. Comparative case studies on ring gear fault diagnosis of planetary gearboxes using vibrations and acoustic emissions. Forsch. Ingenieurwesen 2021, 85, 619–628. [Google Scholar]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F. Research on Friction Fault Diagnosis of Planetary Gearboxes Based on Acoustic Emission. Master’s Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, C.H. Operational Condition Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis of Wind Turbine Gearboxes. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B. Research on KECA in Fault Diagnosis of Planetary Gearboxes Using Acoustic Emission; Yanshan University: Qinhuangdao, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 22096; Condition Monitoring and Diagnostics of Machines—Acoustic Emission. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Han, J. Vibration Spectrum Mechanism Study of Gear Faults. J. Mech. Transm. 1997, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; He, D.; Van Hecke, B.; Nostrand, T.J.; Zhu, J.; Bechhoefer, E. Vibration-based wind turbine planetary gearbox fault diagnosis using spectral averaging. Wind. Energy 2016, 19, 1733–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.T. Acoustic Emission Testing Technology and Applications; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon, I.; Weston, J.; Barnhill, S.; Vapnik, V. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. Learn. 2002, 46, 389–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The Whale Optimization Algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Z.; Wen, H.J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W. Landslide susceptibility mapping using hybrid random forest with geo detector and RFE for factor optimization. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.Q.; Gao, L.Y.; Wu, C.R.; Wan, C. Informative Gene Selection Method Based on Symmetric Uncertainty and SVM Recursive Feature Elimination. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 2017, 30, 431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Y.J.; Sun, G.; Cai, Y.P. Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Variational Mode Decomposition Approximate Entropy and Support Vector Machine. Bearing 2016, 12, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.X.; Wu, T.J. Support Vector Machine Method in Pattern Recognition. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2003, 37, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.M.; Cui, X.; Zhou, B.; Peng, M. Short-term load forecasting based on particle swarm optimization-support vector machine. J. Wuhan. Univ. 2018, 51, 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Song, X.; Xue, D. A roller bearing fault diagnosis method based on hierarchical entropy and support vector machine with particle swarm optimization algorithm. Measurement 2014, 47, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Peng, Z.K.; Zhou, P. Review of signal decomposition and its application in mechanical fault diagnosis. J. Mech. Eng. 2020, 56, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. Research on Weak Fault Feature Extraction Method of Rolling Bearings Based on Signal Sparse Representation. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marinković, D.; Dezső, G.; Milojević, S. Application of Machine Learning During Maintenance and Exploitation of Electric Vehicles. Adv. Eng. Lett. 2024, 3, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.