Abstract

With the increasing scale and complexity of power systems, the Security and Stability Control System (SSCS) plays a vital role in ensuring the safe operation of the grid. However, existing SSCS implementations still face many limitations in cross-regional coordination, control precision, and risk prediction. Establishing the digital simulation model is an effective way to verify the control policy of SSCS. This paper proposes a neural heuristic task scheduling method based on deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to schedule the simulation tasks. It models the task dependencies of SSCS as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) and then dynamically optimizes task priorities and resource allocation through deep reinforcement learning. The method introduces multi-head attention and heterogeneous attention mechanisms to effectively capture complex dependencies among tasks, enabling efficient multi-core task scheduling. Simulation results show that the proposed algorithm significantly outperforms traditional scheduling methods in terms of makespan, load balancing, and resource utilization. It can also adapt to dynamic changes under different task scales and multi-core environments, demonstrating strong robustness and scalability.

1. Introduction

The Security and Stability Control System (SSCS) plays a critical defensive role in the power grid, with its primary goal being to respond to various disturbances and faults through precise computation and timely interventions [1,2]. It prevents the propagation of fault chains and ensures the stability of the power grid. However, currently SSCS face several limitations, including insufficient mechanisms of cross-regional coordination, low precision of control actions, and limited capabilities of risk prediction. In certain cases, these limitations could lead to unstable oscillations in power systems [3]. Typical events illustrating the severity of such failures include the “12·23” blackout in Ukraine (2015), the “9·28” blackout in Australia (2016), and the “3·21” blackout in Brazil (2018). We take the 2018 Brazilian incident as a concrete example: At 15:48 on 21 March, a 500 kV circuit breaker failed at the Xingu converter station, leading to voltage loss and disconnection of the Belo Monte hydropower transmission lines. This triggered a system collapse, resulting in a load loss of 18,000 MW across the national interconnected grid and the blocking of the ±800 kV Belo Monte-Rio de Janeiro UHVDC system, which alone caused a 4200 MW load loss in the southern region. Such large-scale blackouts cause severe economic losses and social impacts. Since destructive experiments on real-world power grids are infeasible, digital simulations have become effective measures to test control policy.

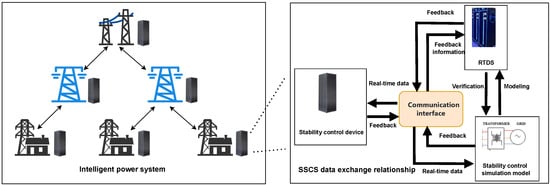

The control strategies of SSCS must be able to quickly adapt to real-time changes and make corresponding actions in the power grid, especially under various fault conditions. Since destructive experiments on real-world power grids are infeasible, digital simulations have become effective measures to test control policy. As illustrated in Figure 1, according to the inherent characteristics of tasks in SSCS, the control procedure of the stability control system can be modeled as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), which explicitly defines task dependencies.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the hybrid simulation of security and stability control system combining digital and physical entities.

As illustrated in Figure 1, according to the inherent characteristics of tasks in SSCS, the control procedure of the stability control system can be modeled as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), which explicitly defines task dependencies. It is important to distinguish between the physical communication topology shown in Figure 1 and the computational task graph. While physical information exchange may involve bidirectional feedback, the simulation process is decomposed into a sequence of dependent tasks, such as Fault Detection (), Stability Assessment (), and Remedial Action Execution (). This sequence forms a strict causal order () without cycles, thus forming the DAG for our scheduler. Different perspecific tasks and their target coresformance metrics significantly impact the outcome: optimizing the makespan ensures the system responds within the critical stability window, whereas poor load balancing might cause to wait for a congested core while others are idle, potentially leading to delayed actions and system collapse. The execution efficiency of the digital simulation model is important when generating the control policy.

The execution efficiency of the digital simulation model is important when generating the control policy. During the simulation, the model would be divided into several tasks. Task scheduling is a key issue in digital simulations of SSCS, as it assigns the specific cores for each task. In some cases, generating a feasible scheduling policy is sufficient. However, in most scenarios, it is necessary to produce a policy that achieves specific optimality. For example, to quickly recover system stability from a fault, SSCS must complete critical tasks in the shortest time by considering cross-regional coordination, task dependencies, and the competition for shared resources such as CPU and memory bandwidth. The goals are to minimize the overall execution time and optimize core utilization under various constraints.

Therefore, task scheduling of digital simulations faces numerous challenges. First, SSCS must make rapid decisions after a grid fault to maintain efficient operation under noisy input data and dynamically changing conditions. The execution order of tasks and resource allocation must be dynamically adjusted according to the real-time state of the grid to avoid task conflicts and resource waste [4]. Second, tasks within SSCS exhibit high inter-dependencies. The scheduler must optimize execution order to minimize delays while ensure that task dependencies are satisfied. Furthermore, the scheduler must simultaneously optimize multiple performance metrics, such as task makespan, resource utilization, and control precision [5].

To improve the scheduling effectiveness, we propose a DRL based dynamic multi-core task scheduling for real-time hybrid simulation model of SSCS in the power grid, denoted as SSCS-DRL. In recent years, the success of deep reinforcement learning in complex decision-making domains has provided new opportunities for optimizing task scheduling in SSCS. DRL learns directly from experience by interacting with the environment, making it suitable for handling complex task scheduling problems in SSCS [6]. In the scenario, DRL can dynamically adapt to real-time changes in the power grid and optimize control strategies through reward mechanisms. Considering the characteristics of SSCS, a DRL-based task scheduling method models the tasks within SSCS as a DAG to clarify the dependencies of the tasks. Then it trains a heuristic function through reinforcement learning to dynamically adjust task priorities. During the scheduling process, the SSCS-DRL algorithm continuously optimizes the heuristic function based on real-time data, thus improving scheduling efficiency and precision [7,8].

The proposed method can rapidly generate an efficient policy of task scheduling after grid faults and dynamically adapt to environmental changes. The algorithm demonstrates high robustness when facing small-scale disturbances, effectively avoiding system oscillations and instability. This method reduces the complexity of heuristic design and parameter tuning required by traditional scheduling methods, making it more efficient in the digital simulation of SSCS. The performance of the proposed method has been validated through extensive simulations. Experimental results show that, compared to traditional methods, the proposed deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-based task scheduling algorithm exhibits significant advantages in makespan and resource utilization. Moreover, the stability and robustness of the method in dynamic environments have also been verified.

To summarize, this paper has the following contributions:

- Task Modeling: We model the security and stability control system (SSCS) simulation tasks as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). This systematically characterizes the intrinsic dependency relationships between tasks, providing a solid model foundation for scheduling in complex concurrency scenarios.

- Algorithm Framework: We introduce a deep reinforcement learning (DRL) framework to achieve dynamic, adaptive adjustment of task priorities and resource allocation. By employing multi-head and heterogeneous attention mechanisms, the proposed method breaks through the rigid limitations of traditional rule-based scheduling.

- Performance Optimization: Extensive simulations validate that the proposed method significantly enhances scheduling efficiency, effectively shortening the total execution time (makespan) and improving resource utilization compared to traditional baselines.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on multi-core task scheduling. Section 3 formulates the CPU task scheduling problem as a mathematical model and details the proposed DRL-based method, including the Markov decision process modeling and the encoder-decoder neural network architecture. Experimental results and performance evaluations are presented in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future work.

2. Related Work

The multi-core scheduling problem is an NP-hard optimization [9]. To systematically address this challenge, existing research can be categorized into heuristic strategies, reinforcement learning frameworks, graph-based architectures, and specific power-system applications.

Traditional heuristic algorithms, such as List Scheduling and the Heterogeneous Earliest Finish Time (HEFT) algorithm, have been extensively studied on multi-core processors [10,11]. While strictly rule-based methods offer computational speed, meta-heuristic approaches like Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) have also been applied to search for better global solutions [12,13]. However, these algorithms generally rely on predefined rules or iterative searching, making them efficient only for specific scenarios. They are inflexible in adapting to dynamic changes in data characteristics and often result in local optima or excessive computation time. As modern systems like smart grids grow in complexity, manually maintaining these heuristic rules becomes increasingly impractical due to the high demand for domain expertise and limited scalability.

In the field of deep reinforcement learning (DRL), there is increasing attention due to its ability to learn adaptive strategies from dynamic environments [14]. Mao et al. [15] and Mangalampalli et al. [16] demonstrated that DRL-based schedulers outperform traditional heuristics in adaptability and resource utilization. To address the scalability issues in large-scale clusters, multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) techniques have been introduced to enable decentralized decision-making among processing cores [17]. Moreover, recent frameworks have further explored DRL for dynamic task scheduling in edge-cloud environments, not only to handle varying workloads and optimize latency [18] but also to balance energy consumption constraints in green computing scenarios [19].

Regarding advanced neural architectures, recent studies have integrated Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) into DRL to model complex task dependencies represented by Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) [20,21,22]. Recent surveys highlight the transformative impact of GNNs in solving complex job shop scheduling problems by modeling inter-task relations [20]. Additionally, considering the sequence-dependent nature of tasks, attention mechanisms and Transformer-based models have been leveraged to capture long-range dependencies and improve the policy’s expressiveness [23,24,25]. Hierarchical RL (HRL) has also been used to decompose complex tasks into manageable sub-goals [26]. Furthermore, advanced orchestrators now utilize preemptive strategies for multi-model inference on mobile edge GPUs, showcasing the versatility of modern RL-driven scheduling [27].

For applications in power systems and smart grids, DRL-based scheduling methods have shown great potential for real-time control and stability enhancement [28,29]. With the rise of digital twin technologies, high-fidelity real-time simulation has become a prerequisite for validating grid control strategies, imposing stricter deadlines on task execution [30]. Recent studies have conducted comprehensive analyses of load balancing specifically for mixed real-time tasks in multi-core environments [31]. Furthermore, DRL has been identified as a critical tool for navigating modern challenges in grid protection and automated control [2], as well as for managing computational resources in cyber-physical power systems (CPPS) under uncertainty [32,33].

Nevertheless, a critical research gap persists. Most general DRL-based scheduling methods do not fully account for the asymmetric dependencies and heterogeneous priority constraints inherent in Security and Stability Control System (SSCS) simulation tasks. Although Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can model general inter-task relations, they frequently neglect the rigid hierarchical significance of power system control actions. As summarized in Table 1, our proposed SSCS-DRL method addresses these limitations by introducing a heterogeneous attention mechanism within an encoder-decoder framework. Unlike traditional rule-based methods that depend on static attributes, our framework allows for dynamic priority adjustments tailored to the functional roles of tasks in the SSCS task graph. This specifically designed Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) approach achieves a superior balance between execution efficiency and system stability during complex grid simulations.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Scheduling Methods.

Overall, as illustrated in Table 1, deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has offered ideal solutions for addressing complex scheduling problems in multi-core systems. Despite these advancements, DRL-based scheduling methods continue to encounter significant challenges, including slow convergence rates and high computational complexity in high-dimensional state spaces. Existing research has predominantly concentrated on refining reward design, state representation, and exploration strategies to mitigate these issues [34].

However, research on DRL for SSCS task scheduling remains limited. To address this gap, our proposed method is specifically designed to generate efficient scheduling policies with rapid convergence.

3. Methodology

In this section, we formulate the CPU Task Assignment Problem (CTAP) as a mathematical model. CTAP aims to address the efficient and feasible assignment of a set of tasks to multi-core CPU. The goals are to minimize the overall execution time and optimize core utilization, subject to various constraints such as resource limits and task priorities. For clarity, the relevant symbols and notations are defined as follows.

3.1. Problem Formulation

To model the stability control procedure mathematically, the task structure is defined as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), denoted as . The node set V represents specific tasks (e.g., fault detection, stability assessment, remedial action execution), and the edge set E denotes logical dependencies (e.g., fault detection → stability assessment), ensuring a strict execution sequence without cyclic dependencies.

A typical instance of CTAP involves multiple cores and a set of N tasks to be scheduled. The task set can be divided into high-priority tasks and low-priority tasks, where the resource requirements of each task (such as CPU cycles, memory usage, etc.) are known in advance. In conventional setting, each core must complete all assigned high-priority tasks before executing any low-priority task. However, in this work, high-priority and low-priority tasks can be interleaved within the allocation sequence, provided that the total resource usage does not exceed the processor’s capacity.

The computing environment consists of K CPU cores. To align with the hierarchical architecture of power grid control systems, we categorize these cores into functional types (e.g., Master, Main, and Auxiliary). Each core maintains a normalized load value and operates at its full capacity when executing a task.

Formally, CTAP can be modeled as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) , where denotes the set of task nodes, including both high-priority and low-priority tasks. To facilitate the calculation of the makespan, is defined as an augmented set , where represents the initial idle state (virtual start node) of each core, and represents the virtual end node (referenced as the sink node in later sections). The edge set represents all possible transitions or scheduling orders between tasks. The scheduling sequence for each core corresponds to a path in this graph.

To formalize the model, we define the following decision variables and parameters: : A binary decision variable that equals 1 if task j is processed immediately after task i on core k, and 0 otherwise. : A continuous variable representing the completion time of task j.: The execution time required for task j.: The resource requirement (e.g., CPU, memory) for task j.: The cost incurred when task j is executed after task i on core k. With these variables defined, the optimization objective and constraints are formulated as follows:

The variables and parameters used in the above formulation are summarized as follows:

- : set of cores;

- : set of task nodes;

- : set of directed edges;

- : set of high-priority tasks;

- : set of low-priority tasks;

- : an indicator. It equals to 1 if core k schedules from task i to task j;otherwise, it equals 0; Specifically, the index 0 denotes a virtual start node, representing the initial idle state of a core, while the index denotes a virtual end node. Thus, = 1 indicates that task j is the first task scheduled on core k.

- : context-switching cost of core k when transitioning from task i to task j (excluding task execution costs). The resource requirement for executing task j itself is denoted by ;

- : scheduling cost of core k from i to j;

- : resource requirement of task j;

- D: resource capacity of a core.

This mathematical optimization model addresses a multi-core CPU task scheduling problem. In this model, task execution times and resource profiles are assumed to be deterministic, based on the Worst-Case Execution Time (WCET). This deterministic assumption is critical for ensuring the predictability and reliability required in Security and Stability Control Systems (SSCSs), which are designed to minimize total scheduling costs while adhering to multiple operational constraints. Equation (1) defines the objective function, minimizing the cumulative scheduling cost across all processing cores. The total scheduling cost primarily consists of makespan (overall completion time) and resource utilization components. Among these, minimizing makespan is the primary optimization goal, as it directly reflects the efficiency of task scheduling. Resource utilization is considered a secondary objective that supports overall system performance. It should be noted that while Equation (1) is formulated as the minimization of the cumulative scheduling cost, the individual costs are defined as a weighted composite of the incremental execution time and a resource efficiency penalty. This ensures that the objective effectively minimizes the overall makespan while simultaneously optimizing core utilization. In the multi-core context, this is achieved by modeling the DRL agent’s reward function to penalize the completion time of the last finished task (the virtual sink node ), which corresponds to the maximum path cost among all cores . Consequently, the “total cost” in this formulation serves as a mathematical proxy for the -oriented makespan objective, focusing on the critical path rather than a simple arithmetic summation of individual task durations.

Equation (2) guarantees unique assignment of each task to a single core with exactly one scheduling instance. Constraint (2) ensures each task has a unique predecessor within its assigned core.While this constraint alone does not explicitly forbid cycles, such cycles are rendered impossible by the combined effect of the DAG structure and the variable definition. Since the decision variable is defined exclusively for edges in the acyclic graph , no cyclic scheduling path can be represented in the solution space. Equation (3) preserves task flow continuity, ensuring uninterrupted execution sequences within each core.

The classical implementation enforces strict priority sequencing through complementary constraints: Equation (4) prohibits direct transitions from high-priority tasks to low-priority tasks, representing only the traditional baseline method. Meanwhile, Equation (5) prevents cores from initiating the execution of any low-priority task while high-priority tasks remain unprocessed. Notably, when only high-priority tasks exist (i.e., ), the inner summation defaults to 0 by mathematical convention for summation over an empty set. Consequently, the left-hand side of Equation (5) becomes , satisfying the constraint automatically. It is crucial to emphasize that these constraints define the traditional baseline model, which serves as a reference point for comparison. Collectively, these equations mandate sequential execution of priority tiers while remaining feasible across all task scenarios, including cases with only high-priority tasks.

Equation (6) ensures the precise fulfillment of task resource requirements by modeling the net resource flow at task node j to match its execution cost . Equation (7) then enforces per-core resource capacity limits to ensure that cumulative resource usage remains within the core’s physical boundaries. These equations collectively function as a “resource capacity governor” for each processing core. Specifically, Equation (6) tracks the cumulative resource consumption along the task execution sequence, ensuring that the resource state is monotonically updated as tasks progress. Equation (7) acts as a safety threshold, guaranteeing that at no point does the instantaneous resource demand exceed the capacity D. This modeling prevents resource over-subscription and ensures that heavy-load simulation tasks do not trigger core-level stalls or overflows.

Equation (8) formally defines the domain constraints for decision and resource variables. Let be a binary decision variable that equals 1 if task j is processed immediately after task i on core k, and 0 otherwise. It is crucial to note that this variable is only defined for the directed edges present in the task dependency graph. That is, can only be 1 if . This inherent restriction, dictated by the underlying DAG, is a fundamental property that prevents the formation of cyclic paths in any feasible solution.

This mathematical optimization model aims to minimize the total scheduling cost, which is defined as a weighted function of the overall execution time (makespan) and resource utilization components. Among these, minimizing the makespan is the primary optimization goal as it directly reflects scheduling efficiency, while resource utilization serves as a secondary objective to ensure balanced core performance, consistent with the goals described in Section 1.

In practice, the classical model typically enforces a strict priority constraint: each core must complete all assigned high-priority tasks before executing any low-priority task. This constraint ensures system responsiveness and the timely execution of critical tasks. In such a baseline system, a transition from a low-priority task to a high-priority task is strictly prohibited within the same execution sequence, as high-priority tasks must always take precedence. Our improved model relaxes this by allowing interleaved execution, provided resource constraints are met, thereby resolving the under-utilization issues inherent in the classical approach.

In our model, context-switching cost is defined as a time overhead parameter incurred when a core switches between tasks with different execution contexts. While the overhead per switch is constant, the total number of switches is governed by the binary variables . These costs are implicitly optimized within the objective function because they are integrated into the task completion times , thereby directly influencing the overall makespan. Consequently, minimizing the makespan drives the scheduler to prioritize sequences that minimize switching frequency.

While the strict priority-based scheduling in the baseline system ensures logical isolation between task tiers, it inherently limits resource throughput by preventing cores from executing available low-priority tasks during high-priority wait states. Our proposed model redefines this formulation by relaxing the sequence constraint to allow interleaved execution. This shift allows for higher core utilization and a shorter overall makespan, albeit at the cost of a more complex scheduling logic, representing a strategic trade-off between strict priority adherence and system-wide efficiency.

In the classical baseline, the strict priority constraint is mathematically defined to ensure that no low-priority task can start on any core until the entire set of high-priority tasks has been dispatched. This does not necessarily imply a global synchronization barrier after each individual task, but rather ensures the dominance of high-priority execution paths. As the reviewer correctly notes, a naive implementation might allow interleaving; however, our proposed relaxed model formally codifies this interleaved execution as a deliberate strategy to resolve core idleness, rather than an accidental byproduct of loose constraints.

To improve resource utilization and scheduling flexibility, this work introduces a relaxation of the task priority constraint. In the relaxed CTAP model, high-priority and low-priority tasks are allowed to be interleaved in the scheduling sequence, provided that the total resource consumption of each core does not exceed its capacity. This relaxation enables the system to achieve more efficient task allocation and core usage while still respecting resource constraints.

The fundamental distinction between the classical baseline and our proposed relaxed model lies in their approach to task prioritization. In the classical approach, the system strictly requires each core to complete all high-priority tasks sequentially before processing any low-priority tasks. This is enforced through two rigid mechanisms: (1) prohibiting any direct scheduling transitions from high-priority to low-priority tasks, and (2) ensuring cores never begin executing low-priority tasks when there are high-priority tasks. While this design guarantees the timely execution of critical tasks and strict logical isolation, it inherently limits scheduling flexibility and resource responsiveness.

The proposed relaxed model modifies these priority restrictions, retaining essential assignment rules and core capacity constraints. This enables the system to dynamically interleave execution of mixed-priority tasks according to real-time conditions, provided that total resource consumption per core remains within capacity limits. This strategy substantially enhances scheduling flexibility, allowing the system to better adapt to complex scenarios with dynamic task allocation while fully leveraging core capabilities.

By replacing static priority constraints with a dynamic scheduling policy, the scheduling mechanism improves overall efficiency and strengthens the responsiveness to dynamic workload under resource safety conditions. As demonstrated in the following section, this approach is particularly suitable for applications requiring balanced real-time performance and resource utilization.

3.2. DRL Problem Analysis

We provide a DRL-based multi-core task scheduling method for digital simulation of SSCS to solve the above formulated problem. We begin by modeling the process of the CPU scheduling as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). Subsequently, we propose an encoder-decoder-based neural network to parameterize the policy.

3.2.1. State Space

At each decision step t, the state of the system is denoted as , where represents the current assignment and execution status of all tasks (e.g., pending, running, completed), and denotes the available resources of each core at t. Specifically, can be represented as a vector indicating the status of each task node in , while is a vector of the remaining resources for all processors in . In the initial step (), indicates that all tasks are not assigned, and corresponds to the full resource capacities of all cores. It is essential to clarify the distinction between static task categories and the dynamic priorities learned by the SSCS-DRL model. While tasks are initially categorized into high or low priority tiers based on their functional roles in the SSCS, these labels serve only as baseline attributes. The actual execution order is not a simple fixed sequence; instead, the SSCS-DRL model learns a heuristic policy that dynamically adjusts the scheduling priority of each task based on the real-time state of the DAG and core resources. By processing task embeddings through the heterogeneous attention mechanism, the agent assigns an urgency weight to each pending task, effectively determining its position in the queue to minimize overall makespan while satisfying resource constraints.

3.2.2. Action Space

The action is a vector that includes the selection of a ready task and its assigned core , that is, . Only feasible assignments that satisfy both resource and dependency constraints are allowed. It illustrates the allocation relationship between cores and tasks. The scheduling agent generates specific scheduling actions based on the current state and optimization objectives.

3.2.3. Transition Dynamics

The state transition of the environment is co-driven by action execution and the mathematical model constraints. Upon triggering a scheduling action (assigning task i to core k), the system updates the task status to reflect that task i is occupied. Crucially, the core resource status is updated to mirror the resource flow variable defined in Equation (6). The specific update rule for the remaining resource capacity of core k is given by the expression:

where represents the resource requirement of task i. This explicit update ensures that the dynamic state transition strictly adheres to the resource conservation principles and capacity constraints (Equation (7)) of the underlying optimization model. Finally, the eligibility of queued tasks is updated according to the DAG dependencies.

3.2.4. Reward Function

The reward function designed in this paper aims to minimize the makespan and aligns with the optimization objective in Equation (1). At each step t, the agent receives a reward formulated as:

where is the incremental makespan, is the resource utilization, and is an indicator function representing a penalty for constraint violations. The coefficients are positive weighting factors that balance these objectives. This design directly translates the high-level optimization objective into a learnable signal for the DRL agent. Specifically, the reward function incentivizes the minimization of the overall makespan by encouraging tasks to be completed at the earliest possible time instances, and promotes efficient resource utilization through positive rewards while imposing penalties for resource wastage and core idleness. The cumulative reward is calculated using a discount factor , holistically considering both immediate and long-term scheduling performance. This design effectively guides the agent to learn efficient and robust scheduling policies that adapt to varying task scales and system states.

Moreover, the Markov Decision Process (MDP) framework provides a robust foundation for adapting to the inherent uncertainties of power grid environments, such as sudden faults, fluctuating workloads, and noisy input data. By designing the reward function to explicitly prioritize high-criticality tasks, the agent learns to assign higher rewards for the completion of these tasks at the earliest possible time instances. This mechanism effectively minimizes the queuing latency for time-sensitive operations (e.g., fault detection), thereby directly enhancing the system’s responsiveness to grid disturbances. This dynamic adjustment capability enables the scheduling policy to adapt to volatile conditions, aiming to improve overall system stability without requiring manual reconfiguration. Formally, the reward function is defined as a weighted composite objective: its primary component minimizes the incremental makespan () to ensure rapid response, while the secondary component optimizes resource utilization (). By penalizing resource idleness via the term, the function implicitly promotes load balancing, as balanced cores prevent bottlenecks that would otherwise degrade the primary makespan objective.

The objective is to learn a scheduling policy that maximizes cumulative reward. By interacting with the environment, the agent gradually discovers policies for reduced makespan, and optimized resource usage.

3.3. A DRL Solution for Multi-Core Task Scheduling

The proposed method is grounded in the theoretical framework of graph neural networks (GNNs), which have demonstrated remarkable success in modeling relational structures. While traditional GNNs excel at handling homogeneous graph data, our approach extends this paradigm through a novel heterogeneous attention mechanism that effectively captures the asymmetric relationships between different priority-level tasks in DAG-structured scheduling problems. This mechanism can be viewed as a GNN variant specifically designed for directed acyclic graphs with heterogeneous node types, where message passing follows the topological ordering while maintaining distinct processing pathways for high-priority and low-priority tasks. Unlike conventional GNNs that apply uniform aggregation across neighbor nodes, our method implements priority-aware information propagation through dedicated attention heads for different node types, enabling more nuanced modeling of the complex dependencies inherent in power system stability control tasks.

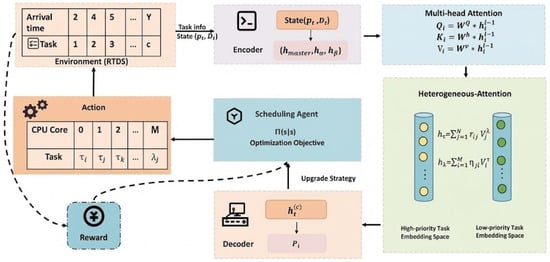

The proposed SSCS-DRL algorithm leverages the DAG framework defined in Section 3.1 to orchestrate the scheduling process. As detailed in the system overview in Figure 2, the architecture is visually organized to reflect the data flow from simulation to execution. The RTDS module (depicted as the input source) supplies real-time grid data to the central DRL agent. Crucially, the diagram illustrates the differentiated task routing mechanism: high-priority tasks (e.g., fault detection) are explicitly directed to the high-performance Master/Main Core clusters, while low-priority tasks are allocated to the Auxiliary Core pool, visually separating critical and non-critical execution pathways.

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of DRL-based multi-core task scheduling for digital simulation of SSCS. The RTDS serves as the simulation environment (depicted as the data source on the left), supplying real-time power grid states to drive the scheduling process.

In the multi-core scheduling, we have CPU cores . Each core has a normalized load value , where . When a task starts from a core, that core is running at its full capacity D.

To align with the hierarchical architecture of power grid control systems, we categorize the CPU cores into three functional types, as detailed below.

3.3.1. Master Core

As the central scheduler, responsible for system-level coordination, dependency resolution, and distributing scheduling decisions to other cores. It corresponds to the central controller in physical security and stability control systems. This mirrors the central control layer in power grid hierarchical architecture (e.g., regional dispatch centers), ensuring global decision-making alignment.

3.3.2. Main Cores

Execute high-priority simulation tasks critical for real-time grid stability (e.g., fault detection and stability algorithm calculations). These cores mirror primary control devices in the field. This aligns with the regional control layer (e.g., substation controllers), where critical tasks are handled for local stability.

3.3.3. Auxiliary Cores

Handle low-priority simulations and low-priority tasks, providing scalable computational resources to assist main cores during peak loads and improve overall system throughput. This maps to the field device layer in the hierarchy, supporting auxiliary functions like data logging and non-critical simulations.

In the encoder design, we first extract the initial embeddings for the master core, main cores, and auxiliary cores:

where represents the embedding of the master core, represents the embedding of the main cores, and represents the embedding of the auxiliary cores. The purpose of the embedding is to model the hierarchical coordination and functional dependencies between the master and auxiliary cores, providing more valuable representations for subsequent task scheduling.

Next, we design a two-stage multi-head attention mechanism to better capture these complex relationships.

In the initial stage, any two tasks within the scheduling system—whether they are assigned to different cores, the same core, or represent interactions between cores and tasks—may exhibit dependencies or resource contention. This indicates that potential correlations exist between any pair of tasks. Therefore, the multi-core scheduling on the tasks is represented as a graph, where a multi-head self-attention mechanism is utilized to capture the relationships among all tasks.

Specifically, the query, key, and value vectors are computed as follows:

denotes the embedding of the i-th task at the -th layer. and are learnable weight matrices.

To measure the correlation between tasks i and j, the self-attention mechanism first computes the dot product between the query and key vectors. Then it applies a scaling and softmax operation. It finally aggregates the result with the value vectors. Each attention head performs these operations in parallel. The resulting attention scores are computed as:

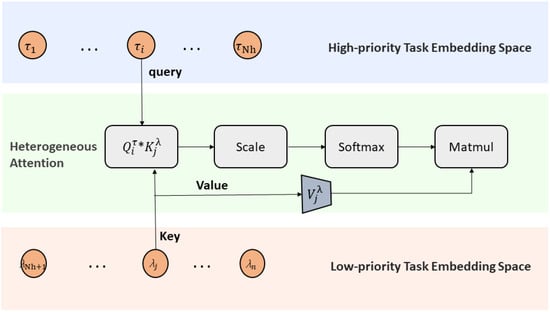

In the next stage, we utilize a heterogeneous attention approach to model the interactions between high-priority and low-priority tasks, as shown in Figure 3. This mechanism is based on cross-type aggregation. The computation for each task is as follows.

Figure 3.

The heterogeneous attention for tasks with different priorities, where and represent two different types of nodes.

For high-priority task , the updated representation at layer l is:

where the attention weight is computed as:

can be any learnable similarity function, such as a scaled dot product:

Similarly, for low-priority task , the update is:

where

The projections are given by:

After the attention operation, each embedding is processed by a feed-forward network:

Residual connections and instance normalization are also applied:

Both the final task embeddings and the graph embedding are used as inputs to the decoder for further scheduling. The final embedding for each task is the output of the last layer. The overall graph embedding is computed as:

In the decoder stage, the model takes the graph embedding from the encoder, the embedding of the node visited in the previous step , and the current Core load as input. These elements are concatenated to form the context vector at each decoding step.

This context vector is subsequently processed through a series of attention mechanisms to determine the selection probabilities for the next node. The process begins with a multi-head attention operation, where is treated as the query, and the embeddings of all candidate nodes serve as keys and values. Different linear transformations are applied in each attention head, allowing the model to aggregate information from various representation subspaces. The outputs of these heads are concatenated and passed through a final linear projection, producing a comprehensive context representation that enhances the decoder’s ability to capture intricate relationships among nodes.

A single-head attention mechanism is utilized to compute a compatibility score for each candidate node. Both the context vector and the node embeddings undergo linear mappings to generate their respective query and key vectors, denoted as and . The similarity between these vectors, typically measured by a dot product or another correlation function, derives a raw score for each node. To encourage exploration and control the score range, these values are usually scaled and passed through a non-linear activation, such as tanh.

To ensure feasibility, a masking procedure is applied to filter out nodes that violate constraints, such as those already visited, those exceeding resource limits, or those conflicting with priority rules. The scores of these infeasible nodes are set to a large negative value, effectively preventing their selection.

Finally, the scores for all candidate nodes are normalized using the softmax function, resulting in a probability distribution over the nodes for the current step. The decoder then selects or samples the next node according to this distribution, progressively searching a complete and feasible solution.

4. Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Settings

To validate the performance of our proposed algorithm, we design a set of tasks based on a hybrid simulation model of SSCS in power grids. We simulate the security and stability control system within a region and the information exchange between various stations by employing a randomly generated undirected graph with edge weights, where each node represents a stability control device.

We evaluated the performance by comparing four scheduling algorithms: Random Allocation (RA), First-Fit (FF), traditional Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), and the proposed SSCS-DRL method. The selection of these baselines ensures a comprehensive comparison: RA serves as a lower-bound performance metric; FF represents the widely-used industrial heuristic for real-time systems; and traditional DRL is included to isolate and validate the performance gains from our proposed heterogeneous attention mechanism and CTAP model. Note that both RA and FF are implemented under the strict priority constraints, where as the proposed SSCS-DRL operates under the relaxed priority constraints. The number of tasks and the total number of allocated cores in each scenario are presented in Table 2. To evaluate the robustness of the algorithms under resource-constrained conditions, we also introduce CPU frequency as a scaling factor for the core’s computing capacity. In our experiments, variations in frequency are applied to simulate different levels of computational resource availability. These experiments comprehensively demonstrate the efficiency of the scheduling algorithms in managing simulation tasks within the SSCS simulation model, focusing on minimizing the makespan to enhance overall system performance.

Table 2.

Experimental Parameters.

We evaluated the performance by comparing four scheduling algorithms: Random Allocation (RA), First-Fit (FF), traditional Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), and the proposed SSCS-DRL method. The selection of these baselines ensures a comprehensive comparison: RA serves as a lower-bound performance metric; FF represents the widely-used industrial heuristic for real-time systems; and traditional DRL is included to isolate and validate the performance gains from our proposed heterogeneous attention mechanism and CTAP model. The number of tasks and the total number of allocated cores in each scenario are presented in Table 2.

4.2. Experimental Results

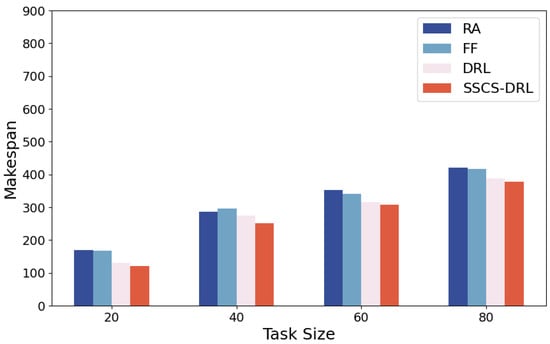

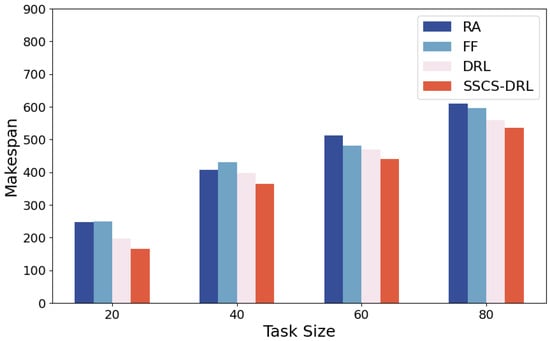

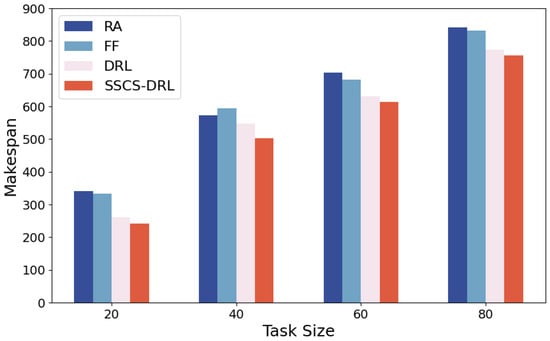

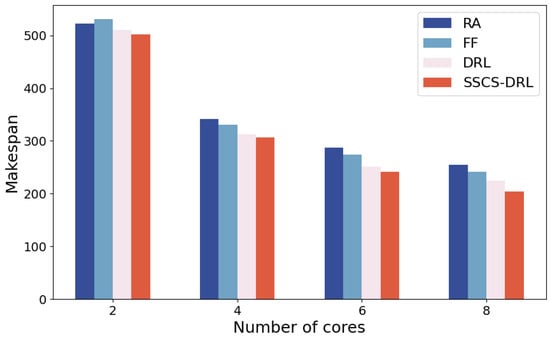

To comprehensively evaluate the impact of different task numbers and CPU frequencies on the performance of scheduling algorithms, experiments are conducted under scenarios where the number of tasks was set to 20, 40, 60, and 80. CPU frequency is set to 100%, 70%, and 50% of its full capacity. The Makespan performance of RA, FF, DRL, and SSCS-DRL algorithms are compared, as shown in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. Through comparative analysis, the performance differences of various algorithms under varying task loads and CPU frequencies, as well as their potential application scenarios, can be more clearly revealed.

Figure 4.

CPU frequency 3.2 GHz.

Figure 5.

CPU frequency 2.2 GHz.

Figure 6.

CPU frequency 1.6 GHz.

As shown in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, Experimental results indicate that while the makespan of all algorithms increases as task volume grows or CPU frequency drops, SSCS-DRL consistently maintains a significant lead. A key insight is that the performance gap between SSCS-DRL and baselines widens as system constraints tighten. For instance, in low-pressure scenarios (20 tasks, 100% frequency), SSCS-DRL outperforms RA, FF, and traditional DRL by 22.2%, 18.0%, and 15.0%, respectively. As the frequency reduces to 50%, the widening margin demonstrates the model’s superior adaptability and its ability to effectively mitigate resource contention in high-load power grid simulations.

Figure 7.

Comparison of makespan for various scheduling algorithms under varying numbers of CPU cores.

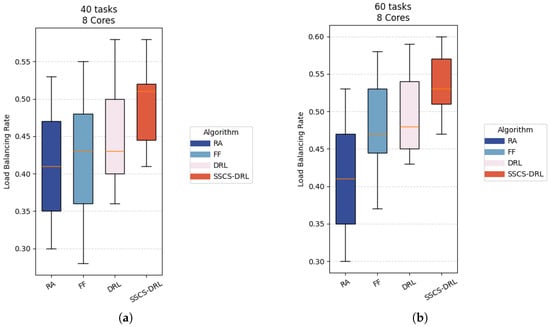

Although the primary optimization objective of this mathematical model is to minimize the completion time, the load balancing performance during task scheduling can also indirectly reflect the overall efficiency of the system. Therefore, as shown in Figure 8, we conducted comparative experiments in various scenarios to comprehensively evaluate the overall performance of the algorithm.

Figure 8.

Different tasks with 8 Cores cases Load rate box diagram. (a) Task Scheduling Load Balancing Rate (Case A); (b) Task Scheduling Load Balancing Rate (Case B).

The boxplot analysis in Figure 8 reveals two key advantages of the proposed algorithm: first, it achieves minimized load variance among cores; second, it attains the highest average load rate across all cores in the system. These results demonstrate a dual optimization: SSCS-DRL not only significantly reduces load variation between cores, but also achieves well-balanced load distribution.

Based on the above experimental results, it can be concluded that SSCS-DRL algorithm demonstrates outstanding performance under different task numbers and core configurations, particularly in reducing makespan and improving schedulability. This indicates that SSCS-DRL algorithm effectively addresses the task scheduling challenges in multi-core systems. Its performance significantly outperform existing algorithms such as RA, FF, and DRL, especially when handling complex simulation tasks in safety-critical and stability control systems. In summary, the superior performance of SSCS-DRL algorithm in both low and high-load conditions demonstrates its potential for practical applications where efficient task allocation and resource management are required. These experimental findings provide valuable insights for the design of task scheduling algorithms in the simulation of safety-critical and stability control systems.

5. Conclusions

This paper makes distinct contributions to addressing the practical limitations of digital simulation for security and stability control systems, with its achievement lying in the proposal of a task scheduling method based on DRL. Its primary theoretical contributions include modeling simulation tasks as a DAG to explicitly and systematically characterize the intrinsic dependency relationships between tasks and introducing the DRL framework into the scheduling decision-making process to realize dynamic, adaptive adjustment of task priorities and resource allocation strategies. Experimental results validate the method’s superior performance: compared with conventional scheduling approaches, it not only significantly enhances overall scheduling efficiency but also exhibits outstanding optimization effects in shortening task makespan and improving resource utilization. In terms of engineering application, while this method provides a solid technical foundation for the efficient management of modern power grids, several practical challenges for real-world deployment must be acknowledged. Specifically, the computational overhead of GNN-based inference needs to be further minimized to strictly adhere to ultra-low latency real-time constraints. Furthermore, transitioning from a deterministic model to one that accounts for stochastic execution jitters in hardware remains a critical direction for future improvement. Ultimately, these findings provide valuable insights for designing more robust and adaptive task scheduling algorithms in safety-critical simulation environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H. and Z.W.; methodology, D.H. and Z.W.; formal analysis, L.Z.; resources, Q.L.; writing, D.H. and Z.W.; funding acquisition, J.X. and B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was Funded by Science and Technology Project of SGCC Headquarters Management “Digital physical hybrid simulation verification technology and system development for complex security and stability control systems (5100-202340417A-3-2-ZN)”.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.Requests to access the datasets should be directed to 1607519221@mail.nwpu.edu.cn.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Lu Zhang was employed by Electric Power Research Institute, Xinjiang Electric Power Co. Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chamana, M.; Bhatta, R.; Schmitt, K.; Shrestha, R.; Bayne, S. An Integrated Testbed for Power System Cyber-Physical Operations Training. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, S.; Bogarra, S.; Nunes, M.; Gomez, X. Smart Grid Protection, Automation and Control: Challenges and Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, L.L. Power System Stability and Control; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsekas, D. Dynamic Programming and Optimal Control: Volume I; Athena Scientific: Belmont, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Long, X. Improved decomposition-based global EDF scheduling of DAGs. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2018, 27, 1850101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.; Schrittwieser, J.; Simonyan, K.; Antonoglou, I.; Huang, A.; Guez, A.; Hubert, T.; Baker, L.; Lai, M.; Bolton, A.; et al. Mastering the game of go without human knowledge. Nature 2017, 550, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Zhai, Z. A dynamic task scheduling algorithm for airborne device clouds. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 2024, 9922714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.I.; Burns, A. A survey of hard real-time scheduling for multiprocessor systems. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2011, 43, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajcar, M. Genetic list scheduling algorithm for scheduling and allocation on a loosely coupled heterogeneous multiprocessor system. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 21–25 June 1999; pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Topcuoglu, H.; Hariri, S.; Wu, M.Y. Performance-effective and low-complexity task scheduling for heterogeneous computing. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2002, 13, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, F.; Dobre, C.; Cristea, V. Genetic algorithm for DAG scheduling in grid environments. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 5th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 27–29 August 2009; pp. 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, C.T.; Liao, C.J. A particle swarm optimization algorithm for hybrid flow-shop scheduling with multiprocessor tasks. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 4655–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanetti, A.; Halgamuge, S.; Buyya, R. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework for Renewable Energy-Aware Workflow Scheduling on Distributed Cloud Data Centers. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2024, 35, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Menache, I.; Kandula, S. Resource management with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks, Atlanta, GA, USA, 9–10 November 2016; pp. 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mangalampalli, S.; Karri, G.R.; Kumar, M.; Khalaf, O.I.; Romero, C.A.T.; Sahib, G.A. DRLBTSA: Deep reinforcement learning based task-scheduling algorithm in cloud computing. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 8359–8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manduva, V.C. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Efficient Task Scheduling in Edge-Cloud Systems. Int. J. Mod. Comput. 2022, 5, 108–129. [Google Scholar]

- Supreethi, K.P.; Jayasingh, B.B. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Task Scheduling in Edge-Cloud Environments. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. Syst. 2024, 15, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Z.; Wei, J.; Ji, Z. Energy-aware task scheduling optimization with deep reinforcement learning for large-scale heterogeneous systems. CCF Trans. High Perform. Comput. 2021, 3, 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, I.G.; Zhou, J.; Reijnen, R.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; Bukhsh, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Nuijten, W. Graph neural networks for job shop scheduling problems: A survey. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 176, 106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Cao, Z. Flexible job-shop scheduling via graph neural network and deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 1600–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, L.; Gao, Z.; Luo, M.; Hosseinalipour, S.; Dai, H. GA-DRL: Graph neural network-augmented deep reinforcement learning for DAG task scheduling over dynamic vehicular clouds. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 4226–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisotto, E.; Song, F.; Rae, J.; Pascanu, R.; Gulcehre, C.; Jayakumar, S.; Jaderberg, M.; Kaufman, R.L.; Clark, A.; Noury, S.; et al. Stabilizing transformers for reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; Volume 119, pp. 7487–7498. [Google Scholar]

- Nachum, O.; Gu, S.; Lee, H.; Levine, S. Data-efficient hierarchical reinforcement learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.08296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, W.; Van Hoof, H.; Welling, M. Attention, learn to solve routing problems! arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.08475. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Q.; Li, J. Meta-hierarchical reinforcement learning (MHRL)-based dynamic resource allocation for dynamic vehicular networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 3495–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Z. Pantheon: Preemptible multi-dnn inference on mobile edge gpus. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications and Services, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 June 2024; pp. 465–478. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Han, X.; Deng, C. Review on the research and practice of deep learning and reinforcement learning in smart grids. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 4, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavic, M.; Fonteneau, R.; Ernst, D. Reinforcement learning for electric power system decision and control: Past considerations and perspectives. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 6918–6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V.; Patil, M.B.; Chandorkar, M.C. Real time simulation of power electronic systems on multi-core processors. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Power Electronics and Drive Systems (PEDS), Taipei, Taiwan, 2–5 November 2009; pp. 1524–1529. [Google Scholar]

- Jadon, S.; Kannan, P.K.; Kalaria, U.; Varsha, K.; Gupta, K.; Honnavalli, P.B. A comprehensive study of load balancing approaches in real-time multi-core systems for mixed real-time tasks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 53373–53395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, K.; Qiu, M.; Zhao, H.; Sun, X. Resource management in sustainable cyber-physical systems using heterogeneous cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2017, 3, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Naili, M. Deep reinforcement learning for penetration testing of cyber-physical attacks in the smart grid. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, A.Y.; Harada, D.; Russell, S. Policy invariance under reward transformations: Theory and application to reward shaping. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Bled, Slovenia, 27–30 June 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.